Abstract

A new method for the rapid and sensitive detection of Legionella pneumophila in hot water systems has been developed. The method is based on an IF assay combined with detection by solid-phase cytometry. This method allowed the enumeration of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 and L. pneumophila serogroups 2 to 6, 8 to 10, and 12 to 15 in tap water samples within 3 to 4 h. The sensitivity of the method was between 10 and 100 bacteria per liter and was principally limited by the filtration capacity of membranes. The specificity of the antibody was evaluated against 15 non-Legionella strains, and no cross-reactivity was observed. When the method was applied to natural waters, direct counts of L. pneumophila were compared with the number of CFU obtained by the standard culture method. Direct counts were always higher than culturable counts, and the ratio between the two methods ranged from 1.4 to 325. Solid-phase cytometry offers a fast and sensitive alternative to the culture method for L. pneumophila screening in hot water systems.

Legionella pneumophila is the main cause for Legionnaires' disease, a common form of severe pneumonia (9). L. pneumophila is ubiquitous in natural freshwater environments and is also present in man-made water systems, where warm waters may facilitate the growth of Legionella cells. Several reports have shown a clear association between the presence of Legionella in hot water systems and the occurrence of legionellosis (8, 14, 16, 26). Human infection can occur by inhalation of contaminated aerosols, produced by showers, air conditioning systems, and other aerosol-generating devices (24). Therefore, the real-time monitoring of water quality, particularly in hospitals, is essential for the early detection of Legionella species and for the prevention of legionellosis outbreaks.

Current methods for detection of Legionella species are based on culture techniques and require at least 3 to 10 days. Additional problems with culture detection include low sensitivity, microbial contamination inhibiting Legionella growth, and the potential presence of viable but nonculturable bacteria (VBNC) (3, 13, 23). Methods based on direct detection, combining immunofluorescent labeling (IF) (19) or fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) (4, 7, 22) with detection by epifluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry (25), allow a more rapid detection of Legionella cells and avoid most of the problems encountered with culture. However, these techniques cannot be applied to the detection of rare events (15). Alternatively, PCR-based assays have been developed for Legionella but remain limited mainly because of (i) the potential presence of PCR inhibitors, (ii) the lack of information on the viability of cells, and (iii) the low sensitivity for the quantification of cells (6, 28). The recent development of solid-phase cytometry (ChemScanRDI; Chemunex, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) has been seen as a great stride forward in the field of quality control, since it represents a rapid and sensitive device for the enumeration of low concentrations of fluorescence-labeled cells in water samples (15). This system can be applied to the detection of pathogenic microorganisms when combined with specific labeling using FISH or IF (2, 20, 21).

The aim of this work was to develop a solid-phase cytometry assay for the specific detection and enumeration of L. pneumophila in hot water systems. An IF staining protocol was optimized and applied to 26 naturally contaminated hot-water samples. L. pneumophila counts obtained with the cytometry protocol were compared to culturable counts obtained by a standard culture method. This new method appears fast and reliable and may be useful for the rapid screening of water samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains used for development of an IF staining protocol.

The Legionella type strains L. pneumophila serogroup (sg) 1 Philadelphia (ATCC 33152) and L. pneumophila sg 3 Bloomington (ATCC 33155) were used for the development of the staining protocol. All Legionella strains were grown on BCYEα (buffered activated charcoal and yeast extract in 2-[(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)amino]ethanesulfonic acid; Oxoid, Dardilly, France) agar for 48 h at 35 ± 1°C with 2.5% carbon dioxide.

Fifteen non-Legionella strains were used for the specificity control (Table 1). These strains were selected because they are frequently found in water systems or have been reported to be cross-reactive with anti-Legionella antibodies.

TABLE 1.

Non-Legionella strains used for the specificity test of the immunofluorescence staining protocol

| Strain | Reactivitya with antibody against the following L. pneumophila sg(s):

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (NRCL) | 1, 6, 7, 12 (Accurate Chemical & Scientific) | 1 (MAbs from Dresden) | 2-6, 8-10, 12-15 (MAbs from Dresden) | |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | − | − | − | − |

| Agrobacterium radiobacter | − | − | − | − |

| Alcaligenes xylosoxidans | − | − | − | − |

| Bacillus cereus | + | − | − | − |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | + | − | − | − |

| Pseudomonas diminuta | + | − | − | − |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | − | − | − | − |

| Pseudomonas putida | − | − | − | − |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | − | − | − | − |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | − | − | − | − |

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis | − | − | − | − |

| Staphylococcus aureus | NT | NT | − | − |

| Xanthomonas maltophilia | − | − | − | − |

| Brevundimonas vesicularis (3 strains) | NT | + | − | − |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | NT | + | − | − |

−, negative reaction; +, positive reaction; NT, not tested.

Artificially contaminated water samples.

