Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Nearly 25% of solid renal tumors are indolent cancer or benign and can be managed conservatively in selected patients. This prospective study was performed to determine whether preoperative IV microbubble contrast-enhanced ultrasound can be used to differentiate indolent and benign renal tumors from more aggressive clear cell carcinoma.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Thirty-four patients with renal tumors underwent preoperative gray-scale, color, power Doppler, and octafluoropropane microbubble IV contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Three blinded radiologists reading in consensus compared rate of contrast wash-in, grade and pattern of enhancement, and contrast washout compared with adjacent parenchyma. Contrast ultrasound findings were compared with surgical histopathologic findings for all patients.

RESULTS

The 34 patients had 23 clear cell carcinomas, three type 1 papillary carcinomas, one chromophobe carcinoma, one clear rare multilocular low-grade malignant tumor, two unclassified lesions, three oncocytomas, and one benign angiomyolipoma. The combination of heterogeneous lesion echotexture and delayed lesion washout had 85% positive predictive value, 43% negative predictive value, 48% sensitivity, and 82% specificity for predicting whether a lesion was conventional clear cell carcinoma or another tumor. Diminished lesion enhancement grade had 75% positive predictive value, 81% negative predictive value, 55% sensitivity, and 91% specificity for non–clear cell histologic features, either benign or low-grade malignant. Combining delayed washout with quantitative lesion peak intensity of at least 20% of kidney peak intensity had 91% positive predictive value, 40% negative predictive value, 63% sensitivity, and 80% specificity in the prediction of clear cell histologic features.

CONCLUSION

Ultrasound features of gray-scale heterogeneity, lesion washout, grade of contrast enhancement, and quantitative measure of peak intensity may be useful for differentiating clear cell carcinoma and non–clear cell renal tumors.

Keywords: clear cell carcinoma, IV contrast medium, kidney, microbubbles, ultrasound

Renal cortical neoplasms are a complex family of tumors with varying histologic subtypes, aggressiveness, and metastatic potential. The histologic renal cortical tumor subtypes are shown in Table 1 [1]. With increased use of diagnostic imaging, renal cortical tumors more often are detected incidentally, and lesion size at detection is smaller [2]. Most renal cortical neoplasms are surgically resected, but depending on the series, approximately 30% are benign, and an estimated 25% of malignant renal tumors have low metastatic potential and can be managed conservatively [3].

TABLE 1.

Basic Classification of Renal Cortical Tumors

| Cell Type | Occurrence (%) | General Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Clear cell | 75 | Aggressive |

| Papillary, types 1 and 2 | 10 | Type 1, nonaggressive; type 2, aggressive |

| Chromophobe | 8 | Nonaggressive |

| Unclassified (low) | < 5 | Nonaggressive |

| Other | < 5 | Variable |

There is increasing advocacy for close surveillance of renal cortical neoplasms in selected patients. Published data suggest that in patients of advanced age or with serious comorbid conditions, small malignant renal cell tumors of any histologic type can be managed conservatively with little change in overall survival or cancer-specific survival rate [3]. To date and to our knowledge, there is no established noninvasive method for definitive preoperative differentiation of renal cortical neoplasms. In addition, biopsy can be technically challenging, requiring an experienced pathologist, multiple core specimens, and potentially specialized histopathologic analyses for accurate diagnosis [4, 5].

Results of studies of Doppler ultrasound, contrast-enhanced CT, and MRI have suggested that vascularity and enhancement patterns differ among malignant renal tumor subtypes and benign tumors such as lipid-poor angiomyolipoma [6–10]. If histologic subtype can be predicted preoperatively with an acceptable level of accuracy, it may be possible to manage small suspected benign or indolent malignant renal cortical neoplasms conservatively [11, 12] and reserve surgical intervention for the more aggressive clear cell carcinoma, which has higher risk of metastasis [13–15].

Investigations have shown that contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEU) may have utility for evaluation of renal masses [7, 16–19]. Second-generation ultrasound microbubble contrast agents are composed of gas-filled lipid microspheres measuring approximately 3–5 μm in diameter that are injected IV. When exposed to low-energy ultrasound, the microspheres resonate and produce an acoustic signal that allows dynamic real-time visualization of tumor vasculature and enhancement characteristics [20]. Ultrasound contrast medium has potential advantages over CT and MRI contrast agents in that CEU agents remain intravascular without diffusing into the interstitial space, allow visualization of microvasculature, allow higher temporal resolution of ultrasound than of CT or MRI, and carry no known risk of nephrotoxicity or nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with renal dysfunction. This study was undertaken to determine whether CEU can be used to differentiate clear cell carcinoma from benign and low-grade malignant renal neoplasms.

Subjects and Methods

Patients

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this prospective study. From April 11, 2008, to August 11, 2010, 36 patients scheduled for surgery (n = 35) or biopsy (n = 1) for known renal masses were enrolled at the first visit to the genitourinary service. Patients were considered eligible if they had a renal mass that was evident with ultrasound and if they had no history of cardiac shunt. A contrast medium questionnaire was completed, and informed consent was obtained. All patients who met the entry criteria and who provided signed informed consent were included.

Imaging Technique

Conventional ultrasound

Conventional ultrasound images (Acuson Sequoia 512 machine, C-4 MHz or 4V1 transducers, Siemens Healthcare) were obtained by one of three radiologists to confirm the most appropriate imaging plane for ultrasound contrast imaging. Gray-scale, color, and power Doppler images were acquired before all CEU examinations. Typical Doppler settings were color Doppler mechanical index, 1.7; 2D mechanical index, 1.7–1.9; thermal index soft tissue at surface, 1.4–1.5; space time/edge, S1/–2; first trigger, T1/–2; color Doppler gain, 50; color Doppler energy, 20 dB).

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

The contrast agent (perflutren lipid microsphere, Definity, Lantheus Medical Imaging), a commercially available octafluoropropane contrast medium, was agitated in a manufacturer-provided activation device (VialMix, Lantheus Medical Imaging) and administered IV by hand microbolus with a total activated suspension of 0.2 mL (30 µL octafluoropropane) followed by a 10-mL normal saline flush with the option of administering the bolus four times.

