Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine health-related quality of life (HRQL) among women with metastatic breast cancer treated on E2100 with paclitaxel or paclitaxel plus bevacizumab. Trial participants (N = 670) completed the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) pre-treatment and following 4 and 8 cycles of treatment to assess HRQL and breast cancer-specific concerns. A significantly higher proportion of missing FACT-B assessments was observed among patients receiving paclitaxel only, due to faster time to death. To account for this non-ignorable pattern of missing data, we conducted a survival-adjusted HRQL analysis by jointly modeling the longitudinal HRQL outcome and time to non-ignorable dropout using a two-stage model. FACT scores assessing HRQL did not differ following 4 and 8 cycles of treatment; however mean scores on the 9-item Breast Cancer Scale were significantly higher after 4 and 8 cycles of treatment among patients receiving paclitaxel plus bevacizumab. No differences were observed between treatment arms on FACT-B total scores. The addition of bevacizumab was not associated with additional side effect burden from the patient perspective and was associated with a greater reduction in breast cancer-specific concerns. No other differences were noted.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, Metastatic breast cancer, Survival-adjusted quality of life, Patient-reported outcomes

Introduction

An estimated 1,78,480 new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in 2007, and more than 40,000 women in the US die from breast cancer each year [1]. This number is second only to lung cancer in accounting for cancer deaths among women [1]. Metastatic breast cancer is treated with systemic therapies that can increase survival time or time free from progression of disease. Delaying disease progression, even in the absence of an overall survival benefit, may provide for a quality of life that is better than what would be experienced when living with disease progression. On the other hand, treatments often carry toxicity, so survival (whether extended or not) is often compromised by treatment side effects. When evaluating efficacy of new treatments for metastatic breast cancer, competing trade offs of survival time, disease symptom relief, and treatment toxicity must therefore be considered, either implicitly or explicitly.

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) phase III trial E2100 compared paclitaxel plus bevacizumab to paclitaxel alone for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Patients who received paclitaxel plus bevacizumab experienced significantly prolonged progression-free survival in comparison to those receiving paclitaxel alone (median 11.8 vs. 5.9 months; hazard ratio for progression 0.60, P < 0.001; 2). Overall survival did not differ between treatment arms. Because the primary end point for E2100 was progression-free survival and in light of the lack of significant differences in overall survival, the quality of the additional time gained was an important secondary endpoint. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) was administered to E2100 participants before and during treatment to assess physical, functional, emotional, and social well-being and breast cancer-specific concerns.

Based on an initial examination of health-related quality of life (HRQL) data, no significant differences in mean FACT-B change scores from baseline were observed between treatment arms [2, 3]. These findings were based on analyzing change in FACT-B scores using Wilcoxon rank-sum test and a pattern-mixture model analysis for longitudinal data with non-ignorable missing data [4]. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test for change in FACT-B scores is a nonparametric univariate analysis that compared the mean score changes for weeks 17 and 33 separately using only available HRQL assessments. The pattern-mixture model analysis was not able to incorporate the available information about reasons for dropout. Upon close examination of FACT-B data, we observed a higher rate of drop-out due to illness or death in the paclitaxel only arm (missing data due to death at week 33: 5.8% paclitaxel plus bevacizumab vs. 10.2% paclitaxel only; Fisher's exact test P = 0.045). This difference in early survival is not taken into account in the previously reported analyses which, while not statistically significant, indicated a modest relative benefit in the bevacizumab-containing arm [2]. In addition, some living patients who did not complete follow-up questionnaires failed to do so because they were too ill, and this is documented in their record. The question therefore remains whether adjusting the available FACT-B data for observed group differences in early survival or health deterioration might produce a different conclusion regarding the addition of bevacizumab to paclitaxel. The challenge of handling non-ignorable missing longitudinal data from clinical trial participants plagues the interpretability of patient-reported endpoints, particularly on metastatic treatment trials—a setting in which quality of life and patient well-being is most salient. Regardless of the impact on study conclusions, the method reported here provides an example for how to integrate survival and quality of life endpoints into a single analysis when the emphasis is on quality of life during a finite period (in this case the first 4–8 months after beginning therapy). This can be thought of as “survival-adjusted quality” in contrast to the more common “quality-adjusted survival.” The purpose of this study was therefore to examine quality of life data from E2100 data using a survival-adjusted quality of life approach, which is a more appropriate statistical model given the disproportionate rate of attrition due to death. By using a more appropriate statistical model, we can rule-out the possibility that the lack of differences observed between treatment arms was due to non-ignorable missing data. We hypothesized that patients on the paclitaxel only arm would report lower HRQL, specifically physical well-being, functional well-being, and breast cancer-specific concerns due to poorer control of disease in comparison to patients receiving paclitaxel plus bevacizumab. We anticipated this despite any symptom burden introduced by bevacizumab, given this novel agent is relatively well tolerated.

