Abstract

Background: ageing is frequently accompanied by a higher incidence of infections and an increase in disability in activities of daily living (ADL).

Objective: this study examines whether clinical infections [urinary tract infections (UTI) and lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI)] predict an increase in ADL disability, stratified for the presence of ADL disability at baseline (age 86 years).

Design: the Leiden 85-plus Study. A population-based prospective follow-up study.

Setting: general population.

Participants: a total of 154 men and 319 women aged 86 years.

Methods: information on clinical infections was obtained from the medical records. ADL disability was determined at baseline and annually thereafter during 4 years of follow-up, using the 9 ADL items of the Groningen Activity Restriction Scale.

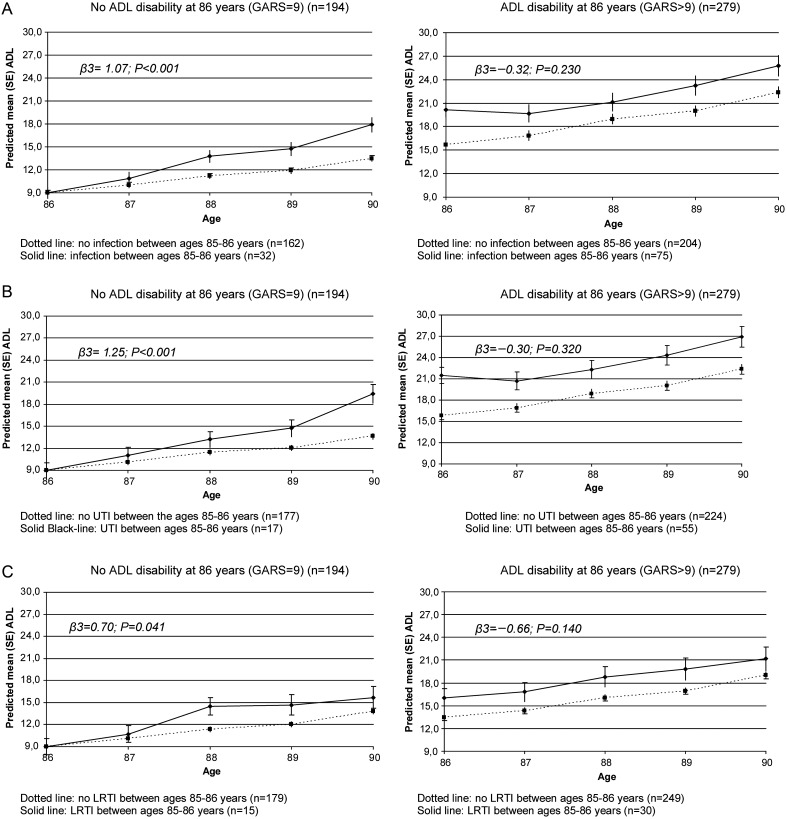

Results: in 86-year-old participants with ADL disability, there were no differences in ADL increase between participants with and without an infection (−0.32 points extra per year; P = 0.230). However, participants without ADL disability at age 86 years (n = 194; 41%) had an accelerated increase in ADL disability of 1.07 point extra per year (P < 0.001). For UTIs, this was 1.25 points per year (P < 0.001) and for LRTIs 0.70 points per year (P = 0.041). In this group, an infection between age 85 and 86 years was associated with a higher risk to develop ADL disability from age 86 onwards [HR: 1.63 (95% CI: 1.04–2.55)].

Conclusions: among the oldest-old in the general population, clinically diagnosed infections are predictive for the development of ADL disability in persons without ADL disability. No such association was found for persons with ADL disability.

Keywords: ADL disability, infections, oldest-old, general population, older people

Introduction

The oldest-old are predisposed to infectious diseases as a result of deterioration of the immune system and an increased prevalence of co-morbidity [1]. The incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) and lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) increase with age [2–6], with an exponential increase in the oldest-old [5, 6].

In vulnerable older persons, the most common bacterial infection is a UTI, with serious adverse health consequences such as delirium, dehydration, urosepsis and hospitalisation [7, 8]. Also, UTI has a high mortality rate, especially by hospitalisation [9]. Community acquired pneumonia, also highly prevalent in older persons [10], is also a frequent cause of hospitalisation and death [11, 12].

