Abstract

Ectodomain cleavage of cell-surface proteins by A disintegrin and metalloproteinases (ADAMs) is highly regulated, and its dysregulation has been linked to many diseases. ADAM10 and ADAM17 cleave most disease-relevant substrates. Broad-spectrum metalloprotease inhibitors have failed clinically, and targeting the cleavage of a specific substrate has remained impossible. It is therefore necessary to identify signaling intermediates that determine substrate specificity of cleavage. We show here that phorbol ester or angiotensin II-induced proteolytic release of EGF family members may not require a significant increase in ADAM17 protease activity. Rather, inducers activate a signaling pathway using PKC-α and the PKC-regulated protein phosphatase 1 inhibitor 14D that is required for ADAM17 cleavage of TGF-α, heparin-binding EGF, and amphiregulin. A second pathway involving PKC-δ is required for neuregulin (NRG) cleavage, and, indeed, PKC-δ phosphorylation of serine 286 in the NRG cytosolic domain is essential for induced NRG cleavage. Thus, signaling-mediated substrate selection is clearly distinct from regulation of enzyme activity, an important mechanism that offers itself for application in disease.

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor, transactivation

The ectodomains of many cell surface proteins are shed from the surface (i.e., “ectodomain shedding”) by metalloproteases. Ectodomain shedding generates many diverse bioactive cytokines and growth factors, and governs important cellular processes in the developing and adult organism, including the control of growth, adhesion, and motility of cells (reviewed in refs. 1–3). EGF receptor activation generates signals for cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, or survival. The 12 EGF family members are synthesized as cell surface transmembrane precursors. The active growth factors are released by A disintegrin and metalloproteinases (ADAMs) and activate specific heterodimeric EGF receptors on the cell surface connected to diverse intracellular signaling pathways (4, 5). Increased shedding of EGF ligands has been linked to different clinical pathologic processes (6–10); hence, therapeutic control of ligand release would be beneficial. Of the 12 functional ADAMs encoded in the human genome (3) only two—ADAM10 and ADAM17—handle most of the numerous ADAM substrates, in particular, the EGF ligands. However, broad-spectrum metalloprotease inhibitors tested for clinical use have failed as a result of indiscriminate blockade of substrate cleavage, leading to clinical side effects (11). Even recently developed selective ADAM inhibitors still affect the cleavage of many substrates (12). Modulation of the release of specific ADAM substrates has been impossible to date because it is unknown how cleavage specificity is regulated on the molecular level. It is therefore necessary to identify key signals that determine substrate specificity of cleavage.

Ectodomain cleavage is made specific by a number of intracellular signals; e.g., by calcium influx, by activation of G protein-coupled receptors, and the release of diacylglycerol (reviewed in refs. 3, 13). Several distinct mechanisms that modulate cleavage on the level of ADAM17 have been described, including regulation of ADAM17 expression, maturation, trafficking to the cell surface (reviewed in ref. 13), and posttranslational modifications on the ADAM17 ectodomain (14, 15) or its C terminus (16, 17). However, modulation of activity of the relatively few available ADAMs does not suffice to explain substrate-specific regulation of cleavage (18, 19), and none of the referenced studies has addressed how specificity of cleavage is achieved. Transgenic overexpression of ADAM17 in mice does not lead to overactivity of ADAM17 or increased ADAM17 substrate release, emphasizing the importance of posttranslational control of cleavage (20). Most reports on induced shedding (reviewed in refs. 5, 21) have only used monitoring of substrate cleavage as a surrogate measure of protease activity. However, only few studies unequivocally document induced changes of protease activity, and those were small. A tight-binding ADAM17 inhibitor interacts with the catalytic site of ADAM17 only after 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA; i.e., phorbol ester) stimulation (12), suggesting regulation of the catalytic site. Another convincing example of regulated enzyme activity has been based on observed effects of oxidation on several putative disulphide bonds in the ADAM17 ectodomain that result in a structural change. This involves the interaction with an extracellular redox regulator, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI). PDI down-regulation enhanced TPA-induced shedding of heparin-binding (HB) EGF, addition of exogenous PDI decreased it, and PDI addition to recombinant ADAM17 reduced basal cleavage of a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) peptide. These changes correlated with altered topology of antibody epitopes outside of, but not within, the catalytic domain (14). However, induced HB-EGF cleavage could have also resulted from enhanced interaction of the substrate with ADAM17 via the altered topology outside of the catalytic domain without requiring changes in protease activity. Neither study determined protease activity independent of substrate cleavage, still leaving us with uncertainty whether induced substrate cleavage truly requires enhanced protease activity. By using stopped-flow X-ray spectroscopy and other techniques, Solomon et al. showed that ADAM17 activity is primed by enzyme conformational changes induced by the substrate before proteolysis (22). Novel exosite inhibitors of ADAM17 activity that bind ADAM17 outside of the catalytic site and likely interfere with the binding of glycosylated moieties of the substrate have been developed (23). Both studies further support regulation of proteolysis on the substrate level.

Here we identify pathway components that distinguish substrates of ADAM17 and parse substrate selection from regulation of protease activity.

Results

shRNA Screen for Regulators of TGF-α Cleavage by ADAM17.

