Abstract

Objective

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is designed primarily as a clinical tool. Yet high rates of diagnostic “crossover” among the anorexia nervosa subtypes and bulimia nervosa may reflect problems with the validity of the current diagnostic schema, thereby limiting its clinical utility. This study was designed to examine diagnostic crossover longitudinally in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa to inform the validity of the DSM-IV-TR eating disorders classification system.

Method

A total of 216 women with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa were followed for 7 years; weekly eating disorder symptom data collected using the Eating Disorder Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Examination allowed for diagnoses to be made throughout the follow-up period.

Results

Over 7 years, the majority of women with anorexia nervosa experienced diagnostic crossover: more than half crossed between the restricting and binge eating/purging anorexia nervosa subtypes over time; one-third crossed over to bulimia nervosa but were likely to relapse into anorexia nervosa. Women with bulimia nervosa were unlikely to cross over to anorexia nervosa.

Conclusions

These findings support the longitudinal distinction of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa but do not support the anorexia nervosa subtyping schema.

With the preparation for the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders under way, the validity of the DSM-IV-TR classification system for eating disorders has been called into question (1). In the current diagnostic system, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are recognized as full syndrome eating disorders with specific criteria sets. DSM is designed to serve primarily as a clinical tool, providing “clear descriptions of diagnostic categories in order to enable clinicians and investigators to diagnose, communicate about, study, and treat people with various mental disorders” (DSM-IV-TR, p. xxxvii). Yet the high rates of diagnostic “crossover,” such as movement from anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa, may reflect problems with the validity of the current diagnostic schema for eating disorders, thereby limiting its utility.

Several prospective longitudinal studies and retrospective reports have indicated substantial crossover between the eating disorders. Research findings suggest that 20%–50% of individuals with anorexia nervosa will develop bulimia nervosa over time (2–4). Estimates of longitudinal crossover from bulimia nervosa to anorexia nervosa are lower; one large study found that up to 27% of those with an initial diagnosis of bulimia nervosa cross over to anorexia nervosa (5), but a review suggested that this type of crossover generally occurs in less than 10% of initial cases of bulimia nervosa (6). Research also indicates that cross-over is common between diagnostic subtypes, with up to 62% of patients with restricting-type anorexia nervosa developing binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa (7).

In the existing literature, it is unclear whether diagnostic crossover is a one-time occurrence or whether crossover continues throughout the course of illness. Preliminary studies suggest that initial crossover between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa most often occurs within the first 5 years of illness (2, 5). Typically, the literature has reported crossover as a single occurrence—that is, studies have generally not reported whether individuals are likely to remain stable with their new diagnosis following initial crossover or whether they are likely to experience crossover repeatedly. This information is important because it may indicate whether eating disorder symptoms (and therefore diagnoses) are initially in flux but become stable after a certain period or whether they continue to be unstable throughout the course of illness.

A notable exception in the literature is a study by Milos and colleagues (8) that examined crossover at two follow-up points over a period of 30 months and found that cross-over was common and recurrent. Among women with anorexia nervosa, Milos et al. found that 16% had crossed over to bulimia nervosa by 12 months of follow-up and that an additional 7% had crossed over by 30 months, by which point only one of those who had crossed over at 12 months still met criteria for bulimia nervosa, indicating recurrent crossover. Among women with bulimia nervosa, 6% had crossed over to anorexia nervosa at 12 months, and by 30 months the majority of these women still met criteria for anorexia nervosa; there were no new cross-overs from bulimia nervosa to anorexia nervosa between 12 and 30 months. Data on crossover between the anorexia nervosa subtypes were not reported. In addition to highlighting recurrent crossover, this study demonstrated that over as brief a period as 12 months, nearly half of those with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa no longer met full criteria for their intake diagnosis: they had either crossed over to another eating disorder diagnosis or experienced a remission of symptoms. This finding is supported by a large body of longitudinal research demonstrating the high frequency of relapse in eating disorders, suggesting that individuals with eating disorders often move in and out of illness states over time (9–12).

