Abstract

Our previous work found that perceived control over life was a significant predictor of the quality of diet of women of lower educational attainment. In this paper, we explore the influence on quality of diet of a range of psychological and social factors identified during focus group discussions, and specify the way this differs in women of lower and higher educational attainment. We assessed educational attainment, quality of diet, and psycho-social factors in 378 women attending Sure Start Children’s Centres and baby clinics in Southampton, UK. Multiple-group path analysis showed that in women of lower educational attainment, the effect of general self-efficacy on quality of diet was mediated through perceptions of control and through food involvement, but that there were also direct effects of social support for healthy eating and having positive outcome expectancies. There was no effect of self-efficacy, perceived control or outcome expectancies on the quality of diet of women of higher educational attainment, though having more social support and food involvement were associated with improved quality of diet in these women. Our analysis confirms our hypothesis that control-related factors are more important in determining dietary quality in women of lower educational attainment than in women of higher educational attainment.

Keywords: educational attainment, diet, disadvantage, self-efficacy, perceived control

Women with lower levels of educational attainment tend to have poorer quality diets than women of higher educational attainment (Roos, Johansson, Kasmel, Klumbiene, & Prättälä, 2000; Robinson et al., 2004; Hart, Tinker, Bowen, Longton, & Beresford, 2006) Poor quality diets may have long-term implications for the health of women and their children (Barker, 1995). Despite this imperative, there are very few properly evaluated, effective interventions that aim to improve the diets of women from disadvantaged populations (Anderson, 2007). This may be because we understand too little about factors that affect the diets of disadvantaged women to intervene effectively.

Focus group discussions suggested that women of lower educational attainment may have poorer quality diets because they lack support from family members for eating healthily, they have some ambiguous beliefs about the benefits of healthy eating, they lack sufficient money to buy healthy food, and they find less pleasure in food preparation and eating (Barker et al., 2008a; Lawrence et al., 2009). A strong theme emerging from the focus group discussions was that women of lower educational attainment seemed to lack a sense of general self-efficacy and control over their lives in general, and their diets in particular. Lack of social support for eating healthily, lack of money for food, and low general self-efficacy appeared to undermine women’s sense of control over their lives and their food choices.

The psycho-social factors identified in the focus group discussions have all been shown before to be independent predictors of aspects of quality of diet in various populations. In a systematic review of observational studies, greater social support was found to predict increased fruit and vegetable consumption (Kamphuis et al., 2006). Belief that eating a healthy diet had long term benefits, increased the amount of fruit and vegetables consumed amongst 295 French men and women (Bihan et al., 2010). People living in the US who lack enough money for food are more likely than others to be unable to meet their recommended daily intakes of essential nutrients (Rose, 1999). Our previous research found that women who reported less pleasure in cooking and eating were less likely to eat fruit and vegetables (Barker, Lawrence, Woadden, Crozier, & Skinner, 2008b). Low general self-efficacy and perceived control have been found to be strong predictors of poorer health and the adoption of fewer health-promoting behaviours including eating healthily (Leganger & Kraft, 2003), and have been proposed as mediators of the relationship between educational attainment and health (Ross & Wu, 1995).

A previous analysis of data presented in this paper suggested that perceived control may be a more significant influence on the quality of diets of women of lower educational attainment than on those of women of higher educational attainment (Barker et al., 2009). Though sense of control varied amongst women of higher educational attainment, this variation was not associated with differences in quality of diet as it was amongst women of lower educational attainment. This is consistent with other research which found that the relationship between perceptions of control and health outcomes was particularly strong in people from low income groups (Lachman & Weaver, 1998).

