Summary

Response regulators (RRs), which undergo phosphorylation/dephosphorylation at aspartate residues, are highly prevalent in bacterial signal transduction. RRs typically contain an N-terminal receiver domain that regulates the activities of a C-terminal DNA-binding domain in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. We present crystallography and solution NMR data for the receiver domain of Escherichia coli PhoB, which show distinct two-fold symmetric dimers in the inactive and active states, providing the first such pair within the OmpR/PhoB subfamily, the largest group of RRs. These structures together with the previously determined structure of the C-terminal domain of PhoB bound to DNA, define the conformation of the active transcription factor, and provide a model for the mechanism of activation in this subfamily. In the active state, the receiver domains dimerize with two-fold rotational symmetry using their α4-β5-α5 faces, while the effector domains bind to DNA direct repeats with tandem symmetry, implying a loss of intramolecular interactions.

Introduction

Bacteria sense and respond to a wide variety of signals through a complex network of signaling systems, many of which are two-component phosphotransfer pathways. These systems regulate many processes including nutrient uptake, sporulation, chemotaxis, virulence, quorum sensing and cell adhesion. They are widespread in bacteria and archea (Volz, 1993), are present in some fungi (Maeda et al., 1994; Ota and Varshavsky, 1993) and plants (Chang and Meyerowitz, 1994), but have not been found in animals. Their complete absence in humans and their involvement in virulence and antibiotic resistance in bacteria make them attractive drug targets. In the simplest form, a two-component system consists of two modular proteins: a sensory histidine kinase and a response regulator (RR). An environmental signal modulates the activities of the histidine kinase that undergoes ATP-dependent auto-phosphorylation at a conserved histidine residue. The kinase regulates the activities of its cognate RR by donating its phosphoryl group to a conserved aspartate in the inactive RR thus activating it, or by acting as a phosphatase and dephosphorylating the active RR. RRs typically function as DNA-binding transcription factors, although some function as enzymes or as protein-protein interaction domains. They contain single or multiple domains, often a conserved N-terminal receiver domain that contains the site of phosphorylation and a C-terminal effector domain that performs the output function. The transcription factor RRs are further divided into three major subfamilies namely OmpR/PhoB, NarL/FixJ and NtrC/DctD, based on similarity of their output domains. The OmpR/PhoB subfamily is the largest, accounting for 45% of all RRs in Escherichia coli.

Structural characterization of isolated domains of RRs has provided insight to function, but a complete description of the mechanism of phosphorylation-mediated regulation is lacking. Structures of the conserved receiver domains of several RRs in both active and inactive states (Birck et al., 1999; Halkides et al., 2000; Kern et al., 1999; Lewis et al., 1999) have established a common mechanism for the propagation of phosphorylation-induced conformational changes. Phosphorylation at the active site aspartate is accompanied by reorientation of a few highly conserved residues leading to allosteric structural perturbations that extend from the site of phosphorylation to a distant face, known as the “functional” face of the receiver domain. Many structures are available for effector domains, and the fold of the effector domain is known for all three major classes of RR transcription factors.

Despite the availability of structures for individual domains, it is not clear how phosphorylation of receiver domains promotes DNA binding and transcriptional activation by effector domains in the OmpR/PhoB subfamily. Two important structural descriptions are lacking. First, there are no structures available for active proteins in the OmpR/PhoB subfamily, possibly due to the intrinsic instability of the active site phosho-aspartate bond that poses challenges for crystallization and NMR studies. Second, little information is available about the receiver domain: effector domain interfaces in these proteins due to a paucity of structures of full-length proteins. Two full-length structures are available for OmpR/PhoB subfamily members DrrB (Robinson et al., 2003) and DrrD (Buckler et al., 2002) from the thermophile Thermotoga maritima in the inactive state. In both proteins, the recognition helices in the DNA-binding domains are completely exposed and sterically unhindered by the regulatory domains. This suggests that the mechanism of phosphorylation-mediated activation for members of the OmpR/PhoB subfamily may not be based on phosphorylation-induced relief of steric inhibition as suggested by structures of RRs of other subfamilies (Baikalov et al., 1996; Djordjevic et al., 1998).

We have used NMR and X-ray crystallography to address the mechanism of activation of an RR of the OmpR/PhoB subfamily in the PhoR/PhoB system, a well-characterized two-component pathway activated by inorganic phosphate (Pi) limiting conditions (Makino et al., 1989). PhoR is a histidine protein kinase that modulates the activities of the RR PhoB in response to the availability of extracellular phosphate. PhoB is the master regulator of ~39 genes in seven or more operons and three independent genes which together make up the Pho regulon. It controls the synthesis of many proteins for rapid Pi uptake and for utilization of alternate phosphorus sources, including the periplasmic enzyme alkaline phosphatase and the high affinity Pi uptake systems Pst and Ugp. In the absence of PhoR, PhoB can be cross-phosphorylated by the histidine protein kinase CreC in response to specific catabolites or phosphorylated directly by acetyl phosphate in a Pi-independent manner, underscoring its global role in cellular growth and metabolism (Wanner, 1993). PhoB has also been implicated in crosstalk with other regulatory proteins involved in antibiotic resistance (Fisher et al., 1995), virulence (Aoyama et al., 1991) and biofilm formation (Danhorn et al., 2004; Monds et al., 2001).

PhoB is a soluble protein consisting of a 123-residue N-terminal regulatory domain joined by a five-residue linker to a 101-residue C-terminal winged-helix DNA-binding domain. PhoB has been reported to exist primarily as a monomer and phosphorylation greatly enhances dimerization (Fiedler and Weiss, 1995; McCleary, 1996). The previously reported crystal structure of the unactivated regulatory domain (PhoBN) exhibited the typical receiver domain doubly-wound α/β fold with an unusual placement of helix α4 (Solà et al., 1999). PhoBN crystallized as a two-fold symmetric dimer using the α1-β5-α5 face. The physiological significance of this dimer, whether reflective of a propensity for dimerization in the inactive state or indicative of the dimerization interface promoted by phosphorylation, was unknown. Structures of the PhoB effector domain (PhoBC) have been solved by NMR (Okamura et al., 2000) and X-ray crystallography (Blanco et al., 2002), in the free and DNA-bound forms. Both structures showed a tandem head-to-tail arrangement of PhoBC consistent with the direct repeat sequences of pho box DNA recognition half-sites (Makino et al., 1996).

We report here structural characterization of the first inactive/active receiver domain pair from the OmpR/PhoB subfamily with distinct structures in the two states. NMR solution studies together with crystallographic analyses indicate that both unactivated and activated PhoB receiver domains form dimers with two-fold rotational symmetry, but that these dimers are distinct and utilize different dimerization interfaces. Together with the previously reported structure of the effector domain bound to DNA (Blanco et al., 2002), these structures reveal quaternary interactions that define the conformation of the active transcription factor and provide evidence for a mechanism of regulation in which upon activation, the receiver domains dimerize with two-fold rotational symmetry while the effector domains, attached through flexible linkers, bind to pho box DNA recognition elements in a tandem head-to-tail orientation, implying a loss of orientational constraints between the two domains. Based on strict sequence conservation of the dimerization determinants in the active state, this model seems to be conserved throughout the OmpR/PhoB subfamily, and specifically in this subfamily.

