Abstract

Aim of the study

This study aimed to evaluate 8-OHdG and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1α) levels in patients with hypoactive thyroid nodules (toxic multi-nodular goiter, Graves’ disease, and Hashimoto's thyroiditis), as these parameters may be related to oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of cancer.

Material and methods

The study included patients diagnosed with Graves’ disease (n = 20), toxic multinodular goiter (n = 20), and Hashimoto thyroiditis (n = 20), and 20 healthy controls. HIF-1α levels were measured in blood samples and 8-OHdG levels were measured in urine – both via ELISA.

Results

HIF-1α and 8-OHdG levels were significantly higher in the patient groups than in the control group (p < 0.05). In the Hashimoto's thyroiditis patients a correlation was observed between 8-OHdG and thyroglobulin antibodies (p = 0.03). A significant relation was found between 8-OHdG and HIF-1α in the patient group (p < 0.01). Carcinoma was detected in 7 of 43 female patients, but not in any of the male patients. No difference was observed in 8-OHdG or HIF-1α levels between the patients with and without papillary carcinoma (p > 0.05). There was no significant difference in 8-OHdG or HIF-1α levels between the patients with biopsy results that were benign, malignant, and non-diagnostic (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

Serum HIF-1α and urine 8-OHdG levels were significantly higher in the patients with thyroid diseases; however, a relationship with cancer was not observed.

Keywords: hypoactive thyroid nodule, 8-OHdG, HIF-1α

Introduction

Carbonic anhydrases, having potential importance for the life of the cell in an acidic environment, occurring with glycolysis and hypoxia, play a role in ensuring pH regulation in normal tissue. In the case of hypoxia, many genes including KAIX and KAXII are over-expressed through HIF-1α. Carbonic anhydrase IX regulates hydrogen flow and it is argued that it mediates one of the hypoxic adaptation mechanisms when hypoxia is encountered [1]. Because it is over-synthesized in tumors with poor prognosis, it is seen as a potential target in cancer treatment. KAIX plays a role in cell proliferation and transformation [1]. KAIX is produced in stomach, biliary tractus, pancreas, small intestines, and seminal ductal epithelium. The hypoxia response element (HRE) being the binding site for HIF-1α occurs in the promoter region of KAIX. In several studies, it has been shown that hypoxic induction is not present in cell lines having a disorder in the HIF-1α pathway [1]. Mutations present in the nucleus of HRE lead to lack of the response to hypoxia. Thus, the importance of the HIF pathway in terms of the response was detected [2].

Solid lesions are exposed to conditions such as reduction of oxygen diffusion, and food intake during tumor formation, which leads to new vein formation and adaptation to hypoxic conditions [3, 4]. Increased HIF-1α levels also lead to the expression of genes associated with glycolysis, erythropoiesis, and angiogenesis [5]. Met protein is a receptor having high affinity for HGF. Two regions where HIF-1 can bind to the promoter region of Met have been determined and this suggested that it is responsible for increased gene transcription in some types of cancer. Obtained results showed that Met plays a key role in the pathogenesis of thyroid papillary carcinoma [6, 7].

The expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in thyroid carcinomas was investigated in a recent study. After evaluation of the regulation of HIF-1α and target gene expression in primary thyroid carcinomas and thyroid carcinoma cell lines (BcPAP, WRO, FTC-133 and 8505c), it was found that HIF-1α was not detectable in normal tissue but was expressed in thyroid carcinomas. Beside these, dedifferentiated anaplastic tumors (anaplastic thyroid carcinomas – ATCs) exhibited high levels of nuclear HIF-1α staining. In vitro studies revealed a functionally active HIF-1α pathway in thyroid cells with transcriptional activation. HIF-1 is functionally expressed in thyroid carcinomas and is regulated not only by hypoxia but also via growth factor signaling pathways and, in particular, the PI3K pathway. Given the strong association of HIF-1α with an aggressive disease phenotype and therapeutic resistance, it was predicted that this pathway could be an attractive target for improved therapy in thyroid carcinomas [8].

Oxidative stress affects the induction of DNA damage and DNA is the most biologically important target of oxidative attack by reactive species including free radicals [9]. Continuous oxidative DNA damage and cellular injury are caused by alteration of membrane permeability due to lipid peroxidation by reactive oxygen species. Reactive oxygen species are significant contributors to the age-related development of tumors and chemical carcinogenesis [10]. Free radicals may directly affect DNA and produce structural changes. Many free radicals are attacked by hydroxyl groups. Thus, DNA has a relation with genotoxic carcinogens [11]. 8-OHdG is a marker for oxidative DNA damage. It may be associated with lesions [12].

