Abstract

The Forkhead boxO (FOXO) transcription factors regulate multiple cellular functions. FOXO1 and FOXO3 are highly expressed in granulosa cells of ovarian follicles. Selective depletion of the Foxo1 and Foxo3 genes in granulosa cells of mice reveals a novel ovarian-pituitary endocrine feedback loop characterized by: 1) undetectable levels of serum FSH but not LH, 2) reduced expression of the pituitary Fshb gene and its transcriptional regulators, and 3) ovarian production of a factor(s) that suppresses pituitary cell Fshb expression. Equally notable, and independent of FSH, microarray analyses and quantitative PCR document that depletion of Foxo1/3 alters the expression of specific genes associated with follicle growth vs. apoptosis by disrupting critical and selective regulatory interactions of FOXO1/3 with the activin or bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) pathways, respectively. As a consequence, both granulosa cell proliferation and apoptosis were decreased. These data provide the first evidence that FOXO1/3 divergently regulate follicle growth or death by interacting with the activin or BMP pathways in granulosa cells and by modulating pituitary FSH production.

Members of the Forkhead boxO (FOXO) transcription factor family are expressed in specific cell types and control many diverse cellular processes (cell proliferation, apoptosis, metabolism, and cell survival) that are conserved from Caenorhabditis elegans to man (1–6). Moreover, FOXOs not only regulate genes in the cells in which they are expressed but also control the expression of genes whose products act as endocrine/metabolic regulators of tissues upon which they depend (7, 8). Although FOXOs have been most intensively studied as targets of the IGF-I/insulin and phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)/serine-threonine protein kinase B pathways, other signaling cascades can activate PI3K. Moreover, FOXOs interact with multiple signaling molecules to coordinately regulate cell-specific gene expression profiles and functions (9). Alternate regulators of FOXO expression and function include the pituitary hormones (10, 11) and members of the TGF/activin/bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family (12). The emerging importance of FOXOs is particularly evident in the regulation of gonadal functions in C. elegans and mice (2, 6, 13, 14).

Ovarian follicular development is a highly orchestrated process, in which multiple signaling pathways play critical roles at specific stages of growth. Less than 1% of all follicles that are present in the mammalian ovary at birth ever ovulate and luteinize to become progesterone-secreting cells capable of supporting pregnancy. Greater than 99% succumb to atresia and the complete loss of granulosa cells by apoptotic programmed cell death (15). Thus, the balance between follicle growth and ovulation vs. atresia is precisely regulated by growth-promoting vs. growth-restricting factors. Understanding factors that regulate this balance is of utmost importance for controlling the pool of growing follicles and permitting healthy oocytes to be ovulated for fertilization.

Follicle growth is regulated by the pituitary gonadotropins, FSH and LH (16), as well as oocyte- and ovarian-derived growth regulatory factors and steroids (17–20). Granulosa cell proliferation is essential for follicle growth and is dependent, in part, not only on FSH but also on activin (17, 21–24). Growth of preovulatory follicles is terminated by LH-induced luteinization. Members of the FOXO transcription factor family are highly expressed in specific ovarian cells (10, 11, 25), and, based on their ability to regulate diverse cellular processes (5, 9, 26–28), they are presumed to be key regulators of follicular growth and/or apoptosis. FOXO1 is highly expressed in granulosa cells of growing follicles where levels of activin are high (12). Conversely, FOXO1 is also expressed in follicles undergoing atresia where BMP2 is preferentially expressed (11, 29). Studies in cultured granulosa cells indicate further that FOXO1 can regulate genes associated with proliferation, metabolic homeostasis, and apoptosis (4, 22). FOXO1 knockout mice were embryonic lethal (27, 30), which precludes the study of its functions in ovary in vivo. Foxo3 is expressed in oocytes where it controls primordial follicle quiescence. Disruption of the Foxo3 gene leads to increased follicle activation (2, 3). Foxo4 is not highly expressed in any ovarian compartment (10, 14), and Foxo4 null mice are fertile (1, 13). Corpora lutea of the Pten conditional knockout mice have elevated expression of Foxo3 and exhibit a prolonged lifespan (31). However, the specific functions of Foxo1 and Foxo3 in ovarian somatic cells in vivo have not been defined.

Therefore, the goals of these studies were to determine the physiological consequences of disrupting Foxo1 and Foxo3 in granulosa cells and to determine the interactions of Foxo1 with activin and BMP2 signaling cascades. Our studies document that depletion of Foxo1 and Foxo3 in granulosa cells leads to an infertile phenotype characterized by undetectable levels of serum FSH and ovarian production of an unknown factor(s) that, other than or in addition to inhibin, suppresses pituitary cell Fshb expression, thus revealing a novel ovarian-pituitary endocrine feedback loop. Furthermore, independent of regulating pituitary FSH, our results provide the first evidence that FOXO1/3 divergently regulate follicle growth or death by interacting with the activin and BMP pathways, respectively, in granulosa cells.

Materials and Methods

Generation of mice

To disrupt the Foxo genes selectively in granulosa cells, we initially mated the Foxo1f/f;Foxo3f/f;Foxo4f/f female mice (1) to Amhr2-Cre+ males (32). The various genotypes derived from this and subsequent crosses are described in detail in Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org. Because no obvious ovarian or reproductive phenotypes were observed consistently in these mice and because Amhr2-Cre is known to have low recombinase efficiency, we employed a strategy used by many (33–35) to generate germ-line depletion of Foxo1 and Foxo3 alleles. Specifically Gdf9-Cre+ males (36) were crossed with Foxo1f/f and Foxo3f/f mice to generate germ-line depletion of the Foxo1 and Foxo3 alleles and ultimately to obtain the Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−Amhr2-Cre genotype (Supplemental Fig. 1 and Fig. 1A). Because Foxo4 null mice are fertile, we selectively removed the Foxo4fl/fl mice from the breeding schemes. As discussed in results and as described in Supplemental Fig. 1, we also generated mice in which Foxo1 and Foxo3 were depleted using the Cyp19-Cre mice (31) creating the Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Cyp19-Cre genotype. These mice allowed us to verify the granulosa cell specificity of the conditional knockout (KO) mouse phenotype and to document that both the Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Amhr2-Cre and Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Cyp19-Cre mice are infertile and exhibit a similar and unique reproductive phenotype. All experimental and control animals were littermates or age matched (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1).

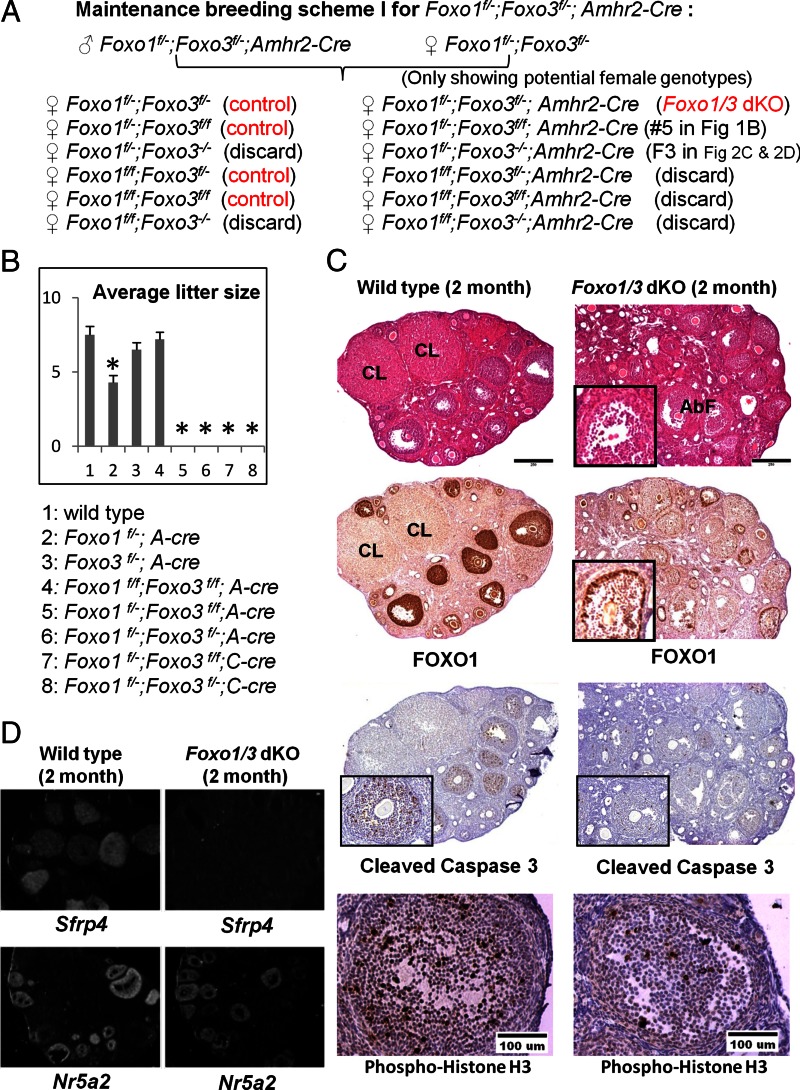

Fig. 1.

Selective depletion of Foxo1 and Foxo3 in granulosa cells alters follicle development and disrupts fertility. A, The breeding scheme for generating Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;A-Cre mice. Only the expected female progeny genotypes are shown. The littermates with no Cre were used as controls in all the experiments. More detailed breeding schemes are presented in Supplemental Fig. 1. The same breeding schemes were used to generate the Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Cyp19-Cre mice. B, Fertility studies. In extended 6-month breeding experiments, Foxo1f/−;A-Cre mice had reduced fertility, whereas Foxo3f/−;A-Cre and Foxo1f/f;Foxo3f/f;A-Cre mice were comparable with wild type. Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/f;A-Cre and Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;A-Cre mice were totally infertile. The Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/f;C-Cre and Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;C-Cre mice are also infertile. A-Cre refers to Amhr2-Cre and C-Cre refers to Cyp19-Cre. There were four to seven mice per group. C, Histological analyses. Hematoxylin and eosin sections of ovaries from 2-month-old control mice have corpora lutea (CL); ovaries of 2-month-old Foxo1/3 dKO mutant mice lack corpora lutea and exhibit abnormal follicle morphology (AbF). Reduced FOXO1 protein was observed in most granulosa cells except for the outermost mural granulosa cells in some large follicles (inset). Staining of cleaved caspase 3 and phospho-histone H3 was reduced in follicles of the mutant mice compared with controls; only a few cells in specific follicles showed positive staining were seen in mutant granulosa cells (as illustrated in the inset). D, Gene expression data. In situ hybridization indicates that the Foxo1/3 mutant ovaries express Nr5a2, a gene marker highly expressed in granulosa cells of growing and ovulating follicles, but do not express Sfrp4, a marker of corpora lutea. Asterisk indicates statistically significantly different (P < 0.05).

