Abstract

Although social support is assumed to be an important factor following loss, the mechanisms by which it influences outcomes are not well understood. This study explored the nature of social support following loss using mixed methods. Widows participated in semistructured interviews 1 and 4 months after loss; a subsample completed 98 days of questionnaires between interviews. Interviews were analyzed using the constant comparative method; themes included the importance of supportive groups and the meaning of support. Social support trajectories were examined using hierarchical linear modeling; perceived social control explained differences in trajectories. Additional interviews were selected by their maximally divergent plots. The findings of these analyses were integrated to contribute a more detailed description of social support in the transition to widowhood.

Keywords: mixed methods, social support, bereavement, longitudinal

The term resilience describes the phenomenon of individuals doing well despite experiencing adversity (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990). Successful adaptation at a particular time is related to the balance between resilience and vulnerability processes, which emerge from the interaction of dynamic and contextualized risk and protective factors. Beyond simply identifying these factors in development, Rutter (1987) called for research investigating the processes and mechanisms that underlie resilience and how these interactions affect continuity and change across the life span.

The purpose of this study was to examine the nature of one protective factor, social support, following the death of a spouse. The changing nature of social support was examined using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) with daily assessment and questionnaire data. HLM analyses allowed for the investigation of questions of individual differences in widows’ perceptions of satisfaction with social support as well as perspective on what the trajectory of social support looks like over the first few months following loss. Qualitative analysis of in-depth interviews also chronicled social support and other factors influencing the experience of widowhood. Semistructured interviews allowed widows to tell the stories of their losses, respond to questions about social support specifically, and highlight experiences they found particularly important. Emergent data analysis kept the inquiry open to widows’ own perspectives on loss, risk and protective factors, and resilience that may not appear in the research literature or theory on the topic. The daily assessment and questionnaire and interview data were analyzed separately, and the results from the HLM and qualitative analyses were integrated in the interpretation phase. Mixed methods studies such as this provide an opportunity to use qualitative and quantitative findings to mutually inform different aspects of the process of inquiry.

Mixed Methods

The term mixed methods has been defined as “research in which the investigator collects and analyzes data, integrates the findings, and draws inferences using both qualitative and quantitative approaches or methods in a single study or a program of inquiry” (Tashakkori & Creswell, 2007, p. 4). Mixed methods are increasingly called for in research designs. The complementary use of mixed methods is less a new technique than it is a new topic of academic discussion (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003). Some of the most well known typologies in developmental theory grew from doing extensive interviews and observations, eventually grouping individuals into data-grounded and emergent categories, and validating the categorizations through standardized methods (Mandara, 2003). Although qualitative and quantitative methods have their roots in different, seemingly irreconcilable, paradigms (see Lincoln & Guba, 1985, for a discussion of axioms of the naturalist–constructivist and positivist paradigms), synthesis of the findings is possible (Healy & Stewart, 1991) and may play a key role in moving forward an understanding of resilience in later life. Epistemological debates aside, mixed methods can be invaluable tools for deepening understanding of factors influencing development as complex as resilience in the experience of widowhood.

Empirically derived instruments and assessments are important for comparing across samples and generalizing to a population. Standardized questionnaires and situations, however, may by their very nature limit the phenomena under study (Neimeyer & Hogan, 2001). Unstructured in-depth interviews, in contrast, allow participants to steer the interviews to topics relevant to their experiences rather than fitting their experiences into forced-choice responses. This exploratory focus, characteristic of many qualitative approaches, can identify other aspects of resilience and weigh the meaning of experiences through context that may not appear in theory, research, or clinical practice. As such, qualitative methods have increasingly received attention in bereavement research (Stroebe, Hansson, Stroebe, & Schut, 2001).

Relying on either methodology in isolation can limit the breadth of data, ideas, and even people available to be studied. Using quantitative and qualitative methods provides groundwork for triangulation. By using mixed methods to examine a phenomenon, a researcher gains perspective and nuance. Mixed methods studies add unique contributions to the field by investigating development at the interacting levels of the particular, general, and theoretical. This conceptualization of research bears striking resemblance to Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) ecological systems model of development and thus seems particularly appropriate for studying the multiple bidirectional systems that influence development. The results of the proposed research will provide an increasingly detailed model of social support and other protective factors in later life and will help inform intervention efforts in aging populations.

The mixed methods approach is a unique contribution of this project. By using mixed methods, the proposed analyses can contribute to an increasingly three-dimensional picture of social support and its role in resilience following loss in later life. Exploring social support via longitudinal methods can provide perspective on how perceptions of this resource change over time. This approach is one way to understand the complex and dynamic nature of protective mechanisms. The value that qualitative methods bring lies in the detail and context. In their interviews, widows spoke in their own words about their experiences and understandings. These rich data thicken and nuance quantitative findings about theorized protective factors such as social support in the context of bereavement. In this study, daily assessment and questionnaire and interview data were analyzed separately, and the results of HLM and constant comparative analyses were integrated at the data interpretation phase.

Present Study

Newman, Ridenour, Newman, and DeMarco (2003) encouraged researchers to think beyond research questions to the underlying purposes of their research. We use the term objective to describe the driving interest of each component of the study. The first objective of this research was to explore widows’ experiences of loss and social support. Semi-structured interviews after the loss and again 3 months later allowed widows to tell the stories of their losses, respond to questions of social support specifically, and highlight the experiences they found particularly important. Using emergent data analysis as outlined by the constant comparative method, the research team explored themes that emerged from the data rather than approaching the interviews with a set of hypotheses to test. This data-grounded analysis kept the study open to influences and perspective on loss and protective factors, such as social support, that may not appear in the research literature or theory on the topic.

The second objective of this study was to understand day-to-day appraisals of social support during the transition into widowhood. Plots of satisfaction with support were examined for each widow. Characteristics of these trajectories (i.e., intercepts, slopes, and individual differences in these parameters) of social support were then explored using HLM techniques (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1987) with daily assessment and questionnaire data. HLM analyses allow for the investigation of questions of individual differences and intraindividual change in widows’ perceptions of quality and quantity of social support. A benefit of using HLM is that it allows for an examination of the relationship between daily measures of social support and the global measures traditionally used to assess social support.

The third objective of this study was to use the quantitative and qualitative findings to inform each other. Daily assessment and questionnaire and interview data were analyzed separately but are presented in a more blended form in this article to aid presentation. The plots and the results of the HLM and constant comparative analyses were integrated at the data interpretation phase. As part of the integration, four unusual and interesting trajectories were selected for qualitative examination. Using the two methodological approaches in tandem can flesh out detail, give meaning, and add depth to the general notion of social support as a protective factor.

Preliminary work: qualitative analysis of subsample of widowhood interviews

To identify important risk and protective mechanisms grounded in widows’ own experience, a sample of 11 initial interviews1 from the Notre Dame Adjustment to Widowhood Study were analyzed using the constant comparative method. The focus of inquiry of this study was to better understand older widows’ experiences of loss and widowhood. A goal of this study was to use an emergent coding scheme to describe the helpful and stressful factors and processes that the widows themselves identified in the interviews.

The adjustment to widowhood is a complex experience. Many of the themes identified in the interviews were similar to those documented in the research on resilience. The social support themes were particularly interesting. Widows’ descriptions of their sources of social support (families, friends, neighbors) mirrored the literature on this topic (Sarason, Sarason, & Pierce, 1990). Their descriptions of the nature and quality of social support, however, provided novel perspective on this protective mechanism. For example, an interesting finding was that none of the 11 widows was interested in participating in a grief support group. Rather than joining new bereavement-focused groups, many of the women relied on their long-term networks in activity-based groups, such as card clubs and church organizations, for support. These findings contextualize and nuance the notion of social support as a protective mechanism. Further development and confirmation of these findings was needed and pursued because they represented only the early experiences of 11 of the widows. Additionally, the larger mixed methods study included quantitative data on social support over time to contribute useful insight into the changing nature of social support following loss.