There are studies on the relations among oxidative DNA damage, cancer and inflammatory diseases. DNA being a stable molecule may suffer from spontaneous chemical oxidative damage. Major factors causing oxidative damage in DNA are ionized radiation, high oxygen concentration, chemicals, xanthine oxidase, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) [13]. The use of 8-OHdG levels in the urine and leukocyte DNA as an indicator of oxidative DNA damage is helpful in the evaluation of situations carrying carcinogenic risk [14]. Similarly, increased DNA damage indicators were determined in the lymphocytes obtained from individuals with autoimmune disease. 8-OHdG levels were found to be higher in autoimmune thyroid disorders, such as Graves’ disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis [15, 16].

Iodine deficiencies, nutrition with goitrogenic foods, or autoimmune events lead to diffuse thyroid hyperplasia. Some of these spontaneous mutations simulate growth by ensuring activation of the cAMP cascade. As a result, the gene expression of some growth factors (insulin-like growth factor 1 – IGF-1, transforming growth factor β1 – TGF-β1, epidermal growth factor – EGF) increase. The cells form small clones by splitting. Small clones start proliferation by self simulation. Thus, small focuses turn into nodule formation. Adenomas secreting TSH can reveal nodular formation in the thyroid tissue through similar pathways. There are the same mechanisms in some diseases such as Graves’ disease and acromegaly [17].

We aimed to evaluate the markers of oxidative stress and cancer in patients with toxic multinodular goiter, Graves’ disease, and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Furthermore, we investigated the correlation between serum markers and other data (clinical status, the presence of autoantibodies, cytological and histopathological results).

Material and methods

The study included 60 patients (43 females and 17 males; mean age: 50.93 ±13.68 years) with hypoactive thyroid nodules (single or multiple) who were diagnosed with Graves’ disease (n = 20, GD group), multinodular toxic goiter (n = 20, TG group), and Hashimoto's thyroiditis (n = 20, HT group), and 20 healthy controls (control group). The study protocol was approved by the Ege University, School of Medicine Ethics Committee. Patients were screened for other possible autoimmune diseases that may be associated with thyroid autoimmunity. The patients and controls were chosen from among non-smokers. All of the participants provided written informed consent to participate. Pregnant women and individuals in whom fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was contraindicated due to such risk factors as bleeding diathesis and anti-aging drug use were excluded from the study.

Thyroid function and thyroid autoantibodies in the patients were investigated, and parenchyma structure of the thyroid gland, the number, size, echogenicity, and activity of their nodules were determined via ultrasonographic and scintigraphic methods. Free T3, free T4, and TSH levels were measured using the electrochemiluminescence method: the reported reference ranges were as follows: free T3: 3.1–6.8 pmol l−1 (2.0–4.4 pg ml−1); free T4: 12–22 pmol l−1 (0.93–1.7 ng dl−1); TSH: 0.274.2 µIUml−1 (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH D-68298 Mannheim, Germany). The reference ranges for Anti-Tg Ab and anti-TOB Ab were 40 IU ml−1 and 35 IU ml−1, respectively, and these parameters were measured via Immulite Anti-Tg Ab and Anti-TPO Ab assay (Immulite 2000 Systems, Siemens, 2009). TSH receptor Ab levels were measured manually using the radioimmunoassay method; values < 1 U l−1 were accepted as negative, values of 1.1–1.5 U l−1 were accepted as positive at limits, and values > 1.5 U l−1 were accepted as positive (Immunotech, Beckman Coulter Company, France, 2008).

The patients’ thyroid glands were imaged ultrasonographically using a high-resolution broad-band linear probe (13–5 MHz frequency) and the nodular formations were measured across their long axes (Siemens, Antares, Germany, 2008). For scintigraphic evaluation of the thyroid gland a static image of 400 s 500 kcount−1 was obtained by focusing on the thyroid lodge using a pinhole collimator for 20 min after 5 mCi IV injection using pertechnetate Tc 99m (Elscint NM, Apex model SPX4, Israel, 2008). All patients were brought to the euthyroid state and FNAB of hypoactive thyroid nodules in the patients with Graves’ disease and toxic multinodular goiter, accompanied by ultrasonography, was performed according to the ATA guide (2006), and the biopsy specimens were cytologically examined.

