Abstract

Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are a major constituent of the tumor stroma, but little is known about how cancer cells transform normal fibroblasts into CAFs. miRNAs are small noncoding RNA molecules that negatively regulate gene expression at a posttranscriptional level. While it is clearly established that miRNAs are deregulated in human cancers, it is not known whether miRNA expression in resident fibroblasts is affected by their interaction with cancer cells. We found that in ovarian CAFs, miR-31 and miR-214 are downregulated while miR-155 is upregulated when compared to normal or tumor-adjacent fibroblasts. Mimicking this deregulation by transfecting miRNAs and miRNA inhibitors induced a functional conversion of normal fibroblasts into CAFs, and the reverse experiment resulted in the reversion of CAFs into normal fibroblasts. The miRNA-reprogrammed normal fibroblasts and patient-derived CAFs shared a large number of upregulated genes highly enriched in chemokines, which are known to be important for CAF function. The most highly upregulated chemokine, CCL5, was found to be a direct target of miR-214. These results indicate that ovarian cancer cells reprogram fibroblasts to become CAFs through the action of miRNAs. Targeting these miRNAs in stromal cells could have therapeutic benefit.

INTRODUCTION

During invasion and metastasis cancer cells change the normal stroma into a “reactive” environment, which promotes the growth and viability of tumor cells (1). Upon interaction with cancer cells, quiescent resident fibroblasts, which are the predominant cell type in normal stroma, are transformed into cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) which become a major component of the tumor stroma. CAFs promote cancer cell invasion, proliferation, and metastasis by secreting cytokines and chemokines, which stimulate receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and EMT programs (1). Moreover, CAFs secrete a distinctive extracellular matrix that promotes the attachment and invasion of tumor cells (2). Several steps of the bi-directional signaling between cancer cells and fibroblasts have been elucidated. Neoplastic cells secrete cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β to activate fibroblasts and stimulate their proliferation (3). The CAFs, in return, secrete cancer activating chemokines such as SDF-1α, thereby stabilizing and promoting tumorigenesis (4). However, it is currently not clear how cancer cells reprogram quiescent fibroblasts to become CAFs.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNA molecules that negatively regulate gene expression at a posttranscriptional level (5). miRNAs are powerful regulators of cellular differentiation, since they affect the expression of many genes and are deregulated in cancer cells (6). Presently, it is not clear whether endogenous miRNAs are involved in the conversion of resident fibroblasts to CAFs. Several reports have demonstrated that miRNAs can reprogram various somatic cells to become pluripotent stem cells (7). A combination of miR-124 and the transcription factors MYT1L and BRN2 reprograms primary human dermal fibroblasts into functional neurons that exhibit typical neural morphology, fire action potentials, and produce functional synapses (8). miR-15 and -16, are downregulated in fibroblasts surrounding prostate tumors (9) but their functional role in promoting tumor growth is unclear. Recently, miR-511-3p has been reported to prevent the tumor-promoting activity of tumor associated macrophages (10).

Epithelial serous ovarian carcinoma (OvCa) has a unique pattern of metastasis which remains largely restricted to the abdominal cavity, in which the omentum, a large fat pad in front of the bowel, is a major site of colonization (11). Ovarian tumors and metastases have a substantial stromal component of which CAFs are an important constituent (3). Though the role of CAFs in ovarian cancer progression is well established, the mechanism of CAF formation remains unclear (12).

While most miRNA studies have focused on the tumor cell, little is known about miRNA expression in the tumor microenvironment. Given the broad regulatory role of miRNAs, we have now investigated whether miRNAs are involved in the reprograming of normal fibroblasts to CAFs, thereby promoting tumorigenesis. We report here that a combination of three miRNAs induce normal human omental fibroblasts to become CAFs, leading to the upregulation of chemokines important in invasion and metastasis.

RESULTS

Identification of miRNAs Deregulated in Cancer Associated Fibroblasts

The miRNA expression in CAFs was compared with that in primary human normal omental fibroblasts (NOFs) using two independent, unbiased approaches. In one approach, primary human CAFs were isolated from the omental metastases of patients with metastatic serous OvCa and compared to tumor adjacent NOFs extracted from a normal area of the omentum, at least 1 inch from the tumor, from the same patients. In the other approach, NOFs from the omentum of cancer-free patients operated on for benign gynecologic disease (e.g. fibroids) were compared to NOFs co-cultured with HeyA8 OvCa cells (Fig. 1A). While the former approach identifies the miRNA changes that occur during tumor progression, the latter detects the early changes induced exclusively by cancer cells. Confocal time-lapse microscopy revealed that CAFs were more migratory (Supplementary Fig. S1A,B) and induced the invasion of different OvCa cell lines more efficiently, than either NOFs or tumor adjacent NOFs (Supplementary Fig. S2A). The induced CAFs, generated by a 7-day co-culture of NOFs with OvCa cells, had an enhanced ability to promote tumor cell invasiveness (Supplementary Fig. S2B), suggesting that cancer cells impart CAF-like properties to these cells.

