Abstract

Background: the number and proportion of adults diagnosed with HIV infection aged 50 years and older has risen. This study compares the effect of CD4 counts and anti-retroviral therapy (ART) on mortality rates among adults diagnosed aged ≥50 with those diagnosed at a younger age.

Methods: retrospective cohort analysis of national surveillance reports of HIV-diagnosed adults (15 years and older) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The relative impacts of age, CD4 count at diagnosis and ART on mortality were determined in Cox proportional hazards models.

Results: among 63,805 adults diagnosed with HIV between 2000 and 2009, 9% (5,683) were aged ≥50 years; older persons were more likely to be white, heterosexual and present with a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (48 versus 32% P < 0.01) and AIDS at diagnosis (19 versus 9%, P < 0.01). One-year mortality was higher in older adults (10 versus 3%, P < 0.01) and especially in those diagnosed with a CD4 <200 cells/mm3 left untreated (46 versus 15%, P < 0.01). While the relative mortality risk reduction from ART initiation at CD <200 cells/mm3 was similar in both age groups, the absolute risk difference was higher among older adults (40 versus 12% fewer deaths) such that the number needed to treat older adults to prevent one death was two compared with eight among younger adults.

Conclusions: the magnitude of benefit from ART is greater in older adults than younger adults. Older persons should be considered as a target for HIV testing. Coupled with prompt treatment, earlier diagnosis is likely to reduce substantially deaths in this group.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, antiretroviral therapy, epidemiology, surveillance, older people

Introduction

Since 2000, the HIV epidemic in the UK has been characterised by a re-emergence of infections among men who have sex with men (MSM), in common with other European countries, North America and Australia [1]. This has coincided with an increase in heterosexual transmissions, the majority of which were acquired in sub-Saharan Africa [2]. Surveillance data also show a clear increase in new diagnoses among persons aged ≥50 years [3]. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the number of older adults diagnosed with HIV increased from 299 in 2000 (8%) to 807 in 2009 (13%) [4]. Furthermore, older adults are more likely to present with advanced disease, with 48% diagnosed with a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 at diagnosis [5]. Similar increases in HIV diagnoses among older adults have been reported in the USA [6].

The increasing trend in new diagnoses of HIV among older adults suggests an under-recognised public health problem. There is evidence that older adults presenting later are associated with poor outcomes [2, 3]. Consequently, aggressive antiretroviral therapy (ART) may often be required at diagnosis [7]. While older age in itself should not influence ART initiation, ART use is made more challenging by the increased prevalence of co-morbidities in this age group [8, 9]. From a public health perspective, late diagnoses among older adults suggest a longer period of untreated HIV. This has implications for continued transmission while infection remains undiagnosed. It is also possible that lower CD4 in older adults at diagnosis reflects more rapid disease progression [10, 11].

Using data from a large national cohort of HIV diagnosed individuals, this study set out to determine ART coverage and mortality rates among older HIV positive adults, and make comparisons with younger HIV diagnosed adults. We hypothesised that mortality might be different in older adults due to differences in CD4 count at presentation, ART initiation, response to ART or a combination of these factors.

Methods

Design

A retrospective cohort analysis of new HIV diagnoses reported to the Health Protection Agency (HPA) between 2000 and 2009 was conducted. National surveillance data from England, Wales and Northern Ireland receive information from multiple sources reflecting the full range of care provision: (i) clinician reports of new HIV diagnoses, first AIDS diagnosis, and deaths among HIV-diagnosed adults; (ii) laboratory reports of CD4 surveillance [12]; (iii) a national cohort of all outpatient care providers with annual follow-up [13]. Reports of death from any cause are also cross-referenced by mortality information from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Data were linked across systems using soundex codes, sex and date of birth with records linked in 92%. Full details of the methodology for these surveillance systems are published on the HPA website [14].