Methods

Notre Dame Adjustment to Widowhood Study

Participants in the current study were part of the larger Notre Dame Adjustment to Widowhood Study. Widows were identified through death notices published in local newspapers of a midsized northern Indiana city and surrounding areas; letters describing the purpose and requirements of the study were sent approximately 7 days after loss. Widows were recruited during 1999 and 2001. The women were informed that a researcher would telephone them requesting participation in an investigation of adaptation to conjugal loss that would explore various aspects of stress, personality, social support, and mental and physical health. Of the 266 women for whom full addresses were available, 211 (79%) engaged in correspondence, including 19 who declined before the phone call was made, 121 who declined or had family members decline for them during the phone calls (most offering “just not interested” as a reason), and 71 women who did express interest. Of those who expressed interest, several cancelled prior to the initial interviews. Therefore, 58 widows completed the initial interviews.

The interview and daily assessment data for this project were collected as part of a larger longitudinal study of adjustment to widowhood (see Bisconti, Bergeman, & Boker, 2006). The full sample available for quantitative analysis was composed of 58 widows, who were randomly assigned to a target or control group. Widows participated in initial and follow-up interviews and completed self-report questionnaires at the initial and second interviews, as well as additional questionnaires in the 5 years following the loss. In addition to the interview and questionnaire data, the 28 women in the target widowed group were asked to keep daily diaries of their stress and emotions. Of these 28, 20 completed daily assessments of their satisfaction with social support; the remaining 8 were not asked to complete reports of daily satisfaction with social support. These daily assessments lasted for 98 days. To assess whether the experience of reporting one’s feelings on a daily basis enhanced health and well-being outcomes, the widowed control group did not participate in the daily assessments.

Subsample Used in the Present Study

Qualitative data for the present study drew 21 widows from the full sample of widows. The emergent nature of qualitative analyses made it difficult to specify, a priori, how many additional interviews would be needed. Strauss and Corbin (1998) discussed the idea of theoretical saturation. In this approach, researchers continue to analyze new data until the categories are saturated, that is, when no new properties or dimensions emerge. Although it is possible to continually add detail and description, at the point of theoretical saturation, new information does not add much in terms of explanation (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). As a research team, we decided to select transcripts to achieve maximum variation and continue bringing in new transcripts until we had reached a point of theoretical saturation in the main themes. Regarding the social support categories, we believe we reached theoretical saturation. Three additional interviews (2014, 2017, and 2019) were listened to, unitized, and discussed but were not integrated, because we found them to provide additional instances of existing social support themes but not new kinds of information.

In previous quantitative analyses from this data set, 11 widows were dropped from the analyses. These were excluded because they dropped out of the study some time after the initial interviews or because they became involved in romantic relationships between the first and second interviews. Given the qualitative component of the current study, these kinds of participants are of interest for their contribution toward maximum variation. To achieve maximum variation in the interview component of the analyses, special attention was paid to (a) the length of marriage, (b) age, (c) race, (d) the expectedness of the spouse’s death, and (e) marital history. In the integration phase, four additional interviews were selected and explored on the basis of their plotted trajectories. The selected interviews should “represent the range of experience of the phenomenon” (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994, p. 57) of older widows’ experiences of loss and widowhood.

The widows used in qualitative analyses were diverse in terms of age and length of marriage and included one African American woman (Charlotte2) and one woman who began a new romantic relationship (Christine). Patricia discontinued completing daily assessments after 5.5 weeks of the 98-day study but was brought in during the integration phase and so was included in both the quantitative and qualitative analyses.

Quantitative data for this study drew from the target widowed group, which completed initial and follow-up interviews, questionnaires, and 98 days of daily assessments. Because one objective of this study was to examine the trajectories of social support, the daily assessment data were of particular interest here. Twenty widows completed daily assessments of social support that were used in the quantitative analyses.

The design of the current mixed methods study was complex. Therefore, an overview of the sampling strategy is provided to clarify the processes that guided the project (Teddlie & Wu, 2007). It may be useful to first differentiate between the design of the data collected and that of the data analyzed. Both the quantitative and qualitative data were collected as part of a larger study, which was not designed to be qualitative or mixed in its focus (see the description of data collection in “Procedure”). The quantitative daily survey data (Objective 1) used in the current study maintained the probability sampling of the larger project; that is, widows who were randomly assigned to a daily survey group were the focus of these analyses. The qualitative interview data (Objective 2) were purposively selected from the pool of available interviews to provide a maximally varied sample on characteristics of interest. For the integration phase (Objective 3) of the study, four additional interviews were selected and analyzed on the basis of the plots of their daily survey data. The overall sampling strategy was sequential, that is, using the findings of Objectives 1 and 2 to direct the sampling for Objective 3.

Procedure

Qualitative data

Ten additional initial interviews from the sample were added to the sample of 11 interviews used in the initial qualitative analysis. The preliminary study included only first interviews. Retaining these initial interviews and selecting other interviews for maximum variation until theoretical saturation was reached permitted the further investigation of themes in the experience of widowhood. Diversity is desirable in qualitative studies because “any common patterns that emerge from great variation are of particular interest and great value in capturing the core experiences and central, shared dimensions of a setting or phenomenon” (Patton, 2001, p. 235).

It is important to note that the qualitative findings in this study were the products of only initial interviews. These interviews examined provided rich and detailed data, but they were collected prior to the daily assessment data on which the quantitative analyses are based. The initial interviews were, for the most part, retrospective. Widows recounted their marriage and life histories, focusing primarily on the events surrounding the deaths of their husbands. They were also asked about their current functioning, stressors, and supports, and some discussed their future plans and expectations about what their lives would be like.

The follow-up interviews occurred after the completion of the daily assessments. These later interviews could provide a complementary longitudinal qualitative component to the 98 days of social support data used in the quantitative analyses. This would allow the research team to examine changes in how the widows talked about their losses and lives. In this way, the qualitative interviews would bracket the quantitative data in this study, occurring prior to the questionnaire and following the daily assessments. The addition of these second interviews was considered for this project. Overall, follow-up interviews tended to be shorter and to contain similar information to the initial interviews, often retelling the stories of the deaths. It may be that explorations of grief, especially early after a loss (4 months afterward in this case), will inevitably point back to the trigger (the death). In a few cases, later interviews provided widows’ reflections on the transition and the period between the interviews. Ideally, the follow-up interviews would have aided the dialog and synthesis between the quantitative and qualitative aspects of this study. In the larger Notre Dame Adjustment to Widowhood Study, the initial and follow-up interviews were included more as methods for maintaining the sample than as sources of data themselves and so were not designed to explore change. As a research team, we concluded that the follow-up interviews are a potentially interesting source of information for future studies but would not be universally included in the present study because of the different experiences they represent. Two follow-up interviews, however, were selected in the integration component of the study because of their informative depictions of change and widows’ extreme status. These are discussed in the integration section of the results.

Quantitative data

Social support was assessed in the target widowed group using items from both the questionnaire (on average, 1 month after loss) and the daily assessment data (98 days). Social control measured the extent to which a widow generally felt that she had control over her social interactions and support (Reid & Ziegler, 1981). Sample items included “I find that if I ask my family (or friends) to visit me, they come” and “I can rarely find people who will listen closely to me.” Cronbach’s α coefficient was .82. Daily satisfaction with social support was measured in the daily assessment data, which included four items on social support, tapping daily perceptions of and satisfaction with support. Participants respond to statements such as “I was satisfied with the number of family members I spoke to today” (quantity of family support) and “I was satisfied with the type of help I received from family today” (quality of family support) by endorsing the statements as completely true, quite true, a little true, or not at all true. Corresponding items were included for the quantity and quality of daily friend support.

Results and Discussion

Objective 1: Qualitatively Identifying Core Themes and the Meaning of Social Support in Widowhood

In preparation for this project, an initial sample of 11 of the widowhood interviews was analyzed using the constant comparative method. Ten additional interviews were included in the subsequent qualitative analyses. The analysis of the widowhood interviews followed the constant comparative method as outlined by Lincoln and Guba (1985) and Maykut and Morehouse (1994), guided by the work of Strauss and Corbin (1990, 1998).

Working with another member of the research team, we separated the transcribed interviews into units of meaning. Constantly comparing these units with each other, these chunks of data were grouped into emergent categories. A rule for inclusion and exclusion was written for each category, describing the essence of the units in that category. Eventually in this iterative process, the rules were developed into propositional statements that served as tentative findings for a specific theme. The research team then synthesized the propositional statements into an overall understanding of the phenomena. To build rigor into the work, the research team consulted with peer debriefers.

