Abstract

Dementia pugilistica (DP), a suite of neuropathological and cognitive function declines after chronic traumatic brain injury (TBI), is present in approximately 20% of retired boxers. Epidemiological studies indicate TBI is a risk factor for neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer disease (AD) and Parkinson disease (PD). Some biochemical alterations observed in AD and PD may be recapitulated in DP and other TBI persons. In this report, we investigate long-term biochemical changes in the brains of former boxers with neuropathologically confirmed DP. Our experiments revealed biochemical and cellular alterations in DP that are complementary to and extend information already provided by histological methods. ELISA and one-dimensional and two dimensional Western blot techniques revealed differential expression of select molecules between three patients with DP and three age-matched non-demented control (NDC) persons without a history of TBI. Structural changes such as disturbances in the expression and processing of glial fibrillary acidic protein, tau, and α-synuclein were evident. The levels of the Aβ–degrading enzyme neprilysin were reduced in the patients with DP. Amyloid-β levels were elevated in the DP participant with the concomitant diagnosis of AD. In addition, the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and the axonal transport proteins kinesin and dynein were substantially decreased in DP relative to NDC participants. Traumatic brain injury is a risk factor for dementia development, and our findings are consistent with permanent structural and functional damage in the cerebral cortex and white matter of boxers. Understanding the precise threshold of damage needed for the induction of pathology in DP and TBI is vital.

Key words: adult brain injury, axonal injury, immunoblots, neurodegenerative disorders, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Dementia pugilistica (DP), originally described as “punch drunk syndrome” by Martland in 1928,1 encompasses a suite of deleterious neuropathological and cognitive function declines resulting from chronic traumatic brain injury (TBI).2 The name evokes the fact that the syndrome has been strongly associated with prizefighting.3 DP is manifested in approximately 20% of retired boxers with incidence directly correlated to the number of boxing matches and blows to the head. In mechanical terms, the blows to the head can reach, on impact, speeds equal to or greater than 10 m/s, resulting in a translational acceleration of the brain equivalent to 50 g that produces shearing and compression with grave structural, biochemical, and functional consequences for the brain and other facial, neck, and body vital organs. The severity of injuries is further complicated by their cumulative nature and by the fact that many prizefighters may experience hundreds of matches during their careers.4,5 In general, professional boxers often exhibit some cognitive deficits and, in 10–20% of the cases, more serious neuropsychiatric consequences occur involving deficiencies in motor skills and behavior.4,5

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a well-defined neuropathological condition that results from TBI and has been recently reviewed by McKee and colleagues.6 CTE is not confined to prizefighting but has been observed in the participants of other dynamic and collision sports.7–10 Sports participants exhibit the suite of CTE-associated neurodegenerative changes and, in the case of former National Football League players, are at elevated risk for consequential morbidities such as Alzheimer disease (AD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.11 In addition, concussive head injuries have an increased prevalence in Iraq and Afghanistan military personnel,12–14 heightening concerns over long-term recovery prospects and stimulating efforts to mitigate TBI in wounded warriors.

Epidemiological studies indicate that TBI is a risk factor for neurodegenerative disorders15–21 including AD and Parkinson disease (PD). Some cases of DP harbor amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptide deposits in the form of diffuse plaques and abundant TAR DNA binding protein-43 kDa (TDP-43) inclusions in the brain and spinal cord.22,23 In addition to the Aβ deposits, other molecules strongly associated with neurodegenerative disorders including amyloid-beta precursor protein (APP), apolipoprotein E (ApoE), tau, ubiquitin, and α-synuclein are also altered.24,25 Some of the biochemical disturbances observed in AD and PD may be recapitulated in some DP and other TBI persons. These include amyloid deposition in the brain parenchyma and microvasculature, increased levels of APP and enzymes responsible for Aβ peptide production, neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) with abundant hyperphosphorylated tau as well as elevated quantities of α-synuclein and TDP-43.2,6,26–30

Studies of patients with TBI have revealed that APP, Aβ and tau peptide levels increase immediately after blunt concussive damage.26,31 In addition, increased levels of Aβ and tau were observed by microdialysis of brain interstitial fluid in patients with acute TBI.32,33 Head trauma also induces an acute elevation of APP and Aβ42 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with rapid deposition of diffuse plaques in gray matter (GM).24,34–38 In the swine experimental model of TBI, there is a long-lasting increase in axonal APP, β-site APP-converting enzyme, presenilin-1, and caspases.39 These observations suggest that Aβ and tau proteins are an acute phase response to brain injury.

Although numerous observational studies have examined the structural and anatomic changes correlated with TBI, analogous systematic and comparative analyses of the biochemical alterations are also needed to understand the complex pathophysiology that results from trauma.40–42 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and one-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) Western blot techniques were combined to quantify a panel of key proteins in unfixed, frozen GM and white matter (WM) from the frontal lobe to reveal any patterns of differential expression of these specific molecules between a cohort of three DP cases and three age-matched non-demented control (NDC) cases without a history of TBI.

Methods

Clinical history and neuropathology

Cases #1 and #2 were provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs and National Institute of Aging Boston University Alzheimer's Disease Center and case #3 was provided by the Massachusetts Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. A brief summary of the three cases is provided below. Macroscopic and microscopic neuropathology of cases #1 and #2 (in the present study) and their relationship to CTE were thoroughly described by McKee and associates in 2009.6 Case #1 in the present study corresponds to case #3 in the article by McKee and colleagues6 while case #2 has the same designation in both the article by McKee and coworkers6 and the present study.

Case # 1 (DP)

Case #1 was a male boxer with an ApoE ɛ3/3 genotype. He died of pneumonia at age 73. In his 50s, he began to be moody, restless, apathetic, withdrawn, irritable, agitated, verbally and physically aggressive, confused, and paranoid with episodes of dizziness and vertigo. Neurological and neuropsychological examination and testing revealed a visuospatially disoriented and inattentive person with learning and immediate and remote memory deficits and diminished executive function. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated generalized cortical atrophy with enlarged ventricles, cavum septum pellucidum, and a lacune in the right globus pallidus. Electroencephalography, magnetic resonance angiography, and carotid duplex ultrasonography demonstrated no detectable anomalies. In his younger years there was a history of occasional alcohol and tobacco use.

Physical and psychological testing at ages 67 and 70 showed a person with global deficits, prominent memory decline with swallowing difficulties, decreased up-gaze, masked facies, garbled speech, and slow shuffling gait. Several months before his death, the mini-mental status examination was as low as 7. Family history notes that dementia developed in one cousin and three uncles.

Neuropathology

The brain weight at autopsy was 1220 g. Frontal, parietal and temporal lobes as well as hypothalamus, thalamus, mammillary bodies entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala were atrophic. There was thinning of the corpus callosum with large and fenestrated cavum septum pellucidum. Lateral and third ventricles were enlarged. Visible dilation of the perivascular spaces in frontal and temporal WM was observed. There was one cm lacune in the right globus pallidus. The substantia nigra and locus ceruleus were overly pale with discoloration and atrophy of frontopontine fibers in the cerebellar peduncle. NFT, glial tangles (GT), and neuropil neurites (NN) were observed as patches in the frontal parietal, temporal, and occipital cortex. The hippocampus, amygdala, and entorhinal cortex revealed abundant NFT, including ghost NFT and severe neuronal loss. Abundant tau positive glial and NN were seen in the subcortical WM U-fibers, anterior and posterior commissures, and the thalamic and external and extreme capsules. High density of NFT and glial tangles were observed in the olfactory bulbs, thalamus, hypothalamus, striatum, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, locus ceruleus, nucleus basalis, inferior olives and the raphe, oculomotor and dentate nuclei as well as the midline tracts in the medulla.6

Case # 2 (DP+AD)

Case #2 was a male boxer with an ApoE ɛ3/4 genotype. He died at age 80 from septic shock. After his retirement, he became confused, disoriented, cognitively deficient, and with tendency to fall. In his late 70s, paranoia developed with increased memory loss and slow speech, agitation, and aggressive behavior and unstable gait with frequent falling necessitating multiple hospitalizations. In his younger years, he abused alcohol, smoked for 20 years, but exercised and was in excellent physical condition. Computed tomography scans 2 and 3 years before his death showed progressive cerebral and cerebellar atrophy with enlargement of ventricles. In terms of family history, his grandfather had cognitive decline and a brother had AD.

Neuropathology

The brain weight at autopsy was 1360 g. Partial discoloration of leptomeninges, moderate atrophy of frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes and marked atrophy of the hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, hypothalamus, thalamus, mammillary bodies, and corpus callosum were observed. Lateral and third ventricles were enlarged with cavum septum pellucidum. The substantia nigra and locus ceruleus were manifestly pale. In the cerebral cortex, there were abundant NFT, GT, and spindle NN positive for tau affecting a patchy pattern around blood vessels. Dense concentrations of NFT, GT, and NN were observed in the olfactory bulb, hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus nucleus basalis, striatum, globus pallidus, substantia nigra, raphe, periventricular gray locus ceruleus and oculomotor, red, reticular, and dentate nuclei as well as in the pontine base, tegmentum, and inferior olives. There were tau positive glia and NN in WM, being more evident in the midline tracts of the brainstem. Besides NFT, some other features of AD such as Aβ deposition (an inconsistent trait of CTE) were observed in this case as diffuse plaques in moderate quantities in frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices with few neuritic plaques, but interestingly, there were no amyloid deposits in the cerebral vasculature. These observations supported the secondary diagnosis of AD.6

Case # 3 (DP+PD)

Case #3 was a male boxer with the concurrent diagnoses of DP and PD. His ApoE genotype was ɛ3/3. He passed away at age 78. No further information on the clinical history of this person was available.

