Abstract

Spinal cord injury often impacts a person’s ability to perform critical activities of daily living and can have a negative impact on their quality of life. Assistive technology aims to bridge this gap to augment function and increase independence. It is critical to involve consumers in the design and evaluation process as new technologies, like brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), are developed. In a survey study of fifty-seven veterans with spinal cord injury who were participating in the National Veterans Wheelchair Games, we found that restoration of bladder/bowel control, walking, and arm/hand function (tetraplegia only) were all high priorities for improving quality of life. Many of the participants had not used or heard of some currently available technologies designed to improve function or the ability to interact with their environment. The majority of individuals in this study were interested in using a BCI, particularly for controlling functional electrical stimulation to restore lost function. Independent operation was considered to be the most important design criteria. Interestingly, many participants reported that they would be willing to consider surgery to implant a BCI even though non-invasiveness was a high priority design requirement. This survey demonstrates the interest of individuals with spinal cord injury in receiving and contributing to the design of BCI.

Keywords: Assistive technology, brain-computer interfaces, disability, function, functional electrical stimulation, neuroprosthetics, priorities, quality of life, spinal cord injury, veterans

Introduction

Assistive technology aims to augment function for individuals with disability to increase their ability to perform activities of daily living and interact with their environment. Increased access to the environment (measured by the CHART mobility score) is positively associated with life satisfaction (1). Intuitively, the better assistive technology meets an individual’s needs, the more likely it is to be accepted and utilized. Researchers have increasingly begun to include technology users in the design and evaluation process (2–5). It has been documented that consumers who feel more informed about assistive technology are more satisfied with the device (6). Similarly, when their needs are not met, consumers are less satisfied with the technology (6).

One emerging field in assistive technology that is starting to undergo limited clinical trials is brain-computer interfaces (BCI). BCIs establish a direct link between neural signals generated in the brain and external devices (7–11). This neural interface technology aims to assist individuals with impaired mobility or communication and has the potential to improve the quality of life of individuals with disabilities. Preclinical experiments in non-human primates have demonstrated that information related to intended movement can be extracted from the motor cortex (12–17). A number of neural recording technologies are being investigated for BCI applications in humans including scalp electroencephalography (EEG) (18–20), electrocorticography (ECoG) (21–24), and intracortical microelectrode recordings (25–27). Each recording technique offers advantages and disadvantages in terms of invasiveness, system complexity, and signal quality (8). While researchers continue to develop these recording methods, it is important to gain insight from potential BCI users about desired functionality and design characteristics.

Here we focus on individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI), while recognizing that people with other disabilities may also benefit from a BCI. Persons with chronic SCI are unique in that their condition tends to be stable and the motor cortex function remains relatively intact (28, 29), potentially providing a robust BCI control signal which has been demonstrated in a few individuals (25, 26). Functional limitations resulting from SCI lead to reduced independence and community participation (30, 31). People with SCI also tend to report a lower quality of life compared to their able-bodied peers (32, 33).

A number of studies have looked at priorities for functional restoration as defined by individuals with SCI (34, 35). In a survey of 681 individuals with SCI, Anderson reported that arm and hand function was by far the top priority for functional recovery for individuals with tetraplegia. Sexual function was the highest priority for the group with paraplegia. More than 30% of people who completed the survey indicated that improvement in bladder/bowel function was the first or second most important priority.

Similar results were found by Snoek et al. who surveyed 565 members of the Dutch and United Kingdom SCI Associations with tetraplegia. 77% of respondents indicated that improvement in hand function would result in an important or very important improvement in quality of life. Bladder/bowel function was the next most important factor for this group.

Four previous studies have investigated consumer preferences for neural interfaces, one specifically on BCIs. Huggins et al. surveyed 61 people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and found that 84% would accept an electrode cap for recording brain signals for a BCI (36). 72% of subjects were willing to accept surgically implanted electrodes requiring an outpatient procedure and 41% were willing to accept a short hospital stay. Among these people, interest was very high (median score 10/10) in ten different BCI-operated tasks ranging from wheelchair control to light switch operation. Driving a wheelchair and controlling a robotic arm for self-feeding trended towards a more significant interest level when compared to the other tasks. The most important BCI design criteria were accuracy, setup simplicity, standby reliability, and the number of available functions. The bar for success was fairly high with the majority of users desiring at least 90% accuracy and the ability to communicate at a rate of 15–19 letters per minute. This study suggests that people with ALS are interested in using a BCI if it can reliably perform a wide variety of functions in a manner that is superior to existing assistive technologies.

Two of the neural interface surveys focused on functional electrical stimulation (FES) for restoration of motor function (37, 38). FES has the potential to restore mobility by stimulating peripheral nerves or muscles to drive patterned muscle contraction. Brown-Triolo et al. conducted phone interviews with ninety-four persons with paraplegia and asked them to prioritize the tasks of standing, walking, stair climbing, and transferring (38). 66% of participants listed walking as the top priority followed by standing, which was the top priority for 23.4% of the subjects. This study also found that participants were more amenable to implanted technology than visible devices. However, respondents were less likely to indicate that implantation surgery was acceptable. The third study summarized patient preferences for neural prostheses to restore bladder function (5). Potential side effects were the most significant factor for choosing a neural prosthesis to restore bladder function and effectiveness (on continence and voiding) was the next most important factor. The participants also desired a system with minimally invasive electrodes that could be operated simply by pushing a button. While these studies have addressed the use of peripheral interfaces for restoring function, none have investigated BCI preferences in people with SCI.

The goal of this study was to determine how SCI impacts veterans’ ability to perform activities of daily living and to assess their knowledge about currently available assistive technologies and clinical interventions designed to increase function. Further, we sought out to determine whether they believe BCIs have the potential to increase their function and improve their quality of life. As the rate of technological advancement continues to increase, it is important to include users in the design process so that the technology addresses the current needs and priorities of the consumers.