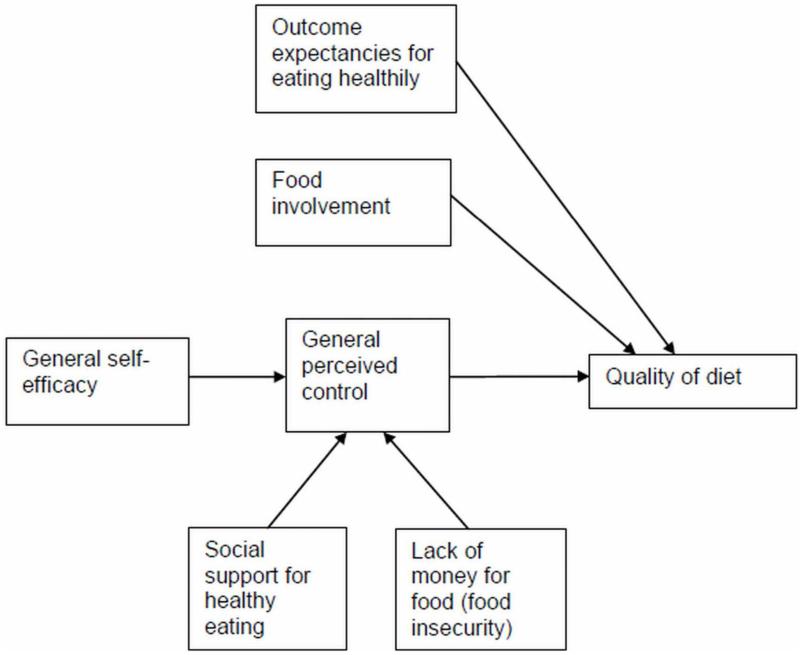

We now wish to examine whether there are differential effects of other key psycho-social factors on the diets of women with lower and higher educational attainment. Our focus group work suggested that the effects of low general self-efficacy, lack of social support for healthy eating and lack of money for food on quality of diet would be mediated by perceived control over life. We have previously published work that suggests beliefs in the value of healthy eating (outcome expectancies) and pleasure in cooking and eating, described as food involvement, may also have direct, independent effects on quality of diet (Lawrence et al., 2009; Barker et al., 2008b). Together, these suppositions suggest the model of influence described in Figure 1. We hypothesise that these psycho-social factors will have a stronger association with quality of diet in women of lower rather than higher educational attainment, and that the model in Figure 1 will therefore be more predictive of variation in quality of diet in women of lower rather than higher educational attainment. We set out to test this hypothesis in data from women living in Southampton, UK.

Figure 1.

Hypothesised pathways between psycho-social factors and quality of women’s diet.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were 378 women attending children’s play sessions and baby clinics run by Sure Start Children’s Centres in 19 locations around Southampton. They were recruited over a six-month period from June to November 2007. A sample size of 253 women was estimated to give 90% power to detect a difference of 0.2SD in prudent diet score per 1SD difference in perceived control score. The decision to over-recruit was made to ensure adequate representation of women of all levels of educational attainment.

Measures

A structured questionnaire was developed guided by the focus group discussions (Barker et al., 2008a; Lawrence et al., 2009). This contained a measure of quality of diet (Crozier et al., 2010) and validated scales to assess factors identified as potential influences on food choice. Women were also asked to report their age at time of interview, and the number of children they had living at home with them. Educational attainment was defined in six groups according to the woman’s highest level of academic qualification. Examinations for General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSEs) are generally taken at 16 years, Advanced Level (A Levels) at 18 years, and Higher National Diploma (HNDs) and degrees thereafter.

Clothes’ size

Participants were asked what clothes’ size they normally tried on when buying clothes. This was intended as a proxy measure of body size; it has been shown to correlate strongly with indices of adiposity such as BMI (Han, Gates, Truscott, & Lean, 2005), and has the advantage of being non-intrusive and possible to administer in a public setting. Clothes’ size was measured as a potential confounder of the effect of educational attainment on diet.

Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)

Quality of diet was assessed using an administered 20-item FFQ (Crozier et al., 2010) that recorded how often in the past month the women ate each of 20 selected foods. Possible responses ranged from never to more than once a day. The foods listed on the FFQ were those that characterised the ‘prudent’ dietary pattern, the key pattern of diet that we have previously described in women taking part in the Southampton Women’s Survey (Robinson et al 2004). The prudent dietary pattern describes compliance with current healthy eating recommendations; high scores for this pattern identify diets that are characterised by frequent consumption of fruit, vegetables and wholemeal bread, whilst low scores are associated with low consumption of these foods and high consumption of chips, added sugar and white bread. Prudent diet scores from the 20-item FFQ are highly correlated with those from the full 100-item questionnaire (r = 0.94) (Crozier et al., 2010).

Psycho-social scales

Social support for healthy eating was assessed with six items adapted from a validated scale (Ball, Crawford, & Mishra, 2006). Response categories are the same as those used in the FFQ. Originally the scale asked about consumption of “healthy low-fat foods”. This was changed to “healthy foods” as the focus of this study was balance and variety in diet rather than low-fat (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.60). Food insecurity, an indication of whether women had enough money for food, was measured using the short form of the Household Food Security Scale (Blumberg, Bialostosky, Hamilton, & Briefel, 1999), (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88). To assess women’s perceived control over life we used a short form of the measure used in the Whitehall II study, (Marmot et al., 1991; Bobak, Pikhart, Rose, Hertzman, & Marmot, 2000). The three health-related items were dropped from this original scale so that it reflected only a general sense of control over life, making it more comparable with the scale measuring general self-efficacy. (Cronbach’s alpha statistic = 0.63.) The General Self-efficacy Scale is a 10-item scale measuring the general sense that one can perform novel or difficult tasks, or cope with adversity in various domains of human functioning (Jerusalem & Schwarzer, 1979). (Cronbach’s alpha statistic = 0.85.)

