Abstract

Purpose

Resiliency theory posits that some youth exposed to risk factors do not develop negative behaviors due to the influence of promotive factors. This study examines the effects of cumulative risk and promotive factors on adolescent violent behavior and tests two models of resilience – the compensatory model and the protective model – in a sample of adolescent patients (14- 18 years old; n = 726) presenting to an urban emergency department (ED) who report violent behavior. Cumulative measures of risk and promotive factors consist of individual characteristics and peer, family, and community influences.

Method

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to test the two models of resilience (using cumulative measures of risk and promotive factors) for violent behavior within a sample of youth reporting violent behavior.

Results

Higher cumulative risk was associated with higher levels of violent behavior. Higher levels of promotive factors were associated with lower levels of violent behavior and moderated the association between risk and violent behaviors.

Conclusion

Our results support the risk-protective model of resiliency and suggest that promotive factors can help reduce the burden of cumulative risk for youth violence.

Keywords: adolescent resiliency, youth violence prevention, violent behavior, risk factors

Introduction

Youth Violence

Youth violence is a significant social and public health problem. Youth who participate in violence are at risk for poor health and social outcomes (Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Centers for Disease Control, 2009). Violence rates peak during the adolescent years, and adolescents disproportionately suffer the consequences of violence, including imprisonment, injury, and death (NAHIC, 2007; CDC, 2009). Members of specific demographic groups, especially males and African Americans, are at particular risk for involvement in serious forms of violence and related negative health and social sequelae (e.g., homicide, incarceration) (Herrenkohl et al., 2000; CDC, 2009). Although death is the most severe consequence of violence, and homicide is the leading cause of death among African American adolescents (CDC, 2009), nonfatal injuries are far more common. In 2007, more than 668,000 10-24 year olds in the United States were treated in emergency departments for injuries caused by violence (CDC, 2009) and the ED is increasingly recognized as a important contact location for youth at risk for future violent injury (Cunningham et al., 2010). In addition, a recent study surveying all youth presenting to an urban emergency department for any reason found that three quarters of adolescents reported recent peer violence (Walton et al., 2009).

Violence involvement during adolescence is a potent risk factor for ongoing violence involvement into young adulthood (Borowsky, Widome, & Resnick, 2008; Dahlberg & Potter, 2001; Herrenkohl et al., 2000). For some youth, violent behavior progresses from physical fighting during early adolescence to more lethal forms, such as violence with a weapon, during later adolescence (Dahlberg & Potter, 2001). In a review of violence and aggression, Loeber and Hay identified trends in the onset and progression of violence for boys (Loeber & Hay, 1997). First, the cumulative onset of aggression generally increases. Second, while the prevalence of physical fighting tends to decrease, the prevalence of serious violence tends to increase. The stability of aggression tends to increase. Loeber and colleagues identified developmental pathways for aggression in males from childhood into adulthood (Loeber et al., 1993). The majority of males in their study were on a trajectory that starts with minor aggression, progressing to physical fighting, and later assaultive violence.

Resiliency

Resiliency theory posits that a variety of factors in childhood and adolescence influence the likelihood of an individual’s participation in behaviors that can either positively or negatively affect their health and well-being. Risk factors are defined as those conditions that are associated with a higher likelihood of negative outcomes (Kazdin, Kraemer, Kessler, Kupfer, & Offord, 1997). Promotive factors operate to enhance healthy development (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Promotive factors play a role in helping youth overcome the negative effects risk pose on development and are important as they help compensate for or protect against the effects of risk on healthy development. Promotive factors may reduce the negative consequences of risk factors through direct effects (compensatory model) or through interaction effects (risk-protective model) (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). The compensatory model of resilience implies that promotive factors can compensate for exposure to risk factors (Garmezy, Masten, & Tellegen, 1984; Masten et al., 1988). The risk-protective model assumes that promotive factors buffer or moderate the negative influence of exposure to risk (Rutter, 1985). In the risk-protective model, promotive factors interact with risks to reduce their negative effect on adolescent outcomes.