Methods

Survey Design

A survey was developed to gauge functional priorities, knowledge of technology, and preferences about BCI from veterans with SCI. Nearly 20% of the spinal cord injured population in the United States are veterans (39). The survey was designed based on existing questionnaires (34, 40) and with input from all of the authors and local experts in SCI or neural interfaces. The survey included an introductory page that described the purpose of the study, the inclusion criteria, directions for the survey, and a statement that participation was voluntary. The survey is available as online Supplemental Material. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

The first half of the survey was designed to assess demographic information about the sample population as well as the impact of SCI on function. Demographic information was collected on age, injury level, date of injury, education level, and employment. Participants were also asked to rate their ability to perform activities of daily living using a self-reported functional independence measurement (FIM) scale (41, 42). The activities of daily living included eating, grooming, bathing, upper body dressing, lower body dressing, toileting, and transferring to a bed, chair, or wheelchair. Participants rated their ability to perform each of these activities on a scale ranging from 1 (total assistance) – 7 (completely independent). A rating of 0 was selected if the activity was not performed. Hours of paid and unpaid assistance were also reported.

Additionally, we included a similar question to that asked by Anderson in her 2004 study (34): Which function, if restored, would have the most positive impact on your quality of life? The functions included: arm/hand function, upper body/trunk strength and balance, walking movement, bladder/bowel function, sexual function, elimination of dysreflexia, elimination of chronic pain, and normal sensation. Participants were asked to rank the 8 functions from most to least important. We also asked participants to rate each item on a scale from 1 (unnecessary) – 5 (very important) in terms of how important improvement in a particular function would be for their quality of life.

The first half of the survey also addressed participants’ familiarity with currently available assistive devices and interventions including functional electrical stimulation (FES), hand orthoses, robotic arm assistants, robotically-assisted walking training, hand controls for driving, computer access technology, tendon transfer surgery for improved hand function, spinal cord stimulators for pain management, and transcutanous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Subjects were asked to indicate whether they had used this technology, heard of this technology, or neither. We did not provide detailed descriptions of these technologies, however participants were encouraged to ask the experimenters for clarification if there was any item they did not fully understand.

The second half of the survey focused on BCI technology. Participants were asked if they had heard of BCI technology and then a half page summary of BCI technology and potential applications was provided to establish baseline awareness across the entire sample (Appendix A). The next set of questions asked whether or not participants thought they would use a BCI and what types of assistive technology they thought a BCI would be helpful for controlling. Ratings of very helpful, somewhat helpful, or not helpful were assigned by the participants to brain-controlled computers, wheelchairs, robotic assistants, and various FES devices. We also asked which design characteristics would influence their decision about whether or not to use a BCI using a scale of very important, somewhat important, or not important. The design characteristics included non-invasiveness, set-up time, independent operation, training time, cost, number of functions provided, and response time which is defined as the time between the command issued by the brain signal and the resulting response of the output device, like a computer cursor. Finally, we asked whether or not participants would be willing to have surgery to implant BCI electrodes and how often they would be willing to come to a laboratory or hospital for training. Space was also provided for open-ended comments related to BCI technology.

Data Collection and Analysis

Individuals who were age 18 or older, had a spinal cord injury, and spoke English were recruited to participate in this paper-based survey as a volunteer sample at the 2010 National Veterans Wheelchair Games in Denver, CO. All subjects were participants in the National Veterans Wheelchair Games which typically attract more than 500 veterans each year. Participants completed the survey anonymously. Responses were input manually into an IBM SPSS database (IBM, New York, NY) by a research staff member and checked by the lead author. Descriptive analyses (frequencies, means and standard deviations) were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 19. The study sample was split by injury level (paraplegia vs. tetraplegia) since we expected that functional priorities and technology preferences to be dependent on the level of impairment. Independent samples t-tests were used to compare age and years with injury between the groups. Chi-squared tests were used to compare gender and injury classification (complete vs. incomplete) between the groups. Missing or invalid responses are noted in the results section. Response rates were calculated as a percentage of the total number of valid responses for each question.

Results

Demographics

Fifty-seven veterans with spinal cord injury completed the survey (Table 1). Of these, 21 individuals (37%) had tetraplegia and 36 (63%) had paraplegia. Injury levels ranged from C3-C7 for the group with tetraplegia and from T3-L4 for the group with paraplegia. One third of the subjects with tetraplegia and half of the subjects with paraplegia reported complete injuries. Of the subjects with incomplete injuries, 12 were sensory incomplete (5 with tetraplegia) and 16 were motor incomplete (6 with tetraplegia). One subject with tetraplegia reported minimal deficit. Another reported normal motor and sensory function although it should be noted that all participants used wheelchairs for some of their mobility. On average, the group of veterans with tetraplegia were 55.2±8.3 years old and 22.6±11.7 years post-injury. Individuals with paraplegia were 51.3±12.2 years old and 16.2±10.9 years post-injury. Individuals with tetraplegia were significantly (p=.044) further out from injury than the group with paraplegia. Additional demographic information for the survey population is presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age, gender, or injury classification between the two groups (all p>0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic information for veterans with tetraplegia and paraplegia

| Tetraplegia | Paraplegia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Demographics | n | % | n | % |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 20 | 95.2 | 31 | 86.1 |

| Female | 1 | 4.8 | 5 | 13.9 |

| Injury Classificationa | ||||

| Complete | 7 | 35.0 | 19 | 52.8 |

| Incomplete | 13 | 65.0 | 17 | 47.2 |

| Education | ||||

| 9th–11th grade | -- | -- | 1 | 2.8 |

| High school/GED | 14 | 66.7 | 14 | 38.9 |

| Associate’s degree | 1 | 4.8 | 12 | 33.3 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 | 9.5 | 4 | 11.1 |

