This paper describes a method to prepare RNAs with homogeneous ends for structural studies. The method uses the CRISPR-based strategy.

Keywords: affinity purification of RNA, ARiBo tag, CRISPR tag, T7 RNA polymerase, 5′ heterogeneity, Cse3 endoribonuclease

Abstract

Affinity purification of RNA using the ARiBo tag technology currently provides an ideal approach to quickly prepare RNA with 3′ homogeneity. Here, we explored strategies to also ensure 5′ homogeneity of affinity-purified RNAs. First, we systematically investigated the effect of starting nucleotides on the 5′ heterogeneity of a small SLI RNA substrate from the Neurospora VS ribozyme purified from an SLI-ARiBo precursor. A series of 32 SLI RNA sequences with variations in the +1 to +3 region was produced from two T7 promoters (class III consensus and class II ϕ2.5) using either the wild-type T7 RNA polymerase or the P266L mutant. Although the P266L mutant helps decrease the levels of 5′-sequence heterogeneity in several cases, significant levels of 5′ heterogeneity (≥1.5%) remain for transcripts starting with GGG, GAG, GCG, GGC, AGG, AGA, AAA, ACA, AUA, AAC, ACC, AUC, and AAU. To provide a more general approach to purifying RNA with 5′ homogeneity, we tested the suitability of using a small CRISPR RNA stem–loop at the 5′ end of the SLI-ARiBo RNA. Interestingly, we found that complete cleavage of the 5′-CRISPR tag with the Cse3 endoribonuclease can be achieved quickly from CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo transcripts. With this procedure, it is possible to generate SLI-ARiBo RNAs starting with any of the four standard nucleotides (G, C, A, or U) involved in either a single- or a double-stranded structure. Moreover, the 5′-CRISPR-based strategy can be combined with affinity purification using the 3′-ARiBo tag for quick purification of RNA with both 5′ and 3′ homogeneity.

INTRODUCTION

In vitro synthesis of RNA has become an indispensable tool for biological sciences. This is most commonly achieved via transcription with bacteriophage RNA polymerases like T7, T3, and SP6 (Chamberlin and Ryan 1982; Melton et al. 1984; Milligan et al. 1987; Krupp 1988), which allow specific promoter-dependent transcription of diverse RNA sequences. In vitro transcription with the T7 RNA polymerase is particularly widespread since it can produce milligram quantities of RNAs for a variety of in vitro and in vivo applications.

Although the T7 RNA polymerase (T7 RNAP) accurately transcribes most sequences starting with a purine (Dunn and Studier 1983; Milligan et al. 1987; Imburgio et al. 2000), it often produces transcripts with heterogeneous 5′ and 3′ ends. The T7 RNAP uses an 18-nucleotide (nt) double-stranded promoter to initiate transcription and then transcribes a single- or double-stranded DNA template until the end of the complementary DNA strand is reached (Milligan et al. 1987; Krupp 1988). The T7 RNAP may terminate prematurely but often adds a few extra bases at the 3′ end that are not encoded by the template (Milligan et al. 1987; Krupp 1988; Martin et al. 1988) and, in certain cases, may produce RNAs that are much longer than expected (Cazenave and Uhlenbeck 1994). In addition, transcriptions from the G-initiating T7 class III consensus promoter (residues −17 to +1) (Chamberlin and Ryan 1982) can yield 5′-sequence heterogeneity, particularly for sequences starting with GGG (Martin et al. 1988; Cunningham et al. 1991; Pleiss et al. 1998; Imburgio et al. 2000; Sherlin et al. 2001) and GAG (Ferré-D’Amaré and Doudna 1996). 5′-Sequence heterogeneity is also observed when the +1 G nucleotide is substituted by A, U, or C (Cunningham et al. 1991; Helm et al. 1999; Imburgio et al. 2000). It was reported that RNA sequences transcribed from the A-initiating T7 class II φ2.5 promoter have superior 5′-sequence homogeneity (Coleman et al. 2004). However, this promoter has not been extensively exploited for in vitro synthesis of RNA (Milligan et al. 1987; Cunningham et al. 1991; Imburgio et al. 2000).

To help produce RNA with homogeneous ends, one may rely on existing solutions. Incorporation of 2′-methoxyls in the first two 5′ nucleotides of the complementary DNA strand can help reduce 3′ heterogeneity (Kao et al. 1999; Sherlin et al. 2001). Furthermore, purification by denaturing gel electrophoresis can be used for size fractionation of RNAs with nucleotide resolution (Milligan et al. 1987; Wyatt et al. 1991; Doudna 1997). However, this approach is only useful for small RNAs (<30–50 bases) and will likely not separate RNAs of similar size with both 5′ and 3′ heterogeneity. Endoribonuclease processing of an RNA precursor represents a more general solution to producing an RNA target with homogeneous ends. Many endonucleases with minimal sequence requirements have been exploited, including RNase H (Lapham and Crothers 1996), DNAzymes (Santoro and Joyce 1997), and ribozymes (Dzianott and Bujarski 1988; Grosshans and Cech 1991; Taira et al. 1991; Price et al. 1995; Ferré-D’Amaré and Doudna 1996; Schürer et al. 2002; Walker et al. 2003; Kieft and Batey 2004; Batey and Kieft 2007; Pereira et al. 2010; Nelissen et al. 2012). Ribozymes are particularly convenient because they can be added in cis or cotranscribed to achieve RNA cleavage during transcription. For example, the well-characterized hammerhead ribozyme has been used for 5′ and 3′ cleavage of RNA transcripts (Dzianott and Bujarski 1988; Grosshans and Cech 1991; Taira et al. 1991; Price et al. 1995; Ferré-D’Amaré and Doudna 1996; Walker et al. 2003). However, its cleavage requires base-pairing between ribozyme residues and the RNA target, such that it may be incomplete in cases in which the RNA target structure competes with the folding of the active ribozyme (Grosshans and Cech 1991; Price et al. 1995; Walker et al. 2003). Moreover, it may be cumbersome in such cases to find ideal ribozyme sequence and cleavage conditions (Walker et al. 2003). Thus, endoribonucleases that do not rely on structural reorganization of the target RNA present a distinct advantage for trimming the ends of RNA transcripts. For example, the VS, HDV, and glmS ribozymes have little sequence or structure requirements 5′ of the cleavage site and can be incorporated at the 3′ end of an RNA to ensure its 3′-sequence homogeneity (Ferré-D’Amaré and Doudna 1996; Kieft and Batey 2004; Batey and Kieft 2007; Di Tomasso et al. 2011). We are unaware of an equivalent ribozyme (or DNAzyme) with minimal sequence and structure requirements 3′ of the cleavage site that has been used to achieve 5′-sequence homogeneity. RNase H cleavage can fulfill these criteria, but it requires a long incubation with chemically modified oligonucleotides that makes it less practical (Lapham and Crothers 1996).

Several recently discovered Cas endoribonucleases display minimal sequence requirement 3′ of the cleavage site and have potential as biochemical tools for generating RNA with 5′ homogeneity (Brouns et al. 2008; Haurwitz et al. 2010; Gesner et al. 2011; Sashital et al. 2011; Garside et al. 2012). Cas endoribonucleases specifically cleave at cognate CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) RNA sequences found in prokaryotes as part of an adaptive immune system against bacteriophages and plasmids (for recent reviews, see Horvath and Barrangou 2010; Karginov and Hannon 2010; Marraffini and Sontheimer 2010; Al-Attar et al. 2011; Makarova et al. 2011; Terns and Terns 2011; Wiedenheft et al. 2012). The CRISPR RNA sequences often comprise small stable RNA hairpins that are specifically cleaved at the 3′ end of the stem by the Cas (CRISPR-associated) endoribonuclease. For example, Cse3, the Cas endoribonuclease from Thermus thermophilus, binds a 21-nt RNA hairpin and cleaves directly after G21 (Brouns et al. 2008; Gesner et al. 2011; Sashital et al. 2011).

Recently, we reported a quick procedure for affinity batch purification of in vitro–transcribed RNA using a 3′-ARiBo tag (Di Tomasso et al. 2011, 2012a) composed of an activatable ribozyme, the glmS ribozyme, and the λBoxB RNA. The λboxB RNA allows immobilization on glutathione-Sepharose (GSH-Sepharose) resin via a λN-GST fusion protein, whereas the glmS ribozyme is activated with glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) for RNA elution. This procedure yields RNA of high purity and ensures 3′-sequence homogeneity. However, it does not guarantee 5′-sequence homogeneity, which is important for several applications, particularly when the identity of the starting residue is critical. To ensure the 5′ homogeneity of affinity-purified RNAs, we investigated the effect of starting nucleotides on the 5′ heterogeneity of a small SLI RNA substrate derived from the Neurospora VS ribozyme and purified by affinity from an SLI-ARiBo precursor. We also examined the potential of incorporating a small CRISPR tag at the 5′ end of SLI-ARiBo RNAs to achieve 5′ homogeneity using the T. thermophilus Cse3 endoribonuclease. As detailed below, RNA sequence selection can help ensure 5′ homogeneity, but the use of the Cse3/CRISPR system provides a more general approach to purifying RNA with 5′ homogeneity.