Tap water samples negative for L. pneumophila were inoculated with cultured L. pneumophila sg 1 cells (for L. pneumophila sg 1 antibodies) or sg 3 cells (for L. pneumophila non-sg 1 antibodies) (48-h cultures). Cells were added at different concentrations, ranging from 1 to 103 cells per membrane, to evaluate the sensitivity of the assay. In addition, naturally contaminated water samples of different volumes (from 10 to 100 ml) were filtered to assess the potential influence of the volume on cell counts.

Natural water samples.

A total of 26 natural water samples were collected from the hot water systems of four hospitals in Lyon, France, between September 2002 and January 2003. Samples were collected from tap water and from showers in sterile bottles (CML, Nemours, France) according to international standard ISO 11731, modified as described below. The reproducibility of counts obtained by the two methods (solid-phase cytometry and culture) was determined from the analysis of seven different sources located in two hospitals. For each sampling point, 4 liters were collected in separate bottles; 1 liter was analyzed in at least three replicates by the cytometry method, and the remaining 3 liters were analyzed by the culture method. Nineteen other water samples received at the French national reference center for Legionella (NRCL) in the course of routine hospital water system surveillance were analyzed in one single replicate by both cytometry and culture.

Enumeration of legionellae by culture.

Legionella species and serogroups were enumerated and identified according to the ISO-11731 standard, modified as follows. Before concentration, 200 μl of each sample was directly plated onto selective GVPC medium (BCYE supplemented with 3 g of glycine, 100,000 U of polymykin B, 80 mg of cychloheximide, and 1 ng of vancomycin per liter; Oxoid). Then 1-liter samples were filtered through 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate filters (Millipore, Billerica, Mass.), placed in 5 ml of sterile water, and treated with ultrasonic energy for 2 min with a Bioblock Scientific sonicator (Fisher Bioblock Scientific, Illkirch, France) operated at 35 kHz. One hundred microliters of the concentrate was spread by plating onto selective GVPC medium. Samples with high background growth were subjected to standard heat and acid treatments to eliminate non-Legionella organisms. Plates were incubated at 35 ± 2°C with 2.5% carbon dioxide, and colonies were counted after 3, 5, and 10 days. Colonies were examined for fluorescence under a Wood lamp. Colonies exhibiting Legionella morphology were transferred to BCYEα medium (Oxoid) and blood agar (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) as a control. At least five colonies per sample were identified by Legionella-specific latex reagents (Oxoid).

Labeling reagents for ChemScanRDI detection.

Various polyclonal and monoclonal primary antibodies were evaluated for Legionella labeling (Table 2). Two polyclonal antibodies were used: an anti-L. pneumophila sg 1 antibody produced in our laboratory (prepared in rabbits by using L. pneumophila sg 1 ATCC strains Philadelphia, Bellingham, Pontiac, and Knoxville) and labeled with different conjugates and a commercialized anti-L. pneumophila antibody labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, N.Y.). Furthermore, the following monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) were tested: three commercially available MAbs specific for L. pneumophila sg 1 to 14 (from Bio-Rad [Hercules, Calif.], Maine Biotechnology Services [Portland, Maine], and Research Diagnostics Inc. [Flanders, N.J.]) and three MAbs specific for L. pneumophila sg 1; L. pneumophila sg 2 to 6, 8 to 10, and 12 to 15; and all Legionella spp., including L. pneumophila. (10).

TABLE 2.

Evaluation of staining reagents for cytometer detection

| Primary antibody (origin) | Type of detection (origina) | Sample | Result (PIb) | Background level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyclonal antibodies | Green | |||

| Lp sg 1 (NRCL) | Rabbit Ig, secondary antibody,c FITC (Dako) | Lp sg 1 cells | >1,000 | Low |

| Lp sg 1 (NRCL) | Rabbit Ig secondary antibody, HRP, tyramide- FITC (Dako) | Lp sg 1 cells | No staining | |

| Lp sg 1 HRP (NRCL) | Tyramide-FITC (NEN) | Lp sg 1 cells | No staining | |

| Lp sg 1 biotin (NRCL) | Streptavidin-FITC (Dako) | Lp sg 1 cells | 450 | Medium |

| Lp FITC (Accurate Chemical & Scientific) | Lp sg 1 cells | 150 | Low | |

| Lp FITC (Accurate Chemical & Scientific) | Rabbit Ig secondary antibody, FITC (Dako) | Lp sg 1 cells | >1,000 | Low |

| MAbs | ||||

| Monofluo kit Lp sg 1-14 FITC (Bio-Rad) | Lp sg 1 cells | 300 | Low | |

| Monofluo kit Lp sg 1-14 FITC (Bio-Rad) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC (Sigma) | Lp sg 1 cells | 600 | High |

| Lp sg 1-14 Maine Biotechnology Services | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC (Sigma) | Lp sg 1 cells | 250 | Low |

