Abstract

Malignancy has become one of the three major causes of death after transplantation in the past decade and is thus increasingly important in all organ transplant programs. Death from cardiovascular disease and infection are both decreasing in frequency from a combination of screening, prophylaxis, aggressive risk factor management, and interventional therapies. Cancer, on the other hand, is poorly and expensively screened for; risk factors are mostly elusive and/or hard to impact on except for the use of immunosuppression itself; and finally therapeutic approaches to the transplant recipient with cancer are often nihilistic. This article provides a review of each of the issues as they come to affect transplantation: cancer before wait-listing, cancer transmission from the donor, cancer after transplantation, outcomes of transplant recipients after a diagnosis of cancer, and the role of screening and therapy in reducing the impact of cancer in transplant recipients.

Cancer is a major cause of death after organ transplantation. Risk factors (besides the use of immunosuppressants) are elusive, screening is limited, and therapies are difficult.

Malignancy has become one of the three major causes of death after transplantation in the past decade and is thus increasingly important in all organ transplant programs. Death from cardiovascular disease and infection are both decreasing in frequency from a combination of screening, prophylaxis, aggressive risk factor management, and interventional therapies. Cancer, on the other hand, is poorly and expensively screened for; risk factors are mostly elusive and/or hard to impact on except for the use of immunosuppression itself; and finally therapeutic approaches to the transplant recipient with cancer are often nihilistic. Here we review the issues as they come to affect transplantation: cancer before wait-listing, cancer transmission from the donor, cancer after transplantation, outcomes of transplant recipients after a diagnosis of cancer, and the role of screening and therapy in reducing the impact of cancer in transplant recipients.

THE POTENTIAL TRANSPLANT RECIPIENT WITH A PREEXISTING DIAGNOSIS OF CANCER

With the exception of a number of patients accepted for liver transplantation because they have a diagnosis of liver cancer (who will not be further considered in this work), the goal of most pretransplant assessment programs is to avoid transplantation of the patient who has had a cancer or who has an occult primary or secondary cancer. The two reasons for avoiding such patients are

-

(1)

because transplantation does not improve and may reduce the patients’ prognosis, and

-

(2)

to avoid placing scarce donated organs into recipients with a limited prognosis.

Patients with chronic kidney, liver, or lung disease are at an increased risk of having had a primary cancer. The relative risk of a patient with chronic kidney disease developing cancer is increased with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of <50 mL/min, men having a 29% increase in cancer risk for every 10 mL reduction in GFR (Wong et al. 2009a). The incidence of cancer is also increased in patients who are commenced on dialysis therapy. A proportion of that excess risk of cancer is not because chronic kidney disease increases cancer risk but because cancer increases or directly causes end-stage kidney failure. Examples are multiple myeloma and renal cell cancers, both of which may lead to kidney failure or in the case of renal cell cancer, to bilateral nephrectomy. It is thus important to remove such end-stage renal failure-associated cancers and examine the risk of the remaining cancers. This has been undertaken in a number of national population-based studies in which the determination of kidney disease status is taken from the dialysis and transplant registries and the cancer data from the national or regional cancer databases, with the two databases then linked at an individual patient level. The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) is a ratio of the number of cancers seen in the study population compared with an age and sex match general population and is the best measure of increased risk because of the strong sex and age relationships for most cancers. An Australian analysis showed that the overall increased risk of a number of cancers in the Australian dialysis population (SIR 1.35), with specific cancers increased substantially such as Kaposi’s sarcoma (SIR 19.6), lip cancer (SIR 1.87), and of course, the renal failure-associated cancers (Vajdic et al. 2006). Table 1 gives a list of the SIRs for different cancers in the predialysis, dialysis, and transplant populations in Australia. It is thus important to consider the risk profile of every patient being assessed for transplantation with particular attention being paid to the past medical history of cancer and any signs, symptoms, or tests that may suggest cancer, such as iron deficiency anemia, a breast lump, or past history of multiple skin cancers.

Table 1.