Given the reported high rates of diagnostic crossover and the fact that a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa is made on the basis of positive criteria for a minimum of just 3 months, it is possible that symptom presentation—and therefore assigned diagnosis—at any given time is unstable. This instability may render the information conveyed by the assigned diagnosis less than optimally meaningful. High crossover rates, as well as shared clinical features among the eating disorders, have led some to postulate that eating disorders may be better conceptualized as a single disorder, perhaps marked by a weight specifier (13, 14). A single general eating disorder diagnosis may not be ideal, however, particularly if there are important diagnostic subgroups within such a broad category.

To our knowledge, no study has explicitly examined the frequency of diagnostic crossover longitudinally using weekly symptom data. Therefore, we sought to carefully describe the diagnostic course of a large sample of women with an initial diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa followed for 7 consecutive years. A longitudinal picture of diagnostic stability, crossover, and the likelihood of recurrent crossover could provide information to support or challenge the validity of the current DSM classification schema. We hypothesized that diagnostic cross-over—and recurrent crossover—would continue to occur over time and would differ on the basis of initial diagnosis. Specifically, we proposed that individuals with anorexia nervosa would be more likely to develop bulimia nervosa than vice versa. We further predicted that individuals with anorexia nervosa would experience diagnostic crossover between the anorexia nervosa subtypes and that those with binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa would be more likely to develop bulimia nervosa compared with those with restricting-type anorexia nervosa.

Method

A total of 294 treatment-seeking women were recruited for participation in a longitudinal study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa between 1987 and 1991; after receiving a complete description of the study, 246 (84%) of them provided written consent to participate. Of these, 216 (88%) were followed for 7 consecutive years and are included in this analysis. At intake, all participants met DSM-III-R criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa; when participants were reclassified according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, 88 (41%) met criteria for anorexia nervosa (40 with the restricting type and 48 with the binge eating/purging type), and 128 (59%) met criteria for bulimia nervosa. Demographic data on this sample have been presented elsewhere (15).

The Eating Disorders Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation, a modified version of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (16), was used to assess symptoms at intake and to assign DSM-IV-TR diagnoses during the follow-up period. It was administered by trained interviewers every 6 months, in person whenever possible. This instrument yielded weekly psychiatric status rating scores (ordinal, symptom-oriented scale scores based on Research Diagnostic Criteria ratings [17]) for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa for each participant, starting 8 weeks prior to study entry. Psychiatric status ratings range from 0 to 6 for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, where 0=no history of the disorder; 1=a past disorder with no current symptoms; 2=residual symptoms (e.g., minor eating disorder cognitions without current behavioral symptoms); 3=partial symptoms (i.e., does not meet full criteria; e.g., for anorexia nervosa is ≥90% ideal body weight with significant cognitive symptoms; for bulimia nervosa, experiences binge eating and/or compensatory behaviors 1–3 times a month with significant cognitive symptoms); 4=marked symptoms (just misses full criteria: e.g., for anorexia nervosa is >85% ideal body weight with significant cognitive symptoms; for bulimia nervosa, experiences binge eating and compensatory behaviors 4–7 times a month); 5 and 6=full criteria, depending on symptom severity or degree of impairment (e.g., for anorexia nervosa, a 5 would indicate ≤85% ideal body weight, and a 6 would indicate ≤75% ideal body weight; for bulimia nervosa, a 5 would indicate binge eating/compensatory behaviors two or more times a week, and a 6 would indicate daily binge eating/compensatory behaviors).

DSM-IV-TR diagnoses were assigned weekly (i.e., recomputed for each week of the 7 years of the study) using the maximum psychiatric status rating scores for the current week and the preceding 12 weeks—that is, a 3-month period, in accordance with the DSM-IV-TR duration criterion. DSM-IV-TR diagnoses were assigned as follows: anorexia nervosa, restricting type, was assigned when the maximum anorexia nervosa psychiatric status rating was ≥5 and the maximum bulimia nervosa rating was ≤2. Anorexia nervosa, binge eating/purging type, was assigned when the maximum anorexia nervosa psychiatric status rating was ≥5 and the maximum bulimia nervosa rating was ≥3. Bulimia nervosa was assigned when the bulimia nervosa psychiatric status rating was ≥5 and the maximum anorexia nervosa rating was ≤4. Partial recovery was assigned when the maximum psychiatric status rating for both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa was 3 or 4. Full recovery was assigned when the maximum psychiatric status rating for both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa was ≤2.