Fine needle biopsy was not done from hyperactive nodules of toxic multinodular goiter. Nodules were considered hypoactive because the patients had Graves’ disease. As hypoactive nodules are associated with a high risk of malignancy (5–10%) and hyperactive nodules a much lower risk of malignancy (< 1%), hypoactive nodule samples were selected for both groups. All nodules in the Graves’ disease patients were hypoactive. Taken biopsy was eligible from hypoactive nodules in the toxic multinodular goiter group.

Cytopathological interpretation of FNAB results was evaluated as malignant/benign/non-diagnostic. Patients with suspicious and malignant cytology results underwent surgery (total/near total thyroidectomy). Microcarcinoma was defined as ≤ 10 mm in any direction. Blood and urine samples (20 cc) were collected to measure indicators of DNA damage (8-OHdG).

In vitro quantitative determination of human HIF-α1 concentrations

Human HIF-1 ELISA Kit was applied to serum samples taken from the patient and the control groups. This test was applied with the sandwich-based ELISA method. HIF-1α protein levels were quantified using the Human HIF-1α ELISA kit (Cusabio Biotech, Chine). The procedure was as described in the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Microplate Reader Multiscan FC (Thermo-Scientific). The HIF-1α protein concentration in each well was calculated using the equation of the HIF-1α standard.

Urinary 8-OHdG measurement via ELISA

Into each well of an 8-OHdG-coated microtiter plate, 50 µl of fresh urine sample and 50 µl of reconstituted primary antibody were placed, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h for ELISA (NWLSSTM Urine 8-OHdG ELISA Kit, Northwest Life Science Specialties, LLC). Secondary antibody was added to the plate, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the unbound enzyme-labeled sec ondary antibody was removed, and then the antibodies that were bound to the plate were identified using a substrate that contained 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine. Absorbance was measured using a computer-controlled spectrophotometric plate reader (Multiscan FC-Thermo-Scientific) at a wavelength of 450 nm. The concentration of 8-OHdG in the urine samples was interpolated from a standard curve drawn with the assistance of logarithmic transformation. The detection range of the ELISA assay was 0.5–200 ng ml−1. The urinary 8-OHdG level in each participant was normalized by the creatinine level in urine and was expressed as ng mg−1 of creatinine.

Statistical analysis

After determining whether numeric values were normally distributed, Student's t-test was used to compare 2 groups and one-way ANOVA was used to compare ≥ 3 groups with normally distributed variables. If ANOVA test results were significant, Dunnett's test was then applied. The Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for variables that were not normally distributed; however, χ2 analysis was used for categorical variables by forming cross tables.

Results

Markers related to functional thyroid disorders

Mean ages and distributions according to the gender of the patient groups are given in Table 1. The distribution of the groups in terms of age and gender was similar. TSH receptor antibody levels of the patients with Graves’ disease were significantly higher than other groups (p < 0.05). The autoantibodies of patients were examined. They were detected as significantly lower in patients with toxic multinodular goiter. There was no difference in terms of Anti-Tg and Anti-TPO between cases with Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves’ disease.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of groups

| Group | Mean age | Gender | Number of nodules (%) | Nodule size (%) | Nodule localization (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| mean ± SD | (F/M ratio) | single | two or more | 20 mm↓ | 20 mm↑ | right | left | bilateral | |

| A (n = 20) | 45.1 ±12.34 | 12/8 | 40 | 60 | 70 | 30 | 25 | 15 | 60 |

| B (n = 20) | 57.9 ±13.57 | 14/6 | – | 100 | 25 | 75 | – | – | 100 |

| C (n = 20) | 49.70 ±12.49 | 17/3 | 45 | 55 | 60 | 40 | 20 | 25 | 55 |

| A + B + C (n = 60) | 50.93 ±13.68 | 43/17 | 28.30 | 71.70 | 51.70 | 48.30 | 15 | 13.30 | 71.70 |

| control (n = 20) | 48.05 ±11.91 | 15/5 | |||||||

Patient groups (Group A/Group B/Group C) were evaluated in terms of some parameters (TSH receptor antibodies, thyroglobulin antibody, thyroperoxidase antibodies, HIF-1α, 8-OHdG).