| Master’s degree | 3 | 14.3 | 3 | 8.3 |

| Doctoral degree | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 2.8 |

| Other | -- | -- | 1 | 2.8 |

| Employment | ||||

| Working | 2 | 9.5 | 2 | 5.6 |

| Homemaker | -- | -- | 1 | 2.8 |

| On-the-job training | -- | -- | 1 | 2.8 |

| Retired | 14 | 66.7 | 20 | 55.6 |

| Student | 2 | 9.5 | 2 | 5.6 |

| Unemployed | 1 | 4.8 | 8 | 22.2 |

| Other | 2 | 9.5 | 2 | 5.6 |

Table entries are written as number (% of subgroup or total). Missing responses are indicated by a superscript letter in the first column of the table:

one participant with tetraplegia did not report injury classification

Assistance with activities of daily living

More than half (52.3%) of respondents with tetraplegia, but less than a quarter (22.2%) of those with paraplegia, reported having paid assistance for self-care activities or mobility. When unpaid assistance is included, 71% of individuals with tetraplegia and 56% of participants with paraplegia typically require some assistance with activities of daily living. Figure 1 summarizes the percentage of individuals who require assistance or supervision to perform seven different activities of daily living as reported by the FIM. Due to the bimodal distribution of the data, FIM scores of 1–5 were collapsed into a single group requiring assistance or supervision and scores of 6 and 7 were considered as independent performance. On average, approximately half of the participants with tetraplegia reported requiring assistance or supervision with these seven self-care activities compared to only 11% of those with paraplegia. Bathing and lower body dressing were the two most common tasks requiring assistance for both injury groups.

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants with tetraplegia or paraplegia who report requiring assistance or supervision to complete activities of daily living

Experience with assistive devices or interventions

Figure 2 illustrates the percentage of individuals, grouped by injury level, who have used or heard of various assistive devices or clinical interventions. In general, more people had used or heard of the technologies as compared to the number of people who had not heard of the device or intervention. By far, the most commonly used device was hand controls for adapted driving, used by more than 60% of participants with tetraplegia and more than 90% of those with paraplegia. Approximately 40% of survey respondents have used FES which was the next most commonly used technology. We did not distinguish between implanted systems or surface systems. If participants asked for additional clarification, we instructed them that both types of devices were considered FES for the purposes of this survey. Four responses (4 participants, 1 technology each) were missing.

Figure 2.

Reported experience or familiarity with various assistive devices or clinical interventions. The bar graphs show the percentage of respondents who had used the technology, only heard of the technology, or had neither used or heard of the technology. The devices and interventions are ordered from most familiar (left) to least familiar (right) based on the average percentage of people who had neither heard of nor used the technology. FES= functional electrical stimulation; TENS= transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

Functional priorities for quality of life

When asked to rate the importance of functional priorities for improving their quality of life, in general, more than half of the respondents indicated that improvement of each of the eight functions was “very important” (Figure 3). The exceptions were arm/hand function and elimination of dysreflexia among individuals with paraplegia and elimination of chronic pain for those with tetraplegia. Very few people rated any of these functions as “unnecessary” or “not very important”. For those with tetraplegia, this ranged from 0–4 people (0–19%) for the eight functions shown in Figure 3. The responses for participants with paraplegia were more variable. The number of participants who rated these functional priorities as unnecessary or not very important were: 18 for arm and hand function (51%); 6 for upper body function (17%); 3 for walking (9%); 1 for bladder/bowel function (3%); 5 for sexual function (14%); 8 for elimination of dysreflexia (23%); 4 for elimination of chronic pain (12%); and 2 for restoration of normal sensation (6%). One person with tetraplegia did not provide a response for walking, bladder/bowel, and dysreflexia, and one subject with paraplegia did not answer this question.

Figure 3.

Percentage of respondents with tetraplegia or paraplegia who indicated that restoration of various functions is “very important” for improvement of quality of life. The categories are ordered based on the relative difference in importance for people with tetraplegia compared to those with paraplegia.

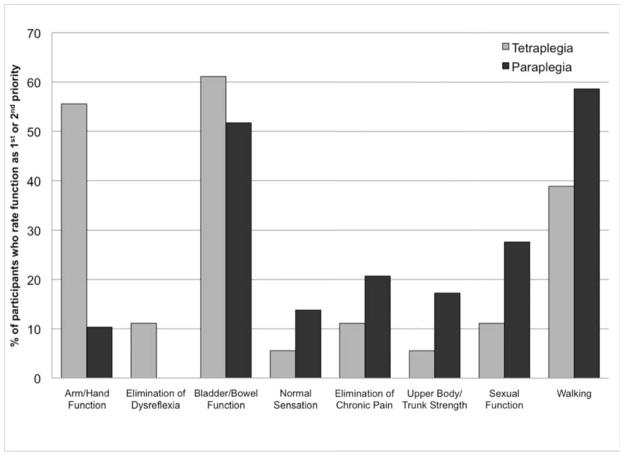

In a separate question, participants were asked to rate the same eight functions from most to least important in terms of improving quality of life. Three people with tetraplegia, and 7 people with paraplegia did not respond to this question or did not assign a unique rank to each function and so their answers were excluded. Figure 4 shows the percentage of individuals who rated each function as their 1st or 2nd most important priority. Improvement of bladder and bowel function as well as walking ability was important for both injury groups. Restoration of hand and arm function was a top (1st or 2nd highest) priority for approximately half of the participants with tetraplegia. The top priority among those with paraplegia was restoration of walking. For individuals with tetraplegia, restoration of bladder and bowel function was most commonly reported as the first or second priority.

Figure 4.