Literature on the consequences of infections on the functional decline, also highly prevalent in older persons and increasing with age [13, 14], is limited and mainly describes the impact of infections on the functional status of nursing home residents [15–17]. To our knowledge, there is no information about how infections and activities of daily living (ADL) disability co-occur in the oldest-old in the general population. Therefore, this study examines whether incident clinical infections between age 85 and 86 years contribute to an increase in ADL disability from age 86 onwards, stratified for ADL disability at baseline.

Methods

Setting and study population

The present study was conducted within the framework of the Leiden 85-plus Study. The Leiden 85-plus Study is an observational population-based prospective study of 85-year-old inhabitants of Leiden, The Netherlands. Between September 1997 and September 1999, all inhabitants of Leiden who reached the age of 85 years (birth cohort 1912–14) were invited to participate in the study. There were no selection criteria concerning health or demographic characteristics. The medical ethics committee of the Leiden University Medical Center approved the study. All participants gave informed consent for the entire study, including the use of data from their medical records for additional analyses, following explanation of the study requirements and assurance of confidentiality and anonymity. For participants with severe cognitive impairment, a guardian gave informed consent.

Participants were visited annually until the age of 90 years. They were visited at their place of residence where face-to-face interviews were conducted, cognitive testing was performed and information on socio-demographic characteristics and disabilities in daily living were obtained. Information on patients' background was obtained annually from the medical records of general practitioners (GPs) and elderly care physicians.

Infections

Information on clinical infections was obtained from the medical records. UTIs were considered present when the treating GP or elderly care physician diagnosed UTI based on signs and symptoms and urine analysis [18]. LRTI was clinically diagnosed by the treating physician based on medical history taking, physical examination and clinical judgment during a consultation with the participant [10].

ADL disability

ADL disability was measured annually with the nine ‘basic activities of daily living’ from the Groningen Activity Restriction Scale (GARS) [19], by face-to-face interviews. ADL included the following tasks: getting around the house, getting into and out of bed, standing up from a chair, going to the toilet, dressing oneself, washing hands and face, washing whole body, preparing breakfast and drinking and feeding oneself. Answers ranged from ‘fully independently, without any difficulty’ (1 point) to ‘not fully independently, only with someone's help’ (4 points); total score ranged from 9 to 36 [19]. Higher scores indicate more ADL disability. ADL disability was considered present when the participant was unable to do at least one of the nine ADL items independently (GARS >9 points).

Socio-demographic factors

During baseline interviews, a research nurse collected information about the participants' residency, income, level of education and smoking habits.

Mental status

Cognitive function was measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Scores ranged from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating impaired cognitive functioning. Severe cognitive impairment was defined as an MMSE score ≤19 points [20]. To determine the presence of depressive symptoms, the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15) was conducted. Depressive symptoms were considered present by a GDS-15 score ≥4 points [21–23], but only in those with MMSE ≥19 points.

Co-morbidity

Information on participants' medical history was obtained by standardised interviews with their treating GP or elderly care physician, and by examination of the medical records, including data on the presence of myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Information on incontinence and musculoskeletal complaints was collected in face-to-face interviews with the participants.

Statistical analysis

Differences in baseline characteristics at age 86 years, stratified for ADL disability, between the infection and no infection groups, were compared with a Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test when the cells in the 2 × 2 crosstabs were <10 observed or 5 expected counts, for categorical data. Median scores of the GARS were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Short-term effect: retrospective analysis

The short-term effect of infections on ADL disability was studied retrospectively, using ‘history of UTI or LRTI between age 85 and 86 years’ in relation to ADL disability scores at age 85 and 86 years. The short-term effect of infections on ADL disability was calculated by taking the delta in the ADL score (ADL score at 86 years minus the ADL score at 85 years), stratified for participants with and without ADL disability at age 86 years. The independent t-test was used to test differences in the mean increase in ADL scores between participants with and without infections for both groups.

Long-term effect: prospective analysis

We started the follow-up for 4 years at age 86 years to enable to study the ‘history of UTI or LRTI between age 85 and 86 years’ as a possible predictor for long-term ADL disability from age 86 years onwards. All analyses were stratified for ADL disability at age 86 years.

