Abstract

Background

There continues to be an ongoing debate regarding the utility of Head CT scans in patients with a normal Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) after minor head injury. The objective of this study is to determine patient and injury characteristics that predict a positive head CT scan or need for a Neurosurgical Procedure (NSP) among patients with blunt head injury and a normal GCS.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective analysis of adult patients in the National Trauma Data Bank who presented to the ED with a history of blunt head injury and a normal GCS of 15. The primary outcomes were a positive head CT scan or a NSP. Multivariate logistic regression controlling for patient and injury characteristics was used to determine predictors of each outcome.

Results

Out of a total of 83,566 patients, 24,414 (29.2%) had a positive head CT scan and 3,476 (4.2%) underwent a NSP. Older patients and patients with a history of fall (as compared to a motor vehicle crash) were more likely to have a positive finding on a head CT scan. Male patients, African-Americans (as compared to Caucasians) and those who presented with a fall were more likely to have a NSP.

Conclusions

Older age, male gender, ethnicity and mechanism of injury are significant predictors of a positive finding on head CT scans and the need for neurosurgical procedures. This study highlights patient and injury specific characteristics that may help in identifying patients with supposedly minor head injury who will benefit from a head CT scan.

Keywords: Head Injury, Outcomes, Ethnicity, Gender, Age, Disparities, Multivariate Regression, Blunt Trauma

Introduction

In the United States, approximately one million patients with head injuries are seen every year in the Emergency Department (ED). More than 80% of these injuries are considered minor. 1-3 An estimated 10% of patients with minor head injury yield positive results on a CT scan, and less than 1% subsequently require a neurosurgical intervention.4-6 The rate of intracranial lesions on a CT scan is even lower for patients with a normal score of 15 on the Glasgow Coma Scale (6-9%).7-9 Thus, the overwhelming majority of head CT scans performed among patients with minor head injury in the ED are negative. Ascertainment of patients who will benefit from a head CT after injury remains a challenge.

Several studies have focused on evaluating clinical features that may identify minor head injury patients who would benefit from neuroimaging.4, 6, 10, 11 Two such prediction rules have arisen from The New Orleans study and the Canadian CT head rule study.4, 6 The New Orleans study was limited to patients with a normal GCS score of 15, whereas the Canadian CT head rule study included patients with a GCS score of 13-15. Both rules have demonstrated 100% sensitivity in identifying patients who required neurosurgical intervention, as well as most patients with traumatic intracranial findings on a CT scan, in internal and external validation studies. 12-14 However, both are only applicable to patients with minor head injury who experienced a loss of consciousness or amnesia. In contrast, the CHIP (CT in head injury patients) study developed a prediction rule for the selective use of CT in all patients with minor head injury with or without loss of consciousness and a GCS score of 13 to 14, or with a GCS score of 15 and at least one risk factor (for example, deficit in short term memory, amnesia of the traumatic event and post-traumatic seizure, among others). 11 However, there is still continuing debate about which patients with mild head injury and normal mental status require imaging.

At present, there are no guidelines to suggest which patients with a GCS of 15 should receive a head CT based on mechanism of injury or patient characteristics alone. The role of head CT in patients with minor head injury and normal GCS remains controversial. The objective of this study was to identify patient and injury characteristics that predict a positive head CT scan or a need for neurosurgical procedure in patients with blunt head injury and a GCS of 15.

Methods

This study was a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of all patients with blunt head injury in the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB; version 7.1) between 2002 and 2006. The NTDB is maintained by the American College of Surgeons and consists of approximately 1.8 million trauma incidents contributed by more than 900 trauma centers in the United States and its territories. As data reporting to the NTDB is voluntary, some institutions did not routinely report head CT scan results. Thus, we limited our study to patients from hospitals that submitted data on results of head CT scan in the ED along with the more routinely reported hospital data.