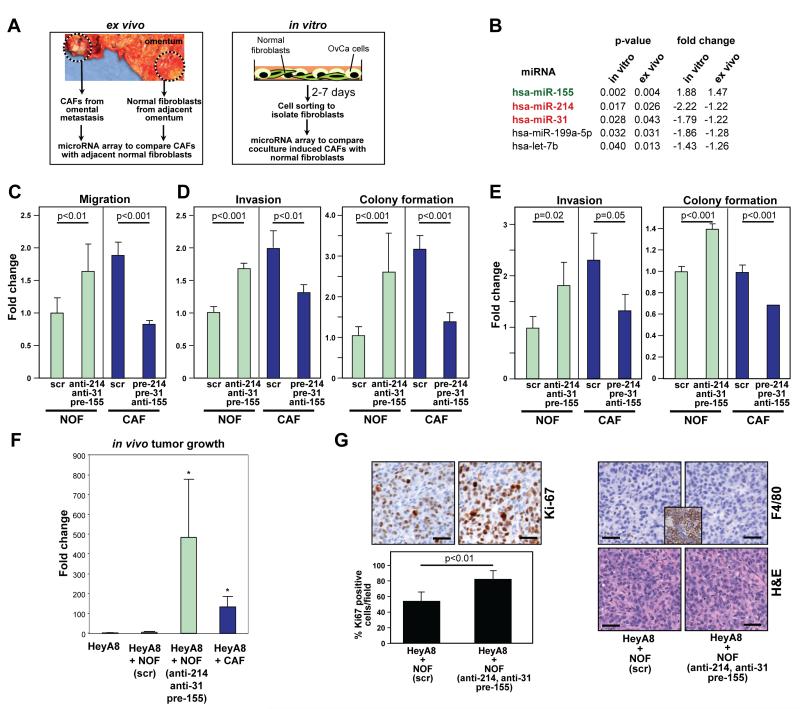

Figure 1.

Identification of miRNAs that are both markers and regulators of cancer associated fibroblasts.

A, Left: Isolation of cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and tumor adjacent normal fibroblasts (NOFs) from partially tumor-transformed omentum of patients with serous ovarian cancer (OvCa). Right: Generation of induced CAFs by co-culturing fluorescently labeled NOFs from the omentum of non-cancer patients with OvCa cell lines.

B, List of miRNAs upregulated or downregulated. miRNAs were sorted according to the p-value of correlation.

C, Migration of NOFs triple transfected with anti-miR-31, anti-miR-214, and pre-miR-155 (to generate miR-CAFs) and CAFs triple transfected with pre-miR-214, pre-miR-31 and anti-miR-155 (to generate NOFs) compared to matching scrambled controls.

D-E, Tumor cell invasion and colony formation of HeyA8 (D) and SKOV3ip1 (E) cells in the presence of triple transfected NOFs/CAFs. Data are shown as fold change normalized to NOFs transfected with matching scrambled controls. Error bars represent s.d. of three independent experiments. One-tailed t-tests were performed.

F, Subcutaneous tumor growth in mice (10 mice/group) injected with either HeyA8 cells expressing luciferase alone, or HeyA8 cells co-injected with immortalized NOFs transiently expressing either scrambled control (scr) or anti-miR-31, anti-miR-214, and pre-miR-155, or with immortalized CAFs. Luciferase activity was quantified after 14 days and normalized to HeyA8 cells alone and the fold change in radiance plotted. One-way ANOVA was performed comparing all groups to HeyA8+scrambled control NOFs (scr). * p<0.05.

G, Immunohistochemistry (Ki-67 staining for proliferation, F4/80 staining for macrophages, H&E) of tumors isolated from mice injected with either HeyA8 cells + NOFs transiently expressing scrambled control (scr) or miR-31, miR-214, and anti-miR-155 to induce CAFs (miR-CAFs). Ki-67 staining was quantified. Inset: mouse spleen as positive control for F4/80 staining. Scale bar=50 μm.

Therefore, the miRNA expression of CAFs was compared to that of adjacent NOFs and the miRNA expression of NOFs was compared to that of induced CAFs (Fig. 1A). A miRNA array analysis of RNA isolated from these cells identified 19 significantly expressed miRNAs that were upregulated (p<0.05) and 15 miRNAs that were downregulated in the co-cultured, induced CAFs (Table S1). Of these miRNAs, one was found to be upregulated and four downregulated in CAFs compared to matching adjacent NOFs from six patients with postmenopausal, advanced, serous ovarian carcinoma (Fig. 1B and Table S1). In both induced CAFs and primary patient-derived CAFs, the miRNAs that were most significantly up- and downregulated were miR-155 and miR-214, respectively, and were selected for further testing. miR-31 was included because it was the second most significantly downregulated miRNA in induced CAFs and because it was reported as downregulated in fibroblast cell lines derived from patients with endometrial cancer (13). Using quantitative real-time PCR, downregulation of miR-31 and miR-214 and upregulation of miR-155 was confirmed in all CAF and induced CAF samples (Supplementary Fig. S3A). In situ hybridization of an omental metastasis from a patient with OvCa confirmed that the expression of miR-214 was lost in CAFs and high in adjacent NOFs; an opposite expression pattern was observed for miR-155 (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

