Abstract

Evidence-based practices, such as motivational interviewing (MI), are not widely used in community alcohol and drug treatment settings. Successfully broadening the dissemination of MI will require numerous trainers and supervisors who are equipped to manage common barriers to technology transfer. The aims of the our survey of 36 MI trainers were: 1) to gather opinions about the optimal format, duration, and content for beginning level addiction-focused MI training conducted by novice trainers and 2) to identify the challenges most likely to be encountered during provision of beginning-level MI training and supervision, as well as the most highly recommended strategies for managing those challenges in addiction treatment sites. It is hoped that the findings of this survey will help beginning trainers equip themselves for successful training experiences.

Keywords: Motivational Interviewing, Workshop Training, Clinical Supervision

Motivational Interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2002), a treatment method originally developed for alcohol problems (Miller, 1983), has since been successfully adapted to treat other substance use problems (see Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010 for review). Additionally, in a large effectiveness trial conducted as part of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network, MI was shown in “real world” substance abuse treatment settings to reduce treatment attrition when incorporated into the assessment process (Carroll et al., 2006). Nonetheless, despite its origins as a treatment for substance use problems, a large and increasing body of research supporting its efficacy for this purpose, publication of the first MI text almost two decades ago (Miller & Rollnick, 1991), and evidence from an effectiveness trial that it is possible to successfully implement practices such as MI in “real world” settings, MI (like other evidence-based treatments for substance use problems) is not widely used in these settings (Miller, Sorensen, Selzer, & Brigham, 2006; Morgenstern, 2000). Too often, alcohol and drug treatment providers rely on treatments supported only by anecdotal and idiographic evidence (Carroll & Rounsaville, 2003), treatments with a demonstrated lack of efficacy (Miller et al., 2006), or treatments based only loosely on evidence-based practices (Hanson & Gutheil, 2004). With regard to loose adoption of evidence-based practices: although some might argue that any adoption of evidence-based practices is better than no adoption of such practices, clear evidence to support such assertions is generally lacking. Level of therapist competence and adherence to evidence-based practices has been positively associated with treatment outcomes across many disorders and therapeutic approaches (e.g., McIntosh et al., 2005; Shaw et al., 1999). Thus, a loose adoption of evidence-based practices is unlikely to yield treatment outcomes comparable to those achieved in research.

The limited success of efforts to implement evidence based practices in community alcohol and drug treatment programs stems from many causes. One cause, certainly, is insufficient training opportunities. As Calhoun, Moras, Pilkonis, and Rehm (1998) note, the level of training provided at continuing education workshops is typically insufficient to achieve meaningful changes in provider behavior. In a review of the effectiveness of workshop training for psychosocial addiction treatments, Walters, Matson, Baer, and Ziedonis (2005) concluded that workshops reliably improve providers’ confidence, attitudes, and knowledge. However, skill improvements are not often measured. Furthermore, when skill improvements are assessed, they are often apparent immediately following the workshop, but not maintained over time.

Research specifically focused on training in MI has confirmed that workshop training alone may increase skill, but is insufficient for most providers to achieve competence in MI (Miller & Mount, 2001). Moreover, although incorporating systematic feedback on performance has been shown to improve task performance (Locke & Latham, 1990), small amounts of feedback following workshop training are also insufficient for most providers to achieve competence in MI (Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez & Pirritano, 2004). More recent studies have shown that even multiple supervision or coaching sessions may be insufficient for this purpose (Smith et al., 2007; Mitcheson, Kaanan & McCambridge, 2009). However, in these studies, MI trainees were offered a pre-determined number of supervision or coaching sessions; feedback-based supervision or coaching that continues until the trainee achieves competence is likely a necessary follow-up to workshop training in order to have successful knowledge and skill transfer. This is problematic given that few facilities are equipped to provide this type of training and clinical supervision (Martino et al., 2006).

Even when sufficient training is made available to providers, technology transfer may fail for a variety of reasons such as: lack of incentives for adopting new practices, lack of knowledge or support for new practices by administrators, unwillingness of administrators to modify existing practices to ensure the success of new practices, strong voices of opposition to new practices or support for existing practices, and lack of opportunities for staff input into adoption of new practices (Addiction Technology Transfer Center, 2004). Thus, successful dissemination of MI to “real world” settings will require not only training a large number of MI trainers and supervisors in order to meet the need for intensive and ongoing feedback-based training, but it also requires adequately preparing these trainers and supervisors to manage a variety of barriers to successful technology transfer.

The current survey was conducted to gather opinions and advice from experienced MI trainers, both within and outside the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers, to inform a curriculum designed to prepare individuals who are, themselves, proficient in MI to have successful first experiences in providing training and supervision in MI to addiction treatment providers. Specifically, the first aim of the current survey was to obtain expert opinions about the optimal format, duration, and content for beginning level MI training conducted by novice trainers. The second aim of the current survey was to identify the challenges most likely to be encountered during provision of beginning MI training and supervision, as well as the most highly recommended strategies for managing those challenges. The findings of this survey are intended to help beginning trainers make better use of high quality, publicly available training and technology transfer materials, including the Motivational Interviewing Assessment: Supervisory Tools for Enhancing Proficiency (Martino et al., 2006), the Motivational Interviewing Training for New Trainers (TNT) Resources for Trainers (MINT, 2008), and the Change Book (ATTC, 2004).