All patients 16 years or older who presented to the ED with minor head injury were included. This study defined minor head injury as history of blunt head injury and a GCS of 15. Patients with head injury were identified using Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) code for the head AIS divides the body into six regions (head and neck, face, chest, abdomen, pelvis and extremities and general) and classifies the severity of injuries in each region based on clinical experience (1=minor; 2=moderate; 3=severe, not life-threatening; 4=severe, life threatening, survival probable; 5=critical, survival uncertain; 6=fatal). Patients with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 E Code commensurate with a blunt trauma mechanism were included. The two primary outcomes investigated were: 1) positive head CT scan and 2) need for neurosurgical procedure (NSP). CT scan results were documented as positive or negative by the reporting hospital. Patients who underwent a neurosurgical procedure were identified by ICD 9 Procedure codes and were inclusive of both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Patients were further categorized into patients who had a therapeutic procedure and patients who had a diagnostic procedure as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Procedure codes

| Therapeutic Neurosurgical Procedure | Diagnostic Neurosurgical Procedure |

|---|---|

| Cranial puncture (01.00-01.09) | Diagnostic procedures on skull, brain, and cerebral meninges (01.10-01.19) |

| Craniotomy and craniectomy (01.20-01.28) | |

| Incision of brain and cerebral meninges (01.30-01.39) | |

| Operations on thalamus and globus pallidus (01.40-01.42) | |

| Other excision or destruction of brain and meninges (01.50-01.59) | |

| Excision of lesion of skull (01.60) | |

| Cranioplasty (02.00-02.07) | |

| Repair of cerebral meninges (02.10-02.14) | |

| Ventriculostomy (02.20) | |

| Extracranial ventricular shunt (02.30-02.39) | |

| Revision, removal, and irrigation of ventricular shunt (02.40-02.43) | |

| Other operations on skull, brain, and cerebral meninges (02.90-2.99) |

Patient demographics included age, gender and race/ethnicity.15 We used Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS) for head to calculate the severity of head injury and the Injury Severity Score (ISS) to calculate the overall injury intensity. Other injury characteristics included presence of shock at admission (systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg) and mechanism of injury.16 Mechanism of injury was categorized into motor vehicle crash, fall and others (pedal cyclist, pedestrian struck by motor vehicle, alternate means of transport, motorcyclist etc).17 Mechanisms such as cyclist, pedestrian struck and motor cyclists were grouped together for model parsimony. Insurance status was also added to the model to control for differences in outcomes based on the reported insurance status (insured versus uninsured).18 Finally, year of admission, geographical location and level of the trauma center were also added.

Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables and x2 was used to compare categorical variables for univariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression was then used to determine the independent predictors of a positive head CT scan or a NSP and their effects, adjusted for potential confounders. The final model included the following variables: age, gender, ethnicity, severity of head injury, overall injury intensity, presence of shock on admission, mechanism of injury, insurance status, year of admission and geographical location and level of the trauma center. To control for the potential differences in treatments and procedures between various facilities, clustering by facility ID was included during the multivariate analysis.19 To ensure that missing data did not bias the results, a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputations was also performed.20 All analyses were carried out in Stata/MP version 11 (Stata, College Station, TX), and statistical significance was defined as a p value of less than .05

Results

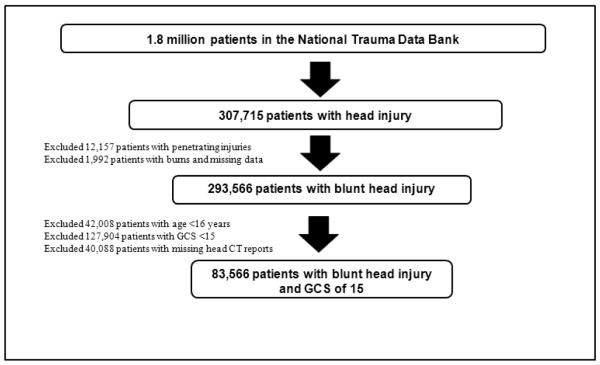

There were 1,862,348 patient cases in the NTDB 7.1. Of these, 105,469 patients (age 16 and older) presented to the ED with blunt head injury and a GCS of 15. After excluding patients with missing head CT scan results, 83,566 patients were available for univariate analysis. Complete data on all variables was available for 70,647 patients and these were included in the final regression models. Figure 1 outlines patient selection.

Figure 1.

