Abstract

Aim of the study

The study examined the response rate, response duration and toxicity of vinorelbine and fluorouracil or vinorelbine alone in pretreated metastatic breast cancer.

Material and methods

Between June 2001 and September 2009, a group of 103 patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer, who had progressed after anthracycline/taxane chemotherapy, was treated with a vinorelbine-based regimen. The treatment consisted of vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 500 mg/m2 administered intravenously on days 1 and 8 of each cycle (53 patients) or vinorelbine alone at a dose of 30 mg/m2 on day 1 and 8 of the cycle, every 3 weeks (50 patients). Patients received chemotherapy as a second or further line of therapy. Treatment was continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The median age of patients treated with vinorelbine with 5FU was 54 years (range 38–76), and 55.5 years (range 38–73) in the group receiving vinorelbine monotherapy. A total of 417 cycles of chemotherapy were administered – 177 cycles of vinorelbine with 5-FU and 137 cycles of vinorelbine monotherapy. Patients were treated for a median of 4 cycles (range: 1 to 11 cycles). The evaluation of treatment effect was possible in 93 patients (10 patients received only one treatment cycle).

Results

The overall response rate (ORR) was 17% (7), including 2 (4%) complete responses (CR) and 5 (10.5%) partial responses (PR). Stable disease (SD) was observed in 50% of patients receiving vinorelbine with 5-FU (24 patients). In a group receiving vinorelbine alone the ORR was 20% (9), including 9 PR (20%) and 16 SD (35.5%). The median time to progression (TTP) for the entire group was 18 weeks (95% CI), 22 weeks among patients treated with vinorelbine with 5-FU and 16 weeks for a second group. The most common hematologic adverse events were neutropenia (20% of cycles) and thrombocytopenia (4%), with grade 3/4 incidence of 8% and 1.5% [according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI CTC)]. Nausea and vomiting were the most frequent non-hematologic forms of toxicity, occurring in 13% of cycles. The doses of cytotoxics were reduced in 26 (25%) cases. There were no treatment-related deaths.

Conclusions

Vinorelbine alone or in combination with 5-FU is an effective and safe treatment for pretreated advanced/ metastatic breast cancer patients. The combination of vinorelbine with 5-FU appears to be a more efficacious regimen than vinorelbine alone.

Keywords: breast cancer, winorelbine, chemotherapy, metastasis

Introduction

The results of treatment of advanced breast cancer have been slowly improving in recent years. The median overall survival in this group of patients ranges between 2 and 3 years. Palliative systemic treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer is based on sequential use of successive lines of therapy (chemotherapy, hormonal therapy or targeted therapy).

The first line of treatment consists of anthracyclines and taxanes. Capecitabine as the single agent or in combination with other drugs is the most commonly used regimen after anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy failure. The sequence and the efficacy of further lines of treatment are still being evaluated, and available data are based on single-center studies or retrospective analyses. Vinorelbine is a cytotoxic drug of proven efficacy in the first line treatment of metastatic breast cancer but now is most commonly used in further lines of therapy. Therefore it seems appropriate to assess the efficacy and tolerability of vinorelbine in the treatment failures in patients with advanced/metastatic breast cancer.

Aim of the study

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of vinorelbine-based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline/taxane-based regimen.

Material and methods

A total of 103 patients with metastatic breast cancer treated with vinorelbine-based regimens between January 2001 and October 2010 were enrolled in the study. Eligible patients were required to have received anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic disease. Patients were treated with one of the chemotherapy regimens summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Vinorelbine-based regimens used in the study

| Vinorelbine + 5-fluorouracil (number of patients – 53) | Vinorelbine (number of patients – 50) |

|---|---|

| vinorelbine 25 mg/m2 i.v. day 1 and 8 of cycle and 5-fluorouracil 500 mg/m2 i.v. day 1 and 8 | vinorelbine 30 mg/m2 i.v. day 1 and 8 of cycle |

Cycles were repeated every 3–4 weeks. Patients treated with an oral form of vinorelbine were not enrolled in the study. The selection of a treatment regimen was based on the earlier use of fluoropyrimidine (fluorouracil or capecitabine). Patients with HER2 receptor overexpression or HER2 gene amplification were previously treated with trastuzumab. Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of the study group.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of 103 patients with metastatic breast cancer

| Variables | Characteristics of study group (n = 103) | Characteristics of subgroups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-FU + vinorelbine (n = 53) | Vinorelbine (n = 50) | |||

| Age | median (years) | 55 | 54 | 55.5 |

| range (years) | 33–76 | 33–76 | 38–73 | |

| HER2 receptor overexpression or HER2 gene amplification | lack of HER2 overexpression/amplification | 83 (80.5%) | 43 (81%) | 40 (80%) |

