Abstract

In this study we consider the process of the clinical encounter, and present exemplars of how assumptions of both clinicians and their patients can shift or transform in the course of a diagnostic interview. We examine the process as it is recalled, and further elaborated, in post-diagnostic interviews as part of a collaborative inquiry during reflections with clinicians and patients in the northeastern United States. Rather than treating assumptions by patients and providers as a fixed attribute of an individual, we treat them as occurring between people within a particular social context, the diagnostic interview. We explore the diagnostic interview as a landscape in which assumptions occur (and can shift), navigate the features of this landscape, and suggest that our examination can best be achieved by the systematic comparison of views of the multiple actors in an experience-near manner. We describe what might be gained by this shift in assumptions and how it can make visible what is at stake for clinician and patient in their local moral worlds – for patients, acknowledgement of social suffering, for clinicians how assumptions are a barrier to engagement with minority patients. It is crucial for clinicians to develop this capacity for reflection when navigating the interactions with patients from different cultures, to recognize and transform assumptions, to notice ‘surprises’, and to elicit what really matters to patients in their care.

Keywords: Assumptions, surprise, clinical encounter, cross-cultural care, local moral world, disparities, USA, ethnic minorities, mental health

Introduction

Numerous studies have highlighted how providers may hold preconceptions about patients that are predicated on impoverished notions of group membership (van Ryn & Burke, 2000). Literature in social psychology and racial bias primarily focuses on the unconscious application of assumptions that providers make when they see patients in the clinical encounter (Burgess, Fu, & van Ryn, 2004), describing these assumptions as categorizations (such as race, age, sex, socioeconomic status, etc.) that become “over-generalized”, e.g., when providers rate Black patients as being less educated than their non-Latino white patients (van Ryn & Burke, 2000). Sometimes assumptions are based on trying to label persons seen from an “out group”, such as people who are unpredictable or dangerous, and consequently establish social distance (Angermeyer & Matschinger 2004). In their paper on patient provider communication and health disparities, Cooper and Roter (2003) identify the critical need to explore how these assumptions can occur, particularly in context of the “reciprocal nature of the patient-physician relationship.” They emphasize the importance of recognizing that assumptions can shape the patient and physician relationship particularly in terms of physicians’ assumptions about a patient, which has implications for the care they give. This is particularly true in the context of cross-cultural encounters, where providers might be more prone to rely on stereotyped accounts of certain cultural groups in the presence of significant cultural difference (Dysart-Gale, 2006).

In this study, we explore ways in which assumptions are expressed in initial diagnostic interviews, and how they can shift during these interviews and over the course of reflection in post-diagnostic interviews. This in-depth look at the local interview process and how it is co-constructed illuminates how assumptions by clinician and patient may shift moment-by-moment in the clinical encounter. Developing a capacity for reflection is seen as crucial for navigating different cultures (Kleinman, 2006) and for determining what matters to doctors and patients in care (Frankel, Sung, & Hsu, 2005). When invited to articulate and elaborate what they notice, clinicians and researchers alike can make visible what may otherwise pass by unnoticed, which is useful for the analytic research insights it brings, and can be carried over into cross-cultural care (Katz & Shotter, 1996). We examine this phenomenon as a process “rooted in social space” and seek to illuminate the social and relational aspects of stereotyping, drawing on Kleinman’s emphasis on “moral experience, or what is at stake for actors in a local moral world” (Yang, Kleinman, Link, Phelan, Lee, & Good, 2007, p.1525). Moral experience here refers to that kind of engagement that makes visible “values in ordinary living” (Kleinman, 1999, p.77), or what matters most in the lives of ordinary people. It is this practical engagement that illuminates what is most important for the actors. Rather than fixed and acontextual, we emphasize assumptions as occurring in a relational process that can shift in interaction and reflection on the lived experience of the participants. We view both the ‘one’ who makes assumptions, and the ‘other’ who can be thus objectified, as participants in a process that can be made visible in the course of reflecting upon it.

We expand our exploration of assumptions by patients (as well as by clinicians) with respect to their accounts of being ‘marked’, a term introduced to describe in interactional terms the experience of someone who is viewed as “deviant, flawed, limited … or generally undesirable” (Jones, Farina, Hastorf, Markus, Miller, & Scott, 1984, p.6). A person can be ‘marked’ by his or her appearance, e.g., seen as an indicator of his/her level of education. Domains of assumptions can thus expand beyond gender, race and culture to include appearance, markers of class and education, as well as style of presentation (e.g., aggressive, cold, inarticulate, smart); an individual can be ‘marked’ by a negative assumption. Following Goffman (1963), being perceived as possessing such an aspect is “deeply discrediting.” But he continues, “it should be seen that a language of relationships, not attributes is really needed” (ibid., p.3), for such ‘marks’ are constructed within the doctor-patient relationship. Harré agrees that assumptions “can only be understood when placed in their conversational context” rather than the “ widely shared consensus that it is something that is located ‘inside’ people” (van Langenhove & Harré 1999, p.130).

This shift of focus – from influences located in individuals to those located in relationships – opens up the possibility that a shift in a clinician’s way of relating to a patient may influence how that patient is seen. If we examine the clinician as anthropologist, we can draw a parallel between the two as they navigate between the different ‘moral worlds’ of patients, the institutional and professional requirements of the clinical intake, and what is at stake for each in this process. In the event, the clinician necessarily becomes “self-reflexively critical of her own positioning” with its obligations and challenges. This move toward reflection from within a practice – ‘seeing’ herself in relation to her patient – arouses a creative tension that “destabilizes stereotypes and clichés and makes her attentive to the original and unexpected possibilities that can (and so often do) emerge in real life” (Kleinman, 1999, p.77). It is this creative tension that we would like to emphasize as the key to shifting assumptions.