Patients and methods

Local institutional review board approval was obtained for participating sites and written informed consent was required from each patient before being screened for trial eligibility. Patients with histologically or cytologically confirmed metastatic breast cancer who had not received previous cytotoxic therapy for metastatic disease were eligible to enroll on E2100. Previous hormonal therapy or cytotoxic adjuvant chemotherapy was allowed. If patients received taxane-based adjuvant therapy, they were required to have had a disease-free interval of a minimum of 12 months after completion of taxane therapy.

From December 2001 to May 2004, 722 patients were randomly assigned to receive paclitaxel 90 mg/m2 of body-surface area on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks, either alone (n = 354) or in combination with bevacizumab 10 mg/kg of body weight on days 1 and 15 (n = 368). Participants were stratified by disease-free interval (≤24 vs. >24 months), the number of metastatic sites (<3 vs. ≥3 sites), prior adjuvant chemotherapy, and estrogen receptor positivity (ER+ vs. ER– vs. ER unknown). Patient demographic and disease characteristics for patients who completed partial or complete HRQL data are presented in Table 1. Additional details on the full sample of clinical trial participants can be found elsewhere [2].

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics (eligible patients with complete or partial HRQL data)

| Paclitaxel + bevacizumab (n = 341) | Paclitaxel (n = 315) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 56 (29–84) | 55 (27–85) |

| Estrogen receptor | ||

| Positive | 205 (60.1%) | 197 (62.5%) |

| Negative | 130 (38.1%) | 115 (36.5%) |

| Unknown | 6 (1.8%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| Progesterone receptor | ||

| Positive | 153 (44.9%) | 140 (44.4%) |

| Negative | 171 (50.1%) | 163 (51.7%) |

| Unknown | 17 (5.0%) | 12 (3.8%) |

| HER2 | ||

| Positive | 5 (1.5%) | 3 (1.0%) |

| Negative | 315 (92.4%) | 284 (90.2%) |

| Unknown | 21 (6.2%) | 28 (8.9%) |

| Prior adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| None | 123 (36.1%) | 109 (34.6%) |

| Anthracycline | 130 (38.1%) | 129 (41.0%) |

| Taxane | 59 (17.3%) | 47 (14.9%) |

| Disease-free interval | ||

| ≤24 months | 140 (41.1%) | 129 (41.0%) |

| >24 months | 201 (58.9%) | 186 (59.0%) |

| Extent of disease | ||

| ≥3 sites | 148 (43.4%) | 146 (46.3%) |

| <3 sites | 193 (56.6%) | 169 (53.7%) |

| Sites of disease | ||

| Visceral involvement* | 272 (79.8%) | 276 (87.6%) |

| Bone only | 35 (10.3%) | 23 (7.3%) |

| Disease evaluation | ||

| Measurable† | 235 (68.9%) | 247 (78.4%) |

| Nonmeasurable | 106 (31.1%), | 68 (21.6%) |

P = 0.008 (Fisher's exact test, two-sided)

P = 0.006 (Fisher's exact test, two-sided)

HRQL assessment

HRQL endpoints were assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B; 5). The FACT-B includes the 27-item FACT-General (FACT-G) and the 9-item Breast Cancer Subscale (BCS). The FACT-G assesses overall physical, functional, emotional, and social well-being. The BCS provides a more targeted assessment of concerns specific to breast cancer patients. The Trial Outcome Index (TOI) is a composite score calculated by summing the physical and functional well-being scales from the FACT-G and the BCS, yielding a sum score based on 23 items. These three FACT-B endpoints (FACT-G Total; BCS; TOI) were set a priori as the endpoints for the analysis. In addition, two items were selected from the FACT-G (“I have pain” and “I am bothered by side effects of treatment”) for individual item analysis. We selected the item “I have pain” a priori based on the report of higher rates of peripheral neuropathy among participants receiving bevacizumab plus paclitaxel in comparison to the paclitaxel only arm (grade 3/4 23.6% paclitaxel plus bevacizumab vs. 17.6% paclitaxel alone, P = 0.03; 2). We examined responses to the item “I am bothered by side effects of treatment” to capture any additional symptom burden introduced by bevazicumab. We selected a general item to measure additional toxicities introduced by this novel agent given our relative lack of understanding from the patient perspective of symptoms associated with treatment. For all endpoints, including the selected individual items, a higher score indicates better quality of life.

