Summary

Adult skeletal muscle possesses a remarkable regenerative capacity, due to the presence of satellite cells, adult muscle stem cells. We used fate-mapping techniques in avian and mouse models to show that trunk (Pax3+) and cranial (MesP1+) skeletal muscle and satellite cells derive from separate genetic lineages. Similar lineage heterogeneity is seen within the head musculature and satellite cells, due to their shared, heterogenic embryonic origins. Lineage tracing experiments with Isl1Cre mice demonstrated the robust contribution of Isl1+ cells to distinct jaw muscle-derived satellite cells. Transplantation of myofiber-associated Isl1-derived satellite cells into damaged limb muscle contributed to muscle regeneration. In vitro experiments demonstrated the cardiogenic nature of cranial- but not trunk-derived satellite cells. Finally, overexpression of Isl1 in the branchiomeric muscles of chick embryos inhibited skeletal muscle differentiation in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that this gene plays a role in the specification of cardiovascular and skeletal muscle stem cell progenitors.

Keywords: Satellite cells, splanchnic mesoderm, cardiogenesis, myogenesis

Introduction

There are ~ 60 distinct skeletal muscles in the vertebrate head that control food intake, facial expression, and eye movement. In recent years, interest in this group of muscles has significantly increased, with the accumulation of new lineage tracing, molecular profiling, and gene targeting studies [reviewed in (Bothe et al., 2007; Grifone and Kelly, 2007; Noden and Francis-West, 2006; Tzahor, 2009)]. Head muscles are generally classified according to their anatomical location and function within the head: for example, the six extraocular muscles move and rotate the eye in a highly coordinated manner; branchiomeric muscles control jaw movement and facial expression, as well as pharyngeal and laryngeal function. Muscles in the neck and tongue are derived from myoblasts originating in the most anterior set of somites [reviewed in (Noden and Francis-West, 2006)].

Several lines of evidence indicate that different, sometimes opposing, intrinsic and extrinsic regulatory pathways control skeletal muscle formation in the trunk and head regions. For instance, genetic loss of myogenic transcription factors in mice differentially affects head and trunk muscles (Dong et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2002; Rudnicki et al., 1993; Tajbakhsh et al., 1997). Bmp and Wnt/β-catenin pathways are potent regulators of trunk and cranial mesoderm progenitors [reviewed in (Buckingham, 2006)]. Manipulations of these signaling molecules in chick embryos resulted in distinct cellular responses in trunk and cranial paraxial mesoderm (Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006; Tzahor et al., 2003; Tzahor and Lassar, 2001).

Cranial paraxial mesoderm (CPM) located anterior to the somitic series provides precursors for the skeletal muscles in the head. CPM cells stream into the neighboring branchial arches (BAs, also known as pharyngeal arches), the templates of the adult craniofacial structures. Within the BAs, cranial neural crest (CNC) cells surround the muscle anlagen in a highly organized fashion.

Recent studies have begun to delineate the molecular and cellular regionalization of the head mesoderm, and its division into two distinct domains (CPM and lateral splanchnic mesoderm, SpM). In general, CPM cells display skeletal muscle potential, whereas lateral SpM cells bear cardiogenic potential, both in vitro and in vivo (Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006). Importantly, there seems to be no clear border between these domains, reflecting a dynamic continuum in these fields along the medial-lateral/dorsal-ventral axes. It has been shown in the chick that there is considerable overlap in the expression of cranial skeletal muscle markers [e.g., Myf5, Tcf21 (capsulin), Msc (MyoR), Tbx1, and Pitx2] and cardiac lineage markers (e.g., Islet1 and Nkx2.5) (Bothe and Dietrich, 2006; Nathan et al., 2008; Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006). Notably, Tbx1 and Pitx2 play a key role in cardiogenesis and craniofacial myogenesis [reviewed in (Grifone and Kelly, 2007; Tzahor, 2009)].

Nathan et al. recently extended these analyses by showing that CPM cells in the chick mainly contribute to the proximal region of the myogenic core in the 1st branchial arch, while SpM cells contribute to its distal region (Nathan et al., 2008). Subsequently, CPM-derived myoblasts in the 1st branchial arch contribute to the mandibular adductor complex (equivalent to the masseter in mammals), whereas SpM-derived myoblasts in the distal part of the arch give rise to lower (e.g., intermandibular) jaw muscles (Marcucio and Noden, 1999; Nathan et al., 2008). Furthermore, gene expression analyses in the chick uncovered a distinct molecular signature for CPM- and SpM-derived branchiomeric muscles. For example, Isl1 is expressed in the SpM-derived intermandibular anlagen, and its expression is correlated with delayed differentiation of this muscle (Nathan et al., 2008). Lineage tracing experiments in mice using Mef2c AHF-Cre (Dong et al., 2006) and Islet1-Cre alleles (Nathan et al., 2008), also corroborated the contribution of SpM cells to 1st branchial arch-derived muscles.

Adult skeletal muscle possesses a remarkable ability to regenerate, following injury. The cells that are responsible for this capacity are the satellite cells, adult stem cells positioned under the basal lamina of muscle fibers that can give rise to both differentiated myogenic cells, and also maintain their stem-ness by means of a self-renewal mechanism. Satellite cells play a key role in the routine maintenance, hypertrophy, and repair of damaged adult skeletal muscles (Buckingham, 2006; Kuang and Rudnicki, 2008; Zammit et al., 2006).

Early experiments using quail-chick chimeras suggested that the embryonic origins of adult skeletal muscles and satellite cells in the trunk may be traced to the somites (Armand et al., 1983). More recent studies have characterized the progenitors of trunk satellite cells, identifying them as Pax3/Pax7+ proliferating myoblasts in the central dermomyotome (Gros et al., 2005; Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2005; Relaix et al., 2005; Schienda et al., 2006). Cells derived from sources other than the dermomyotome, such as the bone marrow, vascular, and hematopoietic lineages, may also contribute to the satellite cell pool (Olguin et al., 2007), although the significance of such a contribution to normal and pathogenic myogenesis is far less clear.

Though it is known that myogenesis in the trunk and in the head substantially differs, embryological, molecular and cellular studies of satellite cells from the head musculature are presently lacking. In particular, the embryonic origin(s) of head muscle-associated satellite cells, as well as their differentiation potential and functions during normal and pathogenic myogenic processes, have not been explored. Muscle regeneration has been studied almost exclusively in limb muscles, although two studies demonstrated that limb and head muscles display differing regenerative capacities in their response to injury (Pavlath et al., 1998; Sinanan et al., 2004), perhaps due to developmental differences in their satellite cell populations. Gene expression profiles suggest that differences between head and trunk muscles are maintained into adulthood (Porter et al., 2006). Furthermore, muscle myopathies are differentially linked to a specific trunk or cranial region (Emery, 2002) suggesting that head muscles share properties that make them resistant to some, but more susceptible to other forms of muscle dystrophies.

In the current study, we utilized both avian and mouse models to investigate the embryonic origins of head muscle-associated satellite cells, and to explore their differentiation and regenerative potential. We show herein that muscle progenitors including satellite cells in the head, arise from distinct cellular and genetic lineages. Branchiomeric muscle-derived satellite cells share regenerative characteristics and harbor distinct differentiation potential, compared to satellite cells derived from the somites. Clarification of these fundamental issues may yield valuable developmental and clinical insights.