In exploring the lived experience of the clinical encounter in safety net clinics, (clinics that provide a disproportionate share of healthcare to uninsured, Medicaid, poor and other vulnerable patients), we seek to describe how stereotypes occur in naturalistic settings. Research on these issues “may help us understand how basic social processes, rather than simply poor training or clinician prejudice, contribute to problems of assessment associated with class and ethnicity” (Good, 1997, p.240).

Methods

Sample

The sample in the current study is part of a larger Patient-Provider Encounter Study (PPES) (Alegria, Nakash, Lapatin, Oddo, Gao, Lin, & Norman, 2008) composed of both providers and patients in intake sessions conducted in 2006 – 2008. All patient participants were seen for initial evaluation by a group of 47 providers who agreed to participate in the study from eight clinics in the Northeast of the US, most of which were safety net or served low income populations, and all of which offer services for many uninsured patients, working families, and recent immigrants, with approximately 55% of the outpatient service volume attributed to Medicaid or uninsured patients. The clinicians provide mental health services to adult populations in outpatient and language specialty clinics; interviews are conducted in English or Spanish based on patient preference.

We targeted those providers who offer mental health services to multicultural populations in general outpatient clinics as well as clinics that specialize in substance abuse treatment, representing a diverse disciplinary background and a varied level of experience: about 28% were psychiatrists, 26% psychologists, 38% social workers and 6% nurses or others. Approximately, 66% were females, and 70% had six years or more of experience in practice. In the study, 53% of clinicians self-identified as non-Latino whites, 36% as Latino, 9% as non-Latino black (African American or Afro-Caribbean); and 2% as Asian. In 64% of the cases, the patient and provider were matched on ethnicity/race.

129 patients from adult mental health outpatient clinics participated in the PPES study from diverse backgrounds: approximately 50% Latino, 12% Black (African American or Caribbean) and 39% non-Latino White. Ages ranged from 18 to 65 years, with 80% of them between 18 and 49. Approximately 60% were females and 65% had completed high school. More than 64% had a household income of less that $15K, and approximately half of the patient sample was unemployed or out of the labor force. The Institutional Review Boards at each site approved the study prior to data collection, obtaining written informed consent from all participants. Capacity to consent was established using a 10-item screening measure based on four legal standards of demonstrating capacity (understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and voluntarism) (Zayas, Cabassa, & Perez, 2005).

Procedure

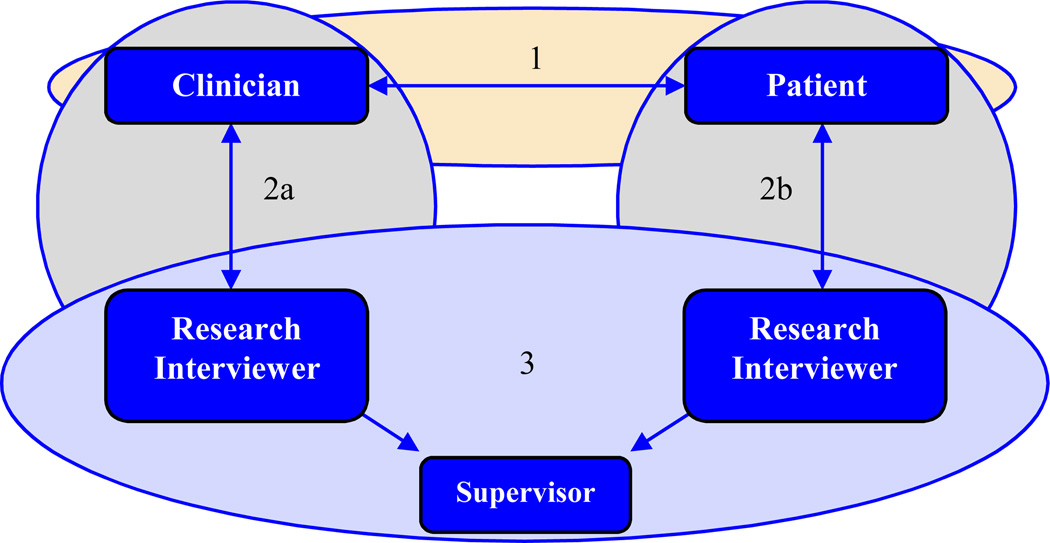

The PPES study consisted of three components (#1–3 in Figure 1.) Diagnostic intake interviews (#1) were videotaped. Subsequent research interviews were conducted separately with patients and clinicians using a semi-structured interview guide, lasting approximately 30 minutes and focused on understanding patients’ and providers’ experience during the initial clinical interview. Provider interviews (#2a) and patient interviews (#2b) included questions regarding the understanding of patient presenting problem, process of clinical decision making, development of rapport with patients, and the role/significance of socio-cultural factors in patient’s presenting problem and care offered and sought. All interviews were conducted by trained research assistants in English or Spanish according to participant preference; they were audiotaped and fully transcribed using a professional service. Training was provided by the first author (AK) throughout the data collection process, and took the form of reviews (#3) of particular interviews identified by the research interviewers described below.

Figure 1.

The reflecting process: 1) a diagnostic interview between clinician and patient; 2) pairs of post-diagnostic interviews between (a) research interviewer and clinician and (b) research interviewer and patient; 3) a joint follow-up interview between the research interviewers and their supervisor, the first author.

Format

The research interviewers met with (AK) to review the video of the original diagnostic interview as well as the transcripts and audiotaped post-diagnostic interviews that they had conducted with the clinician and the patient. Through this process of triangulation, this research team systematically compared and contrasted transcripts, audiotapes and videotapes (initially individually, then jointly) as part of an iterative interpretive process. Through “purposeful sampling,” we identified exemplars, that Patton (2002) refers to as “information rich cases… those from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the inquiry.” (p.230).