The outcome expectancies scale used in this study consists of 12 items specific to assessing the consequences of eating a more healthy diet (Renner et al., 2008). In the version used in this study, respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with each item. (Cronbach’s alpha statistic positive outcome expectancies sub-scale = 0.73; negative sub-scale = 0.66.) The Food Involvement Scale was developed to measure the priority respondents give to the acquisition, preparation, cooking, eating and disposal of food (Bell & Marshall, 2003). The total score represents the individual’s level of food involvement. (Cronbach’s alpha statistic = 0.63.)

Procedure

Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Southampton School of Medicine ethics committee. The researchers liaised with Children’s Centre staff to arrange convenient times to attend play sessions and baby clinics, where information sheets were distributed to all women attending. After allowing them time to read the sheets, women were then asked if they would like to complete a questionnaire with the researcher. Those who agreed signed consent forms. We recorded no information from the few who refused to take part.

Statistical analysis

A prudent diet score was calculated for each woman using her standardised frequency of consumption of each of the 20 foods in the FFQ, multiplied by the coefficient for that food produced by principal components analysis of the SWS FFQ (Crozier et al., 2010). The prudent diet scores were then standardised to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. Responses on the psycho-social scales were summed to create a score for each woman. Where necessary, scoring was reversed so that higher scores represented more social support, higher food involvement, etc.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for correlations between the prudent diet score and all the independent variables, excepting food insecurity, where Spearman’s correlations were used.. Tests of the significance of relationships between educational attainment and all other variables were calculated using Spearman’s rank correlations. Linear regression analysis was used to estimate the effect of educational attainment on prudent diet score.

We carried out a path analysis to explore the fit of the theoretical model presented in Figure 1. To examine differences in the predictors of a prudent diet, the proposed model was tested separately on data from women who had attained up to and including GCSE level qualifications and in those who had attained qualifications above GCSE level. The models were analysed using maximum-likelihood estimation. Model fit was tested using χ2 statistics and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), standardised root mean squared residual (SRMR) and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). The model fit was defined as acceptable when fit indices met the following criteria: TLI and CFI ≥ .95, SRMR ≤ .08 and RMSEA ≤ .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The statistical significance and direction of association of coefficients describing each individual path in the model were checked. Path analyses were done using Mplus 5.2 (Muthen & Muthen, 2008, Los Angeles, USA). All other statistical analyses were done with Stata 10.1 (StataCorp, 2008, CollegeStation, TX, USA). We used a significance level of p ≤ .05 for all statistical tests.

Results

Table 1 gives the women’s age, number of children living at home, clothes’ size, levels of all psychological and social scales, and prudent diet scores separately for women of lower and higher educational attainment. Fifty-six percent of the women had qualifications up to and including GCSE level, and 12% had degrees or equivalent qualifications. Women of lower educational attainment (those with qualifications up to and including GCSEs) were significantly younger and had more children than women of higher educational attainment, though there was no difference between the groups in their clothes’ size. Women of lower educational attainment tended also to have less social support for healthy eating, were more likely to be food insecure, had lower general self-efficacy, perceived control, positive outcome expectancies and food involvement, higher negative outcome expectancies, and lower prudent diet scores. Educational attainment alone accounted for 16% of the variation in the prudent diet scores of these women. Younger women were more likely to have lower prudent diet scores (rs = 0.22, p < 0.001). Having more children living in the home and wearing a larger clothes’ size were not associated with differences in prudent diet scores.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 378 women interviewed in Southampton, UK by educational attainment.