The study methods have been described in detail elsewhere (9, 15).

Statistical Analyses

Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to examine between-group differences in baseline characteristics. For all analyses, comparisons were made between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and between the anorexia nervosa subtypes.

Results

Sample Characteristics at Baseline

The mean age of the sample was 24.70 years (SD=6.72); participants with anorexia nervosa (mean age=23.93, SD=7.26) were younger on average than those with bulimia nervosa (mean age=25.21, SD=6.32; Kruskal-Wallis p=0.02). The mean duration of illness was 6.00 years (SD=5.30) for participants with anorexia nervosa and 6.73 years (SD=6.36) for those with bulimia nervosa, which was not significantly different between groups. At intake, the mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) score was 51.92 (SD=10.30); there were no differences in GAF scores between women with anorexia nervosa (mean=50.48, SD=10.68) and those with bulimia nervosa (mean=52.68, SD=9.93). There were no significant differences between the anorexia nervosa subtypes on any of these intake characteristics.

Diagnostic Crossover

Figures 1–3 present diagnostic course on the basis of intake diagnosis, including crossover among the DSM-IV-TR eating disorder diagnoses and progression to partial and full recovery.

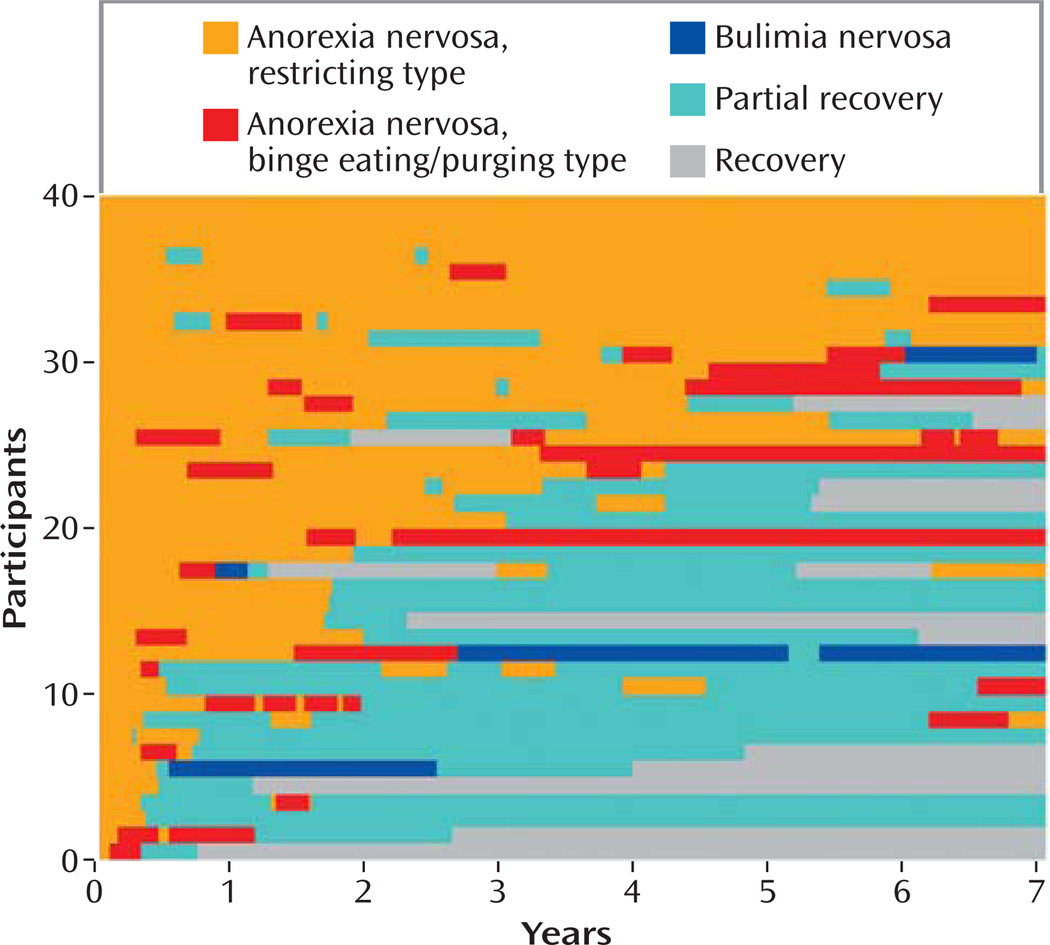

FIGURE 1.

Longitudinal Course and Crossover for Participants With an Intake Diagnosis of Anorexia Nervosa, Restricting Type (N=40)a

a Each row in the figure represents one participant.

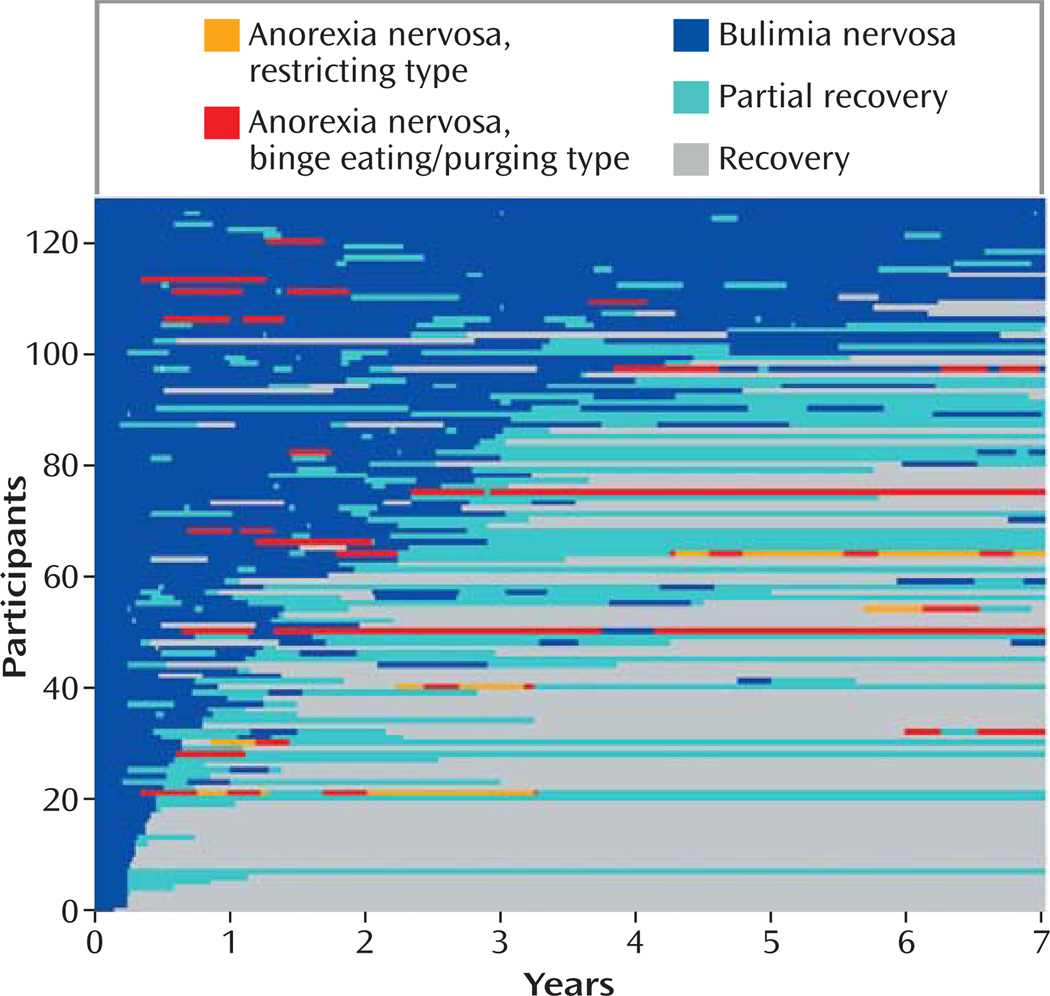

FIGURE 3.