All the genotyping protocols follow those published in the original papers (1, 31, 32, 36). Animals were housed under a 16-h light, 8-h dark cycle in the Center for Comparative Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and provided food and water ad libitum. Animals were treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Baylor College of Medicine.

Ovarian and pituitary histology

Ovaries and pituitaries were collected in 4% paraformaldehyde, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin by routine procedures (31). In situ hybridization analyses were done as previously using specific probes for Sfrp4 and Nr5a2, which were constructed using the pCR-TOPO4 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), as described previously (10, 37). Immuno-histochemical analyses were done with the antibodies specific for FOXO1 (no. 2880), FOXO3 (no. 9467), Mapk10 (mitogen-activated protein kinase 10), also known as c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3 (JNK3) (no. 2305), cleaved caspase 3 (no. 9661) (1:100; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and phospho-histone H3 (no. ab5176; 1:250; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) as described previously (38) and as presented in the figures. Digital images were captured using a Zeiss AxioPlan2 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with ×5, ×10, or ×20 objectives in the Integrated Microscopy Core at Baylor College of Medicine.

Granulosa cell isolation and culture

Granulosa cells were isolated by needle puncture from ovaries at time points specified in the text. Primary granulosa cell cultures and the infection of cells with adenoviral vectors expressing green fluorescent protein (control) or constitutively active FOXO1 (FOXO1A3; FKHR:AAA) were carried out as described previously (4). Activin (40 ng/ml) and BMP2 (100 ng/ml) were added as indicated.

Ovariectomy

Both ovaries were surgically removed from female mice at approximately 2 months of age. After 2 wk, blood was collected by terminal cardiac puncture under isoflurane anesthesia (39). Pituitaries were isolated, and RNA was extracted for quantitative measurement [quantitative PCR (qPCR)] of specific mRNAs.

Pituitary (GnRH) stimulation protocol

Female mice approximately 2 months of age were injected sc with Leuprolide acetate salt (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 100 μl of saline. Blood was collected 15 min later by terminal cardiac puncture under isoflurane anesthesia (39).

Hormone assays

Serum was prepared from collected blood samples using BD Microtainer* Plastic Capillary Blood Collectors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). LH, FSH, estradiol, testosterone, progesterone, inhibin A, and inhibin B levels were measured using specific assays in the Ligand Assay Core Laboratory at the University of Virginia, Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research (SCCPIR).

RNA isolation, microarray analyses, and qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from granulosa cells and pituitaries of control mice at d 25 and from Foxo1/3 double conditional knockout (dKO) mice at d 25 and 2 months of age using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN Sciences, Germantown, MD). Reverse transcription was done using the Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). The qPCR was performed using the Rotor-Gene 6000 thermocycler (QIAGEN Sciences). The primers were designed using software Primer3 (Supplemental Table 1) (40). Relative levels of mRNAs were calculated using Rotor-Gene 6.0 software and normalized to the levels of endogenous ribosomal protein L19 mRNA in the same samples.

For the microarray analyses, ovarian RNA quality was assessed, and then riboprobes were generated from control and mutant RNA and hybridized to Mouse 430.2 microarray chips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) in the Microarray Core Facility of the Baylor College of Medicine. Microarray data were analyzed as previously reported using the robust multiarray averaging function (41) from the Affy package (version 1.5.8) through the BioConductor software (42). The microarray data have been deposited to GEO with the accession number GSE35593. The average fold differences in RNA were imported into Ingenuity Systems and analyzed using the tools provided in the Ingenuity program.

Western blot analyses

Granulosa cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer [20 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate] containing complete protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Western blottings were performed using antibodies for FOXO1 (no. 2880), phosphatase and tensin homolog (no. 9559), pan-phopho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (no. 9251), MAPK10 (JNK3) (no. 2305), Bcl-2-like protein 11 (BCL2L11) (no. 2933) (1:1000; Cell Signaling), and β-actin (no. AAN01; 1:2000; Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO).

Statistics

All the data were analyzed by unpaired two-tail Student's t test unless specified in the figure legend. A P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Data shown were mean ± sem.

Results

Selective depletion of Foxo1 and Foxo3 in granulosa cells alters follicle development and disrupts fertility

To determine the roles of the FOXO factors in granulosa cells in vivo, we have used mice harboring floxed alleles of the Foxo1 and Foxo3 genes (1). This is essential, because the Foxo1 null mice are embryonic lethal (27, 30), and the Foxo3 null mice undergo premature ovarian failure as a consequence of FOXO3 functions within the oocyte as a suppressor of primordial follicle activation (2, 27). In the original mating scheme, Foxo1fl/fl;Foxo3fl/fl;Foxo4fl/fl female mice (1) were crossed with to Amhr2-Cre+ males (32) to generate Foxo1fl/fl;Amhr2-Cre, Foxo3fl/fl;Amhr2-C, and Foxo1fl/fl;Foxo3fl/fl;Amhr2-Cre double knockout mice as detailed in Materials and Methods (Supplemental Fig. 1 and Fig. 1A). Because Foxo4 null mice are fertile (27), the Foxo4fl/fl mice were eliminated during the mating schemes. The resulting mice of all genotypes, including the Foxo1fl/fl;Foxo3fl/fl;Amhr2-Cre female mice, were viable, with no obvious physical or reproductive defects. Therefore, to enhance depletion of the Foxo1 and Foxo3 alleles, we generated germ-line depletion of these alleles by mating Foxo1fl/fl and Foxo3fl/fl females to Gdf9-Cre+ males (36). After selective breeding, we ultimately obtained the Foxo1f/−;Amhr2-cre, Foxo3f/−;Amhr2-Cre, and Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Amhr2-Cre (Foxo1/3 dKO) mice (Fig. 1A and Supplemental Fig. 1). Using similar strategies, we also generated mice in which Foxo1 and Foxo3 were depleted in the Cyp19-Cre mouse background, ultimately creating the Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Cyp19-Cre genotype to verify the granulosa cell specificity of the phenotypes (Supplemental Fig. 1 and Fig. 1A).

Mice in which either Foxo1 (Foxo1f/−;Amhr2-Cre) or Foxo3 (Foxo3f/−;Amhr2-Cre) alone was disrupted exhibited normal ovarian follicle morphology indistinguishable from wild-type mice (data not shown) but were subfertile or fertile, respectively (Fig. 1B). However, the double mutant mice, Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Amhr2-Cre (Foxo1/3;A-Cre or Foxo1/3 dKO if not specified) and Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Cyp19-Cre (Foxo1/3;C-Cre) mice were infertile (Fig. 1, A and B). In extended breeding experiments in which the Foxo1/3;A-Cre and Foxo1/3;C-Cre female mice were housed with proven fertile wild-type male breeders for 6 months, no pups were born.

Histological analyses of the ovaries from control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice at 2 months of age showed marked differences. The ovaries of control mice contained corpora lutea and follicles at many stages of growth, including large antral follicles. In sharp contrast, the mutant ovaries lacked corpora lutea, and follicles exhibited an abnormal appearance in which granulosa cells were dislodged to the center of the antrum (Fig. 1, C and inset). Ovaries of the control mice exhibited intense immunostaining of FOXO1 in granulosa cells and oocytes of follicles from the secondary to large antral stages. The disruption of the Foxo1 gene led to the depletion of FOXO1 protein in most ovarian granulosa cells with the exception of the outermost layer of the mural granulosa cells in some large follicles (Fig. 1, C and inset). FOXO1 was not depleted in oocytes of the mutant mice. Due to the low expression of FOXO3 in granulosa cells and the variable quality of FOXO3 antibodies, we could not conclusively show reduced levels of FOXO3 in ovaries of the mutant mice. However, because the double mutant mice exhibit a far more extreme phenotype than the single mutants, we conclude that FOXO3 exerts critical functions in granulosa cells of developing and differentiating follicles. The apoptotic index (shown by immunostaining for cleaved caspase 3) and the proliferation index (shown by immunostaining for phospho-histone H3) were both reduced in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice compared with controls (Fig. 1C). In situ hybridization using a probe specific to Sfrp4 (Fig. 1D), a gene highly up-regulated during the luteinization process, showed positive signals only in the ovaries of wild-type mice where corpora lutea are present (Fig. 1D). On the other hand, expression of Nr5a2, a gene highly expressed in granulosa cells of growing and ovulating follicles, was not markedly altered in the Foxo1/3 mutant mice compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 1D). We conclude that FOXO1 and FOXO3 together play essential roles in female fertility and granulosa cell/follicle maturation, including luteinization.

