Abstract

Background

Despite reports on association between overweight/obesity among women and household food insecurity (FI) in developed countries, such association is not evident in developing countries. This study aimed to assess the association between household FI and weight status in adult females in Tehran, Iran.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, 418 households were selected through systematic cluster sampling from 6 districts of Tehran. Height and weight were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Socio-economic status of the household was assessed by a questionnaire. Three consecutive 24-hour diet recalls were completed. FI was measured using adapted Household Food Insecurity Access Scale. Logistic regression was used to test the effects of SES and food security on weight status, simultaneously. Using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) potential causal relationships between FI and weight status was explored.

Results:

Only 1.0% of women were underweight, while 40.3% were overweight and 33% were obese, respectively. Severe, moderate, and mild food insecurity was observed in 11.5, 14.7, and 17.8%, respectively. Among women in moderately food insecure households, the possibility of overweight was lower than those of food secure households (OR 0.41; CI95%:0.17–0.99), while in severely food insecure households, the risk of abdominal obesity for women was 2.82 times higher than food secures (CI95%:1.12–7.08) (P<0.05). SEM detected no causal relationship between FI and weight status.

Conclusion:

Association of severe food insecurity with abdominal obesity in adult females of households may indicate their vulnerability and the need for tailoring programs to prevent further health problems in this group.

Keywords: Overweight, Abdominal obesity, Women, Food security, Household, Iran

Introduction

Food insecurity is “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable food in socially acceptable ways”(1). Recent evidence, mostly from the US, has suggested that limited access to food at the household level may be associated with overweight and/or obesity in women (2–5); in children the evidence is mixed (6). The few available reports on developing nations have shown different results. Whether such association also holds in countries undergoing nutrition transition is of question (7). In Malaysia with rapid socioeconomic and demographic changes due to stable economic growth and political development, after adjusting for factors that are related to both adiposity and food insecurity, women from food insecure households were significantly more likely to have at risk level of waist circumference, but were not obese (8). Reversely, in Colombia, food insecurity was highly prevalent and predicted underweight, but not overweight in both adults and school age children (9).

Townsend et al. (5) in 2001 proposed that food insecurity may influence body weight in two opposing ways: weight gain or weight loss. Food insecurity can influence weight gain by causing inappropriate eating patterns and this pathway may predominate in mildly food insecure households. On the other hand, severe food insecurity can promote weight loss. These associations may vary in different societies based on specific coping strategies in response to food insecurity (2). The fact that both problems (overweight and under nutrition) can exist in the same households poses a dilemma both in inferring causality and in communicating nutrition problems to policy-makers and in planning nutrition interventions (3).

Iran is undergoing drastic epidemiologic and nutrition transitions. Rise in the prevalence of obesity and overweight, especially in women, is a feature that is turning into a major public health problem (10). At the same time (early 2000s), food insecurity was prevalent in 23% of the Iranian households (11). Exploring the probable association between the two is of great importance.

The study entitled “Measurement and Modeling of Household Food Security in Urban Households in the City of Tehran” during 2009–2010 was a comprehensive study undertaken in 6 socio-economically different districts of Tehran, and provided the opportunity for testing such possible association (12). In this study, for the first time, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to explore possible causal relationships between household FI and weight status in women.

The present analysis was designed to investigate the relationship between food insecurity and weight status of women in households residing in Tehran city, controlling for the effect of other related factors.

Materials and Methods

Design:

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the framework of a study on “Measurement and Modeling of Household Food Security in Urban Households in the City of Tehran” during 2009–2010 (12). The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (NNFTRI), Faculty of Nutrition Sciences and Food Technology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Subjects:

With respect to the 22% estimated prevalence of FI in Iran (11), a sample size of 412 households was estimated based on the following formula:

Through systematic cluster sampling, 418 households were selected from 6 districts (out of 22 districts) in Tehran, the capital of Iran. The number of households in each district was determined based on the population. The districts were chosen based on the socio-economic status (SES) of residents in the city municipality. As the highest SES groups in Tehran are residents of districts 1–3, about one third of the studied households were chosen from these districts. The same approach was taken for districts 10 and 12 as medium SES (middle incomes) and districts 18 and 20 as low SES districts (12). The calculation of sample size and sampling frame was designed to represent adult women in the households of Tehran city. Consent was obtained from the male head of each household and his wife. Data were collected through home interviews by nutritionists who were trained in a one-week training workshop.

