Abstract

Background

Former prison inmates are at risk for HIV and Hepatitis C (HCV). This study was designed to understand how former inmates perceived their risk of HIV and HCV after release from prison, the behaviors and environmental factors that put patients at risk for new infection and the barriers to accessing health care.

Methods

Qualitative study utilizing individual, face-to-face, semi-structured interviews exploring participants’ perceptions and behaviors putting them at risk for HIV and HCV and barriers to engaging in regular medical care after release. Interview transcripts were coded and analyzed utilizing a team-based general inductive approach.

Results

Participants were racially and ethnically diverse and consisted of 20 men and 9 women with an age range of 22–57 years who were interviewed within the first two months after their release from prison to the Denver, Colorado community. Four major themes emerged: 1) risk factors including unprotected sex, transactional sex, and drug use were prevalent in the post-release period; 2) engagement in risky behavior occurred disproportionately in the first few days after release; 3) former inmates had educational needs about HIV and HCV; and 4) former inmates faced major challenges in accessing health care and medications.

Conclusions

Risk factors for HIV and HCV were prevalent among former inmates immediately after release. Prevention efforts should focus on education, promotion of safe sex and needle practices, substance abuse treatment, and drug- free transitional housing. Improved coordination between correctional staff, parole officers and community health care providers may improve continuity of care.

INTRODUCTION

The United States has a growing correctional population [1] and 95% of prisoners will be released. [2] The transition from prison to the community has significant health consequences. International studies have shown a high risk of death after release from prison. [3–13] In the first two weeks after release, former Washington State prisoners had a mortality rate 12.7 times higher than the general population. [14] Drug overdoses were among the leading causes of death during this “reentry” period. Former inmates with past drug use are at high risk for the transmission and acquisition of HIV and other blood-borne viruses such as Hepatitis C virus (HCV) due to drug use and other risk behaviors. During reintegration into the community, former inmates must obtain health care, housing, and employment, establish social support, reinstate health benefits, and reestablish medical care. [15–18] Difficulties with navigating this complex system may lead to failure to access medical care for HIV and HCV and prevent former inmates from receiving testing and treatment.

Through open-ended interviews with former inmates, we sought to understand the experiences of former inmates during the vulnerable reentry period which put them at risk for HIV or HCV transmission, acquisition, progression and failure to link to care. Few studies have examined the health perceptions and risks and the health-care seeking experiences among former inmates as they pertain to HIV and HCV, nor have they focused on the high-risk immediate post-release period. Thus, this study was designed to determine 1) how former inmates perceived their risk of HIV and HCV after release from prison; 2) the behaviors and environmental factors which put patients at risk for new HIV or HCV infection in the transitional period, and 3) the barriers which prevent former inmates from accessing medical services necessary for preventive care, testing and treatment.

METHODS

We conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews face-to-face with former inmates aged 18 and older recruited within two months of release. Interviews were scheduled as soon after recruitment as possible. Additionally, we met with three participants from whom data were originally obtained to clarify key points and assess validity of our interpretations (member checking). Study participants were recruited from a community health center, an urgent care center and addiction treatment centers in Denver, Colorado, with subsequent snowball sampling. [19] Eligibility criteria included ability to speak English and ability to consent to the study procedures. Former inmates whose release was from jail were excluded. Jails are locally-operated short-term detention centers for individuals not yet convicted or with short sentences, whereas prisons are run by state or federal government for sentences longer than one year. [20] Most former inmates in Colorado are released without health insurance but are eligible for the Colorado Indigent Care Plan (CICP), a program that distributes federal and state funds to compensate health care providers. [21] Individual providers and facilities may coordinate discharge planning for individual patients but we are not aware of a currently operational statewide release program for HIV-infected offenders in Colorado.

The interview guide was developed to address a broad set of aims related to the health of former inmates. Interview questions were refined with input from qualitative and health services researchers, interviewers, and former inmates enrolled in initial interviews. Interview questions addressed behaviors placing participants at risk for acquiring or transmitting HIV or HCV as well as access to medical care (see Table 1). Interviewers were trained in interviewing criminal justice populations, qualitative methods, and individual behaviors likely to increase rapport and participant comfort level. Interviews were conducted from March through June, 2009. Team members from medicine, public health, social work, and psychology met regularly to debrief the interviewers. Member checking was performed by study authors through October, 2010. The one-on-one interview format was selected to encourage participants to express their experiences and preserve confidentiality. [22, 23] Participants were provided $25 for initial interviews and $25 for member checking. Interviews were digitally recorded in private, uploaded to a secure drive and professionally transcribed.