Results

The α1-α5 dimer of inactive PhoBN

The structure of unactivated PhoBN was solved using experimental phases from SAD data at 2.4 Å resolution. There is one molecule in the asymmetric unit and it forms a dimer with another crystallographic symmetry related molecule using the face formed by helix α1, the β5-α5 loop, and the N-terminus of helix α5 (Figure 1a). The protein crystallized in a different space group under different conditions than those of the previously solved structure (Solà et al., 1999). The current structure has been refined to an R-factor of 0.25. The dimer superimposes well with the previous structure with an r.m.s. deviation of 1.4 Å for all Cα atoms. This same dimer interface has also been observed in another crystal form of inactive PhoBN (Solà et al., 1999). The repeated observation of this dimer interface under different crystallization conditions strengthens the hypothesis that the dimer is physiologically relevant. Dimerization using this interface was surprising because dimerization of PhoB is associated with activation (Fiedler and Weiss, 1995), and in the majority of receiver domains of other RRs, the “functional region” undergoing maximum structural perturbation upon activation is the α4-β5-α5 face.

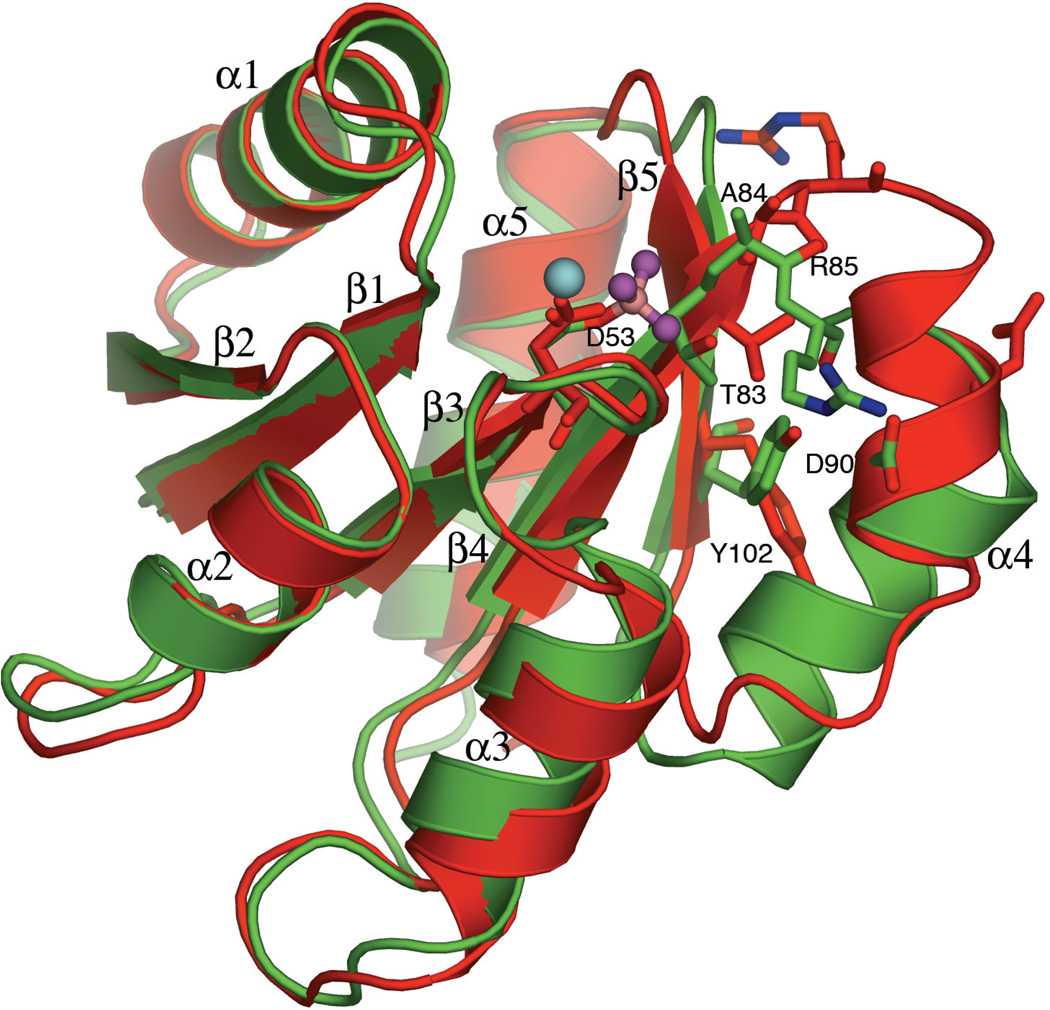

Figure 1.

Crystal Structures Show Different Dimers for Inactive and Active Regulatory Domains of PhoB. (A) Inactive PhoBN dimerizes using the α1–α5 interface. Inactive PhoBN is red; the dimer interface is beige. (B) Active PhoBN dimerizes using the α4-β5-α5 interface. Active PhoBN is green; the dimer interface is blue; and active site ligands are shown as spheres with magnesium in cyan, beryllium in pink, and fluorides in magenta. Figures were created using Pymol (http://pymol.sourceforge.net/).

Solution studies of inactive PhoBN

Inactive PhoBN exhibits elution consistent with a 14 kDa monomer during size exclusion chromatography but shows evidence of weak dimerization by analytical ultracentrifugation and dynamic light scattering (unpublished results). NMR experiments were performed to further characterize the oligomeric state and symmetry of PhoBN. The theoretical number of crosspeaks in an HN-15N HSQC (Kay et al., 1992) spectrum for monomeric 125-residue PhoB receiver domain is 129. The same number of crosspeaks would be expected for a two-fold symmetric dimer, as the corresponding residues in the two protomers would have a similar chemical environment, whereas a significantly larger number of crosspeaks would be expected for a dimer without rotational symmetry, as the residues at the interface in one protomer would have a different chemical environment than the corresponding residues in the other protomer. The number of crosspeaks observed in the HSQC spectrum for inactive PhoBN is 124 (Figure 2), consistent with the presence of a monomer or a symmetric dimer in solution. This number of HN-15N amide resonances was confirmed by three-dimensional HNCO experiments (Muhandiram and Kay, 1994) ruling out the presence of overlapping peaks.