Risk of cancer in Australians predialysis, during dialysis, and after kidney transplant

| Cancer site (ICD code[s]) | Up to 5 years before RRT | During dialysis | After transplantation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIR | 95% CI | SIR | 95% CI | SIR | 95% CI | |

| Lip (C00) | 1.87 | 1.17–2.83 | 3.68 | 2.46–5.28 | 47.08 | 41.75–52.89 |

| Tongue (C01–C02) | 0.53 | 0.06–1.93 | 3.28 | 1.69–5.72 | 7.17 | 4.38–11.07 |

| Mouth (C03–C06) | 1.34 | 0.43–3.13 | 2.15 | 0.98–4.08 | 4.58 | 2.51–7.69 |

| Salivary gland (C07–C08) | 2.11 | 0.57–5.40 | 1.2 | 0.15–4.34 | 7.71 | 3.33–12.20 |

| Esophagus (C15) | 1.05 | 0.28–2.68 | 1.68 | 0.96–2.74 | 3.82 | 2.26–6.03 |

| Stomach (C16) | 0.81 | 0.35–1.60 | 1.52 | 1.01–2.19 | 1.84 | 1.07–2.94 |

| Small intestine (C17) | 1.25 | 0.15–4.53 | 3.06 | 1.12–6.67 | 1.73 | 0.21–6.25 |

| Colon (C18) | 1.33 | 1.06–1.65 | 1.18 | 0.93–1.47 | 2.36 | 1.87–2.92 |

| Rectum (C19–C20) | 1.33 | 0.98–1.77 | 1.02 | 0.72–1.40 | 0.63 | 0.33–1.07 |

| Anus (C21) | 0.33 | 0.07–0.96 | 0.23 | 0.03–0.82 | 2.76 | 1.51–4.64 |

| Liver (C22) | 2.87 | 0.78–7.34 | 2.25 | 1.23–3.77 | 3.19 | 1.53–5.87 |

| Gallbladder (C23–C24) | 0 | - | 1.55 | 0.67–3.05 | 4.34 | 2.16–7.76 |

| Pancreas (C25) | 2.16 | 0.87–4.45 | 1.17 | 0.69–1.85 | 1.21 | 0.56–2.30 |

| Larynx (C32) | 0.96 | 0.42–1.90 | 1.02 | 0.41–2.11 | 2.1 | 0.96–3.98 |

| Trachea; bronchus and lung (C33–C34) | 1.07 | 0.74–1.49 | 1.59 | 1.33–1.88 | 2.45 | 2.00–2.97 |

| Melanoma (C43) | 1.02 | 0.81–1.27 | 1.06 | 0.81–1.38 | 2.53 | 2.08–3.05 |

| Mesothelioma (C45) | 0.61 | 0.02–3.37 | 1.73 | 0.75–3.40 | 1.32 | 0.27–3.85 |

| Kaposi sarcoma (C46) (Nalesnik et al. 2011) | 19.64 | 4.05–57.40 | 57.88 | 21.24–125.98 | 207.9 | 113.66–348.82 |

| Connective and other soft tissue (C47–C49) | 0.49 | 0.06–1.78 | 1.26 | 0.41–2.93 | 4.13 | 2.13–7.21 |

| Breast (C50) (incl. males) | 0.91 | 0.71–1.14 | 1.25 | 0.99–1.55 | 1.03 | 0.78–1.34 |

