Abstract

Purpose

Limited research exists on the social information needs of adolescents and young adults (AYAs, aged 15–39 at diagnosis) with cancer.

Methods

The Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experiences (AYA HOPE) Study recruited 523 patients to complete surveys 6–14 months after cancer diagnosis. Participants reported information needs for talking about their cancer experience with family and friends (TAC) and meeting peer survivors (MPS). Multiple logistic regression was used to examine factors associated with each need.

Results

Approximately 25% (118/477) and 43% (199/462) of participants reported a TAC or MPS need respectively. Participants in their 20s (vs. teenagers) were more likely to report a MPS need (p=0.03). Hispanics (vs. non-Hispanic whites) were more likely to report a TAC need (p=0.01). Individuals who did not receive but reported needing support groups were about 4 and 13 times as likely to report TAC and MPS needs respectively (p<0.05). Participants reporting high symptom burden were more likely to report TAC and MPS needs (p<0.01), and those reporting fair/poor quality of care were more likely to report a TAC need (p<0.01). Those reporting that cancer had an impact on several key relationships with family and friends were more likely to report social information needs.

Conclusion

Social information needs are higher in AYAs diagnosed in their 20s, in Hispanics, among those reporting high symptom burden and/or lower quality of care, and in individuals not in support groups. Efforts should be made to develop interventions for AYAs in most need of social information and support.

Keywords: survivorship, social support, information needs, support group, peer support, communication

Increasing recognition of the unmet needs of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients and survivors has pointed to the importance of providing information to AYAs looking to bolster social support.1 Difficulties in maintaining or making new social relationships are often cited as one of the most important long-term issues for AYA cancer survivors.2–5 Being socially isolated has been shown to affect health outcomes along several pathways, with one study reporting that socially isolated young adults showed increased sensitivity to everyday stressors, a greater propensity for hypertension, and worse physiological functioning.6 Adolescents and young adults with cancer may be at higher risk for social isolation and the negative consequences associated with being apart from normative socio-developmental experiences due to illness and treatment.7 Furthermore, past research has shown that providers and patients do not always agree on who might best provide social support. In one study, cancer survivors valued interacting with other survivors significantly more than support from family and friends, which was a reversed ranking among healthcare providers.8

Several organizations provide peer support for AYA cancer patients and survivors in the form of traditional support groups, groups organized around activities (such as exercise or recreation), and recently created online or social media-based groups. Treadgold and Kuperberg1 reviewed AYA cancer peer support program availability and identified several challenges in both initiating and sustaining them. These include challenges in offering support at different phases of the cancer trajectory, providing services for a diverse age range, and overcoming geographical and financial barriers, a lack of cultural diversity in support group offerings, and a lack of awareness and referrals from healthcare providers.1 For the most widely available type of cancer support program for AYAs—online support groups—participation has been found to be more common among survivors who belong to higher socioeconomic groups9 and may only have transient effects in helping survivors adjust to cancer.10

Social information needs in the context of cancer survivorship represent the information and services that facilitate creating, maintaining, and communicating with a support network. Limited research has been conducted on whether AYAs with cancer desire information and services to meet their social support needs (referred to hereafter as “social information needs”). Understanding which AYAs are most in need is critically important to inform and tailor interventions and support programs targeting AYAs. The current study seeks to identify factors associated with social information needs among AYAs with cancer and whether these needs vary by their perception of the impact of cancer on social relationships.

Methods

The Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) Study is a population-based cohort study that examines the cancer experience of AYAs regarding psychosocial and physical functioning, medical care, and clinical trial involvement.11 The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) with support from the Lance Armstrong Foundation. Patients were identified through seven Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program sites: the states of Iowa and Louisiana; the metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan and Seattle/Puget Sound, Washington; and three metropolitan areas in California: Los Angeles County, San Francisco/Oakland, and Sacramento County. Participants newly diagnosed between July 1, 2007, and October 31, 2008, with histologically confirmed, invasive first primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, germ cell cancer, acute lymphocytic leukemia, or sarcoma (specifically Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma) were considered eligible. Specific cancer sites were chosen due to their higher prevalence in the AYA population.11 Eligibility criteria also included age (15 to 39 at diagnosis), residence in one of the study areas, ability to read and write in English, and being alive at time of contact. Although not an inclusion requirement, approximately 80% of the participants were not on active treatment.12 The survey is available online at: http://outcomes.cancer/gov/surveys/aya. Among 1208 eligible patients, 525 (43% response rate) completed the survey (397 by paper, 115 by internet, and 12 by telephone) at a median of 11 months (range: 4–22 months) from the date of diagnosis. One respondent only consented to release of medical records without completion of the survey, and one survey was lost, leaving 523 surveys available for analysis. In addition, the study included data from medical record reviews and data routinely collected from SEER registries. Approval for the conduct of this study was given by the Institutional Review Boards for each registry and the National Cancer Institute.11