RESULTS

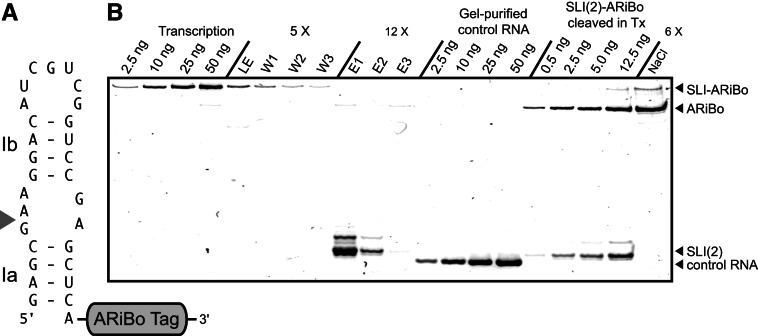

Evidence for 5′ heterogeneity of an affinity-purified T7 transcript starting with GAG

As part of our structural and functional studies of the Neurospora VS ribozyme, we have prepared several variants of its SLI RNA hairpin substrate (Hoffmann et al. 2003; Bouchard et al. 2008; Lacroix-Labonte et al. 2012) by in vitro transcription with T7 RNAP followed by purification with gel electrophoresis. Given that gel purification is a tedious and long procedure, we were interested in speeding up the process using batch affinity purification with an ARiBo tag (Di Tomasso et al. 2011, 2012a). The first SLI RNA tested was SLI(2) (Fig. 1A), which starts with the GAG sequence. SLI(2) was synthesized with a 3′-ARiBo tag and affinity-purified on a λN+-L+-GST/GSH-Sepharose matrix (Fig. 1B). The ARiBo tag sequence used here (ARiBo4) (Supplemental Fig. S1) is slightly different from our original ARiBo1 tag (Di Tomasso et al. 2011) in that the glmS ribozyme sequence was modified to help reduce misfolding and improve GlcN6P-induced cleavage of ARiBo-fusion RNAs. Using this ARiBo tag, the SLI RNA of the correct size was successfully detected in the elution fractions. Analysis by denaturating gel electrophoresis demonstrated that this SLI RNA is highly pure with respect to the most likely contaminant, the ARiBo tag. However, there are a few low-intensity bands close to the predominant (most intense) band on the gel (Fig. 1B, lane E1) that represents ∼15% heterogeneity within the population of purified SLI RNA. This level of heterogeneity is too high for biophysical and structural investigations; thus, we sought to investigate the effect of starting nucleotides on the heterogeneity of T7 transcripts.

FIGURE 1.

Evidence of 5′ heterogeneity revealed from affinity purification of an SLI RNA transcribed from an SLI-ARiBo precursor. (A) Schematic representation of SLI(2)-ARiBo fusion RNA. (Gray arrowhead) Points to the VS ribozyme cleavage site in the internal loop between Stems Ia and Ib. (B) Small-scale affinity batch purification of SLI(2) analyzed on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel stained with SYBR Gold. The SLI(2) RNA was transcribed as an ARiBo-fusion RNA [SLI(2)-ARiBo] and purified by affinity. Aliquots from each purification step were loaded on the gel [(LE) load eluate; (W1–3) washes; (E1–3) elutions; and (NaCl) matrix regeneration with 2.5 M NaCl] in the amounts shown, where 1× correspond to ∼50 ng of SLI(2)-ARiBo precursor present in the transcription reaction or the equivalent of 8.23 ng of SLI(2) to be purified. In addition, standard quantities of SLI(2)-ARiBo from the transcription reaction, gel-purified control RNA (29 nt), and SLI(2) cleaved in the transcription reaction were loaded as controls. Bands corresponding to the SLI(2)-ARiBo (176 nt), the ARiBo tag (147 nt), and SLI(2) (29 nt) RNAs are indicated on the right side of the gel.

5′ heterogeneity of T7 transcripts synthesized from the G-initiating T7 class III promoter

To investigate the effect of the first nucleotides on the 5′ heterogeneity of T7 transcripts, we affinity-purified a given RNA in which we systematically modified the first few nucleotides. The SLI hairpin substrate derived from the VS ribozyme serves as an ideal model for these studies (Fig. 1A) because its small size (29 nt) facilitates detection of 5′ and 3′ heterogeneities on denaturing gels. Furthermore, SLI can be cleaved by the VS ribozyme to yield products (Fig. 1A) that can be analyzed on denaturing gels to pinpoint the source (e.g., 5′ or 3′) of heterogeneity.

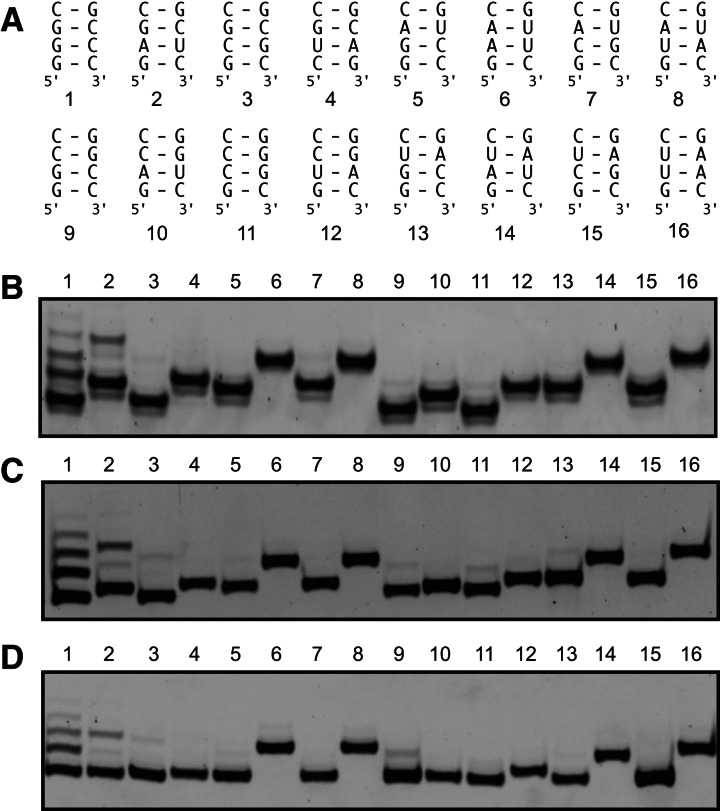

In addition to the SLI(2) RNA that starts with GAG, other SLI RNA hairpins with sequence variations of nucleotides +2/+3 [SLI(1) to SLI(16)] (Fig. 2A) were synthesized with a 3′-ARiBo tag from the G-initiating T7 class III promoter using the wild-type T7 RNAP. These SLI RNAs also incorporate sequence variations of nucleotides +26/+27 to maintain Watson–Crick base-pairing in Stem Ia (Figs. 1A, 2A). The SLI RNAs were affinity-purified, and the eluted fractions were separated on denaturing gels (Fig. 2B). The gel conditions are not fully denaturing because gels were run at low voltage to increase resolution; thus, the mobility of the predominant band varies from one SLI sequence to the other; those with a higher content of G-C base pairs in Stem Ia systematically migrate faster, as previously observed (Lehrach et al. 1977; Frank and Köster 1979). For some SLI RNAs, there are, in addition to the most intense band, lower-intensity bands indicative of transcriptional heterogeneity (see, for example, lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 2B). This heterogeneity likely originates from the 5′ end, since glmS ribozyme cleavage should ensure 3′ homogeneity of the purified RNA. Nevertheless, we confirmed the absence of 3′ heterogeneity by performing VS ribozyme cleavage of the 16 SLI RNAs prior to elution. The VS ribozyme cleaves SLI RNAs between G5 and A6, such that a short 5′ product is released during the VS cleavage step and a 24-nt 3′ product is eluted along with the 29-nt substrate following activation of glmS cleavage. In contrast with several SLI RNA substrates, all 24-nt 3′ products migrate as single homogeneous bands on a denaturing gel (Supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of the 5′ sequence on the heterogeneity of SLI RNAs transcribed as SLI-ARiBo precursors from the consensus T7 class III promoter. (A) Sequence of Stem Ia and numbering of SLI RNAs with different 5′ (and 3′) sequences. (B) Small-scale affinity batch purifications of each of the 16 SLI RNAs transcribed as SLI-ARiBo precursors from the T7 class III promoter using the wild-type T7 RNAP and analyzed on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel stained with SYBR Gold. Only the E1 elution fractions are shown, and from the 400-μL elution volumes, 1.2-μL aliquots were loaded on the gel. (C,D) Small-scale affinity batch purifications of each of the 16 SLI RNAs transcribed as SLI-ARiBo RNAs from the T7 class III promoter using the wild-type (C) or P266L mutant (D) T7 RNAP. These E1 elution fractions were treated with calf alkaline phosphatase to remove phosphate heterogeneity at the 5′ end (in C and D only). From the 50-μL phosphatase reaction mixture, 6.3-μL aliquots were analyzed on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels stained with SYBR Gold. In B–D, gel lanes match the SLI numbering given in A.

To verify that the observed heterogeneity is not due to a partially dephosphorylated 5′-triphosphate group, affinity purifications were also performed in which the E1 elution fractions were treated with calf alkaline phosphatase. For most SLI RNAs, this phosphatase treatment reduced the number of low-intensity bands on the gel (Fig. 2, cf. B and C). Interestingly, after alkaline phosphatase treatment, very few RNAs display low-intensity bands.