Reversible Conversion of Normal Fibroblasts into CAFs

Triple transfection of NOFs with anti-miR-31, anti-miR-214, and pre-miR-155 (miR-CAFs) enhanced fibroblast migration as well as the invasion and colony formation of co-cultured HeyA8 and SKOV3ip1 cells (Fig. 1C-E), suggesting that deregulating the expression of the three miRNAs could convert NOFs to CAFs. The reverse was also true, since transfection of CAFs with pre-miR-31, pre-miR-214, and anti-miR-155 reduced their migration, and also reduced the invasion and colony formation of co-cultured OvCa cells to levels similar to those of OvCa cells co-cultured with NOFs (Fig. 1C-E). miRNA transfection was validated by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S4A,B). To assess the contribution of each of the miRNAs to the functional effects of miR-CAFs on cancer cells (migration, invasion, colony formation) NOFs or CAFs were transfected with individual miRNAs or their inhibitors. miR-214 was active in regulating fibroblast migration and cancer cell invasiveness, miR-155 predominantly affected cancer cell invasiveness, and miR-31 affected colony formation of the cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. S5A-F).

To test the in vivo activity of the identified miRNAs, miR-CAFs or NOFs transfected with scrambled RNA were co-injected with luciferase expressing HeyA8 cells subcutaneously into mice. Co-injected CAFs were used as a positive control. Both miR-CAFs and CAFs significantly enhanced the growth of tumor cells when compared to NOFs (Fig. 1F) which was also reflected in increased expression of the proliferation marker Ki-67 (Fig. 1G). This growth enhancement was a direct effect of fibroblasts on tumor cells because the number of infiltrating macrophages or neutrophilic granulocytes was similar in all experimental groups (Fig. 1G and data not shown).

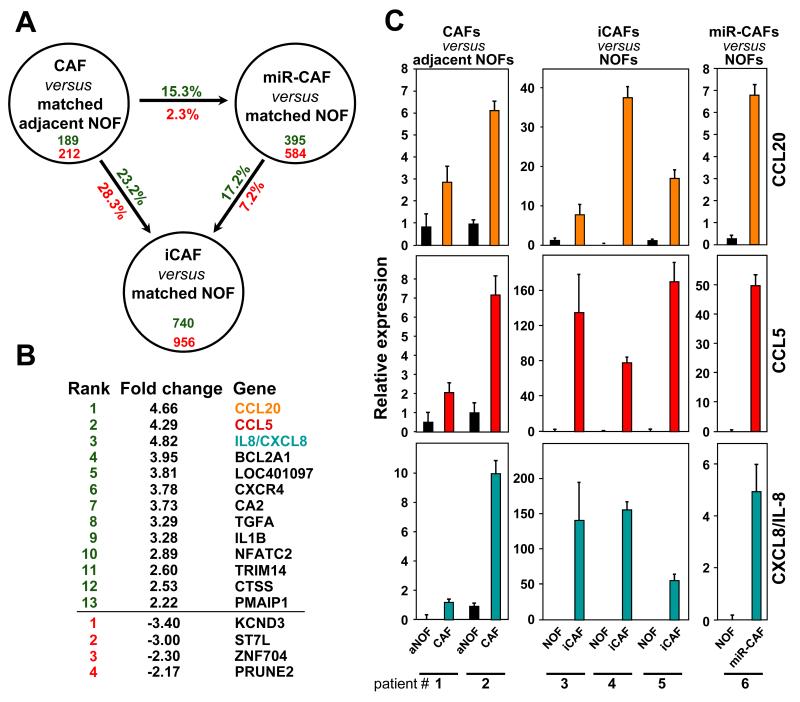

Chemokines are the Most Highly Deregulated Genes in CAFs, Induced CAFs and miR-CAFs

To determine whether altering the expression of the three miRNAs in NOFs to generate iCAFs mimicked the differentiation of NOFs into CAFs in patients, tumor-adjacent NOFs and CAFs were subjected to gene array analysis. These data were compared to the gene expression profile obtained from miR-CAFs, which were re-programmed NOFs derived from patients without cancer through transfection with anti-miR-214/31 and pre-miR-155. The successful transfection of the miRNAs/miRNA inhibitors and their functional effects on fibroblasts was confirmed using PCR and invasion assays (data not shown). Table S2 lists the genes that were upregulated >1.5 fold in the two CAF preparations (when compared to adjacent NOFs from the same patients) and in miR-CAFs (when compared to matching NOFs). Surprisingly, seven of the ten most highly upregulated genes were chemokines. Most of these chemokines were also found to be upregulated when CAFs were compared to NOFs and miR-CAFs to adjacent NOFs (Table S3 and data not shown).

In order to determine the extent of the reprogramming by miRNAs we compared gene expression changes between patient-derived CAFs, induced CAFs, and miR-CAFs and their respective normal fibroblasts (Fig. 2A). The overlap in induced gene changes between miR-CAFs and CAFs was 15.3% compared to 23.2% between induced CAFs and CAFs. Interestingly, only 13 genes were upregulated and 4 genes downregulated in the CAFs, induced CAFs and miR-CAFs from all patients, and, again, the top three upregulated genes were chemokines (Fig. 2B). The upregulation of these chemokines on the mRNA level was confirmed by qRT-PCR for each array analysis (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Chemokines are the most highly upregulated genes in CAFs, induced CAFs (iCAFs) and miR-CAFs.