| Educational attainment up to and including GCSE (n = 212) |

Educational attainment above GCSE (n = 166) |

Test for trend (p)* |

|

|

| |||

| Age in years (median (IQR)) | 26 (22 - 30) | 30 (26 – 33) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Number of children living at home | n (%) | n (%) | < 0.001 |

| 0 | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| 1 | 91 (43) | 98 (60) | |

| 2 | 66 (31) | 42 (25) | |

| 3 | 35 (17) | 17 (10) | |

| 4+ | 15 (7) | 5 (3) | |

|

| |||

| Clothing size (UK sizing) | n (%) | n (%) | 0.68 |

| 6 to 8 | 7 (3) | 7 (4) | |

| 8 to 10 | 34 (17) | 31 (19) | |

| 10 to 12 | 55 (27) | 41 (25) | |

| 12 to 14 | 41 (20) | 32 (19) | |

| 14 to 16 | 29 (14) | 26 (16) | |

| 16 to 18 | 17 (8) | 16 (10) | |

| 18 to 20 | 16 (8) | 8 (5) | |

| 20 and above | 7 (4) | 5(3) | |

|

| |||

| Social support for healthy eating - median (IQR) |

13 (10 – 17) | 15 (13 – 20) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Food insecurity - median (IQR) | 0 (0 – 2) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| General perceived control (mean (SD)) | 25.6 (2.5) | 27.5 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| General self-efficacy (mean (SD)) | 25.7 (5.0) | 27.9 (4.5) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Outcome expectancies – positive (mean (SD)) |

17.3 (2.5) | 18.1 (2.5) | = 0.003 |

|

| |||

| Outcome expectancies – negative (mean (SD)) |

14.0 (2.0) | 13.2 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Food involvement (mean (SD)) | 42.1 (4.7) | 44.4 (4.5) | < 0.001 |

|

| |||

| Prudent diet score (mean standardised z score (SD)) |

−0.59 | 0.65 | < 0.001 |

Test for trend treated variables as continuous.

Correlations between all variables except dress size, and between them and prudent diet score, were calculated separately for women of lower and higher educational attainment (Table 2). Dress size was excluded from this analysis because it was unrelated to quality of diet. Overall, there were fewer significant correlations between these variables and prudent diet score in women of higher educational attainment than there were in women of lower educational attainment.

Table 2.

Correlations between prudent diet and all psychological scores for women of lower educational attainment (below the diagonal) and women of higher educational attainment (above the diagonal).

| Social support for health eating |

Food insecurity # |

General perceived control |

General self- efficacy |

Outcome expectancie s - positive |

Outcome expectancie s - negative |

Food involve- ment |

Prudent diet score |

Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support for healthy eating | - | − 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.19* | 0.17* | − 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.23** | −0.11 |

| Food Insecurity # | − 0.01 | - | −0.35** | − 0.24** | −0.09 | 0.13 | −0.10 | − 0.10 | −0.15 |

| General perceived control | 0.09 | − 0.31** | - | 0.48** | 0.05 | − 0.41** | 0.21** | 0.08 | −0.02 |

| General self-efficacy | 0.18** | −0.22** | 0.34** | - | 0.06 | − 0.35** | 0.18* | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Outcome expectancies (+ve) | 0.22** | − 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.24** | - | 0.10 | 0.16* | 0.06 | −0.03 |

| Outcome expectancies (−ve) | 0.00 | 0.22** | −0.12 | −0.02 | 0.20** | - | −0.15 | − 0.09 | −0.03 |

| Food involvement | 0.10 | − 0.08 | 0.18** | 0.24** | 0.16* | −0.06 | - | 0.19* | 0.04 |

| Prudent diet score | 0.19** | − 0.08 | 0.22** | 0.24** | 0.37** | −0.00 | 0.25** | - | 0.13 |

| Age | −0.06 | −0.14* | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.14* | 0.19 |

Spearman’s correlation coefficients.

p<0.05

p<0.01

Path analysis of educational attainment and quality of diet

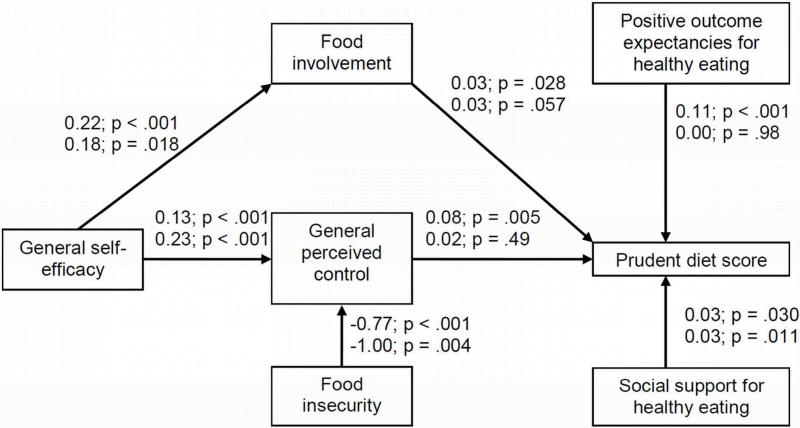

We carried out a path analysis to test the fit of the hypothetical model (Figure 1). Paths in the analysis were set according to those specified by our previous work. The resulting model was first fitted to data from women of lower educational attainment. We then attempted to replicate the best-fit model in data from women of higher educational attainment. All path analyses were adjusted for associations between prudent diet score and age.

