Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To describe the implementation and acceptability of the TRaining In the Assessment of Depression (TRIAD) intervention, which has been tested in a randomized trial. The primary aim of TRIAD is to improve the ability of homecare nurses to detect depression in medically ill, older adult homecare patients.

DESIGN

Description of the important components of TRIAD, its implementation, and evaluation results from nurse surveys.

SETTING

Three certified home healthcare agencies in Westchester County, New York.

PARTICIPANTS

Thirty-six homecare nurses.

INTERVENTION

Participants randomly assigned to TRIAD (n = 17) were provided with the opportunity to observe and practice patient interviewing. The approach focused on clinically meaningful identification of the two “gateway” symptoms of depression and is consistent with the newly revised Medicare mandatory Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS-C). Control group participants (n = 19) received no training beyond that which agencies may have provided routinely.

MEASUREMENTS

Baseline and 1-year nurse confidence in depression detection, and postintervention acceptability ratings of the TRIAD intervention.

RESULTS

Participants randomized to the TRIAD intervention reported a statistically significant increase in confidence in assessing for depression mood (P<.001), whereas the usual care group’s confidence remained unchanged (P = .34) 1 year later.

CONCLUSION

An educational program designed to improve depression detection by giving nurses the skills and confidence to integrate depression assessment into the context of routine care can be successfully implemented with homecare agency support. The authors discuss the intervention in terms of OASIS-C and the “real world” realities of intervention implementation.

Keywords: depression, education, nursing, home health care, recognition

Depression remains a significant public health problem for older adults in all service sectors (hospitals, primary care, long-term care).1,2 The failure to detect and adequately treat depression is associated with higher costs,3 morbidity, risk of suicide, and mortality from other causes,1,2 but depression is a treatable condition.4–6 Guidelines based on evidence from pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy,7 and care models for the primary care setting have been established,8 but there has been little research on practical approaches to operationalizing depression detection or treatment for the homecare setting.9 There is a substantial need for depression research in homecare, with major depression twice as common in older adults receiving homecare services10 as in those receiving primary care.11 A previous study found that 13.5% of subjects newly admitted to homecare suffered from major depression,10 that depression often remained unrecognized,12,13 and that few (12%) received adequate treatment. 10

The aim of the TRaining In the Assessment of Depression (TRIAD) intervention14 is to address inadequacies and improve routine depression case finding in older adult patients by homecare nurses. The U.S. Preventive Task Force15 recommends that all individuals aged 60 and older should be screened for depression periodically, and evidence-based nursing practice guidelines call for nurse depression screening.16,17 A few investigators have focused on the homecare nurse’s ability to implement such screening.14,18–20 The rationale for leveraging the role of homecare nurses includes their frequent and regular contact with patients. In Medicare-certified agencies, homecare nurses provide the vast majority (85%) of skilled care21 and are mandated to perform patient assessments periodically, including assessment for depression symptoms, yet homecare nurses do not feel adequately prepared22 and often fail to identify depression.12,13 Homecare nurses have expressed concerns about “asking direct questions about depression,” “invasion of patient privacy,” “precipitating patient distress (e.g., suicide ideation),” and the added paperwork burden required for screening activities.20 In addition, agencies may lack the supportive infrastructure to improve depression case finding.

In a randomized trial,14 TRIAD was found to be a successful intervention. Specifically, it was found that nurses who received the TRIAD were 2.5 times as likely to correctly identify depressed patients and refer them for further evaluation, following agency protocols, and that referrals led to better clinical outcomes. There was no effect on unnecessary referrals for research-confirmed patients without depression (i.e., the intervention did not promote false-positive referrals).

To promote dissemination of a proven effective intervention, this article describes in more detail the rationale, development, and use of TRIAD as it was implemented in a randomized controlled trial.14 It describes partnership activities with participating homecare agencies, needs assessment surveys, shadowing activities, and the content of the training curriculum and reports on nurses’ acceptance of the TRIAD intervention to develop their confidence in conducting depression detection, before and after the intervention.

