Abstract

The complexity of surgical procedures often poses challenges for conducting a rigorous and comprehensive evaluation. This paper considers the final two IDEAL stages of surgical innovation. Surgical randomised controlled trials are often challenging to undertake and require careful consideration of the intervention definition, who should deliver it, and the impact of surgeon and patient preferences. In the long term study stage, better monitoring of surgical procedures is needed, along with improved surveillance of devices.

Introduction

The IDEAL framework describes the stages through which interventional therapy innovation normally passes: idea, development, exploration, assessment, and long term follow-up (also known as stages 1, 2a, 2b, 3, and 4, respectively). This paper focuses on the stages of assessment (specifically in relation to randomised trials) and long term follow-up. By the assessment stage, a new intervention will have shown early promise and be used increasingly by the surgical community; however, the intervention’s relative benefit compared with alternative approaches will be uncertain. At the long term follow-up stage, a surgical intervention will need further assessment owing to technical refinements or to related devices or procedures being brought onto the market.

Surgical procedures are conducted with an almost infinite set of subtle variations: surgeon training, team expertise, personal practice, centre policy and infrastructure, anatomical features of the patient, and the use of a variety of medical devices. Beyond the procedure, other factors are implicitly part of the intervention: the type of anaesthesia used,1 preoperative and postoperative management (including drug treatments such as aspirin),2 physiotherapy,3 and psychological interventions (including verbal guidance).4 These linked and interdependent components produce a complex intervention.5 At the assessment and long term stages, this complexity is most apparent and challenging for conducting a rigorous and comprehensive evaluation of a surgical intervention.

Another challenge is to measure outcomes comprehensively; surgical studies are also limited by their selection of outcomes, which are often short term, “operation” focussed, and inconsistently defined. Properly conducted randomised controlled trials and observational studies with agreed and defined core outcomes are needed at these critical stages.6 The failure to conduct methodologically rigorous studies has resulted in some surgical interventions becoming and remaining standard practice without good evidence.7 8 Similarly, new medical devices are widely used without due assessment.9 In this paper, we consider in turn the roles of randomised controlled trials in the assessment stage and evaluations in the long term stage.

Randomised controlled trials in the assessment stage

The role of randomised controlled trials in evaluating surgical interventions has been debated over the past 30 years.7 8 10 11 A consensus in favour of accepting properly conducted trials as the “gold standard” for comparisons of efficacy and effectiveness between surgical procedures has eventually emerged, although not without controversy.8 While several surgical trials have been successful and influential,10 12 others have been attempted and failed13 or have not had the anticipated influence on the adoption of the intervention.14 Even if a trial evaluation is undertaken successfully, factors out of the study investigators’ control (for example, innovations and technological changes) can lead to uncertainty about the evaluation’s applicability.15

The assessment stage provides a window of opportunity—albeit sometimes a brief one—to obtain definite randomised evidence about effectiveness. The IDEAL framework proposes that a large multicentre trial is most valuable and viable during the assessment stage, although small single centre trials might appear as early as IDEAL stage 2a. Randomised controlled trials have an array of potential problems in evaluating surgical techniques (box 1),8 16 17 and most stem from three related issues: the intervention definition, who delivers the intervention, and the treatment preferences of surgeons and patients.

Box 1: Potential solutions to overcome common variations in surgical randomised controlled trials

Surgeon preferences

Maximise flexibility in the delivery of surgical interventions, beyond the key distinctive elements, to allow for variation in surgeon and centre practices

Implement recruitment of participants by a third party

Use broad patient eligibility criteria

Undertake preliminary work to establish consensus regarding community uncertainty

Adopt an expertise based trial design

Patient preferences

Undertake a qualitative evaluation of patients’ perspectives and experiences

Quality control of the intervention

Use criteria for surgeon eligibility (for example, training and previous number of cases)

Record an objective measure of quality (for example, lymph node yield for gastric cancer surgery)