The nature of the widows’ social support was of particular interest in the interviews. Initially, the interviewers used the social convoy model (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980), which involved showing the women concentric circles and asking them to name and rank the support they received. This technique was used for both emotional and instrumental support. Disappointingly, the activity neither generated much new nor thickened information about the widows’ support systems. Instead, much of what we know about the social support received came from widows’ mentions of supportive people during other parts of the interviews. The social support themes that emerged in some ways echo the social support literature. The themes also point to experiences that are rarely discussed in previous research but may be particularly important for understanding social support following loss. The themes presented here overview the theory-supporting findings and highlight the more novel contributions.

Support before the death

Prior to the death, help came primarily from family members in the form of instrumental support. Neighbors also emerged as important sources of instrumental help. Social support before the death of the husband was discussed primarily in terms of doing things to help the widow. Families provided instrumental support prior to the death by doing maintenance, providing transportation, assisting with caregiving, and helping explain medical procedures. Neighbors supported widows prior to their losses by doing things around the house and helping care for their husbands in emergencies.

Interestingly, there were few mentions of emotional support prior to the death, in stark contrast to the outpouring of emotional support described afterward. This may be related to widows’ needs at the time. Many of the widows with ill husbands spent their days caring for or comforting them. These widows needed help with caregiving, and this help allowed the women to continue doing so. The expectedness of the death is likely important here; for widows for whom the deaths were completely unexpected, loss-focused emotional support prior to the deaths would have been inappropriate. Within the group of widows whose husbands died following bouts of illness and long stays in the hospital, several mentioned not wanting to see the clues, which made the deaths seem more unexpected. If widows were unaware or disbelieving of clues, they may not have wanted emotional comfort from others. Supporters may also have been unaware of or reluctant to see the upcoming deaths or may not have wanted to bring up the subject with the widows.

The simple presence of family members (participating in caregiving, taking care of things around the house, staying with the widows—part of the “being there” theme not presented here) may have provided the comfort they needed at the time. Little information is available to confirm these possibilities, but the lack of description here is clearly different than the impressive expression of emotional support following the deaths.

Support after the death

Support after the death was both instrumental and emotional. Families provided instrumental support after the deaths by offering money, helping with chores and maintenance, serving as liaisons, and simply being available as needs arose. Neighbors provided on-call support after the deaths: checking in on the widows, being emergency contacts, even taking care of things before the widows asked for help. Emotional support was clearly evident after the deaths. Families provided emotional support after the deaths through their company, check-in phone calls, and affection.

Interestingly, none of the widows mentioned wanting to join bereavement support groups; either it was not something they needed, or they already had support in place. This disinterest in bereavement-specific support groups was a surprising finding. Support groups are not central to social support theory but are part of the resources frequently offered to widows. Instead, some widows described other informal supportive groups. Widows mentioned that long-standing friends provided emotional support by checking in on and spending time with them. The widows interviewed were often involved in long-term activity-based groups (e.g., church groups, card clubs). These groups provided opportunities for both enjoyment and support. Widowed friends and relatives were also mentioned as sources of support through their company, their advice and normalizing, and their example.

Nancy contrasted her experience of existing support with that of her sister’s, whose husband died when she was young. Nancy explained, “She really had no support system. And she didn’t belong to any clubs or anything, had never gone to church, and as her children grew up, they became her whole life.” She recalled that she had read articles that instructed widows, “Don’t stay at home, go out with friends, do this …” but explained that if someone had told her sister to “get out and meet people … start going to church and meet people … she couldn’t have done it.” Nancy repeated that she felt fortunate that her supportive group of church women was already in place before her husband died.

Nancy’s comments ground and shape our understanding of why some widows are not interested in formal support groups. Like many of the widows, she had a long-standing supportive network already in place. Nancy’s description of her sister’s experience suggests that some widows are unwilling or unable to seek new sources of support following their husbands’ deaths. Although Nancy’s sister was young when she became a widow, this situation may be equally or more common in older widows, who may have fewer opportunities for or less interest in meeting new people.

As Ingrid pointed out, she and her friends were “there for each other.” This statement might be a key to the importance of informal supportive groups for the widows interviewed. The long-standing card clubs and church groups were not designed as interventions for any particular widow but allowed the women to enjoy and support one another. These informal groups, perhaps even more than the interactions with family, friends, and neighbors, may provide widows with the opportunity to receive support but not to be the sole target of it. By being part of groups, the women can support one another. Recent research suggests that giving support may be as or more important than receiving it. Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, and Smith (2003) found decreased rates of mortality in individuals who reported providing instrumental support to relatives, friends, and neighbors. When providing support was accounted for in their analyses, receiving support had no effect on mortality. Being there for one another may be an important piece linking social support to well-being beyond reciprocity effects.

Comments on support overall

Most widows were satisfied with the support they received. Fortunate, blessed, lifted up, and moved were some of the terms widows used to describe their support. Some were so impressed by the experience that they said they would be more compassionate when others lost loved ones. Although satisfied with their support broadly, some widows provided nuance suggesting that social support is a complex experience. The interviews did not provide much information about the quantity or frequency of support over time, though it was a concern for some of the widows (Betsy in particular). Widows were able to detect mismatches between the support available and their needs, as in situations in which more support was offered than they wanted or when they felt uncomfortable using the support offered. Several widows (Josephine, Dorothy) noted that in interactions with their children, if they did not follow the advice offered, the support may be removed. Others were reluctant to seek support. Some preferred to do things for themselves. For other widows, they were concerned about overburdening their supporters when they were also grieving.

Several widows were acutely aware of the difference between useful and not useful support. Betsy noted that the most helpful support was a combination of good listening and checking in on her:

I think it’s a combination of both, of somebody just listening to you when you’re trying to ramble all the time, just going on and on and then someone calling and saying, “Hey … how about going to lunch?” or something like that. I think that helps a lot. … I think it’s a combination of both, of having someone calling you or even sending you a card, to let you know that, yeah, that they’re thinking of you.

She also noted the importance of maintaining contact; that is, support was just as important later on as it was during the time surrounding the death and funeral:

I think a lot of times people have a tendency after a short time, they just, you know, you go on with your own business, which is normal and you kind of forget the person. That’s just like when you come out of the hospital … everybody is there [and] about two weeks later you’re sitting at home thinking, gee wouldn’t it be nice if somebody came to see you.

Ingrid shared her thoughts on offers of support, that they need to feel genuine for someone to accept them:

This is what is important, I think, to make people feel it’s possible to feel comfortable calling them. Some people say, “call me if you need anything,” well, you know very well that [it is not genuine, that it’s just words] … but … [if] somebody shows some interest, like she comes in to see me, voluntarily … I wouldn’t feel uncomfortable asking … for her help.

Together, she and the interviewer discussed the importance of people who offer help making themselves available in such a way that the person in need would feel comfortable asking for help. Without this authenticity, the offer seems as if it is just empty words.

