Abstract

Despite the rapidly growing Mexican American population, no studies to date have attempted to explain the underlying relations between family instability and Mexican American children's development. Using a diverse sample of 740 Mexican American adolescents (49% female; 5th grade M age = 10.4; 7th grade M age = 12.8) and their mothers, we prospectively examined the relations between family instability and adolescent academic outcomes and mental health in the 7th grade. The model fit the data well and results indicated that family instability between 5th and 7th grade was related to increased 7th grade mother-adolescent conflict and in turn, mother-adolescent conflict was related to decreased school attachment and to increased externalizing and internalizing symptoms in the 7th grade. Results also indicated that 7th grade mother-adolescent conflict mediated the relations between family instability and 7th grade academic outcomes and mental health. Further, we explored adolescent familism values as a moderator and found that adolescent familism values served as a protective factor in the relation between mother-adolescent conflict and grades. Implications for future research and intervention strategies are discussed.

Keywords: family instability, Mexican American, adolescent, adjustment, mental health

Family instability is a risk factor that has been found to threaten child development (e.g., Donahue et al., 2010) and 37% of children in the United States (U.S.) have experienced family instability by the age of 14 (Cavanaugh, 2008). Adolescents simultaneously undergo biological, educational, and social transitions that are often linked to negative consequences (Simmons, Burgeson, Carlton-Ford, & Blyth, 1987). Notably, the transition from elementary to junior high school can be particularly stressful for adolescents (Seidman, Lambert, Allen, & Aber, 2003) and is associated with a decline in academic success (Eccles & Roeser, 2009). Experiencing family instability during this transition adds stress to an already stressful period, with the likelihood of exacerbating risk for negative development. The primary goal of this study was to examine the relations between family instability, during the transition from elementary to junior high school, and Mexican American adolescent development with a focus on examining underlying processes that may help explain these relations. Although family instability typically has been defined by family structure changes (e.g., Cavanaugh, 2008) and parental divorce/separations (e.g., Donahue et al., 2010), some authors (e.g., Forman & Davies, 2003; Marcnyszyn, Evans, & Eckenrode, 2008) have considered residence changes, job losses, and adolescent school changes as indicators of family instability. In order to better inform intervention efforts, researchers must learn how specific indicators of family instability influence child development; combining several indicators of family instability to yield a cumulative count makes this difficult. Thus, the current study defined family instability by a sole indicator, maternal relationship transitions (separation/divorce, death of a partner, and/or new partner).

Incorporating Mexican Americans into Family Instability Research

Family instability research with Mexican Americans is needed for several reasons. First, Latinos are the largest, and one of the fastest growing, ethnic minority groups in the U.S (Motel & Patten, 2012). Second, Mexican Americans account for nearly 65% of Latinos. Third, research has commonly found family instability to be related to adolescent negative academic outcomes and poor mental health (e.g., Cavanaugh & Fomby, 2012). In comparison to their peers, Mexican American adolescents are at high risk for school dropout (Pew Hispanic Center, 2004) and poor mental health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Thus, Mexican American adolescents who experience family instability may be at even greater risk for negative academic outcomes and poor mental health than their Mexican American peers without this experience. Fourth, studies have yielded inconsistent results in regards to whether Mexican American cultural values are adaptive for development following a risk situation (e.g., Germán, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2009; Hernández, Ramírez García, & Flynn, 2010); understanding how culture is related to adolescent adaptation subsequent to family instability is important because this information may provide guidance for the development of culturally appropriate intervention programs for this population (Dumka, Lopez, & Carter, 2002).

García Coll and colleagues' (1996) integrative model has encouraged researchers to utilize a culturally sensitive approach by examining normative development over time while examining underlying mechanisms and within group variation (e.g., differences among Mexican Americans) instead of between group variation (e.g., differences between Mexican Americans and European Americans). Traditionally, researchers have studied ethnic minority children through a culturally deficient framework, in which minority children were assumed to lack the benefits and advantages of middle-class European Americans resulting in developmental deficiencies. Moreover, studies of Mexican Americans have typically relied on convenience samples that were exclusively low-income, English speaking barrio residents, which did not represent the population well and tended to exaggerate risk levels (Cauce, Coronado, & Watson, 1998; Knight, Roosa, & Umaña-Taylor, 2009).

Consistent with the integrative model, this study prospectively examined underlying processes (mediation and moderation) that may link family instability to Mexican American adolescent development. We examined both family (mother-adolescent conflict) and cultural (adolescent familism values) variables to better understand within group differences in Mexican American adolescent adaptation following family instability. Our sample was diverse in terms of social class, immigration status, cultural beliefs, and type of residential neighborhood, a sample that was very similar to the Census' characterizations of this population (Roosa et al., 2008). Together, this made it more likely that the results would be generalizable to the larger Mexican American population and, therefore, provided a more normative perspective than prior studies.

Family Instability and Adolescent Development

Most research on family instability has examined European American adolescents. For example, Forman and Davies (2003) found that cumulative family instability positively predicted adolescent (M age = 13) externalizing and internalizing symptoms mediated by adolescent appraisals of family insecurity. Similarly, Donahue and colleagues (2010) found that parental divorce/separations that occurred before the age of five increased the odds for the occurrence of a major depression episode between the ages of 13 and 18. They hypothesized this relationship to be mediated by parenting behaviors and subsequent family transitions, but they did not find support for these hypotheses. Using two samples of European American (M age = 15.2) and African American (M age = 13.4) adolescents, Marcnyszyn et al. (2008) learned that cumulative family instability predicted greater internalizing and externalizing problems, fewer positive classroom behaviors, and lower grades in English, math, and science.

