Abstract

This study examined the contributions of personality to the emotional and behavior dynamics of families. Analyses assessed the degrees to which personality accounts for associations between marital quality and parenting, and mediates genetic contributions to these relationships. Participants included 318 male and 544 female same-sex twin pairs from the Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden. All twins completed self-report measures of marital quality and personality (anxiousness, aggression, sociability). Composite measures of parent negativity and warmth were derived from the twins' and their adolescent children's ratings of the twins' disciplinary styles and the emotional tone of the parent-child relationship. Observational ratings of marital quality and parenting were also obtained for a subset of twins. Analyses indicated that personality characteristics explain 33% to 42% of the covariance between reported marital quality and parenting, and 26% to 28% of the covariance between observed marital quality and parenting. For both sets of analyses personality accounted for more than half of the genetic contributions to covariance between marital quality and parenting. Results indicate that personality significantly contributes to associations between marital quality and parenting, and that personality is an important path through which genetic factors contribute to family relationships.

Keywords: Marriage, Parenting, Personality, Twins

Previous studies have shown that parents' appraisals of the quality of their marriages (i.e., marital satisfaction, cohesion, or harmony) and conflict within their marriages are associated with the general affective tone of the parent-child relationship, and with parents' behaviors towards their children (Cox & Paley, 1997; Erel & Burman, 1995; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2002). These associations are strongest when parents' reports of their marriage and parenting style are used. For example, parents' reports of marital satisfaction and cohesion are significantly associated with their perceptions of how much warmth or negative affect they show their children, as well as their beliefs about how to discipline their children (Goldberg & Easterbrooks, 1984; Feldman, Wentzel, Weinberger, & Munson, 1990); Margolin, Christensen, and John (1996) have found that parent-child conflicts are contingently related to interparental conflict. Significant associations between the affective tone and quality of the marital and parent-child relationships are also present when multiple raters and observational measures are included (Erel & Burman, 1995). For example, Kitzmann (2000) found that when parents demonstrated more negativity and tension towards each other during a problem solving task, they also demonstrated more negativity and less supportive parenting in subsequent interactions with their children. More recently, Sturge-Apple and colleagues (2006) found that when parents express more hostility, aggression and withdrawal during disagreements with their partners, they also tend to be less emotionally available to their children in subsequent interactions. Taken together, these studies provide strong evidence that the emotional tone and quality of marital interactions and parent-child interactions are linked.

Family systems theory is most frequently used to explain these links (Cox & Paley, 1997). Within this framework, the family is conceptualized as a complex and organized system, composed of multiple subsystems, including the interparental relationship and the parent-child relationship. These subsystems are interdependent, which permits families to adapt to changes, but also helps families maintain stability. As a consequence, the emotional and behavioral dynamics of one subsystem affects other subsystems. Different mechanisms have been used to account for this interdependency. Some propose that heightened interparental conflict exhausts parents' emotional resources and availability, causing parents to be less responsive and harsh towards their children (e.g., Davies, Sturge-Apple, & Cummings, 2004; Fauber, Forehand, Thomas, & Weirson, 1990). Others propose that emotions aroused within one family relationship spillover into other relationships (Margolin et al., 1996). Still others hypothesize that family members imitate each other (Erel & Burman, 1995). Consequently, a child who observes affection and warmth between his parents would also exhibit these characteristics during interactions with his parents.

Although previous studies have supported family systems theory, additional and complementary processes may also be in play, and add to similarities between the emotional and behavioral dynamics of family relationships. In particular, parents' personality characteristics may help explain how positive or negative patterns of interactions first arise and are maintained within families. Within the marital and parenting research literatures, parents' characteristics are usually conceptualized as factors that strain relationships, but are not used to explain associations between family subsystems (e.g., Belsky, 1984). However, there are a few exceptions. Feldman and colleagues (1990) found that mothers' overall distress partially explained associations between marital conflict and overall family functioning. Davies et al, (2004) report that parental depression moderates associations between couples' discord and acceptance (vs. rejection) of their children. Within a recent study from the Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden (TOSS), half of the association between marital quality and parents' self reported negativity and warmth towards their children was explained by the parents' genetic makeup (Ganiban, Spotts Lichtenstein et al., 2007). Genetic factors also accounted for a significant portion of the association between observational measures of interparental warmth and parents' expression of affection and support to their children. But, due to limited statistical power, the relative contributions of genetic versus family-wide factors to associations between marital conflict and parent negativity could not be distinguished. The TOSS findings provide stronger evidence for person-based contributions to associations between marital and parent-child interactions. However, this study did not identify the behaviors through which genes affected these associations. The current study uses the TOSS data set to determine if personality characteristics account for these genetic effects. As such, this study explores the validity of a personality-based mechanism that contributes to links between different family subsystems, and examines a path through which genetic factors contribute to relationships. Understanding the impact of personality on family relationships could provide further insight into why negative or positive relationships first arise and how they are perpetuated.

Personality is defined as a set of enduring characteristics that affect behavior and perceptions. Although different theories use different nomenclature, most include the following dimensions: (1) anxiety or neuroticism, conceptualized as proneness to feel anxiety and to fear punishment; (2) sociability or extraversion, which reflects high attraction to social or environmental rewards; and (3) aggression, which describes the tendencies to feel and express anger, hostility, and irritability (for reviews see Derryberry & Rothbart, 1997; Zuckerman, 2005). Longitudinal studies indicate that there is significant rank-order stability in core personality characteristics during adulthood, and cross-age correlations between .57 to .75 have been reported (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). Behavior genetic studies consistently find that core personality dimensions are genetically influenced, and that genetic factors primarily account for personality stability (Bouchard & McGue, 2003; Gillespie, Evans, Wright & Martin, 2004; Viken, Rose, Kaprio, & Koskenvuo, 1994).

Stable personality characteristics could affect interpersonal relationships in many ways. One possibility is that individuals seek out others who have similar personalities as friends and mates. In doing so, a person creates a social niche for himself that reinforces his own personality characteristics, thereby enhancing the expression of genetically- or biologically-based predispositions. These predispositions would be reinforced further if offspring inherit the same behavioral and emotional tendencies of both parents. However, empirical evidence of assortative mating based upon personality is surprisingly weak (Luo & Klohnen, 2005), and when such effects have been detected, their impact on estimates of genetic or environmental contributions to personality are negligible (Bouchard & McGue, 2003). Therefore, other personality-based mechanisms may underlie similarities between the marital and parent-child relationships.

Personality characteristics could influence how individuals perceive relationships and guide their behaviors within different relationships (Karney, Bradbury, Fincham, & Sullivan, 1994; Rusting 1998). These possibilities are consistent with a host of personality theories that posit personality is built upon individual differences in neurological or cognitive systems that predispose individuals to selectively notice, process, and respond to environmental cues in particular ways (e.g., Cloninger, 1998; Gray, 1981; Mischel, 2004). For example, Gray (1981) and Cloninger (1998) both propose that anxiety is rooted in the sensitivity of a neurobiological system that detects punishment and threat cues and predisposes individuals to withdraw from such cues. A recent meta-analysis indicates that highly anxious individuals consistently demonstrate an attentional bias for threat related cues that is absent in nonanxious individuals (Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin et al., 2007). Anxious individuals are also more likely to perceive ambiguous feedback more negatively than other people (Vestre & Caufield, 1986), and tend to make more negative interpretations when confronted with words or sentences that have multiple meanings (Eysenck, Mogg, May, Richards, & Matthews, 1991).