Objective 2: Quantitatively Examining Trajectories of Social Support Following the Loss of a Spouse

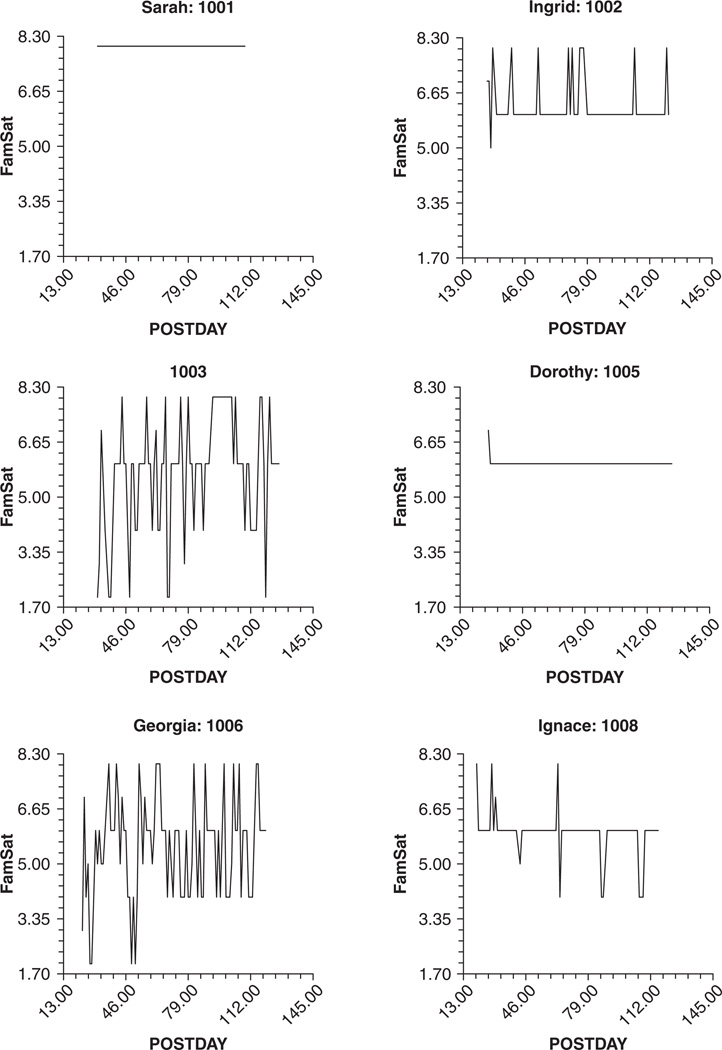

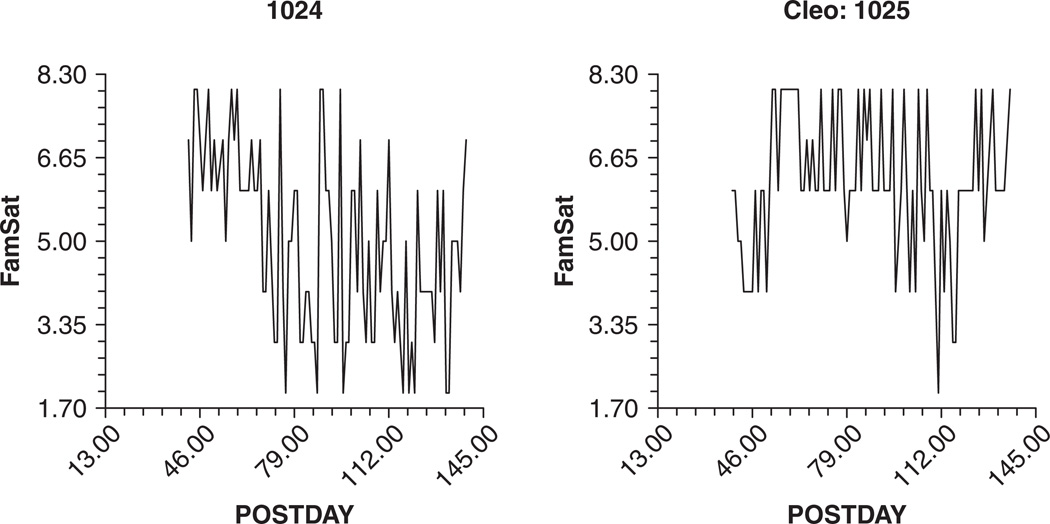

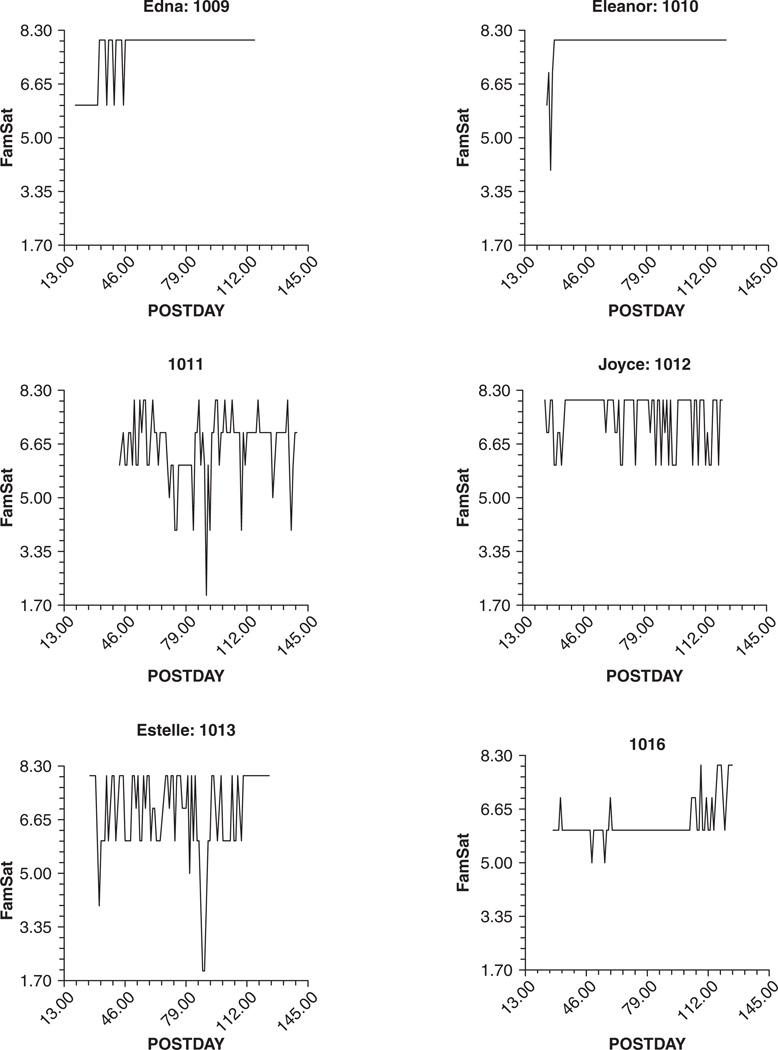

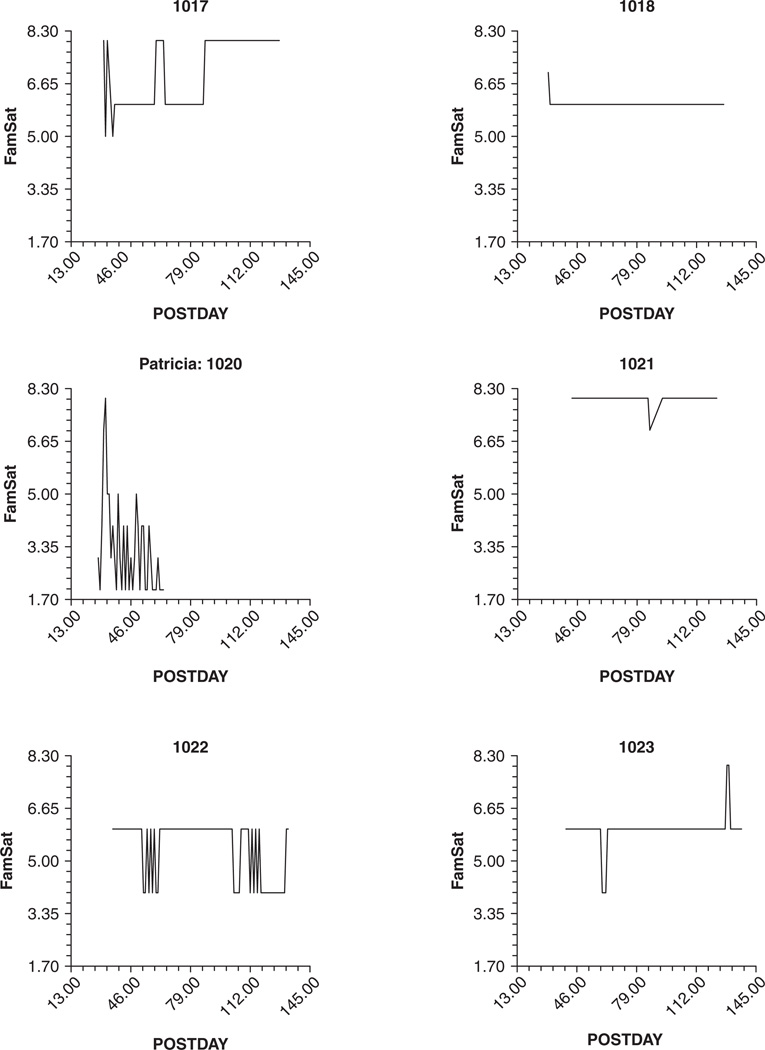

As in the qualitative analyses, an exploratory focus also directed the quantitative component of this study. The second objective of the proposed research was to examine the trajectories of satisfaction with social support in the 4 months following the death of a husband through a series of descriptive quantitative analyses. The widows (n = 20) involved in these analyses were from the target widowed group (see Tables 1 and 2). First, individual trajectories were plotted to produce a visual picture of any change in satisfaction with social support. Individual trajectories are displayed in Figures 1 to 4 for satisfaction with family support; trajectories for daily satisfaction with friend support were similar (r = .71, p < .001). Visually, three profiles appeared: one in which widows were highly stable and for the most part satisfied with their support (e.g., Sarah, Dorothy, 1021), another in which widows showed considerable day-to-day variability in satisfaction with support and reported more moderate levels of satisfaction with support (e.g., 1003, Georgia, 1022), and a third in which widows displayed day-to-day variability and possible declining trend in satisfaction with support over time (e.g., 1011, 1024, Cleo).

Table 1.

Satisfaction With Family Support Results

| b | SE | t (dfa) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FamilySat = β0 + β1Monthst + et | |||

| β0 = γ00 + γ01PerControlUncentered + u0 | |||

| β1 = γ10 + γ11PerControlUncentered + u1 | |||

| Intercept (β0) | 1.46 | 2.08 | 0.70 (18) |

| PerControlUncentered (γ01) | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.34 (18.1) |

| Slope (β1) | 3.21 | 0.80 | 4.01* (14.8) |

| PerControlUncentered (γ11) | −0.08 | 0.02 | −4.00* (15) |

| FamilySat = β0 + β1Monthst + et | |||

| β0 = γ00 + γ01PerControlMeanCentered + u0 | |||

| β1 = γ10 + γ11PerControlMeanCentered + u1 | |||

| Intercept (β0) | 6.32 | 0.21 | 30.79* (17.6) |

| PerControlMeanCentered (γ01) | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.34 (18.1) |

| Slope (β1) | < −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.05 (14) |

| PerControlMeanCentered (γ11) | −0.08 | < 0.02 | −4.00* (15) |

| FamilySat = β0 + β1Monthst + et | |||

| β0 = γ00 + γ01PerControl25%Centered + u0 | |||

| β1 = γ10 + γ11PerControl25%Centered + u1 | |||

| Intercept (β0) | 6.03 | 0.24 | 25.42* (17) |

| PerControl25%Centered (γ01) | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.34 (18) |

| Slope (β1) | 0.19 | 0.09 | 2.13 (13.3) |

| PerControl25%Centered (γ11) | −0.08 | 0.02 | −4.00* (15) |

| FamilySat = β0 + β1Monthst + et | |||

| β0 = γ00 + γ01PerControl75%Centered + u0 | |||

| β1 = γ10 + γ11PerControl75%Centered + u1 | |||

| Intercept (β0) | 6.67 | 0.26 | 26.09* (18.5) |

| PerControl75%Centered (γ01) | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.34 (18.1) |

| Slope (β1) | −0.23 | 0.10 | −2.34 (15.5) |

| PerControl75%Centered (γ11) | < −0.08 | < 0.02 | −4.00* (15) |

Note: Months represent months after death. Separate analyses were conducted for five different Level 2 predictors of satisfaction with family support (not reported here). A family-wise Bonferroni correction can be used to control the error rate, setting the α level at a more conservative .01.

There is no general way to calculate exact degrees of freedom in mixed models. The Satterthwaite correction provides an approximation to a t or F distribution. Degrees of freedom can be fractional and depend on more than sample size.

p < .05.

Table 2.

Satisfaction With Friend Support Results

| b | SE | t(dfa) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FriendSat = β0 + β1Monthst + et | |||

| β0 = γ00 + γ01PerControlUncentered + u0 | |||