Record indicators of surgical decision making (for example, conversion from partial to total knee replacement, or from laparoscopic to open surgery)

Intervention definition

How tightly the intervention should be defined will depend on the type of comparison (table). Trials investigating the auxiliary facets of the intervention are valuable, but studies evaluating the surgical core of an innovative procedure (whether a new procedure or a modification of an established procedure) are crucial. In a comparison of medical versus surgical trials, the definition of surgery can be broad. For example, in a trial of medical treatment versus hysterectomy, the type and route of the hysterectomy was left to the discretion of the gynaecologists, as was the medical treatment (although there was a suggested regimen).18 In a trial comparing open versus laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia, surgeons were allowed to choose the type of open and laparoscopic repair.19

Surgical trials examples—standardisation of interventions and eligibility criteria of patients and surgeons

| Research question | No of centres | Patient/surgeon eligibility | Standardisation of interventions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative care | Preoperative and postoperative care | |||

| Stapler v hand sewn closure after distalpancreatectomy (DISPACT)21 | 21 | Broad/training given to all participating surgeons (centre had to perform 10 pancreatic resections per year) | Resection and closure procedures standardised; stapler specified; type of incision not standardised; no additional intraoperative treatment or covering of the pancreatic remnant; splenectomy in addition to distal pancreatectomy at discretion of surgeon; standardised policy in relation to octreotide use at sites; pain management not standardised | Bowel preparation not standardised; standardised drain use; recovery not standardised (for example, location, feeding, and mobilisation) |

| Treatment of tibial fractures with reamed or non-reamed intrameduallary nails (SPRINT)40 | 29 | Broad/no reported restrictions | Standardised reamed nailing and unreamed nailing procedures | Standardised antibiotic use in open and closed fractures; standardised mobilisation (both open and closed) and use of growth stimulation not allowed during first 12 months; wound closure (open); dynamisation of the nail (both) and reoperation (open) only allowed in specific circumstances |

| Treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1) with endovascular or open repair15 |

34 | Broad/hospitals had to complete 20 endovascular repair procedures | Choice of EVAR device left to participating surgeons, otherwise no stated restrictions | No stated restrictions |

| Treatment of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding with surgical or medical treatment (Ms study)18 | 2 | Broad/no stated restrictions | Type and route of hysterectomy at discretion of surgeon; prophylactic oophorectomies were discouraged | No stated restrictions |

| Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee with arthroscopic débridement, arthroscopic lavage, or placebo surgery41 | 1 | Broad/one surgeon performed all operations | Surgical interventions standardised | Standardised anaesthetic; mobilisation and pain management (analgesics) |

If special equipment is needed, the medical device used does not typically need to be not restricted. In trials of medical devices, or where the related procedures being compared are similar, it may be necessary to define each intervention precisely and to introduce process control measures to check on compliance to preclude contamination and control the effect of ancillary care.20 Small changes in technique or technology can have a substantial effect on outcomes, as shown by recent research relating to metal-on-metal hip devices.9

Measuring adherence regarding intervention delivery has been rare in surgical trials, but can help in interpreting the applicability (generalisability) of the results. Example measures include specimen margin examination or node counts in cancer procedures, or taking photographs after completion of key parts of the procedure.21 22 Deciding on restrictions requires careful consideration of the research question and the potential risk of bias and confounders (such as associated treatments), although as few restrictions as possible is preferable.

Who should deliver the intervention?

Every operation should be carried out or supervised closely by someone with appropriate level of expertise and training. Collectively, participating surgeons should have sufficient expertise in order for the surgical community to embrace the trial and its findings. The traditional approach—where each surgeon delivers both or all surgical interventions in the trial—has been criticised. A comparison could be deemed unfair if surgeons have more expertise in one intervention than another.