We present in detail two exemplar cases in which there was a marked shift of assumptions. In a landmark paper on medical interviewing, Mishler and colleagues chose two contrasting interviews to demonstrate “the language of attentive care” for systematic comparison (Mishler, Clark, Ingelfinger, & Simon, 1989). We similarly choose two cases that are striking exemplars of the process by which assumptions can shift in the interaction between patient and clinician in the course of a diagnostic interview, recalled in the post-diagnostic interview and reflected upon in review sessions. These multiple comparisons deepen and elaborate the ways in which assumptions are expressed and can shift.

These cases are not just an instantiation of a category but can be seen as constitutive of a special process of interaction between a provider and their patient (or research interviewer and patient or clinician) (Radley & Chamberlain, 2001; Mishler, 1990). The contribution of in-depth case study is more than “reporting upon a unique object but a way of setting forth those meanings that were portrayed or presented by the investigator” (Radley & Chamberlain, 2001). The research team examined how these meanings evolved and arrived at themes through systematic comparison of audio and video-taped interviews, written transcriptions, researchers’ observations and modified field notes. Cases chosen portray and contextualize these themes.

Case Exemplars

The cases discussed in this paper come from provider–patient dyads participating in PPES interviews (see Figure 1). As our purpose is in part to examine the stance of clinician as anthropologist, joint meetings with research interviewers created a forum within which to develop the capacity for inviting reflection on the part of clinicians and patients. We follow Mishler (1990) who argues for the role of exemplars in inquiry-guided research. There are many forms of narrative inquiry as a way of finding new meanings for illness experience or diagnostic medical encounters. In our exemplars, we focus on mutual inquiry in which our research team identifies narrative fragments or striking moments that invite further elaboration of meaning and identification of cases. Pairs of research interviewers were asked to reflect on their post-diagnostic interviews and select those cases that they consider to be most striking, challenging or notable, e.g., those that most clearly demonstrated a shift in assumptions, preconceptions, or stereotyping, those where patients became strikingly articulate, and those in which patients and clinicians demonstrated a notable willingness to reflect on their own experience. We emphasized the importance of an ‘ethnographic sensibility’, using ethnographic methods demonstrated by capacity for reflection, participant observation to some degree, and close attention to context, people, posture. Case finding builds on this reflective/reflexive capacity.

The exemplars begin with an initial summary, then excerpts from the post-diagnostic interviews, followed by reflections from the joint interviews which illuminate aspects of shifts of assumptions. Those interviews conducted in Spanish were subsequently reviewed in Spanish by the authors and research interviewers.

The First Case Exemplar

The Diagnostic Interview

The patient, a young English-speaking Latino man from Central America, is interviewed by a female Caucasian clinician from the US. In the videotaped intake interview the clinician begins by administering a set of survey questions required as part of her outpatient clinic’s evaluation protocol. After approximately half an hour the patient becomes noticeably upset (crying). The clinician shifts her stance away from the survey and begins to comfort the patient, who then discloses his reasons for seeking help: his concerns about his current relationship and physical abuse. The clinician is moved by his expression of emotion, which brings them into a more immediate contact. Each suspends their prior judgments that could otherwise have affected their capacity to engage with ‘the other’. Instead, by the end of the interview, they talk about his returning for further meetings with that clinician.

The Post-Diagnostic interviews

The following quotes come from transcripts of the two post-diagnostic interviews between a research interviewer and the patient, and a second research interviewer and the clinician. We juxtapose the words of clinician and patient as they reflect back on the diagnostic interview. They each begin to talk about the assumptions they came in with, and how they shifted during the interaction in the course of the interview.

| a. In the post-diagnostic interview the patient talked about his assumptions… | a. The clinician shifted her assumptions, and ended up feeling very connected… |

| “I grew up with girls all my life… | “Before he came in, |

| I don’t open up to my sister or my mother. | I was thinking I’d refer him to substance abuse. |

| I don’t open up to girls. | |

| The only person I really talk to are boys… | After I met him, I thought he could work on |

| I don’t really open. | |

| All my counselors were all guys. | a more sophisticated level |

| It would be worth the effort.” | |

| b. But was subsequently transformed | |

| “I felt pretty connected | |

| I just felt comfortable. | I was impressed.” |

| I feel like she wasn’t quick to judge me, like throughout all my life people have judged me. | |

| And she didn’t judge me. | |

| I’ve been around a lot of people who judge me when they look at me | At the end of the interview, this clinician asked the patient about the meaning of his tattoos. |

| …you can tell from their vibe. | |

| She didn’t judge me. | |

| That’s why I felt ‘mad comfortable’. | |

| … I would think she was scared of me or something. | |

| But she wasn’t. She was nice.” |

The Joint Interview: a Reflecting Process

We notice that both patient and clinician reported their experience of coming in with assumptions that shifted in the course of the diagnostic interview, which were acknowledged for the first time in the course of the post-diagnostic interviews. Prior assumptions changed: for the clinician, the patient’s appearance (e.g., tattoos; looking like a ‘thug’) had led her to believe that this was a person with substance abuse and had preconceptions of him being a case that she did not want to treat. By her own admission, she shifted to seeing him as a person (not a member of a category), somebody worth her time and “worth the effort”, who could “work on a more sophisticated level”.

The patient had his own assumptions that shifted in the course of the interview; the clinician’s gender, which led him to believe that he would not be able to open up and share his feelings, as well as his expectation of discrimination. We notice that in addition to ethnicity, other assumptions are also at play. As we shall see, it was not just the attributes of the individual— how they ‘looked’—but rather how they came to be ‘seen’ as people. What could have been a barrier shifted to make visible what mattered most to this Latino patient and made it possible for him to engage in care. Clinician and patient came away from the diagnostic interview wanting to continue to work together.

In the post-diagnostic interview, the patient remarked on the effect of his background, how people have treated him, and how he has previously experienced people “going weird around me”:

“Not that I can remember but I know it has happened to me.

People get like kind of weird around me.

Yeah, that happens everywhere,

and there is nothing you can do about it.”

