Abstract

Polymeric materials have been used in a range of pharmaceutical and biotechnology products for more than 40 years. These materials have evolved from their earlier use as biodegradable products such as resorbable sutures, orthopaedic implants, macroscale and microscale drug delivery systems such as microparticles and wafers used as controlled drug release depots, to multifunctional nanoparticles (NPs) capable of targeting, and controlled release of therapeutic and diagnostic agents. These newer generations of targeted and controlled release polymeric NPs are now engineered to navigate the complex in vivo environment, and incorporate functionalities for achieving target specificity, control of drug concentration and exposure kinetics at the tissue, cell, and subcellular levels. Indeed this optimization of drug pharmacology as aided by careful design of multifunctional NPs can lead to improved drug safety and efficacy, and may be complimentary to drug enhancements that are traditionally achieved by medicinal chemistry. In this regard, polymeric NPs have the potential to result in a highly differentiated new class of therapeutics, distinct from the original active drugs used in their composition, and distinct from first generation NPs that largely facilitated drug formulation. A greater flexibility in the design of drug molecules themselves may also be facilitated following their incorporation into NPs, as drug properties (solubility, metabolism, plasma binding, biodistribution, target tissue accumulation) will no longer be constrained to the same extent by drug chemical composition, but also become in-part the function of the physicochemical properties of the NP. The combination of optimally designed drugs with optimally engineered polymeric NPs opens up the possibility of improved clinical outcomes that may not be achievable with the administration of drugs in their conventional form. In this critical review, we aim to provide insights into the design and development of targeted polymeric NPs and to highlight the challenges associated with the engineering of this novel class of therapeutics, including considerations of NP design optimization, development and biophysicochemical properties. Additionally, we highlight some recent examples from the literature, which demonstrate current trends and novel concepts in both the design and utility of targeted polymeric NPs (444 references).

1. Introduction

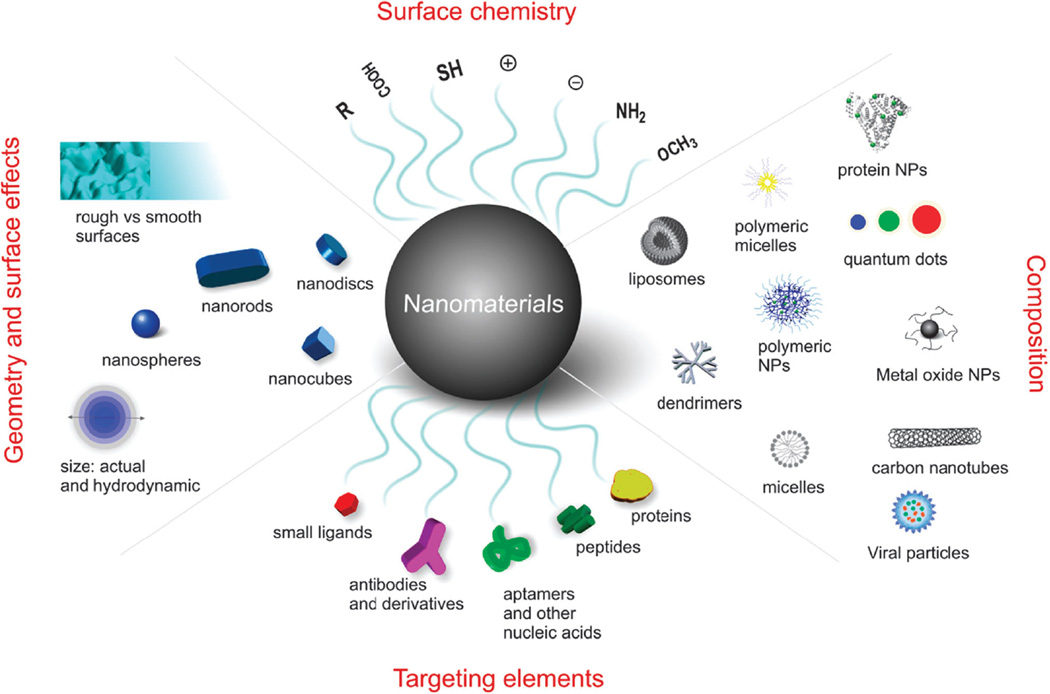

The application of nanotechnology to developing safer and more effective medicines (nanomedicine) is set to substantially influence the landscape of both pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries for decades to come.1–3 This increasing interest in nanomedicine is driven in large part by a fast pace of innovation and emerging successes of nanoparticle (NP) based drug delivery systems.4 Discoveries in the field of nanomedicine have so far proven to be both evolutionary and revolutionary in nature.5 The promotion of interdisciplinary research and the discovery of colloidal mechanisms of drug delivery in the 1960’s and 1970’s led to the development of the earlier nanomedicines; liposomes6 and polymer-drug conjugates.7, 8 The evolution of these NPs was followed by their successful “stealth” rendition by modifying the NP surface using polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymers in order to prevent non-specific binding of NP surfaces to blood components and reduce their rapid uptake and clearance in vivo by the cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), leading to prolonged blood circulation times.21 Following the development of antibody technologies came the ability to potentially increase NP specificity through bioconjugation of affinity ligands, such as antibodies, antibody fragments, peptides, aptamers (Apts), sugars, and small molecules to their surface in order to create targeted NPs.12, 21–23 Fig. 1 presents a timeline for the development of several distinct NPs, which have been either approved for human use or are undergoing clinical trials including: liposome, albumin, and polymeric NPs. In addition to these, polymer coated iron oxide NPs have also been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents.

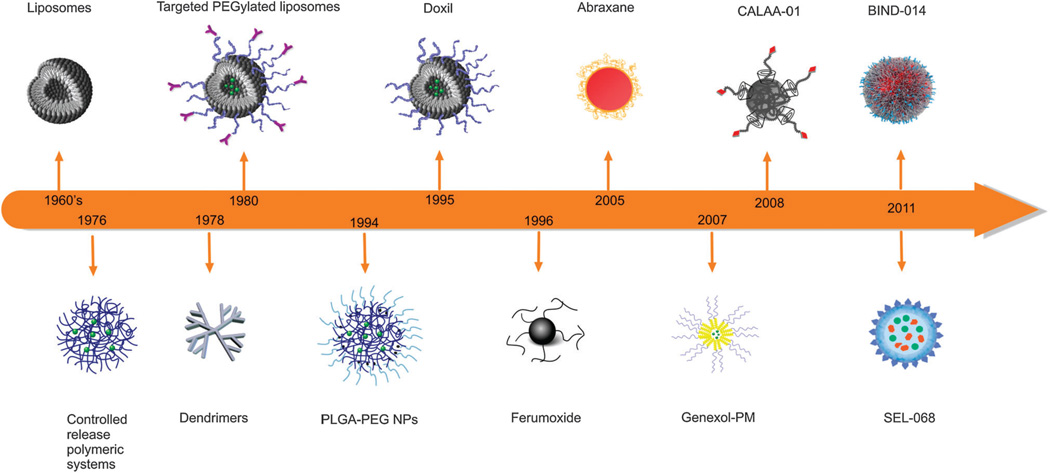

Fig. 1.

Time line of clinical stage nanomedicine firsts. Liposomes,9 controlled release polymeric systems for macromolecules,10 dendrimers,11 targeted-PEGylated liposomes,12 first FDA approved liposome (DOXIL),13 long circulating poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-polyethyleneglycol (PLGA-PEG) NPs,14 iron oxide MRI contrast agent NP (Ferumoxide),15 protein based drug delivery system (Abraxane; nab technologyt),16 polymeric micelle NP (Genexol-PM),17 targeted cyclodextrin-polymer hybrid NP (CALAA-01),18 targeted polymeric NP (BIND-014; Accurint™ Technology),19 fully integrated polymeric nanoparticle vaccines (SEL-068, t SVPt™ Technology).20

Potential advantages of therapeutic NPs include: (1) the ability to improve the pharmaceutical and pharmacological properties of drugs, potentially without the need to alter drug molecules, (2) enhancement of therapeutic efficacy by targeted delivery of drugs in a tissue- or cell-specific manner, (3) delivery of drugs across a range of biological barriers including epithelial and endothelial, (4) delivery of drugs to intracellular sites of action, (5) the ability to deliver multiple types of therapeutics with potentially different physicochemical properties, (6) the ability to deliver a combination of imaging and therapeutic agents for real-time monitoring of therapeutic efficacy and, (7) possibilities to develop highly differentiated therapeutics protected by a unique set of intellectual properties.7, 24

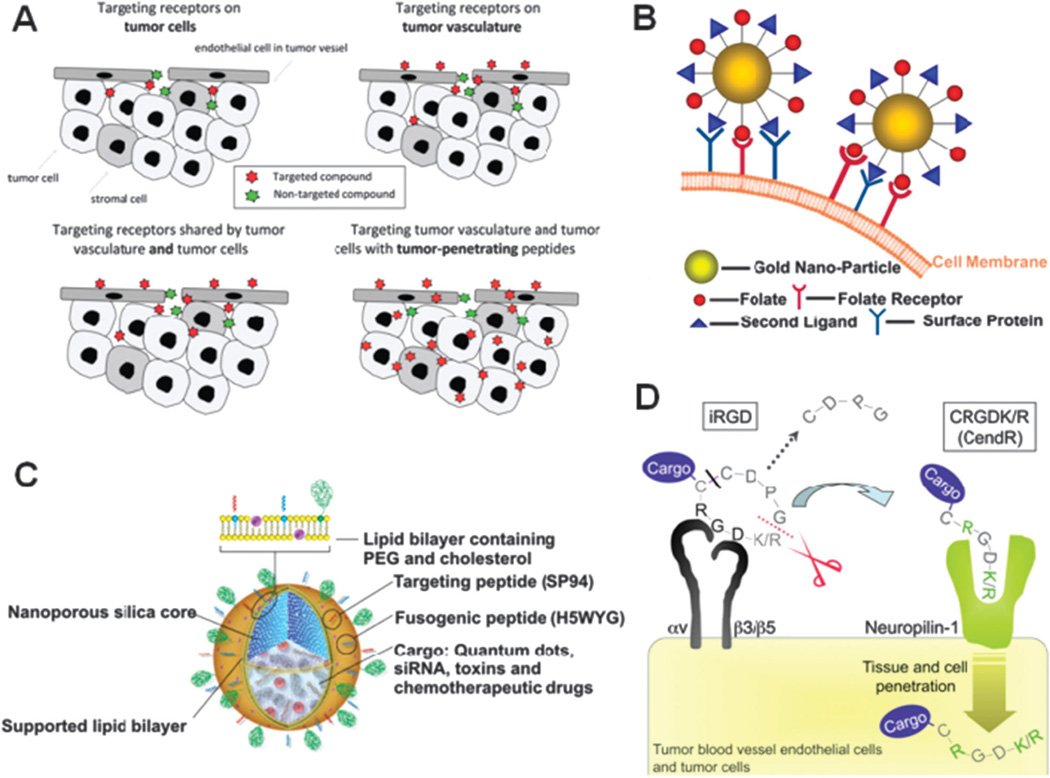

With respect to NP research, targeting refers to differential spatial localization and describes the intentional homing of NPs to active sites in disease conditions and is distinct from molecularly targeted drugs. While molecularly targeted drugs preferentially modulate the function of proteins abnormally expressed or activated in a disease state, they are not designed for spatial localization and indiscriminately distribute within the body, contributing to off-target adverse effects.25 This differential spatial localization of NPs encompasses two different approaches, which are “passive” or “active” targeting. Passive targeting refers to the preferential accumulation of NPs (bearing no affinity ligands) at active sites and is directly related to the inherent biophysicochemical properties of the NP (size, shape, charge and flexibility etc.). These biophysicochemical properties may also impede the effective concentration of NPs at active sites due to competitive events manifested by the MPS system leading to the sequestration of NPs, thereby limiting their systemic concentration and potential to extravasate into target tissues or bind to target cell populations.26 Active targeting is a term used to describe the mode of action of NPs with surface modification to incorporate affinity ligands with specificity to disease tissues and cells. These NPs differentially bind to target molecules as a result of the binding properties of the ligands on the NP surface (passive and active targeting are further described in section 3). Although more than 30 years have gone by since the implementation of the concept of targeted NPs, only a handful of these targeted NPs have reached clinical development and none have been clinically approved (Table 1).29–31 Limiting factors such as: (1) insufficient understanding of events at the nano-bio interface both in vitro and in vivo, (2) inadequate knowledge of the fate of NPs at the body, organ, and cellular levels, (3) difficulty in achieving reproducible and controlled synthesis of NPs at scales suitable for clinical development and commercialization, and, (4) lack of technologies enabling screening of a large number of NP candidates under biologically relevant conditions that could be reliably correlated to clinical performance are some possible explanations for the slow clinical translation of these nanomedicines. Though a vast array ofmaterials have been used to formulate NPs for drug delivery, including polymers, lipids, carbon, silica oxides, metal oxides and semiconductor nanocrystals,32 this review focuses specifically on targeted controlled release polymeric NPs for therapeutic applications. This focus stems from the potential impact of polymers on medicine as evidenced through previous clinical successes of polymers as biomedical materials,2, 10, 14, 33 as well as their potential as targeted therapeutic NPs.34

Table 1.

