Abstract

Genomic selection patterns and hybrid performance influence the chance that crop (trans)genes can spread to wild relatives. We measured fitness(-related) traits in two different field environments employing two different crop–wild crosses of lettuce. We performed quantitative trait loci (QTL) analyses and estimated the fitness distribution of early- and late-generation hybrids. We detected consistent results across field sites and crosses for a fitness QTL at linkage group 7, where a selective advantage was conferred by the wild allele. Two fitness QTL were detected on linkage group 5 and 6, which were unique to one of the crop–wild crosses. Average hybrid fitness was lower than the fitness of the wild parent, but several hybrid lineages outperformed the wild parent, especially in a novel habitat for the wild type. In early-generation hybrids, this may partly be due to heterosis effects, whereas in late-generation hybrids transgressive segregation played a major role. The study of genomic selection patterns can identify crop genomic regions under negative selection across multiple environments and cultivar–wild crosses that might be applicable in transgene mitigation strategies. At the same time, results were cultivar-specific, so that a case-by-case environmental risk assessment is still necessary, decreasing its general applicability.

Keywords: crop–wild hybrids, genetically modified crops, genotype by environment interaction, Lactuca, Quantitative Trait Loci, risk assessment

Introduction

The chance of crop alleles to introgress into their wild relatives is highly dependent on genetic and environmental selection patterns (Barton 2001; Stewart et al. 2003). For crop alleles to become permanently established in the wild population after single hybridization events, hybrid genotypes should confer a selective advantage in a particular environment (Burke and Arnold 2001; Rieseberg et al. 2007). Introgression of crop genes into a recipient population starts with F1 hybrids, with equal contributions of crop and wild genomes, genome-wide heterozygosity, and strong linkage disequilibrium (LD). In subsequent generations, a range of new genotypes is formed as a result of recombination and segregation in meiosis and the creation of new individuals by outcrossing or selfing. However, since the genetic background changes rapidly in the first phases of the introgression process, selection patterns may differ between early- and late-generation hybrids, as well as among individual plants within a certain category of hybrids (Barton 2001). Such patterns that affect the outcome of hybridization are not only interesting from a theoretical point of view (Rieseberg et al. 2000; Burke and Arnold 2001) but are also of high interest to Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA). Specifically, to what extent genomic selection patterns can be generalized across different cultivars and whether the performance of hybrids differs between early- and late-generations and different environments (EFSA 2011).

The performance of crop–wild hybrids can differ depending on the cultivar and wild parental lines used to produce specific crosses. In experiments employing crop–wild hybrids from several crosses with different parental lines, variation was found in life history and fitness traits, such as germination, seed production and survival between different crossing populations in oilseed rape (Hauser et al. 1998), sunflower (Mercer et al. 2006) and sorghum (Muraya et al. 2012). These differences in fitness response might also imply that selection acts on different regions in the genome. Recently, Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) analysis on fitness characteristics measured in field trials has been used to study genomic selection patterns in crop–wild hybrids (Baack et al. 2008; Dechaine et al. 2009; Hartman et al. 2012), but little remains known of how differences in life history and fitness traits between different cultivar–wild-type crosses translate to differences in genomic selection patterns. With the production of high density integrated and consensus maps it becomes possible to compare QTL results between different cultivar–wild-type crosses (Hund et al. 2011; Swamy and Sarla 2011).

After a single hybridization event, several processes play a role: hitchhiking effects because of linkage drag, heterosis, epistasis and transgressive segregation interact to determine hybrid fitness (Stewart et al. 2003; Johansen-Morris and Latta 2006) and so influence the introgression chances of crop alleles. Epistasis is more thought to contribute to hybrid breakdown through the disruption of co-adapted gene complexes (Rieseberg et al. 2000), while heterosis and transgressive segregation can contribute to an increase in the performance of some hybrid lines relative to the wild parent (Burke and Arnold 2001). Hence, we focus on the latter processes in this study (but see Uwimana et al. (2012b) for a study on epistasis in lettuce) and we use two distinct hybrid generations: early generation backcross (BC) lines in which heterosis and transgression effects can occur and Recombinant Inbred Lines (RILs) with only transgressive effects.

Heterosis is most pronounced in early-generation hybrids, especially after hybridization between closely related species or inbred lines (Rieseberg et al. 2000), because of high levels of heterozygosity. Heterosis may be due to dominance (masking of deleterious alleles), overdominance (single-locus heterosis) and epistasis (enhanced performance of traits derived from different lineages due to non-additive interactions of QTL) effects (Rieseberg et al. 2000). It has been found many times in plants (Rhode and Cruzan 2005; Muraya et al. 2012), animals (Hedgecock et al. 1995) and insects (Bijlsma et al. 2010).

Transgressive phenotypes include hybrid plants that exceed the parental phenotype in a negative or a positive direction (Rieseberg et al. 2000). Transgressive phenotypes arise if parental species contain alleles with opposing effects, where some lines derive the positively contributing alleles from both parents and others derive the negatively contributing alleles, leading to hybrid genotypes that are more extreme than the parental lines (Lynch and Walsh 1998). In a review of 171 studies on segregating plant and animal hybrids, Rieseberg et al. (1999) showed that in 155 studies at least one transgressive trait was reported and that 44% of 1229 traits examined were transgressive. These studies show that both heterosis and transgressive segregation are widespread phenomena in hybridizing species (Rieseberg et al. 1999, 2003), suggesting that there is a high likelihood that at least some crop–wild hybrids have an increased fitness relative to the wild type in a given environment (Johansen-Morris and Latta 2006; Latta et al. 2007). Therefore, rather than estimating average hybrid fitness, it is necessary to view the entire fitness distribution of the hybrid lineages and identify how many individual hybrid lineages outperform the wild relative and when.

In addition to the potentially different response of hybrids from different parental lines, or from early- and late-generations, hybrid performance is also subject to Genotype × Environment (G × E) interactions (Barton 2001; Hails and Morley 2005). For example, several QTL studies that compared hybrid performance between greenhouse and field environments have shown that different traits and loci were favoured because of different selection pressures (Martin et al. 2006; Latta et al. 2007; Hartman et al. 2012). Similarly, hybrid fitness selection patterns differ across different natural environments (Weinig et al. 2003) and as a consequence of varying stresses, such as competition (Mercer et al. 2007). This suggests that hybrid fitness might be weakly correlated across divergent environments (Latta et al. 2007) and that as a result of these G × E interactions different hybrid lineages, and consequently alleles, might be selected for in different environments (Mercer et al. 2007). Moreover, hybridization between two wild parental species can lead to the colonization of new habitats previously unavailable to either of the parental species (Rieseberg et al. 2007). Therefore, the hybrid fitness distributions of different types of crosses and generations should also be considered in different environments, including the original wild habitat and novel environments, as we have done in this study.

In this study, we used progeny from different crosses between the crop lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) and the wild-type prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola L.). These species are fully cross-compatible and interfertile without any crossing barriers (Koopman et al. 2001). A recent study suggested that a substantial part of wild L. serriola plants in Europe (7%) show evidence of previous introgression of alleles from L. sativa (Uwimana et al. 2012a). In addition, it was demonstrated that compared with the wild parent up to four hybrid generations had higher average germination and survival rates in the field (Hooftman et al. 2005, 2007, 2009). Moreover, part of the crop genome was selectively advantageous leading to skewed crop–wild allele distributions (Hooftman et al. 2011). Although it is often assumed that crop alleles confer negative fitness effects in the wild habitat (Stewart et al. 2003), this suggests that in lettuce parts of the crop genomic background contribute to higher hybrid fitness and, therefore, potentially to the transfer of crop alleles to the wild population.

As different generations, early BC lines as well as late-generation RILs were used, originating from different parental lines. We employed these hybrid lineages and their parents in a location with sandy soil, which is similar to the natural habitat in which L. serriola occurs, and one with clay soil, which can be considered as a novel habitat given the current distribution of L. serriola (Hooftman et al. 2006). In a previous study, we identified two genomic regions under selection in the RILs, one where the crop genomic background was selectively beneficial and one where the wild genomic background was selectively beneficial (Hartman et al. 2012). In this study, we extend this analysis to the comparison with BC lines employed in the same experiment as the RILs and, in addition, studied the performance of individual hybrid lineages for both crossing types. This design allowed us to study similarities and differences in genomic selection patterns between different lettuce cultivar–wild crosses, hybrid performance in early- and late-generation hybrids and environmental influence on hybrid fitness distributions. We address these specific questions: (i) Which crop genomic regions are under positive or negative selection and are these similar or different between the BC and RIL crossing populations? (ii) Do the crop–wild hybrid populations differ in their fitness distribution and do they include hybrid lineages that perform better than the wild parent? (iii) Are there environment specific effects on the fitness distributions? In particular, is there an indication that introgression is more likely to occur in a novel habitat compared to the original habitat of the wild relative? Finally, we discuss the likelihood of crop gene transfer to the wild relative and the implications for ERA procedures.