The FACT-B was administered to trial participants at trial enrollment and before randomization and at weeks 17 and 33. HRQL assessments were obtained at weeks 17 and 33 to correspond to the completion of cycles 4 and 8 of treatment.

Statistical analysis: joint modeling method

Table 2 provides detail on reasons for missing data at each assessment. There were 345 patients eligible for HRQL study in the combined chemotherapy arm; 325 in the paclitaxel only arm. Before conducting joint modeling, a nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test was conducted to compare HRQL outcomes between the arms at each of the three time points separately, using only available HRQL assessments. A total of 14 FACT-B assessments (2.2%) were missing for all three time points from eligible patients. By week 33, a higher percentage of patients had expired in the paclitaxel alone arm (10.2%) compared to the paclitaxel plus bevacizumab arm (5.8%). Using this information, patients were classified into two mutually exclusive groups: (1) those who completed the questionnaires at all three scheduled times, or who dropped out for reasons which we assume to be random (i.e., not due to health deterioration) and (2) those who dropped out due to death or ill health. Group 1 included those patients whose probabilities of dropping out were dependent on covariates (e.g., treatment arm) but not the outcome. HRQL measures of patients in group 2 were assumed to be missing in a non-ignorable fashion. To handle this non-ignorable missing data problem, we jointly modeled the longitudinal HRQL outcome and time to non-ignorable dropout, defined as time to death or time to dropout due to illness, whichever occurred first, using a two-stage model [5]. The first stage assumes that each patient's HRQL outcome follows a linear model with random intercept and slope, where the only covariate is time when the HRQL questionnaires were completed. In the second stage of the model, we assume that the random intercept and slope and a log-transformed time to non-ignorable dropout follow a multivariate normal distribution. The joint distribution of the HRQL outcome and the time to non-ignorable dropout are estimated via maximum likelihood using the expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm, and using the bootstrap to calculate standard errors.

Table 2.

Reasons for missing FACT-B assessments per treatment arm by assessment time point (eligible patients)

| Reason | Baseline |

17 Weeks |

33 Weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB (%) | P (%) | PB (%) | P (%) | PB (%) | P (%) | |

| Random (ignorable) | ||||||

| Pt refusal | 2 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) | 6 (1.9) | 3 (0.9) | 9 (2.8) | |

| Pt did not show for appt. | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.2) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.2) | ||

| Staff error or unavailable | 5 (1.5) | 9 (2.8) | 27 (7.8) | 38 (11.8) | 33 (9.6) | 34 (10.5) |

| Not required | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.7) | 3 (0.9) | ||

| Other | 5 (1.5) | 7 (2.1) | 6 (1.8) | 22 (6.8) | 29 (8.4) | 29 (9.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 8 (2.3) | 16 (5.0) | 27 (7.8) | 28 (8.7) |

| Non-random (not ignorable) | ||||||

| Pt deemed too ill | 6 (1.8) | 2 (0.6) | 7 (2.0) | 6 (1.8) | ||

| Pt expired | 10 (2.9) | 10 (3.1) | 20 (5.8) | 33 (10.2) | ||

| Total | 13 (3.9) | 20 (6.1) | 65 (19.0) | 99 (30.7) | 128 (37.1) | 146 (45.1) |

P paclitaxel, B bevacizumab, Pt patient, appt appointment

To circumvent a convergence problem in the EM algorithm when using the observed HRQL scores, we used a transformation (Maximum possible score-HRQL score)1/2 to produce HRQL outcomes for FACT-G/TOI/BCS HRQL scores in the joint modeling analysis. The HRQL outcomes are approximately normally distributed after this transformation. Maximum possible score is 108 for FACT-G, 36 for BCS, and 92 for TOI. Before conducting joint modeling, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was conducted to compare HRQL outcomes between the arms at each of the three time points separately, using only available HRQL assessments.

