Abstract

We examine the effects of Head Start participation on parenting and child maltreatment in a large and diverse sample of low-income families in large U.S. cities (N = 2,807), using rich data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS). To address the issue of selection bias, we employ several analytic approaches, including logistic regressions with a rich set of pretreatment controls as well as propensity score matching models, comparing the effects of Head Start to any other arrangements as well as specific types of other arrangements. We find that compared to children who did not attend Head Start, children who did attend Head Start are less likely to have low access to learning materials and less likely to experience spanking by their parents at age five. Moreover, we find that the effects of Head Start vary depending on the specific type of other child care arrangements to which they are compared, with the most consistently beneficial protective effects seen when Head Start is compared to being home in exclusively parental care.

Keywords: Head Start, parenting, child maltreatment, propensity score matching

Child maltreatment affects an estimated 3.5 million children in the United States each year, and young, low-income children are at particularly high risk (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2009). Yet, we know remarkably little about what programs might effectively reduce the risk of maltreatment for vulnerable young children (Waldfogel, 2009). Many existing preventive programs have not been studied, and others have been studied without rigorous research designs or adequate data.

Among the programs potentially available to prevent maltreatment among young children, Head Start is particularly relevant. Head Start is the largest publicly supported child care program in the United States and is targeted to low-income children, as well as children with disabilities, both groups at high risk for maltreatment. There are many reasons to believe Head Start might improve parenting and reduce maltreatment. In addition to reducing parental stress and opportunities for maltreatment by providing out-of-home care for children, Head Start also promotes parental involvement and parent education, which might improve parenting and reduce the use of abusive discipline or neglectful behaviors. In addition, like other child care programs, Head Start might serve a monitoring function; parents may be deterred from abusing or neglecting their children because Head Start staff might observe that behavior and report the family to child protective services (CPS).

However, in spite of the many studies of Head Start, little research has been conducted on its effects on parenting and child maltreatment, and the research that has been conducted is limited in three respects. First, available studies have focused on spanking, often finding protective effects of Head Start. These studies, however, have not included standardized instruments to measure abuse and neglect directly. While this omission is understandable, given the rarity of abuse and neglect data in population samples, it leaves open the question whether Head Start reduces abuse and neglect. Second, selection bias remains a perennial challenge. Head Start serves the most disadvantaged children and so may be associated with inadequate parenting and maltreatment. To date, only one randomized controlled study of Head Start has been carried out. That study, the Head Start Impact Study, suggested that Head Start reduces parents’ use of spanking but like other studies did not examine child maltreatment. Third, prior studies, including the Head Start Impact Study, have not clearly defined the counterfactual, or reference group with which Head Start is being compared. Failing to specify the counterfactual may result in inconsistent findings across studies depending on the alternative care arrangements children in the samples have received.

In this study, we analyze Head Start and abuse and neglect using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS). We examine the effects of Head Start participation on parenting and child maltreatment when children are five years old. As detailed below, we use standardized instruments to measure parenting and child maltreatment. We employ several analytic methods, including both logistic regression models with rich controls and a propensity score matching method, to address the issue of selection bias. We estimate the average effects of Head Start by comparing Head Start participants to all non-participants and also compare the former to children in other specific types of care arrangements (i.e., exclusively parental care, pre-kindergarten programs, other center-based care, or other non-parental care).

Prior Research on Head Start and Child Maltreatment

Child maltreatment has long been recognized as a major social problem (Baumrind, 1994; Chen, Dunne, & Han, 2004; Finkelhor & Korbin, 1988; Hahm & Guterman, 2001; Park, 2001; Tang, 2002; Zhai & Gao, 2009). In 2007, more than 3.5 million children were the subject of child abuse or neglect reports and were investigated or assessed by CPS agencies. Eight hundred thousand were identified as victims of maltreatment, suggesting a victimization rate of 10.6 per 1,000 children in the population (USDHHS, 2009). Young children are at highest risk for maltreatment. Other factors associated with increased risk include low family income and child disability (Waldfogel, 1998).

Child maltreatment has been found to be negatively associated with children’s short- and long-term developmental outcomes, including those in the social, emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and general health domains (see research and reviews by Berger & Waldfogel, 2010; Bogat et al., 2006; Suglia, Enlow, Kullowatz, & Wright, 2009; Taylor, Guterman, Lee, & Rathouz, 2009; Wolfe et al., 2003; Zhai & Gao, 2009). Thus, identifying services that might reduce maltreatment is important. However, to date, we know remarkably little about such services (Waldfogel, 2009). Relatively few studies of preventive services have been carried out, and those have not produced valid estimates of causal effects, due to limitations of data or methods or both.

Given the elevated risk of maltreatment facing young children, understanding the role of early childhood care and education programs in improving parenting skills and preventing child maltreatment is particularly relevant. Child protection agencies have long viewed child care as a service to prevent maltreatment of young children, as well as to promote parenting skills and child health and development. For example, the Alaska CPS agency explains that “protective day care services provide day care to children of families where the children are at risk of being abused or neglected. The services are designed to lessen that risk by providing child care relief, offering support to both the child and parents, monitoring for occurring and reoccurring maltreatment, and providing role models to families” (State of Alaska, Office of Children’s Services [OCS], 2008).

Current research provides some evidence about the effects of Head Start on parenting and child maltreatment but is also plagued by several limitations. The strongest evidence comes from the Head Start Impact Study, the only study to assess the impacts of Head Start using a random assignment method. This study found that after one year’s participation, parents of 3-year olds who had been randomly assigned to Head Start were less likely to report spanking their child in the prior week and reported spanking less frequently (however, there were not effects on spanking for parents of four year olds); effects were strongest for teen mothers (USDHHS, 2005). In related research on younger children (age 0 to 3), reduced spanking was also found in a random assignment study of the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP), an early child care program for low birth-weight children (Smith & Brooks-Gunn, 1997) and in a random assignment study of the Early Head Start program, which provides in-home and/or child care services to low-income infants and toddlers (Love et al., 2005).

Prior observational studies provide some suggestive evidence. Analyses of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten (ECLS-K) cohort, a large nationally representative sample of children entering kindergarten in the fall of 1998, found that parents of children who had attended Head Start were more likely to report that they never used spanking than were parents of children who had not attended any child care center (Magnuson & Waldfogel, 2005). In addition, Head Start parents were more likely to say they would not use spanking in a hypothetical situation.

However, measuring effects on spanking is not the same as measuring effects on other aspects of parenting or child maltreatment. In this regard, the results from a quasi-experimental evaluation of the Chicago Child-Parent Centers are particularly interesting. This program, which like Head Start provided preschool child care to children from disadvantaged neighborhoods during the two years prior to kindergarten, was found to reduce court petitions related to maltreatment by close to 50% as compared to similar neighborhoods that did not have the program (Reynolds & Robertson, 2003). However, even this study did not measure actual abuse or neglect in the home. In summary, although Head Start (and related programs) has been extensively studied, little research exists on their effects on measures of parenting and child maltreatment (beyond spanking).

Another issue is selection bias, which has been a perennial problem in Head Start research. Head Start by definition serves disadvantaged children who may be at elevated risk of poor outcomes, including low-quality parenting and elevated rates of child maltreatment. Indeed, some children may be referred to Head Start because they have already been exposed to poor home environments or child maltreatment, or because they have been identified as at high risk for such exposure. Analyses that do not take this negative selection account will produce biased estimates. As discussed above, the Head Start Impact Study, the only existing randomized experiment on Head Start, showed evidence that Head Start participation reduced parents’ use of spanking. Nevertheless, it is unknown whether Head Start participation reduces child maltreatment as measured by indicators other than spanking.

In addition, most studies have not clearly defined the reference group to which Head Start children were being compared, even though children not attending Head Start attend a variety of alternative care settings, depending on the localities and time periods (Lee, Brooks-Gunn, & Schnur, 1988; USDHHS, 2005). The Head Start Impact Study compared children assigned to Head Start to all others who were not assigned. We might expect, however, that the effects of Head Start (on parenting and child maltreatment, as well as other outcomes) might vary depending on what the counterfactual is. If, for example, what produces protective effects is the monitoring of children by professionals in child care settings, we might expect particularly strong protective effects for children who otherwise would have remained at home or in informal care, as compared to lesser or null effects for children who otherwise would have attended some other form of formal preschool or pre-kindergarten. Alternatively, if what produces protective effects is parent support and education, then Head Start, with its extensive parental involvement and education programs, might be more protective than other types of preschool or pre-kindergarten programs.

The Present Study

This study investigates the effects of Head Start participation on parenting and child maltreatment in a large and diverse sample of low-income families in large U.S. cities. The analyses use rich data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS), which includes standardized measures of parenting and child abuse and neglect. To address selection bias, we employ several analytic approaches, including logistic regressions with a rich set of pretreatment controls as well as propensity score matching models. We compare the effects of Head Start to any other arrangements as well as specific types of other arrangements.

We address two main research questions in this study. First, does Head Start participation reduce children’s likelihood of receiving low-quality parenting (i.e., low parental warmth, high parental harshness, or low access to learning materials), and their likelihood of experiencing maltreatment (i.e., spanking, other physical assault, neglect, or CPS contact)? Second, how do the effects of Head Start on parenting and child maltreatment vary when we consider specific types of alternative care arrangements separately, including exclusively parental care, pre-kindergarten, other center-based care, and other non-parental care?

Methods

Data and Sample for Analysis

The FFCWS follows a cohort of nearly 5,000 children born to a diverse sample of low-income families in 20 large U.S. cities during 1998–2000 (see Reichman, Teitler, Garfinkel, & McLanahan, 2001, for details). Baseline interviews were conducted in person at the hospitals shortly after the focal child was born, followed by telephone interviews when the focal child was approximately one, three, and five years old. In addition, in-home interviews and direct assessments focused on parenting, discipline, child health, and cognitive and social-emotional development were conducted in a subsample of the FFCWS when children were three and five years old. As described in detail below, the in-home interviews and assessments included the collection of standardized measures of child maltreatment (funded through a special study on child abuse and neglect) as well as parenting.

In this study, we include children who have valid information on child care arrangements right before kindergarten as well as outcome measures on parenting and child maltreatment at age five as collected in the in-home interviews. Our analysis sample includes 2,807 children. In dropping the children with missing data, we are assuming that the data are missing at random. To test this assumption, we compare characteristics for children in the analysis sample and children who were not included. Overall, differences, where found, tended to be modest. As shown in Appendix Table 1, Head Start participants in the analysis sample tended to be more disadvantaged (e.g., more likely to have mothers with lower cognitive ability scores and lower family income) than Head Start participants who were excluded due to missing data; other differences (in terms of demographics and family background) suggested some advantages and some disadvantages. Therefore, it was unclear whether our exclusion of cases with missing data might lead to underestimating or overestimating the effects of Head Start (if those are greater for children who are the most disadvantaged).

Appendix Table 1.

Selected descriptive statistics of children in and out of the analysis sample

| Head Start |

Non-Head Start |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Analysis (n = 386) |

Out of Analysis (n = 71) |

In Analysis (n = 2,421) |

Out of Analysis (n = 1,364) |

|

| Care Arrangement right before K | ||||

| Head Start | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | — | — |

| Parental care | — | — | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.16 (0.37) |

| Pre-kindergarten | — | — | 0.29 (0.45) | 0.32 (0.47) |

| Other center-based care | — | — | 0.43 (0.50) | 0.43 (0.50) |

| Other non-parental care | — | — | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.09 (0.28) |

| Child Characteristics | ||||

| Child male | 0.49 (0.50) | 0.63 (0.49)* | 0.53 (0.50) | 0.52 (0.50) |

| Age at in-home assessment (months) | 64.13 (2.52) | 64.31 0.00 | 64.17 (2.54) | 64.32 (0.68)* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.17 (0.38) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.60 (0.49) | 0.55 (0.50) | 0.47 (0.50) | 0.39 (0.49)** |

| Hispanic | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.22 (0.41) |

| Biracial/other | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.21 (0.41)** |

| Parenting & child maltreatment at age 3 | ||||

| Low parental warmth | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.10 (0.31) | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.13 (0.34) |

| Parental harshness | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.15 (0.37) | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.20 (0.40) |

| Child’s low access to learning | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.12 (0.33) | 0.16 (0.36)+ |

| Spanking | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.27 (0.45) | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.21 (0.41) |

| Other physical assault | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.15 (0.36) |

| Neglect | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.03 (0.16)* | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.09 (0.29) |

| CPS contact | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.11 (0.32)** |

| Mother and Household Characteristics | ||||

| Employment at child’s age 3 | ||||

| Work paid less 35hrs | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.15 (0.36) |

| Work paid 35+ hrs | 0.44 (0.50) | 0.44 (0.50) | 0.45 (0.50) | 0.42 (0.49)+ |

| Look for job | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.28 (0.45) | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.21 (0.41) |

| Not working | 0.15 (0.35) | 0.13 (0.34) | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.23 (0.42)* |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 0.29 (0.45) | 0.27 (0.45) | 0.27 (0.44) | 0.30 (0.46)* |

| HS diploma/GED | 0.38 (0.49) | 0.35 (0.48) | 0.28 (0.45) | 0.29 (0.45) |

| Some college/tech school | 0.29 (0.46) | 0.34 (0.48) | 0.32 (0.47) | 0.27 (0.45)** |

| BA/graduate | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.13 (0.34) | 0.14 (0.34) |

| Mother cognitive ability score | 6.44 (2.29) | 7.29 (1.69)** | 6.88 (2.59) | 6.83 (2.14) |

| Mother depressed in past year | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.21 (0.40) | 0.21 (0.41) |

| Household income at child’s age 3 | ||||

| Below 50% poverty line | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.16 (0.37)* | 0.22 (0.41) | 0.21 (0.41) |

| 50–100% poverty line | 0.27 (0.44) | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.18 (0.38) | 0.18 (0.39) |

| 100–200% poverty line | 0.26 (0.44) | 0.30 (0.46) | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.22 (0.41)* |

| 200–300% poverty line | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.17 (0.38)+ | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.15 (0.35) |

| 300%+ poverty line | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.14 (0.35)* | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.24 (0.43)+ |

Notes: Means with standard deviations in parentheses

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.10 for two-tailed t-statistics testing the mean differences of Head Start children between those in the analysis sample (n = 386) and those out of the analysis sample (n = 71) as well as the mean differences of non-Head Start children between those in the analyses (n = 2,421) and those out of the analyses (n = 1,364).

Children in our analysis sample, overall, tended to be mostly from low-income, unmarried families and racially/ethnically diverse groups. As shown in Table 1 below, 36% of children were born to families with incomes below the poverty line. Nearly half (49%) were non-Hispanic Black children, followed by Hispanics (20%), non-Hispanic Whites (17%), and children of biracial or other racial/ethnic groups (14%). In addition, 56% of children had mothers with high school or less education and 49% had mothers who were not married or cohabiting when the children were three years old.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by Head Start participation and matching status

| Full Sample (n = 2,807) |

Non-HS Before Matching (n = 2,421) |

Head Start (n = 386) |

Non-HS After Matching (n = 382) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care Arrangement right before K | ||||

| Head Start | 0.14 (0.34) | — | 1.00 (0.00) | — |

| Exclusively parental care | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.19 (0.39) | — | 0.19 (0.40) |

| Pre-kindergarten | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.29 (0.45) | — | 0.28 (0.45) |

| Other center-based care | 0.37 (0.48) | 0.43 (0.50) | — | 0.42 (0.49) |

| Other non-parental care | 0.08 (0.27) | 0.09 (0.29) | — | 0.11 (0.31) |

| Child Characteristics | ||||

| Child male | 0.53 (0.50) | 0.53 (0.50)+ | 0.49 (0.50) | 0.52 (0.50) |

| Age at in-home assessment (months) | 64.17 (2.54) | 64.17 (2.54) | 64.13 (2.52) | 64.21 (2.51) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.18 (0.39)** | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.07 (0.25) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.49 (0.50) | 0.47 (0.50)** | 0.60 (0.49) | 0.59 (0.49) |

| Hispanic | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.21 (0.40) |

| Biracial/other | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.15 (0.36)+ | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.13 (0.35) |

| Low birth-weight | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.11 (0.32) |

| Mother’s first child | 0.39 (0.49) | 0.40 (0.49)** | 0.32 (0.47) | 0.34 (0.47) |

| Mother reported fair/poor health | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.03 (0.17) |

| Parenting and child maltreatment at age 3 | ||||

| Low parental warmth | 0.12 (0.32) | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.16 (0.37) |

| Parental harshness | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.17 (0.38)* | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.24 (0.43) |

| Child’s low access to learning | 0.14 (0.34) | 0.12 (0.33)** | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.21 (0.41) |

| Spanking | 0.24 (0.42) | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.23 (0.43) |

| Other physical assault | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.16 (0.36) |

| Neglect | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.10 (0.30)* | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.13 (0.34) |

| CPS contact | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.20) |

| Mother & Household Characteristics | ||||

| Age | 28.13 (5.92) | 28.30 (5.97)** | 27.02 (5.46) | 26.94 (5.28) |

| Born in the U.S. | 0.88 (0.33) | 0.87 (0.34)** | 0.92 (0.28) | 0.91 (0.28) |

| Lived with both parents at age 15 | 0.41 (0.49) | 0.43 (0.49)** | 0.33 (0.47) | 0.32 (0.47) |

| First child born under age 19 | 0.32 (0.46) | 0.30 (0.46)** | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.41 (0.49) |

| Alcohol, cigarette, drugs at pregnancy | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.26 (0.44) | 0.28 (0.46) |

| Parental stress score at child age 3 | 13.05 (7.41) | 12.94 (7.45)* | 13.74 (7.12) | 13.33 (7.09) |

| Depressed in past year | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.21 (0.40) | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.22 (0.40) |

| Cognitive ability score | 6.82 (2.55) | 6.88 (2.59)** | 6.44 (2.29) | 6.64 (2.40) |

| Relationship with father at child age 3 | ||||

| Married | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.32 (0.47)** | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.18 (0.39) |

| Cohabitating | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.24 (0.43) |

| Friends/visiting | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.23 (0.42)** | 0.30 (0.46) | 0.28 (0.45) |

| Other | 0.25 (0.44) | 0.24 (0.43)** | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.30 (0.46) |

| Employment at child’s age 3 | ||||

| Work paid less 35hrs | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.17 (0.37) |

| Work paid 35+ hrs | 0.45 (0.50) | 0.45 (0.50) | 0.44 (0.50) | 0.47 (0.50) |

| Look for job | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.20 (0.40)+ | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.23 (0.42) |

| Not working | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.19 (0.39)+ | 0.15 (0.35) | 0.13 (0.34) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 0.27 (0.44) | 0.27 (0.44) | 0.29 (0.45) | 0.31 (0.46) |

| HS diploma/GED | 0.29 (0.46) | 0.28 (0.45)** | 0.38 (0.49) | 0.37 (0.48) |

| Some college/tech school | 0.32 (0.46) | 0.32 (0.47) | 0.29 (0.46) | 0.28 (0.45) |

| BA/graduate | 0.12 (0.33) | 0.13 (0.34)** | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.05 (0.21) |

| Number of other adults in household | 1.25 (0.67) | 1.25 (0.66) | 1.28 (0.74) | 1.24 (0.64) |

| Household income at child’s birth | ||||

| Below 50% poverty line | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.18 (0.38)** | 0.27 (0.44) | 0.25 (0.44) |

| 50–100% poverty line | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.16 (0.37)* | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.24 (0.43) |

| 100–200% poverty line | 0.25 (0.44) | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.26 (0.44) | 0.26 (0.44) |

| 200–300% poverty line | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.16 (0.37) |

| 300%+ poverty line | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.26 (0.44)** | 0.10 (0.29) | 0.08 (0.27) |

| Household income at child’s age 3 | ||||

| Below 50% poverty line | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.22 (0.41)** | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.30 (0.44) |

| 50–100% poverty line | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.18 (0.38)** | 0.27 (0.44) | 0.29 (0.45) |

| 100–200% poverty line | 0.25 (0.44) | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.26 (0.44) | 0.27 (0.46) |

| 200–300% poverty line | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.14 (0.35)* | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.11 (0.32) |

| 300%+ poverty line | 0.19 (0.39) | 0.21 (0.41)** | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.03 (0.19) |

Notes: Means with standard deviations in parentheses

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.10 for two-tailed t-statistics testing mean differences between Head Start participants and non-participants before and after propensity score matching (with significance levels, if applicable, indicated in the descriptive statistics for non-participants), respectively.

Measures

Head Start and other care arrangements

In the five-year follow-up interviews (when children on average were about five years old), parents were asked about the focal child’s care arrangements right before kindergarten (i.e., kindergarten was not counted as a child care arrangement). Based on these data, we define five mutually exclusive categories of care arrangements right before kindergarten: exclusively parental care; Head Start; pre-kindergarten; other center-based care; or other non-parental care. Children are coded as receiving exclusively parental care if they did not attend center-based care regularly and were not cared by someone other than the custodial parents for at least eight hours every week for a month or more. Among children who attended center-based care regularly, we use the most regularly attended program to identify the child’s main center-based care arrangement and, following prior research (Magnuson, Ruhm, & Waldfogel, 2007), categorize these as either Head Start, pre-kindergarten, or other center-based care (e.g., day care centers, nursery schools, and preschool programs). The rest of children in the sample – those who did not attend child care centers regularly but received care from someone other than the custodial parents for at least eight hours every week for a month or more – are coded as receiving other non-parental care.

As detailed below, in the analysis we first focus on estimating the effects of Head Start participation on parenting and child maltreatment compared to any other care arrangements (i.e., Head Start versus all non-Head Start). Following these analyses, we compare the effects of Head Start to the other specific types of care arrangements (i.e. exclusively parental care, pre-kindergarten, other center-based care, and other non-parental care).

Outcome variables of parenting and child maltreatment

The data on all the outcome measures in our study were collected in the five-year in-home interviews. We analyze a total of seven outcome variables, drawing both on observer-reported data on mothers’ parenting skills and home environment (i.e., parental warmth, parental harshness, and child access to learning) and mother-reported data on child discipline and maltreatment (i.e., spanking, other physical assault, neglect, and CPS contact).

Specifically, the data on parenting were reported by observers during home visits using the subscales of the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME), which has been widely used to measure the quality of parenting and the home environment (Bradley, 1993). Based on previous research (e.g., Berger, Brooks-Gunn, Paxson, & Waldfogel, 2008; Bradley & Corwyn, 2007; Fuligni, Han, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004; Leventhal, Martin, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004), we use three aggregated HOME subscales, including parental warmth, parental harshness, and child’s access to learning. The parental warmth subscale includes eight items that measure mothers’ attitudes and responsiveness toward their children during observers’ home visits (α = 0.80). Those items asked whether the mother talked at least twice to the child, verbally answered the child’s questions, encouraged the child to contribute to conversation, helped the child demonstrate some achievement, spontaneously praised the child’s behavior, used some terms of endearment, conveyed positive feelings when speaking of the child, or kissed or cuddled the child at least once. The parental harshness subscale includes four items indicating whether the mother shouted at the child, expressed hostility toward the child, slapped or spanked the child, or scolded the child more than once (α = 0.72). The subscale of child access to learning consists of 11 items that measure the cognitively stimulating materials available to children in the home (α = 0.70), such as puzzles, books/games (i.e., separate items on colors, sizes, shapes, animal names/behaviors, numbers, spatial relationships, songs, and alphabet), and musical instruments.

Child maltreatment is assessed using four measures which collect data on child discipline and CPS contact, as reported by mothers during the five-year in-home interviews. Three of the measures are derived from the Parent-Child Conflict Tactic Scales (PC-CTS), the most widely used measure of child maltreatment and one which captures the degree of punitiveness and abusive risk exhibited by parents in their behavior to their children (Straus et al., 1998). We use three PC-CTS subscales to measure three specific types of child discipline and maltreatment: spanking; other physical assault; and neglect. The spanking measure is from the question asking the mother how many times in the past year she spanked the child on the bottom with her bare hand. The measure of other physical assault consists of four questions asking the mother how many times in the past year she shook the child, hit the child on the bottom with hard object, slapped, or pinched the child (α = 0.62). In general, other physical assaults tend to be more severe and less common than spanking. Another PC-CTS subscale is neglect, including five items measuring how many times in the past year that the mother left the child home alone, was not able to show love to the child or to make sure the child got food or a doctor needed, or had a problem taking care of the child (α = 0.60). Our final child maltreatment measure is CPS contact, based on mothers’ report of whether CPS ever contacted her about children in the household.

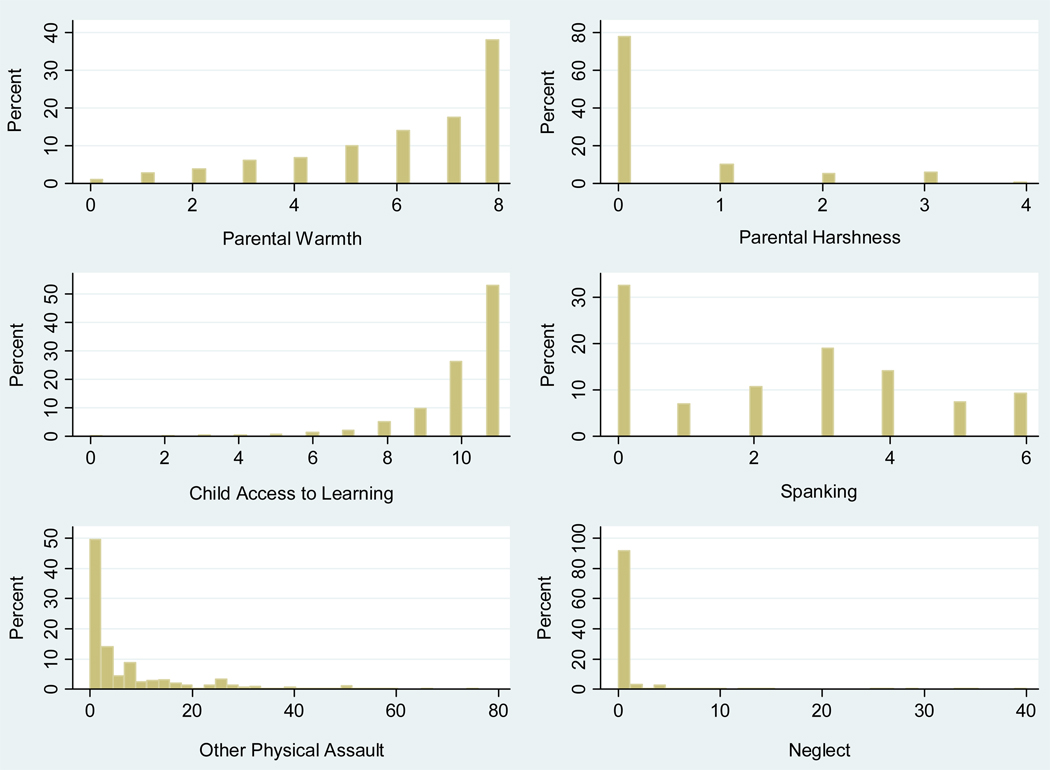

As shown in Appendix Figure 1, these outcome measures tend to be highly skewed in our data. In our main analyses, we recode them into binary variables to indicate whether there is potential or existing risk of inadequate parenting or child maltreatment. Specifically, the majority of mothers did not show any of the harmful behaviors related to parental harshness (78%) or neglect (89%). Therefore, we dichotomize these measures to differentiate mothers who reported any harmful behaviors versus those who did not. For the measures of parental warmth and child access to learning, most mothers reported nearly all the listed favorable behaviors or items (i.e., 70% with six or more out of a total of eight behaviors for parental warmth and 80% with 10 or 11 out of a total of 11 items for access to learning). We categorize children’s scores lower than one standard deviation below the mean as low parental warmth and low access to learning. For spanking and other physical assault, most mothers reported few harmful behaviors in the past year (i.e., 69% with less than five times of spanking and 79% with less than 10 out of 76 or more times of other physical assaults). We define children’s scores higher than one standard deviation above the mean as high spanking and high physical assault. For CPS contact, we use a binary variable to indicate any CPS contact between the time children were ages three and five.

Appendix Figure 1.

Relative frequency distribution of original outcome measures

As a robustness check, we also recode the outcome measures in various alternative ways, followed by appropriate analyses. For the six outcomes that could possibly have continuous values (i.e., all but the CPS contact variable), we also conduct log-transformation for these variables, use one-third standard deviations as the cut-off points to dichotomize the measures, and adopt one-third standard deviations to group these variables into three categories (i.e., low, moderate, and high risk). These supplementary analyses, not shown but available on request, indicate that the findings show similar patterns to those reported below and are not sensitive to different coding of the outcome measures.

Control variables

We estimate a set of multivariate regression models (detailed below) that take advantage of rich data on an extensive set of covariates that might affect children’s probabilities of Head Start participation as well as parenting and child maltreatment. Data on these covariates come from the baseline, year one, and year three interviews and assessments.

Our controls for child demographics include gender, age at assessment, and race/ethnicity; and whether or not the child was the mother’s first child, had a low birth weight, or had fair or poor health status reported by mother. Mother’s demographics include age; whether she was born in the U.S.; whether she lived with both parents at age 15; whether her first child was born when she was 18 years old or younger; whether she used any alcohol, cigarette, or drugs during pregnancy; relationship status with child’s father (i.e., married, cohabitating, friends or visiting, or other) in the three-year survey; employment at the time of the three-year survey; and education. Additional mother controls include the mother’s report of parental stress and depressive symptoms collected in the three-year interview, since this is likely to be associated with parenting and child maltreatment. Family controls include the number of other adults in the household and household income relative to poverty threshold at the time of child’s birth and age three.

In addition, to control for parenting and child maltreatment prior to children’s enrollment in Head Start, in supplemental analyses we include the corresponding measures of parenting or child maltreatment from the three-year interview (when children were approximately three years old) in our models for parenting and child maltreatment from the five-year interview (when children were approximately five years old). The outcome measures from the three-year interview serve as pretreatment measures because very few children in our sample (i.e., 1.7%, or 48 children) were in Head Start programs then.

Analytic Strategies

As discussed above, selection bias has been a perennial challenge in research on Head Start, due to the fact that the program serves the most disadvantaged children. Even with a rich set of control variables, such as we have here, it is impossible to rule out the possibility that children may be selected into Head Start due to factors for which we cannot control and which may be associated with the outcomes of interest.

To address this potential selection bias, we apply several analytic approaches, including logistic regressions with a rich set of controls as well as propensity score matching models. Model 1 estimates the effect of Head Start participation status (1 = yes; 0 = no) prior to kindergarten on parenting and child maltreatment at age five, controlling only for city-fixed effects to account for the heterogeneity across cities in Head Start programs, the availability and usage of other types of child care arrangements, and other contextual factors that could affect children’s participation in Head Start as well as parenting and child maltreatment. It is important to take these factors into account because preliminary results (not shown, but available on request) suggested that the estimates of the effects of Head Start were confounded by city differences in the sample. Model 2 adds controls for child demographics as well as mother and family covariates.

To further address the issue of potential selection bias, we estimate Model 3 using a propensity score matching method. As shown in Table 1 and discussed in detail below, Head Start participants tended to be significantly different from non-participants in many of the demographics and family covariates. With the distribution or support of these covariates overlapping relatively little, the estimates of the effects of Head Start can be highly sensitive to functional form (Foster, 2003). To address this issue, we employ a propensity score matching method to identify children who did not attend Head Start but were comparable to Head Start participants in terms of their demographics and family background at age three.

It should be noted that a propensity score matching approach, like regression, assumes ignorability or selection on observables. In other words, it relies on the assumption that all confounding covariates related to treatment status are observed (Dehejia & Wahba, 1999, 2002; Foster, 2003; Gibson, 2003; Guo & Fraser, 2009; Hill, Brooks-Gunn, & Waldfogel, 2003; Hill et al., 2005; Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1985). Assuming the predictive covariates are the only confounding variables, the matched children with similar propensity scores can be conceptualized as treatment and control groups, similar to being randomly assigned to the treatment or control groups in an experiment. To gauge how sensitive the findings are to hidden bias, we conduct a Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis, which uses the Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test for matched pair studies (Guo & Fraser, 2009; Rosenbaum, 2005). Results suggest that the findings reported below are robust against hidden bias (i.e., Γ ≥ 4 in the overall and subsample analyses).

Specifically, the propensity score matching method includes three stages. In the first stage, we use the child, mother, and family covariates that were collected when the focal child was three years old to predict the probability of attending Head Start right before kindergarten (i.e., the propensity score) for each child. In the second stage, each Head Start participant is matched with a child who did not attend Head Start but lived in the same city and had the closest propensity score, using a one-to-one nearest neighbor matching method with replacement. Matching with replacement allows each treatment unit to be matched with the nearest control unit (i.e., some control units could be used more than once) and thus minimizes bias (Dehejia & Wahba, 1999, 2002; Gibson, 2003). In the matching procedure, a “common support” option is also adopted to limit Head Start participants to those whose propensity scores were not higher than the maximum or less than the minimum propensity scores of non-participants, which can further reduce bias as compared to standard regression models (Leuven & Sianesi, 2003); in our sample, this resulted in four cases not being matched. We conduct a balance test of the covariates before and after matching and report the results in detail below.

In the third stage, the effects of Head Start are estimated by the regression-adjusted differences in children’s outcomes between Head Start participants and non-participants in the matched sample, including the covariates in previous models. Regression adjustment after matching takes into account the effects of covariates on outcomes rather than attributing children’s differences in outcomes only to their participation of Head Start (Abadie & Imbens, 2002, 2006). As a result, it can further reduce potential bias and also improve robustness to misspecification of the models since it only adjusts for relatively small differences in the covariates (Abadie & Imbens, 2002, 2006; Gibson, 2003; Hill et al., 2003; USDHHS, 2005).

The above propensity score matching approach adopts a one-to-one nearest neighbor matching method, which results in a substantial reduction in the size of analysis samples and thus may be of concern. To test the robustness of the findings, we employ an inverse probability weighting approach in the full sample. This approach aims to reweight participants in the treatment and control groups to make them representative of the population of interest and can lead to an efficient estimate of the average treatment effect (Guo & Fraser, 2009; Hirano, Imbens, & Ridder, 2003). However, inverse probability weighting may also increase biases (Freedman & Berk, 2008; Guo & Fraser, 2009; Kang & Schafer, 2007). Based on the propensity scores (i.e., P) estimated in the first stage above, the weights are (1/P) for participants in the treatment group and [1/(1 - P)] for those in the control group. The weights are then used in the multivariate analysis in the full sample.

In the analyses we first examine the effects of Head Start compared to all other non-Head Start care arrangements (i.e., Head Start versus all non-Head Start), using the models specified above. As discussed above, there are strong reasons to expect the effects of Head Start to vary depending on what the counterfactual arrangement is. Therefore, to better understand the effects of Head Start, we also apply the above analytic models separately to sub-samples consisting of children who had attended Head Start and one of the specific other types of care arrangements, including exclusively parental care, pre-kindergarten, other center-based care, and other non-parental care. As mentioned earlier, as a robustness test, we then conduct supplementary analyses using different coding strategies of the outcome measures, including log-transformation, binary outcomes using one-third standard deviations as the cut-off points, and three-categorical outcomes using one-third standard deviations (i.e., low risk, moderate, and high risk).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Results of Propensity Score Matching

In Table 1 we show the descriptive statistics of child care arrangements and pretreatment covariates by children’s Head Start participation and matching status. The first column shows statistics for the full analysis sample (N = 2,807), followed by statistics for non-Head Start children before propensity score matching (N = 2,421), Head Start participants (N = 386), and non-Head Start children after propensity score matching (N = 382) (as mentioned earlier, four Head Start participants were not in the common support area and thus were not matched to non-participants). Two-tailed t-statistics are used to test differences in means between Head Start participants and non-participants, before and after propensity score matching (with significance levels, if applicable, indicated with asterisks in the column for the non-participants).

As shown in Table 1 (Column 1), overall 14% of children in the full analysis sample attended Head Start programs right before kindergarten; other children received exclusively parental care (16%), pre-kindergarten (25%), other center-based care (37%), or other non-parental care (8%). Among children in the full sample who did not attend Head Start programs (Column 2), 43% were enrolled in other child care centers, 29% attended pre-kindergarten programs, 9% received other non-parental care, and 19% had exclusively parental care.

The t-statistic results in Table 1 show that Head Start participants and non-participants are significantly different on most pretreatment covariates before propensity score matching (Column 2) and are very similar after matching (Column 4). Notably, Head Start participants are significantly more disadvantaged than non-participants in the full sample. For example, compared to non-participants, Head Start participants are more likely to be non-Hispanic Black and less likely to be non-Hispanic White, more likely to have foreign-born mothers, teen mothers, unmarried mothers, and mothers with higher parental stress scores and lower cognitive ability scores and education, and more likely to live in poverty at birth and at age three. Head Start participants also experience significantly more parental harshness and neglect, and less access to learning materials at age three compared to non-participants in the full sample.

In contrast, after propensity score matching, Head Start participants and non-participants are very closely similar; indeed, the t-statistic results do not show any significant differences between them. Therefore, the propensity score matching approach adopted in this study successfully identifies a comparable control group for Head Start participants and should substantially reduce the selection bias associated with the observed covariates included in the models, although it will not affect bias related to unobserved covariates, as detailed above.

Effects of Head Start Compared to Any Other Care Arrangements

To estimate the average effects of Head Start on parenting and child maltreatment, we first compare Head Start to any other care arrangements (i.e., Head Start vs. non-Head Start). The results are presented in Table 2. Model 1 is a logistic regression that controls only for city-fixed effects to take into account the contextual heterogeneity across cities. Child demographics at birth and age three as well as mother and family background covariates are added in Model 2. Model 3 employs a propensity score matching method, as detailed above, to further address the issue of selection bias. In all analyses, the outcome variables are dichotomized with a value of 1 or 0, using the methods described above. The table shows the odds ratios from logistic regressions with z-statistics (clustered at city level) in parentheses. Odds ratios greater than one indicate that a factor is associated with higher likelihood of inadequate parenting or maltreatment; odds ratios less than one indicate that a factor is associated with a lower likelihood of such outcomes.

Table 2.

Effects of Head Start compared to any other care arrangements

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting | |||

| Low parental warmth | 1.55** (3.76) |

1.24+ (1.78) |

0.93 (−0.27) |

| Parental harshness | 1.67** (3.56) |

1.43* (2.06) |

1.28 (1.10) |

| Child’s low access to learning | 0.93 (−0.48) |

0.70** (−2.72) |

0.40** (−3.31) |

| Child Maltreatment | |||

| Spanking | 1.20 (1.06) |

1.13 (1.00) |

0.71** (−2.75) |

| Other physical assault | 1.42* (2.10) |

1.20 (1.04) |

0.89 (−0.59) |

| Neglect | 1.53** (4.98) |

1.29* (2.56) |

0.86 (−0.83) |

| CPS contact | 1.23 (0.80) |

1.11 (0.43) |

0.66 (−1.40) |

Notes: The outcome variables were dichotomized with a value of “1” or “0.” The “low” category (i.e., with a value of “1”) of parental warmth and child’s access to learning was defined as scores lower than one standard deviation below the mean; for physical assault, the “yes” category (i.e., with a value of “1”) referred to scores higher than one standard deviation above the mean; and parental harshness, neglect, spanking, and CPS contact were coded as “1” if parents conducted any activities on items included in the measures. Model 1 included city fixed effects; child demographics and mother and family covariates were added in Model 2; Model 3 used propensity score matching. The sample sizes were 2,807 for Models 1 and 2, and 764 for Model 3. Odd ratios with z-statistics (clustered at city level) in parentheses

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.10

As shown in Table 2, the results change substantially moving from Models 1 to 3, as selection bias is taken into account by adding more covariates (Models 1–2) and by using propensity score matching (Model 3). Results from Model 1, which controls for only city-fixed effects, suggest that children who attended Head Start receive significantly worse parenting in terms of low parental warmth and harshness and are also significantly more likely to be physically assaulted or neglected (differences on the other three outcome variables are not significant). As discussed above, however, these results may to at least some extent reflect selection bias in the probability of Head Start participation. In Model 2, with the full set of controls, children who attended Head Start differ from other children on only three of the seven outcome variables – they are significantly more likely to receive harsh parenting and to be neglected, but also significantly less likely to have low access to learning. Supplemental analyses (not shown but available on request) controlling for the relevant pretreatment parenting or child maltreatment outcome for each respective outcome variable show similar results to those from Model 2.

However, even fully controlled models may not adequately control for selection bias. Thus, in Model 3, we estimate propensity score matching models limiting the analyses to children who attended Head Start and the non-Head Start children who are most like them (in terms of observed covariates). This specification removes further bias and now results in Head Start children not receiving significantly worse parenting or more maltreatment; indeed, the two significant effects in this model point to Head Start children receiving better parenting (i.e. less likely to experience low access to learning) and less maltreatment (less likely to be spanked). The odds ratio for low access to learning is 0.40 (with a z-statistic of −3.31 and p < 0.01), which indicates that Head Start participants are 60% less likely to have low access to learning than non-participants. The odds ratio for spanking is 0.71 (with a z-statistic of −2.75 and p < 0.01), suggesting their chance of being spanked is 29% less than that for non-participants.

Effects of Head Start Compared to Specific Types of Care Arrangements

Table 3 shows the results of models comparing Head Start to other specific types of care arrangements. The analyses are based on the propensity score matching models (i.e., Model 3) in Table 2 and are conducted separately in sub-samples consisting of Head Start participants and non-participants who received one of the other specific types of care arrangements, including exclusively parental care, pre-kindergarten, other center-based care, and other non-parental care. The odds ratios and z-statistics from logistic regressions are presented in the table.

Table 3.

Effects of Head Start compared to other specific types of care arrangements

| Head Start vs. Parental |

Head Start vs. Pre-kindergarten |

Head Start vs. Other center-based |

Head Start vs. Other non-parental |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting | ||||

| Low parental warmth | 0.44* (−2.23) |

0.79 (−0.81) |

0.82 (−0.56) |

0.61 (−0.76) |

| Parental harshness | 0.58 (−1.55) |

1.41 (1.36) |

1.04 (0.15) |

0.81 (−0.38) |

| Child’s low access to learning | 0.46* (−2.17) |

0.39** (−3.20) |

0.35** (−2.93) |

0.27* (−2.38) |

| Child Maltreatment | ||||

| Spanking | 0.54* (−2.18) |

0.93 (−0.42) |

0.62* (−2.25) |

0.58+ (−1.66) |

| Other physical assault | 0.55+ (−1.67) |

1.06 (0.14) |

1.06 (0.20) |

0.79 (−0.58) |

| Neglect | 1.03 (0.07) |

1.19 (0.58) |

0.45** (−3.97) |

0.30* (−2.11) |

| CPS contact | 0.55* (−2.01) |

0.75 (−0.66) |

0.88 (−0.22) |

1.22 (0.36) |

Notes: The results were from propensity score matching analyses (i.e., Model 5 in Table 2), which were conducted separately in sub-samples consisting of Head Start participants and children who received one of other specific care arrangements. The sample sizes were 622 for Head Start vs. exclusively parental care, 700 for Head Start vs. pre-kindergarten, 724 for Head Start vs. other center-based care, and 656 for Head Start vs. other non-parental care. Odd ratios with z-statistics (clustered at city level) in parentheses

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.10

As shown in Table 3, the effects of Head Start on parenting and child maltreatment differ depending on both the reference group and the outcome measure. The strongest pattern of benefits to Head Start is evident for children who otherwise would have remained home with parents. Specifically, when compared to children who received exclusively parental care right before kindergarten, Head Start participants are less likely to experience low parental warmth or low access to learning materials and less likely to experience spanking or CPS contact in the past year (they are also less likely to experience other physical assault, but this effect is only marginally significant at p < 0.10). In contrast, when Head Start children are compared to children who attended pre-kindergarten programs, the only significant difference is that Head Start participants are less likely to experience low access to learning. Models comparing Head Start children to children who attended other child care centers or children who received other non-parental care point to yet another pattern of results, with Head Start participants less likely to have low access to learning materials and less likely to experience spanking or neglect (although the spanking effect is only marginally significant in the other non-parental care model).

Thus, it appears that the benefits of Head Start depend to a large extent on the counterfactual to which it is compared. However, it is also notable that, in terms of outcome measures, Head Start participation is consistently associated with a lower likelihood of low access to learning materials, suggesting that this is an area where Head Start confers advantages regardless of the counterfactual.

Results from Inverse Probability Weighting

Appendix Table 2 presents the results from the inverse probability weighting analyses in the full sample. Many of the findings are consistent with those reported in Table 2 and Table 3 from the propensity score matching approach. In particular, the statistically significant findings on low access to learning and spanking are similar in propensity score matching and inverse probability weighting approaches in both overall and subgroup comparisons, although the odds ratios from propensity score matching are slightly smaller (i.e., indicating larger effects of Head Start). Some findings from the subgroup analyses that are significant using propensity score matching are not statistically significant in the inverse probability weighting analyses (e.g., low parental warmth, other physical assault, CPS contact when compared to exclusively parental care; neglect when compared to other centers and other non-parental care) or show disadvantages of Head Start (i.e., neglect when compared to pre-k). However, as discussed earlier, caution has been suggested in using inverse probability weighting due to the possible biases that it may increase (Freedman & Berk, 2008; Guo & Fraser, 2009; Kang & Schafer, 2007).

Appendix 2.

Effects of Head Start using inverse probability weighting

| Head Start vs. Non-HS |

Head Start vs. Parental |

Head Start vs. Pre-kindergarten |

Head Start vs. Other center-based |

Head Start vs. Other non-parental |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting | |||||

| Low parental warmth | 1.03 (0.22) |

0.94 (−0.20) |

1.02 (0.09) |

1.07 (0.35) |

0.96 (−0.13) |

| Parental harshness | 1.35 (1.60) |

0.96 (−0.19) |

1.32 (1.42) |

1.31 (1.40) |

1.25 (0.61) |

| Low access to learning | 0.49** (−4.34) |

0.53** (−2.82) |

0.40** (−3.50) |

0.48** (−4.26) |

0.46* (−2.49) |

| Child Maltreatment | |||||

| Spanking | 0.74** (−2.69) |

0.73+ (−1.73) |

1.28 (1.15) |

0.69** (−2.95) |

0.69* (−2.40) |

| Other physical assault | 1.16 (0.82) |

1.28 (0.95) |

1.07 (0.25) |

1.24 (1.00) |

0.86 (−0.43) |

| Neglect | 1.38 (1.64) |

1.53 (1.52) |

1.62* (1.96) |

1.06 (0.26) |

1.19 (0.51) |

| CPS contact | 1.05 (0.18) |

0.65 (−1.42) |

1.03 (0.08) |

1.22 (0.65) |

1.35 (0.51) |

Notes: The results were from inverse probability weighting analyses in the full sample (n = 2,807); odd ratios with z-statistics (clustered at city level) in parentheses

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.10

Discussions and Conclusions

We examine the effects of Head Start participation on parenting and child maltreatment, using data from a large and diverse sample of low-income families in large U.S. cities and a propensity score matching method to address the issue of selection bias. Overall, we find that compared to children who did not attend Head Start right before kindergarten, children who did attend Head Start are less likely to have low access to learning materials and less likely to experience spanking by their parents at age five. Furthermore, we find that the effects of Head Start vary depending on the specific type of other child care arrangements to which they are compared, with the most consistently beneficial protective effects seen when Head Start is compared to being home in exclusively parental care.

Our study does have some limitations. First, as in any observational study, we are not able to establish causality with certainty. To address the issue of selection bias, we include a rich set of control variables in the models and in addition use a propensity score matching method. As discussed above, both methods are subject to the assumption of strong ignorability or selection on observables. Even in the propensity score matching models, the estimates of Head Start effects could be biased if any important covariates unrelated to the covariates already included in the models were omitted. The results from a Rosenbaum’s sensitivity analysis (Guo & Fraser, 2009; Rosenbaum, 2005) suggest that our findings are robust again hidden bias. Estimates using an alternative method, inverse probability weighting, for the most part confirmed the results, but with some slight differences, although these may reflect biases produced by that method. Second, as is frequently the case in such studies, the information about Head Start and other child care arrangements is reported by parents and may be inaccurate. Analyses of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort, which compared data from parent reports to program records, indicate that 29% of children who were reported by their parents to have attended Head Start programs did not actually attend (Tourangeau et al., 2001). If Head Start participation is over-reported in our sample as well, this measurement error would lead to the estimated effects of Head Start being attenuated (Garces, Thomas, & Currie, 2002; Ludwig & Phillips, 2007).

Despite these limitations, this study moves beyond previous research in three important respects. First, we provide the first empirical evidence as to the effects of Head Start on not just parenting and spanking but a broader set of measures of maltreatment. Estimating the effects of Head Start on maltreatment is rare, because data on abuse and neglect are rarely collected from population samples. Here we take advantage of specially collected data on maltreatment from the FFCWS and are able to show that Head Start is associated not just with improvements in parenting and reductions in spanking, but with some reductions in broader measures of maltreatment as well. Compared to children who remained home in exclusively parental care, Head Start is associated with reduced CPS contact and reduced physical assault (although this latter finding is only marginally significant), and compared to children who attended other center based care or other non-parental care, Head Start is associated with reduced neglect. Second, although we lack experimental data, we apply rigorous methods for causal inference in observational data, including regression models with increasingly rich controls as well as propensity score matching models. It is evident from the results that estimates that did not apply such methods would have been severely biased, leading to the false conclusion that Head Start was associated with greater risk of abuse and neglect as well as inadequate parenting. Third, we estimate not just overall effects of Head Start but also effects of Head Start relative to other alternative forms of child care. These latter analyses suggest that the most consistently positive set of effects are found when children who attended Head Start are compared to children who remained in exclusively parental care. This finding has important implications for policy, as it suggests the value of outreach, referral, and intake policies aimed at boosting Head Start enrollment among children who otherwise would remain home in parental care.

Taken together, our findings add to the growing evidence base about programs that might effectively improve parenting and prevent maltreatment among young children. In future research, it would be useful to compare the effects we find here with those found in studies of other types of prevention programs. In particular, the role of home visiting programs in improving parenting and preventing maltreatment for younger children has been extensively studied, and we now know a good deal about the effects of such programs (see review by Howard & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). Understanding how, and why, effects vary by program type, child age, and outcome, would be a very fruitful direction for future research.

Acknowledgments

Note: We gratefully acknowledge funding support from NICHD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Fuhua Zhai, School of Social Welfare, Stony Brook University, L2-093 Health Sciences Center, Stony Brook, NY 11794, Phone: 631-444-3176, fuhua.zhai@stonybrook.edu.

Jane Waldfogel, School of Social Work, Columbia University, 1255 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027, Phone: 212-851-2408, jw205@columbia.edu.

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, Teachers College and the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, Phone: 212-678-3369, brooks-gunn@columbia.edu.

References

- Abadie A, Imbens G. Simple and bias-corrected matching estimators for average treatment effects. NBER Technical Working Papers #0283. 2002:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Abadie A, Imbens G. Large sample properties of matching estimators for average treatment effects. Econometrica. 2006;74:235–267. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The social context of child maltreatment. Family Relations. 1994;43:360–368. [Google Scholar]

- Berger L, Brooks-Gunn J, Paxson C, Waldfogel J. First-year maternal employment and child outcomes: Differences across racial and ethic groups. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:365–387. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger L, Waldfogel J. Economic determinants and consequences of child maltreatment. University of Wisconsin and Columbia University, working paper. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Bogat GA, DeJonghe E, Levendosky AA, Davidson WS, von Eye A. Trauma symptoms among infants exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:109–125. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH. Children’s home environments, health, behavior, and intervention efforts: A review using the HOME inventory as a marker measure. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs. 1993;119:439–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Externalizing problems in fifth grade: Relations with productive activity, maternal sensitivity, and harsh parenting from infancy through middle childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1390–1401. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Dunne MP, Han P. Child sexual abuse in China: A study of adolescents in four provinces. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:1171–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Causal effects in nonexperimental studies: Reevaluating the evaluation of training programs. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:1053–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia R, Wahba S. Propensity score matching methods for non-experimental causal studies. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2002;84:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Korbin J. Child abuse as an international issue. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1988;12:3–23. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(88)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster EM. Propensity score matching: An illustrative analysis of dose response. Medical Care. 2003;41:1183–1192. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000089629.62884.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DA, Berk RA. Weighting regressions by propensity scores. Evaluation Review. 2008;32:392–409. doi: 10.1177/0193841X08317586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AS, Han WJ, Brooks-Gunn J. The infant-toddler Home in the second and third years of life. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Garces E, Thomas D, Currie J. Long-term effects of Head Start. The American Economic Review. 2002;92:999–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CM. Privileging the participants: The importance of sub-group analysis in social welfare evaluations. American Journal of Evaluation. 2003;24:443–469. [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Fraser MW. Propensity score analysis: Statistical methods and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Guterman NB. The emerging problems of physical child abuse in South Korea. Child Maltreatment. 2001;6:169–179. doi: 10.1177/1077559501006002009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Waldfogel J. Sustained effects of high participation in an early intervention for low-birth-weight premature infants. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:730–744. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LJ, Waldfogel J, Brooks-Gunn J, Han W. Maternal employment and child development: A fresh look using newer methods. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:833–850. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K, Imbens GW, Ridder G. Efficient estimation of average treatment effects using the estimated propensity score. Econometrica. 2003;71:1161–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Howard KS, Brooks-Gunn J. The role of home visiting programs in preventing child abuse and neglect. Future of Children. 2009;19:119–146. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JDY, Schafer JL. Demystifying double robustness: A comparison of alternative strategies for estimating a population mean from incomplete data. Statistical Science. 2007;22:523–539. doi: 10.1214/07-STS227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VE, Brooks-Gunn J, Schnur E. Does Head Start work? A 1-year follow-up comparison of disadvantaged children attending Head Start, no preschool, and other preschool programs. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:210–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. 2003 Retrieved online on Sept. 10, 2010 from http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html.

- Leventhal T, Martin A, Brooks-Gunn J. The EC-HOME across five national datasets in the third to fifth year of life. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Love JM, et al. The effectiveness of Early Head Start for 3-year old children and their parents: Lessons for policy and programs. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:885–901. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J, Miller DL. Does Head Start improve children’s life chances? Evidence from a regression discontinuity design. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2007;122:159–208. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson KA, Waldfogel J. Pre-school enrollment and parents’ use of physical discipline. Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson KA, Ruhm C, Waldfogel J. Does prekindergarten improve school preparation and performance? Economics of Education Review. 2007;26:33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Park MS. The factors of child physical abuse in Korean immigrant families. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:945–958. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS. Fragile Families: Sample and Design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23:303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AJ, Robertson D. School-based early intervention and later child maltreatment in the Chicago Longitudinal Study. Child Development. 2003;74:3–26. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR. Sensitivity analysis in observational studies. In: Everitt BS, Howell DC, editors. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2005. pp. 1809–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Journal of the American Statistician. 1985;39:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JR, Brooks-Gunn J. Correlates and consequences of mothers’ harsh discipline with young children. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1997;151:777–786. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170450027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of Alaska, Office of Children’s Services (OCS) [accessed July 10, 2008];OCS family preservation. Available from. 2008 www.hss.state.ak.us/ocs/services.htm.

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suglia SF, Enlow MB, Kullowatz A, Wright RJ. Maternal intimate partner violence and increased asthma incidence in children buffering effects of supportive caregiving. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:244–250. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CS. Childhood experience of sexual abuse among Hong Kong Chinese college students. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:23–37. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CA, Guterman NB, Lee SJ, Rathouz PJ. Intimate partner violence, maternal stress, nativity, and risk for maternal maltreatment of young children. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:175–183. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau K, Burke J, Le T, Wan S, Weant M, et al. User’s manual for the ECLS-K base year restricted-use Head Start data files and electronic codebook. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) 2001-025; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Head Start Impact Study: First year findings. Washington, D. C.: USDHHS Administration for Children and Families; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Child maltreatment 2007. Washington, D. C.: USDHHS Administration on Children, Youth and Families; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. The future of child protection: How to break the cycle of abuse and neglect. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. Prevention and the child protection system. Future of Children. 2009;19:195–210. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Crooks CV, Lee V, McIntyre-Smith A, Jaffe PG. The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:171–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1024910416164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai F, Gao Q. Child maltreatment among Asian Americans: Characteristics and explanatory framework. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:207–224. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]