Participants

All HIV seropositive adults aged 15 years and over, diagnosed in England, Wales and Northern Ireland between 2000 and 2009, were included. Exposure route, ethnicity and development of AIDS were determined by clinician report at diagnosis. Information on CD4 count at diagnosis was available from laboratory reports [12] and new diagnosis reports. Persons were considered as having used ART if information on nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors or protease inhibiters were reported in survey data from outpatient care providers at any time. Prescribing information among patients accessing outpatient care is near-complete. In 2011, 0.38% (283 of 73,659) records had missing data [15]. CD4 count within 91 days of diagnosis defined ‘late’ diagnoses (CD4 <350 cells/mm3) and ‘very late’ diagnoses (CD4 <200 cells/mm3) [16]. Though current guidelines recommend initiating therapy at CD4 <350 cells/mm3, we considered ‘very late’ diagnoses and ‘late’ diagnoses separately because CD4 <200 cells/mm3 was regarded as the treatment threshold during the earlier part of the time period 2000–09.

Outcome measures

Mortality was obtained from clinician reports, supplemented by ONS reports. Short-term mortality was defined as death from any cause within 1 year of HIV diagnosis. These reports were followed up until December 2010.

Data analysis

All data were analysed in STATA version 11.1. (Stata Corp, TX, USA). The effect of age on all-cause mortality within 1 year from diagnosis was examined stratified in 10-year age groups. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were used, assessing the effects of sex, ethnicity and exposure route. Individuals not identifying as black or white were classified as ‘other’. Persons reporting intravenous drug use (IDU) as possible route of infection were considered together, even if they also reported other possible exposures (e.g. MSM).

Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Post-model testing included the examination of Schoenfeld residuals and log–log survival plots. The assumption of proportionality did not hold for the population as a whole, though were met after stratification by sex and exposure. Accordingly, three models estimating the effect of age and ethnicity are presented: MSM; heterosexual men; heterosexual women. Exposure through IDU was not considered further due to the relatively small number of older individuals in this group (n = 65).

The effect of ART use on 1-year mortality was assessed in a series of proportional hazards models, where adults aged 15–49 (‘young’) and age ≥50 years (‘older’) were compared. ART initiation in late diagnoses and very late diagnoses were modelled separately. Differences in Kaplan–Meier plots were determined by the log-rank test. The χ2 test was applied to test differences in proportions and the Mann–Whitney U test to assess differences in variables with a non-Gaussian distribution. For mortality, we calculated the relative risk reduction, risk difference and number needed to treat (NNT), which was calculated as the inverse of the risk difference associated with ART use [17].

The effect of missing data was investigated by separately examining mortality and clinical AIDS at diagnosis for persons with an unknown CD4 count at diagnosis and for those not subsequently entering outpatient care.

Results

Between 2000 and 2009, 63,805 adults were newly diagnosed with HIV, of which 5,683 diagnoses were in adults ≥50 years (9%). Of these diagnoses in older persons, 217 were aged ≥70 (4%) and the oldest diagnosed was aged 84. Table 1 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics of these two age groups. Compared with younger adults, older men were more likely to be white (58 versus 39%, P < 0.01) and heterosexual (31 versus 21%, P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of new HIV diagnoses 2000–2009 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland by age group

| Age 15–49 (n = 58,122) | Age 50 and over (n = 5,683) | P-value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age men (IQR) | 34 (29–40) | 55 (52–60) | |

| Median age women (IQR) | 31 (27–37) | 55 (52–60) | |

| Sex (% men) | 34,437 (59) | 4,189 (74) | <0.01 |

| Exposure route (%) | |||

| MSM | 19,984 (34) | 2,069 (36) | <0.01 |

| Heterosexual men | 12,150 (21) | 1,763 (31) | <0.01 |

| Heterosexual women | 22,540 (39) | 1,359 (24) | <0.01 |

| IDU | 1,406 (2) | 65 (1) | <0.01 |

| Other | 2,042 (4) | 427 (8) | |

| Ethnic group (%) | |||

| White | 22,860 (39) | 3,305 (58) | <0.01 |

| Black | 30,491 (52) | 1,948 (34) | <0.01 |

| Other | 4,771 (8) | 430 (8) | |

| One-year mortality (%) | 1,515 (3) | 557 (10) | <0.01 |

| AIDS at diagnosis (%)a | 5,218 (9) | 1,059 (19) | <0.01 |

| CD4 at diagnosis performed (%)a | 43,840 (75) | 4,304 (76) | 0.61 |

IQR, inter-quartile range.

aWithin 91 days.