Risk and Promotive Factors for Youth Violence

Research on youth violence includes risk and promotive factors present within the individual, peers, family, school, and community that increase or decrease the likelihood that young people will engage in violence (Borowsky et al., 2008; Brookmeyer, Henrich, & Schwab Stone, 2005; Farrington, 2007; Gorman-Smith, Henry, & Tolan, 2004; Resnick et al., 1997; Resnick, Ireland, & Borowsky, 2004; Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997; Valois, MacDonald, Bretous, Fischer, & Drane, 2002). At the individual level, attention and learning problems, antisocial behavior, hopelessness, witnessing violence, violence victimization and alcohol and drug use have been associated with higher levels of aggression and violence (Bolland, 2003; Bolland, McCallum, Lian, Bailey, & Rowan, 2001; Brookmeyer, Fanti, & Henrich, 2006; Cedeno, Elias, Kelly, & Chu, 2010; Ferguson & Meehan, 2010; Resnick et al., 2004). On the other hand, individual level factors such as social skills, school achievement, connections to school, self-efficacy for non-violence and a sense of hope and purpose have been deemed promotive (Borowsky et al., 2008; Cedeno et al., 2010; DuRant, Cadenhead, Pendergrast, Slavens, & Linder, 1994; Farrell, Henry, Schoeny, Bettencourt, & Tolan, 2010; Farrell, Mays et al., 2010; Resnick et al., 2004; Stoddard, McMorris, & Sieving, 2011; Stoddard, Zimmerman, & Bauermeister, 2011).

Parents and family can offer both risk and protection for youth violence (Farrell, Henry et al., 2010; Ferguson & Meehan, 2010; Resnick et al., 2004; Youngblade, Theokas, Schulenberg, Curry, & Huang, 2007; Zimmerman, Steinman, & Rowe, 1998). Family aggression and parent and family attitudes and behaviors that are favorable to violence are a risk factor for youth violence (Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Youngblade et al., 2007); whereas, parental warmth, nurture and support is viewed as promotive (Farrell, Henry et al., 2010; Ferguson & Meehan, 2010; Resnick et al., 2004; Youngblade et al., 2007; Zimmerman et al., 1998). In addition, parental presence and parental monitoring help youth avoid the negative consequences of risk for youth violence (Resnick et al., 2004).

Peer influences increase during adolescence. Peers can offer either negative influence or pro-social (positive) influence. Association with delinquent peers increases an adolescents’ risk of serious delinquency, violence, and involvement in criminal activity (Dahlberg & Potter, 2001; Ferguson & Meehan, 2010; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992). Peer influences that include strong pressures to engage in risk behaviors such as fighting and weapon carrying also place young people at risk on involvement in violence. Involvement with pro-social peers may offer positive support and role modeling for more positive behavior (Resnick et al., 2004). These peers may also help youth overcome the negative effects of risk exposure.

Factors within a community can play a role in youth violence (Bolland et al., 2005; Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Molnar, Cerda, Roberts, & Buka, 2008; Sampson & Morenoff, 1997). Poverty, community disorganization, and the availability of drugs and firearms place youth at risk for involvement in violence (Hawkins et al., 2000; Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Valois, et al., 2002). Youth living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are exposed to more community violence, than their peers in more advantaged neighborhoods. In addition, neighborhoods with a culture and history of adult violence have elevated rates of youth violence (Borowsky, Widome, & Resnick, 2008; Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Valois et al., 2002). Youth living within disadvantaged neighborhoods may experience fewer opportunities for positive relationships and pro-social role models (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, & Aber, 1997), whereas those characterized by cohesion and opportunities for youth to interact with caring adults who reinforce pro-social behaviors appear to confer protection (Sampson & Raudenbush, 1997; Resnick et al., 2004; Resnick et al., 1997).

Our study provides a unique and significant contribution to the current literature on youth violence. First, our sample consisted of high risk youth already engaged in violent behaviors. Second, we examined the effects of cumulative risks and cumulative promotive factors in relation to violent behaviors in this sample of high risk youth. To date, most research on the effect of risk and promotive factors on youth violence has focused on single risk and promotive factors (DuRant et al., 1994; Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Resnick et al., 2004; Valois et al., 2002), or cumulative risk and promotive factors within specific ecologic domains (i.e., individual, family, school) (Van Der Laan, Veenstra, Bogaerts, Verhulst, & Ormel, 2010). Little is known about the cumulative effects of these factors across domains among youth already involved in violence. The purpose of our study was to: 1) examine cumulative risks, cumulative promotive factors, and violent behaviors in sample of adolescents (14- 18 years old) presenting to an urban emergency department (ED) who self-report past year violence, and 2) to test a compensatory model and a risk-protective model of resilience for violent behavior using a hierarchical multiple regression approach. For the compensatory model, we hypothesized that higher cumulative risk would be associated with more violent behavior. We also hypothesized that cumulative promotive factors would be associated with less violent behavior. For the risk-protective model, we hypothesized that promotive factors would reduce the effect of risk after accounting for the main effects of both cumulative risk and promotive factors.