Phorbol ester (i.e., TPA) stimulates most PKC isoforms (-α, -β, -γ, -δ, -ε, -η, -θ and -μ), and is a commonly used cleavage stimulus in shedding studies. ADAM17 is the physiological effector of TPA-induced signals, whereas ADAM10 primarily responds to calcium signals (24, 25). To identify novel genes that regulate shedding downstream of PKC, we carried out a lentiviral shRNA gene knockdown screen targeting most human kinases and phosphatases and some of their associated components, probing their effect on TPA-induced cleavage of TGF-α, a classical ADAM17 substrate (24). Cleavage was measured with an extensively validated high-throughput 96-well FACS assay (18, 19) (Fig. S1A). We screened 3,500 unique lentiviral shRNAs carrying puromycin resistance for selection at >3× coverage with biological duplicates in human Jurkat cells expressing HA–TGF-α–EGFP. Genes were targeted with three to five individual shRNAs per gene and selected with puromycin. A shRNA targeting lacZ, a protein not present in mammalian cells (control-shRNA) was used as a control. After stimulation with TPA for 2 to 5 min, mean geometric red and green fluorescence of the cells was measured by FACS and normalized across samples by using z-scores. Cleavage was induced to approximately 50% of maximum to allow detection of cleavage activation or inhibition in the same screen. Assuming that most tested shRNAs would not affect cleavage, we selected targeted genes with two or more shRNAs that reproducibly scored at least 2 z-scores (for best shRNA) and 1.5 z-scores (for other shRNAs) above or below the mean z-score of all samples. A positive z-score identifies inhibitory shRNAs (cleavage-activating genes) and a negative z-score activating shRNAs (cleavage-inhibiting genes). A distribution of all shRNA red:green fluorescence z-scores is shown in Fig S1B. shRNAs that showed reproducible effects on TGF-α cleavage were retested after subcloning into an isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible lentiviral expression vector.

PKC-α and Protein Phosphatase 1 Inhibitor 14D Regulate Induced Cleavage of only Specific EGF Ligand ADAM17 Substrates, Including TGF-α, but Not Neuregulin.