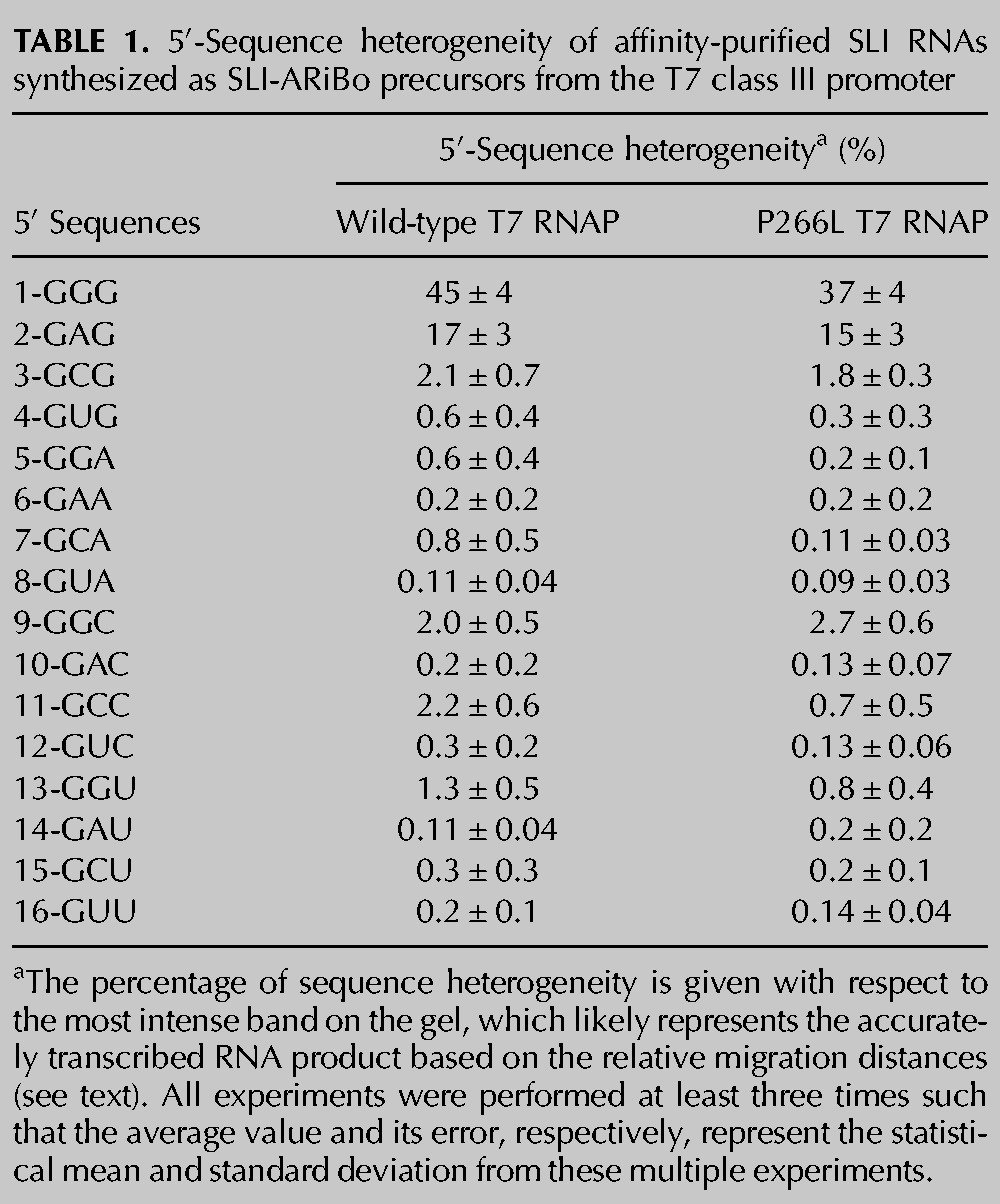

Affinity purifications with alkaline phosphatase treatment were performed at least three times to determine average percentages of heterogeneity with experimental errors (Table 1). As previously reported (Pleiss et al. 1998; Coleman et al. 2004), a high percentage of heterogeneity is detected for transcripts starting with the GGG or GAG sequences, respectively, 45% and 17%. We also find lower but significant levels of 5′-sequence heterogeneity (1.5%–3%) for SLI RNAs starting with the GCG, GGC, and GCC sequences. However, no significant heterogeneity (<1.5%) is observed for SLI RNAs (11 out of 16) starting with GUG, GGA, GAA, GCA, GUA, GAC, GUC, GGU, GAU, GCU, or GUU.

TABLE 1.

5′-Sequence heterogeneity of affinity-purified SLI RNAs synthesized as SLI-ARiBo precursors from the T7 class III promoter

The T7 RNAP mutant P266L is known to greatly reduce the relative levels of abortive transcripts in favor of run-off transcription (Guillerez et al. 2005; Ramírez-Tapia and Martin 2012), and we reasoned that it could also help reduce levels of 5′ heterogeneity. Thus, SLI-ARiBo RNAs were also synthesized using the P266L mutant, and the SLI RNAs were affinity-purified with alkaline phosphatase treatment. For these G-initiating transcripts, the P266L mutant produces similar levels of 5′-sequence heterogeneity compared with the wild-type polymerase (Fig. 2D; Table 1), with a significant reduction only for the SLI(11) RNA that starts with GCC (from 2.2% ± 0.6% to 0.7% ± 0.5%).

5′ heterogeneity of T7 transcripts synthesized from the A-initiating class II ϕ2.5 promoter

The T7 class II φ2.5 promoter allows synthesis of RNA sequences that start with an adenine. It has not been widely used, most likely because T7 class II promoters are considered weaker promoters both in vitro and in vivo (Chamberlin and Ryan 1982; Dunn and Studier 1983; Milligan et al. 1987; Imburgio et al. 2000 and references therein). However, it was shown that similar RNA yields can be obtained in vitro when using the T7 class II φ2.5 and class III promoters, and that the class II φ2.5 promoter can produce RNA with significantly less 5′ heterogeneity (Coleman et al. 2004). Given that only a few sequences were tested, we were interested in systematically investigating 5′-sequence heterogeneity originating from this promoter.

