Abstract

The arginine deiminase system (ADS) is of critical importance in oral biofilm pH homeostasis and microbial ecology. The ADS consists of three enzymes. Arginine is hydrolyzed by AD (ArcA) to generate citrulline and ammonia. Citrulline is then converted to ornithine and carbamoylphosphate via ornithine carbamoyltransferase (ArcB). Finally, carbamate kinase (ArcC) transfers a phosphate from carbamoylphosphate to ADP, yielding ATP. Ammonia production from this pathway protects bacteria from lethal acidification, and ATP production provides a source of energy for the cells. The purpose of this study was to initiate a characterization of the arc operon of Streptococcus rattus, the least cariogenic and sole ADS-positive member of the mutans streptococci. Using an arcB gene fragment obtained by degenerate PCRs, the FA-1 arc operon was identified in subgenomic DNA libraries and sequence analysis was performed. Results showed that the genes encoding the AD pathway in S. rattus FA-1 are organized as an arcABCDT-adiR operon gene cluster, including the enzymes of the pathway, an arginine-ornithine antiporter (ArcD) and a putative regulatory protein (AdiR). The arcA transcriptional start site was identified by primer extension, and a σ70-like promoter was mapped 5′ to arcA. Reverse transcriptase PCR was used to establish that arcABCDT could be cotranscribed. Reporter gene fusions and AD assays demonstrated that the operon is regulated by substrate induction and catabolite repression, the latter apparently through a CcpA-dependent pathway.

The oral cavity is a diverse ecosystem in which resident bacteria must withstand constant changes in environmental pH and energy source in order to survive. Following a carbohydrate challenge, the pH of the mouth can drop to values below 4, mainly due to glycolysis by Streptococcus mutans and other acid-tolerant bacteria (34, 38). Repeated acidification of dental plaque can contribute to demineralization of tooth enamel and development of dental caries (28). Oral bacteria have developed a variety of strategies to cope with environmental acidification, including mounting an adaptive acid tolerance response and production of alkali (9). A relatively small, yet abundant, subset of oral bacteria uses one of two primary ammonia-generating mechanisms: the hydrolysis of urea by urease, or catabolism of arginine via the arginine deiminase system (ADS) (9). The ADS is thought to be a critical factor in oral biofilm pH homeostasis that may inhibit the emergence of a cariogenic flora (9).

Genes encoding the ADS are commonly arranged as an operon, although the gene order varies among bacteria (4, 19, 30, 40, 42). Typically, the operons contain arcA, encoding arginine deiminase (AD), which hydrolyzes arginine to generate citrulline and ammonia. A second gene, arcB, encodes a catabolic ornithine carbamoyltransferase (cOTC), which converts citrulline to ornithine and carbamoylphosphate. Finally, arcC encodes a catabolic carbamate kinase, which transfers a phosphate group from carbamoylphosphate to ADP, generating ATP, CO2, and ammonia. Many ADS operons also include a fourth gene encoding an arginine-ornithine antiporter (arcD). In some organisms, a gene encoding a putative aminopeptidase (arcT) and one encoding a transcriptional regulator of the Crp/Fnr family (arcR) or ArgR/AhrC family are also associated with the ADS gene cluster (19, 42). The generation of ATP in accordance with equimolar hydrolysis of substrate allows the use of arginine as a sole energy source. Ammonia generated from this pathway also helps neutralize the cytoplasm (12) and alkalinize the surroundings. Thus, arginine metabolism via the ADS has been shown to protect bacteria from acid killing (12).

The ADS has been identified in a variety of prokaryotes (1), although the physiological role of the system, as well as the mode of regulation, can be different between species. In the oral cavity, the ADS is believed to be used by plaque bacteria associated with dental health, such as Streptococcus gordonii and Streptococcus sanguis, to counteract acid production by cariogenic mutans streptococci and lactobacilli (9). Regulation of the ADS in these bacteria is highly dependent on growth conditions. AD activity in S. gordonii and S. sanguis is induced by arginine and is subject to carbon catabolite repression (CCR), with lower activity observed in the presence of the repressing sugar glucose (19, 21). In S. gordonii, the trans-acting ArcR protein activates AD gene expression and CcpA represses expression in the presence of glucose (19).