Results

Branchiomeric head muscles and their associated satellite cells derive from the CPM in avian embryos

Previous studies in the chick have documented the contributions of cranial paraxial mesoderm (CPM) cells to distinct head muscles (Hacker and Guthrie, 1998; Mootoosamy and Dietrich, 2002; Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006) and to the cardiac outflow tract (Noden, 1991; Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006). We first initiated long-term fate mapping of CPM cells in chick embryos by injecting replication-defective retroviruses into the CPM at St. 8 (~E1.5), followed by whole-mount detection of the reporter gene at E14 (Supplementary Figure 1, A–D). Our results demonstrated widespread labeling of distinct muscles and bones (e.g., the mandibular adductor, intermandibular muscle, dorsal oblique muscle, and frontal bone) derived from the CPM, in agreement with previous fate-mapping experiments (Evans and Noden, 2006).

We next employed a quail-chick transplantation approach to explore the origin(s) of craniofacial satellite cells in various head muscles (Figure 1A). Based on the previous viral lineage experiments, either small or large grafts of CPM tissue from a quail donor were implanted into the equivalent area in stage-matched chick embryos (St. 8, in order to prevent the incorporation of neural crest cells into the CPM that occurs at ~ St. 9) and embryos were left to develop to hatching (E21/P1). Six post-hatch chimeras were further analyzed by immunostaining with the quail-specific antibodies QCPN and MyHC (Myosin Heavy Chain) on head cryo-sections. In large graft chimeras (n=4), quail cells were detected in both BA1 derivatives, and extraocular muscles such as the mandibular adductor and dorsal oblique (Figure 1D–E), whereas in small graft chimeras (n=2) only BA1 derivatives were seen (Figure 1F).

Figure 1. Head muscles and their associated satellite cells share a common mesoderm origin.

A,B, Diagrams of the quail–chick small and large grafts (B) experiments suggesting that quail myoblasts contributed myonuclei and satellite cells in proportion to the graft size. C, A cartoon depicting selected muscle groups in an adult chick head. Green dots in the dorsal oblique (2) and mandibular adductors (3) represent quail nuclei. The dashed line indicates the plane of sectioning. D–F, Transverse sections stained for MyHC (red), quail-specific marker QCPN (green), and DAPI (blue) of eye and mastication muscles from post-hatch quail–chick chimera, using either large (D–E) or small (F) grafts. The dashed line indicates a region with high concentration of quail nuclei. G–I, Muscle sections (D–F) are followed by their respective higher magnifications stained with QPCN (peri-nuclear, green), Pax7 (nuclear, red), DAPI (blue) and laminin (Lam, white). Quail mesoderm-derived Pax7+ satellite cells located under the basal lamina are marked by full arrowhead; chick-derived satellite cells (empty arrowhead) can be seen in the small graft experiment (I). Scale bars, 150 μm (G), 5 μm (H–J).

In order to label satellite cells of quail origin, co-immunostaining of QCPN, DAPI, Pax7 and laminin was performed. In large graft experiments, 90% (83%–98%) of satellite cells (Pax7+, positioned under the basal lamina) were of quail origin (QCPN+) in both eye and branchiomeric muscles (Figure 1G–H). QCPN− satellite cells would suggest that these cells originated elsewhere or, more likely, resulted from the antibody’s limited sensitivity. In the small graft experiments, we noticed that both myonuclei and satellite cells originating from the graft were not evenly distributed within the chimeric muscle, but rather concentrated in a specific area. Our findings suggest that both muscle and satellite cell progenitors journey together, maintaining their spatial relationships during development. These results further indicate that in avian embryos, head muscles and their associated satellite cells arise from common origins in the embryonic cranial paraxial mesoderm.

Trunk (Pax3+) and cranial (Mesp1+) skeletal muscles and satellite cells derive from separate genetic lineages

The genetic program that controls myogenesis in the head differs considerably from that of the trunk (see Introduction). In order to assess whether similar genetic differences appear in satellite cells originating in either trunk or cranial skeletal muscles, we used the MesP1Cre mouse to label head muscles (e.g., masseter; Figure. 2A) and the Pax3Cre mouse to label trunk (limb) muscles (e.g., gastrocnemius; Figure. 2J). Although none of these mouse Cre lines are absolutely specific to a particular lineage, the combination of the two lines yielded insights into the origins of satellite cells in the head and trunk (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cranial (MesP1+) and trunk (Pax3+) derived muscles and satellite cells are genetically distinct.

A, A cartoon of skeletal muscles derived from Mesp1Cre; RosaYFP crosses depicting representative trunk and head muscles, gastrocnemius (Gas) and masseter (Mas), respectively. B–I, Muscle and satellite cell analyses in a P10 Mesp1Cre; RosaYFP mouse reveal that the gastrocnemius is YFP− (B) whereas the masseter is YFP+ (F). C–I, Immunofluorescence of transverse sections in these muscles showing both myofibers and associated satellite cells (arrowheads). J, A similar cartoon of Pax3Cre; RosaYFP crosses. K–R, Muscle and satellite cell analyses in P10 Pax3Cre; RosaYFP mice. The gastrocnemius muscle and associated satellite cells (arrowheads) are YFP+ (K,N) whereas the masseter is YFP- (O,R). Other Pax3− derived lineages such as the neural crest are revealed by the YFP+ staining in the facial nerve (FN). Scale bars: 5 μm.

In the mouse, lineage analyses using Pax3Cre (Engleka et al., 2005) or other Pax3 alleles revealed that trunk skeletal muscles (and their associated satellite cells) derive from Pax3+ cells (Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2005; Relaix et al., 2005; Schienda et al., 2006). Moreover, Pax3 marks neuronal lineages and neural crest cells (Engleka et al., 2005). It has been suggested that cranial neural crest cells expressing both Pax3 and Pax7 have arisen from multipotent embryonic stem cells capable of giving rise to many cell types, including satellite cells (Pierret et al., 2006). The MesP1 lineage marks the cardio-craniofacial mesoderm field, encompassing cardiac mesoderm, endothelial progenitors, and the cranial mesoderm, as well as some anterior somites that contribute to tongue skeletal muscles the (Dong et al., 2006; Kitajima et al., 2000; Saga et al., 1996; Saga et al., 1999).

Crossing MesP1Cre with the RosaYFP reporter revealed extensive labeling of the masseter but not hind-limb (gastrocnemius) muscles (Figure 2B,F). Co-immunostaining of DAPI, Pax7, laminin and YFP on cryo-sections of the masseter from a MesP1Cre; RosaYFP postnatal mouse at P10 clearly revealed that satellite cells in this muscle derive from MesP1+ cells (Figure 2G–I). Similarly, the gastrocnemius (but not the masseter), as well as its satellite cells, were labeled in a Pax3Cre; RosaYFP mouse at P10 (Figure 2L–N). Taken together, our results demonstrate that trunk (Pax3+) and cranial (MesP1+) skeletal muscles and satellite cells derive from separate genetic lineages.