A, Comparison of genes upregulated (green) and downregulated (red) in patient-derived CAFs (compared to matched aNOFs), induced CAFs derived from a 7 day co-culture of NOFs with HeyA8 cells (compared to matched NOFs) and miR-CAFs 2 days after triple transfection (compared to matched NOFs).

B, Ranked list of genes found to be up- (green) and down-regulated (red) in CAFs, induced CAFs and miR-CAFs from all OvCa patients.

C, qRT-PCR to assess upregulation of the three highest upregulated chemokines for each array analysis. Error bars represent s.d. of a triplicate experiment.

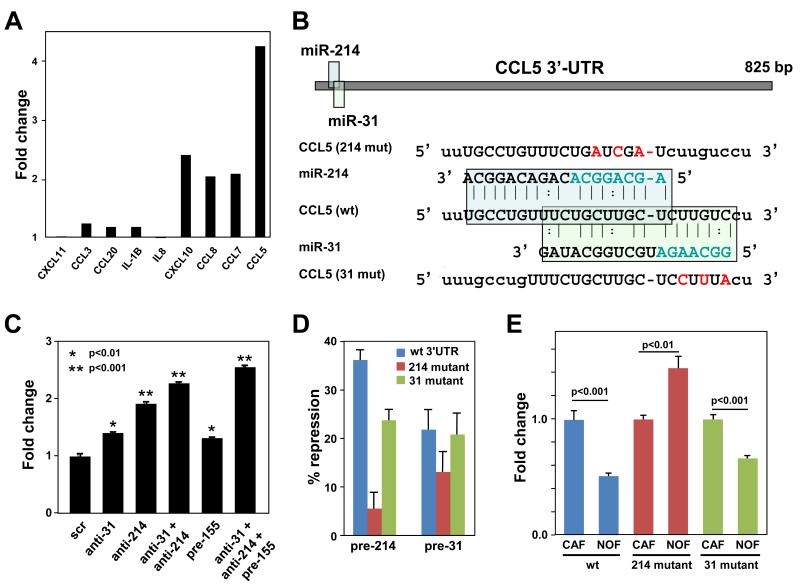

Identification of CCL5 as a Target of miR-214

To determine whether miR-CAFs, generated by altering miRNA expression, secreted chemokines, a protein array was constructed for ten of the most highly upregulated cytokines found on the gene array. In this assay the most highly induced chemokine on the protein level was CCL5/RANTES followed by CXCL10, CCL7, and CCL8 (Fig. 3A). To understand how miRNAs regulate expression of chemokines in CAFs, we analyzed the 3′-UTR of all 9 chemokines upregulated in miR-CAFs and CAFs for possible miRNA seed matches using miRanda, TargetScan, and PicTar software. Only one chemokine was predicted to contain seed matches for any of the 3 miRNAs. Overlapping seed matches for miR-214 and miR-31 were found in the CCL5 3′-UTR (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Identification of CCL5 as a miR-214 target secreted by cancer associated fibroblasts.

A, The culture medium of NOFs triple transfected with anti-miR-214, anti-miR-31, and pre-miR-155 (to generate miR-CAFs) was analyzed three days after transfection using a custom chemokine array designed to detect ten cytokines. Shown is one of two independent analyses which gave similar results.

B, Schematic of the miR-214 and miR-31 seed matches in the human CCL5 3′-UTR and mutated binding sites introduced into luciferase 3′-UTR constructs.

C, Detection of the cytokine CCL5 by ELISA in culture supernatant of NOFs transfected with the indicated anti-miRs or pre-miRs, thereby creating miR-CAFs.

D, 293T cells were co-transfected with the CCL5 3′-UTR (wild type (wt), miR-214 mutant, miR-31 mutant) and either pre-miR-31 or pre-miR-214. Changes in repression of luciferase activity are shown.

E, Changes in luciferase activity in NOFs or CAFs transfected with the different CCL5 3′-UTR constructs. Error bars represent s.d. of triplicate experiments. One tailed t-tests were performed.

While triple transfected NOFs secreted the most CCL5, anti-miR-214 was most efficient in inducing expression of CCL5 when transfected alone (Fig. 3C), suggesting that CCL5 is a direct target of miR-214. Luciferase constructs were used with the CCL5 wild-type 3′-UTR and two different CCL5 3′-UTR mutants with substitutions in the miR-214 or the miR-31 seed matches (Fig. 3B). Co-transfection of miR-214 or miR-31 into 293T cells, together with the luciferase constructs, showed that miR-214 was more potent in targeting the CCL5 3′-UTR than miR-31 (Fig. 3D), and this activity was greatly diminished when the miR-214 seed match was mutated. This was confirmed for endogenous miRNAs by transfecting the reporter constructs into either primary CAFs or NOFs. Luciferase activity was significantly reduced in miR-214/miR-31 high expressing NOFs when compared to CAFs, with the miR-214 site mutant showing the greatest loss of repression (Fig. 3E). Consistent with miR-214 targeting CCL5, an alignment of the 3′-UTRs of human, mouse, and rat CCL5 revealed that the region of highest identity contains the seed match for miR-214, while the sequence for miR-31 is less well conserved (Supplementary Fig. S6).

