Abstract

Background

Chronic infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality. While recent advances in antiviral therapy have led to significant improvements in treatment response rates, only a minority of infected patients is treated. Multiple barriers may impede the delivery of HCV therapy.

Aim

To identify perceived barriers to care, knowledge, and opinions among a global sample of HCV treatment providers.

Methods

An international, multidisciplinary survey of HCV treatment providers was conducted. Each physician responded to a series of 214 questions concerning his or her practice characteristics, opinions regarding the state of HCV care, knowledge regarding HCV treatment, and perception of treatment barriers.

Results

697 physicians from 29 countries completed the survey. Overall, physicians viewed patient-level barriers as most significant, including fear of side effects and concerns regarding treatment duration and cost. There were distinct regional variations, with Central and Eastern European physicians citing government barriers as most important. In Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa, payer-level barriers, including lack of treatment coverage, were prominent. Overall, the perception of barriers was strongly associated with physician knowledge, experience, and region of origin, with the fewest barriers reported by Nordic physicians and the most reported by Middle Eastern and African physicians. Globally, physicians demonstrated deficits in basic treatment principles, including the role of viral kinetics and the management of treatment non-responders. Two-thirds of surveyed physicians believed that patients do not have adequate access to providers in their community.

Conclusion

Barriers to HCV treatment vary globally, though patient-level factors are viewed as most significant by treating physicians. Efforts to improve awareness, education, and specialist availability are needed.

Keywords: Hepatitis C/therapy, health services accessibility, health care surveys, physician’s practice patterns, delivery of health care

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection affects between 130 million and 170 million persons worldwide, is a leading indication for liver transplantation, and contributes to 350,000 deaths each year.(1) HCV is a potentially curable disease, with the majority of treated patients now afforded the promise of a sustained virologic response (SVR).(2–5) Unfortunately, less than half of HCV infected persons are aware of their diagnosis, and among those with known infection, only 1% to 30% will receive treatment.(6–11)

Multiple factors serve as impediments to the delivery of antiviral therapy. These barriers may arise at the patient, provider, payer, and/or government level.(12) Patients cite fear of treatment-related side effects, lack of symptoms, financial constraints, and social stigmatization as primary reasons for declining therapy.(13–16) Physicians may fail to refer patients for subspecialty evaluation or may place undue emphasis on purported contraindications.(17) As a result, more than 70% of patients are deemed ineligible for treatment based on psychiatric disease, substance use, or medical comorbidities,(6, 7) despite evidence that these factors are not absolute.(18, 19) A lack of available and competent specialists may further interfere.(20, 21) Finally, limitations in funding, medical coverage, and office staffing may prevent treatment.(11, 22)

Increasingly, hepatitis C is recognized as a global health crisis, demanding an international, coordinated emphasis on promotion, prevention, and treatment.(23) To inform these initiatives, we surveyed an international sample of HCV treatment providers, with a goal of assessing knowledge, opinions toward HCV therapy, and perceived barriers to care.

Methods

An international, mixed-mode survey study of HCV treatment providers was conducted in December 2010 with an aim to identify physician and practice characteristics, opinions regarding HCV care, knowledge of treatment principles, and perceived barriers to care. A 214-item questionnaire was developed by the International Conquer C Coalition (IC3), an organization of hepatitis C experts formed with the goal of optimizing global HCV care. The questionnaire was piloted by a 67-member focus group of IC3 members. Physicians were considered eligible for the study if they treated a minimum of 10 HCV patients each month and if they resided in one of the 8 predetermined global regions: United States, Canada, Latin America, Western Europe, Central/Eastern Europe, Nordic, Asia/Pacific, and Middle East/Africa. Target respondents included hepatologists, gastroenterologists, infectious disease physicians, internists, and general practitioners. The survey was distributed to a sample of 1400 physicians identified via an international market research database(24) and was administered by 25-minute phone interview or internet based format by a professional survey company (Phoenix Marketing International, Rhinebeck NY). Participants were asked a series of open-ended, multiple-response, and Likert scale questions. Translation was provided for non-English speaking participants. Each participant received a modest honorarium for completing the survey. All responses were anonymous.