Streptococcus rattus is similar to other ADS-positive oral bacteria in that it is relatively acid sensitive in the absence of arginine and has not been linked to caries development in humans. However, S. rattus is a member of the mutans group of streptococci and is most closely related to S. mutans, which is noted for exceptional cariogenicity and acid tolerance. In fact, a major factor distinguishing S. rattus from S. mutans is the ability to catabolize arginine via the ADS (16). By initiating a molecular characterization of the arc operon of S. rattus FA-1, a clearer understanding of the evolution and diversity of the mutans streptococci in relation to pH adaptation will be obtained.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and reagents.

S. rattus FA-1 was grown in brain heart infusion (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) broth at 37°C, in 5% CO2 and 95% air. To monitor ADS expression, wild-type S. rattus FA-1 was grown in a low-carbohydrate tryptone-vitamin (TV)-based broth (11) containing 0.2 or 2% glucose or galactose, with or without 10 mM arginine. Recombinant Escherichia coli strains were maintained on L agar supplemented, when indicated, with 25 μg of chloramphenicol (Cm) ml−1 or 50 μg of kanamycin (Km) ml−1. All chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.).

DNA manipulations.

Genomic DNA from S. rattus FA-1 was isolated as previously described (13). Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli by the method of Birnboim and Doly (6). Plasmid DNA used in sequencing reactions was prepared from E. coli DH10B using the QIAprep Spin plasmid kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.). Cloning and electrophoretic analysis of DNA fragments were carried out according to established protocols (3). Southern hybridization and high-stringency washes were performed as previously described (27). Restriction and DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Life Technologies Inc. (Rockville, Md.) or New England Biolabs (Beverley, Mass.).

To prepare subgenomic DNA libraries of S. rattus FA-1, chromosomal DNA was digested to completion using XbaI or EcoRV. The digested DNA fragments were separated on agarose gels, and the XbaI fragments of 6 to 8 kbp or EcoRV fragments of 4 to 5 kbp were enriched by gel purification using the Elu-Quik DNA purification kit (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). The isolated DNA fragments were ligated onto XbaI- or HincII-digested, phosphatase-treated pSU20 (5), respectively. The ligation mixtures were used to transform E. coli DH10B, and Cm-resistant transformants were selected.

Development of an arcB-specific probe.

An internal fragment of the S. rattus FA-1 arcB gene, encoding cOTC, was generated by PCRs using degenerate primers based on alignments of known anabolic and catabolic OTCs (19). Using this fragment as a probe, a lambda clone containing the arcA gene and a partial arcB gene was identified (data not shown). Specific primers internal to arcB were designed, and the subsequent PCR product was used to screen a subgenomic library. Primer arcBS, 5′-CAAGTATTTCAGGGACGC-3′, encoded amino acid (aa) residues 3 through 8 of cOTC. Primer arcBAS, 5′-CATCTGTCAAGCCATTCC-3′, encoded the antisense sequence, corresponding to aa residues 127 to 132 of cOTC. Each reaction consisted of 25 cycles at a stringent annealing temperature (55°C). The product with the correct predicted size was gel purified prior to cloning into pCRII to generate pJZ22. Southern blot analysis confirmed hybridization of the PCR product to the S. rattus FA-1 chromosome at high stringency. Sequence analysis and BLAST searches were performed to confirm that the product shared high degrees of homology with other cOTCs.

RNA isolation, primer extension, and reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis.

The protocol used to isolate total RNA from S. rattus FA-1 was the same as that originally described for Streptococcus salivarius RNA isolation (15). S. rattus FA-1 was grown to mid-exponential phase in TV medium containing 2% galactose and 1% arginine. Primer extension analysis was used to map the arcA transcription initiation site. Primer ArcAS (5′-GACGATGTAACATTACCTTCTT-3′) encoded the antisense sequence of arcA located 50 bases downstream from the translational start site. Incubation of radiolabeled primers with 50 μg of total RNA at 42°C for 90 min was followed by reverse transcription, and the products were separated by electrophoresis and disclosed by autoradiography. A DNA sequencing reaction using the same primer was included on the gel to allow identification of the start site.

To determine if the arc genes of S. rattus FA-1 could be cotranscribed, RT-PCR was performed using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). RNA was isolated from S. rattus FA-1 grown in TV plus 2% galactose and 1% arginine. PCR amplification of the cDNA was performed using various primer pairs: arcABS (5′-CTGTGTATGTCTATGCCATTTG-3′) and arcABAS (5′-AGCTAGGAAACTGCGTCCCT-3′), arcDTS (5′-TTTAGACTCTTTACAGGACAGATT-3′) and arcDTAS (5′-TGAATATTCATCTGTTTACCCCTT-3′), and arcTadiRS (5′-AGTGAGTTGTCTGAGTTTCTA-3′) and arcTadiRAS (5′-TTTATCTTACTTTGGCGCAATA-3′), flanking the intergenic region of arcAB, arcDT, and arcTadiR, respectively.