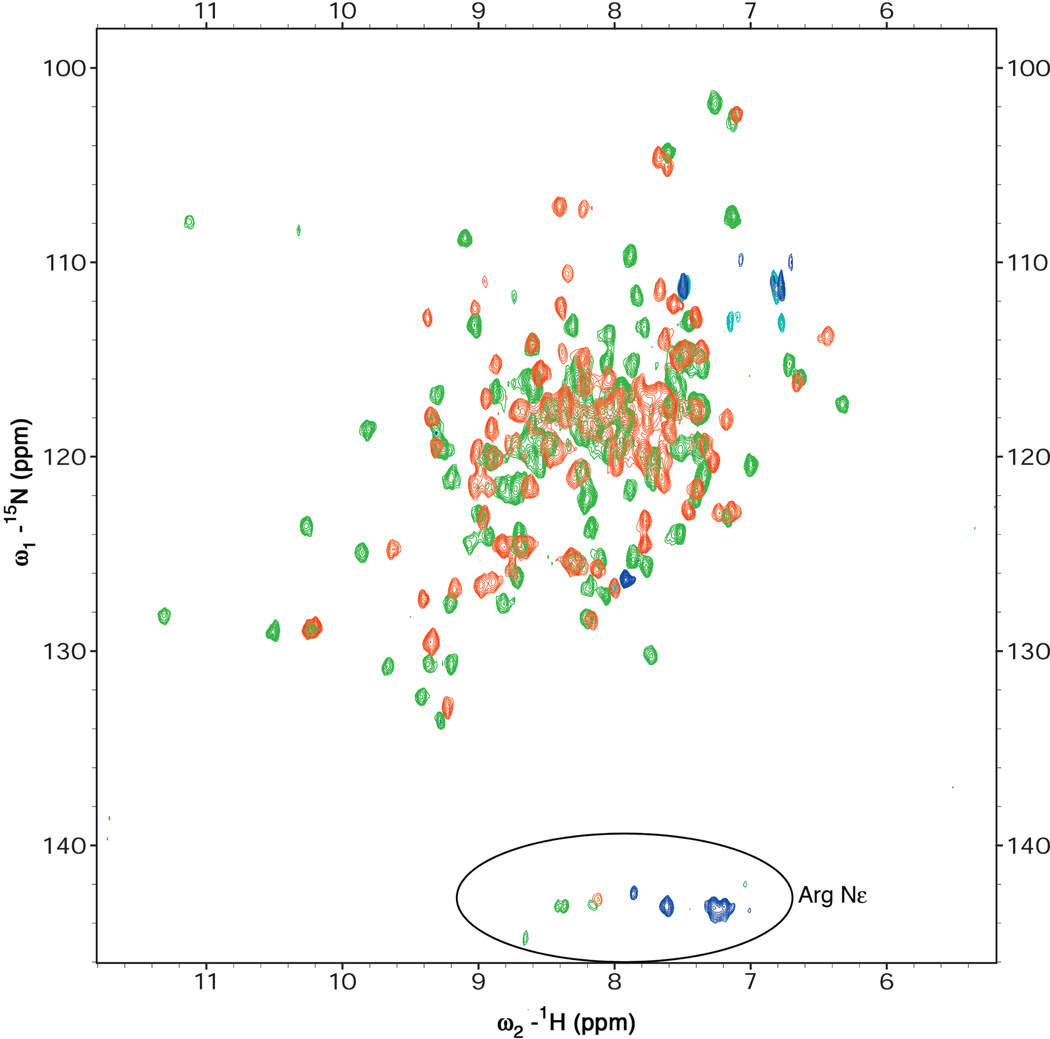

Figure 2.

HN-15N HSQC Spectra of Inactive and Active Regulatory Domains of PhoB. The number of peaks observed in the HSQC spectra are 124 and 128 for inactive (red) and active (green) PhoBN, respectively, both corresponding to monomers or two-fold symmetric dimers. At NMR concentrations, both proteins exist as symmetric dimers (see text). The large differences in the spectra of inactive and active PhoBN suggest that the structures of the two dimers are significantly different.

TROSY-HSQC (Pervushin et al., 1997) spectra were also recorded at different concentrations of PhoBN (1.5 mM to 0.1 mM). At least nine peaks clearly exhibited progressive changes in chemical shifts with dilution (Figure 3), indicating that under these conditions the domain exhibits an equilibrium between different oligomeric states (presumably monomer and dimer). The presence of a single resonance instead of multiple distinct resonances through this concentration-dependent equilibrium demonstrates that this equilibrium is fast on the NMR timescale (i.e. in the lifetime τ ≪ 100 ms). The distribution of these oligomeric states was also affected by ionic strength. Increasing the NaCl concentration to 300 mM at 0.5 mM protein concentration shifted the equilibrium even further toward the form observed at lower protein concentrations (presumably monomer), than the distribution observed at 100 mM NaCl for 0.1 mM PhoBN. This illustrates the importance of solution conditions when quantifying protein-protein interactions for RRs or other macromolecules with weak interactions. From these experiments, it was concluded that in solution, unactivated PhoBN exists as a symmetric dimer in fast equilibrium with a monomer. In 100 mM NaCl at concentrations of PhoBN above 0.75 mM the HSQC pattern is stable, implying that the majority of the population is in the state favored by higher protein concentrations, presumably a dimer. Thus at a concentration of 1 mM PhoBN studied in Figure 2, unactivated PhoBN exists primarily as a two-fold symmetric dimer, consistent with the structure observed by crystallographic analysis.

Figure 3.

Dilution Experiments of Inactive PhoBN. Successive dilutions of inactive PhoBN from 1.5 mM to 0.1 mM cause a progressive shift in some peaks indicating a fast monomer-dimer equilibrium on the NMR timescale (i.e. τ ≪ 100 ms). A section of the TROSY-HSQC spectrum is shown, with the inset zoomed on one of the resonances progressively shifting with decreasing concentration. Crosspeaks for 1.5 mM protein are shown in blue, for 0.75 mM in green, for 0.375 mM in yellow, and for 0.1 mM in red.

The α4-β5-α5 dimer of active PhoBN

Beryllium fluoride, a phosphoryl analog (Yan et al., 1999), was used to generate a stable activated form of PhoBN for structural studies. BeF3−-activated PhoBN was crystallized under identical conditions as unactivated PhoBN, except for the presence of BeCl2, MgCl2 and NaF used to activate the protein. The morphology and space group of these crystals were different from those of unactivated PhoBN crystals in spite of identical crystallization conditions, stressing that the different crystals in the inactive and active states are not a result of crystallization conditions, but reflective of changes caused by activation. The asymmetric unit contains three PhoBN molecules, two (chains B and C) forming a two-fold symmetric dimer using the α4-β5-α5 face (Figure 1b), and the third (chain A) forming the same dimer with a crystallographic symmetry related molecule.