Table 1.

Examples of Open-Ended Questions Used During Interviews

| 1. | After being released from prison, have you used an illegal drugs or prescription drugs you got on the street? |

| 2. | After being released from prison, have you had any alcoholic drinks? |

| 3. | Thinking back to those first two weeks after you were released, what do you think was the biggest threat to your safety? |

| 4. | Thinking back to the first two weeks after release, what do you think was the biggest threat to your health? |

| 5. | Are there certain situations you have tried to avoid since your release because of their possible effect on your safety? |

| 6. | Are there certain situations you have tried to avoid since your release because of their possible effect on your health? |

| 7. | Do you feel safe where you live and other places you have to go? |

| 8. | What kinds of things do you think people who are released from prison do to improve their health and well-being in the first two weeks after release? |

| 9. | How do you think being in prison affected your health? |

| 10. | How do you think being released from prison affected your health? |

| 11. | How might you have made your health worse after your release? |

| 12. | How might you have put yourself or others at risk for hepatitis C or HIV after your release? |

| 13. | Have you had unprotected sex since your release? |

| 14. | Since your release, how important has it been to get health care? |

| 15. | Did you have any trouble getting health care after release? |

| 16. | Have you tried to get health insurance, Medicaid or Medicare since your release? |

| 17. | Are you currently supposed to be taking any prescription medications for medical or mental health conditions? |

| 18. | Have you been involved in any programs to help inmates who are going to be released? |

Interview transcripts and a demographic survey were our primary data source. Transcript files were entered into Atlas-tiR qualitative data analysis software. We utilized an inductive, team-based approach to explore HIV and HCV-related patterns and themes within the interview data. [24–26] Two team members coded transcripts and met regularly to resolve coding differences and to create the final codebook. Other team members reviewed a subset of transcripts and met with the primary coders to discuss emerging themes and discrepancies. For this analysis, the investigators (JA, CN, IB) reviewed the transcripts, paying particular attention to segments of text related to HIV/HCV.

This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and we obtained a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

RESULTS

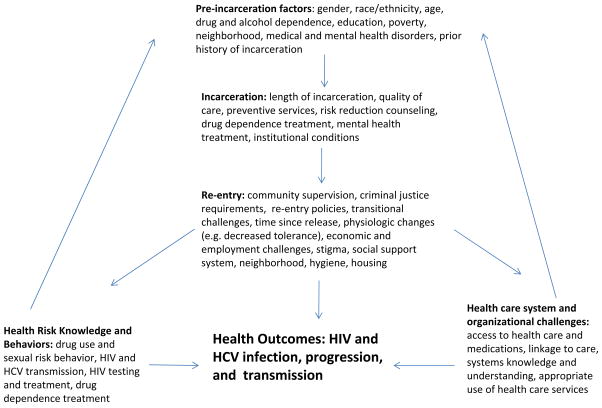

Participant characteristics are described in Table 2. We did not specifically ask about HIV, HCV or other medical or psychiatric diagnoses; however, seven participants disclosed they had HCV and one participant disclosed HIV infection. These numbers are likely an underestimate given that we only have this information for those participants who volunteered it. Based on analysis of interview transcripts, we created a conceptual model of the multiple factors impacting rates of HIV/HCV infection, progression, and transmission in former inmates (Figure 1). Four major themes had particular importance to our participants in the re-entry period.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics (n=29)

| Age in years, mean (range) | 39 (22–57) |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (69%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| African American | 11 (38%) |

| White | 5 (17%) |

| Latino | 10 (34%) |

| American Indian | 3 (10%) |

| Length of time since release, mean (range) | 42 days (5–82) |

| Source of referral to study, n (%) | |

| Another study participant | 5 (17%) |

| Shelter | 4 (14%) |

| Community health center | 3 (10%) |

| Residential treatment center | 3 (10%) |

| Friend/relative | 2 (7%) |

| Drug treatment center | 2 (7%) |

| Other | 3 (9%) |

| Unknown | 7 (24%) |

| Health insurance status, n (%) | |

| None | 16 (55%) |

| Medicaid | 1 (3%) |

| Medicaid pending | 1 (3%) |

| CICP* | 7 (24%) |

| CICP pending | 1 (3%) |

| Unknown | 3 (10%) |

CICP (Colorado Indigent Care Program)