| Vulva (C51) | 1.57 | 0.19–5.67 | 1.59 | 0.19–5.73 | 24.54 | 14.55–38.79 |

| Cervix uteri (C53) | 1.6 | 0.80–2.86 | 2.58 | 1.38–4.42 | 2.49 | 1.33–4.27 |

| Corpus uteri (C54) | 1.53 | 0.92–2.40 | 1.07 | 0.53–1.91 | 1.74 | 0.92–2.97 |

| Ovary (C56) | 0.78 | 0.25–1.82 | 1 | 0.43–1.98 | 1.15 | 0.46–2.38 |

| Penis (C60) | 1.29 | 0.03–7.16 | 4.72 | 0.97–13.80 | 15.94 | 5.85–34.69 |

| Prostate (C61) | 1.16 | 0.98–1.36 | 0.66 | 0.52–0.83 | 0.95 | 0.68–1.29 |

| Testis (C62) | 2.1 | 0.77–4.57 | 0.71 | 0.02–3.94 | 1.25 | 0.34–3.20 |

| Eye (C69) | 2.1 | 0.68–4.91 | 1.22 | 0.15–4.39 | 7.57 | 3.46–14.36 |

| Brain (C71) | 0.19 | 0.00–1.07 | 1.1 | 0.59–2.05 | 0.57 | 0.16–1.46 |

| Thyroid (C73) | 2.57 | 1.44–4.24 | 9.23 | 6.53–12.67 | 6.9 | 4.69–9.79 |

| Hodgkin disease (C81) | 1.28 | 0.26–3.75 | 2.56 | 0.70–6.54 | 3.75 | 1.51–7.73 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (C82–C85) | 1.51 | 1.05–2.10 | 1.36 | 0.94–1.90 | 9.86 | 8.37–11.54 |

| Leukemia (91–95) | 0.89 | 0.51–1.44 | 1.14 | 0.74–1.77 | 2.46 | 1.65–3.67 |

Data adapted from Vadjic et al. 2006.