Active site of active PhoBN

Density for the Mg2+ and BeF3− complex non-covalently bound to the active site Asp53 is clearly seen in the Fobs-Fcalc difference map (Figure 4). The octahedral coordination of Mg2+ is satisfied by F1 from BeF3−, the side chain carboxyl oxygens of Asp10 and Asp53, the main chain carbonyl oxygen of Met55, a water molecule hydrogen bonded to Asp10, and another water molecule hydrogen bonded to Glu9 and Glu11. The conserved Lys105 is involved in salt bridges with Glu9, F3 of BeF3− and a water-mediated bridge with Glu11. The conserved Thr83 involved in the activation mechanism in other RRs is in an inward orientation, forming a hydrogen bond to the F2 of BeF3−. The rotation of Thr83 is accompanied by a rotation of the backbone N of the next residue Ala84, which forms a hydrogen bond with F3.

Figure 4.

The Active Site of BeF3−-activated PhoBN. A stereo view of a difference electron density map (Fobs-Fcalc) calculated at 2 Å with omission of the Mg2+, BeF3− and active site water molecules from the model is shown in blue, contoured at 3σ. Waters and the catalytic Mg2+ are shown as red and cyan spheres, respectively. The protein and BeF3− complex are shown in stick representation; beryllium is pink and fluorides are magenta (associations within the non-covalent BeF3− complex are shown as bonds for clarity).

Conformational changes in active PhoBN

The conformation of active PhoBN is similar to the structures of other activated receiver domains with respect to the orientation of key residues involved in the propagation of conformational change to the functional face and the positioning of secondary structural elements. Activation at Asp53 at the tip of β3 is accompanied by rotation of residues in the β3-α3 loop and movement of α3 toward the active site. The β4-α4 loop undergoes major rearrangement, with Arg85, involved in making contacts with the β5-α5 loop in the unactivated PhoBN structure, undergoing a drastic 180° flip, and a displacement of Cα by 6.15 Å. In the structure of active PhoBN, Arg85 is involved in stabilizing interactions with helix α4, forming a salt bridge with Asp90. The conserved switch residue Tyr102 in β5 rotates from an inward gauche+, to an inward trans conformation, concerted with the inward rotation of Thr83. The main chain carbonyl oxygen of Arg85 forms a hydrogen bond with the -OH of Tyr102, which stabilizes the extended conformation of the β4-α4 loop. These changes are correlated with a significant rearrangement in the position of helix α4, the β4-α4 loop and the α4-β5 loop (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Conformational Changes in PhoBN upon Activation. The greatest conformational changes upon activation occur in the β4–α4 loop, the α4 helix and the α5-β5 loop. The important switch residues Thr83 and Tyr102, residues Ala84 and Arg85 in the β4–α4 loop, residue Asp90 in helix α4 and active site residue Asp53 are shown in stick representation. The inactive protein is red and the active protein is green. Active site ligands are shown in ball-and-stick representation; Mg2+ is cyan, beryllium is pink and fluorides are magenta.

The position of helix α4 in the structure of inactive PhoBN is different from that seen in other receiver domain structures. This helix is known to be intrinsically unstable in other receiver domains such as CheY (Bellsolell et al., 1994) and NtrC (Volkman et al., 1995), and contributes little or nothing to the hydrophobic core of the protein. In active PhoBN, it adopts a position that is closer to the structures of other activated receiver domains. The helix extends from Glu87 to Thr97, as opposed to Gly86 to Gly94 in unactivated PhoBN. In activated PhoBN, helix α4 shifts toward the C-terminus and rotates by almost 100°, occupying the space vacated by rotation of Tyr102 to the trans rotamer. The rotation of the helix exposes two hydrophobic residues: Val92, which is the only residue from α4 that contributes to the hydrophobic core in the inactive protein, and Ile95. These residues, along with the aliphatic portions of other residues on the α4-β5-α5 face, comprise a hydrophobic patch that is centered within the dimer interface of the activated protein. The rotation of α4 in the active protein repositions Arg91, allowing it to participate in a salt bridge in the dimer.

Solution studies of active PhoBN

Active PhoBN exists as a dimer in solution with a Kd ~20-fold less than that of the inactive PhoBN dimer, as demonstrated by biochemical studies (Fiedler and Weiss, 1995; McCleary, 1996) and by size exclusion chromatography and analytical ultracentrifugation (unpublished results). The number of crosspeaks observed in the HN-15N HSQC spectrum, and confirmed by a 3D HNCO experiment is 128 (Figure 2), consistent with the two-fold symmetric dimer seen in the crystal structure. The HSQC spectrum of PhoBN activated in the presence of excess ammonium hydrogen phosphoramidate and MgCl2 showed an identical pattern of crosspeaks as that obtained for the BeF3−-activated protein (data not shown), confirming that BeF3− acts as a phosphoryl analog to activate PhoB.

Dimer interface of active PhoBN

The α4-β5-α5 dimer interface of activated PhoBN buries a surface area of ~890 Å2 per protomer. The interface is more extensive and polar in composition than the interface of the inactive dimer which buries ~560 Å2, and is composed primarily of hydrophobic residues. The interacting surfaces of the active protomers form a small hydrophobic core surrounded by an extensive network of hydrogen bonds and water bridges. The interface of active PhoBN is composed of four salt bridges across the dimer interface (Arg91-Glu111, Glu96-Lys117, Asp100-Arg122, Asp101-Arg115) three hydrophobic residues (Val92, Leu95, Ala114) clustered in a hydrophobic patch, and four hydrogen-bonds per protomer (Figure 6). All of these residues involved in the salt-bridges and hydrophobic patch are completely conserved in the OmpR/PhoB subfamily and notably, are not conserved in other RR subfamilies.

Figure 6.

Stereo View of the α4-β5-α5 Interface of Active PhoBN. The residues involved in salt bridge and hydrophobic interactions at the interface are completely conserved in, and only in, the OmpR/PhoB subfamily of RRs. Residues involved in salt bridges are shown as sticks, and the hydrophobic residues are shown as spheres. The two protomers of the dimer are colored orange and green. Salt bridges are shown as dotted lines.

Heteronuclear-NOE (Li and Montelione, 1994) spectra for inactive PhoBN showed at least three arginine HNε resonances that have negative NOEs indicating disordered side chains (Figure 7). Upon activation, all arginine HNε resonances become positive, suggesting that they are ordered. It is likely that these are the arginines that are involved in the salt bridges at the α4-β5-α5 interface observed in the crystal structure.

Figure 7.

HetNOE Spectra of Inactive and Active PhoBN. Negative resonances for HNεof arginines in the spectrum of inactive PhoBN, indicating disordered arginines, become positive upon activation, indicating order, possibly due to involvement in salt bridges at the dimer interface of the active protein. (A) For inactive PhoBN, positive resonances are colored red and negative resonances are colored blue; for active PhoBN, positive resonances are colored green and no negative resonances are observed. (B) 1D slices through the arginine HNε region of the HetNOE spectrum of inactive PhoBN show positive and negative resonances (top), whereas for activated PhoBN, all arginine HNε resonances are positive (bottom).