Patient Selection

Table 2 demonstrates the demographic distribution of the study population. The median age was 39 years (interquartile range (IQR): 24-55 years). The majority of patients were male (66.7%). In terms of ethnicity, this sample consisted of 67% Caucasians, 14% African-Americans, and 9% Hispanics. The median Injury Severity Score (ISS) was 10 (IQR: 5-17). 64% of patients had an AIS for head of 1 or 2. 1.6% of our patients presented with shock. The most common mechanism of injury was motor vehicle crash (60%). Insured patients accounted for 77% of the study population. Patients were predominantly admitted to Level I and II trauma centers (52% and 29% respectively).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and Injury Severity Characteristics

| Number of patients (n) | Percentage of Total Sample |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age in years 16-25 | 22,322 | 26.7% |

| 26-35 | 13,507 | 16.2% |

| 36-45 | 13,430 | 16.1% |

| 46-55 | 11,390 | 13.6% |

| 56-65 | 7,034 | 8.4% |

| 66-75 | 5,495 | 6.6% |

| 76-84 | 5,688 | 6.8% |

| 85 and above | 2,461 | 2.9% |

| Gender Male | 55,716 | 66.7% |

| Female | 27,542 | 33.0% |

| Presented with Shock | 1,364 | 1.6% |

| Race White | 55,987 | 67.0% |

| African-American | 11,237 | 13.5% |

| Hispanic | 7,791 | 9.3% |

| Others | 4,167 | 5.0% |

| ISS 0-8 | 31,053 | 37.2% |

| 9-15 | 23,467 | 28.1% |

| 16-24 | 20,133 | 24.1% |

| 25-75 | 8,404 | 10.1% |

| Maximum head AIS score 1 | 16,602 | 19.9% |

| 2 | 37,272 | 44.6% |

| 3 | 16,001 | 19.2% |

| 4 | 11,832 | 14.2% |

| 5 | 1,859 | 2.2% |

| Mechanism of injury Fall | 17,738 | 21.2% |

| MVC | 49,754 | 59.5% |

| Others | 15,752 | 18.9% |

Out of a total of 83,566 patients, 24,414 (29.2%) had a positive CT scan and 3,476 (4.2%) subsequently underwent a neurosurgical procedure. Of these, 2,088 patients (2.5%) underwent a therapeutic procedure while the rest (1.7%) underwent a diagnostic procedure. The overall mortality was 1.5% (1,218/83,566). Amongst patients who had a positive head CT scan, 3% (732/24,414) died during hospital stay and approximately 7% (143/2088) of the patients who subsequently underwent a therapeutic procedure died during hospital stay. Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate the results of the univariate analysis for both outcomes, positive head CT scan and neurosurgical procedure, respectively. Age, ethnicity and mechanism of injury are significant on univariate analysis for both outcomes. In addition, insurance status and male gender are significantly associated with a positive CT scan and undergoing a neurosurgical procedure, respectively.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis: Predictors of positive CT scan in patients with blunt head injury and GCS of 15

| Patients with negative head CT n=59,152 |

Patients with positive head CT n=24,414 |

Total n=83,566 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p-value** | |