Social information needs

The two social information needs examined were each measured by a single item. On the survey, participants were asked, “At this time, do you feel you need more information about…” followed by a list of needs, including the following social information needs: “how to talk about your cancer experience with family and friends” (labeled talk about cancer or TAC hereafter) and “meeting other adolescents or young adult cancer patients/survivors” (labeled meet peer survivors or MPS hereafter). Response options were: “I have enough information,” “I need some more information,” “I need much more information,” and “Does not apply.” Having an unmet social information need was defined as participants reporting they needed “some” or “much more” information.12 Analyses excluded individuals who responded “Does not apply” (TAC: n=42; MPS: n=58) or left the response blank (TAC: n=4; MPS: n=3).

Factors associated with social information needs

The associations between several variables and unmet social information needs were examined. Sociodemographic variables included age at diagnosis, gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and “other” race/ethnicity [a group that included Asian/Pacific Islanders, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and individuals of mixed or unknown race/ethnicity]), education, and health insurance status at diagnosis. Clinical factors included treatment (radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery), self-rated health variables (current general health and overall quality of care), and number of symptoms experienced in the past 4 weeks: nausea/vomiting, frequent/severe stomach pain, diarrhea/constipation, pain in joints/bones, weight loss, weight gain, frequent/severe fevers, hot flashes, tingling/weakness/clumsiness of the hands/feet, frequent/severe headaches, frequent/severe mouth sores that affect eating/drinking, and problems with memory/attention/concentration. The number of symptoms were summed and categorized into three groups (0–1, 2–3, and ≥4). Additional health-related variables included the number of serious comorbid conditions (0, 1, and ≥2), determined from medical records.13 Whether participants reported both needing and receiving the service of a support group prior to the survey was included in the analysis, given documented potential benefits14 but varying levels of interest support groups,15,16 as well as low availability and access to these services in this population.17

Participants were asked to indicate the overall impact of their cancer on specific areas of their lives on a modified version of the 18-item Life Impact Checklist.18–20 The current analysis examined associations of TAC and MPS with the impact of cancer on relationships with a patient's mother, father, siblings, significant others, friends, children, and dating. Response choices given included “very negative,” “somewhat negative,” “no impact,” “somewhat positive,” “very positive,” and “does not apply.” After preliminary analyses indicated little differences between positive and negative impact reports, responses were categorized as “any impact” (positive or negative) vs. “no impact.” Analyses excluded individuals who responded “does not apply” (numbers ranged from 9 [friends] to 303 [children]) or did not answer (numbers ranged from 3 [father, siblings] to 9 [children, friends]).

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages of those who reported TAC and MPS needs were reported and tested using chi-square tests. Age, gender, cancer site, and race/ethnicity were included in the multiple logistic regression models of TAC and MPS needs, as well as variables that were associated with needs in univariate analyses (p<0.05). Relationships between the impact of cancer and social information needs were examined separately due to the variable sample sizes for each relationship subset, and chi-square tests across the two levels of impact (“any impact” versus “no impact”) were used to evaluate associations. Statistical significance was set to a two-sided α=0.05.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Of the 523 participants, 477 responded to the TAC question and 462 responded to the MPS question. Of those who responded to the specific questions, 118 (25%) and 199 (43%) and of participants reported a TAC or MPS need, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, Frequencies, and Associations with Social Information Needs

| |

Talk about cancer with family and friends (TAC) |

Meet peer survivors (MPS) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

n=477 |

n=462 |

||||

| No information need n (Row %) | Information need n (Row %) | p | No information need n (Row %) | Information need n (Row %) | p | |

| Total | 359 (75.3) | 118 (24.7) | 263 (56.9) | 199 (43.1%) | ||

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| 15–19 | 55 (88.7) | 7 (11.3) | 45 (73.8) | 16 (26.2) | ||

| 20–29 | 154 (74.4) | 53 (25.6) | 111 (54.4) | 93 (45.6) | ||

| 30–39 | 150 (72.1) | 58 (27.9) | 0.03 | 107 (54.3) | 90 (45.7) | 0.02 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 226 (75.3) | 74 (24.7) | 165 (57.3) | 123 (42.7) | ||

