Abstract

The nucleotide-sugar–activated P2Y14 receptor (P2Y14-R) is highly expressed in hematopoietic cells. Although the physiologic functions of this receptor remain undefined, it has been strongly implicated recently in immune and inflammatory responses. Lack of availability of receptor-selective high-affinity antagonists has impeded progress in studies of this and most of the eight nucleotide-activated P2Y receptors. A series of molecules recently were identified by Gauthier et al. (Gauthier et al., 2011) that exhibited antagonist activity at the P2Y14-R. We synthesized one of these molecules, a 4,7-disubstituted 2-naphthoic acid derivative (PPTN), and studied its pharmacological properties in detail. The concentration-effect curve of UDP-glucose for promoting inhibition of adenylyl cyclase in C6 glioma cells stably expressing the P2Y14-R was shifted to the right in a concentration-dependent manner by PPTN. Schild analyses revealed that PPTN-mediated inhibition followed competitive kinetics, with a KB of 434 pM observed. In contrast, 1 μM PPTN exhibited no agonist or antagonist effect at the P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11, P2Y12, or P2Y13 receptors. UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis of differentiated HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells was blocked by PPTN with a concentration dependence consistent with the KB determined with recombinant P2Y14-R. In contrast, the chemotactic response evoked by the chemoattractant peptide fMetLeuPhe was unaffected by PPTN. UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis of freshly isolated human neutrophils also was blocked by PPTN. In summary, this work establishes PPTN as a highly selective high-affinity antagonist of the P2Y14-R that is useful for interrogating the action of this receptor in physiologic systems.

Introduction

Extracellular nucleotides interact with at least 15 different cell surface receptors to regulate a panoply of cell signaling and physiologic responses (Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998; Burnstock, 2007). Seven of these are G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that are solely activated by nucleotides (Abbracchio et al., 2006; von Küglegen and Harden, 2012) and include the ADP-activated P2Y1 receptor (P2Y1-R), P2Y12-R, and P2Y13-R; the ATP-activated P2Y11-R; the UDP-activated P2Y6-R; the UTP-activated P2Y4-R; and the ATP- and UTP-activated P2Y2-R. An eighth member of this structural and functional family of GPCR, the P2Y14-R, is uniquely activated by UDP-glucose and other nucleotide sugars (Chambers et al., 2000; Harden et al., 2010), although recent work revealed that this receptor is also activated potently by UDP (Carter et al., 2009).

The P2Y14-R also is relatively distinct among the P2Y receptors because of its limited but very high level of expression in a few tissues, including several areas of the brain, the gastrointestinal tract, and cells of the immune and inflammatory response axes (Chambers et al., 2000; Freeman et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2003; Skelton et al., 2003). Human neutrophils express large amounts of P2Y14-R mRNA (Moore et al., 2003), and incubation of neutrophils with UDP-glucose results in phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Scrivens and Dickinson, 2006; Fricks et al., 2008). Although the function of this receptor in neutrophils and other pro-inflammatory cells remains uncertain, insight is accruing. For example, UDP-glucose promotes activation of Rho in human neutrophils, and this cell signaling response was accompanied by cytoskeletal rearrangement, alteration in cell shape, and an increase in chemotaxis toward a gradient of UDP-glucose (Sesma et al., 2012). These cellular responses to agonist were completely blocked by an inhibitor of Rho kinase. Studies with P2Y14-R knockout mice recently revealed that the P2Y14-R plays a key role in recruitment of macrophages to liver, local inflammation, and induction of insulin resistance that occur in a high fat model of obesity and type 2 diabetes (Xu et al., 2012).

UDP-glucose is present in high concentrations in the secretory pathway and is released from most cells as a component of the secretory machinery (Lazarowski et al., 2003, 2011; Sesma et al., 2009). Nucleotide sugars are resistant to hydrolysis by the nucleotide-hydrolyzing ecto-nucleoside di- and tri-phosphohydrolases (Zimmermann, 2000), and therefore, high concentrations of UDP-glucose can occur in the extracellular milieu of, for example, mucin-secreting airway epithelial cells (Kreda et al., 2007; Okada et al., 2011) and lung secretions in patients with cystic fibrosis (Sesma et al., 2009; Lazarowski et al., 2011). Thus, we and others have hypothesized that UDP-glucose functions as an extracellular pro-inflammatory mediator, and the P2Y14-R on neutrophils and, possibly, other immune cells functions as a key cell surface gate-keeper in this action.

A general lack of receptor-selective molecular probes has proved to be an obstacle to elucidation of the function of P2Y receptors in mammalian physiology and pathophysiology. Fully reliable antagonist molecules exist for only two (the ADP-activated P2Y1-R and P2Y12-R) of the eight P2Y receptors (von Küglegen and Harden, 2011; Jacobson et al., 2012). Availability of a receptor-selective antagonist for the P2Y14-R receptor is crucial for elucidation of the role(s) played by this signaling protein in inflammatory/immune responses. To this end, two classes of molecules recently were found by Black and colleagues to act as antagonists of the P2Y14-R, and these hits were structurally modified to enhance receptor affinity (Gauthier et al., 2011; Guay et al., 2011; Robichaud et al., 2011). We now have studied one of these optimized compounds in detail. We illustrate that this drug acts as a high-affinity competitive antagonist of the P2Y14-R and does so without interacting with any of the other seven P2Y receptor subtypes. Of importance, this antagonist blocks UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis of human neutrophils. We conclude that this molecular probe will be highly useful for further interrogation of the functional role(s) played by the P2Y14-R in mammalian physiology and pathophysiology.

Materials and Methods

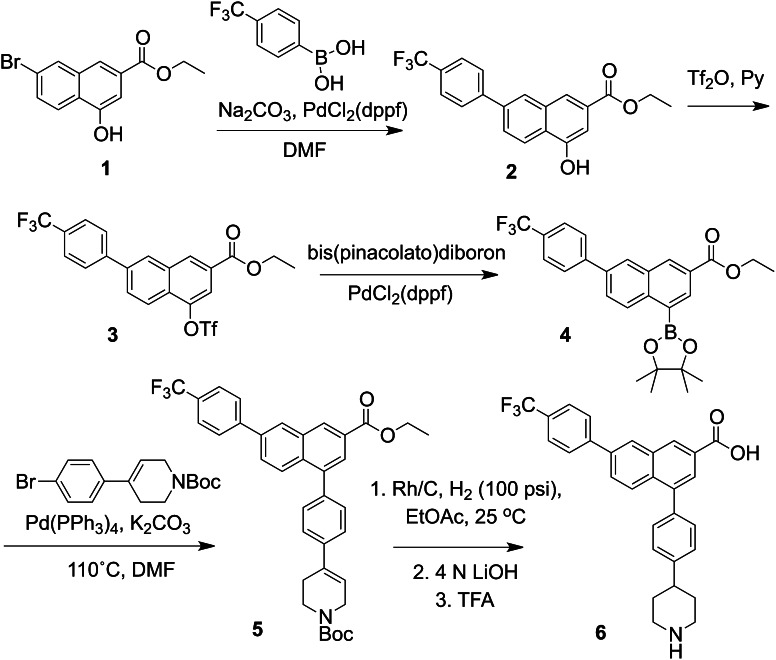

Synthesis of 4-((Piperidin-4-yl)-Phenyl)-7-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)-Phenyl)-2-Naphthoic Acid.

A 2-naphthoic acid derivative 4-((piperidin-4-yl)-phenyl)-7-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-2-naphthoic acid (PPTN) was synthesized as described elsewhere (Belly et al., 2009; Gauthier et al., 2011). In brief, the starting material (1, Fig. 1), prepared as described (Boger et al., 1996), was subjected to a Suzuki coupling, and the resulting phenol 2 converted to the triflate 3. After boronation, a second Suzuki coupling produced 5, which was reduced and deprotected (two steps) to provide the desired product PPTN, 6. The 1H-NMR and high-resolution mass spectrum of 6 was consistent with the assigned structure. PPTN was used as dimethylsulfoxide stock solution (5 mM), which was stable to storage at 4°C. Additional details of the chemical synthesis are provided (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Fig. 1.