A correlation between thyroglobulin in the Hashimoto thyroiditis group (Group C) was observed, supporting the existence of autoimmunity with 8-OHdG, an indicator of DNA damage (p = 0.03).

Markers related to pathology

The evaluation of HIF-1α and 8-OHdG parameters between groups is given in Table 2. 8-OHdG and HIF-1α parameters were found to be significantly higher in the patient group (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of the patient and the control group in terms of HIF-α and 8-OHdG parameters

| Group A + B + C | Control | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8-OHdG (ng/ml) (mean ± SD) | 22.26 ±12.41 | 5.11 ±2.44 | < 0.05 |

| HIF-1α (pmol/µl) (mean ± SD) | 1.11 ±0.82 | 0.74 ±0.16 | < 0.05 |

| n – number of patients | 60 | 20 | – |

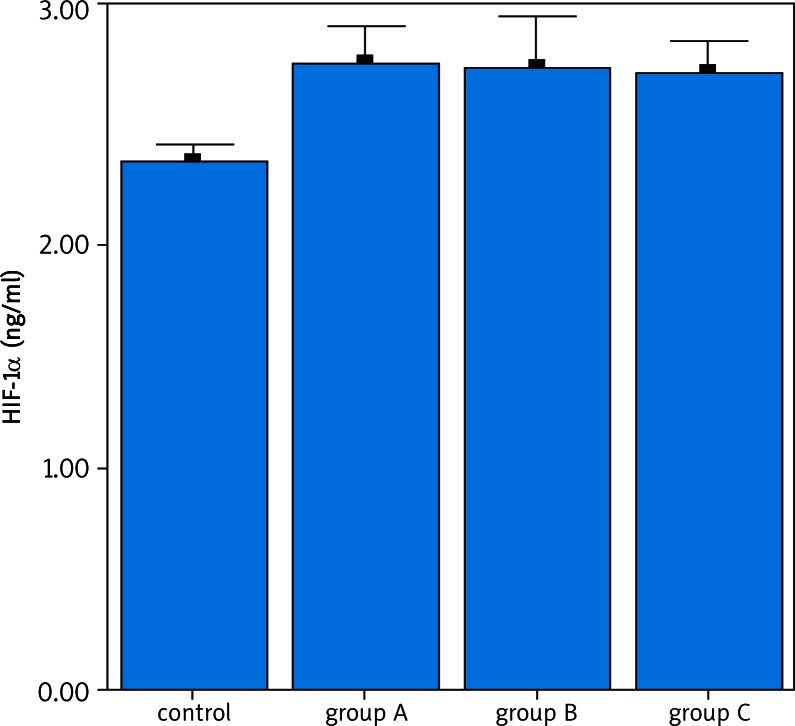

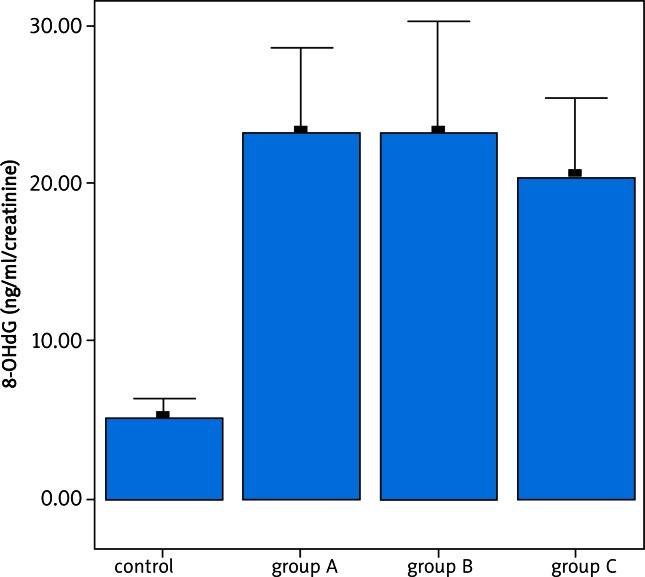

There was no difference in terms of 8-OHdG and HIF-1α among the patient groups (Figs. 1, 2). A correlation was not detected in terms of HIF-1α and 8-OHdG parameters among groups (Group A + C / B). In the patient group, there was a correlation between HIF-1α and 8-OHdG parameters (p < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Examination of HIF-1α cytokine between the patient and the control groups. A difference is determined between the patients and the control group in terms of HIF-1α levels (p < 0.05). No difference was found between the patient groups in terms of HIF-1α levels (p > 0.05)

Fig. 2.