This problem can be managed in two ways. Firstly, trial participation can be restricted to surgeons with an acceptable level of expertise in both or all surgical interventions. Surgeon eligibility criteria have generally focussed on markers of training and previous experience of the intervention (for example, completing 10 laparoscopic hernia procedures). Professional grade, year of experience, and annual caseload can be used as markers, although a more rigorous standard of direct demonstration of surgical competency has also been proposed (for example, providing training and supervision before participation).23 Under the second approach, participating surgeons deliver only the interventions in which they have expertise (an expertise based trial).24 There is limited evidence about how well this approach works to date, and such designs are not without statistical and practical disadvantages.25 Whatever approach is adopted, other factors can lead to differences in outcome between surgeons (such as ancillary care and centre admission policies) although they are rarely, if ever, fully standardised.

Impact of treatment preferences

The preferences of both patients and surgeons are a key factor that affects the success of a randomised controlled trial, and can be the decisive influence upon recruitment.26 If patients tend to prefer one of the treatments, they are unlikely to agree to be randomised in case they are assigned to another treatment. The merit of an otherwise well designed and conducted trial can be fatally undermined if too few surgeons are willing to be involved. There is, however, a strong relationship between the patient and the surgeon, who may have his or her own strong preferences and have traditionally acted as gatekeeper and facilitator.27 Recent evidence28 demonstrated that patients’ preferences expressed during consultations could be influenced by surgeon recruiters, who seemed to unconsciously transmit their own preferences during the consent process. Properly informed patients could be more likely to consent to randomisation.

For multicentre trials, a pragmatic approach to patient eligibility that achieves general agreement and understanding is important. Surgeon preferences often depend on the patient’s prognosis. The Spine Stabilisation Trial29 explicitly adopted broad inclusion criteria, using an approach to recruitment based on the “uncertainty principle”: surgeons could restrict randomisation to eligible patients which they personally were uncertain as to which intervention would be the best option (known as personal equipoise). However, this approach seems to have led to misunderstanding among participating surgeons about the pragmatic nature of the trial design and the explicit aim of seeking to recruit a wide spectrum of potential patients. A successful example is the first EVAR trial on endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm, which had broad eligibility criteria and achieved its recruitment target.12 Transmission of preference can be mitigated if consent is obtained by a trained and possibly neutral recruiter, who is not delivering any intervention (such as a research nurse). The merits of this approach will differ according to the research question.

Long term study stage

Although the benefit of a particular surgical intervention (for example, knee replacement) might be well established, the use of a particular variation in the approach (such as using a posterior approach) or device selection is often open to question long after widespread adoption. This provides an opportunity to obtain good evidence about safety and effectiveness of techniques or technologies from observational and surveillance studies. Current research on long term surveillance focuses mainly on medical devices and—in the case of surgery—implantable devices. One reason for this focus is the cost; the medical device market in 2008 was estimated to exceed £150bn (€177bn; $232bn) worldwide.30 Surveillance of the long term effect of surgical innovation (both in terms of the procedure and devices) is imperative even if short term benefit has been established (at IDEAL stages 1-3). The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently developed a conceptual framework for medical devices specifically,31 although it needs to be developed and refined in the context of long term surveillance. Box 2 provides an example of a long term surveillance study.

Box 2: Example of observational study at the long term study stage9

Implanted devices for total hip replacement

Clinical background at time of conduct

Total hip replacement is widely undertaken although revision is sometimes necessary, particularly in younger recipients

Alternative devices with a larger head size and different bearing surface materials (such as metal-on-metal devices) have increasingly been used to reduce revisions

Design

Long term, device surveillance study nested within a population based registry

Primary stemmed operations of total hip replacement done between 2003 and 2011 (n=402 051) were linked to revision operations

Operations involving different types of devices (varying bearing surface and head size)

Findings

Metal-on-metal devices had poorer survival than devices with alternative surfaces

Lower device survival found in women, and for those devices with larger heads

Long term evaluation of procedures

Well designed, large observational studies (for example, based on registries) can be used to evaluate procedures in the long term study stage; they can also provide data for outcomes in subgroups of interest as well as rare endpoints in safety and effectiveness.32 From an assessment perspective, some national or nationally representative patient registries can be defined as observational studies collecting “uniform data, to evaluate specified outcomes for a population defined by a particular disease, condition, or exposure.” Registries can be designed to capture data for specific conditions or exposures (such as surgery or devices), types of healthcare service delivered (such as surgical treatment or diagnostic procedure), or specific outcomes (such as an adverse event, disorder, or disease), to improve the delivery of care.