All patients underwent a qualitative CEU examination. Patients who could suspend respiration for a minimum of 30 seconds were asked to do so during initial wash-in and washout. Slow, shallow breathing was allowed patients who had difficulty with a breath-hold. Images were obtained with the transducer held over the area of interest. Contrast boluses were recorded by cine acquisition for qualitative analysis (Cadence CPS, Siemens Healthcare), typically with dual, or split-screen, images, which simultaneously show separate low mechanical index gray-scale and contrast-only images. Continuous low mechanical index settings (< 0.24) were used, and power settings were below the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and drug manufacturer guidelines. Cine capture included early wash-in to peak (0–30 seconds) and late after peak (> 30 seconds). Cine capture clips were obtained from the time of bolus administration to 4 minutes after. Most of the cine clips were consecutive and of 2 minutes’ duration once it was established there was no measurable contrast signal more than 2 minutes after injection.

Twenty-two of 36 patients enrolled after proprietary software became available underwent quantitative CEU examinations. Autotracking contrast quantification mixed-mode imaging (ACQ, Siemens Healthcare) with an overlay mode of separate contrast (orange) and tissue (blue) signals was used for quantitative analysis with time-intensity curves. ACQ software is a patented pulse technology whereby data are separated from tissue data in real time, simultaneous contrast and tissue signal overlays are provided, and patient breathing motion is tracked [21]. Antilog settings were used for generation of time-signal curves.

The radiologist who performed the examination selected for analysis a region of interest (ROI) within the renal mass and within normal-appearing cortex. The area with greatest perceived intralesion visual enhancement (minimum size, 5 mm) was used for the ROI. The software also allows underlying background signal (in decibels) and backscatter by defining a user-designated time point (time 0). This step served as a control for any remaining circulating contrast before additional boluses.

Standard measurements included time to peak; peak intensity; arrival time; β, the rate constant of enhancement or wash-in, expressed in 1/s, equaling the time required for wash-in to 63% of total enhancement; and α, the difference between time 0 and the ultimate enhancement shown by the fitted antilog exponential curve. This step allowed semiquantitative comparison of lesion ROI with renal parenchymal ROI.

Image Interpretation and Analysis

Conventional and CEU images were digitally archived without unique patient identifiers. Images were reviewed in consensus by the three radiologists, who were blinded to other imaging findings and histopathologic results. The radiologists were experienced (5–33 years) in oncologic ultrasound imaging, but they had no CEU experience.

Standard gray-scale ultrasound review was conducted to document tumor size, echotexture, heterogeneity, presence and degree of Doppler flow (0, none; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; 4, marked). CEU studies were reviewed in consensus, and the bolus of best technical quality was selected for evaluation. Qualitative criteria for CEU lesion analysis included rapidity of enhancement in the arterial phase (< 30 seconds after injection) (0, after kidney; 1, same as kidney; 2, before kidney), vascular pattern (0, none; 1, dotlike; 2, penetrating; 3, peripheral; 4, mixed penetrating and peripheral), peak enhancement grade (0, none; 1, less than kidney; 2, same as kidney; 3, mildly greater than kidney; 4, markedly greater than kidney), washout immediately after renal peak enhancement (0, slower than kidney; 1, same as kidney; 2, faster than kidney), and heterogeneity of vasculature (0, uniform; 1, nodular; 2, heterogeneous) [19, 22].

Quantitative analysis data yielded time-enhancement graphs of the lesion ROI relative to the ROI of normal cortex. Rapidity of lesion enhancement in the arterial phase, peak enhancement in the lesion compared with normal kidney, and washout of contrast material relative to the kidney were recorded.

Pathologic Review

Histopathologic review was performed by a pathologist expert in renal tumors. Histologic characteristics of the lesion, grade if clear cell carcinoma, and size were confirmed. Percentage hyalinization and necrosis also were assessed for all clear cell carcinomas.

Statistical Analysis

An experienced reference statistician estimated measures of diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values) using pathologic findings as the diagnostic standard. The 95% CIs for these parameters were constructed with the exact distribution. Cutoff points for ordinal ratings were derived from receiver operating characteristic curves (not shown) by use of the point on the curve farthest from the diagonal. In an additional analysis, we combined lesion gray-scale heterogeneity and delayed contrast washout against either grayscale homogeneity or gray-scale heterogeneity with contrast washout similar to or greater than the kidney. We evaluated the resulting binary predictor using the methods described for the other analyses.

Results

Thirty-six renal masses in 36 patients (21 [62%] men; 13 [38%] women; age range, 44–80 years; mean, 58 years) were evaluated. Two technically suboptimal studies early in our experience were excluded; both had marked respiratory excursion, and one also had a poor contrast bolus. The other 34 neoplasms were analyzed. Nearly all patients received either two or three boluses with an average of 4 minutes between injections. There were no adverse reactions to contrast administration. Time between CEU and surgery or biopsy ranged from 2 to 41 days (mean, 11.6 days). Seventeen lesions were in the left kidney, and 17 were in the right. Lesion size ranged from 1.5 to 9.7 cm (mean, 3.8 cm; median, 3.45 cm). Twenty-three lesions were clear cell carcinoma; three, type 1 papillary renal cell carcinoma; one, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma; one, clear rare multilocular low-grade malignant tumor; two, unclassified; three, oncocytoma; and one, benign angiomyolipoma. The distribution of tumor histopathologic findings and sizes is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Histopathologic Features and Size of Renal Masses

| Histopathologic Finding | No. of Patients | Size Range (cm) | Mean Size (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clear cell carcinoma | 23 (67.6) | 1.5–9.7 | 3.7 |

| Papillary renal cell carcinoma | 3 (8.8) | 2.1–7 | 4.3 |

| Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma | 1 (2.9) | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Clear multilocular | 1 (2.9) | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Unclassified | 2 (5.9) | 1.9–4.1 | 3.0 |

| Oncocytoma | 3 (8.8) | 3.8–5 | 4.3 |

| Angiomyolipoma | 1 (2.9) | 3.2 | 3.2 |

Note—Values in parentheses are percentages.