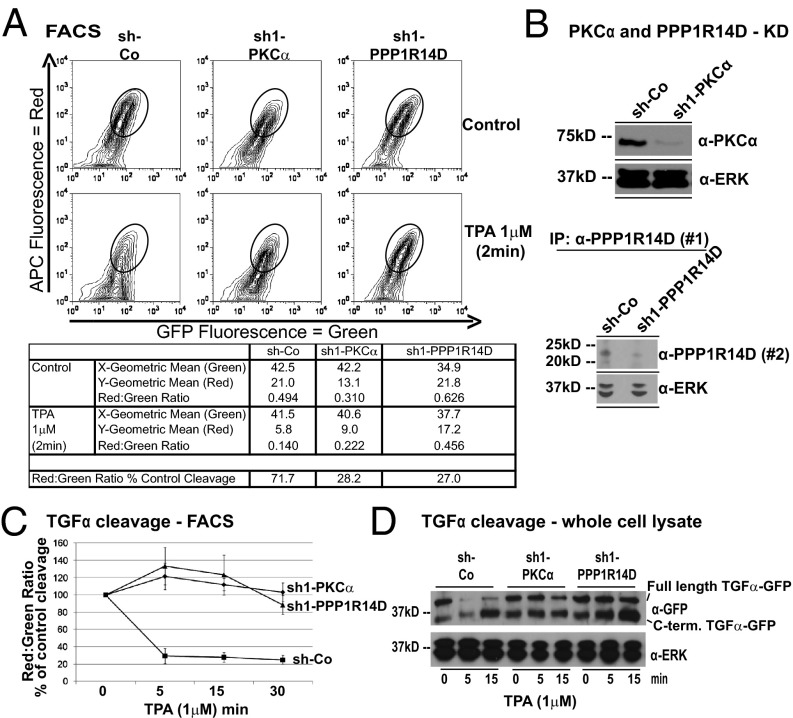

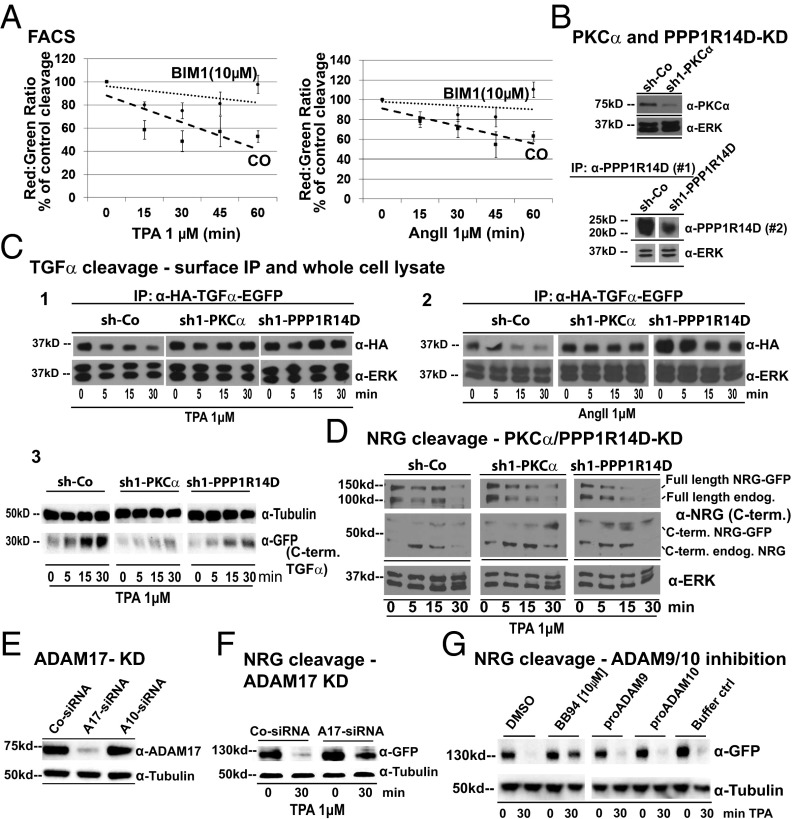

Our screen identified positive and negative regulators of TPA-induced TGF-α cleavage, including the cleavage activating genes PKC-α and protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) inhibitor 14D (PPP1R14D), a PP1 inhibitor that is activated by PKC phosphorylation (26, 27). Fig. 1A shows representative screen FACS plots of HA–TGF-α–EGFP-expressing Jurkat cells. The elliptical marker was added to highlight changes in the relevant plot area. In control-shRNA–expressing cells, the reduction of red fluorescence (ectodomain) by TPA compared with control-treated cells is dramatic, whereas green fluorescence (C terminus) is roughly maintained. In PKC-α and PPP1R14D knockdown cells (Fig. 1B shows Western blot confirmation), this fluorescence shift is largely absent, indicating maintained HA–TGF-α−EGFP ectodomain fluorescence on the cell surface, a result of blocked cleavage. The GFP signal as measured by FACS is slightly different between the cell lines as a result of effects on basal expression or basal cleavage of the reporter. This does not affect cleavage detection by red:green fluorescent ratio as it is highly linear over a wide range of reporter expression (18, 19). We also showed the effect of PKC-α or PPP1R14D knockdown in FACS time-course experiments (Fig. 1C) and in whole cell lysates using anti-GFP Western blots (Fig. 1D). In Fig. 1D, the Western blot shows two bands, an upper full-length HA–TGF-α–EGFP and a lower C-terminal cleavage product. In control shRNA-expressing Jurkat cells, the full-length band strongly diminishes (to approximately 10% of control) over 5 and 15 min, whereas the C-terminal cleavage product accumulates over the same time frame, suggesting strong cleavage. The full-length band appears to slightly recover at 15 min compared with 5 min of TPA, but the C-terminal cleavage product continues to accumulate at 15 min, further decreasing the full-length:C-terminal product ratio. A similar result can be seen in the FACS time-course experiments in Fig. 1C that plot the red:green ratio of HA–TGF-α–EGFP-expressing cells. The red signal stems from surface-stained full-length HA–TGF-α–EGFP, and the green signal stems from the C-terminal GFP fusion. The red signal is lost after cleavage (ectodomain lost in supernatant before FACS stain is carried out; Fig. S1A), whereas the GFP signal migrates with the C terminus after cleavage, as is also seen in the Western blot. Hence, the low red:green ratio at 15 min of the FACS plot mirrors the results from the Western blot when full-length:C-terminal product ratio is taken into account. In PKC-α or PPP1R14D knockdown Jurkat cell Western blots, the full-length band does not diminish by 5 min and shows some decrease at 15 min. This is reflected in the accumulation of C-terminal cleavage product particularly in the PPP1R14D knockdown cells. Our knockdown westerns show 90% to 100% knockdown for PKC-α and approximately 80% knockdown for PPP1R14D in these experiments (Fig. 1B). This could explain why PPP1R14D knockdown was less effective then PKC-α knockdown in blocking cleavage. Of note, the C-terminal cleavage product is already present in control-treated cells, reflecting basal cleavage, also seen in the control shRNA-expressing cells. We confirmed our results in HEK293T cells overexpressing the G protein-coupled angiotensin II (AngII) type 1 receptor known to activate PKC (28). Broad-spectrum inhibition of PKC isoforms by bisindolylmaleimide 1 (BIM1) indeed strongly inhibited TPA- and AngII-induced TGF-α cleavage as measured by FACS (Fig. 2A). PKC-α or PPP1R14D down-regulation (Fig. 2B) had the same effect as BIM1 in inhibiting induced TGF-α cleavage (Fig. 2C, 1 and 2). In the latter experiment, we used cell-surface anti-HA immunoprecipitation (IP) to detect full-length HA–TGF-α−GFP because detection of the small cleaved cell surface fraction of TGF-α was difficult in whole-cell lysates containing a large fraction of uncleaved intracellular TGF-α. However, we have been able to observe TPA-induced accumulation of C-terminal cleavage products in control shRNA-expressing cells that is significantly blocked in PKC-α or PPP1R14D knockdown cells (Fig. 2C, 3). Importantly, knockdown of either gene did not affect TPA-induced cleavage of neuregulin (NRG) in HEK cells (Fig. 2D), also an ADAM17 substrate (Fig. 2 E–G). We therefore hypothesized that PKC-α and PPP1R14D may act in the regulation of only a subset of ADAM17 substrates. We confirmed this by using specific ELISAs to detect different endogenous protein ectodomains cleaved by ADAM17 (Fig. S1 C and D) in the same sample supernatant of cells that express various cleaved metalloprotease substrates, including EGF ligands. In MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells that depend on EGF ligand cleavage for proliferation and express TGF-α, PKC-α, and PPP1R14D, PKC-α and PPP1R14D are indeed required for TPA-induced ADAM17 cleavage of TGF-α, HB-EGF, and amphiregulin (AR), but not for the basal cleavage of TNF receptor 1 (Fig. S2). In 12Z cells (which do not express TGF-α), both genes were required for the cleavage of HB-EGF (Fig. S3). Cleavage of the ADAM10 substrate c-Met was unaffected in both cell lines (Figs. S1–S3), suggesting that regulation by either gene is specific for ADAM17 substrates. We were unable to detect NRG cleavage with several different ELISAs in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Fig. 1.

shRNA screen targeting human phosphatases and kinases identifies PKC-α and PPP1R14D as regulators of TPA-induced TGF-α cleavage. (A) Representative FACS plots of control (sh-Co), PKC-α (sh1-PKC-α), or PPP1R14D (sh1-PPP1R14D) knockdown Jurkat cells expressing HA–TGF-α–EGFP with or without TPA (1 μM). x axis, green C-terminal fluorescence; y axis, red ectodomain fluorescence (anti-HA stain). Statistical analysis is shown in the table. (B) PKC-α (90–100%) and PPP1R14D (80%) shRNA knockdown by Western blot (densitometry) and (C) knockdown effect on TPA (1 μM)-induced TGF-α cleavage measured by FACS (red:green fluorescence ratio) or (D) by anti-GFP Western blot in whole-cell lysates [full-length HA–TGF-α–EGFP (39 kDa), C-terminal cleavage product (30 kDa)]. Further details are provided in the text. For all Western blots, we show one representative of three to five independent experiments. For FACS experiments, we show the mean of at least four independent experiments performed in triplicate; data are shown as percentage of control.

Fig. 2.