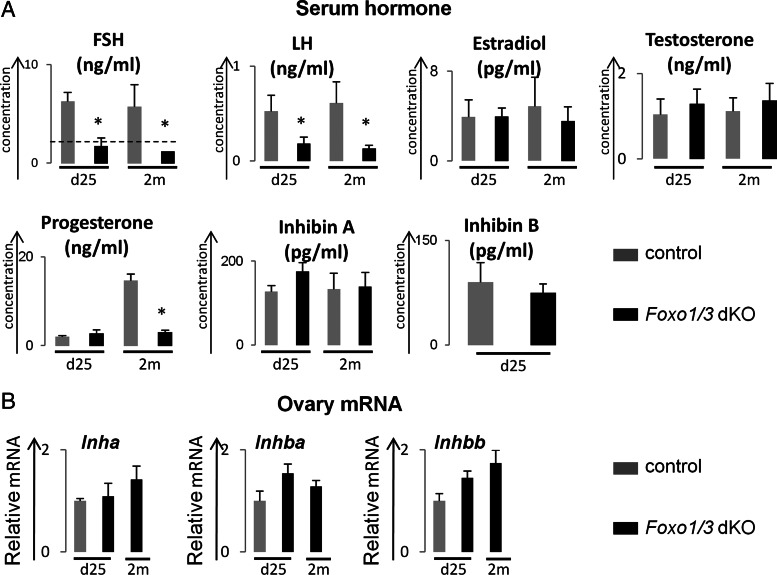

Factor(s) produced by Foxo1/3 mutant ovaries suppress pituitary expression of Fshb and reduce serum FSH

Follicular development from the small antral to preovulatory stage depends on the actions and deliberate regulation of the gonadotropic hormones, FSH and LH (16). Because follicular growth was arrested at the preantral or early antral stages and because corpora lutea were absent in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice, serum levels of the gonadotropins (FSH and LH) and steroids (estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone) were measured (Fig. 2A). Serum FSH in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice dropped to undetectable levels at d 25 and 2 months of age, whereas serum LH levels in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice were decreased less when compared with control mice (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. 2). Basal levels of serum estradiol and testosterone did not differ between the controls and mutant mice at either age (Fig. 2A). However, progesterone was higher in the control mice at 2 months where corpora lutea were present and low in the mutant mice where corpora lutea were absent (Figs. 2A and 1C). Because basal levels of FSH dropped dramatically in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice, we measured serum levels of inhibin, a known negative regulator of pituitary FSH biosynthesis (43). Surprisingly, serum levels of inhibin A and inhibin B in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice were not significantly different from controls at d 25 or 2 months of age (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. 2). Moreover, when we measured ovarian expression of Inha, Inhba, and Inhbb mRNAs, no significant difference was observed between controls and mutants (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Hormone levels in serum of control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice. A, Serum levels of hormones. Serum FSH levels were below the level of detection (dashed line) in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice at both d 25 and 2 months (2m) of age. Serum LH levels declined less and remained detectable. Serum levels of estradiol and testosterone in Foxo1/3 mice at d 25 and 2 months of age were comparable with that of control mice at the same age. Progesterone levels were comparable at d 25 and higher in control mice at 2 months due to the presence of corpora lutea. There were also no significant differences in serum levels of inhibin A or inhibin B. There were more than five mice per group. B, Ovarian expression of Inha, Inhba, and Inhbb mRNAs. Granulosa cells were isolated from control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice at d 25 and 2 months of age, and the mRNA levels for Inha, Inhba, and Inhbb were measured by qPCR using specific primers and normalized to L19. No differences were observed in the expression of Inha, Inhba, and Inhbb mRNAs in the control and mutant granulosa cells. Control mice at 2 months of age have corpora lutea and therefore were not used for comparative purposes. All data are presented as mean ± sem (n ≥ 3). Asterisk indicates statistically significantly different (P < 0.05).

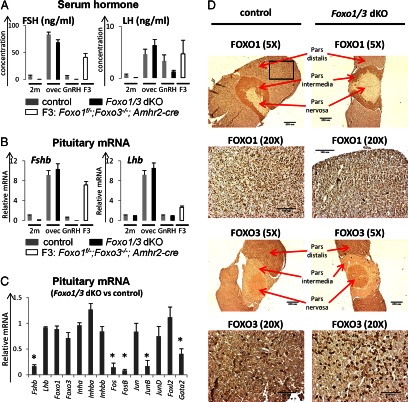

These results suggested that there might be ovarian-derived factors, other than or in addition to the classical steroids and inhibin, coming from the Foxo1/3 dKO ovaries that selectively control pituitary FSH release and/or synthesis compared with LH. To address this issue, we analyzed serum levels of FSH and LH (Fig. 3A) and pituitary expression of genes encoding Fshb and Lhb (Fig. 3B) under different experimental conditions that are known to dramatically alter serum levels of FSH or LH: 1) no treatment, 2) ovariectomy, 3) GnRH treatment, and 4) germ-line depletion of Foxo3 in the Foxo1 mutant strain (Foxo1f/−;Foxo3−/−;Amhr2-Cre mice; designated F3). Serum levels of FSH drop dramatically in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice compared with controls, whereas serum LH levels were less affected (Figs. 2A and 3A). When control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice were ovariectomized at 2 months of age, FSH and LH levels in the mutant mice increased dramatically to levels observed in the castrate control female mice, indicating that the ovary was likely the source of inhibitory factors. An acute in vivo pulse of GnRH stimulated a significant increase in serum LH in the control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice indicating that 1) GnRH selectively stimulated LH but not FSH release from the pituitary and 2) LH release was not impaired in the mutant mice. However, serum FSH remained below the detection limit in the mutant mice. Germ-line depletion of Foxo3 in the Foxo1 mutant strain (Foxo1f/−;Foxo3−/−;Amhr2-Cre mice; F3) led to ovaries completely devoid of all the follicles by 5 months of age (data not shown) and castrate levels of serum FSH and LH as was observed previously in the Foxo3 null mice (2).

Fig. 3.

Serum FSH and LH and pituitary expression of Fshb and Lhb under different experimental paradigms. A, Serum levels of FSH and LH. Serum levels of FSH, but not LH, are below the levels of detection in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice at 2 months of age (2m) compared with controls. Serum levels of FSH and LH increased markedly 2 wk after ovariectomy, LH but not FSH increased in response to an acute injection of GnRH, and FSH and LH increased in the 5-month-old FOXO3 germ line-depleted mice (Foxo1f/−;Foxo3−/−;A-Cre, abbreviated as F3). B, Pituitary expression of Fshb and Lhb mRNA. Fshb, but not Lhb, mRNA was reduced in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice at 2 months of age compared with controls. Pituitary expression of Fshb and Lhb mRNA was dramatically increased after ovariectomy in both control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice. Fshb and Lhb mRNAs were also increased in the 5-month-old FOXO3 germ line-depleted mice (Foxo1f/−;Foxo3−/−;A-Cre, abbreviated as F3). GnRH treatment for 15 min did not alter Fshb or Lhb mRNA levels. There were more than five mice per group. C, Pituitary expression of transcription factors regulating Fshb. Changes in the expression of pituitary Fshb mRNA were associated with reduced expression transcription factors known to regulate Fshb transcription, including activator protein 1 family members Fos, FosB, JunB (but not Jun or JunD), and Gata2 but not Foxl2. Expression levels of Foxo1, Foxo3, Inha, Inhba, and Inhbb were not markedly changed. Expression levels of other pituitary hormones (Cga, Gh, Prl, Tshb, and Pomc) also did not change (data not shown). D, Pituitary expression and localization of FOXO1 and FOXO3. Pituitaries from control or Foxo1/3 dKO mice at 2 months of age or older were collected and fixed. Whole pituitary images were taken at ×5 objective, whereas the anterior pituitary regions (represented by the black square in the first image) were taken at ×20 objective. No obvious changes were found in the immuno-histochemical localization of FOXO1 or FOXO3 in the pars distalis, pars intermedia, or pars distalis regions of the pituitary. FOXO1 was predominately expressed in the pars distalis, whereas FOXO3 was expressed in the pars distalis and the pars nervosa. There were at least five mice in each group. Asterisk indicates statistically significantly different (P < 0.05).

At the pituitary level, Fshb was reduced significantly in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice compared with controls (Fig. 3B) and mirrored the drop in serum levels of FSH in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice (Figs. 2A and 3A). The dramatic changes in Fshb expression were associated with the marked reduction of transcription factors known to control Fshb expression, such as activator protein 1 family members (cFos, FosB, and JunB but not c-Jun or JunD) (44) and Gata2 (45) (Fig. 3C). Importantly and strikingly, there were no changes in Lhb mRNA in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice compared with controls. However, pituitary Fshb and Lhb were markedly increased in control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice after ovariectomy and in the Foxo1f/−;Foxo3−/−;Amhr2-Cre mice that lack follicles and exhibit premature ovarian failure. No changes were observed in expression of Fshb or Lhb after the acute GnRH treatment.

The reduction of Fshb mRNA in the pituitary is unlikely due to leakage of Foxo1 and Foxo3 recombination in the pituitary. First, Foxo1 and Foxo3 mRNA levels were similar in the mutant and wild-type pituitary samples (Fig. 3C). Immunostaining of FOXO1 and FOXO3 exhibited similar patterns and intensities in the pituitaries of control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice: FOXO1 was preferentially localized to the pars distalis and intermedia, whereas FOXO3 was localized to the pars distalis and pars nervosa in each genotype (Fig. 3D). Additionally, no significant differences were observed in the expression of other genes [activin (Inhba, Inhbb) or inhibin (Inha) or Foxl2] known to regulate Fshb transcription (Fig. 3C) (43, 46, 47) or in the expression of genes encoding other pituitary hormones (Cga, Gh, Prl, Tshb, and Pomc) (data not shown). Lastly, the Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−Cyp19-Cre mice exhibited a phenotype similar to that of the Foxo1f/−;Foxo3f/−;Amhr2-Cre mice, reinforcing the granulosa cell-specific disruption of the Foxo genes. Recent reports have documented that a stable form of FOXO1 suppresses Lhb transcription (48) and Fshb transcription (49, 50), and therefore, an increase in Lhb and Fshb would be expected with reduced expression Foxo1 or Foxo3. Because Lhb expression does not increase and Fshb was dramatically repressed in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice, these provide addition evidence that pituitary recombination of the Foxo genes is not occurring in the mutant mice. Collectively, these data document that decreased expression of Fshb in the pituitary of the Foxo1/3 dKO mice is related to the marked reduction of specific transcriptional regulators but not to changes in the expression of the Foxo1 and Foxo3, activin or inhibin genes in the mutant pituitary. Thus, inhibition of Fshb in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice appears to be caused by ovarian-derived factors that are not easily assigned to one of the classical negative feedback modulators (steroids or inhibin) of pituitary function (43, 51).