Analysis of Conventional Ultrasound

Gray-scale features alone were of limited value for predicting the histologic type of the tumor. Eight of 23 clear cell tumors, one of three papillary tumors, the chromophobe tumor, and all three oncocytomas were hyperechoic. Most of the lesions were heterogeneous, including 20 of 23 (87.0%) clear cell carcinomas and 7 of 11 (63.6%) low-grade or benign tumors. The finding of intralesional blood flow at color and power Doppler imaging had no value for predicting the benign or malignant nature of a tumor. All clear cell carcinomas and 9 of 11 low-grade or benign tumors had intralesional blood flow at color and power Doppler imaging. The Doppler grade of vascularity was variable. Two of 23 clear cell carcinomas (8.7%) had marked flow, 17 of 23 (73.9%) had mild to moderate flow, and 4 of 23 (17.4%), including three high-grade tumors, had minimal or no flow at color and power Doppler examinations. Seven of the 11 low-grade malignant and benign tumors (63.6%) had minimal (five tumors) or no (two tumors) flow, but 4 of 11 (36.4%) had mild or moderate Doppler flow. There was no statistical correlation between lesion vascular pattern and lesion histologic features.

Qualitative Analysis of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound

The results of qualitative data analysis are summarized in Table 3. All lesions were enhancing after contrast administration. Delayed contrast washout compared with kidney was most frequently seen in clear cell carcinoma. Fourteen lesions had delayed contrast washout; 12 (85.7%) of these lesions were clear cell carcinoma, and the other two (14.3%) were oncocytomas. The combination of delayed contrast washout and gray-scale heterogeneity had a sensitivity of 48% (95% CI, 31–69%) and specificity of 82% (95% CI, 48–98%) for predicting conventional clear cell carcinoma rather than any other tumor with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 85% (95% CI, 2–98%) and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 43% (95% CI, 22–66%) (Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Qualitative and Quantitative Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Characteristics

| Characteristic | Clear Cell | Low-Grade Malignant | Benign |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative analysis | |||

| Total (n = 34) | 23 (67.6) | 7 (20.6) | 4 (11.8) |

| Rapidity of enhancement | |||

| After | 4 (17.4) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0) |

| Same as kidney | 16 (69.6) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (50) |

| Earlier | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) |

| Vascular pattern | |||

| Dotlike | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| Penetrating | 4 (17.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Peripheral | 1 (4.3) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) |

| Mixed penetrating and peripheral | 17 (73.9) | 6 (85.7) | 3 (75) |

| Enhancement grade | |||

| None or less than kidney | 2 (8.7) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (25) |

| Same as kidney | 11 (47.8) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (25) |

| Greater than kidney or marked | 10 (43.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) |

| Washout | |||

| After kidney | 12 (52.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) |

| Same | 6 (26.1) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (50) |

| Faster | 5 (21.7) | 3 (42.8) | 0 (0) |

| Vasculature heterogeneity | |||

| Uniform | 1 (4.3) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (25) |

| Nodular | 4 (17.4) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0) |

| Heterogeneous | 17 (73.9) | 5 (71.4) | 3 (75) |

| Inevaluable | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Quantitative analysis | |||

| Total (n = 21) | 16 (76.2) | 4 (19) | 1 (4.8) |

| Peak intensity | |||

| Greater than kidney | 12 (75) | 2 (50) | 1 (100) |

| Same as or less than kidney | 4 (25) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Time to peak | |||

| Greater than kidney | 9 (56.2) | 1 (25) | 1 (100) |

| Same as or less than kidney | 7 (43.8) | 3 (75) | 0 (0) |

| Rate constant wash-in | |||

| Greater than kidney | 8 (50) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Same as or less than kidney | 8 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (100) |

Note—Values in parentheses are percentages.

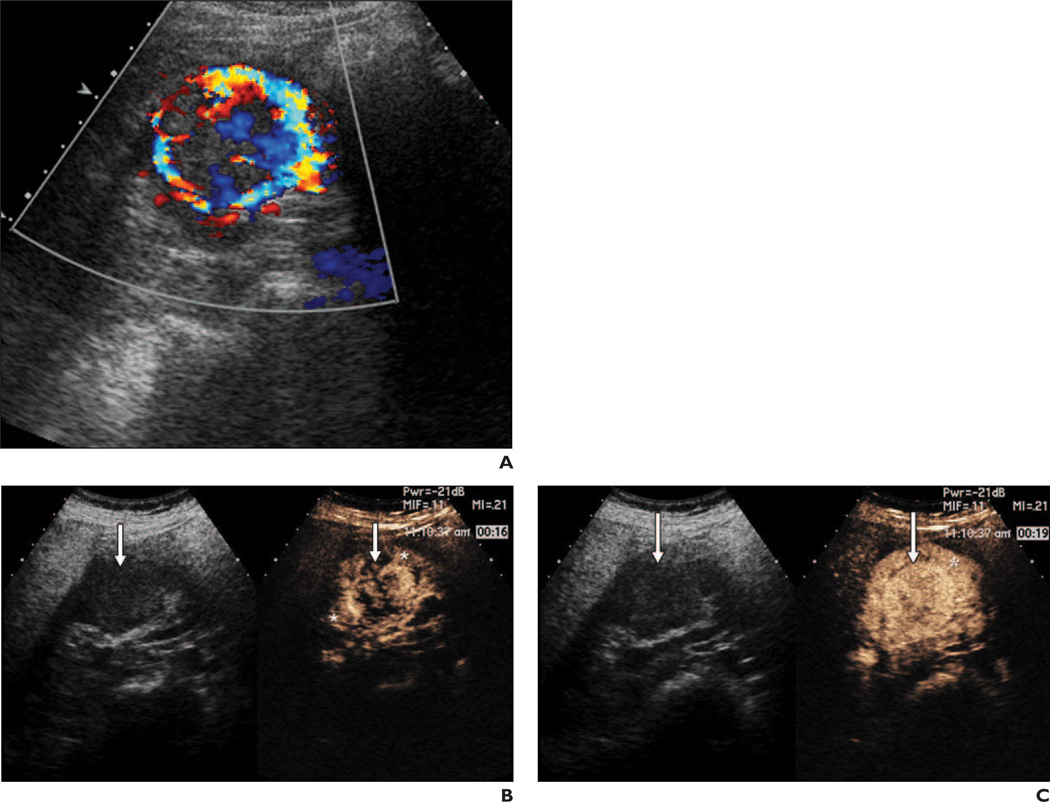

Fig. 1.

47-year-old woman with clear cell carcinoma. Postpeak hyperenhancement (delayed washout) was confirmed both visually and at quantitative analysis.