Method

Participants

Recruitment of respondents employed three strategies intended to help us obtain a diverse sample of individuals with experience in training MI. First, two emails were posted to the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) listserv describing the curriculum development project and directing interested participants to the web-based survey. Second, the survey team used using the keyword “motivational interview” to search the National Institutes of Health CRISP database to identify individuals currently conducting MI research. Emails were sent to the identified researchers describing the project and inviting them to participate in the web-based survey. Finally, two emails were posted to the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) listserv describing the project and directing interested participants to the survey. Although respondents were not asked to indicate the survey invitation that brought them into the survey, the large proportion of respondents who identified themselves as MINT members (81%), suggests emails to the MINT listserv may have yielded the greatest number of respondents.

A total of 36 individuals responded to the survey. Thirteen respondents were male and 23 were female. Twenty-three respondents reported their age was between 35 and 54 years of age. The remaining respondents reported their age as between 55 and 74 (n = 7) or 25-34 (n = 6). Thirty-three respondents identified their race as White, and thirty-one reported their ethnicity as “Not Hispanic or Latino.” One respondent did not provide race information and 3 respondents did not provide ethnicity information.

Thirty respondents lived in the United States with the remaining 6 respondents indicating they lived in Austria, United Kingdom, Canada, or Italy. Twenty-four respondents reported that their highest educational attainment relevant to the practice and training of MI was a doctorate in a mental health related field, 8 reported that they had a Master’s in a mental health related field (n = 5) or field unrelated to mental health, nursing, or criminal justice (n = 3). The remaining 4 respondents reported 4-year degrees in nursing (n = 1), a criminal justice related field (n = 1), or a field unrelated to mental health, nursing, or criminal justice (n = 2).

Twenty-nine respondents were members of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. Among these, 10 had been members for 1-2 years, 10 had been members for 3-5 years, and 9 had been members for 6 or more years.

All but one respondent (n = 35) reported some experience in providing training in MI, the remaining respondent skipped items pertaining to training experience. Training ranged from very brief presentations to 3+ day workshops or quarter/semester length courses. There was substantial variability in the amount of training provided. Thirty-three respondents had provided some individual or group supervision in MI. Among those who had provided training, estimates of the number of individuals to whom training had been provided ranged from 3 to 1005 (median = 372.5), with 30 respondents reporting they had provided training to 100 or more different individuals. There was also a large amount of variance in the amount of supervision experience reported. Of those who had provided supervision, estimates of the number of individuals to whom supervision had been provided ranged from 3 to 955 (median = 51), with 26 reporting they had supervised more than 10 individuals.

Measures

All data were collected using a survey instrument developed for this curriculum development project. The survey was divided into three sections: 1) background; 2) training format, duration, and content; and 3) effectively managing challenges during MI training. The survey instrument was developed by the authors of this paper with content informed by ongoing dialogues on the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers listserv about issues that arise during the provision of MI training.

Background

The instrument began with items assessing respondent demographic background as well education and experience relevant to MI training and supervision.

Training format, duration, and content

The next section of the survey asked for respondent opinions about 1) optimal trainer to trainee ratios for beginning MI training (ranging from 1:3 or less to greater than 1:18), 2) the maximum number of trainees for beginning MI training (ranging from 5 or fewer to 36-40), 3) the perceived benefits of supervision that includes feedback on taped samples to achievement of proficiency and competence (ranging from 1 = very beneficial to 5 = very unbeneficial), and 4) the willingness of typical trainees to provide tapes samples of their work (ranging from 1 = very willing to 5 = very unwilling).

Following these items, respondents were asked to select the 10 exercises from a prior version of MI Training for New Trainers Resources for Trainers (MINT, 2003) that they most highly recommended for beginning trainers conducting their first MI training. The audience for the training was specified as addiction treatment providers with varied levels of formal training. Respondents were instructed to select exercises based on how easy they believed the exercise would be for a beginning trainer to implement and how effective they felt it was. Thus, respondents were not asked for their opinions about best practices and content for MI training in general, but rather about those practices that would be most likely to result in a successful first workshop experience for a beginning trainer. The original 23 training exercises are listed and briefly described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of respondents endorsing each training exercise as being in the 10-best for beginning trainers

| Exercise | Description | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Batting Practice | Participants “pitch” a series of statements to a batter, who attempts to reflect each statement | 24 (69%) |

| 2. Negative Practice | Listeners use persuasion or roadblocks with a speaker discussing a change they are considering | 23 (66%) |

| 3. Observer Tracking: OARS | Participants track therapist use of open questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries during an observed interaction | 23 (66%) |

| 4. Round Robin | Participants practice skills in a group by taking turns responding to a “client” | 20 (57%) |

| 5. Readiness Ruler Line-up | Participants use readiness ruler to examine their own readiness for training activities | 20 (57%) |

| 6. Structured Practice with a Coach | Listener and speaker are given well-defined roles, usually with carefully specified communication rules; listener gets coaching as needed from another participant | 18 (51%) |