Construction of promoter fusions and CAT assays.

The arcA promoter and deletion derivatives were amplified via recombinant PCR (23) using sense primers (arcASacI-S400, TTGCTCTAGAGCTCTCAAATGACAGAA; arcASacI-S150, TTATAAATTCGAGCTCCAAAAAACGTGAA; and arcASacI-S100, TAAATAACAATTCGAGCTCGAAAAAAATCTTA) in conjunction with the antisense primer arcABamHI-AS (TTTTGAGTCATGGATCCTACTCCTTTCGAT). These primers allowed insertion of SacI and BamHI restriction sites (bold) to facilitate cloning. The PCR products were ligated to the 5′ end of a promoterless chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene (cat) from Staphylococcus aureus (20) and cloned onto the integration vector pMJB8A (14). The constructs were then electroporated into E. coli DH10B cells, screened for the correct configurations, and then introduced into S. gordonii DL-1 by natural transformation. S. rattus FA-1 cultures were grown in TV medium containing 2% glucose or galactose, with or without 1% arginine, to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6.

Biochemical assays.

S. rattus FA-1 was grown in TV medium supplemented with 0.2 or 2% glucose or galactose, with or without 1% arginine, at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% air. AD activity was measured by monitoring production of citrulline from arginine as previously described (2). CAT assays were performed using the spectrophotometric method of Shaw (36). Enzyme activities were normalized to protein concentration, which was determined by the method of Bradford (7) using a kit (Bio-Rad) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete sequences of the arc operon and adiR reported in this article have been deposited in the GenBank database, and the accession number is AY396288.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isolation of the ADS genes of S. rattus FA-1.

To prepare a subgenomic DNA library, chromosomal DNA isolated from S. rattus FA-1 was digested to completion using various restriction enzymes. The digested DNA fragments were separated on a 0.8% agarose gel and screened for the presence of arcB by stringent hybridization with a 0.35-kbp PCR product internal to the S. rattus arcB gene. Results indicated that the arcB gene was contained on an XbaI fragment of approximately 7 kbp. To clone this fragment, a subgenomic DNA library of XbaI fragments was constructed in the intermediate-copy-number plasmid, pSU20 (5). The library was screened by colony hybridization under stringent conditions with an arcB-specific probe. A positive clone, containing a 7.0-kbp DNA insert (pJZ29), was identified. Southern blot analysis confirmed that the 7.0-kbp XbaI DNA fragment originated from S. rattus and demonstrated that the fragment was continuous on the chromosome (data not shown).

Results of DNA sequence analysis performed on the 7.0-kbp XbaI fragment indicated that this fragment contained the 3′ portion of a partial open reading frame (ORF) that shared homology with other known arcA genes, followed by five complete ORFs. To obtain genomic DNA fragments containing the complete ORF and to potentially identify other genes tightly linked to the arginine catabolism cluster, a subgenomic DNA library of EcoRV fragments was constructed and screened with a 1-kbp DNA fragment containing the 3′ portion of arcA. A 4-kbp EcoRV fragment was subsequently isolated, and a Southern blot analysis under stringent conditions confirmed that the fragment originated from S. rattus.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the ADS genes.

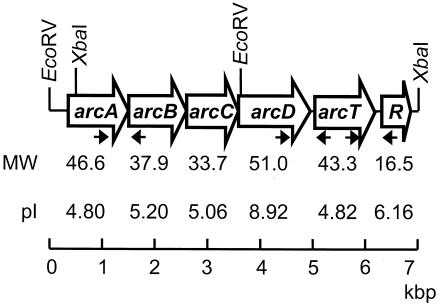

Using a series of nested deletions generated by exonuclease III, the complete sense and antisense nucleotide sequences of the 7-kbp XbaI fragment and 4-kbp EcoRV fragment were determined. The nucleotide sequences were translated and found to encode six ORFs arranged in an apparent operon (Fig. 1). Each ORF began with an ATG start codon and was preceded by a putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence. Between the fifth and sixth ORF, a stable stem-loop structure that could possibly act as a terminator was identified. Based on similarity to known arc genes, the ORFs were designated arcA, -B, -C, -D, and -T and adiR.