Targeted NPs in clinical development

| Identity | Ligand | Target | Nanoparticle | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) |

Indication | Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIND-014 | Small molecule | PSMAa | Polymeric | Docetaxel | Solid tumours | Phase I | 19 |

| SEL-068 | Small molecule | Antigen presenting cells | Polymeric | Nicotine antigen T-helper cell peptide, TLRb agonist |

Smoking cessation and relapse prevention vaccine |

Phase I | 20 |

| CALAA-01 | Transferrin | Transferrin receptor | Polymeric | siRNA | Solid tumours | Phase I | 28 |

| MBP-426 | Transferrin | Transferrin receptor | Liposome | Oxaliplatin | Gastric, esophageal, gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma |

Phase Ib/II | 29 |

| MCC-465 | Antibody fragment | Tumour antigen | Liposome | Doxorubicin | Metastatic stomach cancer |

Phase I | 30 |

| SGT53-01 | Antibody fragment | Transferrin receptor | Liposome | p53 gene | Solid tumours | Phase Ib | 31 |

PSMA: prostate specific membrane antigen.

TLR: Toll-Like Receptor agonist.

1.1 Polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: drug delivery vehicles or a novel class of therapeutics?

The first generation clinically approved NP drug delivery technologies (liposomes, micelles, proteins etc.) lacked controlled release and active targeting properties, and were able to generally improve the safety and efficacy of the active drugs they carried. Among these first generation NPs, DOXIL, Abraxane and Genexol-PM were developed for cancer therapy. DOXIL was the first FDA approved liposome nanomedicine to reach clinical approval in 1995 for AIDS related Kaposi’s syndrome.35 By encapsulating doxorubicin (Dox) within liposomes, DOXIL changed the pharmacokinetics (PK) and biodistribution (BD) of Dox, facilitating a longer circulation half-life and therefore higher tumour dose accumulation of this drug. Although the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of DOXIL (50 mg m−2 every 4 weeks) was lower than that of standard Dox (60 mg m−2 every 3 weeks) and DOXIL exhibited a new toxicity of hand-foot syndrome (palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia), however, in this case the therapeutic index of Dox was enhanced. This enhancement was due to the fact that the cardiotoxicity associated with the free drug (Dox) was reduced and efficacy was demonstrated in taxane/platinum-resistant ovarian cancers.36 Despite the clinical validation of liposome technology, this class of NPs generally lack controlled release properties that can control the kinetics of drug exposure at the target tissue, and liposomes are also comparatively less stable as compared to polymeric NPs (discussed further in section 2).37, 38 The approval of Abraxane (nab-paclitaxel) in 2005 by the FDA, which is based on the NP albumin-bound (nab) platform, led to the second class of therapeutic NPs to be clinically validated.39 In comparison to paclitaxel (Ptxl) formulated with Cremophor EL (Taxol), Abraxane demonstrated significantly higher tumour response rates (33% vs. 19%) and longer times to tumour progression (23.0 vs. 16.9 weeks) among metastatic breast cancer patients who did not respond to combination therapy.40 Upon administration of Abraxane, the NP formulation rapidly dissociates into its constituents of albumin and Ptxl molecules and therefore does not materially impact the circulation half-life or BD profile of Ptxl.41 However, the nab platform significantly improved the MTD of Ptxl (260 mg m−2 vs. 175 mg m−2 for Taxol every 3 weeks) by removing the need for the use of the toxic excipient—Cremophor EL.16, 42 Therefore, nab-technology does not dramatically improve drug PK or BD, and the utility of this technology is largely limited to improving the therapeutic index of hydrophobic drugs that are currently formulated with poorly tolerated solvents. Furthermore, not all validated drugs can bind to albumin which further limits the utility of the nab-technology. Genexol-PM (a Ptxl loaded polymeric micelle) was approved in Korea in 2007. This polymeric micelle technology also removed the need for the use of Cremophor EL leading to an increase of Ptxl MTD up to 300 mg m−2 every 3 weeks for breast cancer treatment.39 Genexol-PM is currently in phase II clinical development in the USA.17, 43

Each clinically validated NP platform has made sufficient improvement to drug safety and efficacy for successful approval, yet each platform has unique limitations, and most clinicians would argue that none have made a marked improvement in clinical outcomes. Today there are nearly 250 nanomedicine products in various stages of preclinical and clinical development.44 For a NP platform to maximally improve drug pharmaceutical and pharmacological properties resulting in a highly differentiated new therapeutic with superior safety and efficacy, in most cases it will need to predictably change drug PK, BD, and tissue exposure kinetics-in a tunable and predictable manner. The successful development of such NP platforms is expected to create an entirely novel class of therapeutic NPs. The combination of one or more drugs with controlled release polymeric biomaterials for tuneable drug exposure, and molecular targeting for differential delivery has the potential to create novel therapeutic NPs for a range of medical applications.18, 45, 46 These efforts may yield NPs with highly differentiated drug pharmacology and efficacy, analogous to creating novel drugs through conventional medicinal chemistry. Polymeric NPs have the capability to: (1) release drugs at an experimentally predetermined rate over a prolonged period of time, (2) release drugs preferentially at target sites with the possibility of controlled release rates, (3) maintain drug concentrations within therapeutically appropriate ranges in circulation and within tissues and; (4) protect drugs (small molecules, proteins, nucleic acids or peptides) from hepatic inactivation, enzymatic degradation and rapid clearance in vivo. Polymeric NPs encapsulate various drugs and release them in a regulated manner via diffusion of the drug molecules through the polymer matrix or via differential surface and bulk erosion rates of the particles. The systematic design of these systems allows for the fine-tuning and optimization of the exact polymeric NP composition that can lead to increased efficacy in vivo. By careful selection of the composition of polymeric NPs resulting in optimal PK/BD, the total amount of drug and the duration of drug exposure in target tissue can be altered and improved substantially. Additionally, the incorporation of targeting ligands on NPs can lead to their increased uptake and their active agents, leading to enhanced therapeutic outcomes. In this regard, targeted polymeric NPs have the potential to be highly differentiated therapeutics, distinct from the original active agents used in their composition and distinct from first generation NPs that largely facilitated drug formulation. Additionally, the higher intracellular concentration of drugs delivered by targeted polymeric NPs can potentially maximize therapeutic efficacy by overcoming drug resistance mediated by multidrug resistance (MDR) proteins.47–49 The sub-cellular targeting of NPs can result in highly specific delivery of drug payloads to intracellular targets.50 Several MDR transporters exist, of which the p-glycoprotein, human multidrug resistance protein (MRP1) and the breast cancer resistance protein have been widely studied.51 Drug delivery using targeted polymeric NPs can result in continued release of drugs at a high concentration directly within the cell, potentially overcoming drug efflux.49 Several studies in drug-resistant mouse models have demonstrated an enhanced antitumour activity for targeted NPs (e.g. folate-receptor targeted polymeric micelles, transferrin-conjugated Ptxl NPs etc.),52–54 in comparison to their non-targeted equivalents which were shown to be not as effective. This review focuses on the development of targeted polymeric NPs and aims to highlight and discuss benefits and challenges of this novel class of therapeutics.

2. Controlled release polymeric NPs from discovery to the clinic

Controlled release systems generally refer to technologies or biomaterials that can be engineered to release drugs at predetermined and/or tuneable rates, or in response to external stimuli and triggers. Polymeric materials have emerged as a major class of controlled release systems since their unique physicochemical, synthetic, biocompatibility, and degradation properties can be readily manipulated using well-established techniques.55–57 Additionally, polymeric NP systems may be able to overcome the limitations of lipidic NPs such as liposomes. For example some key limitations of liposomes include: their propensity to burst release cargo in vivo, a lack of compatibility with various active agents, a limited drug loading volume, the oxidation of liposomal phospholipids, and poor shelf-life stability.3, 18, 58 In contrast, polymeric drug delivery systems are comparably stable in vivo, have high drug loading capacities, and can employ both controlled or triggered release of drugs.59 Due to these properties, polymeric nanomaterials are well positioned to continue to provide a diversity of solutions to a range of problems in medicine. In this section, we will provide an overview of selected developments that have led the way for the clinical translation of controlled release polymeric NPs.60

Polymers have been recognized for their potential in drug delivery applications since the 1960’s.61 However, at that time, many biomaterials were simply repurposed from industrial or household applications and therefore had inherent limitations. This began to change in the 1970’s, particularly after seminal work by Langer and Folkman in 1976 which demonstrated that controlled release of macromolecules from biodegradable polymers in a temporal manner was possible.10 A variety of macromolecules, which previously could not have been used as drugs due to PK or toxicity concerns could now be encapsulated into slow-releasing polymeric drug reservoirs and thereby developed into therapeutics suitable for use in humans. Over the past 4 decades controlled release polymer technology has impacted virtually every branch of medicine including ophthalmology, pulmonary, pain medicine, endocrinology, cardiology, orthopaedics, immunology, neurology and dentistry.62 The annual worldwide market of controlled release polymer systems which extends beyond drug delivery is now estimated at $60 billion and these systems are used by over 100 million people each year.62

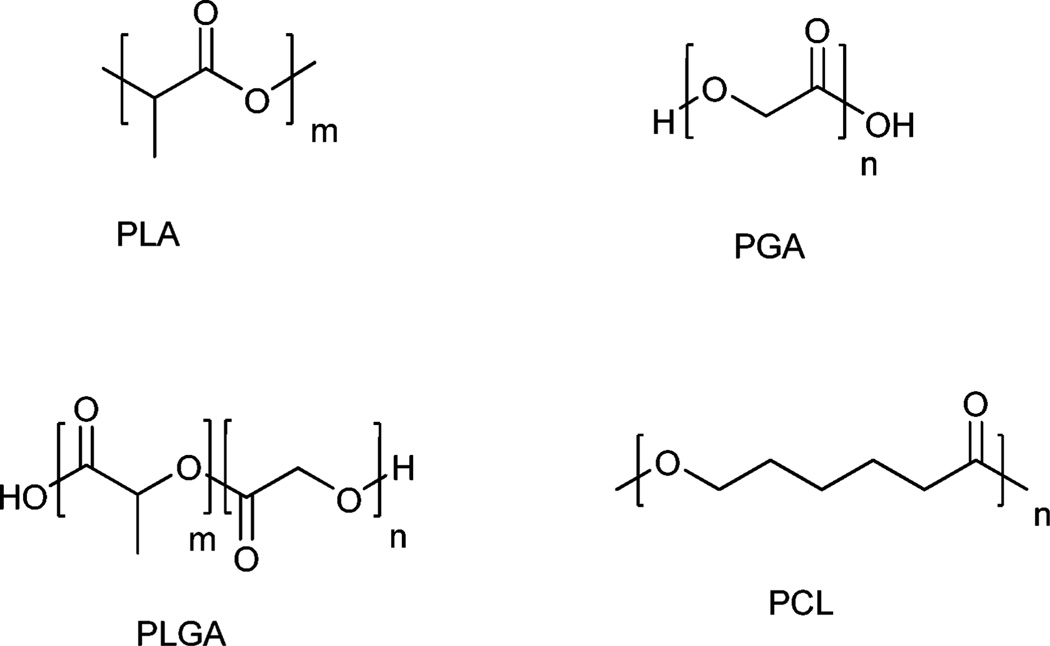

Today, the most commonly used polymers for controlled drug release applications include poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(glutamic acid) (PGA), poly(caprolactone) (PCL), N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-methacrylate copolymers (HPMA), and poly(amino acids).63 In particular, PLGA, PGA and PLA (Fig. 2) have been widely used in an impressive number of controlled release products, particularly due to their favourable biocompatibility and biodegradability properties. These stem, in part, from simple clearance of the polymer matrix by the body’s homeostatic metabolic pathways.64

Fig. 2.

Common biodegradable polymers utilized in controlled-release drug delivery applications. Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(glutamic acid) (PGA), poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolide) (PLGA), poly(caprolactone) (PCL).

Following the earlier work of Langer and Folkman, interest began to grow in developing slow releasing drug depots including surgical implants and injectable microparticles. The focus of these controlled release systems was principally to enable the potential use of macromolecules that had short half-lives as therapeutics, to enhance patient compliance, to improve drug efficacy and reduce side effects by delivering agents locally, and to simplify dosing in cases where prolonged drug exposure was necessary.65 Years of preclinical work done in parallel and in collaboration by several groups in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s ultimately led to a number of clinical successes. For example, Zoladex, a PLGA copolymer impregnated with Goserelin acetate for treating breast and prostate cancers was approved by the FDA in 1998. It was designed to be injected subcutaneously so that the active agent could be released slowly into systemic circulation and reach its target sites.66 The same year Lupron Depot, a PLGA microsphere formulation of leuprolide acetate, was approved by the FDA to treat advanced prostate cancers.67 Among other notable controlled release formulations that followed is Gliadel, a biodegradable Polifeprosan 20 carmustine-embedded wafer for the treatment of gliomas that became the first new treatment for gliomas in 20 years on its approval in 1996,68 and Atridox, a polylactide and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) polymer blend containing doxycycline hyclate for subgingival delivery, which was FDA approved in 1998 to treat periodontal disease.69 Other controlled release formulations of note include Sandostatin LAR, a PLGA slow release formulation of octreotide acetate for tumour control in neuroendocrine disorders approved in 1998.70 Trelstar Depot, a PLGA based microparticle formulation of triptorelin pamoatea used for prostate cancer and other indications, was FDA approved in 2000.71 The evolving ability to manufacture and control the assembly of polymers to nanoscale dimensions combined with growing interest in applying nanotechnology to medicine drove the downsizing of controlled release drug depots from macro or micro-scale products to the nano-scale.72 Indeed the clinical success of these initial formulations both validated the concept of controlled release from polymers and set the stage for the coming of the polymeric NP era.