Physician/Practice Characteristics and Opinions Regarding HCV Care

Each physician was asked about his or her medical specialty, practice location, patient volume, and patient characteristics. Opinions regarding the current state of HCV care were assessed according to level of agreement with the following statements: (1) national treatment guidelines are available in my country; (2) treatment guidelines and policies are consistent among professional societies, payers, and government; (3) government and/or payers recognize national or international treatment guidelines; (4) healthcare providers have knowledge of screening and treatment guidelines; (5) the general public is aware of HCV; (6) patients understand the consequences of HCV if it is not treated; (7) most patients are aware that HCV is curable; (8) patients have adequate access to HCV providers in their community; responses were rated on a 10-point Likert scale, with 0 representing “strongly disagree,” 5 “neither agree nor disagree,” and 10 “strongly agree.”

Knowledge

Physician knowledge was assessed according to level of agreement with the following eight statements: (1) the addition of ribavirin to peginterferon improves the likelihood of SVR; (2) maintaining an optimal dose of ribavirin with interferon is necessary to achieve an SVR; (3) different viral genotypes require different treatment durations; (4) treatment should be discontinued for patients who fail to achieve a 2-log decrease in HCV RNA by treatment week 12; (5) treatment should be discontinued for patients who have detectable HCV RNA at treatment week 4; (6) patients with stage 1 fibrosis have worse treatment outcomes than patients with stage 4 fibrosis; (7) the level of HCV RNA has no correlation with the severity of liver disease; (8) maintenance therapy should be prescribed for treatment non-responders. Each response was rated on a 10-point Likert scale, with 0 representing “strongly disagree,” 5 representing “neither agree nor disagree,” and 10 representing “strongly agree.”

Barriers to Care

The main focus of this study was to assess perceived barriers to HCV care. Each respondent was presented with 31 potential barriers categorized by patient, provider, government, and payer related categories (Table I). Responses were based on a 10-point Likert scale, with 0 representing “not a barrier to treatment,” 5 representing “somewhat of a barrier to treatment,” and 10 representing “large barrier to treatment.”

Table 1.

Perceived Barriers to HCV Treatment

| Patient-related |

|---|

|

| Government-related |

|

| Provider-related |

|

| Payer-related |

|

All barriers scored on a 10-point Likert scale, with 0 representing “not a barrier to treatment,” 5 representing “somewhat of a barrier to treatment,” and 10 representing “large barrier to treatment”

Statistical Analysis

The mean, range, standard deviation, and shape of the distribution were examined for each continuous variable, with frequencies tabulated for each categorical variable. Physician and practice characteristics were compared across global regions using Pearson’s Chi-square test for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. Bivariable analysis was used to examine the relationship between physician/practice characteristics and perceived barriers to care, using Pearson’s correlation analysis for continuous independent variables and one-way analysis of variance for each categorical independent variable. Multiple linear regression was used to identify characteristics independently associated with perceived barriers to care. All analyses were performed using Stata 11 (College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 697 physicians were surveyed across 8 global regions, representing 29 individual countries (Supplemental material: Figure I). The overall response rate was 50%. Physician and practice characteristics are summarized in Table II. Overall, physicians were in practice for a mean of 16 years and treated an average of 46 HCV patients each month (range: 5 to 500 patients). Physician specialty varied by region, with HCV care more commonly provided by hepatologists and gastroenterologists in the United States and Western Europe, by infectious disease specialists in Central/Eastern Europe, and by internists or general practitioners in remaining regions. Physicians most frequently worked in a private, urban facility, though a government-affiliated practice was most common in Central/Eastern Europe and Nordic regions. Dedicated treatment nurses and/or assistants were more frequently employed in European countries. Source of medical coverage varied significantly, with patients in Europe, Canada, and Asia/Pacific regions covered primarily by public insurance. A mix of public and private coverage was seen in the United States and Latin America. More than one-third of patients in the Middle East and Africa were reportedly uninsured. Overall, approximately one-quarter of patients were reported to refuse therapy, with the highest refusal rate in Asia/Pacific countries and the lowest in Nordic countries (37% vs. 14%, p<.0001).

Table 2.