Practical factors often determine which data are collected, but in principle, disease based registries have the advantage of enabling consideration of selection for a procedure and potential for associated bias in an evaluation. Procedure registries can provide useful comparative evidence for different interventions and devices. Longstanding procedure registries include those developed by professional societies such as the United Kingdom’s Society for Cardiothoractic Surgery’s adult cardiac surgery database or the Society of Thoracic Surgeons’ registry.33 Other studies (including randomised controlled trials) can be nested in them. The Swedish national registry of gallstone surgery and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (GallRiks) enabled a large cohort study to quantify survival and incidence of bile duct injuries and explore the relation between them.34

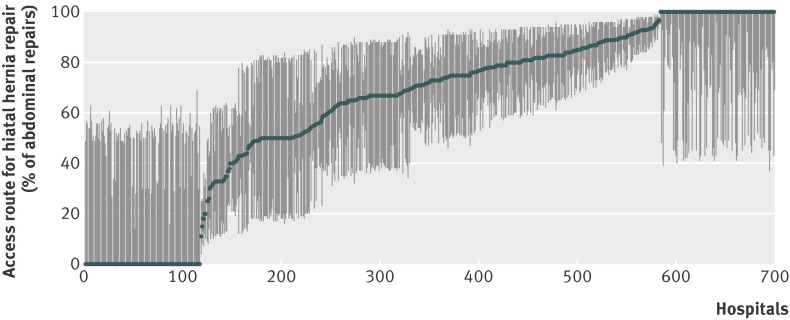

The choice of surgical procedure or medical device can often vary greatly, even for similar patients within and between centres. For example, the figure shows the proportion of operations using abdominal access (versus thoracic access) in hiatal hernia repair, in hospitals in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.35 The choice of access route was strongly influenced by surgeon practice and institutional culture, and was unlikely to be related to the hernia location for many hospitals.35 In most hospitals, the majority of hernia repairs were conducted via abdominal access—that is, the hernia location did not dictate the approach and therefore any confounding by indication will probably be limited. Identifying such practice and surgeon patterns can, therefore, help clarify the extent to which selection of patients for receiving the procedure (or device) may have occurred. Exploration of variations in practice can improve the design of comparative studies, by providing insight regarding the likelihood of the main potential bias—confounding by indication.36

Use of the abdominal route (versus thoracic route) as a proportion of operations in hiatal hernia repair, by hospital. Data taken from US hospitals in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample35; figure shows 708 hospitals (900 hospitals with 100% abdominal route use not shown). Blue=percentage of operations with abdominal route; black=95% exact (binomial) confidence intervals. Use of the abdominal route varied from 0% to 100% across hospitals

The modes of follow-up are critical,32 as are completeness and accuracy of data collection, which can lead to loss of follow-up and various misclassification biases (for example, outcomes of difficult operative cases being attributed to revision surgery or a medical device). Standardisation of terminology, as in earlier stages,36 would allow routine capture of information on surgical procedures such as the use of a laparoscopic approach, laterality (side of surgery), and device information. Similarly, standardised terminology for devices (such as from the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium or product catalogues) will help to accurately describe the specific attributes and properly identify the technology used.