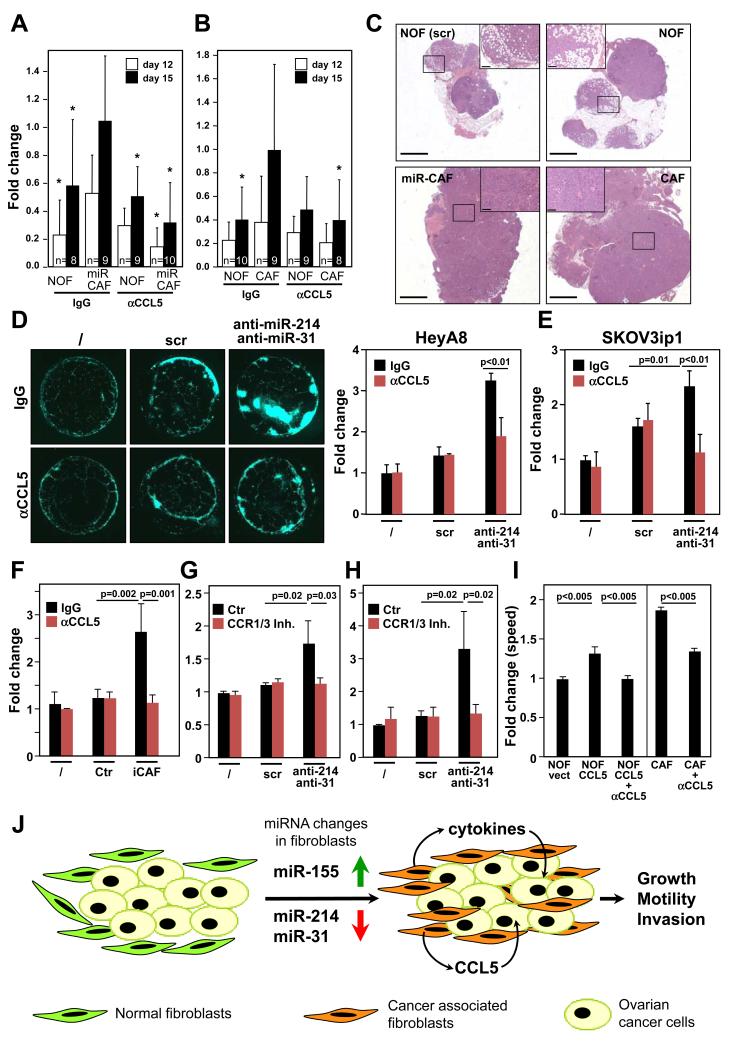

CCL5 is Critical for the Activity of both CAFs and miRNA Reprogrammed CAFs

To determine the in vivo relevance of CCL5 in the activity of miR-CAFs, miR-CAFs were generated by transiently transfecting NOFs with anti-miR-31, anti-miR-214 and pre-miR-155. Using an orthotopic OvCa mouse model, luciferase expressing HeyA8 cells were co-injected with the miR-CAFs into the ovaries of nude mice and tumor growth was monitored by bioluminescence (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S7A). Reprogrammed fibroblasts clearly increased the growth of co-injected HeyA8 cells, an effect that could be blocked by injections with a neutralizing anti-CCL5 antibody. This indicates that the CCL5 secreted by miR-CAFs is a key tumor promoting factor. To determine the in vivo significance of CCL5 in the activity of patient isolated CAFs, luciferase expressing HeyA8 cells were co-injected orthotopically with either NOFs or CAFs (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. S7B). The neutralizing anti-CCL5 antibody again inhibited the augmented growth of HeyA8 promoted by co-injected CAFs. The histology of the ovaries from mice co-injected with either NOFs, miR-CAFs or CAFs (Fig. 4C) showed that all tumors were invasive, high-grade and were primarily composed of cancer cells. Tumor cells co-injected with either miR-CAFs or CAFs showed increased invasive growth replacing normal ovarian structures such as follicles and fallopian tube more efficiently compared to co-injected NOFs. The cancer cells in both the miR-CAF IgG and CAF IgG group had more Ki-67 staining (Supplementary Fig. S7C-D) indicating increased proliferation which could be inhibited by the anti-CCL5 antibody. Consistent with the histologic analysis of the subcutaneously injected tumors (Fig. 1G) there was no difference in infiltrating immune cells (data not shown).

Figure 4.

CCL5 is critical for the activity of CAFs and miR-CAFs.

A, HeyA8 cells expressing luciferase were co-injected orthotopically into the mouse ovary with either NOFs triple-transfected with anti-miR-31, anti-miR-214, and pre-miR-155 (miR-CAF) or with equivalent scrambled controls (NOF). Mice were injected with either control IgG or a neutralizing anti-CCL5 antibody (αCCL5). Tumor growth was monitored by bioluminescence using Xenogen IVIS Spectrum and the fold change in radiance plotted. One-way ANOVA was performed comparing all groups to HeyA8+miR-CAFs treated with IgG for the same time point (* p<0.05).