CI, confidence interval; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

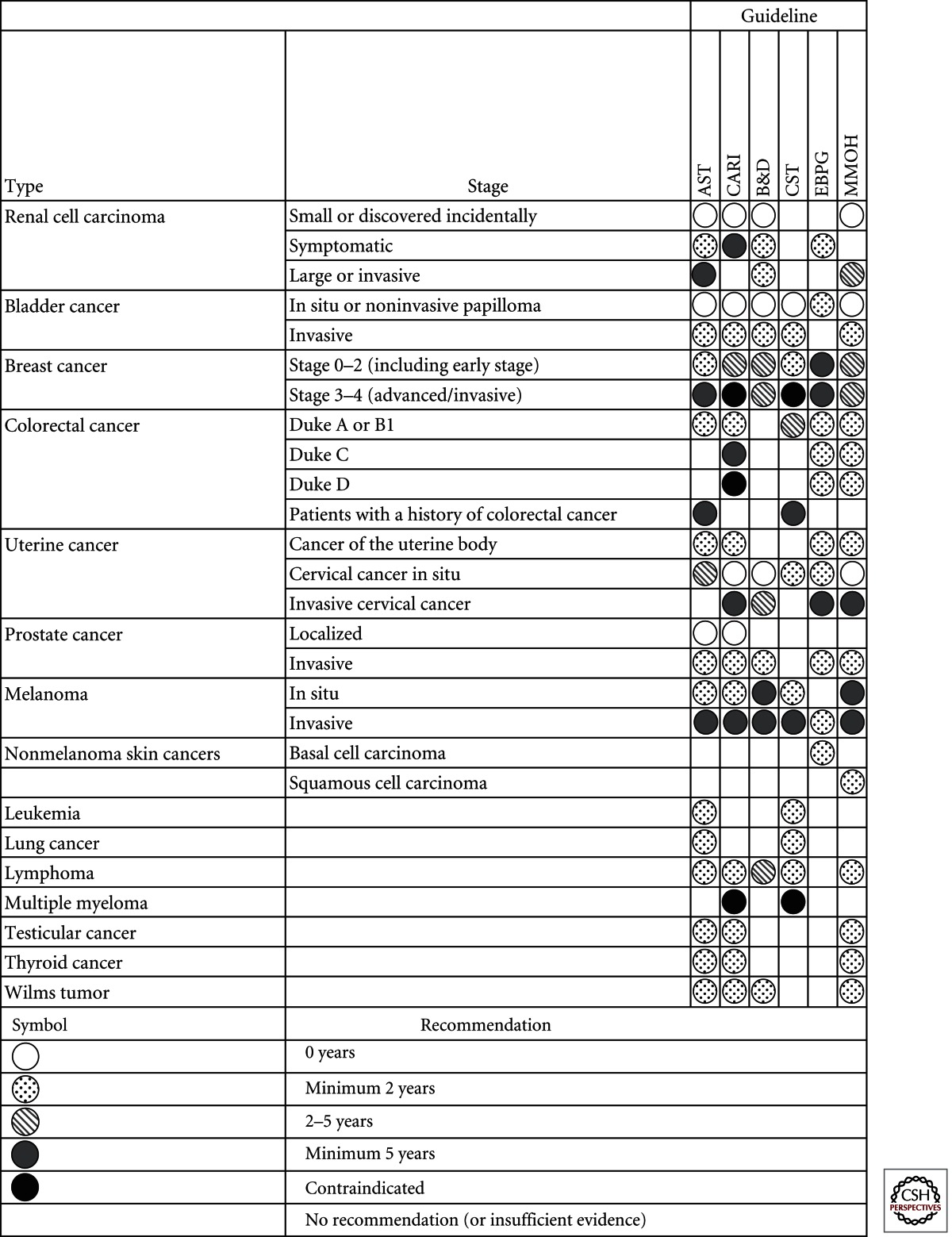

The main problem that transplant units must contend with is the patient with a definite history of cancer at some time before consideration for wait-listing for transplantation. Will the cancer return or metastasize and will immunosuppression increase that chance? These are the fundamental questions that must be considered for each individual patient. Each cancer is different and the stage of the cancer and type of treatment given, as well as the time from the diagnosis to the proposed transplantation need consideration. There are no certain answers to these questions, even when one knows the particular circumstances for an individual recipient, yet each set of transplant assessment clinical practice guidelines provides a clear answer for the most common cancers (Table 2) (Knoll et al. 2005; Batabyal et al. 2012). The word “guideline” must be respected carefully because these are merely guidelines to the normal behavior of a particular cancer type and the expected outcomes under immunosuppression. Cancers that are uninfluenced by immunosuppression can perhaps be considered differently to those that are heavily impacted, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma or lymphomas, but there is no substitute for the potential recipient’s oncologist defining the chance of recurrence or metastasis.

Table 2.

Guidelines for the minimum time interval between diagnosis and treatment of a cancer and the transplantation

Analysis adapted from Batabyal et al. (2012).

Early breast cancer was defined as Stages 0–2 and advanced breast cancer as Stages 3–4, according to the NHMRC clinical practice guidelines and International Union against Cancer’s TMN classification system. B&D, EBPG, and MMOH guidelines did not define breast cancer stage. EBPG and MMOH guidelines did not define colorectal cancer stage.

AST, American Society of Transplantation (Kasiske et al. 2001); CARI, caring for Australasians with renal impairment (CARI Guidelines 2011); B&D, Bunnapradist and Danovitch (2007); CST, Canadian Society of Nephrology (Knoll et al. 2005); EBPG, European Best Practice Guidelines (EBPG 2000); MMOH, Malaysia Ministry of Health (MMOH 2009).

THE DONOR WITH PREEXISTING CANCER

There are sporadic reports of cancer being transmitted through organ donation in the 1970s, with the issue being championed by Penn (1993) and his colleagues through voluntary data collection and reporting. The rate at which different cancers were transmitted from donor to recipient gave rise to a donor selection strategy, which specifically included deceased organ donors with, for example, cerebral malignancy, but excluded all donors with a history of malignant cancer capable of metastasis. The experience of the last two decades has been driven, on the one hand, by selective risk taking, and on the other, by risk avoidance. The risk taking has been through active selection of donors with a known previous medical history of cancers that are likely to be cured; for example, a donor with a resected early-stage colon cancer several years before the proposed donation. The risk aversion, on the other hand, has been to separate the various cerebral malignancies into low and high risk and avoid donors with high-grade gliomas or with prior surgical interventions that increase the risk of extracerebral metastasis.

