Abstract

Background

In 2010, recognizing the value of outcomes research to understand and bridge translational gaps, establish evidence in the clinical practice and delivery of medicine, and generate new hypotheses about ongoing questions of treatment and care, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established the Centers for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (CCOR) program.

Methods and Results

The NHLBI funded three centers and a research coordinating unit. Each center has an individual project focus, including: (1) characterizing care transition and predicting clinical events and quality of life for patients discharged after an acute coronary syndrome; (2) identifying center and regional factors associated with better patient outcomes across several cardiovascular conditions and procedures; and (3) examining the impact of health care reform in Massachusetts on overall and disparate care and outcomes for several cardiovascular conditions and venous thromboembolism. Cross-program collaborations seek to advance the field methodologically and to develop early stage investigators committed to careers in outcomes research.

Conclusions

The CCOR program represents a significant expansion of the NHLBI's investment in cardiovascular outcomes research. The vision of this program is to leverage scientific rigor and cross-program collaboration to advance the science of health care delivery and outcomes beyond what any individual unit could achieve alone.

Keywords: outcomes research, translation of knowledge, cross-collaboration

The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) convened a Working Group on Outcomes Research in Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) in 2004 to establish priorities for future research.1 As a direct output from this working group, the NHLBI has established many key initiatives including the Cardiovascular Research Network which focused on surveillance in cardiovascular disease in its early phases of funding, the Trials Assessing Innovative Strategies to Improve Clinical Practice through Guidelines in Heart, Lung and Blood Diseases which tested innovative interventions to improve adherence to guidelines, and the Implementation Research program focused on translating best practice into clinical practice.

To further promote outcomes research in cardiovascular disease, the NHLBI simultaneously released two Requests for Applications in October of 2009 (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-HL-10-008.html and http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-HL-10-018.html). The first request for applications was intended to fund three Centers for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (CCOR); the second was to fund a Research Coordinating Unit (RCU) in cooperative agreements with the NHLBI. These requests for applications encouraged outcomes research that examines strategies of clinical decision-making, health care policy, and the consequences of health care; compares the effectiveness of clinical tests or treatments on outcomes; examines contemporary patterns of care; generates evidence to inform quality of care and incorporate best practices into care decision-making and delivery, and promotes clinically appropriate choices by patients.2,3 The request solicited research that generates hypotheses, develops measures to assess processes and outcomes of care, and investigates strategies to address gaps in scientific knowledge relevant to clinical practice and health policy.2,3

Program Overview and Vision

The three selected centers in the NHLBI CCOR program have several components: a unifying research theme and structural core, support for novel research projects, and faculty development. The three centers include:

-

1)

Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research and Education (TRACE-CORE), University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA (Principal Investigator: Catarina Kiefe, PhD, MD; U01HL105268)

-

2)

Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University, New Haven, CT (Principal Investigators: Jeptha Curtis, MD and Harlan M. Krumholz, MD, SM; U01HL105270)

-

3)

Center for Health Insurance Reform, Cardiovascular Outcomes and Disparities, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA (Principal Investigator: Nancy R. Kressin, PhD; U01HL105342)

The RCU facilitates coordination of research activities and communications between and among awardees and the NHLBI CCOR. The RCU reviews CCOR research proposals and seeks to establish data standardization and sharing where appropriate; convenes meetings and maintains communications; promotes the cross-center development of early stage outcomes investigations; fosters collaboration both across the centers and with the larger outcomes research community; and provides programmatic evaluation. The RCU was awarded to Duke Clinical Research Institute at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC (Principal Investigator: Eric Peterson, MD, MPH; U01HL107023).

The overall CCOR vision is to innovate the science of cardiovascular health care delivery and patient outcomes, while aiming for the program to be more than the sum of its individual parts. In particular, the CCOR program seeks to contribute to the improvement of cardiovascular health through: (1) collaboration within the CCORs and with other scientific groups engaged in cardiovascular outcomes research; (2) methodological innovation; and (3) development of the next generation of cardiovascular outcomes researchers.