| β1 = γ10 + γ11PerControlUncentered + u1 | |||

| Intercept (β0) | −0.12 | 2.61 | −0.04 (18) |

| PerControl (γ01) | 0.16 | 0.07 | 2.35 (18.1) |

| Slope (β1) | 3.61 | 0.72 | 5.05* (21.8) |

| PerControl (γ11) | −0.09 | 0.02 | −4.95* (22.1) |

| FriendSat = β0 + β1Monthst + et | |||

| β0 = γ00 + γ01PerControlMeanCentered + u0 | |||

| β1 = γ10 + γ11PerControlMeanCentered + u1 | |||

| Intercept (β0) | 6.00 | 0.26 | 23.38* (17.6) |

| PerControlMeanCentered (γ01) | 0.16 | 0.07 | 2.36 (18.1) |

| Slope (β1) | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.87 (20.7) |

| PerControlMeanCentered (γ11) | −0.09 | 0.02 | −4.95* (22.1) |

| FriendSat = β0 + β1Monthst + et | |||

| β0 = γ00 + γ01PerControl25%Centered + u0 | |||

| β1 = γ10 + γ11PerControl25%Centered + u1 | |||

| Intercept (β0) | 5.63 | 0.30 | 18.90* (17.4) |

| PerControl25%Centered (γ01) | 0.16 | 0.07 | 2.36 (18.1) |

| Slope (β1) | 0.27 | 0.08 | 3.49* (19.8) |

| PerControl25%Centered (γ11) | −0.09 | 0.02 | −4.95* (22.1) |

| FriendSat = β0 + β1Monthst + et | |||

| β0 = γ00 + γ01PerControl75%Centered + u0 | |||

| β1 = γ10 + γ11PerControl75%Centered + u1 | |||

| Intercept (β0) | 6.43 | 0.32 | 20.27* (18.1) |

| PerControl75%Centered (γ01) | 0.16 | 0.07 | 2.36 (18.1) |

| Slope (β1) | −0.19 | 0.09 | −2.17 (22.6) |

| PerControl75%Centered (γ11) | −0.09 | 0.02 | −4.95* (22.1) |

Note: Months represent months after death. Separate analyses were conducted for five different Level 2 predictors of satisfaction with family support (not reported here). A family-wise Bonferroni correction can be used to control the error rate, setting the α level at a more conservative .01.

There is no general way to calculate exact degrees of freedom in mixed models. The Satterthwaite correction provides an approximation to a t or F distribution. Degrees of freedom can be fractional and depend on more than sample size.

p < .05.

Figure 1.

Plots for Widows 1001 to 1008

Note: The x-axis shows days after death and the y-axis shows the level of satisfaction with family support.

Figure 4.

Plots for Widows 1024 and 1025

Note: The x-axis shows days after death and the y-axis shows the level of satisfaction with family support.

HLM (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1987) was used to statistically examine the trajectories of social support. HLM is a two-stage technique for analyzing change. The Level 1 models from the first stage of HLM analysis were used to address questions of intraindividual change in social support (i.e., how does satisfaction with social support change across the 4 months following the loss of a spouse?). Time was scaled as months after death. Parallel Level 1 analyses were also examined for satisfaction with friend support. Analyses were conducted using SAS PROC MIXED, using a Satterthwaite correction for sample size.

Significant mean intercepts indicated that widows reported rather high initial satisfaction with family, b = 6.30, SE = 0.24, t(19.1) = 26.36, p < .01, and friend, b = 5.97, SE = 0.31, t(19) = 19.57, p < .01, support. Nonsignificant linear slopes were found for satisfaction with family, b = 0.01, SE = 0.10, t(13.3) = 0.10, p = .92, and friend, b = 0.08, SE = 0.10, t(20.2) = 0.85, p = .41, support, providing little support for any average linear change, positive or negative, in satisfaction with support.

Next, individual differences in the component parts of the trajectories were examined. These Level 2 analyses allowed for examinations of questions of interindividual differences in intraindividual change in social support. Parallel analyses were conducted for satisfaction with family and friend support (see Tables 1 and 2). One global measure, perceived social control, was useful in explaining individual differences in the trajectories of satisfaction with support.3 Interestingly, when uncentered perceived social control was added as a Level 2 predictor, the linear slope for satisfaction with support (both family and friend) became significant.