Structure and synthetic route of PPTN. The synthetic procedure is briefly described in Materials and Methods and is based on Boger et al. (1996) and Belly et al. (2009). Additional details of the procedures also are provided (Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

P2Y-R Cell Lines.

Stable 1321N1 human astrocytoma cell lines individually expressing the P2Y1-R, P2Y2-R, P2Y4-R, P2Y6-R, or P2Y11-R were generated as previously described (Nicholas et al., 1996; Schachter et al., 1996; Qi et al., 2001). C6 rat glioma cells stably expressing the P2Y14-R and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing the P2Y12-R were generated as previously described (Fricks et al., 2009).

Cell Culture.

All cell lines were maintained at 37°C and at 5% CO2. C6 cells were cultured in F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). CHO cells were maintained in F-12 medium with 10% FBS and 1% geneticin, and 1321N1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 5% FBS and 1% geneticin. HL-60 promyeloleukemia cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Differentiation of HL-60 cells (dHL-60 cells) was performed by adding 1.3% dimethylsulfoxide to the medium for 5 days.

Quantification of Cyclic AMP Accumulation.

Cells were plated in 24-well plates approximately 24 hours before the assay and were labeled 2 hours before the assay with 1 µCi [3H]adenine/well in 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-buffered serum-free DMEM. All assays were in the presence of 200 µM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) and were initiated by the addition of 30 μM forskolin, agonists, and/or PPTN. Incubations were for 15 minutes at 37°C and were terminated by aspiration of medium and addition of 500 µl ice-cold 5% trichloroacetic acid. [3H]Cyclic AMP was isolated by sequential Dowex and alumina chromatography (Salomon et al., 1974), as previously described (Harden et al., 1982).

Inositol Phosphate Accumulation in Cell Lines Stably Expressing P2Y Receptors.

Stable 1321N1 human astrocytoma cell lines for each of the Gq/phospholipase C–coupled P2Y receptors (i.e., P2Y1-1321N1, P2Y2-1321N1, P2Y4-1321N1, P2Y6-1321N1, and P2Y11-1321N1 cells) were used in experiments designed to examine the P2Y-R subtype selectivity of PPTN. Cells were plated (20,000 cells/well) in 96-well plates two days before assay, and 16 hours before the assay, the inositol lipid pool of the cells was radiolabeled by incubation in 100 µl of serum-free inositol-free DMEM containing 1.0 µCi of myo-[3H]inositol. Incubations with drugs were in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)–buffered Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 10 mM LiCl and were terminated after 30 minutes at 37°C by aspiration of the medium and addition of 50 mM formic acid. The samples were neutralized with 150 mM ammonium hydroxide, and [3H]inositol phosphate accumulation was quantified using Dowex chromatography and liquid scintillation counting, as previously described (Brown et al., 1991).

Inositol Phosphate Accumulation in Transiently Transfected Cells.

COS-7 cells were plated in 12-well plates at 65,000 cells per well and were transfected 24 hours later with expression vectors for Gαq/i and either the human P2Y13-R or P2Y14-R. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were labeled with 1 µCi of myo-[3H]inositol in 400 μl of serum-free inositol-free DMEM. Quantification of [3H]inositol phosphate accumulation in the presence of drugs was accomplished as described above for the stable P2Y-R cell lines.

Purification of Human Neutrophils.

Fresh venous blood samples were obtained from healthy male and female volunteers with written informed consent and the approval of the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board. Neutrophils were isolated (>98% purity) using Ficoll-paque Plus (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) and 3% dextran as described previously (Sesma et al., 2012). The isolated neutrophils were rinsed and resuspended (1 × 106 cells/ml) in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Apyrase (1 U/ml) was included in the isolation steps to remove nucleotides potentially released from damaged or mechanically activated neutrophils (e.g., during cell washes and centrifugation) and, thus, to avoid unwanted activation of P2Y2-R or P2X1-R expressed in these cells (Verghese et al., 1996; Vaughan et al., 2007; Lecut et al., 2009).

Quantification of Chemotaxis.

Human neutrophils were loaded with 2.5 μM carbocyanide dye 1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine perchlorate (DID; Vybrant Cell-Labeling Solutions; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 15 minutes (106 cells/ml) in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, and dHL-60 cells were loaded with 2.5 μM DID in HEPES-buffered (pH 7.4) HBSS supplemented with 1.6 mM CaCl2 and 0.8 mM MgCl2. Cells were rinsed twice and suspended in RPMI or HBSS as above. Chemotaxis was quantified in 96-multiwell FluoroBlock inserts (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as described previously (Sesma et al., 2012). In brief, vehicle or agonist was added to the lower compartment (225 μl), and 75-μl of a cell suspension (2 × 105 cells) was loaded onto the upper compartment in the absence or presence of the indicated amount of PPTN. The fluorescent signal (F, 612 nm excitation/670 nm emission) was read at the indicated times with use of a Tecan Infinite M1000 plate reader. The chemotaxis index (Ctx Index) was defined as:

Ctx Index = (F1 – FB) ⁄ (F0 – FB), where F1 and F0 represent the fluorescence signal from stimulated and unstimulated cells, respectively, and FB is background fluorescence measured in the absence of cells. Typical values for fluorescence in these experiments were: F(B) = 180, F(0) = 1000, F(UDP-glucose) = 1300–1600; F[formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP)] = 2300–2500.

Data Analysis.

Nonlinear regression and Schild analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). All experiments were repeated at least three times.

For chemotaxis experiments, statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey honestly significant difference (P ≤ 0.05; JMP Genomics, version 4.1; SAS, Cary, NC).

Materials.

IBMX, forskolin, and apyrase were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). UDP, UDP-glucose, ATP, UTP, and 2-methylthio-adenosine 5′-diphosphate (2MeSADP) all were from Fluka and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. [3H]Adenine and myo-[3H]inositol were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). Geneticin, serum, and all cell culture medium were from Invitrogen.

Results

A series of recently synthesized molecules were reported to act as antagonists of the P2Y14-R. One of these, PPTN (Fig. 1), was synthesized as described in Materials and Methods, and the activity and selectivity of this molecule was investigated in detail with (1) a stable cell line that expresses the human P2Y14-R, (2) cells expressing each of the other seven G protein–coupled P2Y receptors, (3) HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells, and (4) human neutrophils.