The first attempt at a model for women of lower educational attainment showed a poor fit (χ2 = 41.20; df = 16, p < .001; TLI = 0.63; CFI = 0.77; SRMR = 0.07; RMSEA = 0.09 [95% CI: .05;.12]). The path coefficients between social support for healthy eating and general perceived control (coefficient = −0.01; SE = .03; p = .74), and that between negative outcome expectancies and prudent diet score were not significant (coefficient = −0.02; SE = .03; p = .43). These paths were therefore deleted and paths between social support for healthy eating and prudent diet score and between general self-efficacy and food involvement were added, as suggested by substantial modification indices. The result was a better fitting model, shown in Figure 2. The model showed a good fit to the data for women of lower educational attainment (χ2 = 13.04, df = 12, p = 0.37; TLI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; SRMR = .04; RMSEA = 0.02 [95% CI: .00;.074]). Inspection of the path coefficients confirmed that they were significant and in the expected direction (Figure 2). This model explained 21% of the variance in prudent diet scores of women of lower educational attainment.

Figure 2.

Results of path models relating self-efficacy to prudent diet score in women of lower and higher educational attainment. Path coefficients for women of lower educational attainment are given above, and for women of higher educational attainment below. Both models adjusted for age.

We then tested the fit of the model to the data from the higher educational attainment group. Fit indices for the model in the high educational attainment group demonstrated a poor fit (χ2 = 34.04, df = 12, p < 0.001; TLI = 0.54; CFI = 0.75; SRMR = 0.08; RMSEA = 0.11 [95% CI: .07;.15]), and a multigroup model with path coefficients constrained to be the same for women of lower and higher educational attainment showed a significantly worse fit than the unconstrained model (χ2diff = 18.10; dfdiff = 7; p = .012). Inspection of the unconstrained model path coefficients for women of higher educational attainment showed that the path coefficients between general perceived control and prudent diet and between positive outcome expectancies and prudent diet were not significant. Equality constraints for all path coefficients except those two resulted in a non-significant difference in model fit compared to the unconstrained model (χ2diff = 8.76; dfdiff = 6; p = .19). This suggests that the pathways to prudent diet score in the two groups of women differ primarily with regard to a lack of a significant association with perceived control and positive outcome expectancies in women of higher educational attainment. Figure 2 shows the path coefficients for the two groups. We then tested whether the model fit for women of higher educational attainment could be improved by specifying more paths between variables specified in Figure 2. However, inspection of the modification indices suggested that adding theoretically meaningful paths to the model in this group would not substantially improve model fit. This model explained 9% of the variance in prudent diet scores of women of higher educational attainment.

Discussion

The model produced by path analysis broadly supports our hypothesis that control-related psychological factors are associated with quality of diet in women of lower, but not higher, educational attainment. Our model suggests that women of lower educational attainment who had lower general self-efficacy tended also to perceive they had less control over their lives, and that this was associated with having a poorer quality diet. Again in line with our hypothesis, there was a direct association between expecting fewer benefits from healthy eating and poorer quality diet in women of lower educational attainment. This pattern of association was not seen in data from women of higher educational attainment. However, our hypothesis as described in Figure 1 implied that any relationship between level of social support for healthy eating and quality of diet would be mediated by perceived control. We found this not to be the case. Having lower levels of social support for healthy eating was directly and independently associated with poorer quality diet in women of both lower and higher educational attainment.