Though his appearance (e.g., tattoos, dress) was notable (i.e., could ‘mark’ him), his use of language about what mattered became compelling.

It is worth elaborating on how an interviewer can best create the atmosphere for this kind of reflection in which there might be a shift in assumptions, a change in experience, allowing clinicians to stay engaged, laying the groundwork to invite the patient to articulate their concerns authorizing its further expression. In his post-diagnostic interview, the patient reported wanting to be seen as a person, not a category…

“… as a person, not feel stereotyped.

Because if she does do that, it’s almost as if she’s stereotyping me…

putting me in a category: ‘OK here comes the Hispanic’.”

The clinician also recalled this patient saying that he has experienced people as being “scared of him” and that he usually doesn’t like to see women therapists. Remarkably, she experienced a similar sense that, “I didn’t think I’d [want to] see him, but now I really want to see him.”

The contrast was striking between the way the clinician described her level of engagement with the patient at the end of the diagnostic interview and in the first half of the interview, which was mostly survey-driven in that her attention was focused on the protocol. Thinking back to the diagnostic interview, she recalled the patient crying (as he spoke about his experience of abuse), which shifted her out of her fixed stance long enough to change how she interacted with him. As they talked about personal abuse, the clinician was moved when the patient started to cry. From the video, we notice that it was fully 28 minutes into the interview (as the clinician paused in administering the survey) before this patient had the opportunity to talk about what really concerned him: his relationship with his girlfriend. The clinician put the survey aside and made the time to be much more responsive to what mattered most to him. She reflects on this in the post-diagnostic interview:

CN: “… at that point… you have to empathize

you’ve got to stop and give him some time to do that

So there were breaks in the interview allowing him time

to have his emotion…

and to uh, try to empathize with that.

It also happened when he talked about his girlfriend…

It was obvious the pain he was feeling,

so a decision had to be made, to just stop, wait

and empathize and allow that. Accept that….”

He could then elaborate on what was most important for the clinician to understand,

PT: She should understand what I’m really telling her.

What I want to get out of it.

She should understand that.

If she can’t understand it, then she can’t help me.

In the course of his upset, the clinician made the decision to give him time and space to express himself; he responded with a vivid description of how his thoughts went around and around…

PT: I find myself questioning myself. It makes me so mad

CN: It makes you angry… something in the back of your mind is telling you negative…

PT: I’m depressed

CN: So this is an awareness that you have—you’re not hearing voices?

PT: No. This is an awareness, my thoughts

In the post-diagnostic interview, he was struck by this moment of “having never thought of the distress of recurrent thoughts as ‘awareness’”. As he reflected with the research interviewer, he elaborated how this made him feel particularly understood, and he now carries it with him…

“… because I was telling her …

that I get so many thoughts

and she said that it was ‘awareness’…

she just got it right on point.

That was something… ‘awareness’.

I didn’t know it was awareness…

that I’m always aware of something

And I never knew that.

He further elaborated on the relationship with this therapist as one in which he would want to be an active participant…

I think if I was to build a relationship with her [CN]

it would have to be me.

I would have to open up.

That’s [not] her job to do that.

If anything, it’s me. If I wanted to make a relationship I could;

If I don’t want to build a relationship, I won’t.

By the end of the interview there was a shift to a more two-way process, a mutual inquiry; as the clinician leaned forward and began asking him about tattoos. This shift is recalled by the clinician in the post diagnostic interview; reviewing the video of the diagnostic interview, the research team noticed how the clinician asked, in a way that showed interest in learning from him:

CN: So what’s the meaning of all these tattoos? You’ve got letters… what is this one?

PT: Inner rage

CN: Inner rage?

PT: When I get mad I felt I had to express it.

CN: So you’d look at that…?

PT: Yes

CN: Does this make you feel it’s a symbol of that?

PT: It’s a symbol.

CN: What does this mean?

PT: My last name.

CN: Oh. Oh, I’m looking at it upside down (laughs)

PT: … my sign of the zodiac.

CN: [repeats zodiac sign]

On the video we notice how the clinician pauses, her tone changes as she leans forward, shifts her fixed orientation, and spontaneously offers him a next appointment.

CN: There is hope.

PT: I hope so.

CN: Anyone who wants to do better and is willing to work at it can. And I know for a fact that’s true.

Local worlds: what’s at stake

The crucible of the clinical encounter allows us to realize what is at stake for both patient and clinician. The clinician is multiply accountable: both to organizational requirements, e.g., administering a survey, and also being attentive and engaged with the lived experience of the person in front of her. Over the course of the diagnostic interview, there was a shift in language and in engagement—with the clinician acknowledging the wisdom of ordinary talk—moving from privileging professional discourse, a more expert tone (“do you know what anxiety means?”) and cultural assumptions (was abuse a “cultural thing?”) to wanting to learn from the patient, “what does abuse mean to you?” and a genuine concern for what mattered most to him (“it takes a long time to learn about relationships”). Rather than his adapting to the psychologizing discourse, she entered into and acknowledged his suffering. Despite time constraints, she decided to “give him the time” to express what mattered to him. In the way she talked with him about the meaning of his tattoos, demonstrating that she wanted to learn from (and with) him in a non-threatening manner, she shifted from viewing tattoos as ‘marking’ him, e.g., as a member of a particular category or class (Jones et al., 1984), to see him as a person and acknowledge what was important to him. Her willingness to enter into his ‘world’ stood in stark contrast to his description of how he is usually seen (his prior experience of discrimination). In the diagnostic interview, he had spontaneously offered that he could not go back to Central America, that it would be dangerous: because of how he looked (e.g., the tattoos), he risked being seen as a gang member.