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Factors Impacting HIV-related Health Outcomes

- Risk behaviors for acquiring or transmitting HIV and/or HCV infection were prevalent in the immediate post-release period. These risk behaviors included poly-substance use, unprotected sex, the exchange of sex for drugs or money, non-consensual sex reported by women, and limited availability of sterile injecting equipment. These risk behaviors were highly linked to drug and alcohol use. For instance, one 46 year old woman with multiple incarcerations described the relationship between release from prison, drinking alcohol and having unprotected sex:“…this is why like I am trying very hard not to drink or anything because I make stupid decisions…but in the past, yep. I got out [of prison], I drank and I had unprotected sex…”

A 28 year old mother, who had been incarcerated four times, described how the use of alcohol and marijuana led to other risky behaviors:

“It’s [alcohol] a gateway drug, you know? They start drinking, you meet people at the bar, people have dope, you’re already intoxicated…Most people start out with drinking, smoking pot and that leads to other things.”

This participant was enrolled in a criminal justice funded addiction treatment program, and when she reflected on her experiences after release from prison during member checks, she also related the fact that non-consensual sexual encounters led to potential exposure to HIV:

“How many times you were taken advantage of and you stuffed it away or how many times you were raped and didn’t tell anybody about it ‘cause you were scared… How many times you fell asleep and you just don’t know what happened”

Drug use was also a major contributor to risky behavior in the post-release period. Despite knowledge of the risks associated with sharing injecting equipment, the same 28 year old woman described the occurrence of risky needle use:

“If there is only one needle and there’s two of you, they’re going to share…When you’re in your addiction, you don’t care. You don’t think about the possibilities of what that person has, you just think about the high you’re going to get from using that needle.”

Several participants described risky behaviors associated with exchanging sex and drugs. Transactional sex was described as one method for quickly acquiring drugs in the immediate post-release period. One 43 year old man explained:

“[I’ve had] unprotected sex with these females that be out here [of prison] and it doesn’t take much to get one of them. All you have to do is give them a few dollars or some crack.”

One woman described her perception that recently released women turned to exchanging sex for money or drugs because they did not have housing or money after release.

“They got people they go to. They got tricks or sugar daddies, pimps that it’s easy for them to find.”

A 33 year old single mother of three children described the practice of exchanging sex in prison and how that related to risky behavior after release.

“There’s a lot of prostitution like even in prison… really a high rate of girls turn to sex with other women when they’re in prison… then they get out and they just keep using that behavior of getting drugs for sex.”

In probing further about sexual risk, a 45 year old male with two young children highlighted the theme of misogyny when he discussed exchanging sex for drugs:

“If they got girlfriends or wives or…I guess you can call them (laughing) hood rats…when a female starts doing any kind of drug like meth or speed…I mean meth or cocaine or anything, they get addicted like that.…so, they’ll do whatever they gotta do to get it.”

Finally, lack of access to condoms and sterile injection equipment amplified the risk of transmitting or acquiring HIV or HCV. One 47 year old male described his sexual encounters in the period after his release:

“When I got out, I did have intercourse…with a lady and I don’t know if she had it [HIV] or not. I: Did you use a condom? R: No. I didn’t have ‘em.”

Former inmates described the challenges in finding clean needles after relapsing to methamphetamine use after release:

“Stores won’t sell you needles if you’re not a diabetic and you look like a junky…if you go to a Walgreen’s at 3:00 in the morning to get a needle, they’re not going to sell you one ‘cause they know why you’re there… And then you would go use somebody else’s needle.”

In summary, former inmates commonly described risk behaviors for the spread of HIV/HCV in the immediate post-release period. Alcohol often instigated a spiral of escalating drug use and unsafe sexual practices. Despite the high rates of drug use and unprotected sex in the post-release period, former inmates did not use condoms or clean needles to reduce risk, mostly due to lack of immediate availability.