Material and methods

Plant material

In this study, two different lettuce crop–wild crosses were employed. We used 98 lines of an existing RIL population (selfed for nine generations) derived from a cross between the cultivar L. sativa cv. Salinas (Crisphead) and Californian L. serriola (UC96US23; Johnson et al. 2000; Argyris et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2007). In addition, we used 98 backcross lines selfed for one generation (BC1S1) from a cross between the cultivar L. sativa cv. Dynamite (Butterhead) and a L. serriola collected near the town of Eys, the Netherlands (designated cont83 in Van de Wiel et al. (2010); further referred to as L. serriola (Eys).

Latuca sativa was used as the pollen donor to mimic a hybridization event due to pollen flow from the crop to a neighbouring wild population. The F1 hybrid plant was subsequently backcrossed to the wild-type, creating a BC1 generation and each BC1 was then selfed to create a BC1S1 population. Crossing followed the protocols by (Nagata 1992) and (Ryder 1999), and is described in detail in Hooftman et al. (2005). Note that BC1 individuals were genotyped, whereas the BC1S1 were used in the experiments (see below).

Both wild L. serriola parents used in the crosses have leaves that are long and serrated, and contain a white latex substance. Plants develop up to 2 mm long spines on downside leaf midribs as well as on the base of the main stem. Lactuca serriola develops a rosette and flowers in July–August with many reproductive side shoots in the inflorescence and at the base of the plant. Capitula (flower heads) produce approximately 15–20 florets that develop into brown single-seeded achenes (further referred to as seeds). When seeds are ripe the involucral bracts become reflexed. Lactuca serriola occurs predominantly in ruderal sites, for example, along roads, railways and construction sites. This species is an annual that survives the winter mainly as seed, but also occasionally as small rosettes (Y. Hartman, field observation). Lettuce mainly reproduces by selfing, but research has shown that up to 5% outcrossing rates can be reached via insect pollination (D'Andrea et al. 2008; Giannino et al. 2008).

In contrast, the crop-types of L. sativa used in this study do not have spines and leaves are broad instead of serrated and do not contain latex. Plants develop a compact head instead of a rosette and do not have reproductive side shoots at the base of the stem. The cultivar group of Crisphead typically develops a very dense head (de Vries 1997) and develops brown seeds, whereas the Butterheads develop a relatively loose head and white seeds. Both cultivars have erect involucral bracts when seeds are ripe, most likely selected for to prevent seed shattering (de Vries 1997).

Experimental set-up and analysis

This study was conducted in two contrasting field sites. The soil at the first site, located in Sijbekarspel (SB), the Netherlands (N52°42′, E04°58′), consisted of nutrient rich and water retaining clay similar to agricultural conditions. The second site, located in Wageningen (WG), the Netherlands (N51°59′, E05°39′), was similar to the wild habitat with dry, nutrient-poor and sandy soil. The weather conditions during the experiment were not different between the two sites (see Table S1).

For a detailed description of the experimental set-up see Hartman et al. (2012). In short, both sites consisted of 12 blocks, each with all 98 RILs, 98 BC1 families and the parental lines. Blocks contained 200 squares (40 × 40 cm) to which lines were randomly assigned, leading to a total of 4800 squares. We started the experiment with 30 seeds sown in each square and followed plants during the entire life cycle. Squares were thinned leaving one individual to reach the adult stage. This means that the data consisted of fitness estimates for all 4800 plants (i.e. including survival) and on average measurements on 4221 plants for different phenotypic traits.

Statistical and QTL analysis were performed on data of traits measured in the field. On the basis of the fitness QTLs found, we could distinguish ‘fitness QTL genotypes’ in both RILs and BCs, and compared their fitness distributions and the influence of the proportion crop genome.

Traits measured

During the experiment, from May until October, we measured the following traits related to fitness (Table 1). Germination was measured 4 weeks after sowing and biomass measurements were done 7 weeks after sowing. Sites were visited daily to record the flowering date. At the seed set stage, the branches of the main inflorescence and basal reproductive side shoots were counted. In addition, we counted seeds from ten collected capitula and estimated the average number of seeds per capitulum. The number of shoots and branches was used to estimate the total number of capitula (See Hooftman et al. 2005 and Data S1). Subsequently, seed output was estimated by multiplying the average number of seeds per capitulum with the total number of capitula. We scored survival as a binary trait with 1 for survival until seed production and 0 for individuals that either died before seed set or did not complete their life cycle before the end of the growing season. We divided the number of seed-producing plants per line by twelve to calculate the survival rate. The final trait, seeds produced per seed sown (SPSS) was calculated using the following formula:

Table 1.

Traits studied in a recombinant inbred lines (RILs) population of a Lactuca sativa cv. Salinas × Lactuca serriola (UC96US23) cross and in backcross (BC1S1) families of a L. sativa cv. Dynamite × L. serriola (Eys) cross

| Plant stage | Trait | Abbreviation | Measurement and estimation method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seedling | Germination rate | GM | Total number of seedlings divided by 30 seeds sown; seedlings counted 4 weeks after sowing; arcsine-square root transformation |

| Rosette | Biomass (g) | BM | Average dry weight of two rosettes; log transformation |

| Flowering | Days to first flower (day) | FLD | Number of days between sowing and the appearance of the first flower; log transformation |

| Seed set | Number of basal reproductive side shoots (count) | SHN | Number of basal reproductive side shoots which produced flowers, flower buds or seed heads; log transformation |

| Number of branches main inflorescence (count) | BRN | Number of branches of the main inflorescence; log transformation | |

| Number of seeds per capitulum | SDC | Average number of seeds from ten collected capitula; no transformation necessary | |

| Total number of capitula | TC | Total number of capitula, estimation following Hooftman et al. (2005, eqn 1); log transformation | |

| Seed output | SDO | Total seed production, estimation following Hooftman et al. (2005); square root transformation | |

| Survival rate | SUR | Number of RIL or BC plants with seed production divided by twelve; arcsine-square root transformation | |

| Seeds produced per seed sown | SPSS | Number of seeds produced per seed sown, estimated by multiplying seed output, survival and germination rate; square root transformation |

| () |

Of all traits, SPSS is the closest estimate of life cycle fitness and therefore referred to as the ‘main fitness trait’. The calculation of SPSS is slightly different than in Hartman et al. (2012), where we used average survival rate per line to calculate SPSS for each square, whereas here we used survival (e.g. either 0 or 1).

Statistical analysis

We used PASW Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc 2009) for the statistical analyses. To improve normal distributions all traits were transformed, except for number of seeds per capitulum because this trait already had a normal distribution. Proportional data, such as survival and germination rates, were arcsine-square-root-transformed. Other traits were log-transformed (total number of capitula, number of branches, number of reproductive basal shoots and biomass) or square-root-transformed (SPSS and seed output). For each trait, the mean, standard deviation and heritability values were estimated. In addition, we also calculated the selection differentials for each trait by taking the covariance between the relative fitness and trait values (both with 12 data points per RIL or BC line). The relative fitness was calculated by dividing SPSS of each plant by the overall mean SPSS for a site.

We used heritability values to assess how much of the variation was due to genetic differences. Broad-sense heritability values (H2) were estimated as the proportion of the total variance accounted for by the genetic variance using the formula:

With Vg is the genetic variance and Ve is the environmental variance. Vg and Ve were inferred from between- and within-line variance components extracted with procedure VARCOMP (SPSS Inc 2009). Heritability values of family means ( ) were estimated using the following formula (Chahal and Gosal 2002):

) were estimated using the following formula (Chahal and Gosal 2002):

Where n is the average number of individuals per line measured for a certain trait (Table 2). The latter value indicates how well the family mean estimate resembles the true genetic value, given the number of replicates used, and is therefore important for the power of the QTL analyses.

Table 2.