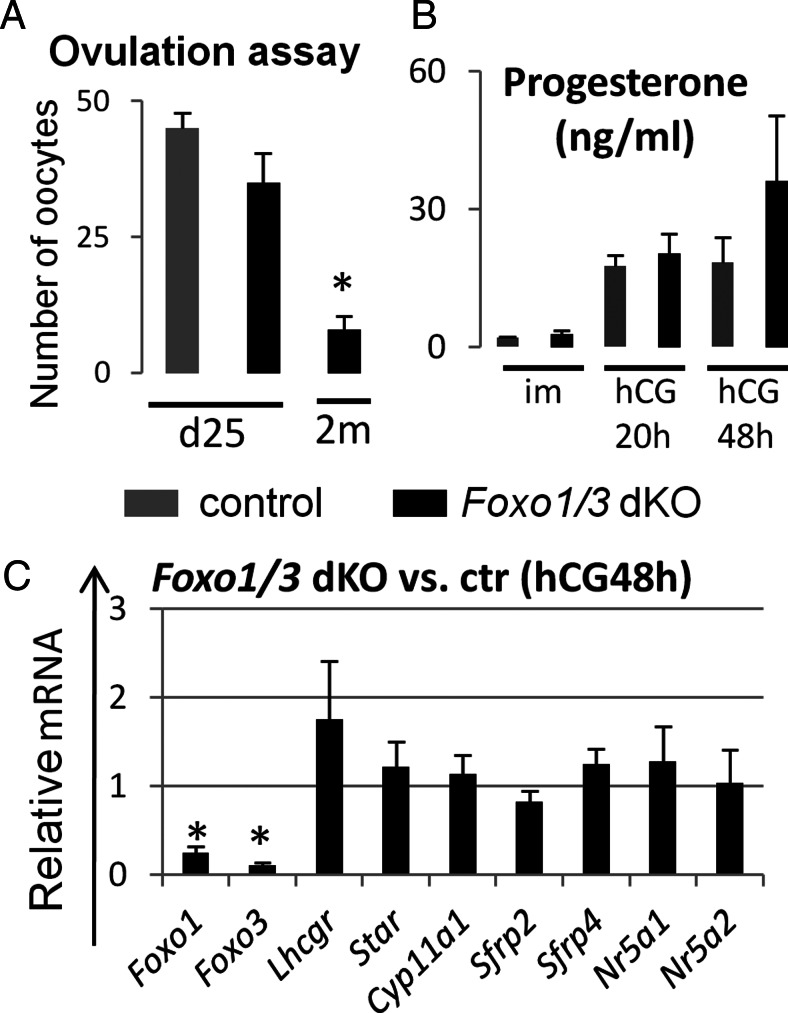

FSH rescue of ovarian follicular development in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice is age dependent

The suppressed levels of FSH in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice indicated that this could contribute to the impaired growth of follicles in the mutant ovaries. When a superovulation regimen of equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (31) was administered to immature (d 25) Foxo1/3 mutant mice, the number of cumulus cell-oocyte complexes that were ovulated at 20 h after hCG was slightly lower but not significantly different from that in similarly treated control mice of the same age (Fig. 4A). Serum levels of progesterone in the Foxo1/3 dKO at 20 and 48 h after hCG were also comparable with wild-type mice (Fig. 4B), and no significant differences were observed in the expression of luteal cell marker genes, such as Lhcgr, Star, Cyp11a1, Sfrp4, and Nr5a1 (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that ovulation and steroidogenesis could be rescued in ovaries of immature Foxo1/3 dKO mice. However, by 2 months of age and older, the Foxo1/3 dKO mice exhibited significantly impaired responses to gonadotropic hormone stimulation. Only a few cumulus cell-oocyte complexes ovulated (Fig. 4A), and few or no corpora lutea were observed after hCG (data not shown). The progressive loss of response to gonadotropins in the Foxo1/3 mutant mice indicates that defects in follicular development become more severe with increasing age and persistently low levels of serum FSH.

Fig. 4.

FSH rescue of ovarian follicular development in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice is age dependent. A, Ovulation induction. Control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice were treated with 4 IU of eCG (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) followed by 48 h later an injection of 5 IU of hCG (Organon Special Chemicals, West Orange, NJ) at d 25 and 2 months (2m) of age. The ovulated eggs were collected from the oviduct 20 h after hCG and counted. Control and Foxo1/3 dKO mice responded to a superovulation regimen at d25. However, the response of the mutant mice was severely reduced at 2 months. There were more than four mice per group. B, Serum hormone levels. Progesterone levels in serum collected before eCG and at 20 and 48 h after hCG in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice were comparable with those in control mice. There were more than four mice per group. C, Gene expression patterns. Total RNA was extracted from whole ovaries collected from control (ctr) and Foxo1/3 dKO mice at 48 h after hCG (hCG48h). Expression levels of luteal cell markers (Lhcgr, Star, Cyp11a1, Sfrp2, and Sfrp4) and transcription factors that impact steroidogenesis (Nr5a1 and Nr5a2) were similar in control and mutant ovaries, whereas expression of Foxo1 and Foxo3 were markedly reduced. There were more than four mice per group. Asterisk indicates statistically significantly different (P < 0.05).

Targeted disruption of Foxo1/3 in granulosa cells alters ovarian gene expression

Targeted loss of Foxo1 and Foxo3 in granulosa cells causes impaired follicle development that is partially, but not completely, dependent on ovarian-mediated suppression of pituitary Fshb transcription and serum FSH. To identify specific Foxo1/3 target genes, granulosa cells were isolated from control mice at d 25 of age and from Foxo1/3 dKO mice at d 25 and 2 months of age. These time points were selected to analyze the expression profiles of genes in granulosa cells of growing follicles from immature control and mutant mice where corpora lutea are absent.

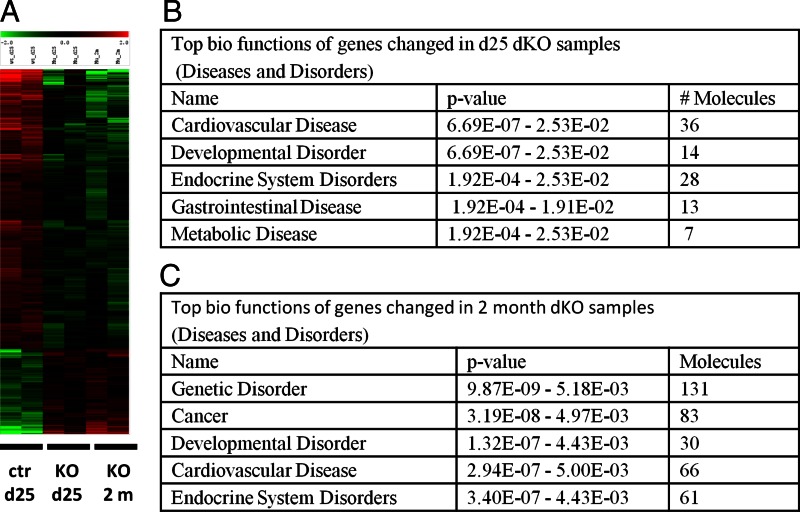

Heat-maps generated from the microarray data revealed that many genes were regulated in the Foxo1/3 mutant granulosa cells compared with control cells (Fig. 5A) and were confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (Supplemental Table 2). Ingenuity pathway analysis identified “Endocrine System Disorders” and “Developmental Disorder” as some of the top gene clusters enriched in the mutant samples collected at d 25 and at 2 months of age consistent with the idea that FOXO1/3 control an important network of genes necessary for normal follicular development (Fig. 5, B and C, and Supplemental Tables 3 and 4).

Fig. 5.

Targeted disruption of Foxo1/3 in granulosa cells alters ovarian gene expression profiles. A, Microarray data and analyses. Granulosa cells were isolated from ovaries of control (ctr) mice at 25 d and from Foxo1/3 dKO (KO) mice at d 25 or 2 month (2m) of age. Total RNA was extracted and submitted for microarray hybridization. Heat-maps generated from the microarray data reveal that many genes are up- and down-regulated in the Foxo1/3 mutant granulosa cells compared with control cells. B, Biofunctional categories. Ingenuity Systems analyses were used to identify genes and functional categories that changed in samples of the Foxo1/3 dKO collected on d 25 and 2 months compared with controls at d 25 of age. Detailed gene lists are provided in Supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

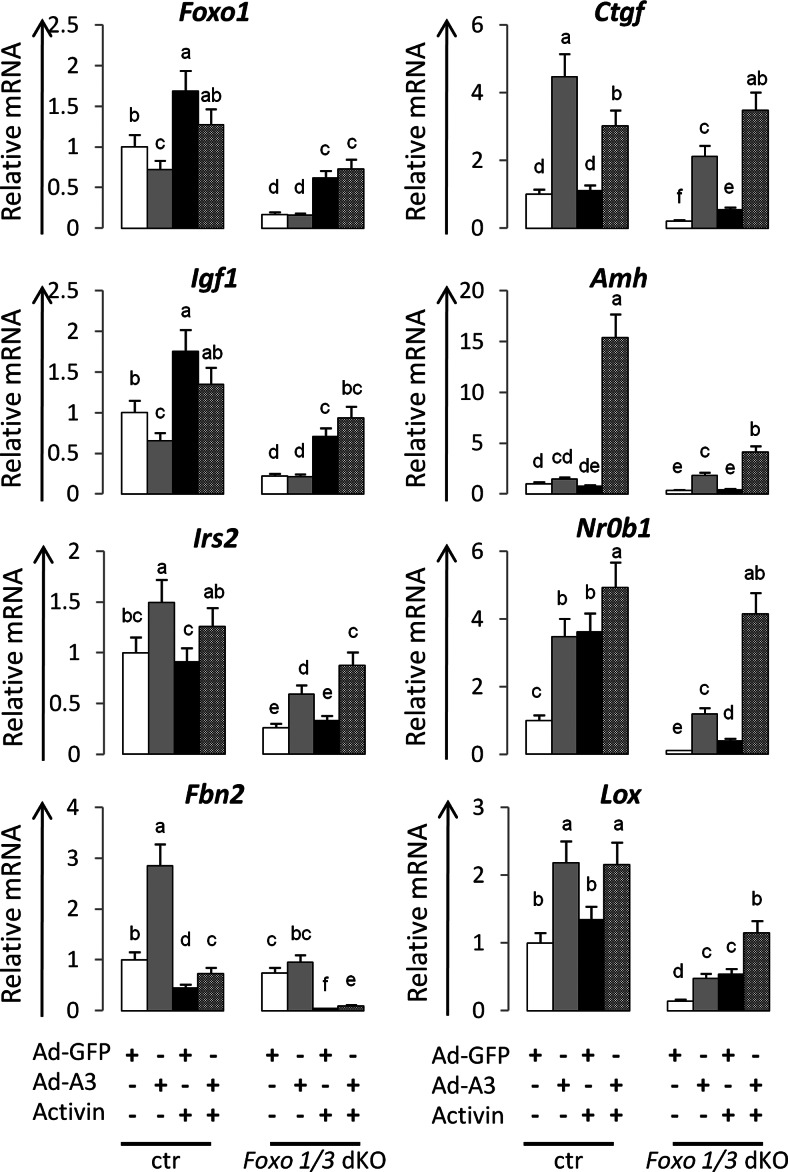

Targeted disruption of Foxo1/3 in granulosa cells identifies FOXO target genes that are also regulated by activin and BMP2