Within the context of relationships, heightened anxiety may cause people to be overly attentive to signs of rejection and criticism, making them more likely to perceive relationships as punishing, and to withdraw emotionally and behaviorally from relationships. Consistent with this possibility, previous studies report associations between neuroticism, which incorporates anxiousness, and less warmth, positive affect, nurturance and responsiveness during parent-child interactions (e.g., Belsky, et al., 1995; Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000; Kochanska, Clark, & Goldman, 1997; Kochanska, Friesenborg, Lange, & Martel, 2004; Metsapelto & Pulkkinen, 2003). In regard to marital relationships, neuroticism is consistently and negatively associated with marital stability (Karney & Bradbury, 1994), and premarriage assessments of neuroticism are moderately predictive of whether or not a couple divorces (Jocklin et al., 1996; Kelly & Conley, 1987). There is also evidence that one spouse's neuroticism is negatively associated with the other spouse's marital satisfaction (Karney et al., 1995; Russell & Wells, 1994). These latter studies suggest that anxiety affects behavior within relationships.

Trait aggression and trait anger describe individuals who are prone to express aggression and anger in all situations (Bettencourt et al., 2006). Psychobiological theories propose that individual differences in the reactivity of neurological systems that control rage, anger, and aggression in response to threat underlie trait aggression (e.g., Gray, 2000). These systems appear to be genetically influenced (Zuckerman, 2005). Social cognitive research also indicates that persistent aggression is, in part, based upon stable hostile attributional biases (Coie & Dodge, 1998). It is probable that trait aggression fosters more adversarial and less nurturant relationships with others. Indeed, mothers' trait hostility is predictive of less nurturance and supportiveness, and more rejection during interactions with their children (Shaw, et al. 2001; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008). Longitudinal studies have found that anger proneness and aggression during childhood are predictive of relationship instability (Caspi et al., 1987; Kinnunen & Pulkkinenn, 2003) and with divorce during adulthood (Jocklin, et al., 1996).

Lastly, extraversion, sociability, reward dependence and agreeableness are all thought to reflect sensitivity to social rewards or rewards in one's environment. Less attention has been paid to the impact of these personality characteristics upon perceptual and attentional processes that contribute to social behaviors. However, it is likely that individuals who are motivated by social rewards would act in ways that foster and maintain social relationships. Previous studies do indicate that agreeableness is correlated with more positive affect, nurturance, and sensitivity, as well as to lower levels of detachment and fewer over-reactions during parent-child interactions when parent-reports or observational measures of parenting are used (Belsky et al., 1995; Clark et al., 2000; Kochanska et al., 2004; Metsapelto & Pulkkinen, 2003; Prinzie et al., 2004). In regard to marriage, agreeableness is associated with higher relationship quality (Blum & Mehrabian, 1999; Robins, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2002), while low agreeableness is associated with divorce (Kelly & Conley, 1987).

In summary, personality characteristics are thought to reflect individual differences in the sensitivity to various environmental cues as well as interpretation of those cues. In doing so, personality is expected to affect behavior in interpersonal situations. It is hypothesized that personality characteristics exert similar effects on different relationships and contribute to associations between different family subsystems. In the current study, we determine if adults' aggression, anxiety, and sociability account for associations between marital quality and parenting, and specifically explain genetic contributions to these associations. It is hypothesized that aggression and anxiety adversely influence the interparental and parent-child relationships and contribute to similarities in the affective tone and behaviors within both relationships. Specifically, adults who demonstrate high levels of each characteristic are expected to develop relationships with their partners and children that are characterized by higher levels of negative affect and conflict and that are less emotionally supportive and satisfying. Conversely, it is hypothesized that higher levels of sociability are associated with greater expressions of warmth and support within relationships. Thus, it is anticipated that sociability contributes to observed associations between marital and parent-child warmth.

Method

Participants

The Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden (TOSS) included 909 same-sex twin pairs who were recruited in two cohorts. Both cohorts were drawn from the Swedish Twin Registry, and were recruited within three years of each other (Lichtenstein et al., 2002). Cohort 1 was comprised of 326 female twin pairs who were born between 1926 and 1966. Cohort 2 included an additional 583 same sex male and female twin pairs born between 1944 and 1971. The same inclusion criteria were used for both cohorts: each twin had to (1) have an adolescent child who was the same gender and within 4 years of age as his/her cotwin's child, and (2) be involved in a long-term relationship with a partner who resided in the same home. These inclusion criteria were adopted to ensure that the current living experiences of each of the twin parents were comparable to those of his or her co-twin (Reiss et al., 2001; Neiderhiser & Lichtenstein, 2008). TOSS was reviewed by Institutional Review Boards in Sweden and in the United States, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study.

The current study included a subset of 862 twin pairs who completed personality, marital and parenting questionnaires. This sample consisted of 544 female twin pairs (258 Monozygotic (MZ) and 286 Dizygotic pairs (DZ)), and 318 male twin pairs (129 MZ and 189 DZ pairs). The average age of the twins was 43.6 (± 4.49) years for females, and 47.0 (±4.54) years for males. Their children ranged in age from 11 to 22 years (mean child age=15.8 ± 2.4 years), and 49% were male. The MZ and DZ twins were not significantly different in age, occupation level, education or in regard to the age of their partners. Participants were mostly middle class. Eighty-two-percent of the sample were married, and 18% were not married, but cohabitating – a common and socially acceptable practice in Sweden. For the sake of simplicity, the relationship between the twins and their spouses/partners will be referred to as the marital relationship. For TOSS, the average length of the marital relationship was 19.94 years (S.D=6.0 years) and 96% of the spouse/partners were biologically related to the adolescent child included in the study. Seventy-six-percent of the sample had not been married to another person prior to their current relationship. Amongst the remaining participants, 64% had one previous marriage, while 36% had two or more previous marriages.

Zygosity was initially assigned to the twins using self-report methods described by Nichols and Bilbro (1966). If the twins perceived themselves as similar as “two berries on a bush”, they were classified as MZ twins. If, however, the twins perceived themselves as different and indicated that others have little difficulty distinguishing between them, they were classified as DZ twins. DNA was used to confirm zygosity for 89% of the sample. Agreement between the questionnaire and DNA assignments was 96%. When disagreements were found, DNA data were used to assign zygosity. For the remaining 11% of the sample, the twins either refused to provide a DNA sample or did not provide a useable sample. Thus, their assignment was based on questionnaire data.

Procedures

All TOSS participants completed questionnaires pertaining to adjustment, mental health, personality, and family relationships (Neiderhiser & Lichtenstein, 2008). These questionnaires were administered to the twins, their spouses, and the targeted child during home visits. Cohort 1 participants were also videotaped during a 10-minute interaction with their spouse and during a separate 10-minute interaction with their children. For each interaction the interviewer selected three topics that had been identified as a source of conflict by members of the twin-spouse/partner or parent-child dyad, and asked them to discuss these topics for ten minutes. The order in which the dyads were videotaped was random.

Measures

Personality

Two well-established and widely used self-report personality measures were used to assess the twins' characteristics: the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI; Cloninger et al., 1993) and the Karolinska Scales of Personality (KSP; Schalling & Edman, 1993). The TCI was created to assess Cloninger's psychobiological model of personality (Cloninger et al., 1998). The current study included six TCI subscales. Harm avoidance (20 items, alpha=.84) describes increased sensitivity to punishment and novelty cues as well as the tendency to withdraw when such cues are present. Novelty seeking (20 items, alpha=.65) describes attraction to novelty, conditioned rewards and cues that signal relief from monotony or punishment. Reward dependence (15 items, alpha=.58) describes sensitivity to social rewards. Persistence (5 items, alpha=.55) describes the tendency to continue behaviors after rewards have been withdrawn. Cooperativeness (25 items, alpha=.69) captures individual differences in empathy and helpfulness. Self-directedness (25 items, alpha=.82) describes individuals who are goal directed and purposeful versus overwhelmed with anxiety. Five subscales from the KSP were also used to obtain more detailed assessments of the twins' anxiety and aggressiveness (Schalling & Edman, 1993). Somatic anxiety (10 items, alpha=.82) refers to the tendency to feel restless and tense. Psychic anxiety (10 items, alpha=.87) describes proneness to worry and feel panicky. Verbal aggression (5 items, alpha=.66) describes the tendency to attack others verbally. Indirect aggression (5 items, alpha=.59) relates to a person's tendency to redirect aggression to inanimate objects, while inhibited aggression (5 items, alpha=.74) describes a tendency to not express aggression outwardly.