More recently, family instability researchers have begun to incorporate samples that better represent the diverse composition of the U.S., often by using the Add Health (1994) data. For example, Brown (2006) found that a transition from a single-mother family or a cohabiting family to a cohabiting stepfamily or married stepfamily (respectively), negatively predicted adolescent school engagement (M age = 15). Cavanaugh, Schiller, and Riegle-Crumb (2006) found that youth (M age = 14) who experienced a greater number of family structure changes were less likely to complete Algebra I in the 9th grade and to graduate from high school and more likely to have depression symptoms. They also examined whether parenting behaviors and adolescent educational aspirations mediated these relationships, but they found no support for this hypothesis (Cavanaugh et al., 2006). Cavanaugh (2008) also learned that a greater number of family structure changes was positively related to adolescent (M age = 15) emotional distress. Lastly, Cavanaugh and Fomby (2012) found that a greater number of family structure changes was negatively related to adolescent (M age = 16.3) completion of high school algebra classes moderated by school academic pressure.

Despite the fact that researchers have operationalized instability differently, these studies have provided empirical evidence that family instability threatens adolescent development. However, only four of these studies included Latinos (i.e., Brown, 2006; Cavanaugh et al., 2006; Cavanaugh, 2008; Cavanaugh & Fomby, 2012) and none examined the impact of instability on Mexican Americans specifically. Also, these four samples were unrepresentative of the larger Latino population because these studies used a data set that oversampled low-income and English speaking Latinos; adolescents who did not speak English (i.e., relatively recent immigrants) were not sampled. Moreover, most of these studies were cross-sectional and only four examined processes that explained the relations between family instability and adolescent development (i.e., Cavanaugh et al., 2006; Cavanaugh & Fomby, 2012; Donahue et al., 2010; Forman & Davies, 2003). Using a diverse sample of Mexican American families, this study prospectively examined the influence of family instability on adolescent academic outcomes and mental health, while examining potential processes that may help explain these relations.

Parent-adolescent Conflict as a Potential Mediator

Research has found that family instability has been associated with decreases in the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship (Ruschena, Prior, Sanson, & Smart, 2005). Although it is normative for adolescents to become more independent, parents remain a significant source of support (McElhaney, Allen, Stephenson, & Hare, 2009) and a decrease in the quality of this relationship may threaten adolescent optimal development. One salient component of this relationship is conflict and research has suggested that increased levels of parent-adolescent conflict occur subsequent to family instability (Ruschena et al., 2005). Because parent-adolescent conflict in a Mexican American family would violate the cultural norm of showing respect to parents (and other adults; Marín & Marín, 1991), conflict could be particularly salient in this population. Although parent-adolescent conflict within Latino families has been reported to be low (Wagner et al., 2010), increased levels have been found to be related to Latino adolescent negative academic outcomes and poor mental health (e.g., Chung, Flook, & Fuligni, 2009; Crean, 2008). Therefore, we hypothesized that mother-adolescent conflict would mediate the relations between family instability and adolescent academic outcomes and mental health.

Exploring Familism as a Moderator

Culture refers to a specific population's beliefs, practices, and traditions (Le et al., 2008; Rogoff, 2003) and it is essential to understand how culture may be related to adolescent adaptation subsequent to family instability. Familism is a value that reflects the importance of family and is commonly characterized by feelings of support and obligation (Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, Marín, & Perez-Stable, 1987). In comparison to their European American peers, research has found that Mexican American adolescents on average reported higher levels of familism values, which were positively linked to their educational aspirations and expectations (Fuligni, Tseng, & Lam, 1999), as well as their emotional well-being (Fuligni & Pederson, 2002). Although some studies have found that adolescent familism values reduced the strength of the relations between risk factors (deviant peer associations and less time spent with parents) and outcomes (deviant peer associations, externalizing problems, and sexual initiation; e.g., Germán et al., 2009; Killoren, Updegraff, & Christopher, 2011; Roosa et al., 2011), a study by Hernández and colleagues (2010) found that adolescent familism values enhanced the strength of the relation between a risk factor (parent-adolescent conflict) and an outcome (threat appraisals). Given this inconsistency, researchers need to disentangle the circumstances in which Mexican American adolescent familism values add protection versus vulnerability following a risk situation. Thus, we explored adolescent familism values as a moderator on the relations between mother-adolescent conflict and adolescent academic outcomes and mental health.

The Current Study

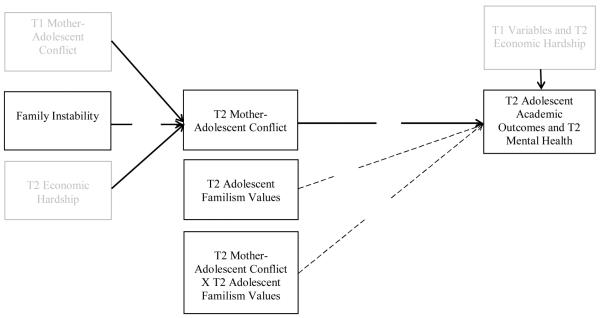

This study addressed several limitations in family instability research by: 1) studying a diverse sample of Mexican Americans to examine within group differences instead of between group differences; 2) prospectively examining families across the transition to junior high; and 3) examining underlying processes that may help explain the relations between family instability and adolescent development. Because research has shown that gender and nativity (U.S. versus Mexico born) may influence adolescent adjustment subsequent to a risk situation (e.g., Killoren, Updegraff, Christopher, & Umaña-Taylor, 2011), we tested the prospective mediational model (Figure 1) for gender and nativity differences. Moreover, because socioeconomic status has been found to be related to academic outcomes and mental health (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002), we included an indicator of socioeconomic status in the model as a control variable. Finally, because not all measures used in this study had been tested for cross language equivalence previously, we tested the full model for differences by language, essentially providing a test for equivalence within the study (Knight et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Prospective family instability theoretical model.