Cox regression models were used to analyse whether an infection between age 85 and 86 years was associated with the long-term development of ADL disability from 86 years onwards in those without ADL disability at 86 years.

The relation between infections, between age 85 and 86 years, and changes in ADL disability scores over time (4 years of follow-up) were analysed with linear mixed models (LMM). Each LMM included a term for the baseline difference in the ADL disability score for those with and without infection between age 85 and 86 years, a term for time, and a term for the interaction between infection and time. The effect of time on ADL disability reflects the annual change in ADL disability in those without infection, and is presented as the basic annual change in the ADL disability score (β2). The interaction of infection and time reflects the additional annual change in ADL disability for those with infection and is presented as additional annual change in the ADL disability score (β3).

Cox regression and LMM were adjusted for gender, living situation (independent or long-term care facility) and comorbidity (myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes mellitus, COPD, musculoskeletal complaints and incontinence).

Analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Between September 1997 and September 1999, 705 participants were eligible for participation in the Leiden 85-plus Study. Ninety-two participants refused to participate and 14 participants died before enrolment, resulting in a study population of 599 participants at the age of 85 years (response rate 87%). At age 86 years, the baseline of the present study, 551 participants are still alive. A total of 72 participants for whom valid clinical information on infections at the age of 86 years was missing were excluded. For six participants information on ADL disability at 86 years was missing, resulting in a final study population of 473 participants. The 78 participants that were not included in the present study more often had primary school education only, myocardial infarction, COPD and incontinence (data not shown).

Study population

Table 1 presents a comparison of the characteristics of the participants with and without infections between age 85 and 86 years (n = 473), at the age of 86 years stratified for participants with and without ADL disability at the age of 86 years. Almost 70% of the study population was female. In participants without ADL disability at baseline, on all but one there were no significant differences in socio-demographic factors and functioning for both the infection and no-infection group. Only for current smoking, a significant difference between the infection and no-infection group (28 versus 12%; P = 0.030) was found. In participants with ADL disability, more participants in the infection group were living in long-term care facilities than in the no-infection group (48 versus 27%, P = 0.001). In this group of participants with ADL disability, participants with an infection between 85 and 86 years had a significantly higher median ADL baseline score compared with those without infections (16 versus 13 points; P < 0.001). In both strata, there was a higher occurrence of COPD in participants with infections (participants without ADL disability: infection 28% versus no-infection 6%; P = 0.001), and in participants with ADL disability: infection 17 versus 7%; P = 0.009. In the participants with ADL disability, there was significantly more incontinence among those participants with infection (68 versus 51%; P = 0.013).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population at the age of 86 years (n = 473), stratified for ADL disability at the age of 86 years for the infection or no-infection groups between the ages of 85–86 years

| No ADL disability at 86 years (GARS = 9)b |

ADL disability at 86 years (GARS >9)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectiona (n = 32) |

No infectiona (n = 162) |

Infectiona (n = 75) |

No infectiona (n = 204) |

|||

| n (%) | n (%) | P-value | n (%) | n (%) | P-value | |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||||

| Female | 22 (68.8) | 108 (66.7) | 0.819* | 56 (74.7) | 133 (65.2) | 0.134* |

| Long-term care facility | 3 (9.4) | 11 (6.8) | 0.706** | 36 (48.0) | 55 (27.0) | 0.001* |

| Primary school only | 20 (62.5) | 91 (56.2) | 0.509* | 53 (71.6) | 128 (63.1) | 0.185* |

| Low income | 17 (53.1) | 72 (44.4) | 0.384* | 44 (60.3) | 102 (51.0) | 0.174* |

| Smoking (current) | 9 (28.1) | 20 (12.3) | 0.030** | 10 (13.5) | 31 (15.3) | 0.849** |

| Functioning | ||||||

| GARS score, median (IQR)b | 9 (9;9) | 9 (9;9) | 1.000*** | 16 (12;30) | 13 (11;18) | <0.001*** |

| Severe cognitive impairment (MMSE<19) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (1.9) | 0.191** | 25 (35.2) | 49 (24.1) | 0.070* |

| Depressive symptoms (GDS-15 >4)c | 2 (6.7) | 14 (8.8) | 1.000** | 8 (17.4) | 32 (20.9) | 0.601* |