Structure of the Program

“If you want to be incrementally better: be competitive. If you want to be exponentially better: be cooperative.” ~Unknown

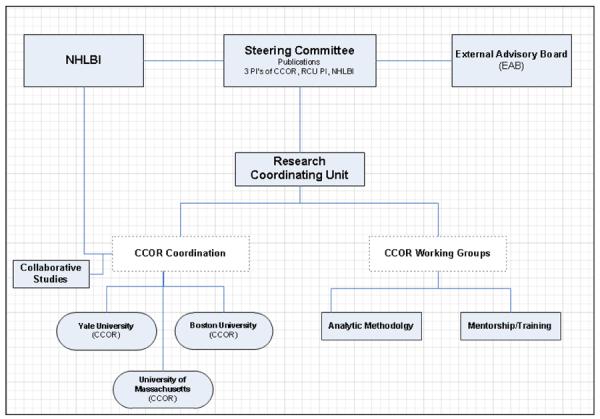

The goal of the CCOR program is facilitated by the overall structure (Figure). The CCOR projects supported in this program do not use a common study protocol; however, the program encourages investigators to work together to facilitate cross-program collaborations and knowledge sharing in an effort to foster a synergistic outcome from these individually funded grants. The participating centers are linked to each other through meetings, idea exchanges, the sharing of mutually beneficial knowledge and methods, and the creation of networking and development opportunities for early stage investigators (ESIs) and trainees. These activities are facilitated by the NHLBI Project Office, the RCU, and the Steering Committee which oversees the development of collaborative operating policies. An External Advisory Board was appointed to provide guidance and recommendations to the CCOR Steering Committee in hopes of enhancing the impact of the individual centers and the RCU on health care delivery and practice, as well as promoting collaboration in the overall program. This program structure, facilitated by a unique funding mechanism, brings the individual centers, the RCU, the NHLBI, and the External Advisory Board together to forge an intellectual network capable of advancing cardiovascular outcomes science beyond any one individual grant.

Figure. Structure of the Program.

This figure displays the organization structure of the NHLBI-sponsored CCOR program. CCOR indicates Centers for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Faculty Development and Training

One of the CCOR program's key areas of focus is developing the cardiovascular outcomes research pipeline. Each center has identified several ESIs who have significant roles in their designated projects. The senior leadership in each center has a plan for mentoring and career development, as well as institutional commitment for developing and retaining these individuals as outcomes researchers. Cross-institutional mentorship in the CCOR program provides a well-rounded perspective, as well as opportunities for career development and facilitation of future collaborative relationships. As such, ESIs participate in cross-program works in progress sessions and attend steering committee meetings to interact with senior investigators to provide feedback and input on potential manuscripts and grant proposals. Additionally, an ESI group has been established to review mentorship relations and provide peer support.

Program Evaluation

Given the current fiscal climate, it is critical to demonstrate the value of science and research. In order to elucidate this value, the CCOR program is detailing inputs (i.e., how many and what kind of scientists, participants, and funding) and outputs (i.e., knowledge, products, better health) that validate accountability to funding agencies and stakeholders. The evaluation includes center-specific metrics (e.g., project milestones) and metrics related to cross-program collaboration (e.g., cross-program publications and presentations). Center milestones are focused on tasks needed to complete specific aims as well as overall metrics for monitoring performance. For example, the University of Massachusetts center is recruiting participants. Their metrics include quarterly recruitment and retention goals as well as the number of ancillary studies submitted and graduate theses completed by early stage investigators. Importantly, the program as a whole will be collectively evaluated with an emphasis on establishing collaborative activities across the centers and the RCU. Examples of cross-program metrics for the program include cross-center manuscripts, editorials, and presentations; the number of cross-center applications to funding agencies; and the establishment of mentoring relationships across centers for early stage investigators.

Center Research Interests

University of Massachusetts Medical School

The Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research and Education (TRACE-CORE) has two overall goals of: (1) advancing the science of CVD outcomes by providing critical new knowledge about quality measurement and health disparities; and (2) training the next generation of cardiovascular outcomes researchers.