| 7. Observer Tracking: Reflections | Participants track therapist use of reflections during an observed interaction | 17 (49%) |

| 8. Dodge Ball | Like batting practice, but anyone in the group can provide a stimulus or response | 16 (46%) |

| 9. Structured Practice | Listener and speaker are given roles, usually with carefully specified communication rules | 15 (43%) |

| 10. Team Consult | Advisory team provides the listener guidance on what to do during the structured practice | 14 (40%) |

| 11. Observer Tracking: Change Talk | Participants track client utterances about desire, ability, reasons, need, or commitment for change during an observed interaction | 14 (40%) |

| 12. Tag Team | Several participants serve as listener, so as one gets stuck she can tag the next into the exercise | 13 (37%) |

| 13. Brainstorming | Trainer poses a topic, for example, “What is resistance,” and group generates ideas/responses | 12 (34%) |

| 14. Observer Tracking: Client Readiness | Participants track client readiness to change a target behavior during an observed interaction | 11 (31%) |

| 15. Sentence Stems | Trainer provides sentence stems, participants write responses and volunteer to share with group | 10 (29%) |

| 16. Virginia Reel | Form two lines of 4 or more trainees facing each other - counselors have the opportunity to talk sequentially to different clients in order to practice specific counseling skills | 8 (23%) |

| 17. Protagonists | One speaker discusses an issue about which he or she is ambivalent and 4 different listeners take turns with different approaches to resolving the ambivalence | 7 (20%) |

| 18. Three in a Row | Participants describe a typical client, and trainer reports that they are scheduled to see three of these clients in a row to discuss behavior change; the group discusses helpful techniques | 7 (20%) |

| 19. Unfolding Didactic | Presenting didactic material in a way that draws the audience through progressive clues | 6 (17%) |

| 20. Observer Tracking: Wrestling/Dancing | Participants track client/counselor interaction using a continuum from “wrestling” (struggling with one another for control) to “dancing” (moving together smoothly and cooperatively) | 5 (14%) |

| 21. Solitary Writing | Structured writing assignments to be completed independently in prescribed time period | 5 (14%) |

| 22. Quizzes | Self-test to assess participants’ understanding of concepts, such as open versus closed questions | 4 (11%) |

| 23. Observer Tracking: Counselor Client Process | Participants track every counselor and client utterance into one of a small number of categories during an observed interaction | 2 (6%) |

Note. n = 35.

The final items in this section asked respondents to rate the importance (using a scale that ranged from 1 = very important to 5 = very unimportant) to first time MI trainers of 14 general principles/approaches listed in the 2003 resources book. These principles/approaches are presented in Table 2. Complete descriptions of all of these exercises and principles, with the exception of “observer tracking: counselor-client process” are available in the most recent version of the resources book (MINT, 2008).

Table 2.

Perceived importance for beginning MI trainers of general principles/approaches to MI training

| Principle/Approach | Description (if applicable) | Importance Rating Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Trainer demonstrations | 1.36 (0.60) | |

| 2. Role-plays | 1.36 (0.70) | |

| 3. Eliciting | Asking for trainee input throughout training | 1.37 (0.69) |

| 4. Debriefing each activity | 1.49 (1.01) | |

| 5. Setting up a successful role play | Give clear instructions before starting | 1.57 (0.95) |

| 6. Giving feedback to trainees | Suggestions or observations during exercises | 1.63 (0.88) |

| 7. Vital Signs | Ask group about training desires, etc. | 1.71 (0.75) |

| 8. Structuring | Giving trainees an overview of training | 1.74 (0.79) |

| 9. Video demonstrations | 1.74 (1.02) | |

| 10. Generalizing gains | Giving guidance on how to increase expertise in MI | 1.86 (0.91) |

| 11. Preparing a client role | Provide prepared client biography for role play | 2.03 (0.77) |

| 12. Personalizing | Asking trainees to use personal info. during training | 2.14 (1.24) |

| 13. Using metaphor or nonverbal imagery | E.g., “change bouquet” | 2.21 (0.89) |

| 14. Structured counselor feedback | Observe and code trainee performance | 2.55 (1.00) |

| 15. Pre-training structured assessment | 2.85 (1.02) |

Note. n = 35. Means are based on the following scale: 1 = very important; 2 = somewhat important; 3 = neither important nor unimportant; 4 = somewhat unimportant; 5 = very unimportant.