B, HeyA8 cells expressing luciferase were co-injected orthotopically with either NOFs or CAFs. Mice were injected twice with either control IgG or a neutralizing anti-CCL5 antibody (αCCL5). Tumor growth was monitored by bioluminescence using Xenogen IVIS Spectrum and the fold change in radiance plotted. Number of mice per group is indicated at the base of the columns. One-way ANOVA was performed comparing all groups to HeyA8+CAFs treated with IgG for the same time point (* p<0.05).

C, H&E staining of ovaries from IgG injected mice shown in A (left two panels), and B (right two panels). Scale bar = 1500 μm. Insets show close up of tumor tissues (labeled by box), scale bar in insets = 200 μm.

D, Plug-homing assay. Matrigel plugs were embedded with NOFs transfected with anti-miR-31 and anti-miR-214, scrambled control (scr) or no cells (/) and placed equidistant in the same culture dish and overlaid with GFP expressing HeyA8 cells. Half of the wells were treated with an IgG control antibody and half were treated with a neutralizing anti-CCL5 antibody (αCCL5). Homing of OvCa cells to the matrigel plugs was imaged (left) and quantified (right).

E, Quantification of the homing assay shown in D, performed with GFP expressing SKOV3ip1 cells.

F, Matrigel plugs were embedded with iCAFs (NOFs co-cultured with HeyA8), corresponding parental NOFs (Ctr) or no cells (/) and placed equidistant in the same culture dish and overlaid with GFP expressing HeyA8 cells. Half of the wells were treated with an IgG control antibody and half were treated with a neutralizing anti-CCL5 antibody (αCCL5). Homing of OvCa cells to the matrigel plugs was imaged and quantified.

G, Matrigel plugs were embedded with NOFs transfected with anti-miR-31 and anti-miR-214, scrambled control (scr) or no cells (/) and placed equidistant in the same culture dish and overlaid with GFP expressing HeyA8 cells. Wells were treated with the CCR1/3 inhibitor J113863 (CCR1/3 Inh) or DMSO control (Ctr). Homing of cancer cells to the matrigel plugs was imaged and quantified. For E-G standard errors are shown for three independent experiments using fibroblasts from three to four different patients. One tailed t-tests were performed.

H, Homing assay shown in G, performed with GFP expressing SKOV3ip1 cells. Standard errors are shown for three independent experiments. One tailed t-tests were performed.

I, Co-invasion of HeyA8 with NOFs transfected with human CCL5 and treated with a CCL5 blocking antibody (NOF-CCL5+αCCL5) or IgG control (NOF-CCL5) were compared to co-invasion of HeyA8 with NOFs transfected with vector control (NOF-vect). Co-invasion of HeyA8 with CAFs treated with a CCL5 blocking antibody (CAF + αCCL5) or IgG control (CAF). All standard errors represent al least three independent experiments. One tailed t-tests were performed.

J, Schematic of miRNA induced reprograming of NOFs to CAFs in ovarian cancer. Cancer cells induce a change in expression of miR-214, miR-31 and miR-155 in NOFs resulting in reprogramming them into CAFs which then promotes tumor growth and invasion through increased secretion of cytokines (e.g.) CCL5.

Our data suggest that CCL5 is an important factor in the provision of a tumor promoting environment for OvCa cells. However, the in vivo experiments did not exclude the possibility that CCL5 acted by enhancing the conversion of NOFs to CAFs rather than by affecting the cancer cells. To test this, a novel homing assay was developed where matrigel plugs containing the different fibroblasts were placed equidistantly in the same culture dish and overlaid with media containing fluorescently labeled OvCa cells. Two OvCa cell lines were attracted by NOFs co-transfected with both anti-miR-31 and anti-miR-214 (Fig. 4D and E) as well as to induced CAFs (Fig. 4F), an effect that was inhibited by the neutralizing CCL5 antibody. These data suggested that CCL5 acts by binding to one of its cognate receptors (CCR1, 3 and 5) on the surface of the cancer cells. Analysis of a data set comparing OvCa samples and normal ovarian surface epithelial cells (14) revealed that CCR1 is upregulated in primary OvCa (data not shown). Consistently, we found CCR1 to be expressed in both HeyA8 and SKOV3ip1 cells (Supplementary Fig. S8A) and treatment of the OvCa cells with the CCR1/3 inhibitor J113863 blocked the homing of either HeyA8 or SKOV3ip1 cells to NOFs transfected with anti-miR-214 and anti-miR-31 (Fig. 4G and H). Finally, ectopic expression of CCL5 in NOFs (Supplementary Fig. S8B) significantly increased their ability to promote HeyA8 cell co-invasion an effect blocked by a CCL5 neutralizing antibody (Fig. 4I).