Longitudinal Course and Crossover for Participants With an Intake Diagnosis of Bulimia Nervosa (N=128)a

a Each row in the figure represents one participant.

Anorexia nervosa

Over 7 years of follow-up, 72.73% (N=64) of participants with an intake diagnosis of anorexia nervosa experienced diagnostic crossover: 48.86% (N=43) crossed over between the anorexia nervosa subtypes, and 34.09% (N=30) crossed over from anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa. Note that a subset of those with anorexia nervosa experienced crossover between the anorexia nervosa subtypes and from anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa. Figures 1 and 2 depict the longitudinal course of anorexia nervosa by subtype.

FIGURE 2.

Longitudinal Course and Crossover for Participants With an Intake Diagnosis of Anorexia Nervosa, Binge Eating/Purging Type (N=48)a

a Each row in the figure represents one participant.

Among participants with an intake diagnosis of restricting-type anorexia nervosa, 57.5% (N=23) experienced crossover during follow-up: 55% (N=22) crossed over from restricting anorexia nervosa to binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa, and 10% (N=4) crossed over to bulimia nervosa. Among those with an intake diagnosis of binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa, the vast majority (N=41; 85.42%) experienced crossover during follow-up: 43.75% (N=21) crossed over from the binge eating/purging type to the restricting type of anorexia nervosa, and 54.17% (N=26) crossed over to bulimia nervosa.

As Figures 1 and 2 show, diagnostic crossover between the anorexia nervosa subtypes was common for women with the restricting type and the binge eating/purging type alike. Furthermore, crossover between the subtypes was bidirectional and recurrent throughout the follow-up period. Crossover from anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa was directly preceded by a period of binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa for most women with anorexia nervosa who crossed over to bulimia nervosa and was never directly preceded by a period of restricting-type anorexia nervosa; even among those with an intake diagnosis of restricting-type anorexia nervosa, crossover to the binge eating/purging type prior to crossover to bulimia nervosa was likely. For some, crossover from anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa preceded a progression to partial and full recovery; however, for approximately half, cross-over to bulimia nervosa was followed by crossover back to anorexia nervosa. Taken together, Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate that for those with an intake diagnosis of anorexia nervosa of either subtype, diagnostic crossover was not a one-time occurrence and was probable throughout the follow-up period.

Figures 1 and 2 also highlight the fact that in addition to diagnostic crossover, movement from anorexia nervosa to partial recovery was common, occurring in 78.41% (N=69) of those with anorexia nervosa. Women who experienced partial recovery represented 82.5% (N=33) of those with restricting-type anorexia nervosa at intake and 75% (N=36) of those with binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa at intake. Progression to full recovery was less common, occurring in 27.27% (N=24) of women with anorexia nervosa. Women who moved to full recovery represented 32.5% (N=13) of those with an intake diagnosis of restricting-type anorexia nervosa and 22.92% (N=11) of those with an intake diagnosis of binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa.

Bulimia nervosa

Figure 3 depicts the longitudinal course of bulimia nervosa. Over 7 years of follow-up, only a small minority of participants with an intake diagnosis of bulimia nervosa (14.06%; N=18) experienced diagnostic crossover to anorexia nervosa. All of these women with bulimia nervosa who crossed over did so to binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa, and a subset (3.91%; N=5) also experienced crossover to restricting-type anorexia nervosa. Similar to those with an intake diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, crossover among those with bulimia nervosa was not a single event and occurred throughout follow-up. While crossover to anorexia nervosa was un-common, for women with bulimia nervosa the more common trajectory was to partial recovery (occurring in 82.81% [N=106] during follow-up) or full recovery (occurring in 65.63% [N=84] during follow-up).