Method

Sample

Seven hundred-twenty-six adolescents (age 14 – 18) participated in the current study. Average age of the participants was 16.77 (SD = 1.33) and approximately half of the sample (56.5%) was female. The sample was predominantly African American (56%) and Caucasian (39%). Seven percent of the sample was Hispanic/Latino. This study is based on baseline self-administered survey data collected as part of randomized control trial (RCT) of an emergency department intervention for alcohol use and violent (aggressive) behaviors (see Cunningham et al. and Walton et al. for more information) (Cunningham et al., 2011; Walton et al., 2010). To be selected to complete the baseline survey (and be enrolled in the study), participants had to endorse both past year aggression and alcohol consumption. Aggression was defined as violent behaviors with peers, with a dating partner, or weapon carriage/use during the past year. Participants were asked ‘In the past 12 months, have you had a drink of beer, wine or liquor more than two to three times’ to measure past year alcohol consumption.

Data collection

Over a one year period (September 2007 to September 2008), adolescent emergency department (ED) patients (age 14-18) who endorsed both past year aggression and any alcohol consumption during a 10 minute computerized, self-administered screening survey were invited to complete a baseline survey. After parental consent (for participants under 18 years old) and participant assent/consent was obtained, participants completed a 20 minute baseline survey. Participants received $20 for their participation in the baseline survey. Study procedures were approved and conducted in compliance with the University of Michigan’s and Hurley Medical Center’s Institutional Review Boards (IRB) for Human Subjects guidelines. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained for this study.

Measures

Violent behavior

Violent behavior was assessed with 7 items from the Conflict Tactics Scale [CTS2] and 3 items from the Add Health survey (Sieving et al., 2001; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Participants indicated how often they had engaged in each behavior during the preceding 3 months: pushed or shoved someone, punched or hit someone with something that could hurt, beat someone up, slammed someone against a wall, slapped someone, kicked someone, used a knife or gun on someone, serious physical fighting, group fighting, and caused someone to need medical care (Sieving et al., 2001; Straus et al., 1996). Response options for each of the violent behavior items included: 0 (never), 1 (1 time), 2 (2 times), 3 (3-5 times), 4 (6-10 times), 5 (11-20 times), and 6 (more than 20 times) (Strauss, 1990. We computed a composite score (sum) across the 10 items (Cronbach’s α = .89). Summing the responses for the ten items yields a violence score with a possible range of 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more violent behavior.

Promotive and risk factors

Promotive and risk factors include individual characteristics, peer influences, parental/familial influences, and community influences. Variables were assigned as either promotive or risk factors based on previous literature assessing factors related to adolescent violence. Six variables were selected for study as promotive factors and eight variables as risk factors. Table 1 reports descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and chronbach’s alpha) and a sample item for each factor. Promotive factors included violence avoidance self-efficacy (ability to avoid violence) (Bosworth & Espelage, 1995), attitudes about violence (Funk, Elliott, Urman, Flores, & Mock, 1999), religious involvement, positive peer behaviors, parental monitoring (Arthur, Hawkins, Pollard, Catalano, & Baglioni, 2002), and living with a parent or guardian. Risk factors included failing grades/school dropout, alcohol use (Chung, Colby, Barnett, & Monti, 2002), marijuana use (Sieving et al., 2001), delinquency (Zimmerman, Salem, & Notaro, 2000), negative peer behavior (Doljanac & Zimmerman, 1998), family conflict (Moos, Insel, & Humphrey, 1974), gang involvement (Zun, Downey, & Rosen, 2005), and exposure to community violence (Richters & Martinez, 1993).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and individual measures for cumulative risk and promotive factors

| Variable (number of items) | M | SD | α | Sample item (type of scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promotive | ||||

| Violence self-efficacy (5) | 2.38 | .85 | .79 | How sure are you that you can stay out of fights? (5-pt Likert scale, 0 = not at all, 4 = extremely). |

| Violence attitudes (6) (reverse coded) |

2.86 | .82 | .75 | If a person hits you, you should hit them back. (5-pt Likert scale, 1 – strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). |

| Religious involvement (1) | 2.09 | 2.10 | NA | In the last year, how often did you take part in religious services or participate in activities offered by a hourse of workship, church, temple, mosque or synagogue? (7-pt Likert scale. 0 = not at all, 6 = more than once a week. |

| Positive peer behavior (4) | 1.54 | .80 | .69 | How many of your friends take part in school clubs, athletics or school council? (5-pt Likert scale, 0 = none, 4 = all). |

| Live with Parent or Guardian (1) | .80 | .40 | NA | Do you live with a parent or guardian? (0 = no, 1 = yes). |

| Parent monitoring (7) | 2.94 | .66 | .78 | When I am not at home, one of them [parents] knows where I am and who I am with. (4-pt Likert scale, 0 = Definitely NO!, 4 = Definitely YES!). |