The Second Case Example

In exploring the experience of assumptions as a social phenomenon, we become aware of the context, the particular circumstances in which it occurs, in a particular “local moral world” (Kleinman, 1999, 2006). “The focus on moral experience… allows us to see both as interpreting, living, reacting with regard to what is vitally at stake and what is most crucially threatened” (Yang et al., 2007, p.1530). We seek to explore these social or processual aspects of assumptions in the clinical encounter. Prior assumptions can be noticed by each of the participants during the course of the interview; they can enter the interview room unawares, or arrive through events reported by others even before the clinician ever meets the patient, as we shall see in the following example.

The Diagnostic Interview

This interview with a young Latina woman from Central America was conducted in Spanish by a Latina clinician, also from Central America. She was alerted by a staff member about an incident in the waiting room in which the patient was seen kissing her boyfriend in a way labeled by them as ‘inappropriate’.

“This isn’t done here! This is a public space… We don’t want to make other patients uncomfortable” (fieldnotes).

This unwittingly formed the background for provider assumptions about the patient to be interviewed, but one that shifted in the course of the interview, with remarkable effects. This shift opened the way for the clinician to engage with the patient who painted a picture of suffering, trauma and what was at stake for her.

The Post-Diagnostic Interviews

Reflecting back with the research interviewer on the diagnostic interview (also conducted in Spanish), the clinician recalled how the incident reported by the receptionists could have compromised how she would ‘see’ her patient:

CN: At that time I said to myself: “Oh! Hmmm! This is weird.” What will happen? There was some rolling of the eyes [by the staff] and I was thinking: “What am I going to find myself with? Who knows what type of case I’m going to see.” … I was not getting into the best empathic situation [laughs], but that changed. That was at the beginning.

She elaborated on this initial assumption, noting the patient’s appearance and ‘wondering’ about it, but “all of that changed”…

CN: She has long hair, but cut around here [makes hand gesture] and wears it in a way that covers her eyes, and then I thought, “Hmm, what is this all about?” But all of that changed. You get there with some resistance but then you forget about it, you get into what they’re telling you and try to understand.

INT: Did that affect your interview with her? The impression you had of her from the beginning before getting to know her?

CN: Maybe a little bit, hmm, like being a bit resistant at the beginning, like “Oh! What is this all about?” I wasn’t looking forward to it… I don’t know [pause] maybe I was resistant. I’m not going to say that I adopted an attitude of rejection towards her … I took her in and when she was seated… I didn’t have the forms. So I had to leave the room and then forgot about the whole issue and I got into… It’s such a compelling story that it was a shift from what I was witnessing.

This clinician reflected at length on the reported incident in the waiting room and how this initial point of entry stayed with her throughout the first part of the diagnostic interview. When invited by the research interviewer, she elaborated on how such assumptions can affect an interview: making her “resistant” to engaging in an “empathic” way. We are struck by how the clinician is explicit about her preconceptions and how they shifted; she noted that this form of reflection during the post-diagnostic interview illuminates the process of shifting assumptions that might otherwise pass by unnoticed. She then talked of becoming engaged by the patient’s story and entering into it in such a way that there was a shift from the fixity of her initial judgments. Rather than representing the patient as “resistant,” she articulated her own experience and witnessed this patient in a very different way than what had been said ‘about’ her by others. In elaborating on it, she noticed how this prior interaction with the staff could have constrained her capacity to engage in what mattered most to the patient.

Her very explicitness throws into question views frequently expressed in the literature (van Langenhove & Harré, 1999) that assumptions and stereotypes are implicit cognitive processes that are very difficult to change. By shifting our locus of inquiry to actual clinical encounters in real time and by creating the conditions for dialogue and reflection in post diagnostic interviews, we find clear evidence that participants can become interlocutors on a process that makes the shift visible and possible.

Indeed, in dialogue with the research interviewer, this clinician deepened her reflections as she remembered her sense of how it changed her practice in the way she usually conducts her diagnostic interviews. She changed from seeking to fit what occurred into fixed diagnostic categories—“I wonder if she’s a borderline”—to noticing that there was “more,” and by acknowledging what was at stake for the patient in her life, an appreciation of her social suffering, and with it a major shift in her own capacity to engage with her:

CN: Then, clearly one begins to think, “Hmm, I wonder if she’s borderline.” But there is more… her difficulty, in tolerating affect with all she has been through… there was an “Ah! This woman who sends her son [away] because he can not get along with her boyfriend,” a sensation of such empathy for this woman who had lived [through] so much.

She carefully tracked this shift—from listening for a diagnostic category to listening to the lived experience of the person in front of her, acknowledging her social suffering, being attentive to the phenomena as it unfolded between them.

CN: … it is complicated. Totally, I changed my way of seeing her, from how I felt at the beginning, to how I felt at the end.

This shift from a fixed professional stance—changing her usual scheme of doing a diagnostic interview—happened very quickly:

CN: Because we began to talk, I usually follow this scheme so that… a little to get all the information that they ask for the evaluation, … follow[ing] that order that they present here. With her, I didn’t do it. When she told me what brought her here, and she told me a little of her hospitalization, of where they treated her, of her being groped by another patient… her being discriminated against, her history, her family, how it was … I made the decision to let her go [a ella la voy a dejar], let her more or less guide the interview towards what was important to her, … very quickly she started to talk about how terrible her history had been.

This shift had been signaled by the patient’s first words, “Mi vida ha sido bastante complicada” [“My life has been very complicated”]. The clinician reported that “me llamó la atención” [“I was struck by these words”.] It changed her usual practice as she instead left the patient to talk [“yo la voy a dejar,”] following her lead:

INT: Instead of following the schema you normally use. [CN: Mmmhhh (implied yes)] When exactly did you make the decision to say, “Okay, I will let her go on [talking].”