PKC-α and PPP1R14D regulate TPA- and AngII-induced TGF-α cleavage but not the cleavage of NRG. (A) TPA (1 μM) or AngII (1 μM)-induced TGF-α cleavage with or without broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor BIM1 (10 μM) measured by FACS. (B) PKC-α (90–100%) and PPP1R14D (70%) shRNA knockdown by Western blot (densitometry). (C) Knockdown effect on TPA (1 μM; 1) or AngII (1 μM; 2)-induced TGF-α cleavage measured by cell surface IP of full-length HA–TGF-α–EGFP and by detection of C-terminal cleavage products (3; shown only for TPA). (D) Effect of PKC-α and PPP1R14D knockdown on TPA-induced Flag–NRG–EGFP and endogenous NRG cleavage measured by C-terminal NRG Western blot. Full-length/C-terminal fragment: endogenous NRG (100 kDa/50 kDa) and Flag–NRG–EGFP (150 kDa/75 kDa). (E) ADAM17 (90–100%) siRNA knockdown by Western blot (densitometry) and (F) knockdown effect on TPA (1 μM)-induced Flag–NRG–EGFP cleavage measured by GFP Western blot. (G) Effect of broad-spectrum metalloprotease inhibition with batimastat (BB94, 10 μM) or of specific ADAM9 or ADAM10 inhibition with their cognate prodomains (pro-ADAM9, 270 nM; pro-ADAM10, 250 nM) on TPA-induced NRG cleavage measured by GFP Western blot. For all Western blots, we show one representative of three to five independent experiments. For FACS experiments, we show the mean of at least four independent experiments performed in triplicate. Data are shown as percentage of control.

PKC-δ–Dependent C-Terminal Serine Phosphorylation Regulates Induced NRG Cleavage.

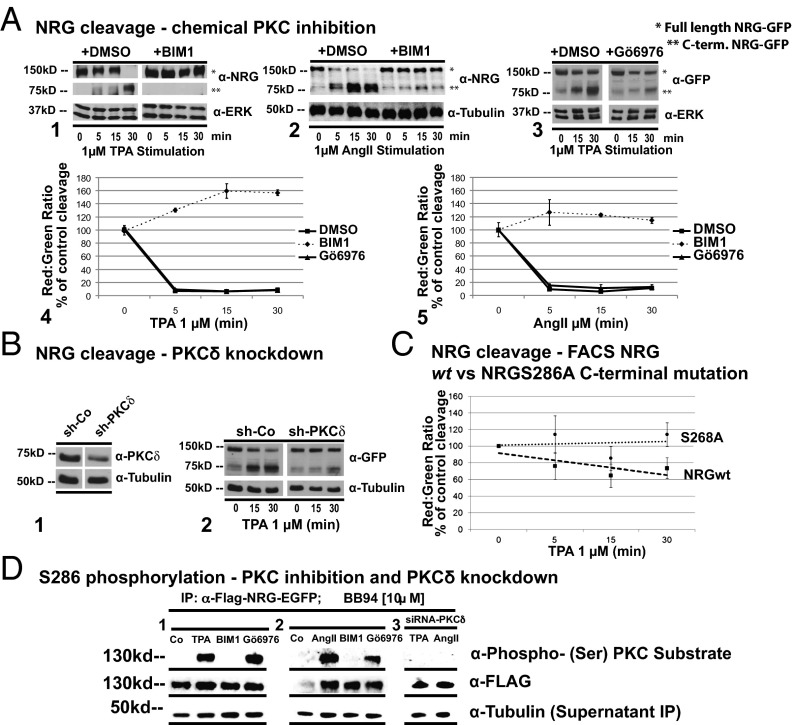

The broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor BIM1 blocks TPA- and AngII-induced NRG cleavage in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3A, 1 and 2). In contrast, and consistent with the lack of effect of PKC-α down-regulation (Fig. 2D), Gö6976, an inhibitor of only PKC-α and -β, did not block NRG cleavage (Fig. 3A, 3). We confirmed these results for BIM1 and Gö6976 detecting NRG cleavage by FACS (Fig. 3 A, 4 and 5). We therefore asked which other TPA-regulated PKC isoforms might be responsible. PKC-δ down-regulation strongly blocked TPA-induced NRG cleavage (Fig. 3B, 1 and 2), whereas the knockdown of other PKC isoforms had no effect. By using a phospho-specific PKC consensus site antibody, we previously showed that TPA induces a serine phosphorylation on the C terminus of NRG before cleavage, which is sensitive to BIM1 inhibition (18). Serine 286 (S286) is contained in the only sequence in the NRG C terminus matching the consensus PKC phosphorylation site. Indeed, mutation of S286 to alanine blocked TPA-induced NRG cleavage as measured by FACS (Fig. 3C). We confirmed these findings by immunofluorescence and Western blot. The TPA- and AngII-induced S286 phosphorylation was prevented by BIM1, but not by the PKC-α,β inhibitor Gö6976 (Fig. 3D, 1 and 2), consistent with their respective effects on NRG cleavage (Fig. 3A, 1–5). In contrast, PKC-δ knockdown abolished AngII- or TPA-induced S286 phosphorylation (Fig. 3D, 3), suggesting that PKC-δ activity establishes S286 phosphorylation.

Fig. 3.

PKC-δ and a PKC-δ–dependent serine phosphorylation of the NRG C terminus regulate its cleavage. (A) TPA (1 μM) or AngII (1 μM)-induced NRG cleavage with or without the broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor BIM1 (10 μM) or specific PKC-α,β inhibitor Gö6976 (10 μM) measured by C-terminal NRG Western blot, Flag-NRG-EGFP (150 kd/75 kd; 1–3), or FACS (4 and 5). (B) PKC-δ (60%) knockdown by Western blot (densitometry; 1) and knockdown effect on TPA-induced NRG cleavage (2). (C) Mutation of serine 286 to alanine in the NRG C terminus results in inhibition of TPA (1 μM)-induced cleavage (dotted line, NRGS286A; dashed line, NRG WT). (D) Effects of BIM1, Gö6976, or PKC-δ siRNA knockdown on S286 phosphorylation measured by Western blot with a PKC-site phospho-specific antibody: TPA (1 μM; 1 and 3) or AngII (1 μM; 2 and 3). For all Western blots, we show one representative of three to five independent experiments. For the FACS experiments, we show the mean of at least four independent experiments performed in triplicate; data are shown as percentage of control.

TPA and AngII Induce Inhibition of PP1.