Physician and Practice Characteristics By Global Region

| Characteristic Mean (SD) or % | United States (n=102) | Canada (n=30) | Latin America (n=100) | Western Europe (n=103) | Central/Eastern Europe (n=101) | Nordic (n=52) | Asia/Pacific (n=108) | Middle East/Africa (n=101) | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years in Practice | 12 (8) | 17 (10) | 18 (9) | 16 (8) | 21 (8) | 20 (8) | 13 (8) | 13 (6) | 16 (8) |

|

| |||||||||

| Specialty | |||||||||

| Hepatology | 18 | 10 | 9 | 43 | 10 | 17 | 26 | 8 | 19 |

| GI | 35 | 23 | 32 | 32 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 25 |

| ID | 24 | 33 | 17 | 15 | 58 | 40 | 25 | 21 | 28 |

| IM/GP | 23 | 33 | 42 | 10 | 12 | 24 | 30 | 53 | 28 |

|

| |||||||||

| Practice Location | |||||||||

| Urban | 68 | 87 | 98 | 90 | 88 | 96 | 86 | 80 | 86 |

| Rural/Suburban | 32 | 13 | 2 | 10 | 12 | 4 | 14 | 20 | 14 |

|

| |||||||||

| Practice Type | |||||||||

| Private | 57 | 56 | 63 | 19 | 21 | 21 | 48 | 56 | 43 |

| University | 36 | 40 | 5 | 49 | 25 | 35 | 25 | 9 | 26 |

| Government | 2 | 0 | 26 | 29 | 43 | 40 | 25 | 32 | 26 |

| Other | 5 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

|

| |||||||||

| Dedicated HCV Nurses/Assistants | 47 | 53 | 40 | 70 | 67 | 76 | 40 | 47 | 53 |

|

| |||||||||

| HCV Patients Seen Monthly | 64 (79) | 36 (39) | 35 (61) | 58 (54) | 55 (69) | 24 (19) | 35 (36) | 44 (43) | 46 (57) |

|

| |||||||||

| Patient Coverage | |||||||||

| Public | 42 | 71 | 52 | 83 | 85 | 86 | 60 | 25 | 61 |

| Private | 46 | 24 | 33 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 21 | 38 | 23 |

| Uninsured | 12 | 5 | 15 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 19 | 37 | 16 |

|

| |||||||||

| Patients Declining Therapy | 25 | 29 | 23 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 37 | 23 | 22 |

|

| |||||||||

| Patients stopping therapy after initiation | 25 | 19 | 19 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 24 | 13 | 17 |

GI, gastroenterology; ID, infectious disease; IM/GP, Internal Medicine/General Practitioner; RN, Registered Nurse; SD, standard deviation; HCV, hepatitis C virus

Opinions Regarding HCV Care

Physician opinions regarding the current state of HCV care are shown in Table III. The majority of physicians indicated that national treatment guidelines existed in their country; however, less than half felt that guidelines were consistent across sources. Only 36% to 38% of physicians in North America, Latin America, and Middle East/Africa believed that government and/or payers recognized treatment guidelines, compared to 71% to 83% in European countries. Between 20% and 54% of respondents felt that healthcare providers have adequate knowledge of HCV guidelines, with higher levels of agreement across European countries. Globally, less than one-quarter of physicians felt that the general public is aware of HCV and know that it is a curable disease. Only 35% of all surveyed physicians believed that patients have adequate access to HCV treatment providers, with the lowest percentage in the United States (17%) and the highest in Nordic countries (62%).

Table 3.

Physician OpinionsRegardingCurrent HCV Care

| Statement | % Of Respondents in Agreement with Statement* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | CAN | LAT | WE | CEE | NOR | AP | MEA | Overall | |

| National treatment guidelines are available in my country | 57 | 60 | 46 | 85 | 81 | 86 | 57 | 31 | 62 |

|

| |||||||||

| Treatment guidelines/policies are consistent among professional societies, payers, and government | 30 | 23 | 28 | 59 | 58 | 75 | 44 | 28 | 43 |

|

| |||||||||

| Government/payer recognizes treatment guidelines | 36 | 37 | 37 | 71 | 70 | 83 | 46 | 38 | 52 |

|

| |||||||||

| Providers have knowledge of guidelines | 29 | 20 | 26 | 50 | 54 | 52 | 33 | 45 | 40 |

|

| |||||||||

| The general public is aware of HCV | 18 | 30 | 17 | 27 | 35 | 17 | 27 | 20 | 24 |

|

| |||||||||

| Patients understand consequences of untreated HCV | 16 | 30 | 29 | 22 | 41 | 44 | 19 | 20 | 26 |

|

| |||||||||

| Patients are aware that HCV is curable | 7 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 32 | 39 | 22 | 23 | 22 |

|

| |||||||||

| Patients have adequate access to HCV providers in their community | 17 | 27 | 31 | 54 | 51 | 62 | 20 | 28 | 35 |

Response of 6 or higher on a 10-point Likert scale, where 0 represents “strongly disagree,” 5 “neither agree nor disagree,” and 10 “strongly agree.”

