Abstract

Neighborhood characteristics have been linked to healthy behavior, including effective parenting behaviors. This may be partially explained through the neighborhood’s relation to parents’ access to social support from friends and family. The current study examined associations of neighborhood characteristics with parenting behaviors indirectly through social support. The sample included 614 mothers of 11–12 year old youths enrolled in a health care system in the San Francisco area. Structural equations modeling shows that neighborhood perceptions were related to parenting behaviors, indirectly through social support, while archival census neighborhood indicators were unrelated to social support and parenting. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and control were related to greater social support, which was related to more effective parenting style, parent-child communication, and monitoring. Perceived neighborhood disorganization was unrelated to social support. Prevention strategies should focus on helping parents build a social support network that can act as a resource in times of need.

Keywords: neighborhoods, social support, parenting, pre-adolescents

Neighborhood characteristics have been linked to outcomes for both adults and youth (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Ross & Mirowsky, 2009), with some characteristics associated with poor health outcomes, such as delinquency and substance use (Byrnes, Chen, Miller, & Maguin, 2007; Frank, Cerda, & Rendon, 2007; 2004; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000), as well as employment outcomes (Holloway & Mulherin, 2004; O'Regan & Quigley, 1996), teen pregnancy (Harding, 2003; South & Crowder, 2010), and academic achievement (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sun, 1999). Neighborhood characteristics have also been related to health problems for adults, such as anxiety, anger, and depression (Ross & Mirowsky, 2009). Parents in particular may face increased difficulties raising children in neighborhoods that may be high-crime, high in disorder, and lacking in resources (Ceballo & McLoyd, 2002). Indeed, neighborhood characteristics have been found to be related to a parents’ use of effective parenting strategies (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Simons, Johnson, Conger, & Lorenz, 1997). A parents’ ability to access social support, including emotional, financial, and in-kind assistance (e.g., babysitting), could also greatly aid their ability to parent their children effectively (Marra et al., 2009; Priel & Besser, 2002). Neighborhood characteristics have been shown to be related to the amount of social support available to parents (Turney & Harknett, 2010), thus potentially affecting parenting behavior. The present study examines the relations between neighborhood characteristics and parenting behaviors, indirectly through associations with social support.

Neighborhood Conceptualizations

The importance of neighborhood characteristics for parenting may differ depending on whether “objective” or subjective appraisals of the neighborhood are measured (Bamaca, Umana-Taylor, Shin, & Alfaro, 2005). Researchers’ definitions of neighborhoods, based upon criterion derived from sources such as the census, do not always correspond to views of residents (O’Neil, Parke, & McDowell, 2001). Residents’ perceptions are arguably more important for their outcomes (Bowen, Bowen, & Cook, 2000; Burton & Jarrett, 2000). This perspective is consistent with contextual approaches that consider context to be socially constructed, and emphasizing the importance of residents’ interpretations (Bronfenbrenner, 1992; Furstenberg & Hughes, 1997; Jessor, Van Den Bos, Vanderryn, Costa, & Turbin, 1995). However, residents’ own perceptions of their neighborhood environment are surprisingly absent from most neighborhood studies (Dahl, Ceballo, & Huerta, 2010).

A specific neighborhood characteristic that can disrupt healthy behavior for residents is social disorganization, which manifests in difficulty maintaining neighborhood social and physical order (Shaw & McKay, 1942). Neighborhood disorganization has been operationalized using a variety of indicators, such as low neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES), the presence of disorder (e.g., abandoned buildings, drug use in the open), crime, and structural or system problems (e.g., police not caring about community problems). Such conditions can interfere with youth and adult behaviors. Conversely, neighborhoods that are socially organized, rather than disorganized, tend to have high levels of collective efficacy, which is described by high social cohesion (e.g., social ties, trust, and reciprocal obligations) and informal social control that support parents’ efforts for healthy youth outcomes (Sampson, Morenoff, & Earls, 1999; Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). The strong social connections in these neighborhoods make use of intergenerational closure, a resource developed by getting to know and exchanging information with parents of their child’s friends (Coleman, 1988; Sampson et al., 1999), in order to share in supporting and controlling neighborhood children (Coleman, 1990; Sampson et al., 1999; Sandefur & Laumann, 1998). Parents in these neighborhoods also benefit from the informal social control present that imposes shared norms on other residents (Sampson et al., 1999). These aspects of social organization are considered to be possible pathways through which neighborhood structural characteristics such as poverty can result in problems for residents (Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003). Socially organized neighborhoods can help to the ease the burden of individual parents in raising their children (Beyers, Bates, Pettit, & Dodge, 2003).

Neighborhoods and Parenting Behaviors

Parenting behaviors, in particular parenting style, parent-child communications, and monitoring, have been shown to be important for healthy youth development and outcomes. Parenting style is characterized by a parent’s behavior on two continuums, control/expectations for behavior and warmth/responsiveness (Baumrind, 1966). Parenting style can be protective against youths’ risky behaviors, such as substance use and delinquency. For example, authoritative parenting style, distinguished by a high degree of control but also high levels of warmth, has been shown to be linked to lower levels of substance use and delinquency as compared to other parenting styles (Newman, Harrison, Dashiff, & Davies, 2008). Likewise, parent-child communication and parental monitoring have been associated with youth development and outcomes. It has been well-documented that parental monitoring, parenting behaviors that provide knowledge and control over children’s activities and companions (Dishion & McMahon, 1998), is strongly protective against risky youths’ behaviors such as alcohol and drug use and misconduct (Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell, & Dintcheff, 2006; Parker & Benson, 2004; Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, Wei, Farrington, & Wikstrom, 2002). Parent-child communication, including discussions with children about daily issues, family values, or problems, has also been shown to be an important protective factor against problem behaviors such as substance use (Kelly, Comello, & Hunn, 2002; Pokhrel, Unger, Wagner, Ritt-Olson, & Sussman, 2008).

Prior studies show that disorganization in neighborhoods can interfere with parents’ use of effective parenting practices (Byrnes, Miller, Chen, & Grube, 2011; Simons et al., 1997). Two elements of parenting style, warmth and harshness/control, may be influenced by neighborhood characteristics. Prior research suggests that low SES neighborhoods and those that are low in resources are related to higher levels of harsh, inconsistent, and more punitive parenting (Kohen, Leventhal, Dahinten, & McIntosh, 2008; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). These relationships may be due to the persistent stress faced by parents living in neighborhoods that are characterized by high crime and/or few resources. One explanation for this relationship is that the distress from living in such environments might disrupt the level of relaxation and energy parents need to engage in warm and non-harsh behavior with their children (Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster, & Jones, 2001). In addition, previous research (Rankin & Quane, 2002; Simons, Johnson, Beaman, Conger, & Whitbeck, 1996) has shown that neighborhoods may affect youths’ problem behavior indirectly through disrupting these parenting behaviors.