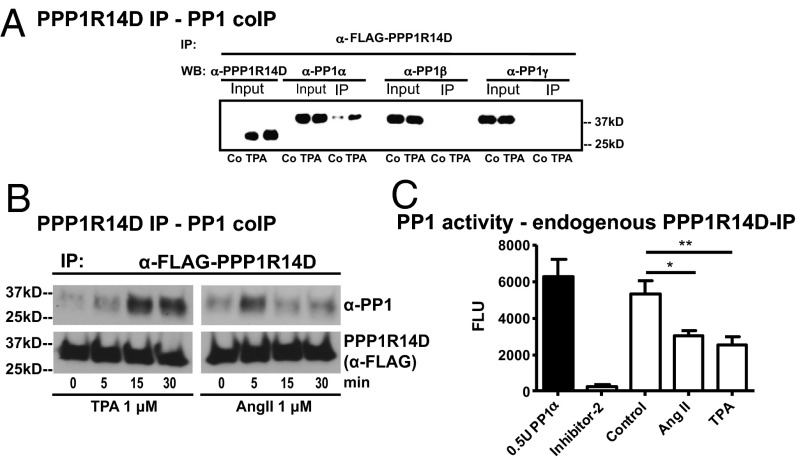

Phosphorylation of serine 58 in PPP1R14D by PKC activates the PP1 inhibitor by inducing a conformational change (26, 27), allowing binding of the inhibitor to a specific PP1 complex. In IP experiments, PP1-α but not PP1-β or PP1-γ was coprecipitated strongly with Flag-PPP1R14D from TPA-treated Jurkat cells and TPA- or AngII-treated HEK293T cells compared with controls (Fig. 4 A and B), suggesting that PP1α is the downstream effector of PPP1R14D. We confirmed the inhibitory effect of activated PPP1R14D in a biochemical PP1-α assay in vitro, by using a FRET peptide substrate that only reveals its fluorescence when dephosphorylated. Only an exogenously applied PP1 inhibitor (inhibitor-2) or endogenous PPP1R14D immunoprecipitated from TPA- or AngII-treated cells significantly inhibited PP1-α activity; however, PPP1R14D precipitated from control cells did not (Fig. 4C). In contrast to knockdown of PPP1R14D, a regulator of only specific PP1-α–containing complexes, PP1-α knockdown itself was not well tolerated in Jurkat or HEK293T cells, leading to significantly decreased cell proliferation and increased cell death. PP1-α carries out many cellular dephosphorylation reactions, affecting multiple cellular functions (29).

Fig. 4.

TPA and AngII induce PP1 inhibition. (A) PP1-α but not PP1-β or PP1-γ (detected by specific antibodies) coimmunoprecipitate with Flag–PPP1R14D in TPA (1 μM)-treated Jurkat cells (PPP1R14D IP input is detected by PPP1R14D antibody) or (B) HEK293T cells (shown for PP1-α only). (C) PP1-α phosphatase assay: endogenous PPP1R14D was immunoprecipitated from TPA (1 μM) or AngII (1 μM)-treated cells and incubated with recombinant PP1-α. Phosphatase activity was measured with a FRET peptide that fluoresces only when dephosphorylated by PP1. Inhibitor-2 was used as a positive control for PP1 inhibition. For all Western blots, we show one representative of three to five independent experiments. For the PP1 activity assay, we show the mean of at least four independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Taken together, our findings strongly suggest (i) that regulation of substrate cleavage by modulating protease activity may not suffice to explain the observed specificity of cleavage, (ii) that the identified regulators may act in intracellular signaling pathways that address the C terminus of substrates to regulate cleavage, and (iii) that ADAM17 substrate cleavage is regulated and made specific by distinct PKC isoforms, PPP1R14D and PP1-α.

PKC-α and PPP1R14D Regulate ADAM17 Cleavage Without Significantly Affecting Protease Activity.