| Infections between 85 and 86 years of age | ||||||

| At least one infection (UTI or LRTI) | 32 (100.0) | NA (NA) | NA | 75 (100.0) | NA (NA) | NA |

| UTI | 17 (53.1) | NA (NA) | NA | 55 (73.3) | NA (NA) | NA |

| LRTI | 15 (48.4) | NA (NA) | NA | 30 (40.0) | NA (NA) | NA |

| Co-morbidities | ||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (10.0) | 12 (7.5) | 0.710** | 4 (5.5) | 26 (12.9) | 0.123** |

| Stroke | 3 (9.7) | 8 (5.0) | 0.391** | 18 (24.0) | 29 (14.3) | 0.055* |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 4 (12.9) | 17 (10.5) | 0.752** | 9 (12.2) | 30 (14.9) | 0.697** |

| COPDd | 9 (28.1) | 9 (5.6) | 0.001** | 13 (17.3) | 14 (6.9) | 0.009* |

| Musculoskeletal complaints | 14 (43.8) | 52 (32.3) | 0.212* | 38 (53.5) | 103 (52.9) | 0.919* |

| Incontinence | 11 (36.7) | 49 (31.0) | 0.542* | 49 (68.1) | 99 (51.0) | 0.013* |

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; GDS-15, Geriatric Depression Scale with 15 items; ADL, activities of daily living; GARS, Groningen Activity Restriction Scale SD, standard deviation; UTI, urinary tract infection; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NA, not applicable.

aInfection, urinary tract infection or lower respiratory tract infection.

bADL disability measured with the 9-item Groningen Activity Restriction Scale (9–36).

cOnly administered to participants with MMSE >19.

dChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) registered at the age of 85 years.

*Chi-square test.

**Fisher's exact test.

***Mann–Whitney U test.

Short-term consequences: retrospective analysis

Table 2 presents the 1-year increase in ADL disability score from age 85 to 86 years for participants with and without ADL disability at age 86 years. In participants without ADL disability, 32 (16.5%) had at least one infection versus 75 (26.9%) in participants with ADL disability (P = 0.008).

Table 2.

Short-term change in the ADL score (delta between the ages of 85–86 years) depending on the presence of infections between 85 and 86 years

| No ADL disability at 86 years, n = 194 (GARS = 9)a |

ADL disability at 86 years, n = 279 (GARS>9)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Mean ADL-increase (SD) 85–86 | P-valueb | n (%) | Mean ADL increase (SD) 85–86 | P-valueb | |

| No-infection | 162 (83.5) | −0.42 (1.10) | 204 (73.1) | 2.52 (8.18) | ||

| At least one infection (UTI or LRTI) | 32 (16.5) | −0.53 (0.98) | 0.594 | 75 (26.9) | 2.28 (5.02) | 0.809 |

| UTI | 17 (8.8) | −0.53 (1.07) | 0.740 | 55 (19.7) | 2.53 (5.17) | 0.962 |

| LRTI | 15 (7.7) | −0.53 (0.92) | 0.715 | 30 (10.8) | 1.83 (4.62) | 0.627 |

UTI, urinary tract infection; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; SD, standard deviation; ADL, activities of daily living; GARS, Groningen Activity Restriction Scale.

aADL disability measured with the 9-item Groningen Activity Restriction Scale (9–36).

bIndependent t-test; no-infection group compared with infection groups.

In participants with ADL disability at age 86 years, the mean increase in ADL scores was similar in participants with an infection (UTI or LRTI) and without an infection (2.28 versus 2.52 points increase; independent t-test, P = 0.809). In participants without ADL disability at the age of 86 years, the mean increase in ADL scores was also similar for participants with and without infection (independent t-test, P = 0.594).

Long-term consequences: prospective analysis

In participants without ADL disability at baseline (n = 194), an infection (UTI or LRTI) between the ages of 85–86 years was associated with higher risk to develop ADL disability from age 86 onwards [HR: 1.63 (95% CI: 1.04–2.55)]. After adjustment for gender, living situation and comorbidity this risk remained roughly similar [HR: 1.70 (95% CI: 1.03–2.81)].