Percentage of respondents with tetraplegia or paraplegia who indicated that restoration of a given function was their 1st or 2nd most important priority for improvement of quality of life. The categories are ordered based on the relative difference in importance for people with tetraplegia compared to those with paraplegia.

Brain-computer interface (BCI) technology

Seventy-five percent of individuals with tetraplegia (out of the 20 respondents) and 53% of those with paraplegia reported having heard of BCI technology prior to completing the survey. All participants were provided with a short description of BCI technology before answering the remainder of the survey questions (Appendix A). Eighteen of 21 veterans with tetraplegia (86%) and 29 of 36 individuals with paraplegia (81%) indicated that they would use a BCI to assist with daily activities if it did not inconvenience other aspects of their life.

Participants were asked to rate six technologies in terms of how helpful they thought BCI-control would be: computer, wheelchair, FES for hand grasp, FES for the lower body, FES for bladder/bowel, and a robotic arm assistant. For each technology, BCI-control could be rated as very helpful, somewhat helpful, or not helpful (Figure 5). One person with tetraplegia omitted ratings for 4 of the technologies, and up to three people with paraplegia did not provide a rating for each of the technologies. In general, FES technologies were considered to be best suited for BCI control. As expected, FES for hand grasp was considered more helpful by participants with tetraplegia than those with paraplegia. FES for the lower body and bladder/bowel control was equally important to both groups.

Figure 5.

Percentage of respondents with tetraplegia or paraplegia who indicated that BCI control of various technologies would be “very helpful”

Participants were also asked to rate the importance of seven BCI design characteristics that they would consider when deciding whether or not to use a BCI device. In general, participants rated most of the design characteristics as very important for influencing their decision (Figure 6). Among both injury groups, independent operation was the most important design characteristic and training time was the least important. In a separate question, participants were asked how often they would be willing to come to a lab or clinic for BCI training. 51% said that they would come in as often as it took. Once per week (21%) or 2–3 times per week (21%) were the next most common responses and only 1 person said that they would not be willing to travel for training. Interestingly, even though more than 70% of respondents indicated that non-invasiveness was a very important design characteristic, more than half indicated that they would definitely, or very likely, consider having surgery to implant BCI electrodes (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Reported importance of various design characteristics to consider when deciding whether or not to use a BCI. The design characteristics are ordered from most important (left) to least important (right) based on the average percentage of people from both groups who ranked the characteristics as very important. Tetra= individuals with tetraplegia; Para= individuals with paraplegia

Figure 7.

Likelihood of study participants to have surgery to implant BCI electrodes

Participants were provided with space for open-ended comments about BCI technology. Nine subjects provided comments, of which six expressed a desire to use the technology in the future. One of these participants wrote that BCI was a “very cutting edge technology that can benefit many individuals.” Another individual commented that the idea of BCI “sounded far fetched” but that they “can’t wait to see it.” Two participants expressed a particular interest in using a BCI to assist with walking and standing. The other three participants requested additional information. Two of these individuals had general requests for additional information about BCI and one expressed a need to see results from preliminary clinical investigations, particularly regarding safety related to implantation of electrodes, prior to trying the device themselves.

Discussion

A number of investigators have called for greater involvement of individuals with SCI in developing research priorities (4, 43, 44). To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigates the priorities of individuals with SCI pertaining to BCI technology. A majority (>80%) of participants indicated that they would use a BCI if it did not inconvenience other aspects of their life. Most participants felt that BCI would be most useful for controlling FES devices to restore movement or function to their own muscles (Figure 5). The capability for the BCI to be operated independently was the most important design characteristic (Figure 6). Non-invasiveness was also rated as a high priority, however a majority of individuals would consider having surgery to implant a BCI (Figure 7).

All subjects in this study were participants at the 2010 National Veterans Wheelchair Games. Compared to a recent study that described demographic characteristics of the spinal cord injured population in the United States using data from the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center (45), our sample of veterans had a higher percentage of males and was older (Table 1). This study also included a higher percentage of individuals with paraplegia and a slightly lower percentage of complete injuries (45%). In the prevalent SCI population, approximately 25% of individuals have more than a high school level education compared to about 50% in our sample. The majority of individuals in the current study were retired (n=34) or unemployed (n=9). Although community participation was not measured in this study, we speculate that the current sample is at or above the mean level of community participation in the prevalent SCI population, since involvement in the National Veterans Wheelchair Games requires them to travel from across the United States.

In agreement with previous studies (34, 35), arm and hand function as well as bladder/bowel function were found to be the most important functional priorities (Figures 3, 4). The loss of arm and hand function after cervical spinal cord injury limits independence and employment opportunities, increasing the extent, duration, and overall costs of care for persons with tetraplegia (46). Restoration of walking was a high priority for both injury groups (Figure 3), which is comparable to the results reported by Anderson (34).

The large percentage of individuals with tetraplegia who require assistance with activities of daily living (Figure 1) is an indication of the inability of current assistive technologies to adequately meet the needs of the SCI population. In general, our study group was familiar with currently available assistive devices and interventions although not everyone was taking advantage of it (Figure 2). A fairly high number of respondents (~40%) had indicated that they had tried FES. We did not distinguish between implantable or non-invasive systems. Also, for all of the technologies, we did not measure whether subjects were currently and routinely using the technology or whether they had only limited experience with it. Many of the respondents commented that they had used surface FES as part of therapy or a research study. One potential reason for the low usage rates that were observed is that some devices and interventions are only appropriate for a subsample of the SCI population. A number of other potential barriers exist to widespread use of this technology including performance limitations, lack of access or financial resources, and the need for further education of the SCI population and clinicians. BCI technology may be able to improve the performance of some of these devices and may also provide a more intuitive control interface, particularly for complex technologies. In particular, FES systems and robotic assistants may have many degrees of freedom that would be difficult to control with switches, voice control, or other simple interfaces. A recent study showed that an individual with an intracortical microelectrode-based BCI could control a simulated dynamic arm in two continuous dimensions with an additional state control over finger flexion (47). Studies with able-bodied non-human primates using implanted microelectrodes suggest that the potential exists for controlling more sophisticated devices and have demonstrated reliable control of robotic arms to perform a self feeding task (16) as well as 7 degree of freedom reach and grasp (48).