Estimated values of the mean and standard deviation, the broad-sense (H2) and family-mean ( ) heritability, and the selection differentials for backcross (BC1S1) families, recombinant inbred lines and the parent lines

) heritability, and the selection differentials for backcross (BC1S1) families, recombinant inbred lines and the parent lines

| RIL-parents | BC1S1-parents | RILs | BC1S1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. sativa cv. Salinas | L. serriola (UC96US23) | L. sativa cv. Dynamite | L. serriola (Eys) | Selection differential | Selection differential | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Trait | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Broad sense H2 (%) | Family mean  (%) (%) |

Absolute | Standar-dized | Mean | SD | n | Broad sense H2 (%) | Family mean (%) (%) |

Absolute | Standar-dized |

| Sijbekarspel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GM (%) | 60.8 | 18.9 | 12.0 | 25.3 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 62.2 | 13.4 | 12.0 | 48.3 | 17.3 | 12.0 | 52.8 | 14.6 | 12.0 | 27.9 | 82.3 | 4.6 | 0.316** | 51.1 | 13.8 | 12.0 | 27.6 | 82.1 | 5.1 | 0.370** |

| BM (g) | 1.083 | 0.586 | 12.0 | 0.542 | 0.334 | 11.0 | 1.011 | 0.384 | 12.0 | 0.762 | 0.315 | 12.0 | 0.681 | 0.335 | 11.9 | 14.1 | 66.2 | 0.037 | 0.112* | 0.856 | 0.422 | 12.0 | 6.2 | 44.1 | 0.011 | 0.026 |

| FLD (day) | 115.0 | – | 1.0 | 93.8 | 3.1 | 12.0 | 127.4 | 8.2 | 5.0 | 115.2 | 14.4 | 10.0 | 94.3 | 4.8 | 10.2 | 89.5 | 98.9 | −6.9 | −1.454** | 107.8 | 15.9 | 10.1 | 18.9 | 70.2 | −9.1 | −0.569** |

| SHN | – | – | 0.0 | 4.2 | 2.1 | 12.0 | – | – | 0.0 | 10.3 | 3.3 | 6.0 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 9.9 | 50.5 | 91.0 | 1.4 | 0.717** | 11.1 | 3.9 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 42.9 | 1.3 | 0.334** |

| BRN | – | – | 0.0 | 36.3 | 8.0 | 12.0 | – | – | 0.0 | 31.0 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 28.3 | 5.2 | 10.2 | 14.1 | 62.7 | 4.1 | 0.793** | 28.6 | 6.5 | 8.7 | 12.2 | 54.7 | 1.3 | 0.203** |

| SDC | – | – | 0.0 | 10.0 | 3.4 | 12.0 | – | – | 0.0 | 13.5 | 3.3 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 10.0 | 75.8 | 96.9 | 6.8 | 2.773** | 12.2 | 3.8 | 8.7 | 13.4 | 57.4 | 2.2 | 0.571** |

| TC | – | – | 0.0 | 2566 | 492 | 12.0 | – | – | 0.0 | 3392 | 602 | 6.0 | 2011 | 421 | 10.2 | 62.0 | 94.3 | 462 | 1.097** | 3411 | 746 | 8.7 | 12.3 | 54.9 | 296 | 0.397** |

| SDO | – | – | 0.0 | 26 034 | 11 445 | 12.0 | – | – | 0.0 | 44 961 | 9588 | 6.0 | 14 411 | 6179 | 10.0 | 73.6 | 96.5 | 18 592 | 3.009** | 41 888 | 16 703 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 41.8 | 11 057 | 0.662** |

| SUR (%) | 0 | – | 12.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0 | – | 12.0 | 50.0 | 52.2 | 12.0 | 56.9 | 14.6 | 12.0 | 76.4 | 97.5 | 43.2 | 2.960** | 72.4 | 38.1 | 12.0 | 13.9 | 65.9 | 27.7 | 0.726** |

| SPSS | 0 | – | 12.0 | 6921 | 4757 | 12.0 | 0 | – | 12.0 | 10 817 | 14 068 | 12.0 | 4700 | 2771 | 12.0 | 74.7 | 97.5 | 15 337 | 12 666 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 65.1 | ||||

| Wageningen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GM (%) | 72.8 | 21.2 | 12.0 | 35.0 | 14.1 | 12.0 | 82.2 | 10.3 | 12.0 | 66.1 | 14.1 | 12.0 | 66.4 | 18.0 | 12.0 | 24.4 | 79.5 | 7.9 | 0.437** | 63.0 | 15.5 | 12.0 | 30.2 | 83.9 | 5.8 | 0.374** |

| BM (g) | 1.543 | 0.818 | 12.0 | 0.955 | 0.593 | 12.0 | 1.336 | 0.453 | 12.0 | 0.991 | 0.515 | 12.0 | 1.183 | 0.554 | 11.9 | 16.5 | 70.2 | 0.076 | 0.137** | 1.236 | 0.600 | 12.0 | 13.5 | 65.1 | −0.004 | −0.006 |

| FLD (day) | 104.0 | – | 1.0 | 82.1 | 3.3 | 12.0 | 122.5 | 7.8 | 4.0 | 103.4 | 11.4 | 12.0 | 91.4 | 4.5 | 10.7 | 89.5 | 98.9 | −6.5 | −1.445** | 95.8 | 13.0 | 10.9 | 14.1 | 64.2 | −5.5 | −0.423** |

| SHN | – | – | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 12.0 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | 10.1 | 2.4 | 11.0 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 10.1 | 54.6 | 92.4 | 1.2 | 0.935** | 8.4 | 2.8 | 9.4 | 12.9 | 58.3 | 0.7 | 0.261** |

| BRN | – | – | 0.0 | 41.8 | 8.2 | 12.0 | 25.0 | – | 1.0 | 28.8 | 9.4 | 11.0 | 29.1 | 5.5 | 10.1 | 16.5 | 66.6 | 4.8 | 0.869** | 27.7 | 5.7 | 9.4 | 7.2 | 42.1 | 1.0 | 0.174** |

| SDC | – | – | 0.0 | 19.1 | 3.1 | 12.0 | 12.7 | – | 1.0 | 17.9 | 1.7 | 11.0 | 12.6 | 2.6 | 9.6 | 64.0 | 94.5 | 3.3 | 1.251** | 15.9 | 2.7 | 9.4 | 18.3 | 67.8 | 0.9 | 0.338** |

| TC | – | – | 0.0 | 2333 | 433 | 12.0 | 4 | – | 1.0 | 3239 | 687 | 11.0 | 1887 | 351 | 10.1 | 74.9 | 96.8 | 453 | 1.289** | 2888 | 573 | 9.4 | 13.9 | 60.2 | 179 | 0.312** |

| SDO | – | – | 0.0 | 45 171 | 11 869 | 12.0 | 52 | – | 1.0 | 57 892 | 13 251 | 11.0 | 23 631 | 6865 | 9.7 | 68.1 | 95.4 | 13 866 | 2.020** | 45 947 | 12 436 | 9.4 | 15.0 | 62.5 | 5557 | 0.447** |

| SUR (%) | 0.0 | – | 12.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 8.3 | 28.9 | 12.0 | 91.7 | 28.9 | 12.0 | 57.1 | 12.9 | 12.0 | 80.0 | 98.0 | 43.0 | 3.325** | 80.1 | 32.0 | 12.0 | 13.8 | 65.7 | 19.9 | 0.623** |

| SPSS | 0 | – | 12.0 | 15 743 | 7638 | 12.0 | 3.6 | 12.5 | 12.0 | 35 027 | 15 497 | 12.0 | 9132 | 4984 | 12.0 | 73.9 | 97.4 | 22 688 | 14 647 | 12.0 | 13.3 | 66.7 | ||||

RIL, Recombinant Inbred Lines; n, average number of individuals per line or family; SPSS, seeds produced per seed sown. Abbreviations are listed in Table 1.

Significant at 0.05 level.

Significant at 0.01 level.

Quantitative trait loci analysis

For RILs, the genetic map employed consisted of 1513 predominantly AFLP and EST derived SNP markers (http://cgpdb.ucdavis.edu/GeneticMapViewer/display/; map version: RIL_MAR_2007_ratio; Johnson et al. 2000; Argyris et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2007); both map and markers were developed by the Compositae Genome Project website (http://compgenomics.ucdavis.edu).