CN: Because the first thing she said, the first, the very first, “My life has been very complicated” Hmmm, that got my attention [‘called’ me]. After she spoke of depression… about her son who left but after that she spoke of her adolescence, an adolescence so difficult… then, instead of saying, ‘but tell me now… you’ve felt depressed since when?’ No, let her talk… [déjala hablar] because maybe that gives more information about the symptoms that they present; and I felt that she needed to talk. She was crying, and before, the more she talked the more she cried. She also said that she could do this finally in Spanish… and here, [at a clinic serving Latinos] [chuckles] Ay how beautiful! That here, she could speak [Spanish] and didn’t need to worry… and I said to myself, “this woman, I will not stop”.

As in the first exemplar, this clinician determined to invite the patient to talk, giving her the space and time to express what was most important for her. She chose not to interrupt the patient while she expressed herself [“this woman, I will not stop”.] In response to being authorized, the patient spoke eloquently of her suffering—how traumatic her life had been, and how much she needed to speak in her own language, at her own pace. The clinician was moved by the patient’s world of suffering, commenting that “es una mujer que ha vivido en estado de terror” [“this is a woman who has lived in a state of terror”].

Assumptions and surprise

Remarkably, at the end of the post-diagnostic interview, the clinician again spontaneously returned to her initial experience with this patient—recalling the effect of entering the interview with assumptions, and then her experience of transformation. As part of the reflecting process, she was able to elaborate and refine what had occurred, describing it as a “major shift… a 180 degree change.”

CN: Maybe now that we’re talking more about this… I think there was a shift, a major shift in beginning with her… a change big enough with everything that happened before we got the chance to do the interview, before seeing her and what happened in the session and how I felt at the end of the session towards her …was like a 180-degree change.

INT: Has something like this happened to you before with other patients?

CN: Yes. I think the day it stops [being] surprising it’s going to be a problem… I am like assuming too much the day that one doesn’t get surprised, but not a lot with respect towards the way I felt with this patient. No, patients always surprise you, there are other stories, other days, but the way I felt—like, “Oh my God! She’s kissing with him… and the man with his face beat up… I don’t know if I want to do this.” And then starting the interview and the “empathy that I felt for her afterwards…”

Typically, categorization “minimizes surprise; allows us to treat things as if they were the same as what we encountered before” (Amsterdam & Bruner, 2000, p.21). Here, this clinician makes an important link between assumptions and surprise. We have argued elsewhere—in reporting on a pilot study of the use of an ethnographic practice resource in a cross-cultural training program for primary care residents—that the process of reflection on diagnostic interviews in which people are invited to talk of what is striking and unusual, often serves to shift them from a fixed disciplinary discourse to surprise and engagement (Katz & Shotter, 1996).

Multiple reflections

The patient in this second exemplar, reflecting in the interview, noted, appreciated, and resonated with the clinician’s judgment call—to let her talk, in her own time, in her own way, without stopping her. She was moved by this, seeing it as a sign of how well the clinician listened and understood; this authorized her further eloquent expression She reflected on her experience in which the clinician listened “hasta que ella veía que usted paraba y ella escuchaba, estaba atenta” (“until she saw that you had paused/stopped, and she listened, she was attentive.”). The patient saw her clinician as attentive throughout, acknowledging what was most important to her. Interestingly, they each picked out the same striking moments of resonance in the interview.

| PT: She gave me space, she didn’t interrupt me, she left me so that I could explore, [she did] not stop me… until she had a question, then she asked it… | CN: I made the decision to let her go. Let her more or less guide the interview towards what was important to her, afterwards I returned and filled in what was missing, or we returned to elaborate themes |

| PT: I felt listened to, on the contrary, I felt comfortable if you understand me, because I cried until I couldn’t [any more] because I can never talk about my past without crying… | |

| CN: She was crying, and before, the more she talked the more she cried. She also said that she could do this finally in Spanish…and here [at a clinic serving Latinos] [chuckles] Ay how beautiful!” |

By juxtaposing what the patient and clinician state in their post-diagnostic interviews about what they found most striking in the intake interview, we can begin to map the landscape of features to be found within local moral worlds, an opportunity for patient as anthropologist. A quality of “connection” with the patient, which Kleinman and Benson (2006, p.1676) call “elective affinity,” allowed the clinician to explore what mattered to her (and, as we have seen above, allowed the therapist to be responsive to it). It extended to how the clinician asked her questions—being attentive and respectful and doing so only when there was an opening. The research interviewer asked the patient to elaborate on “what’s in the word… congeniamos” [“we got on”]. The patient experienced this as a kind of understanding, in which “… when I spoke, she looked me in the eye … One feels listened to and understood, and I felt that with her, because once I had a therapist…”

This level of engagement, a key aspect of “affinity” is experienced by the patient as critical; not only did it invite her to talk about traumatic events in her life but also how a previous encounter with a therapist had itself been traumatic. This had profound implications. Despite her suffering since that initial encounter, she did not return to seek help until now. Affinity is a two way process; the patient experiences the current clinician as affording her the opportunity to offer a contrast with what did not work in the past. We notice how acknowledging what was critically important to the patient invites her to talk about her suffering:

PT: And that was what made me worse also because if in that time I would have been treated I would not have gotten to the extremes that I have now.

In contrast with another patient in the PPES who reported feeling “examined” and “interrogated” by a therapist who possessed a “threatening aura”, this patient speaks of the importance of “being looked in the eye”, and “knowing how to wait” as a sign of being listened to. This description resonates with the clinician’s decision to let the patient talk until she is ready to stop, while this patient points to her experience of the importance of the clinician giving her space, never interrupting her

Barriers to Engagement

We draw attention to the distinction made in the previous section—between being looked at as an object, vs. a felt sense of being ‘seen’, ‘met’, and engaged with, i.e., the way in which the clinician looks at patients can make them feel safe or it may be experienced as threatening.

PT: They [Drs] stare at you too long

INT: So staring too long is no good.

PT: Yea ‘cause it’s like you feel I’m being interrogated.