**P-values calculated using χ2 tests.

Data on CD4 count at diagnosis were available for 48,144 (75%) of all participants (Table 1). Demographic information was similar for those with and without a CD4 count. Older persons had lower median CD4 counts (210 cells/mm3 versus 310 cells/mm3, P < 0.01) and more likely to have an AIDS-defining condition at first diagnosis (19 versus 9%, P < 0.01), regardless of CD4 count. One-year mortality was reported among 2,072 newly HIV diagnosed adults; 1,515 in younger adults (3%) and 557 in older adults (10%) (P < 0.01).

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression for mortality within 1 year, adjusted for age and ethnicity stratified by sex and exposure route. The effect of age in different 10-year strata increased and this was most evident in the MSM model. Compared with adults aged 15–29, adults aged ≥60 had a higher mortality (HR: 28; 95% CI: 18–45) in MSM, where the difference was less pronounced among heterosexually-acquired infections (HR: 7.2; 95% CI: 4.6–11, men; HR: 11; 95% CI: 7.5–17, women). Ethnicity did not appear to be a significant determinant of mortality, and no assessment of the interaction between age and ethnicity was made.

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox regression model of proportional hazards for early mortality (1 year) in all new HIV diagnoses between 2000 and 2007, stratified by sex

| MSM |

Heterosexual men |

Heterosexual women |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | n | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 15–29 | 5,439 | 1 | 2,371 | 1 | 8,477 | 1 |

| 30–39 | 8,015 | 2.3 (1.5–3.6) | 5,751 | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) | 9,489 | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) |

| 40–49 | 4,509 | 6.7 (4.3–10) | 3,318 | 2.5 (1.7–3.7) | 3,410 | 4.5 (3.4–5.9) |

| 50–59 | 1,465 | 13 (8.1–20) | 1,161 | 5.0 (3.3–7.4) | 972 | 4.2 (2.8–6.2) |

| 60–69 | 512 | 28 (18–45) | 484 | 7.2 (4.6–11) | 312 | 11 (7.5–17) |

| Ethnicitya | ||||||

| White | 18,581 | 1 | 2,831 | 1 | 2,620 | 1 |

| Black | 1,359 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 10,254 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 20,040 | 0.8 (0.1–1.0) |

MSM, men who have sex with men.

aOther ethnicities not considered as a category in these models due to heterogeneity within this group.

The figure in Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online shows Kaplan–Meier plots for 1-year mortality stratified by CD4 count at diagnosis (CD4 >500; CD4 350–499; CD4 200–349; CD4 <200 cells/mm3), where older and younger age groups were compared. Though lower CD4 counts showed higher mortality, the largest difference is in the CD4 <200 cells/mm3 stratum (P < 0.01), and this was even greater in the older age group (13% mortality within 1 year).