Examination of DNA damage indicator between the patient and the control groups. A difference is determined in terms of 8-OHdG levels between the patients and the control group (p < 0.05). No difference is determined in terms of 8-OHdG levels between the patient groups (p > 0.05)

Biopsy results were positive for cancer in 7 of the 60 patients (11.6%) and were confirmed via histopathological examination, as follows: papillary carcinoma (n = 5 [8.3%]), papillary microcarcinoma (n = 1 [1.6%]), and papillary follicular variant (n = 1 [1.6%]). The distribution of the cytological findings in FNAB specimens is given in Table 3a.

Table 3a.

Distribution ratios of the cytological data obtained according to fine needle aspiration biopsy carried out from hypoactive thyroid nodule/nodules between the groups

| Biopsy | Group A | Group B | Group C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| benign | 95 | 19 | 70 | 14 | 65 | 13 |

| malign | 5 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 2 |

| non-diagnostic | – | 20 | 4 | 25 | 5 | |

Cytological distribution of FNAB specimens following repetition of non-diagnostics is shown in Table 3b. Pre-operative cytology and post-operative histology results are shown in Table 4.

Table 3b.

Cytological distribution of FNAs after repetition of non-diagnostics

| Biopsy | Group A | Group B | Group C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| benign | 95 | 19 | 90 | 18 | 80 | 16 |

| malign | 5 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 20 | 4 |

Table 4.

Pre-operative cytology and post-operative histology results

| Pre-operative cytology | Post-operative malign | Post-operative benign | |

|---|---|---|---|

| indeterminate | n = 11 | 2/11 | 9/11 |

| malign | n = 5 | 5/5 | – |

All patients who were diagnosed with carcinoma were female (16.3%). Carcinoma was diagnosed in 5% of the patients in the GD group (n = 1), 10% of the patients in the TG group (n = 2), and 20% of the patients in the HT group (n = 4); the difference between the 3 patient groups was not significant. The Graves’ disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis cases were thought to have autoimmune origin, as compared to the toxic multinodular goiter cases in terms of cancer frequency. The combined carcinoma frequency rate in the GD and HT groups was 12.5%, versus 10% in the TG group, and the difference was not significant. Mean age of the patients diagnosed with carcinoma was 44.28 ±15.05 years, versus 51.81 ±13.40 years in those without carcinoma; the difference was not significant.

We did not detect a significant relation among nodule dimension, nodule number, HIF-1α, and 8-OHdG. Additionally, there was no correlation between cytological findings in FNAB specimens (malignant/benign/non-diagnostic) and the number of nodules or nodule dimension. There was no relationship between patient age and the number or dimension of nodules, or between patient age and HIF-1α or 8-OHdG levels.

A statistically significant difference was not observed in HIF-1α or 8-OHdG levels between the patients with and without papillary carcinoma, nor was there a difference in HIF-1α or 8-OHdG levels between the patient groups with biopsy results that were benign, malignant, or non-diagnostic.

Discussion

Most thyroid nodules are histologically diagnosed as thyroid adenoma and differentiated from thyroid cancer. These lesions differ from autonomous functional thyroid nodules – including TSHR mutations – because they are associated with many disorders of genetic origin [18]. Functional disorders associated with cold thyroid nodules are caused by failed iodine transport or organification of iodine. Reduced expression of the Na/I symporter (NIS) and consequent insufficient iodine transport are observed in thyroid cancers, as well as in benign cold thyroid nodules [19]. The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between the indicators of inflammation, DNA damage, and cancer pathogenesis, and the disease and the nodule in patients with thyroid diseases of autoimmune origin having hypoactive thyroid nodule and with toxic multinodular goiter.

In the present study the toxic multinodular goiter group had the highest mean age, whereas the Graves’ disease group had the lowest, as previously reported. There were more females than males in each of the 3 patient groups. Nodular disease was observed 5–15 times more in the female patients; therefore, genetic predisposition and the effect of steroid hormones are considered causal factors. The growth stimulation effect of estrogen was reported in thyroid cancer cell lines in rats in vitro [20, 21].

In previous studies, it was found that the prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity was correlated with the increase of age and thyroid nodularity [22, 23]. However, a correlation was not found among thyroid autoimmunity, age and thyroid nodularity in our study.