This affects the patient’s ability to express herself. Note that her capacity to ‘articulate’ her concerns is a relational process; patients are indeed influenced by clinicians. As this patient says, they are less likely to express what matters most to them if they feel they are being “interrogated.”

PT: ‘cause that’s what scares you the most. They stare at you and they’ll be asking you and you’re trying to do something, “how am I supposed to word this?” And then they get all stressed… like being interrogated by a police officer…

Instead, she goes on to describe the importance of helping patients “find the words.” This is in marked contrast to the capacity of her provider to locate the ability to articulate as co-created between the two—rather than as an individual limitation. Indeed, the provider characterized this patient as “under-educated,” and commented negatively on her appearance—“she looked like a teenager with the big oversized T-shirt and pants and tennis shoes”—making certain assumptions about the patient which can affect care options and recommendations for disposition (“I really do think people like her might be looking for a quick fix”).

It is uncanny that the patient picks up not only on how she is ‘looked at’, but the “aura” of a clinician, and the extent to which it can invite her to speak or render her silent.

PT: … it’s kind of hard to say, ‘cause if I’m trying toward something and she’s asked me if this is what I mean… maybe she can help me answer the question I am asking.”

The patient is asking for ways to invite her to articulate what is at stake—authorize her voice – which the research interviewer is clearly doing but which the patient did not experience in the intake interview. It is the kind of engagement that invites further elaboration.

PT: I think you get more out of it if you don’t feel scared.

Just sometimes the aura of a person could scare the other person into,

how are you going to say something?

They look at you the wrong way, or they stare at you….

The way they make the other person feel.

Maybe it’s just them, but we as patients don’t know that.

Discussion and Conclusions

As we noted above, stereotyping of minority patients may lead to service disparities (Balsa & McGuire, 2003); clinicians’ assumptions can act as a barrier to access and prejudice can affect the care provided (Escarce, 2005). Patients can perceive assumptions as narrowing clinicians’ capacity to acknowledge what matters most for them, and as preventing them from entering into their local world. Unless patients feel that clinicians can understand, feel, and respond to their problems (Kleinman & Benson, 2006), they can feel reluctant to return for further treatment (Burgess, et al., 2004).

PT: But also it is horrible to feel that you are not being listened to, that one is talking and that, it is as if you were talking [to yourself], that is not nice.

It is important that clinicians demonstrate a particular kind of engagement, a special kind of listening, not just to acquire information useful for an evaluation, but to be attentive to patients in a special kind of reflective fashion that leads them to notice how their own assumptions can constrain that attentiveness and ‘affinity’. Affinity is more than a technique, the quality of eye contact,’ active listening, or being non-judgmental; in certain ways more than an ‘empathic approach’. It is a profound level of engagement with an ‘other’, a form of acknowledgement that what matters to this person is valid and worth the time to explore. We have learned from patients and clinicians in this study that it includes ‘understanding’, ‘engagement’, being ‘seen’ rather than looked over (as an object). The person becomes visible as a person rather than a member of a stereotyped group. We have seen how our process of reflection invites and develops the expression of affinity, as well as the importance of it being authorized.

This kind of seminal attentiveness is shown by the clinicians in both cases as they shift from automatic professional discourses and begin to listen instead to the voice of the patient, to what was said, and to what it was necessary to leave unsaid. In the words of the second clinician, she shifted to “la voy a dejar” (“to ”) in their own time, in their own way, rather than stopping them. In the reflecting process described in this paper, we have encountered many examples of the way in which patients and clinicians can, and do, make assumptions and judgments in their interaction and in the social space between the two. Interestingly, we have found notable that as patient-clinician pairs reflected in the post-diagnostic interviews, they often pointed to similar moments that they were struck by in the diagnostic interview, when critical concerns were attended to and when they were not. Indeed, as Frankel argues, “we do not know much about what patients feel or experience during their medical encounters, and thus the assertion that patients and family members do not have ideas about what is the matter and what to do about it is an unsubstantiated stipulative claim” (Frankel, et al., 2005, p.S-33).

By inviting both patient and physician to review their own encounter, democratizing research “gives participants equal access to the data of their own performance and invites reactions and responses to those performances using the same research criteria.” (Frankel, et al. p.S-33) In so doing, Frankel similarly reports that patient and provider often identify the same concerns and striking moments in an interview, and he links it with their capacity for discernment, for accurate judgment calls and recognition of potential misunderstandings: “It is relatively easy to see how one point of view without the other can produce biases or even inaccurate judgments about the motivation or goals of each person” (Frankel, et al., 2005, p.S-34).

In this article we have seen how shifts away from assumptions can promote engagement; it is a moral act. Examining the effect of over-reliance on the categorical, it is important to attend to the effect of how a disciplinary stance can risk “professionalization of human problems”, whether as psychiatric disorders or academic codes which, Kleinman suggests, can cause those who suffer to “lose a world” – i.e., what is at stake for them in living, in their local context. We need to be alert to the role of clinician as ‘expert’ who can contribute to the process of inauthenticating social worlds, of making illegitimate the defeats and victories, the desperation and aspiration of individuals and groups that could perhaps be more humanely rendered, not as representation of some other reality (one that we as experts possess special power over), but rather as evocation of close experience that stands for itself” (Kleinman, 1995, p.117).

Clinicians with a role as expert bring the requirements of performing a task within a social encounter but also the demands of being accountable as experts in diagnosis and treatment formulation. These are often competing demands (time, checklist protocols and other organizational requirements) where the emphasis on the latter elides the process of the former— that is, rapport, understanding of what matters most to the patient. However, we need to challenge the paradigm that there is insufficient time, as indicated by clinicians in both cases who “decided to take the time” to be attentive to what matters to their patients despite organizational constraints. This is clearly in need of more systematic study. The costs of failure to return to care, particularly of minority patients, need to be taken into account. It would be ideal to have the possibility to study a wider spectrum of actors, including staff and other personnel but that was beyond the scope of the primary study.