Discussion

Activation-induced conformational changes

The extent and nature of structural changes induced by phosphorylation differs among receiver domains of different RRs, although most of them undergo perturbation in a common region including the β4-α4 loop and the α4 helix. NtrC undergoes a substantial change in the α4 region, involving a register shift as well as rotation about the helical axis, exposing hydrophobic residues (Kern et al., 1999). FixJ and DctD undergo relatively small changes tilting α4 away from the active site (Birck et al., 1999; Park et al., 2002), while Spo0F and CheY undergo small changes moving α4 toward the active site (Gardino et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2001). Phosphorylation of PhoBN induces conformational changes similar to those observed in NtrC.

Tyrosine102, which is one of the key switch residues in the activation mechanism, has been observed in three different rotameric states in structures of different receiver domains. The trans position with an inward orientation, in which the −OH group points toward the N-terminus of helix α4, is usually associated with an active protein. The gauche− (−OH points outward from the domain, exposed to the solvent) and gauche+ (−OH points toward the C-terminus of helix α4) conformations are associated with proteins in the inactive state. In most cases, the inward gauche+ conformation of tyrosine in inactive proteins (Bacillus subtilis PhoP (Birck et al., 2003), E. coli PhoB (Solà et al., 1999), T. maritima DrrD (Buckler et al., 2002), E. coli apo-NtrC (Volkman et al., 1995), Mg2+-bound E. coli CheY (Bellsolell et al., 1994)) is correlated with an unusual position of α4, significantly different than its position in the active state or in the inactive state with tyrosine in the gauche− conformation. The two available full-length structures of inactive OmpR/PhoB subfamily members exhibit different rotameric states of the conserved tyrosine. In DrrD, the tyrosine exists in a gauche+ conformation and makes no contact with the C-terminal domain, while in DrrB, tyrosine is in a gauche− conformation, pointing outward, and makes extensive contacts including a hydrogen bond with a conserved Asp/Asn in the C-terminal domain. The current model of phosphorylation-induced conformational propagation focuses on two states characterized by the conserved tyrosine in outward (inactive) or inward (active) positions. The high correlation between the unusual placement of the intrinsically unstable helix α4 and the gauche+ conformation of the conserved tyrosine switch residue in the inactive state suggests that there is a prevalent third state, possibly in equilibrium with the other two states.

Relevance of the dimer α1–α5

Phosphorylation-induced oligomerization is a common theme in the OmpR/PhoB subfamily of RRs and appears to provide a mechanism for enhanced DNA binding and transcriptional regulation. However, the order and affinity of oligomerization before and subsequent to phosphorylation varies among subfamily members. ArcA transitions from a dimer in the inactive state to an octamer in the active state (Jeon et al., 2001), PmrA is a dimer in both states (Wösten and Groisman, 1999), while in the absence of DNA, OmpR does not exhibit detectable dimerization in either state (Aiba and Mizuno, 1990). PhoBN transitions from a weak dimer to a tighter dimer upon activation. We have shown that the inactive and active dimers of PhoBN are distinctly different, a feature that may be specific to PhoB within the OmpR/PhoB subfamily.

Several factors suggest the relevance of the dimer of inactive PhoBN observed in the crystal structures. Previously reported two-hybrid analysis demonstrated the propensity for interaction of inactive PhoBN domains (Fiedler and Weiss, 1995). Analytical ultracentrifugation (unpublished results) and concentration-dependent shift of resonances in NMR experiments (Figure 3) with unactivated PhoBN both indicate an equilibrium between monomer and dimer in solution. In this study, both unactivated and activated PhoBN were crystallized under similar conditions, ruling out the possibility that the crystallization conditions selected one form over the other. Additionally, the same α1–α5 dimer interface of inactive PhoBN has been observed in three different crystal forms (Solà et al., 1999). Interestingly, the inactive regulatory domain of B. subtilis PhoP (Birck et al., 2003), the ortholog of E. coli PhoB, crystallized as an asymmetric dimer, distinct from the active state symmetric dimer that we believe to be common to all OmpR/PhoB subfamily members. Perhaps alternate inactive state dimers are a specific feature of “PhoB-like” proteins.

The physiological role of the inactive dimer is yet unknown. It is important to note that the affinity of the inactive dimer measured in vitro for inactive PhoBN and PhoB (unpublished data) is weak and inconsistent with a significant population of dimer in vivo where concentrations of PhoB are expected to be in the low micromolar range. However, it is possible that intracellular macromolecular crowding effects or localization due to interactions with DNA and/or the kinase PhoR might promote dimerization of inactive PhoB despite the low affinity estimated in vitro. When cells are grown in media replete with phosphate, the cellular levels of PhoB are very low which would favor an inactive monomeric structure. However, after cells have been starved for phosphate, they contain high levels of PhoB. When these starved cells are reintroduced to high phosphate levels the formation of an inactive dimer might play an important role in attenuating the phosphate response.

Dimerization of inactive PhoB might affect its activities in several different ways. For example, dimerization might either enhance or inhibit phosphoryl transfer from the dimeric kinase PhoR. Additional effects can be envisioned if dimerization of the regulatory domains is considered in the context of the full-length protein. The domain arrangement in inactive full-length PhoB is unknown, and the current data are insufficient to provide an unambiguous model. There are two structures available for inactive proteins in the OmpR/PhoB subfamily: DrrB with an extensive interface between the N- and C-terminal domains, and DrrD with a small interface between the two domains. The inward gauche+ rotamer of Tyr102 and the unusual position of helix α4 in inactive PhoBN are consistent with the lack of a domain interface as observed in DrrD. However, the high degree of conservation of residues that form the central hydrogen bond at the inter-domain interface of DrrB (the receiver domain switch residue and an Asn/Asp residue in the effector domain β-sheet platform, equivalent to Tyr102 and Asp140 in PhoB) suggests that a tightly packed domain interface may be common in inactive proteins from the OmpR/PhoB subfamily. Whether domain orientations in the inactive PhoB dimer are modeled on DrrB or DrrD, the C-terminal domains project in opposite directions, distant from each other and incompatible with binding to direct repeat DNA recognition elements (Figure 8). This model also suggests that the inactive dimer might be capable of promoting DNA looping by binding to distant DNA recognition sites. Additionally, formation of the DNA-binding incompetent α1–α5 dimer might play a role in release of PhoB from DNA upon dephosphorylation.

Figure 8.

Model of Phosphorylation-Induced Activation in the OmpR/PhoB Subfamily. In the active state, believed to be common to all OmpR/PhoB subfamily members, the receiver domains form a two-fold symmetric dimer while the DNA-binding domains bind to DNA with tandem symmetry. Inactive PhoB exists in equilibrium between a monomer and dimer. The inactive α1–α5 dimer, specific to PhoB, provides an additional means of inhibition by positioning the effector domains in opposite directions, incompatible with tandem DNA binding. Inactive PhoBN is shown in red, active PhoBN in green, the α1–α5 interface of the inactive dimer in beige, the α4-β5–α5 interface of the active dimer in blue, the DNA-binding domain in grey, and the recognition helix in pink. Full-length inactive PhoB was modeled by positioning the two domains of PhoB as they exist in the structure of DrrB.

