Abstract

Oxidative phosphorylation couples ATP synthesis to respiratory electron transport. In eukaryotes, this coupling occurs in mitochondria, which carry DNA. Respiratory electron transport in the presence of molecular oxygen generates free radicals, reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are mutagenic. In animals, mutational damage to mitochondrial DNA therefore accumulates within the lifespan of the individual. Fertilization generally requires motility of one gamete, and motility requires ATP. It has been proposed that oxidative phosphorylation is nevertheless absent in the special case of quiescent, template mitochondria, that these remain sequestered in oocytes and female germ lines and that oocyte mitochondrial DNA is thus protected from damage, but evidence to support that view has hitherto been lacking. Here we show that female gametes of Aurelia aurita, the common jellyfish, do not transcribe mitochondrial DNA, lack electron transport, and produce no free radicals. In contrast, male gametes actively transcribe mitochondrial genes for respiratory chain components and produce ROS. Electron microscopy shows that this functional division of labour between sperm and egg is accompanied by contrasting mitochondrial morphology. We suggest that mitochondrial anisogamy underlies division of any animal species into two sexes with complementary roles in sexual reproduction. We predict that quiescent oocyte mitochondria contain DNA as an unexpressed template that avoids mutational accumulation by being transmitted through the female germ line. The active descendants of oocyte mitochondria perform oxidative phosphorylation in somatic cells and in male gametes of each new generation, and the mutations that they accumulated are not inherited. We propose that the avoidance of ROS-dependent mutation is the evolutionary pressure underlying maternal mitochondrial inheritance and the developmental origin of the female germ line.

Keywords: cytoplasmic inheritance, maternal inheritance, Aurelia aurita, mitochondrial genome, oxidative phosphorylation, aging, Weismann barrier

1. Mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondria are the double-membrane-bounded bioenergetic organelles found in the cytoplasm of most eukaryotic cells. Their outer membrane allows free passage of different solutes by a variety of intrinsic carriers. Their inner membrane, in contrast, is a broadly impermeable insulating layer that harbours the respiratory chain and separates the inter-membrane space (the electrochemically positive or P-phase) from the mitochondrial matrix (the electrochemically negative or N-phase) during chemiosmotic ATP synthesis [1]. The mitochondrial matrix is homologous to the bacterial cytoplasm, harbouring a genome, 70S ribosomes and a complete apparatus of gene expression [2,3] that amply document the proteobacterial origin of the organelle via endosymbiosis [4–7]. Mitochondrial DNA, first observed in chick embryo [8] and fungi [3,9] and sequenced for humans [10], is typically small. In metazoa, mitochondria contain 13 protein-coding genes for subunits of the energy-transducing electron transport chain of the mitochondrial inner membrane [11]. The overwhelming majority of mitochondrial proteins are nuclear encoded, synthesized as precursors on cytosolic ribosomes and imported into the organelle [12,13]. This paper deals with the biological reasons behind the retention of a few protein-coding genes in mitochondria and the evolutionary consequences thereof for animal development and ageing.

2. Cytoplasmic, maternal, non-Mendelian inheritance: why are there genes in mitochondria?

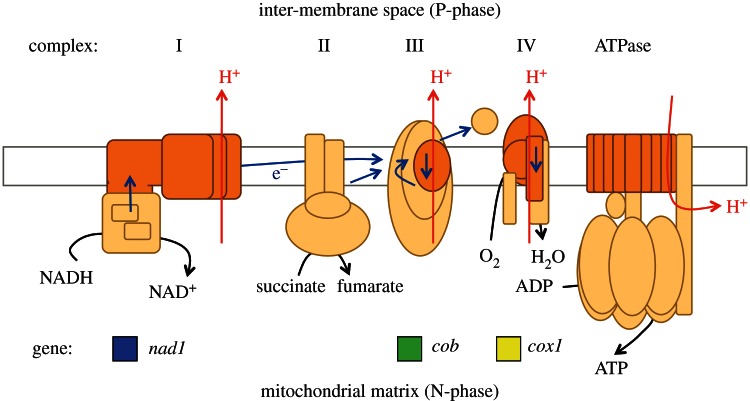

Figure 1 is a schematic outline of an animal mitochondrial inner membrane. Five multi-subunit protein complexes are involved in the energetic coupling of respiratory electron transport to synthesis of ATP—the process of oxidative phosphorylation. Complexes I, III and IV of the electron transport chain, which transports protons across the inner membrane, and the ATPase, which harnesses that proton gradient, are chimeras, with some subunits synthesized on mitochondrial ribosomes and others imported from the cytosol. This apparently untidy arrangement of separate gene locations leads to two different modes of inheritance. Nuclear genes segregate in a Mendelian manner, while genes in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) are cytoplasmically inherited in a non-Mendelian manner. In animals, mtDNA is usually transmitted uniparentally through the maternal line [2,15–17].

Figure 1.

Outline diagram of a mitochondrial inner membrane. Respiratory chain protein complexes I, II, III and IV and the coupling ATPase are plugged through the membrane, which is represented by a horizontal rectangle. In transfer of electrons (e–), complexes I, III and IV transport protons (H+) outwards, across the membrane, from the mitochondrial matrix (N-phase) to the inter-membrane space (P-phase) and so generate a transmembrane proton gradient that provides energy for synthesis of ATP, which is coupled to proton re-entry into the matrix. Polypeptide subunits are depicted schematically and colour coded to indicate that the proton-translocating complexes contain subunits (dark orange) that are encoded in mitochondrial DNA as well as subunits (peach) that are encoded in nuclear DNA. The three mitochondrial genes chosen for this study encode individual subunits of complexes with which their gene names are aligned vertically: nad1 (complex I), cob (complex III) and cox1 (complex IV). Adapted from [14].

Chloroplasts of plants also carry DNA, and are agents of cytoplasmic inheritance for the same reason. Like mitochondria, chloroplasts transduce energy and use a proton-motive force—albeit light driven through photosynthesis—as the intermediate between electron transport and ATP synthesis [18]. In mitochondria and chloroplasts, there is a correlation between membrane-intrinsic proton-motive electron transport and retention of a genetic system, derived originally from a prokaryotic endosymbiont ancestor [19]. Indeed, mitochondria that no longer perform oxidative phosphorylation relinquish their DNA [20–23].

Mitochondria and chloroplasts both stem from bacterial ancestors with large genomes; import the majority of their proteins; and the DNA of both organelles is highly reduced in size. However, in a striking case of multiple convergent evolution, the independent evolutionary reduction of two different bioenergetic organelles has arrived at exactly the same endpoint: a few membrane-associated components of the energy-harnessing electron transport chain and core components of the 70S ribosomes permitting the former's synthesis [14]. This convergence has occurred independently, in parallel, in countless eukaryotic lineages. Can any selective pressure account for this massively parallel evolution towards the same gene sets for two independently derived bioenergetic organelles, and across all known eukaryotic lineages? If the ancestral endosymbiont eventually donated the great majority of surviving genes to the nucleus of the host cell, then why do any genes at all remain?

Among the many proposals that have been put forward to account for the retention of genomes and genetic systems in mitochondria and chloroplasts [12,24–29], one hypothesis applies equally to mitochondria and chloroplasts [19]. It posits that the retention of a given gene within a bioenergetic organelle is the result of natural selection, whereby the corresponding selective advantage for the individual organelle is the ability of the organelle to sense and respond to changes in the redox state of its bioenergetic membrane by being able to regulate the synthesis of proteins in the electron transport chain by means of gene expression. This hypothesis, now named ‘CoRR’ for ‘co-location for redox regulation’ [14,24], mechanistically links (a) the main benefit of bioenergetic organelles, namely energy-harvesting redox chemistry, with (b) their main evolutionary risk, namely generation of hazardous ROS if redox chemistry is unregulated, while accounting for the circumstance (c) that (b) can only be avoided if genes involved in the synthesis of functional complexes in the electron transport chain reside in the same cellular compartment as their gene products [14,24].