| Lp sg 1-14 (Research Diagnostics) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC (Sigma) | Lp sg 1 cells | No staining | |

| Legionella (Dresden) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC (Sigma) | Lp sg 1 cells | No staining | |

| Lp sg 1 (Dresden) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC (Sigma) | Lp sg 1 cells | 400-500 | Low |

| Lp sg 1 (Dresden) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC (Sigma) | Natural water | 200 | Medium |

| Lp sg 1 (Dresden) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC, + tertiary antibody, FITC (Sigma, Dako) | Lp sg 1 cells | 900-1,000 | High |

| Lp sg 1 (Dresden) | En Vision + mouse IgG secondary antibody, HRP (Dako) | Lp sg 1 cells | No staining | |

| Lp sg 2-6, 8-10, 12-15 (Dresden) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC (Sigma) | Lp sg 3 cells | 300-400 | Low |

| Lp sg 2-6, 8-10, 12-15 (Dresden) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC (Sigma) | Natural water | 250 | Medium |

| Lp sg 2-6, 8-10, 12-15 (Dresden) | Mouse IgG secondary antibody, FITC, + tertiary antibody, FITC (Sigma, Dako) | Lp sg 3 cells | 750 | High |

| Polyclonal antibodies | Red | |||

| Lp sg 1 biotin (NRCL) | Streptavidin-RPE-Cy5 (Dako) | Lp sg 1 cells | 400-500d | Very high |

| Lp sg 1 biotin (NRCL) | Streptavidin-Alexa Fluor-RPE 647 nm (Molecular probes) | Lp sg 1 cells | 700d | Very high |

| Lp sg 1 (NRCL) | Rabbit IgG secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor-RPE 647 nm (Molecular Probes) | Lp sg 1 cells | 600d | Very high |

NEN, Boston, Mass.

PI, mean peak intensity, measured in arbitrary fluorescence units.

Ig, immunoglobulin.

A part of the filtered bacteria was not detected, because their fluorescence was below the limit of detection.

Several detection systems were evaluated as shown in Table 2. The polyclonal rabbit antibodies could be detected by anti-rabbit secondary antibodies, and the MAbs could be detected by anti-mouse secondary antibodies. The biotin-labeled antibodies were detected with streptavidin conjugates, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled antibodies were detected with tyramide-FITC. For detection in the red channel, the polyclonal anti-L. pneumophila sg 1 antibody (NRCL) was revealed by an Alexa Fluor 647-RPE (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) or RPE-Cy5 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) conjugate.

The dilution buffers and concentrations of antibodies were chosen for each type of staining after a preliminary assay (data not shown). Various membrane filters were evaluated for each staining (data not shown). Black polyester membranes (pore size, 0.26 μm; diameter, 25 mm; Chemunex) provided optimal characteristics for FITC labeling. For the red staining, white polycarbonate membranes (pore size, 0.2 μm; diameter, 25 mm; Whatman, Maidstone, United Kingdom) were selected, since the other membranes tested presented excessive fluorescence baselines or nonspecific antibody fixation.

To reduce the background due to nonspecific fixation of the staining reagents, we used (i) various blocking reagents including bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and different normal sera and (ii) the counterstains Evans blue (Réactifs RAL, Martillac, France), CSE/2, CSA, and CSB (Chemunex). Blocking reagents were either applied prior to application of the primary antibody or mixed with the primary antibody, and the counterstain was mixed with the detection reagent.

Labeling technique.

To optimize the labeling protocol, bacteria from a 48-h culture were filtered at a concentration of about 100 bacteria per membrane. For water samples, different volumes ranging from 1 to 20 ml were filtered, depending on the concentration of Legionella cells in the sample. Samples were filtered under a maximum vacuum of 100 mm of mercury through the labeling membranes. For labeling of bacteria, the membrane was incubated for 60 min at 37°C with 100 μl of labeling solution containing the antibody in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (bioMérieux)-0.01% Tween 20 (Sigma)-2% BSA (PBS-T-BSA). The membrane was rinsed by transfer to an absorbent pad soaked with 500 μl of PBS-T-BSA and a 3-min incubation to eliminate excess antibody, followed by transfer to a second absorbent pad to eliminate the remaining washing buffer. The secondary antibody was diluted in PBS-T-BSA with 0.01% Evans blue and applied for 30 min as described for the primary antibody. The EnVision antibody was used according to the supplier's suggestions. Streptavidin conjugates were diluted in PBS-T-BSA and applied in the same manner as the secondary antibody, except that incubation was performed for 30 min at room temperature. Tyramide-FITC was diluted with the dilution buffer supplied with the tyramide and was incubated for 15 min at room-temperature.

Solid-phase cytometer enumeration.