T1 = 5th grade and T2 = 7th grade. Control variables are in grey.

Hypotheses

We hypothesized that family instability, during the transition from elementary to junior high school, would positively predict 7th grade mother-adolescent conflict (while controlling for 5th grade conflict). Next, we hypothesized that mother-adolescent conflict would negatively predict 7th grade academic outcomes (i.e., academic self-efficacy, school attachment, and grades) and positively predict 7th grade externalizing and internalizing symptoms (while controlling for 5th grade outcomes). Next, we hypothesized that mother-adolescent conflict would mediate the relations between family instability and adolescent academic outcomes and mental health. Finally, we explored whether 7th grade adolescent familism values moderated the relations between mother-adolescent conflict and academic outcomes and mental health and whether this moderator buffered or exacerbated the effects of the stressor.

Method

Participants

Data for this study came from a longitudinal study that investigated the impact of culture and context on the adaptation of 749 Mexican American families who resided in a Southwestern metropolitan area (Roosa et al, 2008). Data collection first occurred when adolescents were in the 5th grade (Time 1 [T1]) and again when they were in the 7th grade (Time 2 [T2]). At T2, 710 families were interviewed; 16 refused and 23 could not be located. Attrition analyses indicated no differences on child or mother demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, generational status, and interview language, marital status, age, and education) between families who did (n = 710) and did not participate (n = 39). Only one significant difference emerged; adolescents who did not participate at T2 reported fewer externalizing symptoms at T1 [t (747) = 2.75, p = .01]. The current study focused on 740 adolescents and their mothers; nine families were removed due to foster home placement at T2. Forty-nine percent of adolescents (M age T1= 10.4, SD = .55; M age T2 = 12.8, SD = .45) were female, 83% were interviewed in English, and 70% were born in the U.S. On average, mothers (M age T1 = 35.9, SD = 5.81) had 10.4 years of education, 30% completed interviews in English, and 75% were born in Mexico. At T1, families' median annual household income was between $25,001 and $30,000; the median household income for the state at this time was $50,958 and for Latinos was $39, 976 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008)

Procedure

A complete description of this study's procedures are described elsewhere (Roosa et al., 2008); here we highlighted key components. Purposive and random sampling techniques were used to identify 47 different schools (i.e., public, charter, & religious) representing the diverse neighborhoods in which Mexican American families resided. English and Spanish recruitment packets were sent home with every 5th grade child in all 47 schools. On average, families returned 86% of the forms. Interested families with a Latino surname were contacted for eligibility screening. Eligibility requirements included: child was currently attending school; at least the mother and child agreed to participate; participating mothers and fathers were the child's biological parents; for two-parent families, mother, father, and child were residing in the same household; the mother, father, and child were of Mexican descent; the child was not severely learning disabled; and the child was not participating in a similar study.

Of the 1,025 families that were recruited and eligible for participation, 73% participated (N = 749). Interviewers completed 40 hours of training, were bicultural, and most were bilingual. Computer assisted personal interviews took place at families' homes. Interviewers read and explained the consent and assent forms prior to the interview; they also answered participants' questions in compliance with the University's Institutional Review Board. Family members were interviewed separately in their preferred language (English or Spanish) and on average interviews lasted two and a half hours. Immediately after signing the consent and assent forms, each participating family member was given a cash incentive (T1 = $45; T2 = $50).

Measures

Family background information

Mothers provided information on their marital status, level of education, and family annual household income. Both mothers and adolescents reported on their age, language preference, and nativity.

Family instability

The number of maternal relationship transitions that families experienced from T1 to T2 was assessed with three different pieces of information. First, mothers responded yes or no to the question, “In the past year, have you experienced a divorce or separation?” When they answered yes, they received a family instability score of one. Second, mothers responded yes or no to the question, “Have your living arrangements changed since the last time we interviewed you?” If they answered yes, they indicated how (e.g., divorced at T1 to married at T2). When they answered yes that there was a change in their living arrangements at T2 and the change indicated that the mother either gained or lost a partner (e.g., divorced at T1 to living with a partner but not legally married at T2) they received a score of one. In order to prevent counting the same maternal transition twice, when mothers responded yes that they experienced a divorce or separation and the change in their living arrangements reflected this separation or divorce (e.g., married and living together at T1 to married and not living together at T2), they only received a score of one. When mothers reported that they both gained and lost a partner they received a score of two. Finally, mothers who answered no to both questions received a score of zero. From T1 to T2 nearly 15% of families experienced family instability. That is, 9% (60) of mothers experienced a separation or divorce, 4% (28) a new partner, < 1% (4) became widowed, and 2% (11) experienced both a separation or divorce and a new partner.

Economic hardship

Economic hardship at T2 was used as an indicator of socioeconomic status because a large portion of the mothers in this sample were immigrants and assessments of income are unlikely to be accurate for many immigrants due to irregular work, payments in cash, and no records of income (Roosa, Deng, Nair, & Burrell, 2005). Similarly, the value of a specific level of education to one's economic well-being is different if the education is completed in the U.S. versus Mexico. Mothers rated their levels of economic hardship using 20 items from Conger and Elder's (1994) economic hardship measure. Inability to make ends meet was measured with two items (r = .55; “Think back over the past 3 months and tell us how much difficulty you had with paying your bills” [responses ranged from 1 = a great deal of difficulty to 5 = no difficulty at all, with responses reverse coded]). Having enough money for necessities was measured with seven items (α = .93; “Your family had enough money to afford the kind of home you needed” [responses ranged from 1= not at all true to 5 = very true, with responses reverse coded]). Financial strain was measured with two items (r = .71; “In the next three months, how often do you expect that you and your family will experience bad times such as poor housing or not having enough food?” [responses ranged from 1 = almost never or never to 5 = almost always or always]). Economic cutbacks was measured by nine event count items (“In the last 3 months, has your family changed food shopping or eating habits a lot to save money?” [responses were 1 = yes and 2 = no; 2s were recoded into zeros and 1s were summed to create a count of cutbacks]). Note that Cronbach's alpha is not appropriate for event count scales. A total T2 economic hardship score was computed by standardizing and then summing the scores for each of these measures (α = .81). This scale has been found to be reliable and valid for Mexican American families (e.g., Parke et al., 2004).