Socio-economic status:

Data on demographic and socio-economic status (SES) of the households was assessed by a questionnaire completed by trained nutritionists through structured interviews. Information on age, sex, education level, and occupational status of head and his wife, as well as family size, household expenditures, residency, and living conditions were obtained.

Anthropometric measurement:

Height, weight, and waist circumference (WC) were measured based on standard protocols (13) and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Weight status of adult women of family (preferably spouse of the head or the woman responsible for food preparation aged 20 years or older) was defined based on cut off values recommended by NIH as follows: underweight: BMI<18.5; normal weight: 18.5<BMI<24.9; overweight: 25.0<BMI<29.9; and obese: BMI≥30 Kg/m2. Waist circumference ≥88 cm was considered as abdominal obesity in women (13).

Food Intake Assessment:

Food intake data were collected using three 24hour diet recalls (two week-days and one weekend holiday) by trained nutritionists in three consecutive days. Each interview took approximately 45 minutes to 1 hour. The interviewee was chosen among the household members who were responsible for food preparation and cooking (mainly the wife of the household head).

Food Insecurity Measurement:

A locally adapted version of the HFIAS (Household Food Insecurity Access Scale) originally developed by USAID’s Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) project was used to classify households as food secure or mildly, moderately or severely food insecure. The HFIAS (Household Food Insecurity Access Scale) is an adaptation of HFSSM (Household Food Security Survey Module) which has consistently been validated as a statistically reliable and meaningful measure of food insecurity in the US (14). The methodology for adapting and validating the scale is presented elsewhere (12).

Statistical analysis:

The questionnaires were checked for incompleteness and irregularities before the second and third visits. Then each food item was coded. Special software was designed to enter food consumption data and do all calculations. To determine the nutrient content of existing Iranian household diets, a modified version of an old Iranian food composition table was used (15). Because of insufficient data for bread, which is a major contributor to iron intake in Iranian diets, iron content data for Iranian flat breads were imported into the food composition tables based on biochemical analyses which took place after publication of the tables (11). Data were analyzed by SPSS software (Ver 16.0) using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi-square tests. Logistic regression was used to test the effects/association of SES and food security on weight status, simultaneously. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

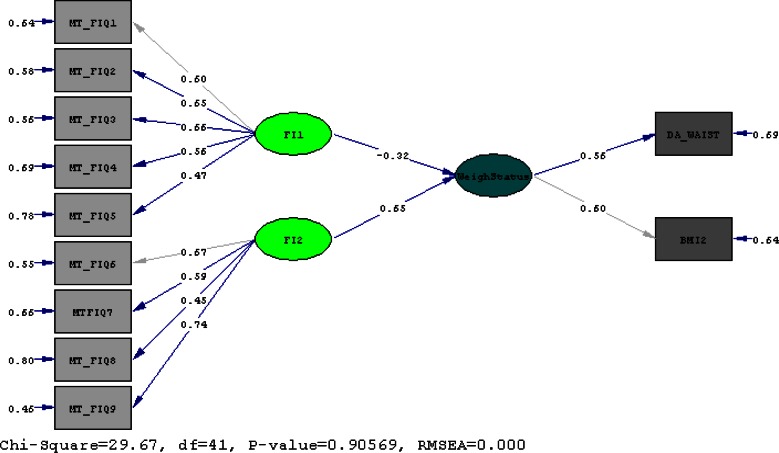

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to explore possible causal relationships between household FI and weight status in women by LISREL 8.5 software. Goodness of fit indices of the proposed model and path coefficients were estimated using Maximum likelihood. The “t” values greater than 2 were considered significant. The χ2/df ratio of 2.00 or less and Goodness of fit indices (GFI, AGFI) higher than 0.95 and PMSR near to 0.05 were considered as good fit (16–17).