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to assess the longitudinal course of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa with regard to diagnostic crossover, which may have implications for the validity of the current DSM classification system and thus might be used to inform its revision. Indeed, our findings provide partial validation for the current classification schema: the longitudinal data generally support the distinctiveness of the diagnostic categories of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. However, less support was provided for the current anorexia nervosa subtyping system.

During 7 years of follow-up, nearly three-quarters of women with an intake diagnosis of anorexia nervosa experienced diagnostic crossover. Approximately half crossed over between the anorexia nervosa subtypes, and this crossover was bidirectional, recurrent, and probable throughout the follow-up period. One-third of those with an intake diagnosis of anorexia nervosa experienced crossover to bulimia nervosa; while crossover from restricting-type anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa was unlikely, just over one-half of those with an intake diagnosis of binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa experienced crossover to bulimia nervosa. Notably, approximately half of those with anorexia nervosa who crossed over to bulimia nervosa did so in the course of progressing to partial or full recovery, whereas the other half who experienced crossover to bulimia nervosa were likely to cross back over into anorexia nervosa. Women with bulimia nervosa were unlikely to develop anorexia nervosa during follow-up.

The relatively lower frequency of crossover between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa during follow-up as well as the differential rates of full recovery reported here and elsewhere (3, 4, 9, 10) support the distinctiveness of these two eating disorders. Although one-third of those with anorexia nervosa at intake prospectively developed bulimia nervosa, many of these women were likely to cross back (i.e., relapse) into anorexia nervosa. These data raise the possibility that the transition from anorexia nervosa (particularly the binge eating/purging type) to bulimia nervosa may not represent a change in disorder but rather a change in stage of illness: in practice, the primary difference between binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa is weight and the associated amenorrhea criterion. The long-term risk of relapse into anorexia nervosa suggests that a lifetime history of anorexia nervosa may carry important prognostic information; even after crossing over to bulimia nervosa, these women remain vulnerable to relapsing into anorexia nervosa. This finding supports the validity of distinguishing between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa and suggests the clinical relevance of noting a lifetime history of anorexia nervosa in individuals, even when the low weight criterion is no longer met (18).

The frequency of crossover between restricting-type and binge eating/purging-type anorexia nervosa suggests that these two subtypes may not be unique diagnostic groups. Previous research has indicated that the restricting type may represent an earlier phase in the course of illness than the binge eating/purging type, as those with the restricting type tend to be younger, with a shorter duration of illness (7). Yet the data reported here suggest that both the restricting type and binge eating/purging type may be phases (often recurrent) in the illness course of anorexia nervosa, as those with the binge eating/purging type often experienced periods of dietary restriction in the absence of regular binge/purge behaviors throughout their illness, just as those with the restricting-type illness were likely to experience periods of regular binge/purge behaviors. While acknowledging that the presence or absence of regular binge/purge behavior may be clinically useful, the finding that these behaviors come and go during the course of illness in women with anorexia nervosa suggests that the subtypes are not distinctive disorders.

Yet the question of whether anorexia nervosa can and should be meaningfully subtyped warrants further consideration. Individuals with restricting anorexia nervosa who have no history of regular binge/purge symptoms and are unlikely to develop these symptoms, irrespective of follow-up duration, may constitute a small subset of those with anorexia nervosa. The nature of any meaningful differences (e.g., prognostic, genetic, and so on) between this group and those with restricting anorexia nervosa who do develop regular binge/purge symptoms during their course of illness is an area in need of further study.

Strengths and limitations of this study warrant acknowledgment. A clear strength is the comprehensive assessment of eating disorder symptoms collected over a longitudinal period of follow-up in a large sample of women with eating disorders. A unique strength is the fact that weekly symptom data were available, which allowed us to assign eating disorder diagnoses to these women and carefully examine diagnostic crossover. An additional strength is the high retention rate during the 7-year follow-up period. Among the limitations of this study was that bulimia nervosa subtypes were not examined because of the low frequency of nonpurging bulimia. Additionally, data collection for this study began in 1986, prior to the establishment of the eating disorder not otherwise specified diagnostic category. Thus the sample included only women with an intake diagnosis of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, which precluded longitudinal examination of women presenting for the treatment of eating disorder not otherwise specified. A careful examination of eating disorder not otherwise specified and its distinctiveness from partial recovery in women with a lifetime history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa is planned as a future investigation. Additional limitations were that all participants in this study were patients who sought treatment and that the mean duration of illness was approximately 6 years. Our findings may not generalize to community samples or to samples of individuals who have been ill for shorter periods. Participants received a wide range of treatment during the follow-up period (19); the possible impact of treatment on cross-over would be of interest, although it was outside the scope of this naturalistic study.