Results

Before comparing groups, internal consistency of each selected endpoint was evaluated. Across all three assessments, the FACT-B, BCS, and TOI demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.81 to 0.88.

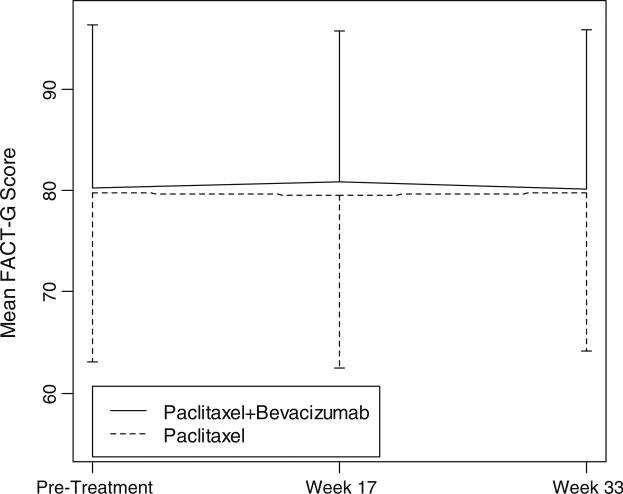

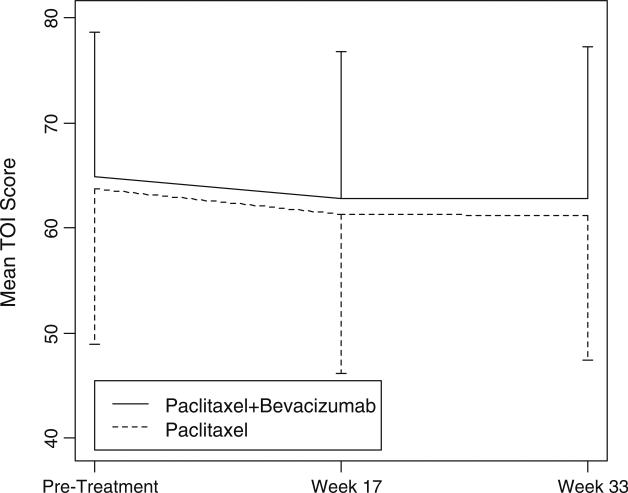

Mean scores per treatment arm for the FACT-G, the TOI, and the FACT-BCS for all three assessment time points are presented in Table 3. Treatment groups did not differ at baseline on any of these three identified endpoints. FACT-G and TOI scores between treatment arms also were not significantly different at weeks 17 and 33, even after applying the survival- and deterioration-adjusted analysis. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the trajectory of FACT-G Total scores and the TOI scores at baseline and at weeks 17 and 33. However, when compared to patients receiving paclitaxel alone, those receiving paclitaxel plus bevacizumab reported higher (better) mean scores on the BCS at week 17 (x = 23.8 vs. 22.7, P < 0.05) and at week 33 (x = 24.1 vs. 22.4, P < 0.01). The BCS items include content covering dyspnea, lymphedema, alopecia, weight change, pain, change in appearance, feeling self-conscious about attractiveness, fear of family members getting cancer, and fear about the effects of stress on illness (see www.facit.org for full item content). The trajectory of BCS scores throughout the treatment is demonstrated in Fig. 3. Based on the joint modeling analysis, which assumed a linear effect of time, there was a marginally insignificant difference in BCS score change over time, measured by slopes, between the two treatment arms (P = 0.053). A quadratic time effect term was not significant when added in the model. Patients who received paclitaxel plus bevacizumab demonstrated a greater reduction in breast cancer-specific concerns than those receiving paclitaxel alone.

Table 3.