Neuropathology

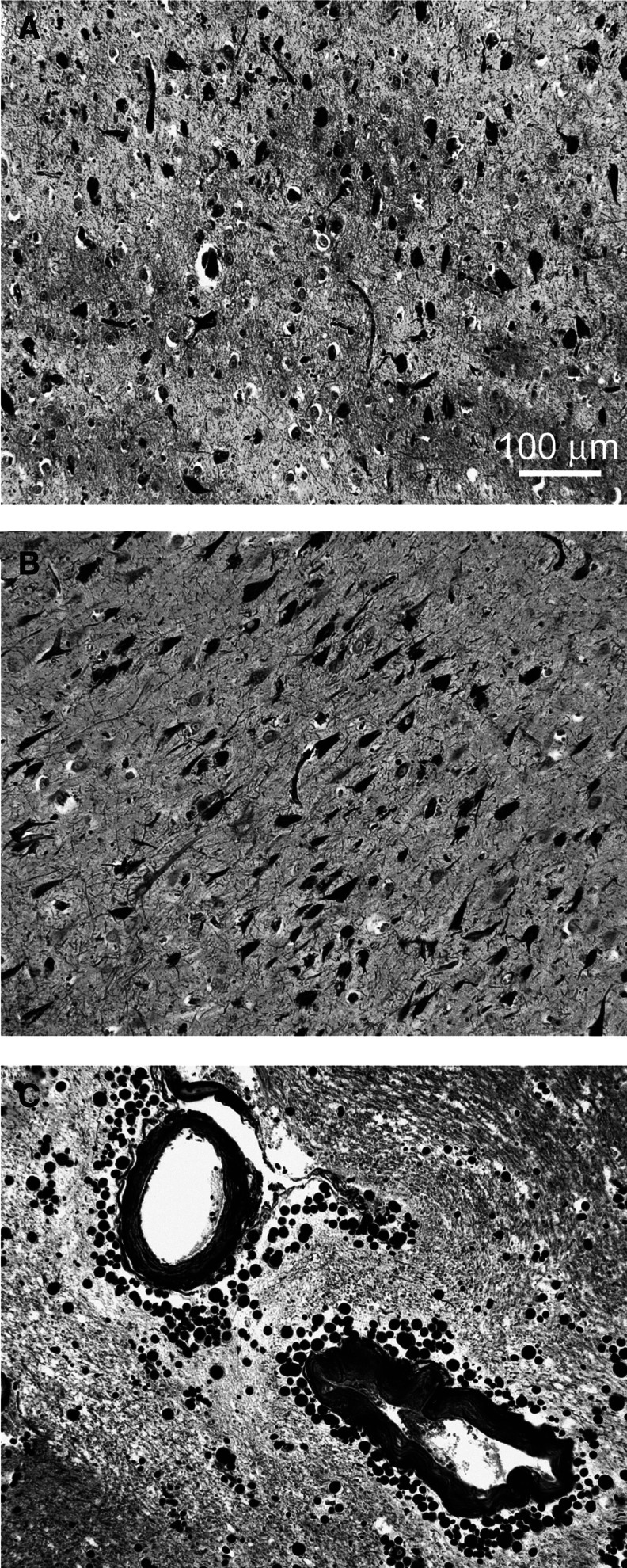

The brain weight at autopsy was 1480 g. The CSF appeared normal. There was mild atherosclerosis of the internal carotid arteries and moderate atherosclerosis of the circle of Willis. Diffuse mild atrophy of the cerebral hemispheres with moderate frontal polar atrophy, slight atrophy of hippocampi, and moderate enlargement of ventricles was observed. The GM had normal width with unremarkable WM. The corpus callosum was markedly thin in the posterior portion of the body. There was a fenestrated septum pellucidum commonly observed in DP. There were vast numbers of NFT in the medial temporal lobe and hippocampus (Fig. 1A,B) and scattered NFT in the brainstem structures, amygdala, and deep nuclei typical of DP. Neuritic plaques were absent. In addition, this person also had histological evidence of PD with abundant Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra. Lewy bodies, however, were not observed in the cerebral cortex. In some areas, there was clear evidence of corpora amylacea around some of the cortical areas close to the bottom of sulci (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Silver-stained (Bielschkowsky) sections depicting neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) and corpora amylacea of dementia pugilistica case # 3. (A) Medial temporal lobe and (B) hippocampus CA1 region showing numerous neurofibrillary tangles. (C) Abundant perivascular corpora amylacea in gray matter at the bottom of a temporal sulcus. Magnification of A, B, and C is 100X. Scale bar in A also applies to B and C.

Control cases

Three NDC cases were selected from our Brain and Body Donation Program at Banner Sun Health Research Institute.43 The operations of the Brain and Body Donation Program have been approved by the Banner Health Institutional Review Board. All persons enrolled in the Brain and Body Donation Program sign an informed consent approved by the Banner Health Institutional Review Board. These persons were age- and sex-matched to the three DP subjects and selected because they were not demented and did not harbor any neuropathological features associated with neurological disorders, including history of TBI. Table 1 shows the demographics and neuropathology of the NDC participants. These three persons were Caucasian males and had an average age of 75 years, and all three carried the ApoE ɛ3/3 genotype. In addition, they were classified as not having AD according to the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease criteria. A detailed description of the neuropathological scoring procedures is given elsewhere.43–45

Table 1.

Demographics and Neuropathological Scores for Non-Demented Control Subjects

| NDC | Expired age (y) | Sex | Brain weight (g) | ApoE genotype | Total plaque score | Total NFT score | Braak stage | Total CAA score | Total WMR score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 71 | M | 1300 | 3/3 | 0 | 0 | I | 0 | 0 |

| B | 75 | M | 1262 | 3/3 | 0 | 0.5 | I | 0 | 3 |

| C | 79 | M | 1260 | 3/3 | 0 | 3 | II | NA | 0 |

NDC, non-demented control; ApoE, apolipoprotein E; NFT, neurofibrillary tangles; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; WMR, white matter rarefaction; NA, not available.

1D-Western blot analysis in 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer

All materials were obtained from Life Technologies Corp. (Carlsbad, CA) and chemicals from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. A detailed protocol has been published elsewhere.46 Briefly, unfixed, frozen GM or WM from the frontal lobe was homogenized in 5% SDS, 5 mM Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8 with an Omni TH homogenizer and centrifuged. The supernatant was recovered and total protein measured with a Micro bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Proteins were separated on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Descriptions of all primary and secondary antibodies are shown in Table 2. All membranes were re-probed with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit actin antibody to serve as a total protein loading control. The trace quantity feature in Quantity One (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to measure the density of each band and corresponds to the measured area under each band's intensity profile curve. The units are in optical density×mm.

Table 2.

Antibodies Used in Western Blots

| Primary antibody | Antigen specificity or immunogen | Secondary antibody | Company/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT20APP | Last 20 aa of APP | M | Covance/SIG-39152 |

| Neprilysin | Rat neprilysin | R | Millipore/AB5458 |

| Tau (HT7) | Tau aa 159–163 | M | Pierce/MN1000 |

| BDNF/proBDNF | Internal region of BDNF | R | Santa Cruz/sc-546 |

| GFAP | Recombinant GFAP | R | Abcam/ab7260 |

| α-tubulin | Synthetic peptide of human α-tubulin | R | Cell Signaling/2144S |

| β-tubulin | N-terminal synthetic peptide of human β-tubulin | R | Cell Signaling/2128S |

| Kinesin 5A | Synthetic peptide: aa 1007–1027 | R | Pierce/PA1-642 |

| Dynein | cytoplasmic dynein from chicken embryo brain | M | Sigma/D5167 |

| MBP | aa 119–131 | M | Millipore/MAB381 |

| CNPase | Clone 11–5B | M | Sigma/C5922 |

| Myelin PLP | Synthetic C-terminal peptide | Millipore/MAB388 | |

| Actin Ab-5 | Clone C4 | M | BD TransductionLaboratories/A65020 |

| Actin | N-terminus of human α-actin | R | Abcam/Ab37063 |

CT, C-terminal; APP, amyloid-β precursor protein; aa, amino acid; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; GFAP, glial acidic fibrillary protein; MBP, myelin basic protein; CNPase, 2'3'-cyclic nucleotide 3'-phosphodiesterase; PLP, proteolipid protein; M, HRP conjugated AffiniPure goat-anti mouse IgG (catalog # 111-035-144, Jackson Laboratory); R, HRP conjugated AffiniPure goat-anti rabbit IgG, (catalog # 111-035-146 Jackson Laboratory); G, HRP conjugated AffiniPure bovine-anti goat IgG (catalog #805-035-180).

1D- and 2D-Western blot analysis in strongly chaotropic buffer

Fifty mg of unfixed, frozen GM or WM from the frontal lobe was homogenized in 700 μL of a strongly chaotropic buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 50 mM DTT, 40 mM Trizma pH 8.0) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) using a Teflon homogenizer. The homogenates were sonicated then incubated for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and subjected to a second round of sonication. After centrifugation for 20 min, 10,000×relative centrifugal force at 4°C (Beckman Coulter 22R, Brea, CA), the supernatant was collected and total protein measured with the 2D Quant kit (GE Lifesciences, Pittsburgh, PA). For 1D-Western analysis, 10 μg of total protein was placed in equilibration buffer (see below) and loaded onto 10% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technology Corp.). Proteins were separated by electrophoresis using NuPage 1XMOPS run buffer containing NuPage antioxidant. The remaining protocol was completed as described above and elsewhere46 for the 1D-Western blot using 5% SDS homogenates.

For 2D-Western analysis, 100 μg of total protein was collected from the chaotropic buffer homogenates and prepared for analysis using a G-Biosciences (St. Louis, MO) Perfect-FOCUS sample clean-up kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Protein pellets were reconstituted in 200 μL of rehydration buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 50 mM DTT, 1.25% IPG buffer pH 3–10 [GE Lifesciences, Piscataway NJ] with 0.002% bromophenol blue) and shaken for 1 h at RT. Immobiline DryStrip 11 cm, pH 3–10 gel strips were rehydrated overnight at RT in the above sample using a re-swelling tray (GE Lifesciences). Isoelectric focusing was performed as follows with an Ettan IPGphor system (GE Lifesciences): 50V for 1 h, 100V for 1 h, 200V for 1 h, 400V for 1 h, 800V for 1h, 1600V for 1 h, and 6000V for 1.5 h. Each strip was then incubated for 15 min in 5 mL of equilibration buffer 6 M urea, 2% SDS, 50 mM Tris pH 8.8, 30% glycerol, 0.002% bromophenol blue, and 65 mM DTT for 15 min at RT followed by equilibration in the same buffer with 125 mM iodoacetamide replacing DTT for 15 min at RT. Second-dimension electrophoresis was performed in Criterion® Tris-HCl, 4–20% gels (Bio-Rad) in 1X Tris/glycine/SDS run buffer (Bio-Rad) supplemented with NuPage antioxidant. Kaleidoscope prestained protein molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad) were loaded onto each gel. Once electrophoresis was complete, the gels were equilibrated for 15 min in 1X Tris/glycine transfer buffer containing 20% methanol and the proteins transferred onto 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) at 60 V for 1 h. Pierce's MemCode™ Reversible Protein Stain Kit was used to stain all proteins on each membrane to assess for equal protein load. Blocking, antibody incubation and detection were performed as previously described.46

Aβ, tau and α-synuclein ELISA quantification

All steps were performed at 4°C. For a detailed protocol, see Maarouf and associates.46 Frozen, unfixed GM and WM (100 mg), taken from the frontal lobe, were gently homogenized in 600 μL of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.8, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and centrifuged. The pellet was re-homogenized in 600 μL of 90% glass distilled formic acid (GDFA) and centrifuged. The recovered supernatant was dialyzed to remove the GDFA, lyophilized, and then reconstituted in 500 μL 5 M guanidine hydrochloride (GHCl), 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, PIC (Roche). The total protein in the Tris- and GDFA/GHCl-soluble fractions were measured using Pierce's Micro BCA kit. ELISA kits from Life Technologies Corp. were used to quantify Aβ40, Aβ42, tau, and α-synuclein according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analyses

Group comparisons were analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskall-Wallis (KW) test. This method was used given the small sample size. All values were adjusted with the KW algorithm. To account for corrections for multiple testing, a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 0.001 was used for the 35 comparisons that were performed (0.05/35–0.001).