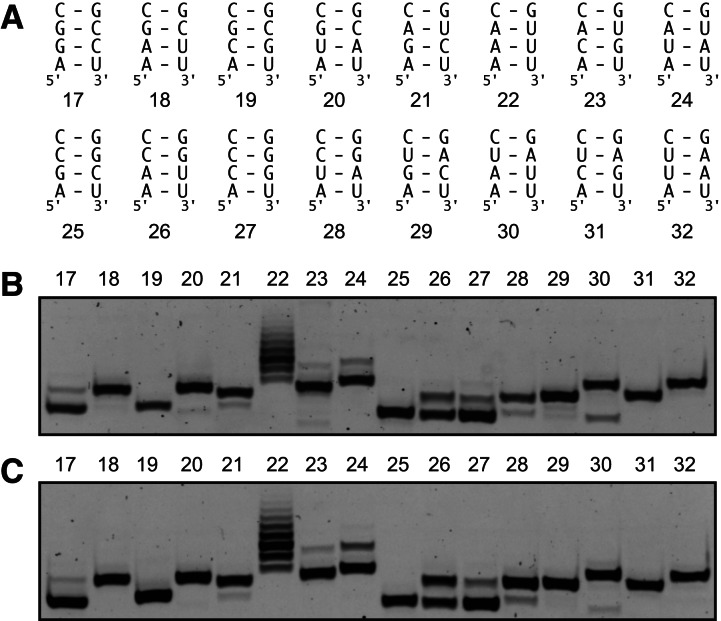

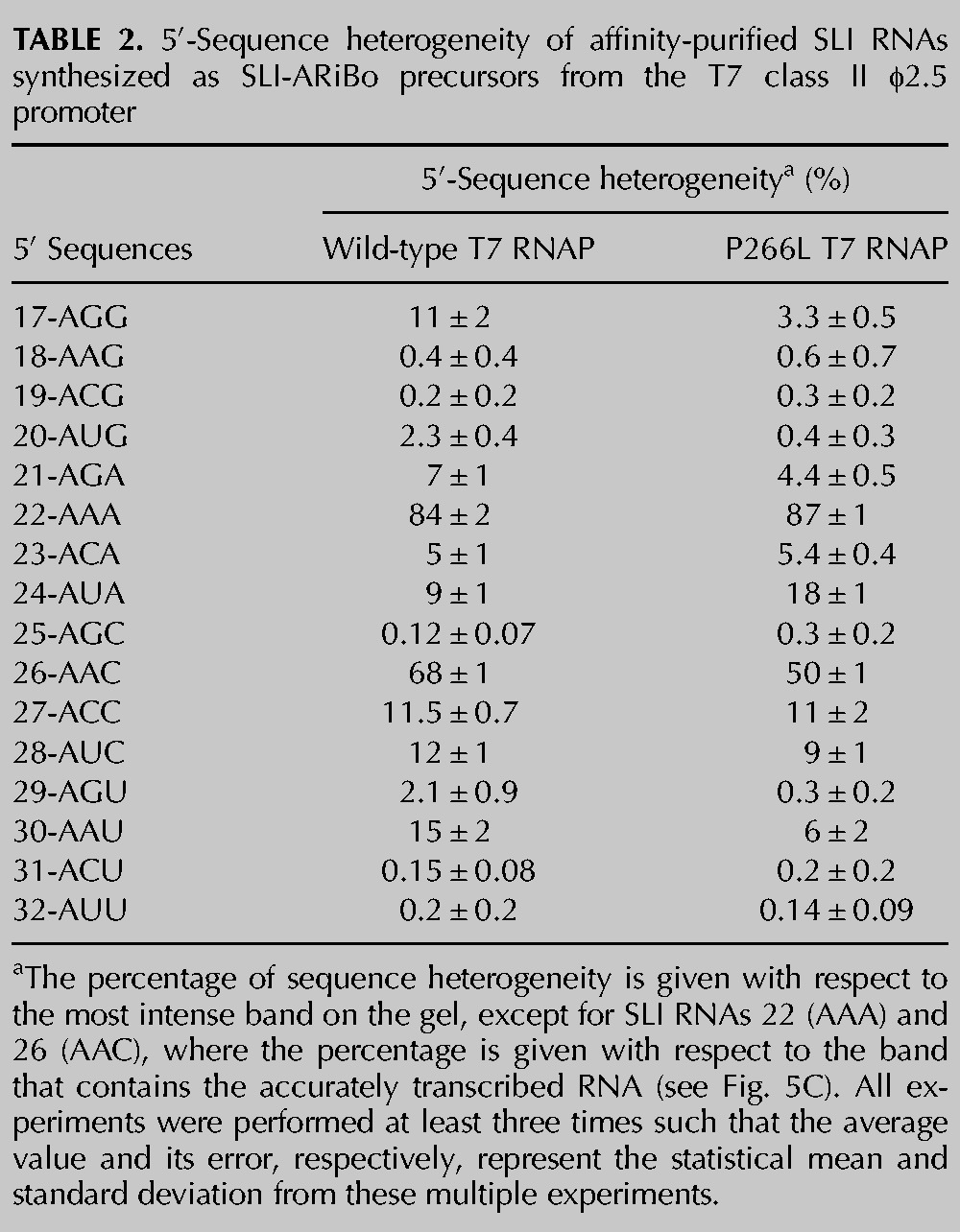

SLI RNA hairpins with sequence variations of the +2/+3 nucleotides [SLI(17) to SLI(32)] (Fig. 3A) were synthesized with a 3′-ARiBo tag from the A-initiating T7 class II φ2.5 promoter using the wild-type T7 RNAP. After affinity purification, the eluted fractions were treated with alkaline phosphatase and analyzed by denaturing gels (Fig. 3B; Table 2). In contrast to our observations with the class III promoter, many RNAs synthesized from the class II φ2.5 promoter display a high percentage (≥5%) of 5′-sequence heterogeneity, namely, those starting with AGG, AGA, AAA, ACA, AUA, AAC, ACC, AUC, and AAU. The percentage of heterogeneity of SLI(17) starting with AGG (11% ± 2%) is somewhat higher but similar to what has been previously reported for transcripts starting with AGG (6% ± 2%) (Coleman et al. 2004). Consistent with a prior study (Cunningham et al. 1991), transcripts starting with AAA (84% ± 2%) and AAC (68% ± 1%) are so heterogeneous that the most intense RNA band does not represent the expected RNA product (see below), contrary to what is generally assumed. Notably, the highest percentages of heterogeneity obtained for the class II φ2.5 and class III promoters are with the AAA- and GGG-initiating transcripts, respectively, suggesting that this heterogeneity arises from similar mechanisms, likely slippage within an unstable initiation complex and/or priming of abortive initiation products (Martin et al. 1988; Cunningham et al. 1991; Moroney and Piccirilli 1991; Pleiss et al. 1998). Lower but still significant levels of heterogeneity (1.5%–3%) are observed for SLI transcripts starting with AUG and AGU, whereas no significant heterogeneity (<1.5%) is observed for those starting with AAG, ACG, AGC, ACU, and AUU. In contrast to a prior study (Coleman et al. 2004), our systematic investigation demonstrates that the class III promoter generally produces transcripts with superior 5′ homogeneity compared with the class II φ2.5 promoter when using the wild-type T7 RNAP.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of the 5′ sequence on the heterogeneity of SLI RNAs transcribed as SLI-ARiBo precursors from the T7 class II φ2.5 promoter. (A) Sequence of Stem Ia and numbering of SLI RNAs with different 5′ (and 3′) sequences. (B,C) Small-scale affinity batch purifications of each of the 16 SLI RNAs transcribed as SLI-ARiBo RNAs from the T7 class II φ2.5 promoter using the wild-type (B) or P266L mutant (C) T7 RNAP. The E1 elution fractions were treated with calf alkaline phosphatase to remove phosphate heterogeneity at the 5′ end. From the 50-μL phosphatase reaction mixture, 6.3-μL aliquots were analyzed on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels stained with SYBR Gold. In B and C, gel lanes match the SLI numbering given in A.

TABLE 2.

5′-Sequence heterogeneity of affinity-purified SLI RNAs synthesized as SLI-ARiBo precursors from the T7 class II φ2.5 promoter

Although the P266L mutant has little effect on 5′-sequence heterogeneity for transcripts synthesized from the class III promoter, it does have a significant effect on several transcripts synthesized from the class II φ2.5 promoter (Fig. 3C; Table 2). Significant reductions in 5′ heterogeneity are observed with P266L for transcripts starting with AGG (from 11% ± 2% to 3.3% ± 0.5%), AUG (from 2.3% ± 0.4% to 0.4% ± 0.3%), AGA (from 7% ± 1% to 4.4% ± 0.5%), AAC (from 68% ± 1% to 50% ± 1%), AUC (from 12% ± 1% to 9% ± 1%), AGU (from 2.1% ± 0.9% to 0.3% ± 0.2%) and AAU (from 15% ± 2% to 6% ± 2%). In contrast, a significant increase in heterogeneity is observed for the transcript starting with AUA (from 9% ± 1% to 18% ± 1%, assuming that the most intense band represents the accurately transcribed RNA). Nevertheless, the P266L mutant generally helps reduce the level of 5′ heterogeneity for A-initiating transcripts. Compared with the wild-type T7 RNAP, it reduces the level of 5′ heterogeneity to insignificant levels for transcripts starting with AUG and AGU, such that it increases the pool of A-initiating transcripts that can be synthesized with 5′ homogeneity from five to seven out of the 16 tested sequences, namely, those starting with AAG, ACG, AUG, AGC, AGU, ACU, and AUU.