METHODS

Development of the Intervention

TRIAD was developed in collaboration with three partnering homecare agencies using an evidence-based community partnership model.23 The Weill Cornell Homecare Research Partnership’s approach to developing the depression assessment training consisted of multiple modalities, including surveys22 and shadowing activities conducted with funding from a National Institute of Mental Health Interventions and Practice Research Infrastructure Program Grant (primary investigator, MLB).

A survey to determine homecare nurses’ readiness to approach geriatric depression detection was developed and administered to 134 full-time and part-time registered nurses employed at the three partnering homecare agencies (participation rate 99%). The survey indicated that the majority of nurses were aware of the problem of geriatric depression but were not confident in their ability to detect symptoms of depression. Results22 provided evidence that there was a discrepancy between nurse’s self-perceived ability to detect depression and their understanding that depression in older adults was a medical problem to be addressed.

To help the researchers better understand how nurses assess patients in medical, functional, and mental health–related domains, agencies invited researchers to shadow nurses in the field. Directly observing agency operations and nurses in the field provided information about the realities of depression recognition in a medically ill, homebound older population. Potential agency pressure points and untapped opportunities to improve recognition and referral of suspected cases were also identified. These observations informed the development of the TRIAD in a number of specific ways. For example, it was observed that nurses often depended primarily on their own observations in assessing depression symptoms and seldom asked directly about symptoms, which is consistent with other reports.20 Additionally, nurses and agency leadership were resistant to adding standardized assessments to the perceived already-burdensome documentation requirements.

Survey findings, nurse shadowing, and ongoing discussion with the agency’s staff helped provide a clear focus for the content of the developing intervention. It was decided that to improve depression recognition, TRIAD should improve the ability of the homecare nurse to identify the two cardinal symptoms of depression and make appropriate referrals for further evaluation of a suspected case of depression in accordance with agency procedures. At the same time, TRIAD should not increase the amount of assessment or documentation already required of nurses.

To balance workload concerns with the need to improve depression screening, the Partnership chose to use the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) as a framework for screening for and documenting depressive symptoms. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services requires Medicare-certified homecare agencies to collect OASIS data periodically when evaluating all adult, nonpregnant patients as part of a comprehensive assessment. The OASIS includes specific depression items scored on a presence versus absence basis but without any guidance on how to assess these symptoms.

It was determined through collaboration with agency partners that using routine care as a framework would increase the feasibility and uptake of this screening approach. Nurses would be less likely to view use of OASIS as another task but rather as an enhancement of an assessment already performed.

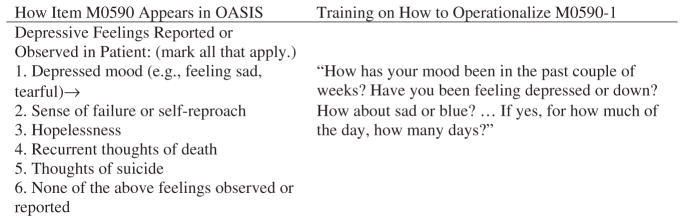

The OASIS items include the “gateway” symptoms of major depression, as specified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)24 (depressed mood and diminished interest or pleasure in most activities; optional OASIS item). In this respect, these two items are comparable to the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-2, as recommended by the U.S. Preventive Task Force,15 and to other depression screens.25,26 Because OASIS does not provide screening questions or guidance on how to assess for depressive symptoms, nurses were trained to ask specific standardized questions for the detection of depressed mood (Figure 1) and diminished interest or pleasure in most activities. When symptoms were evident, nurses were trained to evaluate whether symptoms were clinically meaningful by asking follow-up questions on their persistence and pervasiveness (How long? How much of the day?). Symptoms were recorded as present only when they met DSM-IV severity criteria of “being present for at least two weeks and most of the day, nearly every day.”

Figure 1.

Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) item M0590 and training approach to assessment of depression symptoms. Source: 1998, Center for Health Services and Policy Research, UCHSC, Denver CO, OASIS-B1 SOC.