After labeling, the membrane was transferred to the sample holder of the ChemScanRDI solid-phase cytometer (Chemunex). The holder had previously been overlaid with a support pad (black membrane; Chemunex) soaked with 100 μl of PBS-20% glycerol. The entire filter surface is scanned within 3 min. The ChemScanRDI laser scanning device has been described previously (18, 27). Briefly, light is provided by an air-cooled argon laser emitting at 488 nm, and the fluorescence emission is collected in the green channel (500 to 540 nm) for FITC and in the red channel (655 to 705 nm) for Alexa Fluor 647-RPE and RPE-Cy5.

The device is able to differentiate between labeled organisms and fluorescent particles present in the sample based on the optical and electronic characteristics of the signals generated (18). When this discrimination procedure is not used, all fluorescent events detected, including the background signal, are counted by the cytometer and can be manually distinguished by using an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus BX41) fitted on a motorized stage driven by the computer of the cytometer, as described elsewhere (5, 18, 20). Data obtained from manual microscope validation of bacteria were used to optimize the setting of the instrument and the automatic discrimination procedure. These optimized discrimination settings were used for the analysis of natural water samples; in addition, the identities of bacteria were confirmed by manual microscope validation.

Specificity control of the IF protocol.

The specificity of IF labeling was assessed by application of the IF protocol to a set of 15 different species of non-Legionella bacterial strains obtained from clinical and environmental collections (Table 1). Assays were performed using the protocol described above for Legionella strains. The specificity of the L. pneumophila antibody from Accurate Chemical & Scientific was additionally tested on L. pneumophila strains of sg 1 to 15.

Statistical analysis of L. pneumophila counts in natural waters.

The mean numbers of Legionella organisms in seven hot-water samples were determined from at least three replicates and were compared by Student's t test. A Pearson's correlation test was applied to direct counts and culture CFU counts for 26 samples. All analyses were performed with SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

RESULTS

Development of a staining protocol.

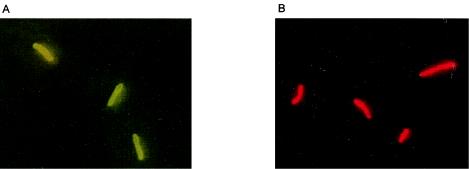

One of the challenges in the development of direct methods for the detection of pathogens by combining fluorescent probes and solid-phase cytometry is to provide bright fluorescent signals and to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio so as to reduce the effect of nonspecific signals. Therefore, various types of staining procedures were applied and compared on cultured L. pneumophila cells (Table 2; Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Micrographs of L. pneumophila sg 1 cultured cells stained by IF. (A) Anti-L. pneumophila sg 1 antibody (MAb from Dresden) detected by an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. (B) Anti-L. pneumophila sg 1 antibody (NRCL) detected by an Alexa Fluor-647-RPE-conjugated secondary antibody.

Solid-phase cytometry allows the detection of at least two different fluorescence emission signals. Therefore, we tested and compared different staining protocols providing green or red fluorescence signals. When a red-emitting dye was used for staining, the baseline due to membrane fluorescence emission was generally too high (about 2,500 fluorescence units) to enable the discrimination of labeled cells. Various other membranes were tested, and although some had a correct baseline, they unfortunately gave rise to excessive background staining (data not shown). The brightest staining intensity (700) was obtained with Alexa Fluor-RPE 647 nm (Table 2; Fig. 1), but the background fluorescence due to nonspecific fixation was too prominent.

In contrast, FITC emission was better adapted to the use of membranes, because it results in less nonspecific fixation. We therefore continued the optimization by evaluating polyclonal antibodies and MAbs detected in the green channel. The simplest labeling procedure, using an FITC-conjugated primary antibody (Accurate Chemical & Scientific) (Table 2), resulted in weak fluorescence intensity. However, the fluorescence signal was significantly increased when amplified with an FITC-labeled secondary antibody. The unconjugated anti-L. pneumophila sg 1 antibody also provided bright staining when detected by an FITC-labeled secondary antibody (Fig. 1). Other amplification systems (biotin-streptavidin or HRP-tyramide-FITC) were evaluated, but the fluorescence was lower than that obtained with the FITC-labeled secondary antibody. Three commercially available MAbs, obtained from Maine Biotechnology Services, Research Diagnostics Inc., and the Bio-Rad Monofluo kit, and three MAbs from the Dresden panel were used with a secondary antibody. The best staining was obtained with two of the MAbs from Dresden (specific for L. pneumophila sg 1 and for sgs 2 to 6, 8 to 10, and 12 to 15); staining intensities were 400 to 500 and 300 to 400, respectively, and background levels were low (Table 2; Fig. 1). We tried to amplify the staining intensity by using either the EnVision antibody combined with tyramide-FITC or an FITC-conjugated “tertiary” antibody specific for the secondary antibody. The EnVision antibody resulted in no signal. Although the tertiary antibody amplified the staining intensity, the signal-to-noise ratio decreased due to an increase in the fluorescent background. Based on these results, the secondary FITC-conjugated antibodies were selected as the best detection method for both polyclonal antibodies and MAbs.