3. NP differential spatial localization; by passive or active means

3.1 Passive targeting

Currently, all of the clinically validated therapeutic and imaging NPs are considered passively targeted first generation nanomedicines. 7 The majority of these NPs exhibit prolonged circulation times in vivo and accumulate at particular sites simply due to blood hemodynamic forces and diffusive mechanisms. Passive targeting is widely exploited in oncology applications since, in particular, tumours facilitate accumulation of NPs through the widely reported “enhanced permeation and retention” (EPR) effect. This was a milestone discovery made by Maeda et al., who in the 1980’s demonstrated the principle of passive targeting of colloidal particles to tumours.73 In their initial studies, significantly higher concentrations of the cytotoxic drug neocarzinostatin was discovered in tumour tissue post administration of the polymer-drug conjugate poly(styreneco-maleic acid)-neocarzinostatin (SMANCS), in comparison to control experiments where the drug was administered in its free form.73 This led Maeda et al. to postulate that the enhanced accumulation of the colloidal particles in the tumour was attributed to the structural features of the tumour vasculature, an observation, which was termed the EPR effect.74 The EPR effect has been observed with a wide range of macromolecular agents such as proteins; including immunoglobulin G (IgG), drug-polymer conjugates, micelles, liposomes, polymeric NPs and many other types of NPs.63, 75–77

Tumour tissue is highly heterogeneous and is perfused by an aberrant and leaky microvasculature. Indeed, tumour microvasculature has been shown to be characterized by excessive branching, chaotic structures, enlarged inter-endothelial gaps with associated break-down of tight junctions between endothelial cells, and a disrupted basement membrane.78 These large gaps between endothelial cells facilitate the extravasation of particulate material from the surrounding vessels into the tumour.79 In addition to large leaky endothelial gaps, an impaired lymphatic drainage system further entraps macromolecular particles and delays their clearance. EPR is most effective for colloidal material of >40 kDa and can occur even in the absence of targeting ligands on NPs.73 The size cut-off thresholds between endothelial cells varies between tumour type, though permeability and extravasation of NPs up to 400 nm through endothelial gaps has been observed (in mouse xenograft models of human cancers).80 In addition to abnormal architecture, tumour blood vessels also have impaired receptors for angiotensin II which controls vessel constriction.81 Solid tumours often produce large concentrations of vascular permeability factors as a result of rapidly growing tumour cells that require an increased supply of nutrients and oxygen. There are a number of vascular mediators which facilitate the EPR effect and these include; bradykinin, nitric oxide (NO), peroxynitrite (ONOO−), prostaglandins, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, vascular endothelial permeability factor (VEGF) and numerous other cytokines.82 These factors are all indeed mediators of inflammatory processes and as such it is not surprising that the EPR effect may also manifest in other inflammatory scenarios such as arthritis, infection and advanced atherosclerotic plaques.73, 83

Currently the observations of EPR are the main premise for the design of tumour specific nanomedicines for drug delivery or imaging applications, however there are a number of caveats that need to be considered. For instance, the fact that large tumours show pathophysiological heterogeneity is a problem, as NPs cannot effectively accumulate throughout the tumour, in particular, the central regions of metastatic tumours do not exhibit the EPR effect which leads to lowered accumulation of colloidal NPs.84 Furthermore, the degree of vascular permeability which ultimately leads to heterogeneity between tumour models and variable tumour microenvironments can affect the cut-off size for NP accumulation in tumours, restricting their effective penetration range, and additionally, also accounts for the lack of observable EPR effects in certain tumour types.85, 86 Moreover, the negative pressure gradient present within the tumour interstitium can substantially limit the convection of NPs from the intravascular to the extravascular space within tumours, regardless of the presence of leaky vasculature.85, 87 Since interstitial pressure is higher at the tumour core and diminishes outwards towards the tumour periphery rim, this can cause NPs to flow outwards from the tumour leading to a loss of effective drug dose within tumours. To circumvent these problems targeted NPs can be used for more efficient tumour or target tissue retention and cellular uptake, resulting in improved efficacy. Additionally, methods of elevating blood pressure or introducing NO-secreting compounds have been investigated by means of administering adjuvants in addition to NP injections.82, 84 For example, VEGF can increase vascular permeability, and was shown to enhance the extravasation of NPs across tumour vasculature when co-administered with liposome NPs.88 In addition to bradykinin, NO and prostaglandins that are factors involved in the regulation of vascular permeability, the administration of a number of kinase inhibitors has also led to an enhanced EPR effect.89 The coadministration of a transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) receptor inhibitor led to an enhancement of EPR mediated accumulation of both liposomal and micelle NPs, which was a direct result of reduction of pericyte coverage on tumour neovasculature.89 By enhancing vascular permeability and lowering the pressure difference by raising blood pressure, the overall “leakiness” of tumour vessels and therefore passive accumulation of NPs can be increased.

The majority of passively targeted NPs possess a surface coated with PEG polymer for biocompatibility; however, this highly hydrophilic surface does not result in optimal endocytic uptake by cancer cells within the tumour. This problem which has been referred to by some as the “PEG dilemma”90, 91 has been suggested to hamper efficient drug delivery in tumours as passively targeted NPs end up releasing their therapeutic payload into the tumour milieu rather than within cancer cells. However, in the case of cytotoxic drugs—many have been shown to have longer elimination half-lives in tumours vs. normal tissue. Therefore, the delivery of higher amounts of drugs to tumours can lead to longer durations of drug exposure at higher concentrations and enhanced efficacy.92–95 For example, docetaxel (Dtxl) has an elimination half-life of 2.2–4.5 h in normal tissue and 22 h in tumours, demonstrating long tumour site retention relative to non-tumoural tissues.96 For drugs that are not readily retained in tumours or macromolecular drugs that are not readily taken up by cancer cells, then extracellular drug release may be less effective at maintaining a differentially high tumour drug concentration over an extended period of time. This problem is further compounded with NP systems that lack controlled drug release properties. For example, micelle NPs can demonstrate a very rapid “burst” release post administration (releasing up to 50% of their encapsulated drug within 30 min) leading to premature drug release prior to effective EPR mediated tumour accumulation.82 Similar problems exist for liposome based NPs, which can lead to either very slow or fast release of their therapeutic content. Furthermore, the administration of PEGylated liposomes has led to the production of PEG-specific antibodies,97 causing the rapid clearance of a further administered dose—leading to an accelerated blood clearance (ABC) phenomena—which further diminishes effective drug concentrations at tumour sites, but can be rectified by careful tuning of dose (discussed in more detail in section 3.2).98

Extensive efforts in forming PEGylated block copolymers have ultimately resulted in the clinical translation of a number of passively targeted polymeric NPs including; SP1049C,99 NK911,100 Genexol-PM and others, which are now in early phase clinical trials for treating a variety of cancers.17 In general, these NPs are PEGylated polymeric micelle formulations. Polymer micelles are polymeric NPs that form from the self assembly of amphiphilic polymers at concentrations above the critical micelle concentration (CMC), yielding NPs which can encapsulate poorly water soluble drugs.101 SP1049C is a pluronic polymeric micelle NP that is composed of a Dox-entrapping hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic polymer, and is currently undergoing phase II studies in patients with metastatic cancer of the esophagus and esophageal junction that have been refractive to standard chemotherapy treatments.99 SP1049C was observed to be effective in bypassing p-glycoprotein-mediated drug resistance.102 In this study, patients were treated with a single dose of SP1049C, 75 mg m−2 (Dox) given as an intravenous infusion every 3 weeks.99 The results of this study and preclinical studies demonstrated superior anti-tumour efficacy for SP1049C when compared to free Dox administration.99

Two other passively targeted polymeric NPs are NK911, a micellar NP comprising PEG, Dox and poly(aspartic acid), and Genexol-PM, which is a Ptxl-encapsulated PEG-PLA micelle formulation currently in phase II development for various cancers.17, 43, 103 As mentioned previously, Genexol-PM does not require the use of Cremphor EL, and has therefore led to an increase in Ptxl MTD for breast cancer therapy.42, 104 Additionally, Genexol-PM administration demonstrated increased treatment response rates when given to patients who were not responsive to standard taxane therapy with Ptxl/carboplatin therapies, further suggesting improved outcomes for MDR cases. Xyotax (Ptxl-poliglumex), also a passively targeted polymeric NP in which Ptxl is conjugated to poly(l-glutamic acid), was shown to preferentially target ovarian tumours.105, 106 Another example of a passively targeted polymeric NP undergoing phase trials is IT-101, a camptothecin-cyclodextrin polymer conjugate that has shown prolonged circulation times and slow drug release kinetics in vivo, both in pre-clinical and clinical studies.107 These first generation polymeric NPs have so far demonstrated activity against tumours that have been resistant to standard therapies, and show promise in stabilizing disease in patients. The containment of drugs within these NPs leads to significantly reduced off target effects, which can lead to wider therapeutic windows and lower systemic toxicities. Passive targeting strategies are not without limitations and therefore considerable efforts are now underway to investigate actively targeted NPs that can further retain NPs at active sites. Currently there are three targeted polymeric NPs undergoing clinical trials which include: BIND-014, CALAA-01 and SEL-068; these targeted clinical stage NPs will be discussed further in section 3.3.

3.1.1 Long circulating polymeric NPs

Following the discovery of themany inherent advantages for the use of polymericmaterials in drug delivery applications, a landmark paper by Langer and colleagues in 1994 demonstrated that forming diblock copolymers of controlled release polymers with PEG could dramatically increase the circulation half-lives of polymeric NPs.14 Since then, there have been a myriad of PEGylated polymericNPs reported in the literature with the benefits of PEGylation demonstrated across a broad range of polymer molecular architectures and macromolecular assemblies.108–110 In addition to this extensive preclinical work, PEG has been validated clinically in many different applications, and is currently listed as “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) by the FDA, making it particularly attractive to translational researchers.109 The success of PEG in transforming polymeric NP drug delivery has not been without its challenges however, some of which remain ongoing areas of investigation. For example, the induction of the aforementioned ABC phenomena by PEGylated liposomes has been shown to be influenced by NP size, surface charge, constituents, and time period prior to second dose, and has been observed with other types of NPs, and even been shown to be dependent on NP therapeutic load and type.111–114 However, observations of ABC phenomena have been conflicting in the literature so far as the induction of PEG specific antibodies have been observed in some cases and not in others—therefore given the variable design and composition of NPs, these effects should be investigated on a case-by-case basis.112, 115, 116 A number of studies have now demonstrated that PEG appears to activate complement in a concentration and molecular weight dependent manner, through classical (C1q dependent), lectin, or alternative pathways.117 While PEG is capable of both activating complement and eliciting anti-PEG antibody responses, the manner and extent of these immune responses can be modulated. Further, it has been shown that modifying the density of PEG on a NP surface alters the complement activation pathway, perhaps by altering the conformation of the PEG chains on the NP surface.118 These data suggest that surface optimization of PEG density and molecular weight will be critical to avoid unwanted immune (non-IgE) hypersensitivity reactions. In addition to complement activation, as mentioned previously, PEGylated liposomes have been shown to elicit immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies in a number of reports, leading to ABC phenomena post-repeat dosing in a short time interval following initial dose administration.98 Production of short term anti-PEG IgM appears to be dependent on the species tested, dose, PEG density, NP charge, and type of drug encapsulated. It is noted, that to attenuate the anti-PEG immune response, it appears important to tune the dose, shorten the PEG molecular weight, increase the density of PEG on the NP surface, tune NP surface charge close to neutral, and/or encapsulate an agent that attenuates macrophage function, such as Dox.98 The clinical significance of these reports in terms of affecting PEGylated NP drug carriers has not been critically evaluated, though further preclinical and clinical data (Table 1) will at least provide an interim answer. At this point, with known methods to attenuate the anti-PEG immune response, and the well-established clinical success of the DOXIL (PEGylated liposome) and many other clinically validated PEGylated proteins, one can conclude that the anti-PEG immune response is not an intractable issue for polymeric NP carriers. Furthermore, alternatives to PEG are currently being developed, including new polymers or zwitterionic surfaces that are ultra-low fouling in nature.119 The preclinical data for these systems is encouraging, and their further development and study in the context of NP drug delivery is widely anticipated.109, 120, 121

In order to achieve effective EPR mediated targeting, NPs must have long-circulating half-lives that facilitate more opportunities for the passage of NPs from the systemic circulation into the disordered and permeable regions of tumour vasculature. As mentioned previously, passive targeting strategies are not without limitations and therefore considerable efforts are now underway to investigate actively targeted NPs that can further retain NPs at active sites. Targeted NPs facilitate receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME), releasing therapeutic agents in a more effective manner once inside target cell populations,122, 123 which can significantly increase drug efficacy.51, 124, 125

3.2 Active targeting

Active targeting involves the use of affinity ligands to direct the binding of NPs to antigens, differentially overexpressed on the plasma membrane of diseased cells or to the extra-cellular matrix proteins that are differentially overexpressed in the disease tissue. The first reports of targeted NPs date back to 1980’s and involved the surface modification of liposomes with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that recognized antigens on the target cells.22, 23, 126 There are 30 mAbs approved for clinical use to date.127 Muromonab-CD3 (OKT3, immunosuppressive agent) was the first antibody to be approved in 1986.128 Since then a myriad of antibody platforms have been developed including murine, chimeric, humanized and human mAbs.51 For example, the chimeric mAb rituximab (Rituxan), which binds to the CD20 antigen, was approved for the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1997.129 The humanized mAb trastuzumab (Herceptin) which binds to the HER2/neu antigen was approved for the treatment of breast cancer in 1998.130 Stemming from the success of mAbs, several other classes of binding ligands were developed against many target antigens, including antibody mimetics, peptides, nucleic acid ligands and small molecules (see section 5). Many of these ligands have been conjugated to radioisotopes or drug molecules to create more effective targeted imaging and therapeutic modalities.131–133 Subsequently, many of these ligands were also conjugated to the surface of NPs in order to achieve antigen-specific active targeting.134 In contrast to ligand-drug conjugates which typically carry 1–8 drug molecules, ligand targeted NPs may carry up to 103 to 104 drug molecules, allowing for potentially a higher amount of drug delivery per bio-recognition or binding event.