Similarly, parental monitoring and parent-child communication also appear to be influenced by neighborhood characteristics. For example, when parents perceive greater neighborhood disadvantage, they are more likely to report lower levels of involvement with and monitoring of their children (Stern & Smith, 1995). Low neighborhood SES is also related to aspects of ineffective parenting such as less parental monitoring, warmth, and communication (Simons et al., 1996; Simons et al., 1997). In contrast, other work found that higher levels of neighborhood disorganization were actually related to greater parental monitoring (Chuang, Ennett, Bauman, & Foshee, 2005). This conflicting finding is consistent with ethnographic studies showing that some parents may feel that increasing supervision and restricting children’s activities are necessary in more disorganized neighborhoods (Burton & Jarrett, 2000; Furstenberg, Cook, Eccles, Elder, & Sameroff, 1999). Conflicting findings may be explained by parents’ increasing their efforts at monitoring, but their efforts being counteracted by disorder present in such neighborhoods.

Although substantial research has shown that neighborhoods can influence a parent’s ability to implement effective parenting strategies, it is also possible that the reverse is true. Parents with more effective parenting strategies may select into less risky neighborhoods. For example, higher SES families are more likely to live in more advantaged neighborhoods, and also to utilize more successful parenting strategies (Bornstein, Hahn, Suwalsky, & Haynes, 2003; Byrnes et al., 2007; Byrnes et al., 2011). In any case with the potential for unobserved heterogeneity, it may be difficult to determine the role of self-selection in observed relationships.

Neighborhoods and Social Support

Neighborhood social organization can assist parents through having neighbors to share in child-rearing duties (Beyers et al., 2003) as well as providing benefits such as greater social support (e.g., emotional, financial, housing, or child care assistance). Neighborhoods may be related to parents’ abilities to access this type of support from friends and family. As described in Wilson’s book, The Truly Disadvantaged (Wilson, 1987), as middle-class minorities followed employment opportunities into the suburbs and moved out of cities, people residing in low-income urban neighborhoods became isolated from successful role models and were left without resources such as playgrounds, libraries, or quality schools. The isolation and lack of opportunities in these neighborhoods put youth at increased risk for poor outcomes.

Turney and Harknett (2010) propose several reasons why neighborhood conditions may prevent access to social support for parents. One reason is that in disadvantaged and isolated neighborhoods, residents are less likely to have a social network of neighbors that they can trust (Ross, Mirowsky, & Pribesh, 2001). This mistrust could make it difficult to form social ties with other residents that parents could depend on for support. Secondly, residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods often lack resources that would allow them to provide support. As such, parents may end up over-burdening the few neighbors that may try to offer assistance, and this burden may be amplified by the parents’ inability to reciprocate due to their own limited resources and multiple stressors. Another alternative is that neighborhoods are related to a lack of social support due to selection processes. People who move into disadvantaged neighborhoods may also be the same people without supportive relationships.

Although many studies have examined individual level predictors of social support (e.g., Eggebeen, 2005; Eggebeen & Hogan, 1990), few have examined the relationships between neighborhood characteristics and social support (Turney & Harknett, 2010). This absence is notable, given the considerable research documenting the importance of social support for health and well-being (see Pierce, Sarason, & Sarason, 1996 for a review), including being protective against psychological distress (Lincoln, Chatters, & Taylor, 2003), depression (Priel & Besser, 2002), and positive relations with effective and responsive parenting behaviors (Marra et al., 2009; Priel & Besser, 2002; Unger & Wandersman, 1988). For example, emotional and instrumental (material or in-kind assistance) social support were both related to improvements in parenting consistency among homeless mothers, as compared to those with less support (Marra et al., 2009). These findings are consistent with proposed theoretical conceptualizations of social support as coping assistance that can provide another source of emotional or instrumental aid if needed to handle stressors (Thoits, 1986).

The few studies that have considered the importance of the neighborhood context for social support have mostly considered moderating relationships. For example, Kotchick, Dorsey, and Heller (2005) found that greater levels of neighborhood stress were related to greater psychological distress in African-American single mothers. In turn, psychological distress was related to less positive parenting. Social support appeared to moderate this relationship such that the relationships between neighborhood stress, distress, and parenting were stronger when social support was low. In another study of African-American single mothers, Ceballo and Mcloyd (2002) found that neighborhood quality moderated the relationship between social support and parenting, so that social support was less beneficial for nurturant parenting behaviors in worse neighborhoods, and the relationship between more social support and less punitive parenting was stronger in higher quality neighborhoods.

However, few studies have examined the possibility that social support is a mechanism through which neighborhood characteristics affect parenting behaviors. One of the few studies to examine direct relationships between the neighborhood context and social support builds a foundation for this concept. Turney and Harknett (2010) found that neighborhood disadvantage and residential stability were related to instrumental support in new mothers. Specifically, mothers living in more disadvantaged neighborhoods received less instrumental support, especially financial support, and those in neighborhoods with more residential stability received more instrumental support.

Hypotheses

The current study examines the relationship of neighborhood characteristics to parenting behaviors indirectly through access to social support. Consistent with past research (Turney & Harknett, 2010) and social disorganization theory (Sampson et al., 1999; Sampson et al., 1997; Shaw & McKay, 1942), it is hypothesized that neighborhood characteristics will be related to the availability of perceived social support. Specifically, perceived neighborhood social cohesion and control are expected to be related to perceptions of increased access to social support, while perceived neighborhood disorganization and archival indicators of neighborhood structural disadvantage are expected to be associated with less perceived social support. The current study builds upon prior work by extending analyses to examine effective parenting behaviors. Further, the current study also extends findings to mothers of pre-adolescent youths, rather than new mothers, as parenting behaviors at this stage have been shown to be important in preventing risky behaviors such as substance use and delinquency (Barnes et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2002). Consistent with theoretical conceptualizations (Thoits, 1986) and prior studies (Marra et al., 2009; Priel & Besser, 2002), it is expected that social support will be related to effective parenting behaviors (i.e., higher levels of authoritative parenting style, communication, and monitoring, and lower levels of authoritarian and permissive parenting styles).

Methods

Sample and Procedures

The present study is part of a larger study regarding the role of having a choice on recruitment, participation, and outcomes in family-based alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) prevention programs in health care settings. The sample included families with at least one family member who was a member of one of four Kaiser Permanente (KP) medical centers in the San Francisco area at the time of the sample draw: Oakland, Walnut Creek, Vallejo, and San Francisco. Families selected were those with an 11–12 year old child, with exclusion criteria excluding families whose targeted child was in current ATOD treatment. Study enrollment included only the child and their mother or female caregiver, although other family members were encouraged to participate in the programs. See Miller et al. (In review) for a detailed description of recruitment procedures.