| Age in years 16-25* | 17,411 (78.0) | 4,911 (22.0) | 22,322 (100) | <0.001 |

| 26-35 | 10,562 (78.2) | 2,945 (21.8) | 13,507 (100) | |

| 36-45 | 10,073 (75.0) | 3,357 (25.0) | 13,430 (100) | |

| 46-55 | 8,009 (70.3) | 3,381 (29.7) | 11,390 (100) | |

| 56-65 | 4,523 (64.3) | 2,511 (35.7) | 7,034 (100) | |

| 66-75 | 3,055 (55.6) | 2,440 (44.4) | 5,495 (100) | |

| 76-84 | 2,761 (48.5) | 2,927 (51.5) | 5,688 (100) | |

| 85 and above | 1,167 (47.4) | 1,294 (52.6) | 2,461 (100) | |

| Gender Male | 39,484 (70.9) | 16,232 (29.1) | 55,716 (100) | 0.975 |

| Female | 19,521 (70.9) | 8,021 (29.1) | 27,542 (100) | |

| Hypotensive on arrival Yes | 994 (72.9) | 370 (27.1) | 1,364 (100) | 0.088 |

| No | 57,831 (70.8) | 23,901 (29.2) | 81,732 (100) | |

| Race White* | 39,284 (70.2) | 16,703 (29.8) | 55,987 (100) | <0.001 |

| African-American | 8,536 (76.0) | 2,701 (24.0) | 11,237 (100) | |

| Hispanic | 5,643 (72.4) | 2,148 (27.6) | 7,791 (100) | |

| Others | 2,682 (64.4) | 1,485 (35.6) | 4,167 (100) | |

| Insured Yes | 44,736 (69.9) | 19,225 (30.1) | 63,961 (100) | <0.001 |

| No | 11,091 (75.4) | 3,625 (24.6) | 14,716 (100) | |

| ISS 0-8 | 29,834 (96.1) | 1,219 (3.9) | 31,053 (100) | < 0.001 |

| 9-15 | 16,271 (69.3) | 7,196 (30.7) | 23,467 (100) | |

| 16-24 | 9,189 (45.6) | 10,944 (54.4) | 20,133 (100) | |

| 25-75 | 3,452 (41.1) | 4,952 (58.9) | 8,404 (100) | |

| Maximum head AIS score 1 | 16,024 (96.5) | 578 (3.5) | 16,602 (100) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 35,719 (95.8) | 1,553 (4.2) | 37,272 (100) | |

| 3 | 6,142 (38.4) | 9,859 (61.6) | 16,001 (100) | |

| 4 | 1,097 (9.3) | 10,735 (90.7) | 11,832 (100) | |

| 5 | 170 (9.1) | 1,689 (90.9) | 1,859 (100) | |

| Mechanism of injury MVC* | 39,415 (79.2) | 10.339 (20.8) | 49,754 (100) | <0.001 |

| Fall | 9,223 (52.0) | 8,515 (48.0) | 17,738 (100) | |

| Cyclist | 10,286 (65.3) | 5,466 (34.7) | 15,752 (100) |

Represents the reference groups for the multivariate logistic regression model

Statistical significance was defined as p value < .05

Table 4.

Univariate analysis: Predictors of NSP in patients with blunt head injury and GCS of 15

| Patients who did not undergo NSP n= 80,090 |

Patients who underwent NSP n=3,476 |

Total n=83,566 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | N (%) | n (%) | p-value** | |

| Age in years 16-25* | 21,575 (96.7) | 747 (3.4) | 22,322 (100) | <0.001 |

| 26-35 | 13,036 (96.5) | 471 (3.5) | 13,507 (100) | |

| 36-45 | 12,949 (96.4) | 481 (3.6) | 13,430 (100) | |

| 46-55 | 10,970 (96.3) | 420 (3.7) | 11,390 (100) | |

| 56-65 | 6,704 (95.3) | 330 (4.7) | 7,034 (100) | |

| 66-75 | 5,120 (93.2) | 375 (6.8) | 5,495 (100) | |

| 76-84 | 5,289 (93.0) | 399 (7.0) | 5688 (100) | |

| 85 and above | 2,301 (93.5) | 160 (6.5) | 2,461 (100) | |

| Gender Male | 53,202 (95.5) | 2,514 (4.5) | 55,716 (100) | <0.001 |

| Female | 26,605 (96.6) | 937 (3.4) | ||

| Hypotensive on arrival Yes | 1,305 (95.7) | 59 (4.3) | 1,364 (100) | 0.741 |

| No | 78,344 (95.9) | 3,388 (4.2) | ||

| Race Caucasian* | 53,639 (95.8) | 2,348 (4.2) | 55,987 (100) | 0.013 |

| African-American | 10,712 (95.3) | 525 (4.7) | 11,237 (100) | |

| Hispanic | 7,501 (96.3) | 290 (3.7) | 7,791 (100) | |

| Others | 3,984 (95.6) | 183 (4.4) | 4,167 (100) | |

| Insured Yes | 61,241 (95.8) | 2,720 (4.3) | 63,961 (100) | 0.161 |

| No | 14,128 (96.0) | 588 (4.0) | 14,716 (100) | |

| ISS 0-8 | 30,913 (99.6) | 140 (0.5) | 31,053 (100) | <0.001 |

| 9-15 | 22,814 (97.2) | 653 (2.8) | 23,467 (100) | |

| 16-24 | 18,702 (92.9) | 1,431 (7.1) | 20,133 (100) | |

| 25-75 | 7,165 (85.3) | 1,239 (14.7) | 8404 (100) | |

| Maximum head AIS score 1 | 16,386 (98.7) | 216 (1.3) | 16,602 (100) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 36,842 (98.9) | 430 (1.2) | 37,272 (100) | |

| 3 | 15,274 (95.5) | 727 (4.5) | 16,001 (100) | |

| 4 | 10,517 (88.9) | 1,315 (11.1) | 11,832 (100) | |

| 5 | 1,071 (57.6) | 788 (42.4) | 1,859 (100) | |

| Mechanism of injury MVC* | 48,322 (97.1) | 1,432 (2.9) | 49,754 (100) | <0.001 |