It is not obvious why psychological factors are more predictive of dietary quality in women of lower educational attainment. It may be that there are environmental factors that somehow protect the diets of women of higher educational attainment even when they feel they lack control over their lives. We have no data on this at present, but imagine that women of higher educational attainment may be living in better circumstances, have more money to spend on food and be surrounded by fewer opportunities to eat poor quality food. More of the women of lower educational attainment reported food insecurity than did women of higher educational attainment. Other support for our speculation comes from studies of geographical distribution of fast food outlets. For example, Cummins found there were more fast food restaurants per head of population in deprived neighbourhoods of Scotland and England, and that this number increased linearly with increasing levels of deprivation (Cummins, McKay, & Macintyre, 2005). Whilst the behaviour of individuals cannot be determined by examining area-level statistics, the implication is that women living in deprived areas may be faced with more opportunities to eat cheap, takeaway food. Faced with these kinds of environmental challenges, women of lower educational attainment who tend to live in these areas, may have to have higher levels of self-efficacy, a stronger sense of control and believe more strongly in the benefits of healthy eating than women of higher educational attainment in order to maintain a good quality diet. It is known that psychological factors including high self-efficacy enable women of lower educational attainment to be physically active in spite of the socio-economic trend (Cleland, Ball, Salmon, Timperio, & Crawford, 2010). Our model implies that food insecurity (a clear indication of difficult financial circumstances) reduces quality of diet by reducing perceptions of control over life. Lachman and Weaver in their analysis of data from approximately 5000 men and women of middle age, found that having a strong sense of control was associated with better health but that this relationship was particularly strong in people from low-income groups (Lachman et al., 1998). Our data suggest that the effect of control applies to quality of diet as well as to general health.

The role of social support for healthy eating and its influence on quality of diet is one area where our data departed from our hypothesis. One possible explanation is that in using social support for healthy eating with general self-efficacy and perceived control in the same model, we are not combining like with like. Our measure of social support is specific to healthy eating where the measures we used of self-efficacy and perceived control are general. Food insecurity reflects a general lack of financial resources in the same way that self-efficacy and perceived control are general measures of internal resources. Hence, we might expect them to be on the same path in determining dietary quality. Social support for healthy eating, on the other hand, is a more specific measure and is therefore more likely to be directly related to quality of diet as we find in the path model for women of both lower and higher educational attainment.

The issue of whether to measure general or specific aspects of psychological and social factors is the subject of some contention. Both general (Kamphuis et al., 2006) and specific (Steptoe et al., 2003) measures of social support have been found to correlate with indices of dietary quality. There are those who maintain that global (or general) control beliefs are more important in predicting people’s health behaviour than domain specific control beliefs, such as those which relate to diet or food choice, because general control beliefs may have more impact on coping abilities especially for vulnerable populations such as our women of lower educational attainment (McKean Skaff, Mullan, Fisher, & Chesla, 2003). Walker reports that Albert Bandura, originator of the construct of self-efficacy, himself denied that self-efficacy only concerned specific behaviours in specific situations. He felt that the concept reflected people’s general belief in their ability to cope with stressors in their lives (Walker, 2001). Leganger and Kraft (2003) found a close correlation between general self-efficacy and specific self-efficacy for eating fruit and vegetables, which they interpreted as an indication that general self-efficacy exerts its influence over behaviour through self-efficacy specific to each health behaviour (Leganger et al., 2003). What we have found suggests that measures of general self-efficacy and control reflect psychological characteristics that are associated with significant differences in specific dietary behaviour.

Our previous work has suggested that having lower food involvement was associated with being of lower educational attainment and having poorer quality diet (Barker et al., 2008b). This was confirmed by the analysis we describe here showing a direct and independent effect of food involvement on quality of diet. However, we also found that having lower general self-efficacy was associated with having a lower level of food involvement. This association was present in data from women of both higher and lower educational attainment. One interpretation of this association is that a woman’s feelings of low general self-efficacy feed into a sense of incompetence in handling and preparing food as they do in other areas of life. This lack of confidence in food preparation may engender lack of interest and lead to giving food a lower priority, which in turn reduces quality of diet. Unlike all the other psychological variables, and alone with social support, food involvement had a significant association with quality of diet in women of both lower and higher educational attainment, though the significance of the association was marginal in women of higher educational attainment. Though having a low sense of self-efficacy is more common in women of lower educational attainment, it is not unique to them, and our model suggests it has the same effect on levels of food involvement in women of lower and higher educational attainment. We conclude from this that giving food, its preparation and consumption, a high priority is universally important in determining the quality of a woman’s diet, and that it varies within groups of people of any level of educational attainment.