Specificity control.

The NRCL anti-L. pneumophila sg 1 polyclonal antibody does not cross-react with other serogroups (data not shown). The Accurate Chemical & Scientific anti-L. pneumophila polyclonal antibody was found to be specific for sgs 1, 6, 7, and 12, as demonstrated by tests on L. pneumophila type strains (data not shown). The specificity of the MAbs from Dresden has already been reported for the different serogroups (10).

Specificity tests performed on 15 non-Legionella strains isolated from both clinical samples and environmental waters (Table 1) showed that the MAbs from the Dresden panel were not reactive with the strains tested. In contrast, the two polyclonal antibodies cross-reacted with several of the strains tested. Therefore, we selected the MAb protocol for further development of the assay.

Artificially contaminated water samples.

The MAb labeling protocol was applied to inoculated water samples in order to further optimize the protocol and determine the sensitivity of the method. The background fluorescence was more important than that observed with cultures, due to the nonspecific fixation of antibodies to particles naturally present in waters. Various blocking reagents, such as BSA and different normal sera, and the counterstains Evans blue (Réactifs RAL), CSE/2, CSA, and CSB (Chemunex) were evaluated.

A substantial part of the nonspecific fluorescence could be removed when the following combination of blocking reagents and counterstains was applied. BSA and normal swine serum (Dako) were applied 15 min before staining. The primary antibody dilution buffer contained BSA and normal swine serum, and the secondary antibody dilution buffer contained BSA and Evans blue.

Different volumes of water (10 to 100 ml) containing 1 to 100 bacterial cells were analyzed. In all cases, a single cell could be detected independently of the volume analyzed. Two criteria defined the upper limit of the volume that could be filtered and thus the detection limit of the method: (i) the number of particles present in the volume analyzed, not only because they contribute to the background but also because they contribute to membrane warping, and (ii) the number of targeted cells present on the membrane; when this number exceeded 300, the microscope validation was difficult and time-consuming. However, this issue did not affect the efficiency of the method, since it can be solved by filtering a lower volume.

Detection of L. pneumophila in natural water samples.

A total of 26 samples were used to compare cytometry counts with the standard culture method. Seven water samples were collected from the hot water systems of two hospitals in Lyon, France, and analyzed by both cytometry and culture in three replicates, in order to determine the reproducibility of each method. Nineteen other samples were collected from four hospitals as part of the water surveillance scheme at the NRCL. These samples were analyzed in a single analysis by the two detection methods.

Nineteen samples (73.1%) were positive with ChemScanRDI, and 16 (61.5%) were positive in culture (Table 3). Three samples were positive in ChemScanRDI but negative in culture, whereas the opposite trend was never found. The concentration of L. pneumophila organisms enumerated by colony count ranged from 1.2 × 102 to 1.1 × 104 L. pneumophila CFU/liter, and the numbers of L. pneumophila organisms quantified by cytometry ranged from 1.4 × 103 to 4.1 × 106 per liter (Table 3). The concentration reported in the three positive samples found only by cytometry ranged from 1.9 × 103 to 4.1 × 106 L. pneumophila organisms per liter. The ratios of direct counts to CFU counts varied in the range of 1.4 to 38, although two very high ratios were found (148 and 325).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of L. pneumophila counts in natural waters obtained by culture and by the ChemScanRDI

| Sample | Culture result

|

No. of validated bacteria/liter (CV) by ChemScanRDI

|

Ratio of ChemScan counts to culture counts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU/liter (CV)a | Identification | Total L. pneumophila | L. pneumophila sg 1 | L. pneumophila sg 2-6, 8-10, 12-15 | ||

| 1 | 1.2 × 102 (24.7) | L. pneumophila sg 1 | 3.9 × 104 (2.1) | 2.5 × 104 (1.2) | 1.4 × 104 (4.8) | 325 |

| 2 | 1.1 × 104 (11.4) | L. pneumophila sg 2-14 | 1.2 × 105 (6.2) | 1.1 × 104 (3.9) | 1.1 × 104 (30.1) | 10.9 |

| 3 | 5.4 × 103 (7.2)b | L. pneumophila sg 1 | 7.4 × 103 (9.5) | 3 × 103 (2.7) | 4.4 × 103 (1.2) | 1.4 |

| 4 | 1.2 × 102 (24.7) | L. pneumophila sg 2-14 | 2.3 × 103 (9.4) | 0 | 2.3 × 103 (9.4) | 19.2 |

| 5 | 1.3 × 102 (11.2) | L. pneumophila sg 2-14 | 2.8 × 103 (11.2) | 0 | 2.8 × 103 (11.2) | 21.5 |