| Risk | ||||

| Alcohol (1) | 1.69 | .90 | NA | In the past 12 months, how often did you have a drink that containing alcohol? (4-pt Likert scale, 0 = Never, 4 = Daily or almost daily). |

| Marijuana use (1) | 2.47 | 2.39 | NA | In the past 12 months, how many days did you use marijuana? (0 = Never, 6 = Everyday or almost every day). |

| Delinquency (11) | .35 | .46 | .86 | During the past 12 months, how often have you damaged property on purpose? (5-pt Likert scale, 0 = never, 4 = more than once a week). |

| Failing grades/dropped out (1) | 4.83 | 2.33 | NA | What kind of grades do you usually get? |

| Gang involvement (1) | .07 | .26 | NA | Are you in a gang? (0 = no, 1 = yes). |

| Negative peer behavior (8) | 1.17 | .71 | .81 | How many of your friends get into fights? (5-pt Likert scale, 0 = none, 4 = all). |

| Family conflict (2) | 1.66 | .82 | Family members get so angry they throw things. (4-pt Likert scale, 1 = hardly ever, 4 = often). | |

| Exposure to community violence (5) |

.85 | .61 | .70 | In the past 12 months how often has this happened: I saw gangs in my neighborhood? (4-pt Likert scale, 0 = never, 3 = many times). |

Risk and promotive composite indices

Using procedures similar to those by other researchers (Bowen & Flora, 2002; DeWit, Silverman, Goodstadt, & Stoduto, 1995; Newcomb & Felix-Ortiz, 1992; Ostaszewski & Zimmerman, 2006), we created risk and promotive composite factor indices. To create the composite factors, we first standardized the original items. The upper 16% of the distribution of each of item (greater than 1 standard deviation from the mean) was designated as high levels of either a promotive factor or a risk factor, depending on the items, the middle 68% was identified as average levels of promotion or risk, and the lower 16% (less than 1 standard deviation from the mean) identified as low or no promotion or risk. Each participant was given a score of 2 if their score on the variable is equal to or above the upper 16% cut point, a 1 if their score was between the 17th percentile and the 84th percentile (in the middle 68% of the distribution), and a zero if their score was equal to or less than the lower 16% of the distribution. Two items (live with at least parent or guardian and gang involvement) were dichotomous variables. For these items, participants who reported yes were scored a 1 and participants who reported no received a 0. Cumulative indices were computed by summing the promotive and risk factors, respectively, for each individual. The range for the cumulative promotive factor is 0 to 11, and the range for the cumulative risk factors is 0 to 15.

Demographic characteristics

We controlled for the following demographic characteristics: age, sex, race, ethnicity and receipt of public assistance. Participants were asked to report their age in years, and sex (male = 1, female = 0). Participants were asked to report their race (Black or African American = 1, White or Caucasian = 2, Asian = 3, American Indian/Alaskan Native = 4, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander = 5, Unknown/Other = 6) and ethnicity whether they were of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (yes = 1, no = 0, unknown = 2). As a marker of socioeconomic status, participants were asked, “Do your parents, or the most important person raising you, receive public assistance?” Response options were Yes (1) or No (0).

Data analysis plan

Our hypotheses were tested using a four step hierarchical multiple regression analysis with violent behavior as the dependent variable. The first step included demographic variables (age, sex, race, SES), the cumulative risk factor index was entered in the second step, the cumulative promotive factor index was entered in the third step (to test the compensatory model), and the forth step included the cumulative risk by cumulative promotive interaction term (to test the risk-protection model). The cumulative risk and cumulative promotive factor variables were centered prior to creating the multiplicative interaction term (Aiken, West, & Reno, 1991). Prior to our multiple regression analyses, our dependent variable (violent behavior) was assessed for normality.

Results

Descriptive Findings

Overall, participants reported moderate levels of cumulative risk (M = 7.30, Range 0 – 15), moderate levels of cumulative promotive factors (M = 6.06, Range 0 – 11) and moderate levels of violent behavior (M = 5.81, SD = 6.73, skew 1.83, Range 0 - 44). Twenty percent of participants reported no violent behaviors in the past 3 months. Fifty percent of participants reported between 1 and 7 acts of violent behavior, 25% of participants reported between 8 and 19 acts of violence, and 5% reported 20 or more acts of violence in the past 3 months.

Multivariate Models

Violent behavior

Results for each model of violent behavior are shown in Table 2. Model 1 examined the relationship between the demographic covariates and violent behavior. Older age was associated with less violent behavior (b = −.82, p < .001). Violent behavior was not associated with gender, race or SES.

Table 2.