US, United States; CAN, Canada; LAT, Latin America; WE, Western Europe; CEE, Central/Eastern Europe; NOR, Nordic; AP, Asia/Pacific; MEA, Middle East/Africa; HCV, hepatitis C virus

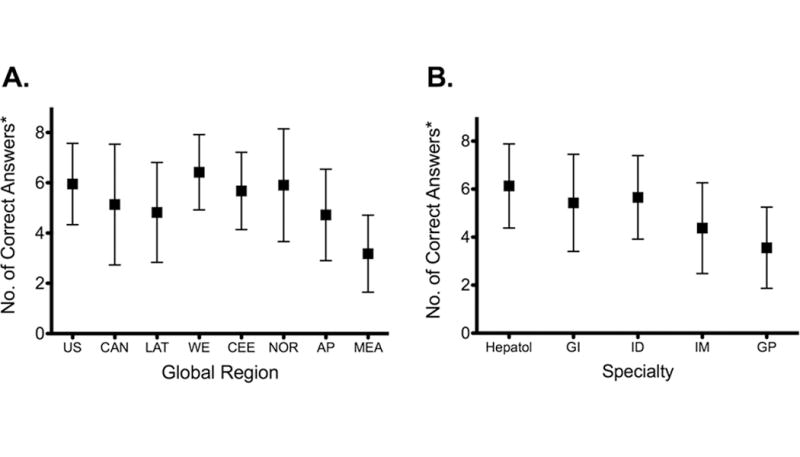

Knowledge

Knowledge of HCV treatment principles varied significantly by region, with physicians in Western Europe correctly answering the most knowledge questions, and those in Middle East and African countries correctly answering the fewest (6.4 vs. 3.2, p<0.001; Figure Ia). Overall, physicians understood that ribavirin is a necessary component of treatment, that treatment duration varies by genotype, and that treatment should be discontinued for patients who fail to achieve an early virologic response (EVR). However, a majority of physicians incorrectly believed that HCV RNA level correlates with liver disease severity and that treatment non-responders should receive maintenance therapy (Table IV). In Middle East/African countries, a majority of respondents also did not appreciate the importance of ribavirin, the role of HCV viral kinetics, and the significance of liver fibrosis stage. Globally, knowledge was highest among hepatologists and lowest among general practitioners (p<0.001 for overall comparison; Figure Ib). Source of treatment information varied by region, with national and government guidelines used most frequently in all regions except the in the United States, where guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) were most commonly used (Supplemental material: Figure II).

Figure 1. Knowledge of HCV Treatment Principles.

Physician knowledge by global region (Panel A) and medical specialty (Panel B).

US, United States; CAN, Canada; LAT, Latin America; WE, Western Europe; CEE, Central/Eastern Europe; NOR, Nordic; AP, Asia/Pacific; MEA, Middle East/Africa; Hepatol, hepatology; GI, gastroenterology; ID, infectious diseases; IM, internal medicine; GP, general practice

*Correct responses indicated by a Likert rating of 6 or higher on the 10-point scale for each of 8 knowledge questions

Table 4.

Physician Knowledge of HCV Treatment Principles

| Statement | % Of Respondents in Agreement with Statement* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | CAN | LAT | WE | CEE | NOR | AP | MEA | Overall | |

| The addition of RBV to PEGIFN improves likelihood of SVR | 91 | 87 | 83 | 93 | 92 | 85 | 77 | 39 | 80 |

|

| |||||||||

| Maintaining an optimal dose of RBV is necessary to achieve SVR | 93 | 90 | 89 | 90 | 82 | 85 | 81 | 46 | 81 |

|

| |||||||||

| Different viral genotypes require different treatment durations | 92 | 77 | 79 | 92 | 96 | 88 | 73 | 57 | 82 |

|

| |||||||||

| Treatment should be stopped if patient does not achieve EVR | 75 | 57 | 37 | 72 | 61 | 77 | 42 | 50 | 58 |

|

| |||||||||

| Treatment should be stopped if patient does not achieve RVR | 44 | 43 | 34 | 31 | 31 | 33 | 37 | 66 | 40 |

|

| |||||||||

| Patients with stage 1 fibrosis have worse outcomes than patients with stage 4 fibrosis | 28 | 33 | 42 | 19 | 29 | 27 | 41 | 72 | 38 |

|

| |||||||||

| The level of HCV RNA has no correlation with liver disease severity | 53 | 30 | 33 | 66 | 51 | 54 | 52 | 36 | 48 |

|

| |||||||||

| Maintenance therapy should be prescribed for treatment non-responders | 37 | 50 | 63 | 21 | 55 | 38 | 74 | 70 | 52 |

Response of 6 or higher on a 10-point Likert scale, where 0 represents “strongly disagree,” 5 “neither agree nor disagree,” and 10 “strongly agree.”