Mexican American cultural values

Adolescents rated their familism values with 16 items (T2 α = .85) from the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS; Knight et al., 2010). The current study used the familism values subscales (support and emotional closeness [6 items; “It is important for family members to show their love and affection to one another”], family obligations [5 items; “Children should be taught that it is their duty to care for their parents when their parents get old”], and family as referent [5 items; “Children should always be taught to be good because they represent the family”]) to compute a total adolescent familism values score; responses ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = completely. The authors of this scale have found it to be reliable and valid for Mexican American adolescents.

Mother-adolescent conflict

Adolescents rated conflict with their mothers using the ten item (T1 α = .72; T2 α = .82) Parent Adolescent Conflict Scale (PACS; Ruiz & Gonzales, 1998). The PACS measured minor and serious disagreements (e.g., “How often did you and your mother disagree with each other?”) with responses from 1 = almost never to never to 5 = almost always or always. This scale has been found to be reliable and valid for Mexican American adolescents (e.g., Corona et al., 2012).

Academic self-efficacy

Adolescents rated their academic self-efficacy using an eight item scale (T1 α = .77 [English speakers], .83 [Spanish speakers]; T2 α = .85 [English speakers], .85 [Spanish speakers]) by Arunkumar, Midgley, and Urdan (1999). This scale measured adolescent schoolwork mastery beliefs (e.g., “You can do even the hardest schoolwork if you try”) with responses from 1 = not at all true to 5 = very true.

School attachment

Adolescents rated their school attachment with nine items (T1 α = .64 [English speakers], .63 [Spanish speakers]; T2 α = .77 [English speakers], .70 [Spanish speakers]) derived from three conceptually overlapping measures (Lord, Eccles, & McCarthy, 1994; Smith et al., 1997). This scale measured school attachment (e.g., “You like to do well in school”) with responses from 1 = not at all true to 5 = very true.

Grades

At T1, teachers ranked adolescent academic performance relative to their peers because elementary schools in the study did not have compatible grading methods; responses ranged from 1 = far below average/at the bottom 1/5 of the class to 5 = excellent/the top 1/5 of the class. At T2, both English and math teachers reported on grades (e.g., “If you were giving final grades today, what grade would you give this student for your course?”). Responses ranged from 1 = A to 5 = E/F (reverse scored) and were averaged to compute one grade.

Externalizing and internalizing symptoms

At T1 and T2, mothers and adolescents independently reported on adolescent mental health from the computerized version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). Externalizing symptoms were computed by summing the conduct, attention deficit/hyperactivity, and oppositional defiant disorders symptom counts. Internalizing symptoms were computed by summing the anxiety and mood disorders symptom counts. A combined mother and adolescent DISC scoring algorithm was used to obtain symptom counts with previous work suggesting that that the combined algorithm is a better choice than any single-informant DISC algorithm (Shaffer et al., 2000). This measure has been found to be reliable and valid for Spanish speaking populations (Bravo, Woodbury-Fariña, Canino, & Rubio-Stipec, 1993).

Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted in Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the prospective mediational model (Figure 1). An advantage of SEM is that it simultaneously estimates all paths in a theoretical model while controlling for the influence of all other model variables. We tested for mediation using the percentile bootstrap method and concluded mediational paths to be significant when the 95% confidence limits of the specific indirect effects did not include zero (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). To handle missing data, parameters were estimated using full-information maximum-likelihood (FIML; Enders, 2010). Several fit indices were examined (comparative fit index [CFI], root-mean-square-error of approximation [RMSEA], and standardized root-mean-square residual [SRMR]) to evaluate the model. Good (acceptable) model fit is reflected by a CFI >.95 (.90), RMSEA < .05 (.08), and SRMR < .05 (.08; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). Due to sampling procedures, adolescents were clustered within schools and ignoring clustering can lead to biased estimates (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). To account for both nonnormailty of data and clustering effects, the analysis command COMPLEX with the maximum likelihood restriction estimator (MLR) was used. This analysis is robust against nonnormality and non-independence of observations (Muthén & Muthén, 2010).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Correlations, means, and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. All correlations were in the expected directions; family instability was positively related to T2 mother-adolescent conflict; T2 mother-adolescent conflict was negatively related to academic self-efficacy, school attachment, and grades; T2 mother-adolescent conflict was positively related to T2 externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Kurtosis and skewness values for all study variables were examined and only two variables were out of the recommended range (i.e., family instability and T2 internalizing symptoms).

Table 1.