| 6 | 2.5 × 102 (34.6) | L. pneumophila sg 2-14 | 3.7 × 104 (2.6) | 0 | 3.7 × 10 (3.0) | 148 |

| 7 | 0 | 4.1 × 106 (0.9)c | 1.7 × 103 (9.6) | 4.1 × 106 (0.9) | ||

| 8 | 1.4 × 103 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | 9.7 × 103 | 8.2 × 103 | 1.5 × 103 | 6.9 |

| 9 | 3.4 × 103 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | 7.9 × 103 | 7.6 × 103 | 2.7 × 102 | 2.3 |

| 10 | 0 | 2.2 × 103 | 2.1 × 103 | 1.3 × 102 | ||

| 11 | 0 | 1.9 × 103 | 1.9 × 103 | 0 | ||

| 12 | 5.9 × 103 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | 3.2 × 103 | 2.7 × 103 | 5 × 102 | 0.5 |

| 13 | 1.5 × 103 | L. pneumophila sg 1 (8/10)d | 9 × 103 | 8.8 × 103 | 2 × 102 | 6 |

| L. pneumophila sg 5 (2/10) | ||||||

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 21 | 1.4 × 103 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | 5.1 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 50 | 3.6 |

| 22 | 2.6 × 103 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | 105 | 4.4 × 103 | 105 | 38 |

| 23 | 3.6 × 103 | L. pneumophila sg 1 | 5.1 × 103 | 5 × 103 | 50 | 1.4 |

| 24 | 6 × 102 | L. anisa (1/10) | 1.4 × 103 | 1.3 × 103 | 1.5 × 102 | 2.3 |

| L. pneumophila sg 1 (6/10) | ||||||

| L. pneumophila sg 5 (3/10) | ||||||

| 25 | 4 × 102 | L. anisa (1/5) | 2.9 × 103 | 2.7 × 103 | 1.5 × 102 | 7.3 |

| L. pneumophila sg 1 (4/5) | ||||||

| 26 | 6 × 102 | L. pneumophila sg 1 (1/6) | 1.9 × 103 | 1.8 × 103 | 102 | 3.2 |

| L. pneumophila sg 5 (5/6) | ||||||

CV, coefficient of variation.

Mean of two values: 5.1 × 103 and 5.7 × 103 CFU/L. The deviant value 4 × 104 came from a sample more contaminated than the other two replicates.

Direct counts were confirmed in another culture-negative sample.

Identification of 5 or 10 colonies.

The results from the samples analyzed in triplicate were included in a Pearson's correlation test. When all samples were included, no correlation was observed. However, we eliminated a sample (sample 7) containing a very high level of nonculturable L. pneumophila organisms (106 per liter), and we further omitted one of the three replicates of sample 1 from the analysis, since it was quite different from the other two replicates. With these modified data (37 points, including single samples and replicates), a significant correlation (coefficient of correlation, 0.46; P < 0.05) was found between the counts obtained by the two methods.

DISCUSSION

We developed an assay for the direct enumeration of L. pneumophila in water samples by using an IF staining protocol combined with detection by the ChemScanRDI. Evaluation of various reagents allowed us to select the staining assay that combined optimal sensitivity and specificity.

An important limitation often encountered in the use of antibodies is the lack of specificity. Comparison of a set of commercially available antibodies showed that most polyclonal antibodies cross-reacted with several non-Legionella strains frequently found in water systems (Table 1). In contrast, the MAbs were specific and showed no cross-reactivity with any of the non-Legionella strains tested. This specificity of Legionella antibodies is consistent with reports from other studies (17). Because of the risk of false positives when cross-reactive antibodies are used, we decided to use the MAbs, even though their staining intensity was not as bright as that obtained with the polyclonal antibodies.

Comparison of a large set of membranes and fluorescence detection and amplification protocols has revealed the importance of such a comparison in optimizing the signal/noise ratio. The best result was obtained with a very simple amplification technique combining two FITC-conjugated antibodies. When this technique was applied to the detection of Legionella cells in natural waters, the fluorescence was lower than that obtained for cells in culture (Table 2). This might be explained partly by the size of the bacteria, since environmental, planktonic legionellae are generally smaller than cultured bacteria. James et al. have demonstrated that cell length and cell complexity were reduced by 30 and 80%, respectively, when L. pneumophila was subjected to starvation (12). Furthermore, this decrease in staining intensity can also be explained by a difference in antigen expression between natural and cultured bacteria.

When the cytometry assay was applied to natural water samples and compared to the standard culture method, we demonstrated that the counts were well correlated, although direct counts were always higher than culturable counts. Investigators using other culture-independent methods have reported similar results, probably because these methods detect nonculturable Legionella in addition to culturable bacteria. Palmer et al. (19) reported that culturable counts of Legionella spp. were lower than the counts obtained by the direct fluorescent antibody detection and PCR methods. Investigators using a real-time LightCycler PCR assay developed for quantitative determination of legionellae in tap water samples reported that the amounts of legionellae calculated from the PCR results were associated with the CFU detected by culture, but PCR results were mostly higher than culture results (28). Both real-time PCR and IF detection, such as our cytometry assay, are faster and more sensitive than culture detection.