Results and Discussion

We investigated the levels of protein and peptide markers in the GM and WM of three elderly demented persons who had sustained multiple head concussions resulting from professional boxing careers. Three age- and sex-matched NDC subjects exhibiting no visible amyloid plaques and harboring low levels of NFT (Table 1) served as controls for this study. The most prevalent neuropathological lesions detected in the DP brains were NFT (Fig. 1A,B and McKee and colleagues6) that could be a direct consequence of, or aggravated by, sustained TBI. In case #3, an abundant amount of corpora amylacea was observed close to the pial surfaces and around blood vessels (Fig. 1C). The origin of these lesions has been related to neuronal loss and severe central nervous system (CNS) trauma.47–50

We launched an extensive international search for frozen, unfixed brain tissue, suitable for protein chemistry studies, from professional boxers who died with the clinical diagnosis of DP and were able to acquire brain tissue from three cases. Therefore, procurement of suitable DP brain specimens limited the scope of this study. Further, distinguishing long-term lesions specifically ascribable to sustained and severe head trauma is hampered in the elderly by the prevalence of overlapping signs and symptoms of widespread neurodegenerative disorders. It is indisputable, however, that some of the cumulative physical effects of repetitive head trauma in collision sports result in permanent neuropathological lesions and increased risk of cognitive/behavioral consequences decades later. Our study reveals the enormous need for gathering more suitable postmortem brain specimens, from both young and elderly persons, to qualitatively identify the molecular substrates that are damaged by TBI and quantitatively assess the extension of these injuries.

APP, neprilysin, and Aβ

Increases in APP and Aβ have been observed in the acute phases of TBI,19,26,51–53 but no direct information is available regarding the functional and structural effects of long-term alterations in the levels of APP in DP. Accumulation of Aβ, however, a surrogate molecule for APP, has been reported in TBI in which diffuse plaques, neuritic plaques, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy have been observed.6

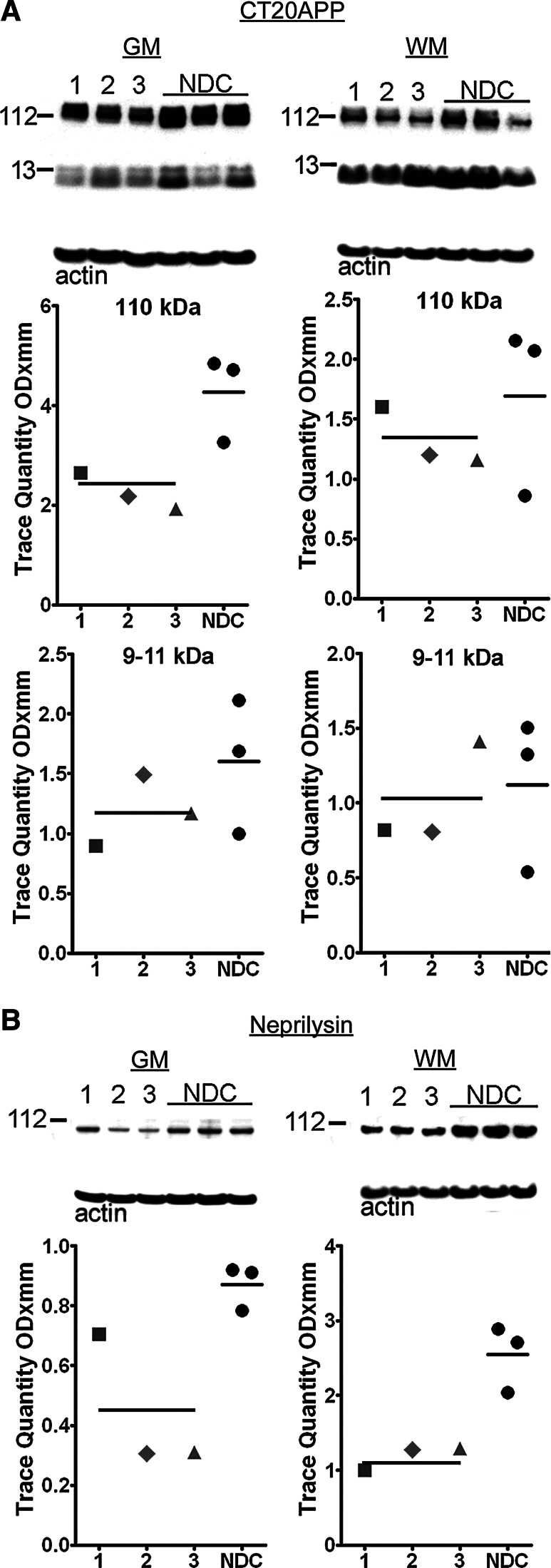

The CT20APP antibody identifies the 110 kDa APP as well as APP C-terminal (CT) peptides CT99 and CT83 (Fig. 2A), the substrates for Aβ peptides and the APP intracellular domain transcription factor. There were no significant differences in CT99/CT83 levels in the GM or WM between NDC and DP subjects (Fig. 2A). The mean APP holoprotein levels were significantly increased in the GM of the NDC cases (p=0.05), but there were no overall significant changes in this molecule in the WM (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Western blots of APP and its C-terminal peptides and neprilysin from gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) homogenates. All cases were quantified by scanning densitometry. The dementia pugilistica (DP) cases are represented as: squares=case # 1; diamonds=case # 2; triangles=case # 3. The mean of the DP and non-demented control (NDC) cases is indicated by a horizontal line. Molecular weights in kDa are reported of the left side of each blot. The actin loading control is below each blot. (A) CT20APP antibody demonstrates the 110 kDa APP holoprotein and the two CT-APP fragments CT99 (∼11 kDa) and CT83 (∼9 kDa). (B) The amyloid-β degrading enzyme, neprilysin, is shown at ∼100 kDa. CT, C-terminal; APP, amyloid-beta precursor protein.

In DP subjects, the amount of neprilysin was significantly decreased in the GM (p=0.05) as well as in the WM (p=0.05) relative to the NDC cases (Fig. 2B). The ∼86 kDa neprilysin is one of the major Aβ-degrading enzymes.54,55 It has been suggested that the failure of amyloid plaques to develop in some long-term survivors of TBI may be because of the action of neprilysin clearing the overproduced Aβ after damage.56 Interestingly, the levels of GT repeats in the neprilysin promoter apparently regulate the expression of this enzyme, suggesting that the amount of neprilysin is responsive to physiological conditions and may control whether Aβ plaques will develop in persons with TBI.57

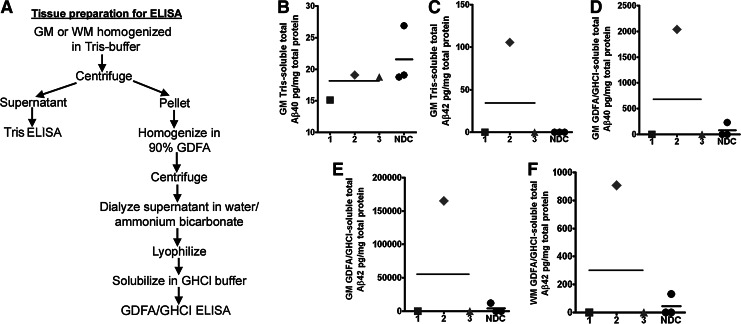

Brain tissue samples were prepared for Aβ, α-synuclein, and tau ELISAs as described in and summarized in the flowchart (Fig. 3A). With the exception of DP case #2, ELISA quantification of Tris-soluble and GDFA/GHCl-soluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in the GM of DP and NDC cases revealed no differences between these two groups (Fig. 3B–F). No Aβ40 was detected in the GDFA/GHCl-soluble WM extract in any of the cases under study (data not shown). Case #2 demonstrated high levels of Aβ peptides in the GM and WM, when compared with the other boxers and the NDC cases, as shown in Fig. 3C–F. The results are even more intriguing because the WM Aβ42 was high in this boxer (908 pg/mg of total protein), probably related to the fact that this region of the brain is greatly affected in boxing (see below). This is in agreement with the occurrence of amyloid plaques and the presence of an ApoE ɛ4 allele, which accompany the secondary diagnosis of AD. Intriguingly, persons with TBI are more susceptible to having negative outcomes if they are carriers of the ApoE ɛ4 allele,58–60 and AD is more likely to develop in boxers with an ApoE ɛ4 allele.61,62 Hence, the presence of ApoE ɛ4 alleles apparently modulates Aβ levels and is a decisive factor in the development of AD/amyloid deposit neuropathology. It also suggests that in some boxers, the acute increase in Aβ can regress while in others the accumulation of these peptides is more likely to become permanent. Although TBI clearly results in the acute elevation of APP and Aβ expression, not all ApoE ɛ4 carriers ultimately exhibit chronic deposition of Aβ and AD.

FIG. 3.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) scatter plots of Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels detected in gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) of the frontal lobe. (A) Flow chart summarizes GM and WM preparation for ELISA quantification. (B) GM Tris-soluble Aβ40. (C) GM Tris-soluble Aβ42. (D) GM GDFA/GHCl-soluble Aβ40. (E) GM GDFA/GHCl-soluble Aβ42. (F) WM GDFA/GHCl-soluble Aβ42. The WM of all dementia pugilistica and non-demented control (NDC) cases had no detectable levels of Aβ40 (data not shown). Notice that case #2, the only ApoE ɛ4 carrier, had the largest amount of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the GM and WM and the concurrent diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. See Figure 2 for shape codes. GDFA/GHCl, glass-distilled formic acid/5 M guanidine hydrochloride.