Correlation matrix, means, and standard deviations for study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family instability | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 2. T2 Economic hardship | .13** | -- | |||||||||||||

| 3. T1 Mother-adol. con. | .08* | −.10* | -- | ||||||||||||

| 4. T2 Mother-adol. con. | .10** | −.02 | .36** | -- | |||||||||||

| 5. T2 Adol. fam. values | .07 | −.02 | −.07 | −.03 | -- | ||||||||||

| 6. T1 Academic self-eff. | .01 | −.09* | .00 | −.03 | .28** | -- | |||||||||

| 7. T2 Academic self-eff. | −.01 | −.09* | −.13** | −.10* | .41** | .40** | -- | ||||||||

| 8. T1 School attachment | −.00 | −.01 | −.10** | −.02 | .11** | .40** | .24** | -- | |||||||

| 9. T2 School attachment | .01 | −.05 | −.11** | −.20** | .25** | .18** | .48** | .33** | -- | ||||||

| 10. T1 Grades | −.05 | −.18** | .00 | .06 | −.06 | .18** | .21** | .16** | .05 | -- | |||||

| 11. T2 Grades | −.06 | .14** | −.04 | −.05 | .01 | .17** | .27** | .15** | .21** | .51** | -- | ||||

| 12. T1 Ext. symptoms | .18** | .06 | .20** | .15** | −.02 | −.17** | −.15** | −.25** | −.16** | .17** | −.25** | -- | |||

| 13. T2 Ext. symptoms | .16** | .09* | .17** | .28** | .14** | −.12** | −.22** | −.18** | −.27** | .10* | −.29** | .54** | -- | ||

| 14. T1 Int. symptoms | .14** | .21** | .19** | .13** | .01 | −.12** | −.10** | −.08* | −.05 | .16** | −.10* | .50** | .25** | -- | |

| 15. T2 Int. symptoms | .18** | .18** | .10* | 24** | −.04 | −.08* | −.13** | −.10** | −.06 | .09* | −.13** | .32** | .53** | .45** | -- |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Sample means | .16 | 0.0 | 2.00 | 2.10 | 4.44 | 4.38 | 4.22 | 4.64 | 4.43 | 3.21 | 3.44 | 5.11 | 5.77 | 16.10 | 13.23 |

| Standard deviations | .41 | 3.18 | .56 | .59 | .40 | .56 | .64 | .42 | .53 | 1.31 | 1.15 | 4.74 | 4.98 | 9.13 | 8.02 |

Note. Sample size ranges from 664 to 740 for variables; T1 = 5th grade; T2 = 7th grade; adol. = adolescent; fam. = familism; con. = conflict; eff. = efficacy; ext. = externalizing; int. = internalizing;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

To test this study's hypotheses, we first tested the basic prospective mediational model (bolded paths in Figure 1). Next, we tested the basic prospective mediational model plus the moderating role of adolescent familism values (bolded and dashed paths in Figure 1). Lastly, we tested this full model to examine whether paths differed by adolescent gender or nativity (all paths in Figure 1).

Prospective Family Instability Mediational Model

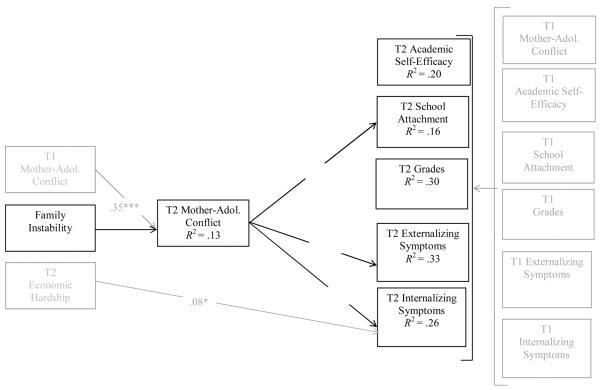

The basic model fit well, χ2 (5, N = 740) = 12.98, p = .02; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .01 (Figure 2). As predicted, several indirect relations between family instability and adolescent outcomes emerged; family instability was positively related to T2 mother-adolescent conflict which in turn, was negatively related to T2 school attachment and positively related to both T2 externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Percentile bootstrapping results indicated that T2 mother-adolescent conflict significantly mediated the relations between family instability and both T2 externalizing (95% CI [.004, .371]) and internalizing symptoms (95% CI [.007, .595]).

Figure 2.

Prospective family instability mediational model.

T1 = 5th grade and T2 = 7th grade. Standardized path coefficients are presented. All lines indicate significant paths where * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Grey boxes indicate control variables. χ2 (5, N = 740) = 12.98, p = .02; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .05; SRMR =.01

Exploration of Moderation

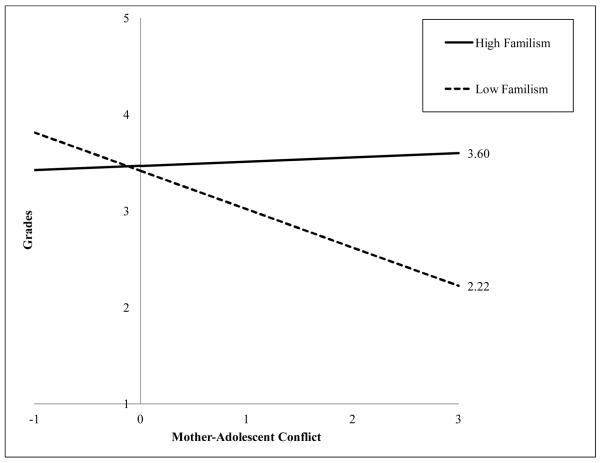

Next, we explored whether T2 adolescent familism values moderated the relations between T2 mother-adolescent conflict and T2 adolescent outcomes. The independent variable (T2 mother-adolescent conflict), moderator (T2 adolescent familism values), and T1 control variables were centered prior to this analysis. The full model fit well, χ2 (5, N = 740) = 12.87, p = .02; CFI = 1.0; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .01; all paths remained the same as in Figure 2. First, it is notable that T2 adolescent familism values were positively related to both T2 academic self-efficacy (β = .33, p < .001) and school attachment (β = .21, p < .001), and negatively related to T2 externalizing symptoms (β = −.14, p < .001). One significant interaction emerged; T2 adolescent familism values moderated the relation between T2 mother-adolescent conflict and T2 grades (β = .08, p < .05). Following procedures recommended by Aiken and West (1991), we probed this interaction by examining simple regression slopes at two levels of the moderator. Because the mean of adolescent familism values was quite high (4.44) and the standard deviation (SD) was low (.40), we examined simple slopes at 1 SD above the mean (high familism) and 2 SDs below the mean (low familism). At high familism, T2 mother-adolescent conflict was unrelated to T2 grades, β = .02, p = .69, but at low familism, T2 mother-adolescent conflict was negatively related to T2 grades, β = −.20, p < .01 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Interaction of adolescent familism values and mother-adolescent conflict on grades in the 7th grade. The range for scores on the X-axis is based on centered values.