Based on the above described models, the regulatory domain could inhibit the effector domain by two means: dimerization of the regulatory domains could provide a means of inhibition of DNA binding in the inactive protein by orienting the effector domains in opposite directions making them incompatible with binding to DNA direct repeats, or the regulatory domain could inhibit the effector domain by directly interacting with it in a DrrB like fashion, and locking it in a mode incompatible with tandem DNA binding. It is also possible that the two domain arrangements represented by DrrB and DrrD are in equilibrium in the inactive protein as mentioned earlier.

Model of phosphorylation dependent activation

Activated PhoBN forms a two-fold symmetric dimer using the α4-β5-α5 face. The dimer is similar to that seen for the receiver domain of MicA (RR02), an OmpR/PhoB subfamily member which was crystallized in the absence of an activation agent but is believed to represent an active state induced by crystallization conditions (Bent et al., 2004). The interface is composed of several polar and non-polar residues that are highly conserved throughout the OmpR/PhoB subfamily, suggesting that this mode of dimerization is common to all members in this subfamily. Indeed, the same mode of dimerization is also seen in the structures of activated receiver domains of T. maritima DrrD, DrrB (Robinson and Stock, unpublished results) and E. coli KdpE, TorR (Toro and Stock, unpublished results), ArcA (Toro and Stock, in press) and PhoP (Bachhawat and Stock, unpublished results), all from the OmpR/PhoB subfamily. The only potential exception to this mode of dimerization reported to date is that postulated for B. subtilis PhoPN. The receiver domain of B. subtilis PhoP crystallized using an asymmetric dimer interface in the inactive state, and the structure was proposed to be representative of the active state dimer on the basis of mutational studies in which mutation of an arginine in helix α5 was shown to disrupt formation of the active dimer (Birck et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2003). Notably, this arginine, which corresponds to Arg115 of E. coli PhoB, is also a crucial part of the two-fold symmetric α4-β5-α5 interface of the active OmpR/PhoB dimers, and the mutation would be expected to disrupt this interface as well. We believe that the asymmetric dimer observed in crystals of inactive PhoPN is an alternative inactive state dimer, structurally distinct from, but perhaps functionally analogous to the α1–α5 dimer of inactive E. coli PhoBN. We predict that activated B. subtilis PhoP dimerizes in a fashion similar to active PhoBN and other OmpR/PhoB subfamily members.

The structures of the active PhoBN dimer and the PhoBC dimer bound to DNA together define the active complex of PhoB bound to DNA, a state we postulate to be common to most all members of the OmpR/PhoB subfamily. The DNA-binding domain of PhoB binds to pho box repeats in a tandem head-to-tail fashion, while the activated receiver domain forms a two-fold symmetric head-to-head dimer. This implies an obligatory lack of interaction between the N- and C-terminal domains upon activation (Figure 8). Although the majority of DNA recognition elements to which the members of OmpR/PhoB subfamily bind have been characterized as tandem repeats, this is a versatile mode of interaction, as a flexible tether linking the domains would allow the effector domains to bind to DNA in any orientation, either head-to-tail or head-to-head as dictated by the DNA sequence or protein-protein interaction specificity between effector domains. While intra-molecular interactions between receiver and effector domains may be an important mode of regulation in the inactive proteins, inter-molecular interactions, specifically promotion of dimer formation, may be the sole function of the phosphorylated receiver domains in OmpR/PhoB transcription factors.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning

The DNA sequence encoding PhoBN was amplified using PCR from full-length PhoB plasmid pT7PhoB obtained from McCleary, W.R (McCleary, 1996). This DNA fragment was inserted into the Nde1 and BamH1 restriction sites of the T7-based vector pJES307 to yield plasmid pEF28. The plasmid was amplified in E. coli strain DH5α, purified and transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3). The sequence encodes a 125-residue protein consisting of residues 1–124 from the PhoB sequence and a Gln residue at the C-terminus.

Overexpression and purification

For unlabelled protein, cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 µg/ml of ampicillin at 37 °C to mid-logarithmic phase. PhoBN expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37 °C. To obtain 15N and 13C labeled proteins for NMR studies, transformed cells were grown in isotope-enriched MJ9 medium (Jansson et al., 1996) containing 0.15% w/v (15NH4)2SO4 for 15N-labeling experiment or 0.15% w/v (15NH4)2SO4 and 0.4% w/v 13C-glucose for 15N, 13C-enrichment, and shaken at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0. The cells were then induced in the late-logarithmic phase with 1mM IPTG and shaken at 17 °C overnight. For the selenomethionine-derivatized PhoBN, the plasmid was transformed into a methionine auxotroph strain, and grown as described previously (Hendrickson et al., 1990). The cells were harvested by centrifugation for 30 min at 5,000g, resuspended in buffer A containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 2 mM βME, and centrifuged again. All subsequent steps were carried out at 4 °C. Cells were resuspended in buffer A and lysed by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 35,000g for 1 h to remove cell debris. The supernatant was then subjected to fractionation at 30% saturated (NH4)2SO4, which precipitated >95% of PhoBN along with other proteins. The precipitate was harvested and solubilized in buffer A, then dialyzed overnight against buffer A. The protein was filtered and applied to 5-ml or 70-ml HiTrap Q HP columns (Amersham Biosciences) pre-equilibrated with buffer A. PhoBN was eluted using a 3 column volume gradient from 0 to 1M NaCl. The fractions containing PhoBN were pooled, concentrated and loaded on a Superdex 75 26/60 (Amersham Biosciences) column. The column was equilibrated and run with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM βME for unlabeled protein, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM βME for selenomethionine-labeled protein, and with 20 mM MES (pH 6.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM βME for 15N and 15N, 13C labeled proteins. Fractions containing PhoBN were pooled, and the purity was assessed by Coomassie blue staining subsequent to SDS-PAGE. The protein was >95% pure.

Activation of PhoBN

PhoBN was activated by adding 5.3 mM BeCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, product # 201197), 35 mM NaF and 7 mM MgCl2 to 1mg/ml protein, and concentrating it to the desired concentration using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filtration device, MW cutoff 10 kDa (Millipore). The activation by ammonium hydrogen phosphoramidate (AHP) was achieved by adding 50mM AHP and 20mM MgCl2 to 1mg/ml protein and incubating for 30 min at room temperature.

NMR data collection and processing

NMR samples were prepared in 20 mM MES (pH 6.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5mM βME, 5% D2O, and 95% H2O. NMR data were collected at 20 °C on a Varian Unity Inova 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with 5 mm triple-resonance probes with z-axis-pulsed magnetic field gradients (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA). Protein concentrations ranged from 0.1 to 1.5 mM. The NMR data were analyzed and processed using the programs NMRPipe (Delaglio et al., 1995) and NMRDraw (Delaglio et al., 1995). Sparky version 3.1 (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/home/sparky) was used for peak picking and interactive spectral analysis.