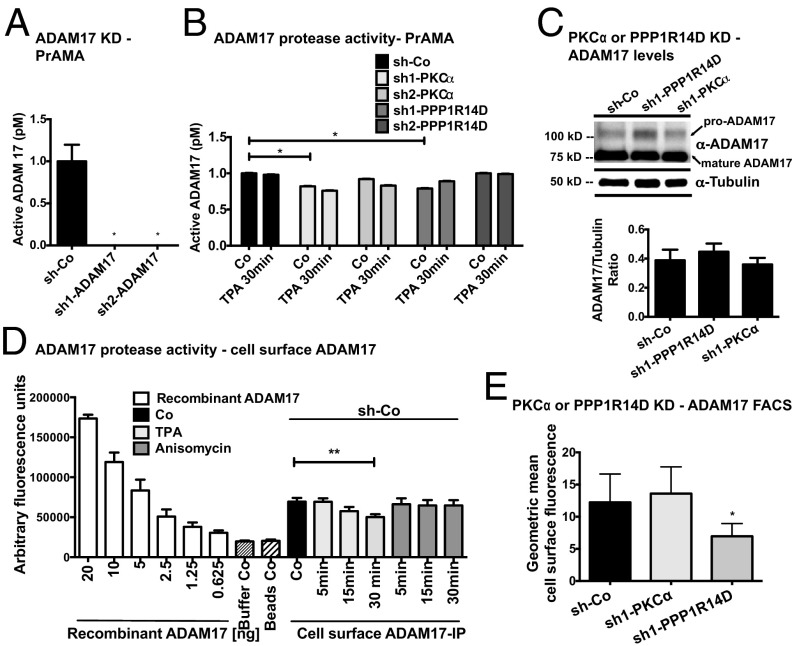

Given our finding that ADAM17 substrates are specifically selected, does this require, in addition, regulation at the level of protease activity? We measured basal and TPA-induced protease activity by using proteolytic activity matrix analysis (PrAMA). PrAMA allows measurement of particular protease activities independently of measuring specific physiological substrate cleavage (30). This technique uses a panel of FRET-based peptide substrates that emit fluorescence upon cleavage. Peptide substrates can be incubated directly with live cells, with generated fluorescence measured in a plate reader. Specific protease-associated cleavage profiles were developed and validated with purified proteases in vitro and in ADAM-KO cells in vivo. We used five different FRET substrates that vary in their specificity for ADAMs and matrix metalloproteinases to infer the activity of ADAM17. Knockdown of ADAM17 indeed strongly reduced PrAMA-inferred ADAM17 protease activity in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5A). Knockdown of ADAM17 (approximately 80%) for both shRNAs used was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. S1D). However, baseline live-cell ADAM17 protease activity was only mildly reduced by 0% to 20% in PKC-α or PPP1R14D MDA-MB-231 knockdown cells (significant in only one of two shRNAs tested per gene) compared with control (Fig. 5B). Even more surprisingly, 30 min TPA stimulation, although able to induce substantial substrate cleavage in control cells (Figs. 1–3 and Figs. S2–S4), did not increase protease activity under any condition, but rather decreased it to a small degree (Fig. 5B). We obtained similar results by using immunoprecipitated cell-surface ADAM17 and one relevant FRET substrate for cleavage detection. TPA or anisomycin, an inducer of cell stress, did not increase activity of cell surface ADAM17 at 5, 15, or 30 min, but a small decrease in protease activity was detected at 30 min in TPA-stimulated samples (Fig. 5C). Basal cell surface ADAM17 activity showed only small differences in control and knockdown cells, similar to live-cell PrAMA (Fig. S4). Overall levels of mature ADAM17 were unchanged by PKC-α or PPP1R14D knockdown in MDA-MB-231 cells, with only minor changes in the ratio of pro- to mature form (Fig. 5D), arguing against transcriptional down-regulation or reduced ADAM17 maturation as explanations for the small reductions in protease activity. Cell surface levels of ADAM17, another factor that could influence cell surface protease activity, were equal in control and PKC-α knockdown cells and were moderately reduced with PPP1R14D down-regulation (Fig. 5E). As basal protease activity in PPP1R14D knockdown cells is not significantly affected (Fig. 5B), this suggests that surface levels of active ADAM17 are in saturation. Nonetheless, PPP1R14D may regulate ADAM17 surface levels.

Fig. 5.

PKC-α and PPP1R14D regulate ADAM17 cleavage without significantly affecting protease activity. Determination of ADAM17 protease activity by PrAMA in (A) ADAM17 or (B) PKC-α and PPP1R14D shRNA knockdown vs. control cells. (C) Cell-surface ADAM17 protease activity was detected by ADAM17 surface IP and assayed with one relevant FRET substrate. (D) Effect of PKC-α or PPP1R14D knockdown on pro-ADAM17 (100 kDa) and mature ADAM17 (75 kDa) expression levels measured by C-terminal ADAM17 Western blot and (E) by detecting cell surface levels of ADAM17 by FACS (ADAM17 ectodomain antibody). Cells were treated as indicated. For all Western blots, we show one representative of three to five independent experiments. ADAM17/tubulin ratios were determined by densitometry of three independent Western blots. For the protease activity assays, we show the mean of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

In summary, our results indicate that the predominant effects of PKC-α and PPP1R14D on substrate cleavage are not mediated by changes in ADAM17 expression, maturation, or cell surface expression, nor are they caused by significant regulation of ADAM17 protease activity. The implication is that PKC-α and PPP1R14D (and PP1-α) directly or indirectly act on the substrate or on a third interacting protein required for cleavage regulation.

Discussion

Our results support at least two principal conclusions, as noted below.

Induced Shedding May Not Require Significant Changes in ADAM17 Protease Activity.

In the present study, live-cell PrAMA or studies with immunoprecipitated cell surface ADAM17 showed a reduction of only 0% to 20% of basal protease activity with PKC-α or PPP1R14D down-regulation compared with control cells and small decreases in protease activity in response to 30-min TPA stimulation. Decreases of ADAM17 surface levels in response to TPA stimulation, either by endocytosis or possibly cleavage, have been reported before (14, 31). More importantly, even without increases in protease activity, strong TPA-induced substrate cleavage (1.5- to fivefold vs. control) was observed. PKC-α or PPP1R14D down-regulation blocked this proteolysis without inducing significant changes in protease activity, at least not as measured with currently available techniques that allow determination of protease activity independent of measuring physiological substrate cleavage. This indicates that these signaling components regulate substrate cleavage independently of a major effect on protease activity. In live-cell PrAMA experiments using 30-min TPA stimulations that we published previously, TPA also enhanced ADAM17 protease activity only slightly (30), yet substrate cleavage was increased much more significantly (18). In contrast to our studies, the application of cell stress including by anisomycin for 60 min (16) increased protease activity by 20% to 25% (measured with immunoprecipitated ADAM17 and one FRET-peptide substrate). Concurrently, cell stress produced a small to moderate increase of ADAM17 surface levels not observed in our study that likely account for the observed small increases in protease activity after 60 min of stimulation. However, despite only small changes in protease activity in this study, cell stress-induced TGF-α cleavage was increased five to 10 fold vs. control cells. These findings further support the notion that substrate cleavage is regulated independently of a major change in protease activity.

Different Signaling Modules Select Distinct Substrates for ADAM17 Cleavage.