Because we examined mediation and found a significant interaction by adolescent familism values, we tested for moderated mediation (see MacKinnon, 2008); that is, whether the mediated effects between family instability and T2 academic outcomes and mental health differed at varying levels of adolescent familism values. Consistent with the way we probed the interaction, we examined mediation at 1 SD above the mean (high familism) and 2 SDs below the mean (low familism). Percentile bootstrapping results indicated that T2 mother-adolescent conflict significantly mediated the relations between family instability and both T2 school attachment and grades at low familism (95% CI [−.070, −.001]), (95% CI [−.105, −.001]), but not at high familism (95% CI [−.030, .001]), (95% CI [−.020, .035]), respectively.

Differences by Gender, Nativity, and Language

Lastly, we tested whether the full prospective mediational model differed by adolescent gender and nativity (U.S. versus Mexico born) by conducting multigroup SEM analyses. First, we estimated an unconstrained model in which all parameters across groups (i.e., gender, nativity, and language) were free. Next, we estimated a constrained model in which all parameters across groups were equal to one another. Next, we conducted log-likelihood difference tests to examine whether the unconstrained and constrained models fit the data differently (when using analysis type command COMPLEX, it is inappropriate to use chi-square difference tests; Muthén & Muthén, 2005). There were no significant differences by gender, Δ χ2 (dfΔ52) = 47.65, p = .65, nativity, Δ χ2 (dfΔ52) = 47.82, p = .64, or language, Δ χ2 (dfΔ52) = 61.21, p = .18. Thus, pathways in our model did not significantly differ by adolescent gender or nativity and further, provided evidence for cross-language equivalence of all measures.

Discussion

Using a diverse sample, this study examined the prospective relations between family instability and Mexican American adolescent development by examining underlying processes that might explain these relations. This study's results add to the empirical evidence that family instability is a risk factor that threatens adolescent development and more specifically, Mexican American adolescents' academic outcomes and mental health. Aligned with previous research (e.g., Ruschena et al., 2005), this study found that family instability during the transition from elementary to junior high school predicted increased mother-adolescent conflict in the 7th grade (T2). Although the standardized regression coefficient for this relation was small (β = .07), this was considered to be meaningful given that we controlled for 5th (T1) grade mother-adolescent conflict and 7th grade economic hardship. Similar to other research (e.g., Chung et al., 2009), this study also found that 7th grade mother-adolescent conflict was related to a decline in 7th grade school attachment and to an increase in 7th grade externalizing and internalizing symptoms. New to this study, the relations between family instability and 5th grade mental health variables were mediated by mother-adolescent conflict. Standardized regression coefficients indicated small to medium effects. Given the standardized path coefficients of the a and b paths in our model, these results suggested that mother-adolescent conflict in the 7th grade explained a small portion of the underlying relations that linked family instability to changes in Mexican American adolescents' mental health. Contrary to what we expected, mother-adolescent conflict was not directly related to academic self-efficacy and grades, although a relationship with grades did emerge when moderation was examined (more below). The strong relationship between academic self-efficacy and school attachment (i.e., collinearity) may have prevented us from obtaining significant relationships from mother-adolescent conflict to both of these variables.

Finally, we found that adolescent familism values in the 7th grade moderated the relation between 7th grade mother-adolescent conflict and grades. Similar to other research findings (e.g., Killoren et al., 2011; Roosa et al., 2011), but contrary to Hernández and colleagues (2010), adolescent familism values acted as a protective factor for the stressor of mother-adolescent conflict. As seen in Figure 3, there was a significant negative relation between mother-adolescent conflict and grades when adolescents reported low familism values, but no relation when adolescents reported high familism values. Research has found that immigrant parents highly value education (Fuligni, 1997) and believe that their children can be most successful in the U.S. by doing well in school and they attempt to instill these educational values in their children (Fuligni & Fuligni, 2007). Because the majority of mothers in this study were born in Mexico, one might speculate that when high levels of mother-adolescent conflict are present, adolescents' strong sense of familial obligation (e.g., attempting to fulfill their mothers' wishes by doing well in school) and family reference (e.g., not wanting to bring shame to their family by doing poorly in school) protected them from the negative influence that mother-adolescent conflict would typically have on their ability to do well in school. Our mediated moderation findings provided some support for this conjecture; mother-adolescent conflict mediated the relations between family instability and school attachment and grades only when familism values were low. It is important to note that adolescent familism values did not moderate the relations between mother-adolescent conflict and academic self-efficacy, school attachment, and externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Similar to other research findings (e.g., Roosa et al., 2011), adolescent familism values were not protective for externalizing symptoms. Interestingly Germán and colleagues (2009) found that familism values were protective for externalizing symptoms in the school context (teacher report), but not in the family context (parental report), which may help explain this pattern in our results. The failure to find significant moderating effects of familism values on the other outcomes may be due to the overlapping relationships among the outcomes particularly internalizing and externalizing symptoms (r = .53). Researchers have only begun to disentangle the complexity of how the Mexican American culture is related to individuals' adaptation; future researchers must continue to study cultural influences on a variety of outcomes within multiple contexts.

