Abstract

ABCB10 is one of the three ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters found in the inner membrane of mitochondria. In mammals ABCB10 is essential for erythropoiesis, and for protection of mitochondria against oxidative stress. ABCB10 is therefore a potential therapeutic target for diseases in which increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production and oxidative stress play a major role. The crystal structure of apo-ABCB10 shows a classic exporter fold ABC transporter structure, in an open-inwards conformation, ready to bind the substrate or nucleotide from the inner mitochondrial matrix or membrane. Unexpectedly, however, ABCB10 adopts an open-inwards conformation when complexed with nonhydrolysable ATP analogs, in contrast to other transporter structures which adopt an open-outwards conformation in complex with ATP. The three complexes of ABCB10/ATP analogs reported here showed varying degrees of opening of the transport substrate binding site, indicating that in this conformation there is some flexibility between the two halves of the protein. These structures suggest that the observed plasticity, together with a portal between two helices in the transmembrane region of ABCB10, assist transport substrate entry into the substrate binding cavity. These structures indicate that ABC transporters may exist in an open-inwards conformation when nucleotide is bound. We discuss ways in which this observation can be aligned with the current views on mechanisms of ABC transporters.

Keywords: ABC mitochondrial erythroid, X-ray crystallography, human membrane protein structure, nucleotide complex, cardiolipin

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters move small molecules, ions, hormones, lipids, and drugs across cell membranes, and have diversified to act as ion channels and components of multiprotein complexes (1, 2). ABC transporters have critical roles in many diseases, including juvenile diabetes (3), cystic fibrosis (4), and drug resistance in cancer (5). ABC transporters are ubiquitous proteins, bacteria having several hundred examples and humans having 48 homologs (6). These diverse proteins share a common architecture with two nucleotide binding domains (NBDs) and two transmembrane domains (TMDs). The NBDs bind and hydrolyze ATP, providing the energy to move substrates across membranes against a concentration gradient. The TMDs are more diverse, with several possible folds in bacteria, which provide binding sites for a broad range of substrates (reviewed in refs. 1 and 2). ABC transporters function by an alternating access mechanism, where the TMD substrate binding sites alternate between outward- and inward-facing conformations (7). Structures of ABC transporters with the exporter fold have been obtained without bound nucleotide in the open-inwards conformation (8–10) and with nucleotides bound in the open-outwards conformation (9, 11). However, the role of conformational changes, the mechanism by which ATP hydrolysis drives transport and the sequence of substrate and nucleotide binding remain controversial (2).

ABCB10 (also known as ABC mitochondrial erythroid, ABC-me, mABC2, or ABCBA) is one of the three ABC transporters found in the inner membrane of human mitochondria, with the NBDs inside the mitochondrial matrix (12, 13). Mitochondria synthesize ATP, a process that produces toxic reactive oxygen species, which damage mitochondrial DNA; they are also the site of synthesis of metabolites, such as heme and lipids. ABCB10 expression is induced during erythroid differentiation and overexpression increases hemoglobin synthesis (12). However, ABCB10 is also expressed in many nonerythroid tissues, suggesting additional roles not related to hemoglobin synthesis (13, 14). Interestingly, recent reports identified ABCB10 as a key player in protection against oxidative stress and processes intimately related to mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation, such as cardiac recovery after ischemia and reperfusion (15, 16). ABCB10 knockout mice die at 12.5-d gestation, and were anemic at day 10.5, during a period where primitive erythropoiesis would normally occur (14). A potential role for ABCB10 would be export of a heme biosynthesis intermediate, in which case ABCB10−/− mice would not be able to synthesize hemoglobin. However, ABCB10−/− mouse embryos do still produce a minor population of hemoglobinized erythroid precursors, so a low level of hemoglobin synthesis still occurs in the absence of ABCB10. Another role proposed for ABCB10 or potential homologs is stabilization of the iron transporter mitoferrin-1 (SLC25A37) (17, 18). A study of the yeast homolog of ABCB10 multidrug resistance-like 1 (41% identity) (19) suggested that the substrates of ABCB10 may be peptides of 6–20 amino acids that result from digestion of proteins by the m-AAA protease in the mitochondrial matrix (20). To improve our understanding of ABCB10 function and to facilitate the identification of substrates, we have solved the crystal structure of human ABCB10 in complex with nucleotide analogs and in a ligand-free, apo form. These structures have given us an unexpected conformation for nucleotide analog complexes and new insights into the transport cycle for ABC transporters of the exporter fold.

Results

Structure ABCB10 in Complex With Nucleotide Analogs and Without Bound Substrate.

To solve the structure of ABCB10, we expressed the protein in insect cells without the N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence as this improved protein yields. Two constructs of ABCB10 were purified in the detergent dodecyl maltoside (DDM) with the addition of either cholesteryl-hemisuccinate (CHS) or the mitochondrial lipid cardiolipin (CDL). We obtained crystals of ABCB10 both without nucleotide analogs and in the presence of the ATP analogs adenosine-5′(βγ-imido)triphosphate (AMPPNP) or β-γ-methyleneadenoside 5′-triphosphate (AMPPCP) (Table S1). Initially we solved the structure using plate-form crystals, which were phased by isomorphous replacement using a single mercury derivative. We subsequently obtained rod-form crystals that were solved by molecular replacement. The structure solution methods are summarized in Materials and Methods and are described in detail in SI Materials and Methods. Crystallographic statistics are available in Table S1 and the quality of maps is shown in Fig. S1.