More than half of the study participants had heard of BCI technology prior to completing the survey. Over 80% of survey respondents indicated that they would use a BCI to assist with daily activities if it did not inconvenience other aspects of their life. We view this as a very high percentage considering that more than half of the group had paraplegia and that our cohort was older than the prevalent population. A survey of people with ALS also found high interest levels in BCI with 84% accepting electrode caps and 72% accepting implanted electrodes requiring outpatient surgery (36). Previous studies have found that life satisfaction and quality of live improve for individuals with spinal cord injury as they age (44, 45, 49) and thus we expected that they may be less inclined to adopt new assistive technology.

Non-invasiveness, daily set-up time, independent operation, cost, number of functions provided, and response time were all felt to be “very important” design characteristics for a BCI (Figure 6). For individuals with tetraplegia, it seems that participants were willing to accept a longer training time if the other design criteria were satisfied. These results suggest that BCI users are willing to put in the time to learn how to use the device initially, but they want to minimize the amount of time that is spent on a daily basis with recalibration or setup. A similar preference to minimize setup time was found among individuals with ALS (36). Researchers should prioritize the need to identify stable neural features that require infrequent recalibration. Alternatively, it may be possible to develop automated algorithms that adjust the neural decoder during normal BCI operation so that it is transparent to the user. Independent operation of the BCI was the most important factor for both injury groups. Currently all BCI systems require some intervention from an operator, either to place the scalp electrodes for each session or to operate the recording hardware and computer that interprets the brain signals into useable control signals. At this stage, most BCIs are operated in laboratory settings and are not yet optimized for home use. Further developments are needed to translate BCIs into clinically viable, independently operated products, including wireless capabilities, improved long term signal stability and performance, and integration with other assistive technologies (50, 51).

Non-invasiveness was also a high priority for this group of potential BCI consumers. The downside of non-invasive systems is that assistance is required to place the electrodes on a daily basis which is contrary to the users’ priority of independent operation. This is similar to the findings of a previous study regarding FES in which participants preferred an unobtrusive, implantable system to restore movement, but were less open to having surgery to implant the device (38). The results from Huggins et al. suggest that the length of the post-operative hospital stay influences the degree of acceptance of invasive BCIs (36). A recent article related to intracortical BCIs discusses the tradeoff between invasiveness and burdens and benefits experienced by the user (51). While a surgical procedure inherently carries risk to the patient, other less obvious negative influences on well-being are also possible for both invasive and non-invasive systems. These include the burden of daily setup, recharging the system, cosmetic burden, and burden on caregivers.

In the ideal scenario, a fully-implantable wireless device could safely provide robust control over multiple degrees of freedom without these daily burdens. This ideal system would best meet the needs of the consumer population and therefore it is important to continue technology development and safety and efficacy testing towards the clinical realization of this type of system. It is important to remember that numerous implantable devices are widely used clinically for treating neurological, motor, cardiac, and other medical conditions. Human testing of implanted BCI systems is currently underway with individuals with disabilities (25, 26). We expect that the feedback from these early studies will provide even greater insight into consumer priorities as well as the performance of different types of electrodes and control interfaces.

FES was by far the most popular choice of assistive technology that people would like to control with a BCI. As expected, priorities for BCI-controlled assistive technology (Figure 5) are well-aligned with priorities for functional restoration (Figures 3 and 4). FES represents a promising approach for restoring motor function after SCI. Several research groups have demonstrated that useful grasp functions can be restored with FES applied through implanted and surface electrodes (46, 52, 53). One current limitation of FES, particularly for restoring hand and arm function, is the need for a high-dimensional control signal. BCI aims to address this gap by providing intuitive and proportional control over multiple dimensions. Additional development and testing of both FES and BCI technologies is required to determine if a hybrid technology provides functional benefit over simple switch-like control systems. It is unclear from this survey whether BCI-operated FES is any more or less desirable than FES that is operated by another control interface. Despite these limitations, it is still valuable to confirm that restoration of one’s own body function is top priority to potential consumers. Participants also expressed a strong desire for BCI-controlled FES to improve bladder and bowel function (Figure 5). A BCI may be preferred over an external switch controller for systems that have many degrees of freedom and particularly for systems that involve movement like prosthetics or FES. While a bladder or bowel neuroprosthesis does not necessarily meet this criteria, one can imagine that controlling this device with only 1 or 2 degrees of freedom could be one of many functions provided by a BCI system.

We expected that robotic arm assistants may have a comparable level of interest to FES for hand grasp among individuals with tetraplegia since the goal of these devices is to replace the function of the upper limbs. However, only 25% of respondents thought that BCI-controlled robotic arm assistants would be very helpful compared to 75% who thought that BCI-controlled FES for hand grasp would be very helpful (Figure 5). An additional 45% of study participants with tetraplegia thought that BCI-controlled robotic arm assistants would be somewhat helpful. One possible explanation is that the sample of subjects with tetraplegia was not very familiar with robotic arm assistants since 90% reported that they had never used these devices. We did not describe a specific robotic arm for participants to evaluate and a wide range devices are available or in development that have different levels of functionality and aesthetic appeal (54, 55). A great deal of current BCI research is focused on robotic or prosthetic arm control. There are many reasons for this but one important factor is that robotic technology is capable of producing reliable and complex movements that necessitate a high-dimensional control signal. State of the art implanted FES is capable of restoring simple hand grasps and upper limb movements depending on a person’s level of innervation, but there remains room for improvement in terms of movement accuracy, robustness, and dexterity. Another limitation of FES is muscle fatigue since electrical stimulation may result in a reversed recruitment pattern in which large diameter, fatigable muscle fibers are recruited first (56). Engineers are working to resolve these limitations by combining novel electrode design with optimized stimulation parameters. We suspect that the desire to reanimate one’s own limbs is the primary contributing factor for the observed preference of FES over robotic arm assistants. For individuals with SCI, brain-controlled FES should be the highest priority. However, a parallel investigation path is warranted while both BCI and FES continue to mature. Also, among individuals with ALS, interest in BCI-controlled robotic arms was very high (36).