Violence in past 3 months multivariate regression models (n = 726)

| Variable | Model 1 |

Model 2 Risk Model |

Model 3 Risk and Promotive Model1 |

Model 4 Risk/protective Model2 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | b | SE | 95% CI | |

| Gender | .50 | .50 | [−.49, 1.49] | −.67 | .47 | [−1.59, .25] | −.68 | .46 | [−1.59, .23] | −.66 | .46 | [−1.57, .24] |

|

African

American |

.86 | .52 | [−.16, 1.89] | .52 | .47 | [−.41, 1.45] | .63 | .47 | [−.29, 1.55] | .84 | .47 | [−.09, 1.76] |

| Age | −.82*** | .19 | [−1.20, −.45] | −1.05*** | .17 | [−1.40, −.71] | −1.06*** | .17 | [−1.40, −.73] | −1.07*** | .17 | [−1.40, −.73] |

| Public Assistance | .08 | .51 | ]-.93, 1.09] | −.35 | .47 | [−1.27, .57] | −.46 | .47 | [−1.37, .46] | −.46 | .46 | [−1.36, .45] |

| Risk | 1.30*** | .11 | [1.10, 1.51] | 1.08*** | .12 | [.85, 1.32] | 1.01*** | .12 | [.77, 1.24] | |||

| Promotive | −.63*** | .16 | [−.94, −.32] | −.63*** | .16 | [−.94, −.32] | ||||||

|

Risk/Promotive

Interaction |

−.19** | .06 | [−.31, −.08] | |||||||||

| R2 | .03 | .19 | .21 | .22 | ||||||||

| R2 Δ | .17*** | .02*** | .01*** | |||||||||

Note.p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Promotive effects/compensatory or direct effects model.

Indirect effects model

Risk effects

Model 2 examined the effect of cumulative risk on violent behavior through the addition of the cumulative risk factor index. Cumulative risk was related to higher levels of violent behavior (b = 1.30, p < .001) after controlling for demographic characteristics.

Compensatory model

Model 3 tested the compensatory or direct effects of the cumulative promotive factor index by examining the main effect of this factor after the cumulative risk factor index and demographics were entered into the equation. The cumulative promotive factor index was related to less violent behavior (b = −.63, p < .001) after adjusting for cumulative risk and demographic variables.

Risk-protective model

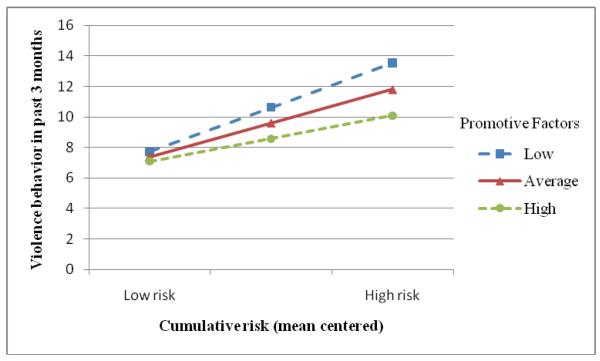

Model 4 tested the protective effects of the cumulative promotive factor index by examining the cumulative risk by cumulative promotive interaction term after the cumulative risk factors index, the cumulative promotive factor index, and demographics were entered into the equation. The cumulative risk by cumulative promotive interaction term was associated with less violent behavior (b = −.19, p < .001). Figure 1 decomposes the interaction effect. The graph depicts the relationship between the risk factors and violent behavior for the mean, and one standard deviation above and below the mean for the cumulative promotive factor index. High risk is associated with higher levels of violent behavior, but violent behaviors are lower for youth reporting more promotive factors. At low levels of risk, however, the promotive factors do not distinguish groups.

Figure 1.

Risk/Protective model: Risk/protective interaction for violent behavior in the past 3 months.

Discussion

This study adds to our understanding of adolescent resiliency in unique and significant ways. First, we examined the relationship between cumulative risk and promotive factors and violent behavior. This strategy is novel in youth violence prevention literature as most research on the effect of risk and promotive factors on youth violence has focused either on single risk and promotive factors (DuRant et al., 1994; Herrenkohl et al., 2000; Resnick et al., 2004; Valois et al., 2002), or cumulative risk and promotive factors within specific ecologic domains (i.e., individual, family, school) (NAHIC, 2007). We know of no studies that have assessed cumulative risk and cumulative promotive factors across multiple ecologic domains focused on adolescent violent behavior. By modeling cumulative risk and promotive factors across multiple domains, we are able to better understand the relationship between risk and promotive factors and violent behavior. Our results suggest that promotive factors can help reduce the burden of cumulative risk for youth violence.