Nurses’ lack of confidence in assessing suicidal ideation was another concern that agency staff and nurses raised. Asking about these thoughts is an essential component of providing depression care, as well as a component of the OASIS assessment (recurrent thoughts of death and thoughts of suicide), but posing questions about suicide can be difficult. Therefore, the authors worked with the agencies, at their request, to develop procedures for assessing level of suicide risk. In TRIAD, specific questions that allow nurses to make judgments about successive levels of suicide risk are provided, along with corresponding action plans. Pilot testing and refinement of the intervention occurred at two of the partnering agencies that had multiple sites.

Implementation of the TRIAD

The core educational TRIAD intervention was 4.5 hours long and was divided into two sessions, 1 month apart, when implemented in the randomized trial.14 The intervention also included, if not already in place, the modification of the homecare agency’s procedures to support depression detection and referral procedures. TRIAD was designed to be delivered by a nurse, psychologist, social worker, or medical doctor knowledgeable about geriatric depression and barriers to recognition and referral in the homecare setting. Both instructors for the TRIAD training trial14 (nurse educator; ELB and psychologist; PJR) had spent time developing the intervention, piloting it, and learning from the staff at the partnering agencies. The following paragraphs provide the rationale for each TRIAD component and describe how the intervention was implemented in the trial.14

The TRIAD intervention incorporated instructional strategies with demonstrated effectiveness in continuing education, including the opportunity to observe the desired behavior change, active learning, multiple sessions, and reminders.27–29 To engage nurses, realistic videotaped patient encounters were provided that presented a general approach to patient interviewing, with several nurse–patient interactions that portray symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation in ethnically diverse patient actors.30 These vignettes were developed based on experience conducting hundreds of in-home patient interviews for a previous epidemiological study10 and from interviewing homecare nurses about detecting depression.12 The videotaped patient encounters also demonstrated patient interviewing and assessment in the context of medical illness, disability, pain, anxiety, and worry. In the two-session training, there were several opportunities for nurses to practice patient interviewing and depression assessment and receive instructor feedback. The decision to provide the intervention over two sessions was based on the amount of content, the need for nurses to have the opportunity to ask questions of the instructors after attempting new skills, and the finding that multiple sessions are more effective in providing continuing professional education.29,31

Table 1 provides an overview of the topics covered and corresponding instructional strategies used. Session 1 began with a true–false test used as a warm-up exercise and included a class discussion focusing on myths about aging and the medical illness of depression. Next, a brief lecture was provided describing major depression. Although the lecture as a teaching strategy has become less accepted in favor of active learning methods, it was felt that it was important to provide a foundation and motivation for the target behavior: assessment of depression.32

Table 1.

Topics and Corresponding Teaching Strategies: Trial of Depression Assessment14

| Session and Topic | Teaching Strategy |

|---|---|

| I. | |

| Dispelling myths about depression, education about stigma, and agism in depression detection. → | Test (warm-up exercise) and review of responses and rationale |

| Major depression (prevalence, diagnostic criteria, etiology, consequences, treatment) in older adults. → | Lecture with Power Point slides |

| Depression assessment, suicide risk assessment, and patient interviewing → | Videotape of patient–nurse interactions, role-play exercise, depression tool kit,* and field trial assignment discussed |

| II. | |

| Barriers to approaching depression detection and referrals of suspected cases → | Discussion and debriefing from field trial assignment |

| Review of depression assessment and suicide risk assessment → | Videotape of patient–nurse interactions and participation in a self-test of depression assessment skill |

| Agency policy and procedures for making a referral for a suspected depression case to the psychiatric nurse and assessing suicide risk → | Discussion led by agency representative |

TRaining in the Assessment of Depression tool kit included depression assessment interview questions, patient and family educational materials, treatment considerations for older adults, antidepressant medication overview, guide to working with patients with depression and making a mental health referral, a glossary of important terminology, guide for assessment of suicidal ideation, and Web links to additional resources.30,37