To aid interpretation, perceived control analyses were conducted using several different centerings (Curran, Bauer, & Willoughby, 2004). Uncentered, this model gives the intercept and slope when perceived social control is 0 (Singer & Willett, 2003). None of the widows, however, reported their social control to be 0 at the 1-month interview. The lowest reported perceived control was 29 (M = 38.29, SD = 3.82). Consistent with the exploratory focus of this study, other, more interpretable centerings were pursued. Mean centering produces fitted values for the intercept and mean for a widow with the average level of perceived social control. When mean centered, perceived control predicted differences in the intercept and slope of satisfaction with support, and the main effect of time was not detectable. Given our interest in the range of experiences of social support in widowhood, models for high (75%) and low (25%) perceived social control were also examined. Centering perceived control at the 25th and 75th percentiles resulted in perceived control predicting differences in the intercept and slope, as well as a main effect for time (with the exception of 25% family support).

When perceived social control (uncentered, 25%, and 75%) was included, it interacted with time such that a small but significant average slope in satisfaction was detectable; when control was not included, the trend in satisfaction was not distinguishable. Perceived social control also explained differences in the intercept in satisfaction with support. The significant intercept term suggests that widows differed in their initial satisfaction with support and that perceived social control predicted these differences. Widows who perceived themselves as possessing more social control reported higher initial satisfaction with social support. The interaction between time and social control, however, indicated that high social control is not uniformly beneficial. Widows who reported higher levels of social control at the time of the initial interview actually showed decreased satisfaction in family and friend support over time.

In summary, considerable between-person differences in satisfaction with support over time were present. Some widows reported consistently high levels of satisfaction, whereas others reported substantial day-to-day fluctuation. Most of the widows reported high to moderate levels of satisfaction with social support. It is interesting to note that few global measures explained differences in satisfaction with social support. The contributions of perceived social control as a Level 2 predictor were not hypothesized but are potentially interesting. Perceived social control as a predictor of initial satisfaction is not surprising.

In this sample, an outpouring of offers of support and help was common in the time immediately following the death (see the discussion of qualitative findings). Those widows who believed that they had control over their support, meaning that they could access the support they wanted, were satisfied with the support they received at the time of the initial interviews. As time passed following the deaths, willing and available support may not have been as abundant. Supporters may have returned to their own commitments following the “crisis” period of the losses and funerals. Perhaps those widows who believed that they had high levels of control over their social interactions became frustrated or dissatisfied with support as time passed.

The significant findings for perceived social control prompted further exploration. It is interesting to note that in follow-up analyses, perceived social control as a Level 2 predictor did not predict trajectories of positive affect, control, emotional ties, depression, anxiety, or grief. This suggests that perceived social control is unique in its explanation of trends in satisfaction with support but was unrelated to other mental health variables. Change in perceived social control itself was also examined. Eleven widows reported significant declines in their perceived social control between the initial and follow-up interviews (t = 5.32, df =10, p < .01). The mean decline in this group was 3.16 points (SD = 1.97). Four widows reported increases in social control during this period, but these changes were not statistically significant (t = 2.47, df = 3, p = .09). The mean increase in this group was 3.25 points (SD = 2.63). Five widows reported the same levels of social control at both the first and second interviews.

Together, the plots and analyses informed each other. In particular, the quantitative analyses and plots pointed to the complexity of satisfaction with support over the period following loss. These quantitative data provided useful information for the integration piece and were the impetus for extensions that are discussed there.

Objective 3: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Data to Understand the Complexity of Social Support

The plots and results of the HLM and constant comparative analyses were integrated at the interpretation phase of the research, permitting us to carefully and thoroughly analyze the data separately and merge the quantitative and qualitative findings together when interpreting the data. Of particular importance here was to also avoid “qualifying” the quantitative data, which could result in losing the richness of the daily reports. Rather than eyeballing the plots and categorizing widows on the basis of their trajectories, we chose to continue the iterative process of inquiry. Therefore, we selected interviews of widows with maximally divergent plots to include during the integration phase.

The plots and quantitative and qualitative findings prompted the selection of four additional interviews (with Cleo, Georgia, Sarah, and Patricia). Their interviews were examined with the other widows’ in the qualitative analyses conducted for the current study. Cleo’s interview was particularly important for clarifying the meaning of family support. She used literally supportive language, referring to her oldest son as “my rock right now” and describing his daughter as “sort of my crutch.” Cleo also knew that she could count on her widowed best friend: “I have her to fall back on, and she won’t back off at all.” The ability to fall back on someone when in need is central to the idea of social control. As displayed in her plots, Georgia’s satisfaction varied noticeably on a daily basis. During her initial interview, she gave useful insight into possible reasons for this variability. She described her “good days” as ones when “I had lots of interactions or something to look forward to” and “bad days” as ones when “I was in the house all day and didn’t see anyone.”

In some ways, exploratory studies seek to describe a phenomenon by mapping its extremes. Sarah’s and Patricia’s experiences and daily reports were among the most divergent of all the widows included in this study. Neither could be nominated as a general example representing the average widow, but together, they point out the breadth of the experiences. Fortunately, Sarah and Patricia also had two of the most detailed and interesting second interviews. Their follow-up interviews actually described the changes that occurred in the months between the first and second interviews. As noted previously, we believe that the follow-up interviews represented different experiences than those described in the initial interviews, on which the qualitative findings were based. Sarah’s and Patricia’s follow-up interviews, however, were selected as extensions in the integration phase on the basis of their outlier status in the trajectories and informative depictions of change in their interviews.

These selected initial and follow-up interviews provide some context for these widows’ daily satisfaction with support. Sarah’s plot shows consistent and high levels of satisfaction across the study. Her initial interview also reflected satisfaction. She reported receiving “great” support from her family and friends. Sarah emphasized the importance of her existing supports in her description of her supportive church group. Sarah’s family and widowed friends from church were still very involved and supportive at the time of her second interview. She said that when she walked into church, her friends “lined up for hugs.”4 Her bachelor son made sure that she did not spend too much time alone by having her answer phones at the family business and eating meals with her.

Although she reported being very satisfied with her support in both her daily assessments and interviews, Sarah struggled with tears through much of the second interview. She explained, “The only thing that’s bothering me really right now is that I’d like to have more emotional control” (see Note 4). Sarah was frustrated that she was unable to joke around or stay focused on activities she enjoyed. Although she could access support when she needed it, a description of social control, Sarah wanted more control of her emotions to be able to better engage in her social interactions. Day-to-day events, such as opening the bathroom cabinet and noticing that her husband’s toothbrush was no longer there, caused her to break down. She missed her husband terribly but explained that she would not “trade places with him because I wouldn’t want him to come back and feel like I feel” (see Note 4). Although she was clearly struggling, Sarah was aware of changes that had occurred. She told the story of attending the funeral of an acquaintance and seeing his wife there:

I thought, I feel so sorry for her. I am so glad I’m over certain phases of this. I’m just so grateful that time has gone by, that some of this is behind me. But I felt so sorry for her, because she’s just beginning to face this, the loneliness that comes. And I thought, I’m so glad that I’ve got that behind me. (see Note 4)

Patricia showed considerable fluctuation and reported the lowest satisfaction of any of the widows. Patricia is also important to include because of the nature of her life before the death. She described her husband as cold and difficult to live with. When Patricia and her daughter returned from the cemetery, her daughter said, “You’re free, Mama. You’re free!” Patricia responded to her, “You’re damn straight I am.” In her first interview, she mentioned only her daughter and one widowed friend who supported her.