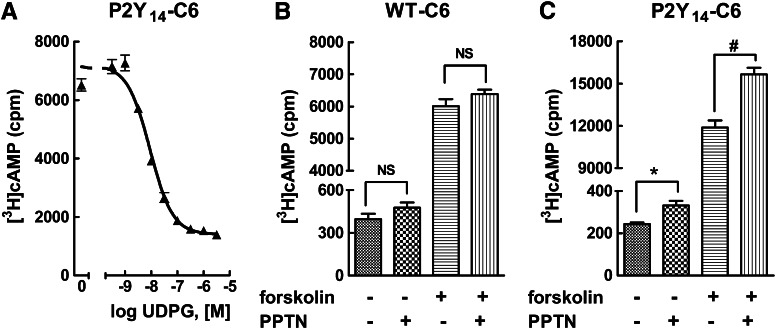

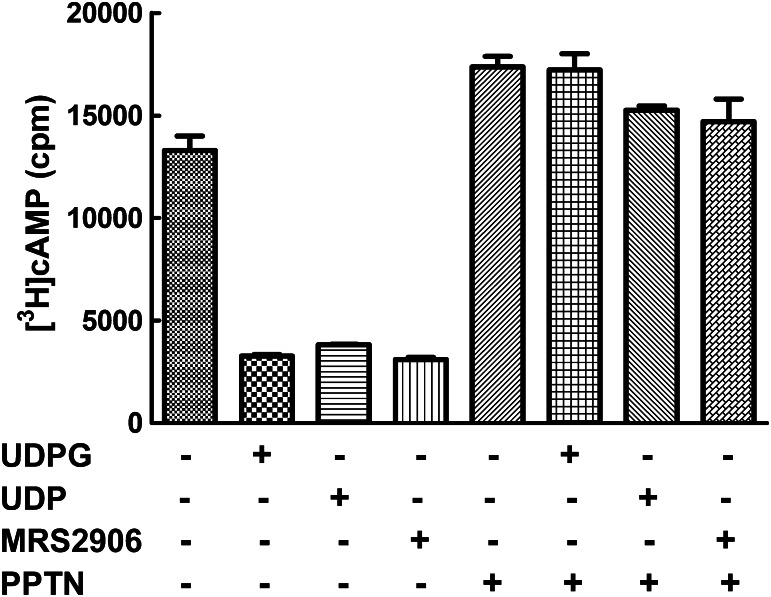

We previously showed that UDP-glucose and UDP act as potent agonists to inhibit forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in C6 rat glioma or CHO cells stably expressing the human P2Y14-R receptor, but these agonists have no inhibitory effect in wild-type C6 or CHO cells (Fricks et al., 2008; Carter et al., 2009). As shown in Fig. 2A, UDP-glucose promotes concentration-dependent inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation in P2Y14-C6 cells with an EC50 value of ∼10 nM. We previously reported that constitutive release of UDP-glucose occurs from many different cell lines, including C6 cells, resulting in significant accumulation of this agonist in the extracellular medium (Lazarowski et al., 2003). One prediction from these previous studies is that inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity may occur in P2Y14-C6 cells because of constitutive release of UDP-glucose and that drug-mediated blockade of the P2Y14-R would reverse this inhibition by antagonizing the action of the nucleotide sugar at its cell surface receptor. Therefore, basal and forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation was measured in wild-type and P2Y14-C6 cells in the absence and presence of 100 nM PPTN. Whereas no effect of PPTN on cyclic AMP levels was observed in wild-type C6 cells (Fig. 2B), both basal and forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation were elevated in P2Y14-C6 cells (Fig. 2C). Because of the effect observed in P2Y14-C6 cells, a full concentration effect curve for PPTN was performed (Fig. 3). Both basal and forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation were elevated over similar concentration ranges with the maximal effect of PPTN observed around a concentration of 100 nM. These results are consistent with the idea that constitutively released UDP-glucose (and potentially other nucleotide-sugars) promotes inhibition of adenylyl cyclase in P2Y14-C6 cells, and this effect is reversed by PPTN-dependent antagonism of the P2Y14-R.

Fig. 2.

PPTN blocks P2Y14-R–dependent elevation of cyclic AMP levels in P2Y14-C6 cells. (A) Cyclic AMP accumulation was quantified in P2Y14-C6 cells in the presence of 30 μM forskolin and the indicated concentrations of UDP-glucose (UDPG) as described in Materials and Methods. The results are the mean of triplicate determinations and are representative of results of at least three separate experiments. (B) Basal and forskolin (30 μM)–stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation was quantified in the absence or presence of 1 μM PPTN in wild-type (WT) C6 glioma cells. The results are the mean of triplicate determinations and are representative of results of three separate experiments. (C) Basal and forskolin (30 μM)–stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation was quantified in the absence or presence of 100 nM PPTN in P2Y14-C6 glioma cells. The results are the mean of triplicate determinations and are representative of results of three separate experiments. NS, not significant; (*) and (#), significantly different from vehicle and forskolin, respectively; P < 0.05 by unpaired t test.

Fig. 3.

Concentration-dependent effect of PPTN on cyclic AMP levels in P2Y14-C6 cells. Basal and forskolin (30 μM)–stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation was quantified in the presence of the indicated concentrations of PPTN in P2Y14-C6 glioma cells. The results are the mean of triplicate determinations and are representative of results of at least three separate experiments.