In the interest of data reduction, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted with the TCI and KSP subscales (Ganiban, Chou, Haddad et al., in press). Common Factor analysis with an oblique rotation was used to determine how the personality scales clustered. This type of factor analysis extracts factors based upon the observed intercorrelations amongst variables. Three factors explained all of the common variance for the personality scales, with each factor explaining a minimum of 10% of the common variance. The remaining factors accounted for trivial variance, included weak factor loadings, and were not interpretable. Six personality scales loaded onto Factor 1 (i.e., loadings > .30; Tabachnick & Fidell, 1989): psychic anxiety (.92), harm avoidance (.75), somatic anxiety (.72), self-directedness (−.68), inhibited aggression (.67), and indirect aggression (.38). These scales reflect proneness to anxiety (psychic anxiety, harm avoidance, somatic anxiety, low self-directedness) and fear of punishment (inhibited and indirect aggression). Consequently, this factor was labeled “anxiety”. Three personality scales loaded onto Factor 2: verbal aggression (.53), indirect aggression (.48), and novelty seeking (.48). This pattern indicates that Factor 2 reflects a tendency towards reactive, unregulated aggression, coupled with impulsivity, and was named “aggression”. Lastly, two scales loaded onto Factor 3, cooperativeness (.60) and reward dependence (.54). Because these characteristics primarily reflect sensitivity to social rewards and acceptance, Factor 3 was labeled “sociability”. While TCI persistence subscale did not clearly load onto any of the three factors, indirect aggression loaded onto the anxiety and aggression Factors. Indirect aggression's loading on the aggression Factor was greater, suggesting that indirect aggression is more closely aligned with other indices of aggression. However, because indirect aggression describes a tendency to redirect aggression from its object towards inanimate, nonthreatening objects, this tendency could also arise when one fears the consequences of expressing aggression openly. Factor scores were generated through using the loadings for each personality scale on each Factor.

Parenting

Parenting Questionnaires

Questionnaires that assessed the emotional tone of parent-child relationships and parents' disciplinary practices were administered to the adult twins and to their adolescent children. Each of these measures has established validity and has been used with adolescent samples (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992; Reiss et al., 2000).

The Expression of Affection Inventory (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992) was used to assess children's, mothers', and fathers' expressive affection (alphas=.84 to .86) and instrumental affection (alphas = .75 to .82) to each other.

The Parent-Child Relationships Scale was also used to assess positive affect within the parent-child relationship. It includes subscales that assess closeness (alpha=.82), and conflict (alpha=.68) between the parent and the child.

The Expressed Emotion Scale (Hansson & Jarbin, 1997) was developed to assess criticism within relationships. This measure includes subscales that assess the degrees to which parents perceive criticism from their children (alpha=.68), criticize their children (alpha = .86), and view themselves as overly emotionally involved with their children (alpha=.72).

The Parent-Child Agreement scale was used to assess the amount of conflict versus consensus within the parent-child relationship. Subscales captures whether or not parents and children agree on different issues. The subscales included in this measure were: household effects (alpha=.91), behavior to others (alpha=.79), adolescent issues (alpha=.84), deviant behavior (alpha=.70), and a summary scale that measures total disagreements (alpha=.95). For the purposes on this study, only the total disagreement scale was used.

The Child Rearing Issues Scale includes specific subscales that assess parent's use of communication and reasoning (alpha=.90), punitive discipline (alpha=.86), and permissive discipline (alpha=.69) with their children.

As reported in previous papers, a second-order actor analysis was conducted with the parents' self-report measures (Ganiban et al., 2007; Neiderhiser et al., 2004, 2007). These analyses yielded two factors that reflected different patterns of affect and behavior within the parent-child relationship, and were named parent negativity and parent warmth. Subscales that assessed relational conflict, and ineffectual discipline (i.e., punitive and permissive discipline) loaded most strongly onto the negativity factor. Subscales related to affection and closeness in the parent-child relationship loaded onto the warmth factor. Factor analysis based on child reports of parenting yielded similar parent warmth and negativity factors. The parent and child factors that tapped the same affective and behavioral dimensions were significantly correlated, and ranged from .39 to .43 for male twins and their children, and between .42 to .43 for female twins and their children. Consequently, the parents' and children's ratings were combined to form multi-rater “reported parent negativity” and “reported parent warmth” composites.

Observational measures of parenting

Female twins in Cohort 1 were observed during interactions with their children. These interactions were videotaped and rated using a coding system developed by Hetherington and Clingempeel (1992). Independent coders rated each member of a twin pair, and independent coders rated mother-child and marital interactions. Fourteen five-point rating scales from the original coding scheme were used to asses the twins' behaviors as they interacted with their spouses and children: anger, warmth, coercion, assertiveness, involvement, self-disclosure, communication, authority/control, depressed mood, positive mood, problem solving, transactional conflict, sociability, and antisociability. Four additional subscales were developed for TOSS, and were coded for all family members: comprehensibility, manageability, meaningfulness, and sympathy. Interrater reliabilities were generally high (kappas ranged from .60 to .79).

Factor analysis of these scales yielded three factors that reflected the twins' expression of emotion and behaviors during problem solving interactions with their children: observed maternal negativity, observed maternal warmth, and observed maternal control (Neiderhiser et al., 2004). Observed negativity reflected the degree to which conflict and anger were present during problem solving interactions, as well as parents' of use of coercion with their children. The observed maternal warmth composite primarily reflected the expression of positive affect and responsiveness within the mother-child interaction.

Marital quality

Marital Quality Questionnaires

Self-report measures were used to assess the emotional tone of the interparental relationship and behaviors that have been associated with relationship quality and satisfaction. The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976) is frequently used to assess the relationship quality of married and unmarried couples. The DAS includes four subscales. Dyadic satisfaction (alpha=.84), dyadic consensus (alpha=.91), affectional expression (alpha=.78), and dyadic cohesion (alpha=.83).

The Expressed Emotion Scale (Hansson & Jarbin, 1997) was used to measure hostility and negative affect within the marital relationships. Subscales assess the degree to which respondents feel their partners direct critical comments to them (alpha=.79), and the degree to which they direct critical remarks towards their partners (alpha=.88). A third subscale taps emotional overinvolvement with one's partner (alpha=.72), characterized as emotional dependence and weak boundaries. In addition, one item from the Marital Instability Scale (Booth, Johnson, & Edwards, 1983) asked whether the respondent had discussed divorce or separation with a friend.

In a previous study that only included Cohort 1, factor analysis of the marital measures yielded a single factor that reflected the overall quality of the marital relationship (Spotts et al., 2005). This factor was replicated with Cohort 2 and with the total TOSS sample. Marital Satisfaction, dyadic consensus, affectional cohesion and expression loaded positively onto the marital quality factor, while marital instability, overinvolvement and criticism within the relationship loaded negatively onto this factor. Therefore, higher marital quality factor scores reflect more positive affect and dyadic cohesion, and greater satisfaction with the relationship. Lower scores related to perceptions of more criticism and instability, and dissatisfaction with the relationship.