An interesting conundrum of TBI pathology is that it causes the immediate neuronal accumulation of APP/Aβ at the lesion sites,24,62 which suggests an acute phase pro-inflammatory reaction. This response has made APP the most sensitive and reliable immunostaining test for axonal damage in TBI.63 Studies in a series of surgical specimens undergoing neuropathological examination between 2 to 74 h after post-traumatic events have revealed rapid development of AD-like pathology.24 In approximately one-third of these patients, there was abundant diffuse amyloid deposits mainly composed of Aβ42. The rapid deposition of Aβ in diffuse plaques in TBI is probably associated with the generation of soluble APPα considered to be a neuroprotective factor.64 A concomitant byproduct of this proteolysis will be the production of Aβ17–42, which, together with Aβ1–42, are the main components of diffuse plaques.65 A property of the insoluble Aβ17–42 is its ability to rapidly aggregate, which may explain the extraordinarily fast appearance of diffuse plaques in some cases of acute TBI.

The transient elevation of Aβ1–42 in severe brain injury may be a response that aids in the sealing of broken axonal membranes. Likewise, vascular amyloid deposits could serve as hemostatic patches that halt blood–brain barrier leakages and contain microhemorrhages.66 Aβ peptides may also act as metal-sequestering molecules, thus preventing the generation of noxious reactive species and free divalent cations, such as calcium, and extravasated iron-bound hemoglobin.67–72 Further, the capacity of Aβ to produce vasoconstriction,73,74 together with its potent anti-angiogenic activity75 and microglia-mediated proinflammatory activity,76 suggest these peptides play a major role during acute injury as brain rescue functions.

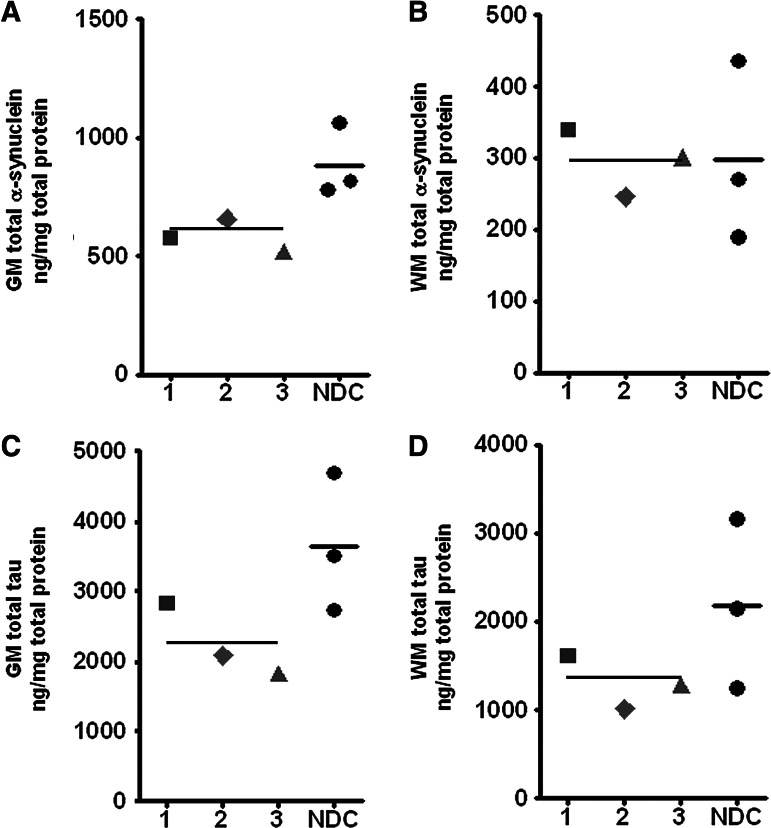

Alpha-synuclein

Our immunoassays demonstrated that total α-synuclein (Tris- plus GDFA/GHCl-extracted [Fig. 3A]) was significantly decreased in DP GM when compared with the NDC group (p=0.05; Fig. 4A), while the WM mean levels of this protein were equal in DP and NDC groups (Fig. 4B). Alpha-synuclein is a neuron-specific 140 amino acid-long molecule localized to the nucleus and to presynaptic terminals in which it probably functions in synaptic vesicle release and trafficking. Alpha-synuclein has an unstable and disordered structure that can assume monomeric and polymeric forms, adopt alternative conformations that range from amorphous aggregates to ordered filamentous structures and is capable of interacting with membranes.77 It has been recently suggested that α-synuclein can be transmitted from neuron to neuron via endocytosis.78 Alpha-synuclein deposition has been linked to familial and sporadic PD, where it is present in aggregated and phosphorylated insoluble forms in the Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. In acute TBI, α-synuclein is present in axonal swellings25,79 and detectable in CSF.80 Similar to the results with tau (see below), α-synuclein may be decreased in DP subjects because it is converted to insoluble forms that evade ELISA detection. In addition, our assays were performed on frontal lobe samples which may have yielded artefactually low values.

FIG. 4.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis of α-synuclein and tau in the gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) of dementia puglistica (DP) and non-demented control (NDC) persons. (A) GM and (B) WM α-synuclein. The brain was first homogenized in Tris-buffer and the remaining pellet homogenized in GDFA/GHCl (Fig. 3A). Both ELISAs were run independently and their results added to generate the scatter plots shown in Figures A and B. Therefore, the numbers given in the figure probably reflect the soluble α-synuclein and not the insoluble molecules associated to the Lewy bodies. Notice that the neuropathological analysis only reported Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra of boxer #3 who also had a concurrent neuropathological diagnosis of Parkinson disease. The frontal GM of this person showed an α-synuclein level similar to the other DP and NDC. (C) GM and (D) WM total tau ELISA. The brain was homogenized as described in the Figure 3A. Both ELISAs were run independently and their results added to generate the scatter plots shown in Figures C and D. See Figure 2 for shape codes. GDFA/GHCl, glass-distilled formic acid/5 M guanidine hydrochloride.

Tau

Immunoassays of total tau (Tris- plus GDFA/GHCl-extracted, Fig. 3A) demonstrated a substantial reduction of these proteins in the GM and WM in DP cases relative to the levels observed in the NDC that did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4C,D). Similarly, 1D-Western blot scanning densitometry of DP GM urea-soluble tau demonstrated a significant decrease in tau isoforms when compared with NDC cases (p=0.05) (Fig. 5A). A comparable pattern was also observed for WM tau (Fig. 5A), where the mean tau levels were largely decreased in the DP cohort relative to NDC subjects, although it did not reach significance. Interestingly, DP case #2, who also had the concomitant diagnosis of AD, had increased levels of tau relative to the other two DP subjects (Fig. 4A). To this respect, Schmidt and coworkers10 have suggested that recurrent TBI may activate pathological mechanisms that promote accumulation of tau similar to that observed in AD.10

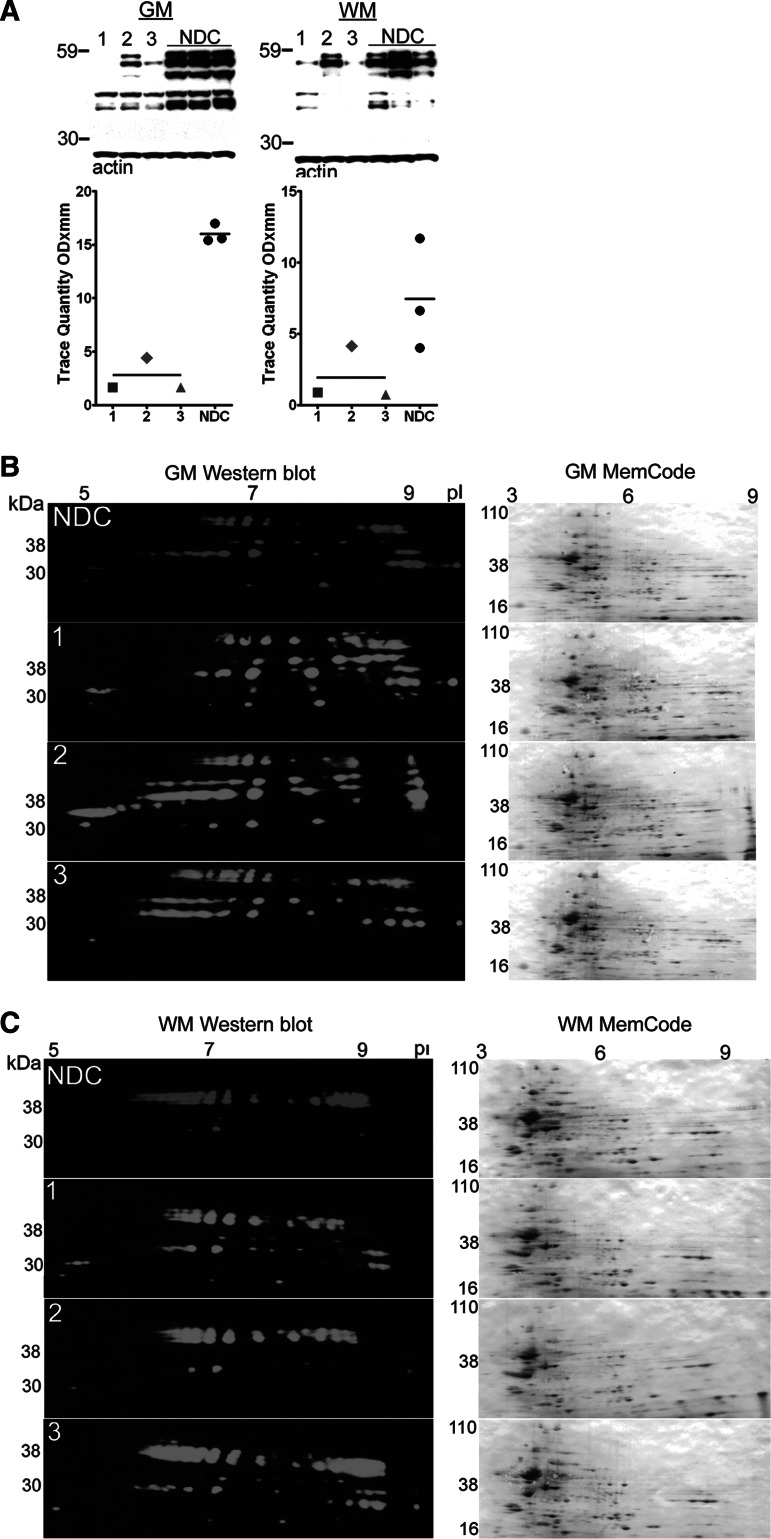

FIG. 5.