Based on genes identified by the Ingenuity analyses (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4), our analyses of the array data, and evidence that follicle growth and apoptosis are impaired (Fig. 1C), we sought to determine whether the expression of activin and/or BMP2 or targets of these hormones were altered in the Foxo1/3 mutant cells. Accordingly, granulosa cells were isolated from control and mutant immature mice and cultured in media alone, with activin, BMP2, and/or the stable active form of FOXO1 (FOXO1A3) (4).

Genes regulated in granulosa cells of growing follicles

Igf1 is a gene critical for granulosa cell proliferation and ovarian follicle development (17, 23). Genes encoding components of the IGF pathway were down-regulated in the Foxo1/3 mutant cells in culture compared with controls (Supplemental Table 2). Expression of Foxo1was enhanced by activin (and BMP2) in the control and Foxo1/3 dKO cells (Fig. 6 and data not shown), indicating that the Foxo1 gene was not disrupted in all cells of the Foxo1/3 mutant mice (note that the amplifying primers specifically target the deleted region of the Foxo1 gene). These results support the immuno-histochemical analyses showing that some granulosa cells retain FOXO1, whereas most do not (Fig. 1C). Foxo3 was low and not regulated by either activin (or BMP2) in control and Foxo1/3 mutant cells (data not shown). Expression of Igf1, like Foxo1, was increased by activin in control and mutant cells. In contrast, the stable active form of FOXO1 (FOXO1A3) alone but not activin alone increased the expression of Irs2 in control and Foxo1/3-depleted cells indicating that the Irs2 gene may be a direct target of FOXO factors. FOXO1A3 did not markedly alter the responses of activin (or BMP2) on Foxo1 or Igf1 expression indicating that these are primarily targets of activin (or BMP2) in this context (Fig. 6 and data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Targeted disruption of Foxo1/3 in granulosa cells alters genes regulated by activin. FOXO and activin target genes. Control (ctr) and Foxo1/3 mutant granulosa cells were isolated and cultured in media alone, with activin (AA, 40 ng/ml), or an adenoviral (Ad-) vector expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) or a stable form of FOXO1 (A3) for 24 h and RNA prepared for qPCR. Genes of Igf1 signaling pathway (Foxo1, Igf1, and Irs2), genes highly expressed in growing follicles (Ctgf, Lox, Amh, and Nr0b1), and genes regulating the TGFβ pathway (Fbn2) were differentially regulated by FOXO1A3 and activin. The values shown represent the average fold induction from three experiments. Data were analyzed by using GraphPad Prism Programs (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA) and Dunnett's post hoc test after ANOVA to compare means of each treatment group. Letters a to f indicate significantly different expression levels (P < 0.05). Groups with no common letters are statistically significantly different.

By contrast, specific genes that are highly expressed in granulosa cells of growing follicles and that are suppressed in the Foxo1/3 mutant cells in vivo (Supplemental Table 2) are regulated by FOXO and activin in culture. These include: connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf), lysyl oxidase (Lox), anti-Müllerian hormone (Amh), and nuclear receptor family member 0b1 (Nr0b1) (also known as Dax1) (Fig. 6). In other tissues, TGFβ and FOXO1 act coordinately to induce Ctgf (52). Therefore, we reasoned that activin and FOXO1/3 might regulate the high expression of the Ctgf, Lox, Nr0b1, and Amh genes in granulosa cells (53). Indeed, FOXO1A3 alone increased the expression of Ctgf, Lox, and Nr0b1 in the control and Foxo1/3 mutant cells but was less effective in increasing Amh (Fig. 6). Activin alone increased Lox expression in the mutant but not control cells. However, when cells were treated with activin and FOXO1A3, the expression of Amh was dramatically enhanced in the control cells, whereas expression of Ctgf, Lox, Nr0b1, and Amh were enhanced in the Foxo1/3-depleted cells. These results indicate that Ctgf, Lox, Amh, and Nr0b1 are targets of FOXO1/3 and activin in granulosa cells and that (with the exception of Amh) the effects of activin and FOXOA3 are most dramatic when endogenous levels of FOXO1/3 are reduced. Nr0b1, like Ctgf, is down-regulated by BMP2 alone in the control cells (data not shown).

Based on the microarray data, Fibrillin2 (Fbn2) was one of the most severely repressed genes in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice. Fbn2 mRNA is markedly up-regulated by FOXO1A3 alone in control cells but surprisingly less so in the Foxo1/3 mutant cells. Activin alone (and BMP2) potently down-regulated Fbn2 expression in control and mutant cells and suppressed the inductive effects of FOXO1A3 (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Thus, the regulation of Fbn2 expression appears to be complex and acutely dependent on the levels of activin, BMP2, and FOXO1/3 in granulosa cells.

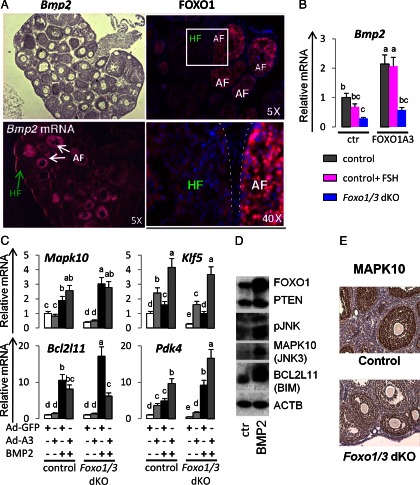

Genes regulated in granulosa cells undergoing metabolic stress and apoptosis

FOXO1 is not only expressed in granulosa cells of healthy growing follicles but is also highly expressed in granulosa cells of follicles undergoing atresia (Fig. 7A) (11), and in these cells, FOXO1 is predominantly nuclear. BMP2 is expressed selectively in granulosa cells of follicles undergoing atresia (Fig. 7A) (29) indicating that it is also related to granulosa cell apoptosis. Thus, the reduced expression of Bmp2 observed in the Foxo1/3-depleted cells (Fig. 7B) rationalizes the reduced levels of apoptosis observed in the mutant cells (Fig. 1C). In addition, genes associated with metabolic stress and apoptosis in other cell types, including Krüppel-like factor 5 (Klf5) (54), mitogen-activated protein kinase 10 (Mapk10) (also known as Jnk3) (55), Bcl2l11 (also known as bcl-2 interacting protein Bim) (56), and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (Pdk4) (57), were also decreased markedly in the Foxo1/3 mutant cells (Fig. 7, C–E). FOXO1A3 alone increased expression of Bmp2 (Fig. 7B). Either FOXO1A3 or BMP2 alone induced Klf5 and Pdk4, whereas BMP2 alone more potently increased Bcl2l11 (Fig. 7, C and D) and Mapk10 (Fig. 7, C and D). Thus, Klf5, Pdk4, and Bmp2 appear to be FOXO1/3 target genes. Collectively, these results demonstrate a positive regulatory loop, by which BMP2 and FOXO1 regulate each other and genes in granulosa cells of follicles undergoing atresia. Furthermore, selected responses of the granulosa cells to activin A and BMP2 are distinct: activin A suppresses Klf5 (data not shown) and BMP2 suppresses Ctgf and Nr0b1 (data not shown), thereby exerting antagonistic cell fate decisions in granulosa cells.

Fig. 7.

FOXOs and BMP2 regulate metabolic stress and apoptotic genes. A, FOXO and BMP are expressed in apoptotic granulosa cells. FOXO1 protein and Bmp2 mRNA were localized to granulosa cells of follicles undergoing atresia by immunostaining and in situ hybridization, respectively. Ovarian sections were obtained from immature mice primed with eCG, 48 h. HF, Healthy follicle; AF, atretic follicle. B, FOXO1 and FSH regulate Bmp2 mRNA expression levels. Bmp2 mRNA levels were decreased by FSH in cultured wild-type granulosa cells and in Foxo1/3 mutant granulosa cells. Overexpression of a stable FOXO (FOXO1A3) increased Bmp2 levels in wild-type granulosa cells, even in the presence of FSH. FOXO1A3 also restored Bmp2 levels in Foxo1/3 mutant cells. The values represent the average fold induction from four experiments. C, FOXO1 and BMP2 regulate apoptosis-related genes. Granulosa cells from control and mutant mice were cultured and treated with BMP2 or FOXO1A3 as in Fig. 6. RNA was prepared for qPCR analyses of genes (Mapk10, Klf5, Bcl2l11, and Pdk4) down-regulated in granulosa cells of the Foxo1/3 dKO mice and that are involved in apoptosis. The values represent the average fold induction from three experiments. Letters a to c indicate significantly different expression levels (P < 0.05). Groups with no common letters are statistically significantly different. D, BMP2 increased FOXO1, BCL2L11 (BIM), and MAPK10 (JNK3) protein levels. Wild-type granulosa cells were cultured in defined media with or without BMP2 for 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared for Western blot analyses with antibodies to FOXO1, phosphatase and tensin homolog, pan-phopho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase MAPK10 (JNK3), and BCL2L11 (BIM). β-Actin (ACTB) was measured as a loading control. A representative figure of two replicates is shown. E, MAPK10 localization and expression. Ovaries were collected from control and Foxo1/3 mutant mice, fixed, processed, sectioned, and stained with an antibody specific for MAPK10. MAPK10 is selectively expressed in granulosa cells and decreased in these cells in the Foxo1/3 dKO ovaries. Ovaries from at least four mice in each group were analyzed. Ad, Adenoviral; ctr, control.