Our findings support the risk-protective factor model of resiliency. We found higher levels of cumulative risk were associated with higher levels of violent behaviors and that higher levels of cumulative promotive factors were associated with less violent behaviors. Yet, after accounting for the main effects of cumulative risks and promotive factors, we also found that cumulative promotive factors moderated the negative effects of cumulative risks on youth violent behavior. Higher levels of cumulative promotive factors appeared to attenuate the relationship between cumulative risks and violent behavior. In the presence of lower levels of cumulative risks, however, level of cumulative promotive factors did not appear related to violent behavior. These results suggest that particularly for adolescents with more risk factors, it is important to examine or assess promotive factors to better understand factors related to violent behavior, and that involvement with promotive factors likely can reduce the negative consequences of risks.

Our model accounted for 22% of the variance in youth violence, and a substantial amount of variance remains unexplained. While our cumulative measures included risk and promotive factors across several ecological domains, we may have missed additional risk and promotive factors that could help explain youth violence. For example, at the individual level, future orientation and a sense of hopefulness for the future have been linked to lower levels of violence involvement for youth living in at-risk environments (Stoddard, McMorris, & Sieving, 2011; Stoddard, Zimmerman, & Bauermeister, 2011); however, we were unable to include these factors in our cumulative index of promotive factors. Future research that includes additional risk and promotive factors may help explain more variation in violent behavior and provide more detailed and nuanced analysis of the effects of risk and promotive factors for violent behavior.

While this is one of the first studies to assess cumulative risk and promotive factors across multiple ecologic domains for adolescent violent behavior, other models of youth violence point to the effect of the accumulation of risk factors over time. For example, Dodge, Greenberg, Malone, et al. (2008) present empirical support for the dynamic cascade model of youth violence in which specific individual, family, and peer risk factors operate sequentially across childhood and early adolescence to increase risk for youth violence. Academic failure, negative peer behavior, and parental monitoring were important risk factors for later violence. This is consistent with factors included in our measure of cumulative risk. However, their model tests only a limited selection of risk factors. A model that is inclusive of additional risk factors across multiple domains and uses a cumulative approach across the lifespan could advance our understanding of factors that place youth at risk for violence. More importantly, a dynamic cascading model that also includes promotive factors across childhood and early adolescence could substantially advance our understanding of resiliency across the lifespan and the prevention of youth violence.

Limitations of this study should be noted. First, our study was based in a city identified as one of the most violent in the U.S. and surpasses both state and national rates for murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assaults (FBI, 2009; Morgan et al., 2009). In addition, our sample was composed of urban youth who presented to an urban emergency department (ED) and reported a history of physical fighting in the past year, thus our findings may not be generalizable to all urban youth. While all youth in this study acknowledged violent behaviors during the past year, variation did exist in more recent violent behavior. Twenty percent of the sample reported no violent behaviors in the past 3 months and half the sample reported a small number of violent behaviors. Of most concern is the remainder of the sample that reported greater involvement with violent behaviors (25% of participants reported between 8 and 19 acts of violence and 5% reported 20 or more acts of violence in the past 3 months). During adolescence, violent and aggressive behaviors are not unusual in general, (e.g., fighting); however, as these behaviors get more severe they become more disruptive for healthy development. These high levels of involvement with violent behaviors place this group of youth at extreme risk of the negative emotional and physical effects of violence (i.e., injury, PTSD, disability, and death). Our results may be especially relevant for youth who may be at particularly high risk for negative outcomes.

Second, our study is based on data collected at a single time point, thus we cannot assume causality. Future research needs to examine these relationships over time to better understand the potential effect of cumulative risks and promotive factors on violent behavior. Third, our cumulative indices for risk and promotive factors were created with all items/sub-scales receiving equal weight. It may be that different risk or promotive factors, or specific ecologic domains, may offer varying levels of risk or protection. The results of our study suggest that a more in-depth examination of this issue may be warranted as our unweighted aggregated approach supported our hypotheses and produced theoretically meaningful results. Future research that includes additional risk and promotive factors may also help explain more variation in violent behavior over time and provide more detailed and nuanced analysis of the effects of risk and promotive factors for violent behavior and other problems behaviors.