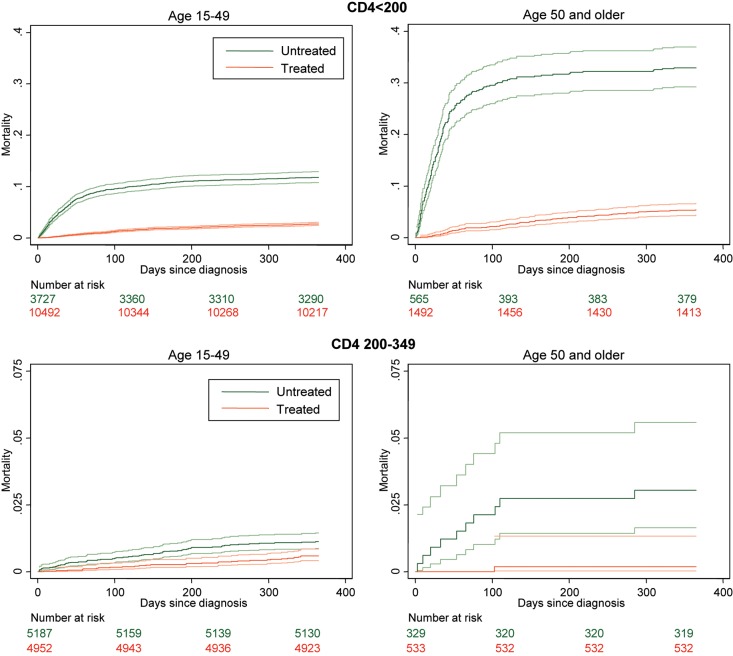

The table in Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online shows the effect of ART on survival. Among very late presenters (CD4 <200 cells/mm3), there was no difference in ART use in older or younger adults (73 and 74%, respectively, P = 0.24). Mortality within 1 year of diagnosis in untreated persons was high in both age groups, but much more so in older adults (Figure 1). Thus, 447 untreated younger adults (15%) and 186 untreated older adults (46%) died within 1 year. The relative risk reduction from ART initiation at CD <200 cells/mm3 was similar in both age groups [younger RR 0.18 (95% CI: 0.15–0.21); older RR 0.12 (95% CI: 0.09–0.15)]. However, the absolute risk difference was higher among older adults (12% fewer deaths on treatment in younger versus 40% fewer deaths in older adults on treatment). This larger absolute magnitude of the effect of ART in older adults equates to a lower number NNT (younger NNT = 8 versus older NNT = 2).

Figure 1.

Short-term mortality according to CD4 count at diagnosis and ART use. Each mortality curve is presented with upper and lower 95% confidence intervals. Upper panel shows mortality outcomes in the first year from diagnosis when CD4 <200, according to ART use. Lower panels show the same for CD4 200–349. Note the range on the y-axis is different (CD4 <200 from 0 to 0.4; CD4 200–349 from 0 to 0.15).

When a treatment threshold of CD4 <350 cells/mm3 was considered, proportionally more older adults received ART (62 compared with 49% younger adults) (Figure 1). The effect of ART in older adults also appeared to be greater compared with younger adults treated at this CD4 level, though in neither group was the magnitude of benefit comparable with the effects at CD4 <200 cells/mm3.

One-year mortality and prevalence of AIDS defining conditions at diagnosis could be ascertained for the whole cohort. These variables were used to assess differences in persons without a CD4 at diagnosis (25%) or not entering outpatient care (9%) (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online Table 2). Compared with the whole cohort, no CD4 at diagnosis or not entering outpatient care was associated with higher mortality. Those not entering outpatient care appeared to have a higher prevalence of AIDS at diagnosis. Conversely, individuals subsequently receiving outpatient care had lower mortality than the cohort as a whole.

Discussion

Between 2000 and 2009, adults aged 50 years or older accounted for 9% of new diagnoses, and nearly half presented at a very late stage of HIV infection (CD4 <200 cells/mm3). Compared with younger adults, 1-year mortality was consistently higher in the older age group, but these differences were significantly larger in individuals presenting very late. Given the higher mortality, the benefit from ART use in older persons was much greater compared with younger adults (NNT in older 2 versus NNT in younger 8). Taken together, these results suggest that late diagnosis is an important determinant of mortality in older adults. Once HIV care is accessed, gains from treatment are largest in this group. The proportion of late presentations, coupled with the association of ART use with the highest reductions in mortality among older adults strengthens the case for specifically targeting older adults as a prevention group.

Surveillance and cohort data have limitations. However, surveillance methods available to HPA are well established, and trends in all regions demonstrate little variation in the short term. This stability in reporting suggests that case-ascertainment is near-complete. Surveillance data may be skewed by under-reporting of early deaths. To address potential reporting delays, we included death reports to end of 2010 (among persons diagnosed to end of 2009). An additional problem is the proportion of undiagnosed HIV, though this study helps to highlight the likelihood of significant under-recognition in older persons. We were unable to make an assessment of the influence of viral load on treatment outcomes nor were we able to assess the effectiveness of individual ART regimes in older persons, especially in regard to co-morbidities. Further investigation at the clinic level would be important.

It is clear that persons not linked into outpatient care, although small in number, represent a group with more advanced disease, with higher mortality and AIDS-defining conditions at diagnosis. These may include: patients lost to follow-up for HIV care; individuals who could not be linked across surveillance systems; those who present extremely late and unwell and potentially die on first admission with HIV. Information on acute ART in persons with advanced infection, for example, hospitalised patients, might not be captured as effectively. If those apparently not receiving ART were in fact treated, this would over-estimate the benefit of ART in the untreated groups. In any case, clinical reasons (e.g. lack of provision or patient refusal) for why ART might not have been initiated in this population were not available. Though this is an important subgroup, it is unlikely that further information on their treatment with ART would substantially alter the overall conclusions from the hazards model.