Baseline enrollment interviews were completed by 614 families, with mother and youth each completing separate and private face-to-face interviews between August 2005 and April 2007. No recruitment was conducted during summer 2006. Families participated in one of two prevention programs, Family Matters (Bauman, Foshee, Ennett, Hicks, & Pemberton, 2001) or Strengthening Families Program (SFP) (Spoth, Redmond, & Lepper, 1999). Of these 614 families, the addresses of 31 families were not able to be geocoded to allow for the collection of archival neighborhood data from the census, either due to incorrect addresses or due to residences in new subdivisions/streets that were not reflected in current maps. Therefore, a total of 583 families were included in analyses. Study procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards at the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (PIRE) and Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (KFRI).

At recruitment, mothers/female guardians in the sample ranged from 25 to 76 years of age (M = 43.88, SD = 6.72), and their children were 11 or 12 years of age (M = 11.5; SD = .51). Household size ranged from 1 to 13 (M = 4.19, SD = 1.27). Descriptive information for the other background control variables, including marital status, mothers’ ethnicity, family income, mothers’ education level, and youths’ gender, are shown in Table 1. As shown in the table, the sample is reflective of an ethnically diverse sample. Mothers were allowed to endorse more than one ethnicity, with 18.2% doing so.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Background Control Variables

| Variable | % |

|---|---|

| Marital status (% Married) | 77.4 |

| Mothers’ ethnicity | |

| White | 60.1 |

| Asian | 16.0 |

| African-American | 14.7 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 13.7 |

| Native American | 2.9 |

| Pacific Islander | 1.2 |

| Unknown | 13.4 |

| Family income | |

| ≤ $40,000 | 11.0 |

| $40,001 to $80,000 | 29.5 |

| $80,001 to $125,000 | 29.3 |

| $125,001 to $150,000 | 11.2 |

| $150,001 to $200,000 | 9.6 |

| $200,001 to $300,000 | 6.2 |

| >$300,001 | 3.2 |

| Mothers’ education | |

| Less than H.S. | 1.7 |

| Graduated H.S. | 7.8 |

| Vocational/business school | 3.0 |

| Some college | 29.7 |

| Graduated college | 27.6 |

| Graduate school | 30.2 |

| Youths’ gender (% female) | 48.7 |

Measures

Neighborhood Perceptions

Neighborhood disorganization

Perceptions of neighborhood disorganized are assessed through mothers’ reports of 28 items adapted from Elliott and colleagues (1983). Mothers indicated on a 5-point scale the degree each was a problem in their neighborhood (not a problem - big problem). Items reflect the following features: (a) social disorder (seven items, e.g., ethnic/cultural groups who don’t get along with each other), (b) structural or system problems (six items, e.g., city officials ignoring problems), (c) physical disorder (three items, e.g., abandoned buildings or houses), and (d) crime/victimization (12 items, e.g., burglaries and thefts in the neighborhood). Scales for each feature were created by summing the applicable items. Good internal reliability exists for the items (Cronbach’s α = .87 for social disorder, .86 for structural problems, .73 for physical disorder, and .92 for crime). A latent variable was created for perceptions of neighborhood disorganization using the four scales as indicators.

Neighborhood collective efficacy

Collective efficacy was assessed with two scales adapted from Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls (1997), measuring two aspects of collective efficacy, social cohesion and social control. Five items adapted from Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls (1997) reflect social cohesion. Items ask how strongly mothers agree with statements such as “people in this neighborhood can be trusted,” and “this is a close-knit neighborhood” (possible responses ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” on a 5-point scale). Cronbach’s alpha is .83. A latent variable representing social cohesion was constructed.

Informal social control was assessed using four items also adapted from Sampson et al. (1997). Mothers reported the likelihood that their neighbors would intervene in different situations such as children writing graffiti on public places/a wall or children showing disrespect to an adult. Possible responses ranged from “very unlikely” to “very likely” on a 5-point scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .85). A latent variable was created to represent social control.

Archival Neighborhood Data

To measure neighborhood characteristics for the census block groups in which the participating families live, census data was collected from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing, which is publicly available from the U.S. Census Bureau. In order to link families to census data for their block group, their addresses were geocoded to determine block group membership. Census data are presented in proportions (i.e., the number of people who make up each characteristic divided by the population of the block group).

Neighborhood structural disadvantage was indicated by variables reflecting low socioeconomic status (SES) and residential instability, as these are commonly examined in neighborhood studies (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Five items commonly used to reflect low SES were used, including the rates of persons below the poverty line, households receiving public assistance, low-income persons, high school dropouts, and female-headed households. Renter-occupied (versus owner-occupied) housing reflected residential instability. A latent variable was created for analyses.

Individual-level Social Support

Four items adapted from Institute for Social and Behavioral Research (2000a) were used to assess mothers’ perceptions of social support. Mothers reported how often they had friends who would provide advice and emotional or other types of support (e.g., financial assistance, a place to stay) on a 5-point scale ranging from “Never” to “Always.” Cronbach’s alpha is .86. A latent variable was created for analyses.

Parenting Behaviors

Parenting style

Items adapted from the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) (Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 2001) were used to measure parenting style. Mothers’ responses to 42 items indicated how true each statement was on a 5-point scale from “never” to “most of the time – almost daily.” Relevant items were averaged to create three scales reflecting authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting, with Cronbach’s alphas of 0.81, 0.85 and 0.75. The scale for authoritarian parenting style consists of 12 items indicating high expectations for child behavior with low levels of warmth. The authoritative parenting style scale consists of 15 items reflecting a high degree of both behavioral expectations and warmth. The permissive parenting style scale consists of 15 items characterizing parenting with few expectations for child behavior but high levels of warmth.

Parent-child communication

Using ten items adapted from Paschall, Ringwalt, and Flewelling (2003), mothers reported their communication with their child regarding issues such as school, friends, concerns, and future goals. Responses were on a 5-point scale (1= Never, 5= Most of the time – Almost daily). Items were averaged to create a summary scale (Cronbach’s α = .79).

Parental monitoring

Five items adapted from Institute for Social and Behavioral Research (2000b) reflect parental monitoring. Mothers responded to items asking how often they know of their child’s activities and companions when away from home. Possible responses ranged from “never” to “always” on a 5-point scale. A monitoring scale was created by averaging the items (Cronbach’s α = .60).