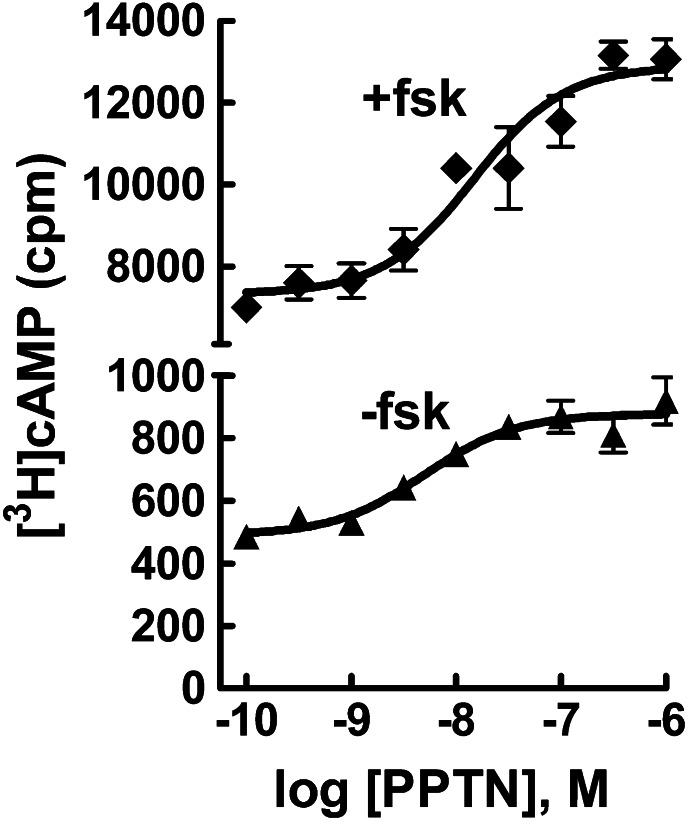

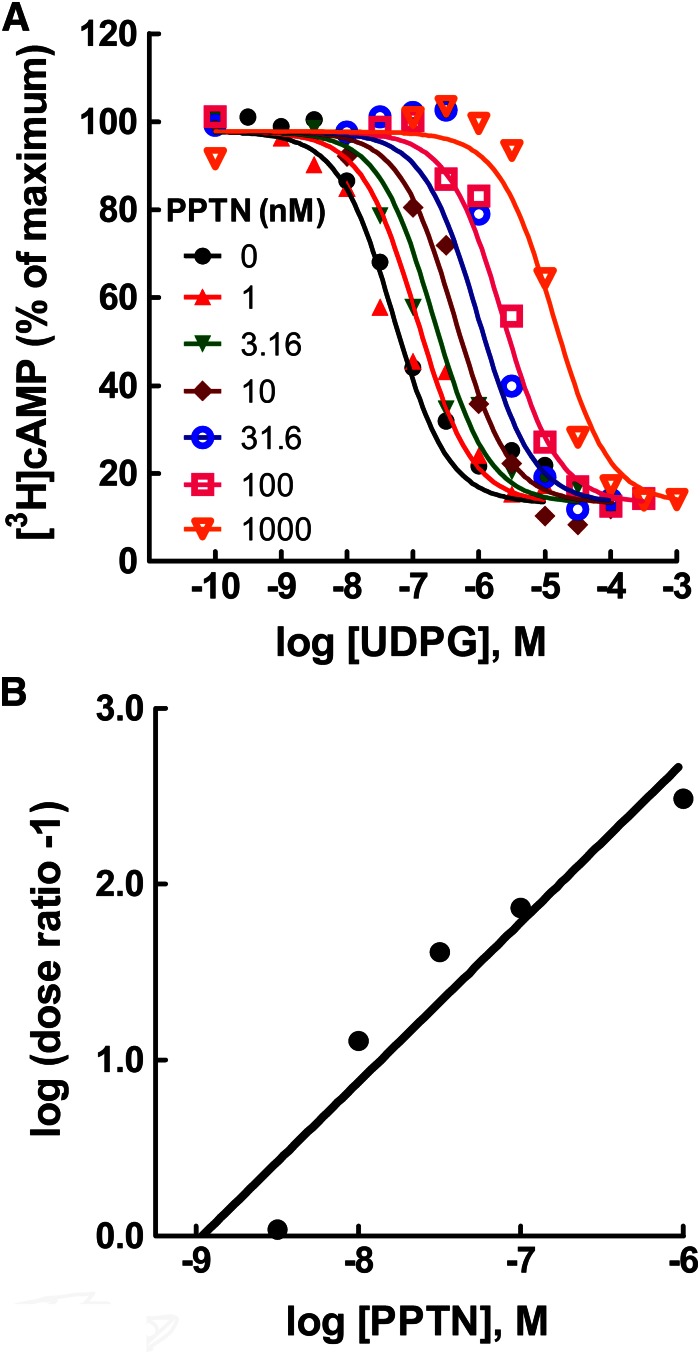

The idea that PPTN acts as an antagonist in P2Y14-C6 cells was tested directly by generating concentration effect curves for UDP-glucose for inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation in the presence of various concentrations of PPTN (Fig. 4A). Concentrations of PPTN as low as 1 nM antagonized the effect of UDP-glucose, and a parallel shift to the right of the UDP-glucose concentration effect curve was observed with increasing concentrations of PPTN. The surmountable antagonism observed with PPTN over a 10,000-fold range of concentrations is consistent with competitive antagonism occurring at the orthosteric binding pocket of the P2Y14-R. However, we cannot rule out involvement of an additional mechanism, because the slopes of Schild plots from multiple experiments were typically greater than 1.0 (Fig. 4B). This occurred whether PPTN was added simultaneously with UDP-glucose or cells were preincubated with PPTN for up to 30 minutes before addition of agonist. The KB value of PPTN obtained from four separate experiments, similar to that shown in Fig. 4B, was 434 ± 126 pM.

Fig. 4.

High-affinity competitive antagonism of the human P2Y14-R by PPTN. (A) Concentration effect curves for UDP-glucose (UDPG) for inhibition of forskolin (30 μM)–stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation were generated in P2Y14-C6 glioma cells in the presence of the indicated concentrations of PPTN. The data are the mean of triplicate determinations, and the results are similar to those obtained in four separate experiments. Typical values for basal and forskolin-stimulated [3H]cyclic AMP accumulation were approximately 1000 and 9000 cpm, respectively. (B) A Schild plot was generated by determining the dose ratio (concentration of agonist necessary to produce a chosen level of effect in the presence of the indicated concentration of PPTN divided by the concentration of agonist that produces the same effect in the absence of antagonist) for each concentration of antagonist and then plotting log (dose ratio -1) on the Y-axis versus concentration of antagonist presented on the X-axis. The KB determined from the intercept of the regressed line on the X- axis was 1150 pM, and a slope of 0.91 was observed. The results are similar to those obtained in four separate experiments.

UDP is also a cognate agonist of the P2Y14-R (Carter et al., 2009), and as shown in Fig. 5, the capacity of this nucleotide to inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity in P2Y14-C6 cells was blocked by PPTN. MRS2906 (β-ethyl ester of 2-thio-UDP) was synthesized as a high-affinity selective agonist of the P2Y14-R (Das et al., 2010), and as was the case with the natural agonists of this receptor, its activity also was blocked by PPTN (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results reveal that PPTN is a potent competitive antagonist of the orthosteric binding site of the P2Y14-R.

Fig. 5.

PPTN blocks the agonist action of UDP and a receptor-selective synthetic analog at the P2Y14-R. Forskolin (30 μM)–stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation was quantified in P2Y14-C6 cells in the presence of 1 μM UDP-glucose (UDPG), UDP, or MRS2906 with or without 300 nM PPTN. The results are from triplicate determinations and are representative of results from three different experiments.

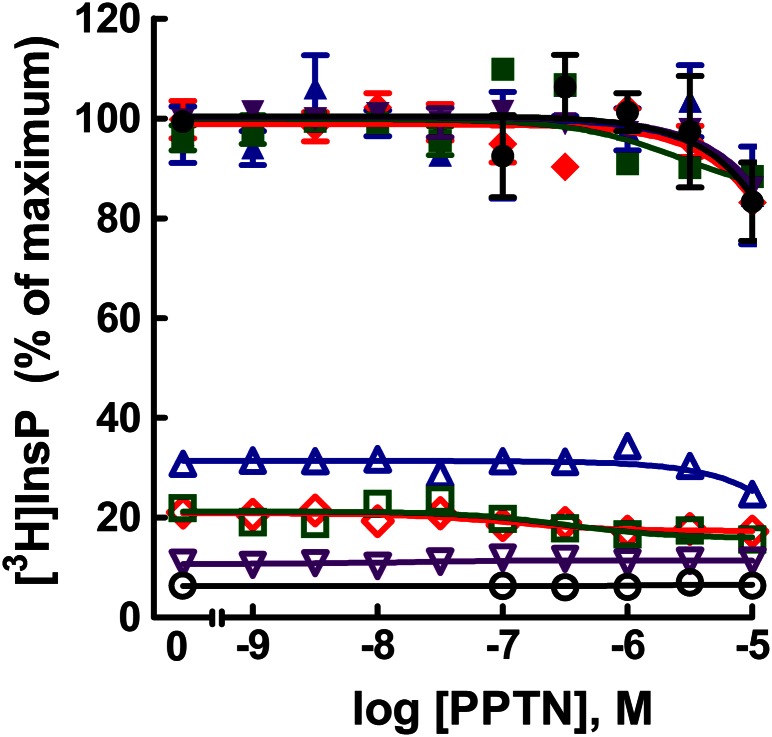

The receptor selectivity of PPTN is not known, and therefore, we examined the possibility that this molecule might also interact with additional P2Y receptor subtypes. The capacity of agonists (2MeSADP, UTP, UTP, UDP, and ATP) of the human P2Y1-R, P2Y2-R, P2Y4-R, P2Y6-R, and P2Y11-R, respectively, to promote activation of Gq-regulated phospholipase C was examined in stable 1321N1 human astrocytoma cell lines generated for each one of these receptors (i.e., P2Y1-1321N1, P2Y2-1321N1, P2Y4-1321N1, P2Y6-1321N1, and P2Y11-1321N1 cells). With each cell line, the effects on inositol phosphate accumulation of various concentrations of PPTN were determined in the absence of agonist or in the presence of a concentration of agonist that produced approximately 80% of the maximal stimulation observed with that agonist. No effect of PPTN alone on inositol phosphate accumulation was observed at concentrations up to 10 μM in any of these P2Y receptor–expressing stable cell lines (Fig. 6). Moreover, none of the concentrations of PPTN up to 10 μM affected the capacity of agonists to activate their respective Gq/phospholipase C–linked P2Y receptor.

Fig. 6.

Lack of effect of PPTN at the P2Y1-R, P2Y2-R, P2Y4-R, P2Y6-R, and P2Y11-R. [3H]Inositol phosphate accumulation was determined in P2Y1-1321N1 (red), P2Y2-1321N1 (blue), P2Y4-1321N1 (green), P2Y6-1321N1 (purple), and P2Y11-1321N1 (black) cells in the absence of agonist (open symbols) or in the presence of a concentration of the cognate agonist (closed symbols) for each receptor that produced approximately 70–80% of the maximal effect observed with that agonist. The agonists and their concentrations were 2MeSADP (1 μM), UTP (300 nM), UTP (1 μM), UDP (1 μM), and ATP (100 μM) for the P2Y1-R, P2Y2-R, P2Y4-R, P2Y6-R, and P2Y11-R, respectively. The results are the mean of triplicate determinations and are representative of results of at least three different experiments for each receptor. Typical values for basal and agonist-stimulated [3H]inositol phosphate accumulation were approximately 1000 and 6000 cpm, respectively, for P2Y1-1321N1 cells, approximately 3000 and 10,000 cpm, respectively, for P2Y2-1321N1 cells, approximately 3000 and 14,000 cpm, respectively, for P2Y4-1321N1 cells, approximately 3000 and 25,000 cpm, respectively, for P2Y6-1321N1 cells, and approximately 1000 and 8000 cpm, respectively, for P2Y11-1321N1 cells.