A, Color Doppler image shows heterogeneous 3.8-cm right renal mass with marked flow.

B, Split-screen ultrasound images from qualitative analysis (left, gray scale; right, contrast enhanced) obtained 16 seconds after contrast injection show heterogeneous lesion enhancement (arrows) of higher grade than that of adjacent renal parenchyma (asterisks). Early phase heterogeneous enhancement became uniform.

C, Split-screen qualitative analysis images 19 seconds after injection show closer to uniform lesion enhancement (arrows) and higher-grade enhancement than of adjacent kidney (asterisk).

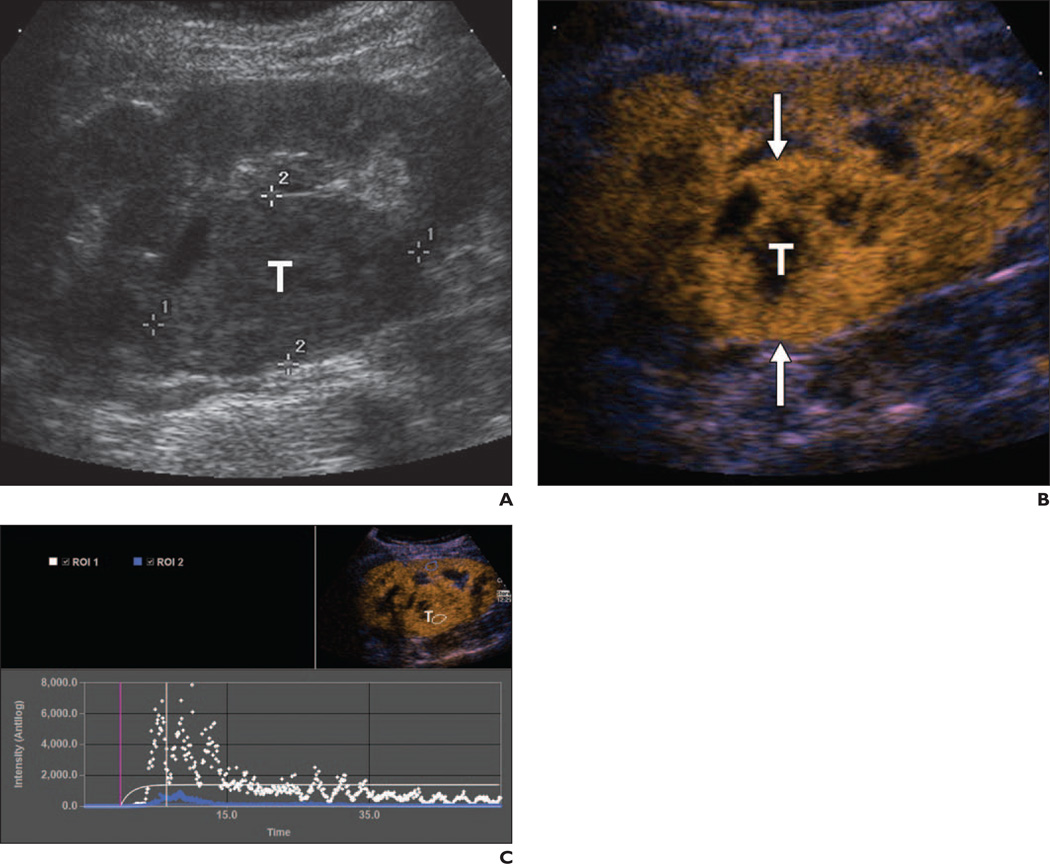

Fig. 2.

58-year-old woman with metastatic disease consistent with clear cell carcinoma of renal origin.

A, Gray-scale ultrasound image shows right renal heterogeneous 5-cm mass (T) projecting within central sinus fat.

B, Autotracking contrast quantification mixed-mode image obtained immediately after renal peak shows moderate to marked heterogeneous lesion enhancement (T) compared with adjacent kidney and relative lack of washout. Arrows indicate lesion.

C, Time-enhancement curve confirms qualitative visual findings. Tumor (T) data points (white) show higher peak of enhancement with relative lack of washout after renal peak (blue) in corticomedullary phase. ROI = region of interest.

TABLE 4.

Summary of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Findings

| Lesion Characteristics | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive of clear cell carcinoma | ||||

| Heterogeneous and lack of washout | 48 | 82 | 85 | 43 |

| Hyperenhancement grade ≥ 3 | 43 | 82 | 83 | 41 |

| Lesion/kidney peak intensity ≥ 0.2 | 94 | 40 | 83 | 67 |

| Lack of washout and lesion/kidney peak intensity ≥ 0.2 | 63 | 80 | 91 | 40 |

| Predictive of non–clear cell tumor | ||||

| Diminished enhancement grade | 55 | 91 | 75 | 81 |

| Predictive of papillary or chromophobe subtype | ||||

| Diminished enhancement grade | 75 | 83 | 28 | 96 |

Contrast enhancement less than that of the kidney was useful for predicting whether a tumor was indolent or benign (Fig. 3). Eight of 34 (23.5%) lesions were hypoenhancing; six of these were low-grade indolent or benign tumors, and two were clear cell carcinoma. Both of the clear cell carcinomas that had diminished lesion enhancement had histopathologic evidence of 16% or greater hyalinization or necrosis. The percentage of combined hyalinization and necrosis within tumors was not significantly associated with lesion size.