Strengths and limitations

This analysis has a number of limitations. Our data are cross-sectional. Relationships between variables cannot therefore be assumed to be causal. Though we can justify our hypothesis and our models, other potential relationships between variables could have been proposed and tested. The fact that the best-fit model of the relationship between psycho-social factors and quality of diet only explained 21% of the variance in prudent diet scores of women of lower educational attainment suggests that there are other important factors that we have not accounted for. However, it is not clear what these might be. They may be factors which reflect aspects of the wider environment. Our FFQ was a shortened version of a longer instrument. Because prudent diet scores are strongly influenced by the foods that characterise this dietary pattern, we developed a short FFQ that included only the key foods to assess this axis of variation in diet. We have previously shown that there are high correlations between prudent diet scores derived from the shortened version of the FFQ with scores derived from the original longer version. Importantly the scores from both FFQs show comparable associations with the nutrient biomarker red-cell folate (Crozier et al., 2010). We are therefore confident that the variations in prudent diet scores in the study we report here provide meaningful information about the women’s compliance with the prudent dietary pattern, and their adherence to healthy eating recommendations.

Our study population are not necessarily representative of the general population of women of childbearing age in Southampton. In order to ensure adequate representation of women of lower educational attainment, we recruited women attending Sure Start Children’s Centres. These centres are intended to serve the more disadvantaged populations in Southampton. Despite this strategy, our study population represent the whole range of educational attainment, and though we do not have a large sample size, the effects we describe are not the result of statistical artifact.

Conclusions

We have found that there is a relationship between psychological factors and the quality of diet of women of lower educational attainment, such that lower self-efficacy and perceived control, and expecting fewer benefits from eating healthily predict poorer quality diet. There are different relationships between psychological factors and diet amongst women of higher educational attainment.

Our findings have implications for the design of interventions to improve the diets of women of lower educational attainment. They pinpoint a number of social and psychological factors we would have to address in such an intervention, and suggest that these would differ from factors that would have to be addressed in an intervention to improve the diets of women of higher educational attainment. First, we would need to improve the general self-efficacy of women of lower educational attainment and therefore their sense of control. Interventions that specifically target self-efficacy for eating fruit and vegetables have been shown to lead to increases in fruit and vegetable consumption in a low-income population (Steptoe, Perkins-Porras, Rink, Hilton, & Cappucio, 2004). Our findings also suggest we would need to increase women’s levels of social support for healthy eating, their level of food involvement and their belief that healthy eating would benefit them if we are to improve the quality of their diets. There are hints from the literature that food involvement and belief in the benefits of healthy eating could be addressed by cooking skills and nutrition education courses (Wrieden et al., 2007; Baird, Cooper, Margetts, Barker, & Inskip, 2009). However, there is less precedent for interventions specifically designed to increase social support for healthy eating. The most common attempt to provide social support to those trying to improve their diet is to offer them peer-led support. A recent review identified the effectiveness of interventions that involved nutrition education by peers of the intervention participants (Baird et al., 2009). The staffing of Sure Start Children’s Centres (Belsky et al., 2006) is based on the idea that peer-led support is the most effective method of improving the health and welfare of disadvantaged populations.

With this in mind, we are currently running an intervention designed to increase self-efficacy and perceptions of control over health and health behaviours of women attending Sure Start Children’s Centres in Southampton. This intervention is designed to test the hypothesis that increasing their self-efficacy and perceived control will improve the quality of their diets. Staff working in Sure Start Children’s Centres are receiving training in behaviour change skills that will enable them to better support women in making changes to their diets and to the diets of their families. The first data on the effectiveness of this intervention will be available in 2011.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the women who gave up their time to speak to us, staff at Sure Start Children’ Centres in Southampton, and our field workers for helping with the data collection. This study was funded by the Medical Research Council of Great Britain and Danone Institute International. There are no conflicting interests. The research had obtained local ethical approval and was carried out in accordance with universal ethical principles.