Effectively managing challenges encountered during MI training and supervision

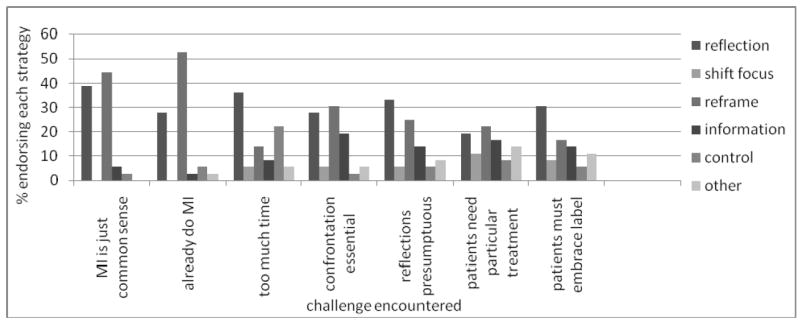

The final section of the survey asked respondents to indicate how often they encountered various challenges during MI training and supervision, as well as what they believed to be the best approach to handling each challenge. Respondents indicated how frequently they encountered each challenge using a 5-point scale (ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always). Response options for how to handle each challenge varied for each type of challenge. The first seven items queried respondents about the frequency with which various participant utterances were encountered during training (see Table 3). These items began with the stem, “One or more participant expresses the belief that…” Sample items include: “MI is just good counseling or ‘common sense’” and “patients must embrace a particular label in order to recover.” Respondents were then asked to indicate which of the following methods they most recommended for addressing each statement: a) reflection (i.e., using reflective listening); b) shifting focus (i.e., address the concern and move to a more workable issue); c) reframing or agreement with a twist (i.e., reflect or validate the trainee’s observations, but offer a new meaning or interpretation for them); d) information provision (providing information or data to address the trainee’s concern); e) emphasizing control (i.e., reminding trainees that they will have to decide whether MI is an approach they want to use); and f) other. All response options except information provision and other were selected from the menu of options recommended in MI for rolling with resistance (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

Table 3.

Mean frequency with which trainee-related challenges are encountered in workshop training

| Challenge encountered | Frequency Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| One or more participants express the belief that… | |

| MI is just good counseling or “common sense.” | 3.21 (1.07) |

| they already do MI (and you doubt this is accurate) | 3.53 (1.08) |

| MI takes too much time and is impossible to implement in their setting(s) | 3.15 (1.18) |

| confrontation is an essential part of treatment | 2.41 (0.96) |

| reflections are presumptuous or will elicit resistance | 2.53 (1.05) |

| patients cannot possibly recover without ___ (a particular form or duration of treatment) | 2.21 (0.88) |

| patients must embrace a particular label in order to recover (e.g., Alcoholic, SMI, etc.) | 2.03 (0.94) |

| One or more participants… | |

| express or evidence anxiety when the trainer observes them during practice exercises | 3.41 (0.99) |

| express or evidence anxiety during practice exercises | 3.15 (1.08) |

| have noticeably less developed basic counseling skills than the other participants | 3.09 (1.00) |

| repeatedly disengage from practice exercises to chat | 2.38 (0.78) |

| will not engage in practice exercise | 1.97 (0.47) |

| inappropriately disclose too much personal information during a practice exercise | 1.85 (0.78) |

| use role plays to complain about their supervisors or others in the room | 1.76 (0.70) |

Note. n = 34. Means are based on the following frequency scale: 1 = never, 2 = seldom, 3 = about half the time, 4 = usually, 5 = always.

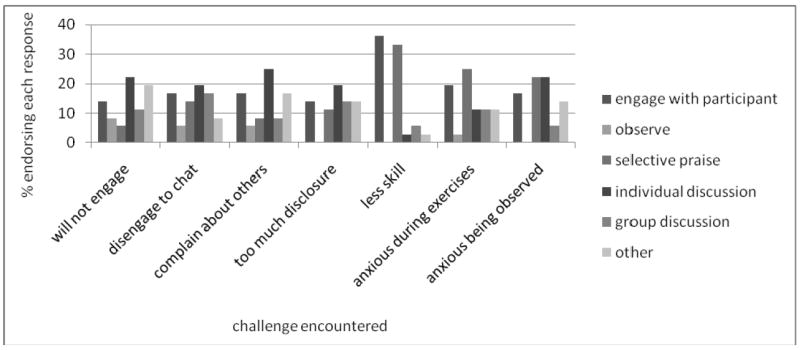

As shown in Table 3, the next seven items assessed how frequently respondents had encountered challenging participant behaviors. These items began with the stem, “One or more participants…” Sample items include: “will not engage in practice exercises” and “express or evidence anxiety during practice exercises.” Respondents were then asked to indicate which of the following methods they most recommended for addressing each behavior: a) silently observe the participant(s)’ practice group; b) observe the participant(s)’ practice group and “jump in” with coaching/suggestions; c) observe the participant(s)’ practice group and selectively praise behavior; d) actively join the participant(s)’ ongoing practice group; e) ask the participant(s) to partner with you on the next practice exercise; f) discuss it with the participant(s) in a serious fashion; g) discuss it with the participant(s) using levity; h) discuss it in a general, but serious fashion with the full group; i) discuss it generally and with levity with the full group; j) other.

The next three items pertained to challenges encountered during MI supervision or coaching, including challenges related to the provision of work samples. As such, only respondents who indicated they currently supervised or coached and asked supervisees to provide taped work samples answered these items. Respondents were asked how frequently one or more supervisees or mentees: 1) “forget” supervision/coaching sessions; 2) will not provide tapes for supervision/coaching; and 3) believe that their taped sample was very proficient while the actual feedback indicated that it was largely MI-inconsistent (i.e., confrontational, many closed questions, not evocative or directive). Respondents were then asked which of the following strategies they most recommended for managing each challenge: a) discuss it with the participant(s) in a serious fashion; b) discuss it with the participant(s) using levity; c) discuss it in a general, but serious fashion with the full group; d) discuss it generally and with levity with the full group; e) other.