US, United States; CAN, Canada; LAT, Latin America; WE, Western Europe; CEE, Central/Eastern Europe; NOR, Nordic; AP, Asia/Pacific; MEA, Middle East/Africa; RBV, ribavirin; PEGIFN, peginterferon; SVR, sustained virologic response; EVR, early virologic response; RVR, rapid virologic response; RNA, ribonucleic acid

Barriers to Care

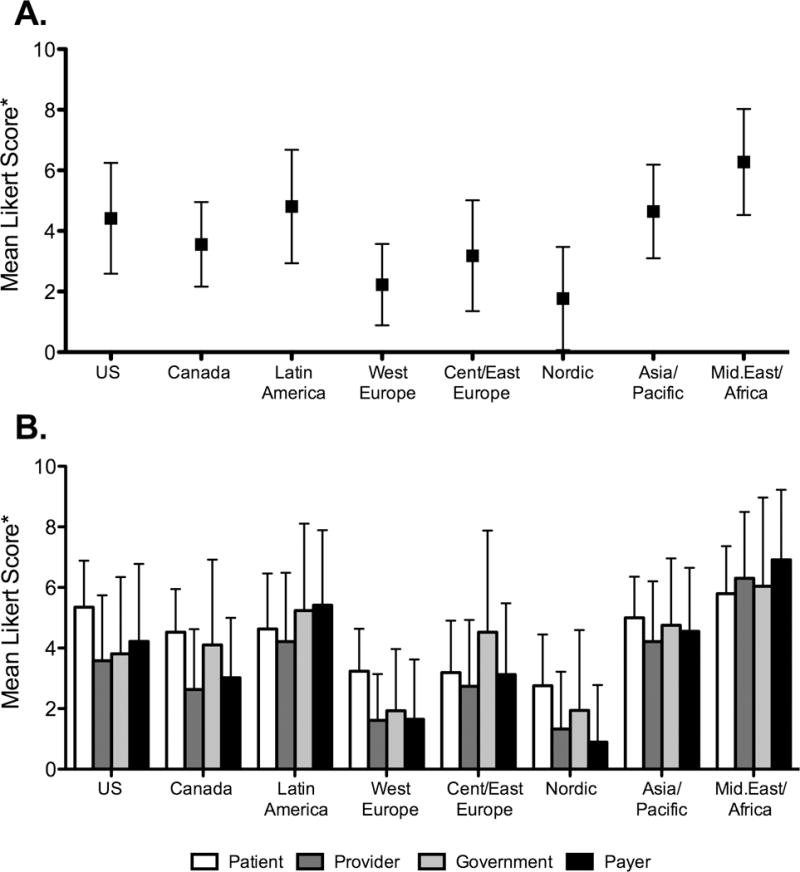

There was significant regional variation in perceived barriers to care, with the greatest barriers reported in Middle East/Africa and the fewest in Nordic countries (Figure IIa; p<0.0001 for overall comparison). Globally, patient-related barriers were viewed as most significant, representing the highest rated barrier category in 5 out of 8 regions, including the United States (Figure IIb). Specific patient-related barriers included fear of side effects and concerns regarding treatment duration, cost, and effectiveness (Supplemental Table I). Payer-related barriers were most prominent in Latin American and Middle East/Africa and included lack of coverage leading to out-of-pocket expense and excessive paperwork requirements. Only one region, Central/Eastern Europe, cited government-related barriers (insufficient funding and lack of treatment promotion) as most significant.

Figure 2. Barriers to HCV Treatment.

A. Barriers by Global region: mean (SD) Likert response to each of 31 potential barriers, by region.

B. Regional Barriers by Category: mean (SD) Likert response to each barrier category, by region.

US, United States; CAN, Canada; LAT, Latin America; WE, Western Europe; CEE, Central/Eastern Europe; NOR, Nordic; AP, Asia/Pacific; MEA, Middle East/Africa

*Each barrier rated on a 10-point Likert scale, from 0 “not a barrier” to 10 “large barrier.”