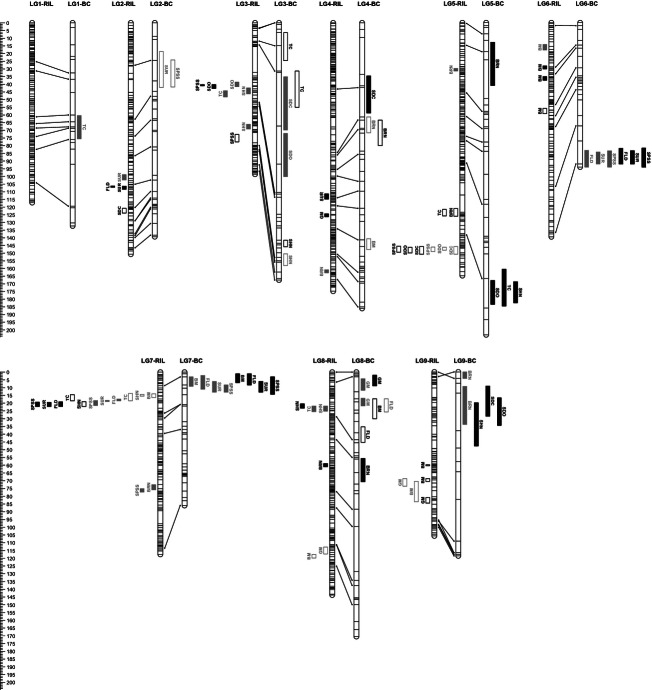

For BC lines, the genetic map consisted of 347 SNP markers distributed over nine linkage groups (described in detail in Uwimana et al. 2012b). These were selected from 1083 SNPs, developed by the Compositae Genome Project (http://compgenomics.ucdavis.edu/compositae_SNP.php) from disease resistance and developmental genes in lettuce, using a customized Illumina GoldenGate array with markers polymorphic between the parent lines. Note that BC1 plants were genotyped and that their offspring (BC1S1) was used in the experiments. We conducted the QTL analyses in QTL Cartographer (version 2.5.008, Wang et al. 2010). RIL and BC1S1 data were analysed separately. We used Composite Interval Mapping (CIM) testing at 2 cm intervals and a stepwise regression method (forward and backward) with five background cofactors and a 10 cm window. Permutation tests were used to estimate a significance threshold of α = 0.05 for QTL using 1000 iterations (Doerge and Churchill 1996). Additive effects and one-LOD support intervals were obtained from the CIM results. MapChart 2.2 was used to draw the linkage map and QTL results (Voorrips 2002). The marker order of LG1, 3, 4, 7 and 8 of the BC map was reversed to be able to compare RIL and BC QTL; 80 markers were similar between the RIL and BC map (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Positions of quantitative trait loci (QTL) in backcross (BC1S1) families of a Lactuca sativa cv. Dynamite × L. serriola (Eys) cross and a recombinant inbred lines (RIL) population of a L. sativa cv. Salinas × L. serriola (UC96US23) cross using composite interval mapping. Map distances (cm) are located on the left side. The same linkage groups of RIL and BC map are shown next to each other; markers are shown as horizontal lines. Linkage group names are shown at the top and dotted lines between linkage group bars indicate similar markers. RIL QTL are shown on the left side of linkage groups by black or grey bars, whereas BC QTL are shown on the right. Black bars indicate Wageningen QTL and grey bars indicate Sijbekarspel QTL. When the crop genomic background (L. sativa) gives a selective advantage (derived from the selection differentials shown in Table 2) the QTL is shown as an open bar; when the wild genomic background (L. serriola) gives a selective advantage the QTL is shown as a filled bar. The length of QTL bars is determined by the one-LOD confidence interval. Abbreviations are listed in Table 1.

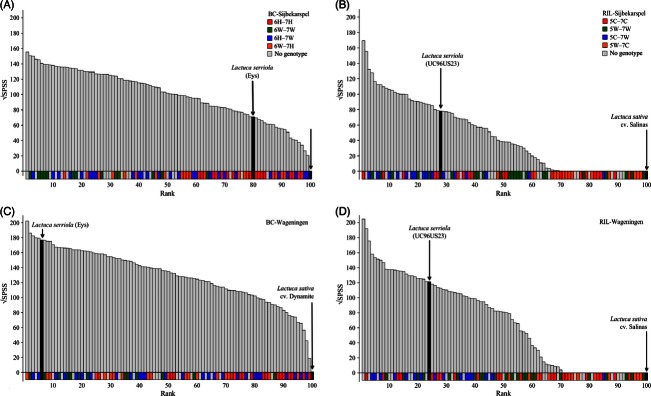

Fitness distributions

To visualize variation in fitness for both sites, we ranked all 98 BC or RIL and parental lines based on the estimated average SPSS and plotted the estimated average SPSS of lines against their rank. In addition, we visualized the influence of major fitness QTL on the fitness distributions. We focussed specifically on the genomic regions where BC and RIL fitness QTL co-localized across sites. Lines that we could unequivocally assign to a certain ‘fitness QTL genotype’ were colour-coded. Coloured lines had no missing data and all flanking markers were of one parental background. Colour-codes indicated if fitness QTL contained alleles from the crop or the wild parent or a combination of both parental lines. We also estimated the average rank per fitness QTL genotype indicating if a certain fitness QTL genotype had an average high or low rank.

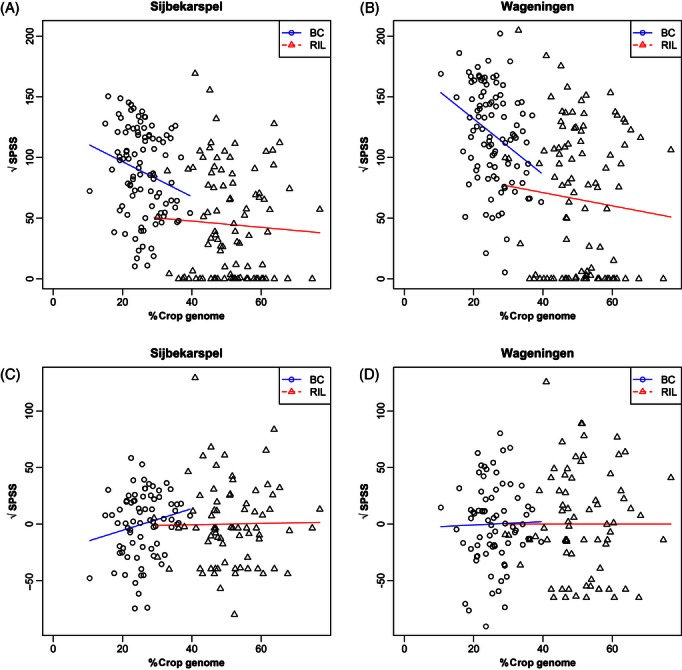

Influence of the proportion crop genome

To visualize the influence of the amount of crop genome on fitness, we plotted the estimated average SPSS of BC1 families and RILs against an estimate of the percentage of crop genome. This estimate was based on counting markers as coming from the crop or wild relative (missing data were excluded). The analysis was done for both sites and crossing types separately and included all 98 RIL or BC1 families and all parental lines.

First, we used a univariate linear regression to estimate the overall relationship between SPSS and the percentage of crop genome in R (version 2.14.0; R Development Core Team 2011). Second, we repeated this analysis, while excluding the effect of the two major fitness QTL by adding these as covariates (based on the genotype data that were also used for the fitness distributions), therefore estimating the relationship between the residual variation in SPSS and the percentage of crop genome. In this second analysis, we omitted genotypes for which the presence of the fitness QTL was ambiguous, either due to missing markers or a recombination event in the QTL interval. In addition, we estimated the average amount of crop genome per fitness QTL genotype.

Results

General survival

Survival of plants was comparable between sites. For RILs, 57.1% of plants survived until reproduction at WG and 56.9% survived at SB (Hartman et al. 2012). A higher percentage of BC individuals survived until reproduction at both sites; 80.1% for WG and 72.4% for SB.

Parental lines

The main difference between the cultivars and wild parental lines is that most crop individuals died before seed production, whereas the majority of wild-type individuals survived and produced seeds (Table 2). In both SB and WG, only one L. sativa cv. Salinas individual survived until flower production, but died before reproductive characters could be recorded. Similarly, only one L. sativa cv. Dynamite individual survived until flower production in SB; in WG, four individuals survived until flowering but only one of them produced seeds in four capitula. Other trends are that crop cultivars had higher germination rates, higher biomass production and flowered later compared with the wild parental lines of the same cross (Table 2). In addition, all parental lines developed faster and flowered earlier in WG compared to SB.

Heritability values and selection differentials

Heritability values patterns were more variable among BC lines than among the RILs, consistent with the larger genetic variation within and among these lines. For BC lines, biomass, number of reproductive basal shoots and seed output had the lowest heritability values in SB, whereas in WG, number of reproductive basal shoots and branch number had the lowest heritability values. At both sites, germination showed the highest broad-sense and family-mean heritability. For RILs, branch number, biomass and germination rate showed the lowest broad-sense and family-mean heritability values, whereas days until first flower showed the highest values at both sites.

For BC lines, broad-sense heritability values varied from 6.2% to 30.2% and family-mean heritability values varied from 41.8% to 83.9%. For RILs, these varied between 14.1% and 89.5% and 62.7% and 98.9%, for broad-sense and family-mean heritabilities respectively (Table 2), indicating that the replication level was adequate, given the environmental variation under field conditions.

The majority of selection differentials showed significant trends (Table 2), except for BC1S1 biomass in SB and WG. Across sites and crosses, all selection differentials indicated that higher values were favoured, with the exception of days to first flower. For this trait lower values were favoured, namely 6–7 days earlier flowering for RILs and 5–9 days for BC1 families.

Quantitative trait loci analysis

For the BC1 families, we detected a total of 43 QTL for ten fitness and fitness-related traits distributed over all nine linkage groups (Table 3; Fig. 1). The Phenotypic Variation Explained (PVE) ranged from 6.4% to 42.8%. One to three QTL were detected per trait (mean 2.2) and 1-LOD support intervals varied between 4.2 and 34.7 cm (mean 13.7 cm). When the two field sites are combined for all ten traits, nine QTL were detected at both sites; the remaining 25 QTL were unique for one of the sites. QTL results of the RIL population are summarized in Fig. 1 and are described in more detail in Hartman et al. (2012, see Table S2). In short, a total of 49 QTL was detected and when the two field sites are combined, eleven QTL were found at both sites, whereas 27 QTL were unique for one of the sites.