In the TRIAD intervention, nurses were instructed to use clinical judgment by evaluating behavioral signs, as well as patient reports on the presence and persistence of depressive symptoms. For example, some patients may deny depressed mood (in one depiction the patient states: “Depressed? I don’t get depressed!”) but may nonetheless show behavioral signs of depression such as downcast expression or becoming teary when discussing their life circumstances. Nurses were trained to sensitively probe for depressed mood in these cases by calling the client’s attention to their nonverbal behavior. To achieve a pragmatic balance between sensitivity and specificity, nurses were taught to ask follow-up questions about the duration and persistence of symptoms as evidence of clinical relevance. A recurrent theme of this program was the need for direct, focused probing of depression symptoms. By training nurses to ask standardized clinical questions that could be modified to fit the language of the patient, this approach was adaptable across diverse populations. This training was particularly important given previous findings that nurses are reluctant to talk about depression with culturally diverse patients.20

At the end of the first session, nurses were encouraged to practice the depression assessment interviewing skills (field trial assignment) before the second session. Additionally, a depression tool kit was provided that included the important components of the intervention so that what was learned could be seamlessly brought into practice (note, Table 1).

The second educational session began with a debriefing session. The nurses were asked about their experiences in implementing the depression screening. When instructors encouraged the group to problem solve and discuss alternative strategies in approaching and conducting depression screening, they were confronted with a variety of reasons why nurses were hesitant to conduct depression screening. A common concern that nurses voiced was that, “I am not a psychiatric nurse, so how can I perform depression screening?” Nurses also expressed concern about upsetting patients and families when discussing mental health concerns and consequently often relied solely on observation rather than direct questioning. When this concern was voiced, it was attempted to elicit nurse experiences from the group in which patients felt comforted and cared for when asked questions about mental health in a sensitive manner, as opposed to becoming upset. This approach fostered social reinforcement and support among the nurses in asking directly about symptoms. E-mail reminders were provided 4 and 8 months after the training. These brief reminders focused on the importance of identification (reminder 1) and the value of adequate depression treatment (reminder 2). Content for these reminders was taken directly from the training program.

Intervention Evaluation

As described elsewhere,14 nurse participants in the TRIAD trial were recruited from the three partnering agencies through small group meetings. Nurses employed a minimum of 20 hours per week and who provided written consent were randomly assigned to the intervention (TRIAD, n = 17) or to a usual care comparison condition (n = 19), which received no training beyond that which agencies may have previously provided routinely. The patient population served by these agencies was predominantly medically ill older adults and was representative of the national home-care population.21

This article reports on survey findings for the nurses randomly assigned to the TRIAD intervention and the usual care comparison group. Surveys were administered to nurses participating in the TRIAD trial14 before (baseline) and after (1 year after the first TRIAD training session) the intervention. The surveys gathered demographic data, assessed perceived confidence related to depression assessment skill, and determined postintervention acceptability of the intervention. Survey items were developed in collaboration with the partnering agencies and were pilot tested for understandability.

Nurses were queried about their self-confidence in assessing for depressed mood and diminished interest or pleasure in most activities using a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = very uncertain to 4 = very certain). Nurses were asked to answer the questions, “How certain do you feel you can assess for depressed mood (OASIS item) in the older adult? and “How certain do you feel you can assess for diminished interest or pleasure in most activities in the older adult? Additionally, immediately after the second (final) TRIAD session, intervention nurses were asked whether the program content met the program objectives and whether the information presented could be directly applied to their practice.

In evaluating different nursing behavior between the two groups (intervention and usual care), a two-sample t-test for means was conducted for continuous variables, and a chi-square test or Fisher exact test was conducted for categorical variables. When reviewing differences at baseline and after training, pair-wise t-tests were conducted to determine statistical significance. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Nurse surveys at baseline and 1 year were available for 15 of 17 nurses who participated in the TRIAD intervention and 14 of 19 nurses in the usual care group.14 All of the participants were registered nurses, were female, and typical of the aging nurse work force, had an average age in the mid-40s.33 There were no statistically significant differences in demographics, nursing experience, or education between the intervention and usual care groups (Table 2). All of the intervention nurses completed the two-session educational program.

Table 2.