Along with geographic region, perceived barriers were significantly associated with physician specialty, physician experience, practice setting, and physician knowledge (Table V). Subspecialists (hepatology, gastroenterology, infectious diseases) reported fewer perceived barriers than internists and general practitioners. Likewise, physicians with more experience and higher knowledge scores reported fewer barriers. In multivariable regression analysis, only global region, years of experience, and knowledge were significantly associated with perceived barriers to care (Supplemental material: Table II).

Table 5.

Bivariable Associations Between Physician/Practice Characteristics and Perceived Barriers to Care

| Characteristic | n | Mean Barrier Score§ or Correlation | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Global Region | |||

| United States | 102 | 4.4 | <0.0001 |

| Canada | 30 | 3.6 | |

| Latin America | 100 | 4.8 | |

| Western Europe | 103 | 2.1 | |

| Central/Eastern Europe | 101 | 3.2 | |

| Nordic | 52 | 1.7 | |

| Asia/Pacific | 108 | 4.6 | |

| Middle East/Africa | 101 | 6.3 | |

|

| |||

| Specialty | |||

| Hepatology | 129 | 3.4 | <0.0001 |

| Gastroenterology | 176 | 3.8 | |

| Infectious Diseases | 194 | 3.8 | |

| Internal Medicine | 83 | 4.6 | |

| General Practice | 115 | 5.1 | |

|

| |||

| Years in Practice | 697 | −0.26 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||

| Patients seen monthly | 697 | 0.02 | 0.67 |

|

| |||

| Practice Location | |||

| Urban | 599 | 4.0 | 0.49 |

| Rural/Suburban | 98 | 4.2 | |

|

| |||

| Practice Setting | |||

| Private | 298 | 4.5 | <0.0001 |

| University/Academic | 183 | 3.4 | |

| Government | 182 | 3.9 | |

| Other | 34 | 4.1 | |

|

| |||

| Knowledge Score | 697 | −0.40 | <0.0001 |

Mean response to each of 31 barrier questions, rated on a 10-point Likert scale.

Means and p values based on one-way analysis of variance for categorical variables; Correlations and p values based on Pearson’s correlation

Discussion

This international, multidisciplinary survey study provides insight into the current state of hepatitis C care, as viewed by treating physicians. Key findings of our study include marked regional variation in perceived barriers, the importance of patient-level obstacles, concerning deficits in provider knowledge, and the shared pessimism regarding the current state of HCV care.

Foremost, barriers to care were not perceived equally across global regions. Physicians from Nordic and Western European countries had remarkably low perceptions of treatment barriers (mean Likert responses of 1.7 and 2.1, respectively, on a 10-point scale). In contrast, Middle Eastern and African physicians perceived all barrier categories as problematic (mean Likert response: 6.1 out of 10). Despite regional differences in the magnitude of perceived barriers, there was agreement regarding the nature of these barriers. Across all global regions, patient-level factors were viewed as the greatest obstacles to treatment. This is consistent with prior surveys of physicians and patients in the United States and United Kingdom.(13, 15, 16, 22) Specifically, fear of treatment-related side effects was the most frequently cited barrier in our study. This fear is not unfounded, as nearly all patients will experience at least one treatment-related side effect, and 10% to 14% of patients will discontinue treatment as a result.(2, 4) Though side effects are common, appropriate pretreatment counseling, along with a structured plan for monitoring and management, may help alleviate such fears.(25)

Further patient-level barriers included concerns regarding treatment duration and antiviral effectiveness. Fortunately, the recent introduction of direct-acting antivirals offers the potential for improved response rates and reduced treatment lengths. However, these benefits will need to be balanced against a greater incidence of treatment-related side effects.(4, 5) Nevertheless, each of these patient-level barriers is addressable and, in many cases, modifiable.

To properly address patient fears, physicians must have a thorough understanding of antiviral therapy. Unfortunately, our study identified concerning knowledge deficits, which were most apparent in Middle East/African countries. Physicians in this region often did not acknowledge important treatment principles, including the significance of ribavirin in HCV therapy. Interestingly, across all regions, more than half of physicians indicated that they would treat non-responders with maintenance interferon therapy, despite its lack of efficacy.(26) Similarly, most physicians incorrectly believed that HCV RNA level reflects liver disease severity. Though prior studies of healthcare providers have demonstrated significant knowledge gaps related to HCV,(27) our study documented these deficits in experienced HCV treaters. This is concerning, because inadequate physician knowledge is a known barrier to care.(20) Furthermore, independent of geographic region, medical specialty, or experience level, physicians who scored lower on the knowledge assessment tended to perceive greater barriers to care. The implication here is twofold: physicians with less knowledge may treat fewer patients as a result of incorrectly perceived barriers, and these perceived barriers may be overcome through improved education.