PKC-α and PPP1R14D act only in ADAM17 cleavage of TGF-α, HB-EGF, and AR, and possibly act in a signaling cascade by inhibiting PP1-α. PKC-δ is part of a different signaling module that regulates ADAM17 cleavage of NRG. PKC-α and PKC-δ are both activated by TPA, yet the signaling modules they drive are different. This would lend a satisfying explanation to the conundrum of how specific substrate cleavage in response to the same cleavage stimulus, TPA, could be achieved by only one metalloprotease, ADAM17. Additionally, different stimulus-specific responses in substrate cleavage (e.g., osmotic stress, G protein-coupled receptor activation) could be explained by stimulus-dependent engagement of different signaling modules that act on distinct subsets of substrates and/or act in different ways on the same substrate, e.g., by posttranslational modification. Cleavage of substrates depends, of course, on the level of mature enzyme on the cell surface. This level is regulated by ADAM gene expression, transport, and maturation, as well as by internalization. Signal transduction pathways affect all these processes (e.g., ref. 32). The rapid choice of substrates for cleavage must, however, be defined by their posttranslational modifications. Such selection likely involves modifications of the C terminus of substrates, as shown here for NRG, or, alternatively, of the C terminus of yet unidentified regulatory proteins that interact with the substrates. In contrast to many substrates, the C terminus of ADAM17 is not required for induced or basal cleavage (25), although conflicting results on the regulatory role of a C-terminal threonine 735 phosphorylation have been reported (16, 17, 32). To date, a number of C-terminal regulatory events on substrates that regulate shedding and could be influenced by intracellular signaling have been described. Phosphorylated serine residues and linkage to the actin cytoskeleton via ezrin/radixin/moesin proteins are important for PKC-dependent shedding of L-selectin (33). Calmodulin is constitutively bound to the cytoplasmic tails of L-selectin and angiotensin-converting enzyme, and its dissociation induced by calmodulin kinase inhibitors or TPA activates their shedding (34, 35). Shedding of CD44, EGF, betacellulin, N-cadherin, and IL-6R are inducible by calmodulin kinase inhibitors and calcium ionophores (36–38). Regulation of substrate cell surface levels also affects cleavage of certain substrates. As examples, the APP homologue APLP1 binds to APP through a conserved motif in the cytoplasmic domain and increases the shedding of APP by reduction of its endocytosis (39). Monoubiquitination of AR’s C terminus induces its immediate endocytosis and thereby rapidly blocks its ectodomain cleavage by ADAM17 (40). However, not all substrates require their C terminus for shedding and not all C-terminal phosphorylation events induced by shedding stimuli regulate cleavage [e.g., IL-6 receptor (41), TNF-α receptor II (42), HB-EGF (43)]. Because ADAM17 and ADAM10 also do not require their C-termini for stimulus-induced cleavage (25), these findings suggest the existence of other “third” regulatory proteins that receive signaling input, and/or that C termini of some substrates contain negative regulatory signals for cleavage that are missing after C-terminal deletion. As TPA induces many shedding events, it is not surprising that PKC isozymes have been implicated. Only few studies have identified specific PKC isoforms involved in cleavage regulation, but none clearly distinguished whether protease or substrates were the target of regulation [e.g., PKC-ε/TNF-α (44); PKC-δ/HB-EGF (45); PKC-δ and PKC-ε/IL-6R (46)]. In concordance with our study, PKC-α siRNA knockdown blocks TPA-induced HB-EGF cleavage (47), and PKC-δ and phosphorylated C-terminal serine residues regulate cleavage of chicken NRG in neuronal cells (48).

In summary, we show that the regulatory proteins PKC-α, PPP1R14D, and PKC-δ specifically affect the cleavage of only select ADAM17 substrates without significantly affecting protease activity. This observation offers itself as a new avenue for therapeutic intervention independent of the protease and possibly specific for a particular disease-causing substrate.

Materials and Methods

SI Materials and Methods describes materials, retrovirus/lentivirus production and infection, IP, Western blotting and ELISAs, PP1 biochemical assay, immunoprecipitated cell-surface ADAM17 protease assay, FACS, and shRNA FACS screen.

PrAMA.