Discussion

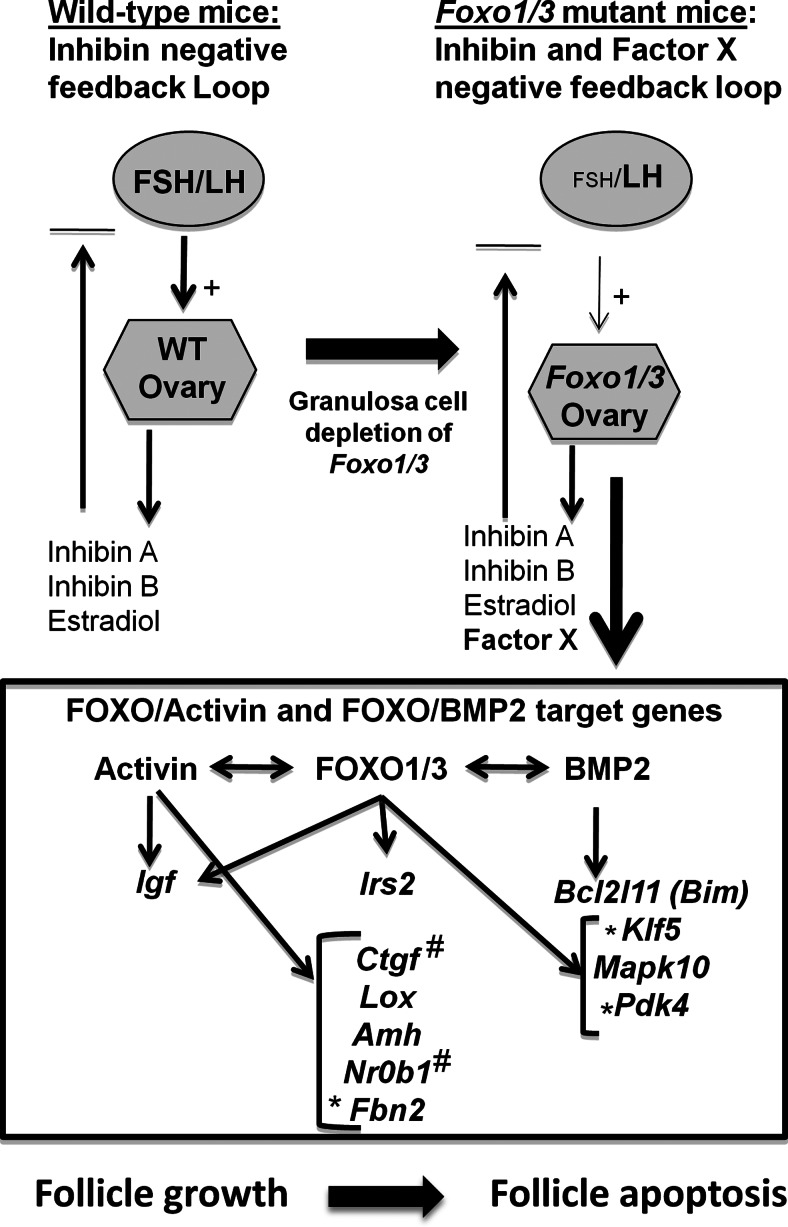

These studies document for the first time that FOXO1 and FOXO3 function within granulosa cells as critical mediators of normal ovarian follicular development and luteinization in the mouse. Loss of Foxo1/3 not only alters the expression of specific genes in granulosa cells but also establishes a novel endocrine regulatory loop between the ovary and the pituitary-hypothalamic endocrine axis (Fig. 8). Targeted disruption of Foxo1 and Foxo3 in granulosa cells leads to the production of an ovarian-derived factor(s) that potently suppresses pituitary FSH biosynthesis by repressing the expression of transcriptional regulators of the pituitary Fshb gene. Although the nature of the ovarian-derived factor(s) remains to be identified, it (they) do not appear to be one of the classical steroids or inhibin (43, 51), based on serum levels of these hormones and ovarian levels of mRNAs encoding inhibins and steroidogenic enzymes in the in the Foxo1/3 mutant mice. Because FOXO1/3 can act as potent antagonists of FSH-mediated differentiation in granulosa cells (4, 22), the negative loop to the pituitary that is induced in the Foxo1/3 mutant cells may serve a specific endocrine function. That is, reducing FSH actions would prevent premature or unwanted proliferation and differentiation.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of the physiological and functional consequences of Foxo1/3 gene depletion in granulosa cells. Ovaries in the Foxo1/3 dKO mice express a factor(s)(X), other than or in addition to the classical steroids and inhibin, that potently inhibits pituitary Fshb expression and genes controlling transcription of the Fshb gene. Within the ovary, FOXO1/3 interact with activin to regulate genes controlling follicle growth or with BMP2 to control genes associated with metabolic stress and apoptosis leading to follicle death (see text for further discussion). *, Genes selectively suppressed by activin but induced by BMP2; #, a gene selectively suppressed by BMP2.

To our knowledge, the granulosa Foxo1/3 mutant mouse phenotype is distinct from the Fshb knockout mice (58) and other infertile mutant mouse models where depletion of follicles leads to increased, rather than decreased serum FSH (2). Importantly, the endocrine effects of depleting Foxo1/3 in granulosa cells in vivo highlight recent evidence that FOXO1/3 selectively regulate tissue homeostasis and metabolism by producing factors that control the endocrine systems on which these tissues interact and depend (7, 8). Notably, depleting Foxo1/3 in osteoblasts regulates the synthesis of a factor that controls insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells. This in turn alters glucose metabolism that is critical to osteoblast functions (8). Thus, FOXO1/3 can exert pervasive and far-reaching effects in mammalian systems that may be reminiscent of those in C. elegans (6).

At the ovarian level, the loss of both Foxo1 and Foxo3 (but neither one alone) leads to 1) abnormal follicle development and homeostasis that becomes progressively more severe with time, 2) reduced granulosa cell apoptosis and differentiation, 3) the absence of corpora lutea, and 4) reduced responses to FSH and LH. The coordinate functions of FOXO1 and FOXO3 in granulosa cells differ markedly from the predominant role of FOXO3 in oocytes that restricts oocyte growth and prevents primordial follicles from leaving the resting, quiescent pool (2, 3, 27), and conversely, the predominant role of FOXO1 in preserving the spermatogonial stem cell pool (13). In this regard, the roles of FOXO1 and FOXO3 in germ cells are reminiscent of their ability to promote quiescence and self-renewal in neuronal and embryonic stem cells, respectively (59, 60). Furthermore, although the loss of Pten, like the depletion of Foxo3, in oocytes promotes oocyte growth and premature activation of primordial follicles and ovarian failure (61), the loss of Pten in granulosa cells promotes follicle growth and enhances fertility (31). Thus, the reduced activity of FOXO1/3 in the Pten mutant granulosa cells is not sufficient to impair follicle growth or luteinization (or pituitary FSH?) but does reduce apoptosis.

At the molecular level, depletion of granulosa cell Foxo1 and Foxo3 in vivo reveals novel evidence that FOXOs interact with both the activin and BMP2 pathways to control remarkably different cell fates-follicle growth vs. apoptosis (Fig. 8). Although exogenous FSH alone can restore ovulation in the immature mutant mice, it does not globally reverse the aberrant gene expression profiles in the Foxo1/3 mutant cells at this time (data not shown) and actually suppresses the expression of many FOXO1/3-regulated genes (Supplemental Fig. 3) (4). As a consequence, the molecular changes that occur in the Foxo1/3-depleted granulosa cells cannot be explained entirely by reduced levels of serum FSH. Furthermore, although FOXO1 has been implicated as an antagonist of FSH-mediated gene expression profiles (4, 62), the studies herein document for the first time 1) that this is not the only function of FOXO1/3 in granulosa cells and 2) that FOXO1/3 act coordinately with either activin or BMP2 pathways to regulate distinct granulosa cell fates-growth and differentiation or apoptosis, respectively.

IGF-I acts via the PI3K/serine-threonine kinase pathway in granulosa cells to reduce FOXO1/3 activity (10), whereas depletion of Foxo1/3 reduces expression of Igf1 and Irs2. These data suggest that a homeostatic regulatory loop may exist between the IGF-I and FOXO1/3 pathways in granulosa cells. Moreover, Igf1 is regulated by either activin or BMP2 independently of Foxo1/3 indicating that the multiple potential SMAD (mothers against decapentaplegic homolog) and FOXO binding sites present in the Igf1 promoter (Supplemental Table 5) do not act synergistically to regulate expression of this gene. Conversely, the expression of Irs2 is preferentially regulated by FOXOA3. Thus, depletion of Foxo1/3 disrupts this intracrine granulosa cell regulatory network associated with granulosa cell metabolism and follicle growth.

The elevated levels of Ctgf, Lox, Amh, and Nr0b1 mRNAs in granulosa cells of growing follicles (53, 63) is critically dependent FOXO1/3 activity, because the stable active FOXO1A3 alone increased expression of each these genes in control and Foxo1/3 mutant cells. Although activin alone had little or no effect and BMP2 suppressed Ctgf expression in control cells, both acted synergistically with FOXO1A3 to increase Ctgf expression in the Foxo1/3 mutant cells. These results confirm other studies showing that activin and TGFβ can increase expression of these genes in granulosa cells, whereas FSH is a potent inhibitor (Supplemental Fig. 3) (53). These results also support a previous study, in which Ctgf was shown to be a target gene of both FOXO1 and TGFβ1/SMAD2/3s in human keratinocytes and breast cancer cells (1, 52) and where functional FOXO and SMAD binding elements were identified in the promoter of the Ctgf gene (Supplemental Table 5) (52). That both CTGF and FOXO1 are critical for osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (7, 64, 65) suggests that similar interactions between FOXO1 and activin or BMP2 may be critical for osteoblast homeostasis and differentiation. Targeted disruption of Ctgf in granulosa cells leads to infertility at a late age (66). That a more dramatic phenotype is not observed in the Ctgf mutant mouse model may be due to the expression of Cyr61, a closely related member of this family.