TRACE-CORE focuses on acute coronary syndromes (ACS), a condition for which nearly 1.5 million Americans are hospitalized annually. Although in-hospital and 30-day mortality for ACS have declined markedly over the years,4–6 evidence-based interventions are often either under-prescribed or prescribed, but not followed by patients. Furthermore, analysis of the National Medicare Administrative Claims data finds that 20% of patients hospitalized with an acute myocardial infarction are re-hospitalized within 30 days.7 Pharmacological and lifestyle based interventions have proven successful in preventing recurrent ACS events that require re-hospitalization.8–9 High quality care during the transition from hospital to home may reduce the re-hospitalization rate. Currently, there are no tools to comprehensively measure ACS transition quality. Furthermore, there is a lack in understanding the complex relationship between transition quality and repeatedly documented ACS health disparities.10–16 TRACE-CORE's Transitions Project are addressing these needs.

ACS decisions depend upon accurate risk assessment. Predictive indices such as the Framingham Risk Score for general populations,17 and the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Risk Score for hospitalized ACS patients18 are widely used in research, but less frequently in routine care. Use is limited because these scores: (1) place limited emphasis on modifiable factors; (2) exclude patient-centered factors such as symptoms; (3) exclude patient complexity, such as cognitive impairment; and (4) focus on clinical endpoints (e.g., mortality, readmission) without considering quality of life. TRACE-CORE's Action Scores Project will take a novel approach building on the Framingham Risk Score tradition, separating modifiable from non-modifiable risk, while considering patient-centered measures such as quality of life.

TRACE-CORE is a diverse inception cohort of 2,500 patients enrolled at an index hospitalization for ACS and followed for 12–18 months. The cohort will be recruited from urban, suburban, and rural areas of Massachusetts and Georgia from six community teaching and non-teaching hospitals. TRACE-CORE will (1) review the inpatient medical records of the index ACS hospitalizations, and conduct baseline in-person interviews; (2) conduct follow-up interviews at 1, 3, 6, and 12, months after discharge; all interviews collect quality of life, cognitive impairment, medication adherence, and health behavior, among other data; and use novel approaches to parsimoniously (yet precisely) collect patient-reported outcomes such as shortness of breath; and (3) follow patient vital status and readmission status for up to 2 years through national death index and administrative data.

The two TRACE-CORE research projects are hypothesis-driven. In the spirit of the CCOR initiative, TRACE-CORE represents a convergence of: (1) sound principles of primary data collection for observational studies and their analyses; and (2) outcomes and effectiveness research approaches to improve health care delivery and health-related quality of life.

Yale University

The Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University (CCOR) is dedicated to the generation and dissemination of scientifically-based knowledge that can be used by patients, practitioners, and policy makers to improve clinical decision-making and health care policy. CCOR has developed two complementary projects that seek to elucidate organizational and regional patterns of care, link them with outcomes, and uncover relationships that might assist in efforts to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of health care delivery. Furthermore, both projects provide opportunities for ESIs to participate substantively as leader of individual studies.

Project 1. Examining Novel Cardiovascular Outcomes and Regional Effects (ENCORE)

The ENCORE project leverages large existing databases and innovative analytic approaches to characterize hospital and regional performance and patient-level outcomes, assess patient, organizational and regional time trends, and determine factors associated with performance and improvement. The effort includes a focus on short and long-term outcomes. There is also a particular focus on costs of care in addition to clinical outcomes.

This project epitomizes the field of outcomes research – developing novel methodological approaches to illuminate previously hidden patterns in the data, promoting the identification and determinants of disparities in performance that may track by patient and regional characteristics, unveiling associations that indicate factors necessary to excel in clinical effectiveness and efficiency, and illuminating obstacles and opportunities to improve care.

Project 2. Translating Outstanding Performance in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (TOP PCI)

The TOP PCI project employs a mixed methods approach, combining qualitative and quantitative research methodology to identify the enabling structures associated with outstanding hospital performance on 30-day mortality and readmission following PCI. During the first phase, the team will conduct in-depth interviews of key informants at 10–15 high and low performing sited and use this information to develop hypotheses regarding the organizational strategies (i.e. structures, processes, hospital internal environments) associated with high and low hospital performance. During the second phase, the team will test these hypotheses using a web-based survey administered to a sample of the more than 1000 PCI hospitals that currently participate in the CathPCI Registry. The knowledge generated will serve as a foundation for hospitals' performance improvement efforts and will be disseminated through collaboration with key partner organizations.