1. The second major theme was the immediacy with which former inmates engaged in risky behaviors after release from prison. Participants described feeling overwhelmed by the lack of structure and competing needs they faced after release. Most returned to chaotic environments where they were surrounded by drug use. The 28 year old woman interviewed while in substance abuse treatment described how the neighborhood to which one returns contributes to the immediate engagement in risky behavior:

“Any normal person that just got out doesn’t have anything but the clothes on their back and a week voucher in some [obscenity] hotel on the bad side of town, what are the odds for them to actually do something with that? There is none. There is like one percent that might make it out of there… They go back to what they knew before and so they fall back amid the old people, places and things and that’s where it [drug use and transactional sex] happens.”

Participants of both genders described an “as soon as I get out…” mentality that led to risky behavior in the first few days after release. Participants implied that this sense of urgency decreased with time after release. For instance, a young woman with four prior incarcerations described resuming drug use and sexual activity immediately after her release during a prior incarceration:

“I used [drugs] within the first two days…People that have been locked up for a long time, they just get out and pretty much want to have sex, you know?... you feel like you have to make up for all that lost time”

Both male and female participants described an urgency to engage in sexual activity after release from prison, which led to increased risk behaviors. A 43 year old male stated:

“The biggest threat to my safety probably would be going to put myself in a situation that I have done in the past, just to get with a female, just ’cause it’s been a while since I’ve had sex.”

Many of our interviews revealed the importance of masculine self-identity contributing to a sense of urgency to have sex after release:

“…if I find another piece of [obscenity], you know, I’m not dumb. I’m only human. I’m a man and then being out of prison, you know, being locked up that whole year and it’s pretty rough.”

In summary, we found that former inmates engaged in risky sexual and drug behavior in the immediate days after release, due in part to a sense a deprivation during incarceration, as well as returning to the same environments in which they were living prior to incarceration.

3. The third major theme was the factual errors and misconceptions about HIV/HCV transmission revealed by former inmates. When study participants were asked about how they might have put themselves at risk for HIV or HCV, one 22 year old male who was attempting to reconcile with his girlfriend and young son revealed misunderstanding the ability of birth control to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STI’s) and denial about the potential for infidelity by his partner:

“The only risk that I can think of would be intercourse with my girlfriend … it’s unprotected but she’s on birth control …from what she said she’s not been with anybody since I went away.”

A 24 year old male believed that transmission of HIV and HCV was related to basic hygiene:

“The DOC [Department of Corrections] putting me at risk by sending me to a [shelter] that people who do have Hepatitis C and the people ain’t clean and they’re not cleaning up after themselves, so that’s a risk for them, you know, for me.”

A 45 year old male correctly noted the transmission risk from drug use and sexual contact, but mistakenly believed HCV could be acquired from sharing water bottles:

“My understanding of the determining factors to being able to contract it [HCV or HIV] are sex which I haven’t had any of since I’ve been out in any shape or form, intravenous drug use and I don’t do that or…you know, blood transfusions. And Hep C possibly drinking after somebody and I try to drink from own water bottle.”

In summary, our interviews revealed common misunderstandings about how HIV and HCV are transmitted.

4. The fourth major theme was the common challenges faced in accessing health care and medications after release putting patients at risk for worsening health status and interruption in care. Participants commonly described long wait times to be screened for indigent care services. A 48 year old male with HCV described this process:

“I’ve spent quite a bit of time down there learning the ropes on what you have to do to get this free health care because you know how it’s free health care, but by golly you’re going to wait quite a long time and you gotta kind of know, you know, the ins and outs.”

Participants described difficulty obtaining needed medications after being released without them or with only a short-term supply. A 40 year old African American man with HIV revealed stopping his anti-retrovirals because he was concerned the side effects would prevent him from complying with parole requirements:

“They gave me a [30 day] supply of medication, but I’m not able to take the medication because the medication knock me out and I might not hear the page…If I don’t make these calls, that can be taken for escape for me not calling back…so I just don’t take my medication.”

At the same time, he readily acknowledged the risks associated with medication non- adherence:

“I: In the period of time after your release, what was the biggest threat to your health? R: Not taking my [HIV] meds.”

Other barriers related to obtaining health care in the immediate post-release time period ranged from lack of insurance, not knowing where and how to access care, and not being able to obtain needed medications. These factors were perceived by our participants to have a direct negative impact on health status after release.