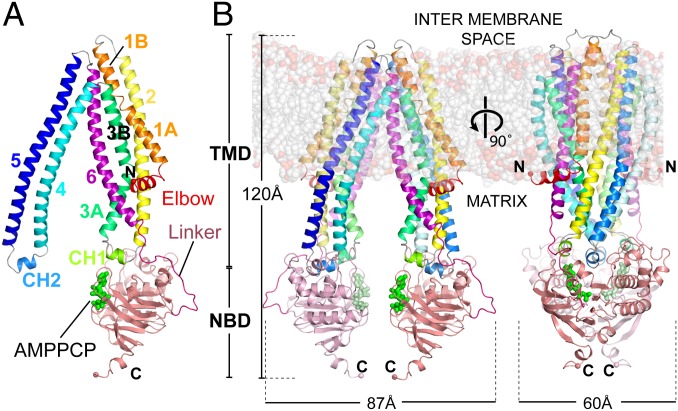

The overall fold of ABCB10 (Fig. 1A) is common to most eukaryotic ABC transporters and some bacterial exporters, and was previously observed for the bacterial multidrug transporter Sav1866 (11), the lipid flippase MsbA (9), and the mouse multidrug efflux protein P-glycoprotein (mP-gp) (8) and its Caenorhabditis elegans homolog (ceP-gp) (10). The ABCB10 fold consists of a short N-terminal α-helix, lying parallel to the plane of the membrane, followed by six long transmembrane α-helices (TMH) that traverse the lipid bilayer and project a further 30 Å into the mitochondrial matrix. The two monomers are interconnected by a domain swap where TMH4 and TMH5 interact with TMH1–3 and TMH6 from the other half of the dimer (Fig. 1B). The TMD is connected to the C-terminal NBD by an extended linker. The C-terminal domain adopts a classic NBD fold for an ABC transporter, with a RecA-like core subdomain, an α-helical subdomain, and a disordered C terminus. ABCB10 is a homodimeric half transporter and, in both the crystal forms, there is one monomer in the asymmetric unit. The dimer is generated by a crystallographic twofold axis, so the two halves of the dimer form a symmetrical structure (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Structure of ABCB10 in complex with the nonhydrolysable nucleotide analog AMPPCP, showing that ABCB10 is in an open conformation, even when it is bound to nucleotide analogs. Cartoon representations of the ABCB10/AMPPCP complex monomer (A) and homodimer (B) as seen in the rod-form B crystal structure. The structures have a single monomer in the asymmetric unit, the dimer is generated by a crystallographic twofold.

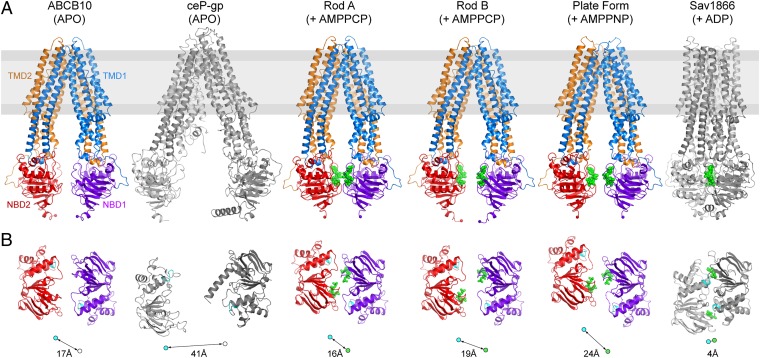

Although ABC transporters of the exporter family have the same overall fold, they adopt radically different conformations during the transport cycle as they move from open-inwards to an open-outwards state, allowing the transporters to bind substrate on one side of the membrane and release the substrate on the other side. In the absence of nucleotide analogs, an open-inwards conformation has been observed where the NBDs are not in contact and the molecule forms an extensive substrate binding cavity facing the NBDs. This is the conformation we observe for our nucleotide-free ABCB10 structure (Fig. 2A) and was previously observed for MsbA (9), mP-gp (8), and ceP-gp (10) (Fig. 2A). The alternate open-outward conformation was found for complexes of ADP, ADP/vanadate, and AMPPNP with Sav1866 (11) (Fig. 2A) and MsbA (9). In the latter conformation, the NBDs are closely packed with two nucleotides sandwiched between the NBDs at the interface between the RecA-like core subdomain of one NBD and the α-helical subdomain of the second (Fig. 2B). In addition, a heterodimeric ABC transporter, TM287/288, from the thermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima has been solved in an intermediate open-inwards conformation with AMPPNP bound only to the noncanonical, high ATP affinity site, not to the catalytic site. In this case the NBDs are in contact at the high-affinity ATP binding site, but not at the catalytic site (21).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the structures of the ABCB10 homodimer in the absence (apo) and presence of bound nucleotide analogs, with the structures of ceP-gp in the open-inwards conformation [PDB ID code: 4F4C (10)] and Sav1866 [PDB ID code 2HYD (11)] in the open-outwards conformation. Transporters are viewed perpendicular to their (pseudo) twofold symmetry axes. (B) Alignment of NBDs of the structures shown in A. viewed looking toward the membrane. The ABCB10 monomers (blue/purple and orange/red respectively), nucleotides (green), and the NBD’s C-loop (cyan) are highlighted. The black lines/circles below each NBD pair indicate the translation required to bring the NBDs in the closed conformation for catalysis [the distance is the separation between the nucleotide γ-phosphate (green) and the C-α of the first glycine in the catalytic C loop of the adjacent NBD (cyan)]. An additional rotational component is also required for proper alignment of the NBDs in the closed state. Where trinucleotide is not present in the structure, the position of the γ-phosphate has been inferred by superposition of the AMPPCP complex. The C-terminal extension in the Sav1866 structure has been omitted for clarity.