There is, so far, more evidence for CoRR in chloroplasts [30,31] than in mitochondria [32]. However, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and predictions of CoRR for mitochondria are clear [33]. In particular, the prokaryotic-derived chloroplast redox sensor kinase has now been identified [34]. As further predicted, this chloroplast sensor kinase has an essential role in photosynthetic control of chloroplast DNA transcription [18,34,35]. CoRR predicts that a mitochondrial redox sensor kinase plays a corresponding role in redox control of respiratory electron transport through effects on mitochondrial gene expression.

3. The mitochondrial theory of ageing

As outlined above, mitochondria are a potentially disastrous location for any genome, however small, because of the mutational effects of ROS.

Energy-conserving aerobic respiratory electron transport terminates with concerted four-electron reduction of molecular oxygen to give two molecules of water, a reaction usually coupled to proton translocation across the inner membrane and catalysed by the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase. However, molecular oxygen is also readily reduced, at a number of different points in the respiratory chain, by transfer of a single electron, in which case the product is the superoxide anion radical, O2•− [36–40]. Superoxide is a short-lived free radical that reacts rapidly with any of a wide range of chemical substrates, including itself. Superoxide engages spontaneously in disproportionation, or dismutation, a reaction that is also catalysed by the enzyme superoxide dismutase [41]. Superoxide dismutase is ubiquitous in aerobic organisms and also present in many anaerobes; in all cases, it is thought to provide a degree of protection from oxygen toxicity [42–45]. The products of the reaction are oxygen and peroxide, O22–, which becomes protonated to give hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, at neutral pH.

These and other ROS chemically modify cellular constituents, including lipids [46], proteins [47] and nucleic acids, the latter including production of thymine dimers [48]. Because of those reactions, the univalent reduction of oxygen is both cytotoxic and mutagenic. Where ROS react with mitochondrial DNA, the result may be a modified respiratory chain protein that becomes more prone to univalent reduction of oxygen, thus increasing the frequency of mutation. In this way, it is proposed that a vicious circle of self-augmenting mutational load in mitochondrial DNA may be a primary cause of ageing and of many of its associated degenerative diseases [49–53], including cancer [54].

It is, however, still debated whether the mitochondrial theory of ageing, as previously proposed, is central to the ageing process, part of a multi-factorial mechanism, or perhaps not related to ageing at all [55,56]. Some studies suggest that ageing-related mtDNA mutations may arise from DNA replication errors rather than ROS-induced damage [57], which may subsequently trigger downstream apoptotic markers rather than ROS production [58]. Other work proposes that ageing processes induced by mtDNA mutations do not involve ROS production [59,60]. Conversely, recent studies support the mitochondrial theory of ageing [61–69].

If the mitochondrial theory of ageing is correct, it then raises a second problem—how is mitochondrial DNA transmitted into each successive generation in a form that is uncorrupted by the mutations that have accumulated in the parents by the time they reach reproductive age? In short, why is ageing not inherited?

4. Separate sexes and mitochondrial division of labour

As a solution to this problem, it has been proposed that oocytes contain genetically repressed, template mitochondria that are retained within the female germ line to be transmitted, in the oocyte cytoplasm, between generations [70]. According to this hypothesis, sperm mitochondria are subject to ROS-induced mutagenesis since they are required to produce ATP for motility. If sperm mitochondrial DNA were retained, after fertilization, by the zygote, then males would transmit damaged mitochondrial DNA to their offspring. Male gametes and somatic cells of both sexes are predicted to contain energetically functional mitochondria, active in transcription of their DNA. In contrast, oocytes are predicted to obtain ATP by fermentation, by anaerobic respiration, or by import from neighbouring somatic cells [70,71]. This hypothesis (figure 2) is consistent with maternal, cytoplasmic, non-Mendelian inheritance of mitochondrially encoded phenotypic characters. The hypothesis is also consistent with sperm mitochondria, including paternal mitochondrial DNA, being targeted for autophagy and degraded soon after fertilization [72–74]. Paternal and somatic mitochondria provide energy without genetic information.

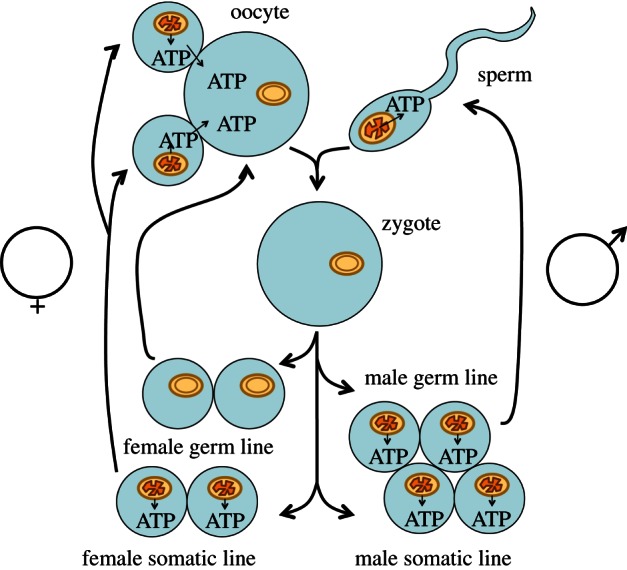

Figure 2.

Hypothesis: sequestration of mitochondria of the female germ line as genetic templates, inactive in ATP synthesis. After fertilization, a female gamete (oocyte) carries template mitochondria into the zygote, while the ATP-producing sperm mitochondrion fails to survive, its task completed. During subsequent development, the female germ-line retains only the template mitochondria inherited from the mother. These template mitochondria never differentiate into ATP-synthesizing mitochondria, but perpetuate undamaged copies of mitochondrial DNA. In contrast, the male germ-line and both female and male somatic cell lines develop energetically functional mitochondria, with inner membranes as depicted in figure 1, and which perform ATP synthesis. In contrast, female gametes and female germ cells never synthesize ATP by oxidative phosphorylation, incur no penalty of mutation initiated by respiratory electron transport, and their mitochondria are transmitted from mother to daughter. Adapted from [70].

Predictions of the hypothesis described here, and depicted in figure 2, amount, so far, to proposed explanations of existing knowledge. Nevertheless, the hypothesis makes novel predictions, and a number of experimental and observational studies have the capacity to yield results that will disprove it. Here we describe the results of novel experiments designed to reveal whether oocyte mitochondria satisfy one major requirement of the hypothesis outlined in figure 2: are oocyte mitochondria transcriptionally silent, morphologically distinct and functionally quiescent?

5. Experimental system: the moon jellyfish, Aurelia aurita

The genus Aurelia belongs to the class Scyphozoa within the phylum Cnidaria [75]. Cnidaria are an ancient animal phylum, with the palaeontological record [76] and evolutionary inference [77] suggesting an origin prior to the Middle Cambrian period [78,79], or perhaps even during the late Proterozoic era, up to 700 million years ago [80], and before the emergence of the Bilateria [81]. Cnidaria are simple organisms consisting of an endoderm and ectoderm, between which is a largely acellular and watery ‘mesogloea’ that defines their gelatinous body. The Scyphozoa, or ‘true’ jellyfish, exhibit alternation of generations between a sexually reproductive phase, the medusa, and an asexual phase, the polyp [82]. The medusae are typically dioecious.