However, such studies have inherent and common limitations. Firstly, the concept of “intention to treat” does not readily map onto observation data, and only the first procedure or devices used is readily interpretable. If a patient subsequently receives another procedure that converts failure after the first procedure into success, this outcome could be misattributed to the first procedure. Observational studies (including registry based studies) should, whenever possible, construct intention to treat analyses that correspond to treatment decisions as they occur in the real world. However, key data are often not routinely collected. Reasoned inferences can be made from the clinical scenario using resource use data. For example, if routine data show that both partial and total knee devices were used in the same knee during an operation, it can be appropriately inferred that it was necessary to change a partial device to a total one, as it is impossible for the opposite to occur.

Secondly, the time between cohort entry (assignment to procedure) and date of first exposure (actual delivery of procedure) is often not recorded. This leads to “immortal time bias,” a period of follow-up after assignment during which outcomes of treatment that determine the end of follow-up cannot occur, as the treatment has not yet happened. This bias can confound results, because interventions that are delivered faster could look worse than those needing more time (for example, sicker patients might die before receiving the therapy and being accounted for). Finally, another difficult situation is when the originally assigned (intended) treatment switches before initiation. This switch can be due to patient refusal, financial factors, or other considerations. Again, such information is not typically collected by observational data sources but is often needed for meaningful interpretation.

Surveillance of devices

In the US and UK, manufacturers and importers are required to submit reports of device related deaths, serious injuries, and malfunctions to the regulatory bodies. US hospitals and nursing homes are required to submit reports of device related deaths and serious injuries to the manufacturer and only deaths to the FDA, but healthcare providers and consumers can submit reports voluntarily (through MedWatch).37 Such passive reporting systems typically have important weaknesses, including:

Incomplete or inaccurate data that are usually not independently verified

Data reflecting reporting biases driven by event severity or uniqueness, publicity, or litigation

Causality cannot be inferred from any individual report

Events are generally under-reported and this, in combination with lack of denominator (exposure) data, precludes determination of event incidence or prevalence.

However, reports received through passive and enhanced systems are often useful and have resulted in important public health alerts related to:

Transvaginal placement of surgical mesh

Use of recombinant bone morphogenetic protein in cervical spine fusion

Interactions induced by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with implanted neurological stimulators.37

In addition, the FDA has developed an enhanced surveillance system using several different modes of surveillance, including active surveillance. This system, known as the Medical Product Safety Network,38 provides national surveillance of medical devices based on a representative subset of user facilities. Routine data collection and monitoring for devices need improvement. Finally, when resources are available, active surveillance based on registries can also help monitor high risk surgery and devices, such as a national registry of implanted ventricular assisted devices.39

Summary

A large, multicentre, randomised controlled trial in the assessment stage complements observational evaluation in the long term study stage. Large and preferably national patient registries are best suited for long term surveillance studies of surgical procedures. Surveillance of devices with improved data collection is needed. Owing to the inherent complexity of surgery and variation in practice, both randomised controlled trials and surveillance studies face particular challenges. However, solutions are often available, and such difficulties should not prevent rigorous and comprehensive evaluation of surgical innovations.

Summary points

Rigorous evaluation of surgical innovations is needed in the assessment and long term study stages, which together meet the need for comprehensive outcome assessment

Randomised trials of surgical interventions, along with observational studies in the long term study stage, should be designed which acknowledge the complexity of surgery

Key issues for surgical trial design are specification of the interventions, who will deliver the interventions, and assessing the potential impact of patient and surgeon preferences

Long term evaluations of the procedure and any related devices is needed, along with the development of data collection and methodology for surveillance

The Health Services Research Unit is core funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the Chief Scientist Office or the funders.

Contributors: JAC and PM formulated the IDEAL series to which this paper belongs. JAC and AS wrote the first draft of this paper; JMB, DJB, DM-D, and PM all commented on the draft. All authors approved the final version, and JAC and AS are the guarantors. The papers were informed by the IDEAL workshop in December 2010.