FIG. 1.

The S. rattus FA-1 arc operon. Restriction sites used to isolate the arc gene fragment from a subgenomic library are noted. The arrows indicate positions of primers used in RT-PCR.

The predicted amino acid sequences of the six ORFs were determined, and BLAST searches were used to identify sequence similarity to other known proteins. S. rattus AD, encoded by arcA, was 85, 84, 80, and 79% identical to the AD enzymes of Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and S. gordonii, respectively. S. rattus AD also shared homology with the AD proteins of Enterococcus faecalis, Clostridium perfringens, Bacillus licheniformis, Lactobacillus sakei, and S. aureus. Several conserved regions were identified in S. rattus ArcA, including the signature arginine deiminase motifs SEIGKLKKVML (aa 11 to 21), FTRD (aa 164 to 167), EGGD (aa 220 to 223), and MHLDTVF (aa 274 to 280) (26).

S. rattus cOTC, encoded by arcB, shared 88, 86, 85, and 85% identity with the cOTCases of S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, S. gordonii, and S. pneumoniae, respectively. Additional homologies were observed with cOTC enzymes from E. faecalis, L. sakei, B. licheniformis, and S. aureus. Conserved carbamoylphosphate binding and catalysis motifs, STRTR and HPTQ, were identified at aa residues 57 to 61 and 135 to 138, respectively (24). The conserved ornithine binding site (LHCLP)was identified at positions 270 to 274.

The carbamate kinase encoded by S. rattus arcC was 73 and 72% identical to that of S. gordonii and S. pneumoniae, respectively. Homologies were also observed with the carbamate kinases of Listeria monocytogenes, S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, S. mutans, L. sakei, and B. licheniformis. Aside from the highly conserved arginine residues at aa residues 157 and 160, no other conserved motifs were identified in the S. rattus arcC, as was the case for S. gordonii and E. faecalis (19, 31).

The arginine-ornithine antiporter encoded by S. rattus arcD shared 49 and 42% identity with those of L. sakei and S. aureus, respectively. Conservation was also observed with the arginine-ornithine antiporters of S. agalactiae, C. perfringens, and Pseudomonas putida. Twelve predicted transmembrane helices were identified in ArcD of S. rattus using the dense alignment surface method from the DAS-Transmembrane Prediction server (http://www.sbc.su.se/∼miklos/DAS) (17).

S. rattus arcT, encoding a putative peptidase, shared 58% identity with the ArcT of L. lactis and 59% identity with SMU.816, a putative aminotransferase of S. mutans UA159. Additional homologies were observed with the ArcT proteins of Lactobacillus lactis and L. sakei, as well as a Lactobacillus plantarum aminotransferase.

The amino acid sequence of an apparent regulatory protein linked to the arc operon was compared to those of regulatory proteins controlling arginine metabolism in other bacteria. The most significant level of similarity was observed with the putative S. mutans UA159 ArgR (80% identity), which apparently regulates arginine biosynthesis. The second highest identity was with ArgR of S. agalactiae (58%), followed by putative arginine repressors in S. pyogenes and S. pneumoniae and AhrC of L. lactis. The AhrC protein was originally identified in Bacillus subtilis as a repressor of the arginine biosynthetic genes (32). An AhrC homologue, ArgR, has been identified in B. licheniformis, where it both represses the anabolic ornithine carbamoyltransferase and activates arc operon expression in the presence of arginine (30). In contrast to the B. licheniformis ArgR, it is not known whether the regulatory protein associated with the arc operon in S. rattus also regulates arginine biosynthetic genes. Additionally, only a very low level of similarity was shared between S. rattus AdiR and known Crp/Fnr-like proteins, such as S. gordonii ArcR (30%) and B. licheniformis ArcR (no similarity). To avoid generating confusion of this apparent S. rattus ADS regulatory protein with the global regulator ArcR or regulators repressing arginine biosynthesis (ArgR/AhrC), we have designated this protein AdiR to reflect its putative role as a regulator of the AD gene cluster.

We analyzed the predicted amino acid sequence of S. rattus AdiR to determine if any conserved DNA or arginine binding residues were present. The conserved SR-RE motif thought to be involved in DNA contact by the E. coli ArgR (39) was found at aa residues 44 to 49 of the S. rattus AdiR, consistent with the theory that the N terminus of ArgR is involved in DNA binding. Conserved amino acid residues thought to be important for arginine binding in the E. coli ArgR (8, 41) were identified near the C terminus at positions 101 (alanine) and 124 (aspartic acid). In addition, a conserved glycine residue involved in oligomerization was identified at position 122 (41).