Results

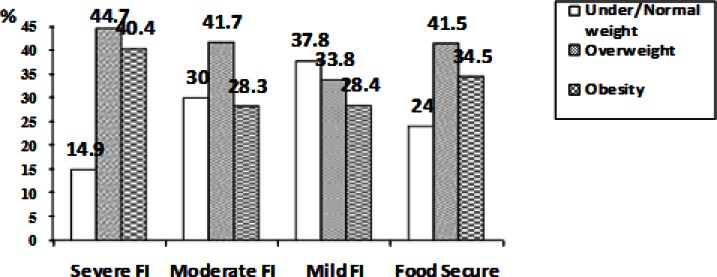

Food insecurity (severe, moderate and mild) characterized 11.5, 14.7, and 17.8% of households, respectively. The overall sample of women included 40.3% overweight and 33.0% obese. Only 4 women (1%) were underweight, thus underweight and normal-weight women were pooled into one group in all analyses. Waist circumference in 44.4% of women was identified as at risk. Figure 1, presents the prevalence of under- and normal weight, overweight, and obesity in relation to household food insecurity. There was no significant difference between the three groups in term of food security status.

Fig. 1:

Prevalence of under-and normal weight, overweight and obesity in different levels of household food insecurity in Tehran/ no significant difference using chi-square

Tables 1 and 2 compare demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the households for under- and normal weight, overweight and obese women. Age, family size, score of facilities in the house, and food expenditures were significantly higher for overweight and obese women as compared to under/normal weight women.

Table 1:

Mean (±SE) of age of household head, family size, per capita measurement of house, per capita number of rooms, expenditures and income of Iranian households based on weight status of adult females

| Variable | Weight status (Mean±SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under/ Normal weight (n=110) | Overweight (n=166) | Obese (n=136) | Total (n=412) | |

| Age of household head (year) | 44.0±1.4 | 50.2±1.1* | 53.0±1.1* | 49.5±0.7 |

| Age of adult female (year) | 39.2±1.4 | 45.5±1.1* | 47.1±1.1* | 44.3±0.7 |

| Family size (numbers) | 3.6±0.1 | 3.8±0.1 | 4.0±0.1‡ | 3.8±0.1 |

| Area of house (square meter) | 99.6±7.4 | 105.1±4.6 | 100.20±4.3 | 102.0±3.70 |

| Number of rooms | 2.62±0.11 | 2.81±0.09 | 2.75±0.08 | 2.74±0.05 |

| Score of facilities in the house | 6.8±0.3 | 7.4±0.2 | 7.7±0.2† | 7.3±0.1 |

| Household expenditures (1000 Iranian Rials) | ||||

| Food expenditure (1000 Iranian Rials) | 2275±166 | 2601±121 | 2992±150* | 2647±83 |

| Clothing expenditure (1000 Iranian Rials) | 558±86 | 457±63 | 439±45 | 477±37 |

| Rent expenditure & loan (1000 Iranian Rials) | 2651±374 | 2053±339 | 1984±387 | 2186±212 |

| Water, electricity. gas & Telephone expenditure (1000 Iranian Rials) | 514±57 | 579±45 | 577±46 | 562±28 |

| Educational expenditure (1000 Iranian Rials) | 404±110 | 814±163 | 768±185 | 693±95 |

| Leisure expenditure (1000 Iranian Rials) | 314±110 | 362±89 | 270±47 | 319±48 |

| Transfer expenditure (1000 Iranian Rials) | 177±29 | 171±28 | 144±21 | 163±15 |

| Other expenditure (1000 Iranian Rials) | 313±129 | 213±55 | 147±24 | 216±40 |

| Total Expenditure (1000 Iranian Rials) | 6262±646 | 6008±452 | 6291±578 | 6170±315 |

| Monthly income (from employment) (1000 Iranian Rials) | 6746±825 | 7401±804 | 6962±693 | 7087±454 |

| Other Income (1000 Iranian Rials) | 1611±980 | 877±251 | 722±157 | 1020±283 |

Significant difference with underweight & normal weight women using ANOVA (p<0.001)

Significant difference with underweight & normal weight women using ANOVA (p<0.01)

Significant difference with underweight & normal weight women using ANOVA (p<0.05)

Table 2:

Frequency of different levels of weight status of adult females based on socioeconomic variables (sex, marital status, educational, occupational and housing status) in Iranian households (n=416)

| Variable | Under / Normal weight (n=110) | Overweight (n=166) | Obese (n=136) | Total (n=412) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Districts | 1&3 (High SES) | 40 (36.4) | 49 (29.5) | 37 (27.2) | 126 (30.6) |

| 10&12 (Moderate SES) | 48 (43.6) | 91 (54.8) | 74 (54.4) | 213 (51.7) | |

| 18 & 20 (Low SES) | 22 (20.0) | 26 (15.7) | 25 (18.4) | 330 (17.7) | |

| Gender of head | Male | 100 (90.9) | 151 (91.0) | 123 (90.4) | 374 (90.8) |

| Female | 10 (9.1) | 15 (9.0) | 13 (9.6) | 38 (9.2) | |

| Educational level of spouse | Illiterate | 7 (6.4) | 19 (11.4) | 14 (10.3) | 40 (9.7) |

| Primary | 13 (11.8) | 29 (17.5) | 37 (27.2) | 79 (19.2) | |

| Secondary | 29 (26.4) | 40 (24.1) | 41 (30.1) | 110 (26.7) | |

| High school diploma and higher | 61 (55.5) | 78 (47.0) | 44 (32.4) | 183 (44.4) | |

| Occupation of spouse | Unemployed, Student, Housekeeper | 89 (80.9) | 147 (89.1) | 126 (92.6) | 362 (88.1) |

| Laborer, Farmer, Animal Husbandry | 3 (2.7) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (0.7) | 7 (1.7) | |

| Freelancer, Shopkeeper, Driver | 8 (7.3) | 5 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) | 16 (3.9) | |

| Employee, Teacher/Tutor | 9 (8.2) | 10 (6.1) | 6 (4.4) | 25 (6.1) | |

| Manager, Doctor, Pilot, Employer | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Educational level of head | Illiterate | 4 (3.6) † | 11 (6.6) | 11 (8.1) | 26 (6.3) |

| Primary | 22 (20.0) | 31 (18.7) | 23 (16.9) | 76 (18.4) | |

| Secondary | 28 (25.5) | 51 (30.7) | 50 (36.8) | 129 (31.3) | |

| High school diploma and higher | 56 (50.9) | 73 (44.0) | 52 (38.2) | 181 (43.9) | |

| Occupation of head | Unemployed/ Student/ Housekeeper | 10 (9.1) | 19 (11.5) | 15 (11.1) | 44 (10.7) |

| Laborer | 20 (18.2) | 21 (12.7) | 27 (20.0) | 68 (16.6) | |

| Freelancer | 43 (39.1) | 66 (40.0) | 49 (36.3) | 105 (25.6) | |

| Employee/ Teacher | 26 (23.6) | 41 (24.8) | 38 (28.1) | 105 (25.6) | |

| Manager/ Doctor | 11 (10.0) | 18 (10.9) | 6 (4.4) | 35 (8.5) | |

| Possession of house | Private ownership | 50 (45.9)† | 102 (61.4) | 95 (69.9) | 247 (60.1) |

| Rent | 46 (42.2) | 47 (28.3) | 35 (25.7) | 128 (31.1) | |

| Free of cost | 13 (11.9) | 15 (9.0) | 6 (4.4) | 34 (8.3) |

Figures in the parentheses are indicative of percents

Significant difference between groups using chi-square test (P<0.01)

Obese women reported lower consumption of vegetables and fats; as well as energy and all macronutrients compared to under-and normal weight women (Table 3 and 4).

Table 3:

Mean (±SE) of daily food groups consumed of adult females in Iranian households by weight status

| Food groups consumed(gr/d) | Under/ Normal weight (n=110) | Overweight (n=166) | Obese (n=136) | Total (n=412) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bread & cereals | 344.9±14.4 | 320.6±11.3 | 317.3±11.9 | 326.0±7.1 |

| Legumes | 76.2±7.7 | 61.7±5.4 | 70.5±6.4 | 68.7±3.7 |

| Vegetables | 246.7±13.7 | 225.4±11.1 | 207.5±10.1* | 225.0±6.7 |

| Fruits | 249.1±14.6 | 242.7±14.8 | 259.4±17.4 | 250.1±9.2 |

| Meats | 70.5±4.3 | 67.5±3.5 | 68.7±4.0 | 68.7±2.2 |

| Eggs | 44.8±2.6 | 45.3±2.7 | 42.1±2.7 | 44.1±1.5 |

| Milk & dairy products | 297.3±19.3 | 267.1±16.2 | 257.5±15.3 | 271.9±9.7 |

| Nuts & dried fruits | 20.2±2.1 | 14.9±1.3* | 17.3±2.1 | 17.2±1.1 |

| Fats and oils | 31.7±2.1 | 27.8±1.7 | 25.1±1.5* | 27.9±1.0 |

| Sugar | 24.0±1.8 | 22.5±1.2 | 20.4±1.4 | 22.3±0.8 |

Significant difference with underweight & normal weight women using ANOVA (p<0.05)