Crystallization and structure determination

Initial conditions for inactive and active PhoBN crystallization were identified using PEG /Ion Screen (Hampton Research, CA). After optimization, crystals were obtained by the hanging drop method for selenomethionine derivatized and native inactive PhoBN, and BeF3−-activated PhoBN by mixing equal volumes of protein solution at 20 mg/ml concentration, and reservoir solution containing 25% PEG 3350, and 0.2 M NaSCN and incubating at room temperature. Crystals appeared in two days. The inactive PhoBN crystals were cryoprotected by transferring the crystals to a solution containing 30% PEG 3350, 0.2M NaSCN, 7% glycerol and 15% ethylene glycol (cryo1), and flash-freezing them directly in a 100 K nitrogen cryostream. The cryoprotectant for the active PhoBN crystals contained cryo1 + 2% sucrose + 5.3 mM BeCl2, 35 mM NaF and 7 mM MgCl2 (to maintain full occupancy of BeF3− in the frozen crystals).

For selenomethionine-derivatized inactive PhoBN crystals, multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) data were collected at X4A beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY) at Selenium peak anomalous, inflexion, and high-energy remote wavelengths based on XAFS scans, but no Selenium sites could be found due to weak anomalous signal. The selenomethionine derivatized crystals were then soaked in 5mM K2PtCl4 in cryo1 for 30 minutes and flash-frozen. Single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) data were collected at the Pt peak wavelength (1.07177 Å) based on an XAFS scan. The crystals belong to the space group P6122 with unit cell dimensions of a = b = 60.861 Å, c = 152.047 Å, corresponding to one molecule of inactive PhoBN per asymmetric unit. Data were processed and scaled with Denzo (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997) and Scalepack (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Three Pt sites were clearly identified using SAD phasing protocol in Crystallography and NMR System software suite (Brünger et al., 1998) (CNS) using data to 2.5Å. Phase ambiguity was resolved with maximum likelihood density modification by solvent-flipping in CNS, which yielded excellent quality electron density maps. The model was built manually in XtalView (McRee, 1999) interspersed with iterative cycles of refinement by positional refinement and simulated annealing in CNS. The model was only partially refined to final resolution of 2.4 Å and has Rcryst/Rfree = 0.25/0.29. It contains 122 amino acids, 3 Pt atoms, and 6 water molecules.

Data were collected for native crystals of BeF3−-activated PhoBN at 0.97176 Å wavelength. The crystals belong to space group P43212 with unit cell dimensions of a = b = 77.869 Å, c = 109.071 Å, corresponding to three molecules of active PhoBN per asymmetric unit. The structure was solved using data from 15 -3 Å by molecular replacement using Phaser (Storoni et al., 2004) integrated with the CCP4i (SERC (UK) Collaborative Computational Project, 1994) interface, using the structure of inactive PhoBN without the loops, helix α4 and strand β5 as the search model. The model was converted to an alanine model by removing all the side chains and was manually rebuilt by iterative cycles of simulated annealing, positional refinement, temperature factor refinement and rebuilding using XtalView, CNS version 1.1 and Refmac 5.2.0005 (Murshudov et al., 1997) until convergence. Non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) was used for density modification and for removing model bias in the initial cycles of refinement till the Rcryst dropped to 24%, after which the three protein chains (A, B and C) were built individually. The final model was refined to 1.9 Å and has Rcryst/Rfree = 0.19/0.24. The final model contains 359 amino acids, 3 BeF3− ions, 3 Mg2+ atoms and 180 water molecules (see Table 1 for details). Residues 44 and 45 in chain B in the α2-β3 loop were not built due to poor density in the region. From PROCHECK analysis 94% of the residues appear in most favorable regions, and 6% occur in allowed regions. Figures were created using Pymol (http://pymol.sourceforge.net). Chain A was used for making all figures, except figure 6 in which the interface shown is between chains B and C. The salt bridge between Glu96 and Lys117 was not observed in the dimer formed by chain A.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Crystal Data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Inactive PhoBN | Active PhoBN | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.07177 | 0.97176 |

| Space group | P6122 | P43212 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 60.86, 60.86, 152.05 | 77.87, 77.87, 109.07 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30-2.4 | 30-1.9 |

| Rsymb | 0.09 (0.50)a | 0.08 (0.64) |

| I / σI | 22.41 (5.5) | 18.4 (2.8) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.3 (97.6) | 93.7 (86.4) |

| Redundancy | 14.36 (12.65) | 11.7 (5.5) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 30-2.4 | 30-1.9 |

| No. reflections (work/test) | 10832/1189 | 19432/2135 |

| Rc / Rfree | 0.25/0.29 | 0.19/0.24 |

| No. atoms | ||

| Protein | 957 | 2,850 |

| Ligand/ion | 3 | 15 |

| Water | 0 | 180 |

| B-factors | ||

| Protein | 45.97 | 23.448 |

| Ligand/ion | 78.0 | 40.47 |

| Water | - | 32.35 |

| R.m.s deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0092 | 0.0155 |

| Bond angles (°) | 2.54 | 1.56 |

Numbers for highest resolution bin are shown in parenthesis.

Rsym = ∑|I − <I>|/∑I, where I = observed integrated intensity and <I>=average integrated intensity obtained from multiple measurements.

R = ∑||Fo| − |Fc|| / ∑|Fo|, where |Fo| and |Fc| are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, Rfree is equivalent to R, but is calculated using a 10% disjoint set of reflections set aside prior to refinement.