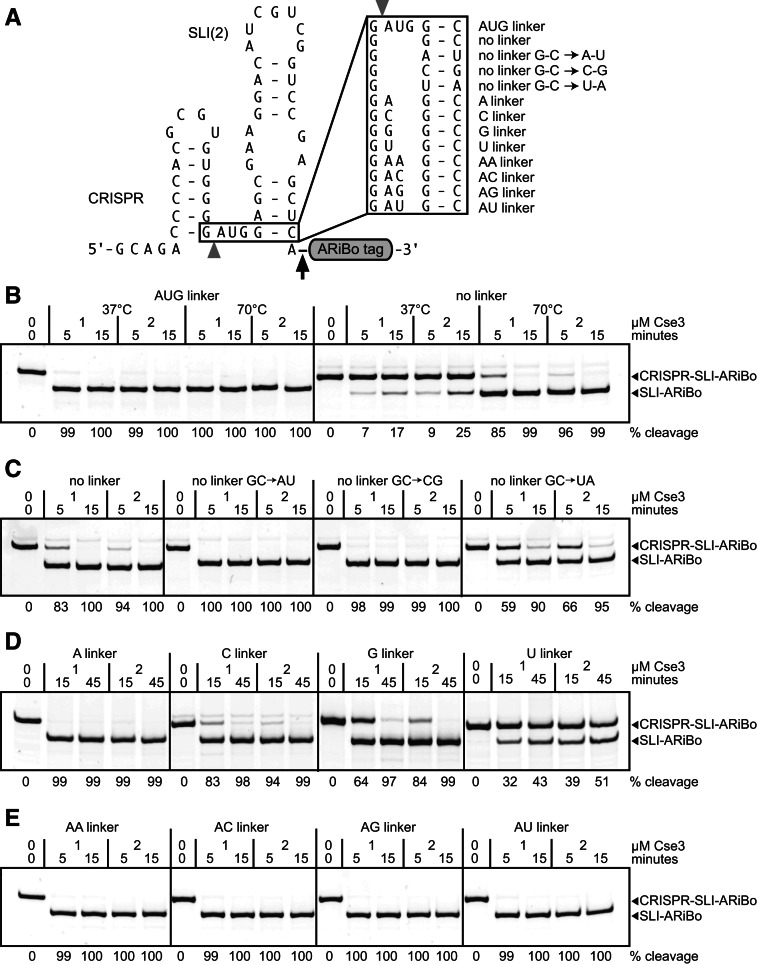

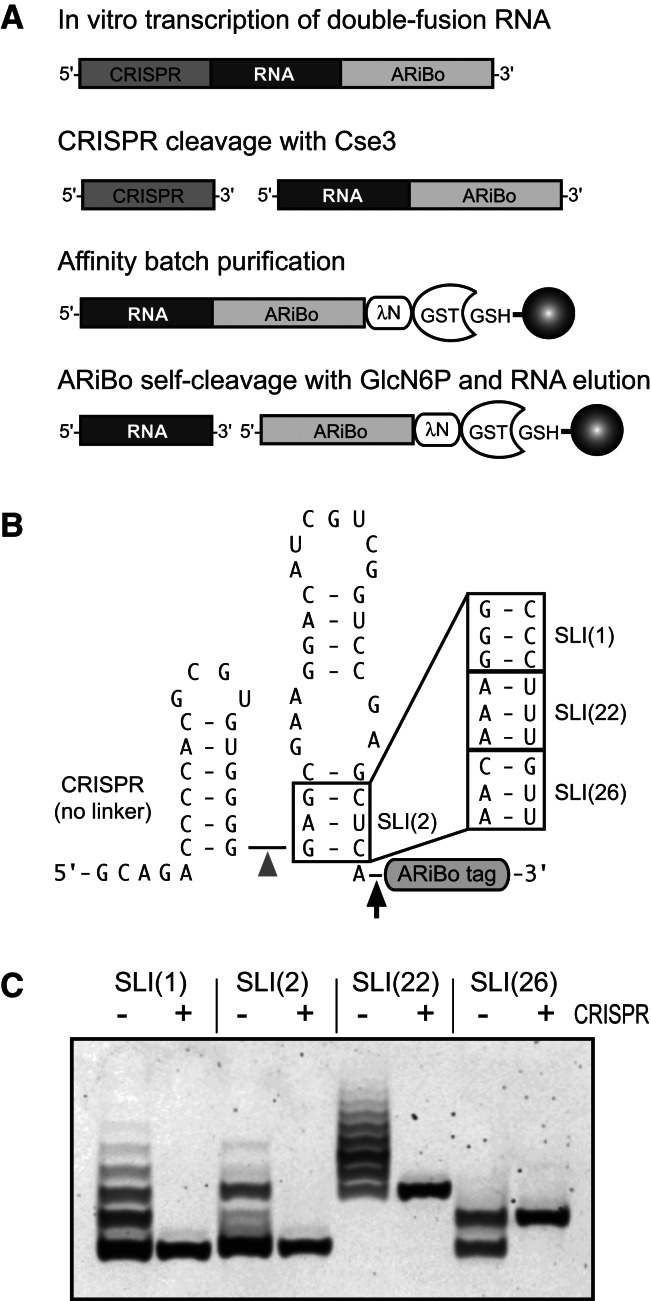

Ensuring 5′ homogeneity by Cse3 cleavage of a CRISPR RNA tag

With the goal of developing a reliable system for ensuring 5′ homogeneity of RNA, we investigated cleavage of CRISPR RNA tags by the T. thermophilus Cse3 endoribonuclease. First, a CRISPR-SLI(2)-ARiBo double-fusion RNA was synthesized with a 21-nt CRISPR RNA stem–loop tag at the 5′ end of the RNA of interest [here SLI(2)-ARiBo] (Fig. 4A). The CRISPR RNA tag contains a mutant 5′-GCAGA tail sequence to allow multiple turnover kinetics and the AUG linker sequence 3′ of the cleavage site (Sashital et al. 2011). According to previous studies, such a CRISPR RNA tag should be quickly cleaved by Cse3 (Sashital et al. 2011). Not surprisingly, complete cleavage (≥99%) is obtained in as little as 5 min when incubating 1 μM CRISPR–SLI(2)-ARiBo double-fusion RNA with 1–2 μM Cse3 at the optimum enzyme temperature of 70°C (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, similar results are obtained at 37°C, a lower temperature that helps reduce nonenzymatic RNA hydrolysis (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of CRISPR–RNA junction sequence on Cse3 cleavage. (A) Schematic representation of CRISPR–SLI(2)-ARiBo double-fusion RNAs with the original CRISPR sequence (AUG linker) or related variants with sequence changes at the CRISPR–RNA junction (boxed area). (Gray arrowhead) Points to the Cse3 cleavage site; (black arrow) points to the glmS cleavage site. (B–E) Cse3 cleavage of CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNAs analyzed on 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gels stained with SYBR Gold. Cse3 cleavage was performed using aliquots from the transcription reactions (∼1 μM RNA), 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl, either 1 or 2 μM Cse3, and different incubation times, as indicated above each lane. For experiments reported in B, Cse3 cleavage was performed at either 37°C or 70°C, as indicated, whereas for those reported in C–E, Cse3 cleavage was performed at 70°C. The gel mobilities of the RNA precursor (CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo) and the Cse3 cleavage product (SLI-ARiBo) are indicated with arrows on the right side of the gels. The percentages of Cse3 cleavage are given below the gels.

A variant of this original CRISPR sequence (Fig. 4A) was designed to eliminate the 3′-AUG linker sequence and allow production of the SLI(2)-ARiBo RNA, without extra nucleotides at its 5′ end. As expected, the cleavage efficiency of this “no linker” variant is significantly reduced, particularly at 37°C, where only 25% cleavage is reached using 2 μM Cse3 for 15 min. Nevertheless, complete cleavage (≥99%) is obtained when incubating the CRISPR–SLI(2)-ARiBo RNA for 15 min at 70°C with 1–2 μM Cse3 (Fig. 4B).

To further investigate the CRISPR requirements for Cse3 cleavage, several other variants of the CRISPR–SLI(2)-ARiBo RNA were tested for Cse3 cleavage at 37°C (Supplemental Fig. S3) and 70°C (Fig. 4). First, variants similar to the “no linker” variant were tested that contain different Watson–Crick base pairs involving the 5′ nucleotide of SLI (no linker GC → AU, no linker GC → CG, no linker GC → UA) (Fig. 4A). Cse3 cleavage of these variants was tested at 37°C with 1–2 μM Cse3 for 15–30 min, but only the SLI starting with an A (no linker GC → AU) is completely cleaved under these conditions (Supplemental Fig. S3B). Interestingly, the SLI RNAs starting with G (no linker), A (no linker GC → AU), and C (no linker GC → CG) are all completely cleaved when incubated at 70°C with 2 μM Cse3 for 15 min (Fig. 4C). For the SLI RNA starting with a U (no linker GC → UA), the 15-min incubation at 70°C provides only 95% cleavage (Fig. 4C). To improve cleavage of this variant (no linker GC → UA), we transcribed it again with a reversion of the 5′-GCAGA tail to the wild-type 5′-GUAGU sequence, assuming that it may help destabilize an interaction between the A5 of the CRISPR and the U1 of SLI that likely inhibits cleavage (Sashital et al. 2011). As anticipated, this variant (no linker GC → UA with 5′-GUAGU tail) is a better substrate for Cse3 than the parental construct (no linker GC → UA) and yields complete cleavage when incubated at 70°C with 2 μM Cse3 for 15 min (Supplemental Fig. S4). Thus, complete Cse3 cleavage (≥99%) can be quickly obtained between a 5′-CRISPR tag and the desired RNA in which the first nucleotide is involved in any of the four standard Watson–Crick base pair.

Next, we tested the effect of short linkers on Cse3 cleavage efficiency. Single-nucleotide linkers, containing A, C, G, or U, do not allow complete cleavage of the CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNA when incubated at 37°C with 1–2 μM Cse3 for 15–30 min; however, the A linker provides the most efficient cleavage (up to 69%) under these conditions (Supplemental Fig. S3C). Thus, dinucleotide linkers starting with an A were tested, and 98%–100% Cse3 cleavage of CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNAs carrying these linkers is obtained at 37°C with 2 μM Cse3 for 30 min (Supplemental Fig. S3D). Again, cleavage of these variants is more efficient at 70°C, with the single-nucleotide A, C, and G linkers being cleaved to completion when incubated with 2 μM Cse3 for 45 min or less (Fig. 4D) and the four tested dinucleotide linkers (AA, AC, AG, and AU linkers) being cleaved to completion when incubated with 1 μM Cse3 for 5 min (Fig. 4E). Cse3 cleavage of the CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNA with the single-nucleotide U linker is still very low (51%) under stringent conditions (70°C, 2 μM Cse3 for 45 min). However, in the context of the 5′-GUAGU reversion variant, the CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNA with the single-nucleotide U linker (U linker with 5′-GUAGU tail) is a better substrate for Cse3, which achieves complete cleavage of the CRISPR tag when incubated at 70°C with 2 μM Cse3 for 90 min (Supplemental Fig. S5). So far, this 5′-GUAGU tail reversion improves cleavage of the CRISPR tag to yield two SLI RNA variants starting with a U (no linker GC → UA and U linker), in agreement with this U forming an A-U base pair in the 5′-GCAGA tail context that interferes with Cse3 cleavage (Sashital et al. 2011). With the goal of further improving cleavage conditions for these two SLI variants, we also tested the Cse3 N102A mutant, which is known to increase enzyme turnover (Sashital et al. 2011). However, this Cse3 mutant did not improve the cleavage results of the two SLI variants with the 5′-GUAGU tail reversion (data not shown). Nevertheless, complete Cse3 cleavage (≥99%) can be obtained for all variants tested containing linkers of 0–3 nucleotides between a 5′-CRISPR tag and the desired RNA. As validated here with the SLI RNA, the Cse3/CRISPR system constitutes a reliable molecular tool to ensure 5′ homogeneity of in vitro–transcribed RNA.

Affinity purification of RNA with homogeneous ends using CRISPR and ARiBo tags

To investigate the compatibility of the Cse3/CRISPR system with affinity purification of RNA, we modified our ARiBo-based affinity purification procedure (Di Tomasso et al. 2011) by incorporating a Cse3 cleavage step after the transcription and before affinity immobilization (Fig. 5A). This new procedure was tested with CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo precursors (Fig. 5B) containing SLI sequences that give the highest levels of 5′-sequence heterogeneity when purified from SLI-ARiBo precursors (Fig. 5B). As expected, affinity purification of these SLI RNAs from CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo transcripts yields in each case a single SLI product, and thus completely resolves the problem of 5′-sequence heterogeneity observed previously for these SLI RNAs (Fig. 5C). In addition, the alkaline phosphatase step can be bypassed because Cse3 cleavage produces a 5′-hydroxyl terminus (Gesner et al. 2011; Jore et al. 2011). Furthermore, affinity purifications from these double-fusion RNAs are fairly efficient with 13%–38% SLI RNA eluted and low levels of contaminants (≤1% ARiBo tag and ≤0.5% CRISPR–SLI) (Supplemental Fig. S6). The level of cleaved CRISPR tag contaminants varies depending on the SLI RNAs; those purifications requiring the most stringent Cse3 cleavage conditions produce 1%–4% cleaved CRISPR-tag contaminant, whereas that of SLI(2) starting with GAG was essentially free of such contaminant (≤1%) (Supplemental Fig. S6). These results clearly demonstrate the compatibility of the ARiBo affinity purification with Cse3 cleavage of a 5′-CRISPR tag.

FIGURE 5.