The genus Aurelia is found throughout the world's oceans [83], with A. aurita a very typical scyphozoan in terms of reproduction and development [84]. In wild populations, most medusae live for less than a year, dying following gamete release [84]. Horseshoe-shaped gonads are located within the gastric cavity. Fertilization is external, after which fertilized eggs transfer into brood sacs on oral arms hanging down below the umbrella where they develop into ciliated planula larvae. The mitochondrial genome of A. aurita is composed of 13 energy transduction protein-coding genes, small and large subunit rRNAs, and methionine and tryptophan tRNAs [85]. As one of the most ancient dioecious metazoan ancestors alive, jellyfish can be considered an ideal model organism of choice for studying evolutionarily conserved elemental features, which may span the entire animal kingdom.

6. Mitochondrial transcription

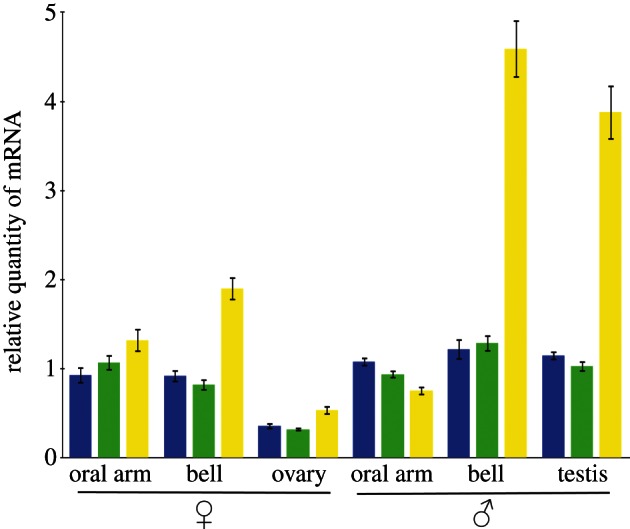

Mitochondrial DNA transcription is a requirement for oxidative phosphorylation in vivo. We performed qRT-PCR analysis to estimate the relative quantity of mitochondrial transcript of one polypeptide subunit from each of the three proton-motive respiratory chain complexes outlined schematically in figure 1. Figure 3 shows the relative quantity of mRNA from the genes nad1, cob and cox1 in somatic tissue samples from the bell and oral arm of male and female medusae, the motile, reproductive phase, and from the female and male gonads—ovary and testis. For ovary and testis samples, a mixed population of gamete cells and surrounding diploid cells were pooled together. For all three genes, mRNA is lowest in ovary, while testis mRNA quantities are close to those of somatic tissue, notably the male bell. In males, the bell, with a high proportion of contractile tissue, appears to have the most mRNA for all three mitochondrial genes, and especially for the cox1 subunit of cytochrome oxidase, the terminal electron acceptor for aerobic respiration. Similarly, sperm mitochondria seem to have higher amounts of cox1 transcripts. This result fits with the assumption that oxygen supply may be a limiting factor for contractions of the bell and sperm flagellar movement. Bell contraction provides propulsion and, together with osmoconformation, [86] maintains position in the water column.

Figure 3.

Relative quantities of mRNA from the mitochondrial genes nad1 (blue), cob (green) and cox1 (yellow) in different tissue samples from male and female medusae of the jellyfish, Aurelia aurita. mRNA quantities are colour coded according to the gene transcribed, as indicated also in figure 1. Mitochondrial mRNA quantities are expressed relative to those from the nuclear gene α-tubulin, and the ratio then expressed relative to the corresponding value for oral arm somatic tissue. Error bars stand for ±s.e.m. of three biological replicates. P < 0.05.

7. Mitochondrial ultrastructure

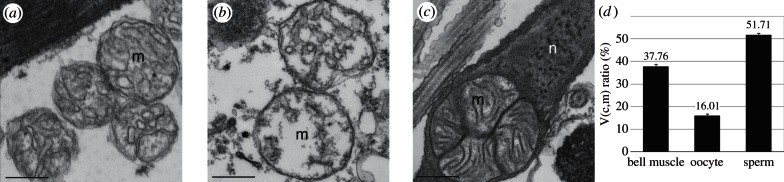

Figure 4a shows a transmission electron micrograph of a thin section of cells of a female A. aurita bell. Mitochondria (m) are seen to possess characteristic morphology, with an internal network of cristae; invaginations of the inner membrane into the mitochondrial matrix; and the sites of respiratory electron transport and ATP synthesis. The male bell is similar in ultrastructure (results not shown). Figure 4b shows the corresponding electron micrograph of an A. aurita oocyte; oocyte mitochondria appear slightly larger and morphologically less complex than in the bell (figure 4a). Figure 4c shows the head of an A. aurita spermatozoan in which the nucleus (n) lies adjacent to large, morphologically complex mitochondria (m) with numerous cristae. The contractile filaments of the flagellum consume ATP for the mechanochemical motor driving sperm motility and are in close proximity to the fully differentiated mitochondria, which can be assumed to function primarily as electrochemical fuel cells to supply the required ATP. In order to quantify the morphological variations seen in these tissues (figure 4a–c), we performed stereological analysis of jellyfish mitochondria of bell muscle, oocyte and sperm, as shown in figure 4d.

Figure 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of A. aurita tissue samples. Differences in mitochondrial morphology are observed in cross-sections through (a) female bell, (b) oocyte and (c) spermatozoon. Mitochondria (m), nucleus (n). Scale bars, 500 nm. Stereological analysis of the morphological variations amongst the three samples is shown in (d). Error bars represent s.e.m, P < 0.01.

8. Mitochondrial membrane potential

The intermediate that couples electron transport with ATP synthesis-hydrolysis in mitochondrial energy transduction is the proton-motive force [87], a chemiosmotic gradient of electrical potential across the mitochondrial inner membrane, typically of −180 mV [88].

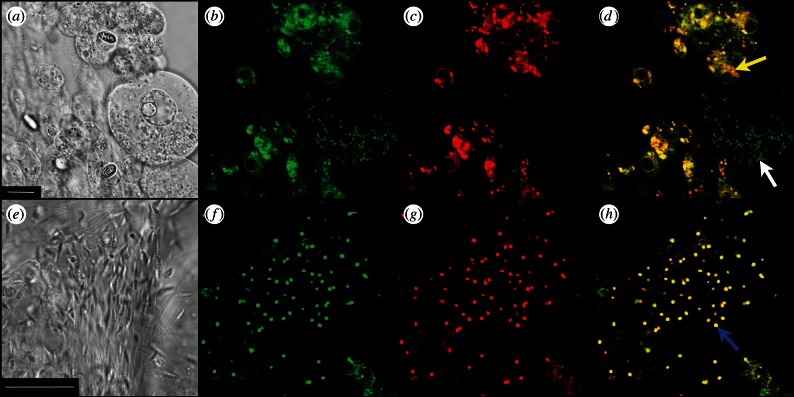

Confocal microscopy was used to visualize the activity of mitochondria in gonad tissue of male and female jellyfish. Figure 5a shows the bright field image of Aurelia ovarian tissue, with a scale bar of 10 µm. Figure 5b shows that mitochondria appear to be green because of their uptake of the fluorescent dye Mitotracker Green FM. Comparison of figure 5a and figure 5b shows that mitochondria are present, but less conspicuous, in the oocyte to the right of the picture than they are in the smaller, neighbouring, diploid cells. Figure 5c shows the same view of a sample of Aurelia ovarian tissue, this time visualized with Mitotracker Red FM, which reports specifically on the presence of the membrane potential. In surrounding diploid cells, the pattern of mitochondrial distribution seen with Mitotracker Red (figure 5c) agrees with that seen as the green colour of Mitotracker Green (figure 5b). However, and in contrast, oocyte mitochondria are unstained by Mitotracker Red (figure 5c), suggesting that oocyte mitochondria sustain little or no proton flux driven by membrane potential. Figure 5d is an overlay of the images in figure 5b,c, where the red and green colours of Mitotracker combine to show active mitochondria in yellow or orange. Mitochondria with low or absent membrane potential remain green, as Mitotracker Green does not respond to membrane potential. This technique has been previously described in [89].