| Female | 133 (75.1) | 44 (24.9) | 0.96 | 98 (56.3) | 76 (43.7) | 0.84 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 248 (80.8) | 59 (19.2) | 181 (60.9) | 116 (39.1) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 24 (64.9) | 13 (35.1) | 18 (46.2) | 21 (53.8) | ||

| Hispanic | 52 (63.4) | 30 (36.6) | 38 (48.7) | 40 (51.3) | ||

| Other/unknown | 35 (68.6) | 16 (31.4) | 0.002 | 26 (54.2) | 22 (45.8) | 0.11 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school grad or less | 96 (73.3) | 35 (26.7) | 77 (61.1) | 49 (38.9) | ||

| Some college/associate degree | 125 (72.3) | 48 (27.7) | 88 (52.4) | 80 (47.6) | ||

| College grad or more | 137 (79.7) | 35 (20.3) | 0.24 | 97 (58.1) | 70 (41.9) | 0.30 |

| Missinga | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Health insurance status at diagnosis | ||||||

| Uninsured | 46 (70.8) | 19 (29.2) | 38 (56.7) | 29 (43.3) | ||

| Insured | 307 (76.0) | 97 (24.0) | 0.37 | 221 (57.1) | 166 (42.9) | 0.95 |

| Missinga | 6 | 2 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Clinical/health variables | ||||||

| Cancer site | ||||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 96 (73.3) | 35 (26.7) | 75 (58.6) | 53 (41.4) | ||

| NHL | 84 (71.2) | 34 (28.8) | 57 (48.7) | 60 (51.3) | ||

| Germ cell | 143 (76.9) | 43 (23.1) | 107 (61.5) | 67 (38.5) | ||

| ALL | 18 (94.7) | 1 (5.3) | 11 (57.9) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| Sarcomab | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | 0.23 | 13 (54.2) | 11 (45.8) | 0.30 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||||

| Stage I | 147 (77.4) | 43 (22.6) | 110 (61.5) | 69 (38.5) | ||

| Stage II | 91 (76.5) | 28 (23.5) | 69 (59.5) | 47 (40.5) | ||

| Stage III | 41 (63.1) | 24 (36.9) | 29 (46.8) | 33 (53.2) | ||

| Stage IV | 42 (73.7) | 15 (26.3) | 31 (51.7) | 29 (48.3) | ||

| N/A (includes all ALL cases) | 23 (88.5) | 3 (11.5) | 14 (56.0) | 11 (44.0) | ||

| Unknown | 15 (75.0) | 5 (25.0) | 0.14 | 10 (50.0) | 10 (50.0) | 0.36 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Surgery only | 45 (80.4) | 11 (19.6) | 32 (60.4) | 21 (39.6) | ||

| Radiation (w/ or w/o surgery) | 42 (85.7) | 7 (14.3) | 32 (72.7) | 12 (27.3) | ||

| Chemotherapy (w/ or w/o surgery) | 172 (76.8) | 52 (23.2) | 126 (56.8) | 96 (43.2) | ||

| Radiation and chemo (w/ or w/o surgery) | 78 (70.3) | 33 (29.7) | 57 (51.8) | 53 (48.2) | ||

| None or unknown | 22 (59.5) | 15 (40.5) | 0.03 | 16 (48.5) | 17 (51.5) | 0.14 |

| General health status | ||||||

| Excellent/very good | 174 (82.5) | 37 (17.5) | 133 (64.9) | 72 (35.1) | ||

| Good | 134 (73.6) | 48 (26.4) | 97 (54.8) | 80 (45.2) | ||

| Fair/poor | 48 (60.0) | 32 (40.0) | 0.0003 | 32 (41.6) | 45 (58.4) | 0.0015 |

| Missinga | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Quality of care | ||||||

| Excellent/very good | 304 (78.4) | 84 (21.6) | 222 (59.4) | 152 (40.6) | ||

| Good | 41 (66.1) | 21 (33.9) | 31 (50.0) | 31 (50.0) | ||

| Fair/poor | 6 (35.3) | 11 (64.7) | <0.0001 | 5 (33.3) | 10 (66.7) | 0.06 |

| Missinga | 8 | 2 | 5 | 6 | ||

| Symptoms | ||||||

| 0–1 | 135 (85.4) | 23 (14.6) | 105 (67.7) | 50 (32.3) | ||

| 2–3 | 100 (78.7) | 27 (21.3) | 71 (58.2) | 51 (41.8) | ||

| 4+ | 124 (64.6) | 68 (35.4) | <0.0001 | 87 (47.0) | 98 (53.0) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| 0 | 247 (78.9) | 66 (21.1) | 185 (60.7) | 120 (39.3) | ||