Recognizing the current deficits in physician knowledge, the Institute of Medicine recently recommended the development of HCV educational initiatives, emphasizing a need for increased awareness and improved adherence to guidelines.(28) In our study, only 40% of respondents believed that providers have adequate knowledge of treatment guidelines, highlighting this need. Physicians held similar views regarding public awareness, with less than one-quarter of respondents believing that the public is aware of HCV and its consequences. This view is supported by findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), in which more than half of HCV-infected persons were unaware of their diagnosis.(29) Among injection drug users, this number is as high as 72% to 90%.(30, 31) Unfortunately, awareness does not guarantee treatment. In our study, only 35% of physicians believed that patients have adequate access to HCV providers. A lack of trained specialists, combined with their concentration at academic medical centers, may limit the widespread availability of treatment. Indeed, market surveys in the United States indicate that 80% of HCV patients are managed by 20% of gastroenterologists.(21) Models of expanded HCV treatment, including the use of tele-health, have shown promise.(32) These warrant broader exploration and implementation.

This is the first international study to examine barriers to care among HCV treatment providers. The findings are strengthened by a comprehensive questionnaire, developed and piloted by a panel of internationally recognized HCV experts. The survey achieved a 100% item response rate, eliminating the potential for non-response bias. However, as with any survey, the findings in our study may not be representative of the entire population. Likewise, it was not feasible to survey physicians within every country, leading to the potential for coverage error. By grouping our findings into global regions, we may not have adequately addressed the differences that exist between individual countries. Further, the perceptions identified in this study may not be representative of less-experienced physicians. This may have led to an underestimation of treatment barriers. Finally, HCV treatment is frequently delivered by mid-level providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), particularly in the United States. This study did not address the perspective of these providers, which may differ from those of physicians.

Still, the findings of this study highlight the significant barriers that may impede the prompt and appropriate treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. A focus on patient and provider education, increased awareness, and treatment promotion is necessary if progress is to be made in the global fight against HCV infection.

Conclusions

Recent advances in antiviral therapy have produced dramatic improvements in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Unfortunately, only a minority of HCV-infected persons will receive treatment due to multiple barriers to care. Globally, physicians cite patient-level factors, including fear of side effects and concerns regarding treatment duration and cost, as the greatest barriers to treatment. Inadequate physician knowledge and limited specialist availability may further contribute. Efforts to improve patient and physician education, public awareness, and access to treatment providers are needed.

Supplementary Material

AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; APASL, Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed through the International Conquer C Coalition (I-C3) organization (Appendix). Funding for this program was provided through an educational grant provided by Merck.

The authors would like to thank Lisa Pedicone, Ph.D. for her contributions to this study.

Dr. Fried receives research grants from Merck, Genentech, Vertex, Tibotec/Janssen, Gilead, Bristol Myers Squibb, Abbott. Dr. Fried serves as ad hoc advisor to Merck, Genentech, Vertex, Tibotec/Janssen, Gilead, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Novartis.

Financial Support:

This work was funded by Merck and, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (T32 DK07634, K24 DK066144 (MWF), and UL1RR025747).

Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- SVR

sustained virologic response

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- EVR

early virologic response

- RVR

rapid virologic response

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- GI

Gastroenterology

- ID

Infectious Diseases

- IM

Internal Medicine

- GP

General Practice

- RN

registered nurse

APPENDIX: INTERNATIONAL CONQUER C COALITION

This analysis was led by the International Conquer C Coalition (I-C3), an international, interdisciplinary group of physicians involved in the treatment and care of patients infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Its goal is increasing the understanding of the epidemiology, diagnosis, side effect management, and treatment options. The group also seeks to facilitate an exchange of knowledge, analyze trends, and share best practices. I-C3 was formed in 2009 through an educational grant by Schering-Plough/Merck and was led by Drs. N. Afdhal and S. Zeuzem. Workgroups within I-C3 were responsible for the analysis and publication of key findings on a variety of topics including barriers to care. The work presented here is the result of the barriers to care workgroup.

References

- 1.Hepatitis C. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/. Accessed August 1, 2012.