| Fall | 16,496 (93.0) | 1,242 (7.0) | 17,738 (100) | |

| Others | 14,967 (95.0) | 785 (5.0) | 15,752 (100) |

Represents the reference groups for the multivariate logistic regression model

Statistical significance was defined as p value < .05

Table 5 demonstrates the results of the multivariate logistic regression model for both outcomes: a positive CT scan or a neurosurgical procedure. After adjusting for patient, injury and demographic factors, we found that age and fall as a mechanism of injury are independent predictors of a positive CT scan. As age increased in increments of 10, the odds of a positive CT scan increased up to a maximum of 1.81 for patients 76-84 years old as compared to patients aged 16-25 years. Patients who presented with a history of fall had increased odds of a positive CT scan as compared to those with a history of motor vehicle crash (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.43-1.72).

Table 5.

Adjusted Odds ratios for Predictors of Head CT scan or Neurosurgical Intervention in Patients with Minor Head Injury (n=70,647 patients)*

| Positive CT scan | Neurosurgical Intervention | |

|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||

| 16-25 | 1 | 1 |

| 26-35 | 0.98 (0.89-1.07) | 1.08 (0.90-1.30) |

| 36-45 | 1.11 (1.00-1.23) | 0.91 (0.80-1.02) |

| 46-55 | 1.17 (1.05-1.31) | 0.79 (0.70-0.89) |

| 56-65 | 1.31 (1.16-1.48) | 0.83 (0.72-0.96) |

| 66-75 | 1.73 (1.51-1.98) | 1.08 (0.95-1.22) |

| 76-84 | 1.81 (1.50-2.18) | 0.81 (0.69-0.95) |

| 85 and above | 1.46 (1.20-1.78) | 0.71 (0.55-0.91) |

| Male gender | 0.97 (0.92-1.03) | 1.27 (1.14-1.42) |

| Hypotensive on arrival | 0.92 (0.76-1.12) | 1.04 (0.78-1.38) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 1 | 1 |

| African-American | 0.96 (0.80-1.16) | 1.21 (1.09-1.35) |

| Hispanic | 1.11 (1.00-1.23) | 1.02 (0.85-1.24) |

| Others | 1.33 (1.03-1.73) | 1.17 (0.95-1.46) |

| Covered by insurance | 1.02 (0.91-1.13) | 0.91 (0.77-1.07) |

| Mechanism of injury | ||

| MVC | 1 | 1 |

| Fall | 1.57 (1.43-1.72) | 1.46 (1.27-1.68) |

| Others | 1.37 (1.24-1.50) | 1.31 (1.15-1.50) |

| Positive head CT | - | 1.28 (1.04-1.57) |

Model was adjusted for overall injury severity (using Injury Severity Score), severity of head injury (using Abbreviated Injury Score for Head region), year of presentation and region of the trauma center.

In comparison, male gender, African-American ethnicity and fall as a mechanism of injury were independent predictors of the need for a NSP. We performed a subgroup analysis to identify if there were separate predictors of therapeutic and diagnostic neurosurgical procedures. Male patients (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.22-1.54) and patients with a history of fall (OR, 1.84; CI 1.61-2.10) were more likely to get a therapeutic neurosurgical procedure. In comparison, African-American patients (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.14-1.56) were more likely to get a diagnostic neurosurgical procedure, while older patients (age greater than 75 years) and patients without insurance (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.72-0.98) were less likely to get a diagnostic procedure. We also looked at each ethnicity separately to determine if there were gender discrepancies and found that male Caucasians had increased odds of getting a NSP as compared to female Caucasian patients. No such effect was observed for African-American and Hispanic patients.

Sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation to account for the approximately 16% of co-variate data that was missing yielded results that were qualitatively similar to the non-imputed results. Only very minor differences in odds ratios were noticed during multivariate logistic regression analyses on both the imputed and non-imputed datasets. No statistically significant findings changed and only the non-imputed results are reported.

Discussion

This study reviewed 83,566 patients in the National Trauma Data Bank with blunt head injury and a normal GCS on presentation to the ED. Of these, 29.2% of the patients with mild head injury had a positive CT scan, and 4.2% subsequently underwent a neurosurgical procedure. Older age, male gender, African-American race and fall as a mechanism of injury are significant predictors of a positive finding on a head CT scan or of neurosurgical interventions in patients with minor head injury. This study highlights patients and injury characteristics that may help in identifying patients with supposedly minor head injury who will benefit from neuroimaging.