The principal strength of this study is its near comprehensive coverage of persons diagnosed with HIV and accessing HIV care in the ART era. Of all diagnosed cases, at least 92% entered into outpatient care in our study. Reports to HPA have been consistent across regions and over time. The National Health Service provides virtually all HIV/AIDS-related care, so linkage of new diagnoses for clinical follow-up is a major advantage. Similarly, mortality reports to ONS are a reliable notification of outcomes. Previous studies show very high rates of access to care and low rates of loss to follow-up [18]. This does not appear to be different for older adults. Indeed, older adults had comparable proportions of CD4 performed at diagnosis and within similar time frames.

The high mortality in relation to late diagnoses observed in this national cohort is in keeping with other surveillance data [19, 20]. It appears that when older adults eventually present, more have an AIDS-defining illness at diagnosis, and it may be this clinical picture that triggers the initial HIV test. Though older persons may be more likely to adhere to ART [21], older individuals have a slower CD4 response to ART [22, 23]. However, we demonstrate here for the first time that the magnitude of benefit from ART is actually highest in older patients presenting very late.

The high number of late diagnoses in itself indicates a significant proportion of undiagnosed HIV in older adults. Consequently, older adults are more often diagnosed on their first HIV test [24]. Older adults are more likely to be white and heterosexual men compared with young people diagnosed with HIV and this identifies a new demographic for HIV infection in UK [3].

UK clinical guidelines have recommended starting therapy at 350 cells/mm3 since 2008 with and a threshold of 500 cells/mm3 currently under consideration [25] in line with US guidelines [26]. We note that data used in this study (2000–09) show a larger proportion of older persons received ART in the CD4 250–349 cells/mm3 range. This may suggest that there was a greater degree of clinical concern in older compared with younger persons. Nonetheless, the magnitude of this response to ART was still higher in older adults, though the effects are less pronounced than for very late diagnoses. Because initiating treatment at this threshold may indicate a selected group that are clinically more unwell, the benefit of ART is likely to underestimate the absolute risk reduction were ARTs given to the whole group at this CD4 threshold. Too few persons were treated when CD4 was >350 cells/mm3 at diagnosis to assess the effect of ART in this population.

HIV/AIDS is a treatable condition. Our findings showing a high uptake rate of ART after diagnosis and a high efficacy of ART in older adults are encouraging. Nevertheless older adults experience especially high rates of mortality within 1 year of diagnosis, largely driven by late diagnosis. There are broad public health implications for older adults at risk of HIV. Wider testing in this population, coupled with prompt treatment might substantially reduce deaths among HIV-infected persons. Developing a testing programme would be an important consideration, and in some circumstances might be regarded as cost-effective [27]. Earlier diagnosis could perhaps be achieved if clinicians treating older adults contemplated testing more widely, perhaps in the context of recurrent unexplained infections or being mindful of sexual risk in older adults. Certainly, no routine upper age limit should be regarded as appropriate to offer HIV testing.

Key points.

Older adults being diagnosed with HIV are being recognised very late.

Accordingly, mortality is very high.

As a result, the magnitude of benefit from ART is just as great.

Earlier detection and prompt treatment is likely to mitigate some of the mortality from HIV in this age group.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Funding

D.D. receives funding from the Wellcome Trust as a Research Training Fellow. The HPA receives statutory funding from the UK Department of Health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank other members of the HIV/AIDS reporting section at the Health Protection Agency who helped with the preparation of the data set. The authors are particularly grateful for the invaluable advice on statistical analysis from Tom Nichols.

References

- 1.Sullivan PS, Hamouda O, Delpech V, et al. Reemergence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in North America, Western Europe, and Australia, 1996–2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.004. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chadborn TR, Delpech VC, Sabin CA, Sinka K, Evans BG. The late diagnosis and consequent short-term mortality of HIV-infected heterosexuals (England and Wales, 2000–2004) AIDS. 2006;20:2371–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801138f7. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801138f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RD, Delpech VC, Brown AE, Rice BD. HIV transmission and high rates of late diagnoses among adults aged 50 years and over. AIDS. 2010;24:2109–15. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833c7b9c. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833c7b9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health Protection Agency. HIV in the United Kingdom: 2010 Report. Health Protection Report 2010; 4