By the second interview, Patricia’s disappointment in her support was clear: “You’re not anybody to anyone anymore. No one gives a damn. They can say all they want to say, ‘Oh, call me if you need me.’ Try calling them. ‘We’ll stop by to see you.’ Don’t wait for them” (see Note 4). Her widowed friend was difficult to spend time with because she was involved with caring for her own children and grandchildren. Patricia was also frustrated with her daughter’s inconsistent presence. In the initial interview, she mentioned that she was instituting changes throughout her life, including her relationship with her daughter. Her daughter’s involvement remained sporadic, but Patricia decided that she would enjoy her when she was around but no longer count on her. She explained,

I can remember vividly the week after [he] died when I would run the length of that apartment trying to get away from [the emptiness and loneliness]. Just anything, anything to break it. And [my daughter] avoided me. It would have been lovely if we could’ve … held hands, cried, screamed, cussed, swore, and got rid of it. But she didn’t want to get involved in my grief. And that’s okay. (see Note 4)

Although Patricia had little social support, she reported being better off since the death. She was involved in several different regular volunteer activities and continued to work on her art. Patricia appeared to want to be around people but was frustrated by her interactions with them:

If you try to talk to somebody about how you feel, they don’t really care. I found that out for myself. If I sit there and listen to their problems and their thoughts, then they’re very happy, so that’s what I do. … I have found that whenever you start to talk to somebody about how you feel about your husband, they instantly jump in with how they feel about theirs. … And if you talk about your loneliness, oh well, they’ve had that too. They’ve had that longer than you have … so what’s the point? (see Note 4)

Patricia decided that she would rather not waste her time engaging in these kind of interactions. She said, “I guess I’ll just be here by myself and really … I’m not really alone … I have God, I have the divine mother, I have the Lord Jesus, I have the universe” (see Note 4). Despite her lack of consistent social support, Patricia reported doing surprisingly well. Her well-being may have been a product of the release from an unhealthy marriage and the presence of internal resources such as her faith and belief in herself.

Overall, the HLM and constant comparative analyses present some common results. As displayed in the significant intercepts of the Level 1 models for family and friend support satisfaction, as well as the plots, as a group, the widows were satisfied with their support. One of the themes directly relates to these results: Most widows were impressed and satisfied by the overall support they received.

For some widows, the plots show considerable variability in day-to-day satisfaction with support. This variability may reflect different ways of viewing social support. Although most were satisfied overall, satisfaction with social support is determined by the experience of receiving (or not receiving) it. The fluctuations in support may be instances of the positive and negative interactions described in the themes. For example, a family member’s anticipation of a widow’s need for help with insurance paperwork may have made her more satisfied than usual. On the other hand, hovering and making decisions for her may have frustrated another widow. Additionally, widows’ awareness of their supporters’ other duties may have left them feeling ambivalent, wanting to ask for help but not wanting to be a burden.

Perceived social control may help explain differences in satisfaction with support. At the beginning of the study, those with higher perceived social control also reported being more satisfied with their support. With perceived control in the model, it was possible to detect an increase in the linear slope of satisfaction with social support. As a group, widows became more satisfied with their support over time. Those widows who reported higher social control at the beginning of the study, however, actually became less satisfied with their support over time. It may be that the overwhelming initial support discussed in the initial interviews faded as time passed, and these widows became frustrated when they were not able to access supports they believed they controlled. Social control involves both perceived access and purpose of support. It could also be that for the high-control widows, the support across the 3.5 months was not so much unavailable as not what they wanted. Cutrona and Russell (1990) proposed a model of optimal matching to understand the complexity of support in response to challenging life events. In this model, social support and other coping resources are most effective when the specific functions of the support match the demands of the stressor. The optimal matching model points to the importance of the timing of support, suggesting that a supportive intervention may need to adapt to a widow’s changing needs over time.

It was expected that the quantitative and qualitative analyses could yield somewhat different findings because of their paradigmatic bases. It should be noted that few outright discrepancies were found. Rather, the two kinds of data provided information regarding different kinds of questions about social support. The quantitative analyses point out that some global assessments of social support (e.g., perceived social control) are predictive of differences in satisfaction with support, whereas others (e.g., quantity of support from family and friends, perceived support, social coping [emotion focused and problem focused]) are not. It is interesting to note that the social coping measures did predict the trajectories of emotional well-being in dynamical systems analyses of this data set (Bisconti et al., 2006). This finding provides helpful clarification: As predicted by theory, social coping tactics are related to mental health outcomes, but they do not appear to be predictive of satisfaction with support. The qualitative themes flesh out considerable detail in what social support looks like and means for the widows in this study. Patton (2001) commented that the possibility of inconsistencies is not a weakness of mixed methods but rather an uncommon opportunity to examine the relationship between inquiry approach and the phenomenon under study.

The integration piece of this study in particular reveals the complexity of social support in widowhood. We selected additional interviews for maximum variation on the basis of their quantitative trajectories (two highly variable but stable over time, one without variability and stable, one variable and declining). Cleo and Georgia provided language illuminating how support feels and linked the qualitative and quantitative data by explaining the ups and downs in the daily ratings. Sarah and Patricia had plots that looked and initial interviews that sounded like polar opposites. Their follow-up interviews provided surprises. Sarah continued to have support but was frustrated by her inability to regulate her emotions, which she felt limited her power to use the support she had. She missed her husband terribly and struggled with daily activities. Patricia continued to lack support but reported that she was doing well. The death of her husband freed her. She appeared to rely on her internal resources, as opposed to social supports. Together with the qualitative themes and quantitative findings, this integration prompts careful consideration of what social support means and does for those who receive it.

Discussion

The plots of satisfaction with family and friend support revealed differences in within person variability. Some widows’ satisfaction fluctuated daily (1003, Georgia, 1011, Estelle, 1024, Cleo), whereas others’ remained stable (Sarah, Dorothy, Eleanor, 1018, 1021) across the approximately 3.5 months of daily assessments. As noted in the Level 1 models, the linear slope for satisfaction was nonsignificant, indicating that on average, there was no evidence of change in satisfaction with support over time. In contrast, the plots, as well as the analyses with perceived social control as a Level 2 predictor, suggest that there may actually be important individual differences in the trajectories of satisfaction with support. For example, although many widows seemed to have no positive or negative trends in their data, others demonstrated possible slopes (1003, 1016, Patricia, 1024). Analyses with perceived social control as a Level 2 predictor indicated that average satisfaction with support may in fact be increasing over time but that satisfaction with support actually declined for widows who were initially high in social control. The qualitative findings also highlight the complexity of the experience. Although widows described being satisfied overall with their support, Anne and others described their disappointment when the support they expected was not available. Betsy in particular noted that the availability of support may actually decline over time, even though widows may still want or need it.

The integration of these components occurred by selecting four additional cases in which their interview and daily assessment data were examined together. These interviews provided important linkages between the qualitative and quantitative components, as exemplified by the match between Sarah’s and Patricia’s daily appraisals and interview comments on their satisfaction with support. Additionally, Georgia’s comments on her good days and bad days give a striking explanation of the ups and downs many widows reported in their daily assessments. Finally, this integration piece highlights the complexity of social support. The detailed information, for Sarah and Patricia in particular, prompts careful consideration of social support as a commonly used variable in resilience research. In many ways, a “warm, fuzzy” and rather unitary conceptualization of support is assumed. As widows’ comments on worries about overburdening or having support taken away, this is not a complete picture. Sarah had abundant support but difficulty using it; Patricia lacked support but felt that her life was continually improving. Social support involves the relationships between people. As apparent in the interviews, these relationships are built over time and involve a variety of people. As visible in the plots and HLM analyses, satisfaction with these relationships depends on how much control an individual feels she has over the interaction and which day she is asked to appraise it. Exploring social support as an outcome, rather than a predictor, may help researchers better understand how it may promote or inhibit resilience and development.

Although the study offers a unique perspective on social support in the adjustment to widowhood, it is important to note its possible limitations. First, the study is limited by sample size. Even with 98 days of measurement, having only 20 participants is likely to affect the power to detect actual trends or differences in them. A small sample size may be especially problematic with such divergent profiles, as apparent in this study. Second, the study was limited by its sole inclusion of older women. There is evidence that the experiences of bereaved men (Umberson, Wortman, & Kessler, 1992) and younger widows (Sanders, 1993; Stroebe & Stroebe, 1987) are different from those of older widows. Therefore, the results of the present study are not assumed to generalize to other groups.