In contrast to Ctgf, the expression of Lox, Nr0b1, and especially Amh was increased not only by FOXO1A3 but also preferentially by activin compared with BMP2. These data are the first to document that the Amh gene is a potential target of FOXO1/3 and activin and could have clinical relevance for polycystic ovary syndrome patients where serum and follicular AMH is elevated (67–69). These results highlight the ability of FOXO1/3 to control genes that are selectively regulated by either the activin or BMP2 pathways. In silico approaches indicate that the Lox and Amh promoters have FOXO and SMAD binding sites, whereas the Nr0b1 promoter has putative FOXO but no SMAD binding sites (Supplemental Table 5). Nr0b1 is of interest because it is a potent negative regulator of many nuclear receptor transcription factors (62) and therefore may control multiple FOXO-related functions in granulosa cells, including genes involved in metabolism and steroid biosynthesis (4, 22).

The fibrillins, Fbn1 and Fbn2, are components of the extracellular matrix and can modulate BMP signaling to regulate osteoblast differentiation (70). FBN2 may also be a FOXO target gene and part of a regulatory loop between activin and BMP2 signaling pathways during follicle development, because: 1) the Foxo1/3 mutant cells express reduced levels of Fbn2 and to a lesser extent Fbn1 (data not shown), 2) FOXO1A3 alone increased Fbn2 expression in control cells, and 3) activin potently suppresses expression of this gene even in the presence of FOXOA3.

In contrast to the interactions of activin and FOXO1/3, BMP2 and FOXO1/3 appear to comprise an intracrine regulatory loop in granulosa cells that selectively senses metabolic stress and controls cell death (Fig. 7A) (29). BMP2 regulates the expression of Foxo1, and FOXO1 regulates the expression of Bmp2. Alone and together, FOXO1 and BMP2 promote the expression of genes that are associated with granulosa cell metabolic stress and apoptosis: Bim, Klf5, Mapk10 (Jnk3), and Pdk4. Klf5 is particularly interesting, because it is a transcription factor with an unexplored role in granulosa cells and because our data indicate that Klf5: 1) is suppressed in the Foxo1/3-depleted cells in which apoptosis is restricted, 2) is suppressed selectively by activin, but 3) is specifically increased by FOXO1 (Fig. 7C) (4) and BMP2. The marked induction of this gene by FOXO1A3 is likely mediated by one or more of the six potential FOXO binding sties in the Klf5 promoter (Supplemental Table 5). KLF5 also interacts with estrogen receptor β (ESR2) to regulate the expression of Foxo1 (54) and impacts genes in lipid biosynthesis and in the TGFβ pathway (71). The expression of Mapk10 in granulosa cells represents the first demonstration of this gene in the ovary as well as its regulation by FOXO1 and BMP2. Because Mapk10 is associated with neuronal cell death (72), it may contribute a similar role in granulosa cells. PDK4 is a key sensor of nutrient stress and regulator of glucose metabolism. Although it has previously been shown to be a target of FOXO1 (57, 73), the inductive role of BMP2 has not been documented and thus provides a novel role for this growth factor in granulosa cells.

In summary, our studies provide a new paradigm and a potential model to explain the diverse actions of FOXOs in a tissue where activins and BMPs exert opposing responses that are critical for cell and tissue homeostasis at precise developmental stages (Fig. 8). With activin, FOXO1 promotes follicle growth; with BMP2, it favors apoptosis. A similar paradigm may operate in other tissues. Remarkably, and quite unexpectedly, disruption of follicle growth in the Foxo1/3 mutant mice leads to metabolic changes and the production of a factor(s) that exerts potent negative feedback to prevent expression of pituitary Fshb. Decreased levels of serum FSH further restrict follicle growth and development, ultimately preventing ovulation. These results provide evidence that ovarian release of these factor(s) may be part of a critical negative regulatory loop that evolved to prevent unrestricted proliferation and/or premature differentiation of granulosa cells in follicles where apoptosis is impaired. These studies document that the ovary is a prime target of FOXO1/3 action and has established a new paradigm of FOXO actions in this endocrine system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants HD-16272 and HD-16229 (to J.S.R. and Z.L.) and HD-48690 (to D.H.C.). Serum hormone measurements were performed by the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research (SCCPIR) Grant U54-HD28934.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- Amh

- Anti-Müllerian hormone

- Bcl2l11

- Bcl-2-like protein 11

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- Ctgf

- connective tissue growth factor

- dKO

- double conditional knockout

- eCG

- equine chorionic gonadotropin

- Fbn2

- Fibrillin2

- Klf5

- Krüppel-like factor 5

- FOXO

- Forkhead boxO

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- Jnk

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- KO

- knockout

- Lox

- lysyl oxidase

- Mapk10

- mitogen-activated protein kinase 10

- Nr0b1

- nuclear receptor family member 0b1

- Pdk4

- pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- SMAD

- mothers against decapentaplegic homlog.