For UTI and LRTI, the unadjusted HRs were 1.66 (95% CI: 0.95–2.90) and 1.43 (95% CI: 0.75–2.73), respectively. After adjustment these, HRs remained similar (data not shown).

The changes in ADL disability scores over time for those with and without infection, with and without UTI, and with and without LRTI, are presented in Figure 1, stratified for ADL disability at the age of 86 years. In all groups, ADL disability increased with age.

Figure 1.

Change in the ADL score over time for those with and without an infection between the ages of 85–86 years (A), with and without UTI (B) and with and without LRTI (C), stratified for ADL disability at age 86 years. Linear mixed models in which β3 is the additional annual change in ADL disability score for those with infection between ages 85–86 years.

In participants with ADL disability at baseline, the difference in the ADL score between the infection and no-infection group at baseline was 4.52 points (P < 0.001). No accelerated increase was found in this group for those with an infection compared with those without: additional annual change −0.32 points, (95% CI: −0.85–0.21, P = 0.230) (Figure 1).

Among the participants without ADL disability at baseline, participants with an infection (UTI or LRTI) between age 85 and 86 years had an accelerated increase in ADL disability (1.07 points extra per year, 95% CI: 0.61–1.53, P < 0.001) compared with those without infections (Figure 1). The accelerated increase in ADL disability was 1.25 points extra per year (95% CI: 0.66–1.83, P < 0.001) for UTI and 0.70 points extra per year (95% CI: 0.03–1.38, P = 0.041) for LRTI. After adjustment for gender, living situation (independent or long-term care facility) and comorbidity, these estimates remained similar, still significant and the conclusions were unchanged (data not shown).

Discussion

The present study shows that, in the general population of the oldest-old, clinically diagnosed infections are predictive for the development of ADL disability for persons without ADL disability at the age of 86 years. Moreover, clinically diagnosed infections contribute to an accelerated increase in ADL disability on the long term. No such association was found for those with ADL disability at baseline.

Our results build on evidence from studies involving patients in selected populations of nursing home residents [15–17]. Bula et al. [15] showed a higher risk of a decline in the functional status in older nursing home residents with an infection (mean age 85.7 years, 76.6% female). Barker et al. [16] found a decrease in functioning in older persons living in long-term care facilities within 3–4 months after an influenza infection. However, in contrast to the previous studies, Loeb et al. [17] found no significant effect in a follow-up period of 3 years on the functional status in nursing home residents, neither for pneumonia nor LRTIs compared with controls (mean age 86.1 years, 75.5% female). Our study is the first to focus on the consequences of infections on ADL disability in the oldest-old in the general population.

Interestingly, in a previous analysis in the Leiden 85-plus Study, we found that chronic multimorbidity predicts an accelerated increase in ADL disability in very old persons with a good cognitive function [24]. This study shows that also an acute illness predicts an accelerated increase in ADL disability in the oldest-old without ADL disability at 86 years.

The present study is based on a unique sample of participants aged ≥86 years. The population-based study structure and almost complete follow-up of the participants allow us to generalise our results to the oldest-old in the general population. All infections were clinically diagnosed by GPs and elderly care physicians. This procedure reflects usual care and enables generalisation of our results to daily clinical care for the oldest-old.

A limitation of our study is that we only have information on infections per year and do not know the precise date the infection occurred.

Conclusion

This study shows that in older persons without ADL disability at 86 years of age, clinical infections (UTI and LRTI) predict the development of ADL disability from age 86 onwards. These infections may be used in the future as a predictor for ADL disability in the oldest-old who are not yet disabled. The GP or elderly care physician should be vigilant when older persons without ADL disability get infections and may start active functional rehabilitation to maintain independence in ADL. Future studies may also address whether the prevention of infections, a quick recovery after infections and functional rehabilitation are beneficial in the oldest-old in the general population to maintain independence in ADL and to avoid adverse health outcomes.

Key points.

Ageing is frequently accompanied by a higher incidence of infections and an increase in disability in activities of daily living.

In 86-year-old persons without ADL disability, an infection was associated with a higher risk to develop ADL disability.

In disabled 86-year-old persons, there were no differences in ADL increase between participants with and without an infection.