Affinity purification of RNA with homogeneous ends using CRISPR and ARiBo tags. (A) General strategy for affinity batch purification of RNA from a CRISPR–RNA-ARiBo precursor, a double-fusion RNA with a 5′-CRISPR tag and a 3′-ARiBo tag. After transcription, Cse3 cleavage of the CRISPR tag yields the ARiBo-fusion RNA, which is bound to a λN-GST fusion protein and immobilized on GSH-Sepharose beads. After several washes, RNA elution is triggered by addition of GlcN6P, which activates the glmS ribozyme of the ARiBo tag. (B) Schematic representation of CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo double-fusion RNAs with an AUG deletion (no linker) just 3′ from the Cse3 cleavage site. (C) Small-scale affinity batch purifications of SLI RNAs from SLI-ARiBo (− lanes) and CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo (+ lanes) precursors analyzed on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel stained with SYBR Gold. For purification of SLI-ARiBo precursors, the E1 elution fractions were treated with calf alkaline phosphatase prior to loading on the gel; they correspond to samples shown in Figures 2D and 3C. For CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo precursors, CRISPR cleavage was performed for 15 min at 70°C using an RNA:Cse3 ratio of 1:2 [SLI(2)] or for 30 min at 70°C using an RNA:Cse3 ratio of 1:4 [SLI(1), SLI(22), and SLI(26)]. Aliquots of the E1 elution fractions were loaded on the gel.

DISCUSSION

Several strategies are available to ensure 5′-sequence homogeneity of RNA transcribed in vitro with the T7 RNAP. First, if the 5′-sequence composition of the RNA of interest is not restricted, it can be selected among those that yield very low 5′ heterogeneity. The percentages of 5′-sequence heterogeneity obtained here for the SLI RNAs may provide a useful reference for future RNA syntheses. When using the wild-type T7 RNAP, low levels of 5′-sequence heterogeneity (≤1.5%) were observed only for 5′-GNN sequences starting with GUG, GGA, GAA, GCA, GUA, GAC, GUC, GGU, GAU, GCU, or GUU and 5′-ANN sequences starting with AAG, ACG, AGC, ACU, and AUU. The pool of starting sequences that yields acceptable levels of 5′ homogeneity is slightly expanded when using the P266L mutant, since it also includes those starting with GCC, AUG, and AGU.

For producing RNA with homogeneous 5′ ends, the Cse3/CRISPR system provides a more general approach. Interestingly, we found that the Cse3 cleavage of the 5′-CRISPR tag can be achieved quickly and efficiently at 70°C from CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNA transcripts to generate SLI-ARiBo RNAs starting with any of the four standard nucleotides (G, C, A, or U) within either a single- or double-stranded structure. The compatibility of the Cse3/CRISPR system with our batch affinity purification protocol using an ARiBo tag makes it possible to quickly purify RNA with homogeneity at both the 5′ and the 3′ ends. For a given CRISPR–RNA-ARiBo precursor, Cse3 cleavage conditions can be optimized to ensure complete CRISPR cleavage generally within 45 min or less. The selection of a 5′ sequence for which complete Cse3 cleavage can be obtained quickly at 37°C should be considered, if possible, to prevent RNA conformational changes and minimize nonenzymatic RNA hydrolysis that may occur at higher temperatures. Complete Cse3 cleavage can be obtained in 30 min or less at 37°C for RNA sequences starting with a paired adenine or with a single-stranded AUG, AU, AC, or AG sequence. With such starting sequences, it should be straightforward to purify RNA with homogeneous 5′ and 3′ ends under nondenaturing conditions from a CRISPR–RNA-ARiBo precursor cleaved with Cse3 and then purified by affinity using the ARiBo tag.

Preparation of RNA with 5′ homogeneity using the Cse3/CRISPR system presents one minor limitation but several important advantages, particularly when compared with commonly used cis-cleaving hammerhead ribozymes (Taira et al. 1991; Price et al. 1995; Ferré-D’Amaré and Doudna 1996; Walker et al. 2003). The minor limitation is the requirement for large quantities of purified Cse3, which is most effective at protein:RNA ratios of 1:1, 2:1, or higher. Nevertheless, the Cse3 protein can be purified easily with high yields (200 mg/L of media). Despite this minor limitation, there are several important advantages of the Cse3/CRISPR system that are worth considering. The CRISPR tag is relatively small, which may be desirable when transcribing RNA in the presence of limiting, modified, and/or expensive NTPs. Like the hammerhead ribozymes, the Cse3 endoribonuclease is sequence specific; thus, there should be little concern with undesirable cleavage outside the tag. Cse3 has also little sequence requirement 3′ of the cleavage site, and thus usage of a 5′-CRISPR tag expands the sequence possibilities for the first nucleotide of the RNA target beyond that permitted by the T7 RNAP. Moreover, unlike ribozymes used as 5′ tags, the CRISPR tag folds independently of the RNA of interest, and there is no need to systematically tailor the tag sequence for each new RNA sequence. The fact that complete cleavage of the 5′ tag can be obtained quickly is also a distinct advantage of the Cse3/CRISPR system. Evidently, complete cleavage helps ensure high yields of purified RNA. More importantly, it ensures high RNA purity when combined with affinity purification, because incomplete cleavage would yield CRISPR–RNA contaminants in the final RNA sample and thus reduce the advantage of ARiBo-based affinity purification. Incomplete cleavage can be problematic for ribozyme tags that require folding of an active structure that is incompatible with that of the RNA target (Grosshans and Cech 1991; Price et al. 1995; Walker et al. 2003). In contrast, the Cse3/CRISPR system is well suited for batch affinity purification using the ARiBo tag, and the combination of the CRISPR and ARiBo tags allows for rapid production of RNA with homogeneity at both the 5′ and the 3′ ends.

The practicality of the ARiBo-based affinity purification has already been demonstrated for several RNAs, including the small SLI RNA hairpin (29 nt) (this study), the let-7g pre-miRNA (46 nt) (Di Tomasso et al. 2012a), a purine riboswitch variant (69 nt) (Di Tomasso et al. 2011), and the Neurospora VS ribozyme (138 nt) (this study). Here, we described two approaches to ensure that the affinity-purified RNA has a homogeneous 5′ end, either choosing an appropriate GNN/ANN starting sequence or incorporating the Cse3/CRISPR system in the purification scheme. The latter option, although more elaborate, may be particularly advantageous for preparation of RNAs starting with a GNN/ANN sequence that do not allow 5′ homogeneity or that start with a YNN sequence. Furthermore, the Cse3/CRISPR system provides a novel tool for RNA purification that can be either used by itself or combined with other purification methods, such as the ARiBo-based affinity purification. Future studies will help define its range of applicability for different RNA sequences and purification strategies, and creative applications may reveal additional advantages of this system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of the λN+-L+-GST protein

The expression and purification of the λN+-L+-GST protein was performed as described earlier (Di Tomasso et al. 2011, 2012b).

Expression and purification of the T. thermophilus Cse3 endoribonuclease

The pET-30a(+) vector containing the T. thermophilus Cse3 gene was a kind gift from A.M. MacMillan (University of Alberta) (Gesner et al. 2011). The plasmid was transformed into Rosetta (DE3) cells (Novagen). The bacteria were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) media, and protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 h at 25°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in Cse3 buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.4, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 20 mM imidazole) supplemented with 0.15% (w/v) protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were lysed by French press, sonicated for 10 sec, and centrifuged at 12,000g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then heated for 30 min at 55°C and ultracentrifuged at 138,000g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with Ni-charged IMAC Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare). The resin was then washed two times with the Cse3 buffer. The bound His6-tagged Cse3 fusion protein was eluted from the resin by two 10-min incubations at room temperature with elution buffer (Cse3 buffer + 180 mM imidazole). The supernatant was dialyzed overnight at 4°C in FPLC-A buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT) and then applied to an SP Sepharose high-performance column (GE Healthcare; 100-mL bed volume) equilibrated with FPLC-A buffer. The proteins were eluted from the column using a gradient (0%–100% over 525 mL) of FPLC-B buffer (FPLC-A buffer with 2 M NaCl). The pooled fractions containing the protein of interest were dialyzed overnight at 4°C in Cse3 storage buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, and 20% glycerol). The purity (≥95%) and correct mass of the protein were verified by SDS-PAGE and mass spectroscopy, respectively, whereas its RNase-free state was verified as previously described (Di Tomasso et al. 2012b).

Expression and purification of the wild-type and mutant T7 RNAP

The wild-type T7 RNAP with an N-terminal His6 tag was prepared from Escherichia coli strain BL21 carrying the plasmid pT7-911Q. The P266L mutant clone was prepared from the wild-type T7 clone using the QuikChangeII site-restricted mutagenesis procedure (Stratagene) and verified by DNA sequencing. The bacteria were grown at 37°C in LB media, and protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 h at 30°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in T7 buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM imidazole, 1 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol) supplemented with Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets (Roche). The cells were lysed by French press, sonicated for 10 sec, and centrifuged at 138,000g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with Ni-charged IMAC Sepharose 6 Fast Flow beads (GE Healthcare). The resin was then washed once with T7 buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor, three times with T7 buffer, and four times with Ni wash buffer (T7 buffer + 9 mM imidazole). The bound T7 RNAP was eluted from the resin by three 5-min incubations at room temperature with elution buffer (T7 buffer + 199 mM imidazole). The supernatant was dialyzed at 4°C in S7 nuclease buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM DTT) and then incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 75 units of S7 nuclease (Roche) per liter of bacteria. The sample was then dialyzed overnight at 4°C in Cobalt buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM imidazole, and 1 mM DTT), and the dialyzed sample was applied on a Co-charged IMAC Sepharose 6 Fast Flow column (GE Healthcare). The resin was washed with 3 column volumes of Cobalt buffer and with 3 column volumes of Cobalt wash buffer (Cobalt buffer + 49 mM imidazole). The bound T7 RNAP was eluted from the resin with elution buffer (Cobalt buffer + 299 mM imidazole). The pooled fractions containing the protein of interest were dialyzed overnight at 4°C in T7 storage buffer (20 mM KH2PO4, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 50% glycerol, adjusted to pH 8.0). The high purity (≥98%) of the protein was verified by SDS-PAGE.