Background Variables

Mothers reported the number of people in their household, their marital status, ethnicity, income, and education. Youth reported their own age and gender.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics provide an overview of neighborhood characteristics, social support, and parenting behaviors. EM estimation was used for missing data imputation. Latent structures for the neighborhood and support measures were examined using Maximum Likelihood (ML) confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) implemented with EQS (Bentler, 1985–2004). ML latent variable structural equation modeling examines associations between neighborhood characteristics, social support, and parenting behaviors, controlling for background characteristics. Lagrange Multiplier (LM) tests and Wald test are used to help modify the models. According to recommendations from Hu and Bentler (1999), the ML-based comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) are used to determine fit of the models. A CFI value over .90 and a RMSEA value ≤.05 were considered indicators of good model fit. Robust estimates of the standard errors are used to adjust for non-normally distributed data.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Table 2 presents means and standard deviations for neighborhood characteristics, perceived social support, and effective parenting behavior variables. Mothers reported on their perceptions of the disorganization (i.e., social disorder, crime/victimization, physical disorder, and structural system problems), social cohesion and control in their neighborhoods. On average, low levels or moderately low levels of disorganization were reported. Greater problem levels of physical disorder and structural/system problems were reported as compared to social disorder and/or crime/victimization. In contrast, neighborhood cohesion and control were perceived as relatively high. Mothers also perceived high levels of social support. Although a wide distribution of neighborhood types were reflected by archival census measures of neighborhood structural disadvantage, on average low levels of disadvantage were found, including low rates of low SES and residential instability.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Constructs

| Minimum | Maximum | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Disorganization | ||||

| Physical disorder | 2.00 | 15.00 | 4.46 | 2.08 |

| Social disorder | 6.00 | 34.00 | 11.15 | 5.15 |

| Structural/system problems | 2.00 | 25.00 | 7.96 | 4.28 |

| Crime/victimization | 7.00 | 54.00 | 16.37 | 7.33 |

| Neighborhood Social Cohesion | ||||

| Trustworthy people in neighborhood | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.00 | 0.95 |

| Close knit neighborhood | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.59 | 1.05 |

| Helpful people in neighborhood | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.99 | 0.85 |

| Neighbors don't get along* | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.07 | 0.77 |

| Neighbors don't share values* | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.56 | 0.97 |

| Neighborhood Social Control | ||||

| Intervene – children skipping school | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.58 | 1.21 |

| Intervene – children spray painting graffiti | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.19 | 1.08 |

| Intervene – children disrespecting an adult | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 1.10 |

| Intervene – fighting in front of house | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.03 | 1.13 |

| Archival Neighborhood Assessments (%) | ||||

| Persons below the poverty line | .00 | 61.64 | 8.22 | 8.94 |

| Households receiving public assistance | .00 | 44.40 | 3.40 | 4.85 |

| Low-income persons | .00 | 75.81 | 13.00 | 11.12 |

| High school dropouts | .00 | 60.55 | 13.12 | 12.55 |

| Female-headed households | .00 | 57.09 | 8.78 | 8.67 |

| Renter-occupied | .00 | 100.00 | 34.84 | 26.51 |

| Social Support | ||||

| Have friends for advice | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.26 | 0.89 |

| Have friends to do things with | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.98 | 0.95 |

| Friends that would help with money/shelter/chores | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.28 | 1.04 |

| Have friends who will listen to my problems | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.45 | 0.80 |

| Parenting Behaviors | ||||

| Permissive parenting style | 1.07 | 4.07 | 2.13 | 0.46 |

| Authoritarian parenting style | 1.00 | 4.08 | 2.07 | 0.51 |

| Authoritative parenting style | 1.73 | 5.00 | 4.39 | 0.44 |

| Parent-child communication | 2.30 | 5.00 | 3.71 | 0.51 |

| Parental monitoring | 3.00 | 5.00 | 4.47 | 0.38 |

Reverse scored

For measures of effective parenting (see Table 2), overall, mothers reported low levels of permissive and authoritarian parenting styles (less effective parenting strategies), reflecting that parents use these strategies rarely (1 or 2 times ever). However, they reported high levels of authoritative parenting (more effective parenting strategy), using this style in between once a week and daily. They also reported moderately high levels of parent-child communication, discussing these issues about once a week, and high levels of parental monitoring, indicating that they know their youth’s activities in between “always” and “most of the time.”

Measurement Model

CFA was used to ascertain whether latent structures conform to expectations. Table 3 presents standardized and unstandardized factor loadings. The final measurement model fit the data well [CFI = .951; RMSEA = .039 (90% CI = .034 – .043)], and accordingly was used as the basis for the latent variable structural model.

Table 3.

Measurement Model

| Indicator | Unstandardized factor loading |

Robust SE |

Standardized factor loading |

Robust t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood Disorganization | ||||

| Physical disorder† | 1.00 | .85 | ||

| Social disorder | 2.70 | .15 | .92 | 17.67 |

| Structural/system problems | 2.00 | .14 | .82 | 14.79 |

| Crime | 3.80 | .22 | .91 | 17.64 |

| Neighborhood Cohesion | ||||

| Trustworthy people in neighborhood† | 1.00 | .87 | ||

| Close-knit neighborhood | .81 | .06 | .65 | 14.04 |

| Helpful people in neighborhood | .75 | .05 | .73 | 16.50 |

| People in neighborhood get along | .51 | .04 | .56 | 12.35 |

| People in neighborhood share values | .60 | .06 | .52 | 9.94 |

| Neighborhood Control | ||||

| Intervene - Children skipping school† | 1.00 | .79 | ||

| Intervene - Children spray-painting graffiti | .93 | .06 | .80 | 16.24 |

| Intervene - Children disrespecting an adult | .87 | .05 | .74 | 16.97 |

| Intervene - Fighting in front of your house | .90 | .06 | .75 | 15.26 |

| Archival Neighborhood Assessments | ||||

| Persons below the poverty line† | 1.00 | .95 | ||

| Households receiving public assistance | .45 | .04 | .79 | 12.76 |

| Low-income persons | 1.19 | .05 | .91 | 26.71 |

| High school dropouts | 1.09 | .08 | .74 | 14.31 |

| Female-headed households | .76 | .06 | .74 | 12.14 |

| Renter-occupied | 2.02 | .15 | .64 | 13.84 |

| Social Support | ||||

| Have friends for advice† | 1.00 | .72 | ||

| Have friends to do things with | 1.09 | .07 | .75 | 15.47 |

| Friends that would help with money/shelter/chores | 1.29 | .09 | .80 | 14.05 |

| Have friends who will listen to my problems | 1.13 | .08 | .91 | 14.46 |

Note.

Unstandardized factor loading was fixed at 1.0. All factor loadings are statistically significant (p < .05).

Structural Equation Modeling

Consistent with the conceptual model, an initial structural model was specified such that parenting behaviors were associated with social support and neighborhood characteristics, controlling for background variables (i.e., number in household, marital status, mothers’ ethnicity, income, and education, youths’ age and gender). All background variables and neighborhood characteristics were allowed to covary with each other, as well as were the outcome parenting variables. Non-significant paths were eliminated from the model. Based on LM tests and conceptual relevance, the following paths between background variables and key constructs were added to the model: relationships between ethnicity, authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles; youths’ age and parental monitoring; and mothers’ education with communication and parental monitoring.