Table 4:

Mean (±SE) of daily nutrient intakes of adult females in Iranian households by weight status

| Energy & Nutrient intakes | Under / Normal weight (n=110) | Overweight (n=166) | Obese (n=136) | Total (n=412) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (Kcal/d) | 1801.3±60.2 | 1604.9±49.2* | 1599.5±44.5* | 1655.6±29.7 |

| Carbohydrate(gr/d) | 259.3±8.8 | 238.0±6.9 | 243.2±7.3 | 245.4±4.4 |

| Protein (gr/d) | 57.8±2.0 | 51.2±1.4* | 53.1±1.4† | 53.6±0.9 |

| Fat (gr/d) | 61.6±2.9 | 51.6±2.3* | 47.9±1.8‡ | 53.1±1.4 |

| Calcium (mg/d) | 698.1±29.0 | 660.3±22.4 | 662.3±22.1 | 671.0±13.9 |

| Iron (mg/d) | 10.8±0.4 | 9.9±0.3 | 10.5±0.4 | 10.3±0.2 |

| Thiamin (mg/d) | 1.42±0.52 | 1.30±0.53 | 1.35±0.04 | 1.35±0.03 |

| Riboflavin (mg/d) | 1.19±0.04 | 1.08±0.03† | 1.09±0.03 | 1.11±0.02 |

| Niacin (mg/d) | 17.5±0.46 | 16.0±0.5 | 16.7±0.5 | 16.6±0.3 |

| Vitamin C (mg/d) | 102.0±6.0 | 102.3±5.0 | 105.9±5.9 | 103.4±3.2 |

| Vitamin A (μgRE/d) | 623.6±45.3 | 578.3±35.3 | 608.6±40.8 | 600.4±23.0 |

| Retinol (mg/d) | 1722.1±108.6 | 1680.8±87.6 | 1540.2±82.5 | 1645.4±53.2 |

Significant difference with underweight & normal weight women using ANOVA (P<0.01)

Significant difference with underweight & normal weight women using ANOVA (P<0.05)

Significant difference with underweight & normal weight women using ANOVA (p<0.001)

For women in moderately food insecure households, the risk of overweight was lower (OR 0.41, CI95%:0.17–0.99, P<0.05). In severely food insecure households, however, the risk of abdominal obesity in women was significantly elevated compared to those in food secure households (OR 2.82, CI95%:1.12–7.08, P<0.05) (Table 5). The model shown in Table 5 was adjusted for additional variables including marital status, age, educational and occupational level of household head and spouse, family size, possession of house, number of rooms, score of facilities in the house, monthly expenditure, and income and consumption of food groups.

Table 5:

Logistic regression model for predicting overweight and abdominal obesity in adult females of Iranian households

| Variables | Overweight (n=296) | Abdominal obese (n=178) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Food secure | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Mild food insecurity | 0.44 (0.19–1.05) | NS | 1.46 (0.66–3.23) | NS |

| Moderate food insecurity | 0.41 (0.17–0.99) | <0.05 | 0.67 (0.29–1.56) | NS |

| Severe food insecurity | 2.05 (0.64–6.56) | NS | 2.82 (1.12–7.08) | <0.05 |

The model is adjusted for marital status, age, educational, and occupational level of women and household head, family size, possession of house, number of rooms, score of facilities in the house, monthly expenditure and income, and consumption of food groups.

No potential causal relationships were found between food insecurity and weight status (based on BMI and waist circumference) of the studied women, based on SEM (t<2) (Fig. 2). Confirmatory factor analysis categorized the 9 items of HFIAS into two factors (FI1 and FI2).

Fig. 2:

Structural Equation modeling of relationship between food insecurity (1) and weight status of women in Tehrani households/Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.95, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) =0.92/ *t<2.00, not significant

Discussion

The findings show that urban Tehrani women in severely food insecure households are more likely to be centrally obese or have high WC than those in food secure households. Adversely moderate food insecurity was negatively associated with overweight in women. However, path analysis revealed no potential causal relationships between FI and weight status.