IDEAL workshop participants (December 2010): Doug Altman, Jeff Aronson, David Beard, Jane Blazeby, Bruce Campbell, Andrew Carr, Tammy Clifford, Jonathan Cook, Pierre Dagenais, Philipp Dahm, Peter Davidson, Hugh Davies, Markus Diener, Jonothan Earnshaw, Patrick Ergina, Shamiram Feinglass, Trish Groves, Sion Glyn-Jones, Muir Gray, Alison Halliday, Judith Hargreaves, Carl Heneghan, Jo Carol Hiatt, Sean Kehoe, Nicola Lennard, Georgios Lyratzopoulos, Guy Maddern, Danica Marinac-Dabic, Peter McCulloch, Jon Nicholl, Markus Ott, Art Sedrakyan, Dan Schaber, Frank Schuller, Bill Summerskill.

Funding: PM received funding from the National Institute for Health Research’s Health Technology Assessment programme, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, and Zimmer (all unrestricted grants) for the IDEAL workshop in December 2010. JAC holds a Medical Research Council Methodology Fellowship (G1002292). JMB is supported in part by the Medical Research Council ConDuCT Hub for Trials Methodology Research. AS is supported in part by the US Food and Drug Administration contract for MDEpiNet Science and Infrastructure Centre (HHSF22321110172C).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: PM received financial support from the National Institute for Health Research’s Health Technology Assessment programme, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, and Zimmer for the IDEAL collaboration and for a workshop; DB has undertaken consultancy for ICNet and Stryker European Medicines Agency, and has received research grant funding from Genzyme; no other financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f2820

References

- 1.Cuthbertson BH, Campbell MK, Stott SA, Vale L, Norrie J, Kinsella J, et al. A pragmatic multi-centre randomised controlled trial of fluid loading and level of dependency in high-risk surgical patients undergoing major elective surgery: trial protocol. Trials 2010;11:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown GA. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after major orthopaedic surgery: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty 2009;24(6 suppl):77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter KF, Glazener CM, Moore KN. Conservative management for postprostatectomy urinary incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;2:001843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell R, McKee L, Bruce J. Information and behavioural instruction along the health-care pathway: the perspective of people undergoing hernia repair surgery and the role of formal and informal information sources. Health Expectations 2009;12:149-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comet Initiative. Home page. 2013. www.comet-initiative.org/.