The rate of intracranial complications due to minor head injury is reported to be approximately between 6-21%, and a neurosurgical intervention is required in only a minority of patients (0.4-1%).4, 6, 8, 21 This study reports a markedly higher prevalence of abnormal CT scans (29.2%) and neurosurgical procedures (4.2%). Even if diagnostic neurosurgical procedures are disregarded, 2.5% of the patient population underwent a therapeutic neurosurgical procedure. The higher prevalence of both outcomes in this study may be due to a larger patient population from a national trauma database, as compared to earlier single institution studies. Nevertheless, this finding is particularly worrisome as it suggests that a normal mental status examination on its own does not exclude significant head injury.

This study specifically evaluated patient and injury characteristics as predictors of a positive head CT scan or a neurosurgical procedure. Older age was found to be a significant predictor of a positive CT scan. This finding is supported by previous studies including Jeret et. al, who prospectively studied patients with non-penetrating head trauma and a GCS score of 15 and also found increasing age to be significantly associated with an abnormal CT scan.9 Similarly, in another study of 1,429 patients, Haydel et. al suggested age greater than 60 years as one of the seven criteria that may be used to obtain a CT scan.4 Additionally, the CHIP study proposed age greater than 60 years as one of the major criteria for obtaining a head CT scan.

A significant gender disparity was also noted in the need for a NSP. This adds to the current ongoing debate about the role of gender in trauma outcomes. Previous studies have shown that women have significantly lower mortality rates than men of similar age after traumatic injury.22 Data from the NTDB exploring the neuroprotective role of estrogen and progesterone after traumatic brain injury concluded that female gender was associated with improved outcomes after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury.23 Whereas no differences in head CT were noted, male patients were reported to be more likely to undergo a NSP compared to female patients. The specific reasons for this gender difference cannot be determined from this analysis, and future research is needed to evaluate this disparity.

We further explored whether this finding was specific to a certain ethnic group and found that male Caucasian patients were more likely to undergo a NSP compared to female Caucasian patients. Although we observed a similar association for African-American patients, it was not statistically significant. This may have been due to the smaller number of African-American patients in our model. Whitman et. al examined a similar relationship among Caucasian and African-American patients and concluded that males were more likely than females to sustain a head injury in each ethnic group.24 African-American patients in this study were more likely to undergo a neurosurgical intervention. Interestingly, African-American patients were also more likely to get a diagnostic neurosurgical procedure when compared to Caucasians.

Patients with a history of fall were more likely to have a positive CT scan finding and a neurosurgical intervention. Similarly, Smit et. al reported that history of fall from any elevation is one of the 8 minor criteria for obtaining a head CT scan in patients with mild head injury.11 In contrast, other studies have reported that patients with a history of assault or a pedestrian struck by a motor vehicle have a greater chance of a positive CT scan.9 This finding raises the question: are we imaging patients involved in motor vehicle accidents with greater frequency than required? On the other hand, are we missing intracranial injuries in patients with a history of fall and normal mental status? This finding suggests the need to consider falls as a mechanism associated with significant injury.

This study has several limitations because of its retrospective nature. Data were not available on important clinical variables such as headache, vomiting and deficits in short-term memory, and we could not adjust for these factors in our final model. It has been suggested that there may be a reporting bias in the NTDB towards patients who have a more severe hospital course and undergo surgery. Secondly, one of the inclusion criterions for the NTDB is hospital admission. Thirdly, we used head AIS as part of our study criteria to identify our patient sample from the NTDB. All these factors may have led to the inflated prevalence of our study outcomes but is unlikely to affect their possible predictors. Despite these limitations, with a sample size of more than 80,000 patients, this is the largest reported multi-center study to date to evaluate predictors of a positive CT scan or NSP in patients with mild head injury and a normal GCS.