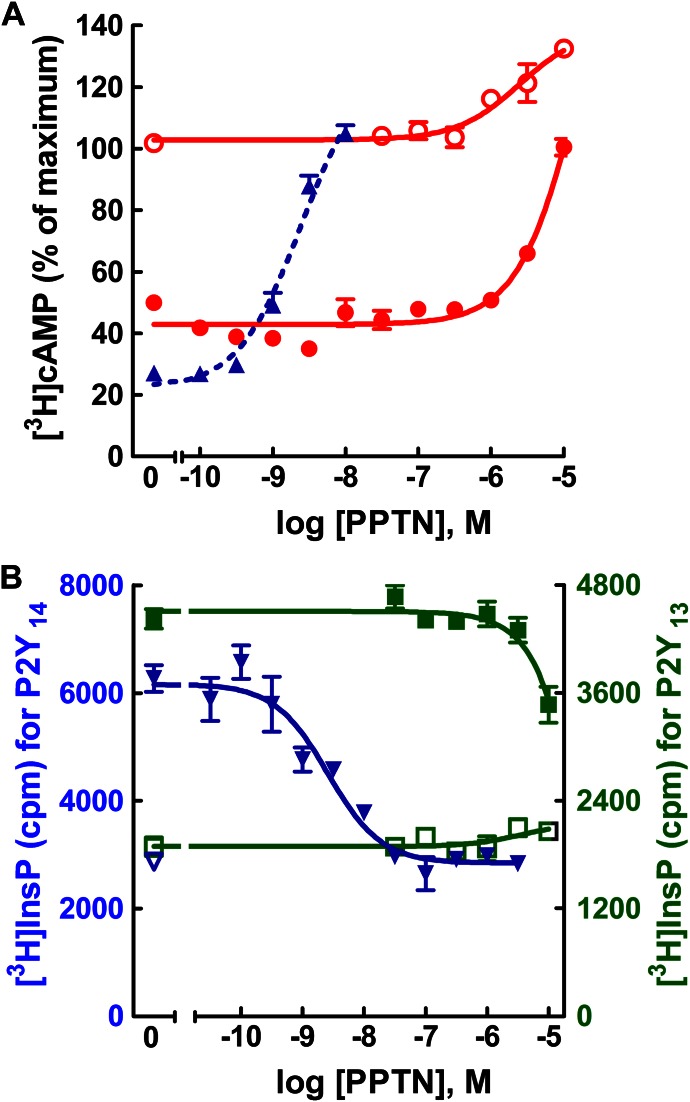

The potential capacity of PPTN to interact with the ADP-activated P2Y12-R and P2Y13-R also was examined. Similar to the P2Y14-R, both of these receptors are Gi-coupled. In the case of the P2Y12-R, a stable cell line is available, and therefore, we tested the potential activity of PPTN to antagonize 2MeSADP-promoted inhibition of adenylyl cyclase in P2Y12-CHO cells. Concentrations of PPTN as high as 1 μM exhibited no effect on forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation in P2Y12-CHO cells (Fig. 7A). Moreover, the capacity of an approximately EC80 concentration of ADP for promoting P2Y12-R–dependent inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation in these cells was not affected by concentrations of PPTN up to at least 1 μM.

Fig. 7.

Lack of effect of PPTN at the P2Y12-R and P2Y13-R. (A) Forskolin (30 μM)–stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation was quantified in P2Y12-CHO cells in the presence of the indicated concentrations of PPTN in the absence (open red circle) or presence (closed red circle) of 1 μM 2MeSADP. The results are the mean of triplicate determinations and are representative of results of at least three different experiments for each receptor. Typical values for basal and forskolin-stimulated [3H]cyclic AMP accumulation in P2Y12-CHO cells were approximately 700 and 4000 cpm, respectively. Data from Fig. 4 were replotted (dotted blue line) to provide a comparative illustration of the concentration-dependent effects of PPTN for antagonizing the effect of 316 nM UDP-glucose at the P2Y14-R. (B) Agonist-stimulated [3H]inositol phosphate accumulation was quantified in the presence of the indicated concentrations of PPTN in the absence (open symbols) or presence (closed symbols) of agonists in COS-7 cells transfected with expression vectors for Gαq/i and the human P2Y13-R (green) or P2Y14-R (blue). The agonists used were 3 μM ADP and 1 μM UDP-glucose for the P2Y13-R and P2Y14-R, respectively. The results are the mean of triplicate determinations and are representative of results of at least three different experiments for each receptor.

No stable cell line for the human P2Y13-R was available, and therefore, we transiently co-expressed the human P2Y13-R in COS-7 cells with a G protein construct Gαq/i that confers capacity of Gi-coupled receptors to activate phospholipase C (Coward et al., 1999). As shown in Fig. 7B, concentrations of PPTN up to 10 μM had no effect on basal inositol phosphate accumulation in these cells. Moreover, PPTN at concentrations as high as 3 μM exhibited no effect on the capacity of an EC80 concentration of 2MeSADP to activate the P2Y13-R. Because the receptor-promoted signaling responses measured in this engineered test system do not occur through components of the native G protein signaling pathway, we also confirmed the antagonist activity of PPTN at the human P2Y14-R in COS-7 cells using the same inositol lipid signaling response system engineered by transient coexpression with Gαq/i. As was observed with quantification of activity in P2Y14-R-C6 cells above, low nM concentrations of PPTN inhibited the capacity of UDP-glucose to promote P2Y14-R–dependent inositol lipid signaling in the COS-7 cell transfection system (Fig. 7B).

Taken together, these studies with recombinant systems shown that PPTN is a potent competitive inhibitor of the P2Y14-R. Conversely, this molecular probe at >1000-fold higher concentrations has no measureable effect on the other seven P2Y receptors.

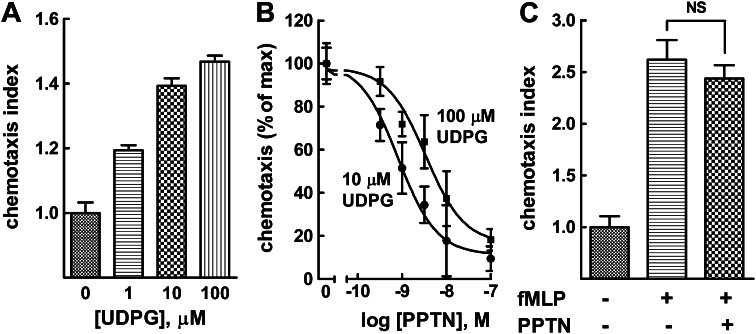

We previously reported that differentiation of HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells results in up-regulation of the P2Y14-R and confers cell signaling responses of these cells to UDP-glucose (Fricks et al., 2009). Moreover, exposure of dHL-60, but not undifferentiated HL-60 cells, to a gradient of UDP-glucose results in chemotaxis (Sesma et al., 2012). Thus, we examined the capacity of PPTN to block UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis of dHL-60 cells with use of a modified Boyden chamber. As we previously reported in detail (Sesma et al., 2012), addition of UDP-glucose to the lower compartment of the chemotaxis chamber resulted in a pronounced migration of dHL-60 cells from the upper chamber (Fig. 8A). The EC50 of UDP-glucose for producing this effect was approximately 1 μM (Sesma et al., 2012; unpublished data). The concentrations shown in Fig. 8A should be considered to be nominal concentrations of agonist for activation of the P2Y14-R in this test system, because the actual concentration of UDP-glucose reaching the cells in the upper chamber is considerably lower. Using this physiologic test system, we examined whether the effects of PPTN acting as a competitive antagonist of the P2Y14-R were recapitulated in measurements of UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis. Addition of PPTN to the upper chamber caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of the effects of 10 and 100 μM UDP-glucose with complete inhibition of agonist-promoted effects observed with approximately 100 nM PPTN (Fig. 8B). Determination of an accurate Ki value for PPTN is not technically feasible in this test system. However, the IC50 values observed for PPTN (∼1 nM in the presence of 10 μM UDP-glucose and ∼4 nM in the presence of 100 μM) are consistent with the relative affinity determined for PPTN by Schild analyses in P2Y14-C6 cells. We also observed that the effect on chemotaxis of adding 10 μM UDP-glucose to the lower chamber was blocked by 100 nM PPTN, irrespective of whether antagonist was added to the upper, lower, or both chambers simultaneously (unpublished data). The selectivity of PPTN in the dHL-60 cell test system was examined by studying its effect on chemotaxis stimulated through activation of another GPCR. Thus, the capacity of fMLP to promote chemotaxis was examined in the presence of 100 nM PPTN. As shown in Fig. 8C, the P2Y14-R antagonist had no significant effect on chemoattractant peptide-promoted chemotaxis.