Actively targeted NPs can be utilized in applications where drug release is either extracellular or intracellular. Therapies that act on intracellular sites of action are most effectively delivered with targeted NPs.3, 135 Actively targeted NPs may be internalized via clathrin-dependent endocytosis pathways, caveolin-assisted, cell adhesion molecule directed, or lipid raft associated mechanisms, leading to endosome formation, which ultimately leads to lysosomes.136 For hydrophobic small molecule drugs that can readily permeate through the lipid bilayer of the endosomal membrane, drug release within the endosome will result in permeation within the intracellular compartments. For delivery of bioactive macromolecules such as nucleic acids (DNA, siRNA, miRNA) or charged hydrophilic small molecules that are relatively impermeable to the endosomal membrane, the NPs need to escape the endosome prior to fusion with lysosomes if NPs are to reach their desired subcellular compartments.137 Many efforts have led to the investigation of mechanisms that lead to endosomal escape based on pH buffering, osmotic swelling leading to endosome bursting or endosomal membrane destabilization.138, 139 Ligand mediated cell internalization can result in enhanced therapeutic benefits as compared to equivalent non-targeted NPs.124, 140 Experiments comparing targeted and non-targeted NPs have confirmed that the primary role of the targeting ligand is to enhance cellular uptake into target cells.141, 142 For example, accumulation of siRNA-loaded NPs at tumour sites is largely a function of effective EPR via passive targeting; however, cellular internalization and effective gene silencing are largely a function of targeting ligand where targetedNPs are significantly more efficacious as compared to equivalent non-targeted NPs.143, 144 This behaviour suggests that the colloidal properties of NPs determine their biodistribution, whereas the targeting ligand serves to facilitate and enhance cellular uptake at targeted sites.145

Ligand mediated targeting is also beneficial in the case of vascular endothelial targeting for both oncology and cardiovascular applications, and the identification of high affinity ligands for this purpose is an active area of research.146 Recent studies have shown that small peptide targeted polymeric NPs showed substantial accumulation to injured vasculature following angioplasty compared to non-targeted NPs.147 Interest in the use of short peptides as targeting ligands has increased. In comparison to larger mAb’s peptide ligands have the advantage of being (i) smaller in size, (ii) less immunogenic, (iii) more stable; and (iv) easier to manufacture.148 Peptides however, have relatively lower affinity for their target site, and this deficiency is in-part mitigated through ligand avidity which is achieved by incorporating multiple peptides on the NP surface.149 The establishment of a wide range of phage display libraries and screening technologies has resulted in isolation of peptide ligands against many important targets (targeting ligands are discussed further in section 5).150–152

While the potential benefit of ligand-mediated NP targeting is clear, this technology has not resulted in a clinically validated product so far. Within the 32 years since the first description of targeted NPs, only six targeted NPs have progressed to clinical trials (Table 1). From these six NPs, three are targeted polymeric NPs and three are targeted liposomes. MCC-465 was the first of these to be developed and consists of liposome encapsulated Dox, with a surface decorated with both PEG and dimers of antigen-binding fragments (F(ab′)2) for immune shielding and targeting respectively.213 The F(ab′)2 used in the development of this NP is a fragment of the human mAb, GAH which has shown affinity to >90% of human stomach cancer cells.213 Additionally, antibody fragments may be preferred for certain applications since they retain the high affinity and specificity of antibodies but are smaller in size and therefore potentially less immunogenic.51 MCC-456 was shown to exhibit significant antitumour response against GAH-positive xenografts resulting in up to 80% reduction in tumour mass in comparison to controls.214 Phase I trials with MCC-465 were carried out in order to determine the MTD and further dosing regimens for Phase II analysis. In this study patients with metastatic cancer or recurrent stomach cancer were administered 6.5 mg m−2 of MCC-465 as a 1 h infusion every 3 weeks for up to 6 treatment cycles. It was concluded that MCC-465 was well tolerated and similar pharmacokinetic outcomes were observed as compared to DOXIL. However, MCC-465 does not appear to have progressed through clinical development after phase I completion.

SGT53-01 is a transferrin receptor (TfR)-targeted liposome designed to carry the p53 tumour suppressor gene to cancer cells.215 SGT53-01 targets the TfR on the surface of cancer cells using single-chain antibody fragments (TfRscFv) and results in the expression of p53 gene in the targeted cancer cells. Pre-clinical studies have indicated that SGT53-01 could sensitize tumours to the effects of radiation and chemotherapy.215 SGT53-01 is currently undergoing phase I clinical trials in combination with Dox for treatment of solid tumours.

MBP-426 is also a TfR-targeted liposome that encapsulates oxaliplatin and is designed to preferentially target the delivery of oxaliplatin to cancer cells.216 Transferrin (Tf) is widely used as a targeting ligand since the TfR is significantly upregulated on most cancer cells.217 In a phase I study, patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumours refractory to conventional therapy received MBP-426 as 2–4 h infusions every 3 weeks in cohorts of 3 to 6 patients, and this targeted liposome was demonstrated to be well tolerated (with thrombocytopenia as the main dose limiting toxicity (DLT)).216

The last decade has seen a variety of strategies involving conjugation of targeting ligands to the surface of NPs in order to provide molecular interaction points between the NPs and antigens present on target cells and tissues. What has emerged from these studies is that a variety of different targeting ligands can trigger NP internalization into cells, and that internalization can significantly enhance treatment efficacy.51, 62 Table 2 highlights from the literature the wide range of targeted polymeric NPs along with their available physicochemical properties developed for numerous therapeutic applications.

Table 2.

Examples of preclinical targeted polymeric nanoparticles

| Material | Physicochemical Characteristics (Size, ζ-potential) |

Targeting Strategy | Drug/Disease or Indication |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl | 220–240 nm, 02212;2 mV | Phosphorylcholine | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 153 |

| phosphorylcholine-co-butyl methacrylate) and poly(methacryloyloxyethylphos- phorylcholine-co-butylmeth- acrylate-co-methacryloyl hydrazide) |

||||

| Poly(lactic acid)-selectin conjugates | 170 nm, −20 mV | Small molecule; Selectin ligand | Inflammation | 154 |

| Galactosylated-chitosan polymer | 120 nm, +5 mV | Small molecule; Galactose | DNA/Various | 155 |

| Chitosan | 200 nm, + 40 mV | RGD; Charge | siRNA/Cancer | 156 |

| Chitosan-PEG | 150 nm, +16 mV | Antibody | Caspase inhibitor pep tide/Stroke |

157 |

| Poly(caprolactone) and poly(ethylene glycol) or poly(2-N,N-dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) |

25–200 nm | Passive | Various | 158 |

| (Allyloxy)12cucurbit[6]uril polymer | 70–90 nm | Triggered; Reducing environment sensitive | Cancer | 159 |

| Cyclodextrin polymer | 100–150 nm, +15mV | Transferrin | DNA/Cancer | 160 |

| Acetal modified dextran | 250–300 nm, −5 mV to + 12 mV | Pep tide | Various | 161 |

| DNA | 410 nm | Passive | Various | 162 |

| Elastin-like polypeptides | 20 nm | Triggered; pH-sensitive | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 163 |

| 60 nm | RGD; T-sensitive | Cancer | 164 | |

| Gelatin | 250–300 nm, −20 mV | Antibody | antiCD3 mAb/Cancer | 165 |

| poly(β-amino esters) | 200 nm, −5 mV | RGD | DNA/Gen therapy | 166 |

| Heparin | 60 nm, −16 mV | Small molecule; Folate | Paclitaxel/Cancer | 167 |

| Hyaluronic acid | 250–400 nm | Intrinsic | Cancer | 168 |

| Hyaluronic acid-ceramide/ pluronic 85 |

110–140 nm, −20 mV | Passive | Docetaxel/Cancer | 169 |

| Hydrophobically modified glycol chitosan |

360 nm, +22mV | Charge | Cancer | 170 |

| Oligoethylene glycol pyridine disulfide nanogels | 190 nm | Reducing environment sensitive |

Hydrophobic drugs | 171 |

| Poly(methyldiethene- aminesebacate)- co-[(cholesterylox- ocarbonylamidoethyl) methylbis(ethylene) ammonium bromide]sebacate |

80–180 nm, +70mV | Charge | Paclitaxel, DNA/Cancer | 172 |

| Poly(ethyleneoxide)-modified | 100–150 nm, +40mV | Triggered; pH-sensitive | Paclitaxel/Cancer | 173 |

| poly(beta-amino ester) | 60 nm | Triggered; pH-sensitive | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 174 |

| Modified poly(caprolactone)copolymer |

120 nm, −60 mV | Small molecule; Galactose | Various | 175 |

| Poly(carboxybetaine methacrylate) | 110 nm | Triggered; Reducing environment sensitive; RGD |

Reducing environments | 176 |

| PEG (PRINT) | 290 nm, −30 mV | Transferrin | Cancer | 177 |

| Poly(caprolactone)- | 25–60 nm, −5 mV | Large peptide; EGF | Cancer | 178 |

| poly(ethyleneglycol) | 70 nm, −3 mV | Pep tide | Brain | 179 |

| PEGylated Gelatin | 200 nm | Passive | DNA/Various | 180 |

| Poly(methacrylic acid) | 150–170 nm, −20 mV | Small molecule; Folate | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 181 |

| Poly(lactic acid) | 45 nm | Peptide; RGD | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 182 |

| 70–95 nm, −30 mV to + 45 mV | Charge | Various | 183 | |

| 80 nm, −25 mV | Triggered; pH-sensitive | Cisplatin/Cancer | 184 | |

| Poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) | 110–190 nm | Antibody | Camptothecin/Cancer | 185 |

| 260 nm, −8 mV | Peptide | Inflammation | 186 | |

| 140–180 nm, −20 mV | Peptide | Loperamide/Analgesia | 187 | |

| poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide)- lipid hybrid |

80–120 nm | Passive | Doxorubicin, Combretastatin-4/ Cancer |

188 |

| 60 nm | Peptide | Injured vasculature | 147 | |

| poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide)- poly(ethyleneglycol) |

180 nm, −3 mV | Peptide; Tetanus toxin C fragment |

Neurons and Neuroblastoma |

189 |

| 40–60 nm | Small molecule; Alendronate | Estrogen/Bone hydroxyapatite |

190 | |

| 80–200 nm | Aptamer | Docetaxel/Cancer | 191 | |

| 140 nm | Aptamer | Cisplatin prodrug/Cancer | 192 | |

| 100 nm | Passive | MAPK signaling/ Cancer |

193 | |

| 100–120 nm, −20 mV | Peptide | Brain | 194 | |

| 80 nm | Small molecule | Epigallocatechin 3-Gallate/Cancer |

195 | |

| poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide)- poly(ethyleneglycol)-Aptamer |

160–240 nm, −25 mV | Aptamer | Docetaxel/Cancer | 196 |

| Poly(L-lysine) | 80 nm, + 1 mV | Triggered; pH-sensitive | Acidic tumours | 197 |

| Poly(lactic acid)-poly(ethyelene glycol) and poly(caprolactone)- poly(ethyeleneglycol) |