Baseline Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics of Homecare Nurses According to Randomized Group Assignment (n = 29)

| Characteristic | TRaining In the Assessment of Depression (n = 15) | Usual Care (n = 14) | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD (range 25–62) | 44.9 ± 9.3 | 47.1 ± 11.7 | .56 |

| Female, n (%) | 15 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 12 (80.0) | 10 (78.6) | .29† |

| African American | 1 (6.7) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Asian | 1 (6.7) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Other | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Highest educational attainment, n (%) | |||

| Baccalaureate degree | 7 (46.6) | 8 (57.2) | .25§ |

| Master’s degree | 2 (13.4) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Associate degree | 5 (33.5) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Other‡ | 1 (6.7) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Years since obtaining nursing license, mean ± SD (range 2–41 years) | 20.4 ± 12.0 | 19.5 ± 11.7 | .83 |

P-values based on t-test, chi-square test, or Fisher exact test.

Fisher exact test; first group (Caucasian) versus others.

Diploma program and other.

Fisher exact test; baccalaureate and master’s degree versus others.

SD = standard deviation.

At baseline, the two groups of nurses shared the same level of certainty regarding their ability to assess for depressed mood. On average, the usual care group scored 2.6 ± 0.8 (1 = very uncertain to 4 = very certain), and the intervention nurses scored 2.6 ± 0.7. One year later, the intervention group displayed a statistically significant increase in confidence (3.3 ± 0.6; degrees of freedom (df) = 14, t = 4.18, P<.001), whereas the usual care group’s confidence remained unchanged (2.8 ± 0.6; df = 13, t = 1.00, P = .34). Likewise, both groups of nurses shared a similar level of certainty in assessing for diminished interest or pleasure in most activities at baseline (mean 2.6 ± 0.8 for the usual care group, mean = 2.7+0.7 for the intervention group; df = 27, t = 0.75, P = .46). One year later, the intervention nurses showed a statistically significant increase in confidence in assessing for diminished interest or pleasure in most activities (3.1 ± 0.8; df = 14, t = 2.17, P = .048), whereas the usual care group remained unchanged (2.7 ± 0.5; df = 13, t = 0.37, P = .72). Furthermore, nine of 15 intervention nurses reported an improvement in confidence in assessing depressed mood 1 year later, versus only four of 14 usual care group nurses (Fisher exact test P = .07). In assessing for diminished interest or pleasure in most activities, eight of 15 intervention group nurses reported improved confidence, versus two of 14 usual care nurses (Fisher exact test P = .03).

All nurses (n = 15) in the intervention group evaluated the TRIAD intervention using a brief questionnaire with closed-ended questions. Nurses were queried, “In your opinion, were the program objectives achieved (i.e., to improve the ability of the nurse to identify cardinal symptoms of depression and make appropriate referrals for further evaluation of a suspected case of depression)?” (response choices: yes or no). All of the nurses reported that these two primary objectives were achieved, and all believed that the content was consistent with the course objectives. In response to the query, “Can the information presented be applied in your practice?” (response choices: yes, somewhat, or no), 14 nurses responded “yes,” and one responded “somewhat.”

Since the conclusion of the trial, TRIAD has been successfully used to train nurses, social workers, physical therapists, speech therapists, and occupational therapists.34 It has been disseminated to 17 homecare agencies in nine states with diverse populations. The TRIAD program has been accredited for continuing nursing education and positively reviewed by a geriatric nursing journal.35

DISCUSSION

As previously reported in a randomized controlled trial, a 4.5-hour intensive skill-building intervention in assessment and detection of symptoms of geriatric depression for homecare nurses has been developed and implemented.14 In addition, it has been shown that this intervention improves geriatric depression detection and increases appropriate depression referrals, leading to better patient outcomes. This article describes the rationale for each of the important components of the intervention and how the intervention was implemented in the randomized controlled trial. Survey results indicated that participating nurses found TRIAD acceptable and that the relative confidence of nurses in conducting depression screening increased 1 year after the core training sessions.

Nurses were trained to use the depression sections of the OASIS in a clinically meaningful way, as opposed to adding a standardized depression screen to the OASIS. Input from nurses and administrators overwhelmingly emphasized concerns about increasing actual or perceived burden of their assessment requirement. For these reasons, measures such as the Geriatric Depression Scale or even the PHQ-2, which also assesses the two gateway symptoms of depressed mood and anhedonia, were not introduced, because the scoring systems were inconsistent with the OASIS yes versus no scoring.