Most ADS genes appear to be highly regulated (4, 19, 30, 43). Three transcriptional activators of the E. faecalis arc operon have been identified, including ArcR and two ArgR/AhrC-type regulators (4). In B. lichenformis, ArgR activates arc operon expression in the presence of arginine by binding to a conserved ARG box located upstream of the arcA promoter (30). Transcriptional regulation of ADS by multiple proteins has also been proposed for B. licheniformis, as putative binding sites for both ArgR/AhrC-type and Crp/Fnr-type proteins have been identified 5′ to the transcriptional initiation site (30). ArcR, a Crp/Fnr-type transcriptional regulator, activates the arc genes by binding to a Crp-like consensus sequence upstream of the arcA promoter. We analyzed the sequence upstream of S. rattus arcA for possible ArgR or ArcR DNA binding sites. Potential binding sites for both ArgR and ArcR (22, 39) were identified 200 and 52 bases upstream of the arcA transcriptional start site, respectively (Fig. 2B). The presence of a putative Arg box (AATGAATTTATAAGTTAA) and an imperfect palindrome possibly constituting a Crp binding site (AATGCGA-N6-TCTTATT) (bases in bold match the E. coli consensus sequences) (29) suggest that the ADS in S. rattus may be under the control of a Crp/Fnr family member, in addition to an ArgR/AhrC-type protein (30), most likely the S. rattus AdiR protein. The role of these putative binding sites in regulation of the S. rattus ADS is currently under investigation.

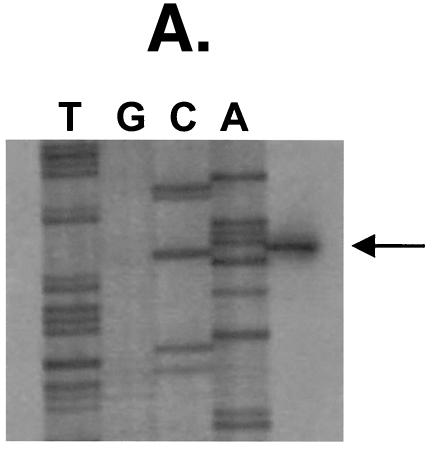

FIG. 2.

(A) Primer extension analysis of S. rattus arcA. The arrowhead indicates initiation of transcription at a G residue, 49 bases 5′ to the ATG translational start codon. (B) Upstream sequence of S. rattus FA-1 arcA, with putative regulatory elements highlighted. The −10 and −35 promoter elements are underlined, and the arrowhead indicates the transcription start site.

Localization of parcA and reporter gene fusions.

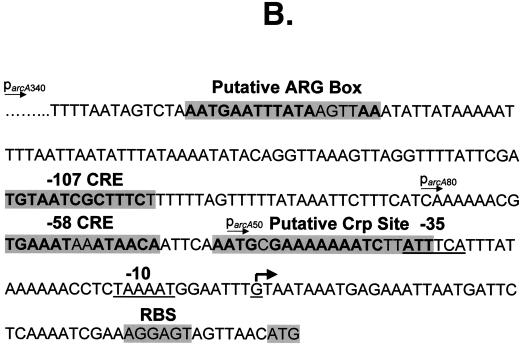

Primer extension analysis was used to map the arcA promoter region. A single band was observed corresponding to a G residue 49 bases upstream of the arcA start codon (Fig. 2A). Examination of the upstream sequence revealed a putative promoter that was most similar to σ70-type promoters. The −10 region (TAAAAT) shared 5 out of 6 bases with the consensus sequence (bold), whereas the −35 region (ATTTCA) identified 17 bases upstream of the −10 region shared only 3 bases with the consensus (bold). To determine which arc genes could be transcribed from the arcA promoter, RT-PCR analysis was performed on RNA isolated from S. rattus FA-1 grown in TV plus 2% galactose plus 1% arginine (Fig. 3). RT-PCR results suggested the presence of a polycistronic arcABCDT transcript. No transcript could be detected between the intergenic region of arcT and adiR, suggesting that adiR is transcribed from a separate promoter.

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR analysis of mRNA from S. rattus grown in TV broth containing 2% galactose and 1% arginine. Primers specific to the arc intergenic regions were used to amplify cDNA. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lanes 2 to 4, arcAB intergenic region; lanes 5 to 7, arcDT intergenic region; lanes 8 to 10, arcTR intergenic region. The order within each triplicate (2 to 4, 5 to 7, 8 to 10) is cDNA, chromosomal DNA, and a control in which a reaction containing mRNA with no RT was used in the amplification reaction.