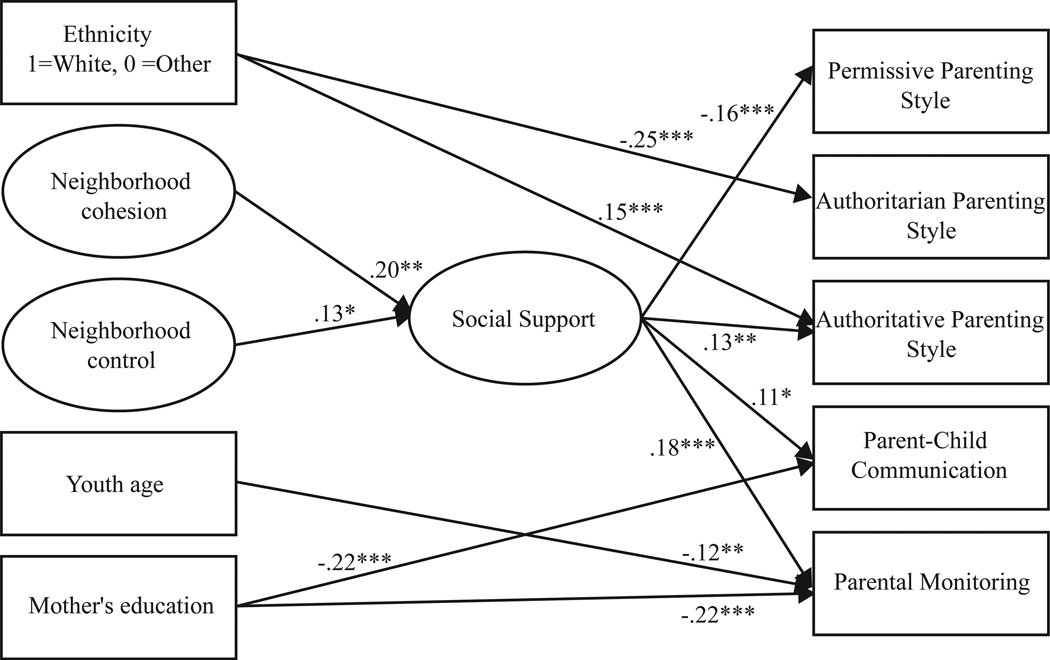

Figure 1 depicts the final structural model, which fit the data well [CFI = .943, RMSEA = .036 (90% CI = .032 – .040). Table 4 also presents the standardized and unstandardized coefficients, robust SE and robust t from the model. Controlling for background demographic variables, results show that neighborhood perceptions are related to parenting behaviors through social support. Archival neighborhood assessments from the census were not significantly related to social support or parenting outcomes. Paths between census variables, social support, and outcomes were subsequently dropped due to non-significance, but census variables remain in the model as controls. Perceptions of greater neighborhood social cohesion and social control were significantly related to higher levels of social support. Neighborhood disorganization was unrelated to social support. In turn, social support was related to four out of the five parenting behaviors examined: permissive parenting style, authoritative parenting style, parent-child communication, and parental monitoring. Support was not related to authoritarian parenting style.

Figure 1.

Final structural model showing the relationships between neighborhood characteristics, individual support, and parenting behaviors. Standardized coefficients are shown. Not shown in the figure are covariances between constructs on the far left side and among outcome variable residuals. Control variables not significantly related to outcomes not shown. Model Fit: CFI = .944, RMSEA = .038 (90% CI = .034 – .042). *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Table 4.

Final Structural Model

| Predictor | Standardized Coefficient |

Unstandardized Coefficient |

Robust SE |

Robust t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permissive Parenting Style | ||||

| Social Support | −.16 | −.11 | .03 | −3.74 |

| R2 = .02 | ||||

| Authoritarian Parenting Style | ||||

| Ethnicity | −.25 | −.26 | .04 | −6.67 |

| R2 = .06 | ||||

| Authoritative Parenting Style | ||||

| Social Support | .13 | .09 | .03 | 2.59 |

| Ethnicity | .15 | .13 | .03 | 4.02 |

| R2 = .04 | ||||

| Parent-child Communication | ||||

| Social Support | .11 | .09 | .04 | 2.14 |

| Mothers’ Education | −.22 | −.09 | .02 | −5.52 |

| R2 = .06 | ||||

| Parental Monitoring | ||||

| Social Support | .18 | .11 | .03 | 3.79 |

| Youth Age | −.12 | −.09 | .03 | −3.12 |

| Mothers’ Education | −.22 | −.07 | .01 | −6.22 |

| R2 = .09 | ||||

| Social Support | ||||

| Neighborhood Cohesion | .20 | .16 | .05 | 2.93 |

| Neighborhood Control | .13 | .09 | .04 | 2.12 |

| R2 = .09 | ||||

In addition, demographic variables were also related to constructs in the model. Specifically, White ethnicity was related to lower levels of authoritarian parenting styles and higher levels of authoritative parenting style. Older youth age and higher mother education were related to lower levels of parental monitoring. Greater mother education was also significantly related to lower levels of parent-child communication.

Discussion

Findings are consistent with the hypothesis that social support could be a mechanism for neighborhood effects on parenting behaviors. Perceived neighborhood characteristics were related to enhanced or limited access to such types of support, and this social support was in turn associated with parenting behaviors. In particular, mothers who perceived higher levels of social cohesion and social control in their neighborhoods also reported greater social support. This finding is consistent with theories of social organization and collective efficacy in that neighborhoods in which residents have strong social ties and share in imposing norms on other residents help provide support to parents (Beyers et al., 2003; Sampson et al., 1999; Sampson et al., 1997). Further, parents in neighborhoods where residents have strong connections to each other are more likely to have someone to rely on in times of need. This finding is also consistent with prior research showing a relationship between residential stability and higher levels of instrumental support (Turney & Harknett, 2010).

However, perceptions of neighborhood disorganization were not related to levels of social support. This is contrary to what would be expected based on theories of social disorganization (Shaw & McKay, 1942); residents of more disorganized neighborhoods would be expected to report lower levels of social support, due to the isolation and lack of trust among neighbors in such areas (Ross et al., 2001). One possible explanation is that neighborhood collective efficacy (i.e., social cohesion and control) is more important than disorganization in relation to social support. It may be that the active engagement of neighbors in areas with high collective efficacy counteracts the negative influences of disorganization. Although disorganization can cause problems in maintaining social order (Shaw & McKay, 1942), residents in neighborhoods with high collective efficacy actively make efforts to maintain order, such as imposing shared norms for behavior, creating relationships, and supervising neighborhood youth (Sampson et al., 1999; Sampson et al., 1997). These efforts may also help develop social support for residents.