More than 30% of participants would consider BCI technology to be “very helpful” for controlling computers and their wheelchair (Figure 5). This is somewhat surprising since the majority of individuals with paraplegia are likely to use manual wheelchairs. Also, various existing control interfaces exist to provide control of power wheelchairs for individuals with varying level of impairment. However, one can imagine that it might be desirable drive a wheelchair or control a seat function intuitively by thought in a manner similar to an able-bodied person controlling their own movements. A number of useful computer access technologies are available, but there remains room for improvement (57). A BCI would have to provide an increase in performance compared to these other technologies in order to be an effective computer access device.

This study was limited to a convenience sample at the National Veterans Wheelchair Games and thus the results may not generalize to all veterans with SCI, nor civilians with SCI. The results may be biased since our sample consisted solely of veterans (mostly male) and was older than the prevalent population of spinal cord injured individuals. A large percentage of our cohort was retired or not employed and it is unclear whether their disability has an impact on their employment status. It is possible that our sample included people with higher than average levels of community integration since they were all part of a team at their local VA hospital that travels to this competitive event annually. Also, our sample included more incomplete injuries than the prevalent population so they may have been more independent in performing activities of daily living (Figure 1).

Although many of the questions allowed the participants to write in additional answers (e.g. technology to be controlled by a BCI, important BCI functions, etc.), most people chose not to do so. Therefore the survey design limited the potential responses from the participants and it is possible that important characteristics or priorities were missed. For example, it would be interesting to know how extensively the participants used the various assistive technologies that were presented. Another limitation is that we did not compare the preference for BCI to alternative control interfaces. The effectiveness of the control interface depends on an individual’s current level of motor function as well as the complexity of the end effector. It is the responsibility of clinicians and rehabilitation engineers to recommend the most appropriate and safe technology for their patients. The results of this study do support the continued development of BCI technology as a potential control interface for complex assistive technologies, particularly those that directly restore motor function. Future studies should be expanded to include non-veterans and individuals with other motor impairments. Additional efforts should be made to include individuals who may be less active in the community than our cohort as they may benefit the most from BCI technology as a way to increase their independence.

Conclusions

This was the first study to report priorities for BCI among individuals with SCI. Overall, veterans with SCI felt that BCI would be a useful technology for restoring important motor functions. Independent operation and restoration of one’s own motor function were important priorities for BCI design. It is clear that the success of BCI technology depends on effectively integrating with other technologies like FES in order to improve the user’s ability to interact with their environment. BCI may be one way to improve environmental access by improving the functionality of other assistive devices that allow for restoration or augmentation of function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Brittany Mitlo for her assistance with the SPSS database and questionnaire design as well as the researchers from the Human Engineering Research Laboratories who assisted with data collection at the 2010 National Veterans Wheelchair Games.

This material is based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research & Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, Grant# B6789C and the Paralyzed Veterans of America. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the United States government.

Institutional Review: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System.

Participant Follow-Up: The authors do not plan to inform participants of the publication of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- BCI

brain-computer interface

- CHART

Craig Handicap Assessment and Recording Technique

- EEG

electroencephalography

- ECoG

electrocorticography

- FES

functional electrical stimulation

- FIM

functional independence measure

- SCI

spinal cord injury

- TENS

transcutaneous electrical stimulation

Appendix A

The following is the description of BCI technology that was included in each questionnaire.

Before completing the rest of the questionnaire, we would like to provide a quick description of BCI technology.

-

How does it work?

Brain activity is measured using various types of electrodes. Some electrodes are placed on the scalp, while others require surgical implantation. There are two types of implanted electrodes. The first type is placed on the brain surface, without penetrating the brain tissue. The second type of implanted electrodes are miniature needles that penetrate the brain tissue. Both types of electrodes are used clinically for treatment of pain, Parkinson’s disease, and other neurological disorders.

BCI technology CANNOT read your thoughts. BCIs can only recognize specific types of activity such as changes that occur in the brain when you imagine moving a specific body part.

The brain signals are sent to a computer which translates them into a control signal for an external device, such as a FES system or robotic assistant.

-

How could BCI technology benefit me?

Your spinal cord injury likely resulted in muscle paralysis, which limits some of your functional abilities. BCI technology could be used to control a number of devices to aid with activities of daily living.

-

BCI technology is currently being studied for research purposes. However, researchers are working to develop BCIs to control the following devices:

Computers (alternate mouse or keyboard input)

Power wheelchairs (driving or seat function access)

Functional electrical stimulators (devices that stimulate muscles and nerves that have been paralyzed to restore some degree of function)

Robotic arm assistants (to aid with daily tasks that require reaching and grasping). The robot could be mounted to a wheelchair.

Footnotes

Statement of Responsibility/Author Contributions:

All authors meet the journal’s guidelines for authorship as detailed below.