Cloning of the pSLI-ARiBo and pCRISPR–SLI-ARiBo plasmids

The pARiBo4 plasmid expressing the ARiBo4 tag (Supplemental Fig. S1) was generated by mutagenesis of the pARiBo1 plasmid (Di Tomasso et al. 2011). All pSLI-ARiBo4 plasmids expressing the SLI-ARiBo4 fused RNAs (Figs. 1A, 2A, 3A) were obtained by mutagenesis of the pARiBo4 plasmid. The pCRISPR-SLI-ARiBo plasmids expressing the CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNAs were generated by mutagenesis of pSLI(2)-ARiBo4. The pCRISPR-SLI-ARiBo plasmids contain two restriction sites for subcloning: the BstXI site (5′-CCANNNNNNTGG-3′) located within the CRISPR sequence and the ApaI site located within the boxB hairpin (5′-GGGCCC-3′) at the 5′ end of the ARiBo tag. All mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChangeII site-restricted mutagenesis procedure, and all sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

In vitro transcription of ARiBo-fused RNAs

Medium-scale preparations (∼0.5 mg) of plasmid DNA template were typically obtained by growing 0.15 L of plasmid-transformed DH5α cells (Invitrogen), purifying the plasmid using the QIAGEN Plasmid Maxi Kit, and linearizing it with EcoRI (New England Biolabs). The SLI-ARiBo fusion RNAs were transcribed for 3 h at 37°C using the following reaction conditions: 40 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 50 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM spermidine, 4 mM ATP, 4 mM CTP, 4 mM UTP, 4 mM GTP, 20 mM MgCl2, 60 µg/mL His-tagged T7 RNAP, 3 units/mL RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega), and 80 µg/mL linearized plasmid DNA template. The CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNAs were transcribed using the same conditions, although 25 mM MgCl2 and a template concentration of 120 µg/mL were used for some variants. Transcription reactions were stopped by adding 20–25 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and stored at −20°C.

Small-scale affinity batch purification of SLI RNAs from SLI-ARiBo fusion RNAs

Small-scale affinity batch purifications were performed as described earlier (Di Tomasso et al. 2011, 2012b). Briefly, 17.5 nmol of λN+-L+-GST fusion protein was first added to an aliquot of the transcription reaction (75–200 µL) containing 3.5 nmol of ARiBo-fused SLI, and the volume was completed to 400 µL with equilibration buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5). After a 15-min incubation, the RNA–protein mix was added to a spin cup column (Pierce) containing 125 µL of washed GSH-Sepharose 4B resin (from 163 µL of slurry) (GE Healthcare) and incubated for 15 min. The load eluate was collected by centrifugation for 1 min at 5000g. The resin was washed three times with 400 µL of equilibration buffer. All washes include incubation for 5 min and centrifugation for 1 min at 5000g. For elution, the resin was incubated for 30 min at 37°C in 400 µL of elution buffer (20–40 mM Tris buffer at pH 7.6, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1–10 mM GlcN6P) and at room temperature for 5 min prior to centrifugation. The resin was then washed two times with 400 µL of equilibration buffer. Finally, the resin was washed with 400 µL of 2.5 M NaCl. The load eluates (LE), wash eluates (W1, W2, W3), elution (E1), elution-washes (E2 and E3), and NaCl eluates (NaCl) were kept for quantitative analysis.

VS ribozyme cleavage during affinity purification

The small-scale affinity batch purification was slightly modified by incorporating a VS ribozyme cleavage step and two additional wash steps between the third wash (W3) and the RNA elution step (E1). For VS ribozyme cleavage, the Avapl ribozyme was prepared by in vitro T7 RNAP transcription from the pAvapl-ARiBo1 plasmid derived from pAvapl (Bouchard et al. 2008; Di Tomasso et al. 2012a), linearized with EcoRI, and purified by affinity, as previously described (Di Tomasso et al. 2011, 2012a). The VS ribozyme cleavage step was performed for 30 min at 37°C in 400 µL of VS cleavage buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.5 U RNasin [Promega], and 9.75 nM Avapl ribozyme) followed by an incubation of 5 min at room temperature prior to centrifugation.

Calf alkaline phosphatase cleavage of affinity-purified SLI RNAs

For calf alkaline phosphatase cleavage, aliquots (corresponding to ∼0.125 nmol SLI RNA) of E1 elutions from small-scale affinity batch purifications were incubated for 3 h at 37°C in a total volume of 50 μL containing CIP buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 8.0 and 0.1 mM EDTA), 0.5 units of RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega), and 10 units of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Roche).

Cse3 cleavage assay

For Cse3 cleavage, 1 μM unpurified CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNA from the transcription reaction was incubated at 37°C or 70°C in the Cse3 reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.5 and 150 mM KCl) with either 1 or 2 μM Cse3 protein. Aliquots (0.75 μL) were removed from the 25-μL reaction mixture at specific times, and the reaction was stopped by addition of 10 μL of loading dye (25 mM EDTA and Bromophenol Blue in formamide), transferred to 4°C, and separated on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Affinity batch purification of SLI RNAs from CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo fusion RNAs

The CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo double-fusion RNAs were synthesized from the class III T7 promoter using the wild-type T7 RNAP. The small-scale affinity batch purification of these RNAs was performed as for SLI-ARiBo fusion RNAs, except that, prior to starting, a small volume of the transcription reaction corresponding to 1.86 nmol of CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo RNA was incubated with either 3.72 nmol [SLI(2)] or 7.44 nmol [SLI(1), SLI(22), and SLI(26)] of Cse3 protein at 70°C in Cse3 reaction buffer supplemented with 1.67 units of RNasin (Promega) for a total reaction volume of 200 μL. A Cse3 inactivation step, which consists of a 2-min incubation at 95°C and 5-min cooling on ice, was added to improve sample migration on the gel but has no effect on the performance of the method. The affinity batch purification was then resumed as described above, but downscaled by a factor of two to account for the smaller quantity of starting RNA (1.75 nmol). In addition, the first wash buffer was supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2 to reduce the amount of CRISPR-tag impurity in the elution fractions.

Quantitative analysis from denaturing gels stained with SYBR Gold

Aliquots from the various steps of small-scale affinity batch purifications and Cse3 cleavage were analyzed by denaturing gel electrophoresis using polyacrylamide gels containing 7 M urea. Care was taken to load gels with sample volumes corresponding to precise amounts of SLI-ARiBo or CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo fusion RNA present in the transcription reaction. The gels were pre-run at 400–600 V for 20 min prior to loading the samples, and then they were run at 400–600 V for 2–4 h. The gels were stained for 10 min in a SYBR Gold (Invitrogen) solution (1:10,000 dilution in TBE buffer [50 mM Tris-Base, 50 mM boric acid, and 1 mM EDTA]) and scanned on a ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad). The band intensities were analyzed using the Image Lab software (version 4.0.1 from Bio-Rad).

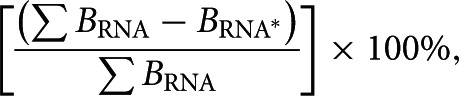

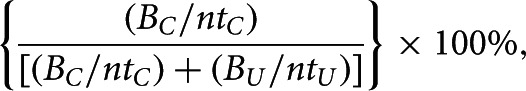

The percentage of 5′ heterogeneity was calculated from the E1 elution fraction of affinity purifications treated with calf alkaline phosphatase using the following equation:

|

where ∑BRNA represents the sum of the intensities of all the SLI RNA bands and BRNA* represents the intensity of the reference SLI band only.

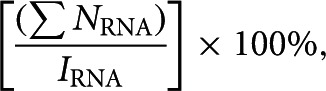

For Cse3 cleavage assays, the percentage of Cse3 cleavage was determined using the following equation:

|

where BC and BU correspond to the band intensities of Cse3-cleaved and uncleaved CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo fusion RNA, respectively; ntC and ntU represent the number of nucleotides for the SLI-ARiBo and CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo fusion RNAs, respectively.

Quantitative analysis of small-scale affinity batch purifications from CRISPR–SLI-ARiBo precursors was achieved based on our published procedure for quantification of affinity purification from RNA-ARiBo precursors (Di Tomasso et al. 2011). First, control lanes were loaded with known amounts of RNA to derive standard curves that were used to determine the quantity (in nanograms) of SLI (NRNA), CRISPR tag (NCRISPR), ARiBo tag (NARiBo), and SLI-ARiBo fusion RNA (NFusion) at each purification step. For the SLI- and CRISPR-tag standard curves, known quantities of purified CRISPR RNA and a control RNA derived from SLI (5′-GAGCGAAGGCUGGACCACCAGCCGAGCUC-3′) were loaded on the gel, whereas other standard curves were calibrated as previously described (Di Tomasso et al. 2011). The percentage of RNA eluted was calculated using the following equation:

|

where ∑NRNA represents the total amount of SLI (in nanograms) detected in lanes E1 and E2, and IRNA represents the calculated amount of SLI expected from an equivalent volume of transcription (100 ng). In addition, the percentages of ARiBo tag and CRISPR-tag impurities were calculated from the E1 lane using the equations [NARiBo/(NRNA + NARiBo)] × 100% and [NCRISPR/(NRNA + NCRISPR)] × 100%, respectively.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Andrew MacMillan for the expression vector of T. thermophilus His-tagged Cse3, Julie Lacroix-Labonté for the control SLI RNA, and James G. Omichinski for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants to P.L. from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR; HOP-83068 and MOP-86502) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (NSERC). A.S.L. and B.L.P., respectively, hold graduate and summer scholarships from the CDMC-CREATE (Cellular Dynamics of Macromolecular Complexes–Collaborative Research and Training Experience) program funded by NSERC. P.L. holds a Canada Research Chair in Engineering and Structural Biology of RNA.