Unexpectedly, ABCB10 in complex with nucleotide analogs is in an inward-facing conformation with the NBDs separated, similar to the conformation without bound nucleotide (Fig. 2A). We observe clear density for both nucleotide and the magnesium ion in the higher-resolution rod-form crystals with bound AMPPCP. In the lower resolution plate-form crystals with AMPPNP, the NBDs are more disordered and have higher B factors, and here the density is only clear for the base, ribose ring and two phosphates (Fig. S1 D–F). The open-inwards conformation is observed in two crystal forms with unrelated packing (Fig. S2) and in several crystals for each crystal form. There is clearly considerable flexibility in the structure, different crystals giving structures with variation in the extent of opening or closing of the open conformation (Fig. 2), (Fig. S3 and Note 1 in the SI Materials and Methods provide further information on the differences between open conformation ABCB10 structures). However, in no case did we observe a change to the open-outwards conformation seen in MsbA and Sav1866 or the half-closed NBDs seen the TM287/288 structure (Fig. S4). The flexibility we observe for the ABCB10 structures is in line with that observed for other ABC transporters in the open conformation, such as mP-gp (8) and MsbA (9). Molecular dynamics simulations on the two high-resolution nucleotide complex structures of ABCB10, embedded in a phospholipid bilayer, indicated that overall the structure is stable during a 100-ns simulation (Fig. S5 A–C), the only change in the structure occurring around TMH6, which has a tendency to unwind between Gly446 and Gly447 at the glycine-rich sequence G458LGAGG in all four simulations (Fig. S5D).

ABCB10 Nucleotide Binding Site.

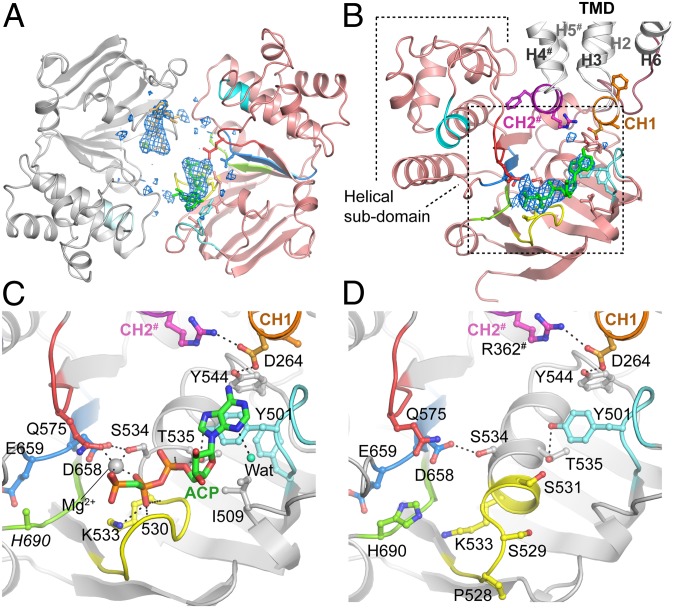

The nucleotide binding site in ABCB10 is only partially formed. In earlier ABC transporter nucleotide complexes in the open-outwards conformation, the NBDs are tightly packed together, with two nucleotides sandwiched at the interface, each interacting with both NBDs. However, in the ABCB10/AMPPCP structure the NBDs are separated to varying degrees (Fig. 2B) and each NBD interacts with a single nucleotide (Fig. 3A). ABC transporters have highly conserved nucleotide binding sites with a series of conserved motifs that interact with the nucleotide. The interactions between the nucleotide and the Walker A motif, A-loop tyrosine (Tyr501), and the Q-loop glutamine (Gln575) from one NBD are very similar to those in other ABC transporter structures (Fig. 3C), but the interaction with the ABC transporter consensus LSGGQ sequence (C-loop) from the other NBD is absent (Fig. 3A). This finding is reminiscent of the interactions observed for isolated monomeric NBDs with ADP (22), bacterial maltose importer with AMPPNP, and maltose (23) and one site of TM287/288 (21). In both nucleotide-bound and nucleotide-free forms of ABCB10 the Walker B motif glutamate (Glu659) adopts an unusual position, rotated 180° away from its expected orientation adjacent to the γ-phosphate. This conformation has been observed in isolated monomeric NBDs for ABCB6 (22).The His-loop histidine (His690) side-chain is partially disordered (not modeled in the rod-form A structure) and is further away from the γ-phosphate site than is usually observed in ABC transporters. We would expect these residues to move to the more commonly observed positions once the NBDs come together.

Fig. 3.