Study concept and design: J.L. Collinger, M.L. Boninger, D.J. Weber

Survey design: J.L. Collinger, M.L. Boninger, T.M. Bruns, K. Curley, W. Wang, D.J. Weber

Analysis and interpretation of data: J.L. Collinger, M.L. Boninger

Drafting of manuscript: J.L. Collinger, M.L. Boninger, T.M. Bruns

Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: J.L. Collinger, M.L. Boninger, T.M. Bruns, K. Curley, W. Wang, D.J. Weber

We certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on us or any organization with which we are associated and we certify that all financial and material support for this research and work are clearly identified in the title page of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Richards JS, Bombardier CH, Tate D, Dijkers M, Gordon W, Shewchuk R, DeVivo MJ. Access to the environment and life satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999 Nov;80(11):1501–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma V, Simpson RC, LoPresti EF, Mostowy C, Olson J, Puhlman J, Hayashi S, Cooper RA, Konarski E, Kerley B. Participatory design in the development of the wheelchair convoy system. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2008;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H, Grindle GG, Chuang FC, Kelleher AR, Cooper RM, Sieworek D, Smailagic A, Cooper RA. User preferences for indicator and feedback modalities: A preliminary survery study for developing a coaching system to facilitate wheelchair power seat function usage. IEEE Pervasive Computing. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson KD. Consideration of user priorities when developing neural prosthetics. J Neural Eng. 2009 Oct;6(5):055003. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/5/055003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders PM, Ijzerman MJ, Roach MJ, Gustafson KJ. Patient preferences for next generation neural prostheses to restore bladder function. Spinal Cord. 2010 Jan;49(1):113–9. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin JK, Martin LG, Stumbo NJ, Morrill JH. The impact of consumer involvement on satisfaction with and use of assistive technology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2011;6(3):225–42. doi: 10.3109/17483107.2010.522685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebedev MA, Nicolelis MA. Brain-machine interfaces: past, present and future. Trends Neurosci. 2006 Sep;29(9):536–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz AB, Cui XT, Weber DJ, Moran DW. Brain-controlled interfaces: movement restoration with neural prosthetics. Neuron. 2006 Oct 5;52(1):205–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly JJ, Wolpaw JR. Brain-computer interfaces in neurological rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Nov;7(11):1032–43. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donoghue JP. Bridging the brain to the world: a perspective on neural interface systems. Neuron. 2008 Nov 6;60(3):511–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang W, Collinger JL, Perez MA, Tyler-Kabara EC, Cohen LG, Birbaumer N, Brose SW, Schwartz AB, Boninger ML, Weber DJ. Neural interface technology for rehabilitation: exploiting and promoting neuroplasticity. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010 Feb;21(1):157–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vargas-Irwin CE, Shakhnarovich G, Yadollahpour P, Mislow JM, Black MJ, Donoghue JP. Decoding complete reach and grasp actions from local primary motor cortex populations. J Neurosci. 2010 Jul 21;30(29):9659–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5443-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Georgopoulos AP, Schwartz AB, Kettner RE. Neuronal population coding of movement direction. Science. 1986 Sep 26;233(4771):1416–9. doi: 10.1126/science.3749885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moran DW, Schwartz AB. Motor cortical representation of speed and direction during reaching. J Neurophysiol. 1999 Nov;82(5):2676–92. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor DM, Tillery SI, Schwartz AB. Direct cortical control of 3D neuroprosthetic devices. Science. 2002 Jun 7;296(5574):1829–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1070291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velliste M, Perel S, Spalding MC, Whitford AS, Schwartz AB. Cortical control of a prosthetic arm for self-feeding. Nature. 2008 Jun 19;453(7198):1098–101. doi: 10.1038/nature06996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serruya MD, Hatsopoulos NG, Paninski L, Fellows MR, Donoghue JP. Instant neural control of a movement signal. Nature. 2002 Mar 14;416(6877):141–2. doi: 10.1038/416141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sellers EW, Donchin E. A P300-based brain-computer interface: initial tests by ALS patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006 Mar;117(3):538–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFarland DJ, Sarnacki WA, Wolpaw JR. Electroencephalographic (EEG) control of three-dimensional movement. J Neural Eng. 2010 Jun;7(3):036007. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/7/3/036007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nijboer F, Birbaumer N, Kubler A. The influence of psychological state and motivation on brain-computer interface performance in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis - a longitudinal study. Front Neurosci. 2010:4. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leuthardt EC, Schalk G, Wolpaw JR, Ojemann JG, Moran DW. A brain-computer interface using electrocorticographic signals in humans. J Neural Eng. 2004 Jun;1(2):63–71. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/1/2/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schalk G, Miller KJ, Anderson NR, Wilson JA, Smyth MD, Ojemann JG, Moran DW, Wolpaw JR, Leuthardt EC. Two-dimensional movement control using electrocorticographic signals in humans. J Neural Eng. 2008 Mar;5(1):75–84. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/5/1/008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blakely T, Miller KJ, Zanos SP, Rao RP, Ojemann JG. Robust, long-term control of an electrocorticographic brain-computer interface with fixed parameters. Neurosurg Focus. 2009 Jul;27(1):E13. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.FOCUS0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinjamuri R, Weber DJ, Mao ZH, Collinger JL, Degenhart AD, Kelly JW, Boninger ML, Tyler-Kabara EC, Wang W. Toward synergy-based brain-machine interfaces. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2011 Sep;15(5):726–36. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2011.2160272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochberg LR, Serruya MD, Friehs GM, Mukand JA, Saleh M, Caplan AH, Branner A, Chen D, Penn RD, Donoghue JP. Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia. Nature. 2006 Jul 13;442(7099):164–71. doi: 10.1038/nature04970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simeral JD, Kim SP, Black MJ, Donoghue JP, Hochberg LR. Neural control of cursor trajectory and click by a human with tetraplegia 1000 days after implant of an intracortical microelectrode array. J Neural Eng. 2011 Apr;8(2):025027. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/2/025027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy PR, Bakay RA. Restoration of neural output from a paralyzed patient by a direct brain connection. Neuroreport. 1998 Jun 1;9(8):1707–11. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199806010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curt A, Bruehlmeier M, Leenders KL, Roelcke U, Dietz V. Differential effect of spinal cord injury and functional impairment on human brain activation. J Neurotrauma. 2002 Jan;19(1):43–51. doi: 10.1089/089771502753460222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotz-Boendermaker S, Funk M, Summers P, Brugger P, Hepp-Reymond MC, Curt A, Kollias SS. Preservation of motor programs in paraplegics as demonstrated by attempted and imagined foot movements. Neuroimage. 2008 Jan 1;39(1):383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy P, Lude P, Taylor N. Quality of life, social participation, appraisals and coping post spinal cord injury: a review of four community samples. Spinal Cord. 2006 Feb;44(2):95–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlifue S, Gerhart K. Community integration in spinal cord injury of long duration. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19(2):91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barker RN, Kendall MD, Amsters DI, Pershouse KJ, Haines TP, Kuipers P. The relationship between quality of life and disability across the lifespan for people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009 Feb;47(2):149–55. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tate DG, Kalpakjian CZ, Forchheimer MB. Quality of life issues in individuals with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002 Dec;83(12 Suppl 2):S18–25. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.36835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004 Oct;21(10):1371–83. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snoek GJ, MJ IJ, Hermens HJ, Maxwell D, Biering-Sorensen F. Survey of the needs of patients with spinal cord injury: impact and priority for improvement in hand function in tetraplegics. Spinal Cord. 2004 Sep;42(9):526–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huggins JE, Wren PA, Gruis KL. What would brain-computer interface users want? Opinions and priorities of potential users with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011 Sep;12(5):318–24. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2011.572978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kilgore KL, Scherer M, Bobblitt R, Dettloff J, Dombrowski DM, Godbold N, Jatich JW, Morris R, Penko JS, Schremp ES, Cash LA. Neuroprosthesis consumers’ forum: consumer priorities for research directions. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001 Nov-Dec;38(6):655–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown-Triolo DL, Roach MJ, Nelson K, Triolo RJ. Consumer perspectives on mobility: implications for neuroprosthesis design. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002 Nov-Dec;39(6):659–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. [Accessed Aug 30, 2010];QUERI Fact Sheet: Spinal Cord Injury. 2009 http://www.queri.research.va.gov/about/factsheets/sci_factsheet.pdf.