Table 3.

Positions of quantitative trait loci (QTL) in backcross (BC1S1) families of a Lactuca sativa cv. Dynamite × Lactuca serriola (Eys) cross using composite interval mapping. Quantitative trait loci results of the recombinant inbred lines population from a L. sativa cv. Salinas × L. serriola (UC96US23) cross are described in detail in Hartman et al. (2012; but see Table S2 for SPSS QTL). A positive additive effect indicates that crop genomic background (L. sativa) causes higher trait values, whereas a negative additive effect indicates that the wild genomic background (L. serriola) causes higher values. QTL on the same line have peak values within 5 cm

| Sijbekarspel | Wageningen | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG | Trait | Position | One-LOD interval | Additive effect | PVE (%) | LOD | Position | One-LOD interval | Additive effect | PVE (%) | LOD |

| 1 | TC | 70.7 | 60.4–75.5 | −0.04 | 11.8 | 3.2 | |||||

| 2 | SUR | 30.5 | 18.7–42.1 | 0.15 | 6.4 | 3.0 | |||||

| SPSS | 32.5 | 24.1–41.8 | 20.92 | 9.4 | 3.0 | ||||||

| 3 | TC | 19.4 | 6.4–24.6 | 0.04 | 13.3 | 3.9 | |||||

| TC | 35.2 | 31.4–55.0 | 0.03 | 10.9 | 3.2 | ||||||

| SDC | 51.2 | 35.1–69.8 | −1.93 | 20.2 | 4.7 | ||||||

| SDO | 84.0 | 72.0–100.2 | −19.63 | 19.1 | 4.5 | ||||||

| SHN | 144.6 | 141.6–145.8 | 0.07 | 12.8 | 4.2 | ||||||

| SHN | 155.9 | 150.4–158.1 | 0.21 | 19.5 | 4.9 | ||||||

| 4 | SDC | 46.2 | 34.6–58.7 | −1.19 | 12.7 | 4.0 | |||||

| BRN | 63.3 | 61.3–71.6 | 0.04 | 10.4 | 3.5 | 68.6 | 63.3–80.0 | 0.03 | 8.5 | 2.9 | |

| BM | 141.3 | 140.6–147.7 | −0.02 | 10.1 | 3.6 | ||||||

| 5 | BRN | 27.8 | 12.8–41.2 | −0.03 | 10.6 | 3.1 | |||||

| TC | 175.2 | 161.8–185.9 | −0.04 | 16.1 | 3.6 | ||||||

| SDO | 177.2 | 169.2–184.8 | −14.97 | 18.7 | 4.7 | ||||||

| SHN | 177.2 | 170.0–183.8 | −0.11 | 31.2 | 7.6 | ||||||

| 6 | SUR | 91.6 | 84.9–92.7 | −0.36 | 37.7 | 12.7 | 89.6 | 84.0–92.7 | −0.39 | 42.8 | 14.2 |

| SPSS | 92.7 | 84.1–94.7 | −26.80 | 16.3 | 5.7 | 92.7 | 82.3–94.7 | −30.54 | 18.4 | 5.9 | |

| FLD | 92.7 | 83.8–94.7 | 0.03 | 13.0 | 4.5 | 89.6 | 82.5–92.7 | 0.03 | 27.3 | 8.0 | |

| 7 | BM | 6.3 | 3.1–9.1 | 0.04 | 24.3 | 7.5 | 3.1 | 1.1–6.8 | 0.06 | 24.5 | 7.5 |

| FLD | 6.3 | 2.2–11.0 | 0.03 | 19.0 | 6.0 | 3.1 | 1.1–8.3 | 0.02 | 8.8 | 3.1 | |

| SPSS | 10.4 | 8.3–12.9 | −30.58 | 20.6 | 6.9 | 10.4 | 3.1–14.3 | −20.51 | 8.5 | 3.0 | |

| SUR | 10.4 | 6.0–12.9 | −0.30 | 26.0 | 9.7 | 10.4 | 6.0–12.9 | −0.31 | 26.5 | 10.2 | |

| 8 | GM | 4.6 | 4.3–11.7 | −0.09 | 17.8 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 2.0–8.8 | −0.09 | 10.0 | 2.7 |

| GM | 19.2 | 16.9–21.8 | −0.10 | 22.4 | 6.1 | ||||||

| FLD | 19.2 | 17.2–25.7 | −0.03 | 14.8 | 5.0 | ||||||

| BM | 24.5 | 17.2–30.0 | −0.04 | 11.8 | 4.8 | ||||||

| FLD | 41.5 | 35.3–45.3 | −0.02 | 11.9 | 4.0 | ||||||

| BRN | 62.7 | 55.7–70.6 | −0.03 | 13.9 | 4.4 | ||||||

| 9 | BRN | 0.00 | 0.0–4.2 | −0.04 | 10.9 | 3.2 | |||||

| SDC | 15.9 | 9.3–28.8 | −1.44 | 17.9 | 5.8 | ||||||

| BRN | 19.9 | 9.4–34.1 | −0.06 | 19.7 | 5.3 | ||||||

| SDO | 25.9 | 16.9–34.8 | −17.79 | 26.5 | 6.5 | ||||||

| SHN | 33.9 | 20.1–48.2 | −0.06 | 11.8 | 3.2 | ||||||

PVE, Percentage Variation Explained; SPSS, seeds produced per seed sown; Abbreviations are listed in Table 1.

The comparison between RIL and BC QTL fitness clusters shows similarities but also differences (Fig. 1). For both crosses, there were two genomic regions where several QTL clustered including QTL for SPSS, the main fitness QTL. For the BC1, these regions were located at LG6 (bottom) and at LG7 (top, Fig. 1). The same QTL are found for SB and WG at these genomic locations and in both cases selection differentials indicated that the selective advantage was conferred by the wild allele for these QTL. At LG6 and LG7, the wild genomic background increased SPSS and survival rate and reduced days until first flower. At LG7, additional QTL were detected for biomass and again a selective advantage was conferred by the wild genomic background, increasing biomass.

For the RILs, a fitness cluster was found across sites at the bottom of LG5, whereas a second fitness cluster was situated at LG7 (Hartman et al. 2012), overlapping the cluster found for the BC population. At LG5, QTL for seeds per seed sown, seed output and seeds per capitulum were detected and a selective advantage was conferred by the crop allele (Fig. 1). This region corresponded with BC QTL found for seed output, shoot number and total capitula, but in contrast to the RIL QTL, no seeds per seed sown QTL was found and here the selective advantage was conferred by the wild rather than the crop allele. At LG7 and similar to BC results, a selective advantage was conferred by the wild allele QTL for SPSS, survival rate until seed set, and days to first flower, indicating that both crop varieties contained gene(s) for delayed reproduction. Additional RIL QTL found were total capitula, shoot number and biomass, and for these traits a selective advantage was conferred by the crop allele.

Fitness distributions

Fitness distributions of RIL and BC crossing populations differed considerably. All BC lines had some seed output, whereas approximately 30% of RILs produced no seeds in SB and WG (Fig. 2). They either died before seed set or did not complete their life cycle before the end of the growing season. For RILs, the proportion of lines that performed better than the wild parent was comparable across sites, with 27% in SB and 23% in WG. For BC lines there was a considerable difference, with 79% of lines performing better than the wild parent in SB, whereas only 5% performed better in WG.

Figure 2.

Fitness distributions across lines for (A) backcross (BC1S1) families in Sijbekarspel (SB), (B) recombinant inbred lines (RILs) in SB, (C) BC1S1 families in Wageningen (WG) and (D) RILs in WG. Each bar represents one line. Lines are ranked based on the average Seeds Produced per Seed Sown. Coloured squares below the x-axis indicate the genotype for genomic fitness regions on LG6 and 7 for BC lines, and LG5 and 7 for RILs; for genotype notation, see Table 4. Black squares indicate parent lines and grey squares indicate lines for which the genotype remains unknown.

Given the QTL fitness regions, BC lines with a wild genomic background for LG6 and 7 (6W–7W) were expected to have the highest seed yield, whereas the opposite combination (6H–7H; H indicating that BC1 genotypes were heterozygous for these loci) should have the lowest seed yields. The 6W–7W lines (green bars) are indeed situated at the high-end of the fitness distributions, whereas the 6H–7H lines (red bars) are situated at the low-end side (Fig. 2). This is reflected in the average ranks of 24.0 out of 100 in SB and 30.5 in WG for 6W–7W lines, and 78.6 in SB and 77.9 in WG for 6H–7H lines (Table 4).

Table 4.