A second possible explanation is that, among this sample, the average levels of neighborhood disorganization were relatively low, despite a range of neighborhood conditions. A third explanation is that the measurement differences from other studies may explain the lack of relationship. Our study is in contrast to previous research finding that neighborhood disadvantage was related to receiving less instrumental support, especially financial assistance (Turney & Harknett, 2010). However, sample differences exist between our study and that of Turney and Harknett. Their study’s sample included mostly unmarried, mostly minority, mothers of young children. In contrast, our sample is based on mothers of pre-adolescent youth from relatively more advantaged, yet diverse ethnic backgrounds. In addition, our measure of support, while including instrumental/financial support, was mostly based on emotional support, while their measure included instrumental and financial support, yet no indicator of emotional support. Finally, a fourth explanation is that the relationship may not be linear. Levels of social support may decrease more dramatically at very high levels of disorganization, as parents restrict children’s activities and isolate themselves from neighbors (Furstenberg et al., 1993).

In addition, archival indicators of neighborhood characteristics from the census were not related to social support or parenting outcomes. This is inconsistent with expectations based on theories of social disorganization (Shaw & McKay, 1942) and previous findings (Turney & Harknett, 2010). Our perspective is that although commonly used (Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002), census data may not reflect residents’ own perceptions of their neighborhood (O’Neil et al., 2001), and residents’ own views may be more important for their outcomes (Bowen et al., 2000; Burton & Jarrett, 2000). However, findings may also be due to omitted variable bias. For example, problems with mothers’ physical or mental health (e.g., depression) may cause mothers to view their neighborhoods as low quality, regardless of their actual quality, and to use ineffective parenting strategies. Our study did not assess measures of mothers’ health, but this may be important to consider in future studies.

Higher levels of social support were related to many effective parenting strategies. Specifically, mothers who reported greater availability of social support were also more likely to use more effective parenting styles, including higher levels of authoritative parenting and lower levels of permissive parenting. These mothers were also more likely to have higher levels of parent-child communication and parental monitoring. These findings are in accordance with prior studies showing the importance of social support for positive and engaged parenting behaviors (Ceballo & McLoyd, 2002; Marra et al., 2009; Priel & Besser, 2002). One exception was that social support was not related to authoritarian parenting style. Baumrind (1966) referred to authoritarian parents as controlling their child’s behavior based on an “absolute standard.” It is possible that parents with this style may not look to others for guidance or external support, but instead feel more self-reliant as parents.

These findings offer some important new findings to the existing literature by extending effects of neighborhoods and social support to specific parenting behaviors (e.g., communication). In addition, most prior studies examining the relationship between social support and parenting have focused on parents of infants and very young children. Few studies have extended findings to show the importance of social support for parents of pre-adolescent or adolescent youths (Ghazarian & Roche, In press). The current study contributes to the literature by extending findings to parents of pre-adolescent youths from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Background demographic variables included in the model were also related to social support and parenting outcomes. Specifically, ethnicity was related to parenting style, such that White mothers were less likely to endorse using an authoritarian parenting style and more likely to use an authoritative parenting style, as consistent with past research (Baumrind, 1972; Dornbusch, Ritter, Leiderman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987). Also consistent with previous studies (Patterson & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1984; Smetana & Daddis, 2002), mothers of older youth used lower levels of monitoring behaviors, as parents generally allow more independence as youth proceed through adolescence (Chilcoat, Dishion, & Anthony, 1995; Li, Feigelman, & Stanton, 2000). In addition, mothers with higher levels of education reported less communication and monitoring of their child. These mothers’ lower levels of communication and monitoring is in contrast to prior studies showing that parents with higher socio-economic statuses provide more monitoring and are more engaged in conversations with their children (Beyers et al., 2003; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). It is possible that more educated mothers might have more time-consuming and demanding careers that allow them less time to spend actively talking to and supervising their child.

Limitations of the current study should also be noted. As the data are cross-sectional, directionality remains unclear. It is possible that social support leads to perceptions of neighborhood cohesion and control, rather than the reverse. Additionally, it is also possible that parents with greater social support and more effective parenting may select into neighborhoods with higher levels of cohesion and control. However, due to the possibility of differential mixing of families with different parenting strategies across neighborhoods, it is difficult to determine what portion of the observed relationships is due to self-selection. Future work examining these relationships over time will add to a better understanding of causal ordering. In addition, social support in the current study mainly includes items regarding emotional support, with items regarding instrumental support grouped into one question (i.e., friends to loan money, help with chores, or provide a place to stay). Future studies collecting more data on specific types of social support (e.g., emotional, financial, and in-kind support) would allow for the examination of the roles of these different types of support in the relationship between neighborhood perceptions and parenting behaviors. Generalizability of this study may also be limited in that the sample includes relatively advantaged mothers of 11–12 year olds, who agreed to participate in a prevention program. Another limitation is that the source of social support in this study is unknown. It may be that mothers in neighborhoods with low cohesion and control have friends and family with few resources, and these people may or may not live in the neighborhood. Alternatively, it may be that neighbors are unable to help. Future research should examine the importance of the source of support.

Overall, findings from the current study suggest the importance of understanding how parental perceptions of neighborhoods are related to their ability to access social support from friends and family, and provide evidence that supports the importance of social support for effective parenting behaviors. It appears that the close social connections and shared values in neighborhoods with high levels of collective efficacy benefit parents by increasing the accessibility of social support, thereby helping to encourage effective parenting behaviors. Prevention strategies should focus on helping parents to build a network of reliable supports on which they can rely for assistance and advice.

Appendix.

Survey Questions

| Domains and Items |

|---|

| Neighborhood Disorganization |

| Physical disorder: |

| Vandalism, buildings and personal belongings broken and torn up |

| Abandoned houses or buildings |

| Run down and poorly kept buildings and yards |

| Social disorder: |

| Different ethnic or cultural groups who don’t get along with each other |

| Little respect for rules, laws, and authority |

| Drunks/winos and/or junkies |

| Prostitution, ‘street walkers’ |

| Transients, street people, bums |

| Unsupervised children |

| Groups of teenagers hanging out in public places making a nuisance of themselves |

| Structural/system problems: |

| High unemployment, many people out of work |

| City officials ignoring problems |

| Police not caring about our problems |

| Poor schools |

| Police not available |

| Transportation not available |

| Crime/victimization: |

| Sexual assaults or rapes |

| Burglaries and thefts |

| Illegal gambling |

| Assaults and muggings |

| Delinquent gangs |

| Drug use or drug dealing in open |

| Selling of stolen goods |

| Unsafe being out alone at night |

| Unsafe being on the streets during the day |

| Drug houses, crack houses |

| Drive by shootings |

| Neighborhood Social Cohesion |

| People in this neighborhood can be trusted |

| This is a close-knit neighborhood |

| People around here are willing to help their neighbors |

| People in this neighborhood generally don't get along with each other* |

| People in this neighborhood do not share the same values* |

| Neighborhood Social Control |

| [What is the likelihood that your neighbors could be counted on to intervene in the following situations…] |