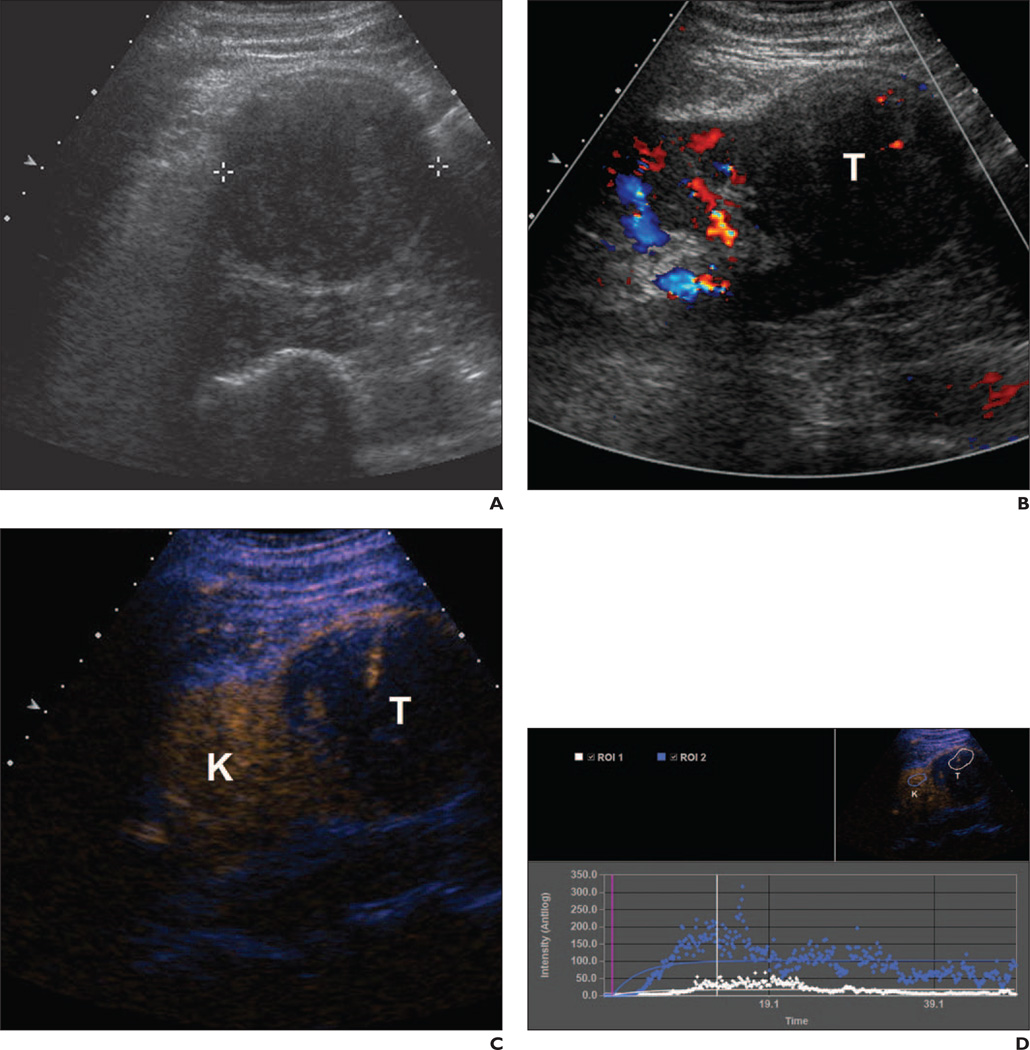

Fig. 3.

54-year-old man with 7.0-cm right renal papillary carcinoma.

A, Gray-scale image shows minimally heterogeneous 7-cm mass (calipers).

B, Color Doppler image shows lesion (T) has confirmed minimal flow.

C, Autotracking contrast quantification mixed-mode imaging shows minimal lesion (T) enhancement compared with adjacent renal parenchyma (K).

D, Time-enhancement curve confirms qualitative findings. Lesion (T) data points (white) show minimal enhancement compared with renal parenchymal (K) data points (blue).

Contrast enhancement greater than that of the kidney was seen in 12 renal masses; 10 (83.3%) were clear cell carcinoma and two (16.7%) were benign oncocytoma. Moderate to marked (rank ≥ 3) enhancement grade alone had a sensitivity of 43% (95% CI, 34–66%), specificity of 82% (95% CI, 48–98), PPV of 83% (95% CI, 2–98%) and NPV of 41% (95% CI, 21–64%) for predicting clear cell histologic features (Table 4). For clear cell carcinoma, there was correlation (p = 0.013) between size and enhancement grade, hypervascular (rank ≥ 3) tumors having a mean size of 4.6 cm compared with all others (mean size, 3.0 cm).

Rapidity of enhancement and vascular pattern were noncontributory for predicting histologic type. Most of the tumors (16 of 23, 69.6%) were clear cell carcinoma. Seven of 11 (63.6%) low-grade malignant or benign lesions had an enhancement time more rapid than or similar to that of normal kidney. A mixed peripheral and penetrating vascular pattern was most common for tumors of any histologic type, being found in 17 of 23 (73.9%) renal cell carcinomas and 9 of 11 (81.8%) indolent or benign masses. One of the three oncocytomas had a spoke-wheel pattern of enhancement at CEU but not at color or power Doppler analysis.

Quantitative Analysis

The results of quantitative data analysis are summarized in Table 3. Rate constant wash-in and time to peak alone were noncontributory. Peak intensity greater than kidney was most frequently encountered in clear cell carcinoma, but elevated peak intensity alone was not sufficiently predictive because there was overlap with benign and indolent tumors. Quantitative analysis showed 15 of 21 lesions had peak intensity greater than kidney; 12 of the 15 (80%) were clear cell carcinoma, and three (20%) were low-grade malignant or benign tumors, including one oncocytoma, one unclassified partial oncocytic low-grade malignant tumor, and one clear rare multilocular low-grade tumor.

It is noteworthy that all four clear cell carcinomas with peak intensity less than that of the kidney had greater than 16% necrosis or hyalinized tumor components. In contradistinction, this degree of hyalinization or necrosis was infrequent, seen in only 2 of 12 clear cell carcinomas with peak intensity greater than that of the kidney.

As shown in Table 4, the greatest sensitivity for prediction of clear cell carcinoma was achieved when quantitative lesion peak intensity was at least 20% that of kidney peak intensity, but this finding was not specific. Specificity improved when lesion/kidney peak intensity of 20% or more was combined with delayed lesion washout, showing 63% sensitivity, 80% specificity, 91% PPV, and 40% NPV (Table 4) in prediction of clear cell histologic type.

Comparison of Results of Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses

There was concordance and high agreement between the results of qualitative and quantitative analyses of lesions enhancing differently from kidney. For all tumors deemed at qualitative analysis to be enhancing either less than or greater than the kidney, kappa agreement with lesion versus kidney peak intensity at quantitative analysis was 0.806 (95% CI, 0.448–1.000), only 1 of 13 cases (7.7%) being discordant. This discordant case was a clear cell carcinoma with high-grade enhancement and suspected cystic change at visual analysis, but lesion peak intensity was less than kidney intensity at quantitative analysis. Histopathologic examination confirmed 20% hyalinization.