Medicare’s newly revised OASIS (OASIS-C), which is scheduled to be put into practice January 2010,36 has streamlined many assessments but enhanced the section on depression. The OASIS-C queries nurses as to whether a standardized approach (e.g., the TRIAD) has been used to assess depressive symptoms and provides the PHQ-2 as a specific alternative. As agencies begin to use the OASIS-C, the scoring structure and specific language of the PHQ-2 questions are now integrated into the training, and new vignettes have been filmed to support this option, but despite the standardized wording offered by the PHQ-2, nurses continue to benefit from assessment training given the complex medical, cognitive, and functional status of these patients, as well as the attitudes and beliefs that many nurses have about depression.

A number of steps have been taken to disseminate TRIAD. A detailed facilitator’s instructional guide has been developed, “train the trainer” sessions have been conducted, and a Web-based module has been developed with the expertise of an e-learning production team.37 The accessible Web-based module37 includes the TRIAD depression tool kit and core content of the educational program. The Web-based version can be used to supplement active learning activities (role play, field assignment) and reinforce or refresh training. This module has not been evaluated as a stand-alone intervention, and therefore it is recommended that these materials be used as a component of faculty-led, in-person training.

In implementing TRIAD, a number of considerations are indicated. First, the content underlying this program is based on the premise that agencies will modify their procedures to support depression detection and referral procedures. An instructor knowledgeable about geriatric depression and the homecare setting is required to implement this program. Finally, the TRIAD program is primarily a depression recognition, skills-building program that requires availability of a primary care provider with training or expertise in managing psychological problems or a mental health expert to evaluate suspected cases of depression after positive screens.

In summary, improving referral of suspected cases of geriatric depression can be achieved in the homecare setting using a brief educational program designed to give nurses the skills and confidence to integrate depression assessment into the context of routine care and with agency support. This educational program provides a platform for planning future programs focused on depression care in the home-care setting.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the nurses, other clinicians, administrators, and support staff at their partnering agencies: Dominican Sisters Family Health Services, Visiting Nurse Association of Hudson Valley, and Visiting Nurse Services in Westchester. The authors thank and acknowledge the contribution of Barnett S. Meyers, MD, Denise C. Fyffe, PhD, Amy E. Mlodzianowski, MS, LMSW, Judith C. Pomerantz, MS, APRN-C, and Rebecca L. Greenberg, MS, from the Weill Medical College of Cornell University in developing TRIAD. We would like to thank and acknowledge the contributions of Marilyn Cheung, Stein Gerontological Institute (SGI) administrator, and the SGI/GeriU e-learning production team in developing the Web-based version of the educational program. Dr. Brown developed the Web-based module in collaboration with the SGI/GeriU e-learning production team during her tenure as director of Education and Research at SGI.

Dr. Brown received support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and SGI and had a consulting relationship with the Health Foundation of South Florida. Dr. Bruce received research support from NIH and had consulting relationships with NIH projects funded to University of Rochester and with MediSpin, Inc. She is a board member of the Center for Mental Health Services, Visiting Nurse Services in New York, and the Geriatric Mental Health Foundation. She has provided expert testimony in the area of geriatric sociology for a lawsuit concerning equity-indexed annuities.

Sponsor’s Role: None.

Footnotes

A portion of this material was presented by E. L. Brown (March 2008). Detection of Depression in Older Adult Home Care Patients: Implications for a Professional Nursing Staff. In J. R. Dalton (Chair), Innovative Approaches to Providing Mental Health Services in Community-Based Settings. Symposium conducted at the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, Orlando, Florida.

Conflict of Interest: This study was sponsored by National Institute of Mental Health Grants R24 MH64608, K02 MH01634, K01 MH066942, and K01 MH073783; Weill Cornell Center for Aging Research and Clinical Care, Institute of Geriatric Psychiatry, Weill Medical College of Cornell University; and SGI.