DISCUSSION

These interviews illuminated the experiences of former inmates in the immediate post- release period and help inform interventions which could significantly impact HIV- and HCV-related morbidity and mortality during this vulnerable period. Risky behaviors such as unprotected and transactional sex, drug and alcohol abuse, and the use of non-sterile injection equipment were commonly described. Perhaps most striking was the immediacy in which former inmates were placing themselves at risk through these behaviors after release. Our interviews also revealed misconceptions about HIV and HCV risk among former inmates. Finally, many participants described the innumerable challenges faced when trying to access health care in the post-release period ranging from lack of insurance, not knowing how or where to access care, to an inability to obtain needed medications after release.

While high rates of STI’s and drug use have been documented in persons in the criminal justice system [27, 28], little is known about what strategies would be most effective in preventing the associated morbidity and mortality. Insight from these interviews may help target preventive efforts. The first few days and weeks post-release appear to be a particularly risky time. Therefore, efforts to prevent high risk activities should focus on this time period.

Specifically, preventive efforts should focus on the perceived need for sexual gratification immediately after release from prison. Former inmates are at high risk for STI’s in the post-release period due to multiple sexual partners and inconsistent condom use. [28] Safe sex counseling prior to release and providing condoms to prisoners as they are being released may decrease some of the risk associated with these encounters. Because of the high rates of drug use after release and the high mortality rates associated with overdoses [14] as well as the association of drug use with other risky behaviors, [29] substance abuse treatment is important in the post-release period. Efforts also need to focus on reducing transactional sexual activity as this represents a dangerous intersection of unsafe sex and drug practices.

Increased attention needs to be given to the environment in which former inmates are released. Our participants, many with histories of substance abuse, described being released without money, transportation, or stable housing which led many of them back to familiar surroundings with ubiquitous drug use. Programs focused on creating drug-free transitional environments may impact the health behaviors of this population. Provision of safe and sober housing may prevent individuals from resorting to transactions involving drugs and sex which were commonly described as a survival strategy by our participants.

Another important focus for prevention efforts is education aimed at increasing knowledge about HIV/HCV transmission. Some of the common misconceptions about risk could be remedied with health education in prisons and after release. Prison-based educational programs have been implemented in the past with significant impact on health knowledge and behavior. [30–33] Wide-spread adaptation of such programs in the context of other behavioral prevention strategies may have significant impact on risk behaviors.

Finally, facilitating the transfer of care from the correctional system to community health centers has the potential to significantly decrease risk behaviors and improve health outcomes. In Texas, only 20% of HIV positive former inmates were seen for HIV care within one month of release; within three months, only 28% had reestablished regular HIV care. [34] Our study participants had little support to navigate the logistical aspects of arranging care and accessing medications after release. An inability to access health care after release jeopardizes the health status of patients with HIV or HCV and impedes access to testing and counseling for individuals at risk. Increased coordination between health services and parole might facilitate this process.

This study has several limitations. Although the qualitative interview process allowed us to obtain candid responses and gain in-depth insight in the personal experiences of former prisoners, it limited the overall sample size. The sample size was likely too small to detect differences in the risk behaviors and educational needs between subjects infected with HIV and/or HCV compared to those who were not infected. Because our interviews were limited to Colorado, the findings may not be generalizable to all former inmates. However, we had a highly racially and ethnically diverse study population that included both men and women and our results were validated through member checking.

Our results suggest that former inmates frequently engage in behaviors putting them at high risk for HIV/HCV transmission and acquisition in the first few weeks after release from prison. Prevention efforts should begin in prison with health education. At the time of release, efforts should focus on promoting safe sex and needle practices, improving access to substance abuse treatment and the provision of safe transitional housing free of drug and alcohol use. Further research is necessary to determine if these initiatives have the ability to improve HIV and HCV outcomes among former inmates released to the community.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This study was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholars Program, the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (1R03DA029448-01), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ K12 HS019464) The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

This work could not have been completed without the assistance of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Addiction Research and Treatment Services and Project Safe at the University of Colorado Denver. We also appreciate the assistance of Denver Health. Robert E. Booth, PhD, Susanne Felton, MA, Larry Williams, Charlotte Nolan, MA, Rebecca Hanratty, MD, Felicia Hill, and Marc F. Stern, MD, MPH, all assisted with this study.

Footnotes

Meetings: Preliminary data were presented at the Society for General Internal Medicine Mountain West Regional meeting in Denver, Colorado, September, 2009, and at the Society for General Internal Medicine National meeting in Phoenix, Arizona, May, 2011.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Adams, Email: Jennifer.adams@dhha.org.