Comparison of quality of life measures (eligible patients)

| Variable | RX Arm | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | Wilcoxon test P value (two-sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACT-B (BCS)-baseline | PB | 330 | 23.99 | 5.69 | 0.36 |

| P | 302 | 23.50 | 5.85 | ||

| FACT-B (BCS)-17 weeks | PB | 275 | 23.75 | 5.86 | 0.038 (0.14)* |

| P | 219 | 22.66 | 6.20 | ||

| FACT-B (BCS)-33 weeks | PB | 213 | 24.08 | 5.63 | 0.007(0.09)* |

| P | 170 | 22.41 | 6.15 | ||

| FACT-G-baseline | PB | 332 | 80.26 | 16.00 | 0.78 |

| P | 305 | 79.75 | 16.61 | ||

| FACT-G-17 weeks | PB | 278 | 80.88 | 14.86 | 0.56 |

| P | 221 | 79.47 | 16.97 | ||

| FACT-G-33 weeks | PB | 215 | 80.10 | 15.69 | 0.70 |

| P | 173 | 79.71 | 15.55 | ||

| TOI-baseline | PB | 329 | 64.87 | 13.75 | 0.47 |

| P | 302 | 63.74 | 14.79 | ||

| TOI-17 weeks | PB | 277 | 62.79 | 14.05 | 0.35 |

| P | 221 | 61.32 | 15.11 | ||

| TOI-33 weeks | PB | 215 | 62.80 | 14.49 | 0.19 |

| P | 172 | 61.19 | 13.72 | ||

| Individual item | |||||

| I have pain-baseline | PB | 333 | 2.46 | 1.23 | 0.26 |

| P | 304 | 2.56 | 1.22 | ||

| I have pain-17 weeks | PB | 278 | 2.88 | 1.12 | 0.35 |

| P | 220 | 2.79 | 1.16 | ||

| I have pain-33 weeks | PB | 215 | 2.69 | 1.15 | 0.84 |

| P | 175 | 2.71 | 1.16 | ||

| I am bothered by side effects-baseline | PB | 287 | 3.40 | 1.00 | 0.30 |

| P | 266 | 3.48 | 0.97 | ||

| I am bothered by side effects-17 weeks | PB | 275 | 2.53 | 1.03 | 0.21 |

| P | 223 | 2.63 | 1.10 | ||

| I am bothered by side effects-33 weeks | PB | 216 | 2.46 | 1.13 | 0.80 |

| P | 174 | 2.42 | 1.16 |

The P values in the parentheses are based on the tests comparing the changes in the FACT-B (breast elements) scores from baseline to 17 (or 33) weeks

Fig. 1.

Mean FACT-G scores per treatment arm across assessment time points. FACT-G functional assessment of cancer therapy—general questionnaire. See www.facit.org for full item content. The vertical bars represent standard deviations

Fig. 2.

Mean TOI scores per treatment arm across assessment time points. TOI trial outcome index from the functional assessment of cancer therapy—breast questionnaire. See www.facit.org for full item content. The vertical bars represent standard deviations

Fig. 3.

Mean FACT-BCS scores per treatment arm across assessment time points. BCS: functional assessment of cancer therapy breast cancer subscale items include content covering dyspnea, lymphedema, alopecia, weight change, pain, change in appearance, feeling self-conscious about attractiveness, and fear of family members getting cancer and fear about the effects of stress on illness. See www.facit.org for full item content. The vertical bars represent standard deviations

No differences in mean scores between treatment arms were observed on individual items “I have pain” and “I am bothered by side effects of treatment.” Mean scores on these two items are provided in Table 2.

Discussion

Given the superiority in progression-free survival among participants receiving paclitaxel plus bevacizumab in comparison to those receiving paclitaxel alone, we employed a statistical model to analyze HRQL data that takes this disproportionate dropout into account. The reported pattern-mixture model analysis which did not take into account the observed group difference in dropout rate due to early death was not statistically significant [2]. We therefore analyzed FACT-B data from E2100 trial participants using a survival-adjusted quality of life model. Based on this approach, participants who received paclitaxel plus bevacizumab reported fewer breast cancer-specific concerns following 4 and 8 cycles of treatment in comparison to patients who received paclitaxel alone. The scale used to assess breast cancer-specific concerns, the BCS, consists of nine statements that primarily assess symptoms and concerns unique to breast cancer patients. Group differences over time were not significantly different for the other two planned HRQL endpoints, the FACT-G (general quality of life) and the more physically focused FACT-B TOI [6]. The original report of HRQL results from E2100 concluded that there were no group differences in all three of these primary HRQL endpoints [2]. This revised analysis, more formally adjusting longitudinal group differences with information regarding early death and dropout due to health deterioration, agreed with the original conclusions in two of the three endpoints, but suggested a modest but potentially meaningful benefit to paclitaxel plus bevacizumab relative to paclitaxel alone in breast cancer-specific concerns as measured by the BCS.