Implications

Given that Mexican American adolescents are at a greater risk than their peers for high school dropout (Pew Hispanic Center, 2004) and poor mental health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001), it is especially important that researchers learn of potential modes of intervention in an effort to mitigate and/or prevent the harmful effects that family instability has on these adolescent's development. Because our study found that mother-adolescent conflict during the already stressful transition to junior high school mediated the relations between family instability and negative academic outcomes and poor mental health, this may be one mode of intervention. Engaging in conflict with a parent is a violation of Mexican American adolescents' cultural norms (Marín & Marín, 1991), which may make conflict especially salient in Mexican American families. Our results supported this; although in our study mother-adolescent conflict occurred at low levels (M = 2.10, SD = .59), the relationships of conflict to adolescent negative academic outcomes and poor mental health were significant. Thus, mitigating and/or preventing the negative effects that conflict has on academic outcomes and mental health may be especially important with Mexican American adolescents specifically. Additionally, our study found that subsequent to family instability, high adolescent familism values buffered the negative influence of mother-adolescent conflict on grades and that adolescent familism values were positively related to academic outcomes and negatively related to externalizing symptoms. Thus, encouraging Mexican American families to maintain and/or increase familism values may be a second mode for intervention. Overall, these findings provide some guidance for researchers who are interested in developing culturally appropriate interventions for Mexican American families.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study had several strengths. First, we defined family instability by a sole indicator, maternal relationship transitions, which allowed for a clearer interpretation of the results. Second, in an effort to help explain the relations between family instability and Mexican American adolescent negative academic outcomes and poor mental health, we focused on within-group differences and examined both mediation and moderation in an effort to identify processes that help explain these relationships; our results suggested that mother-adolescent conflict and adolescent familism values offered two potential targets for intervention. Third, we used a prospective design and controlled for 5th grade variables, which suggested that family instability was related to changes in 7th grade mother-adolescent conflict and 7th grade adolescent outcomes. Fourth, we focused on a particularly stressful developmental period, the transition to junior high school, when adolescents may be more vulnerable to additional stressors and still reasonably accessible for interventions. Fifth, in comparison to previous studies, our sample of Mexican American families was diverse, which made it likely that these results may be more generalizable to the larger Mexican American population.

Despite our study's strengths, it was not without limitations. Although we triangulated information in order to thoroughly capture family instability during the transition to junior high school, it is possible that we may have missed some instances. If this were the case, this would suggest that the relations reported in our results most likely were weaker than they would be if all maternal relationship transitions had been captured. The reliability coefficient of the 5th grade school attachment measure was lower than what is generally acceptable (i.e., English speakers = .64; Spanish speakers = .63); however, all correlations between this variable and the other study variables were in the expected directions (Table 1). Lastly, although there are advantages to testing a prospective mediation model (with two data points), we cannot conclude that the relations between variables were causal because more than two data points are needed for that (Cole & Maxwell, 2003).

Future Research and Summary

Future research should study additional variables that may more thoroughly explain the relations between family instability and Mexican American adolescent development. For example, variables such as the quality of parenting, the amount of time adolescents and parents spend together, and/or adolescent cortisol levels may mediate the relations between family instability and adolescent academic outcomes and mental health. Moreover, the quality of adolescents' social support system from extended family members, peers, and/or siblings may moderate the relations between family instability and adolescent academic outcomes and mental health. The better we understand the processes linking family instability to adolescent outcomes, the more options we have for interventions.

In conclusion, our results suggested that for Mexican American adolescents (youth who were already at high risk for negative developmental outcomes) who experienced family instability during the transition from elementary to junior high school (which is often stressful on its own) experienced increased negative academic outcomes and poor mental health in comparison to their Mexican American peers without this experience. Moreover, mother-adolescent conflict and adolescent familism values helped explain the relations between family instability and Mexican American adolescent negative academic outcomes and poor mental health. First, we learned that mother-adolescent conflict mediated the relations between family instability and school attachment (at low familism levels), grades (at low familism levels), externalizing symptoms, and internalizing symptoms. Second, that adolescent familism values moderated the relations between mother-adolescent conflict and grades in a protective fashion. These results underscored the importance of researchers including tests of mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation in their conceptual models. Lastly, the diversity of our sample provided a more normative prospective of Mexican American families, thus making it likely that this study's results will be more generalizable to the larger Mexican American population, as well as more useful in guiding intervention researchers to develop more culturally appropriate interventions for Mexican American families.

Acknowledgment

Work on this paper was supported, in part, by grant MH 68920 (Culture, context, and Mexican American mental health) and the Cowden Fellowship program of the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. The National Institute of Health is not responsible for the content of this paper. The authors are thankful for the support of Nancy Gonzales, Jenn-Yun Tein, Marisela Torres, Jaimee Virgo, Kelly Proulx, the Community Advisory Board, interviewers, and families who participated in the study.

References

- Add Health Add Health. 1994 Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth.