In contradistinction, quantitative analysis provided additional information when lesion enhancement appeared similar to renal enhancement at qualitative analysis. Six of eight masses with a qualitative enhancement grade similar to that of the kidney had a greater than 30% difference between lesion peak intensity and kidney peak intensity at quantitative analysis. These cases included five clear cell carcinomas, four of which had lesion peak intensity more than 30% greater than that of the kidney.

Discussion

Renal masses are being detected more frequently with increased use of cross-sectional imaging. Nephrectomy or nephron-sparing partial nephrectomy is performed for these renal tumors, but as many as 30% of the lesions prove benign, and another 25% are low-grade malignant tumors, which generally have less metastatic potential than does clear cell renal carcinoma [1]. For these reasons, there is increased interest in preoperative prediction of renal mass subtype. Although previous studies [23–25] have shown added value of CEU compared with contrast-enhanced CT in the evaluation of complex renal cystic neoplasms, published data on CEU evaluation of solid renal masses have been conflicting [7, 17, 19]. Variations in scanner hardware and software and contrast agents and ultimately varying approaches to findings, including lack of clear definitions of interpretation of results and time frames, have increased the difficulty of clinical translation of CEU to assessment of renal masses.

In our prospective study, we evaluated the utility of CEU in improved prediction of the histologic features of solid renal masses and found that diminished enhancement grade had high NPV (96%), good specificity (83%), and fair sensitivity (75%) for predicting whether a lesion was a tumor.

Our findings are concordant with those of previous investigations in which investigators observed less avid enhancement of lower-grade malignant tumors (non–clear cell subtypes) [17, 26], likely corresponding to less microvessel density in lower-grade lesions [26]. In a qualitative study of 33 solid lesions (seven clear cell carcinomas, 14 papillary tumors), Roy et al. [17] used a sulfur hexafluoride blood-pool agent (SonoVue, Bracco) similar to the contrast agent we used and found that 13 of the 14 papillary tumors had less avid enhancement of the kidney and slow progressive delayed enhancement after initial wash-in. We believe that the cohort in that study exhibited selection bias in that most of the tumors were not markedly enhancing on contrast-enhanced CT or MR images and that nearly 67% of the malignant tumors were papillary carcinoma. Our study included quantitative analysis and was prospective without selection bias, but we also confirmed that low-grade malignant renal neoplasms exhibit decreased contrast enhancement.

The utility of CEU in predicting whether a lesion has benign histologic features is limited by hyperenhancement of oncocytoma. Two of three oncocytomas were hyperenchancing and had delayed lesion washout. These findings are similar to those of Roy et al. [17]. Fan et al. [7] and Haendl et al. [27] also observed hyperenhancement in oncocytomas, but the marked washout described in their reports differed from the delayed washout seen in our two hyperenhancing oncocytomas. Angiomyolipoma also reportedly has variable enhancement [5, 18]. Only one of our patients had angiomyolipoma, which was muscle predominant at histopathologic analysis and was both hypoenhancing and homogeneous.

We found variable enhancement patterns of clear cell carcinoma, as described in previous reports [18, 27]. Hyperenhancement was more frequent in clear cell carcinoma, but the finding lacked specificity. Fourteen of 23 (60.9%) clear cell carcinomas were hyperenhancing at either qualitative or quantitative analysis compared with 4 of 15 (26.7%) benign or indolent tumors. One oncocytoma had a clear central scar and spoke-wheel pattern of enhancement and persistent avid enhancement on delayed (> 60 seconds) images. Our findings suggest that the presence of hypervascularity alone in the absence of a central scar or spoke-wheel enhancement pattern should raise suspicion of clear cell carcinoma; 14 of 17 (82.4%) tumors with these characteristics were conventional clear cell cancer, and 6 of the 10 were high-grade tumors.

Washout characteristics have been found useful because renal cell carcinoma often exhibits delayed washout compared with normal kidney [7, 17, 18, 27, 28]. Our findings support this observation because 52% of clear cell carcinomas had delayed washout at qualitative analysis whereas only 18% of benign or low-grade indolent tumors had delayed washout. Both of the benign lesions with delayed contrast washout were oncocytoma. In our experience, octafluoropropane with its relatively short half-life (90 seconds) had diminished bubble intensity after approximately 2 minutes, and the greatest differences in washout were apparent within 30 seconds after renal parenchymal peak enhancement.

Although marked enhancement or delayed washout was associated with clear cell carcinoma, these factors alone were not sufficiently predictive unless combined with other features, such as gray-scale heterogeneity and peak intensity. We found that a combination of heterogeneity, likely from components of necrosis or fibrosis, combined with delayed postpeak lesion washout (Figs, 1, 2, and 4 and Table 4) had 82% specificity and 85% PPV for conventional clear cell carcinoma, regardless of peak intensity, and was specific but not sensitive (Table 4). Sensitivity (63%) and PPV (91%) improved with the combination of lack of washout and lesion peak intensity at least 20% of quantitative analysis; specificity (80%) was maintained.