The final five items referred to agency-level challenges encountered by respondents when providing MI training. These items were only answered by respondents who indicated they had interacted with agencies when providing MI training. Respondents were first asked to indicate how often they had encountered each of the following challenges using a 5-point scale (ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always): 1) agency does not release participants from their duties for the full duration of training; 2) agency forces staff to participate against their will; 3) agency requires participants to respond to their pager or cell phone during training; 4) agency requests a shorter than necessary training; 5) agency requests training, but refuses to modify their procedures in a way that will allow for successful MI incorporation. Respondents were then asked which of the following strategies they most recommended to address the challenge: a) continue with training as planned; b) provide data/information; c) negotiate a compromise; d) refuse to conduct or complete the training; e) other.

Procedure

All survey responses were collected anonymously via an online survey research tool. The survey was designated by the University of Mississippi Medical Center Institutional Review Board as exempt human subjects research.

Results

Training Exercises

There was substantial variability in respondent perspectives about the best training exercises for beginning trainers. As shown in Table 1, all practice exercises listed were placed in the top 10 by at least 2 respondents, and the highest rated exercise was endorsed by only 69% of respondents. Six exercises were selected by at least ½ the sample (n = 18): batting practice (n = 24), negative practice (n = 23), observer tracking- OARS (n = 23), round robin (n = 20), readiness ruler line-up (n = 20), and structured practice with a coach (n = 18). The remaining exercises among the 11 most highly ranked were: observer tracking – reflections (n = 17), dodge ball (n = 16), structured practice (n = 15), team consult (n = 14), and observer tracking – change talk (n = 14). The five exercises with the lowest endorsement were: unfolding didactic (n = 6), observer tracking – wrestling or dancing (n = 5), solitary writing (n = 5), quizzes (n = 4), and observer tracking – counselor client process (n = 2).

Principles of Training

As shown in Table 2, 10 out of 15 principles or general approaches were rated on average between 2 = fairly important to 1= very important: role plays, trainer demonstration, eliciting, debriefing each activity, setting up a successful role play, giving feedback to trainees, vital signs, video demonstration, structuring, and generalizing gains. The remaining 5 principles or general approaches were rated on average between 3 = neutral to 2 = fairly important: preparing a client role, personalizing, using metaphor and nonverbal imagery, structured counselor feedback, pre-training skill assessment.

Training Logistics

Thirty-four respondents answered the questions about optimal trainer to trainee ratios and maximum training size. There was considerable variance in opinion: 1:10 to 1:12 was the modal rating (n = 14); 11 thought a smaller ratio was optimal (1:4 to 1:9) and 9 thought a higher trainer to trainee ratio was optimal (1:13 to 1:18 or higher). Optimal trainer to trainee ratio was significantly correlated with the total number of individuals a respondent had trained (r = .51, p =.002). There was also considerable variability in perceptions about the maximum size for beginning training. The majority of respondents (n = 26) indicated that the optimal training size was between 11 and 25 participants. Only 2 indicated that 10 or fewer participants was optimal and the remaining 6 reported that optimal training size was larger than 25 participants. Maximum number of trainees was not significantly correlated with the total number of individuals a respondent had trained (r = .16, p = .367).

Challenges Encountered

Respondent utterances during training

A total of 34 respondents provided responses to 7 items inquiring about respondent utterances during training that indicated barriers to training. As shown in Table 3, the most commonly encountered utterances, each of which arose on average about half the time or more, were: “they already do MI,” “MI is just good counseling or common sense,” and “MI takes too much time and is impossible to implement in their setting.” As shown in Figure 2, the most commonly recommended strategies for managing the statement “MI is just good counseling or common sense” were reflection (n =14) and reframing (n = 16). The most commonly recommended strategies for managing the statement “they already do MI” were also reflection (n = 10) or reframing (n = 19). Respondents were more varied in their advice on how to manage the statement “MI takes too much time and is impossible to implement in their setting”: 13 recommended reflection, 8 recommended emphasizing control, 5 recommended reframing, and the remaining respondents recommended information provision (n = 3), shifting focus (n = 2), or other (n = 2).

Figure 2.

Recommended responses to challenging trainee behaviors most frequently encountered in workshop training. Twenty-nine respondents provided recommendations to address each of the behaviors listed, with the exception of “inappropriately disclose too much information” for which 26 respondents provided recommendations. Observe = silently observe the participant(s)’ practice group, selective praise = observe the participant(s)’ practice group and selectively praise behavior. For the purposes of simplified presentation, the following recommended trainer responses were collapsed as follows: engage with participant = observe the participant(s)’ practice group and “jump in” with coaching/suggestions + actively join the participant(s)’ ongoing practice group + ask the participant(s) to partner with you on the next practice exercise; individual discussion = discuss it with the participant(s) in a serious fashion + discuss it with participant(s) using levity; and group discussion = discuss it in a general, but serious fashion with the full group + discuss it generally and with levity with the full group. Complete results are available from the first-author upon request.