To trace the route that cranial muscle progenitors follow in order to become satellite cells, we analyzed these myogenic progenitors at early (E11.5, E13.5, E15.5) and late embryonic and postnatal stages (E16.5, E18.8, P10; Supplementary Figure 2). We labeled muscle progenitors in the head mesoderm by crossing MesP1; RosaYFP (head mesoderm) in combination with the Myf5nlacZ/+ allele, which marks the myonuclei (Tajbakhsh et al., 1996). Within the Myf5+ population, BrDU+ cells (proliferating myoblasts) appeared as a salt-and-pepper pattern, without a clear proliferative compartment (Supplementary Figure 2A–F) as seen in the dermomyotome of somites (Gros et al., 2005; Relaix et al., 2005). As expected, we observed a significant decrease in myoblast proliferation in the myogenic core within this embryonic window, as myogenic cells start to differentiate (Supplementary Figure 2G). We then investigated the maturation of the post-mitotic muscle fibers, and the positioning of satellite cells underneath the basal lamina (Supplementary Figure 2H–N), finding parallels in the dynamics observed in trunk satellite cells (Gros et al., 2005; Relaix et al., 2005).

Lineage heterogeneity within the head musculature and satellite cells

Recent loss-of-function and lineage tracing studies highlight the emerging heterogeneity in cranial muscle developmental programs (Dong et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2002; Nathan et al., 2008; Shih et al., 2007). The assembly of distinct genetic lineages in the head musculature could contribute to the developmental heterogeneity observed. To investigate this issue, we performed a comparative lineage analysis of Myf5Cre, Pax3Cre, MesP1Cre, Isl1Cre and, Nkx2.5Cre mouse lines crossed with the Z/EG or RosaYFP reporter lines (Figure 3A–E).

Figure 3. Genetic heterogeneity of craniofacial muscles and satellite cells: Evidence of Isl1-derived satellite cells in branchiomeric muscles.

A–E, Transverse sections of E16.5 mouse heads stained for MyHC (red), GFP/YFP (green), and DAPI (blue) of MesP1Cre (A), Pax3Cre (B), Isl1Cre (C) Nkx2.5Cre (D) and Myf5Cre (E) mice, crossed with Z/EG or RosaYFP (D) reporter lines. F, An anatomical cartoon of adult mouse head highlighting the lineage composition of distinct craniofacial muscle groups. G–V, Immunofluorescence of transverse sections in various cranial muscles in the Isl1Cre; RosaYFP (G–R) and the masseter in the VE-CadCre; RosaYFP (S–V) mice. YFP+ cells are shown in green, Pax7+ (red), DAPI+ (blue) and laminin (Lam, white). Arrowheads and empty arrowheads indicate YFP+ and YFP− satellite cells, respectively. S–V, Immunofluorescence for the VE-Cad (GFP) along with skeletal muscle (S, MyHC), satellite cells (T, Pax7 marked by empty arrowheads), smooth muscle (U, αSMA) and newly formed blood vessels (V, CD34). W, A table summarizing the percentage of YFP+ satellite cells in distinct YFP+ head muscles (green background). Scale bar: 5 μm.

Coronal paraffin sections of E16.5 embryos from each of these crosses were immunostained with DAPI, MyHC and GFP/YFP. In this setting, GFP/YFP marked all the cells in which cre-dependent recombination occurred, whereas yellow staining resulted from the overlay between the GFP/YFP (green) and MyHC (red) staining. This analysis enabled us to draw lineage maps of the craniofacial anatomy (Figure 3F): eye muscles (Myf5+, MesP1+); mastication muscles (Myf5+, MesP1+, Isl1+, Nkx2.5+), and tongue muscles (Myf5+, MesP1+, Pax3+). Both Isl1 and Nkx2.5-derived cells contribute to branchiomeric muscles; jaw-opening muscles at the base of the mandible (mylohyoid and digastric); jaw-closing mastication muscles (masseter, pterygoid and temporalis, albeit to a lesser extent; compare the yellow color in the digastric to the orange color in the masseter); and some BA2-derived muscles controlling facial expression, in agreement with our previous findings [Figure 3C–D; (Nathan et al., 2008)]. Isl1 lineage-derived cells were absent from the intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles. In contrast, tongue muscles were strongly positive (yellow) in both Pax3Cre and Nkx2.5Cre crosses. These results are consistent with the somitic origin of these muscles (Pax3+), and the lack of Pax3 expression in other head muscle progenitors. Importantly, Nkx2.5 is expressed the tongue (Kasahara et al., 1998; Lints et al., 1993; Moses et al., 2001) but not in the occipital somites, therefore we did not consider it part of the tongue muscle lineage.

The Isl1 cell lineage contributes to satellite cells within distinct branchiomeric muscles

We next analyzed the contribution of distinct myogenic lineages to satellite cells in various head muscles of P10 mice (Figure 3G–R; the results of these analyses are summarized in panel W). The percentage of satellite cells in each muscle was calculated as the number of YFP+/Pax7+ cells positioned under the basal lamina, relative to the total number of satellite cells in the same region. In agreement with our results concerning trunk and cranial myogenesis (Figure 2), MesP1-derived cells contributed to satellite cells in all head muscles, including the tongue, while Pax3-derived cells contributed only to satellite cells of tongue muscles (Figure 3W). The Isl1-derived cell lineage contributed to 100 and 90 percent of satellite cells in the anterior digastric and the masseter, respectively, but not to tongue or eye muscles (Figure 3W). Examples of Isl1 lineage-derived satellite cells in distinct head muscles are shown in cryo-sections from Isl1Cre; RosaYFP mice at P10, stained for laminin, Pax7, DAPI and YFP (Figure 3G–R).

Because MesP1+ and Isl1+ cells contribute also to the endothelial lineage (Saga et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2007), we asked whether endothelial cells could contribute to the satellite cell pool. To this end, we analyzed VE-CadCre (Alva et al., 2006) crossed with RosaYFP (Figure 3S–W). Whereas we could not detect VE-Cad lineage-derived skeletal muscles (Figure 3S), satellite cells (Figure 3T), or smooth muscle cells surrounding blood vessels (Figure 3U), the VE-Cad lineage contributed to the endothelium of vessels and overlapped with CD34 expression, a marker for newly formed blood vessels (Figure 3V). Based on this genetic tool, we can accordingly rule out a significant endothelial contribution to satellite cells in both head and trunk. Taken together, our results in both avian and mouse models demonstrate that trunk and cranial skeletal muscles and satellite cells derive from separate genetic lineages and cellular origins. In addition, our data reveal that the satellite cells are developmentally linked to their embryonic muscle origins. In other words, we could not find any YFP+ satellite cells in YFP− muscles. Our findings provide genetic support for the notion that somites, cranial neural crest and endothelial derived cells do not contribute to satellite cells in the head (except for the tongue muscles, that derive from occipital somites). We further show that the Isl1 cell lineage, which contributes to many cardiovascular lineages (Moretti et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2006) and is associated with stem and progenitor states, also contributes to satellite cells in distinct branchiomeric muscles.

Head muscle-derived satellite cells can regenerate injured limb muscles

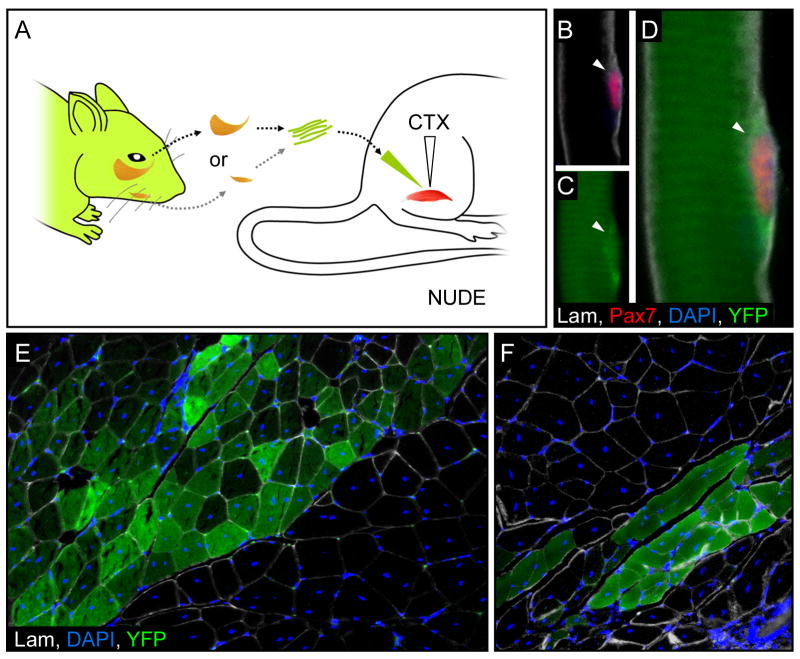

To explore the regenerative potential of head muscle satellite cells in vivo, we isolated single myofibers from the masseter and digastric of three week-old Myf5Cre; RosaYFP or Isl1Cre; RosaYFP mice, respectively, and injected them into the leg muscles of a cardiotoxin-injected, age-matched immune-deficient (nude) mouse (Figure 4A). Immunostaining of a myofiber obtained from the masseter of the Myf5Cre; RosaYFP mouse revealed a YFP+ Pax7+ satellite cell (arrowheads, Figure 4B–D). A robust presence of YFP+ myofibers could be seen in the transverse section of the gastrocnemius of the host mouse, six weeks post transplantation, demonstrating that head muscle-derived satellite cells respond to local cues in the limb to initiate regeneration (Figure 4E, and data not shown). Furthermore, in vivo transplantation of myofibers from the digastric of a Isl1Cre; RosaYFP mouse into an injured limb muscle of an immune-deficient host mouse yielded similar results (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. Branchiomeric muscle-derived satellite cells can regenerate injured limb muscles.

A, A diagram showing transplantation of single myofibers from the masseter and digastric of three week-old Myf5Cre; RosaYFP or Isl1Cre; RosaYFP mice, respectively, injected into the leg muscles of an age-matched, cardiotoxin-injected (CTX) immune-deficient (nude) mouse. B–D, Immunofluorescence of a sagital section in the masseter muscle from a Myf5Cre; RosaYFP mouse, revealing a YFP+ satellite cell (arrowhead, B–D) six-weeks post-transplantation. A transverse section in the transplanted gastrocnemius muscle revealed many YFP+ fibers originating from either the masseter of Myf5Cre; RosaYFP (E), or the digastric of Isl1Cre; RosaYFP (F).

Cardiac gene expression in head muscle-derived satellite cells

Myf5 is expressed in the vast majority of satellite cells [(Beauchamp et al., 2000; Kuang et al., 2007) and personal observations]. Accordingly, we used the Myf5Cre; RosaYFP crosses to perform RT-qPCR gene expression analyses of satellite cells freshly isolated by FACS (Supplementary Figure 3). In order to verify the purity of the sorted cells, a fraction was cultured and stained for Pax7 (data not shown). We then compared various candidate genes between branchiomeric (digastric and masseter) and trunk (gastrocnemius) derived satellite cells. While most of the tested genes display a similar pattern in both groups, the expression of TCF21 (Capsulin) in the branchiomeric-derived satellite cells was two orders of magnitude higher compared to trunk-derived cells, consistent with other studies (Sambasivan et al., 2009).

We next tested the differentiation potential of trunk and cranial satellite cells in culture (Figure 5). We previously showed that BMP4 potently induced cardiogenesis and blocked myogenesis in the head mesoderm of chick embryos, both in vitro and in vivo (Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006), whereas in somites, it blocked myogenesis [(Reshef et al., 1998), illustrated in Figure 5C)]. Accordingly, we treated trunk (gastrocnemius) and cranial (masseter and digastric) satellite cells in culture with 300 ng/mL of BMP4, and analyzed the fate of these cultures by X-gal staining of satellite cells obtained from Myf5nlacZ/+ mice (Figure 5A). Following repeated replating cycles, all satellite cell cultures were β-gal+, indicating the purity of satellite cells in our cultures. Following 7 days in differentiation medium, satellite cell fusion and differentiation led to the formation of myofibers (Figure 5A, middle panels). BMP4 induced Myf5 expression in both trunk and cranial satellite cell cultures, but also significantly reduced the number of myofibers (Figure 5A, right panels).

Figure 5. Molecular analyses of cranial and trunk- derived satellite cell cultures.

A, X-gal staining of satellite cell cultures derived from a Myf5-nLacZ mouse. B, RT-PCR and RT-qPCR analyses of satellite cells derived from selected cranial and trunk muscles, cultured with or without 200 ng/ml BMP4. C, A diagram summarizing shared and distinct effects of BMP4 on embryonic and adult, head and trunk mesoderm cells and satellite cells, respectively. gastrocnemius, (Gas); masseter (Mas); digastricus (Dig).

RT-PCR results revealed a BMP4-dependent upregulation of both Myf5 and Pax7, known proliferation markers of satellite cells, in all cultures (Figure 5B). Furthermore, BMP4 efficiently blocked myogenic differentiation in trunk-derived, but less so in cranial-derived satellite cells, shown by the downregulation of muscle differentiation markers, Myog and MyHC. In addition, BMP4 induced the expression of osteogenic markers in head muscle satellite cells, as was previously shown for trunk satellite cells treated with BMP4 [Figure 5B, (Asakura et al., 2001)]. RT-qPCR analysis of cultured satellite cells revealed that BMP4 induced greater expression of cardiac genes such as Isl1 and Tbx20 in head satellite cells, compared to those of the trunk (Figure 5B). Moreover, basal levels of Nkx2.5 were significantly higher in cultures of head satellite cells (Figure 5B, right). Together, these findings reveal both common and distinct differentiation potentials of satellite cells from trunk and head muscles (Figure 5C). The induction of Isl1 and Tbx20 in digastric-derived satellite cell cultures by BMP4 suggests that these cells retain some plasticity, similar to embryonic head mesoderm cells (Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006).

Isl1 acts as a repressor of myogenic differentiation

Isl1 likely plays several roles in the second heart field by affecting cell migration and proliferation (Cai et al., 2003); however, its effect on early myogenesis in the head has not been determined. Because the differentiation of Isl1+ SpM cells (both cardioblasts and myoblasts) comprising the second heart field/second myogenic field, respectively, is delayed within the heart and the lower jaw muscles (Cai et al., 2003; Nathan et al., 2008), it has been suggested that Isl1 represses skeletal muscle differentiation, either directly or indirectly (Tzahor, 2009). Indeed, we found that BMP4 has been shown to function as a repressor of myogensis in the head (Tirosh-Finkel et al., 2006). In addition, BMP4 beads induced Isl1 expression in BA1 of the chick, in vivo (Figure 6A–D).

Figure 6. Isl1 represses head muscle differentiation in chick embryos, in vitro and in vivo.

A, A diagram showing implantation of a bead soaked in 100 ng/ml BMP4, into the right CPM of a St.10 embryo. Whole-mount in situ hybridization for Isl1 (B–C) and the cross-section trough BA1 (D), 24h post-implantation, showing up-regulation of Isl1 in the implanted (right) BA1 (arrowheads) and down-regulation of Isl1 in the trigeminal ganglia (black arrowhead). An asterisk marks the bead in C. E, A diagram showing the CPM explant culture system. F, RT-PCR analysis of CPM explants after 0–4 days in culture. G, RCAS-Isl1 but not RCAS-GFP overexpression resulted in inhibition of myogenesis in CPM explants. H, A diagram showing retroviral injection, at the CPM of a St. 8 chick embryo, developed until E5 for further analysis. J–O, Immunofluorescence of transverse sections through BA1 in an E5 chick embryo, infected unilaterally with either control RCAS-GFP (I–K) or RCAS-Isl1 (L–N). Arrows indicate differentiating myotubes, which were partially repressed by Isl1 (empty arrow).

TG, trigeminal ganglia. BA, branchial arch.

To test whether Isl1 could block myogenic differentiation, we infected chick embryos with concentrated retroviruses (either RCAS-GFP or RCAS-Isl1), both in vitro (Figure 6E–G) and in vivo (Figure 6H–N). In culture, RT-PCR analysis showed that CPM explants underwent stepwise myogenic differentiation, as evidenced by the appearance of MyoD, Myogenin (Myog) and MyHC at day 3–4 of culture (Figure 6F). Isl1 overexpression in these CPM explants markedly blocked these myogenic differentiation genes (Figure 6G), indicating that Isl1 can repress myogenesis in vitro.

We then tested whether Isl1 could inhibit myogenesis in vivo, in early chick embryos (Figure 6H). Muscle differentiation was analyzed in transverse sections of BA1 in E5 chick embryos (Figure 6J–O). Unlike in the control GFP infected BA1 (Figure 6I–K), Isl1 overexpression inhibited expression of the skeletal muscle differentiation markers Myogenin and MyHC (Figure 6N). Taken together, our results provide compelling evidence that the Isl1 cell lineage contributes to skeletal muscle stem cell progenitors in the head. Furthermore, we found that Isl1 negatively regulates myogenic differentiation in head mesoderm, consistent with its key role in specifying cardiac and skeletal muscle progenitors. We suggest that the developmental history of Isl1-derived cells may affect their differentiation potential, an insight that could translate into advances in regenerative medicine.

Discussion

It is widely accepted that head and trunk myogenic programs vary considerably [reviewed in (Bothe et al., 2007; Grifone and Kelly, 2007; Noden and Francis-West, 2006)]. These differences persist into adulthood, as reflected in the distinct genetic signatures and susceptibility to muscle myopathies of head and trunk skeletal muscles (Emery, 2002; Porter et al., 2006). Here, we addressed an important question in the muscle field related to the embryonic origins of satellite cells (Figure 7A) in the head musculature. Comparable studies of the origins of satellite cells in trunk and limb muscles (Gros et al., 2005; Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2005; Relaix et al., 2005; Schienda et al., 2006) firmly established that somites give rise to muscle progenitors, including proliferative Pax3/Pax7 cells, some of which (the satellite cells) later become quiescent and spatially localized under the basal lamina (Figure 7C). In a similar manner, we used lineage tracing techniques in both avian and mouse models to demonstrate that head mesoderm, comprising both the CPM and the SpM, contributes to distinct head muscles and their associated satellite cells (Figure 7C). Notably, we demonstrated the robust contribution of Isl1 lineage-derived SpM cells to branchiomeric muscle, but not to extraocular-derived satellite cells (Figure 7C). These findings highlight the link between myogenesis in the early embryo, and the generation of adult muscle progenitor pools required for muscle maintenance and regeneration (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. Distinct myogenic programs in the embryo contribute to skeletal muscles and satellite cells in the head and trunk.

A. Satellite cells, located on the surface of the myofiber, beneath its basement membrane (basal lamina), serve as a source of myogenic cells for growth and repair of postnatal skeletal muscle. B. The combinatorial use of several mouse Cre lines, depicted as circles, allowed us to draw sharp boundaries between head muscle groups (tongue, mastication, eye muscles) as marked by the overlap between the lineages. The contribution of these mouse Cre lines to other mesoderm lineages is depicted in brackets. C. Muscles and satellite cells in trunk and limb derive from somites (Pax3 lineage) while branchiomeric muscles (including the mastication muscles) and their associated satellite cells derive from both CPM and SpM sources (MesP1, Isl1, and Nkx2.5 lineages). Our findings reveal the lineage signature of the head musculature and its associated satellite cell population, highlighting the overwhelming heterogeneity in these groups of muscles.

Heterogeneity in the head musculature

The genetic lineage mapping of the head musculature accomplished in this study highlights the overwhelming heterogeneity in these groups of muscles (Figure 7B). Furthermore, this lineage map corroborates, at the cellular level, our understanding of the craniofacial muscle phenotypes seen in several recent loss-of-function studies in mice. A complementary view of craniofacial muscle formation in mice, based on the dissection of the genetic programs that promote myogenesis in distinct muscles of this type (e.g., extraocular vs. branchiomeric muscles) was demonstrated by (Sambasivan et al., 2009).

Capsulin and MyoR, for example, were shown to act as upstream regulators of branchiomeric muscle development. In Capsulin/MyoR double mutants, the masseter, pterygoid, and temporalis muscles were missing, while distal BA1 muscles (e.g., anterior digastric and mylohyoid) were not affected (Lu et al., 2002). A plausible developmental explanation for this mutant phenotype is compatible with findings that branchiomeric muscles are composed of at least two myogenic lineages, CPM-derived and SpM-derived muscle cells.

In Tbx1 mutants, branchiomeric muscles (including those derived from both CPM and SpM) were frequently hypoplastic and asymmetric, whereas the extraocular and tongue muscles were not affected (Kelly et al., 2004). Our lineage analyses of the head musculature strongly indicate that both extraocular and tongue muscles derive from lineages distinct from those of branchiomeric muscles [(Figures 3 and 7B]. In Pitx2 mutants, the extraocular and mastication muscles of the BA1 are affected (Dong et al., 2006; Shih et al., 2007): SpM-derived myoblasts, marked by the Mef2c AHF-Cre lineage in the mouse (Verzi et al., 2005), were fewer in Pitx2 mutant embryos (Dong et al., 2006). The craniofacial muscle phenotype of MesP1, Isl1, and Nkx2.5 mouse mutants remains obscure as these mutants display early lethality around E10.5, due to the tight developmental link between heart and craniofacial muscle development (Tzahor, 2009).

Isl1 lineage-derived cells contribute to a broad range of cardiovascular and skeletal muscle progenitors

Isl1+ multipotent cardiovascular progenitors have been cloned from both mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells and mouse embryos. These cells, when cultured at the single-cell level, can give rise to endothelial, smooth muscle and cardiomyocyte lineages (Moretti et al., 2006; Qyang et al., 2007). The notion that Isl1 could play a similar role in the specification of satellite cells is certainly intriguing. We now report, the existence of Isl1 lineage-derived satellite cells in distinct branchiomeric muscles (Figures 3 and 7B). Moreover, these cells can regenerate injured limb muscles and display distinct molecular signature in culture, compared to limb-derived satellite cells (Figure 5). Unraveling the molecular pathways that control the progenitors’ lineage commitment and differentiation into specific types of mature cellular progeny, is critical to the successful design of cell therapies for degenerative muscle diseases (Laugwitz et al., 2008). Accordingly, we found that to some extent, BMP4 induced cardiac gene expression in Isl1 lineage-derived satellite cells isolated from the masseter and digastric muscles (Figure 5), suggesting that head and trunk satellite cell populations respond differently to surrounding cues. The observation that Isl1-expressing cells contribute to multiple cardiovascular and skeletal muscle progenitor cells raises questions as to the role of Isl1 in the specification of these lineages. We showed in chick embryos that Isl1 can block skeletal muscle differentiation in the head, both in vitro and in vivo (Figure 6), consistent with the finding that myogenic differentiation in the head is delayed, compared to myogenesis from somites (Hacker and Guthrie, 1998; Noden et al., 1999). We propose that Isl1 acts as a repressor of myogenic differentiation in the head mesoderm.

The recent discoveries in chick and mouse models of two distinct mesodermal fields (CPM and SpM), both of which contribute cells to the developing facial musculature in a specific temporal and spatial manner (Dong et al., 2006; Nathan et al., 2008), suggest that these fields are analogous to the two distinct mesodermal heart fields (Tzahor, 2009). In both cases, the second myogenic field consists of SpM cells expressing Isl1 and Nkx2.5. These Isl1+, Nkx2.5+ cells contribute to the anterior pole of the heart, as well as to the distal myogenic core of the 1st branchial arch (Cai et al., 2003; Nathan et al., 2008). Within both the heart and the lower jaw, the differentiation of Isl1-derived cells comprising the second heart field/second myogenic field, is delayed [(Marcucio and Noden, 1999; Nathan et al., 2008) and this study]. In summary, and in accordance with other studies (Cai et al., 2003; Laugwitz et al., 2005; Moretti et al., 2006; Qyang et al., 2007), Isl1 stands at a nodal point in the differentiation and lineage specification of distinct mesoderm-derived cardiovascular and skeletal muscle progenitors.

Satellite cells are specified during early developmental stages

The expression of Isl1 in head muscle progenitors is downregulated at around embryonic day 3 (E3) in the chick, and E10 in the mouse (Nathan et al., 2008). In the adult, we failed to detect Isl1 RNA and protein expression in satellite cells. Strikingly, nearly all satellite cells in the masseter and anterior digastric muscles were found to be derived from Isl1-expressing cells (Figure 3). These results strongly suggest that satellite cells are bound to an embryonic muscle anlagen and genetic program that is both region-specific (e.g., cranial and trunk) and muscle-specific (e.g., eye, mastication, tongue). For example, Pax3-derived satellite cells were found in tongue muscles derived from myoblasts arising from occipital somites (Pax3+), and not in other head muscles (Figure 3). Our findings demonstrate that the lineage map of the head musculature shares similarities with the lineage map of their associated satellite cells (Figure 3W). Importantly, our study and those of others (Gros et al., 2005; Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2005; Relaix et al., 2005) were restricted to examination of early postnatal stages for the presence of satellite cells. It is also possible that quiescent satellite cells in the adult could originate from other sources, particularly in instances of pathology (Zammit et al., 2006).

In the trunk, self-renewing embryonic muscle progenitors can be identified by the expression of Pax3 and, later, Pax7; however, they lack expression of Myf5 and MyoD (Zammit et al., 2006). In the head, on the other hand, Pax3 is not expressed in muscle progenitors, and Pax7 expression ensues only after Myf5 expression (Hacker and Guthrie, 1998; Nathan et al., 2008). It is tempting to speculate that Isl1 plays a role in regulating the quiescence and self-renewal of muscle progenitors in the head, analogous to Pax3/Pax7 in trunk skeletal muscles. This hypothesis is consistent with the notion that the head mesoderm expresses a group of “suspected” stimulators of cell proliferation and repressors of differentiation, such as Pitx2, MyoR, capsulin and Tbx1 (Bothe and Dietrich, 2006) that could also fulfill these criteria in other head muscles. While in the head, there are several myogenic regulators, such as Isl1, that could act upstream of Pax7 in different muscle anlagen, it seems that in the trunk, all satellite cell progenitors adhere to a single developmental program (Tzahor, 2009).

Unlike skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle is believed to lack regenerative potential. As a result, myocardial infarction (heart attack) is often accompanied by its severe loss of cardiac muscle tissue. When the pool of contractile cells is depleted below a critical threshold, heart failure often ensues (Laflamme and Murry, 2005). Limb-derived satellite cells have been used in the clinic to treat patients following myocardial infarction, but the overall benefit of the transplanted satellite cells to these patients was unclear, as the satellite cells remained committed to a skeletal muscle fate (Laflamme and Murry, 2005). Based on our findings, and the key role played by Isl1 in various cardiovascular lineage progenitors, we propose that Isl1 lineage-derived satellite cells could provide a source of cells to repair cardiac damage, as well as muscle dystrophies that mainly affect the trunk.

Experimental Procedures

Quail/chick transplantation, viral injections and bead implantation

Chicken eggs and Japanese quail eggs were incubated until embryos reached 2–3 somites (St. 8-). A piece of quail head mesoderm and ectoderm was isolated from the right side of the embryo using a tungsten needle, and transplanted into a stage-matched chick donor. Chimeras were harvested at E18 or at hatching (P1). In order to label satellite cells of quail origin, immunostaining of QCPN, DAPI, Pax7 and laminin was performed.

To infect the CPM in vivo, concentrated replication-defective retroviruses RIS-AP, or replication-competent RCAS-Isl1 and RCAS-GFP were injected into the CPM of St. 8 chick embryos. Retrovirally infected chicks were harvested at E5 or E14.

Mouse Lines

Pax3Cre (Engleka et al., 2005), MesP1Cre (Saga et al., 1996), Isl1Cre (Sun et al., 2007), Nkx2.5Cre (Moses et al., 2001), Myf5Cre (Tallquist et al., 2000) and VE-CadherinCre (Alva et al., 2006) mice were used in this study, and crossed with either Z/EG reporter (Novak et al., 2000), or Rosa26YFP reporter (Srinivas et al., 2001), which yield an efficient recombination, compared to the Z/EG reporter. Myf5-nLacZ mice (Tajbakhsh et al., 1996) were also used.

Immunofluorescence, X-gal and AP staining

Mouse craniofacial tissues were fixed and sectioned at 7μm. Paraffin sections were deparaffinized using standard methods, and subjected to sodium citrate antigen retrieval. Sections were blocked with either 5% horse serum or a mouse-on-mouse (MOM) blocking kit (Vector Labs), and incubated with monoclonal anti-Pax7, QCPN, Isl1, MF20 and BrDU (DSHB), biotinylated goat anti-GFP (1:100, Abcam), rabbit anti-laminin (1:100, L9393, Sigma) and rabbit anti-β galactosidase (1:200, Cappel). Secondary antibodies used were Cy2, Cy3- or Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG, Fab FITC-conjugated anti-mouse, Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse Igg1, and Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse Igg2b (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Quail/chick chimera sections were first labeled with anti-QCPN and anti-laminin, followed by anti-mouse Fab FITC and Cy5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) labeling. Sections were then fixed with PFA and stained with anti-Pax7 directly conjugated to Ana tag™555 (AnaSpec) and DAPI.

X-gal and AP staining was performed according to standard procedures. Images were obtained with a Nikon 90i florescent microscope using the Image Pro Plus program (Media Cybernetics, Inc.), assembled using Photoshop CS software (Adobe) and PTGui stitching software (http://www.ptgui.com). Unless stated otherwise, quantification of the staining results was based on analysis of 6 sections, from at least two different embryos.

Satellite cell culture and differentiation

Satellite cells were isolated from various skeletal muscles in mice. Female Myf5-nLacZ (Tajbakhsh et al., 1996), ICR or Myf5Cre; RosaYFP 3–4 weeks old mice were sacrificed, and muscle tissues were dissected and minced, followed by enzymatic dissociation at 37°C with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA for 30 minutes. Cells were collected, and trypsinization of the remaining undigested tissue was repeated three times. After 50μm filtration (Cell Tricks) cells were FACS isolated using a FACSAria, or cultured in proliferation medium (BIO-AMF-2, Biological Industries, Ltd.). To isolate satellite cells from other muscle-derived stem cells, a pre-plating technique was employed (Sarig et al., 2006), which separates myogenic cells based on their adherence to collagen-coated flasks. Cells were grown in DMEM containing 5% horse serum (Biological Industries) for 7 days, with or without 300 ng/ml BMP4 (Sigma). RNA was isolated from cells with an RNeasy Mini-Kit (QIAGEN), followed by reverse transcription using M-LV RT (BioLab). cDNA was used as a template for RT-PCR with green master mix (Promega), followed by PCR amplification using primers for osteogenic, cardiac, and skeletal muscle markers (primer sequences are available upon request). For RT-qPCR we used SYBER Green qPCR kit (Finnzymes). Primer sets were selected using Universal ProbeLibrary Assay Design Center (Roche Applied Science), and the qPCR reaction was done by Step One Plus Real time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Muscle injury and fiber transplantations

To induce muscle injury, cardiotoxin (CTX, 0.1 ml of 10 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the gastrocnemius muscle of 6 week-old nude female mice (Collins et al., 2005). A day later, single myofibers were isolated from selected muscles in different mouse genetic lines. Approximately 100 fibers were injected into the area previously injected with CTX, using a 25-gauge needle. Mice were sacrificed 6 weeks later, and the injected muscle was removed and analyzed using immunofluorescence staining.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants to E.T. from the Helen and Martin Kimmel Institute for Stem Cell Research; the Minerva Foundation, with funding from the Federal German Ministry for Education and Research; the Association Française Contre les Myopathies; the Israel Science Foundation; and the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation. We thank Robert Kelly, Carmen Birchmeier and Margaret Buckingham for insightful discussions, and Rachel Sarig, Ami Navon and Orna Halevy for technical and scientific input.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alva JA, Zovein AC, Monvoisin A, Murphy T, Salazar A, Harvey NL, Carmeliet P, Iruela-Arispe ML. VE-Cadherin-Cre-recombinase transgenic mouse: a tool for lineage analysis and gene deletion in endothelial cells. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:759–767. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armand O, Boutineau AM, Mauger A, Pautou MP, Kieny M. Origin of satellite cells in avian skeletal muscles. Arch Anat Microsc Morphol Exp. 1983;72:163–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura A, Komaki M, Rudnicki M. Muscle satellite cells are multipotential stem cells that exhibit myogenic, osteogenic, and adipogenic differentiation. Differentiation. 2001;68:245–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp JR, Heslop L, Yu DS, Tajbakhsh S, Kelly RG, Wernig A, Buckingham ME, Partridge TA, Zammit PS. Expression of CD34 and Myf5 defines the majority of quiescent adult skeletal muscle satellite cells. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1221–1234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothe I, Ahmed MU, Winterbottom FL, von Scheven G, Dietrich S. Extrinsic versus intrinsic cues in avian paraxial mesoderm patterning and differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2397–2409. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothe I, Dietrich S. The molecular setup of the avian head mesoderm and its implication for craniofacial myogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2845–2860. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M. Myogenic progenitor cells and skeletal myogenesis in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, Evans S. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, Sun X, Liu W, Ai D, Klysik E, Lu MF, Hadley J, Antoni L, Chen L, Baldini A, et al. Pitx2 promotes development of splanchnic mesoderm-derived branchiomeric muscle. Development. 2006;133:4891–4899. doi: 10.1242/dev.02693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engleka KA, Gitler AD, Zhang M, Zhou DD, High FA, Epstein JA. Insertion of Cre into the Pax3 locus creates a new allele of Splotch and identifies unexpected Pax3 derivatives. Dev Biol. 2005;280:396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DJ, Noden DM. Spatial relations between avian craniofacial neural crest and paraxial mesoderm cells. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1310–1325. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grifone R, Kelly RG. Heartening news for head muscle development. Trends Genet. 2007;23:365–369. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros J, Manceau M, Thome V, Marcelle C. A common somitic origin for embryonic muscle progenitors and satellite cells. Nature. 2005;435:954–958. doi: 10.1038/nature03572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker A, Guthrie S. A distinct developmental programme for the cranial paraxial mesoderm in the chick embryo. Development. 1998;125:3461–3472. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara H, Bartunkova S, Schinke M, Tanaka M, Izumo S. Cardiac and extracardiac expression of Csx/Nkx2.5 homeodomain protein. Circ Res. 1998;82:936–946. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.9.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassar-Duchossoy L, Giacone E, Gayraud-Morel B, Jory A, Gomes D, Tajbakhsh S. Pax3/Pax7 mark a novel population of primitive myogenic cells during development. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1426–1431. doi: 10.1101/gad.345505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RG, Jerome-Majewska LA, Papaioannou VE. The del22q11.2 candidate gene Tbx1 regulates branchiomeric myogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2829–2840. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima S, Takagi A, Inoue T, Saga Y. MesP1 and MesP2 are essential for the development of cardiac mesoderm. Development. 2000;127:3215–3226. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.15.3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Kuroda K, Le Grand F, Rudnicki MA. Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell. 2007;129:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Rudnicki MA. The emerging biology of satellite cells and their therapeutic potential. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme MA, Murry CE. Regenerating the heart. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:845–856. doi: 10.1038/nbt1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Caron L, Nakano A, Chien KR. Islet1 cardiovascular progenitors: a single source for heart lineages? Development. 2008;135:193–205. doi: 10.1242/dev.001883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Lam J, Gruber P, Chen Y, Woodard S, Lin LZ, Cai CL, Lu MM, Reth M, et al. Postnatal isl1+ cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature. 2005;433:647–653. doi: 10.1038/nature03215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lints TJ, Parsons LM, Hartley L, Lyons I, Harvey RP. Nkx-2.5: a novel murine homeobox gene expressed in early heart progenitor cells and their myogenic descendants. Development. 1993;119:969. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JR, Bassel-Duby R, Hawkins A, Chang P, Valdez R, Wu H, Gan L, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Control of facial muscle development by MyoR and capsulin. Science. 2002;298:2378–2381. doi: 10.1126/science.1078273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucio RS, Noden DM. Myotube heterogeneity in developing chick craniofacial skeletal muscles. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:178–194. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199903)214:3<178::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootoosamy RC, Dietrich S. Distinct regulatory cascades for head and trunk myogenesis. Development. 2002;129:573–583. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti A, Caron L, Nakano A, Lam JT, Bernshausen A, Chen Y, Qyang Y, Bu L, Sasaki M, Martin-Puig S, et al. Multipotent embryonic isl1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell. 2006;127:1151–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses KA, DeMayo F, Braun RM, Reecy JL, Schwartz RJ. Embryonic expression of an Nkx2-5/Cre gene using ROSA26 reporter mice. Genesis. 2001;31:176–180. doi: 10.1002/gene.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan E, Monovich A, Tirosh-Finkel L, Harrelson Z, Rousso T, Rinon A, Harel I, Evans SM, Tzahor E. The contribution of Islet1-expressing splanchnic mesoderm cells to distinct branchiomeric muscles reveals significant heterogeneity in head muscle development. Development. 2008;135:647–657. doi: 10.1242/dev.007989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. Origins and patterning of avian outflow tract endocardium. Development. 1991;111:867–876. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.4.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM, Francis-West P. The differentiation and morphogenesis of craniofacial muscles. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1194–1218. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM, Marcucio R, Borycki AG, Emerson CP., Jr Differentiation of avian craniofacial muscles: I. Patterns of early regulatory gene expression and myosin heavy chain synthesis. Dev Dyn. 1999;216:96–112. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199910)216:2<96::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak A, Guo C, Yang W, Nagy A, Lobe CG. Z/EG, a double reporter mouse line that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein upon Cre-mediated excision. Genesis. 2000;28:147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olguin HC, Yang Z, Tapscott SJ, Olwin BB. Reciprocal inhibition between Pax7 and muscle regulatory factors modulates myogenic cell fate determination. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:769–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlath GK, Thaloor D, Rando TA, Cheong M, English AW, Zheng B. Heterogeneity among muscle precursor cells in adult skeletal muscles with differing regenerative capacities. Dev Dyn. 1998;212:495–508. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199808)212:4<495::AID-AJA3>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierret C, Spears K, Maruniak JA, Kirk MD. Neural crest as the source of adult stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:286–291. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JD, Israel S, Gong B, Merriam AP, Feuerman J, Khanna S, Kaminski HJ. Distinctive morphological and gene/protein expression signatures during myogenesis in novel cell lines from extraocular and hindlimb muscle. Physiol Genomics. 2006;24:264–275. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00234.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qyang Y, Martin-Puig S, Chiravuri M, Chen S, Xu H, Bu L, Jiang X, Lin L, Granger A, Moretti A, et al. The renewal and differentiation of Isl1+ cardiovascular progenitors are controlled by a Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell, Stem Cell. 2007;1:165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M. A Pax3/Pax7-dependent population of skeletal muscle progenitor cells. Nature. 2005;435:948–953. doi: 10.1038/nature03594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshef R, Maroto M, Lassar AB. Regulation of dorsal somitic cell fates: BMPs and Noggin control the timing and pattern of myogenic regulator expression. Genes Dev. 1998;12:290–303. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki MA, Schnegelsberg PN, Stead RH, Braun T, Arnold HH, Jaenisch R. MyoD or Myf-5 is required for the formation of skeletal muscle. Cell. 1993;75:1351–1359. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90621-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga Y, Hata N, Kobayashi S, Magnuson T, Seldin MF, Taketo MM. MesP1: a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein expressed in the nascent mesodermal cells during mouse gastrulation. Development. 1996;122:2769–2778. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga Y, Kitajima S, Miyagawa-Tomita S. Mesp1 expression is the earliest sign of cardiovascular development. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2000;10:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saga Y, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Takagi A, Kitajima S, Miyazaki J, Inoue T. MesP1 is expressed in the heart precursor cells and required for the formation of a single heart tube. Development. 1999;126:3437–3447. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambasivan R, Gayraud-Morel B, Dumas G, Cimper C, Paisant S, Kelly R, Tajbakhsh S. Distinct regulatory cascades govern extraocular and branchiomeric muscle progenitor cell fates. Dev Cell. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.008. accepted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienda J, Engleka KA, Jun S, Hansen MS, Epstein JA, Tabin CJ, Kunkel LM, Kardon G. Somitic origin of limb muscle satellite and side population cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:945–950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510164103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih HP, Gross MK, Kioussi C. Cranial muscle defects of Pitx2 mutants result from specification defects in the first branchial arch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5907–5912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701122104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinanan AC, Hunt NP, Lewis MP. Human adult craniofacial muscle-derived cells: neural-cell adhesion-molecule (NCAM; CD56)-expressing cells appear to contain multipotential stem cells. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2004;40:25–34. doi: 10.1042/BA20030185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Liang X, Najafi N, Cass M, Lin L, Cai CL, Chen J, Evans SM. Islet 1 is expressed in distinct cardiovascular lineages, including pacemaker and coronary vascular cells. Dev Biol. 2007;304:286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S, Rocancourt D, Buckingham M. Muscle progenitor cells failing to respond to positional cues adopt non-myogenic fates in myf-5 null mice. Nature. 1996;384:266–270. doi: 10.1038/384266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh S, Rocancourt D, Cossu G, Buckingham M. Redefining the genetic hierarchies controlling skeletal myogenesis: Pax-3 and Myf-5 act upstream of MyoD. Cell. 1997;89:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Weismann KE, Hellstrom M, Soriano P. Early myotome specification regulates PDGFA expression and axial skeleton development. Development. 2000;127:5059–5070. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.23.5059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh-Finkel L, Elhanany H, Rinon A, Tzahor E. Mesoderm progenitor cells of common origin contribute to the head musculature and the cardiac outflow tract. Development. 2006;133:1943–1953. doi: 10.1242/dev.02365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzahor E. Heart and craniofacial muscle development: a new developmental theme of distinct myogenic fields. Dev Biol. 2009;327:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzahor E, Kempf H, Mootoosamy RC, Poon AC, Abzhanov A, Tabin CJ, Dietrich S, Lassar AB. Antagonists of Wnt and BMP signaling promote the formation of vertebrate head muscle. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3087–3099. doi: 10.1101/gad.1154103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzahor E, Lassar AB. Wnt signals from the neural tube block ectopic cardiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:255–260. doi: 10.1101/gad.871501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verzi MP, McCulley DJ, De Val S, Dodou E, Black BL. The right ventricle, outflow tract, and ventricular septum comprise a restricted expression domain within the secondary/anterior heart field. Dev Biol. 2005;287:134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Cai CL, Lin L, Qyang Y, Chung C, Monteiro RM, Mummery CL, Fishman GI, Cogen A, Evans S. Isl1Cre reveals a common Bmp pathway in heart and limb development. Development. 2006;133:1575–1585. doi: 10.1242/dev.02322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit PS, Partridge TA, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. The skeletal muscle satellite cell: the stem cell that came in from the cold. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1177–1191. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6R6995.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.