Expression of the arc operon in L. sakei (42), as well as some oral streptococci (19), is under the control of CCR. ADS expression in these bacteria appears to be up-regulated in the presence of arginine (33) and repressed by glucose (18, 37). In AT-rich gram-positive bacteria, CCR is mediated by the trans-acting catabolite control protein A (CcpA), which binds to cis-acting catabolite response elements (cre) in the presence of preferred carbohydrate sources to regulate the expression of catabolic genes and operons (35). Two potential CcpA-dependent cre were identified at −58 (TGAAATAAATAACA) and −107 (TGTAATCGCTTTCT) relative to the arcA transcriptional start site, with bases matching the consensus shown in bold (25). The presence of these elements is consistent with the observation that the ADS in S. rattus FA-1 is regulated by CCR (10).

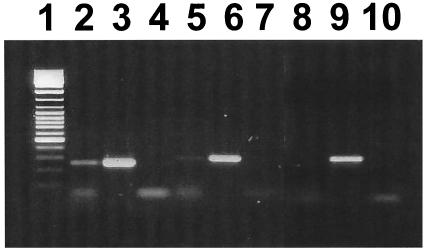

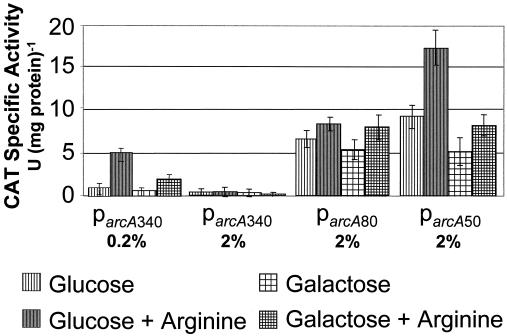

To assess the functionality of parcA and the putative cre sites found upstream of the promoter region, parcA and deletion derivatives were fused to a cat gene from S. aureus. Three arcA promoter fusions were constructed: (i) 340 bases upstream of the arcA transcriptional start site, including both putative cre sites; (ii) 80 bases upstream, including one cre site; and (iii) 50 bases upstream, lacking both cre sites. All of the promoter fusions were constructed such that expression of cat was driven by the cognate arcA ribosome binding sequence. Since an efficient system of genetic transformation has not yet been established for S. rattus FA-1, the promoter fusions were integrated into the gtfG gene on the chromosome of the naturally competent, ADS-positive organism S. gordonii DL-1 using a previously described integration vector (14). Results showed that the intact parcA was functional in S. gordonii, and deletion of the putative cre sites resulted in increased promoter activity relative to the wild type, providing evidence that expression from parcA is regulated via CcpA-dependent catabolite repression (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

CAT specific activity, in units per milligram of protein of the wild-type S. rattus FA-1 arcA promoter (parcA340) and derivatives in which one cre has been deleted (parcA80) or both cre have been deleted (parcA50). Bacterial cultures used in the CAT assays were grown in TV containing 0.2 or 2% carbohydrate, with or without 1% arginine.

Expression of AD in S. rattus.