Reference List

- Anderson AS. Dietary interventins in low-income women -issues for UK policy. Nutrition Bulletin. 2007;32:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Baird J, Cooper C, Margetts BM, Barker M, Inskip H. Changing health behaviour of young women from disadvantaged backgrounds: Evidence from systematic reviews. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2009;68:195–204. doi: 10.1017/S0029665109001050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Crawford D, Mishra G. Socio-economic inequalities in women’s fruit and vegetable intakes: a multilevel study of individual, social and environmental mediators. Pub Health Nutr. 2006;9:623–630. doi: 10.1079/phn2005897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJP. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. British Medical Journal. 1995;311:171–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker M, Lawrence W, Crozier S, Robinson S, Baird J, Margetts B, et al. Educational attainment, perceived control and the quality of women’s diets. Appetite. 2009;52:631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker M, Lawrence W, Skinner TC, Haslam C, Robinson SM, Barker DJP, et al. Constraints on the food choices of women with lower educational attainment. Pub Health Nutr. 2008a;11:1229–1237. doi: 10.1017/S136898000800178X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker M, Lawrence W, Woadden J, Crozier S, Skinner TC. Women of lower educational attainment have lower food involvement and eat less fruit and vegetables. Appetite. 2008b;50:2–3. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R, Marshall DW. The construct of food involvement in behavioral research: scale development and validation. Appetite. 2003;40:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(03)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Melhuish E, Barnes J, Leyland AH, Romaniuk H, the National Evaluation of Sure Start Research Team Early effects of Sure Start local programmes on children and families: early findings from a quasi-experimental, cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal. 2006;332:1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38853.451748.2F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihan H, Castetbon K, Mejean C, Peneau S, Pelabon L, Jellouli F, et al. Sociodemographic factors and attitudes toward food affordability and health are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in a low-income French population. Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140:830. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.118273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, Briefel RR. The effectiveness of a short form of the household food security scale. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1231–1234. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobak M, Pikhart H, Rose R, Hertzman C, Marmot M. Socioeconomic factors, material inequalities, and perceived control in self-rated health: cross-sectional data from seven post-communist countries. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland V, Ball K, Salmon J, Timperio A, Crawford DA. Personal, social and environmental correlates of resilience to physical inactivity among women from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds. Health Education Research. 2010;25:268–281. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozier SR, Inskip HM, Barker ME, Lawrence WT, Cooper C, Robinson SM. Development of a 20-item food frequency questionnaire to assess a ‘prudent’ dietary pattern among young women in Southampton. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;64:99–104. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2009.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S, McKay L, Macintyre S. McDonald’s restaurants and neighbourhood deprivation in Scotland and England. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:308–310. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han TS, Gates E, Truscott E, Lean MEJ. Clothing size as an indicator of adiposity, ischaemic heart disease and cardiovascular risks. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2005;18:423–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A, Tinker L, Bowen DJ, Longton G, Beresford SAA. Correlates of fat intake behaviours in participants in the Eating for a Healthy Life study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:1605–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jerusalem M, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale (GSE) 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis MH, Giskes K, de Bruijn G-J, Wendel-Vos W, Brug J, van Lenthe FJ. Environmental determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among adults: a systematic review. British Journal of Nutrition. 2006;96:620–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Weaver SL. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:763–773. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence W, Skinner TC, Haslam C, Robinson S, Inskip HM, Barker DJP, et al. Why women of lower educational attainment struggle to make healthier food choices: the importance of psychological and social factors. Psychol Health. 2009;24:1003–1020. doi: 10.1080/08870440802460426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leganger A, Kraft P. Control constructs: do they mediate the relation between educational attainment and health behaviour? J Health Psychol. 2003;8:361–372. doi: 10.1177/13591053030083006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Davey Smith G, Stansfield S, Patel C, North F, Head J, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. The Lancet. 1991;337:1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKean Skaff M, Mullan JT, Fisher L, Chesla CA. A contextual model of control beliefs, behaviour and health: Latino and European Americans with Type 2 diabetes. Psychol Health. 2003;18:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Renner B, Kwon S, Yang BH, Paik KC, Kim SH, Roh S, et al. Social-cognitive predictors of dietary behaviors in South Korean men and women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15:4–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03003068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SM, Crozier SR, Borland SE, Hammond J, Barker DJP, Inskip HM. Impact of educational attainment on the quality of young women’s diets. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;58:1174–1180. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos G, Johansson L, Kasmel A, Klumbiene J, Prättälä R. Disparities in vegetable and fruit consumption: European cases from the north to the south. Pub Health Nutr. 2000;4:35–43. doi: 10.1079/phn200048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D. Economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in the United States. Journal of Nutrition. 1999;129:517S–520S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.517S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Wu C. The links between education and health. Am Soc Rev. 1995;60:719–745. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Perkins-Porras L, McKay C, Rink E, Hilton S, Cappucio FP. Psychological factors associated with fruit and vegetable intake and with biomarkers in adults from a low-income neighborhood. Health Psychology. 2003;22:148–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Perkins-Porras L, Rink E, Hilton S, Cappucio FP. Psychological and social predictors of changes in fruit and vegetable consumption over 12 months following behavioural and nutrition education counseling. Health Psychology. 2004;23:574–581. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. Control and the Psychology of Health: theory, measurement and applications. 1st ed. Open University Press; Buckingham: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wrieden WL, Anderson AS, Longbottom PJ, Valentine K, Stead M, Caraher M, et al. The impact of a community-based food skills intervention on cooking confidence, food preparation methods and dietary choices - an exploratory trial. Pub Health Nutr. 2007;10:203–211. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]