Respondent behaviors during training

A total of 34 respondents provided responses to 7 items about respondent behaviors during training that indicated barriers to training. The most commonly encountered behaviors, each of which was encountered on average about half the time or more were: expressing or evidencing anxiety when trainer observes, expressing or evidencing anxiety during practice exercises, and having noticeably less developed basic counseling skills than other trainees (see Table 3). Twenty-nine respondents provided recommendations about the best approach to managing each of these barriers. As shown in Figure 2, the most commonly recommended strategies to manage trainee anxiety when being observed were: observe and selectively praise (n = 8), discuss with trainee using levity (n = 8), other (n = 5) and observe and “jump in” (n = 4). The most commonly recommended strategies to manage anxiety during practice exercises were similar: observe and selectively praise (n = 9), discuss with trainee using levity (n = 4), observe, “jump in” (n = 4), and other (n = 4).

Respondent resistance to supervision

All 36 respondents answered questions about how beneficial supervision that included feedback on taped samples was to gaining skill in MI as well as how willing typical trainees are to provide such tapes. Twenty-three respondents indicated that supervision, which included feedback on taped samples was very beneficial, and 9 reported it was beneficial to the achievement of beginning proficiency in MI. Similarly, the majority of respondents indicated that such supervision was very beneficial (n = 26) or fairly beneficial (n =7) to the achievement of competence in MI. However, only 9 believed trainees would be very willing (n = 3) or fairly willing (n = 6) to provide taped samples of their work in order to receive supervision. In contrast, 21 indicated that typical trainees are fairly unwilling to provide such samples, and 2 indicated that they are very unwilling.

Although 33 respondents reported some experience providing supervision, only 23 indicated that they currently provide supervision. Of those, 17 indicated that they require supervisees to submit taped work samples and a total of 19 respondents answered questions about trainee resistance to supervision. These respondents indicated that on average trainees seldom to never forget to provide session tapes (M = 1.84; SD = 0.69), and seldom to about half the time believe a sample was proficient when it wasn’t (M = 2.17; SD = 0.62) or will not provide tapes (M = 2.50; SD = 0.86). Discussing each of these issues one-on-one with supervisees in a serious fashion was most commonly selected as the best way to address these potential barriers to training

Agency-related barriers to training

A total of 26 respondents reported that they had provided a training for which the agency sponsoring the training required attendance for its staff, 8 reported that they had not provided such training, 1 reported that he or she did not know and 1 skipped all items in this section. When asked how many currently provided training for agencies, 24 reported yes and 11 reported no. All 24 of the individuals who had provided agency-sponsored training responded to items about agency-related barriers to training. The most commonly encountered barrier to training in this context was agencies forcing staff to participate in training against their will. This was reported to occur on average about half the time or more (M = 3.12, SD = 0.85). Most respondents recommended managing this barrier by continuing with the training as planned (n = 9), other (n = 7), or providing information (n = 6).

An additional three barriers were reported as occurring slightly less than half the time: agency requests shorter than necessary training (M = 2.78, SD = 1.20), requests training, but won’t modify agency procedures to allow incorporation of MI in the setting (M = 2.67, SD = 1.20), and agency requires respondents to respond to cell phone or pages during the training (M = 2.63, SD = 1.01). The most commonly recommended strategy for managing requests for insufficient training duration was: negotiating a compromise (n = 12), providing information (n = 5), or continuing with the training as planned (n = 5). The most commonly recommended strategies for agencies unwilling to modify procedures to allow successful adoption of MI were: providing information (n = 10) and negotiating a compromise (n =8). Finally, the most commonly recommended strategies for addressing agencies that require trainees to be “on call” during training were: continuing with the training as planned (n = 10) and negotiating a compromise (n = 8).

Discussion

The goal of the current survey was to glean opinions and advice from experienced MI trainers both within and outside the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers to inform a curriculum designed to prepare individuals who are, themselves, proficient in MI to have successful first experiences in providing training and supervision in MI. Respondents to the survey varied greatly in the amount of training they had provided. Thus, the findings represent a mix of perspectives ranging from seasoned trainers sharing the wisdom and refined training approach acquired through years of experience to new trainers sharing still-fresh “lessons learned the hard-way” from their own beginning training experiences.

There was substantial variability in opinions about which exercises are best for beginning trainers conducting a beginning-level workshop. All of the exercises included in the MINT (2003) Resources for Trainers were endorsed by at least two respondents as being among the best 10. This may suggest that respondents found the “top ten” response format difficult; perhaps all exercises were viewed as strong, and it was difficult to pick only 10. Overall responses indicated that a variety of types of exercises were viewed as best for novice trainers. For example both exercises requiring trainees to generate isolated MI consistent responses (e.g., batting practice, dodge ball, round robin, team consult) and those requiring participants to generate sustained MI consistent responses (e.g., structured practice, structured practice with a coach) were among the 10 most highly endorsed.