Figure 5.

Mitochondrial membrane potential in male and female gonad samples of live A. aurita. Confocal light microscopy bright field view (a,e). Scale bars, (a) 10 µm; (e) 25 µm. Mitotracker Green FM (ex/em: 488/520 nm) detects the presence of mitochondria regardless of its activity levels (b,f). Conversely, Mitotracker Red FM (ex/em: 581/644 nm) is imported into active mitochondria proportionally to their membrane potential (c,g). Overlay images are shown in (d,h). Yellow arrow indicates the female diploid cell mitochondria, white arrow indicates oocyte mitochondria and the blue arrow indicates sperm mitochondria.

Figure 5e–h presents results obtained with Aurelia sperm cells. Figure 5e is the bright field view of Aurelia sperm, with a 25 µm scale bar. Figure 5f shows the same cells visualized with Mitotracker Green, which specifically reveals a single mitochondrion lying posterior to the nucleus of each cell, as also seen by electron microscopy in figure 4c. Figure 5g, with the membrane potential-reporting Mitotracker Red, shows a picture essentially identical to that in figure 5b, but with green replaced by red—clearly all Aurelia sperm mitochondria carry a membrane potential, consistent with their primary role in ATP synthesis, serving sperm motility. Figure 5h presents the overlay of figure 5b,c, and all sperm mitochondria fully in the plane of focus are seen in yellow.

The results shown in figure 5 again correlate with the conclusion from transcription (figure 3) and ultrastructure (figure 4)—oocyte mitochondria (figure 5a–d) are specifically deficient in respiratory electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation, while sperm mitochondria, in contrast, are energetically fully functional (figure 5e–h).

9. Production of ROS

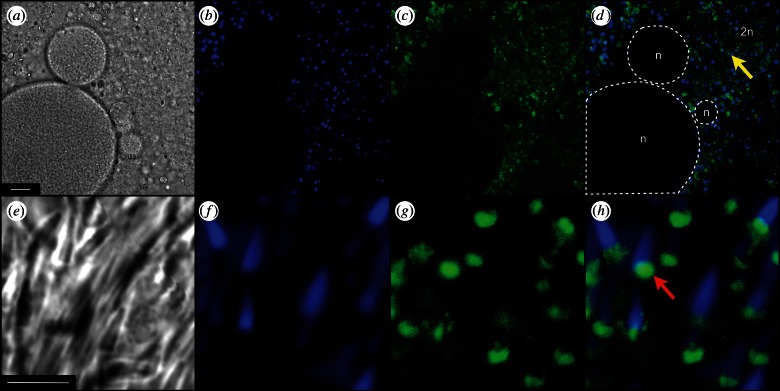

Figure 6a again shows Aurelia ovary in bright field light microscopy. Figure 6b shows the same tissue where the blue colour arises from 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), a specific stain for DNA. Figure 6c shows green fluorescence from the oxidized form of 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA), reporting on production of ROS [90]. Figure 6d is an overlay of figure 6b,c, and suggests that oocytes (within white dashed lines) generate little or no ROS. Conversely, surrounding gonad diploid cells seem to produce enough ROS to oxidize H2DCF-DA, which subsequently emits the observed green fluorescence at the 520 nm range.

Figure 6.

ROS content in male and female gonad samples of live A. aurita. Confocal light microscopy bright field view (a,e). Scale bars, (a) 25 µm; (e) 5 µm. 4',6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (ex/em: 350/450 nm) detects the presence of nuclear DNA (b,f). 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) (ex/em: 488/520 nm) imported into cells undergoes oxidation in the presence of ROS and emits green fluorescence (c,g). Overlay images are shown in (d,h). Yellow arrow indicates mitochondria in a female diploid cell, in the region labelled as ‘2n’, white dashed lines delimit oocytes, also labelled as ‘n’, and the red arrow indicates sperm mitochondria.

Figure 6e shows Aurelia sperm in bright field. Figure 6f shows the blue colour from sperm carrying DNA-staining DAPI. Figure 6g shows active production on ROS by H2DCF-DA in all the sperm seen in figure 6e,f. Figure 6h is an overlay, showing the blue of DAPI in the nucleus of each sperm cell anterior to the green fluorescence reporting production of ROS in the large active mitochondria. These results, from confocal light microscopy, are consistent with the sperm ultrastructure seen, by electron microscopy, in figure 4c.

10. Conclusion: oocyte mitochondria are quiescent

The results presented here provide independent lines of evidence concerning four ways in which oocyte mitochondria are distinct from sperm mitochondria and from mitochondria of somatic cells in A. aurita.

Aurelia aurita oocyte mitochondria are distinct in:

— showing decreased transcript levels of three mitochondrial genes encoding subunits of respiratory electron transport chain complexes (figure 3);

— having a simple membrane structure, without extensive internal cristae (figure 4);

— having greatly decreased capacity to accumulate the membrane potential-reporting dye Mitotracker Red (figure 5); and

— showing decreased ROS levels as measured by the ROS indicator H2DCF-DA (figure 6).

These are central predictions of the hypothesis presented in figure 2: oocyte mitochondria serve a primary function as genetically repressed, quiescent, inactive templates for faithful transmission of mitochondrial DNA into the next generation. It is predicted that, in other animal species, oocyte mitochondria do not accumulate mutations associated with ageing and its allied degenerative diseases. Decreased mitochondrial DNA transcription in oocytes has been noted in other animal species [91], including mammals [92–94].

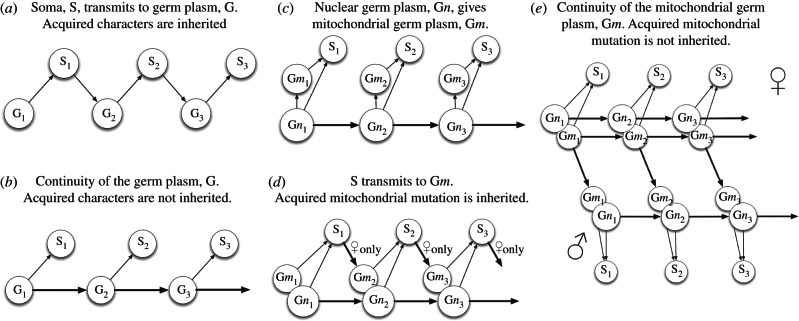

11. Implications: the Weismann barrier and continuity of the mitochondrial germ-plasm

Contrary to a common assumption of the heritability of characters acquired by an individual within its lifetime, Weismann proposed, in the nineteenth century, a doctrine, or ‘dogma’, of the continuity of the germ-plasm [95]. In schematic outline, figure 7b depicts Weismann's hypothesis and figure 7a the earlier, contrary view, propounded by Lamarck, in which the germ line by some means encapsulates and transmits characteristics of the soma, including those acquired from physiological responses to environmental challenges [17,99]. Today Weismann's hypothesis can be restated in genetic terms: the phenotype arises from the genotype while the genotype arises from a pre-existing genotype. The phenotype is the outward expression of the genotype; it serves as a vehicle for environmental interactions that determine whether the genotype survives to be passed on to the next generation. Mendelian genetics and the Darwin–Wallace theory of evolution by natural selection are together broadly consistent with Weismann and count against Lamarck. The ‘Central Dogma’ of molecular biology [96], the one-way flow of information from nucleotide sequence to amino acid sequence, lays a foundation for the existence of the ‘Weismann barrier’, prohibiting transfer of genetic information from protein to nucleotide sequence, from phenotype to genotype, or, in Weismannian terminology, from soma to germ-plasm. In this context, mitochondrial DNA has been viewed in different ways, outlined in figure 7c,d. Figure 7d may represent a current consensus. In figure 7, mitochondrial mutation is counted as an acquired character because it occurs within an individual lifetime, may have immediate effects, and varies in frequency in response to physiological and environmental change.