A number of studies in developed countries have shown strong associations between food insecurity and obesity among women (18–20). Gender and marital status may also have effects on the associations between food insecurity and body weight in NHANES participants (21). Compared with fully food-secure women, those in marginally food-secure households showed a tendency to be overweight, whereas women with low food security were more likely to be obese (21). Food insecurity was related to a greater likelihood of obesity among married women, those living with partners, and widows, as compared to never-married women. Our findings also confirm the association between severe food insecurity and the likelihood of abdominal obesity among women; there was not enough variation in the marital status variable to explore a relationship between marital status and obesity.

In our previous work, we had reported that overweight in women from severely and moderately food insecure households, was 1.5 times more (P<0.001) and in mild food insecure households1.2 times (P<0.001) more than their food secure counterparts (22). However, the definition of food insecurity was based on three levels of daily energy intake and it can ignore the fact that overweight and obese individuals may actually consume less dietary energy in order to control their weight.

Many of these studies were cross-sectional analyses using only a few response variables to determine FI. The study by Kaiser et al. (23) examined FI and obesity in low income Latino women in California using both the 18-item US Household Food Security Scales and a single item on food insufficiency. The single item measure showed no relationship while the larger scale showed a significant relationship between obesity and FI. Future research, using better instruments to measure FI, may find stronger associations. While the work done to date does indicate an association between food insecurity and overweight, stronger study designs is required to determine causal relationships.

In a prospective study (24) on 1707 mothers of preschool children, changes in food security status over 2 year were not significantly associated with changes in weight. These findings do not support a causal association between food insecurity and obesity. However, the two-year period of this study probably is not long enough to detect such a causal relationship. Olson and Strawderman (25) showed obesity combined with food insecurity presented the greatest risk for major weight gain in a cohort sample of women in childbearing age and obesity appeared to lead to food insecurity rather than the converse.

In developing countries, the limited numbers of studies has revealed inconsistent results. In Malaysia, Shariff and Khor (8) examined nutritional outcomes related to body fat accumulation of food insecurity among women from selected rural communities. Using the Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument, after adjusting for factors that are related to both adiposity and food insecurity, women from food-insecure households were significantly more likely to have at risk WC, but no association was observed with obesity. In Uganda (26), the association of food insecurity with overweight and at-risk waist circumference, after adjusting for potentially confounding effects of several factors was diminished. It was concluded that the potential impact of food insecurity on weight status may partly be expressed via variations of such factors.

In Colombia, Trinidad and Tobago, hunger in the household was significantly associated with maternal underweight, but not overweight. These studies concluded that food insecurity does not necessarily predict overweight in countries undergoing nutrition transition (9, 27). Association between SES and obesity is also attributed to the degree of economic development of the country (28). BMI in women was positively related to energy intake, age, and dependency ratio and negatively associated with educational level (29–30). At the time of the study, women with higher educational levels may have been more likely to be employed than the others, and thus have had higher physical activity, and more adequate dietary intake. Therefore, education and occupation may help to prevent overweight/obesity in women (29). Further studies on employed women indicated that type of job and socio-economic status of women probably affects this association (31).

The mechanism behind the association observed between food insecurity and obesity among women remains unclear. Researchers have suggested a number of mechanisms, most having to do with low income mothers’ coping strategies, including managing limited resources of food and sacrificing their own nutrition in order to protect their children from hunger (14). It is believed that inadequate resources and putting children’s needs first, can create a chronic “feast or famine” situation, which appears to contribute to maternal obesity. Food deprivation can cause a preoccupation with food that has the potential to cause obesity, which results in overeating at the times during which they have access to adequate amounts of food (32–33). Women lacking adequate resources may be purchasing less expensive energy-dense foods, such as refined grains, sugar, and fat in order to stave off hunger, or avoiding fruits and vegetables because of their cost (34).

Food insecurity and obesity may be associated because they both share a common cause: poverty. In particular, poverty in childhood may play this role. Hunger and food insecurity related to poverty in childhood may contribute to poverty’s impact on adult obesity (32). In addition, food insecurity may be a stressor that results in a stress response that leads to disordered eating, reduced physical activity and depression, all of which may be related to weight gain (35), or food insecurity and/or poverty may cause a stress response that is hormonal, causing central patterning of fat deposition (32).