One-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) Western blot analyses of tau in the gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) of dementia puglistica (DP) and non-demented control (NDC) persons. (A) 1D-Western blots of GM and WM of urea/thiourea/CHAPS soluble homogenates detected with the HT7 tau antibody. Ten μg of total protein was loaded in each lane. See Figure 2 for shape codes and Western blot notes. (B) GM and (C) WM 2D-Western blot patterns (shown in green and red) as revealed by the HT7 tau antibody. A total of 100 μg of total protein was used for each blot. The numbers at the top of the blots relate to the pI, and the molecular weights are indicated at the left vertical axes. The top blots belong to a pool of the three NDC cases. The bottom three blots belong to each of the three DP cases as indicated at the left margin. The diversity of results and patterns shown in these figures are mainly because of the relative solubility of tau and the extreme insolubility of NFT in the used solvents and also because of the different physical partition techniques. Nonetheless, they demonstrate important isoform differences between DP and NDC cases. As a reference for total protein load, the membranes were stained with the MemCode protein stain after transfer. These blots are shown to the right of each HT7 Western blot.

Alternative splicing generates six tau isoforms containing 441, 412, 410, 383, 381, and 352 amino acid residues.81 Aging and neurodegenerative diseases produce extensive phosphorylation of tau resulting in the accumulation of highly insoluble NFT that are associated with glycolipids and probably heavily cross-linked.82–84 Recently, methylation of tau at residue K254, a competing site for ubiquitination, has been added to the post-translational modifications exhibited by these proteins.85 To assess the various isoforms of tau in DP and NDC subjects, urea/thiourea/CHAPS homogenates of the GM and WM were subjected to 2D-Western blotting. More isoforms of tau were present in the 2D Western blots of GM DP subjects as shown in Figure 5B. This probably represents the more soluble, less modified microtubule associated tau in the NDC pool, because these persons were classified as Braak stage I with correspondingly low NFT scores (Table 1). Major differences were evident in DP subjects relative to NDC in which cathodic proteins were elevated in a complex pattern of tau isoforms. Proteins with pI between 7.4–8 as well as a strong bias toward highly phosphorylated anodic species (pI<7.4) were, in general, more abundant in the persons with DP compared with the NDC pool. A 2D-Western blot of the WM tau, shown in Figure 5C, exhibited an increase in the lower molecular weight isoforms of tau in DP cases #1 and #3.

The quantitative differences in ELISA/1D-Western and 2D-Western blots of tau can be explained by the differential effects of the harsher solvent conditions and extended isoelectric separation in 2D-Western techniques. It is important to recognize that the urea-extracted brain homogenates only reveal soluble tau molecules and do not reflect the detergent and chaotropic agent-resistant tau/paired helical filaments (PHF) species present in situ. This approach, however, did reveal that while tau is primarily present in a free form or associated with microtubules in NDC subjects, DP cases exhibit a far greater abundance of insoluble, heavily post-translationally modified tau isoforms.86 In TBI, tau appears to be specifically concentrated in swollen areas of wounded axons.25 In contrast, chronic repetitive TBI, such as that incurred by boxers, induces the characteristic generation of NFT and neuropil threads similar to those observed in AD. The histological distribution of tau immunoreactivity in acute TBI also suggests damage to blood vessels and perivascular associated structures.10,28

Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

In the GM, the mature form of BDNF (∼15 kDa) was significantly reduced in subjects with DP versus NDC (p=0.05) (Fig. 6A). BDNF was below the limit of detection in the WM. This neurotrophin modulates synaptic plasticity and neural transmission and is essential for both CNS development and maintenance of cell survival. BDNF is produced as a proneurotrophin (∼30 kDa) that is hydrolyzed by furin to yield an active peptide of ∼15 kDa.87 In experimental animals, BDNF provision restores learning and memory capability and prevents or delays neuronal death.88 In rodents that undergo TBI, voluntary exercise enhances BDNF secretion improving recovery.89 Recent observations suggest that administration or induction of BDNF expression is useful for the treatment of those with TBI and post-traumatic stress disorder.90 This therapeutic approach can be achieved by the transplantation of neural stem cells genetically modified to produce BDNF.91

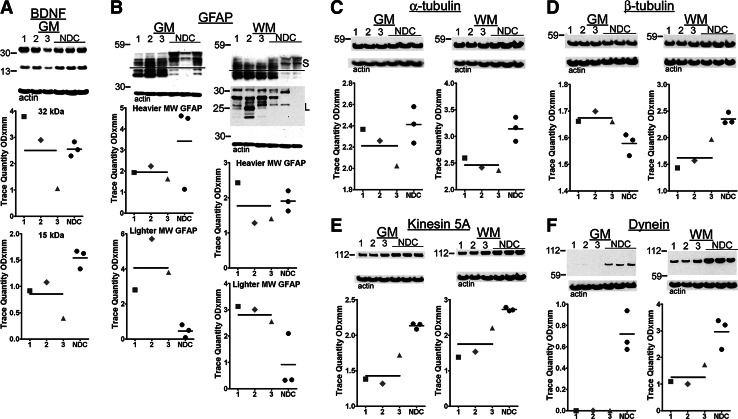

FIG. 6.

Western blots from gray matter brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) glial acidic fibrillary protein (GFAP), α-tubulin, β-tubulin, kinesin 5A, and dynein. (A) The average amounts of the active form of the BDNF (∼15 kDa) were decreased in the dementia pugilistica (DP) cases when compared with the non-demented controls (NDC). (B) The GFAP demonstrated a substantive quantitative increase of lighter molecular weight isoforms in the DP persons relative to NDC and different banding patterns as well as a large amount of degraded GFAP on a longer exposure time. For the purposes of quantification, we arbitrarily divided the GFAP pattern into two different groups as indicated by the horizontal line. Relative to the NDC average levels: (C) the mean α-tubulin was decreased in both GM and WM; (D) the β-tubulin was increased in the GM and decreased in the WM. Larger deviations were found in the cargo proteins, (E) kinesin 5A mean values were decreased in the GM and WM, (F) the dynein mean levels were also decreased, to values below the level of detection by Western blot analysis in GM and more modestly in WM. See Figure 2 for shape codes and Western blot notes. MW, molecular weight; S, short exposure; L, long exposure.

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)

GFAP-antibody reactive material was resolved into heterogeneous bands ranging from 52–40 kDa (Fig. 6B). Close inspection of the gel patterns reveal substantial differences in the banding patterns between DP and NDC subjects, with lower molecular weight bands significantly under-represented in the NDC cases (labeled as S, short exposure) relative to DP (p=0.05 for both GM and WM). There were no significant differences in the heavier molecular weight bands between NDC and DP groups. Long exposure time (labeled as L) revealed additional low Mr protein GFAP bands (∼25–20 kDa) predominantly in the WM of DP cases. It is unclear if these truncated forms result from caspase cleavage.92 This observation suggests that in DP, in addition to gliosis, biochemical alterations after injury result in the permanent production of lower molecular weight GFAP species.

GFAP is present in the astrocytes, where it modulates motility and structural shape. Differential DNA splicing generates four different species of mRNA resulting in proteins of 432, 387, 366, and 347 amino acids.93 Proteomic analysis of GFAP in AD and older control persons reveals a complex pattern of up to 46 soluble isoforms resulting from post-translational modifications mainly from phosphorylation, N- and O-glycosylations, as well as proteolytic cleavage.94,95 Assembly of GFAP into filamentous structures is partially modulated by the degree of phosphorylation.96 TBI and diffuse axonal injury can cause widespread neuronal and axonal destruction eliciting extensive glial scarring,97 which may explain the increase in GFAP observed in our experiments and by other groups.98–100 Axonal re-growth may also be hindered by molecules present within the glial scar101,102 that may interfere with neuronal regeneration and create long-lasting neuropsychological deficiencies. Previous neuropathological studies have demonstrated that astrogliosis is associated with neurodegenerative disorders and TBI.6,97,103–105

Serum GFAP levels in persons with acute TBI serve as a tool for assessment of CNS damage and prognosis.106–108 A recent systematic study of the CSF of Olympic boxers showed significant increases in the levels of GFAP, neurofilament-light chain, total-tau, and S100B after 1–6 and 14 days after their fights.109 A similar study of boxers also demonstrated a significant elevation of GFAP, neurofilament-light chain, and total-tau in CSF 7–10 days after a match.110 These data suggest that significant damage is inflicted early, perhaps immediately, in the careers of boxers with degenerative changes accumulating steadily with continued participation in the sport.

Fast axonal transport proteins: α-tubulin, β-tubulin, kinesin, and dynein

DP cases contained similar average amounts of GM α-tubulin and β-tubulin in comparison with the NDC cases (Fig. 6C,D). In contrast, the WM of the boxers demonstrated a significant decline in both molecular classes (α-tubulin: p=0.05 and β-tubulin: p=0.05) (Fig. 6C,D). In the GM, kinesin was significantly decreased in the DP group compared with the NDC subjects, and dynein levels fell below the limit of detection in all three DP cases (p=0.05 and p=0.05, respectively) (Fig. 6E,F). The WM exhibited significant reductions in kinesin and dynein in DP relative to the NDC cohort (p=0.05 and p=0.05, respectively) (Fig. 6E,F).