| 1 | 61 (78.2) | 17 (21.8) | 40 (52.6) | 36 (47.4) | ||

| 2+ | 33 (58.9) | 23 (41.1) | 0.005 | 23 (43.4) | 30 (56.6) | 0.04 |

| Missinga | 18 | 12 | 15 | 13 | ||

| Support group services | ||||||

| Received | 29 (76.3) | 9 (23.7) | 21 (56.8) | 16 (43.2) | ||

| Not received/not needed | 296 (80.0) | 74 (20.0) | 236 (66.3) | 120 (33.7) | ||

| Not received/needed | 34 (49.3) | 35 (50.7) | <0.0001 | 6 (8.7) | 63 (91.3) | <0.0001 |

Note. p values<0.05 are indicated in bold.

Chi-square compares non-missing categories only.

Sarcoma types included Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; N/A, non-applicable; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; w/, with; w/o, without.

Factors associated with social information needs

Multiple logistic regression models examined factors associated with both TAC and MPS needs (Table 2). Participants between the ages of 20 and 29 at diagnosis were more likely (odds ratio [OR]=2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1–4.9) to report a MPS need as those between the ages of 15 and 19 at diagnosis. There was no significant difference in the likelihood of reporting a TAC or MPS need among individuals between the ages of 30 and 39 and teenagers. There was also no significant difference in reporting social information needs between females and males. Both Hispanic AYAs and AYAs of “other” race/ethnicity were more than twice as likely to report a TAC need as non-Hispanic whites (Hispanic: OR=2.4; 95% CI: 1.3–4.6; “other”: OR=2.4; 95% CI: 1.1–5.3); Hispanics were almost 2 times more likely to report a MPS need (a non-significant but marginal difference, p=0.07). Those who reported fair or poor quality of care were 3.6 times as likely (95% CI: 1.1–11.7) to report a TAC need as those who reported excellent quality of care. Those who reported a high number of symptoms were more than 2 times as likely to report both TAC and MPS needs as those who reported 0–1 symptoms (TAC: OR=2.9; 95% CI: 1.5–5.5; MPS: OR=2.3; 95% CI: 1.3–3.9). Finally, participants who reported needing but not participating in a support group were more likely to report TAC (OR=3.6; 95% CI: 1.3–9.8) or MPS (OR=13.3; 95% CI: 4.2-42.3) needs than individuals who did participate in a support group.

Table 2.

Multiple Logistic Regression Model of Factors Associated with Social Information Needs

| |

Talk about cancer with family and friends (TAC) |

Meet peer survivors (MPS)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

n=439, adjusted r2=0.25 |

n=424, adjusted r2=0.29 |

||||

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||||

| 15–19 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 20–29 | 2.1 | 0.8–5.4 | 0.13 | 2.3 | 1.1–4.9 | 0.03 |

| 30–39 | 2.1 | 0.8–5.4 | 0.13 | 1.7 | 0.8–3.8 | 0.17 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Female | 0.6 | 0.3–1.1 | 0.08 | 0.7 | 0.4–1.2 | 0.14 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.7 | 0.7–4.4 | 0.26 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.7 | 0.70 |

| Hispanic | 2.4 | 1.3–4.6 | 0.01 | 1.7 | 1.0–3.2 | 0.07 |

| Other/unknown | 2.4 | 1.1–5.3 | 0.03 | 1.5 | 0.7–3.3 | 0.26 |

| Clinical/health variables | ||||||

| Cancer site | ||||||

| Germ cell | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 0.9 | 0.3–2.0 | 0.70 | 1.1 | 0.6–2.0 | 0.85 |

| NHL | 0.6 | 0.2–1.3 | 0.17 | 1.1 | 0.6–2.0 | 0.86 |

| ALL | 0.1 | 0.01–1.0 | 0.05 | 1.2 | 0.4–4.1 | 0.76 |

| Sarcomab | 0.6 | 0.2–2.2 | 0.40 | 1.2 | 0.4–3.4 | 0.76 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| No/missing/unknown | Ref | |||||

| Surgery only | 0.3 | 0.05–1.5 | 0.14 | — | — | — |

| Radiation (w/ or w/o surgery) | 0.2 | 0.04–1.2 | 0.08 | — | — | — |

| Chemotherapy (w/ or w/o surgery) | 0.3 | 0.07–1.4 | 0.13 | — | — | — |

| Radiation and chemo (w/ or w/o surgery) | 0.6 | 0.1–2.5 | 0.45 | — | — | — |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 1 | 0.9 | 0.4–1.8 | 0.73 | 1.2 | 0.7–2.2 | 0.50 |