Figure 7.

Weismann's concept of the continuity of the germ-plasm [95] extended to mitochondria. G is Germ-plasm; the hereditary material. S is soma; the phenotype. Today, following Crick [96], we regard DNA as the molecular basis of G, and protein, broadly, as the molecular foundation of S. Arrows indicate direction of flow of information. Subscripts indicate generation number. Thick arrows indicate transmission of genetic information, including mutation. (a) The pre-Weismann view, associated with Lamarck, that S derives from G, and G derives from S. By this view, acquired characters are inherited. (b) Weismann's hypothesis. S derives from G, and G derives only from previous G. Selection acts on S, determining only whether G is passed on to the next generation. Information does not flow from S to G: this restriction can be termed the Weismann Barrier. (c) Autogeny of cells, including the mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA, from a single genome [97]; mitochondria are effectively part of S in (b). (d) A conventional modern view of combined mitochondrial (m) and nuclear (n) inheritance. The Weismann barrier is broken because acquired characters of mitochondria, for example, ROS-induced mutation, convey heritable information, in the mitochondrial genome, from S to G, and, for some reason, only in females. If mitochondria are the cause of ageing, then ageing should be inherited, and accumulate in successive generations [98]. (e) Mitochondrial division of labour between male and female (see figure 2) preserves the Weismann barrier for mitochondrial as well as nuclear inheritance. ♀, Female: mitochondrial G and nuclear G pass directly between generations. S determines only whether G transmits at all, and has no informational input into mitochondrial DNA. ♂, Male: mitochondrial G exists only to contribute to S, and is never a genetic template. Instead, mitochondrial G is maternally inherited in the cytoplasm of oocytes, where it is carried by quiescent mitochondria and thus transmitted independently of S.

The hypothesis in figure 2 and supported by evidence presented here (figures 3–6) proposes that Weismann's rule applies equally to mitochondrial inheritance, as outlined in figure 7e. In this view, mitochondrial energy transduction is adaptable and physiologically responsive to environmental change, while the continuity of mitochondrial DNA is secured by a separate and self-contained life cycle of template mitochondria, themselves unexposed directly, and as a matter of course, to physiological constraints that have effects on mitochondrial DNA sequence. If the hypothesis depicted in figure 2 is correct, then there is no need to postulate the existence of a process for distillation of mitochondrial phenotype into genotype, or for ‘purifying’ selection of mitochondrial that are, by some means, deemed fit for transmission from among a heteroplasmic population [100,101]. This is not to forbid the concepts of a bottleneck in oogenesis [102] or of mito-nuclear co-adaptation [103,104]—clearly the chimeric nature of key respiratory chain complexes (figure 1) will mean that different combinations of nuclear genes can be more compatible, or less, with safe and efficient mitochondrial energy transduction. Therefore, natural selection will act on the consequences of favourable or unfavourable combinations of nuclear with mitochondrial genes. The hypothesis in figure 2, however, removes the need to suppose that mito-nuclear interactions act with foresight of phenotypic consequences by anticipating the selective advantage of co-location of any specific mitochondrial DNA sequence with the respiratory apparatus that it partly encodes.

There are occasional variants from the maternal mode of mitochondrial inheritance. For example, in the mussel, Mytilus, there is biparental mitochondrial inheritance by sons, while daughters acquire mitochondria by uniparental, maternal inheritance alone [105]. More generally, the Weismann barrier applied to mitochondrial inheritance (figure 7e) forbids reversion of energy-transducing mitochondria into quiescent, genetic templates. We intend to search for this reversion as a stringent test, and potential disproof, of the hypothesis in figure 2. Until there is evidence to the contrary, we propose that female germ lines maintain, carry and transmit quiescent mitochondria as the cytoplasmic genetic templates from which all other mitochondria ultimately derive.

Acknowledgements

We thank C. A. Allen, B. Curran, T. FitzGeorge-Balfour, A. G. Hirst, R. G. Hughes, I. M. Ibrahim, F. Missirlis, M. Schwarzlander and B. Thake for discussion. We thank W. F. Martin for discussion and comments on the manuscript. Research supported by Leverhulme Trust research grant F/07 476/AQ (JFA) and by NERC research grant NE/G005516/1 (CHL).

Appendix. Material and methods

A.1. Jellyfish

Live male and female medusae were collected from Horsea Lake, Hampshire, UK on 28 August 2012 and 12 November 2012. Fresh tissue samples were taken from live specimens that had been maintained for up to 7 days in aerated artificial seawater diluted with distilled water to give a final salinity of 25, corresponding to the original brackish lake water.

A.2. RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from dissected A. aurita tissues was isolated using TRI reagent (Ambion), treated with DNase I (New England Biolabs) for 10 min at 37 °C and re-purified using Pure LinkTM RNA Mini Kit (Ambion), all according to the manufacturers’ instructions. A Chromo4 real-time detector (Bio-Rad), and Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR Green qRT-PCR (Agilent Technologies) were used for the reactions. All mitochondrial messenger RNA quantities were normalized against the nuclear gene α-tubulin. A second normalization was done using oral arms from both sexes as the reference. Primers used in this study were: nad1-F: 5′-GGAGTGGTTTGGGACAGTCA-3′, nad1-R: 5′-TCGAGGAAAGGGCCAAATGT-3′, cob-F: 5′-AACATGGGCAGCACCTAGTC-3′, cob-R: 5′-ACTTGGTTTCAGCTGTTCCCT-3′, cox1-F: 5′-ATGGTGGGAACTGCCTTCAG-3′, cox1-R: 5′-TTGATCGTCCCCCAACATGG-3′, α-tubulin-F: 5′-CAGCACCCCAAATCTCCACT-3′ and α-tubulin-R: 5′-ACCATGAAAGCGCAGTCAGA-3′. Three technical replicates for each biological replicate were averaged at the beginning, and three biological replicates were used to generate the error bars. C(t) values were analysed using qBase PLUS2 software (Biogazelle).

A.3. Transmission electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy, specimens were fixed overnight in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) supplemented with 0.14 M NaCl and post-fixed in 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) for 1.5 hours. Samples were then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, equilibrated with propylene oxide before infiltration with TAAB SPURR resin and polymerized at 70 °C for 24 h. Ultrathin sections (70–90 nm) were prepared using a Reichert-Jung Ultracut E ultramicrotome, mounted on 150 mesh copper grids, contrasted using uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined on an FEI Tecnai 12 transmission microscope operated at 120 kV. Images were acquired with an AMT 16000M digital camera. Stereological analysis was carried out as described in [106]. Thirty mitochondria from each group (bell muscle, oocyte and sperm) were used for the analysis. The combined point counting grid used for this study was composed of two sets of points of different densities on the same grid; nine fine points per coarse point. The volume of reference (mitochondria) was estimated by counting the number of coarse points that hit the reference space and multiplied by nine. The volume of the particular phase (cristae) was estimated by counting the number of fine and coarse points that hit the cristae. Student's t-test analysis was performed to determine the statistical significance.