| presence of HER2 overexpression or amplification | 202 (19.5%) | 10 (19%) | 10 (20%) | |

| Hormonal receptor status | positive | 51 (49.5%) | 22 (41.5%) | 29 (58%) |

| negative | 52 (50.5%) | 31 (58.5%) | 21 (42%) | |

| Performance status ECOG/WHO | PS = 0 | 22 (21.5%) | 10 (19%) | 12 (24%) |

| PS = 1 | 59 (57%) | 29 (55%) | 30 (60%) | |

| PS = 2 | 20 (19.5%) | 11 (21%) | 9 (18%) | |

| PS = 3 | 2 (2%) | 2 ( 4%) | ||

| Menopausal status | premenopausal/perimenopausal | 40 (39%) | 23 (43%) | 17 (34%) |

| postmenopausal | 63 (61%) | 29 (55%) | 34 (68%) | |

| The line of metastatic breast | median | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| cancer treatment with vinorelbine | range | 2–5 | 2–4 | 2–5 |

| Site of metastasis | liver | 46 (45%) | 30 (57%) | 16 (32%) |

| lungs | 48 (47%) | 26 (49%) | 25 (50%) | |

| soft tissue | 52 (50.5%) | 24 (45%) | 28 (56%) | |

| bone | 34 (33%) | 19 (36%) | 15 (30%) | |

| 1 | 45 (44%) | 20 (38%) | 25 (50%) | |

| 2 | 43 (42%) | 20 (38%) | 23 (46%) | |

| 3 | 15 (14.5%) | 13 (24.5%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Transaminase level | < 1.5 × ULN | 60 (58%) | 27 (51%) | 33 (66%) |

| > 1.5 × ULN | 43 (42%) | 25 (47%) | 18 (36%) | |

ULN – upper limit of normal

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) use was allowed in the case of neutropenic fever, infectious complications during neutropenia G3/G4 and as the secondary prophylaxis for patients who experienced febrile neutropenia during previous cycles. Ondansetron was administered as anti-emetic prophylaxis. Patients received 6 cycles of standard chemotherapy. Decisions to extend treatment beyond six cycles were made individually. The treatment was continued until progression of the disease or unacceptable toxicity.

The total number of cycles and doses of cytotoxics received by patients were summarized, and then the toxicity of therapy using the NCI CTC scale was evaluated (version 3). The efficacy was evaluated in patients who received at least two cycles of treatment, while those who received only 1 cycle were evaluated for toxicity only. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS). The evaluation of tumor response was performed according to WHO criteria.

MS Access 2007 was used to collect, store, and maintain the data regarding the treatment. To perform statistical analyses we used the statistical program Statistica 5.0.

Results

Among the group of 103 patients, 97 patients (94.5%) had tumor progression, and 6 patients (5.5%) are still receiving chemotherapy or are still alive without evidence of disease progression at the time of the most recent follow-up. A total of 417 cycles of chemotherapy were administered: 177 cycles of vinorelbine with 5-FU and 137 cycles of vinorelbine monotherapy. Patients were treated for a median of 4 cycles (range: 1 to 11 cycles).