Proteins and organelles necessary for neuronal development and structural and functional maintenance are transported bi-directionally along microtubules by the molecular motors kinesin and dynein.111 Our data suggest that boxing may produce widespread mechanical damage to axonal transport resulting in chronic metabolic and neuropsychological deficits.112 The stresses generated by violent rotational concussive forces produce axonal injury resulting in complete axonal discontinuity, axonal retraction, and Wallerian degeneration.113 The dynamic stretching of axons translates into axonal undulating deformation with distortion/separation of myelin lamellae, vacuolization, and breakage of the axonal membrane and toxic calcium uptake.113 These structural and ionic changes are accompanied by concurrent clumping and granular disintegration of microtubules and neurofilaments. The disrupted microtubules interrupt both anterograde and retrograde axonal flow, leading to cargo accumulation and axonal swellings in which mitochondria and other organelles conglomerate.114–120 These axonal dysfunctions could be aggravated by hemorrhagic and ischemia lesions.121 Interestingly, unmyelinated axons are more vulnerable to trauma and have a more arduous recovery after TBI.122

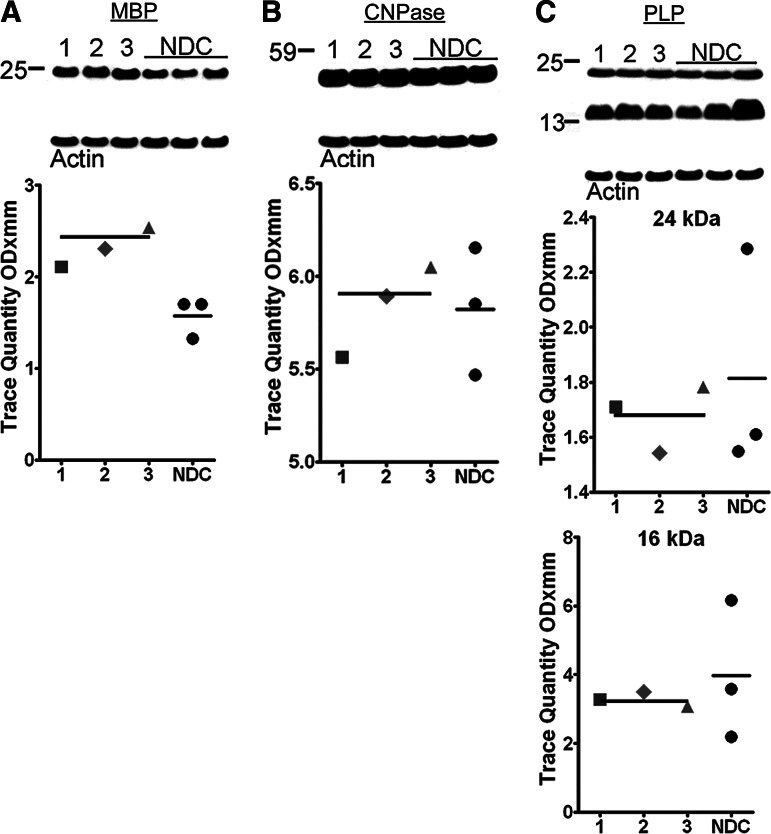

Myelin-associated proteins

Western blots were used to quantify WM myelin-associated proteins: myelin basic protein (MBP) (Fig. 7A), 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase (Fig. 7B), and myelin proteolipid protein (PLP) (Fig. 7C) in our two groups. With the exception of MBP, which was increased in DP relative to NDC and reached significant levels (p=0.05), the remaining myelin protein levels did not differ between the two cohorts. There is extensive evidence of myelin pathology in both AD123,124 and in TBI, which has been recently reviewed and elegantly synthesized by George Bartzokis.125 It is possible that increased MBP levels in the WM of DP subjects represent an attempt to specifically repair traumatically injured axons. Alternatively, it might simply reflect the accumulation of dysfunctional molecules.

FIG. 7.

Western blots from white matter homogenates of myelin-associated proteins. The mean myelin basic protein (MBP) (A) levels were discretely elevated in the dementia pugilistica (DP) cases when compared with the non-demented controls (NDC). The average CNPase (B) had nearly identical mean values between the two diagnostic groups. Both myelin proteolipid protein (PLP) (C) isoforms were slightly decreased in the DP cases relative to the NDC. See Figure 2 for shape codes and Western blot notes. CNPase, 2'3'-cyclic nucleotide 3'-phosphodiesterase.

It has been recently discovered that MBP is capable of inhibiting Aβ fibrillization126 and can degrade Aβ peptides.127 This enzymatic activity may aid in controlling the sudden outburst of APP/Aβ characteristic of the acute phases of TBI, and this might partially explain why DP cases are commonly found without much amyloid deposited.

Conclusions

We examined alterations in a suite of molecular biomarkers associated with all phases of TBI, from acute to chronic, in three neuropathologically confirmed DP subjects, and a summary of our observations is presented in Table 3. Although our investigation was limited in number by the extreme scarcity of unfixed DP brain samples suitable for biochemical analysis, our experiments clearly revealed deleterious transformations and marked deficiencies of critical functional proteins such as the neurotrophin BDNF.

Table 3.

Summary of Biochemical Data

| ELISA results | DP Case #1 | DP Case #2 | DP Case #3 | DP mean | NDC Case A | NDC Case B | NDC Case C | NDC mean | Kruskall-Wallis value | p value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 3B | |||||||||||

| GM Tris-soluble total Aβ40 pg/mg total protein | 15 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 27 | 19 | 19 | 22 | 1.26 | 0.26 | 1.09 |

| Figure 3C | |||||||||||

| GM Tris-soluble total Aβ42 pg/mg total protein | 0 | 106 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 1.00 | 0.32 | — |

| Figure 3D | |||||||||||

| GM GDFA/GHCl-soluble total Aβ40 pg/mg total protein | 0 | 2040 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 230 | — | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.72 |

| Figure 3E | |||||||||||

| GM GDFA/GHCl-soluble total Aβ42 pg/mg total protein | 0 | 165060 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 12100 | — | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.75 |

| Figure 3F | |||||||||||

| WM GDFA/GHCl-soluble total Aβ42 pg/mg total protein | 0 | 908 | 0 | — | 131 | 0 | 0 | — | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.69 |

| Figure 4A | |||||||||||

| GM total α-synuclein ng/mg total protein | 574 | 656 | 521 | 584 | 1059 | 816 | 778 | 884 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 2.55 |

| Figure 4B | |||||||||||

| WM total α-synuclein ng/mg total protein | 339 | 246 | 301 | 295 | 436 | 270 | 189 | 298 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.03 |

| Figure 4C | |||||||||||

| GM total tau ng/mg total protein | 2830 | 2090 | 1822 | 2247 | 4682 | 3499 | 2721 | 3634 | 2.33 | 0.13 | 1.76 |

| Figure 4D | |||||||||||

| WM total tau ng/mg total protein | 1614 | 1014 | 1280 | 1303 | 3158 | 2143 | 1246 | 2182 | 1.19 | 0.28 | 1.24 |

| Western blot results (optical density) | DP Case #1 | DP Case #2 | DP Case #3 | DP mean | NDC Case A | NDC Case B | NDC Case C | NDC mean | Kruskall-Wallis value | p value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 2A | |||||||||||

| GM CT20APP 110 kDa | 2.650 | 2.181 | 1.926 | 2.252 | 4.839 | 3.263 | 4.711 | 4.271 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 2.99 |

| GM CT20APP 9–11 kDa | 0.899 | 1.492 | 1.169 | 1.187 | 2.114 | 0.998 | 1.691 | 1.601 | 1.19 | 0.28 | 0.91 |

| WM CT20APP 110 kDa | 1.606 | 1.202 | 1.155 | 1.321 | 2.156 | 2.072 | 0.860 | 1.696 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.70 |

| WM CT20APP 9–11 kDa | 0.818 | 0.806 | 1.410 | 1.011 | 1.503 | 1.327 | 0.537 | 1.122 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.25 |

| Figure 2B | |||||||||||

| GM neprilysin | 0.706 | 0.306 | 0.309 | 0.440 | 0.784 | 0.919 | 0.911 | 0.871 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 2.50 |

| WM neprilysin | 0.997 | 1.274 | 1.290 | 1.187 | 2.713 | 2.885 | 2.041 | 2.546 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 4.00 |

| Figure 5A | |||||||||||

| GM tau | 1.659 | 4.419 | 1.649 | 2.576 | 15.414 | 15.599 | 16.975 | 15.996 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 7.06 |

| WM tau | 0.885 | 4.149 | 0.722 | 1.919 | 6.626 | 11.692 | 4.008 | 7.442 | 2.33 | 0.13 | 1.83 |

| Figure 6A | |||||||||||

| GM BDNF 32 kDa | 3.794 | 2.894 | 1.051 | 2.580 | 2.295 | 2.529 | 2.832 | 2.552 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.03 |

| GM BDNF 15 kDa | 0.918 | 1.079 | 0.394 | 0.797 | 1.334 | 1.626 | 1.669 | 1.543 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 2.19 |

| Figure 6B | |||||||||||

| GM GFAP HMW | 1.927 | 2.234 | 1.622 | 1.928 | 4.621 | 1.134 | 4.505 | 3.420 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 1.04 |

| GM GFAP LMW | 2.805 | 5.707 | 3.795 | 4.102 | 0.489 | 0.079 | 0.808 | 0.459 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 3.37 |

| WM GFAP HMW | 2.430 | 1.278 | 1.401 | 1.703 | 2.197 | 1.625 | 1.894 | 1.905 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 1.26 |

| WM GFAP LMW | 3.127 | 3.005 | 2.545 | 2.892 | 2.100 | 0.335 | 0.319 | 0.918 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 2.61 |

| Figure 6C | |||||||||||

| GM α-tubulin | 2.368 | 2.258 | 2.022 | 2.216 | 2.238 | 2.573 | 2.415 | 2.409 | 1.19 | 0.28 | 1.09 |

| WM α-tubulin | 2.595 | 2.416 | 2.360 | 2.457 | 2.908 | 3.165 | 3.359 | 3.144 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 3.71 |

| Figure 6D | |||||||||||

| GM β-tubulin | 1.662 | 1.699 | 1.660 | 1.674 | 1.611 | 1.591 | 1.532 | 1.578 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 2.85 |

| WM β-tubulin | 1.431 | 1.569 | 1.967 | 1.656 | 2.283 | 2.478 | 2.295 | 2.352 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 3.24 |

| Figure 6E | |||||||||||

| GM kinesin 5A | 1.383 | 1.319 | 1.720 | 1.474 | 2.153 | 2.106 | 2.087 | 2.115 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 4.14 |

| WM kinesin 5A | 1.379 | 1.532 | 2.208 | 1.706 | 2.691 | 2.717 | 2.785 | 2.731 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 3.26 |

| Figure 6F | |||||||||||

| GM dynein | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.575 | 0.643 | 0.940 | 0.719 | 4.36 | 0.04 | — |

| WM dynein | 1.092 | 1.002 | 1.726 | 1.273 | 3.221 | 3.378 | 2.304 | 2.968 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 3.41 |

| Figure 7A | |||||||||||

| WM MBP | 2.106 | 2.304 | 2.539 | 2.316 | 1.701 | 1.324 | 1.703 | 1.576 | 3.86 | 0.05 | 3.36 |

| Figure 7B | |||||||||||

| WM CNPase | 5.594 | 5.893 | 6.047 | 5.845 | 5.849 | 6.153 | 5.468 | 5.823 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.10 |

| Figure 7C | |||||||||||

| WM PLP 24 | 1.710 | 1.541 | 1.782 | 1.678 | 1.549 | 1.610 | 2.285 | 1.815 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.46 |

| WM PLP 16 kDa | 3.285 | 3.500 | 3.072 | 3.286 | 2.186 | 3.591 | 6.165 | 3.981 | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.48 |

ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; DP, dementia pugilistica; NDC, non-demented control; GM, gray matter; GDFA/GHCl, glass-distilled formic acid/guanidine hydrochloride; WM, white matter; CT, C-terminal; APP, amyloid-beta precursor protein; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; HMW, high molecular weight; LMW, low molecular weight; MBP, myelin basic protein; CNPase, 2'3'-cyclic nucleotide 3'-phosphodiesterase; PLP, proteolipid protein.