DISCUSSION

While the cancer-promoting role of CAFs is unambiguously established, it is less clear how quiescent fibroblasts are transformed into CAFs (1). We tackled this question with two complementary approaches; comparing primary human fibroblasts from patients with and without OvCa and a 3D organotypic co-culture model. The results indicate that the downregulation of miR-214 and miR-31 and the upregulation of miR-155 can rapidly reprogram normal fibroblasts into CAFs. These three miRNAs combined are able to activate tumor promoting functions including migration, invasion and colony formation in normal fibroblasts. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report which shows that three miRNAs cooperate in reprograming quiescent fibroblasts into cancer growth promoting active fibroblasts, suggesting that resting fibroblasts possess the plasticity to become CAFs.

Our data suggest that CCL5 is a miRNA regulated candidate effector molecule in CAFs, contributing to tumor cell recruitment and growth. CCL5 is abundant in the serum of OvCa patients with advanced, metastatic disease (15). It is also secreted by mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), which have similar functional properties to fibroblasts (16). Of note, the overexpression of CCL5 in fibroblasts was sufficient to promote the metastasis of admixed breast cancer cells (17) in a manner similar to our results, which demonstrated that contact with CCL5 transfected NOFs increased the invasion of OvCa cells.

CAFs at least partially maintain their characteristics when cultured in the absence of malignant cells, suggesting that genetic or epigenetic alterations have occurred. While genetic alterations have been reported in CAFs from breast and ovarian cancer (18, 19), careful analysis demonstrated that such genetic alterations are extremely rare (20). It is more likely that the stable phenotype of CAFs is regulated by epigenetic changes, as suggested by a genome wide analysis of breast cancer stroma (21). Our results also lend support to a model in which tumor cells directly reprogram normal residential fibroblasts to become CAFs in the absence of permanently acquired mutations by changing miRNA expression in the fibroblasts (Fig. 4J). The tumor promoting role of CAFs together with their genetic stability makes them an attractive therapeutic target in treatments aimed at removing tumor-supporting factors from the microenvironment. The model for miRNA induced NOF → CAF transformation presented here opens the possibility of a treatment approach targeting the tumor stroma with miRNA and miRNA inhibitors.

METHODS

Additional methods are included in the supplementary methods.

Fibroblast Isolation and Characterization

CAFs were isolated from tumor transformed omentum and adjacent NOFs from the normal part of the omentum. All patients had newly diagnosed advanced, metastatic high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma and were undergoing primary debulking surgery by a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Chicago. NOFs were from omentum of female patients undergoing surgery for benign reasons. CAFs, adjacent NOFs and NOFs were isolated as described (22, 23). CAFs were characterized by the expression of α–SMA which was not expressed by the aNOFs or NOFs (Supplementary Fig. S9A-C). The miR-CAFs did not express α–SMA which was expected as it is not a target of the three miRNAs used to reprogram NOFs. Of note, α–SMA is not expressed in all CAFs even though these CAFs are functionally active (24). CAFs activity was validated through functional experiments (increased invasion, migration, colony formation, tumor growth when co-injected with OvCa cells in vivo). Induced (i)CAFs were generated by coculture of NOFs with OvCa cells and miR-CAFs were generated by transfection with LNA anti-miR-214, anti-miR-31 (Exiqon), and pre-miR-155 (Ambion).

Cell Lines

Human ovarian cancer cell lines SKOV3ip1, OVCAR5, and HeyA8 were were validated by STR DNA fingerprinting using the AmpFℓSTR Identifier kit (Applied Biosystems) and compared to known ATCC fingerprints, the Cell Line Integrated Molecular Authentication database (CLIMA), and the MD Anderson fingerprint database.

MicroRNA and Gene Array Analysis

Total RNA was isolated and subjected to both miRNA array (miRCURY LNA array, v. 10.0, Exiqon) and gene array analyses using GeneChip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix). All gene array data are available through GEO (accession numbersGSE35364).

Invasion and Migration

Fibroblasts labeled with CMTPX (Invitrogen) and GFP expressing tumor cells were mixed and seeded in 96-well glass bottom plates coated with growth-factor reduced Matrigel®. Thereafter, upward invasion of cells through Matrigel® towards DMEM with 10% FBS was followed with time lapse confocal microscopy (Supplementary Fig. S2). The speed of the invading cancer cells was analyzed with Imaris Software (Bitplane Inc., Zürich, Switzerland). Migration was quantified using transwell assays (23).

Plug-homing Assay

NOFs transfected with anti-miR-214 and 31 or with equimolar scrambled controls were mixed with 20 μl growth factor reduced Matrigel®. Plugs of anti-miR-214+31 or control transfected NOFs or matrigel alone were placed equidistant in the same culture dish. Alternately, plugs of induced CAFs or NOFs or matrigel alone were used. Homing of GFP labeled cancer cells towards the plugs was monitored using an Axio-observer A1 fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss) and quantified using Image J software (NIH).