Observed marital interactions

The twins were also observed during problem solving interactions with their partners. As described previously, these interactions were rated using the Family Interaction Coding System (Hetherington et al., 1992). The twins' behaviors were assessed with 18 five-point ratings scales: anger, warmth, coercion, assertiveness, involvement, self-disclosure, communication, authority/control, depressed mood, positive mood, problem solving, transactional conflict, sociability, antisociability, negative/positive atmosphere, disgust/contempt, defensiveness, and withdrawal. The interrater reliabilities for these scales were high (kappas .60 – .79). Factor analysis was used to create composite scores. This analysis yielded three factors: marital conflict, warmth, and control. The observed marital conflict factor related to the degree to which the women demonstrated anger or coercion towards their spouses versus affection and positive affect during the problem solving tasks. Because the current study focused upon similarities in the emotional tone and behavior across family relationships, only marital conflict and warmth were included in this study. The observed marital warmth factor reflected the extent to which the women communicated with and demonstrated warmth and positive affect towards their spouse versus being withdrawn during the problem solving tasks.

Data Analysis

Preliminary Analyses

All participants in TOSS were recruited through the Swedish Twin Registry. However, because participants were collected as two cohorts, we systematically examined the TOSS dataset for cohort effects prior to combining them for analysis. For the vast majority of the measures examined in TOSS (89%) there were no significant and meaningful differences between the cohorts. Nevertheless, for most parenting scales, cohort 2's values were slightly lower than cohort 1's values (differences were < 1 on multi-item scales). Yet, associations between the parenting variables and other variables of interest to the current study (i.e., personality, marital quality), and the results of factor analyses that included the parenting scales were identical for both cohorts. Therefore, because the current study focuses on covariance between variables, these slight cohort differences should not affect data analyses.

In addition, we examined correlations between the key study variables and a number of potential confounding factors, including: twin's age, child's age, current contact between twins, spouse age, and child gender. Child's age was significantly correlated with reported parent warmth (r=−.42) and negativity (r=−.10). The twin's age was correlated with aggression (r=−.12), reported parent warmth (r=−.14), and observed parent negativity (r=−.13). Lastly, current contact between cotwins was associated with reported parent warmth (r=.11). Therefore, prior to model-fitting the effects of child's age, twin's age, and current contact were residualized from reported parent warmth. Child's age was residualized from reported parent negativity. The effect of twin's age was also residualized from aggression and observed negativity. Lastly, to correct for skew, the data were ranked ordered and normalized (Eaves et al., 1997). After these transformations were performed, correlations amongst variables were computed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Means (X), Standard Deviations (SD) and correlations between study variables

| Self–Report Measuresa | Parent-Child Report Composites\a | Observational Measuresb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| X | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Self-Report a | |||||||||||

| 1. Aggression | .00 | .78 | -- | ||||||||

| 2. Anxiety | .00 | .95 | .02+ | -- | |||||||

| 3. Sociability | .00 | .75 | −.47 | −.09 | -- | ||||||

| 4. Marital Quality | .00 | 1.0 | −.22 | −.38 | .20 | -- | |||||

| Parent-Child Report a | |||||||||||

| 5. Parent Negativity | −.07 | 1.69 | .20 | .30 | −.09 | −.35 | -- | ||||

| 6. Parent Warmth | −.02 | 1.65 | .04+ | −.11 | .15 | −.17 | −.07 | -- | |||

| Observational Measures b | |||||||||||

| 7. Marital conflict | .00 | 1.0 | .22 | .07+ | −.21 | −.36 | .15 | −.04+ | -- | ||

| 8. Marital warmth | .00 | 1.0 | −.02+ | −.13 | .21 | .23 | −.05+ | .10 | −.39 | -- | |

| 9. Parent negativity | .00 | 1.0 | .17 | .04+ | −.19 | −.10 | .33 | −.04+ | .34 | −.20 | -- |

| 10 Parent warmth | .00 | 1.0 | .06+ | −.11 | .20 | 0 | .03+ | .07+ | −.08+ | .45 | −.24 |

p>.05

Self-report and parent-child report measures include the entire TOSS sample (N=1818)

Observational measures only include a subset of female twins from TOSS (N=652)

Biometric Model Fitting

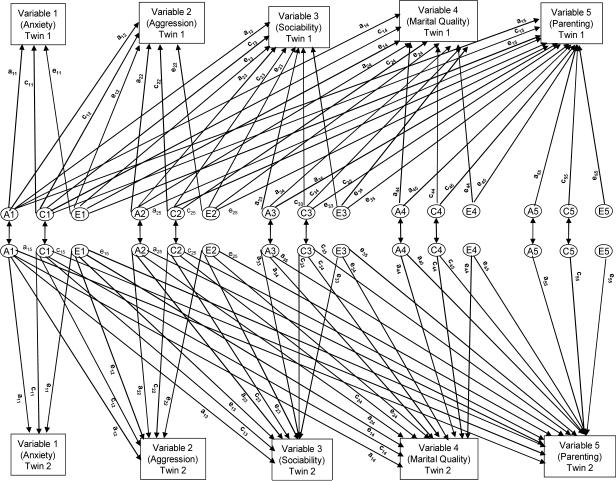

Multivariate biometric model fitting was used to assess how much genetic and environmental factors associated with the twins' personality characteristics (anxiety, aggression, sociability) account for associations between marital quality and parenting. The general biometric model used for these analyses is depicted in Figure 1. This model includes five manifest variables for each twin: three personality variables (variables 1, 2 and 3), a marital quality variable (variable 4) and a parenting variable (variable 5). However, as noted in the results section, in several instances only two personality characteristics were simultaneously correlated with the marital quality or the parenting dimensions of interest. When this occurred the biometric model included just four variables.

Figure 1.

Multivariate Biometric Model. This model includes latent genetic (A1,A2,A3. A4,A5), shared environmental (C1,C2,C3,C4, C5) and nonshared environmental factors (E1,E2, E3, E4, E5). The paths between latent factors A1, A2, and A3 for twins 1 and 2 were set to 1.0 for MZ twins, and 0.50 for DZ twins. The paths between latent C1, C2, and C3 for twins 1 and 2 were set to 1.0 because these latent factors represent experiences that the twins have in common. The path estimates were constrained to be equal for Twin 1 and Twin 2.

As depicted in Figure 1, the variance of each variable is partitioned into latent genetic (A1, A2, A3, A4, A5), shared environmental (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5) and nonshared environmental (E1, E2, E3, E4, E5) components. The latent genetic factors encompass all additive genetic contributions to variance in the manifest variables. The double headed arrows between the latent genetic factors for twin 1 and twin 2 describe the genetic relatedness of the twin pair. These paths were set to 1.0 for MZ twins because they have the same genotype, and to .50 for DZ twins who on average share 50% of the same co-segregating genes. Shared environmental factors refer to experiences that make cotwins similar to each other. Accordingly, paths between latent shared environmental factors for twins 1 and 2 were set to 1.0. Experiences shared by twins during childhood as well as current contact may contribute to shared environment. Nonshared environmental factors represent experiences that make cotwins different from each other. Measurement error is also captured by this latent factor.