Three of the “observer tracking” exercises were also among the 10 most highly endorsed exercises, indicating that respondents believe directing trainees to carefully observe the process that unfolds during therapeutic interactions is an easily implemented and highly effective training tool. Interestingly, each of these three most frequently endorsed observer tracking exercises involved tracking objective behaviors by either the therapists (OARS, reflections) or the clients (change talk). Although respondents were not asked to provide reasons for their selections, these targets for tracking may be viewed as easier to explain to trainees or as more clearly demonstrating to trainees the target behaviors of MI. The finding that the “counselor-client process” and “wrestling or dancing” observer tracking exercises were among the 5 least endorsed exercises is fairly consistent with those interpretations; these two tracking exercises require to trainees to infer and rate therapeutic process variables and thus might require greater trainer skill to present and debrief in a way that optimizes learning of MI.

Finally, negative practice and readiness ruler line-up were also among the 10 most highly endorsed. Negative practice, which requires trainees to use MI-inconsistent responses, was the second most-frequently endorsed exercise, suggesting respondents believe it is beneficial for trainees to contrast use of MI consistent responses to other counseling responses. The readiness ruler line-up, which is an experiential demonstration of this MI technique, was the fifth most endorsed. This may suggest that respondents believe this is an optimal way for beginning trainers to teach this technique for eliciting change talk, and/or that explicit modeling of various aspects of MI spirit through exploration of trainees’ ambivalence about learning or using MI may enhance a beginning trainer’s ability to convey the spirit of MI. Interestingly, three of the exercises that might be considered the least interactive or the most like traditional education techniques--“unfolding didactic,” “quizzes,” and “solitary writing”—were among the five exercises with lowest endorsement.

There was considerable response variability among respondents regarding the optimal trainer to trainee ratio and the optimal size of the training group. An interesting finding from this survey was that optimal trainer to trainee ratio was significantly correlated with the total number of individuals a respondent had trained. This may suggest that more seasoned trainers were more comfortable with larger groups, either due to greater MI training self-efficacy gained through years of training or positive experiences training large groups. On the other hand, this association may simply suggest that trainers who perceive larger trainings as more beneficial tend to conduct larger trainings, and thus reported a greater number of trainees.

With regard to general principles of, and approaches to, MI training, 10 principles or approaches had a mean rating in the “somewhat important” to “very important” range and the remaining five had a mean rating in the “neither important nor unimportant” to “somewhat important range.” In general, those in the latter grouping were more specific (e.g., “preparing a client role”) than those in the former (e.g., “role plays). This suggests that on average respondents believe there is considerable room for latitude in how training is implemented, but that inclusion of demonstrations, role plays, explicit instructions, overviews and debriefings, trainee input, as well as guidance to trainees about their performance during the training and how to improve their performance following the training lead to more successful beginning training experiences.

Structured counselor feedback (based on observed and coded trainee performance) had the second to the lowest mean ranking. This is interesting given that 26 respondents indicated that such feedback is very beneficial for trainees to achieve competence, whereas only 3 of respondents believed that trainees would be very willing to provide work samples to obtain such feedback. Observing and coding trainee practice during a workshop or recording such practices for later coding may help trainers and trainees overcome this barrier to training. The authors have adopted this practice in the ongoing curriculum development project and anecdotally have found that although trainees express some reluctance, they are willing to allow the practice to be recorded. Moreover, it seems to promote provision of additional work samples during the coaching offered after the workshop.

Respondents offered numerous recommendations for managing trainee resistance. Across a variety of trainee utterances that might present a challenge to beginning trainers, reflection and reframing were among the most highly recommended strategies. The most commonly encountered behavioral challenges related to anxiety of trainees with varying levels of pre-training skill. Selective praise was highly endorsed as a strategy for managing all of these challenges. Serious one-on-one discussions were the most frequently recommended strategy to manage challenges encountered during supervision/coaching. With regard to agency-related barriers, each barrier was fairly unique in its most frequently endorsed strategy.

The above results suggest that beginning trainers may need to be more specific in their responses to agency-related barriers to increase the likelihood of successful training experiences. The most commonly endorsed strategies overall—negotiate a compromise, give information, and continue with the training as planned—suggests that beginning trainers should enter their first trainings equipped with sufficient knowledge of the literature on MI and technology transfer to justify their approach to training, strong negotiation skills, and a willingness to continue with training under less than optimal circumstances.

Limitations

An important limitation of the current study was the low response rate. The respondents to the survey were a highly self-selected sample of MI trainers. Although the collective amount of training provided by this group of respondents’ increases confidence that these survey findings can be considered an “expert” opinion on MI training and supervision, the findings likely do not reflect the “consensus” opinion of the broader MI training community. Also, the survey focused on hypothetical training provided within an addiction setting so it is not known if the findings from this survey would generalize to other training settings.