| 2+ | 1.4 | 0.7–3.0 | 0.36 | 1.1 | 0.5–2.3 | 0.88 |

| Quality of care | ||||||

| Excellent/very good | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Good | 1.3 | 0.63–2.5 | 0.53 | 1.0 | 0.5–2.0 | 0.94 |

| Fair/poor | 3.6 | 1.1–11.7 | 0.03 | 2.2 | 0.6–8.5 | 0.25 |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| 0–1 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 2–3 | 1.5 | 0.7–3.0 | 0.27 | 1.5 | 0.8–2.6 | 0.19 |

| 4+ | 2.9 | 1.5–5.5 | 0.001 | 2.3 | 1.3–3.9 | 0.004 |

| Support group services | ||||||

| Received | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Not received/not needed | 0.9 | 0.4–2.1 | 0.77 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.3 | 0.22 |

| Not received/needed | 3.6 | 1.3–9.8 | 0.01 | 13.3 | 4.2–42.3 | <0.0001 |

Odds ratios with p values<0.05 are indicated in bold.

Odds ratios adjusted for every other variable in model. MPS model does not include treatment history.

Sarcoma types included Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CI, confidence interval; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; OR, odds ratio; Ref, reference; w/, with; w/o, without.

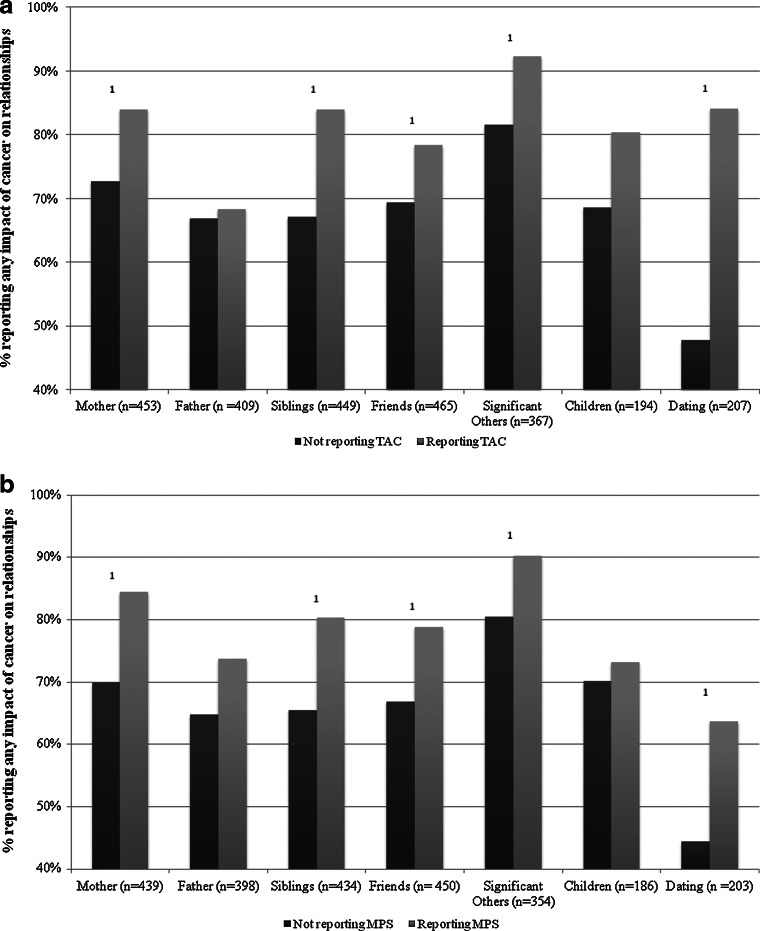

Impact of cancer on relationships and social information needs

Figure 1 compares the proportions of those reporting TAC and MPS needs among individuals who reported a positive or negative impact of cancer on relationships versus those that reported no impact. Participants who reported that cancer had any impact on relationships with their mother, siblings, significant others, or dating were more likely to report a TAC need (p<0.05). The need for information about MPS was significantly higher among participants reporting significant impact on relationships with their mothers, siblings, friends, significant others, or dating (p<0.05).

FIG. 1.

Impact of cancer on relationships as reported by survivors, stratified by survivors who wanted information about (a) Talking about Cancer (TAC) with family and friends and (b) Meeting Peer Survivors (MPS). Sample sizes reflect the number of respondents for each relationship type. 1p<0.05 comparing survivors reporting or not reporting MPS or TAC needs.