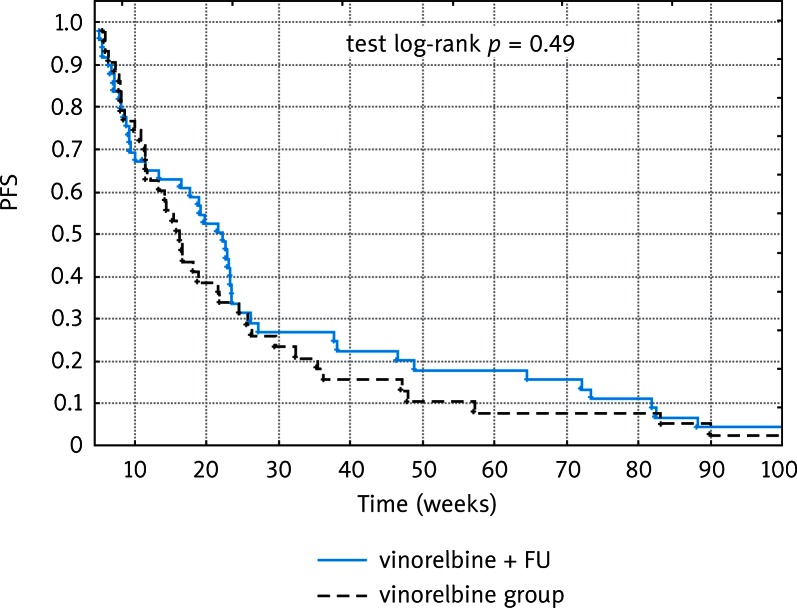

Thirty-one patients received at least 6 cycles of treatment. Ten patients were excluded from the evaluation of treatment efficacy due to receiving only one treatment cycle. The completion of treatment after one cycle was associated with a documented rapid progression of the disease in four cases, and six patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Therapeutic efficacy of vinorelbine-based chemotherapy was assessed in a group of 93 patients. Median progression-free survival (PFS) for the whole study group was 18 weeks (range: 6–253 weeks), 22 weeks for patients receiving vinorelbine and 5-FU (range: 6 to 253 weeks), and 16 weeks for a group treated with vinorelbine alone (range: 6–165 weeks). The progression-free survival curves for each of the treatment groups are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival for each of the treatment groups

The results of treatment in patients receiving vinorelbine and 5-FU or vinorelbine alone are compared in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of treatment for each study group

| Response | CR | PR | SD | SD 6 months + | Clinical benefit (CR + PR + SD 6 months +) | PD | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole group | 2 (2%) | 14 (14%) | 40 (43%) | 23 (25%) | 39 (42%) | 37 (40%) | 93 |

| Vinorelbine/5-FU | 2 (4%) | 5 (10.5%) | 24 (50%) | 17 (35.5%) | 24 (50%) | 17 (35.5%) | 48 |

| Vinorelbine | 0 | 9 (20%) | 16 (35.5%) | 6 (13%) | 15 (33%) | 20 (44.5%) | 45 |

A total of 39 patients (42%) achieved an objective response or stabilization of disease lasting for at least 6 months (clinical benefit), 24 (50%) patients treated with vinorelbine and 5-FU and 15 (33%) patients treated with vinorelbine alone. Overall survival was not assessed due to the different treatment regimens used after the vinorelbine-based chemotherapy failure.

The treatment-related toxicities were observed and reported during 198 cycles of the chemotherapy (47%), 123 cycles (54%) of vinorelbine/5-FU and 78 cycles (41%) of vinorelbine monotherapy.

The most common adverse events were hematologic toxicity (112 cycles), nausea and vomiting (54 cycles). Grade 3/4 adverse events were observed in 13% of cycles (53), with hematologic toxicity observed during 38 cycles. Injection site reaction and gastrointestinal disorders (mucositis, motility disorders) were frequent complications, leading to treatment discontinuation in four patients.

Characteristics of treatment-related toxicities are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Treatment-related toxicities

| Toxicity | Study group (417 cycles) | Vinorelbine + 5-FU (228 cycles) | Vinorelbine (189 cycles) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1–2 | G3–4 | G1–2 | G3–4 | G1–2 | G3–4 | |

| Neutropenia | 49 | 34 | 21 | 23 | 18 | 9 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 10 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Anemia | 25 | 8 | 16 | 3 | 9 | 5 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 50 | 4 | 36 | 4 | 14 | |

| Mucositis | 10 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | |

| Neuropathy | 16 | 8 | 6 | |||

| Constipation/motility disorders | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Phlebitis | 28 | 6 | 15 | 2 | 13 | 4 |

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor was used during 29% of cycles of chemotherapy (121 cycles), as the secondary prophylaxis in 86 cycles and as a part of the therapy in 35 cycles. We performed a single chemotherapy dose reduction in 26 patients.

Discussion

Vinorelbine was introduced for the treatment of breast cancer in the 1990s, in the same period as taxanes. Combination chemotherapy containing vinorelbine and doxorubicin has shown activity in the treatment of advanced breast cancer with response rates ranging from 57 to 74% as first-line therapy [1–3]. However, due to higher efficacy of paclitaxel and docetaxel, taxane and anthracycline-based chemotherapy has now become a standard first line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Due to the FDA approval of capecitabine after failure of anthracycline and taxane regimens [4], vinorelbine has been relegated to third- or fourth-line treatment. This justifies the need for evaluation of the efficacy and safety of vinorelbine in further lines of therapy. The choice between less toxic but also less efficacious monotherapy and more toxic combination chemotherapy leading to a higher response rate is a frequently discussed issue concerning palliative treatment of breast cancer. The difference in overall survival is questionable; therefore, many experts recommend individualizing the treatment based on the dynamics of the disease, and recommend the multidrug option for patients with a more aggressive course of the disease.