Boston Medical Center/Boston University School of Medicine

A central policy assumption in the United States today is that expanding health insurance coverage will improve access to health care and patient outcomes, and make each more equitable. The state of Massachusetts (MA) is the site of a key policy-relevant natural experiment and is the ideal setting to examine the effects of gaining coverage on access to and use of care for cardiovascular conditions. The Center for Health Insurance Reform, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Disparities is based in the Health/Care Disparities Research Program within the Department of Medicine of the Boston University School of Medicine, and at Boston Medical Center, New England's largest urban safety net hospital

Project 1. The Effects of Massachusetts Health Reform on Cardiovascular Outcomes and Disparities

There has been little research using objective measures of healthcare utilization and outcomes related to the coverage expansion in MA. Changes in access to outpatient care under the reform can be examined indirectly in the absence of an all-payer outpatient data source. We will assess three measures of access to outpatient care: (1) changes in the utilization of referral-sensitive procedures; (2) hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (those believed to be preventable by access to ambulatory care within the weeks before admission)19; and (3) 30-day hospital readmissions, which are believed to be a marker of access to outpatient care, as post-hospital discharge access to follow-up outpatient care is critical to avoiding re-hospitalizations. The center will use inpatient administrative data on adults age 21–64 from four states, including MA, which have nearly-complete race and ethnicity indicators, sizable minority populations, and diagnosis and cost data for each admission. Data from 2004–2010 will be analyzed, encompassing the years before and after the 2006 MA health reform implementation to compare changes inoutcomes.

Project 2. Did Massachusetts Health Reform Reduce Disparities in Outcomes after Venous Thromboembolism, and at What Cost?

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is common, costly, and often fatal. Blacks have higher rates of VTE and worse prognosis,20 with a higher rate of mortality following pulmonary embolus21 and higher rates of complications22 and readmissions23 following VTE. Warfarin anticoagulation is the mainstay of VTE therapy, but limitations in accessing quality anticoagulation care likely contribute to disparities in outcomes. Comprehensive insurance coverage may enhance access to community-based pharmacies, dedicated anticoagulation clinics, primary care, and home care services which may contribute to improved outcomes. The team will use a dataset comprised of a diverse and high-risk population to examine outcomes (i.e., recurrent VTE, major hemorrhage, mortality, quality of life and costs) and disparities in outcomes, before and after health insurance reform. The analysis will use disease simulation, an integrative analysis technique that synthesizes acute and subacute phase outcomes in subpopulations tracked by a clinical database with long-term sequelae data from longitudinal studies of VTE.

The center's two projects are led by general internist ESIs with expertise in health services and disparities research, who will develop further proficiency in cardiovascular outcomes research through these activities.

Cross-program Collaboration

The CCOR program was designed to conduct rigorous research at each center and facilitate collaboration to support methods innovation, ESI development, and overall impact on the field of outcomes research. Attaining these goals is challenged by different themes and independent projects at each individual center. The CCOR program has taken several steps to overcome these challenges and promote collaborative opportunities for the advancement of outcomes science.

Perhaps one of the program's greatest strengths is the breadth of its methodologic approaches, the differences among protocols, and the diverse expertise across this intellectual network. Open discussion of challenges and ongoing progress at each center at steering committee meetings and meetings of the External Advisory Board have resulted in creative solutions, enhanced analyses, and new mentoring opportunities. These collaborations have been achieved through the sharing of protocols, regular meetings both in person and by teleconference, and a web site to support communication. Some specific examples include a collaboratively planned and executed concurrent session at the American Heart Association Quality of Care and Outcomes Research 2012 Scientific Sessions. The centers have convened brainstorming sessions with External Advisory Board members and investigators from the RCU to develop strategies to overcome center-specific research challenges that have arisen. Future plans include a State of the Science meeting with engaging other key cardiovascular outcomes research expertise, collaborative methodological research projects conducted by statisticians across the centers to deal with issues of confounding, missing data, etc., and rotating conferences dedicated to broaden cross-center mentorship for ESIs.