Coordinates

The atomic coordinates and structure factors for active PhoBN have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (accession code 1ZES).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gaetano T. Montelione for helpful discussions and guidance for the NMR experiments. We thank Timothy Mack for analytical ultracentrifugation analyses, and Ti Wu for help with protein purification. We thank the staff at beamline X4A at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory for technical assistance. We thank Dr. W. R. McCleary for providing the full-length PhoB plasmid pT7PhoB. This work was supported by grant R37GM047958 from the US National Institutes of Health to A.M.S. and by an NMR Core Facilities Support Award from the Cancer Institute of New Jersey to G.T.M. A.M.S. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Competing interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- Aiba H, Mizuno T. Phosphorylation of a bacterial activator protein, OmpR, by a protein kinase, EnvZ, stimulates the transcription of the ompF and ompC genes in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:19–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80626-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama T, Takanami M, Makino K, Oka A. Cross-talk between the virulence and phosphate regulons of Agrobacterium tumefaciens caused by an unusual interaction of the transcriptional activator with a regulatory DNA element. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1991;227:385–390. doi: 10.1007/BF00273927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baikalov I, Schröder I, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Grzeskowiak K, Gunsalus RP, Dickerson RE. Structure of the Escherichia coli response regulator NarL. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11053–11061. doi: 10.1021/bi960919o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellsolell L, Prieto J, Serrano L, Coll M. Magnesium binding to the bacterial chemotaxis protein CheY results in large conformational changes involving its functional surface. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;238:489–495. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent CJ, Isaacs NW, Mitchell TJ, Riboldi-Tunnicliffe A. Crystal structure of the response regulator 02 receiver domain, the essential YycF two-component system of Streptococcus pneumoniae in both complexed and native states. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:2872–2879. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2872-2879.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birck C, Chen Y, Hulett FM, Samama JP. The crystal structure of the phosphorylation domain in PhoP reveals a functional tandem association mediated by an asymmetric interface. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:254–261. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.254-261.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birck C, Mourey L, Gouet P, Fabry B, Schumacher J, Rousseau P, Kahn D, Samama J-P. Conformational changes induced by phosphorylation of the FixJ receiver domain. Structure Fold. Des. 1999;7:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco AG, Sola M, Gomis-Ruth FX, Coll M. Tandem DNA recognition by PhoB, a two-component signal transduction transcriptional activator. Structure. 2002;10:701–713. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00761-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler DR, Zhou Y, Stock AM. Evidence of intradomain and interdomain flexibility in an OmpR/PhoB homolog from Thermotoga maritima. Structure. 2002;10:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Meyerowitz EM. Eukaryotes have "two-component" signal transducers. Res. Microbiol. 1994;145:481–486. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Birck C, Samama JP, Hulett FM. Residue R113 is essential for PhoP dimerization and function: a residue buried in the asymmetric PhoP dimer interface determined in the PhoPN three-dimensional crystal structure. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:262–273. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.262-273.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhorn T, Hentzer M, Givskov M, Parsek MR, Fuqua C. Phosphorus limitation enhances biofilm formation of the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens through the PhoR-PhoB regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:4492–4501. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4492-4501.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic S, Goudreau PN, Xu Q, Stock AM, West AH. Structural basis for methylesterase CheB regulation by a phosphorylation-activated domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:1381–1386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler U, Weiss V. A common switch in activation of the response regulators NtrC and PhoB: phosphorylation induces dimerization of the receiver modules. EMBO J. 1995;14:3696–3705. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SL, Jiang W, Wanner BL, Walsh CT. Cross-talk between the histidine protein kinase VanS and the response regulator PhoB. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:23143–23149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.23143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardino AK, Volkman BF, Cho HS, Lee SY, Wemmer DE, Kern D. The NMR solution structure of BeF3−-activated Spo0F reveals the conformational switch in a phosphorelay system. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkides CJ, McEvoy MM, Casper E, Matsumura P, Volz K, Dahlquist FW. The 1.9 Å resolution crystal structure of phosphono-CheY, an analogue of the active form of the response regulator, CheY. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5280–5286. doi: 10.1021/bi9925524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson WA, Horton JR, LeMaster DM. Selenomethionyl proteins produced for analysis by multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD): a vehicle for direct determination of three-dimensional structure. EMBO J. 1990;9:1665–1672. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson M, Li YC, Jendeberg L, Anderson S, Montelione BT, Nilsson B. High-level production of uniformly 15N- and 13C-enriched fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;7:131–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00203823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon Y, Lee YS, Han JS, Kim JB, Hwang DS. Multimerization of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated ArcA is necessary for the response regulator function of the Arc two-component signal transduction system. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:40873–40879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay LE, Keifer P, Saarinen T. Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- Kern D, Volkman BF, Luginbuhl P, Nohaile MJ, Kustu S, Wemmer DE. Structure of a transiently phosphorylated switch in bacterial signal transduction. Nature. 1999;40:894–898. doi: 10.1038/47273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Cho HS, Pelton JG, Yan D, Berry EA, Wemmer DE. Crystal structure of activated CheY. Comparison with other activated receiver domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:16425–16431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Brannigan JA, Muchová K, Barák I, Wilkinson AJ. Phosphorylated aspartate in the structure of a response regulator protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:9–15. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Montelione GT. Overcoming solvent saturation-transfer artifacts in protein NMR at neutral pH. Application of pulsed field gradients in measurements of 1H-15N Overhauser effects. J. Magn. Reson. B. 1994;105:45–51. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Wurgler-Murphy SM, Saito H. A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature. 1994;369:242–245. doi: 10.1038/369242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino K, Amemura M, Kawamoto T, Kimura S, Shinagawa H, Nakata A, Suzuki M. DNA binding of PhoB and its interaction with RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;259:15–26. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino K, Shinagawa H, Amemura M, Kawamoto T, Yamada M, Nakata A. Signal transduction in the phosphate regulon of Escherichia coli involves phosphotransfer between PhoR and PhoB proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;210:551–559. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary WR. The activation of PhoB by acetylphosphate. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;20:1155–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee DE. XtalView/Xfit-A versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J. Struct. Biol. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monds RD, Silby MW, Mahanty HK. Expression of the Pho regulon negatively regulates biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aureofaciens PA147-2. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;42:415–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhandiram DR, Kay LE. Gradient-enhanced triple-resonance three-dimensional NMR experiments with improved sensitivity. J. Magn. Reson. B. 1994;103:203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H, Hanaoka S, Nagadoi A, Makino K, Nishimura Y. Structural comparison of the PhoB and OmpR DNA-binding/transactivation domains and the arrangement of PhoB molecules on the phosphate box. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:1225–1236. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota IM, Varshavsky A. A yeast protein similar to bacterial two-component regulators. Science. 1993;262:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.8211183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276(part A):307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Meyer M, Jones AD, Yennawar HP, Yennawar NH, Nixon BT. Two-component signaling in the AAA+ ATPase DctD: binding Mg2+ and BeF3− selects between alternate dimeric states of the receiver domain. FASEB J. 2002;16:1964–1966. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0395fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wuthrich K. Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson VL, Wu T, Stock AM. Structural analysis of the domain interface in DrrB, a response regulator of the OmpR/PhoB subfamily. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4186–4194. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.14.4186-4194.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SERC (UK) Collaborative Computational Project, N. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solà M, Gomis-Rüth FX, Serrano L, González A, Coll M. Three-dimensional crystal structure of the transcription factor PhoB receiver domain. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:675–687. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storoni LC, McCoy AJ, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast rotation functions. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2004;60:432–438. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman BF, Nohaile MJ, Amy NK, Kustu S, Wemmer DE. Three-dimensional solution structure of the N-terminal receiver domain of NtrC. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1413–1424. doi: 10.1021/bi00004a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz K. Structural conservation in the CheY superfamily. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11741–11753. doi: 10.1021/bi00095a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner BL. Gene regulation by phosphate in enteric bacteria. J. Cell. Biochem. 1993;51:47–54. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240510110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wösten MM, Groisman EA. Molecular characterization of the PmrA regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:27185–27190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Cho HS, Hastings CA, Igo MM, Lee SY, Pelton JG, Stewart V, Wemmer DE, Kustu S. Beryllofluoride mimics phosphorylation of NtrC and other bacterial response regulators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14789–14794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]