20–200 nm | Ultrasound triggered | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 198 |

| Pluronic | 40 nm, + 18 mV | Peptide | Cartilage | 199 |

| poly(N-isopropylacrylamide- b-methyl methacrylate) |

190 nm | Triggered; T-sensitive | Prednisone/Inflammation | 200 |

| poly((1-ethoxycarbonyl)-vinyl- phosphonic diacid and poly(n-butyl acrylate) |

80–120 nm | Protein; Annexin-A5 | Inflammation | 201 |

| Poly(ethylene glycol)- poly(aspartate hydrazone adriamycin) | 65 nm | Triggered; pH-sensitive | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 89 |

| Poly(γ-glutamic acid)-PL | 115–126 nm, −20 mV | Small molecule; Galactosamine | Paclitaxel/Cancer | 202 |

| Poly(L-glutamic acid) | 50 nm | Small molecule; Biotin | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 203 |

| poly(2-methyl-2-carboxy- trimethylene carbonate- co-d,l-lactide) |

130 nm | RGD | Corneal epithelial cells | 204 |

| Poly(β-malic acid) | 7–25 nm, −5 mV | Multiple; Antibody; Triggered | Antisense ON/Brain Tumour |

205 |

| 15–25 nm, −5 mV | Multiple; Antibody | Antisense oligonucleotides Hercep tin/Cancer |

206 | |

| Poly(γ-benzyl-L-glutamate)- Poly(vinylybenzyllactonamide) |

40–300 nm | Small molecule; Galactose | Various | 207 |

| Poly(acrylamide) | 20–30 nm | Peptide | Cisplatin/Cancer | 208 |

| Poly(hydroxyalkanoates) | 100–200 nm | Polypeptide | Cancer | 209 |

| Pullulan acetate/sulfadimethoxine conjugate |

70 nm | Triggered; pH-sensitive | Doxorubicin/Cancer | 210 |

| Ribonucleoprotein | 40–70 nm | Passive | Various | 211 |

| Styrene-maleic acid copolymers | 175 nm | Zinc protoporphyrin | Cancer | 212 |

3.3 Clinical stage targeted polymeric NPs

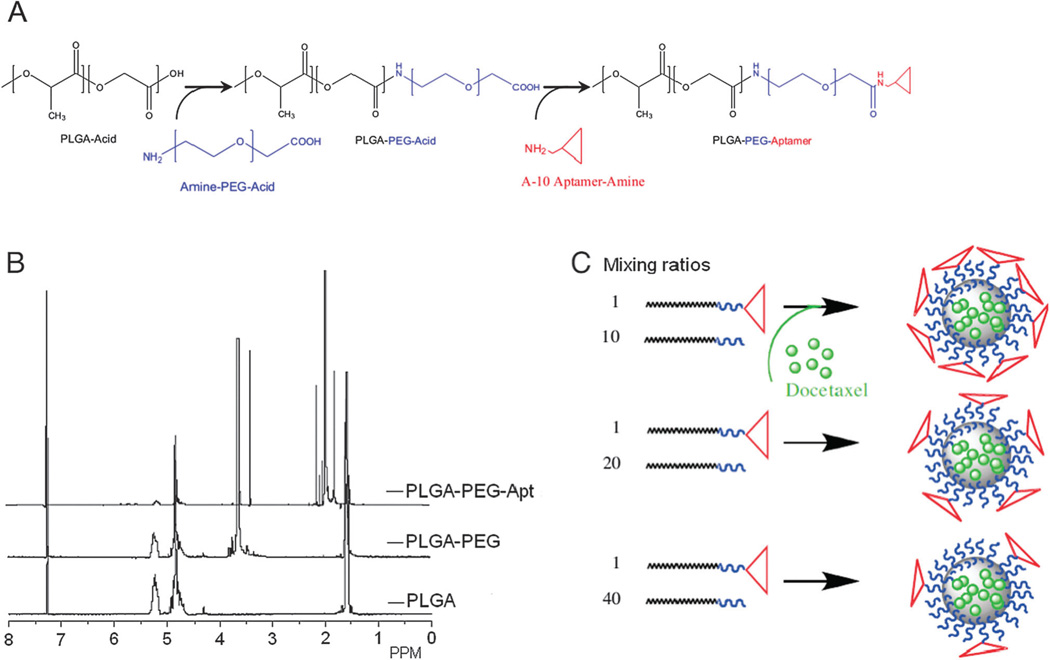

Conventional methods of preparing targeted NPs involve a series of chemical processes whereby the NP core is initially formed, followed by the bioconjugation of targeting ligands to the surface of the NP. This post-coupling of targeting ligands does not allow tuning of ligand density for optimal efficacy, requires excess amounts of reagent in order to achieve high coupling efficiencies, and is associated with purification techniques to remove unbound ligands. Due to this kind of complexity in the synthesis of NPs, difficulties may arise in the reproducibility of NP surface properties, resulting in batch-to-batch variability, which is not amenable to clinical translation and subsequent commercialization. Indeed, by reducing the number of components to the minimum, and employing a modular self-assembly approach using pre-functionalized polymeric materials,218 it is possible to create libraries of targeted NPs that vary narrowly from each other in their biophysicochemical properties. Using this strategy, BIND Biosciences recently developed and screened a library of targeted self-assembled polymeric NPs resulting in the development of BIND-014, the first targeted and controlled release polymeric NP for cancer chemotherapy to reach clinical development.219 BIND-014 is a prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted Dtxl-encapsulated polymeric NP, which entered phase I clinical trials in January 2011.219 PSMA is a transmembrane protein overexpressed on the surface of prostate cancer cells and tumour-associated neovasculature of virtually all solid tumours.220, 221 Dtxl is a semi-synthetic taxane approved for treatment of a number of major solid tumour cancers, including breast, prostate, lung, gastric, and head and neck.222 BIND-014 has been shown to deliver up to 10 times more Dtxl to tumours relative to an equivalent dose of Dtxl in multiple animal models.219 Initial clinical data in patients with advanced solid tumours indicate that BIND-014 displays a pharmacological profile differentiated from Dtxl, including pharmacokinetic properties consistent with long circulation half-life of BIND-014 and retention of Dtxl in the vascular compartments, and multiple cases of tumour shrinkage at doses up to 5 times below the Dtxl dose typically administered clinically.219