- 5.Borghi V, Girardi E, Bellelli S, et al. Late presenters in an HIV surveillance system in Italy during the period 1992–2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:282–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318186eabc. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e318186eabc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Althoff KN, Gange SJ, Klein MB, et al. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1512–20. doi: 10.1086/652650. doi:10.1086/652650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chadborn TR, Baster K, Delpech VC, et al. No time to wait: how many HIV-infected homosexual men are diagnosed late and consequently die? (England and Wales, 1993–2002) AIDS. 2005;19:513–20. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162340.43310.08. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000162340.43310.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pratt G, Gascoyne K, Cunningham K, Tunbridge A. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in older people. Age Ageing (Review) 2010;39:289–94. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq009. doi:10.1093/ageing/afq009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kearney F, Moore AR, Donegan CF, Lambert J. The ageing of HIV: implications for geriatric medicine. Age Ageing (Review) 2010;39:536–41. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq083. doi:10.1093/ageing/afq083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lodi S, Phillips A, Touloumi G, et al. Time from human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion to reaching CD4+ cell count thresholds <200, <350, and <500 cells/mm3: assessment of need following changes in treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:817–25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir494. doi:10.1093/cid/cir494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolbers M, Babiker A, Sabin C, et al. Pretreatment CD4 cell slope and progression to AIDS or death in HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy—the CASCADE collaboration: a collaboration of 23 cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000239. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engmann J, Chadborn T, Delpech V. Health Protection Agency; 2008. CD4 surveillance scheme: monitoring immune suppression in HIV-infected adults. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice BD, Payne LJ, Sinka K, Patel B, Evans BG, Delpech V. The changing epidemiology of prevalent diagnosed HIV infections in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1997 to 2003. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:223–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012070. doi:10.1136/sti.2004.012070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health Protection Agency. HIV. http://www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/HIV/ 13 June 2011, date last accessed.

- 15.Health Protection Agency. Numbers accessing HIV care: National Overview. http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1203064766492. (1 May 2013, date last accessed)

- 16.Antinori A, Coenen T, Costagiola D, et al. Late presentation of HIV infection: a consensus definition. HIV Med. 2011;12:61–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00857.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laupacis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS. An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. The N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1728–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806303182605. doi:10.1056/NEJM198806303182605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice BD, Delpech VC, Chadborn TR, Elford J. Loss to follow-up among adults attending human immunodeficiency virus services in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:685–90. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318214b92e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petoumenos K, Law MG. Risk factors and causes of death in the Australian HIV Observational Database. Sexual health. 2006;3:103–12. doi: 10.1071/sh05045. doi:10.1071/SH05045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linley L, Hall HI, An Q, Wheeler W. HIV/AIDS diagnoses among persons fifty years and older in 33 states. 2001–2005. National HIV Prevention Conference.2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Horberg MA, DeLorenze GN, Klein D, Quesenberry CP., Jr Older age and the response to and tolerability of antiretroviral therapy. Archiv Intern Med. 2007;167:684–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.7.684. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.7.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Althoff KN, Justice AC, Gange SJ, et al. Virologic and immunologic response to HAART, by age and regimen class. AIDS. 2010;24:2469–79. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e6d14. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833e6d14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenbaum AH, Wilson LE, Keruly JC, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Effect of age and HAART regimen on clinical response in an urban cohort of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2008;22:2331–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831883f9. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831883f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayaraman GC, Bush KR, Lee B, Singh AE, Preiksaitis JK. Magnitude and determinants of first-time and repeat testing among individuals with newly diagnosed HIV infection between 2000 and 2001 in Alberta, Canada: results from population-based laboratory surveillance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1651–6. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200412150-00020. doi:10.1097/00126334-200412150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gazzard BG, Anderson J, Babiker A, et al. British HIV association guidelines for the treatment of hiv-1-infected adults with antiretroviral therapy 2008. HIV Med (Practice Guideline) 2008;9:563–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00636.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department of Health and Human Services. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-infected Adults and Adolescents. 10 January 2011; 1–166 http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. 21 September 2011.

- 27.Sanders GD, Bayoumi AM, Holodniy M, Owens DK. Cost-effectiveness of HIV screening in patients older than 55 years of age. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:889–903. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00002. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.