We investigated the reproducibility of cytometry counts by analyzing at least three subsamples from a single 1-liter sample and that of the culture method by analyzing three 1-liter samples. In most cases, the variation between samples was small enough (as revealed by the coefficient of variation), except for one sample (sample 6) analyzed by culture, since a high variation between replicates was found for this sample. Although we have no clear explanation for this, the variation is more likely due to the presence of dispersed or aggregated bacteria.

Since all culture-positive samples were also cytometry positive, we considered the risk for false negatives with cytometry assays to be low. The risk for false-positive results with the cytometry method could not be evaluated on natural samples, since the two counting methods did not target the same populations. In the case of the IF detection, total cells are detected, including living and dead cells, whereas the culture approach detects only living cells that are able to reproduce on a selective medium. This explains why the ratio between counts is sometimes very high and suggests the presence of an important fraction of unculturable cells in waters. For example, in one sample (sample 7), we detected important concentrations (106 organisms per liter) of non-sg 1 L. pneumophila, but none were recovered by culture. The characteristics of the sampling point, the bottom of a hot water tank, might explain this discordance, because the temperature at the sampling point was 55°C, suggesting that the bacteria might have been killed by heat. Furthermore, in natural environments Legionella cells can display different physiological states, including culturable, VBNC, or dead cells, and this also contributes to the discrepancies reported between counts (11, 19, 23, 29). Steinert et al. suggested that the VBNC form is a potential source of infection by demonstrating that VBNC Legionella cells could be resuscitated by coincubation with amoebae without any loss of virulence (23). Therefore, information regarding the viability of cells should be of great interest. Such information could be obtained by combining the taxonomic probe with a viability dye if the two fluorescent probes could be distinguished on the basis of their respective emission wavelengths. In this study we evaluated red-specific staining with the future aim of simultaneously labeling the cells with a taxonomic probe and a viability stain, since most viability dyes are detected in the green channel. We encountered technical limitations because the commercially available membranes cannot be used for the detection in the red channel due to an important autofluorescence and/or due to high levels of nonspecific interaction with the antibody. Further developments in the quality of the membranes should reduce these problems.

Further studies should also be performed to develop a method that can detect Legionella inside free-living protozoa or in biofilms. These forms might be more numerous than the planktonic forms, because this is their ecological niche of proliferation (1).

Our results suggest that the solid-phase cytometry approach provides a method capable of performing rapid screening of L. pneumophila contamination in waters, although additional validation on a greater number of samples should be performed to confirm these results. This method, although it detects living and nonliving cells, should be useful for the rapid and efficient surveillance of hot water systems, particularly for hospitals which actually use time-consuming methods based on culture for monitoring water quality. Other purposes such as evaluation of disinfection measures or large-scale studies would also be facilitated by this method.

When outbreaks occur, it is important to be able to identify potential sources of contamination promptly. However, the isolation of the bacterium remains essential in order to perform the molecular typing necessary for strain identification and to identify the contamination source. Other limits of the cytometry method include (i) the initial cost for the cytometer (which should be reduced with the increasing number of applications and instruments on the market and by the emergence of low-cost lasers) and (ii) the actual need for manual validation, which excludes total automation of the method. Nevertheless, results for 15 to 20 samples may be obtained within a working day.