Among the oldest-old in the general population, infections are predictive for the development of ADL disability.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

The Leiden 85-plus Study was partly funded by an unrestricted grant from the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports. A grant was received from the Dutch Organisation of Scientific Research (NWO) for Open Access publication of this manuscript.

References

- 1.High K, Bradley S, Loeb M, Palmer R, Quagliarello V, Yoshikawa T. A new paradigm for clinical investigation of infectious syndromes in older adults: assessing functional status as a risk factor and outcome measure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:528–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marrie TJ. Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1066–78. doi: 10.1086/318124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infections in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:423–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavazzi G, Krause KH. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:659–66. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nationaal Kompas. Infecties van de onderste luchtwegen. Omvang van het probleem. Incidentie en sterfte naar leeftijd en geslacht. [Lower respiratory tract infections. Extent of the problem. Incidence and mortality by age and gender] (online) Available at: http://www.nationaalkompas.nl/gezondheid-en-ziekte/ziekten-en-aandoeningen/ademhalingswegen/infecties-van-de-onderste-luchtwegen/ (April 2012, date last accessed)

- 6.Nationaal Kompas. Acute urineweginfecties.Omvang van het probleem. Incidentie en sterfte naar leeftijd en geslacht. [Acute urinary tract infections. Extent of the problem. Incidence and mortality by age and gender] (online). Available at: http://www.nationaalkompas.nl/gezondheid-en-ziekte/ziekten-en-aandoeningen/urinewegen-en-de-geslachtsorganen/acute-urineweginfecties/ (April 2012, date last accessed)

- 7.Engelhart ST, Hanses-Derendorf L, Exner M, Kramer MH. Prospective surveillance for healthcare-associated infections in German nursing home residents. J Hosp Infect. 2005;60:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mylotte JM. Nursing home-acquired bloodstream infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:833–7. doi: 10.1086/502502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tal S, Guller V, Levi S, et al. Profile and prognosis of febrile elderly patients with bacteremic urinary tract infection. J Infect. 2005;50:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sliedrecht A, den Elzen WP, Verheij TJ, Westendorp RG, Gussekloo J. Incidence and predictive factors of lower respiratory tract infections among the very elderly in the general population. The Leiden 85-plus Study. Thorax. 2008;63:817–22. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.093013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Binder EF, Kruse RL, Sherman AK, et al. Predictors of short-term functional decline in survivors of nursing home-acquired lower respiratory tract infection. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:60–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan V, Angus DC, Griffin MF, Clermont G, Scott WR, Linde-Zwirble WT. Hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: age- and sex-related patterns of care and outcome in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:766–72. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2103038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoogerduijn JG, Schuurmans MJ, Duijnstee MS, de Rooij SE, Grypdonck MF. A systematic review of predictors and screening instruments to identify older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:46–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA, Camacho T, Cohen RD. The dynamics of disability and functional change in an elderly cohort: results from the Alameda County Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:799–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bula CJ, Ghilardi G, Wietlisbach V, Petignat C, Francioli P. Infections and functional impairment in nursing home residents: a reciprocal relationship. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:700–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker WH, Borisute H, Cox C. A study of the impact of influenza on the functional status of frail older people. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:645–50. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loeb M, McGeer A, McArthur M, Walter S, Simor AE. Risk factors for pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections in elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2058–64. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.17.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caljouw MA, den Elzen WP, Cools HJ, Gussekloo J. Predictive factors of urinary tract infections among the oldest old in the general population. A population-based prospective follow-up study. BMC Med. 2011;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kempen GI, Miedema I, Ormel J, Molenaar W. The assessment of disability with the Groningen Activity Restriction Scale. Conceptual framework and psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:1601–10. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Craen AJ, Heeren TJ, Gussekloo J. Accuracy of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) in a community sample of the oldest old. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:63–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown LM, Schinka JA. Development and initial validation of a 15-item informant version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:911–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Recent Evidence and Development of a Shorter Version. In Clinical Gerontology : A Guide to Assessment and Intervention. New York: The Haworth Press 1986; pp. 165–73. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drewes YM, den Elzen WP, Mooijaart SP, de Craen AJ, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J. The effect of cognitive impairment on the predictive value of multimorbidity for the increase in disability in the oldest old: the Leiden 85-plus Study. Age Ageing. 2011;40:352–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]