| Children were skipping school and hanging out on a street corner |

| Children spray-painting graffiti on a local building |

| Children showing disrespect to an adult |

| A fight breaking out in front of their house |

| Social Support |

| When I need advice about something, I have a friend who will help me |

| I have friends to do things when I want to |

| If I needed to borrow money, get help with chores, or a place to stay, my friends would help me |

| When I have worries or troubles, I have friends who will listen to my problems |

| Permissive parenting style |

| I find it difficult to discipline our child |

| I give into our child when the child causes a commotion about something. |

| I threaten our child with punishment more often than actually giving it |

| I state punishments to our child and do not actually do them |

| I spoil our child |

| I withhold scolding and/or criticism even when our child acts contrary to our wishes. |

| I allow our child to annoy someone else. |

| I appear confident about parenting abilities.* |

| _I’m afraid that disciplining our child for misbehavior will cause the child to not like his/her parents. |

| I ignore our child’s misbehavior. |

| I carry out discipline after our child misbehaves.* |

| I allow our child to interrupt others. |

| I bribe our child with rewards to bring about compliance. |

| I set strict well-established rules for our child.* |

| I appear unsure on how to solve our child’s misbehavior |

| Authoritarian parenting style |

| I use physical punishment as a way of disciplining our child |

| When our child asks why he/she has to conform, I state: because I said so, or I am your parent and I want you to. |

| I spank when our child is disobedient |

| I punish by taking privileges away from our child with little if any explanations. |

| I yell or shout when our child misbehaves |

| I explode in anger towards our child |

| I grab our child when being disobedient |

| I scold and criticize to make our child improve |

| I use threats as punishment with little or no justification |

| I punish by putting our child off somewhere alone with little if any explanations. |

| I scold or criticize when our child’s behavior doesn’t meet our expectations. |

| I slap our child when the child misbehaves |

| Authoritative parenting style |

| I am responsive to our child’s feelings and needs |

| I take our child’s desires into account before asking the child to do something |

| I explain to our child how we feel about the child’s good and bad behavior |

| I encourage our child to talk about his/her troubles |

| I encourage our child to freely express himself/herself even when disagreeing with parents |

| I emphasize the reasons for rules |

| I give comfort and understanding when our child is upset |

| I give praise when our child is good |

| I take into account our child’s preferences in making plans for the family. |

| I show respect for our child’s opinions by encouraging our child to express them. |

| I allow our child to give input into family rules |

| I give our child reasons why rules should be obeyed |

| I have warm and intimate times together with our child |

| I help our child to understand the impact of behavior by encouraging our child to talk about the consequences of his/her own actions |

| I explain the consequences of the child’s behavior |

| Parent-child communication |

| Plans for the day |

| Plans for the future |

| Relationship with friends |

| What she/he is doing in school |

| Drinking alcohol |

| Using drugs |

| Smoking cigarettes |

| Fighting |

| Carrying a weapon |

| His or her concerns |

| Parental monitoring |

| In the course of a day, how often do you know where this child is |

| How often do know who this child is with when he or she is away from home |

| How often do you know when this child does something really well at school or someplace else away from home |

| How often do you know when this child gets into trouble at school or someplace else away from home |

| How often do you know when this child does not do things you have asked him or her to do |

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant # R01-AA015323-01, 2005–2010, “Adolescent Family-Based Alcohol Prevention,” B. A. Miller, PI. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Hilary F. Byrnes, Prevention Research Center, 1995 University Ave., Suite 450, Berkeley, CA 94704; Work: (513) 321-0891; Cell: (510) 708-2215; hbyrnes@prev.org; fax: (510) 644-0594.

Brenda A. Miller, Prevention Research Center, 1995 University Ave., Suite 450, Berkeley, CA 94704; Work: (510) 883-5768; bmiller@prev.org, fax: (510) 644-0594

References

- Bamaca MY, Umana-Taylor AJ, Shin N, Alfaro EC. Latino adolescents’ perception of parenting behaviors and self-esteem: Examining the role of neighborhood risk. Family Relations. 2005;54:621–632. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Effects of parental monitoring and peer deviance on substance use and delinquency. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:1084–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Foshee VA, Ennett ST, Hicks K, Pemberton M. Family Matters: A family-directed program designed to prevent adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Health Promotion Practice. 2001;2(1):81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development. 1966;37(4):887–907. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. An exploratory study of socialization effects on black children: Some black-white comparisons. Child Development. 1972;43(1):261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS for Windows, 6.1. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 1985–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA. Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths' externalizing behaviors: a multilevel analysis. American Journal Of Community Psychology. 2003;31(1–2):35–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1023018502759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn C-S, Suwalsky JTD, Haynes OM. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development: The Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Social Status and The Socioeconomic Index of Occupations. In: Bornstein MH, Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development, Monographs in parenting series. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GL, Bowen NK, Cook P. Neighborhood characteristics and supportive parenting among single mothers. In: Fox GL, Benson ML, editors. Contemporary perspectives in family research: Vol. 2. Families, crime, and criminal justice. New York: Elsevier Science; 2000. pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. In: Vasta R, editor. Six Theories of Child Development. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1992. pp. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Jarrett RL. In the mix, yet on the margins: The place of families in urban neighborhood and child development research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62(4):1114–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes HF, Chen M-J, Miller BA, Maguin E. The relative importance of mothers’ and youths’ neighborhood perceptions for youth alcohol use and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:649–659. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes HF, Miller BA, Chen MJ, Grube JW. The roles of mothers’ neighborhood perceptions and specific monitoring strategies in youths’ problem behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(3):347–360. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, McLoyd VC. Social support and parenting in poor, dangerous neighborhoods. Child Development. 2002;73(4):1310–1321. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Dishion TJ, Anthony JC. Parent monitoring and the incidence of drug sampling in urban elementary school children. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;141(1):25–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YC, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Foshee VA. Neighborhood Influences on adolescent cigarette and alcohol use: mediating effects through parent and peer behaviors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005 Jun;46:187–204. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl T, Ceballo R, Huerta M. In the eye of the beholder: Mothers' perceptions of poor neighborhoods as places to raise children. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38(4):419–434. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: a conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review. 1998;1(1):61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman H, Roberts DF, Fraleigh MJ. The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development. 1987;58(5):1244–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen DJ. Cohabitation and exchanges of support. Social Forces. 2005;83(3):1097–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen DJ, Hogan DP. Giving between generations in American families. Human Nature. 1990;1(3):211–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02733984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D, Ageton S, Huizinga D, Knowles B, Canter R. The prevalence and incidence of delinquent behavior: 1976–1980. Boulder: Behavioral Research Institute; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Frank R, Cerda M, Rendon M. Barrios and burbs: residential context and health-risk behaviors among Angeleno adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48(3):283–300. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Jr, Belzer A, Davis C, Levine JA, Morrow K, Washington M. How families manage risk and opportunity in dangerous neighborhoods. In: Wilson WJ, editor. Society and the Public Agenda. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Jr, Cook T, Eccles J, Elder GH, Sameroff A. Managing to make it: Urban families in high-risk neighborhoods. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Jr, Hughes ME. The influence of neighborhoods on children's development: A theoretical perspective and a research agenda. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan G, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty: Policy Implications in Studying Neighborhoods. Vol. 2. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazarian SR, Roche KM. Social support and low-income, urban mothers: Longitudinal associations with adolescent delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9544-3. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding DJ. Counterfactual Models of Neighborhood Effects: The Effect of Neighborhood Poverty on Dropping Out and Teenage Pregnancy. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;109(3):676–719. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway SR, Mulherin S. The effect of adolescent neighborhood poverty on adult employment. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2004;26(4):427–454. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, I. S. U. The Capable Families and Youth Study; 2000a. Mother/Female Caregiver Questionnaire 1. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, I. S. U. The Capable Families and Youth Study; 2000b. Mother/Female Caregiver Questionnaire 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Van Den Bos J, Vanderryn J, Costa FM, Turbin MS. Protective factors in adolescent problem behavior: Moderator effects and developmental change. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31(6):923–933. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KJ, Comello ML, Hunn LC. Parent-child communication, perceived sanctions against drug use, and youth drug involvement. Adolescence. 2002;37(148):775–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohen DE, Leventhal T, Dahinten VS, McIntosh CN. Neighborhood disadvantage: pathways of effects for young children. Child Development. 2008;79(1):156–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, Heller L. Predictors of parenting among African American single mothers: Personal and contextual factors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:448–460. [Google Scholar]