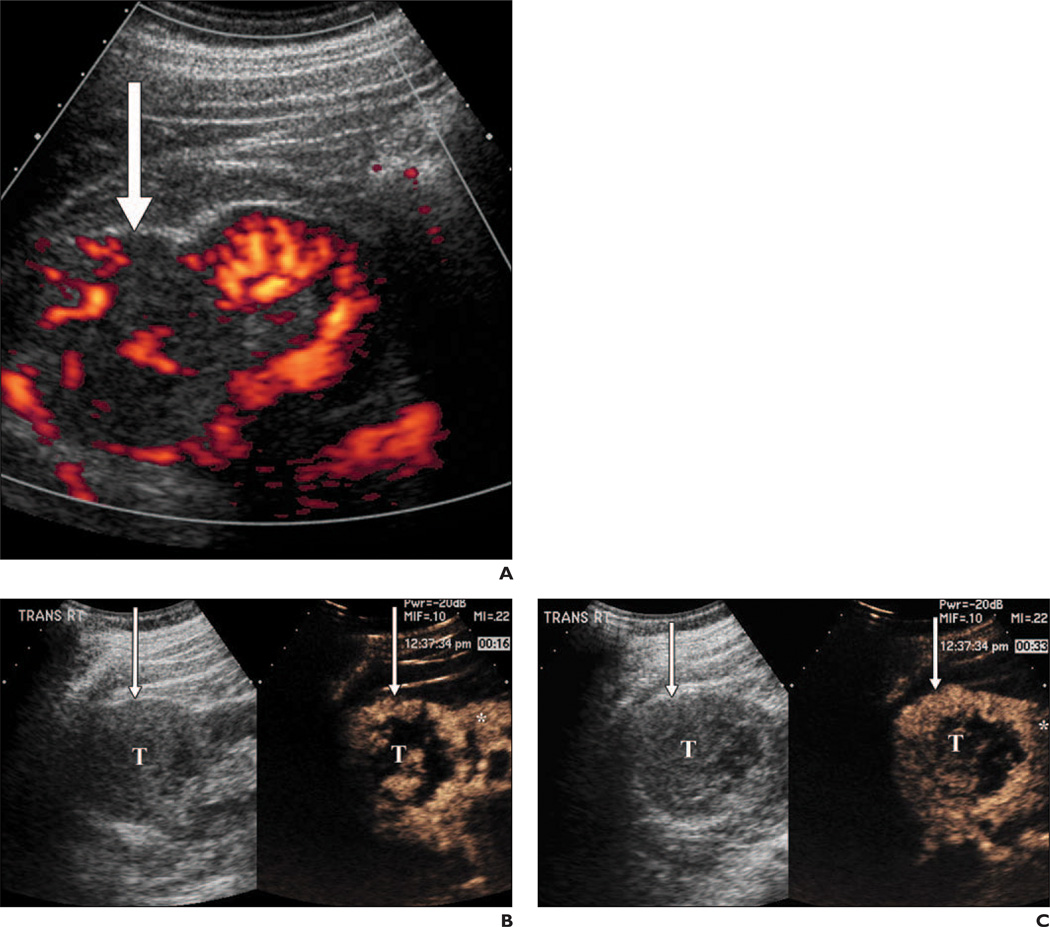

Fig. 4.

60-year-old man with 6.8-cm right renal clear cell carcinoma.

A, Power Doppler image shows heterogeneous exophytic solid mass (arrow) with confirmed internal flow.

B, Qualitative split-screen gray-scale (left) and contrast-enhanced (right) images obtained 16 seconds after contrast injection shows nodular mixed penetrating and peripheral heterogeneous enhancement (arrows) within tumor (T) that is greater than enhancement of kidney (asterisk).

C, Split-mode screen qualitative analysis image obtained 33 seconds after contrast injection, after renal peak, shows lesion (T) has continued higher grade of contrast enhancement (arrows) than adjacent rim of normal renal parenchyma (asterisk), constituting lack of lesion washout.

Data from Fan et al. [7] on contrast pulse sequence imaging with an aqueous suspension of phospholipid-stabilized microbubbles filled with sulfur hexafluoride (Sonovue, Bracco) showed hyperenhancement, defined as a greater than 0.4555-dB difference in the late phase, and 96% sensitivity and 77% specificity in the diagnosis of any renal cell carcinoma. In that study, all late-phase hyperenhancing lesions were clear cell carcinoma; none of the five papillary or chromophobe tumors were hyperenhancing in any phase. Importantly, Fan et al. defined the late phase as 30–90 seconds after agent injection, which we defined as the postpeak phase. Xu et al. [29] conducted a study with 97 patients using the same imaging technique and agent but evaluated washout later in the nephrographic phase. They found washout combined with heterogeneity and a peritumoral rim highly suggestive of renal cell carcinoma. The half-life of SonoVue is 6 minutes, and the evaluation by Xu et al. of washout at a later time point may account for the apparent discrepancy of findings.

The variable CEU enhancement of renal cell carcinoma in our study differs from the findings of Fan et al. [7]. It is similar, however, to the finding by Haendl et al. [27] of variable early and late CEU enhancement of renal cell carcinomas with SonoVue. Similarly, Tamai et al. [18] conducted a prospective study of qualitative CEU with the galactose-based microbubble agent SH U 508A (Levovist, Schering) and an older method of grayscale contrast imaging (Sie Flow, Siemens Healthcare) of 29 patients with solid renal masses. They found that CEU had 94% sensitivity but low specificity in the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma. Our findings and those in the other reports [17, 18] differ from the results of Siracusano et al. [28]. Using Levovist CEU with intermittent high-powered pulse imaging and quantitative analysis to evaluate 23 renal masses, those investigators found that all clear cell carcinomas had distinct hypervascular enhancement compared with other tumors in all phases of imaging. Tamai et al. and Siracusano et al. used less advanced contrast imaging sequences, different from the current state-of-the-art continuous low mechanical index technology.

Hypoenhancing clear cell tumors present a challenge in CEU. In our study 25% of clear cell carcinomas had lesion peak intensity less than kidney peak intensity. Other investigators [7, 19, 27] have reported similar findings of hypoenhancement ranging from 10% to 38% of cell clear cell carcinomas. In a study of pathologic specimens of renal cell carcinoma, Imao et al. [30] observed that microvessel density was decreased in larger renal cell carcinomas. In our study we found that hypovascular clear cells (lesion peak intensity less than kidney peak intensity) had variable sizes but greater degrees of hyalinization and necrosis.

To our knowledge, ours is the first clinical prospective CEU study of the use of quantitative analysis to compare histopathologic degrees of necrosis and hyalinization and to compare these findings with contrast enhancement patterns. In our cohort, all four clear cell carcinomas with lesion peak intensity less than kidney peak intensity had 16% or greater combined necrosis or fibrosis at histopathologic examination. One of these carcinomas was graded hypervascular at qualitative analysis but hypovascular at quantitative analysis. Only 2 of 12 clear cell carcinomas with lesion peak intensity greater than kidney peak intensity had greater than 16% necrosis and hyalinization. In our experience, areas of hyalinization or necrotic change within a tumor can limit both quantitative and qualitative analysis of enhancement unless careful attention is paid to evaluation and sampling from the viable rim of an active tumor.

Strong kappa agreement between results of visual qualitative and semiquantitative analyses of all lesions noted as hypoenhancing or hyperenhancing suggests that quantitative analysis may have limited added value in this subset and may be restricted to use only in cases in which lesion enhancement appears similar to kidney enhancement to uncover differences that may be less obvious at visual inspection.