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arunkumar R, Midgley C, Urdan T. Perceiving high or low home-school dissonance: Longitudinal effects on adolescent emotional and academic well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9:441–466. doi:10.1207/s15327795jra0904_4. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo M, Woodbury-Fariña, Canino GJ, Rubio-Stipec M. The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in Puerto Rico. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 1993;17:329–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01380008. doi:10.1007/BF01380008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL. Family structure transitions and adolescent well-being. Demography. 2006;43:447–461. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0021. doi:10.1353/dem.2006.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Coronado N, Watson J. Conceptual, methodological, and statistical issues in culturally competent research. In: Hernandez M, Isaacs M, editors. Promoting Cultural Competence in Children's Mental Health Services. Paul H. Brookes; Baltimore, MD: 1998. pp. 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh SE. Family structure history and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:944–980. doi:10.1177/0192513X07311232. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh SE, Fomby P. Family instability, school context, and the academic careers of adolescents. Sociology of Education. 2012;85:81–97. doi:10.1177/0038040711427312. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh SE, Schiller KS, Riegle-Crumb C. Marital transitions, parenting, and schooling: Exploring the link between family-structure history and adolescents' academic status. American Sociological Association. 2006;79:329–354. doi: 10.1177/003804070607900403. doi:10.1177/003804070607900403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung GH, Flook A, Fuligni AJ. Daily family conflict and emotional distress among adolescents from Latin America, Asian, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1406–1415. doi: 10.1037/a0014163. doi:10.1037/a0014163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr. Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. 1st ed. Aldine De Gruyter; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Corona M, McCarty C, Cauce AM, Robins RW, Widaman KF, Conger RD. The relation between maternal and child depression in Mexican American families. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2012;34:539–556. doi: 10.1177/0739986312455160. doi:10.1177/0739986312455160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crean HF. Conflict in the Latino parent-youth dyad: The role of emotional support from the opposite parent. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:484–493. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.484. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue KL, D'Onofrio BM, Bates JE, Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. Early exposure to parents' relationship instability: Implications for sexual behavior and depression in adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.004. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Lopez VA, Jacobs Carter S. Parenting interventions adapted for Latino families: Progress and prospects. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States. Greenwood; Westport, CT: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Roeser RW. Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Third edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2009. pp. 404–434. [Google Scholar]

- Enders C. Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Davies PT. Family instability and young adolescent maladjustment: The mediating effects of parenting quality and adolescent appraisals of family security. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:94–105. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_09. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. The academic achievement of adolescents from immigrant families: The role of family background, attitudes, and behavior. Child Development. 1997;68:351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Fuligni AS. Immigrant families and the educational development of their children. In: Lansford J, Deater Deckard K, Bornstein M, editors. Immigrant families in America. Guilford Publications, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Pederson S. Family obligation and the transition to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:856–868. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.856. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00075. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, García HV, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germán M, Gonzales NA, Dumka L. Familism values as a protective factor for Mexican-origin adolescents exposed to deviant peers. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:16–42. doi: 10.1177/0272431608324475. doi:10.1177/0272431608324475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández B, Ramírez García JI, Flynn M. The role of familism in the relation between parent-child discord and psychological distress among emerging adults of Mexican descent. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:105–114. doi: 10.1037/a0019140. doi:10.1037/a0019140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Killoren SE, Updegraff KA, Christopher FS. Family and cultural correlates of Mexican-origin youths' sexual intentions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:707–718. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9587-5. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9587-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killoren SE, Updegraff KA, Christopher FS, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Mothers, fathers, peers, and Mexican-origin adolescents' sexual intentions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:209–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00799.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural values scales for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. doi:10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Studying ethnic minority and economically disadvantaged populations: Methodological challenges and best practices. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Le H, Ceballo R, Chao R, Hill NE, Murry VM, Pinderhughes EE. Excavating culture: Disentangling ethnic differences from contextual influences in parenting. Applied Developmental Science. 2008;12:163–175. doi: 10.1080/10888690802387880. doi:10.1080/10888690802387880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord S, Eccles J, McCarthy K. Surviving the junior high school transition: Family processes and self-perceptions as protective and risk factors. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:162–199. doi:10.1177/027243169401400205. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:1–24. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcynszyn LA, Evans GE, Eckenrode J. Family instability during early and middle adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29:380–392. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2008.06.001. [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Marín BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney KB, Allen JP, Stephenson C, Hare AL. Attachment and autonomy during adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Third edition John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2009. pp. 358–403. [Google Scholar]

- Motel S, Patten E. The 10 Largest Hispanic Origin Groups: Characteristics, Rankings, Top Counties. Pew Research Center: Pew Hispanic Center; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2012/06/The-10-Largest-Hispanic-Origin-Groups.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. Muthén and Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998 –2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, French S, Widaman K. Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development. 2004;75:1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Hispanic Center Latino teens staying in high school: A challenge for all generations. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Fact_Sheets/Hispanics_in_America/pew_hispanic_education_fact_sheet_persistence.pdf.

- Rogoff B. The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Deng S, Nair R, Burrell GL. Measures for studying poverty in family and child research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:971–988. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00188.x. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Liu FF, Torres M, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Saenz D. Sampling and recruitment in studies of cultural influences on adjustment: A case study with Mexican Americans. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Zeiders KH, Knight GP, Gonzalez NA, Tein J, Saenz D, O'Donnell M, Berkel C. A test of the Social Development Model during the transition to junior high with Mexican American adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0021269. doi: 10.1037/a0021269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz SY, Gonzales NA. Multicultural, multidimensional assessment of parent–adolescent conflict. Poster presented at the Seventh Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence; San Diego, CA. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ruschena E, Prior M, Sanson A, Smart D. A longitudinal study of adolescent adjustment following family transitions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:353–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00369.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal, Marín BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn't? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. doi:10.1177/07399863870094003. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Lambert LE, Allen L, Aber JL. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:166–193. doi:10.1177/0272431603023002003. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV: Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. doi:10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RG, Burgeson R, Carlton-Ford, Blyth DA. The impact of cumulative change in early adolescence. Child Development. 1987;58:1220–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01453.x. doi:10.2307/1130616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Connell CM, Wright G, Sizer M, Norman JM, Hurley A, Walker SN. An ecological model of home, school, and community partnerships: Implications for research and practice. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation. 1997;8:339–360. doi:10.1207/s1532768xjepc0804_2. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey. American fact finder: Median household income in the past 12 months. 2008 Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KD, Ritt-Olson A, Chou C, Pokhrel P, Duan L, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Soto DW, Unger JB. Associations between family structure, family functioning, and substance use among Hispanic/Latino adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:98–108. doi: 10.1037/a0018497. doi:10.1037/a0018497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]