In conclusion, we have developed an assay for the rapid and sensitive enumeration of L. pneumophila in water samples. This assay allowed us to quantify the L. pneumophila contamination in a water sample within 4 h and should therefore be useful for the rapid screening of water systems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Electricité de France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu Kwaik, Y., L. Y. Gao, B. J. Stone, C. Venkataraman, and O. S. Harb. 1998. Invasion of protozoa by Legionella pneumophila and its role in bacterial ecology and pathogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3127-3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baudart, J., J. Coallier, P. Laurent, and M. Prevost. 2002. Rapid and sensitive enumeration of viable diluted cells of members of the family Enterobacteriaceae in freshwater and drinking water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5057-5063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bej, A. K., M. H. Mahbubani, and R. M. Atlas. 1991. Detection of viable Legionella pneumophila in water by polymerase chain reaction and gene probe methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:597-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchbinder, S., K. Trebesius, and J. Heesemann. 2002. Evaluation of detection of Legionella spp. in water samples by fluorescence in situ hybridization, PCR amplification and bacterial culture. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catala, P., N. Parthuisot, L. Bernard, J. Baudart, K. Lemarchand, and P. Lebaron. 1999. Effectiveness of CSE to counterstain particles and dead bacterial cells with permeabilised membranes: application to viability assessment in waters. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 178:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catalan, V., F. Garcia, C. Moreno, M. J. Vila, and D. Apraiz. 1997. Detection of Legionella pneumophila in wastewater by nested polymerase chain reaction. Res. Microbiol. 148:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Declerck, P., L. Verelst, L. Duvivier, A. Van Damme, and F. Ollevier. 2003. A detection method for Legionella spp. in (cooling) water: fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH) on whole bacteria. Water Sci. Technol. 47:143-146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallon, R. J. 1980. Nosocomial infections with Legionella pneumophila. J. Hosp. Infect. 1:299-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fields, B. S., R. F. Benson, and R. E. Besser. 2002. Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:506-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helbig, J. H., J. B. Kurtz, M. C. Pastoris, C. Pelaz, and P. C. Luck. 1997. Antigenic lipopolysaccharide components of Legionella pneumophila recognized by monoclonal antibodies: possibilities and limitations for division of the species into serogroups. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2841-2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussong, D., R. R. Colwell, M. O'Brien, E. Weiss, A. D. Pearson, R. M. Weiner, and W. D. Burge. 1987. Viable Legionella pneumophila not detectable by culture on agar media. Bio/Technology 5:947-950. [Google Scholar]

- 12.James, B. W., W. S. Mauchline, P. J. Dennis, C. W. Keevil, and R. Wait. 1999. Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate in Legionella pneumophila, an energy source for survival in low-nutrient environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:822-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joux, F., and P. Lebaron. 2000. Use of fluorescent probes to assess physiological functions of bacteria at single-cell level. Microbes Infect. 2:1523-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kool, J. L., D. Bergmire-Sweat, J. C. Butler, E. W. Brown, D. J. Peabody, D. S. Massi, J. C. Carpenter, J. M. Pruckler, R. F. Benson, and B. S. Fields. 1999. Hospital characteristics associated with colonization of water systems by Legionella and risk of nosocomial Legionnaires' disease: a cohort study of 15 hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 20:798-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemarchand, K., N. Parthuisot, N. Catala, and P. Lebaron. 2001. Comparative assessment of epifluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry and solid-phase cytometry used in the enumeration of specific bacteria in water. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 25:301-309. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lück, P. C., H.-M. Wenchel, and J. H. Helbig. 1998. Nosocomial pneumonia caused by three genetically different strains of Legionella pneumophila and detection of these strains in the hospital water supply. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1160-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makin, T., and C. A. Hart. 1989. Detection of Legionella pneumophila in environmental water samples using a fluorescein conjugated monoclonal antibody. Epidemiol. Infect. 103:105-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mignon-Godefroy, K., J. G. Guillet, and C. Butor. 1997. Solid phase cytometry for detection of rare events. Cytometry 27:336-344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer, C. J., Y.-L. Tsai, C. Paszco-Kolva, C. Mayer, and L. R. Sangermano. 1993. Detection of Legionella species in sewage and ocean water by polymerase chain reaction, direct fluorescent-antibody, and plate culture methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3618-3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pougnard, C., P. Catala, J. L. Drocourt, S. Legastelois, P. Pernin, E. Pringuez, and P. Lebaron. 2002. Rapid detection and enumeration of Naegleria fowleri in surface waters by solid-phase cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3102-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pyle, B. H., S. C. Broadaway, and G. A. McFeters. 1999. Sensitive detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in food and water by immunomagnetic separation and solid-phase laser cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1966-1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Satoh, W., M. Nakata, H. Yamamoto, T. Ezaki, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Enumeration of Legionella CFU by colony hybridization using specific DNA probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6466-6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinert, M., L. Emödy, R. Amann, and J. Hacker. 1997. Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2047-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinert, M., U. Hentschel, and J. Hacker. 2002. Legionella pneumophila: an aquatic microbe goes astray. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26:149-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyndall, R. L., R. E. Hand, R. C. Mann, C. Evans, and R. Jernigan. 1985. Application of flow cytometry to detection and characterization of Legionella spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:852-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent-Houdek, M., H. L. Muytjens, G. P. Bongaerts, and R. J. van Ketel. 1993. Legionella monitoring: a continuing story of nosocomial infection prevention. J. Hosp. Infect. 25:117-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallner, G., D. Tillmann, K. Haberer, P. Cornet, and J.-L. Drocourt. 1997. The ChemScan system: a new method for rapid microbiological testing of water. Eur. J. Parent. Sci. 2:123-126. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wellinghausen, N., C. Frost, and R. Marre. 2001. Detection of legionellae in hospital water samples by quantitative real-time LightCycler PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3985-3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto, H., Y. Hashimoto, and T. Ezaki. 1996. Study of nonculturable Legionella pneumophila cells during multiple-nutrient starvation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 20:149-154. [Google Scholar]