Discussion

A large proportion of AYA cancer survivors reported unmet social information needs in our study. Information needs were higher among AYAs in their 20s at diagnosis and those of Hispanic or “other” race/ethnicity. Information needs were also higher in those that needed but did not receive the service of a support group, and in those with a low perceived quality of care. Our findings identify subgroups of AYAs who are most in need of additional social support and suggest targets for future studies and clinical intervention.

Meeting peer survivors

Participants who reported that cancer had either a positive or a negative impact on several significant relationships reported more need for MPS. Given the developmental life stages that AYAs transition through,21 cancer in this age group presents unique social challenges. The desire to connect with peer survivors may extend, in part, from a natural inclination toward peer bonding that is normative and healthy for AYAs.22 However, research has shown cancer experiences may limit the potential to maintain or form new relationships.2,23 Some AYAs report difficulties in maintaining friendships after they are diagnosed with cancer, in part because many peers are unprepared or unable to appreciate the problems that accompany a cancer diagnosis.2 Even when support networks are strong, existing social connections may be inadequate for meeting psychosocial needs, and participation in activities associated with peer groups may be limited.7 Furthermore, opportunities for connecting with peer survivors may also be limited, particularly as cancer is a rare illness for AYAs.24 In our study, this is reflected by the low number of individuals who reported participating in a support group (n=41) compared to the number that wanted to participate in such a group (n=72).

The challenges many AYA cancer support programs face include the diversity of potential members in regard to cultural background and phase along the survivorship continuum, the inclusion of a broad age range, limited geographical coverage, and little funding.1 Being potentially isolated while hospitalized or in recovery at home poses a unique challenge for AYAs who may otherwise be socially oriented and accustomed to being with friends.1 Providing opportunities to engage with peer survivors might help mitigate these challenges.25 Opportunities to connect through online support groups, telephone, and internet chat (e.g., FaceTime or Skype) platforms are increasingly available but not always accessible or widely known.1

Other findings from the study warrant further discussion. Although there are documented barriers to participation in support groups for racial/ethnic minorities, including stigma, cultural taboos, and few support groups with members of similar cultural backgrounds,26,27 this study did not find significant differences across racial/ethnic groups in wanting to meet other AYA survivors, and this suggests several possibilities. The study may have been underpowered to detect statistically significant differences among racial/ethnic groups. Alternatively, despite differences in support group participation level due in part to challenges in availability and access, it is possible that the desire to connect with peer survivors is similar across racial/ethnic and cultural groups.27 Previous studies conducted in adult cancer survivors have found that whites with high socioeconomic status are more likely to participate in online cancer support groups,9,28 indicating the need to partner with AYAs of other racial/ethnic backgrounds to tailor online support groups to these populations as well. Recognizing the differing attitudes and barriers toward participating in online support groups is an important first step toward increasing participation.26 In addition, partnering with AYA cancer patients of diverse backgrounds to help create more tailored community and online support systems may help increase engagement.29 Independent of racial/ethnic status, however, not having participated in a support group predicted higher unmet MPS need in the current study. This suggests that support group participation assists in fulfilling the need for MPS.

Talking about cancer

The need to communicate about cancer may be especially salient to AYA cancer survivors, as cancer is a highly unexpected illness occurring at an exceptionally non-normative time in their lives.30 Being able to understand and communicate about their cancer experiences may be difficult for AYAs, who may have little personal experience with illness. Complicated social dynamics between cancer survivors and their supporters are largely understudied, but a low level of disease awareness among survivors has been associated with low health-related quality of life among caregivers.31 Thus studies are needed to examine the complex and nuanced ways that cancer experiences affect relationships between AYA survivors and their parents, romantic partners, children, and other significant relationships. Recognizing that some AYA survivors may benefit from learning how to talk about their experiences may be an important step to improve psychosocial services for this population.

TAC information need was higher in Hispanic AYAs and AYAs of “other” race/ethnicity. Previous qualitative research identified that caregivers of survivors from family-oriented cultures need psychosocial support.32,33 The proportion of non-Hispanic black participants who reported TAC was similar to that of Hispanics, although this difference was not significant (possibly due to smaller sample size). In addition, participants who reported lower quality of care, higher symptom burden, and lack of access to support groups also reported higher unmet TAC needs; these associations suggest the need for service improvement in the delivery of psychosocial care tailored to AYAs.34 Developing tools for promoting communication among AYA cancer survivors may assist those who struggle to communicate needs and secure emotional support from their friends and family.