Interactions of nucleotides with the ABCB10 inward-facing conformation. (A) Schematic representation of NBDs of ABCB10 homodimer in the highest-resolution structure (rod form A) viewed looking from the TMD. AMPPCP (green/orange) are bound to each NBD but do not make inter-NBD interaction with the ABC transporter consensus sequence LSGGQ C-loop motif (cyan). (B) Individual NBD viewed looking from adjacent NBD. NBD (pink) with ABC Transporter nucleotide binding signature motifs colored as in C. TMD (gray) and coupling helices (CH1, orange; CH2#, purple) are highlighted. Omit Fo − Fc density for AMPPCP/Mg2+ (blue mesh) is shown contoured at 3 σ. Dotted box indicates zoomed region in C and D. Detailed view of nucleotide binding site in rod form A/AMPPCP complex (C) and nucleotide-free form (D). Oxygen atoms are colored red, nitrogen atoms blue, phosphate atoms orange and carbon atoms are colored according to the location of the atom: The AMPPCP carbon atoms are shown in green. The conserved NBD sequence motifs are colored Walker A (yellow), Walker B (light blue), A-loop (pale cyan), Gln-loop (red), His-loop (light green), coupling helix 1 (CH1, orange), and coupling helix 2 (CH2, magenta). The C-loop (cyan) is not visible as it is more than 16 Å away from the nucleotide binding site in this conformation. Residues/secondary structure elements marked with a pound symbol (#) denote regions contributed by homodimer partner. The side-chain of His690 is disordered and has not been modeled in rod form A.

In the absence of nucleotide the ABCB10 NBDs have a similar conformation, except in the region of the Walker A motif, residues 530–534 (Fig. 3D), which form an additional turn of the Walker A helix when there is no nucleotide bound. In the nucleotide complexes these residues form an extended loop structure that interacts with the β/γ-phosphates of bound nucleotide (Fig. 3C). This change in the local conformation of the nucleotide binding site is observed in some (22) but not all (8) nucleotide-free ABC transporter NBDs.

The classic ATP switch mechanism suggests that when two nucleotides bind to an ABC transporter dimer, it should convert to the open-outwards conformation (24), but if only one of the two nucleotide binding sites has nucleotide bound, then the structure would remain in the open-inwards conformation. If this hypothesis were true, then for our homodimeric structures with a single monomer in the asymmetric unit, we would expect to see an occupancy for the nucleotide of 50% or less. However, this result is not what we observe; refinement of the highest-resolution ABCB10 structure with fixed occupancies for the nucleotide and the magnesium ion of either 50%, 80%, or 100%, gave B factors for the nucleotide that were 30 Å2 below, similar to, or 30 Å2 above the average B factor for residues adjacent to the bound nucleotide. The occupancies of the nucleotide and Mg2+ are therefore in the 80–100% range, confirming that the majority of dimers would have two nucleotides bound. This structure, therefore, represents an open-inwards conformation with nucleotide bound to both nucleotide binding sites in the majority of molecules.

ABCB10 ATPase Activity and Inhibition by Nucleotide Analogs.

Because the open-inwards, nucleotide-bound conformations are unexpected, we investigated whether the ABCB10 ATPase activity and inhibition of this activity by nucleotide analogs differed from those of other ABC transporters. ABC transporters use the binding and hydrolysis of ATP to power the movement of substrates. Surprisingly, many ABC transporters exhibit a basal ATPase activity in vitro in the absence of transport substrate, which is stimulated between 2- and 10-fold when a transport substrate is added (25–27). ABCB10 showed basal ATPase activity, with apparent kinetic parameters similar to those of other ABC transporters (28, 29), when it was purified in DDM and either CHS or CDL, with or without reconstitution into liposomes (Table 1, Fig. S6 A and B, and SI Materials and Methods). It is clear that ABCB10 is active both in micelles and in proteoliposomes (Fig. S6 A and B). Small increases in Kcat/Km, of the order of fourfold on reconstitution are a common feature of many ABC transporters (29–31). The basal ATPase activity is inhibited by vanadate (Fig. S6 A and B). CDL does not stimulate the ATPase activity when added during reconstitution (Fig. S6C), suggesting that it is unlikely that CDL is transported by ABCB10. Mutation of the conserved putative catalytic Glu659 to glutamine in the nucleotide binding site of ABCB10 gave protein with no detectable activity (Fig. S6 B and E), as is observed for other ABC transporters (32, 33). The first construct used for crystallization had a PCR-derived mutation, which converted Arg691 to a histidine. The R691H mutation led to a substantial loss of activity and ATPase activity was restored when the Arg691 was reintroduced (Fig. S6D). The significance of this observation is discussed in Note 3 of SI Materials and Methods.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for the basal ATPase activity of ABCB10

| Lipid* | Recon† | n‡ | Km, app (ATP) mM | Vmax, app (nmol Pi min−1⋅mg−1) | Kcat/KmM-1⋅s-1 |

| CHS | − | 2 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 51 ± 1.1 | 2.2 |

| CHS | + | 10 | 0.3 ± 0.08 | 319 ± 27 | 8.2 |

| CDL | − | 2 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 106 ± 18 | 1.6 |

| CDL | + | 3 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 181 ± 9.8 | 6.7 |

Protein purified in DDM, with the addition of either CHS or CDL.

Protein in detergent (−) or reconstituted into proteoliposomes (+).

n = number of independent purifications.