- Kubrin CE, Weitzer R. New directions in social disorganization theory. JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN CRIME AND DELINQUENCY. 2003;40(4):374–402. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Brown TL, Phillips CM, Ialongo NS. The relationship between perceptions of neighborhood characteristics and substance use among urban African American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;34(3–4):205–218. doi: 10.1007/s10464-004-7415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Feigelman S, Stanton B. Perceived parental monitoring and health risk behaviors among urban low-income African-American children and adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Psychological distress among black and white Americans: differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(3):390–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra JV, McCarthy E, Lin HJ, Ford J, Rodis E, Frisman LK. Effects of social support and conflict on parenting among homeless mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(3):348–356. doi: 10.1037/a0017241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Aalborg AE, Byrnes HF, Bauman KE, Spoth R. Choice of family-based adolescent alcohol and drug prevention programs: Relationship to parent and child characteristics. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr109. (In review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman K, Harrison L, Dashiff C, Davies S. Relationships between parenting styles and risk behaviors in adolescent health: an integrative literature review. Revista Latino-Americana De Enfermagem. 2008;16(1):142. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692008000100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Regan KM, Quigley JM. Working Papers. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Program on Housing and Urban Policy, Institute of Business and Economic Research, UC Berkeley; 1996. Spatial Effects upon Unemployment Outcomes: The Case of New Jersey Teenagers. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil R, Parke RD, McDowell DJ. Objective and subjective features of children’s neighborhoods: Relations to parental regulatory strategies and children’s social competence. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2001;32:132–155. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JS, Benson MJ. Parent-adolescent relations and adolescent functioning: Self-esteem, substance abuse, and delinquency. Adolescence. 2004;39(155):519–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Ringwalt CL, Flewelling RL. Effects of parenting, father absence, and affiliation with delinquent peers on delinquent behavior among African-American male adolescents. Adolescence. 2003;38(149):15–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development. 1984;55(4):1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG. Handbook of Social Support and the Family. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Nix R, Foster EM, Jones D. Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63(4):941–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Unger JB, Wagner KD, Ritt-Olson A, Sussman S. Effects of parental monitoring, parent-child communication, and parents' expectation of the child's acculturation on the substance use behaviors of urban, Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2008;7(2):200–213. doi: 10.1080/15332640802055665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priel B, Besser A. Perceptions of early relationships during the transition to motherhood: The mediating role of social support. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23(4):343–360. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin BH, Quane JM. Social contexts and urban adolescent outcomes: The interrelated effects of neighborhoods, families, and peers on African-American youth. Social Problems. 2002;49(1):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) In: Perlmutter BF, Touliatos J, Holden GW, editors. Handbook of family measurement techniques: Vol. 3. Instruments & index. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2001. pp. 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disorder, subjective alienation, and distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50(1):49–64. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Pribesh S. Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and mistrust. American Sociological Review. 2001;66(4):568–591. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Earls F. Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review. 1999;64(5):633–660. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing "neighborhood effects": Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur RL, Laumann EO. A paradigm for social capital. Rationality and Society. 1998;10(4):481–501. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw CR, McKay HD. Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Johnson C, Beaman J, Conger RD, Whitbeck LB. Parents and peer group as mediators of the effect of community structure on adolescent problem behavior. American Journal Of Community Psychology. 1996;24(1):145–171. doi: 10.1007/BF02511885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Johnson C, Conger RD, Lorenz FO. Linking community context to quality of parenting: A study of rural families. Rural Sociology. 1997;62(2):207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Daddis C. Domain-specific antecedents of parental psychological control and monitoring: the role of parenting beliefs and practices. Child Development. 2002;73(2):563–580. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SJ, Crowder K. Neighborhood poverty and nonmarital fertility: Spatial and temporal dimensions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(1):89–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Lepper H. Alcohol initiation outcomes of universal family-focused preventive interventions: one- and two-year follow-ups of a controlled study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol/Supplement. 1999;13:103–111. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern SB, Smith CA. Family processes and delinquency in an ecological context. Social Service Review. 1995 Dec;1995:703–731. [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Wei E, Farrington DP, Wikstrom PO. Risk and promotive effects in the explanation of persistent serious delinquency in boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):111–123. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. The contextual effects of community social capital on academic performance. Social Science Research. 1999;28:403–426. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54(4):416–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turney K, Harknett K. Neighborhood disadvantage, residential stability, and perceptions of instrumental support among new mothers. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31(4):499–524. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09347992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger DG, Wandersman LP. The relation of family and partner support to the adjustment of adolescent mothers. Child Development. 1988;59(4):1056–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass and Public Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]