Xenograft Experiments

NOFs (1×105 cells) transiently transfected with anti-miR-31, anti-miR-214, and pre-miR-155, or with the scrambled controls for each, were mixed with 0.5×105 HeyA8-Luc cGFP cells and then injected subcutaneously into the flanks of female athymic nude mice. Alternatively, 50,000 CAFs, NOFs, anti-miR-214, anti-miR-31 and pre-miR-155 transfected NOFs or scrambled control transfected NOFs were co-injected with 25,000 HeyA8-Luc cGFP cells into the right ovary of nude mice with 2 μg/ml CCL5 blocking antibody or nonspecific mouse IgG. Mice were subsequently injected with 1 mg/kg CCL5 antibody or IgG control i.p. 3 and 6 days, thereafter. Tumor growth was quantified using the Xenogen IVIS 200 Imaging System. Radiance was measured for tumors on each flank for the subcutaneous model. Total radiance from the tumors in each mouse was measured for the orthotopic, intraabdominal model. Significance was calculated comparing all groups using one way ANOVA.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

The mechanism by which quiescent fibroblasts are converted into cancer associated fibroblasts is unclear. The present study identifies a set of three miRNAs that reprogram normal fibroblasts to cancer associated fibroblasts. These miRNAs may represent novel therapeutic targets in the tumor microenvironment.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Cap (Arthur) Haney (University of Chicago/Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology) for collecting normal omental biopsies and Dr. Anthony Montag (University of Chicago/Department of Pathology) for help with histological analyses. This work was supported by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (E.L.), and the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund to E.L. and M.E.P [PPD/UC/01.12].

Footnotes

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: Functions of cell recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:309–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkan D, Green JE, Chambers AF. Extracellular matrix: A gatekeeper in the transition from dormancy to metastatic growth. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schauer IG, Sood AK, Mok S, Liu J. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and their putative role in potentiating the initiation and development of epithelial ovarian cancer. Neoplasia. 2011;13:393–405. doi: 10.1593/neo.101720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orimo A, Gupta P, Sgroi D, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis throught elevated SDF-1/CXCL 12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schickel R, Boyerinas B, Park SM, Peter ME. MicroRNAs: Key players in the immune system, differentiation, tumorigenesis and cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:5959–74. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambasudhan R, Talantova M, Coleman R, Yuam X, Zhu S, Lipton SA, et al. Direct reprogramming of adult human fibroblasts to functional neurons under defined conditions. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KS. Converting human skin cells to neurons: A new tool to study and treat brain disorders? Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:179–81. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musumeci M, Coppola V, Addario A, Patrizii M, Maugeri-Sacca M, Memeo L, et al. Control of tumor and microenvironment cross-talk by miR-15a and miR-16 in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:4231–42. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Squadrito ML, Pucci F, Magri L, Moi D, Gilfillan GD, Ranghetti A, et al. mir-511-3p modulates genetic programs of tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Rep. 2012;1:141–54. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lengyel E. Ovarian cancer development and metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1053–64. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Whitaker-Menezes D, Pavlides S, Chiavarina B, Bonuccelli G, Trimmer C, et al. The autophagic tumor stroma model of cancer or “battery-operated tumor growth” a simple solution to the autophagy paradox. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4297–306. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aprelikova O, Yu X, Palla J, Wei BR, John S, Yi M, et al. The role of miR-31 and its target gene SATB2 in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4387–610. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowen NJ, Walker LD, Matyunina LV, Logani S, Totten KA, Benigno BB, et al. Gene expression profiling supports the hypothesis that human ovarian surface epithelia are multipotent and capable of serving as ovarian cancer initiating cells. BMC Med Genomics. 2009:2. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsukishiro S, Suzumori NNH, Aarakawa A, Suzumori K. Elevated serum RANTES levels in patients with ovarian cancer correlate with the extent of the disorder. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;102:542–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haniffa MA, Wang XN, Holtick U, Rae M, Isaacs JD, Dickinson AM, et al. Adult human fibroblasts are potent immunoregulatory cells and functionally equivalent to mesenchymal stem cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:1595–604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karnoub A, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, Bell GW, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449:557, 63. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patocs A, Zhang L, Xu Y, Weber F, Caldes T, Mutter GL, et al. Breast-cancer stromal cells with TP53 mutations and nodal metastases. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:2543–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuhkanen H, Anttila M, Kosma VM, Heinonen S, Juhola M, Helisalmi S, et al. Frequent gene dosage alterations in stromal cells of epithelial ovarian carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1345–53. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu W, Hu M, Sridhar A, Opeskin K, Fox S, Shipitsin M, et al. No evidence of clonal somatic genetic alterations in cancer-associated fibroblasts from human breast and ovarian carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2008;40:650–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu M, Yao J, Cai L, Bachman KE, van den Brule F, Velculescu V, et al. Distinct epigenetic changes in the stromal cells of breast cancers. Nat Genet. 2005;37:899–905. doi: 10.1038/ng1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proia DA, Kuperwasser C. Reconstruction of human mammary tissues in a mouse model. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:206–14. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenny HA, Krausz T, Yamada SD, Lengyel E. Use of a novel 3D culture model to elucidate the role of mesothelial cells, fibroblasts and extra-cellular matrices on adhesion and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1463–72. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erez N, Truitt M, Olson P, Arron ST, Hanahan D. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are activated in incipient neoplasia to orchestrate tumor-promoting inflammation in an NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:135–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.