Furthermore, low-income families live in neighborhoods with more obesogenic characteristics. It is shown that grocery stores in low-income neighborhoods are less likely to have healthy foods, mainly due to the higher price of such foods (36). In Iran, households with low socio-economic status consume higher amount of bread, cereals, and sugar and lower fruits, vegetables, and milk than high SES groups (37–38). Change in the price of the last three food groups is shown to have effect on the level of their consumption by low-income households (39). In addition, low-income neighborhoods often have few safe or attractive places to play or be physically active. Open space is at a minimum and recreational facilities often are inadequate. Less pleasant scenery in low-income neighborhoods on one hand (14, 32) and socio-cultural norms, including dress codes in traditional and religious societies including Iran, discourages recreational walking, especially in women (40).

Important limitations to the present study, included lack of data on physical activity level and receiving food support from the government relief program (Relief Committee of Imam Khomeini) in the studied households. The latter variables could be important factors influencing the relationship between food insecurity and weight status for women (33).

Conclusion

In the present study, for the first time, SEM was used for modeling the relationship between FI and weight status of women. Although no causal relationships between FI and weight status of women was observed, it was shown that central obesity is more likely in severely food insecure households of Tehran City while moderate food insecurity was negatively associated with overweight in women. The findings are in line with those in other developing countries with the same degree of development, such as Malaysia.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, Informed Consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (NNFTRI), Faculty of Nutrition Sciences and Food Technology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences [grant number P/25/47/1012] as part of a PhD thesis entitled “Measurement and Modeling of Household Food Security in Urban Households in the City of Tehran” in which the first author was the PhD student and the corresponding author was the supervisor. The authors declare no conflict of interest and are grateful to the Director and personnel of NNFTRI, and all workers and participants of the project. We also thank Dr Hossein Ghassemi for his valuable comments.