For live-cell PrAMA, IPTG-induced MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were seeded in a 384-well clear-bottom black-walled plate. The next day, samples were stimulated with internally quenched FRET substrates (5 µM) alone or with TPA (1 µM) for 30 min. Substrates were also added to no-cell (negative control) and trypsin (positive control). Fluorescence readings were obtained every 10 min for 2 h at 37 °C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Swanson Biotechnology Center for help with image analysis; Issei Komuro for providing HEK293T- angiotensin II type 1 receptor cells; Glenn Paradis and Patti Wisniewski (FACS Facility), Kathleen Ottina (BL2plus Facility), and Jen Grenier (Broad Institute) for their help; Prat Thiru and Bingbing Yuan for help with biostatistical analysis; and Peter Herrlich for critical reading. This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R00DK077731 and R01-CA96504.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1307478110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Overall CM, Blobel CP. In search of partners: Linking extracellular proteases to substrates. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(3):245–257. doi: 10.1038/nrm2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy G. The ADAMs: Signalling scissors in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):929–941. doi: 10.1038/nrc2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein T, Bischoff R. Active metalloproteases of the A Disintegrin and Metalloprotease (ADAM) family: Biological function and structure. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(1):17–33. doi: 10.1021/pr100556z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider MR, Wolf E. The epidermal growth factor receptor ligands at a glance. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218(3):460–466. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higashiyama S, Nanba D, Nakayama H, Inoue H, Fukuda S. Ectodomain shedding and remnant peptide signalling of EGFRs and their ligands. J Biochem. 2011;150(1):15–22. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McBryan J, Howlin J, Napoletano S, Martin F. Amphiregulin: Role in mammary gland development and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2008;13(2):159–169. doi: 10.1007/s10911-008-9075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGowan PM, et al. ADAM-17 predicts adverse outcome in patients with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(6):1075–1081. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asakura M, et al. Cardiac hypertrophy is inhibited by antagonism of ADAM12 processing of HB-EGF: Metalloproteinase inhibitors as a new therapy. Nat Med. 2002;8(1):35–40. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan X, Morgan JP. Neuregulin1 as novel therapy for heart failure. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(18):1808–1817. doi: 10.2174/138161211796391010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laouari D, et al. TGF-alpha mediates genetic susceptibility to chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(2):327–335. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saftig P, Reiss K. The “A Disintegrin And Metalloproteases” ADAM10 and ADAM17: Novel drug targets with therapeutic potential? Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90(6-7):527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Gall SM, et al. ADAM17 is regulated by a rapid and reversible mechanism that controls access to its catalytic site. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(pt 22):3913–3922. doi: 10.1242/jcs.069997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy G. Regulation of the proteolytic disintegrin metalloproteinases, the ‘Sheddases’. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20(2):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willems SH, et al. Thiol isomerases negatively regulate the cellular shedding activity of ADAM17. Biochem J. 2010;428(3):439–450. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu P, Liu J, Sakaki-Yumoto M, Derynck R. TACE activation by MAPK-mediated regulation of cell surface dimerization and TIMP3 association. Sci Signal. 2012;5(222):ra34. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu P, Derynck R. Direct activation of TACE-mediated ectodomain shedding by p38 MAP kinase regulates EGF receptor-dependent cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2010;37(4):551–566. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Díaz-Rodríguez E, Montero JC, Esparís-Ogando A, Yuste L, Pandiella A. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylates tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme at threonine 735: A potential role in regulated shedding. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(6):2031–2044. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-11-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dang M, et al. EGF ligand release by substrate-specific a disintegrin and metalloproteases (ADAM) metalloproteases involves different PKC isoenzymes depending on the stimulus. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(20):17704–17713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrlich A, Klinman E, Fu J, Sadegh C, Lodish H. Ectodomain cleavage of the EGF ligands HB-EGF, neuregulin1-beta, and TGF-alpha is specifically triggered by different stimuli and involves different PKC isoenzymes. FASEB J. 2008;22(12):4281–4295. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-113852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoda M, et al. Systemic overexpression of TNFα-converting enzyme does not lead to enhanced shedding activity in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blobel CP, Carpenter G, Freeman M. The role of protease activity in ErbB biology. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(4):671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon A, Akabayov B, Frenkel A, Milla ME, Sagi I. Key feature of the catalytic cycle of TNF-alpha converting enzyme involves communication between distal protein sites and the enzyme catalytic core. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(12):4931–4936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700066104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minond D, et al. Discovery of novel inhibitors of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17) using glycosylated and non-glycosylated substrates. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(43):36473–36487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Gall SM, et al. ADAMs 10 and 17 represent differentially regulated components of a general shedding machinery for membrane proteins such as transforming growth factor alpha, L-selectin, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(6):1785–1794. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-11-1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horiuchi K, et al. Substrate selectivity of epidermal growth factor-receptor ligand sheddases and their regulation by phorbol esters and calcium influx. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(1):176–188. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eto M. Regulation of cellular protein phosphatase-1 (PP1) by phosphorylation of the CPI-17 family, C-kinase-activated PP1 inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(51):35273–35277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.059972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Q-R, et al. GBPI, a novel gastrointestinal- and brain-specific PP1-inhibitory protein, is activated by PKC and inactivated by PKA. Biochem J. 2004;377(pt 1):171–181. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchiyama-Tanaka Y, et al. Angiotensin II signaling and HB-EGF shedding via metalloproteinase in glomerular mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2001;60(6):2153–2163. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bollen M, Peti W, Ragusa MJ, Beullens M. The extended PP1 toolkit: Designed to create specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(8):450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MA, et al. Proteolytic activity matrix analysis (PrAMA) for simultaneous determination of multiple protease activities. Integr Biol (Camb) 2011;3(4):422–438. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00083c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doedens JR, Black RA. Stimulation-induced down-regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(19):14598–14607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall KC, Blobel CP. Interleukin-1 stimulates ADAM17 through a mechanism independent of its cytoplasmic domain or phosphorylation at threonine 735. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Killock DJ, Ivetić A. The cytoplasmic domains of TNFalpha-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM17) and L-selectin are regulated differently by p38 MAPK and PKC to promote ectodomain shedding. Biochem J. 2010;428(2):293–304. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahn J, Walcheck B, Migaki GI, Jutila MA, Kishimoto TK. Calmodulin regulates L-selectin adhesion molecule expression and function through a protease-dependent mechanism. Cell. 1998;92(6):809–818. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matala E, Alexander SR, Kishimoto TK, Walcheck B. The cytoplasmic domain of L-selectin participates in regulating L-selectin endoproteolysis. J Immunol. 2001;167(3):1617–1623. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagano O, et al. Cell-matrix interaction via CD44 is independently regulated by different metalloproteinases activated in response to extracellular Ca(2+) influx and PKC activation. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(6):893–902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reiss K, et al. ADAM10 cleavage of N-cadherin and regulation of cell-cell adhesion and beta-catenin nuclear signalling. EMBO J. 2005;24(4):742–752. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanderson MP, et al. ADAM10 mediates ectodomain shedding of the betacellulin precursor activated by p-aminophenylmercuric acetate and extracellular calcium influx. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(3):1826–1837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neumann S, et al. Amyloid precursor-like protein 1 influences endocytosis and proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(11):7583–7594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukuda S, Nishida-Fukuda H, Nakayama H, Inoue H, Higashiyama S. Monoubiquitination of pro-amphiregulin regulates its endocytosis and ectodomain shedding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;420(2):315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Müllberg J, et al. The soluble human IL-6 receptor. Mutational characterization of the proteolytic cleavage site. J Immunol. 1994;152(10):4958–4968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crowe PD, VanArsdale TL, Goodwin RG, Ware CF. Specific induction of 80-kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor shedding in T lymphocytes involves the cytoplasmic domain and phosphorylation. J Immunol. 1993;151(12):6882–6890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, et al. Cytoplasmic domain phosphorylation of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. Cell Struct Funct. 2006;31(1):15–27. doi: 10.1247/csf.31.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wheeler DL, Ness KJ, Oberley TD, Verma AK. Protein kinase Cepsilon is linked to 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha ectodomain shedding and the development of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in protein kinase Cepsilon transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63(19):6547–6555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izumi Y, et al. A metalloprotease-disintegrin, MDC9/meltrin-gamma/ADAM9 and PKCdelta are involved in TPA-induced ectodomain shedding of membrane-anchored heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. EMBO J. 1998;17(24):7260–7272. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thabard W, Collette M, Bataille R, Amiot M. Protein kinase C delta and eta isoenzymes control the shedding of the interleukin 6 receptor alpha in myeloma cells. Biochem J. 2001;358(pt 1):193–200. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kveiborg M, Instrell R, Rowlands C, Howell M, Parker PJ. PKCα and PKCδ regulate ADAM17-mediated ectodomain shedding of heparin binding-EGF through separate pathways. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e17168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Esper RM, Loeb JA. Neurotrophins induce neuregulin release through protein kinase Cdelta activation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(39):26251–26260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.