Our results suggest that prevention efforts to enhance promotive factors may help youth overcome the debilitating effects of risk. The results suggest, for example, that an ecological perspective that includes promotive influence across social domains may be necessary to overcome the relentless negative influences of risks on healthy adolescent development. Thus, strategies that engage youth in positive social activities with other positive peers may help them envision a more hopeful future for themselves, expose them to positive role models, and increase their chances to overcome the negative consequences of the risks they will inevitably face. Recently a brief intervention (Walton et al., 2010) based on motivational interviewing showed promise for reducing violent behaviors among at risk youth in the ED; this intervention focused both on reducing risk behaviors and increase promotive factors including referrals to community programs (e.g., mentoring, youth activities, psychological services). Such approaches may be appropriate for all youth as a first step, or for youth with low to moderate risk/promotive factors, or high risk and high promotive factors. Alternatively, for youth with higher levels or risk and lower levels of promotive factors, approaches may need to be more intensive. For example, these youth may benefit from multi-session case management or mentoring approaches similar to hospital and ED interventions delivered to youth presenting with violent injury (Cheng, Wright, Markakis, Copeland-Linder, & Menvielle, 2008; Cooper, Eslinger, & Stolley, 2006; Zun, Downey, & Rosen, 2006). Future research is needed to develop and test the efficacy of interventions tailored to levels of cumulative youth risk and promotive factors.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA) grant 014889; Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT00251212. Special thanks are owed to the patients and medical staff at Hurly Medical Center for their support of this project.

Contributor Information

Sarah A. Stoddard, Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health, University of Michigan

Lauren Whiteside, Department of Emergency Medicine and Hurley Medical Center, University of Michigan

Marc A. Zimmerman, Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health, University of Michigan.

Rebecca M. Cunningham, Department of Emergency Medicine and Hurley Medical Center, University of Michigan

Stephen T. Chermack, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan Medical School

Maureen A. Walton, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan Medical School

References

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Pollard JA, Catalano RF, Baglioni A. Measuring risk and protective factors for use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors: the Communities that Care Youth Survey. Evaluation Review. 2002;26(6):575–601. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0202600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland JM. Hopelessness and risk behaviour among adolescents living in high-poverty inner-city neighbourhoods. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26(2):145–158. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland JM, Lian BE, Formichella CM. The origins of hopelessness among inner-city African-American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36:293–305. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8627-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland JM, McCallum DM, Lian B, Bailey CJ, Rowan P. Hopelessness and violence among inner-city youths. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2001;5(4):237–244. doi: 10.1023/a:1013028805470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Widome R, Resnick MD. Young people and violence. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008;Vol. 6:675–684. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth K, Espelage D. Teen conflict survey. Center for Adolescent Studies, Indiana University; Bloomington, IN: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen NK, Flora DB. When is it appropriate to focus on protection in interventions for adolescents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72(4):526–538. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer KA, Fanti KA, Henrich CC. Schools, parents, and youth violence: a multilevel, ecological analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(4):504–514. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer KA, Henrich CC, Schwab Stone M. Adolescents who witness community violence: can parent support and prosocial cognitions protect them from committing violence? Child Development. 2005;76(4):917–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood poverty: Context and consequences for children. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cedeno LA, Elias MJ, Kelly S, Chu BC. School violence, adjustment, and the influence of hope on low income, African American youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(2):213–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC) Youth Violence: Fact Sheet. 2009.

- Cheng TL, Wright JL, Markakis D, Copeland-Linder N, Menvielle E. Randomized trial of a case management program for assault-injured youth: impact on service utilization and risk for reinjury. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2008;24(3):130–136. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181666f72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Monti PM. Alcohol use disorders identification test: factor structure in an adolescent emergency department sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26(2):223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Eslinger DM, Stolley PD. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. The Journal of Trauma. 2006;61(3):534–540. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000236576.81860.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Roahen Harrison S, Resko SM, Stanley R, Zimmerman M, et al. Past-year intentional and unintentional injury among teens treated in an inner-city emergency department. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2011;41:418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg LL, Potter LB. Youth violence: developmental pathways and prevention challenges. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20(Supplement 1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWit DJ, Silverman G, Goodstadt M, Stoduto G. The construction of risk and protective factor indices for adolescent alcohol and other drug use. Journal of Drug Issues. 1995;25:837–863. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS, Group Coduct Problems Prevention Research. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development. 2008;79:1907–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doljanac RF, Zimmerman MA. Psychosocial factors and high-risk sexual behavior: race differences among urban adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;21(5):451–467. doi: 10.1023/a:1018784326191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Cadenhead C, Pendergrast RA, Slavens G, Linder CW. Factors associated with the use of violence among urban black adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(4):612–617. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.4.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Henry DB, Schoeny ME, Bettencourt A, Tolan PH. Normative beliefs and self-efficacy for nonviolence as moderators of peer, school, and parental risk factors for aggression in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(6):800–813. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.517167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Mays S, Bettencourt A, Erwin EH, Vulin-Reynolds M, Allison KW. Environmental influences on fighting versus nonviolent behavior in peer situations: a qualitative study with urban African American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;46(1-2):19–35. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9331-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington D. Origins of violent behavior over the lifespan. In: Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, Waldman ID, editors. The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2007. pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Investigation Federal Bureau of. [retrieved 1/15/2010];Crime in the United States. 2009 http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2008/offenses/violent_crime/index.html.