Author’s Contributions: Brown, Raue, Sheeran, and Bruce: concept, design, interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript. Brown and Roos: development and implementation of the Web-based module and preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Charney DS, Reynolds CF, III, Lewis L, et al. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:664–672. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life: Consensus statement update. JAMA. 1997;278:1186–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. A 4-year prospective study. JAMA. 1997;277:1618–1623. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540440052032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arean PA, Cook BL. Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late life depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds CF, Frank E, Perel JM, et al. Nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression. JAMA. 1999;281:39–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Reynolds CF, III, et al. Pharmacotherapy of depression in older patients: A summary of the expert consensus guidelines. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7:361–376. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200111000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AHCPR Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care: Volume 2. Treatment of major depression, clinical practice guideline, Number 5. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frederick JT, Steinman LE, Prohaska T, et al. Late Life Depression Special Interest Project Panelists. Community-based treatment of late life depression an expert panel–informed literature review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:222–249. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, et al. Major depression in elderly home health care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1367–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyness JM, Caine ED, Jing DA, et al. Psychiatric disorders in older primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:249–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown EL, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, et al. Recognition of depression in the elderly receiving homecare services. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:208–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown EL, Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, et al. Recognition of late-life depression in home care: Accuracy of the outcome and assessment information set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:995–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruce ML, Brown EL, Raue PJ, et al. A randomized trial of depression assessment intervention in home healthcare. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1793–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, et al. Screening for depression in adults: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:765–776. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO) Screening for Delirium, Dementia and Depression in Older Adults. Toronto (ON): Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO); 2003. p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piven MLS. Detection of Depression in the Cognitively Intact Older Adult. Iowa City (IA): University of Iowa Gerontological Nursing Interventions Research Center, Research Dissemination Core; 2005. p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalton JR, Busch KD. Depression: The missing diagnosis in the elderly. Home Health Nurse. 1995;13:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preville M, Cote G, Boyer R, et al. Detection of depression and anxiety disorders by home care nurses. Aging Mental Health. 2004;8:400–409. doi: 10.1080/13607860410001725009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ell K, Unutzer J, Aranda M, et al. Routine PHQ-9 depression screening in home health care: Depression, prevalence, clinical and treatment characteristics and screening implementation. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2005;24:1–19. doi: 10.1300/J027v24n04_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. National Home and Hospice Survey. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown EL, Meyers BS, Lee PW, et al. Late-life depression in home healthcare: Is nursing ready? Long-Term Care Interface. 2004;47:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells K, Miranda J, Bruce ML, et al. Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:955–963. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (DSM-IV-TR) 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression: Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, et al. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewoods Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cervero RM, Wilson AL. Responsible planning for continuing education in the health professions. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1995;15:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis D, O’Brien M, Freemantle N, et al. Impact of Formal Continuing Medical Education. JAMA. 1999;282:867–874. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown EL, Raue PJ, Bruce ML, et al. Available Hopkins Medical Products. 2004. Depression Recognition and Assessment in Older Homecare Patients [videocassette, job aides] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore DE, Cervero RM, Fox R. A conceptual model of CME to address disparities in depression care. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27(S1):S40–S54. doi: 10.1002/chp.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Leonardi BC. Tips for facilitating learning: The lecture deserves some respect. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2007;38:154–161. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20070701-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buerhaus PI, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI. Implications of an aging registered nurse workforce. JAMA. 2000;283:2948–2954. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.22.2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcus P, Kennedy GJ, Wetherbee C, et al. Training professional home care staff to help reduce depression in elderly home care recipients. Clin Geriatr. 2006;14:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marlow KL. (Reviewer) Depression recognition and assessment in older homecare patients. J Gerontol Nurs. 2006;32:15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Response to Public Comments on the Revised OASIS C Instrument (Form# CMS–R–245/OMB# 0938–0760) for Home Health Quality Measures & Data Analysis (online) [Accessed April 2, 2009.];2009 Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HomeHealth-QualityInits/Downloads/HHQIResponsesToPublicComments.pdf.

- 37.Stein Gerontological Institute. Depression Recognition and Assessment in Older Homecare Patients 2006. [Accessed April 13, 2009.];Weill Cornell Homecare Research Partnership (online) Available at http://www.geriu.org/uploads/applications/DepressionInHomecare/DinHomecare.html.