Within this model, latent genetic and environmental factors account for variance for each manifest variable, as well as associations between variables. For each twin, the first three variables in Figure 1 are personality characteristics, followed by ratings of their marital quality and parenting. Consequently, latent factors A1,A2, A3 correspond to genetic factors associated with all three personality characteristics, while latent factors C1, C2, C3, and E1, E3, and E3 are environmental factors that account for variance in personality. The degree to which all three personality characteristics mediate the association between marital quality (variable 4) and parenting (variable 5) can be estimated by computing the extent to which this association occurs through latent factors associated with personality. i.e., rmed=(a14 × a15) + (a24 × a25) + (a34 × a35) + (c14 × c15) + (c24 × c25) + (c34 × c35) + (e14 × e15) + (e24 × e25) + (e34 × e35). The specific contributions of personality-related genetic factors (A1, A2, A3) to associations between marital quality and parenting is computed as amed=(a14 × a15) + (a24 × a25) + (a34 × a35). The relative contributions of latent shared environmental (C1,C2, C3) and nonshared environmental (E1,E2, E3) factors to rmed are estimated in a similar manner. The residual association between marital quality and parenting can also be computed by multiplying and adding paths that link marital quality and parenting, but are independent from personality, i.e., rres= (a44 × a45) + (c44 × c45) + (e44 × e45). The specific contributions of genetic factors to rres are calculated as: ares= a44 × a45. The total correlation between marital quality and parenting is computed as rtot= rmed + rres. Lastly, latent factors A5, C5, and E5 are genetic and environmental factors associated with parenting, but independent of the twins' personality characteristics and perceived marital quality.

Variance-covariance matrices were used in model fitting with the Mx statistical package (Neale, 2003). The fits of several models were tested using maximum likelihood estimation. First, a model in which parameter estimates were permitted to vary for male and female twins was fit (unconstrained ACE model). A second model that constrained parameter estimates to be equal for males and females (constrained ACE model) was also fit to test for gender effects. Lastly, because shared environmental contributions to adult personality are rare (Bouchard & McGue, 2003), a third model that excluded latent shared environmental factors was fit (AE model). The fit of the unconstrained ACE model was assessed via χ2, the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). When the χ2 is nonsignificant the model accurately represents the data. However, χ2 values are likely to reject a model that fits the data well, but imperfectly, are highly sensitive to sample size, and are more likely to favor saturated models (Mulaik et al., 1989; Neale & Cardon, 1992). Commonly advocated alternatives are the RMSEA and the AIC (Tanaka, 1993). RMSEA values less than .08 are generally considered to represent a good model fit. A negative or very low AIC is indicative of a parsimonious model. Because the constrained ACE and AE models are nested within the unconstrained ACE model, the fits of these models relative to the unconstrained ACE model are evaluated through the likelihood ratio test (LRT). The LRT assesses whether the nested models represent a significantly worse fit to the data than the unconstrained ACE model through evaluating differences in the models' χ2 values (Δχ2) in relation to differences in their degrees of freedom (Δdf).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 summarizes the means, standard deviations, and correlations between the twins' personality characteristics, marital quality and parenting. Because the correlations for male and female twins were nearly identical, the top of Table 1 includes correlations for the entire sample. The bottom of Table 1 includes correlations between observational measures and report measures for the Cohort 1 female twins. For this subsample, observed and reported parent negativity were significantly correlated, and reported marital quality was correlated with observed marital conflict and warmth. Observed parent warmth was marginally correlated with the reported parent warmth composite.

The twins' perceptions of their marital quality was positively correlated with the reported parent warmth composite and negatively correlated with the reported parent negativity composite. Aggression, anxiety and sociability were all significantly associated with marital quality and the reported parent negativity composite. However, only anxiety and sociability were significantly correlated with the reported parent warmth composite. For the female twins who were observed during interactions with their spouses and their children, sociability and aggression were significantly associated with observed marital conflict and parent negativity. Sociability and anxiety were related to observed marital warmth and parent warmth.

Multivariate biometric analyses

Reported Marital Quality and Parent Negativity

Because anxiety, aggression, and sociability were significantly correlated with marital quality and the reported parent negativity composite, their collective contributions to associations between these variables were assessed. The unconstrained ACE model fit the data well (χ2 (130)=192.05, p<.05; AIC=−67.95; RMSEA=.04). Constraining the estimates to be equivalent for males and females did not worsen the fit of the model (ΔDF=45, Δχ2 =46.38, n.s.). Lastly, the fit of the constrained AE model did not significantly differ from the unconstrained ACE model (ΔDF=60, Δχ2 =47.92, n.s.). The parameter estimates for the constrained AE model are included at the top of Table 2, and were used to compute rtot, rmed and rres (see Table 3). A little less than half of the association between marital quality and the reported parent negativity composite was related to the twins' personality (rmed/rtot=.42). However, personality explained more than half of the total contribution of genetic factors to rtot, i.e., amed/(amed + ares)=.57. The residual association between marital quality and the reported parent negativity composite was rres=.21, and was primarily explained by nonshared environmental factors (eres/rres=.71). Genetic factors unrelated to personality also contributed to residual covariance (ares/rres=.28).

Table 2.

Estimated paths from latent genetic (A) and nonshared environmental (E) factors to twins' personal characteristics, marital quality and parent negativity and warmth

| Personality, Marital Quality and Parent Negativity |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable 1: Anxiety | Variable 2: Aggression | Variable 3: Sociability | Variable 4: Marital Quality | Variable 5: Parent Negativity | ||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Latent Factor | Path | Estimate (CI) | Path | Estimate (CI) | Path | Estimate (CI) | Path | Estimate (CI) | Path | Estimate (CI) |

| A1 | a11 | .71 (.66,.76) | a12 | −.01 (−.01,.08) | a13 | .16 (.07, .24) | a14 | .27 (.19, .35) | a15 | .18 (.09, .26) |

| E1 | e11 | .70 (.66,.75) | e12 | .01 (−.06,.07) | e13 | .08 (.02, .15) | e14 | .25 (.18, .32) | e15 | .20 (.14, .27) |

| A2 | a22 | .71 (.66, .76) | a23 | .35 (.27, .42) | a24 | .14 (.06, .21) | a25 | .20 (.12, .28) | ||

| E2 | e22 | .70 (.65, .75) | e23 | .35 (.29, .41) | e24 | .17 (.10, .24) | e25 | .06 (−.01, .12) | ||

| A3 | a33 | .59 (.53, .63) | a34 | −.01 (.09, .07) | a35 | −.10 (−.18, −.01) | ||||

| E3 | e33 | .62 (.58, .66) | e34 | .09 (.03, .16) | e35 | .06 (−.01, .13) | ||||

| A4 | a44 | .46 (.37, .52) | a45 | .13 (.01, .24) | ||||||

| E4 | e44 | .78 (.73, .82) | e45 | .19 (.13, .25) | ||||||

| A5 | a55 | .52 (.45, .58) | ||||||||

| E5 | e55 | .74 (.69, .78) | ||||||||

| Personality, Marital Quality and Parent Warmth |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable 1: Anxiety | Variable 2: Sociability | Variable 3: Marital Quality | Variable 4: Parent Warmth | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Latent Factor | Path | Estimate (CI) | Path | Estimate (CI) | Path | Estimate (CI) | Path | Estimate (CI) |

| A1 | a11 | .71 (.66,.76) | a12 | .16 (.07, .24) | a13 | .28 (.19, .36) | a14 | .09 (0,.17) |

| E1 | e11 | .70 (.66, .76) | e12 | .08 (.02, .15) | e13 | .25 (.18, .32) | e14 | .12 (.05, .19) |

| A2 | a22 | .68 (.63, .73) | a23 | .06 (−.02, .14) | a24 | .17 (.08, .25) | ||

| E2 | e22 | .71 (.66, .76) | e23 | .16 (.10, .23) | e24 | .00 (−.08, .06) | ||

| A3 | a33 | −.47 (−.54, −.39) | a34 | −.01 (−.18, .06) | ||||

| E3 | e33 | .78 (.74, .83) | e34 | .11 (.04, .18) | ||||

| A4 | a44 | .55 (.47, .61) | ||||||

| E4 | e44 | .80 (.75, .84) | ||||||

Legend: Latent factors and paths correspond to Figure 1. The biometric model for marital quality and parent negativity included five variables in the following order: (1) anxiety, (2) aggression, (3) sociability, (4) marital quality, and (5) parent negativity. The biometric model for associations between marital quality and parent warmth included four variables in the following order: (1) anxiety, (2) sociability, (3) marital quality, (4) parent warmth. Each path name has three components: a lower case letter, followed by two subscripted numbers. The lower case letter and first subscripted number refer to a specific latent genetic (a), shared environmental (c), or nonshared environmental (e) factor. The second subscripted number refers to the specific manifest variable (identified by its order in the model) that is linked to the latent factor via the path. For example, path a12 links latent factor A1 to the second variable in the model; CI=95% Confidence Intervals. Shared environmental estimates are not included in this table because the best-fitting models did not include latent shared environmental effects.