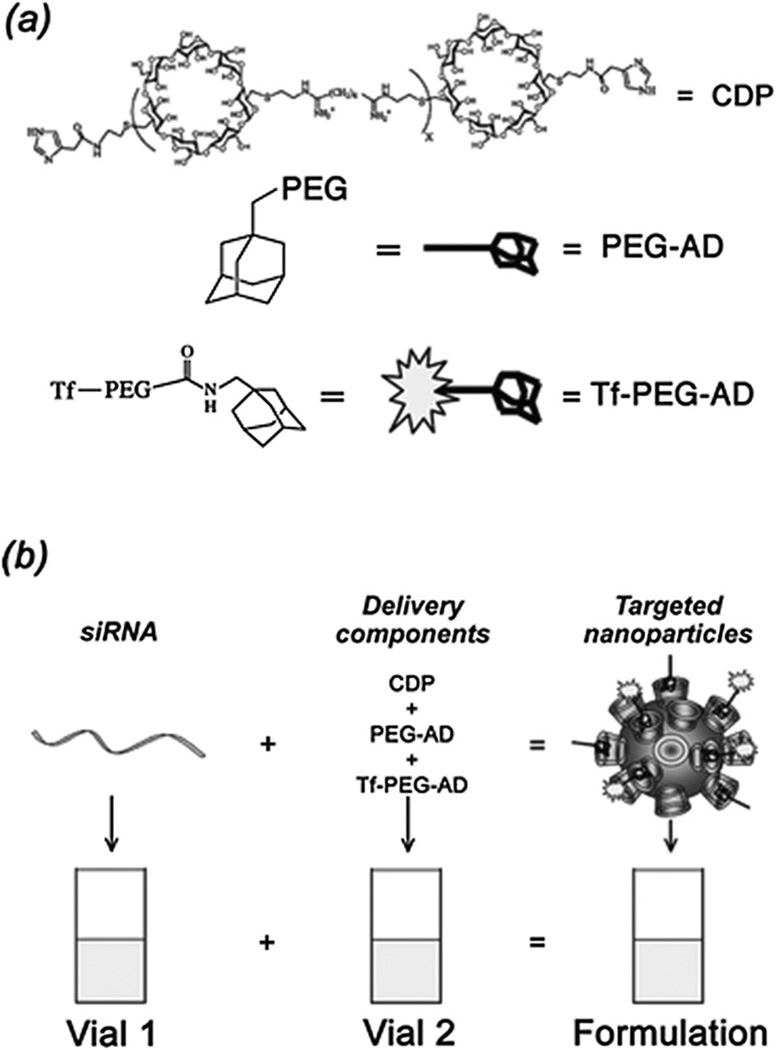

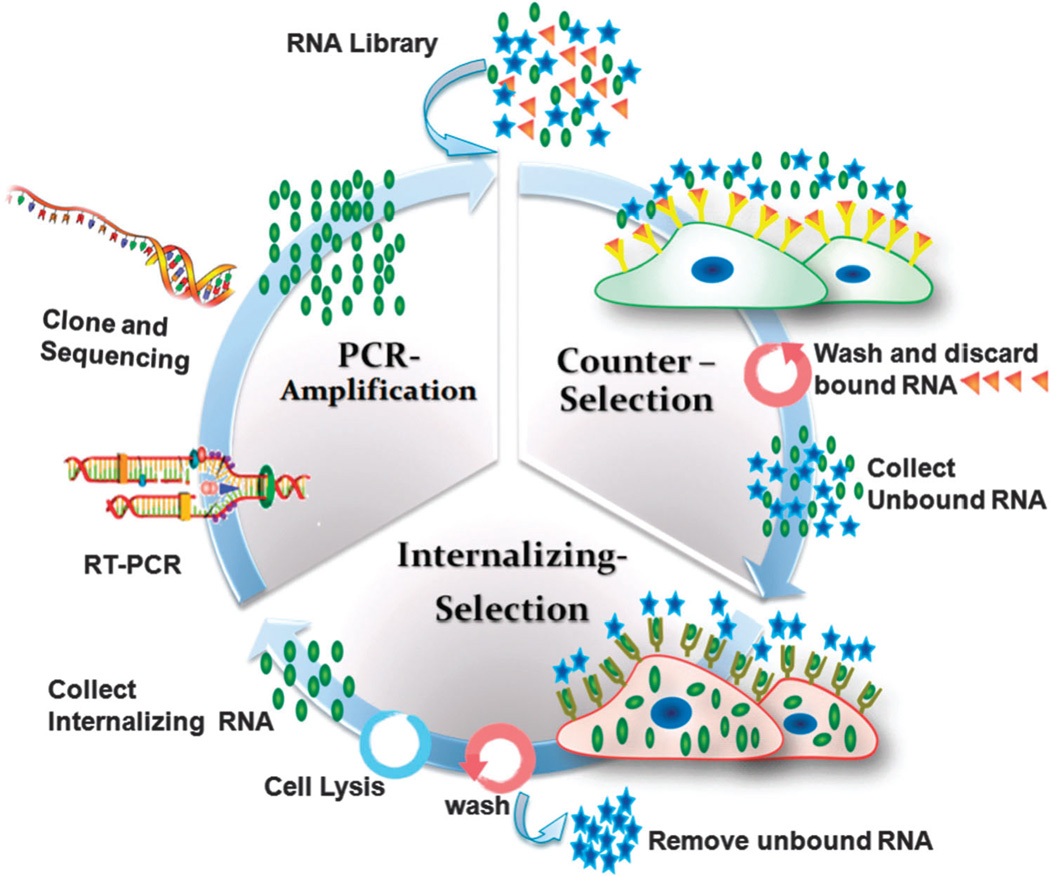

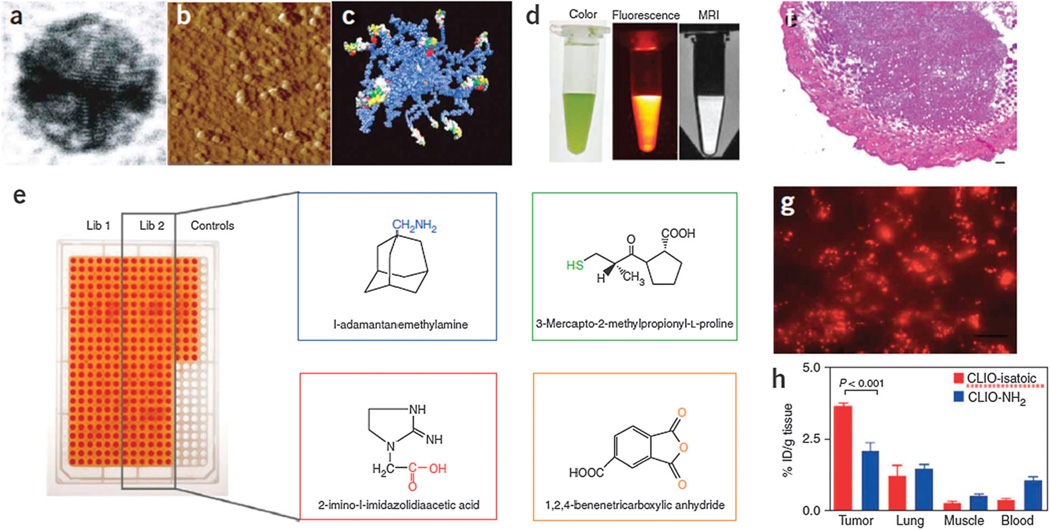

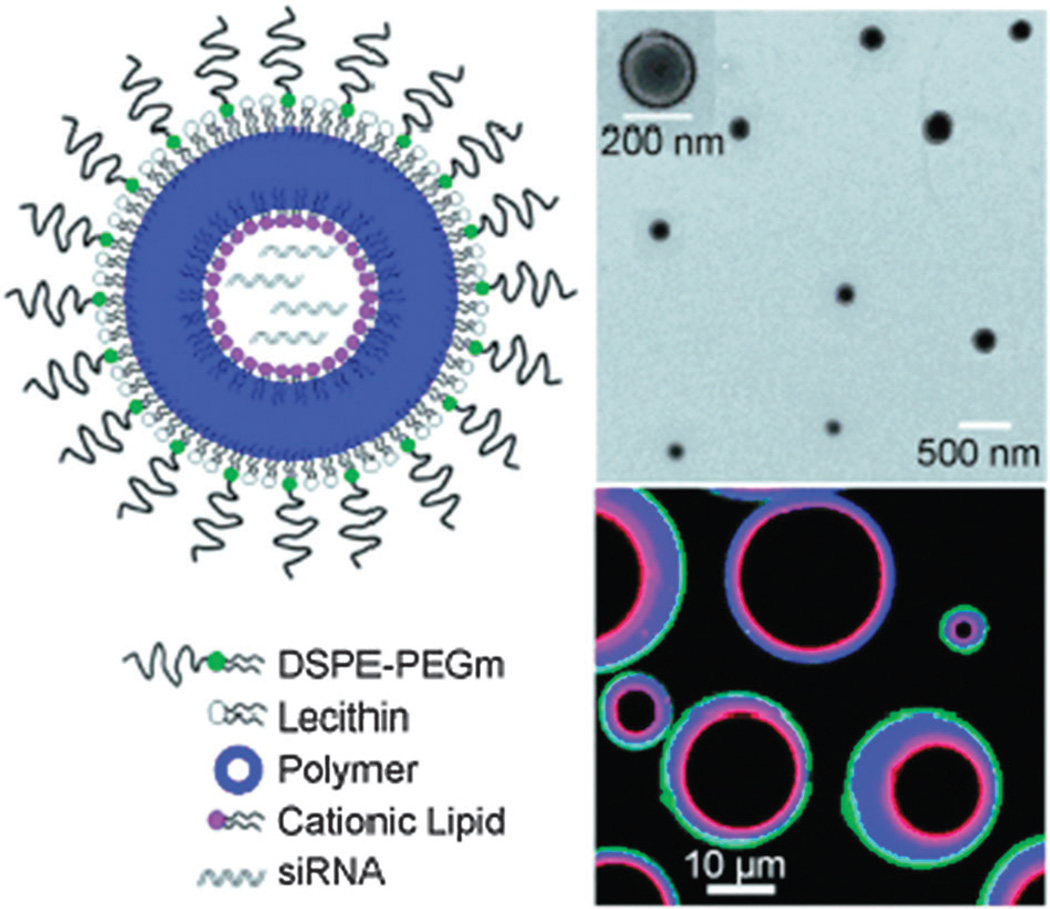

CALAA-01 is the first targeted NP to reach clinical development for siRNA delivery in 2008.18 The CALAA-01 NP consists of siRNA to reduce the expression of the M2 subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (R2), cyclodextrin containing polymer (CDP) for siRNA condensation, adamantine-PEG (AD-PEG) for steric stabilization, and adamantine-PEG conjugated to human Tf (AD-PEG-Tf) to target the TfR overexpressed on the surface of most cancer cells.223 CALAA-01 employs a unique two-vial formulation strategy, which allows for the rapid self-assembly of the NP (50–70 nm) delivery system components (CDP, AD-PEG, AD-PEG-Tf) with siRNA, at the point of care (Fig. 3).18 This formulation is also capable of high siRNA payload delivery and endosomal pH (<6.0) triggered release of siRNA once NPs are endocytosed.224

Fig. 3.

Components of CALAA-01 (Calando Pharmaceuticals-01) – a targeted NP for siRNA delivery: (a) CDP: water-soluble, linear cyclodextrin-containing polymer, AD: adamantane (AD)-PEG conjugate (PEG MW of 5000) (AD-PEG), and Tf-PEG-AD: an adamantane conjugate of PEG (PEGMWof 5000) conjugated with human transferrin (Tf) ligand. (b) CALAA-01 is formulated via a single self-assembly process of four individual components. Figure taken from Davis, M et al.18

SEL-068 is a first-in-class synthetic and integrative targeted polymeric NP vaccine to reach phase I clinical development in November 2011. SEL-068 contains nicotine as antigen, T-helper cell peptides, TLR agonists as adjuvant, and is currently under development for smoking cessation and relapse prevention.27 Post smoking, nicotine usually enters the lung and the systemic circulation and reaches the brain by crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and binds to nicotine receptors resulting in release of stimulants such as dopamine leading to reinforcement of addiction.225 The administration of SEL-068, which is based on modular self-assembly NP technology,196 results in high anti-nicotine antibody concentrations and a high anti-nicotine antibody affinity; leading to the sequestration of nicotine molecules in circulation and largely blocking central nervous system exposure, thereby diminishing the addictive effects of nicotine.

The clinical translation of the above technologies has marked a new era in the development of multi-functional therapeutic NPs capable of targeting, controlled release, and co-delivery of multiple active agents.

4. Preparation of targeted polymeric NPs

4.1 Methods for preparing polymeric NPs

A number of top-downmethods are available for the preparation of polymeric NPs using biodegradable polymers. Most of these involve self-assembly of block copolymers that are composed of two distinct polymer chains with different solubilities. These methods include nanoprecipitation (also called solvent displacement method),226 various types of emulsification/solvent evaporation,227 and the salting out method.228 In addition to these conventional methods, new approaches used to create polymeric NPs, including supercritical technology, electro-spraying, premix membrane emulsification and aerosol flow reactor methods are also under investigation which are further discussed in a recent review.229 The choice of NP formulation method is usually dependent on the drug physicochemical properties along with the requirements for encapsulation and particle size. Nanoprecipitation, oil-in-water (O/W) emulsification-solvent evaporation (single emulsion), and water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) emulsification-solvent evaporation (double emulsion), are three of the most commonly utilized methods to prepare a variety of polymeric NPs and will be described in the next paragraphs.

Nanoprecipitation is a method that involves the use of an organic solvent that is miscible with an aqueous phase.230 In this technique, the polymer and drug are dissolved in the organic solvent and this solution is then added dropwise to an aqueous (non-solvent) solution under stirring. Once in contact with water, the hydrophobic polymers and drug precipitate and self-assemble into core-shell like spherical structures in order to reduce the system’s free energy.45 After self-assembly, the organic solvent is evaporated either by reduced-pressure evaporation, or simply by continuous mixing at atmospheric pressure if the solvent is relatively volatile. The instantaneous formation of particles is governed by the principles of the Marangoni effect and has been attributed to interfacial interactions between liquid phases.231

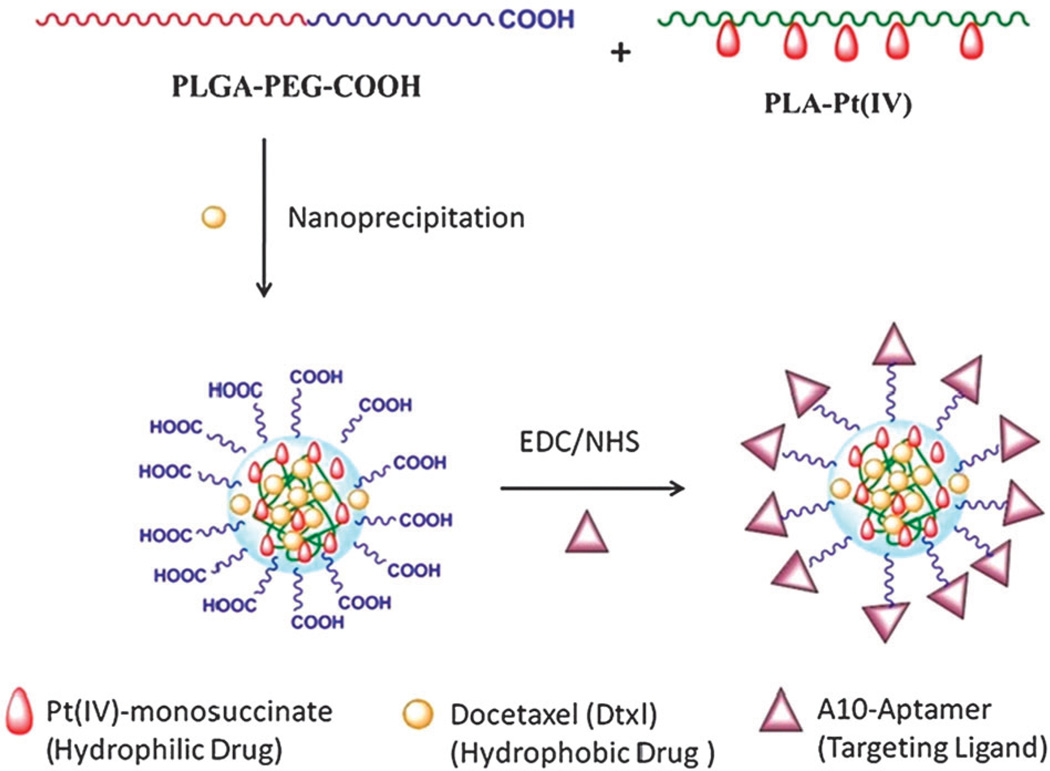

The use of diblock hydrophobic-PEGylated polymers in nanoprecipitation leads to NPs that consist of a hydrophobic core, with entrapped hydrophobic drugs, surrounded by a hydrophilic shell for steric stabilization.232 For example, Dtxl-loaded NPs were prepared using nanoprecipitation, whereby the hydrophobic drug Dtxl was mixed and co-precipitated with the diblock polymer poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-polyethylene glycol-carboxylic acid (PLGA-PEG-COOH).233 The resulting NPs had a hydrophobic core composed of PLGA, wherein Dtxl was encapsulated, and a hydrophilic shell composed of PEG. Nanoprecipitation is a simple method, amenable to scale-up at an industrial scale requiring only mild stirring under minimal shear stress. In general, smaller NPs are obtained through this method when compared to other methods at equivalent conditions. In contrast, some drawbacks include the poor entrapment of hydrophilic drugs (hydrophilic drugs can remain in the aqueous phase),229 lower entrapment efficiencies compared to other methods and difficulty in complete removal of the organic solvent after self-assembly.232 Although recent advances whereby the aqueous water phase (non-solvent) is replaced with other organic solvents (methanol, ethanol) has facilitated the use of this technique for the use of hydrophilic drugs also.229

Emulsification techniques (water-in oil: W/O, oil-in water: O/W and double emulsion: W/O/W) require the formation of emulsion, followed by the homogenization of this mixture, and although originally used to formulate microparticles, can now also be utilized to prepare nano-emulsions.234 The type of emulsification method utilized ultimately depends upon the properties of the polymer, drug and also the degree of miscibility of the organic (oil) solvent with the water phase.

The single emulsion technique (O/W) requires the drug to be soluble in a water-immiscible organic solvent. In this method, the polymer and the drug are dissolved in a volatile water-immiscible solvent such as dichloromethane or ethyl acetate, and the organic phase is emulsified under intense shear stress into an aqueous phase containing appropriate amounts of a surfactant, such as sodium cholate or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). The organic solvent is allowed to evaporate, allowing the self-assembly of NPs.235 The O/W emulsification technique is suitable for entrapping hydrophobic drugs and generally results in higher drug loading and encapsulation efficiency compared to nanoprecipitation, as well as achieving complete solvent removal. However it requires an additional input of energy such as sonication or homogenization and the resulting NPs are often larger than those obtained through nanoprecipitation.235

Double emulsion (W/O/W) is generally used for encapsulation of hydrophilic drugs and proteins. In this method the drug is dissolved in a small volume of an aqueous phase together with a surfactant and this is emulsified in an organic phase containing the polymer. The W/O emulsion formed is then dispersed in a larger volume of an aqueous phase with or without surfactant to form the double W/O/W emulsion. Finally, the solution undergoes evaporation of the remaining organic solvent yielding NPs.235 This method normally yields NPs with larger size than nanoprecipitation or O/W methods, with moderate drug loading and encapsulation efficiency.232

In the aforementioned NP preparation methods, several factors affect the physicochemical properties of the NPs, such as the solvent of choice, the solubility of the drugs (e.g. log Po/w), the mixing time of the aqueous and organic solvents, the type of surfactant used, the concentration of polymer in the organic solution, the ratio of organic to aqueous solution in addition to others.45, 229, 232 For instance, Cheng et al.191 systematically studied the effect of some of these factors on the physicochemical properties of PLGA-PEG NPs. Their data suggested that an increase in the water miscibility of the solvent led to a decrease in mean NP size, and a linear relationship between polymer concentration and size was further shown. The solvent/water ratio, however, did not have a clear relationship with NP size. In addition, the effect of drug loading on resulting NP size distributions was also investigated.191 While plenty of examples exist that demonstrate the reproducible production of polymeric NPs using the range of aforementioned therapeutic NP preparation techniques—the ultimate challenge arises with the translation of these methods to industrial scale production levels. Despite the revolutionary developments in nanotechnology and the clinical translation of a range of NPs containing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), greater strides are needed in NP synthesis, processing, scale-up and manufacturing.229

4.2 Microfluidic methods

Microfluidics, the science and technology of manipulating nanoliter volumes in microscale fluidic channels, has shown that several labour-intensive and time-consuming steps such as sample preparation, mixing, reactions, purification, separations, and detection could be performed on a single monolithic microfabricated device.238 In the last few years, applications of microfluidics have expanded from conventional chemical and biological analysis to other fields such as chemical reactions, biochemical assays, and cell handling.239 Two particularly important contributions have been the development of soft lithography in PDMS as a method for fabricating prototype devices, and the simple fabrication of pneumatically activated valves, rapid mixers and pumps on the basis of soft-lithographic procedures. This has resulted in the fabrication of prototype devices to test new ideas in approximately 2 days (from design to working device), whereas the same applications for silicon technology may take a month ormore for non-specialists to carry out.With respect to nanoparticles, the ability of microfluidic systems to mix reagents rapidly, provide homogenous reaction environments, continuously vary reaction conditions, enable rapid temperature control, and allow addition of reagents at precise time intervals—are some of the key features that have made microfluidic systems useful for the synthesis of NPs.240 Furthermore, synthesis carried out in microchannels allows for in-line characterization,241 feedback control,242 and high-throughput continuous synthesis,243 which potentially enables screening and optimization of libraries of nanoparticles with different properties.