References

- 1.James W, Schofield E. FAO Human Energy Requirement: A Manual for Planners and Nutritionists. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams E, Grummer-Strawn L, Chavez G. Food insecurity is associated with increased risk of obesity in California women. J Nutr. 2003;133(4):1070–4. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison GG. The paradox of hunger and obesity. Proceedings of 8th Iranian Nutrition Congress; Tehran, Iran. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarlio-Lähteenkorva S, Lahelma E. Food insecurity is associated with past and present economic disadvantage and body mass index. J Nutr. 2001;131:2880–4. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Townsend M, J JP, Love B, Achterberg C, Murphy S. Food insecurity is positively related to overweight in women. J Nutr. 2001;131(6):1738–45. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.6.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietz W. Does hunger cause obesity? Pediatr. 1995;95:766–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Upadhyay RP, Palanivel C. Challenges in Achieving Food Security in India. Iranian J Publ Health. 2011;40(4):31–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shariff Z, Khor G. Obesity and household food insecurity: evidence from a sample of rural households in Malaysia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(9):1049–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isanaka S, Mora-Plazas M, Lopez-Arana S, Baylin A, Villamor E. Food insecurity is highly prevalent and predicts underweight but not overweight in adults and school children from Bogotá, Colombia. J Nutr. 2007;137:2747–55. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.12.2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghassemi H, Harrison G, Mohammad K. An Accelerated Nutrition Transition in Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2005;5(1A):149–55. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalantari N, Ghaffarpour M. National Comprehensive Study on Household Food Consumption Pattern and Nutritional Status IR IRAN, 2001–2003. Tehran: Nutrition Research Department, National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, Shaheed Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammadi F, Omidvar N, Houshiar-Rad A, Khoshfetrat M, Abdollahi M, Mehrabi Y. Validity of adapted Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) In Iran. Public Health Nutr. 2011;2:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011001376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute of Health & National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in adults: The Evidence Report. Obes Res. 1998;6(suppl 2):S51–S209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on National Statistics (CNSTAT) Food Insecurity and Hunger in the United States: An Assessment of the Measure. Washington DC: US Department of Agriculture’s Measurement of Food Insecurity and Hunger, National Research Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkissian N, Rahmanian M, Azar M, Mayourian H, Khalili S. Food Composition Table of Iran: raw materials. Tehran: Institute of Nutrtiion Sciences & Food Technology; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joreskog K, Sorbom D. LISREL 8.30 and PRELIS 2.30. Scientific Software International Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norris AE. Path Analysis. In: Munro BH, Connel WF, editors. Statistical Methods for Health Care Research. 5th ed. Massachusetts: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 377–404. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frongillo E, Olson C, Rauschenbach B, Kendall A. Nutritional consequences of food insecurity in a rural New York state County. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 1997. Institute for Research on Poverty, Discussion Paper no. 1120-97. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olson C. Nutrition and hunger outcomes associated with food insecurity and hunger. J Nutr. 1999;129:521S–4S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.521S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crawford P, Townsend M MD, Smith D, Epinoza-Hall G, Donahue S, et al. How can Californians be overweight and hungry? California Agriculture. 2004;58(4):12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanson K, Sobal J, Frongillo E. Gender and marital status clarify associations between food insecurity and body weight. J Nutr. 2007;137(6):1460–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.6.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadi F, Omidvar N, Houshiar-Rad A, Mehrabi Y, Abdollahi M. Association of food security and body weight status of adult members of Iranian households. Nutrition Sciences & Food Technology Journal. 2008;(3):41–53. [In Farsi] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaiser L, Melgar-Quinozez H, Lamp C, Johns M, Sutherlin J, Harwood J. Food insecurity and nutritional outcomes of preschool-age Mexican-American children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:924–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitaker R, Sarin A. Change in food security status and change in weight are not associated in urban women with preschool children. J Nutr. 2007;137:2134–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.9.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olson CM, Strawderman MS. The Relationship between food insecurity and obesity in rural childbearing women. The Journal of Rural Health. 2008;24(1):60–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaput J-P, Gilbert J-A, Tremblay A. Relationship between food insecurity and body composition in Ugandans living in urban Kampala. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1978–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulliford MC, MAhabir D, Rocke B. Food insecurity, food choices and body mass index in adults: nutrition transition in Trinidad and Tobago. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:508–16. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subramanian S, Perkins JM, Özaltin E, Smith GD. Weight of nations: a socioeconomic analysis of women in low- to middle-income countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:413–21. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghassemi H, Kimiagar M, Koupahi M. Food and Nutrition Security in Tehran Province. Tehran: National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghassemi H. Food and Nutrition Security in Iran: A National Study on Planning and Administration. Tehran: Plan and Budget Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omidvar N, Dastgiri S. The study of impact of employment on BMI as an index for health assessment. Proceedings of the first National Scientific/Applicable Conference on Women and Work; Government of Sistan & Baloochestan Province: The Women Affairs Commission; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olson C. The Roundtable on Understanding the Paradox of Hunger and Obesity. Washington, DC: Food Research and Action Center (FRAC); 2005. The Relationship Between Hunger and Obesity: What Do We Know and What Are the Implications for Public Policy. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dinour LM, Bergen D, Yeh M-C. The food insecurity–obesity paradox: a review of the literature and the role food stamps may play. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1952–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drewnowski A, Specter S. Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:6–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones S, Jahns L, Laraia B, Haughton B. Lower risk of overweight in schoolaged food insecure girls who participate in food assistance. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:780–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker L. Obesity, Food Insecurity and the Federal Child Nutrition Programs: Understanding the Linkages. Washington, DC: Food Research and Action Center (FRAC); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdollahi M, Mohammadi F, Houshiar-Rad A, Ghaffarpur M, Ghodsi D, Kalantari N. Socio-economic differences in dietary patterns and nutrient intakes: the Comprehensive Study on household Food Consumption Patterns and Nutritional Status of I.R.Iran, 2001–2003. Ann Nutr Metab. 2005;49(supple 1):72. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohammadi F, Ghodsi D, Abdollahi M, Houshiar-Rad A, Ghaffarpur M, Kalantari N. Socio-economic status, dietary patterns and nutrient intakes in Iranian households: 2001–2003. Iranian Journal of Nutrition (MATA) 2005;1(2):24–30. [In Farsi] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pajouyan J. Comprehensive Study on Nutritional Practise and Food Security of Iranian Households. Tehran: Commercial Studies and Researches Foundation[In Farsi]; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scraton S, Flintoff A. Gender and sport: a reader. New York: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]