Fig. 8.

PPTN inhibits UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis in differentiated HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells. (A) Chemotaxis of dHL-60 cells was quantified in the presence of 1, 10, and 100 μM UDP-glucose (UDPG). The agonist was added to the lower compartment of a Boyden chamber. After 2 hours of incubation at 37°C, the fluorescence of the bottom compartment was read and expressed as chemotaxis index (see Materials and Methods). The results are the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments, each one performed in quadruplicate. (B) dHL-60 cells were added to the upper compartment in the presence of the indicated concentrations of PPTN, and chemotaxis index was quantified as above in the presence of either 10 μM or 100 μM UDP-glucose added to the lower compartment. The data are the mean ± S.E.M. of results from three independent experiments, each performed in quadruplicate. (C) The effect of PPTN on fMLP-induced chemotaxis was quantified. Vehicle or 100 nM fMLP was added to the lower compartment, and dHL-60 cells were added with or without 100 nM PPTN to the upper compartment. The results are the mean ± S.E.M. from three separate experiments, each performed in quadruplicate. NS, not significantly different from fMLP alone.

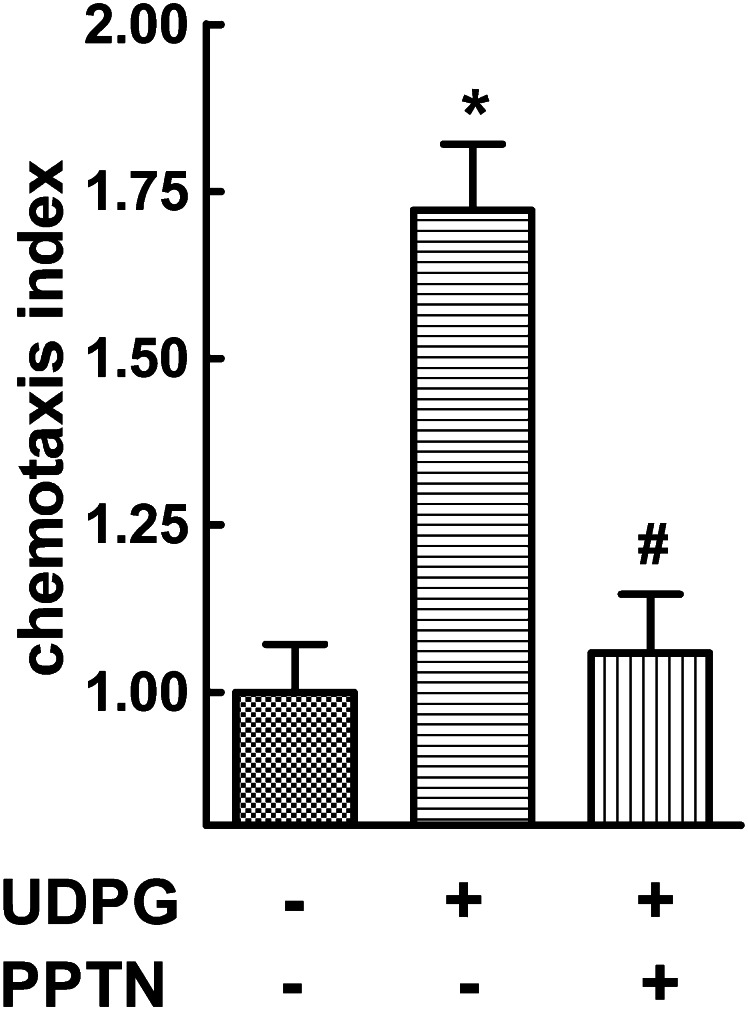

P2Y14-R mRNA is highly expressed in human neutrophils (Chambers et al., 2000; Freeman et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2003), and as we recently demonstrated (Sesma et al., 2012), UDP-glucose promotes activation of Rho, cytoskeletal rearrangement, change of cell shape, and chemotaxis of these cells. Thus, as is shown in Fig. 9, addition of 100 μM UDP-glucose to the lower chamber caused a robust migration of human neutrophils. This effect was largely inhibited by addition of 100 nM PPTN to the upper chamber.

Fig. 9.

PPTN inhibits UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis in human neutrophils. Neutrophil migration was quantified in response to vehicle or 100 μM UDP-glucose (UDPG) added to the lower compartment of a Boyden chamber. Neutrophils were loaded in the upper chamber with or without 10 nM PPTN. The chemotaxis (Ctx) index was quantified after 2 hours, as described in Materials and Methods. The results are the mean ± S.E.M. from three separate experiments, each performed in quadruplicate; (*) and (#), significantly different from vehicle and UDP-glucose, respectively; P < 0.05 by 2-way analysis of variance.

Discussion

The P2Y14-R is increasingly implicated in inflammatory and immune responses, and we reveal here that PPTN is a high-affinity competitive antagonist of this receptor that exhibits strong selectivity for the P2Y14-R over the other seven nucleotide-activated P2Y receptors. PPTN-dependent blockade of UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis of human neutrophils suggests that this molecule or its analogs will be useful for interrogation of P2Y14-R–mediated physiologic responses in vivo.

High-affinity competitive antagonists were developed for the P2Y1-R, and both competitive and noncompetitive antagonists are available for the P2Y12-R. However, such highly selective probes have not been available for the other subtypes of P2Y-R, and thus, the work of Black and colleagues, recently identifying potential antagonist molecules for the P2Y14-R, is promising (Gauthier et al., 2011; Guay et al., 2011; Robichaud et al., 2011). High-throughput screens measuring small molecule–dependent inhibition of UDP-glucose–stimulated Ca2+ mobilization in P2Y14-R–expressing HEK cells identified dihydropyridopyrimidine (Guay et al., 2011) and naphthoic acid–containing (Gauthier et al., 2011) molecules as potential P2Y14-R inhibitors. In both cases, directed synthesis led to molecules that inhibited P2Y14-R–promoted Ca2+ responses in the nanomolar range of concentrations. It was concluded on the basis of lack of inhibition of [3H]UDP binding that the dihydropyridopyrimidine derivatives were noncompetitive inhibitors of the P2Y14-R (Guay et al., 2011). Conversely, several of the naphthoic acid derivatives, including PPTN, inhibited [3H]UDP binding with apparent binding affinities in the low nanomolar range of concentrations (Gauthier et al., 2011; Robichaud et al., 2011). Of interest, one of the highest apparent affinity naphthoic acid derivatives also bound with high affinity to serum proteins, and therefore, PPTN was identified as a naphthoic acid derivative that bound with high apparent affinity to the P2Y14-R but exhibited less robust human serum albumin binding (Robichaud et al., 2011). A prodrug derivative of PPTN (an ester of the carboxylic acid) also was prepared to enhance its bioavailability. Only [3H]UDP binding was used to ascertain the P2Y14-R activity of PPTN, but Gao et al. (2013) recently reported that 10 μM PPTN largely blocked the effect of a synthetic P2Y14-R agonist on β-hexosaminidase release from human LAD2 mast cells. Hamel et al. (2011) also screened a phosphonate library using a [3H]UDP binding assay to identify several molecules that were concluded to bind to the P2Y14-R in the low micromolar range.