The nucleotide analog complex structures presented here have AMPPNP or AMPPCP bound to the NBDs. We investigated the inhibition of the ABCB10 ATPase activity by these nucleotide analogs (Fig. S6F). AMPPCP and AMPPNP have IC50s of 2.3 ± 0.9 mM and 1.1 ± 1.1 mM, respectively, measured with 2 mM ATP. Using the Km,app of 0.2 mM measured for this protein sample, the apparent Ki for AMPPCP is of the order of 0.2 mM and for AMPPNP is 0.1 mM. The affinity of ABCB10 for these nucleotide analogs is therefore of the same order-of-magnitude as its affinity for ATP, suggesting that the interactions observed for the analogs would be similar to those for ATP.

Portal Between Two Transmembrane Helices Could Be a Route for Substrate Entry.

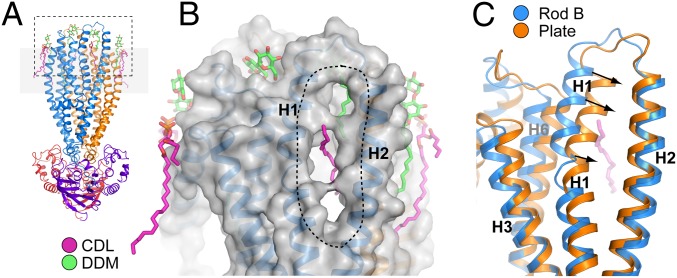

Lipid and detergent molecules are clearly visible interacting with the outer surface of the membrane-spanning region in all four ABCB10 structures (Fig. S7). Intriguingly in the rod-form crystals, TMH1 and TMH2 are separated, with elongated electron density between these helices, which we have attributed to an alkyl chain of a CDL molecule (Fig. 4 A and B). This lipid chain contacts both the internal cavity and the outer surface of the protein. The portal through which this CDL passes links the internal TMD cavity and the center of the lipid bilayer. In contrast, in the plate-form crystals these helices are packed tightly together, with no opening between them (Fig. 4C). In the rod-form crystals there are three residues which form crystal contacts to the loop joining TMH1 and TMH2, but there are no crystal contacts in the transmembrane region involving these helices, so it is unlikely that this change in conformation is induced by the crystal contacts observed in the rod-form crystals. This portal could provide a route of entry for a hydrophobic or amphipathic substrate from the membrane into the binding cavity.

Fig. 4.

ABCB10 has cardiolipin and detergent bound to the transmembrane helices and a portal between helices TMH1 and TMH2, which is open in the rod crystal form and closed in the plate-form crystals. (A) Overview of the ABCB10 structure showing the location of lipid (magenta) and detergent (green) binding sites. (B) Molecular surface representation of the TMD in rod form A crystals, with lipid and detergent molecules shown in magenta and green and the portal between TMH1 and TMH2 indicated with a dotted line. In the rod-form structures TMH1 and TMH2 are loosely packed revealing a 7 Å wide × 30 Å long portal connecting the central cavity of the TMDs with the membrane environment. The portal is occupied by a CDL alkyl chain (magenta). (C) In the plate form crystals TMH1 and TMH2 are packed closer together, with the portal closed. Structures are viewed in the same orientation as in A.

Conserved Residues in the TMD Suggest a Substrate Binding Site for ABCB10.

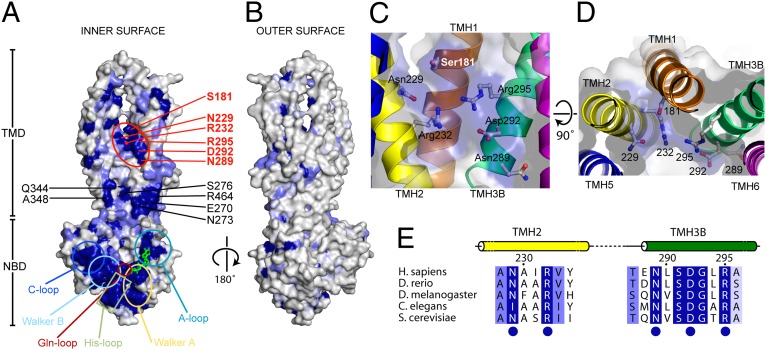

Alignment of the protein sequences of ABCB10 paralogues in 80 organisms highlights conserved patches that are exposed on the inner surface of the transporter (Fig. 5 and Fig. S8). The external surface of ABCB10 is not conserved, suggesting that ABCB10 has a role in substrate transport rather than forming a complex with another protein, which would require a conserved external surface. The NBD signature motifs are highly conserved, together with a patch formed by residues at the N-terminal end of TMH3 and the C-terminal end of TMH6. This latter cluster interacts closely with conserved residues in the domain-swapped TMH4 (Q344/A348) in the open-out conformation. A third cluster is located on the concave surface formed by the TMD. There are two conserved motifs, (N/I)xxR located in the center of TMH2 and NxxDGxR at the N terminus of TMH3B, which form a patch on the inner surface of the TMD cavity (Fig. 5 B–D). These residues form an ABCB10 signature sequence and, based on their location, we suggest that they could form part of the substrate binding site for an amphipathic substrate. If the outward-facing conformation of ABCB10 resembles that of Sav1866 (11), then the two helices TMH2 and TMH3 would be substantially further apart in the open-outward structure, changing the substrate binding site and therefore releasing the substrate into the intermembrane space.