Our investigation suggests the biochemical responses associated with DP are long-lasting and permanent. Changes in key WM molecules suggest wide-ranging dysmyelination/defective re-myelination that may result in faulty transmission of action potentials with ultimately global deleterious impacts on cognitive function. In addition, neuritic alterations are also revealed by the decreased levels of critical cargo proteins such as kinesin and dynein with potentially ominous implications for synaptic transmission. An apparently permanent astrogliosis was present in both GM and WM, which was associated with a uniquely modified biochemical profile of enhanced GFAP accumulation in both compartments.

TBI results in an array of pathophysiological responses and clinical consequences similar to a subset of those observed in AD and PD including an acute increase in APP and Aβ levels and disturbances in the metabolism of tau and α-synuclein. It is unclear whether CTE represents a true risk factor for the precipitation of AD pathology or is an aggravating comorbidity for dementia emergence. The lack of amyloid deposits in a majority of DP cases suggests that either the trauma was insufficient to induce APP/Aβ expression or the acute phase increase is reversible. In sharp contrast, a number of biochemical and cellular reactions to chronic damage are extensive and permanent in DP. Tau deposition is widespread, and the post-translational processing of this molecule remains altered decades after subjects had retired from prizefighting. This observation suggests that the physical damage sufficient to provoke pathological tau processing cannot be remediated, and once a threshold is reached, pathological conversion of tau proceeds relentlessly. Studies of boxers at comparatively early points in their careers109,110 have revealed that alterations in the levels of CSF tau and other signal molecules of brain damage are clearly detectable. Although DP has been linked to chronic damage, these observations raise the concern that despite apparently complete recovery after bouts, the threshold for irreversible pathology induction remains unknown.

It is now recognized that thousands of participants in collision sports such as football are at risk for development of CTE and consequent dementia. Augmenting histological forensics with sensitive biochemical/proteomic analyses may reveal signs of incipient CTE in cases exhibiting only minimal physical alterations. The critical need to accurately quantify, and possibly mitigate, the risks involved with sports participation makes it vital to understand the precise conditions that instigate consequential reactive brain pathology. Proactive efforts to secure suitable brain specimens from persons of all ages for detailed histological and biochemical analyses are essential to qualitatively identify the key molecular substrates impacted by TBI and quantitatively assess the extent and evolution of these injuries.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by The National Institute on Aging (R01 AG019795), by the State of Arizona Alzheimer's Disease Research Consortium. The Brain and Body Donation Program is supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS0702026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer's Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer's Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 011, 05–901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium), and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research. We would like to kindly acknowledge Dr. Ann McKee from the Department of Veterans Affairs and National Institute of Aging Boston University Alzheimer's Disease Center (P30 AG13846) for aid in facilitating the provision of DP brain tissues of cases #1 and #2 and for critical review of the manuscript. We also appreciate the Neuropathology Core of the Massachusetts Alzheimer Disease Research Center (P50 AG005134) and Ms. Karlotta Fitch of the Massachusetts Neuropathology Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, for providing DP brain tissue of case #3. We are in debt to Dr. Dean C. Luehrs for critical review of the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

Drs. Kokjohn, Hunter, Rodriguez, Kalback, Roher, Ms. Maarouf, Ms. Whiteside, Mr. Malek-Ahmadi and Mr. Daugs have no competing interests to declare. Dr. Jacobson has received salary and indirect support from Bayer, Eisai, Elan, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Genentech. Dr. Sabbagh has received support from Lilly, Avid, Bayer, Baxter, GE, BMS, Pfizer, Janssen, Eisai, Genentech, and Piramal. Dr. Beach has received support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Schering-Bayer Pharmaceuticals, and GE Healthcare.