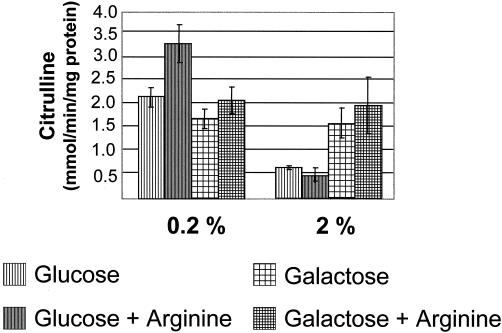

The identification of putative cre sites upstream of parcA, as well as the ADS regulation patterns observed in S. gordonii, prompted us to investigate the role of catabolite repression in S. rattus FA-1 arc regulation. Wild-type S. rattus FA-1 was grown in TV broth containing glucose or galactose, with or without supplemental arginine, to mid-exponential phase and AD activity was measured. Galactose was included in the analysis because it is not repressive for AD expression in S. gordonii (19). In wild-type S. rattus grown in 2% carbohydrate, peak AD activity was found in cells grown in galactose and arginine, while the expression level decreased by 75% in cells grown in glucose, regardless of the presence of arginine (Fig. 5). In agreement with previous studies (10, 18), catabolite repression of ADS in S. rattus FA-1 was not evident when the amount of glucose or galactose present in the growth medium was reduced to 0.2%. This differs from CCR of the ADS in other closely related oral streptococci, including S. gordonii, where inclusion of as little as 0.2% glucose in the growth medium strongly represses ADS expression. The different susceptibilities of ADS expression to CCR may reflect different physiological roles of the system in these bacteria. Specifically, susceptibility to CCR at lower carbohydrate concentrations would indicate that the ADS in S. gordonii may be primarily involved in energy generation and not acid tolerance, since the system may be repressed when conditions exist that favor low pH, i.e., higher carbohydrate availability. In contrast, a lack of repression of the ADS in the presence of comparatively high levels of sugar may allow S. rattus to derive ATP from arginine and carbohydrate concurrently, and the ammonia generated could enhance the growth in, or protect the organisms from, a low-pH environment. As shown in Fig. 4 and 5, there is some induction of the S. rattus ADS by arginine, especially at low carbohydrate concentrations, but the induction is not of the magnitude that is seen in other organisms. This observation lends credence to the idea that there are fundamental differences in regulation of ADS in S. rattus compared to that in other bacteria. Further physiological characterization of the S. rattus arc operon is ongoing to understand the contribution of the ADS to the acid tolerance of mutans streptococci.

FIG. 5.