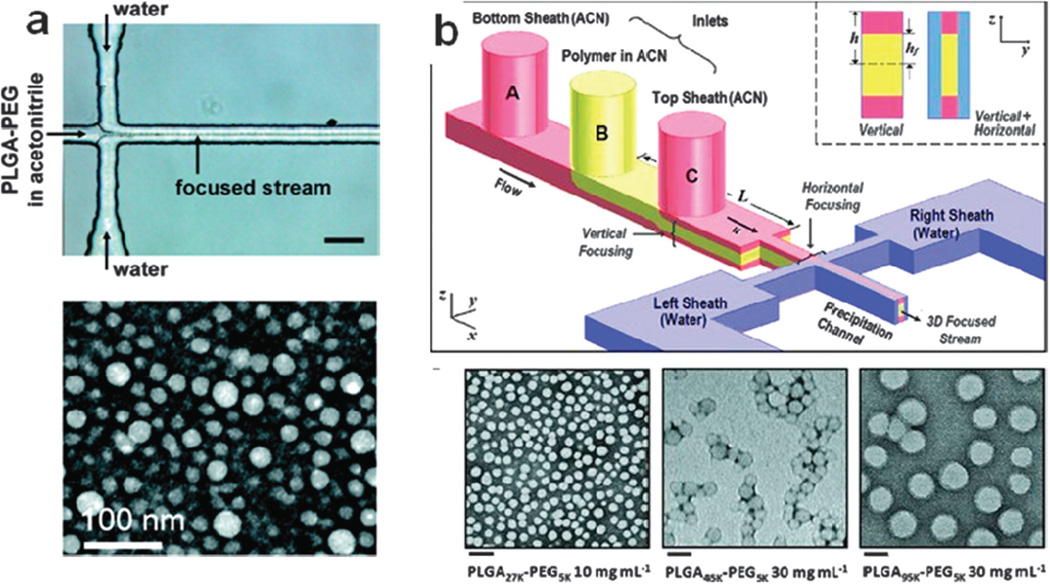

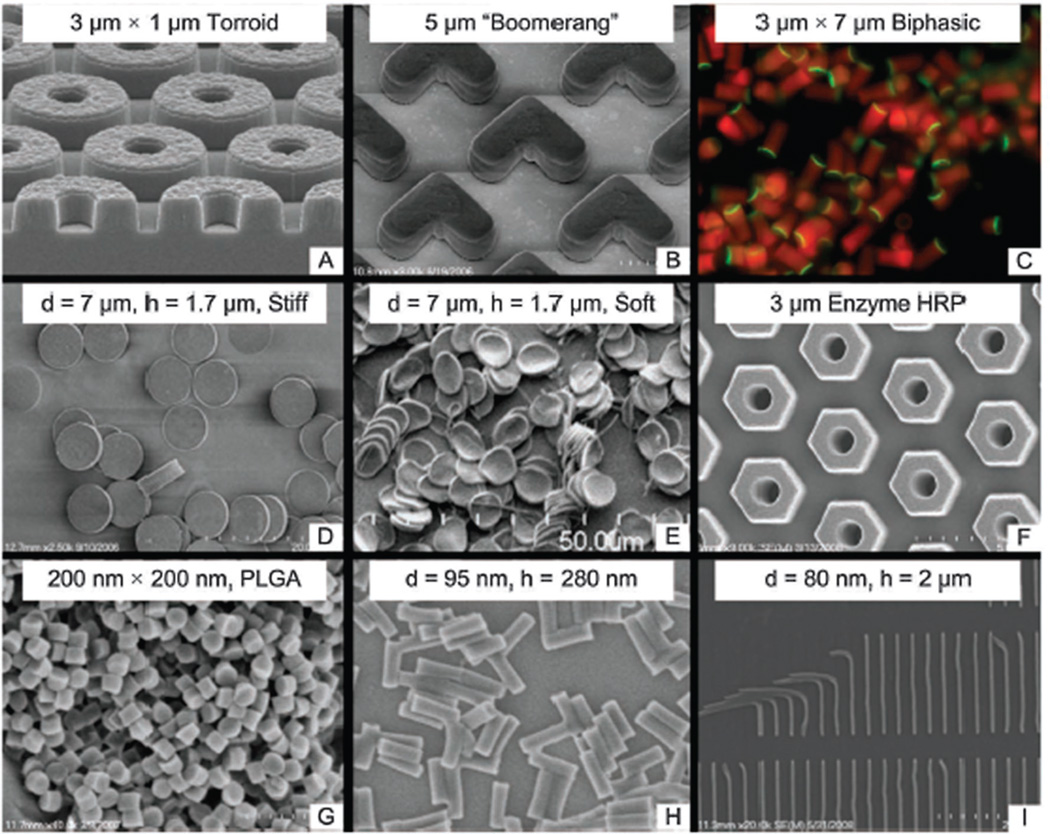

Recently, technologies developed for the synthesis of polymeric NPs have demonstrated the tremendous potential for microfluidics to dramatically improve on current bulk synthesis methods. Polymeric NPs prepared by bulk synthesis tend to have variable physicochemical properties (size, surface composition, and drug loading) due to the inability to control the mixing of precursors.236 Further post-processing by extrusion, freeze–thaw, sonication, and/or high-pressure homogenization is often required. Using rapid mixing techniques in micro-channels such as hydrodynamic flow focusing, polymeric NPs exhibiting narrow size distributions compared to bulk synthesis have been prepared in a reproducible manner (Fig. 4).236, 237 In these systems size can be tuned by either varying the mixing time of precursors, which is achieved by varying the flow ratio of the precursor streams, by varying the molecular weight of the polymer, or by simply varying the concentration of the polymer in the organic solution. Remarkably, for polymeric NPs prepared through microfluidics, higher drug encapsulation without increase in NP size has been observed,236 which is highly desired for therapeutic NPs. Another method to prepare NPs takes advantage of the rapid mixing microenvironment that occurs in micro-droplets formed inside microfluidic channels.244 For instance, cross-linked alginate NPs were synthesized in a micro-channel using aqueous alginate droplets as templates, followed by the shrinkage of the drops. This method exhibited remarkable control over the NP properties, specifically size and size distribution. These are just a few examples showing the advantages of microfluidics for nanoparticle synthesis, and recent reviews discuss these concepts further.240, 245 Given the volume of research currently involving the microfluidic synthesis of NPs, it is expected that as more therapeutic NPs reach a clinical stage, the need for improved synthesis methods would also increase, at which point microfluidic technologies could likely become an important tool in their development of NPs.

Fig. 4.

(a) Microfluidic synthesis of polymeric nanoparticles prepared under rapid mixing conditions in 2D flow focusing. (b) 3D flow focusing. Figure adapted from Karnik et al. and Rhee et al.236, 237