- 40.National Spinal Cord Injury Database. Birmingham, AL: National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center; 2011. [cited 2010 5/1/10]; Available from: https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/public_content/nscisc_database.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grey N, Kennedy P. The Functional Independence Measure: a comparative study of clinician and self ratings. Paraplegia. 1993 Jul;31(7):457–61. doi: 10.1038/sc.1993.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masedo AI, Hanley M, Jensen MP, Ehde D, Cardenas DD. Reliability and validity of a self-report FIM (FIM-SR) in persons with amputation or spinal cord injury and chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005 Mar;84(3):167–76. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000154898.25609.4a. quiz 77–9, 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abma TA. Patient participation in health research: research with and for people with spinal cord injuries. Qual Health Res. 2005 Dec;15(10):1310–28. doi: 10.1177/1049732305282382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammell KR. Spinal cord injury rehabilitation research: patient priorities, current deficiencies and potential directions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(14):1209–18. doi: 10.3109/09638280903420325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeVivo MJ, Chen Y. Trends in new injuries, prevalent cases, and aging with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011 Mar;92(3):332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peckham PH, Keith MW, Kilgore KL, Grill JH, Wuolle KS, Thrope GB, Gorman P, Hobby J, Mulcahey MJ, Carroll S, Hentz VR, Wiegner A. Efficacy of an implanted neuroprosthesis for restoring hand grasp in tetraplegia: a multicenter study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001 Oct;82(10):1380–8. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.25910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chadwick EK, Blana D, Simeral JD, Lambrecht J, Kim SP, Cornwell AS, Taylor DM, Hochberg LR, Donoghue JP, Kirsch RF. Continuous neuronal ensemble control of simulated arm reaching by a human with tetraplegia. J Neural Eng. 2011 Jun;8(3):034003. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/3/034003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rasmussen RG, Clanton ST, Velliste M, Schwartz AB. Direct cortical control of prosthetic reach, hand orientation, and grasp. Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westgren N, Levi R. Quality of life and traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998 Nov;79(11):1433–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patil PG, Turner DA. The development of brain-machine interface neuroprosthetic devices. Neurotherapeutics. 2008 Jan;5(1):137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilja V, Chestek CA, Diester I, Henderson JM, Deisseroth K, Shenoy KV. Challenges and opportunities for next-generation intracortically based neural prostheses. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2011 Jul;58(7):1891–9. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2107553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prochazka A, Gauthier M, Wieler M, Kenwell Z. The bionic glove: an electrical stimulator garment that provides controlled grasp and hand opening in quadriplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997 Jun;78(6):608–14. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Popovic MR, Popovic DB, Keller T. Neuroprostheses for grasping. Neurol Res. 2002 Jul;24(5):443–52. doi: 10.1179/016164102101200311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brose SW, Weber DJ, Salatin BA, Grindle GG, Wang H, Vazquez JJ, Cooper RA. The role of assistive robotics in the lives of persons with disability. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Jun;89(6):509–21. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181cf569b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris A, Katyal K, Para M, Thomas J, editors. Revolutionizing Proshetics software technology; IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics; Anchorage, AK. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gater DR, Jr, Dolbow D, Tsui B, Gorgey AS. Functional electrical stimulation therapies after spinal cord injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2011;28(3):231–48. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2011-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cooper RA, Cooper R. Quality-of-life technology for people with spinal cord injuries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2009 Feb;21(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.