In conclusion, a normal GCS in a patient with minor head injury does not preclude the need for imaging or neurosurgical intervention. The threshold for imaging patients with minor head injury may need to be lowered from age 65 years or greater to age 40 years or greater. This study identified patient and injury specific characteristics that may help in identifying patients with minor head injury who will benefit from a head CT scan. Future work that can incorporate demographic and injury specific characteristics with clinical data in similarly large datasets will pave the way for definitive clinical criteria that may be used to identify such patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the American College of Surgeons-Committee on Trauma, Melanie Neal (NTDB program manager) and the many others who have made the NTDB a reality. We would also like to thank Ms. Valerie Kaye Scott BA, MSPH (Candidate) for her editorial assistance with preparing this manuscript.

Financial support for this work was provided by: National Institutes of Health/NIGMS K23GM093112-01 and American College of Surgeons C. James Carrico Fellowship for the study of Trauma and Critical Care (Dr. Haider and Dr. Kisat)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jager TE, Weiss HB, Coben JH, Pepe PE. Traumatic brain injuries evaluated in U.S. emergency departments, 1992-1994. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(2):134–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutland-Brown W, Langlois JA, Thomas KE, Xi YL. Incidence of traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2003. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21(6):544–8. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200611000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns JJ, Jr., et al. Clinical policy: neuroimaging and decisionmaking in adult mild traumatic brain injury in the acute setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(6):714–48. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haydel MJ, Preston CA, Mills TJ, et al. Indications for computed tomography in patients with minor head injury. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(2):100–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibanez J, Arikan F, Pedraza S, et al. Reliability of clinical guidelines in the detection of patients at risk following mild head injury: results of a prospective study. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(5):825–34. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.5.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen K, et al. The Canadian CT Head Rule for patients with minor head injury. Lancet. 2001;357(9266):1391–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller EC, Derlet RW, Kinser D. Minor head trauma: Is computed tomography always necessary? Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(3):290–4. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller EC, Holmes JF, Derlet RW. Utilizing clinical factors to reduce head CT scan ordering for minor head trauma patients. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(4):453–7. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(97)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeret JS, Mandell M, Anziska B, et al. Clinical predictors of abnormality disclosed by computed tomography after mild head trauma. Neurosurgery. 1993;32(1):9–15. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199301000-00002. discussion 15-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borczuk P. Predictors of intracranial injury in patients with mild head trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(6):731–6. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smits M, Dippel DW, Steyerberg EW, et al. Predicting intracranial traumatic findings on computed tomography in patients with minor head injury: the CHIP prediction rule. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(6):397–405. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-6-200703200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabbri A, Servadei F, Marchesini G, et al. Prospective validation of a proposal for diagnosis and management of patients attending the emergency department for mild head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):410–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.016113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smits M, Dippel DW, de Haan GG, et al. External validation of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria for CT scanning in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005;294(12):1519–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, et al. Comparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005;294(12):1511–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haider AH, Efron DT, Haut ER, et al. Black children experience worse clinical and functional outcomes after traumatic brain injury: an analysis of the National Pediatric Trauma Registry. J Trauma. 2007;62(5):1259–62. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31803c760e. discussion 1262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oyetunji T, Crompton JG, Efron DT, et al. Simplifying physiologic injury severity measurement for predicting trauma outcomes. J Surg Res. 159(2):627–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haider AH, Chang DC, Haut ER, et al. Mechanism of injury predicts patient mortality and impairment after blunt trauma. J Surg Res. 2009;153(1):138–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haider AH, Chang DC, Efron DT, et al. Race and insurance status as risk factors for trauma mortality. Arch Surg. 2008;143(10):945–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.10.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roudsari B, Field C, Caetano R. Clustered and missing data in the US National Trauma Data Bank: implications for analysis. Inj Prev. 2008;14(2):96–100. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.017129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oyetunji TA, Crompton JG, Ehanire ID, et al. Multiple imputation in trauma disparity research. J Surg Res. 165(1):e37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.af Geijerstam JL, Britton M. Mild head injury - mortality and complication rate: meta-analysis of findings in a systematic literature review. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2003;145(10):843–50. doi: 10.1007/s00701-003-0115-1. discussion 850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haider AH, Crompton JG, Chang DC, et al. Evidence of hormonal basis for improved survival among females with trauma-associated shock: an analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma. 69(3):537–40. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181efc67b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry C, Ley EJ, Tillou A, et al. The effect of gender on patients with moderate to severe head injuries. J Trauma. 2009;67(5):950–3. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181ba3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitman S, Coonley-Hoganson R, Desai BT. Comparative head trauma experiences in two socioeconomically different Chicago-area communities: a population study. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119(4):570–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]