References

- 1. Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, Ji H, Xiao Y, Ding Z, Miao L, Tothova Z, Horner JW, Carrasco DR, Jiang S, Gilliland DG, Chin L, Wong WH, Castrillon DH, DePinho RA. 2007. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell 128:309–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castrillon DH, Miao L, Kollipara R, Horner JW, DePinho RA. 2003. Suppression of ovarian follicle activation in mice by the transcription factor Foxo3a. Science 301:215–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu L, Rajareddy S, Reddy P, Du C, Jagarlamudi K, Shen Y, Gunnarsson D, Selstam G, Boman K, Liu K. 2007. Infertility caused by retardation of follicular development in mice with oocyte-specific expression of Foxo3a. Development 134:199–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu Z, Rudd MD, Hernandez-Gonzalez I, Gonzalez-Robayna I, Fan HY, Zeleznik AJ, Richards JS. 2009. FSH and FOXO1 regulate genes in the sterol/steroid and lipid biosynthetic pathways in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 23:649–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Accili D, Arden KC. 2004. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell 117:421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCormick M, Chen K, Ramaswamy P, Kenyon C. 2012. New genes that extend Caenorhabditis elegans' lifespan in response to reproductive signals. Aging Cell 11:192–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kousteni S. 2012. FoxO1, the transcriptional chief of staff of energy metabolism. Bone 50:437–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rached MT, Kode A, Silva BC, Jung DY, Gray S, Ong H, Paik JH, DePinho RA, Kim JK, Karsenty G, Kousteni S. 2010. FoxO1 expression in osteoblasts regulates glucose homeostasis through regulation of osteocalcin in mice. J Clin Invest 120:357–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Vos KE, Coffer PJ. 2008. FOXO-binding partners: it takes two to tango. Oncogene 27:2289–2299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Richards JS, Sharma SC, Falender AE, Lo YH. 2002. Expression of FKHR, FKHRL1, and AFX genes in the rodent ovary: evidence for regulation by IGF-I, estrogen, and the gonadotropins. Mol Endocrinol 16:580–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shi F, LaPolt PS. 2003. Relationship between FoxO1 protein levels and follicular development, atresia, and luteinization in the rat ovary. J Endocrinol 179:195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burns KH, Owens GE, Ogbonna SC, Nilson JH, Matzuk MM. 2003. Expression profiling analyses of gonadotropin responses and tumor development in the absence of inhibins. Endocrinology 144:4492–4507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goertz MJ, Wu Z, Gallardo TD, Hamra FK, Castrillon DH. 2011. Foxo1 is required in mouse spermatogonial stem cells for their maintenance and the initiation of spermatogenesis. J Clin Invest 121:3456–3466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. John GB, Gallardo TD, Shirley LJ, Castrillon DH. 2008. Foxo3 is a PI3K-dependent molecular switch controlling the initiation of oocyte growth. Dev Biol 321:197–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gougeon A. 1996. Regulation of ovarian follicular development in primates: facts and hypotheses. Endocr Rev 17:121–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richards JS. 2001. Perspective: the ovarian follicle—a perspective in 2001. Endocrinology 142:2184–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhou J, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM, Bondy C. 1997. Insulin-like growth factor I regulates gonadotropin responsiveness in the murine ovary. Mol Endocrinol 11:1924–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pangas SA, Matzuk MM. 2008. The TGF-B family in the reproductive tract. In: Derynck R, Miyazono K, eds. The TGF-b family. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- 19. Richards JS. 1994. Hormonal control of gene expression in the ovary. Endocr Rev 15:725–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shimasaki S, Moore RK, Otsuka F, Erickson GF. 2004. The bone morphogenetic protein system in mammalian reproduction. Endocr Rev 25:72–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matzuk MM. 1995. Functional analysis of mammalian members of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily. Trends Endocrinol Metab 6:120–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park Y, Maizels ET, Feiger ZJ, Alam H, Peters CA, Woodruff TK, Unterman TG, Lee EJ, Jameson JL, Hunzicker-Dunn M. 2005. Induction of cyclin D2 in rat granulosa cells requires FSH-dependent relief from FOXO1 repression coupled with positive signals from Smad. J Biol Chem 280:9135–9148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baker J, Hardy MP, Zhou J, Bondy C, Lupu F, Bellvé AR, Efstratiadis A. 1996. Effects of an Igf1 gene null mutation on mouse reproduction. Mol Endocrinol 10:903–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Robker RL, Richards JS. 1998. Hormone-induced proliferation and differentiation of granulosa cells: a coordinated balance of the cell cycle regulators cyclin D2 and p27Kip1. Mol Endocrinol 12:924–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pisarska MD, Kuo FT, Tang D, Zarrini P, Khan S, Ketefian A. 2009. Expression of forkhead transcription factors in human granulosa cells. Fertil Steril 91:1392–1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gross DN, van den Heuvel AP, Birnbaum MJ. 2008. The role of FoxO in the regulation of metabolism. Oncogene 27:2320–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hosaka T, Biggs WH, 3rd, Tieu D, Boyer AD, Varki NM, Cavenee WK, Arden KC. 2004. Disruption of forkhead transcription factor (FOXO) family members in mice reveals their functional diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:2975–2980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang H, Tindall DJ. 2007. Dynamic FoxO transcription factors. J Cell Sci 120:2479–2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Erickson GF, Shimasaki S. 2003. The spatiotemporal expression pattern of the bone morphogenetic protein family in rat ovary cell types during the estrous cycle. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 1:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Furuyama T, Kitayama K, Shimoda Y, Ogawa M, Sone K, Yoshida-Araki K, Hisatsune H, Nishikawa S, Nakayama K, Nakayama K, Ikeda K, Motoyama N, Mori N. 2004. Abnormal angiogenesis in Foxo1 (Fkhr)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 279:34741–34749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fan HY, Liu Z, Cahill N, Richards JS. 2008. Targeted disruption of Pten in ovarian granulosa cells enhances ovulation and extends the life span of luteal cells. Mol Endocrinol 22:2128–2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jamin SP, Arango NA, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Behringer RR. 2002. Requirement of Bmpr1a for Mullerian duct regression during male sexual development. Nat Genet 32:408–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pangas SA, Jorgez CJ, Tran M, Agno J, Li X, Brown CW, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM. 2007. Intraovarian activins are required for female fertility. Mol Endocrinol 21:2458–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pangas SA, Li X, Umans L, Zwijsen A, Huylebroeck D, Gutierrez C, Wang D, Martin JF, Jamin SP, Behringer RR, Robertson EJ, Matzuk MM. 2008. Conditional deletion of Smad1 and Smad5 in somatic cells of male and female gonads leads to metastatic tumor development in mice. Mol Cell Biol 28:248–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li Q, Pangas SA, Jorgez CJ, Graff JM, Weinstein M, Matzuk MM. 2008. Redundant roles of SMAD2 and SMAD3 in ovarian granulosa cells in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 28:7001–7011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lan ZJ, Xu X, Cooney AJ. 2004. Differential oocyte-specific expression of Cre recombinase activity in GDF-9-iCre, Zp3cre, and Msx2Cre transgenic mice. Biol Reprod 71:1469–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hsieh M, Mulders SM, Friis RR, Dharmarajan A, Richards JS. 2003. Expression and localization of secreted frizzled-related protein-4 in the rodent ovary: evidence for selective up-regulation in luteinized granulosa cells. Endocrinology 144:4597–4606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu Z, Fan HY, Wang Y, Richards JS. 2010. Targeted disruption of Mapk14 (p38MAPKα) in granulosa cells and cumulus cells causes cell-specific changes in gene expression profiles that rescue cumulus cell-oocyte complex expansion and maintain fertility. Mol Endocrinol 24:1794–1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pierce A, Xu M, Bliesner B, Liu Z, Richards J, Tobet S, Wierman ME. 2011. Hypothalamic but not pituitary or ovarian defects underlie the reproductive abnormalities in Axl/Tyro3 null mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol 339:151–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rozen S, Skaletsky H. 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132:365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. 2003. Exploration, normalization and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4:249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. 2004. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 5:R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bernard DJ, Fortin J, Wang Y, Lamba P. 2010. Mechanisms of FSH synthesis: what we know, what we don't, and why you should care. Fertil Steril 93:2465–2485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang Y, Fortin J, Lamba P, Bonomi M, Persani L, Roberson MS, Bernard DJ. 2008. Activator protein-1 and smad proteins synergistically regulate human follicle-stimulating hormone β-promoter activity. Endocrinology 149:5577–5591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Charles MA, Saunders TL, Wood WM, Owens K, Parlow AF, Camper SA, Ridgway EC, Gordon DF. 2006. Pituitary-specific Gata2 knockout: effects on gonadotrope and thyrotrope function. Mol Endocrinol 20:1366–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Matzuk MM, Kumar TR, Shou W, Coerver KA, Lau AL, Behringer RR, Finegold MJ. 1996. Transgenic models to study the roles of inhibins and activins in reproduction, oncogenesis, and development. Recent Prog Horm Res 51:123–154; discussion 155–127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Justice NJ, Blount AL, Pelosi E, Schlessinger D, Vale W, Bilezikjian LM. 2011. Impaired FSHβ expression in the pituitaries of Foxl2 mutant animals. Mol Endocrinol 25:1404–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Arriola DJ, Mayo SL, Skarra DV, Benson CA, Thackray VG. 2012. FOXO1 transcription factor inhibits luteinizing hormone β gene expression in pituitary gonadotrope cells. J Biol Chem 287:33424–33435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Parikh RV, Park CH, Thackray VG. 2012. FOXO1 diminishes activin signaling in pituitary gonadotrope cells. Endocr Rev 33:SAT-678 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Skarra D, Arriola DJ, Thackray VG. 2012. FOXO1 Inhibition of follicle-stimulating hormone β gene transcription. Endocr Rev 33:SAT-683 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cho BN, McMullen ML, Pei L, Yates CJ, Mayo KE. 2001. Reproductive deficiencies in transgenic mice expressing the rat inhibin α-subunit gene. Endocrinology 142:4994–5004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gomis RR, Alarcón C, He W, Wang Q, Seoane J, Lash A, Massagué J. 2006. A FoxO-Smad synexpression group in human keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:12747–12752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harlow CR, Davidson L, Burns KH, Yan C, Matzuk MM, Hillier SG. 2002. FSH and TGF-β superfamily members regulate granulosa cell connective tissue growth factor gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology 143:3316–3325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nakajima Y, Akaogi K, Suzuki T, Osakabe A, Yamaguchi C, Sunahara N, Ishida J, Kako K, Ogawa S, Fujimura T, Homma Y, Fukamizu A, Murayama A, Kimura K, Inoue S, Yanagisawa J. 2011. Estrogen regulates tumor growth through a nonclassical pathway that includes the transcription factors ERβ and KLF5. Sci Signal 4:ra22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kuan CY, Whitmarsh AJ, Yang DD, Liao G, Schloemer AJ, Dong C, Bao J, Banasiak KJ, Haddad GG, Flavell RA, Davis RJ, Rakic P. 2003. A critical role of neural-specific JNK3 for ischemic apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:15184–15189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gilley J, Coffer PJ, Ham J. 2003. FOXO transcription factors directly activate bim gene expression and promote apoptosis in sympathetic neurons. J Cell Biol 162:613–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kwon HS, Huang B, Unterman TG, Harris RA. 2004. Protein kinase B-α inhibits human pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 gene induction by dexamethasone through inactivation of FOXO transcription factors. Diabetes 53:899–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Burns KH, Yan C, Kumar TR, Matzuk MM. 2001. Analysis of ovarian gene expression in follicle-stimulating hormone β knockout mice. Endocrinology 142:2742–2751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang X, Yalcin S, Lee DF, Yeh TY, Lee SM, Su J, Mungamuri SK, Rimmelé P, Kennedy M, Sellers R, Landthaler M, Tuschl T, Chi NW, Lemischka I, Keller G, Ghaffari S. 2011. FOXO1 is an essential regulator of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 13:1092–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Downing JR. 2011. A new FOXO pathway required for leukemogenesis. Cell 146:669–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Reddy P, Liu L, Adhikari D, Jagarlamudi K, Rajareddy S, Shen Y, Du C, Tang W, Hämäläinen T, Peng SL, Lan ZJ, Cooney AJ, Huhtaniemi I, Liu K. 2008. Oocyte-specific deletion of Pten causes premature activation of the primordial follicle pool. Science 319:611–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Iyer AK, McCabe ER. 2004. Molecular mechanisms of DAX1 action. Mol Genet Metab 83:60–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Slee RB, Hillier SG, Largue P, Harlow CR, Miele G, Clinton M. 2001. Differentiation-dependent expression of connective tissue growth factor and lysyl oxidase messenger ribonucleic acids in rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology 142:1082–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Arnott JA, Lambi AG, Mundy C, Hendesi H, Pixley RA, Owen TA, Safadi FF, Popoff SN. 2011. The role of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in skeletogenesis. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 21:43–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rached MT, Kode A, Xu L, Yoshikawa Y, Paik JH, Depinho RA, Kousteni S. 2010. FoxO1 is a positive regulator of bone formation by favoring protein synthesis and resistance to oxidative stress in osteoblasts. Cell Metab 11:147–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nagashima T, Kim J, Li Q, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Lyons KM, Matzuk MM. 2011. Connective tissue growth factor is required for normal follicle development and ovulation. Mol Endocrinol 25:1740–1759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Franks S, Stark J, Hardy K. 2008. Follicle dynamics and anovulation in polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update 14:367–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pellatt L, Rice S, Mason HD. 2010. Anti-Mullerian hormone and polycystic ovary syndrome: a mountain too high? Reproduction 139:825–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pellatt L, Hanna L, Brincat M, Galea R, Brain H, Whitehead S, Mason H. 2007. Granulosa cell production of anti-Mullerian hormone is increased in polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:240–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nistala H, Lee-Arteaga S, Smaldone S, Siciliano G, Carta L, Ono RN, Sengle G, Arteaga-Solis E, Levasseur R, Ducy P, Sakai LY, Karsenty G, Ramirez F. 2010. Fibrillin-1 and -2 differentially modulate endogenous TGF-β and BMP bioavailability during bone formation. J Cell Biol 190:1107–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wan H, Luo F, Wert SE, Zhang L, Xu Y, Ikegami M, Maeda Y, Bell SM, Whitsett JA. 2008. Kruppel-like factor 5 is required for perinatal lung morphogenesis and function. Development 135:2563–2572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Choi WS, Abel G, Klintworth H, Flavell RA, Xia Z. 2010. JNK3 mediates paraquat- and rotenone-induced dopaminergic neuron death. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 69:511–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wei D, Tao R, Zhang Y, White MF, Dong XC. 2011. Feedback regulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis through modulation of SHP/Nr0b2 gene expression by Sirt1 and FoxO1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300:E312–E320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.