Although, the prevailing conclusion from this study appears to be the absence of a difference over time, the trends in the data suggest that the addition of bevacizumab to paclitaxel did not introduce additional toxicities which interfered with HRQL beyond the benefits provided by combined therapy. The addition of bevacizumab was associated with a greater reduction in breast cancer-specific concerns, perhaps due to lessened disease-related symptoms, less worry about the future due to prolonged progression-free survival and the overall perception of better disease control. Of note, providers and participants were not blinded to treatment arm assignment; therefore a limitation of this study is that knowledge of being assigned to the treatment arm may have contributed to higher HRQL. An additional limitation of this trial is that the majority of participants previously received chemotherapy for metastatic disease, which may have had long-term effects on HRQL thus confounding our results.

The HRQL data obtained in this trial offers insight into the net effect of disease-related symptom burden and treatment side effects. The evaluation of disease- and treatment-related symptoms, patients’ functional ability and interference in function due to symptom burden, and overall perceived well-being can greatly enhance our understanding of the benefits and costs of new treatment approaches. An extensive body of literature exists to indicate that provider-rated toxicities underestimate toxicity severity [7, 8]. Agreement among patient- and clinician-rated symptom severity has been demonstrated to be low, with the lowest agreement observed for the most subjective symptoms [9]. Previous cooperative oncology group trials evaluating treatment for metastatic breast cancer have demonstrated that patients report higher levels of toxicity than reflected in provider ratings [10]. Given this, it is important to determine whether added toxicities from treatments added to standard therapy (in this case adding bevacizumab to paclitaxel) is associated with additional side effect burden from the patient perspective. It appears that the answer is no. Patient-reported outcomes collected longitudinally while on chemotherapy can help provide for a more appropriate valuing of treatments by generating a measure of impact on symptoms (whether disease- or treatment-induced) and function. This information must then be included with clinical efficacy data to estimate the value of the therapeutic advance.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Public Health Service Grants (Grant numbers CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA49883, and CA16116) from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, and by Genentech, Inc. David Cella, Ph.D. consulting honoraria received research funding from Genentech, Inc. Kathy Miller, M.D. consulting honoraria and speaker's bureau from Genentech, Inc. No other authors have disclosures to report.

Footnotes

This study was conducted for the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Primary analysis of this study was reported in Miller K et al.: New England Journal of Medicine, 2007, 357 (26), 2666–2676.

Contributor Information

David Cella, Department of Medical Social Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg Medical School, 625 N. Michigan Avenue, Suite 2700, Chicago, IL 60611, USA; Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Molin Wang, Harvard School of Public Health and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Lynne Wagner, Department of Medical Social Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg Medical School, 625 N. Michigan Avenue, Suite 2700, Chicago, IL 60611, USA; Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Kathy Miller, Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Cancer Center, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Breast cancer facts & figures. American Cancer Society, Inc.; Atlanta: 2007–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevaczumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner L, Wang M, Miller K, et al. Health-related quality of life among patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving paclitaxel versus paclitaxel plus bevacizumab: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Study E2100. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100s(suppl) doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1725-6. abstr 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Shneyer L. An alternative parameterization of the general linear mixture model for longitudinal data with non-ignorable drop-outs. Stat Med. 2001;20:1009–1021. doi: 10.1002/sim.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schluchter MD, Greene T, Beck GJ. Analysis of change in the presence of informative censoring: application to a longitudinal clinical trial of progressive renal disease. Stat Med. 2001;20:989–1007. doi: 10.1002/sim.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:974–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingham J, Portenoy RK. The measurement of pain and other symptoms. In: Doyle D, Hanks G, MacDonald N, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1998. pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Symptom Management in Cancer: Pain, Depression, and Fatigue, July 15–17, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1110–1117. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn EA, Cella D, Chassany O, et al. Precision of health-related quality-of-life data compared with other clinical measures. Clinical significance consensus meeting group. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1244–1257. doi: 10.4065/82.10.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sledge G, Neuberg D, Bernardo P, et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and the combination of doxorubicin and paclitaxel as front-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: an intergroup trial (E1193). J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:588–592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]