A.4. Confocal microscopy

For mitochondrial membrane potential analysis, freshly dissected tissues of A. aurita were equilibrated for approximately 30 min at room temperature in solutions of Mitotracker Red FM (Life Technologies) or Mitotracker Green FM (Life Technologies) dissolved in PBS to give a final concentration of 500 nM. Three washes in pure PBS were used to remove the probe excess. For ROS detection, we followed the method described in [90] with minor modifications. Freshly dissected tissues were equilibrated in 10 µM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) solution, also containing DAPI (Sigma) (1 µM final concentration) in room temperature PBS for 30 min, followed by three PBS washes. Microscopy was performed using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope with an 8-bit camera (Leica Microsystems). Excitation and emission wavelengths were selected for the different fluorescent dyes as follows: DAPI: 350/450 to 480 nm, H2DCF-DA: 488/520 to 550 nm, Mitotracker Green: 488/500 to 530 nm, and Mitotracker Red: 581/620 to 650 nm. Imaging was performed with a 63× lens, and laser output was kept under 15% of maximal power. Leica LAS AF software was used to acquire and analyse the images.

References

- 1.Mitchell P. 1961. Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature 191, 144–148 10.1038/191144a0 (doi:10.1038/191144a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roodyn DB, Wilkie D. 1968. The biogenesis of mitochondria. London: Methuen [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haslbrunner E, Tuppy H, Schatz G. 1964. Deoxyribonucleic acid associated with yeast mitochondria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 15, 127–132 10.1016/0006-291X(64)90311-0 (doi:10.1016/0006-291X(64)90311-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horner DS, Hirt RP, Kilvington S, Lloyd D, Embley TM. 1996. Molecular data suggest an early acquisition of the mitochondrion endosymbiont. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 263, 1053–1059 10.1098/rspb.1996.0155 (doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0155) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin W, Müller M. 2007. Origin of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang D, Oyaizu Y, Oyaizu H, Olsen GJ, Woese CR. 1985. Mitochondrial origins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 82, 4443–4447 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4443 (doi:10.1073/pnas.82.13.4443) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sagan L. 1967. On the origin of mitosing cells. J. Theor. Biol. 14, 255–274 10.1016/0022-5193(67)90079-3 (doi:10.1016/0022-5193(67)90079-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nass MM, Nass S. 1963. Intramitochondrial fibers with DNA characteristics. I. Fixation and electron staining reactions. J. Cell Biol. 19, 593–611 10.1083/jcb.19.3.593 (doi:10.1083/jcb.19.3.593) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luck DJL, Reich E. 1964. DNA in mitochondria of Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 52, 931–938 10.1073/pnas.52.4.931 (doi:10.1073/pnas.52.4.931) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson S, et al. 1981. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature 290, 457–465 10.1038/290457a0 (doi:10.1038/290457a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pesole G, Allen JF, Lane N, Martin W, Rand DM, Schatz G, Saccone C. 2012. The neglected genome. EMBO Rep. 13, 473–474 10.1038/embor.2012.57 (doi:10.1038/embor.2012.57) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claros MG, Perea J, Shu Y, Samatey FA, Popot JL, Jacq C. 1995. Limitations to in vivo import of hydrophobic proteins into yeast mitochondria: the case of a cytoplasmically synthesized apocytochrome b. Eur. J. Biochem. 228, 762–771 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0762m.x (doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0762m.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koehler CM, Merchant S, Schatz G. 1999. How membrane proteins travel across the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 428–432 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01462-0 (doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01462-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen JF. 2003. The function of genomes in bioenergetic organelles. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 358, 19–38 10.1098/rstb.2002.1191 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1191) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camus M, Clancy DJ, Dowling DK. 2012. Mitochondria, maternal inheritance, and male aging. Curr. Biol. 22, 1–5 10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.009 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.12.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace DC. 2007. Why do we still have a maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA? Insights from evolutionary medicine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 781–821 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.081205.150955 (doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.081205.150955) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitehouse HLK. 1969. Towards an understanding of the mechanism of heredity, 2nd edn London: Edward Arnold (Publishers) Ltd [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen JF, de Paula WB, Puthiyaveetil S, Nield J. 2011. A structural phylogenetic map for chloroplast photosynthesis. Trends Plant. Sci. 16, 645–655 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.004 (doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen JF. 1993. Control of gene-expression by redox potential and the requirement for chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes. J. Theor. Biol. 165, 609–631 10.1006/jtbi.1993.1210 (doi:10.1006/jtbi.1993.1210) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.León-Avila G, Tovar J. 2004. Mitosomes of Entamoeba histolytica are abundant mitochondrion-related remnant organelles that lack a detectable organellar genome. Microbiology 150, 1245–1250 10.1099/mic.0.26923-0 (doi:10.1099/mic.0.26923-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tovar J, Fischer A, Clark CG. 1999. The mitosome, a novel organelle related to mitochondria in the amitochondrial parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 1013–1021 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01414.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01414.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Der Giezen M. 2009. Hydrogenosomes and mitosomes: conservation and evolution of functions. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 56, 221–231 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2009.00407.x (doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2009.00407.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams BAP, Hirt RP, Lucocq JM, Embley TM. 2002. A mitochondrial remnant in the microsporidian Trachipleistophora hominis. Nature 418, 865–869 10.1038/nature00949 (doi:10.1038/nature00949) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen JF. 2003. Why chloroplasts and mitochondria contain genomes. Comp. Funct. Genomics 4, 31–36 10.1002/cfg.245 (doi:10.1002/cfg.245) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daley DO, Clifton R, Whelan J. 2002. Intracellular gene transfer: reduced hydrophobicity facilitates gene transfer for subunit 2 of cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10 510–10 515 10.1073/pnas.122354399 (doi:10.1073/pnas.122354399) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin W, Hoffmeister M, Rotte C, Henze K. 2001. An overview of endosymbiotic models for the origins of eukaryotes, their ATP-producing organelles (mitochondria and hydrogenosomes), and their heterotrophic lifestyle. Biol. Chem. 382, 1521–1539 10.1515/BC.2001.187 (10.1515/BC.2001.187) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Heijne G. 1986. Why mitochondria need a genome. FEBS Lett. 198, 1–4 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81172-3 (doi:10.1016/0014-5793(86)81172-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Race HL, Herrmann RG, Martin W. 1999. Why have organelles retained genomes? Trends Genet. 15, 364–370 10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01766-7 (doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01766-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barbrook AC, Howe CJ, Purton S. 2006. Why are plastid genomes retained in non-photosynthetic organisms? Trends Plant Sci. 11, 101–108 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.12.004 (doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2005.12.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfannschmidt T, Nilsson A, Allen JF. 1999. Photosynthetic control of chloroplast gene expression. Nature 397, 625–628 10.1038/17624 (doi:10.1038/17624) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puthiyaveetil S, Ibrahim IM, Jelicic B, Tomasic A, Fulgosi H, Allen JF. 2010. Transcriptional control of photosynthesis genes: the evolutionarily conserved regulatory mechanism in plastid genome function. Genome Biol. Evol. 2, 888–896 10.1093/evq073 (doi:10.1093/evq073) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen CA, Håkansson G, Allen JF. 1995. Redox conditions specify the proteins synthesized by isolated- chloroplasts and mitochondria. Redox Rep. 1, 119–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Paula WBM, Allen JF, van der Giezen M. 2012. Mitochondria, hydrogenosomes and mitosomes in relation to the CoRR hypothesis for genome function and evolution. In Organelle genetics (ed. Bullerwell CE.), pp. 105–119 Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puthiyaveetil S, et al. 2008. The ancestral symbiont sensor kinase CSK links photosynthesis with gene expression in chloroplasts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10 061–10 066 10.1073/pnas.0803928105 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0803928105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puthiyaveetil S, Ibrahim IM, Allen JF. 2013. Evolutionary rewiring: a modified prokaryotic gene regulatory pathway in chloroplasts. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 20120260. 10.1098/rstb20120260 (doi:10.1098/rstb20120260). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen JF, Raven JA. 1996. Free-radical-induced mutation vs redox regulation: costs and benefits of genes in organelles. J. Mol. Evol. 42, 482–492 10.1007/BF02352278 (doi:10.1007/BF02352278) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. 1979. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol. Rev. 59, 527–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. 2003. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36 027–36 031 10.1074/jbc.M304854200 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M304854200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohnishi ST, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Ohta K, Yoshikawa S, Ohnishi T. 2010. New insights into the superoxide generation sites in bovine heart NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) The significance of protein-associated ubiquinone and the dynamic shifting of generation sites between semiflavin and semiquinone radicals. Bba-Bioenergetics 1797, 1901–1909 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.05.012 (doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.05.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kussmaul L, Hirst J. 2006. The mechanism of superoxide production by NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) from bovine heart mitochondria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 7607–7612 10.1073/pnas.0510977103 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0510977103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCord JM, Fridovich I. 1969. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 244, 6049–6055 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, et al. 1995. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat. Genet. 11, 376–381 10.1038/ng1295-376 (doi:10.1038/ng1295-376) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melov S, Schneider JA, Day BJ, Hinerfeld D, Coskun P, Mirra SS, Crapo JD, Wallace DC. 1998. A novel neurological phenotype in mice lacking mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat. Genet. 