Table 3.

Contributions of parents' personality to covariance between reported marital quality and parents' negativity and warmth.

| Covariance between reported marital conflict and parent negativity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Portion of covariance explained by latent genetic and nonshared environmental factors related to personality | Portion of covariance independent of personality | Total Covariance | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| amed | emed | rmed | ares | eres | rres | rtot | |

| Personality characteristics: anxiety, aggression, sociability | .08 | .07 | .15 | .06 | .15 | .21 | .36 |

| Covariance between reported marital warmth and parent warmth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Portion of covariance explained by latent genetic and nonshared environmental factors related to personality | Portion of covariance independent of personality | Total Covariance | |||||

|

| |||||||

| amed | emed | rmed | amed | emed | rmed | amed | |

| Personality characteristics: anxiety, sociability | .03 | .03 | .06 | .03 | .09 | .12 | .18 |

Legend: “rtot”denotes the total association between marital quality and parenting, while “rmed” describes the portion of this association that is explained by the twins' personality characteristics. Similarly “amed” and “emed” respectively describe the portion of rmed that is explained by genetic and nonshared environmental factors. “rres” is the portion of the association between marital quality and parenting that is independent of the twins' personal characteristics. “ares” and “eres” respectively describe genetic and environment contributions to rres.

Reported Marital Quality and Parent Warmth

Because aggression did not significantly correlate with the report parent warmth composite, this biometric model included four variables in the following order: (1) anxiety, (2) sociability, (3) marital quality and (4) reported parent warmth. The unconstrained ACE model fit the data well (χ2 (84)=135.79, p<.05; AIC=−31.21; RMSEA=.06). Constraining estimates to be equivalent for males and females did not worsen the fit of the model (ΔDF=30, Δχ2 =23.60, n.s.), nor did eliminating shared environmental effects from the constrained model (ΔDF=40, Δχ2 =30.89, n.s.). The parameter estimates for the constrained AE model are included at the bottom of Table 2, and rtot, rmed, and rres for this model are summarized in Table 3. Anxiety and sociability collectively accounted for one-third of the association between marital quality and the reported parent warmth composite, rmed/rtot=.33. Personality explained half of the contributions of genetic factors to rtot, i.e., amed/(amed + ares)=.50. The residual association between marital quality and the reported parent warmth composite was primarily explained by nonshared environmental factors (eres/rres=.75). However, genetic factors unrelated to personality also contributed to rres.

Observed Marital Conflict and Maternal Negativity

This biometric model included sociability and aggression because they were significantly correlated with both observed marital conflict and observed parent negativity. The order of variables in this model was: (1) sociability, (2) aggression, (3) marital conflict, and (4) maternal negativity. The ACE model represented an adequate fit to the data (χ2 (42)=65.32, p<.05; AIC=−18.68; RMSEA=.06). Elimination of shared environmental effects did not adversely affect model fit (ΔDF=10, Δχ2 =5.59, n.s.). Consequently, the AE model was again selected for further analysis and its path estimates are presented in Table 4. As summarized in Table 5, sociability and aggression accounted for a quarter of the association between marital conflict and maternal negativity (rmed/rtot = .26). Personality factors accounted for more than half of genetic contributions to rtot, i.e. amed/(amed + ares)=.60. Nonshared environmental factors primarily explained residual covariance, i.e. eres/rres = .76. But genetic factors unrelated to personality also contributed to residual covariance, ares/rres=.24.

Table 4.

Estimated paths from latent genetic (A) and nonshared environmental (E) factors to twins' personal characteristics, observational measures of marital interactions and parent-child interactions

| Association between Marital Conflict and Parent Negativity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable 1: Sociability | Variable 2: Aggression | Variable 3: Marital Conflict | Variable 4: Parent Negativity | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Latent Factor | Path | Estimate | Path | Estimate | Path | Estimate | Path | Estimate |

| A1 | a11 | .70 (.61, .77) | a12 | .34 (.20, .46) | a13 | .26 (.13, .39) | a14 | .26 (.12, .39) |

| E1 | e11 | 72 (.64, .79) | e12 | .36 (.26,.46) | e13 | .03 (−.09, .15) | e14 | .02 (−.10, .14) |

| A2 | a22 | ..61 (.53, .68) | a23 | .18 (.05, .31) | a24 | .14 (.00, .28) | ||

| E2 | e22 | .62 (.55, .69) | e23 | .01 (−.11, .13) | e24 | −.03 (−.15, .10) | ||

| A3 | a33 | .15 (−.35, .35) | a34 | .39 (−.54, .54) | ||||

| E3 | e33 | .93 (.88, .97) | e34 | .20 (.10, .31) | ||||

| A4 | a44 | 0 (−.44, .44) | ||||||

| E4 | e44 | .85 (.78, .92) | ||||||

| Personality Marital Warmth and Parent Warmth |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable 1: Sociability | Variable 2: Anxiety | Variable 3: Marital Warmth | Variable 4: Parent Warmth | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Latent Factor | Path | Estimate | Path | Estimate | Path | Estimate | Path | Estimate |

| A1 | a11 | .70 (.61,.77) | a12 | .23 (.09, .36) | a13 | .36 (.22, .49) | a14 | .25 (.11,.30) |

| E1 | e11 | .72 (.64, .79) | e12 | .06 (−.04, .16) | e13 | −.06 (−.18, .06) | e14 | .05 (−.08, .17) |

| A2 | a22 | .68 (.58, .75) | a23 | −.10 (.26, .05) | a24 | −.12 (−.27, .02) | ||

| E2 | e22 | .69 (.62, .77) | e23 | .16 (.04, .25) | e24 | .18 (.05, .30) | ||

| A3 | a33 | .25 (−.46, −.46) | a34 | .03 (−.51, .51) | ||||

| E3 | e33 | .88 (.80, .95) | e34 | .36 (.26, .47) | ||||

| A4 | a44 | .38 (−.51,.51) | ||||||

| E4 | e44 | .78 (.71, .86) | ||||||

Legend: Latent factors and paths correspond to Figure 1. The biometric model for observed marital conflict and parent negativity included four variables in the following order: (1) sociability, (2) aggression, (3) marital quality, and (4) parent negativity. The biometric model for associations between observed marital warmth and parent warmth included four variables in the following order: (1) sociability, (2) anxiety, (3) marital warmth, and (4) parent warmth. Each path name has three components: a lower case letter, followed by two subscripted numbers. The lower case letter and first subscripted number refer to a specific latent genetic (a), shared environmental (c), or nonshared environmental (e) factor. The second subscripted number refers to the specific manifest variable (identified by its order in the model) that is linked to the latent factor via the path. For example, path a12 links latent factor A1 to the second variable in the model; CI=95% Confidence Intervals. Shared environmental estimates are not included in this table because the best-fitting models did not include latent shared environmental effects.