AD enzyme activity of wild-type (WT) S. rattus FA-1 grown in TV broth containing 0.2 or 2% carbohydrate, with or without 1% arginine.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Public Health Service grant DE10362 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelal, A. 1979. Arginine catabolism by microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 33:139-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald, R. M. 1944. Determination of citrulline and allantoin and demonstration of citrulline in blood plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 156:121-142. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1989. Current protocols in molecular biology. J. Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Barcelona-Andres, B., A. Marina, and V. Rubio. 2002. Gene structure, organization, expression, and potential regulatory mechanisms of arginine catabolism in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 184:6289-6300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartolome, B., Y. Jubete, E. Martinez, and F. dela Cruz. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322. Gene 102:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birnboim, H. C., and J. Doly. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke, M., A. F. Merican, and D. J. Sherratt. 1994. Mutant Escherichia coli arginine repressor proteins that fail to bind l-arginine, yet retain the ability to bind their normal DNA-binding sites. Mol. Microbiol. 13:609-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burne, R. A., and R. E. Marquis. 2000. Alkali production by oral bacteria and protection against dental caries. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 193:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burne, R. A., D. T. Parsons, and R. E. Marquis. 1991. Environmental variables affecting arginine deiminase expression in oral streptococci, p. 276-280. In G. M. Dunny, P. P. Cleary, and L. L. McKay (ed.), Genetics and molecular biology of streptococci, lactococci, and enterococci. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 11.Burne, R. A., Z. T. Wen, Y. Y. Chen, and J. E. Penders. 1999. Regulation of expression of the fructan hydrolase gene of Streptococcus mutans GS-5 by induction and carbon catabolite repression. J. Bacteriol. 181:2863-2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casiano-Colon, A., and R. E. Marquis. 1988. Role of the arginine deiminase system in protecting oral bacteria and an enzymatic basis for acid tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1318-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, J. J., Z. X. Yang, and X. G. Jiang. 1996. A comparison of purified urease antigen and whole cell antigen of Helicobacter pylori by ELISA test—study on the application and serum diagnoses of Helicobacter pylori urease diagnostic reagent. Zhonghualiuxingbingxue Zazhi 17:44-46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, Y. Y., M. J. Betzenhauser, and R. A. Burne. 2002. cis-Acting elements that regulate the low-pH-inducible urease operon of Strepcococcus salivarius. Microbiology 148:3599-3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, Y. Y., and R. A. Burne. 1996. Analysis of Streptococcus salivarius urease expression using continuous chemostat culture. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 135:223-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coykendall, A. L. 1974. Four types of Streptococcus mutans based on their genetic, antigenic and biochemical characteristics. J. Gen. Microbiol. 83:327-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cserzo, M., E. Wallin, I. Simon, G. von Heijne, and A. Elofsson. 1997. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 10:673-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curran, T. M., Y. Ma, G. C. Rutherford, and R. E. Marquis. 1998. Turning on and turning off the arginine deiminase system in oral streptococci. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:1078-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong, Y., Y. M. Chen, J. Snyder, and R. A. Burne. 2002. Isolation and molecular analysis of the gene cluster for the arginine deiminase system from Streptococcus gordonii DL1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5549-5553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehrlich, S. D. 1978. DNA cloning in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:1433-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferro, K. J., G. R. Bender, and R. E. Marquis. 1983. Coordinately repressible arginine deiminase system in Streptococcus sanguis. Curr. Microbiol. 9:145-150. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grandori, R., T. A. Lavoie, M. Pflumm, G. Tian, H. Niersbach, W. K. Maas, R. Fairman, and J. Carey. 1995. The DNA-binding domain of the hexameric arginine repressor. J. Mol. Biol. 254:150-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higuchi, R. 1990. Recombinant PCR, p. 177-183. In M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, and J. J. White (ed.), PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 24.Houghton, J. E., D. A. Bencini, G. A. O'Donovan, and J. R. Wild. 1984. Protein differentiation: a comparison of aspartate transcarbamoylase and ornithine transcarbamoylase from Escherichia coli K-12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:4864-4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hueck, C., A. Kraus, and M. H. J. Saier. 1994. Analysis of a cis-active sequence mediating catabolite repression in gram-positive bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 145:503-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knodler, L. A., E. O. Sekyere, T. S. Stewart, P. J. Schofield, and M. R. Edwards. 1998. Cloning and expression of a prokaryotic enzyme, arginine deiminase, from a primitive eukaryote Giardia intestinalis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:4470-4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeBlanc, D. J., and L. N. Lee. 1982. Characterization of two tetracycline resistance determinants in Streptococcus faecalis JH1. J. Bacteriol. 150:835-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loesche, W. J. 1986. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 50:353-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maas, W. K. 1994. The arginine repressor of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 58:631-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maghnouj, A., T. F. de Sousa Cabral, V. Stalon, and C. Vander Wauven. 1998. The arcABDC gene cluster, encoding the arginine deiminase pathway of Bacillus licheniformis, and its activation by the arginine repressor argR. J. Bacteriol. 180:6468-6475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marina, A., M. Uriarte, B. Barcelona, V. Fresquet, J. Cervera, and V. Rubio. 1998. Carbamate kinase from Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium—cloning of the genes, studies on the enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli, and sequence similarity with N-acetyl-l-glutamate kinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 253:280-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mountain, A., and S. Baumberg. 1980. Map locations of some mutations conferring resistance to arginine hydroxamate in Bacillus subtilis 168. Mol. Gen. Genet. 178:691-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poolman, B., A. J. Driessen, and W. N. Konings. 1987. Regulation of arginine-ornithine exchange and the arginine deiminase pathway in Streptococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 169:5597-5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quivey, R. G., W. L. Kuhnert, and K. Hahn. 2001. Genetics of acid adaptation in oral streptococci. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 12:301-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saier, M. H. J., S. Chauvaux, G. M. Cook, J. Deutscher, I. T. Paulsen, J. Reizer, and J.-J. Ye. 1996. Catabolite repression and induced control in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology 142:217-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw, W. V. 1979. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase activity from chloramphenicol-resistant bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 43:737-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon, J. P., B. Wargnies, and V. Stalon. 1982. Control of enzyme synthesis in the arginine deiminase pathway of Streptococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 150:1085-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephan, R. M. 1940. Changes in hydrogen-ion concentration on tooth surfaces and in carious lesions. Am. J. Dent. 27:718-723. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian, G., and W. K. Maas. 1994. Mutational analysis of the arginine repressor of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 13:599-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vander Wauven, C., A. Pierard, M. Kley-Raymann, and D. Haas. 1984. Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants affected in anaerobic growth on arginine: evidence for a four-gene cluster encoding the arginine deiminase pathway. J. Bacteriol. 160:928-934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Duyne, G. D., G. Ghosh, W. K. Maas, and P. B. Sigler. 1996. Structure of the oligomerization and l-arginine binding domain of the arginine repressor of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 256:377-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuniga, M., M. Champomier-Verges, M. Zagorec, and G. Perez-Martinez. 1998. Structural and functional analysis of the gene cluster encoding the enzymes of the arginine deiminase pathway of Lactobacillus sakei. J. Bacteriol. 180:4154-4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuniga, M., M. Miralles, and G. Perez-Martinez. 2002. The product of arcR, the sixth gene of the arc operon of Lactobacillus sakei, is essential for expression of the arginine deiminase pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6051-6058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]