- 7.McCulloch P, Taylor I, Sasako M, Lovett B, Griffin D. Randomised trials in surgery: problems and possible solutions. BMJ 2002;324:1448-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook JA. The challenges faced in the design, conduct and analysis of surgical randomised controlled trials. Trials 2009;10:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW, National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet 2012;379:1199-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baum M. Reflections on randomised controlled trials in surgery. Lancet 1999;353(suppl 1):S6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollock AV. Surgical evaluation at the crossroads. Br J Surg 1993;80:964-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EVAR trial participants. Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:2179-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Challah S, Mays NB. The randomised controlled trial in the evaluation of new technology: a case study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:877-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price AJ, Rees JL, Beard D, Juszczak E, Carter S, White S, et al. A mobile-bearing total knee prosthesis compared with a fixed-bearing prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003;85:62-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Kingdom EVAR Trial I, Greenhalgh RM, Brown LC, Powell JT, Thompson SG, Epstein D, et al. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1863-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ergina PL, Cook JA, Blazeby JM, Boutron I, Clavien PA, Reeves BC, et al. Challenges in evaluating surgical innovation. Lancet 2009;374:1097-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCulloch P. Developing appropriate methodology for the study of surgical techniques. J R Soc Med 2009;102:51-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuppermann M, Varner RE, Summitt RL Jr, Learman LA, Ireland C, Vittinghoff E, et al. Effect of hysterectomy vs medical treatment on health-related quality of life and sexual functioning: the medicine or surgery (Ms) randomized trial. JAMA 2004;291:1447-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross S, Scott N, Grant AS, O’Dwyer P, Wright D, McIntosh E, et al. Laparoscopic versus open repair of groin hernia: a randomised comparison. Lancet 1999;354:185-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonenkamp JJ, Songun I, Hermans J, Sasako M, Welvaart K, Plukker JT, et al. Randomised comparison of morbidity after D1 and D2 dissection for gastric cancer in 996 Dutch patients. Lancet 1995;345:745-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diener MK, Seiler CM, Rossion I, Kleeff J, Glanemann M, Butturini G, et al. Efficacy of stapler versus hand-sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): a randomised, controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 2011;377:1514-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fairbank J, Frost H, Wilson-MacDonald J, Yu LM, Barker K, Collins R; Spine Stabilisation Trial Group. Randomised controlled trial to compare surgical stabilisation of the lumbar spine with an intensive rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low back pain: the MRC spine stabilisation trial. BMJ 2005;330:1233-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook JA, Ramsay CR, Fayers P. Statistical evaluation of learning effects in surgical trials. Clin Trials 2004;1:421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereaux PJ, Bhandari M, Clarke M, Montori VM, Cook DJ, Yusuf S, et al. Need for expertise based randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2005;330:88-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biau DJ, Porcher R. Letter to the editor re: Orthopaedic surgeons prefer to participate in expertise-based randomized trials. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:298-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barkun JS, Aronson JK, Feldman LS, Maddern GJ, Strasberg SM, Balliol C, et al. Evaluation and stages of surgical innovations. Lancet 2009;374:1089-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meakins JL. Innovation in surgery: the rules of evidence. Am J Surg 2002;183:399-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills N, Donovan JL, Wade J, Hamdy FC, Neal DE, Lane JA. Exploring treatment preferences facilitated recruitment to randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1127-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziebland S, Featherstone K, Snowdon C, Barker K, Frost H, Fairbank J. Does it matter if clinicians recruiting for a trial don’t understand what the trial is really about? Qualitative study of surgeons’ experiences of participation in a pragmatic multi-centre RCT. Trials 2007;8:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Health Industries. Medical device industry assessment. 24 March 2010. www.ita.doc.gov/td/health/medical.html.

- 31.Sedrakyan A, Marinac-Dabic D, Normand ST, Mushlin AS, Gross T. A framework for evidence evaluation and methodological issues in implantable device studies. Med Care 2010;48(suppl 1):S121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dreyer NA, Garner S. Registries for robust evidence. JAMA 2009;302:790-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson E, Kaul P, Kaczmarek R, Hammill B, Armstrong P, Bridges C, et al. From controlled trials to clinical practice: monitoring transmyocardial revascularization use and outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tornqvist B, Stromberg C, Persson G, Nilsson M. Effect of intended intraoperative cholangiography and early detection of bile duct injury on survival after cholecystectomy: population based cohort study. BMJ 2012;345:e6457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Overview of the National Inpatient Sample. 2013. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp/.

- 36.Ergina PL, Barkun JS, McCulloch P, Cook JA, Altman DG, on behalf of the IDEAL group. IDEAL framework for surgical innovation 2: observational studies in the exploration and assessment stages. BMJ 2013;346:f3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.US Food and Drug Administration. MedWatch: the FDA safety information and adverse event reporting program. 2013. www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/.

- 38.US Food and Drug Administration. MedSun: medical product safety network. 2012. www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/MedSunMedicalProductSafetyNetwork/default.htm.

- 39.University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine. Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support. 2013. www.intermacs.org.

- 40.Study to Prospectively Evaluate Reamed Intramedullary Nails in Patients with Tibial Fractures Investigators; Bhandari M, Guyatt G, Tornetta P 3rd, Schemitsch EH, Swiontkowski M, et al. Randomized trial of reamed and unreamed intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:2567-78.19047701 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moseley JB, O’Malley K, Petersen NJ, Menke TJ, Brody BA, Kuykendall DH, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2002;347:81-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]