All of the patients in our study treated with vinorelbine alone were previously receiving anthracyclines, taxanes and fluoropyrimidine derivatives (5-FU or capecitabine). According to the literature, vinorelbine used in the second and subsequent lines of treatment produced objective response rates ranging from 20% to 36%, with duration of response of 3–6 months [1, 5–10]. These poor results are caused by cancer chemoresistance, worse tolerance of further lines of treatment and more advanced stages of the disease. These data correlate with the results obtained in our study group: overall response rate of 20%, clinical benefit rate of 33% and PFS of 16 weeks. The modest efficacy of this treatment has led to the modification of chemotherapy by dose intensification with prophylactic use of G-CSF [11, 12] or 4-day continuous infusion of vinorelbine [13]. These trials, however, failed to improve patients’ outcomes. Vinorelbine monotherapy was not superior to other single-agent therapies. The efficacy of vinorelbine monotherapy after anthracycline [7, 9] and taxane [14, 15] based chemotherapy failure is often disputed by the investigators. The authors of critical papers point to the fact that in the population of patients with anthracycline-resistant metastatic breast cancer, the overall response rate is in the range of 15–20%, which is similar to the results obtained in our study group. Therefore currently the use of a multidrug regimen after first line treatment failure is recommended. A number of studies have evaluated the efficacy of a combination of vinorelbine and mitomycin C [16–18] or cisplatin [14, 15]. The use of these regimens was associated with a response rate of 28–46%, with a response duration of 3–9 months. However, a high incidence of myelotoxicity was observed: 50% of patients experienced grade 3 to 4 neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia grade 3 occurred during 27% of cycles. Some authors [17, 18] recommend routine use of G-CSF during chemotherapy. Optimization of chemotherapy results by the use of vinorelbine/fluoropyrimidine regimens has been evaluated in many trials. Capecitabine/vinorelbine combinations in the treatment of anthracycline/taxane resistant metastatic breast cancer produce an objective response rate of 37–54% with median time to progression of 6.3–7.7 months [19, 20]. Those optimistic results were connected with a higher rate of myelotoxicity compared to our study group (leukopenia grade 3 in 40% of pts). Another way to improve the outcomes was the combination of vinorelbine with continuous infusion of 5-FU [21–25] resulting in ORR of 48–62% RR and median TTP of 24 weeks [22]. The overall response rate obtained in our study group was lower (14.5% RR), but the rate of stabilization lasting more than 6 months was higher (50% SD). Time to progression achieved in our population did not differ significantly in comparison to the literature data (PFS – 22 weeks). Bolus 5-FU instead of continuous infusion is a much more convenient way of drug administration. The grade 3/4 toxicity rate observed in our study group was comparable to the literature data. Another way to intensify the chemotherapy is by use of folinic acid/5-FU combination [25, 26]; however, the results are similar to those obtained by the continuous infusion of 5-FU (TTP 6.1–7.7 months). Regarding our results and the literature data, 5-FU/vinorelbine combination is an effective regimen in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer (there is a trend towards better outcome with prolonged exposure to these drugs). This treatment in a group of patients progressing after anthracycline/taxane containing chemotherapy has a favorable toxicity profile that makes it a reasonable part of the therapeutic algorithm.

In conclusions:

The use of vinorelbine-based chemotherapy as second or third-line treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer, who have progressed after an anthracycline/taxane-based regimen, led to progression-free survival (PFS) of 18 weeks for the entire study group, and 22 weeks and 16 weeks for patients treated with 5-FU/vinorelbine combination or vinorelbine alone, respectively.

Objective clinical benefit in terms of at least 6 months of stabilization or remission was observed in 39 patients of the entire study group (42%), 24 patients (50%) treated with vinorelbine/5-FU combination and 15 patients (33%) treated with vinorelbine alone. The combination of vinorelbine with 5-fluorouracil appears to be a more efficacious regimen than vinorelbine alone.