We previously showed that UDP-glucose is basally released from C6 glioma and other cell lines. Because of its resistance to ecto-NTDPases, substantial concentrations of this and other nucleotide sugars accumulate in the extracellular medium, and P2Y14-R–dependent cell signaling responses ensue (Lazarowski et al., 2003). Constitutively released nucleotide sugars would be expected to promote P2Y14-R–mediated inhibition of basal and forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in P2Y14-R-C6 cells. Direct comparison of cyclic AMP accumulation in wild-type versus P2Y14-R–expressing C6 cells does not provide a precise quantitative comparison of the extent of the P2Y14-R–dependent effect, but the relative effects observed with PPTN do. That is, whereas PPTN exhibited no effect in wild-type cells, it caused a concentration-dependent elevation of basal and forskolin-stimulated cyclic AMP accumulation in P2Y14-R-C6 cells. The EC50 (3–10 nM) of PPTN observed for elevation of cyclic AMP in the absence of added UDP-glucose was considerably greater than the KB (∼500 pM) of PPTN calculated from Schild analyses with added UDP-glucose. This is consistent with the idea that the majority of the effect of PPTN on cyclic AMP levels in the absence of added agonist occurs because of blockade of the effect of agonist released from the cells into the medium. Our previous studies with the human P2Y14-R transiently overexpressed in Cos-7 cells suggested the occurrence of little if any constitutive activity of the receptor studied under those conditions (Lazarowski et al., 2003), and stable expression of the receptor in P2Y14-R-C6 cells from a viral vector likely results in a lower level of receptor than that attained in Cos-7 cells. However, we cannot rule out unambiguously that constitutive activity of the receptor occurs and that a component of the effect of PPTN in the absence of added UDP-glucose is attributable to inverse agonist activity of this molecule.

Direct measurement of the capacity of PPTN to block the effect of added UDP-glucose on adenylyl cyclase activity in P2Y14-R-C6 cells illustrated a remarkably high affinity of this probe for antagonism of the P2Y14-R. The apparent blockade of the effect of basally released agonist(s) on cyclic AMP accumulation by low concentrations of PPTN also is consistent with the KB value of this molecule determined by Schild analyses. Both UDP and UDP-sugars are cognate agonists of the P2Y14-R, and we show here that the actions of both types of activating ligands are antagonized by PPTN. Obviously, we cannot resolve whether it is UDP, a nucleotide sugar, or both that mediates the basal regulation measured in P2Y14-R-C6 cells; however, PPTN clearly would block the action of both.

The heterocyclic precursor to PPTN was identified in an unbiased screen of a small molecule library, and PPTN bears no obvious resemblance to nucleotides. Thus, we might anticipate that this molecule would exhibit selectivity, if not specificity, for the P2Y14-R over other P2Y receptors. A three-dimensional structure of the agonist binding pocket is not yet available for any of the P2Y receptors. However, given the similarity of the nucleotide ligands of these receptors, their orthosteric binding sites almost certainly will show structural overlap. This may be particularly true for the P2Y14-R relative to other subtypes of the Gi-coupled P2Y12-R subgroup of P2Y receptors. This subgroup includes the P2Y12-R, P2Y13-R, and P2Y14-R, which exhibit relatively high (40–50%) sequence identity overall and contain membrane-spanning regions that are particularly highly conserved. Thus, it was important to establish the selectivity of PPTN, and its lack of activity observed here at any of the P2Y receptors, including the other two subtypes of the P2Y12-R subgroup, bodes well for its application as a selective molecular probe of the P2Y14-R. This selectivity is of obvious importance for in vivo studies, but cultured cell lines also predictably express multiple P2Y-R subtypes.

The high level expression of mRNA for P2Y14-R in neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages is consistent with a function for this signaling protein in immune and inflammatory responses (Chambers et al., 2000; Freeman et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2003). Early studies proposed a role for the P2Y14-R in chemotaxis of hematopoietic stem cells (Lee et al., 2003), and although Arase and coworkers (2009) were unable to illustrate effects of UDP-glucose on chemotaxis of neutrophils, they showed that the P2Y14-R played a key role in the innate mucosal immunity response of the female reproductive tract. More recently, we directly showed that the P2Y14-R promotes Rho-mediated signaling and chemotaxis in human neutrophils (Sesma et al., 2012), and Xu and coworkers (2012) revealed that high-fat diet-induced inflammatory responses of the liver are markedly reduced in P2Y14-R(−/−) mice (Xu et al., 2012). UDP-glucose increased migration of macrophages isolated from wild-type mice, but had no effect in P2Y14-R knock-out animals. Furthermore, the high-fat diet resulted in insulin resistance, and this effect was lessened in P2Y14-R(−/−) mice. Thus, a number of lines of investigation now indicate an important role for extracellular nucleotide sugars and P2Y14-R in innate immunity responses.

UDP-glucose is released concomitantly with mucins (Hirschberg et al., 1998) from airway epithelial goblet (mucous) cells (Kreda et al., 2007; Okada et al., 2011), and chronic lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, asthma, and chronic obstructive lung disease, are characterized by mucin hypersecretion and inflammation. Potentially relevant to airway inflammation, UDP-glucose levels in lung secretions (i.e., bronchoalveolar lavage fluids) from patients with cystic fibrosis are in the range of concentrations that promote robust activation of the P2Y14-R (Sesma et al., 2009). Thus, the pharmacological activity and selectivity of PPTN for the P2Y14-R delineated here using recombinant cell systems indicates that this molecule should prove to be useful for interrogation of the physiologic roles of the P2Y14-R in lung inflammation in vivo. This notion is made more tangible by our observation that PPTN blocks UDP-glucose–promoted chemotaxis of human neutrophils and does so across a concentration range consistent with its KB determined in the P2Y14-R–expressing cell line.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Robert Nicholas, Terry Kenakin, and Evgeny Kiselev for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- 2MeSADP

2-methylthio-adenosine 5′-diphosphate

- DID

1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine perchlorate

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- fMLP

formyl-Met-Leu-Phe

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HBSS

Hanks' balanced salt solution

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- MRS2906

2-thiouridine-5′-diphosphate β-ethyl ester

- P2Y-1321N1 cells

1321N1 human astrocytoma cells stably expressing the indicated human P2Y receptor

- P2Y14-C6 cells

C6 rat glioma cells stably expressing the human P2Y14 receptor

- P2Y12-CHO cells

Chinese hamster ovary cells stably expressing the human P2Y12 receptor

- P2Y1-R

P2Y1 receptor, P2Y2-R, P2Y2 receptor

- P2Y4-R

P2Y4 receptor

- P2Y6-R

P2Y6 receptor

- P2Y11-R

P2Y11 receptor

- P2Y12-R

P2Y12 receptor

- P2Y13-R

P2Y13 receptor

- P2Y14-R

P2Y14 receptor

- PPTN

4-((piperidin-4-yl)-phenyl)-7-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)-2-naphthoic acid

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Barrett, Jacobson, Lazarowski, Harden.

Conducted experiments: Barrett, Sesma, Ball.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Jayasekara, Jacobson.

Performed data analysis: Barrett, Sesma, Ball.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Barrett, Sesma, Jacobson, Lazarowski, Harden.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant GM38213]; the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant HL34322]; and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health [National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases].

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Knight GE, Fumagalli M, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, et al. (2006) International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev 58:281–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arase T, Uchida H, Kajitani T, Ono M, Tamaki K, Oda H, Nishikawa S, Kagami M, Nagashima T, Masuda H, et al. (2009) The UDP-glucose receptor P2RY14 triggers innate mucosal immunity in the female reproductive tract by inducing IL-8. J Immunol 182:7074–7084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belly M, Deschenes D, Fortin R, Fournier JF, Gagne S, Gareau Y, Gautheir JY, Li L, Robichaud J, Therien M, Tranmer GK, and Wang Z (2009) inventors, Merck Frosst Canada LTD, assignee. Substituted 2-naphthoic acids as antagonists of GPR105 activity. WO 2009/070873A1. 2010 Nov 25.