Average rank and amount of crop genome of four genotypes (based on QTL of the main fitness trait seeds per seed sown) across 98 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) or backcross (BC1S1) families

| Average rank | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Sijbekarspel | Wageningen | % crop genome | No. of lines |

| BC1S1 families | ||||

| 6H–7H | 78.6 | 77.9 | 31.0 | 16 |

| 6W–7W | 24.0 | 30.5 | 21.0 | 13 |

| 6H–7W | 51.9 | 52.7 | 25.1 | 27 |

| 6W–7H | 56.9 | 46.9 | 25.8 | 20 |

| No genotype | 34.6 | 42.7 | 25.4 | 22 |

| RILs | ||||

| 5C–7C | 52.9 | 51.7 | 52.1 | 21 |

| 5W–7W | 51.3 | 53.1 | 51.0 | 23 |

| 5C–7W | 27.6 | 28.9 | 50.2 | 16 |

| 5W–7C | 76.5 | 73.1 | 52.0 | 13 |

| No genotype | 47.8 | 48.2 | 49.8 | 25 |

C, homozygous crop allele; W, homozygous wild allele; H, heterozygous crop and wild allele; QLT, quantitative trait loci.

For RILs, letters indicate genomic fitness regions on LG5 and 7 and for BC lines, letters indicate genomic fitness regions on LG6 and 7. For example, 5C–7C indicates crop genotype for the identified QTL on both LG5 and LG7; lines without sufficient information are joined into ‘No genotype’. No. of lines = number of BC or RIL lines in each category (each line with 12 replicates per site). % crop genome = average% of markers derived from the crop parent (BC1 or RIL).

Recombinant Inbred Lines with the crop genomic background for LG5 and the wild parental background for LG7 (5C–7W) were expected to have the highest fitness. Lines with this fitness QTL genotype (blue bars) are indeed mostly located at the high-end of the fitness distribution (Fig. 2) and had the highest average rank at both sites (27.6 of 100 in SB and 28.9 in WG, Table 4). RILs with the opposite combination, 5W–7C (orange bars), mainly situated at the low-end of the fitness distribution and had the lowest average rank of 76.5 in SB and 73.1 in WG.

These QTL fitness regions do not explain all variation of the fitness distributions as seen by the mixed distribution of the coloured bars (Fig. 2). The PVE of the QTL for seed production (SPSS) reflects the unexplained variation. The combined PVE for BC fitness QTL was approximately 27% (WG) to 37% (SB), and for RIL fitness QTL approximately 30% at both sites, implying that part of the variation went undetected.

Influence of the proportion crop genome

The average amount of crop genome was 23.7% for the BC1 lines, ranging from 10.5% to 39.5% (Fig. 3). For RILs, the average was 50.9%, ranging from 29.1% to 76.9%. There was a large spread in SPSS for both BC1S1 families and RILs that had approximately the same amount of crop genome (Fig. 3A,B). Consequently, for BC1S1 families only 3% (SB) to 7% (WG) was explained by the univariate linear regressions. P-values were significant (SB: R2 = 0.03, P < 0.05, df = 96; WG: R2 = 0.07, P < 0.01, df = 96). The estimated slopes of the linear regression were quite steep, with an increase in crop genome from 20% to 30% predicted to result in a reduction of 2271 seeds and 4699 seeds for SB and WG respectively (based on regression equations). For RILs, the explained variance was very low with 1.0% in SB and 0.4% in WG, and P-values were not significant (SB: R2 = 0.01, P = 0.62, df = 96; WG: R2 = 0.004, P = 0.45, df = 96).

Figure 3.

Relationship between the amount of crop genome (%) on the average Seeds Produced per Seed Sown (square-root-transformed) for each backcross (BC1) family and recombinant inbred line (RIL). (A, B) simple regression of fitness on crop genome%, and (C, D) residual regression after the effects of the two major fitness quantitative trait loci were taken out, as covariates; Sites: Sijbekarspel (A and C) and Wageningen (B and D). Dots indicate BC lines and triangles indicate RIL averages. Regression equations:

The results of the regression analysis changed considerably for BC1 families when the variation in SPSS due to the two major fitness QTL was removed (Fig. 3C,D). The variation in SPSS explained by the linear regressions was lower and P-values were no longer significant (SB: R2 = 0.02, P = 0.14, df = 74; WG: R2 = 0.01, P = 0.96, df = 74). For RILs, the explained variance was even lower and non-significant.

For RILs, the average amount of crop genome was similar across fitness QTL genotypes (Table 4: 49.8–52.1%). The most advantageous BC1 fitness QTL genotype (6W–7W) had the lowest amount of crop genome (21.0%), whereas the least advantageous BC1 fitness QTL genotype (6H–7H) had the highest (31.0%), indicating that selection in this BC1 population might lead to a considerable purging of crop genes at these genomic locations.

Discussion

Overlapping and separate genomic regions are under selection

Quantitative trait loci results under field conditions may vary from site to site and genetic material used (Mercer et al. 2006; Muraya et al. 2012). In our case, the crop cultivar, as well as the wild parent, differed between the BC and RIL crossing population. Given this context, it is perhaps surprising that we found several key genomic regions affecting fitness traits in both crossings and environments, next to a number of substantial differences.

Both the BC and RIL populations had two genomic regions, one co-localized and one specific for each cross, with fitness QTL that were consistent across field sites. Fitness distributions and the average rank of fitness QTL genotypes (based on fitness QTL) confirmed that these genomic regions indeed had a substantial impact on the fitness of BC and RIL hybrid lineages. The majority of lines with the most selectively advantageous fitness QTL genotype displayed relatively high seed yields and averaged these groups showed the highest rank compared with other combinations of parental alleles. This pattern with few genomic regions of major impact is similar to QTL selection patterns found in slender wild oat (Latta et al. 2010) and in sunflower (Baack et al. 2008; Dechaine et al. 2009).

Seeds produced per seed sown QTL co-localized at the top of linkage group (LG) 7 for both BC and RILs. The selection differentials showed that the selective advantage was conferred by the wild allele, by favouring a higher SPSS, early flowering and higher survival rates. This QTL region is probably the result of the presence of a major gene for flowering, in which the crop allele confers a selective disadvantage by delaying bolting (Hartman et al. 2012). The second genomic region under selection was specific for each cross, with BC fitness QTL on the bottom of LG6 and RIL fitness QTL on the bottom of LG5. For BC QTL at LG6, it was again the wild allele that gave the selective advantage favouring earlier flowering, higher survival rates, and higher SPSS. These did not co-localize with any RIL QTL. In contrast, for the RIL QTL cluster of LG5, it was the crop allele that favoured SPSS, seed output and seeds per capitulum (Hartman et al. 2012).

Genetic basis of better performing lines

At both field sites and for BC, as well as RIL crossing populations, there was a substantial number of hybrid lines that outperformed their respective wild parent, although hybrids on average produced less seeds per seed sown than the wild parent, with the exception of BC hybrids on clay soil that performed better than the wild parent (see below). This observed hybrid vigour concurs with the transgressive segregation observed in greenhouse experiments employing the same BC and RILs hybrid lineages, in which individual lines had an increased vigour under drought, nutrient limitation and salt stress (Hartman 2012; Uwimana et al. 2012b).

Heterosis, increased hybrid vigour in early-generation hybrids (Rieseberg et al. 2000; Johansen-Morris and Latta 2006), probably explains, for the larger part, that all BC1S1 families produced at least some seeds, even though these hybrids where backcrossed once to one of the parents. In contrast, approximately 30% of RILs produced no seed output. With each subsequent generation, heterozygosity rapidly decreases in a selfing species. Hence, a lettuce RIL population selfed for nine generations lines are virtually entirely homozygous and heterosis effects cannot account for the better performing lines in later generations (Burke and Arnold 2001). However, the higher fitness of early-generation lettuce hybrids may favour survival of hybrids with novel genotypes, thereby increasing the chances for these beneficial novel genotypes to be fixed in later generations (Johansen-Morris and Latta 2006; Latta et al. 2007).

The steep decline in fitness of BC1 families with a higher amount of crop genome indicates there might be a strong selection against and hence, a rapid elimination of crop genome in the first hybrid generations. This could be due to hitchhiking effects, since in early-generation hybrids many crop genes are in LD with genes under selection, as indicated by the lower amount of crop genome of the most advantageous BC1 fitness QTL genotype (based on fitness QTL). In contrast, LD is greatly reduced in 9th generation RILs (Flint-Garcia et al. 2003; Stewart et al. 2003). Moreover, a positively selected crop gene was also segregating in the RIL population. In RILs, all genotypes have approximately the same amount of crop genome. This suggests that in later generations particular combinations of genes became important, independent of linkage drag, giving rise to transgressive segregation (Rieseberg et al. 1999, 2003).

Quantitative trait loci studies have consistently pointed at the additive effects of complementary genes of the two parental species as the most likely underlying genetic basis for transgressive segregation (Rieseberg et al. 1999, 2000; Burke and Arnold 2001). After hybridization, QTL with effects in opposing directions within each parent may recombine in the hybrids, resulting in some lettuce hybrids having a majority of QTL with positive effects leading to a high fitness, or with negative effects leading to a low fitness (Lynch and Walsh 1998; Rieseberg et al. 2007). Indeed, six to seven (BC and RILs results respectively) of the ten traits measured in this study show QTL with opposing effects, where in some genomic locations the crop parental allele is selectively advantageous and in other locations it is the wild parental allele.