Some studies have reported a relationship between oxidative DNA damage, and cancer and inflammatory diseases. An increase in the formation of oxygen radicals and a reduction in antioxidant enzyme levels, and/or the existence of a defect in DNA repair mechanisms lead to an increase in oxidative DNA damage [24, 25]. Human studies showed that DNA damage is an important mutagenic and carcinogenic factor [26]. It is thought that autoimmune thyroid diseases are associated with oxidative stress and 8-OHdG levels in mononuclear cell cultures obtained from patients with Graves’ disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. In the present study a correlation between the 8-OHdG level and thyroglobulin antibodies was observed, which supports the existence of autoimmunity in patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis (p = 0.03).

The level of 8-OHdG in patients with Graves’ disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis, which were untreated, was significantly higher than in healthy controls [11]. Thyroid hyperplasia increased the proliferation together with possible DNA damage due to H2O2 action. Similarly, in the present study 8-OHdG, an indicator of DNA damage, was significantly higher in the patients with Graves’ disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis than in the controls (p < 0.05).

Recent studies underline the importance of pH in the occurrence of cell death under hypoxic conditions [1]. The drop in oxygen pressure in the environment activates heterodimeric transcriptional regulators such as HIF-1. HIF-1 contributes to angiogenesis by directly increasing VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) formation [32]. It is argued with the data obtained from the study carried out by Pennacchietti and colleagues that Met plays a key role in the pathogenesis of thyroid papillary carcinoma. Two sections to which HIF-1 can be bound were determined on the Met promoter region, and this reminded that it is responsible for increased gene transcription in some cancer types [33]. In the study carried out by Stefania Scarpino and colleagues, it is underlined that Met protein phosphorylation and synthesis increase in tumor tissue, and there is a relation between HIF-1 and Met, and also the amount of both of them is high in tumor tissue, and this relation may be responsible for the invasion [6]. In our study, HIF-1α is an indicator that is thought to play a role in cancer pathogenesis in all patients receiving the diagnosis of Graves’ disease, toxic multinodular goiter, and Hashimoto thyroid. It was found to be significantly higher compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

In our study, there was no significant relation among age, nodule dimension, the number of nodules, and HIF-1α and 8-OHdG parameters. Also, there was no significant difference in terms of HIF-1α and 8-OHdG between the cases with and without papillary carcinoma. Similarly, no significant difference was detected among the patients whose fine-needle aspiration biopsy result is benign/malign/non-diagnostic/ indeterminate. In the literature, no study was found comparing fine needle aspiration cytology, histology, and markers (HIF-1α, 8-OHdG).

In a study carried out by Fiore and colleagues, a correlation between thyroid cancer and its autoimmunity was determined. In another study, it was suggested that thyroid autoimmunity may provide resistance to thyroid carcinoma [34, 35].

In some studies, it was found that the cancer development in hypoactive nodules of patients with toxic multinodular goiter was 7%, 21%, 9%, respectively [31–33]. In other studies, it was reported that the cancer frequency in patients with non-toxic multinodular goiter was 6.2%, 9.7%, 10.58%, respectively [33–35].

There are publications in the literature about hypoactive nodules – autoimmune thyroid diseases–cancer relations [36, 37]. In our study, there was no difference in terms of cancer formation between diseases of autoimmune origin (Graves and Hashimoto) and other patient group (toxic multinodular goiter). Similarly, there were reported conflicting results in the literature associated with the frequency of thyroid cancer in patients with toxic and nontoxic multinodular goiter [33, 38–40].

In the study carried out by Baier and colleagues, it was observed that the cases with malign cytology were younger (≤ 45 years). And the patients with non-diagnostic cytology were over 75 years old [39]. However, we did not detect a correlation among age, benign and malign cytological diagnosis in our study.

Kirtee Reparia and colleagues reported that the cancer rate was 19% in cases with nodule dimension smaller than 2 cm. And this rate in those with nodules bigger than 2 cm was 47% [40]. In our study, we did not find a relation between cancer and nodule size, because there was a limited number of cancer cases.

The results of thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsy can change depending on many factors (ultrasound device, endocrinologist, pathologist etc.). In our study, a high rate of malignancy (11.6%) was encountered. There are conflicting publications related to cytological diagnosis (benign/malign/non-diagnostic/indeterminate) in the literature [38, 39, 41, 42].