Limitations

The CCOR program while unique in many ways, does face limitations. The three centers in the program are limited in the cardiovascular conditions of focus, the populations of interest (both in geography and demographics), and the methodological approaches pursued. An important limitation is the lack of clinical trial methodology explored in the CCOR program. While the request for applications for this program was not restricted to a given methodology, the studies in the program all utilize observational design methods. Nevertheless, clinical trials remain an important approach for testing interventions in real world settings. The observational work funded in this program has the potential to lay the ground work for future clinical trials. For example, one objective of TRACE-CORE is to lay the foundation for interventional studies such as cluster-randomized trials of the “Dashboard for Cardiovascular Action” – an anticipated direct output from the Action Scores project. Furthermore, the observational work around readmissions taking place in all the centers may highlight key targets for interventions for this urgent yet difficult problem in our health care system.

Conclusions

With the continuing evolution of health care policy and the rapid pace of clinical discovery, high quality outcomes research is playing an increasingly important role in the generation of the knowledge necessary to improve clinical decision-making and health care delivery to optimize patient outcomes. The CCOR program encourages both scientific rigor and cross-program collaboration. Centers conduct innovative research while working with each other, the RCU, and the NHLBI to capitalize on the multidisciplinary, cross-institutional, and intellectual network in hopes of advancing the science of care delivery and outcomes beyond what any individual unit could achieve alone.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the CCOR Writing Group, including the following individuals:

From the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Michael S. Lauer, MD

Lawrence J. Fine, MD, DrPH

From the University of Massachusetts Medical School: Transitions, Risks, and Actions in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research and Education (TRACE-CORE) Jeroan J. Allison, MD, MScEpi

Milena Anatchkova, PhD

Frederick Anderson, PhD

Joseph Alpert, MD (University of Arizona)

Arlene Ash, PhD

Randy Devereux, PhD (Mercer University College of Medicine, Macon, GA)

David McManus, MD, MPH

Robert Goldberg, PhD

Joel Gore, MD

Jerry Gurwitz, MD, MPH

Lee Hargraves, PhD

Richard H. McManus, MSW, MPP

Jane Saczynski, PhD

Molly Waring, PhD

David Parish, MD, MPH (Mercer University College of Medicine, Macon, GA)

Douglas Roblin, PhD (Kaiser-Permanente of Georgia, Atlanta, GA)

John Ware, PhD

Zi Zhang, PhD

From the Boston Medical Center/Boston University School of Medicine: Center for Health Insurance Reform, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Disparities Amresh Hanchate, PhD

Karen Lasser, MD, MPH

Danny McCormick, MD

Adam Rose, PhD

Alok Kapoor,PhD

Meredith Manze D'Amore, MPH, PhD

From Yale University: Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation Karl E. Minges, MPH

Duke Outcomes Research Center, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC Kelley A. Ryan, BA, MC

Funding Sources TRACE-CORE is supported through a cooperative agreement with NHLBI, U01HL 105268; work on this manuscript is also partially supported through the Univeristy of Massachusetts' Clinical and Tranalational Science Award, U54 RR 026088.

Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University is supported through a cooperative agreement with NHLBI, U01HL105270.

Center for Health Insurance Reform, Cardiovascular Outcomes and Disparities is supported through a cooperative agreement with NHLBI, U01HL105342.

Research Coordinating Unit (RCU) is supported through a cooperative agreement with NHLBI, U01HL107023.

Acronym Description

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CCOR

Centers for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research

- RCU

Research Coordinating Unit

- TRACE-CORE

Transitions Risk and Actions in Coronary Events Center for Outcomes Research

- ESI

Early Stage Investigator

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

- GRACE

Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events

- ENCORE

Examining Novel Cardiovascular Outcomes and Regional Effects

- TOP PCI

Translating Outstanding Performance in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- MA

Massachusetts

- VTE

Venous thromboembolism

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures NL Cook: Dr. Cook reports being a full-time employee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which funds and oversees the CCOR program. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, or any other government entity.

DE Bonds: Dr. Bonds reports being a full-time employee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which funds and oversees the CCOR program. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, or any other government entity.

CI Kiefe: Dr. Kiefe has no conflicts of interest to report.

JP Curtis: Dr. Curtis has no conflicts of interest to report.