18, 159–163 10.1038/ng0298-159 (doi:10.1038/ng0298-159) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taufer M, Peres A, de Andrade VM, de Oliveira G, Sa G, do Canto ME, dos Santos AR, Bauer ME, da Cruz IB. 2005. Is the Val16Ala manganese superoxide dismutase polymorphism associated with the aging process? J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 60, 432–438 10.1093/gerona/60.4.432 (doi:10.1093/gerona/60.4.432) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Treiber N, et al. 2011. Accelerated aging phenotype in mice with conditional deficiency for mitochondrial superoxide dismutase in the connective tissue. Aging Cell 10, 239–254 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00658.x (doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00658.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pessayre D, Berson A, Fromenty B, Mansouri A. 2001. Mitochondria in steatohepatitis. Semin. Liver Dis. 21, 57–69 10.1055/s-2001-12929 (doi:10.1055/s-2001-12929) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. 1997. Protein oxidation in aging, disease, and oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20 313–20 316 10.1074/jbc.272.1.20 (doi:10.1074/jbc.272.1.20) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. 2003. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 17, 1195–1214 10.1096/fj.02-0752rev (doi:10.1096/fj.02-0752rev) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. 1993. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 7915–7922 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915 (doi:10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. 1995. Mitochondrial decay in aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1271, 165–170 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00024-X (doi:10.1016/0925-4439(95)00024-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harman D. 1972. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 20, 145–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harman D. 1992. Free radical theory of aging. Mutat. Res. 275, 257–266 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90030-S (doi:10.1016/0921-8734(92)90030-S) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. 1994. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10 771–10 778 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771 (doi:10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petros JA, et al. 2005. mtDNA mutations increase tumorigenicity in prostate cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 719–724 10.1073/pnas.0408894102 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0408894102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Afanas'ev I. 2010. Signaling and damaging functions of free radicals in aging–free radical theory, hormesis, and TOR. Aging Dis. 1, 75–88 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobs HT. 2003. The mitochondrial theory of aging: dead or alive? Aging Cell 2, 11–17 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00032.x (doi:10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00032.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park CB, Larsson NG. 2011. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. J. Cell Biol. 193, 809–818 10.1083/jcb.201010024 (doi:10.1083/jcb.201010024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kujoth GC, et al. 2005. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science 309, 481–484 10.1126/science.1112125 (doi:10.1126/science.1112125) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trifunovic A, et al. 2004. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 429, 417–423 10.1038/nature02517 (doi:10.1038/nature02517) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trifunovic A, et al. 2005. Somatic mtDNA mutations cause aging phenotypes without affecting reactive oxygen species production. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 17 993–17 998 10.1073/pnas.0508886102 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0508886102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasaki T, Unno K, Tahara S, Shimada A, Chiba Y, Hoshino M, Kaneko T. 2008. Age-related increase of superoxide generation in the brains of mammals and birds. Aging Cell 7, 459–469 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00394.x (doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00394.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mendoza-Nunez VM, Ruiz-Ramos M, Sanchez-Rodriguez MA, Retana-Ugalde R, Munoz-Sanchez JL. 2007. Aging-related oxidative stress in healthy humans. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 213, 261–268 10.1620/tjem.213.261 (doi:10.1620/tjem.213.261) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miyazawa M, Ishii T, Yasuda K, Noda S, Onouchi H, Hartman PS, Ishii N. 2009. The role of mitochondrial superoxide anion (O2−) on physiological aging in C57BL/6J mice. J. Radiat. Res. 50, 73–83 10.1269/jrr.08097 (doi:10.1269/jrr.08097) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lund DD, Chu Y, Miller JD, Heistad DD. 2009. Protective effect of extracellular superoxide dismutase on endothelial function during aging. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 296, H1920–H1925 10.1152/ajpheart.01342.2008 (doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01342.2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donato AJ, Eskurza I, Silver AE, Levy AS, Pierce GL, Gates PE, Seals DR. 2007. Direct evidence of endothelial oxidative stress with aging in humans: relation to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation and upregulation of nuclear factor-κB. Circ. Res. 100, 1659–1666 10.1161/01.RES.0000269183.13937.e8 (doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000269183.13937.e8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choksi KB, Roberts LJ, 2nd, DeFord JH, Rabek JP, Papaconstantinou J. 2007. Lower levels of F2-isoprostanes in serum and livers of long-lived Ames dwarf mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 364, 761–764 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.100 (doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jacobson A, Yan C, Gao Q, Rincon-Skinner T, Rivera A, Edwards J, Huang A, Kaley G, Sun D. 2007. Aging enhances pressure-induced arterial superoxide formation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H1344–H1350 10.1152/ajpheart.00413.2007 (doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00413.2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lener B, Koziel R, Pircher H, Hutter E, Greussing R, Herndler-Brandstetter D, Hermann M, Unterluggauer H, Jansen-Durr P. 2009. The NADPH oxidase Nox4 restricts the replicative lifespan of human endothelial cells. Biochem. J. 423, 363–374 10.1042/BJ20090666 (doi:10.1042/BJ20090666) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rodriguez-Manas L, et al. 2009. Endothelial dysfunction in aged humans is related with oxidative stress and vascular inflammation. Aging Cell 8, 226–238 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00466.x (doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00466.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allen JF. 1996. Separate sexes and the mitochondrial theory of ageing. J. Theor. Biol. 180, 135–140 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0089 (doi:10.1006/jtbi.1996.0089) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allen CA, van der Giezen M, Allen JF. 2007. Origin, function and transmission of mitochondria. In Origins of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes (eds Martin W, Muller M.), pp. 39–56 Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 72.Al Rawi S, Louvet-Vallee S, Djeddi A, Sachse M, Culetto E, Hajjar C, Boyd L, Legouis R, Galy V. 2011. Postfertilization autophagy of sperm organelles prevents paternal mitochondrial DNA transmission. Science 334, 1144–1147 10.1126/science.1211878 (doi:10.1126/science.1211878) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deluca SZ, O'Farrell PH. 2013. Barriers to male transmission of mitochondrial DNA in sperm development. Dev. Cell 22, 660–668 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.021 (doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sato M, Sato K. 2011. Degradation of paternal mitochondria by fertilization-triggered autophagy in C. elegans embryos. Science 334, 1141–1144 10.1126/science.1210333 (doi:10.1126/science.1210333) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Collins AG, Schuchert P, Marques AC, Jankowski T, Medina M, Schierwater B. 2006. Medusozoan phylogeny and character evolution clarified by new large and small subunit rDNA data and an assessment of the utility of phylogenetic mixture models. Syst. Biol. 55, 97–115 10.1080/10635150500433615 (doi:10.1080/10635150500433615) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cartwright P, Halgedahl SL, Hendricks JR, Jarrard RD, Marques AC, Collins AG, Lieberman BS. 2007. Exceptionally preserved jellyfishes from the middle Cambrian. PLoS One 2, e1121. 10.3410/f.1093897.548834 (doi:10.3410/f.1093897.548834) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ojimi MC, Hidaka M. 2010. Comparison of telomere length among different life cycle stages of the jellyfish Cassiopea andromeda. Mar. Biol. 157, 2279–2287 10.1007/s00227-010-1495-4 (doi:10.1007/s00227-010-1495-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Butterfield NJ. 1997. Plankton ecology and the Proterozoic–Phanerozoic transition. Paleobiology 23, 247–262 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Condon RH, et al. 2012. Questioning the rise of gelatinous zooplankton in the world's oceans. Bioscience 62, 160–169 10.1525/bio.2012.62.2.9 (doi:10.1525/bio.2012.62.2.9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Butterfield NJ. 2000. Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen, n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes. Paleobiology 26, 386–404 (doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Extavour CG, Akam M. 2003. Mechanisms of germ cell specification across the metazoans: epigenesis and preformation. Development 130, 5869–5884 10.1242/dev.00804 (doi:10.1242/dev.00804) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Morandini AC, Da Silveira FL. 2001. Sexual reproduction of Nausithoe aurea (Scyphozoa, Coronatae) gametogenesis, egg release, embryonic development, and gastrulation. Sci. Mar. 65, 139–149 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dawson MN, Martin LE. 2001. Geographic variation and ecological adaptation in Aurelia (Scyphozoa, Semaeostomeae): some implications from molecular phylogenetics. Hydrobiologia 451, 259–273 10.1023/A:1011869215330 (doi:10.1023/A:1011869215330) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lucas CH. 2001. Reproduction and life history strategies of the common jellyfish, Aurelia aurita, in relation to its ambient environment. Hydrobiologia 451, 229–246 10.1023/A:1011836326717 (doi:10.1023/A:1011836326717) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shao ZY, Graf S, Chaga OY, Lavrov DV. 2006. Mitochondrial genome of the moon jelly Aurelia aurita (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa): a linear DNA molecule encoding a putative DNA-dependent DNA polymerase. Gene 381, 92–101 10.1016/j.gene.2006.06.021 (doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.06.021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hirst AG, Lucas CH. 1998. Salinity influences body weight quantification in the scyphomedusa Aurelia aurita: important implications for body weight determination in gelatinous zooplankton. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 165, 259–269 10.3354/meps165259 (doi:10.3354/meps165259) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mitchell P. 1979. Keilins respiratory-chain concept and its chemiosmotic consequences. Science 206, 1148–1159 10.1126/science.388618 (doi:10.1126/science.388618) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rich P. 2003. The cost of living. Nature 421, 583–583 10.1038/421583a (doi:10.1038/421583a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pendergrass W, Wolf N, Poot M. 2004. Efficacy of MitoTracker Green and CMXrosamine to measure changes in mitochondrial membrane potentials in living cells and tissues. Cytometry A 61, 162–169 10.1002/cyto.a.20033 (doi:10.1002/cyto.a.20033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Owusu-Ansah E, Yavari A, Banerjee U. 2008. A protocol for in vivo detection of reactive oxygen species Protocol Exchange 10.1038/nprot.2008.23 (doi:10.1038/nprot.2008.23) [DOI]