Fig. 5.

Sequence conservation of residues in ABCB10. Conservation is mapped onto a molecular surface representation of the concave inner cavity (A) and convex outer surface (B) of ABCB10. The molecular surface shown is a composite representing one-half “leaflet” of the transporter dimer, comprising residues from TMH1–TMH3 and TMH6-NBD in one monomer and TMH4/5 from the second monomer (residues 311–424). Residues are colored according to sequence conservation, invariant (dark blue), highly conserved (slate; 2–4 related amino acids), and moderately conserved (pale blue; 3–8 related amino acids). Sequence conservation was calculated based on an alignment of eighty ABCB10 homologs (human to yeast) using the CONSURF server (38). The conserved patch in the TMD between TMH2/TMH3B adjacent to the portal region (indicated in red) defines a unique ABCB10 signature sequence. (C and D) Perpendicular views of residues defined by ABCB10 signature sequence (Asn229, Arg232, Asn289, Asp295, and Arg295). All of the side-chains project toward the lumen of the transporter. Side-chains are shown along with a semitransparent molecular surface. (E) Conserved signature sequence defined by residues located in central portion of TMH2 and at the N-terminal end of TMH3B.

Discussion

ABCB10 Structure and ABC Transporter Mechanism.

Our four structures of ABCB10 in complex with nucleotide analogs and without bound nucleotide give snapshots of ABCB10 before substrate binding and in a conformation where ATP has bound, and the protein is awaiting the transport substrate. ABCB10 remains an orphan transporter, one for which we do not yet know the transport substrates. Our structures do, however, suggest a potential entry route for an amphipathic substrate and a potential binding site for transport substrates.

The generally accepted ATP switch model for ABC transporter function (24) proposes that binding of nucleotide to the protein/substrate complex is the trigger for conversion from the open-inwards to the open-outward conformation, thus driving transport of the substrate across the membrane. A similar mechanism, but with the nucleotide binding before the substrate, was suggested for the transporter associated with antigen processing (34) and alternative binding sequences have also been proposed for P-gp (35). Alternating catalytic site mechanisms involving asymmetric binding and hydrolysis have also been put forward (reviewed in ref. 36).

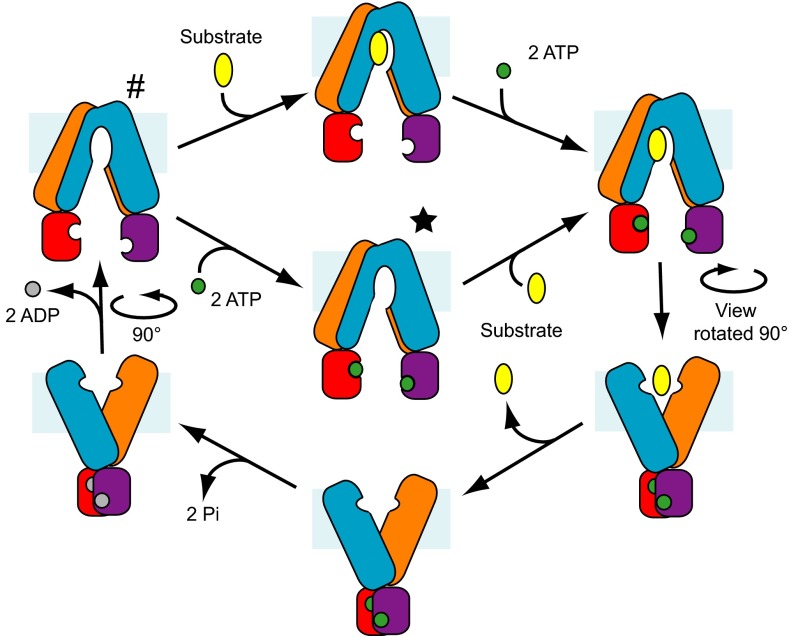

Our structures suggest an adaptation of the accepted ATP switch mechanism in which either transport substrate or nucleotide could bind first (Fig. 6). These ABCB10 nucleotide analog complex structures show that nucleotides can bind in the absence of a transport substrate, an observation that is in line with the fact that many ABC transporters, including ABCB10, have a basal ATPase activity, performing the ATPase reaction in the absence of transport substrate. ABC transporter NBDs must therefore be capable of binding ATP and coming together in a productive complex for ATP hydrolysis, even when there is no transport substrate present.

Fig. 6.

Overview of the steps proposed for the transport cycle of ABCB10 and other ABC transporters of the exporter family. The TMDs are colored blue and orange, with their associated NBDs colored purple and red. ATP is shown in green, ADP in gray and the transport substrate in yellow. An asterisk (*) and pound symbol (#) indicate the conformations observed for nucleotide-bound and nucleotide-free ABCB10, respectively.