Heterosis, linkage and transgressive segregation are not the only genetic processes underlying hybrid fitness. For example, Uwimana et al. (2012b) found epistasis effects in BC1 and BC2 generation lettuce hybrids when subjecting these to several stress treatments in greenhouse conditions. In later generations, these epistasis effects are more likely to contribute to the breakdown of co-adapted gene complexes (Rieseberg et al. 2000; Burke and Arnold 2001) and therefore lower hybrid fitness. This may also partly explain the 30% of RILs without any seed output.

Our results are based on two L. serriola genotypes, a European and an American accession. Genetic diversity in L. serriola is considerable (Van de Wiel et al. 2010), so it would be desirable to study more wild genotypes, for instance, as diallel combinations with crop varieties in future studies.

Higher chance of introgression in novel habitats

Fitness distributions were different among the two habitats used, indicating that introgression of crop alleles through hybridization might be more likely to occur in novel habitats, as opposed to the natural wild habitat of the wild parent. More hybrid lineages performed better than L. serriola in the novel clay soil habitat than in the original sandy soil habitat (habitat requirement as described in Hooftman et al. (2006)), especially BC hybrid lineages. In spite of the fact that the selective advantage for the two BC fitness QTL was conferred by the wild allele, 79% of families performed better than the wild parent (L. serriola Eys) in clay soil, whereas only 5% of BC1S1 families performed better in sandy soil. The lower performance of the wild parent in the clay site was caused by a lower survival until reproduction, as well as a lower than average seed yield of reproducing plants. In addition, the PVE by fitness QTL (in total 36.9% in clay soil and 26.9% in sandy soil) indicates that not all fitness variation was explained by these fitness QTL and that apparently the increased fitness of BC1S1 hybrids in clay soil could be due to their mixed crop–wild genomic background and heterosis effects.

It should be noted our experiments included one location of each habitat type, albeit with large differences in conditions and replicated plots, but experiments with multiple sites for each habitat are needed to see if crop–wild hybrid individuals indeed perform better in novel habitats compared with the natural wild habitat. This pattern has been found in other species. In slender wild oat, more hybrid genotypes were able to outperform the parental lines in a greenhouse environment, representing a novel habitat, than in the original wild habitat (Johansen-Morris and Latta 2008). Similarly, radish crop–wild hybrids exhibited a higher survival rate and produced more seeds per plant relative to the wild parent in a new environment, whereas they had comparable survival rates but produced fewer seeds in the original habitat (Campbell et al. 2006). Our results also concur with those found by Hooftman et al. (2005, 2007, 2009), in crossings of the same parents as the BC lines of the current study. They found a strong heterosis effect in the clay soil averaging over all lines, but also a clear hybrid vigour breakdown over multiple generations potentially through further segregation or epistasis effects.

Implications for crop breeding and risk assessment

The genetic processes underlying hybrid fitness have important consequences for the chances of crop (trans)gene transfer to wild populations and, therefore, for the methods of ERA. Many studies on crop–wild hybrid fitness use the average fitness of hybrid classes (Halfhill et al. 2005; Hooftman et al. 2005; Mercer et al. 2006; Campbell and Snow 2007; Huangfu et al. 2011); in case hybrid fitness is low compared with the wild parent this is taken to suggest that chances for crop allele transfer are low as well. However, our results and those of others indicate that particular hybrid genotypes may outperform the parental lines under certain environmental conditions (Burke and Arnold 2001; Johansen-Morris and Latta 2008; Hooftman et al. 2009). Furthermore, the high and significant selection differentials for fitness traits (including flowering date) and the broad-sense heritability values suggest that selection in crop–wild hybrid populations can be a dynamic and rapid process. Also, although it appears that a larger amount of crop genome decreased hybrid fitness, there was considerable spread in fitness among hybrid lines with similar crop–wild genomic ratio. Therefore, even if hybrids on average have a lower fitness, particular hybrid lines with a large amount of crop genome may exist that have a higher fitness. Thus, a lower average fitness of hybrids does not preclude gene transfer between crops and their wild relatives.

In addition, we have found that results can be cultivar-specific, that is, the fitness of hybrids depends on the specific combination of crop and wild parent and hence, fitness studies for risk assessment should include a range of wild parents (Muraya et al. 2012). Similarly, selection pressures differ across time and place, so ideally risk assessment should be performed at several locations and in multiple years (Hails and Morley 2005). ERA including hybrids of several parental lines, locations and years involves field experiments with a huge amount of time and labour. However, measuring life history traits can already lead to robust conclusions, because through QTL analysis most genomic selection patterns can be identified (Hartman et al. 2012).

Conclusion and way forward

Our results show that there is a high likelihood in lettuce for novel crop–wild hybrids to arise that have a higher fitness than the wild parent through combinations of heterosis, linkage and transgressive segregation. This may be more likely to occur in novel habitats (Barton 2001). Consequently, this provides an avenue for introgression of crop alleles into the wild population. We did identify a genomic region on LG7 where the crop allele induced delayed flowering that was under negative selection. In this region, effects were stable across cultivars and the environments of our field experiments and it could therefore be used in transgene mitigation strategies. In such a strategy, the transgene is closely linked to a region or gene with a strong negative selection effect in the habitat of the wild type (Gressel 1999; Stewart et al. 2003).

This study is only a first step to identify the specific genes involved, and further work including the creation of Near Isogenic Lines (NILs) is being planned. Whether the detrimental effect of delayed flowering is strong enough to prevent crop (trans)gene escape will be explored further in simulation models using these empirical field data.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the laboratory of R.W. Michelmore (UC Davis) for producing and genotyping the RILs and graciously providing the seeds from their collection to us, and for developing the SNPs used to genotype the BC1 population. The RIL collection is part of the Compositae Genome Project (http://compgenomics.ucdavis.edu) and is supported by the NSF Plant Genome Program award #0820451. We like to thank Gerard Oostermeijer for his input in discussions. We are grateful for our field plot provided by family Stapel in Sijbekarspel and for the cooperation with Wageningen University and use of an experimental field plot there. Justus Houthuesen established and maintained the plot in Sijbekarspel. We also thank the many people that helped with the enormous amount of fieldwork especially Rob Bregman, Louis Lie, Harold Lemereis and the technical staff in Wageningen. This study is funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) as part of the ERGO program (838.06.041 and 838.06.042).

Data archiving

The data used in this article are available as Supporting information.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Data S1. Equation 1 in Hooftman et al. 2005 no. of capitula = 50·6 (no. of branches) + 177 (no. of shoots) − 5·3 (Regression analysis: R2 = 0.51, P < 0·001, n = 315 plants).

Table S1. Weather conditions in Sijbekarspel (SB) and Wageningen (WG) during the period of the experiment (May—October).

Table S2. Positions of quantitative trait loci (QTL) for seeds produced per seed sown (SPSS) in a recombinant inbred lines population from a Lactuca sativa cv. Salinas × Lactuca serriola (UC96US23) cross using composite interval mapping.

Literature cited

- Argyris J, Truco MJ, Ochoa O, Knapp SJ, Still DW, Lenssen GM, Schut JW, et al. Quantitative trait loci associated with seed and seedling traits in Lactuca. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;111:1365–1376. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baack EJ, Sapir Y, Chapman MA, Burke JM, Rieseberg LH. Selection on domestication traits and quantitative trait loci in crop–wild sunflower hybrids. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17:666–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton NH. The role of hybridization in evolution. Molecular Ecology. 2001;10:551–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlsma R, Westerhof MDD, Roekx LP, Pen I. Dynamics of genetic rescue in inbred Drosophila melanogaster populations. Conservation Genetics. 2010;11:449–462. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JM, Arnold ML. Genetics and the fitness of hybrids. Annual Review of Genetics. 2001;35:31–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.085719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LG, Snow AA. Competition alters life history and increases the relative fecundity of crop–wild radish hybrids (Raphanus spp.) New Phytologist. 2007;173:648–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LG, Snow AA, Ridley CE. Weed evolution after crop gene introgression: greater survival and fecundity of hybrids in a new environment. Ecology Letters. 2006;9:1198–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahal GS, Gosal SS. Principles and Procedures of Plant Breeding: Biotechnological and Conventional Approaches. Harrow, UK: Alpha Science International Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea L, Felber F, Guadagnuolo R. Hybridization rates between lettuce (Lactuca sativa) and its wild relative (L. serriola) under field conditions. Environmental Biosafety Research. 2008;7:61–71. doi: 10.1051/ebr:2008006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechaine JM, Burger JC, Chapman MA, Seiler GJ, Brunick R, Knapp SJ, Burke JM. Fitness effects and genetic architecture of plant-herbivore interactions in sunflower crop–wild hybrids. New Phytologist. 2009;184:828–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerge RW, Churchill GA. Permutation tests for multiple loci affecting a quantitative character. Genetics. 1996;142:285–294. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.1.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Guidance for risk assessment of food and feed from genetically modified plants. EFSA Journal. 2011;9:2150. [Google Scholar]