Carolyn Nowels, Email: Carolyn.Nowels@ucdenver.edu.

Karen Corsi, Email: Karen.corsi@ucdenver.edu.

Jeremy Long, Email: Jeremy.long@dhha.org.

John F. Steiner, Email: John.F.steiner@kp.org.

Ingrid A. Binswanger, Email: Ingrid.Binswanger@ucdenver.edu.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Corrections Statistics. Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes T, Wilson DJ. Reentry Trends in the United States. 2003 [cited 2010 February 4]; Available from: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/reentry/reentry.cfm.

- 3.Bird SM, Hutchinson SJ. Male drugs-related deaths in the fortnight after release from prison: Scotland, 1996-99. Addiction. 2003;98(2):185–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey C, et al. Predicting death in young offenders: a retrospective cohort study. Med J Aust. 2004;181(9):473–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding-Pink D. Mortality following release from prison. Med Sci Law. 1990;30(1):12–6. doi: 10.1177/002580249003000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobbs M, et al. Mortality and morbidity in prisoners after release from prison in Western Australia 1995–2003. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice. 2006;(320):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joukamaa M. The mortality of released Finnish prisoners; a 7 year follow-up study of the WATTU project. Forensic Sci Int. 1998;96(1):11–9. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(98)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kariminia A, et al. Factors associated with mortality in a cohort of Australian prisoners. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22(7):417–28. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pratt D, et al. Suicide in recently released prisoners: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet. 2006;368(9530):119–123. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seaman SR, Brettle RP, Gore SM. Mortality from overdose among injecting drug users recently released from prison: database linkage study. Bmj. 1998;316(7129):426–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seymour A, Oliver JS, Black M. Drug-related deaths among recently released prisoners in the Strathclyde Region of Scotland. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45(3):649–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart LM, et al. Risk of death in prisoners after release from jail. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28(1):32–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2004.tb00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verger P, et al. High mortality rates among inmates during the year following their discharge from a French prison. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48(3):614–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Binswanger IA, et al. Release from prison--a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iguchi MY, et al. Elements of well-being affected by criminalizing the drug user. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S146–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersilia J. When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry (Studies in Crime and Public Policy) New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.La Vigne NGVC, Castro J. Chicago Prisoners' Experiences Returning Home. The Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgess-Allen J, Langlois M, Whittaker P. The health needs of ex-prisoners, implications for successful resettlement: A qualitative study. International Journal of Prisoner Health. 2006;2(4):291–301. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patton M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Sage Publications; London, England: 1990. pp. 145–198. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/ January 2, 2011.

- 21.www.colorado.gov. December 4, 2010].

- 22.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenemore TK, Roldan I. Staying straight: Lessons from ex-offenders. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2006;34(1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation. 2006;27(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patton M. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan B. Analyzing qualitative data. Systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandler RKBF, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. JAMA. 2009;301(2):183–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrow KMPSSG. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk behaviors of young men before and after incarceration. AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):235–43. doi: 10.1080/09540120802017586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cartier JJGL, Prendergast ML. The persistence of HIV risk behaviors among methamphetamine-using offenders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(4):437–46. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sifunda SRP, Braithwaite R, Stephens T, Bhengu S, Ruiter RA, van den Borne B. The effectiveness of a peer-led HIV/AIDS and STI health education intervention for prison inmates in South Africa. Health Educ Behavior. 2008;35(4):494–508. doi: 10.1177/1090198106294894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayanwale LM, Moorer E, Shaw H, Habtemariam T, Blackwell V, Foster P, Findlay H, Tameru B, Nganwa D, Ahmad A, Beyene G, Robnett V. PERCEPTIONS OF HIV AND PREVENTION EDUCATION AMONG INMATES OF ALABAMA PRISONS. Am J Health Stud. 2008;23(4):179–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross MWHA, Scott DP, McCann K, Kelley M. Outcomes of Project Wall Talk: an HIV/AIDS peer education program implemented within the Texas State Prison system. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(6):504–17. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.6.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryan ARR, Ruiz MS, O'Neill D. Effectiveness of an HIV prevention intervention in prison among African Americans, Hispanics, and Caucasians. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33(2):154–77. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baillargeon JGGT, Harzke AJ, Baillargeon G, Rich JD, Paar DP. Enrollment in outpatient care among newly released prison inmates with HIV infection. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(supplement 1):64–71. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]