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a Framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Reviews of Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ, Meehan DC. Saturday night’s alright for fighting: antisocial traits, fighting, and weapons carrying in a large sample of youth. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2010;81(4):293–302. doi: 10.1007/s11126-010-9138-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk JB, Elliott R, Urman ML, Flores GT, Mock RM. The attitudes towards violence scale: a measure for adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14(11):1123–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N, Masten AS, Tellegen A. The study of stress and competence in children: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1984;55(1):97–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: the protective effects of family functioning. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:439–449. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Herrenkohl TI, Farrington DP, Brewer D, Catalano RF, Harachi TW, Cothern L. Preditors of Youth Violence. Juvenile Justice Bulletin (OJJDP) 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Maguin E, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Developmental risk factors for youth violence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26(3):176–186. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Kraemer HC, Kessler RC, Kupfer DJ, Offord DR. Contributions of risk-factor research to developmental psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17(4):375–406. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Hay D. Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48(1):371–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Wung P, Keenan K, Giroux B, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB, et al. Developmental pathways in disruptive child behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5(1):103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Garmezy N, Tellegen A, Pellegrini DS, Larkin K, Larsen A. Competence and stress in school children: the moderating effects of individual and family qualities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1988;29(6):745–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Cerda M, Roberts AL, Buka Effects of neighborhood resources on aggressive and delinquent behaviors among urban youth. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R, Insel P, Humphrey B. Combined preliminary manual for the family, work, and group environment scales. Consulting Psychologists; Palo Alto: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan KO, Morgan S, Boba R. City Crime Rankings 2008-2009: Crime in Metropolitan American. CQ Press; Washington D.C.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- National Adolescent Health Information Center . Fact Sheet on Violence: Adolescents and Young Adults. National Adolescent Health Information Center; San Francisco, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Felix-Ortiz M. Multiple protective and risk factors for drug use and abuse: cross-sectional and prospective findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(2):280–296. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostaszewski K, Zimmerman MA. The effects of cumulative risks and promotive factors on urban adolescent alcohol and other drug use: a longitudinal study of resiliency. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;38(3):237–249. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Ireland M, Borowsky I. Youth violence perpetration: What protects? What predicts? Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(5):424.e421–424.e410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richters JE, Martinez P. The NIMH community violence project: I. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence. Psychiatry. 1993;56:7–21. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;147(6):598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD. Ecological perspectives on the neighborhood context of urban poverty: Past and present. In: Gunn J. Brooks, Duncan GJ, Aber JL., editors. Neighborhood poverty: Policy implications in studying neighborhoods. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, Beuhring T, Resnick MD, Bearinger LH, Shew M, Ireland M, et al. Development of adolescent self-report measures from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, McMorris BJ, Sieving RE. Do social connections and hope matter in predicting early adolescent violence? American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48:247–56. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9387-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Zimmerman MA, Bauermeister JA. Thinking about the future as a way to succeed in the present: A longitudinal study of future orientation and violent behaviors among African American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48:238–46. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9383-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Valois RF, MacDonald JM, Bretous L, Fischer MA, Drane JW. Risk factors and behaviors associated with adolescent violence and aggression. American Journal of Health Behaviour. 2002;26(6):454–464. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.6.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Laan AM, Veenstra R, Bogaerts S, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Serious, minor, and non-delinquents in early adolescence: the impact of cumulative risk and promotive factors: the TRAILS study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38(3):339–351. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9368-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, Bingham CR, Zimmerman MA, Blow FC, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(5):527–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Goldstein AL, Chermack ST, Zimmerman MA, Bingham CR, et al. Rates and correlates of violent behaviors among adolescents treated in an urban emergency department. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngblade LM, Theokas C, Schulenberg J, Curry L, Huang I. Risk and promotive factors in families, schools, and communities: a contextual model of positive youth development in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Supplement 1):S47–S53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Salem DA, Notaro PC. Make Room for Daddy II: The positive effects of fathers’ role in adolescent development. In: Wang MC, Taylor RD, editors. Resilience across Contexts: family, work, culture, and community. Lawrence Erlbaun; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Steinman KJ, Rowe KJ. Violence among urban African American adolescents: the protective effects of parental support. In: Arriaga XB, Oskamp S, editors. Addressing Community Problems: Psychological Research and Interventions. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 78–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zun LS, Downey LV, Rosen J. Who are the young victims of violence? Pediatric Emergency Care. 2005;21(9):568–573. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000177195.45537.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zun LS, Downey LV, Rosen J. The effectiveness of an ED-based violence prevention program. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2006;24(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]