- Boger DL, Han N, Tarby CM, Boyce CW, Cai H, Jin Q, Kitos PA. (1996) Synthesis, chemical properties, and preliminary evaluation of substituted CBI analogs of CC-1065 and the duocarmycins incorporating the 7-cyano-1,2,9,9a-tetrahydrocyclopropa[c]benz[e]indol-4-one alkylation subunit: Hammett quantitation of the magnitude of electronic effects on functional reactivity. J Org Chem 61:4894–4912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HA, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC, Harden TK. (1991) Evidence that UTP and ATP regulate phospholipase C through a common extracellular 5′-nucleotide receptor in human airway epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol 40:648–655 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. (2007) Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev 87:659–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RL, Fricks IP, Barrett MO, Burianek LE, Zhou Y, Ko H, Das A, Jacobson KA, Lazarowski ER, Harden TK. (2009) Quantification of Gi-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity reveals that UDP is a potent agonist of the human P2Y14 receptor. Mol Pharmacol 76:1341–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JK, Macdonald LE, Sarau HM, Ames RS, Freeman K, Foley JJ, Zhu Y, McLaughlin MM, Murdock P, McMillan L, et al. (2000) A G protein-coupled receptor for UDP-glucose. J Biol Chem 275:10767–10771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward P, Chan SD, Wada HG, Humphries GM, Conklin BR. (1999) Chimeric G proteins allow a high-throughput signaling assay of Gi-coupled receptors. Anal Biochem 270:242–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Ko H, Burianek LE, Barrett MO, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. (2010) Human P2Y14 receptor agonists: truncation of the hexose moiety of uridine-5′-diphosphoglucose and its replacement with alkyl and aryl groups. J Med Chem 53:471–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K, Tsui P, Moore D, Emson PC, Vawter L, Naheed S, Lane P, Bawagan H, Herrity N, Murphy K, et al. (2001) Cloning, pharmacology, and tissue distribution of G-protein-coupled receptor GPR105 (KIAA0001) rodent orthologs. Genomics 78:124–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricks IP, Maddileti S, Carter RL, Lazarowski ER, Nicholas RA, Jacobson KA, Harden TK. (2008) UDP is a competitive antagonist at the human P2Y14 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325:588–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricks IP, Carter RL, Lazarowski ER, Harden TK. (2009) Gi-dependent cell signaling responses of the human P2Y14 receptor in model cell systems. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 330:162–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZG, Wei Q, Jayasekara MP, Jacobson KA. (2013) The role of P2Y14 and other P2Y receptors in degranulation of human LAD2 mast cells. Purinergic Signal 9:31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier JY, Belley M, Deschênes D, Fournier JF, Gagné S, Gareau Y, Hamel M, Hénault M, Hyjazie H, Kargman S, et al. (2011) The identification of 4,7-disubstituted naphthoic acid derivatives as UDP-competitive antagonists of P2Y14. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 21:2836–2839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guay D, Beaulieu C, Belley M, Crane SN, DeLuca JC, Gareau Y, Hamel M, Henault M, Hyjazie H, Kargman S, et al. (2011) Synthesis and SAR of pyrimidine-based, non-nucleotide P2Y14 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 21:2832–2835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel M, Henault M, Hyjazie H, Morin N, Bayly C, Skorey K, Therien AG, Mancini J, Brideau C, Kargman S. (2011) Discovery of novel P2Y14 agonist and antagonist using conventional and nonconventional methods. J Biomol Screen 16:1098–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden TK, Scheer AG, Smith MM. (1982) Differential modification of the interaction of cardiac muscarinic cholinergic and beta-adrenergic receptors with a guanine nucleotide binding component(s). Mol Pharmacol 21:570–580 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden TK, Sesma JI, Fricks IP, Lazarowski ER. (2010) Signalling and pharmacological properties of the P2Y14 receptor. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 199:149–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberg CB, Robbins PW, Abeijon C. (1998) Transporters of nucleotide sugars, ATP, and nucleotide sulfate in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Annu Rev Biochem 67:49–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Jayasekara MPS, Costanzi S. (2012) Molecular structure of P2Y receptors: mutagenesis, modelling and chemical probes. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Membr Transp Signal 1:815–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreda SM, Okada SF, van Heusden CA, O’Neal W, Gabriel S, Abdullah L, Davis CW, Boucher RC, Lazarowski ER. (2007) Coordinated release of nucleotides and mucin from human airway epithelial Calu-3 cells. J Physiol 584:245–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Shea DA, Boucher RC, Harden TK. (2003) Release of cellular UDP-glucose as a potential extracellular signaling molecule. Mol Pharmacol 63:1190–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Sesma JI, Seminario-Vidal L, Kreda SM. (2011) Molecular mechanisms of purine and pyrimidine nucleotide release. Adv Pharmacol 61:221–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecut C, Frederix K, Johnson DM, Deroanne C, Thiry M, Faccinetto C, Marée R, Evans RJ, Volders PG, Bours V, et al. (2009) P2X1 ion channels promote neutrophil chemotaxis through Rho kinase activation. J Immunol 183:2801–2809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BC, Cheng T, Adams GB, Attar EC, Miura N, Lee SB, Saito Y, Olszak I, Dombkowski D, Olson DP, et al. (2003) P2Y-like receptor, GPR105 (P2Y14), identifies and mediates chemotaxis of bone-marrow hematopoietic stem cells. Genes Dev 17:1592–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, Murdock PR, Watson JM, Faull RL, Waldvogel HJ, Szekeres PG, Wilson S, Freeman KB, Emson PC. (2003) GPR105, a novel Gi/o-coupled UDP-glucose receptor expressed on brain glia and peripheral immune cells, is regulated by immunologic challenge: possible role in neuroimmune function. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 118:10–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas RA, Watt WC, Lazarowski ER, Li Q, Harden K. (1996) Uridine nucleotide selectivity of three phospholipase C-activating P2 receptors: identification of a UDP-selective, a UTP-selective, and an ATP- and UTP-specific receptor. Mol Pharmacol 50:224–229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada SF, Zhang L, Kreda SM, Abdullah LH, Davis CW, Pickles RJ, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. (2011) Coupled nucleotide and mucin hypersecretion from goblet-cell metaplastic human airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 45:253–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi AD, Kennedy C, Harden TK, Nicholas RA. (2001) Differential coupling of the human P2Y11 receptor to phospholipase C and adenylyl cyclase. Br J Pharmacol 132:318–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Burnstock G. (1998) Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 50:413–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robichaud J, Fournier JF, Gagné S, Gauthier JY, Hamel M, Han Y, Hénault M, Kargman S, Levesque JF, Mamane Y, et al. (2011) Applying the pro-drug approach to afford highly bioavailable antagonists of P2Y14. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 21:4366–4368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon Y, Londos C, Rodbell M. (1974) A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal Biochem 58:541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter JB, Li Q, Boyer JL, Nicholas RA, Harden TK. (1996) Second messenger cascade specificity and pharmacological selectivity of the human P2Y1-purinoceptor. Br J Pharmacol 118:167–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrivens M, Dickenson JM. (2006) Functional expression of the P2Y14 receptor in human neutrophils. Eur J Pharmacol 543:166–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesma JI, Esther CR, Jr, Kreda SM, Jones L, O'Neal W, Nishihara S, Nicholas RA, Lazarowski ER. (2009) Endoplasmic reticulum/golgi nucleotide sugar transporters contribute to the cellular release of UDP-sugar signaling molecules. J Biol Chem 284:12572–12583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesma JI, Kreda SM, Steinckwich-Besancon N, Dang H, García-Mata R, Harden TK, Lazarowski ER. (2012) The UDP-sugar-sensing P2Y14 receptor promotes Rho-mediated signaling and chemotaxis in human neutrophils. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303:C490–C498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelton L, Cooper M, Murphy M, Platt A. (2003) Human immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells express the G protein-coupled receptor GPR105 (KIAA0001, P2Y14) and increase intracellular calcium in response to its agonist, uridine diphosphoglucose. J Immunol 171:1941–1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan KR, Stokes L, Prince LR, Marriott HM, Meis S, Kassack MU, Bingle CD, Sabroe I, Surprenant A, Whyte MK. (2007) Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by ATP is mediated by the P2Y11 receptor. J Immunol 179:8544–8553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese MW, Kneisler TB, Boucheron JA. (1996) P2U agonists induce chemotaxis and actin polymerization in human neutrophils and differentiated HL60 cells. J Biol Chem 271:15597–15601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Morinaga H, Oh D, Li P, Chen A, Talukdar S, Mamane Y, Mancini JA, Nawrocki AR, Lazarowski E, et al. (2012) GPR105 ablation prevents inflammation and improves insulin sensitivity in mice with diet-induced obesity. J Immunol 189:1992–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Küglegen V, Harden TK. (2012) Molecular pharmacology, physiology, and structure of the P2Y receptors. Adv Pharmacol 61:373–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H. (2000) Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 362:299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.