Table 5.

Contributions of parents' personality to covariance between observed marital quality and parents' negativity and warmth.

| Covariance between observed marital conflict and parent negativity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Portion of covariance explained by latent genetic and nonshared environmental factors related to personality | Portion of covariance independent of personality | Total Covariance | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| amed | emed | rmed | ares | eres | rres | rtot | |

| Personality characteristics: sociability, aggression | .09 | .00 | .09 | .06 | .19 | .25 | .34 |

| Covariance between observed marital warmth and parent warmth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Portion of covariance explained by latent genetic and nonshared environmental factors related to personality | Portion of covariance independent of personality | Total Covariance | |||||

|

| |||||||

| amed | emed | rmed | amed | emed | rmed | amed | |

| Personality characteristics: sociability, anxiety | .10 | .03 | .13 | .01 | .32 | .33 | .46 |

Legend: “rtot”denotes the total association between marital quality and parenting, while “rmed” describes the portion of this association that is explained by the twins' personality characteristics. Similarly “amed” and “emed” respectively describe the portion of rmed that is explained by genetic and nonshared environmental factors. “rres” is the portion of the association between marital quality and parenting that is independent of the twins' personal characteristics. “ares” and “eres” respectively describe genetic and environment contributions to rres.

Observed marital warmth and maternal warmth

Because sociability and anxiety were significantly correlated with observed marital warmth and observed maternal warmth, they were included in the biometric model in the following order: (1) sociability, (2) anxiety, (3) observed marital warmth, and (4) observed maternal warmth. The ACE model fit the data well (χ2 (42)=54.54, p>.05; AIC=−29.46; RMSEA=.04), and elimination of shared environmental factors from the model did not worsen its fit significantly (ΔDF=10, Δχ2 =.38, n.s.). The parameter estimates for the AE model are included in Table 4. As summarized in Table 5, sociability and anxiety accounted for one-quarter of the association between observed marital and maternal warmth, i.e. rmed/rtot=.28. These personality characteristics explained most of the contributions of genetic factors to rtot, amed/(amed + ares)=.91. The residual association between observed marital and maternal warmth was almost entirely explained by nonshared environmental factors, eres/rres=.97.

Discussion

Family Systems theory proposes that family subsystems are interdependent, and that the emotional and behavioral dynamics of one subsystem affects the functioning of other subsystems (Cox & Paley, 1997). This model implies a causal link between the emotional and relational dynamics of family subsystems. However, it is also possible that similarities between family subsystems are explained by the stable personality characteristics of individual family members and not by the spillover of emotions and behaviors across subsystems. The current study explored this possibility.

Analyses based upon twins' reports of marital quality and twins' and children's reports of parenting indicate that twins who describe their marriages as satisfying and supportive also tend to have relationships with their children that are affectionate and supportive. Conversely, when twins perceive more criticism and less support in their marriages, they tend to be more punitive and permissive with their children. Similar patterns of associations were present amongst observational measures of marital quality and parenting. More conflict during marital interactions was associated with more harshness and negative affect during parent-child interactions; more warmth during marital interactions was associated with more warmth during parent-child interactions.

As hypothesized, the twins' personality characteristics were correlated with marital quality and the emotional qualities of the parent-child relationship. Specifically, the twins' anxiety and aggression were associated with less marital satisfaction and more conflict during marital interactions, and with higher twin- and child-based reports of parent negativity, and observed negativity during parent-child interactions. In contrast, the twins' anxiety and aggression were inversely related to marital satisfaction, and observed and reported parental warmth. Sociability demonstrated the opposite pattern of correlations: it was positively associated with observed and reported marital warmth and parent warmth, but negatively associated with observed and reported marital conflict and parent negativity. These findings are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Robins et al., 2002; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008), and suggest that aggression and anxiety are related to more problematic relationships, while sociability is related to higher quality relationships. Further analyses examined whether personality could account for associations between marital quality and parenting.

Collectively, the twins' personality characteristics accounted for 33% to 42% of covariance between the marital and parent-child relationships when twins reported on their own marriages and twin- and child-reports of parenting were used. The twins' personality characteristics explained a smaller (26% to 28%), but significant portion of the covariance between marital quality and parenting when observational measures were used. One possible interpretation of these findings is that family relationships shape personality. However, additional analyses indicated that personality is genetically influenced and is a significant path through which adults' genetic makeup contributes to marital quality and parenting. Specifically, the twins' personality characteristics explained a substantial portion of the genetic contributions to associations between marital quality and parental warmth and negativity. When analyses were based upon the twins' appraisals of their marriage and parenting composites that included child and twin reports of parenting, personality explained about half (50% to 57%) of the genetic contributions to covariance. When observational measures were used, the twins' personality characteristics accounted for most (60% to 91%) of the genetic contributions to covariance between marital quality and the parent-child relationship. These results provide the strongest evidence for person-based contributions to family relationships and to similarities across family subsystems.

Although this study did not assess the specific mechanisms through which personality may affect relationships, it is plausible that genetically-influenced personality characteristics contribute to stable perceptual biases or behavioral predispositions that affect one's responses and behaviors in all relationships, regardless of partner. Strong tendencies towards anxiety or aggression could influence perceptions of rejection and threat within relationships (e.g., Gray, 1981), and affect how relational experiences are perceived, interpreted, and recalled (Forgas, 1995; Rusting, 1998). For example, anxiousness is associated with greater sensitivity to negative versus positive feedback, and difficulties shifting attention away from negative information (Derryberry & Reed, 1994; 2002). Anxious individuals are also more likely to perceive ambiguous feedback more negatively than other people (Eysenck et al., 1991;Vestre & Caufield, 1986). These perceptual biases could also be translated into responses to other people. Karney and colleagues (1995) found that one spouse's negative affectivity (anxiousness, depression) is significantly associated with the other spouse's marital satisfaction. High levels of aggressiveness has been associated with the tendency to form hostile attributions in ambiguous social situations, which, in turn influences the selection and enactment of behavior during interactions (Coie & Dodge, 1998). Collectively, these studies strongly suggest that personality can affect perceptions and responses within relationships. In doing so, stable personality characteristics could underlie similarities in one's relationships with different family members.

The current findings extend those of the Nonshared Environment and Adolescent Development (NEAD) project (Reiss, Neiderhiser, Plomin, & Hetherington, 2000). In contrast to TOSS, NEAD examined the contributions of children's experiences and genes to family relationships. In the NEAD sample, associations between two family subsystems (sibling relationships and the mother-child relationships), were primarily explained by family-wide experiences (i.e., shared environmental factors; Bussell et al., 1999). Given the findings of the current study, it is plausible that parents' genetically influenced characteristics contributed to their families' overall emotional climate and, in part, account for the shared environmental contributions to covariance between sibling and parent-child relationships.

The results of this study affirm the contributions of individuals to the emotional climates of families. But they do not undermine the validity of Family Systems theory. Although we have emphasized the contributions of the twins' personality to similarities between family relationships, it is important to note that associations between marital quality and parenting were not entirely explained by personality, nor by genetic factors related to personality. The twin's unique experiences (i.e., nonshared environment) primarily explained covariance between marital quality and parenting, and even partially explained personality's contributions to this covariance. It is likely that the twins' nonshared environments encompass the unique emotional climate of each twin's family that has been created and maintained by family subsystems (i.e., Cox & Paley, 1997). Therefore, person-based genetic mechanisms may act in concert with family-based mechanisms to forge and maintain links between family subsystems over time.