As we see it, it is important to promote an atmosphere for reflecting from within the process of an interview. This is similar to the practice of adopting an anthropological sensibility, the stance of a ‘small’ ethnographer. What invites this process of reflection? The process of research interviewing and case development amongst our research team described in this paper involves: 1) noticing, being struck or compelled by a moment in the interview; 2) articulating these “arresting moments” in dialog with another person; 3) elaborating and refining what is thus made visible; and 4) creating the opportunity for relational engagement that can be carried over into subsequent interviews. (Katz & Shotter, 1996.) This process of reflection is iterative: what is articulated in dialog, e.g., in training, research, or supervisory contexts, can serve as a ‘resourceful reminder’ in other contexts.

While we are not suggesting that everyone should go through this process of post-diagnostic reflection in a formal way, we are suggesting here that this is one way in which we might enable ‘experts’ (clinicians) and authorize patients to build an ethnographic understanding, an understanding that will further the ends of clinical knowing particularly in cross-cultural care. Thus, by sharing our research findings here, about what can happen in a clinical encounter, we hope that clinicians (and researchers) can benefit from our portrayals of the results we have observed as arising out of the reflecting process we have described above.

Creating the opportunity to track these resourceful reminders, e.g., noticing “what they are struck by”, allows clinicians to shift from assumptions (thought to be fixed) to noticing what is at stake for the person of the patient. If we were to ask our clinicians or researchers one opening question to make visible the experience and effects of stereotyping, it would be “what were you struck by?” or, “were there any surprises, and if so, what were they?” Building a capacity for reflection amongst research interviewers and clinicians serves to illuminate the process of interviewing, enhances the capacity and willingness to be surprised, and explores ways in which stereotypes get expressed in the diagnostic interview, and how they can shift, e.g., by being attentive to what is particularly at stake in vulnerable populations (e.g., trauma, social disruption, psychosis), opening up possibilities of clinician training emphasizing moral engagement with the suffering of patients.

Acknowledgements

The Patient-Provider Encounter Study data used in this analysis was provided by the Advanced Center for Latino and Mental Health Systems Research of the Center for Multicultural Mental Health Research at the Cambridge Health Alliance. This study was supported by NIH Research Grant #1P50 MHO 73469 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and #P60 MD0 02261 (NCMHD) funded by the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities. We are grateful to our interlocutors, Peter Guarnaccia, Elliot Mishler and Catie Willging, for their comments on earlier drafts, and to research assistants Yaminette Diaz, Frances Mendieta, and Sheri Lapatin, for their contributions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Arlene M Katz, Dept of Social Medicine Harvard Medical School Boston and Center for Multicultural Mental Health Research, Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School, arlene_katz@hms.harvard.edu.

Margarita Alegría, Center for Multicultural Research, Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School.

References

- Alegria M, Nakash O, Lapatin S, Oddo V, Gao S, Lin J, Normand S-L. How Missing Information in Diagnosis Can Lead to Disparities in the Clinical Encounter. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice. 2008;14(6) Supplement:S26–S35. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000338384.82436.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsterdam AG, Bruner J. Minding the Law. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Labeling – stereotype – discrimination: an investigation of the stigma process. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0903-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa A, McGuire T. Prejudice, clinical uncertainty and stereotypes as sources of health disparities. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22(1):89–116. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJ, Fu SS, van Ryn M. Why do providers contribute to disparities and what can be done about it? JGIM. 2004;19:1154–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Roter D. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. IOM, Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. Patient-Provider Communication: the effect of race and ethnicity on process and outcomes of healthcare. [Google Scholar]

- Dysart-Gale D. Cultural sensitivity beyond ethnicity: a universal precautions model. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences & Practice. 2006;4(1) [Google Scholar]

- Escarce J. How Does Race Matter, Anyway? Health Serv Res. 2005 Feb;40(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00338.x. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel RM, Sung SH, Hsu JT. Patients, Doctors, and Videotape: A prescription for creating optimal healing environments? J. Alt. Comp. Med. 2005;11(Suppl. 1):S31–S39. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.s-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. N.Y.: Simon and Schuster; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Good BJ. Studying Mental Illness in Context: Local, Global, or Universal? Ethos. 1997;25(2):230–248. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE, Farina A, Hastorf AH, Markus H, Miller DT, Scott RA. Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships. N.Y: W.H. Freeman and Co.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Katz AM, Shotter J. Hearing the patient’s voice: toward a ‘social poetics’ in diagnostic interviews. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43:919–931. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the Clinic: The Problem of Cultural Competency and How to Fix It. PLoS Med. 2006;3(10):e294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. What Really Matters: Living a moral life amidst uncertainty and danger. N.Y.: OUP; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Moral Experience and Ethical Reflection: Can Ethnography Reconcile Them? A Quandary for ‘The New Bioethics’. Bioethics and Beyond, Dædalus. 1999;128(4):69–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Writing at the Margin: Discourse between Anthropology and Medicine. Berkeley: U.Cal. Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mishler EG, Clark J, Ingelfinger J, Simon MP. The language of attentive care: a comparison of two medical interviews. JGIM. 1989;4:326–335. doi: 10.1007/BF02597407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishler E. Validation in Inquiry Guided Research, the Role of Exemplars. Harvard Edu. Rev. 1990;60(4):415–442. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Radley A, Chamberlain K. Health Psychology and the study of the case: from method to analytic concern. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001;53:321–332. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Langenhove L, Harré R. Positioning and the Production and Use of Stereotypes. In: Harré R, van Langenhove, editors. Positioning Theory: Moral Contexts of International Action. Oxford: Blackwell; 1999. pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000;50:813–828. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B. Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007;64:1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas L, Cabassa L, Perez M. Capacity-to-Consent in Psychiatric Research: Development and Preliminary Testing of a Screening Tool. Research on Social Work Practice. 2005;15:545–556. [Google Scholar]