Our study indicated that AYAs who reported unmet TAC needs were more likely to report a high impact of cancer on relationships with their mothers, siblings, partners, and friends. Impact on relationships with key supporters, regardless of whether those changes are more positive or negative, may leave survivors needing new strategies for communication. The lack of psychosocial interventions to assist survivors with communicating with partners is at least in part a result of the paucity of research on the impact of cancer on AYAs' relationships.35 Although it may seem that only those survivors who report a negative impact on relationships would potentially need support, our findings suggest that even those who report positive impact desire information about TAC. This suggests that many survivors are seeking, and could benefit from, interventions designed to encourage healthy communication about cancer experiences.

Strengths and limitations

Our findings on the social information needs of AYAs are strengthened by the recruitment of a large number of participants from seven different population-based cancer registries across the United States that currently comprise the largest non-convenience sample of AYA cancer patients. In addition, the study included patients with cancers that have been largely understudied, such as non-white AYAs. The generalizability of our findings may be limited, however, by our eligibility criteria, which included the ability to read and write English, as well as an overall response rate of 43%, although no major differences between respondents and non-respondents were found.11 Some of the participants in our study were currently undergoing active treatment, which may affect reporting of social information needs. In addition, the study was underpowered to find statistically significant differences for some groups, including participants of Asian/Pacific Islander ethnicity. Finally, the exclusion of participants who responded “does not apply” or left the social information needs questions blank may have slightly biased our results, although the proportion of these responses was low.

Conclusion

A substantial proportion of AYAs in our study reported unmet social information needs, with needs higher in Hispanics and “other” races/ethnicities, and those who reported higher symptom burden, lower quality of care, and an unmet support group need. Future studies should examine barriers and explore interventions for meeting these needs in diverse populations with the intent of improving access to support groups for all AYA cancer survivors. Our findings also suggest that many AYA cancer survivors are seeking, and could benefit from, interventions designed to encourage healthy communication about cancer experiences. Understanding the factors that are associated with unmet social information needs is important for providers of AYA cancer psychosocial support services, given the relationship between social support and quality of life previously demonstrated for this population.36 AYAs most in need of additional social support and information should be targeted for future studies and clinical interventions.

Acknowledgments

The study authors would like to thank Gretchen Keel for her assistance with data analysis for this project. Supported by contracts N01-PC-35136, N01-PC-35139, N01-PC-35142, N01-PC-35143, N01-PC-35145, N01-PC-54402, and N01-PC-54404.

AYA HOPE Study Collaborative Group:

• California Cancer Registry/Public Health Institute (Sacramento, CA): Rosemary Cress, DrPH (Principal Investigator); Gretchen Agha; Mark Cruz

• Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, WA): Stephen M. Schwartz, PhD (Principal Investigator); Martha Shellenberger; Tiffany Janes

• Karmanos Cancer Center (Detroit, MI): Ikuko Kato, PhD (Principal Investigator); Ann Bankowski; Marjorie Stock

• Louisiana State University (New Orleans, LA): Xiao-Cheng Wu, MD, MPH (Principal Investigator); Vivien Chen; Bradley Tompkins

• Cancer Prevention Institute of California (Fremont, CA): Theresa Keegan, PhD, MS (Principal Investigator); Laura Allen; Zinnia Loya; Karen Hussain

• University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA): Charles F. Lynch, MD, PhD (Principal Investigator); Michele M. West, PhD; Lori A. Odle, RN

• University of Southern California (Los Angeles, CA): Ann Hamilton, PhD (Principal Investigator); Jennifer Zelaya; Mary Lo, MS; Urduja Trinidad, MD

• National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD): Linda C. Harlan, BSN, MPH, PhD, (Investigator); Ashley Wilder Smith, PhD, MPH (Co-Investigator); Sonja M. Stringer, MPH; Gretchen Keel, BS, BA

• Consultants: Arnold Potosky, PhD; Keith Bellizzi, PhD; Karen Albritton, MD; Debra L. Friedman, MD; Michael Link, MD; Brad Zebrack, PhD

Disclaimer

This article is a United States Government work and, as such, is in the public domain in the United States. This manuscript was presented in part at the American Psychosocial Oncology Society 9th Annual Conference, held in Miami, Florida, February 23–25, 2012:

Kent EE, Smith AW, Keegan THM, Lynch CF, Wu XC, Hamilton AS, Kato I, Schwartz SM, Harlan LC (2012). Social support needs in adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Treadgold CL. Kuperberg A. Been there, done that, wrote the blog: the choices and challenges of supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4842–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kent EE. Parry C. Montoya MJ, et al. “You're too young for this”: adolescent and young adults' perspectives on cancer survivorship. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(2):260–79. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.644396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance; Aug, 2006. [Jan 15;2012 ]. Closing the gap: research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer (NIH Publication No. 06-6067) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zebrack B. Chesler MA. Kaplan S. To foster healing among adolescents and young adults with cancer: what helps? What hurts? Support Care Cancer. 2009;18(1):131–5. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0719-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langeveld NE. Stam H. Grootenhuis MA, et al. Quality of life in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10(8):579–600. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cacioppo JT. Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(3 Suppl):S39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evan EE. Zeltzer LK. Psychosocial dimensions of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Cancer. 2006;107(7 Suppl):1663–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zebrack B. Bleyer A. Albritton K, et al. Assessing the health care needs of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors. Cancer. 2006;107(12):2915–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoybye MT. Dalton SO. Christensen J, et al. Social and psychological determinants of participation in internet-based cancer support groups. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(5):553–60. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoybye MT. Dalton SO. Deltour I, et al. Effect of Internet peer-support groups on psychosocial adjustment to cancer: a randomised study. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(9):1348–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harlan LC. Lynch CF. Keegan TH, et al. Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: the AYA HOPE Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):305–14. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0173-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keegan TH. Lichtensztajn DY. Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):239–50. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsons HM. Harlan LC. Seibel NL, et al. Clinical trial participation and time to treatment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: does age at diagnosis or insurance make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(30):4045–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodgate RL. The importance of being there: perspectives of social support by adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2006;23(3):122–34. doi: 10.1177/1043454206287396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grande GE. Myers LB. Sutton SR. How do patients who participate in cancer support groups differ from those who do not? Psychooncology. 2006;15(4):321–34. doi: 10.1002/pon.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plante WA. Lobato D. Engel R. Review of group interventions for pediatric chronic conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(7):435–53. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.7.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sansom-Daly UM. Peate M. Wakefield CE, et al. A systematic review of psychological interventions for adolescents and young adults living with chronic illness. Health Psychol. 2012;31(3):380–93. doi: 10.1037/a0025977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellizzi KM. Miller MF. Arora NK, et al. Positive and negative life changes experienced by survivors of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(2):188–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02872673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganz PA. Desmond KA. Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(1):39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellizzi KM. Smith A. Schmidt S, et al. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118(20):5155–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abrams AN. Hazen EP. Penson RT. Psychosocial issues in adolescents with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(7):622–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson AL. Marsland AL. Marshal MP, et al. Romantic relationships of emerging adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):767–74. doi: 10.1002/pon.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bleyer A. Viny A. Barr R. Cancer in 15- to 29-year-olds by primary site. Oncologist. 2006;11(6):590–601. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-6-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D'Agostino NM. Penney A. Zebrack B. Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117(10 Suppl):2329–34. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Im EO. Chee W. The use of internet cancer support groups by ethnic minorities. J Transcult Nurs. 2008;19(1):74–82. doi: 10.1177/1043659607309140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avis M. Elkan R. Patel S, et al. Ethnicity and participation in cancer self-help groups. Psychooncology. 2008;17(9):940–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Im EO. Chee W. Lim HJ, et al. Patients' attitudes toward internet cancer support groups. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(3):705–12. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.705-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casillas J. Kahn KL. Doose M, et al. Transitioning childhood cancer survivors to adult-centered healthcare: insights from parents, adolescent, and young adult survivors. Psychooncology. 2010;19(9):982–90. doi: 10.1002/pon.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Revenson TA. Pranikoff JR. A contextual approach to treatment decision making among breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. 2005;24(4 Suppl):S93–8. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadopoulos A. Vrettos I. Kamposioras K, et al. Impact of cancer patients' disease awareness on their family members' health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional survey. Psychooncology. 2011;20(3):294–301. doi: 10.1002/pon.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones BL. Volker DL. Vinajeras Y, et al. The meaning of surviving cancer for Latino adolescents and emerging young adults. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(1):74–81. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b4ab8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yi J. Zebrack B. Self-portraits of families with young adult cancer survivors: using photovoice. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2010;28(3):219–43. doi: 10.1080/07347331003678329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nathan PC. Hayes-Lattin B. Sisler JJ, et al. Critical issues in transition and survivorship for adolescents and young adults with cancers. Cancer. 2011;117(10 Suppl):2335–41. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpentier MY. Fortenberry JD. Romantic and sexual relationships, body image, and fertility in adolescent and young adult testicular cancer survivors: a review of the literature. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(2):115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zebrack B. Isaacson S. Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1221–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]