References

- 1.Martland H.S. Punch drunk. JAMA. 1928;91:1103–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corsellis J.A. Bruton C.J. Freeman-Browne D. The aftermath of boxing. Psychol. Med. 1973;3:270–303. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan B.D. Chronic traumatic brain injury associated with boxing. Semin. Neurol. 2000;20:179–185. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forstl H. Haass C. Hemmer B. Meyer B. Halle M. Boxing-acute complications and late sequelae: from concussion to dementia. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010;107:835–839. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casson I.R. Siegel O. Sham R. Campbell E.A. Tarlau M. DiDomenico A. Brain damage in modern boxers. JAMA. 1984;251:2663–2667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKee A.C. Cantu R.C. Nowinski C.J. Hedley-Whyte E.T. Gavett B.E. Budson A.E. Santini V.E. Lee H.S. Kubilus C.A. Stern R.A. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2009;68:709–735. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saulle M. Greenwald B.D. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a review. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 20122012:816069. doi: 10.1155/2012/816069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern R.A. Riley D.O. Daneshvar D.H. Nowinski C.J. Cantu R.C. McKee A.C. Long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma: chronic traumatic encephalopathy. PM. R. 2011;3(Suppl 2):S460–S467. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gavett B.E. Stern R.A. McKee A.C. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a potential late effect of sport-related concussive and subconcussive head trauma. Clin. Sports Med. 2011;30:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.007. , xi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt M.L. Zhukareva V. Newell K.L. Lee V.M. Trojanowski J.Q. Tau isoform profile and phosphorylation state in dementia pugilistica recapitulate Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101:518–524. doi: 10.1007/s004010000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehman E.J. Hein M.J. Baron S.L. Gersic C.M. Neurodegenerative causes of death among retired National Football League players. Neurology. 2012;79:1970–1974. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826daf50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snell F.I. Halter M.J. A signature wound of war: mild traumatic brain injury. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2010;48:22–28. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20100108-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wojcik B.E. Stein C.R. Bagg K. Humphrey R.J. Orosco J. Traumatic brain injury hospitalizations of U.S. army soldiers deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010;38(Suppl 1):S108–S116. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoge C.W. McGurk D. Thomas J.L. Cox A.L. Engel C.C. Castro C.A. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:453–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heyman A. Wilkinson W.E. Stafford J.A. Helms M.J. Sigmon A.H. Weinberg T. Alzheimer's disease: a study of epidemiological aspects. Ann. Neurol. 1984;15:335–341. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amaducci L.A. Fratiglioni L. Rocca W.A. Fieschi C. Livrea P. Pedone D. Bracco L. Lippi A. Gandolfo C. Bino G. Prencipe M. Bonattim M.L. Carella F. Tavolato B. Ferla S. Lenzi G.L. Grigoletto F. Schoenberg B.S. Risk factors for clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study of an Italian population. Neurology. 1986;36:922–931. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortimer J.A. van Duijn C.M. Chandra V. Fratiglioni L. Graves A.B. Heyman A. Jorm A.F. Kokmen E. Kondo K. Rocca W.A. Shalat S.L. Soininen H. Hofman A. Head trauma as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: a collaborative re-analysis of case-control studies. EURODEM Risk Factors Research Group. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1991;20(Suppl 2):S28–S35. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.supplement_2.s28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gualtieri T. Cox D.R. The delayed neurobehavioural sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1991;5:219–232. doi: 10.3109/02699059109008093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinton J. Ambler M.W. Roberts G.W. Post-traumatic Alzheimer's disease: preponderance of a single plaque type. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1991;17:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1991.tb00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breteler M.M. Claus J.J. van Duijn C.M. Launer L.J. Hofman A. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease. Epidemiol. Rev. 1992;14:59–82. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayeux R. Ottman R. Tang M.X. Noboa-Bauza L. Marder K. Gurland B. Stern Y. Genetic susceptibility and head injury as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease among community-dwelling elderly persons and their first-degree relatives. Ann. Neurol. 1993;33:494–501. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKee A.C. Gavett B.E. Stern R.A. Nowinski C.J. Cantu R.C. Kowall N.W. Perl D.P. Hedley-Whyte E.T. Price B. Sullivan C. Morin P. Lee H.S. Kubilus C.A. Daneshvar D.H. Wulff M. Budson A.E. TDP-43 proteinopathy and motor neuron disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010;69:918–929. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ee7d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costanza A. Weber K. Gandy S. Bouras C. Hof P.R. Giannakopoulos P. Canuto A. Review: Contact sport-related chronic traumatic encephalopathy in the elderly: clinical expression and structural substrates. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2011;37:570–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikonomovic M.D. Uryu K. Abrahamson E.E. Ciallella J.R. Trojanowski J.Q. Lee V.M. Clark R.S. Marion D.W. Wisniewski S.R. Dekosky S.T. Alzheimer's pathology in human temporal cortex surgically excised after severe brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2004;190:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uryu K. Chen X.H. Martinez D. Browne K.D. Johnson V.E. Graham D.I. Lee V.M. Trojanowski J.Q. Smith D.H. Multiple proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases accumulate in axons after brain trauma in humans. Exp. Neurol. 2007;208:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts G.W. Allsop D. Bruton C. The occult aftermath of boxing. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1990;53:373–378. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.5.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tokuda T. Ikeda S. Yanagisawa N. Ihara Y. Glenner G.G. Re-examination of ex-boxers' brains using immunohistochemistry with antibodies to amyloid beta-protein and tau protein. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:280–285. doi: 10.1007/BF00308813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geddes J.F. Vowles G.H. Nicoll J.A. Revesz T. Neuronal cytoskeletal changes are an early consequence of repetitive head injury. Acta Neuropathol. 1999;98:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s004010051066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rauramaa T. Pikkarainen M. Englund E. Ince P.G. Jellinger K. Paetau A. Alafuzoff I. TAR-DNA binding protein-43 and alterations in the hippocampus. J. Neural Transm. 2011;118:683–689. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson Y.S. Raby S. Foulds P.G. Robinson A. Thompson J.C. Sikkink S. Yusuf I. Amin H. DuPlessis D. Troakes C. Al-Sarraj S. Sloan C. Esiri M.M. Prasher V.P. Allsop D. Neary D. Pickering-Brown S.M. Snowden J.S. Mann D.M. TDP-43 pathological changes in early onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease, late onset Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome: association with age, hippocampal sclerosis and clinical phenotype. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:703–713. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0879-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham D.I. Gentleman S.M. Nicoll J.A. Royston M.C. McKenzie J.E. Roberts G.W. Mrak R.E. Griffin W.S. Is there a genetic basis for the deposition of beta-amyloid after fatal head injury? Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 1999;19:19–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1006956306099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marklund N. Blennow K. Zetterberg H. Ronne-Engstrom E. Enblad P. Hillered L. Monitoring of brain interstitial total tau and beta amyloid proteins by microdialysis in patients with traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 2009;110:1227–1237. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS08584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brody D.L. Magnoni S. Schwetye K.E. Spinner M.L. Esparza T.J. Stocchetti N. Zipfel G.J. Holtzman D.M. Amyloid-beta dynamics correlate with neurological status in the injured human brain. Science. 2008;321:1221–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1161591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts G.W. Gentleman S.M. Lynch A. Graham D.I. beta A4 amyloid protein deposition in brain after head trauma. Lancet. 1991;338:1422–1423. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92724-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts G.W. Gentleman S.M. Lynch A. Murray L. Landon M. Graham D.I. Beta amyloid protein deposition in the brain after severe head injury: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1994;57:419–425. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.4.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gentleman S.M. Greenberg B.D. Savage M.J. Noori M. Newman S.J. Roberts G.W. Griffin W.S. Graham D.I. A beta 42 is the predominant form of amyloid beta-protein in the brains of short-term survivors of head injury. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1519–1522. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olsson A. Csajbok L. Ost M. Hoglund K. Nylen K. Rosengren L. Nellgard B. Blennow K. Marked increase of beta-amyloid(1–42) and amyloid precursor protein in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid after severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. 2004;251:870–876. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saing T. Dick M. Nelson P.T. Kim R.C. Cribbs D.H. Head E. Frontal cortex neuropathology in dementia pugilistica. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1054–1070. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen X.H. Siman R. Iwata A. Meaney D.F. Trojanowski J.Q. Smith D.H. Long-term accumulation of amyloid-beta, beta-secretase, presenilin-1, and caspase-3 in damaged axons following brain trauma. Am. J. Pathol. 2004;165:357–371. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63303-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiong Y. Peterson P.L. Lee C.P. Alterations in cerebral energy metabolism induced by traumatic brain injury. Neurol. Res. 2001;23:129–138. doi: 10.1179/016164101101198460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park E. Bell J.D. Baker A.J. Traumatic brain injury: can the consequences be stopped? CMAJ. 2008;178:1163–1170. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barkhoudarian G. Hovda D.A. Giza C.C. The molecular pathophysiology of concussive brain injury. Clin. Sports Med. 2011;30:33–48. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.001. vii–iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beach T.G. Sue L.I. Walker D.G. Roher A.E. Lue L. Vedders L. Connor D.J. Sabbagh M.N. Rogers J. The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987–2007. Cell Tissue Bank. 2008;9:229–245. doi: 10.1007/s10561-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabbagh M.N. Cooper K. DeLange J. Stoehr J.D. Thind K. Lahti T. Reisberg B. Sue L. Vedders L. Fleming S.R. Beach T.G. Functional, global and cognitive decline correlates to accumulation of Alzheimer's pathology in MCI and AD. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:280–286. doi: 10.2174/156720510791162340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roher A.E. Esh C. Kokjohn T.A. Kalback W. Luehrs D.C. Seward J.D. Sue L.I. Beach T.G. Circle of Willis atherosclerosis is a risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:2055–2062. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000095973.42032.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maarouf C.L. Daugs I.D. Kokjohn T.A. Walker D.G. Hunter J.M. Kruchowsky J.C. Woltjer R. Kaye J. Castano E.M. Sabbagh M.N. Beach T.G. Roher A.E. Alzheimer's disease and non-demented high pathology control nonagenarians: comparing and contrasting the biochemistry of cognitively successful aging. PLoS. One. 2011;6:e27291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Paesschen W. Revesz T. Duncan J.S. Corpora amylacea in hippocampal sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1997;63:513–515. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McD Anderson R. Opeskin K. Timing of early changes in brain trauma. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 1998;19:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199803000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schenker M. Birch R. Diagnosis of the level of intradural rupture of the rootlets in transaction lesions of the brachial plexus. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2001;83:916–920. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b6.10725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuchna I. Kozlowski P.B. Sequelae of perinatal central nervous system damage after long-term survival. Neuropatol. Pol. 1991;29:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jellinger K.A. Head injury and dementia. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2004;17:719–723. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200412000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graham D.I. Gentleman S.M. Nicoll J.A. Royston M.C. McKenzie J.E. Roberts G.W. Griffin W.S. Altered beta-APP metabolism after head injury and its relationship to the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 1996;66:96–102. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9465-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith D.H. Chen X.H. Iwata A. Graham D.I. Amyloid beta accumulation in axons after traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neurosurg. 2003;98:1072–1077. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.5.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwata N. Tsubuki S. Takaki Y. Watanabe K. Sekiguchi M. Hosoki E. Kawashima-Morishima M. Lee H.J. Hama E. Sekine-Aizawa Y. Saido T.C. Identification of the major Abeta1–42-degrading catabolic pathway in brain parenchyma: suppression leads to biochemical and pathological deposition. Nat. Med. 2000;6:143–150. doi: 10.1038/72237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hersh L.B. Rodgers D.W. Neprilysin and amyloid beta peptide degradation. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:225–231. doi: 10.2174/156720508783954703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen X.H. Johnson V.E. Uryu K. Trojanowski J.Q. Smith D.H. A lack of amyloid beta plaques despite persistent accumulation of amyloid beta in axons of long-term survivors of traumatic brain injury. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson V.E. Stewart W. Graham D.I. Stewart J.E. Praestgaard A.H. Smith D.H. A neprilysin polymorphism and amyloid-beta plaques following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1197–1202. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teasdale G.M. Nicoll J.A. Murray G. Fiddes M. Association of apolipoprotein E polymorphism with outcome after head injury. Lancet. 1997;350:1069–1071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thal D.R. Capetillo-Zarate E. Schultz C. Rub U. Saido T.C. Yamaguchi H. Haass C. Griffin W.S. Del Tredici K. Braak H. Ghebremedhin E. Apolipoprotein E co-localizes with newly formed amyloid beta-protein (Abeta) deposits lacking immunoreactivity against N-terminal epitopes of Abeta in a genotype-dependent manner. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:459–471. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horsburgh K. Cole G.M. Yang F. Savage M.J. Greenberg B.D. Gentleman S.M. Graham D.I. Nicoll J.A. beta-amyloid (Abeta)42(43), abeta42, abeta40 and apoE immunostaining of plaques in fatal head injury. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2000;26:124–132. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2000.026002124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson V.E. Stewart W. Smith D.H. Traumatic brain injury and amyloid-beta pathology: a link to Alzheimer's disease? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nrn2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dekosky S.T. Abrahamson E.E. Ciallella J.R. Paljug W.R. Wisniewski S.R. Clark R.S. Ikonomovic M.D. Association of increased cortical soluble abeta42 levels with diffuse plaques after severe brain injury in humans. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:541–544. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sherriff F.E. Bridges L.R. Gentleman S.M. Sivaloganathan S. Wilson S. Markers of axonal injury in post mortem human brain. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;88:433–439. doi: 10.1007/BF00389495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thornton E. Vink R. Blumbergs P.C. Van Den Heuvel C. Soluble amyloid precursor protein alpha reduces neuronal injury and improves functional outcome following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 2006;1094:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gowing E. Roher A.E. Woods A.S. Cotter R.J. Chaney M. Little S.P. Ball M.J. Chemical characterization of A beta 17–42 peptide, a component of diffuse amyloid deposits of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:10987–10990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kokjohn T.A. Maarouf C.L. Roher A.E. Is Alzheimer's disease amyloidosis the result of a repair mechanism gone astray? Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cullen K.M. Kocsi Z. Stone J. Microvascular pathology in the aging human brain: evidence that senile plaques are sites of microhaemorrhages. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27:1786–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stone J. What initiates the formation of senile plaques? The origin of Alzheimer-like dementias in capillary haemorrhages. Med. Hypotheses. 2008;71:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robinson S.R. Bishop G.M. Abeta as a bioflocculant: implications for the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2002;23:1051–1072. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bishop G.M. Robinson S.R. The amyloid paradox: amyloid-beta-metal complexes can be neurotoxic and neuroprotective. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:448–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu C.W. Liao P.C. Yu L. Wang S.T. Chen S.T. Wu C.M. Kuo Y.M. Hemoglobin promotes Abeta oligomer formation and localizes in neurons and amyloid deposits. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004;17:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chuang J.Y. Lee C.W. Shih Y.H. Yang T. Yu L. Kuo Y.M. Interactions between amyloid-beta and hemoglobin: implications for amyloid plaque formation in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e33120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paris D. Humphrey J. Quadros A. Patel N. Crescentini R. Crawford F. Mullan M. Vasoactive effects of A beta in isolated human cerebrovessels and in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: role of inflammation. Neurol. Res. 2003;25:642–651. doi: 10.1179/016164103101201940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Crawford F. Suo Z. Fang C. Sawar A. Su G. Arendash G. Mullan M. The vasoactivity of A beta peptides. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997;826:35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paris D. Townsend K. Quadros A. Humphrey J. Sun J. Brem S. Wotoczek-Obadia M. DelleDonne A. Patel N. Obregon D.F. Crescentini R. Abdullah L. Coppola D. Rojiani A.M. Crawford F. Sebti S.M. Mullan M. Inhibition of angiogenesis by Abeta peptides. Angiogenesis. 2004;7:75–85. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000037335.17717.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnston H. Boutin H. Allan S.M. Assessing the contribution of inflammation in models of Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011;39:886–890. doi: 10.1042/BST0390886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Breydo L. Wu J.W. Uversky V.N. A-synuclein misfolding and Parkinson's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1822:261–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Desplats P. Lee H.J. Bae E.J. Patrick C. Rockenstein E. Crews L. Spencer B. Masliah E. Lee S.J. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Newell K.L. Boyer P. Gomez-Tortosa E. Hobbs W. Hedley-Whyte E.T. Vonsattel J.P. Hyman B.T. Alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity is present in axonal swellings in neuroaxonal dystrophy and acute traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1999;58:1263–1268. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Su E. Bell M.J. Wisniewski S.R. Adelson P.D. Janesko-Feldman K.L. Salonia R. Clark R.S. Kochanek P.M. Kagan V.E. Bayir H. alpha-Synuclein levels are elevated in cerebrospinal fluid following traumatic brain injury in infants and children: the effect of therapeutic hypothermia. Dev. Neurosci. 2010;32:385–395. doi: 10.1159/000321342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]