Vinorelbine-based chemotherapy has a favorable toxicity profile

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fumoleau P, Delozier T, Extra JM, Canobbio L, Delgado FM, Hurteloup P. Vinorelbine (Navelbine) in the treatment of breast cancer: the European experience. Semin Oncol. 1995;22(2 Suppl 5):22–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochster HS. Combined doxorubicin/vinorelbine (Navelbine) therapy in the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1995;22(2 Suppl 5):55–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spielmann M, Dorval T, Turpin F, et al. Phase II trial of vinorelbine/doxorubicin as first-line therapy of advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1764–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.9.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma S, Wong NS, Trudeau M, Joy A, Mackey J, Dranitsaris G, Clemons M. Survival differences observed in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with capectabine when compared with vinorelbine after pretreatment with antracycline and taxane. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:297–302. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000258125.97090.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terenziani M, Demicheli R, Brambilla C, et al. Vinorelbine: an active, non cross-resistant drug in advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;39:285–91. doi: 10.1007/BF01806156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barni S, Ardizzoia A, Bernardo G, Villa S, Strada MR, Cazzaniga M, Archili C, Frontini L. Vinorelbine as single agent in pretreated patients with advanced breast cancer. Tumori. 1994;80:280–2. doi: 10.1177/030089169408000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Degardin M, Bonneterre J, Hecquet B, Pion JM, Adenis A, Horner D, Demaille A. Vinorelbine (navelbine) as a salvage treatment for advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:423–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gasparini G, Caffo O, Barni S, Frontini L, Testolin A, Guglielmi RB, Ambrosini G. Vinorelbine is an active antiproliferative agent in pretreated advanced breast cancer patients: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2094–101. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.10.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones S, Winer E, Vogel C, et al. Randomized comparison of vinorelbine and melphalan in antracycline – refractory advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2567–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.10.2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber BL, Vogel C, Jones S, Harvey H, Hutchins L, Bigley J, Hohneker J. Intravenous vinorelbine as first-line and second-line therapy in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2722–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.11.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livingston RB, Ellis GK, Gralow JR, Williams MA, White R, McGuirt C, Adamkiewicz BB, Long CA. Dose-intensive vinorelbine with concurrent granulocyte colony-stimulating factor support in paclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1395–400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zelek L, Barthier S, Riofrio M, Fizazi K, Rixe O, Delord JP, Le Cesne A, Spielmann M. Weekly vinorelbine is an effective palliative regimen after failure with antracyclines and taxanes in metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92:2267–72. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011101)92:9<2267::aid-cncr1572>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toussaint C, Izzo J, Spielmann M, et al. Phase I/II trial of continuous infusion vinorelbine for advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2102–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.10.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray-Coquard I, Biron P, Bachelot T, et al. Vinorelbine and cisplatin (CIVIC regimen) for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer after failure of anthracycline- and/or paclitaxel containing regiments. Cancer. 1998;82:134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shamseddine AI, Taher A, Dabaja B, Dandashi A, Salem Z, El Saghir NS. Combination cisplatin-vinorelbin for relapsed chemotherapy-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:298–302. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199906000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agostara B, Gebbia V, Testa A, Cusimano MP, Gebbia N, Callari AM. Mitomycin “C” and vinorelbine as second line chemotherapy for metastatic breast carcinoma. Tumori. 1994;80:33–6. doi: 10.1177/030089169408000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kornek GV, Haider K, Kwasny W, et al. Effective treatment of advanced breast cancer with vinorelbine, mitomycin C plus human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1668–73. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheithauer W, Kornek G, Haider K, Kwasny W, Schenk T, Pirker R, Depisch D. Effective second line chemotherapy of advanced breast cancer with Navelbine and mitomycin C. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1993;26:49–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00682699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolè F, Catania C, Munzone E, et al. Capecitabine/vinorelbine: an effective and well tolerated regimen for women with pretreated advanced-stage breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2006;6:518–24. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan Y, Xu B, Yuan P, et al. Prospective study of vinorelbine and capecytabine combination therapy in Chinese patients with metastatic breast cancer pretreated with antracyclines and taxanes. Chemotherapy. 2010;56:340–7. doi: 10.1159/000320186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zambetti M, Demicheli R, De Candis D, et al. Five-day infusion fluorouracil plus vinorelbine i.v. in metastatic pretreated breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;44:255–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1005769604001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pieńkowski T, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A. Five-day infusion of fluorouracil and vinorelbine for advanced breast cancer treated previously with antracyclines. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 2001;21:111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuart NS, McIllmurray MB, Bishop JL, et al. Vinorelbine and infusional fluorouracil in antracycline and taxane pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Clin Oncol. 2008;20:152–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berruti A, Sperone P, Bottini A, et al. Phase II study of vinorelbine with protracted fluorouracil infusion as a second- or third-line approach for advanced breast cancer patients previously treated with antracyclines. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3370–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.19.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebbia V, Caruso M, Borsellino N, et al. Vinorelbine and 5-fluorouracil bolus and/or continuous venous infusion plus levofolinic acid as second line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: an analysis of results in clinical practice of the Gruppo Onclogico Italia Meridionale (GOIM) Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3143–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliva C, Bergnolo P, Inguì M, et al. Vinorelbine and fluorouracil plus leucovorin combination (ViFL) in patients with anthracycline and taxane pretreated metastatic breast cancer: a phase II study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:411–7. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0671-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]