Additional limitations of the current study include that the questions were quantitative, forced-choice response options and that the questions did not specifically focus on respondent’s experiences training addiction treatment providers, although the hypothetical training group was described as addiction treatment providers. A free-response format would have provided a greater window into the wisdom and insights of each of the respondents and questions probing addiction-specific training may have produced different responses. Readers are encouraged to use the findings of this survey with other published information about MI training specifically (e.g., Madson, Loignon, & Lane, 2009) and technology transfer more broadly (e.g., ATTC, 2004) and to seek out mentoring in MI training from an experienced trainer.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In drawing conclusions from these findings, it is important to keep in mind that respondents were not asked for their opinions about best practices and content for MI training in general. Rather, they were asked specifically to identify exercises and principles from a specified set of long-standing exercises and principles (MINT, 2003) that would most likely result in a successful first workshop experience for a beginning trainer. Based on responses, the authors conclude that a mix of negative practice, experiential exercises (e.g., readiness ruler line-up), very structured observations of counselor and client behavior (i.e., observer tracking), targeted skill development activities (e.g., batting practice), and opportunities for extended practice of MI skills (e.g., structured practice) is likely to result in a manageable and successful first training experience. Clear instructions, ongoing feedback to trainees, demonstrations, role-plays, trainer interest in and responsiveness to trainee needs and desires, as well as some discussion of ongoing trainee development can also be essential to successful first training experiences.

With regard to challenges encountered during training, it appears that: a) various challenges are frequently encountered during workshops and supervision/coaching; b) these challenges occur at both the individual trainee and agency level; and c) a broad variety of strategies are identified as useful by respondents for managing these challenges. Prior to their first training experience, beginning trainers may find it useful to rehearse and role play recommended strategies for managing the most frequently encountered challenges. If not successfully managed, these challenges may undermine the training experience for both the beginning trainer and the group of trainees he or she seeks to train.

Figure 1.

Recommended responses to challenging trainee utterances encountered in workshop training. Thirty-three respondents provided recommendations to address each of the utterances listed, with the exception of “patients must embrace a particular label in order to recover” for which 31 respondents provided recommendations.

Acknowledgments

Julie A. Schumacher, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center and G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery Veteran’s Administration Center. Scott F. Coffey, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center. Kimberly S. Walitzer, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York. Randy S. Burke G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery Veteran’s Administration Center and Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center. Daniel C. Williams G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery Veteran’s Administration Center and Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center. Grayson Norquist, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center and G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery Veteran’s Administration Center. T. David Elkin, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center.

The project described was supported by Grant Number R25DA026637 from NIDA. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Contributor Information

Julie A. Schumacher, University of Mississippi Medical Center and G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VAMC

Scott F. Coffey, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Kimberly S. Walitzer, Research Institute on Addictions, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Randy S. Burke, G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VAMC and University of Mississippi Medical Center

Daniel C. Williams, G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VAMC and University of Mississippi Medical Center

Grayson Norquist, University of Mississippi Medical Center and G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VAMC.

T. David Elkin, University of Mississippi Medical Center.

References

- Addiction Technology Transfer Center. The Change Book. ATTC; Kansas City, MO: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun KS, Moras K, Pilkonis PA, Rehm LP. Empirically supported treatments: Implications for training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:151–162. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforder TL, Farentinos C, Kunkel LE, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Morgenstern J, Obert JL, Polcin D, Snead N, Woody GE for the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K, Rounsaville B. Bridging the gap: A hybrid model to link efficacy and effectiveness research in substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:333–339. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson M, Gutheil I. Motivational strategies with alcohol-involved older adults: Implications for social work practice. Social Work. 2004;49:364–372. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke EA, Latham GP. A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke B. Meta-analysis of Motivational interviewing: Twenty five years of research. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Loignon AC, Lane C. Training in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Gallon SL, Hall D, Garcia M, Ceperich S, Farentinos C, Hamilton J, Hausotter W. Motivational interviewing assessment: supervisory tools for enhancing proficiency. Salem, OR: Northwest Frontier Addiction Technology Transfer Center; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh VVW, Jordan J, McKenzie JM, Luty SE, Carter FA, Carter JD, Frampton CMA, Joyce PR. Measuring therapist adherence in psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa: Scale adaption, psychometric properties, and distinguishing psychotherapies. Psychotherapy Research. 2005;15:339–344. doi: 10.1080/10503300500091124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Mount KA. A small study of training in motivational interviewing: Does one workshop change clinician and client behavior? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guildford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sorensen JL, Selzer JA, Brigham GS. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: A review with suggestions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1050–62. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitcheson L, Bhavsar K, McCambridge J. Randomized trial of training and supervision in motivational interviewing with adolescent drug treatment practitioners. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J. Effective technology transfer in alcohol treatment. Substance Use & Misuse. 2000;35:1659–1678. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. Motivational interviewing training new trainers (TNT). Resources for trainers. 2003 Nov; Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. Motivational interviewing training new trainers (TNT). Resources for trainers. 2008 Nov; Retrieved July 8, 2010, from the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers Web site: http://www.motivationalinterview.org/TNT_Manual_Nov_08.pdf.

- Shaw BF, Elkin I, Yamaguchi J, Olmsted M, Vallis TM, Dobson KS, Lowery A, Sotsky SM, Watkins JT, Imber SD. Therapist competence ratings in relation to clinical outcome in cognitive therapy of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:837–846. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Amrhein PC, Brooks AC, Carpenter KM, Levin D, Schreiber EA, Travaglini LA, Nunes EV. Providing live supervision via teleconferencing improves acquisition of motivational interviewing skills after workshop attendance. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:163–168. doi: 10.1080/00952990601091150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Matson SA, Baer JS, Ziedonis DM. Effectiveness of workshop training for psychosocial addiction treatments: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]