REFERENCES

- Al-Attar S, Westra ER, van der Oost J, Brouns SJ 2011. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs): The hallmark of an ingenious antiviral defense mechanism in prokaryotes. Biol Chem 392: 277–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey RT, Kieft JS 2007. Improved native affinity purification of RNA. RNA 13: 1384–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard P, Lacroix-Labonté J, Desjardins G, Lampron P, Lisi V, Lemieux S, Major F, Legault P 2008. Role of SLV in SLI substrate recognition by the Neurospora VS ribozyme. RNA 14: 736–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns SJ, Jore MM, Lundgren M, Westra ER, Slijkhuis RJ, Snijders AP, Dickman MJ, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, van der Oost J 2008. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science 321: 960–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazenave C, Uhlenbeck OC 1994. RNA template-directed RNA synthesis by T7 RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91: 6972–6976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin M, Ryan T 1982. Bacteriophage DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. In The enzymes (ed. Boyer PD), Vol. XV, pp. 87–108 Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Coleman TM, Wang G, Huang F 2004. Superior 5′ homogeneity of RNA from ATP-initiated transcription under the T7 φ2.5 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res 32: e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham PR, Weitzmann CJ, Ofengand J 1991. SP6 RNA polymerase stutters when initiating from an AAA … sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 19: 4669–4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tomasso G, Lampron P, Dagenais P, Omichinski JG, Legault P 2011. The ARiBo tag: A reliable tool for affinity purification of RNAs under native conditions. Nucleic Acids Res 39: e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tomasso G, Dagenais P, Desjardins A, Rompré-Brodeur A, Delfosse V, Legault P 2012a. Affinity purification of RNA using an ARiBo tag. Methods Mol Biol 941: 137–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Tomasso G, Lampron P, Omichinski JG, Legault P 2012b. Preparation of λN-GST fusion protein for affinity immobilization of RNA. Methods Mol Biol 941: 123–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna JA 1997. Preparation of homogeneous ribozyme RNA for crystallization. Methods Mol Biol 74: 365–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JJ, Studier FW 1983. Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage T7 DNA and the locations of T7 genetic elements. J Mol Biol 166: 477–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzianott AM, Bujarski JJ 1988. An in vitro transcription vector which generates nearly correctly ended RNAs by self-cleavage of longer transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 16: 10940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Doudna JA 1996. Use of cis- and trans-ribozymes to remove 5′ and 3′ heterogeneities from milligrams of in vitro transcribed RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 977–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank R, Köster H 1979. DNA chain length markers and the influence of base composition on electrophoretic mobility of oligodeoxyribonucleotides in polyacrylamide-gels. Nucleic Acids Res 6: 2069–2087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garside EL, Schellenberg MJ, Gesner EM, Bonanno JB, Sauder JM, Burley SK, Almo SC, Mehta G, Macmillan AM 2012. Cas5d processes pre-crRNA and is a member of a larger family of CRISPR RNA endonucleases. RNA 18: 2020–2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesner EM, Schellenberg MJ, Garside EL, George MM, Macmillan AM 2011. Recognition and maturation of effector RNAs in a CRISPR interference pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 688–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans CA, Cech TR 1991. A hammerhead ribozyme allows synthesis of a new form of the Tetrahymena ribozyme homogeneous in length with a 3′ end blocked for transesterification. Nucleic Acids Res 19: 3875–3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillerez J, Lopez PJ, Proux F, Launay H, Dreyfus M 2005. A mutation in T7 RNA polymerase that facilitates promoter clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 5958–5963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haurwitz RE, Jinek M, Wiedenheft B, Zhou K, Doudna JA 2010. Sequence- and structure-specific RNA processing by a CRISPR endonuclease. Science 329: 1355–1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M, Brule H, Giege R, Florentz C 1999. More mistakes by T7 RNA polymerase at the 5′ ends of in vitro–transcribed RNAs. RNA 5: 618–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B, Mitchell GT, Gendron P, Major F, Andersen AA, Collins RA, Legault P 2003. NMR structure of the active conformation of the Varkud satellite ribozyme cleavage site. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 7003–7008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P, Barrangou R 2010. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science 327: 167–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imburgio D, Rong MQ, Ma KY, McAllister WT 2000. Studies of promoter recognition and start site selection by T7 RNA polymerase using a comprehensive collection of promoter variants. Biochemistry 39: 10419–10430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jore MM, Lundgren M, van Duijn E, Bultema JB, Westra ER, Waghmare SP, Wiedenheft B, Pul U, Wurm R, Wagner R, et al. 2011. Structural basis for CRISPR RNA-guided DNA recognition by Cascade. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 529–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao C, Zheng M, Rudisser S 1999. A simple and efficient method to reduce nontemplated nucleotide addition at the 3′ terminus of RNAs transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase. RNA 5: 1268–1272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karginov FV, Hannon GJ 2010. The CRISPR system: Small RNA-guided defense in bacteria and archaea. Mol Cell 37: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft JS, Batey RT 2004. A general method for rapid and nondenaturing purification of RNAs. RNA 10: 988–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp G 1988. RNA synthesis: Strategies for the use of bacteriophage RNA polymerases. Gene 72: 75–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix-Labonte J, Girard N, Lemieux S, Legault P 2012. Helix-length compensation studies reveal the adaptability of the VS ribozyme architecture. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 2284–2293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham J, Crothers DM 1996. RNase H cleavage for processing of in vitro transcribed RNA for NMR studies and RNA ligation. RNA 2: 289–296 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrach H, Diamond D, Wozney JM, Boedtker H 1977. RNA molecular weight determinations by gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions, a critical reexamination. Biochemistry 16: 4743–4751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Haft DH, Barrangou R, Brouns SJ, Charpentier E, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJ, Wolf YI, Yakunin AF, et al. 2011. Evolution and classification of the CRISPR–Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol 9: 467–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ 2010. CRISPR interference: RNA-directed adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea. Nat Rev Genet 11: 181–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CT, Muller DK, Coleman JE 1988. Processivity in early stages of transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. Biochemistry 27: 3966–3974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton DA, Krieg PA, Rebagliati MR, Maniatis T, Zinn K, Green MR 1984. Efficient in vitro synthesis of biologically active RNA and RNA hybridization probes from plasmids containing a bacteriophage SP6 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res 12: 7035–7056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan JF, Groebe DR, Witherell GW, Uhlenbeck OC 1987. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res 15: 8783–8798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroney SE, Piccirilli JA 1991. Abortive products as initiating nucleotides during transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. Biochemistry 30: 10343–10349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen FH, Leunissen EH, van de Laar L, Tessari M, Heus HA, Wijmenga SS 2012. Fast production of homogeneous recombinant RNA—towards large-scale production of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 40: e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira MJ, Behera V, Walter NG 2010. Nondenaturing purification of co-transcriptionally folded RNA avoids common folding heterogeneity. Plos ONE 5: e12953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleiss JA, Derrick ML, Uhlenbeck OC 1998. T7 RNA polymerase produces 5′ end heterogeneity during in vitro transcription from certain templates. RNA 4: 1313–1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price SR, Ito N, Oubridge C, Avis JM, Nagai K 1995. Crystallization of RNA–protein complexes. I. Methods for the large-scale preparation of RNA suitable for crystallographic studies. J Mol Biol 249: 398–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Tapia LE, Martin CT 2012. New insights into the mechanism of initial transcription: The T7 RNA polymerase mutant P266L transitions to elongation at longer RNA lengths than wild type. J Biol Chem 287: 37352–37361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro SW, Joyce GF 1997. A general purpose RNA-cleaving DNA enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94: 4262–4266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sashital DG, Jinek M, Doudna JA 2011. An RNA-induced conformational change required for CRISPR RNA cleavage by the endoribonuclease Cse3. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 680–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schürer H, Lang K, Schuster J, Mörl M 2002. A universal method to produce in vitro transcripts with homogeneous 3′ ends. Nucleic Acids Res 30: e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherlin LD, Bullock TL, Nissan TA, Perona JJ, Lariviere FJ, Uhlenbeck OC, Scaringe SA 2001. Chemical and enzymatic synthesis of tRNAs for high-throughput crystallization. RNA 7: 1671–1678 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira K, Nakagawa K, Nishikawa S, Furukawa K 1991. Construction of a novel RNA-transcript-trimming plasmid which can be used both in vitro in place of run-off and (G)-free transcriptions and in vivo as multi-sequences transcription vectors. Nucleic Acids Res 19: 5125–5130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terns MP, Terns RM 2011. CRISPR-based adaptive immune systems. Curr Opin Microbiol 14: 321–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SC, Avis JM, Conn GL 2003. General plasmids for producing RNA in vitro transcripts with homogeneous ends. Nucleic Acids Res 31: e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA 2012. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 482: 331–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt JR, Chastain M, Puglisi JD 1991. Synthesis and purification of large amounts of RNA oligonucleotides. BioTechniques 11: 764–769 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]