Although our structures indicate that ABC transporters can bind nucleotide in the absence of transport substrate, it has also been shown that many ABC transporters bind transport substrate and inhibitors in the absence of nucleotide, as has been observed for P-gp (8) and transporter associated with antigen processing (37). We therefore propose that ABC transporters could bind either nucleotides or transport substrate first, each binding initially to one face of open-inwards conformation. Once the nucleotides or transport substrate binds to one face of the complex, the NBDs or TMDs could come together in a productive orientation, forming complete binding sites with interactions for the substrate molecules with both halves of the TMDs and for the ATPs with both NBDs (Fig. 6). Because the rate of ATP turnover is often higher in the presence of the transport substrate, occupation of the transport substrate binding site must promote formation of the ATP hydrolysis-competent closed NBD conformation. The NBDs coming together in the presence of bound transport substrate would then trigger reorganization of the TMDs into the open-outwards conformation, disrupting the transport substrate binding site and forcing the substrate to dissociate on the other side of the membrane. One or both of the nucleotides would then be hydrolyzed and dissociate, allowing the structure to return to the inward-facing conformation. Although our structures are symmetrical, having a monomer in the asymmetric unit, this does not preclude the possibility that certain steps in the mechanism involve asymmetry in the nucleotide binding site, with hydrolysis occurring in only one site, as has been shown for other ABC transporters (36). These ABCB10 structures therefore provide fresh insights into ABC transporter function, in particular providing a unique example of exporter fold ABC transporters in complex with nucleotide analogs, in an open-inwards conformation. The findings suggest that nucleotide binding can occur before transport substrate binding and that it is therefore likely that the order in which these molecules bind is not fixed. Binding of the transport substrate does, however, promote the formation of the conformation in which the NBDs come together, converting the TMDs to the open-outwards conformation, thus leading to a stimulation of the ATPase reaction and transport of the substrate.

The key role of ABCB10 in erythropoiesis and relief of oxidative stress suggests that this transporter could be an interesting candidate to explain a frequently observed adverse effect of drugs and early clinical inhibitors in red blood cell formation, resulting in anemia or decreased recovery of cardiac function after ischemia/reperfusion. The future identification of ABCB10 substrates and binding studies of inhibitors and drugs that have been associated with these side effects will facilitate identification of the function of ABCB10. Such studies would also give insight into the role of ABCB10 in conditions causing increased mitochondrial oxidative stress, such as aging, anemia, cardiac ischemia/reperfusion, or neurodegenerative diseases and its potential as a target for pharmaceutical intervention.

Materials and Methods

The complete methods are presented in SI Materials and Methods. For structure and function studies we expressed ABCB10 in insect cells using baculovirus vectors. We expressed ABCB10 with both N- and C-terminal His-tags with the mitochondrial targeting presequence (mTP) removed, either by deletion of the N-terminal 151 residues or removal of residues 6–126. We extracted and purified ABCB10 in the detergent DDM with the addition of either CHS or CDL by cobalt affinity and size-exclusion chromatography. For functional studies we reconstituted ABCB10 into liposomes containing the synthetic lipids 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-ethanolamine (POPE) without the addition of CHS or CDL.