Our study was limited by the small sample size and relatively small percentage of indolent and benign tumors, only 34% of our sample, compared with the estimated 45% expected from national statistics [1]. The results also might have been influenced by level of experience with contrast administration. The radiologists in this study had no experience with CEU, and this factor contributed to the exclusion of two patients because of inadequate contrast enhancement and patient motion. Our learning curve was such that our ability to perform and interpret CEU studies improved in the later phases of the study as we gained experience. Because of our lack of CEU experience, we elected to perform readings in consensus, and therefore intraobserver and interobserver variability were not assessed. Another limitation was that quantitative analysis was performed for only 62% of patients because the proprietary software for quantitative analysis was not available in the initial phase of the study. In addition, because this was a pilot study, we did not compare CEU with CT or MRI findings. This comparison should be a focus of future research.

Our pilot data suggest that CEU has utility in the preoperative assessment of indolent and benign renal tumors that may be appropriate for conservative management in patients of advanced age or with comorbid conditions. Prediction of the histologic type of renal cell carcinoma with CEU is difficult owing to varying enhancement patterns, some of which are related to histologic evidence of hyalinization and necrosis within these tumors.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Graham Family Foundation.

We thank Carola Heneweer and Rachel Kronman for their assistance.

References

- 1.Reuter VE, Presti JC Jr. Contemporary approach to the classification of renal epithelial tumors. Semin Oncol. 2000;27:124–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman HP, Middleton WD, Melson GL, McClennan BL. Hyperechoic renal cell carcinomas: increase in detection at US. Radiology. 1993;188:431–434. doi: 10.1148/radiology.188.2.8327692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volpe A, Jewett MA. The role of surveillance for small renal masses. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007;4:2–3. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volpe A, Jewett MA. Current role, techniques and outcomes of percutaneous biopsy of renal tumors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:773–783. doi: 10.1586/era.09.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasudevan A, Davies RJ, Shannon BA, Cohen RJ. Incidental renal tumours: the frequency of benign lesions and the role of preoperative core biopsy. BJU Int. 2006;97:946–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun MR, Ngo L, Genega EM, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging for differentiation of tumor subtypes—correlation with pathologic findings. Radiology. 2009;250:793–802. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2503080995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan L, Lianfang D, Jinfang X, Yijin S, Ying W. Diagnostic efficacy of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in solid renal parenchymal lesions with maximum diameters of 5 cm. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:875–885. doi: 10.7863/jum.2008.27.6.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Lefkowitz R, Ishill N, et al. Solid renal cortical tumors: differentiation with CT. Radiology. 2007;244:494–504. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2442060927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JK, Kim TK, Ahn HJ, Kim CS, Kim KR, Cho KS. Differentiation of subtypes of renal cell carcinoma on helical CT scans. AJR. 2002;178:1499–1506. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.6.1781499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raj GV, Bach AM, Iasonos A, et al. Predicting the histology of renal masses using preoperative Doppler ultrasonography. J Urol. 2007;177:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen MM, Gill IS. Effect of renal cancer size on the prevalence of metastasis at diagnosis and mortality. J Urol. 2009;181:1020–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.023. discussion 1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson RH, Kurta JM, Kaag M, et al. Tumor size is associated with malignant potential in renal cell carcinoma cases. J Urol. 2009;181:2033–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li G, Cuilleron M, Gentil-Perret A, Tostain J. Characteristics of image-detected solid renal masses: implication for optimal treatment. Int J Urol. 2004;11:63–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russo P. Localized renal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2001;2:447–455. doi: 10.1007/s11864-001-0050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beisland C, Hjelle KM, Reisaeter LA, Bostad L. Observation should be considered as an alternative in management of renal masses in older and comorbid patients. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1419–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson SR, Burns PN. Microbubble-enhanced US in body imaging: what role? Radiology. 2010;257:24–39. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy C, Gengler L, Sauer B, Lang H. Role of contrast enhanced US in the evaluation of renal tumors. J Radiol. 2008;89:1735–1744. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(08)74478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamai H, Takiguchi Y, Oka M, et al. Contrastenhanced ultrasonography in the diagnosis of solid renal tumors. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:1635–1640. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.12.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang J, Chen Y, Zhou Y, Zhang H. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: contrast-enhanced ultrasound features relation to tumor size. Eur J Radiol. 2010;73:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernot S, Klibanov AL. Microbubbles in ultrasound- triggered drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1153–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips P, Gardner E. Contrast-agent detection and quantification. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(suppl 8):P4–P10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jinzaki M, Ohkuma K, Tanimoto A, et al. Small solid renal lesions: usefulness of power Doppler US. Radiology. 1998;209:543–550. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.2.9807587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clevert D, Minaifar N, Weckbach S, et al. Multislice computed tomography versus contrast-enhanced ultrasound in evaluation of complex cystic renal masses using the Bosniak classification system. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2008;39:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quaia E, Bertolotto M, Cioffi V, et al. Comparison of contrast-enhanced sonography with unenhanced sonography and contrast-enhanced CT in the diagnosis of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses. AJR. 2008;191:1239–1249. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ascenti G, Mazziotti S, Zimbaro G, et al. Complex cystic renal masses: characterization with contrast- enhanced US. Radiology. 2007;243:158–165. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431051924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jinzaki M, Tanimoto A, Mukai M, et al. Double-phase helical CT of small renal parenchymal neoplasms: correlation with pathologic findings and tumor angiogenesis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:835–842. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haendl T, Strobel D, Legal W, Frieser M, Hahn EG, Bernatik T. Renal cell cancer does not show a typical perfusion pattern in contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2009;30:58–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siracusano S, Quaia E, Bertolotto M, Ciciliato S, Tiberio A, Belgrano E. The application of ultrasound contrast agents in the characterization of renal tumors. World J Urol. 2004;22:316–322. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu ZF, Xu HX, Xie XY, Liu GJ, Zheng YL, Lu MD. Renal cell carcinoma and renal angiomyolipoma: differential diagnosis with real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:709–717. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.5.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imao T, Egawa M, Takashima H, Koshida K, Namiki M. Inverse correlation of microvessel density with metastasis and prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol. 2004;11:948–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]