Another caveat is the rate of participation in the present study. Participation rates in bereavement studies are often less than 50%; moreover, participation rates in studies in which the bereaved were contacted without the assistance of health care facilities are often less than 30% (Stroebe & Stroebe, 1989). Similar to other studies of its kind, the present study had a participation rate of nearly 28%. The concern with seemingly low participation rates is that those who are willing to participate in bereavement research may be different from those who decline. In response to this point, Stroebe and Stroebe (1989) found that widows who agreed to participate were more depressed than their counterparts who chose not to participate. A benefit of qualitative studies broadly, and the exploratory focus of this overall study in particular, is not their generalizability but their rich description of the experience of individuals. Given the intensive data collection strategy involved in this study (daily surveys for the target widowed group and two sets of in-depth interviews and questionnaires and phone calls from the researchers every 2 weeks to check in and make sure study materials had been received for both groups), participating in the study could have become a form of support in itself.

One goal of this exploratory study was to provide a description of the transition to widowhood from a social support perspective. Rather than testing hypotheses, the work of this project was to produce a detailed account of the day-to-day experiences and meaning of social support for new widows. The findings of this study prompt the further investigation of this phenomenon by testing explicit questions in this data set for future studies. Further analyses with these data could directly examine what social support does, such as how the daily experience of social support affects mental health outcomes on days of stress. The plots of satisfaction with social support also suggest interesting extensions. Different profiles of satisfaction with support appear across the sample. It could be beneficial to test if there are meaningful differences between those who report consistent satisfaction and those who report variable satisfaction with support. If meaningful differences exist, it would be useful to explore what other variables predict these differences. These analyses would provide valuable perspective on the results of the quantitative analyses reported in this study. For example, both the highly variable and the highly stable widows could appear identical if examined only on the basis of slope. Both groups may show a nonsignificant overall slope, but the actual trajectories look quite different from each other. Additionally, a third possible profile could be those who show variability as well as some sort of slope in their trajectories. By empirically identifying different profiles in the data, interesting patterns in the trajectories could be explored. Mixture models of dynamics are still an open area of development but would be invaluable in addressing these questions of different models (i.e., kinds) of change.

Future studies could benefit by explicitly designing quantitative and qualitative data collection to provide feedback to each other. It could be particularly useful to construct the follow-up interviews to address change. Examining the trajectories prior to a followup interview would be especially informative in asking targeted questions about change. In light of the complexity depicted in the interviews and quantitative data in the present study, the inclusion of items tapping more nuanced questions about the nature and perception of interactions would be useful. Specifically, the inclusion of measures to detect negative aspects of social interactions is an important area for future research.

The present findings also have important implications for intervention. For the widows in this study, existing support networks were preferred over formal bereavement groups. Many of the helpful interactions involved long-standing friends, some of whom were also widowed. The widowed friends in these activity-based groups may provide the benefits of common experience and advice that are implied contributions of formal groups but also offer familiar and reliable support from long-standing relationships. These findings suggest that providing guidance to widows’ supporters may be more beneficial than encouraging widows to attend formal groups centered on loss. As evident in the interviews, widows furnished a wealth of information on the complexity of the experience of social support. Widows’ awareness of the absence, reluctance, or withdrawal of support were also striking. The variability in satisfaction with support over time displayed by some widows may be related to these negative interactions, which may in turn result in widows reevaluating their perceptions of social control. Several of the widows’ recommendations (good listening, sincerity, timing) are directly applicable to existing networks of informal supporters.

The trajectories and comments summarized above bring a deeper and richer perspective to our understanding of the complexity of social support following conjugal loss in later life. Nancy expertly spoke to the complexity of the experience of widowhood:

You know, one thing I’ve discovered is that there is no norm for widows … because of the different circumstances. … Everybody’s circumstances … [are] so different. … They have in common that they all lost their husbands, but in so many different ways. So there is no norm.

This project concurs in many ways with Nancy’s experiential findings. Despite the common experience of losing a husband, widows do not experience loss and widowhood in a uniform way. Some patterns, such as overall satisfaction with support, emerge in this complex experience, suggesting similarity but not uniformity. This finding is not disappointing; instead, it points directly to the value of mixed methods in providing a “picture” of a phenomenon with both a wide lens and fine-grained detail.

Figure 2.

Plots for Widows 1009 to 1016

Note: The x-axis shows days after death and the y-axis shows the level of satisfaction with family support.

Figure 3.

Plots for Widows 1017 to 1023

Note: The x-axis shows days after death and the y-axis shows the level of satisfaction with family support.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Pamela Maykut, Lisa Edwards, and Erika Summers-Effler, who acted as peer debriefers and guided various aspects of the qualitative component of this study. We also thank Dr. Scott E. Maxwell for statistical advice.

Footnotes

The initial steps of analysis of 2 additional interviews were conducted using the software program ATLAS/ti after the preliminary themes from the 11 interviews were written. Some new information and themes emerged, so it was important to bring in additional interviews to the point of saturation (E. A. Weitzmann, personal communication, September 2004), which was a component of the mixed methods extension. The 2 interviews that were examined using ATLAS/ti were included in the full constant comparative analysis with the other new interviews.

Pseudonyms are provided for the widows whose interviews were included in this study. The pseudonyms were used to protect confidentiality but to maintain humanness in recounting the widows’ stories. Widows who were included only in quantitative analyses are referred to by identification numbers.

It is interesting to note that the global measures of frequency and the number of people providing family and friend support, as assessed using a modified version of the Interview for Social Interaction (Henderson, Duncan-Jones, Byrne, & Scott, 1980), did not predict change in satisfaction with support on the daily level. Neither emotion- nor problem-focused social coping measure (Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989) was predictive of the intercepts or slopes for satisfaction with support from family or friends. These results were not significant at the .01 or .05 level and are not reported here.

This quotation is from the follow-up interview.

Contributor Information

Stacey B. Scott, University of Notre Dame, IN

C. S. Bergeman, University of Notre Dame, IN

Alissa Verney, University of Notre Dame, IN.

Susannah Longenbaker, University of Notre Dame, IN.

Megan A. Markey, University of Notre Dame, IN

Toni L. Bisconti, University of New Hampshire, Durham

References

- Bisconti TL, Bergeman CS, Boker S. Social support as a predictor of variability: An examination of the adjustment trajectories of recent widows. Psychology & Aging. 2006;21:590–599. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 1977;32:513–531. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Nesse RM, Vinokur AD, Smith DM. Providing social support may be more important than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science. 2003;14:320–327. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear modeling to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ, Willoughby MT. Testing main effects and interactions in latent curve analysis. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:220–237. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW. Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Pierce GR, editors. Social support: An interactional view. Oxford, UK: Wiley; 1990. pp. 319–366. [Google Scholar]

- Healy JM, Jr, Stewart A. On the compatibility of quantitative and qualitative methods for studying individual lives. Perspectives in Personality. 1991;3:35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S, Duncan-Jones P, Byrne DG, Scott R. Measuring social relationships: The Interview Schedule for Social Interaction. Psychological Medicine. 1980;10:723–734. doi: 10.1017/s003329170005501x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL, Antonucci TC. Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In: Baltes PB, Brim OC, editors. Life-span, development, and behavior. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 254–283. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mandara J. The typological approach in child and family psychology: A review of theory, methods, and research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:129–146. doi: 10.1023/a:1023734627624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Maykut PS, Morehouse RE. Beginning qualitative research: A philosophic and practical guide. Washington, DC: Falmer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA, Hogan NS. Quantitative or qualitative? Measurement issues in the study of grief. In: Strobe MS, Hansson RO, Strobe W, Schut H, editors. Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 89–118. [Google Scholar]

- Newman I, Ridenour C, Newman C, DiMarco G. A typology of research purposes and its relationship to mixed methods. In: Tashakkori A, Teddie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Reid DW, Ziegler M. The desired control measure and adjustment among the elderly. In: Lefcourt HM, editor. Research with the locus of control construct, Vol. 1: Assessment methods. New York: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders CM. Risk factors in bereavement outcome. In: Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO, editors. Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research and intervention. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1993. pp. 256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR. Social support: An interactional view. Oxford, UK: Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe W, Schut H. Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS, Stroebe W. Who participates in bereavement research? A review and empirical study. Omega. 1989;20:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W, Stroebe M. Bereavement and health. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Creswell JW. Editorial: The new era of mixed methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Wortman CB, Kessler RC. Widowhood and depression: Explaining long-term gender differences in vulnerability. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33:10–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]