- 91.de Paula WBM, Agip A-N, Missirlis F, Ashworth R, Vizcay-Barrena G, Lucas C, Allen JF. Submitted. Mitochondrial function in the origin of the female germ line.

- 92.Hsieh RH, Au HK, Yeh TS, Chang SJ, Cheng YF, Tzeng CR. 2004. Decreased expression of mitochondrial genes in human unfertilized oocytes and arrested embryos. Fertil. Steril. 81(Suppl. 1), 912–918 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.11.013 (doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.11.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Santos TA, Shourbagy SE, John JCS. 2006. Mitochondrial content reflects oocyte variability and fertilization outcome. Fertil. Steril. 85, 584–591 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.017 (doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wilding M, Dale B, Marino M, diMatteo L, Alviggi C, Pisaturo ML, Lombardi L, dePlacido G. 2001. Mitochondrial aggregation patterns and activity in human oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Hum. Reprod. 16, 909–917 10.1093/humrep/16.5.909 (doi:10.1093/humrep/16.5.909) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weismann A. 1889. Essays upon heredity, vols 1 and 2. Oxford: The Clarendon Press [Google Scholar]

- 96.Crick F. 1970. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 227, 561–563 10.1038/227561a0 (doi:10.1038/227561a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bogorad L. 1975. Evolution of organelles and eukaryotic genomes. Science 188, 891–898 10.1126/science.1138359 (doi:10.1126/science.1138359) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Allen JF, Allen CA. 1999. A mitochondrial model for premature ageing of somatically cloned mammals. IUBMB Life 48, 369–372 10.1080/713803544 (doi:10.1080/713803544) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maynard Smith J. 1966. The theory of evolution, 2nd edn London: Penguin Books [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stewart JB, Freyer C, Elson JL, Wredenberg A, Cansu Z, Trifunovic A, Larsson NG. 2008. Strong purifying selection in transmission of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. PLoS Biol. 6, e10. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060010 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fan W, et al. 2008. A mouse model of mitochondrial disease reveals germline selection against severe mtDNA mutations. Science 319, 958–962 10.1126/science.1147786 (doi:10.1126/science.1147786) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reynier P, Chretien MF, Savagner F, Larcher G, Rohmer V, Barriere P, Malthiery Y. 1998. Long PCR analysis of human gamete mtDNA suggests defective mitochondrial maintenance in spermatozoa and supports the bottleneck theory for oocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 252, 373–377 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9651 (doi:10.1006/bbrc.1998.9651) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hadjivasiliou Z, Pomiankowski A, Seymour RM, Lane N. 2012. Selection for mitonuclear co-adaptation could favour the evolution of two sexes. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 1865–1872 10.1098/rspb.2011.1871 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.1871) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lane N. 2011. Mitonuclear match: Optimizing fitness and fertility over generations drives ageing within generations. Bioessays 33, 860–869 10.1002/bies.201100051 (doi:10.1002/bies.201100051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zouros E, Ball AO, Saavedra C, Freeman KR. 1994. An unusual type of mitochondrial-DNA inheritance in the blue mussel mytilus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 7463–7467 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7463 (doi:10.1073/pnas.91.16.7463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Howard CV, Reed MG. 2010. Unbiased stereology: three-dimensional measurement in microscopy, 2nd edn Liverpool: QTP Publications [Google Scholar]