HM Krumholz: Dr. Krumholz reports being the recipient of a research grant from Medtronic, Inc. through Yale University and serves as the chair of cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth.

NR Kressin: Dr. Kressin has no conflicts of interest to report.

ED Peterson: Dr. Peterson has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Krumholz HM, Peterson ED, Ayanian JZ, Chin MH, DeBusk RF, Goldman L, Kiefe CI, Powe NR, Rumsfeld JS, Spertus JA, Weintraub WS, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on outcomes research in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2005;111:3158–3166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.536102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumholz HM. Real-world imperative of outcomes research. JAMA. 2011;17:306, 754–755. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krumholz HM. Medicine in the era of outcomes measurement. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:141–143. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.873521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Floyd KC, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, Lessard D, Dalen JE, Alpert JS, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. A 30-year perspective (1975–2005) into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with initial acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:88–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.811828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGovern PG, Jacobs DR, Jr, Shahar E, Arnett DK, Folsom AR, Blackburn H, Luepker RV. Trends in acute coronary heart disease mortality, morbidity, and medical care from 1985 through 1997: the Minnesota heart survey. Circulation. 2001;104:19–24. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Goraya TY, Killian J, Reeder GS, Kottke TE, Yawn BP, Frye RL. Trends in the incidence and survival of patients with hospitalized myocardial infarction, Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979 to 1994. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:341–348. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, Schreiner GC, Chen J, Bradley EH, Wang Y, Wang Y, Lin Z, Straube BM, Rapp MT, Normand SL, Drye EE. Patterns of hospital performance in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:407–413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.883256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark AM, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, McAlister FA. Meta-analysis: Secondary prevention programs for patients with coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:659–672. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auer R, Gaume J, Rodondi N, Cornuz J, Ghali WA. Efficacy of in-hospital multidimensional interventions of secondary prevention after acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:3109–3117. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canto JG, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Fincher C, Farmer R, Sekar P, Person S, Weissman NW. Relation of race and sex to the use of reperfusion therapy in Medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1094–1100. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004133421505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pamboukian SV, Funkhouser E, Child IG, Allison JJ, Weissman NW, Kiefe CI. Disparities by insurance status in quality of care for elderly patients with unstable angina. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkat A, Hoekstra J, Lindsell C, Prall D, Hollander JE, Pollack CV, Jr, Diercks D, Kirk JD, Tiffany B, Peacock F, Storrow AB, Gibler WB. The impact of race on the acute management of chest pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1199–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Lessoni LI, Banaji MR. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonel AF, Good CB, Mulgund J, Roe MT, Gibler WB, Smith SC, Jr, Cohen MG, Pollack CV, Jr, Ohman EM, Peterson ED. CRUSADE Investigators. Racial variations in treatment and outcomes of black and white patients with high-risk non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines?) Circulation. 2005;111:1225–1232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157732.03358.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiestand BC, Prall DM, Lindsell CJ, Hoekstra JW, Pollack CV, Hollander JE, Tiffany BR, Peacock WF, Diercks DB, Gibler WB. Insurance status and the treatment of myocardial infarction at academic centers. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:343–348. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao SV, Kaul P, Newby LK, Lincoff AM, Hochman J, Harrington RA, Mark DB, Peterson ED. Poverty, process of care, and outcome in acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1948–1954. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, Pieper KS, Goldberg RJ, Van de Werf F, Goodman SG, Granger CB, Steg PG, Gore JM, Budaj A, Avezum A, Flather MD, Fox KA, GRACE Investigators A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2727–2733. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basu J, Friedman B, Burstin H. Primary care, HMO enrollment, and hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: a new approach. Med Care. 2002;40:1260–1269. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200212000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horlander KT, Mannino DM, Leeper KV. Pulmonary embolism mortality in the United States, 1979–1998: an analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1711–1717. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim SA, Stone RA, Obrosky DS, Sartorius J, Fine MJ, Aujesky D. Racial differences in 30-day mortality for pulmonary embolism. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2161–2164. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.078618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aujesky D, Long JA, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. African American race was associated with an increased risk of complications following venous thromboembolism. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aujesky D, Mor MK, Geng M, Stone RA, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Predictors of early hospital readmission after acute pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:287–293. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]