As the diagnostic criteria of eating disorders come under increasing scrutiny in preparation for the next revision of DSM, careful examination of the current diagnostic entities is needed. The longitudinal data we present here support the diagnostic distinction between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, but they do not validate the current anorexia nervosa subtyping schema. Future research might continue to explore the longitudinal validity of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and the anorexia nervosa diagnostic subtypes (perhaps employing different viable definitions of the subtypes) and extend these studies to include more heterogeneous samples of women, including those with a diagnosis of eating disorder not otherwise specified.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIMH grant 5R01-MH-38333-05.

Footnotes

Presented at the NIMH Workshop on the Classification of Eating Disorders, Rockville, Md., June 2006; the International Conference on Eating Disorders, Baltimore, Md., May 2007; and the 160th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, San Diego, May 19–24, 2007.

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Walsh BT. DSM-V from the perspective of the DSM-IV experience. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:S3–S7. doi: 10.1002/eat.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Fear J, Pickering A. Predictors of the development of bulimia nervosa in women with anorexia nervosa. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:704–707. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckert ED, Halmi KA, Marchi P, Grove W, Crosby R. Ten-year follow-up of anorexia nervosa: clinical course and outcome. Psychol Med. 1995;25:143–156. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strober M, Freeman R, Morrell W. The long-term course of severe anorexia nervosa in adolescents: survival analysis of recovery, relapse, and outcome predictors over 10–15 years in a prospective study. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:339–360. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199712)22:4<339::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tozzi F, Thornton LM, Klump KL, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Kaplan AS, Strober M, Woodside DB, Crow S, Mitchell J, Rotondo A, Mauri M, Cassano G, Keel P, Plotnicov KH, Pollice C, Lilenfeld LR, Berrettini WH, Bulik CM, Kaye WH. Symptom fluctuation in eating disorders: correlates of diagnostic crossover. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:732–740. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keel PK, Mitchell JE. Outcome in bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:313–321. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eddy KT, Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Delinsky SS, Franko DL, Herzog DB. Longitudinal comparison of anorexia nervosa subtypes. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:191–201. doi: 10.1002/eat.10016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milos G, Spindler A, Schnyder U, Fairburn CG. Instability of eating disorder diagnoses: prospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:573–578. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzog DB, Dorer DJ, Keel PK, Selwyn S, Ekeblad ER, Flores AT, Greenwood DN, Burwell RA, Keller MB. Recovery and relapse in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: a 7.5-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:829–837. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Franko DL, Jackson SC, Herzog DB. Postremission predictors of relapse in women with eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2263–2268. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Hedlund S. Twelve-year course and outcome predictors of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39:87–100. doi: 10.1002/eat.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fichter MM, Quadflieg N. Twelve-year course and outcome of bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1395–1406. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:509–528. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzog DB, Sacks NR, Keller MB, Lavori PW, von Ranson KB, Gray HM. Patterns and predictors of recovery in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:835–842. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, Mc-Donald-Scott P, Andreasen NC. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation: a comprehensive interview for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 3rd ed, updated. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eddy KT, Dorer DJ, Franko DL, Tahilani K, Thompson-Brenner H, Herzog DB. Should bulimia be subtypes by history of anorexia nervosa? A longitudinal validation. Int J Eat Disord. doi: 10.1002/eat.20422. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Eddy KT, Delinsky SS, Franko DL, Blais MA, Keller MB, Herzog DB. Predictors of treatment utilization among women with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:140–142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]