Ultimately, serum HIF-1α and 8-OHdG levels in the determination of carcinogenic potential in hypoactive nodules could be used as an indicator for early detection of cancer. Our results provide insights into the potential role of 8-OHdG and HIF-1α levels in patients with thyroid cancer. Also analyzing 8-OHdG from urine is an advantage due to the fact that it is a non-invasive method to detect oxidative stress. While the elevation of serum HIF-1α and 8-OHdG levels in thyroid disorders was found to be at a significant level, its relation with cancer was not significant. This was connected with the limited number of cases of cancer. It is difficult to signify as “malignant” nodules by evaluating these markers in the light of current literature and our data in clinical practice. However, considering the role of solid tumors other than thyroid, these markers are thought to play a role in thyroid cancer. In the next step, we have planned a study involving further testing with larger study groups.

References

- 1.Potter C, Harris AL. Hypoxia inducible carbonic anhydrase IX, marker of tumour hypoxia, survival pathway and therapy target. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:164–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wykoff CC, Beasley NJ, Watson PH, et al. Hypoxia-inducible expression of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7075–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jubb AM, Pham TQ, Hanby AM, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha, and carbonic anhydrase IX in human tumours. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:504–12. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.012963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, et al. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, et al. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 1998;394:485–90. doi: 10.1038/28867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scarpino S, Cancellario d'Alena F, Di Napoli A, Pasquini A, Marzullo A, Ruco LP. Increased expression of Met protein is associated with up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) in tumour cells in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. J Pathol. 2004;202:352–8. doi: 10.1002/path.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naldini L, Vigna E, Narsimhan RP, Gaudino G, Zarnegar R, Michalopoulos GK, Comoglio PM. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) stimulates the tyrosine kinase activity of the receptor encoded by the proto-oncogene c-MET. Oncogene. 1991;6:501–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burrows N, Resch J, Cowen RL, von Wasielewski R, Hoang-Vu C, West CM, Williams KJ, Brabant G. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha in thyroid carcinomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:61–72. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halliwell B. Why and how should we measure oxidative DNA damage in nutritional studies? How far have we come? Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1082–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valko M, Izakovic M, Mazur M, Rhodes CJ, Telser J. Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;266:37–56. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000049134.69131.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olinski R, Jaruga P, Zastawny TH. Oxidative DNA base modifications as factors in carcinogenesis. Acta Biochim Pol. 1998;45:561–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasai H. Analysis of a form of oxidative DNA damage, 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine, as a marker of cellular oxidative stress during carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1997;387:147–63. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(97)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutteridge JM, Halliwell B. Comments on review of Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, second edition, by Barry Halliwell and John M. C. Gutteridge. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;12:93–5. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90062-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dherin C, Dizdaroglu M, Doerflinger H, Boiteux S, Radicella JP. Repair of oxidative DNA damage in Drosophila melanogaster: identification and characterization of dOgg1, a second DNA glycosylase activity for 8-hydroxyguanine and formamidopyrimidines. Nucl Acids Res. 2000;28:4583–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.23.4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bashir S, Harris G, Denman MA, Blake DR, Winyard PG. Oxidative DNA damage and cellular sensitivity to oxidative stress in human autoimmune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:659–66. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.9.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hara H, Sato R, Ban Y. Production of 8-OHdG and cytochrome c by cultured human mononuclear cells in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Endocr J. 2001;48:671–5. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.48.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Studer H, Huber G, Derwahl M, Frey P. The transformation of Basedow's struma into nodular goiter: a reason for recurrence of hyperthyroidism. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1989;119:203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gimm O. Thyroid cancer. Cancer Lett. 2001;163:143–56. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00697-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann S, Schuchardt K, Reske A, Reske A, Emmrich P, Paschke R. Lack of correlation for sodium iodide symporter mRNA and protein expression and analysis of sodium iodide symporter promoter methylation in benign cold thyroid nodules. Thyroid. 2004;14:99–111. doi: 10.1089/105072504322880337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furlanetto TW, Nguyen LQ, Jameson JL. Estradiol increases proliferation and down-regulates the sodium/iodide symporter gene in FRTL-5 cells. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5705–11. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manole D, Schildknecht B, Gosnell B, Adams E, Derwahl M. Estrogen promotes growth of human thyroid tumor cells by different molecular mechanisms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1072–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berghout A, Wiersinga WM, Smits NJ, Touber JL. Interrelationships between age, thyroid volume, thyroid nodularity, and thyroid function in patients with sporadic nontoxic goiter. Am J Med. 1990;89:602–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90178-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laurberg P, Pedersen KM, Vestergaard H, Sigurdsson G. High incidence of multinodular toxic goitre in the elderly population in a low iodine intake area vs. high incidence of Graves’ disease in the young in a high iodine intake area: comparative surveys of thyrotoxicosis epidemiology in East-Jutland Denmark and Iceland. J Intern Med. 1991;229:415–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 2003;17:1195–214. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0752rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans MD, Cooke MS. Factors contributing to the outcome of oxidative damage to nucleic acids. Bioessays. 2004;26:533–42. doi: 10.1002/bies.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loft S, Vistisen K, Ewertz M, Tjønneland A, Overvad K, Poulsen HE. Oxidative DNA damage estimated by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine excretion in humans: influence of smoking, gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:2241–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.12.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999;13:9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pennacchietti S, Michieli P, Galluzzo M, Mazzone M, Giordano S, Comoglio PM. Hypoxia promotes invasive growth by transcriptional activation of the met protooncogene. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:347–61. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiore E, Rago T, Scutari M, et al. Papillary thyroid cancer, although strongly associated with lymphocytic infiltration on histology, is only weakly predicted by serum thyroid auto-antibodies in patients with nodular thyroid diseases. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009;32:344–51. doi: 10.1007/BF03345725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiore E, Rago T, Provenzale MA, et al. Lower levels of TSH are associated with a lower risk of papillary thyroid cancer in patients with thyroid nodular disease: thyroid autonomy may play a protective role. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:1251–60. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ríos A, Rodríguez JM, Balsalobre MD, Torregrosa NM, Tebar FJ, Parrilla P. Results of surgery for toxic multinodular goiter. Surg Today. 2005;35:901–6. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-3051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livadas D, Psarras A, Koutras DA. Malignant cold thyroid nodules in hyperthroidism. Br J Surg. 1976;63:726–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800630914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cerci C, Cerci SS, Eroglu E, Dede M, Kapucuoglu N, Yildiz M, Bulbul M. Thyroid cancer in toxic and non-toxic multinodular goiter. J Postgrad Med. 2007;53:157–60. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.33855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelizzo MR, Bernante P, Toniato A, Fassina A. Frequency of thyroid carcinoma in a recent series of 539 consecutive thyroidectomies for multinodular goiter. Tumori. 1997;836:53–5. doi: 10.1177/030089169708300305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sachmechi I, Miller E, Varatharajah R, Chernys A, Carroll Z, Kissin E, Rosner F. Thyroid carcinoma in single cold nodules and in cold nodules of multinodular goiters. Endocr Pract. 2000;6:5–7. doi: 10.4158/EP.6.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu FH, Hsueh C, Chang HY, Liou MJ, Huang BY, Lin JD. Sonography and fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of benign versus malignant nodules in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2009;37:487–92. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anil C, Goksel S, Gursoy A. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is not associated with increased risk of thyroid cancer in patients with thyroid nodules: a single-center prospective study. Thyroid. 2010;20:601–6. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rago T, Fiore E, Scutari M, et al. Male sex, single nodularity, and young age are associated with the risk of finding a papillary thyroid cancer on fine-needle aspiration cytology in a large series of patients with nodular thyroid disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:763–70. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baier ND, Hahn PF, Gervais DA, Samir A, Halpern EF, Mueller PR, Harisinghani MG. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules: experience in a cohort of 944 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1175–9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raparia K, Min SK, Mody DR, Anton R, Amrikachi M. Clinical outcomes for “suspicious” category in thyroid fine-needle aspiration biopsy: Patient's sex and nodule size are possible predictors of malignancy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:787–9. doi: 10.5858/133.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miseikyte-Kaubriene E, Ulys A, Trakymas M. The frequency of malignant disease in cytological group of suspected cancer (ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of nonpalpable thyroid nodules) Medicina (Kaunas) 2008;44:189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gul K, Ersoy R, Dirikoc A, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of thyroid nodules: comparison of ultrasonographic, cytological, and histopathological findings. Endocrine. 2009;36:464–72. doi: 10.1007/s12020-009-9262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]