- 2.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL, Jr, Haussinger D, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poordad F, McCone J, Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195–1206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, Marcellin P, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405–2416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falck-Ytter Y, Kale H, Mullen KD, Sarbah SA, Sorescu L, McCullough AJ. Surprisingly small effect of antiviral treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:288–292. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-4-200202190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowan PJ, Tabasi S, Abdul-Latif M, Kunik ME, El-Serag HB. Psychosocial factors are the most common contraindications for antiviral therapy at initial evaluation in veterans with chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:530–534. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000123203.36471.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lettmeier B, Muhlberger N, Schwarzer R, Sroczynski G, Wright D, Zeuzem S, Siebert U. Market uptake of new antiviral drugs for the treatment of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2008;49:528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grebely J, Raffa JD, Lai C, Krajden M, Kerr T, Fischer B, Tyndall MW. Low uptake of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in a large community-based study of inner city residents. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:352–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butt AA, McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, Justice AC. Hepatitis C treatment completion rates in routine clinical care. Liver Int. 2010;30:240–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volk ML. Antiviral therapy for hepatitis C: why are so few patients being treated? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1327–1329. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGowan CE, Fried MW. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment. Liver international: official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2012;32(Suppl 1):151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraenkel L, McGraw S, Wongcharatrawee S, Garcia-Tsao G. What do patients consider when making decisions about treatment for hepatitis C? Am J Med. 2005;118:1387–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zacks S, Beavers K, Theodore D, Dougherty K, Batey B, Shumaker J, Galanko J, et al. Social stigmatization and hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:220–224. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evon DM, Simpson KM, Esserman D, Verma A, Smith S, Fried MW. Barriers to accessing care in patients with chronic hepatitis C: the impact of depression. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1163–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khokhar OS, Lewis JH. Reasons why patients infected with chronic hepatitis C virus choose to defer treatment: do they alter their decision with time? Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1168–1176. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shehab TM, Sonnad SS, Lok AS. Management of hepatitis C patients by primary care physicians in the USA: results of a national survey. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:377–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaefer M, Schmidt F, Folwaczny C, Lorenz R, Martin G, Schindlbeck N, Heldwein W, et al. Adherence and mental side effects during hepatitis C treatment with interferon alfa and ribavirin in psychiatric risk groups. Hepatology. 2003;37:443–451. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evon DM, Simpson K, Kixmiller S, Galanko J, Dougherty K, Golin C, Fried MW. A randomized controlled trial of an integrated care intervention to increase eligibility for chronic hepatitis C treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zickmund S, Hillis SL, Barnett MJ, Ippolito L, LaBrecque DR. Hepatitis C virus-infected patients report communication problems with physicians. Hepatology. 2004;39:999–1007. doi: 10.1002/hep.20132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiffman ML. A balancing view: We cannot do it alone. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1841–1843. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01433_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkes J, Roderick P, Bennett-Lloyd B, Rosenberg W. Variation in hepatitis C services may lead to inequity of heath-care provision: a survey of the organisation and delivery of services in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viral hepatitis: agenda item 11.12. Sixty-Third World Health Assembly. http://www.who.int/mediacenter/news/releases/2010. Access August 1, 2012.

- 24.UGAM Solutions http://www.ugamsolutions.com. Accessed August 1, 2012.

- 25.Russo MW, Fried MW. Side effects of therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1711–1719. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Bisceglie AM, Shiffman ML, Everson GT, Lindsay KL, Everhart JE, Wright EC, Lee WM, et al. Prolonged therapy of advanced chronic hepatitis C with low-dose peginterferon. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2429–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zickmund SL, Brown KE, Bielefeldt K. A systematic review of provider knowledge of hepatitis C: is it enough for a complex disease? Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2550–2556. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell AE, Colvin HM, Palmer Beasley R. Institute of Medicine recommendations for the prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Hepatology. 2010;51:729–733. doi: 10.1002/hep.23561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volk ML, Tocco R, Saini S, Lok AS. Public health impact of antiviral therapy for hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;50:1750–1755. doi: 10.1002/hep.23220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagan H, Campbell J, Thiede H, Strathdee S, Ouellet L, Kapadia F, Hudson S, et al. Self-reported hepatitis C virus antibody status and risk behavior in young injectors. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:710–719. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhopesh VP, Taylor KR, Burke WM. Survey of hepatitis B and C in addiction treatment unit. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:703–707. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, Deming P, Kalishman S, Dion D, Parish B, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; APASL, Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver.