Abstract

Background

Unless metastatic or compressing the pancreatic duct, carcinoid of the pancreas are asymptomatic showing normal levels of serotonine and its metabolites in plasma and urine, thus resulting in delayed diagnosis and a consequent poor prognosis. However, if resection is timely accomplished, no local recurrence might be encountered and a normal survival might be expected in the absence of metastatic disease.

Case Presentation

The reported case of pancreatic carcinoid tumour in a 62-year-old woman reporting only atypical symptoms consisting of intermittent epigastric pain and nausea. Urinary 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid levels were within normal limits and only a slight elevation of serum serotonine level was detected on admission. After tumour localisation with endoscopic ultrasonography, left splenopancreasectomy with splenic, celiac and hepatic lymphadenectomy was carried out.

Conclusion

The role of endoscopic ultrasonography in early detection and precise localisation of pancreatic carcinoids, as well as the role of somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy with 111Indium labelled pentreotide in excluding distant metastases, are confirmed. The radical resection with lymphadenectomy is recommended in order to have a precise histological examination and detect occult lymph node metastases.

Keywords: Carcinoid, Pancreas

Introduction

Although carcinoid tumours are the most frequently occurring neuroendocrine tumours, its pancreatic localisation is an exceedingly rare, and often accidental [1]. In the largest published series of 8,305 cases of carcinoid tumours by Modlin and Sandor [2] only 46 (0.55%) were in the pancreas.

Unless metastatic or compressing the pancreatic duct, carcinoid tumours of the pancreas are asymptomatic, with normal levels of serotonine and its metabolites in plasma and urine [3]. Though the exact ratio of functioning versus nonfunctioning carcinoid tumours is not yet known, for pancreatic tumours it was estimated to be 1:10 [4]. In contrast, there are pancreatic carcinomas with neuroendocrine characteristics and carcinoid-like-symptoms [5]. For these reasons, a late diagnosis and a consequent poor prognosis are usual patterns for pancreatic carcinoid. In the Modlin and Sandor series [2], at the time of diagnosis, 76% of pancreatic carcinoid were non-localised, and the 5-year survival rate was only 34.1%.

In the recent revised classification of neuroendocrine tumours [6] the size of 2 cm seems to be of a crucial value over which carcinoid tumours start to exhibit a malignant behaviour. In other words, if resection is timely accomplished, no local recurrence might be encountered and a normal survival might be expected in the absence of metastatic disease [7].

We report a case of a primary pancreatic carcinoid with unusual clinical presentation that induced us to describe some insights on these infrequent tumours.

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman was referred to our Institution in February 1999 for intermittent epigastric pain and nausea, not always in relation to a meal. Clinical complaints of the patient began 12 months before our observation. During this period, her blood tests, upper GI endoscopy and abdominal computerised tomographic (CT) scan were found to be normal. Abdominal ultrasonography detected a 15 mm hypoechoic lesion in the pancreas, and dilatation of proximal pancreatic duct. In the past, the patient had undergone appendectomy, subtotal hysterectomy, a surgical treatment of the left shoulder for traumatic lesion of ligaments and surgical removal of a left benign breast nodule. During the previous year, the patient had suffered due to left leg phebitis complicated by minimal pulmonary embolism. She had a history of moderate smoking and alcohol intake for a long time and had been taking medicines (tranquillisers, vasodilators, antacids, analgesics). There was no history of weight loss. An abdominal examination did not evidence any abnormality.

Her haematological and biochemical parameters were unremarkable. Serum amylase and lipase levels were within normal range. Serum CEA and CA 19-9 levels were not elevated. Serum gastrin, glucagon, insulin, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) levels were within normal limits. Urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels were normal, but serum serotonine level was elevated on three occasions (430, 365 and 370 U/L respectively). Repeat CT scan of the upper abdomen and an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography failed to reveal any pathology.

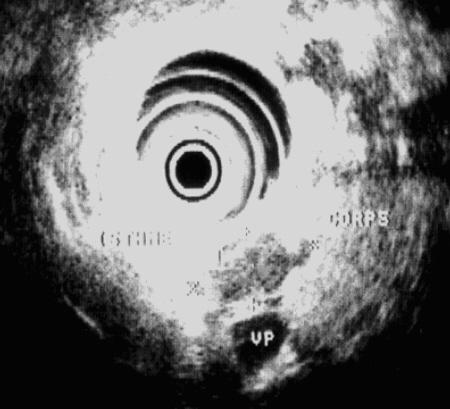

An endoscopic ultrasonography was performed with a mechanical sector scanner (Olympus®GF-UM 20, Hamburg, Germany), which detected a 20 × 10 mm hypoechogenic tumour located at the junction of the isthmus and body of the pancreas, confirming previous ultrasonographic report (Figure 1). However, there was no sign of proximal pancreatic duct dilatation as well as of vascular invasion or metastatic disease, as reported on earlier ultrasonographic examination. Somatostatin-receptor Scintigraphy with 111Indium labelled pentreotide (Octroscan®, Mallinckrodt, Petten, The Netherlands) revealed a accumulation of the radioligand in the region of the suspected tumour, and confirmed the absence of metastatic disease.

Figure 1.

Preoperative localization of the tumour with Endoscopic Ultrasonograhy. Endoscopic Ultrasonography performed with a mechanical sector scanner (Olympus GF-UM 20, Hamburg, Germany) showeda hypoechogenic tumour of 10 × 20 mm in diameter, located between the isthmus and the body of the pancreas with no signs of vascular invasion or proximal pancreatic canal distension.

In view of a localised pancreatic neoplasm, a surgical removal of the tumour was planned. At laparotomy, a pancreatic tumour was found by palpation on the left side of the portal vein. This was confirmed by intra-operative ultrasonography which showed an hypoechogenic, well-defined tumour, located between isthmus and corpus of the pancreas. The rest of the pancreas appeared normal. There was no evidence of metastasis in the liver and rest of the peritoneal cavity. Left spleno-pancreatectomy (distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy) with splenic, celiac and hepatic lymphadenectomy was accomplished.

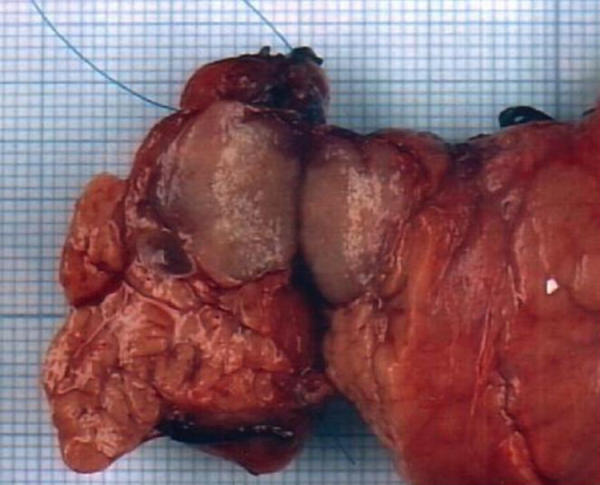

Gross examination (Figure 2) of the cut specimen showed a tumour near but not compressing the pancreatic duct, which was not dilated. There was no evident involvement of celiac, hepatic and splenic lymph nodes. On microscopic examination the cell arrangement appeared compatible with a neuroendocrine tumour. The argentaffin reaction of Fontana-Masson was negative while argyrophil reaction of Grimelius was positive. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated 100% tumour cell staining with chromogranine, anti-NSE and anti-synaptophysine antibodies. Staining with antibodies for gastrin, VIP, glucagon, insulin were negative. Tumour cells displayed strong immuno-reactivity to anti-serotonine antibodies.

Figure 2.

Gross appearance of the tumour in a cross-section of the pancreatic specimen. The tumour appears well demarcated from the surrounding parenchyma, is near to but not stenosing the pancreatic duct;

The above findings on pathological examination were conclusive of a diagnosis of a benign or low-grade malignant (functioning, well differentiated, non-angioinvasive) neuroendocrine EC cell (carcinoid) tumour of the pancreas in the Capella classification [6].

One year after her operation, the patient was free of symptoms, her serum levels of serotonine were within normal limits and she had no signs of distant metastases.

Discussion

Carcinoid tumours cannot be considered a rare disease any longer, with reports on large number of patients being published in medical literature [2,8]. Their incidence varies from 2.1 per 100,000 population per year [2] to 8.4 per 100,000 population per year [9]. It is likely that a significant percentage of carcinoid tumours remain asymptomatic and undetected during the lifetime of an individual.

According to their embryological origin, these tumours are classified into foregut carcinoid (respiratory tract, pancreas, stomach, proximal duodenum), midgut carcinoid (jejunum, ileum, appendix, Meckel's diverticulum, ascending colon) and hindgut carcinoid tumours (transverse and descending colon, rectum) [10]. This distinction may be useful, as carcinoid tumours from different areas have different clinical manifestations, humoral products and immunohistochemical features. Most of the classic syndromes relating to the overproduction of gastrointestinal and pancreatic hormones originate from foregut carcinoid. Most of the cases are thought to secrete such low amounts of hormones that it causes no clinical symptoms, and hormones hypersecretory states cannot be detected [11].

In the present report, only a slight increase in serum serotonine levels occurred without any increase in urinary levels of its metabolites (5-HIAA). This is consistent with a benign behaviour of our patient, as the tumours become symptomatic only when hepatic metastases occur, which manifests as classic carcinoid syndrome. It is not clear whether such behaviour can be attributed to a benign tumour alone or to an early stage malignant tumour too. In classic histological terminology, carcinoid lesions are widely regarded as malignant neoplasms, [10,12] however, there are no precise histological criteria to distinguish benign from malignant carcinoid or the carcinoid with metastatic potential. The possibility of a cure in these patients is directly related to an early diagnosis. Unfortunately, as these lesions are asymptomatic or have non-specific clinical manifestations, as in our case the diagnosis is often delayed. The most frequent symptoms associated with pancreatic carcinoid tumours are abdominal pain (66%) and diarrhoea (52%), related to intestinal hypermotility [7]. In some reports [13-16] pancreatitis seemed to be the consequence of the ductal obstruction by the tumour, while in one report [7] a recurrent pancreatitis was present for more than 10 years before the onset of the first symptoms attributed to a carcinoid. The pathogenesis of the abdominal pain in our patient is difficult to ascertain, as no associated pancreatitis, pancreatic duct dilation or neural invasion were detected at the pathological examination. We suspected that symptoms in our patient might be related to functional or transient events in the intestine or in the pancreatic duct due to episodic humoral or enzymatic secretions by the tumour. This is supported by the intermittent nature of the abdominal pain and the ultrasonographic finding of pancreatic duct dilation at the first instance, which was not detected on subsequent examinations.

Endoscopic Ultrasonography is a useful test for detecting and precisely localizing a tumour within the pancreas [17]. Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy with 111Indium labeled pentreotide is useful in confirming the neuroendocrine mass and excluding distant metastases [18]. Both these investigations could successfully diagnose and localise the carcinoid tumour in our patient. More extensive application of these two investigations in clinical practice may result in early detection of neuroendocrine tumours even in patients with no or only non-specific complaints.

Meanwhile, one should be aware of the existence of pancreatic carcinoid tumours. For the tumours limited to the pancreas and no evidence of distant metastases, a radical resection with lymphadenectomy can result in a precise histological characterisation of tumour and detection of occult lymph node metastases [19]. Resection at this stage may be curative.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Professor M. F. Lebodic (Department of Pathology, CHU Nantes, France) for the immunohistochemical study.

Contributor Information

Olivier Saint-Marc, Email: olivier.saint-marc@chr-orleans.fr.

Andrea Cogliandolo, Email: olivier.saint-marc@chr-orleans.fr.

Alessandro Pozzo, Email: olivier.saint-marc@chr-orleans.fr.

Rocco Roberto Pidoto, Email: olivier.saint-marc@chr-orleans.fr.

References

- Buchanan KD, Johnston CF, O'Hare MM, Ardill JE, Shaw C, Collins JS, Watson RG, Atkinson AB, Hadden DR, Kennedy TL, et al. Neuroendocrine tumours. A European view. Am J Med. 1986;81:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlin IM, Sandor A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumours. Cancer. 1997;15:813–829. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<813::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JM. Carcinoid tumour and the carcinoid syndrome. Curr Probl Surg. 1989;26:835–885. doi: 10.1016/0011-3840(89)90010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzfeldt W. Endocrine tumours of the pancreas. In: Volk BW, Arquilla ER, editor. The diabetic pancreas. New York, Plenum Publishing Corporation; 1985. pp. 543–586. [Google Scholar]

- Eusebi V, Capella C, Bondi A, Sessa F, Vezzadini P, Mancini AM. Endocrine pancreatic cells in pancreatic exocrine carcinomas. Histopathology. 1981;5:599–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1981.tb01827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella C, Heitz PU, Hoefler H, Solcia E, Kloeppel G. Revised classification of neuroendocrine tumours of the lung, pancreas and gut. Virchows Arch. 1995;425:547–560. doi: 10.1007/BF00199342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer CA, Baer HU, Dyong TH, Mueller-Garamvoelgyi E, Friess H, Ruchti C, Reubi JC, Buchler MW. Carcinoid of the pancreas: clinical characteristics and morphological features. Eur J Cancer. 1996;7:1109–1116. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin JD. Carcinoid tumours. an analysis of 2837 cases. Cancer. 1975;36:560–569. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197508)36:2<560::aid-cncr2820360235>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge T, Linell F. Carcinoid tumours. Frequency in a defined population during a 12-year-period. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand[a] 1976;844:322–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ED, Sandler M. The classification of carcinoid tumours. Lancet. 1963;1:238–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(63)90951-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzfeldt W, Stockmann F. Carcinoids and carcinoid syndrome. Am J Med. 1987;82:4–16. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberndorfer S. Karzinoide tumoren des dunndarms. Frankf Z Pathol. 1907;1:426–429. [Google Scholar]

- Patchefsky AS, Solit R, Phillips LD, Craddock M, Harrer MV, Cohn HE, Kowlessar OD. Hydroxyindole-producing tumours of the pancreas, carcinoid-islet cell tumour and oat cell carcinoma. Ann Int Med. 1972;77:53–61. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-1-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchenfsky AS, Gordon G, Harrer WV, Hoch WS. Carcinoid tumour of the pancreas. Ultrastructural observations of a lymph node metastasis and comparison with bronchial carcinoid. Cancer. 1974;33:1349–1354. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197405)33:5<1349::aid-cncr2820330520>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai E, Yamaguchi K, Hashimoto H, Sakurai T. Carcinoid tumour of the pancreas with obstructive pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taidi C, Soyer P, Barge J, Amouyal P, Levesque M. Tumeur carcinoide primitive du pancreas. J Radiol. 1993;74:347–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosch T, Lightdale CJ, Botet JF, Boyce GA, Sivak MV, Jr, Yasuda K, Heyder N, Palazzo L, Dancygier H, Schusdziarra V, et al. Localisation of pancreatic endocrine tumours by endoscopic untrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1721–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206253262601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisker O, Bartsch D, Weinel RJ, Joseph K, Welcke UH, Zaraca F, Rothmund M. The value of somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy in newly diagnosed endocrine gastroenteropancreatic tumours. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe BM. Surgery for gut hormone-producing tumours. Am J Med. 1987;82:68–76. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]