Many studies have examined associations between marriage and parenting, but assumed a causal link between these family subsystems. Previous studies have rarely focused on the contributions of personality to this covariance. The results of this study indicate that the personalities of individual family members do contribute to similarities in the emotional tone and behaviors within different family subsystems. Because personality characteristics are moderately stable, they may also explain how the emotional tone of a family was initially established, and play an important role in sustaining it over time. Our findings suggest that relationships do not start as blank slates; adults bring a unique set of behavioral and emotional tendencies that contribute to the emotional tone and quality of individual relationships, and partially explain similarities across family relationships.

The current study also carries implications for interventions with troubled families. The origins of troubled families may reside in the stable personality characteristics of individual family members. Because personality characteristics demonstrate moderate stability, they may also maintain family problems, and make long term changes difficult to achieve. Therefore, incorporating personality into intervention plans could strengthen the foundation for long term changes in family functioning. Family-based interventions could be tailored to address and regulate the expression of personality and attendant perceptual biases or behavioral tendencies that adversely affect family relationships. For example, when family members are highly anxious, interventions may need to focus on establishing family cohesion and stability to alleviate cues of punishment and threat. Once this foundation is set, anxious family members may be more likely to respond sensitively to others and be more receptive to long term changes in the family. A family that includes aggressive members may require a different approach. Work with such families may initially require individual therapy with aggressive members focused on reducing or controlling aggressive behavior before family-wide efforts to establish support and cohesion can be undertaken.

This study had some limitations and raises questions for further investigation. One limitation was that only a subsample of female twins was observed during interactions with their partners and children. Consequently, analyses that included observational data could not test for gender effects, and the smaller sample size yielded estimates with very large confidence intervals. In addition, while the overall patterns of findings were similar for questionnaires and observational data, the contributions of personality to associations between marital quality and parenting tended to be smaller when observational data were used. Most likely, this is due to the demands of the different assessment methods. Self-report ratings are susceptible to biased reporting, and this bias may explain the stronger associations between personality, parenting and marital quality measures that included the twins' reports. On the other hand, observational measures may be more susceptible to contextual influences, and underestimate the contributions of genetic factors or personality to relationships. Because structured observations provide a snapshot of what a relationship is like on a particular day and under unusual circumstances, they may not always capture stable patterns, or the complexities and emotional subtleties of long standing relationships. Therefore, both methods provide different, but complementary information about family relationships. Yet, despite these differences, it is important to note that both methods yielded similar results: personality accounted for significant covariance between marital quality and parenting, and partly explained the path through which genetic factors contribute to relationships.

Lastly, it should also be kept in mind that the family as a whole creates the context in which personality is expressed. For example, a person who is predisposed to anxiety may not show anxiety or even feel anxious if she (or he) is in a stable, predictable, and secure environment that poses few threats. Current theories emphasize the importance of context in stimulating the expression of temperament and/or personality characteristics and for explaining cross-situational stability in these characteristics (e.g., Mischel, 2005; Rothbart et al., 2001). Consistent with this possibility, a recent study has found that genetic contributions to emotional stability are greater when there is more family conflict (Jang et al., 2005). Therefore, genetic contributions to covariance between marital quality and parenting, or the contributions of personality to covariance may be enhanced in families with higher levels of overall conflict or stress.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/fam

References

- Bar-Haim, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakersman-Kranenbrug & van IJzendoorn MG. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Woodworth S. Personality and parenting: exploring the mediating role of transient mood and daily hassles. Journal of Personality. 1995;63:905–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt BA, Talley A, Benjamin AJ, Valentine J. Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral conditions: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:751–777. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum JS, Mehrabian A. Personality and temperament correlates of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:93–125. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Johnson D, Edwards JN. Measuring marital instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard TJ, McGue M. Genetic and environmental influences on human psychological differences. Journal of Neurobiology. 2003;54:4–45. doi: 10.1002/neu.10160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussell DA, Neiderhiser JM, Pike A, Plomin R, Simmens S, Howe GW, Hetherington EM. Adolescents' relationships to siblings and mothers: a multivariate genetic analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1248–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A. Personality in the life course. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53(6):1203–1213. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of Child Psychology, Volume 3: Social, emotional, and personality development. Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 1998. pp. 779–862. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. The genetics and psychobiology of the Seven-Factor Model of Personality. In: Silk KR, editor. Biology of Personality Disorders. American Psychiatric Press, inc.; Washington, DC: 1998. pp. 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997:243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Kochanska G, Ready R. Mothers' personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cummings EM. Interdependencies among interparental discord and parenting practices: the role of adult vulnerability and relationship perturbations. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:773–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed M. Temperament and attention: orienting toward and away from positive and negative signals. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1994;66:1128–39. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.6.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed MA. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:225–36. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Rothbart M. Reactive and effortful processes in the organization of temperament. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:633–652. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Silberg JL, Meyer JM, Maes HH, Simonoff E, Pickles A, et al. Genetics and developmental psychopathology: 2. The main effects of genes and environment on behavioral problems in the Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behavioral Development. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology and Allied Disciplines. 1997;38(8):965–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent–child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck MW, Mogg K, May J, Richards A, Mathews A. Bias in interpretation of ambiguous sentences related to threat in anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:144–150. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauber R, Forehand R, Thomas A, Wierson M. A meditational model of the impact of marital conflict on adolescent adjustment in intact and divorced families: the role of disrupted parenting. Child Development. 1990;61:1112–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SS, Wentzel KR, Weinberger DA, Munson JA. Marital satisfaction of parents of preadolescent boys and its relationship to family and child functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 1990;4:213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ganiban JM, Chou C, Haddad SK, Lichtenstein P, Reiss D, Spotts EL, Neiderhiser JM. Using behavior genetics methods to understand the structure of personality. European Journal of Developmental Science. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ganiban JM, Spotts EL, Lichtenstein P, Khera G, Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM. Can genetic factors explain the spillover of warmth and negativity across family relationships? Twin Research. 2007;10:299–313. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie NA, Evans DE, Wright MM, Martin NG. Genetic simplex modeling of Eysenck's Dimensions of Personality in a sample of young Australian Twins. Twin Research. 2004;6:637–648. doi: 10.1375/1369052042663814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg WA, Easterbrooks MA. Role of marital quality in toddler development. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. A critique of Eysenck's theory of personality. In: Eysenck HJ, editor. A Model for Personality. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1981. pp. 246–276. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, McNaughton N. The Neuropsychology of anxiety. 2nd Edition Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson K, Jarbin G. A new self-rating questionnaire in Swedish for measuring expressed emotion. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;5:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel GW. Coping with marital transitions: a family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3):1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Jang KL, Dick DM, Wolf H, Livesley WJ, Paris J. Psychosocial adversity and emotional instability: an application of gene-environment interaction models. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19:359–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jocklin V, McGue M, Lykken DT. Personality and divorce: A genetic analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:288–299. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN, Fincham FD, Sullivan KT. The role of negative affectivity in the association between attributions and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;46:413–424. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: a review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Conley JJ. Personality and compatibility: A prospective analysis of marital stability and marital dissatisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:27–40. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Sham PC, MacLean CJ. The determinants of parenting: an epidemiological, multi-informant, retrospective study. Psychological Medicine. 1997:549–563. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiztmann K. Effects of marital conflict on subsequent triadic family interactions and parenting. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:3–13. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen U, Pulkkinen L. Childhood Socio-Emotional Characteristics as Antecedents of Marital Stability and Quality. European Psychologist. 2003;8:223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Clark LA, Goldman MS. Implications of mothers' personality for their parenting and their young children's developmental outcomes. Journal of Personality. 1997;65:389–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Friesenborg AE, Lange LA, Martel MM. Parents' personality and infants' temperament as contributors to their emerging relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:744–759. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: a meta-analytic review. Family Relations. 2000;49:25–44. [Google Scholar]