4.3 Drug loading methods

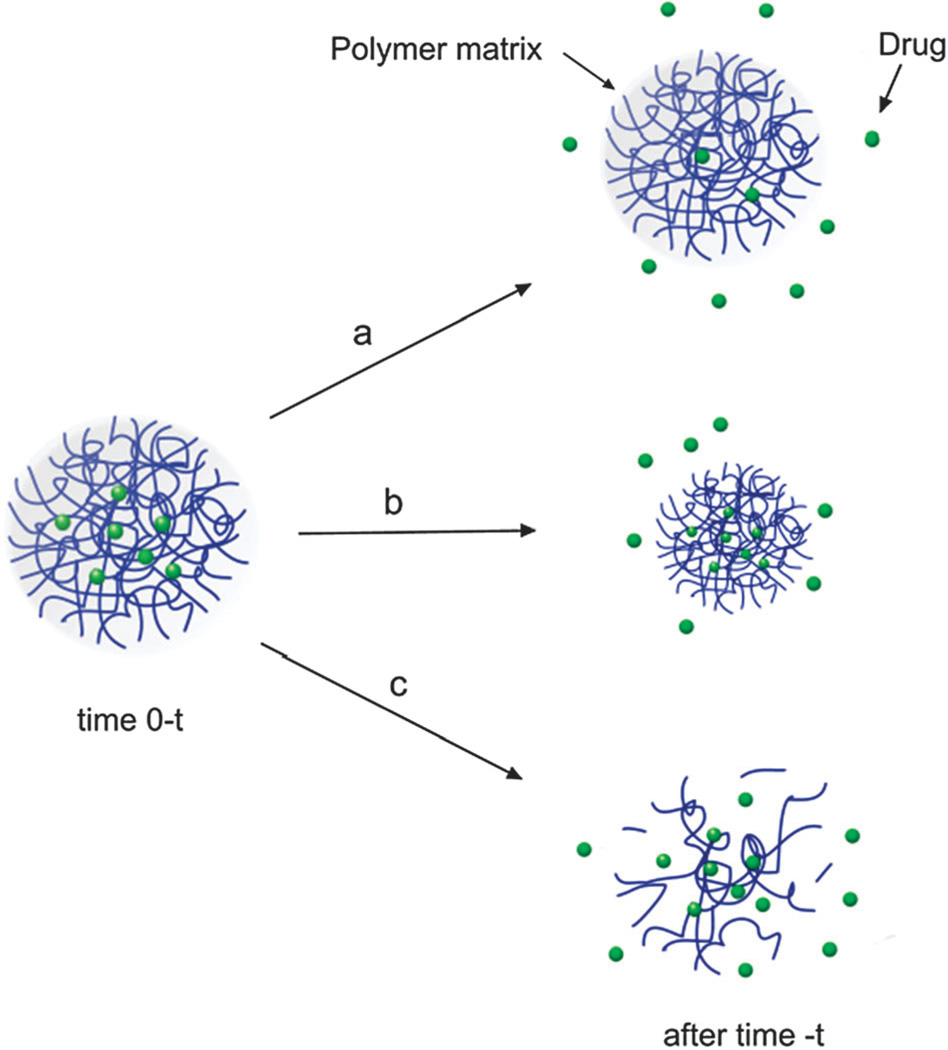

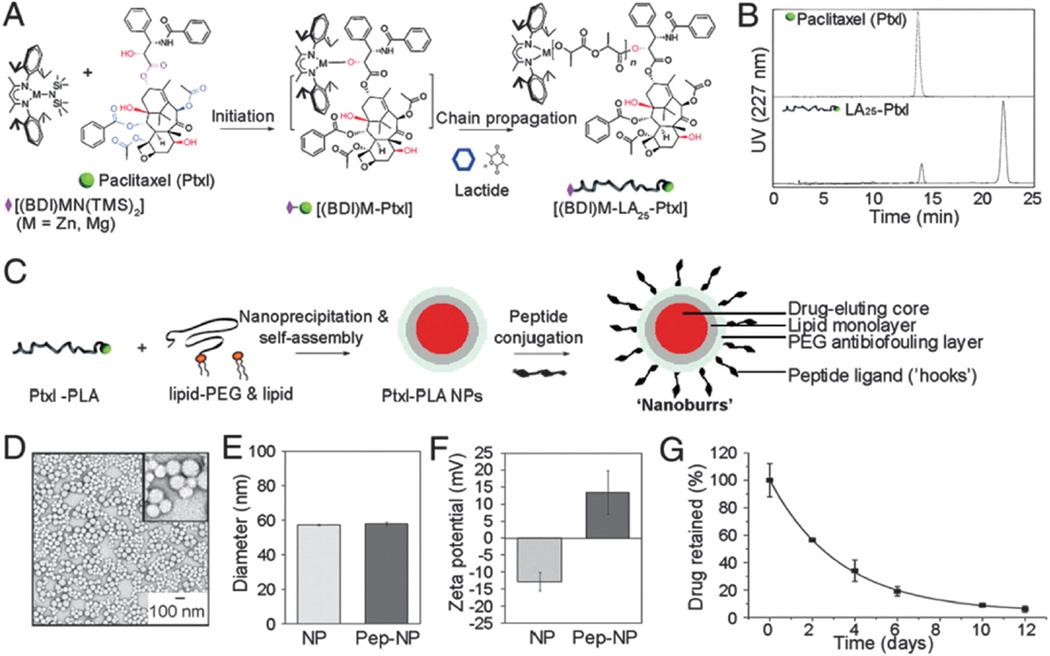

In general, drug loading into polymeric NPs can be achieved according to three techniques: (1) the drug is covalently attached to the polymer backbone, (2) the drug is adsorbed to the polymer surface, or, (3) the drug is entrapped in the polymer matrix during preparation of the NP.246 In turn, drug release rates from NPs depend upon a number of parameters including: (a) diffusion through the NP matrix, (b) erosion of the NP surface and, (c) polymer matrix degradation (see Fig. 5).51 In the following paragraphs we will discuss drug encapsulation by entrapping the drug during preparation and conjugation of the drug to the polymer backbone. Entrapping a drug during NP preparation is the most common technique used for incorporating drugs into NPs. For hydrophobic drugs the fact that they simply need to be mixed with the polymer in an organic solvent, makes it very attractive for formulation purposes. In fact, most NP formulations that are at the clinical stage rely on this method of encapsulation. However, this method suffers from some disadvantages mainly that of relatively low drug entrapment accompanied with low encapsulation efficiency at high loadings.247 In addition, maximum encapsulation efficiencies tend to vary with drug type, and are also affected by the type of polymer, solvents, temperature, and mixing time of NP precursors among other factors.248 Moreover, the encapsulation of two or more drugs with this method may be difficult to achieve, especially for drugs with different chemical properties. Conjugating drugs to the polymer backbone is an attractive alternative that minimizes some of the disadvantages encountered for drug entrapment.249–252 This method involves chemically modifying the polymer (or the drug) to allow for chemical conjugation of the drug to the polymer. Originally, this method was accomplished by conjugating drugs to a functionalized end of a polymer chain. For instance, Sengupta et al. conjugated Dox, to PLGA, and were able to reproducibly prepare Dox-loaded NPs.188 Similarly, Tong et al. developed a method to prepare Ptxl-conjugated PLA by carrying out a ring opening polymerization of LA units onto a Ptxl-metal complex.253 This drug-conjugated polymer resulted in the reproducible synthesis of NPs incorporating high loadings of Ptxl with encapsulation efficiencies close to 100%.253 While the last two examples involved conjugation of drug molecules at the distal end of a polymer chain, recently Kolishetti et al. demonstrated both the encapsulation of Dtxl and the conjugation of a cisplatin pro-drug to formulate polymeric NPs for combination therapy.254 This resulted in an increase in encapsulation together with a potential of tuning drug release kinetics by varying the number of drugs attached to the polymer.

Fig. 5.

Drug release mechanisms from polymeric NPs: (a) diffusion from polymer matrix with time varying diffusivity, (b) surface erosion/degradation of polymer matrix, and (c) biodegradation of polymer matrix due to hydrolytic degradation leading to drug release.

In order to achieve optimal polymer-drug conjugate NP systems, the following considerations should be noted: (i) the chemistry implemented in modifying the drug should not affect the chemical groups or moieties that endow the drug with therapeutic effects; (ii) the drug needs to be cleavable from the polymer backbone under biological conditions, and upon cleavage the drug should retain its functional and therapeutic properties; (iii) chemistries used for conjugation must be carefully chosen since some residues of, for instance, certain catalysts, might contaminate the resulting NPs leading to unexpected toxicity. Nevertheless, conjugation of drugs to polymer backbones is an attractive strategy to incorporate multiple drugs with varying physicochemical properties in the same NP, enabling integrated and controlled combination chemotherapy.

4.4 Incorporation of targeting ligands on NPs

The widespread interest in the surface attachment of targeting ligands to various drug delivery NPs ranging from liposomes, micelles, polymers and dendrimers has spurred chemists to actively research coupling methods that are safe, tuneable, biocompatible, and reproducible. However, unlike the limited range of chemistries available for coupling to protein surfaces, a larger number of chemical modifications are now possible in order to attach targeting ligands to NPs. This can be done through either covalent attachment of targeting ligands to the surface of the NP or through electrostatic, dative or coordinate bonds. It is important to identify the conjugation technique that will ultimately provide the most efficient coupling chemistry that does not lead to undesirable products or side reactions, and can be produced on large-scales in a reproducible manner. In the subsequent sections we will discuss common chemical strategies utilized in the development of targeted NPs, mainly conjugation of a targeting ligand after NP formation and pre-conjugation of targeting ligands to polymeric precursors followed by self-assembly of NPs.

4.4.1 Chemical strategies for incorporating targeting ligands on NPs

The most traditional approach for the development of targeted NPs involves the conjugation of targeting ligands to the surface of NPs using facile coupling chemistries such as carbodiimide-mediated amide and maleimide-thiol couplings. Amide bond formation is a popular cross-linking reaction and carboxylic acids are frequently activated using a variety of carbodiimides such as 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC). In this case, either the surface of the NP can bear carboxylic acids or the targeting ligand may have this functional group available for coupling. Although the formation of an amide bond using carbodiimide activation of carboxylic acids is a straightforward reaction, however, several side reactions can lead to undesired side reactions that produce N-acylureas, in addition to rapid hydrolysis of the reactive O-acylisourea intermediate. In order to avoid this hydrolysis an excess of the carbodiimide can be used, however considering that the surface carboxylic acid moieties are the solubility determining anchors of the NPs, then over-activation of these acids and formation of poorly soluble O-acylisourea intermediates can lead to a lack of solubility and colloidal instability and aggregation. These events can be minimized through the use of N-hydroxy-succinimide (NHS) carboxylic acid activated intermediates and can improve reaction efficiencies as the NHS intermediate is more resistant to hydrolysis. The formation of amide bonds between NP carboxylic acids and amino groups of targeting ligands is a popular bioconjugation method; however ligand conjugation numbers and surface densities cannot be effectively controlled. Maleimide coupling with thiols is highly specific, less prone to hydrolysis, and can occur at neutral pH; this method has been very useful for coupling to cysteine residues of proteins or other thiol containing ligands, and avoids the formation of undesirable side reactions.255, 256

The search for highly specific chemical reactions that create unique linkages and avoid susceptibility to competing reactions has led to the development of “bioorthogonal” reactions. This class of reactions aremainly concerned with [3+2] cycloadditions between azides and alkynes, and is more commonly known as click chemistry.257 In order to avoid the use of toxic copper catalysts in these reactions, various copper-free click chemistry reactions have also been developed and many studies are now underway that demonstrate the versatility of this type of bioconjugation technique.258–261 A further bioorthogonal [4+2] cycloaddition reaction was recently described by Devaraj et al. and was applied to the labelling of cancer cells, peptides and small molecules.262 This transition occurs between a 1,2,4,5-tetrazene (Tz) and trans-cyclooctene (TCO) and proceeds rapidly at room temperature and under physiological conditions without the need for a catalyst.263 This conjugation reaction was successfully used in a novel labelling methodology termed “bioorthogonal nanoparticle detection” or “BOND” to conjugate antibodies to nanoparticles.264 Antibody proteins were initially conjugated with TCO moieties and then reacted with Tz-functionalized NPs leading toNPs with multiple antibodies bound to their surface. This strategy can be used for efficient targeting and signal amplification and has been mainly applied to diagnostic applications for the highly sensitive detection of cancer cells.263 From a synthetic perspective, the development of targeted NPs poses many challenges which include the following: (1) the exact ligand conjugation stoichiometry is not easy to control and therefore only average ratios of coupled ligands to NP surfaces can be estimated, (2) ligand conjugated NPs will not always have a low polydispersity and some NPs may possess higher numbers of ligands than others, (3) targeting ligands may not always attach to the surface of NPs through predictable covalent bonds and may interact with the surface of NPs through aggregation phenomenon, (4) the bioactivity of targeting ligands may be compromised following attachment to the NP surface, which could also affect the NP therapeutic performance, (5) the coupling chemistries involved must be highly specific, occur rapidly and ideally be amenable to biological environments, (6) the conjugation linkages employed between ligands and NPs must be durable in the highly complex in vivo environment and not become prone to competing reactions that may be brought about by changes in pH or hydrolysis unless these are intended mechanisms used for ligand and/or NP protective layer shedding and finally, (7) the bioconjugation techniques employed in ligand conjugation to NPs should be scalable, reproducible and economical.265

4.4.2 Targeted NPs through polymer self-assembly

As we have seen in the previous section, the conventional approach to the development of targeted NPs involves the conjugation of bioactive molecules to the surface of NPs via coupling chemistries. Even though excess amounts of reactants are often used to drive these reactions to completion, and given the heterogeneous nature of NP samples, it is difficult to control the stoichiometry of functional biomolecules on the surface of NPs, thus leading to poor reproducibility in manufacturing.

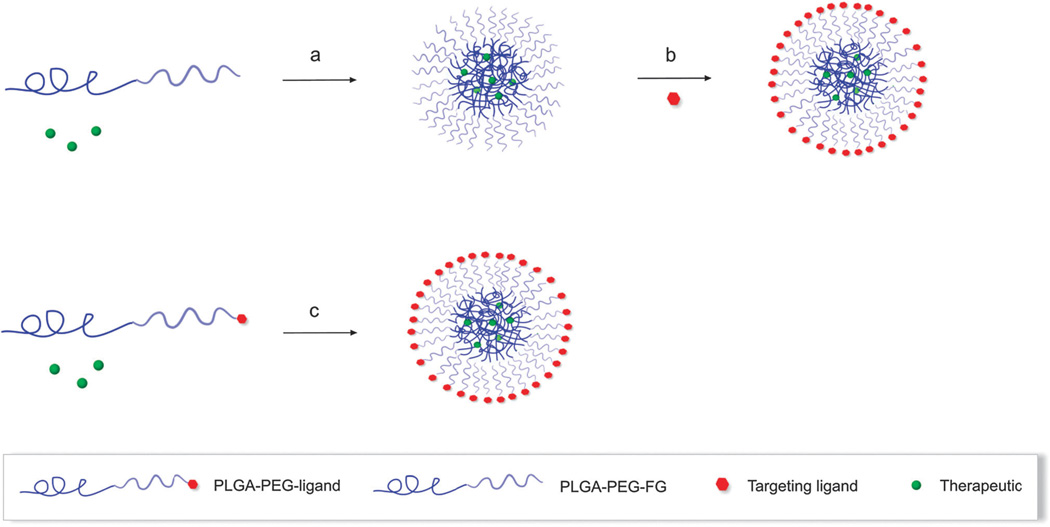

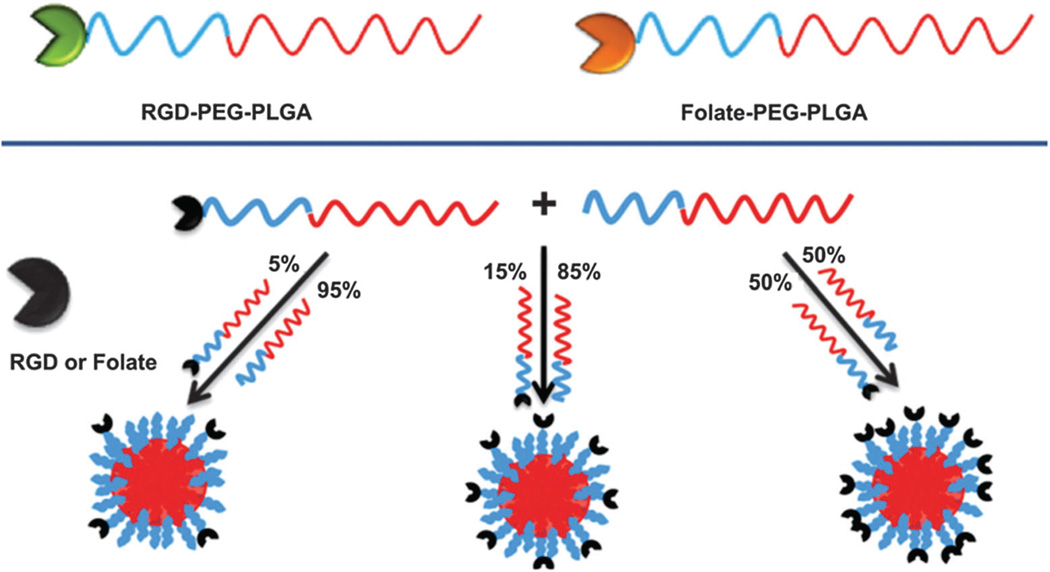

Recently, alternative approaches such as the self-assembly of targeted NPs using pre-functionalized components such as PEG polymers, and polymer-drug and polymer-targeting ligands have been developed to precisely engineer NP surfaces tending to uniformity (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.