We obtained plate-form crystals with both ABCB10 constructs, purified in DDM and CHS, without addition of nucleotide and with the nucleotide analogs AMPPNP or AMPPCP. All nucleotide analog stocks were prepared with equimolar magnesium chloride. Crystals were grown at 20 °C using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method. Diffraction data were collected on beamline I24 at Diamond Light Source. Crystals grown with AMPPNP diffracted anisotropically beyond 3.3 Å and were used to solve the structure with phases from a single mercury derivative (Fig. S1 and Table S1). The chain trace was confirmed with data from selenomethionine-labeled ABCB10 crystals. Rod-shaped crystals were obtained without nucleotide and with AMPPCP from protein purified in the presence of CDL. The rod-form crystals diffracted to at least 2.9 Å and were phased by molecular replacement using an initial model derived from the plate form. ATPase activity assays and molecular dynamics simulations methods are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Tampé and Peter Henderson for helpful discussions and Stefan Knapp for critical reading of the manuscript; Richard Callaghan for help with establishing the ATPase assay; Tobias Krojer, Melanie Vollmar, and Joao Muniz for assistance with crystal screening; the staff at Diamond Light Source and, in particular, the microfocus beamline I24 for assistance with crystal screening and data collection. The Structural Genomics Consortium is a registered charity (no. 1097737) that receives funds from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, Genome Canada, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly Canada, the Novartis Research Foundation, Pfizer, Takeda, AbbVie, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, and the Wellcome Trust (092809/Z/10/Z).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 4AYT (rod form A), 4AYX (rod form B), 4AYW (plate form), and 3ZDQ (nucleotide-free rod form)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1217042110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Locher KP. Review. Structure and mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporters. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1514):239–245. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zolnerciks JK, Andress EJ, Nicolaou M, Linton KJ. Structure of ABC transporters. Essays Biochem. 2011;50(1):43–61. doi: 10.1042/bse0500043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aittoniemi J, et al. Review. SUR1: A unique ATP-binding cassette protein that functions as an ion channel regulator. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1514):257–267. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheppard DN, Welsh MJ. Structure and function of the CFTR chloride channel. Physiol Rev. 1999;79(1) Suppl:S23–S45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottesman MM. Mechanisms of cancer drug resistance. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:615–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean M, Rzhetsky A, Allikmets R. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Genome Res. 2001;11(7):1156–1166. doi: 10.1101/gr.184901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg MF, et al. Repacking of the transmembrane domains of P-glycoprotein during the transport ATPase cycle. EMBO J. 2001;20(20):5615–5625. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aller SG, et al. Structure of P-glycoprotein reveals a molecular basis for poly-specific drug binding. Science. 2009;323(5922):1718–1722. doi: 10.1126/science.1168750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward A, Reyes CL, Yu J, Roth CB, Chang G. Flexibility in the ABC transporter MsbA: Alternating access with a twist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(48):19005–19010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709388104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin MS, Oldham ML, Zhang Q, Chen J. Crystal structure of the multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein from Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2012;490(7421):566–569. doi: 10.1038/nature11448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson RJ, Locher KP. Structure of a bacterial multidrug ABC transporter. Nature. 2006;443(7108):180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature05155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirihai OS, Gregory T, Yu C, Orkin SH, Weiss MJ. ABC-me: A novel mitochondrial transporter induced by GATA-1 during erythroid differentiation. EMBO J. 2000;19(11):2492–2502. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang F, et al. M-ABC2, a new human mitochondrial ATP-binding cassette membrane protein. FEBS Lett. 2000;478(1-2):89–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01823-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyde BB, et al. The mitochondrial transporter ABC-me (ABCB10), a downstream target of GATA-1, is essential for erythropoiesis in vivo. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19(7):1117–1126. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liesa M, et al. Mitochondrial transporter ATP binding cassette mitochondrial erythroid is a novel gene required for cardiac recovery after ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 2011;124(7):806–813. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.003418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chloupková M, LeBard LS, Koeller DM. MDL1 is a high copy suppressor of ATM1: Evidence for a role in resistance to oxidative stress. J Mol Biol. 2003;331(1):155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00666-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen W, et al. Abcb10 physically interacts with mitoferrin-1 (Slc25a37) to enhance its stability and function in the erythroid mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(38):16263–16268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904519106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W, Dailey HA, Paw BH. Ferrochelatase forms an oligomeric complex with mitoferrin-1 and Abcb10 for erythroid heme biosynthesis. Blood. 2010;116(4):628–630. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zutz A, Gompf S, Schägger H, Tampé R. Mitochondrial ABC proteins in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787(6):681–690. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young L, Leonhard K, Tatsuta T, Trowsdale J, Langer T. Role of the ABC transporter Mdl1 in peptide export from mitochondria. Science. 2001;291(5511):2135–2138. doi: 10.1126/science.1056957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hohl M, Briand C, Grütter MG, Seeger MA. Crystal structure of a heterodimeric ABC transporter in its inward-facing conformation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(4):395–402. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haffke M, Menzel A, Carius Y, Jahn D, Heinz DW. Structures of the nucleotide-binding domain of the human ABCB6 transporter and its complexes with nucleotides. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 9):979–987. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910028593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oldham ML, Chen J. Crystal structure of the maltose transporter in a pretranslocation intermediate state. Science. 2011;332(6034):1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1200767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins CF, Linton KJ. The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(10):918–926. doi: 10.1038/nsmb836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauna ZE, Nandigama K, Ambudkar SV. Multidrug resistance protein 4 (ABCC4)-mediated ATP hydrolysis: Effect of transport substrates and characterization of the post-hydrolysis transition state. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):48855–48864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhnke G, Neumann K, Mühlenhoff U, Lill R. Stimulation of the ATPase activity of the yeast mitochondrial ABC transporter Atm1p by thiol compounds. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23(2):173–184. doi: 10.1080/09687860500473630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herget M, et al. Purification and reconstitution of the antigen transport complex TAP: A prerequisite for determination of peptide stoichiometry and ATP hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(49):33740–33749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zehnpfennig B, Urbatsch IL, Galla HJ. Functional reconstitution of human ABCC3 into proteoliposomes reveals a transport mechanism with positive cooperativity. Biochemistry. 2009;48(20):4423–4430. doi: 10.1021/bi9001908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schölz C, et al. Specific lipids modulate the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) J Biol Chem. 2011;286(15):13346–13356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Modok S, Heyward C, Callaghan R. P-glycoprotein retains function when reconstituted into a sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich environment. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(10):1910–1918. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400220-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi K, Kimura Y, Kioka N, Matsuo M, Ueda K. Purification and ATPase activity of human ABCA1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(16):10760–10768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tombline G, et al. Properties of P-glycoprotein with mutations in the “catalytic carboxylate” glutamate residues. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(45):46518–46526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaitseva J, Jenewein S, Jumpertz T, Holland IB, Schmitt L. H662 is the linchpin of ATP hydrolysis in the nucleotide-binding domain of the ABC transporter HlyB. EMBO J. 2005;24(11):1901–1910. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abele R, Tampé R. The ABCs of immunology: Structure and function of TAP, the transporter associated with antigen processing. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:216–224. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00002.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callaghan R, Ford RC, Kerr ID. The translocation mechanism of P-glycoprotein. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(4):1056–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Shawi MK. Catalytic and transport cycles of ABC exporters. Essays Biochem. 2011;50(1):63–83. doi: 10.1042/bse0500063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uebel S, et al. Requirements for peptide binding to the human transporter associated with antigen processing revealed by peptide scans and complex peptide libraries. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(31):18512–18516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashkenazy H, Erez E, Martz E, Pupko T, Ben-Tal N. ConSurf 2010: Calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Web Server issue):W529–W533. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.