- Flint-Garcia SA, Thornsberry JM, Buckler ES. Structure of linkage disequilibrium in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2003;54:357–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannino D, Nicolodi C, Testone G, Iannelli E, Di Giacomo MA, Frugis G, Mariotti D. Pollen-mediated transgene flow in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) Plant Breeding. 2008;127:308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Gressel J. Tandem constructs: preventing the rise of superweeds. Trends in Biotechnology. 1999;17:361–366. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hails RS, Morley K. Genes invading new populations: a risk assessment perspective. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2005;20:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfhill MD, Sutherland JP, Moon HS, Poppy GM, Warwick SI, Weissinger AK, Rufty TW, et al. Growth, productivity, and competitiveness of introgressed weedy Brassica rapa hybrids selected for the presence of Bt cry1Ac and gfp transgenes. Molecular Ecology. 2005;14:3177–3189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman Y. the Netherlands: University of Amsterdam; 2012. Genomic regions under selection in crop–wild hybrids of Lettuce: implications for crop breeding and environmental risk assessment. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman Y, Hooftman DAP, Uwimana B, Smulders CCM, van de Wiel MJM, Visser RGF, van Tienderen PH. Genomic regions in crop–wild hybrids of lettuce are affected differently in different environments: implications for crop breeding. Evolutionary applications. 2012;5:629–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00240.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser TP, Jorgensen RB, Ostergard H. Fitness of backcross and F-2 hybrids between weedy Brassica rapa and oilseed rape (B-napus) Heredity. 1998;81:436–443. [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock D, McGoldrick DJ, Bayne BL. Hybrid vigor in Pacific oysters: an experimental approach using crosses among inbred lines. Aquaculture. 1995;137:285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hooftman DAP, Oostermeijer JGB, Jacobs MMJ, den Nijs HCM. Demographic vital rates determine the performance advantage of crop–wild hybrids in lettuce. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2005;42:1086–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Hooftman DAP, Oostermeijer JGB, den Nijs HCM. Invasive behavior of Lactuca serriola (Asteraceae) in The Netherlands: spatial distribution and ecological amplitude. Basic and Applied Ecology. 2006;7:507–519. [Google Scholar]

- Hooftman DAP, Jong MJD, Oostermeijer JGB, den Nijs HCM. Modelling the long-term consequences of crop–wild relative hybridization: a case study using four generations of hybrids. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2007;44:1035–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Hooftman DAP, Hartman Y, Oostermeijer JGB, den Nijs HJCM. Existence of vigorous lineages of crop–wild hybrids in lettuce under field conditions. Environmental Biosafety Research. 2009;8:203–217. doi: 10.1051/ebr/2010001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooftman DAP, Flavell AJ, Jansen H, Syed HCM, den Nijs NH, Sørensen AP, Orozco-ter Wengel P, et al. Locus-dependent selection in crop–wild hybrids of lettuce under field conditions and its implication for GM crop development. Evolutionary Applications. 2011;4:648–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2011.00188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu C, Qiang S, Song X. Performance of hybrids between transgenic oilseed rape (Brassica napus) and wild Brassica juncea. An evaluation of potential for transgene escape. Crop Protection. 2011;30:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hund A, Reimer R, Messmer R. A consensus map of QTLs controlling the root length of maize. Plant and Soil. 2011;344:143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen-Morris AD, Latta RG. Fitness consequences of hybridization between ecotypes of Avena barbata: hybrid breakdown, hybrid vigor, and transgressive segregation. Evolution. 2006;60:1585–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen-Morris AD, Latta RG. Genotype by environment interactions for fitness in hybrid genotypes of Avena barbata. Evolution. 2008;62:573–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WC, Jackson LE, Ochoa O, Peleman R, van Wijk J, St Clair DA, Michelmore RW. Lettuce, a shallow-rooted crop, and Lactuca serriola, its wild progenitor, differ at QTL determining root architecture and deep soil water exploitation. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2000;101:1066–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman WJM, Zevenbergen MJ, van den Berg RG. Species relationships in Lactuca SL (Lactuceae, Asteraceae) inferred from AFLP fingerprints. American Journal of Botany. 2001;88:1881–1887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latta RG, Gardner KM, Johansen-Morris AD. Hybridization, recombination, and the genetic basis of fitness variation across environments in Avena barbata. Genetica. 2007;129:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s10709-006-9012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latta RG, Gardner KM, Staples DA. Quantitative trait locus mapping of genes under selection across multiple years and sites in Avena barbata: epistasis, pleiotropy, and genotype-by-environment interactions. Genetics. 2010;185:375–385. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.114389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Walsh B. Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers; 1998. pp. 477–478. [Google Scholar]

- Martin NH, Bouck AC, Arnold ML. Detecting adaptive trait introgression between Iris fulva and I. brevicaulis in highly selective field conditions. Genetics. 2006;172:2481–2489. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.053538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer KL, Wyse DL, Shaw RG. Effects of competition on the fitness of wild and crop–wild hybrid sunflower from a diversity of wild populations and crop lines. Evolution. 2006;60:2044–2055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer KL, Andow DA, Wyse DL, Shaw RG. Stress and domestication traits increase the relative fitness of crop–wild hybrids in sunflower. Ecology Letters. 2007;10:383–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraya MM, Geiger HH, Sagnard F, Toure L, Traore PCS, Togola S, de Villiers S, et al. Adaptive values of wild × cultivated sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) hybrids in generations F(1), F(2), and F(3) Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2012;59:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata RT. Clip-and-wash method of emasculation for lettuce. Hortiscience. 1992;27:907–908. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 15 November 2011) [Google Scholar]

- Rhode JM, Cruzan MB. Contributions of heterosis and epistasis to hybrid fitness. American Naturalist. 2005;166:124–139. doi: 10.1086/491798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Archer MA, Wayne RK. Transgressive segregation, adaptation and speciation. Heredity. 1999;83:363–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6886170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Baird SJE, Gardner KA. Hybridization, introgression, and linkage evolution. Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;42:205–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Widmer A, Arntz AM, Burke JM. The genetic architecture necessary for transgressive segregation is common in both natural and domesticated populations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B: Biological Sciences. 2003;358:1141–1147. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Kim SC, Randell RA, Whitney KD, Gross BL, Lexer C, Clay K. Hybridization and the colonization of novel habitats by annual sunflowers. Genetica. 2007;129:149–165. doi: 10.1007/s10709-006-9011-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder EJ. Lettuce, Endive and Chicory. Wallingford, UK: CAB International; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. PASW Statistics 17.0 Command Syntax Reference. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CN, Halfhill MD, Warwick SI. Transgene introgression from genetically modified crops to their wild relatives. Nature Reviews: Genetics. 2003;4:806–817. doi: 10.1038/nrg1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy BPM, Sarla N. Meta-analysis of yield QTLs derived from inter-specific crosses of rice reveals consensus regions and candidate genes. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 2011;29:663–680. [Google Scholar]

- Uwimana B, D'Andrea L, Felber F, Hooftman DAP, den Nijs HCM, Smulders MJM, Visser RGF, et al. A Bayesian analysis of gene flow from crops to their wild relatives: cultivated (Lactuca sativa L.) and prickly lettuce (L. serriola L.) and the recent expansion of L. serriola in Europe. Molecular Ecology. 2012a;21:2640–2654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05489.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uwimana B, Smulders MJM, Hooftman DAP, Hartman Y, Jansen PH, van Tienderen J, McHale LK, et al. Crop to wild introgression in lettuce: following the fate of crop genome segments in backcross populations. BMC Plant Biology. 2012b;12:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Wiel CCM, Rajičić TS, Dehmer R, van Treuren KJ, van der Linden CG, van Hintum TJL. Distribution of genetic diversity in wild European populations of prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola): implications for plant genetic resources management. Plant Genetic Resources-Characterization and Utilization. 2010;8:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Voorrips RE. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. Journal of Heredity. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries IM. Origin and domestication of Lactuca sativa L. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 1997;44:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Basten CJ, Zeng ZB. 2010. Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5, Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC.

- Weinig C, Dorn LA, Kane NC, German ZM, Hahdorsdottir SS, Ungerer MC, Toyonaga Y, et al. Heterogeneous selection at specific loci in natural environments in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2003;165:321–329. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.1.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang FZ, Wagstaff C, Rae AM, Sihota AK, Keevil CW, Rothwell SD, Clarkson GJJ, et al. QTLs for shelf life in lettuce co-locate with those for leaf biophysical properties but not with those for leaf developmental traits. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:1433–1449. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.