Deceased Donors with a History of Cancer

The major problem with an evidence-based strategy for avoiding the risk of cancer transmission from organ donation has been first that there will of course never be a randomized study, and second, the incidence of any cancer transmission is so low that sporadic case reports are the main source of information. The publication bias against single case reports means that this source of data is highly likely to underestimate the true incidence, and the low frequency and very variable stage of cancers mean that definitive risk calculations are impossible. A list of cancers that are reported to have been transmitted is shown in Table 3. The common features are cancers of the organ being transplanted—especially, renal cell carcinomas; and cancers with a high propensity for metastasis to the organs being donated.

Table 3.

Cancers known to have been transmitted from donor to recipient on at least one occasion

| Cancers |

|---|

| Breast cancer |

| Choriocarcinoma |

| Colon cancer |

| Glioblastoma multiforme |

| Liver cancer |

| Lung cancer |

| Lymphoma |

| Melanoma |

| Neuroendocrine |

| Ovarian carcinoma |

| Pancreas |

| Prostate |

| Renal cell carcinoma |

| Thyroid carcinoma |

There have been initiatives designed to ensure reporting of cancers that may have been transmitted by the donated organ in the U.S. and European environments. At a global level there is now a World Health Organization sponsored website (www.notifylibrary.org) to provide for a curated library of reported donor-related adverse events and incidents, including both transmitted infection and malignancy. These efforts have helped define the lexicon—for example, what evidence is required to impute that a cancer in a recipient has been transmitted from the donor, as opposed to developed in the transplanted organ? A renal cell cancer in a transplanted kidney may or may not have been present in the organ at donation. If there is DNA evidence that the tumor is of donor origin and other recipients of organs from the same donor have also suffered from the same renal cell cancer, then one may designate the event as a proven donor-transmitted cancer. If the time between transplantation and donation is short, for example, a matter of weeks, then it is highly probable that the cancer is donor transmitted. On the other hand, if the time delay is several years between the donation and the cancer diagnosis, it is more likely that it has developed in situ and thus donor derived.

There have been a number of approaches to guidance on the acceptance of risk of donor-derived disease including the U.S. Donor Transmitted Assessment Committee (DTAC) and the Council of Europe (Nalesnik et al. 2011). Table 4 shows the DTAC framework for consideration of risk of donor-transmitted disease that allows physicians and recipients to consider the specific issues related to a particular donor. The DTAC has assessed the stratification of different malignancies into the various risk bands and has provided a useful resource for such decision making (Nalesnik et al. 2011).

Table 4.

Framework for classification of the risk of transmission of donor disease, from the U.S. Donor Transmission Advisory Committee (DTAC)

| Risk category | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| No significant risk | Standard |

| Minimal | Clinical judgment with informed consent |

| Low | Use in recipients at significant risk without transplant; informed consent required |

| Intermediate | Use of these donors is generally not recommended. On occasion, a lifesaving transplant may be acceptable in circumstances in which recipient expected survival without transplantation is short (e.g., a few days or less); informed consent required |

| High | Use of these donors is discouraged except in rare and extreme circumstances; informed consent required |

| Unknown risk | Use should be based on clinical judgment with informed consent |

Living Donor Assessment for Cancer Risk

The first reported case of cancer transmission from a living organ donor was a breast cancer transmitted from a donor wife to recipient husband, but lung, lymphoma, and renal cell cancer have also been recorded (Kauffman et al. 2002). The young age of most living organ donors provides a degree of protection against cancer transmission because of the strong age-associated risk of cancer; however, many of the common cancers such as breast, colon, prostate, cervix, and in Australia also melanoma, are sufficiently prevalent that one case might be expected to be transmitted unknowingly every 5000 living donations. Screening of living donors for these cancers should thus be part of routine assessment.

DE NOVO MALIGNANCY AFTER TRANSPLANTATION

Cancer is a major source of morbidity and mortality following solid organ transplantation. Overall risk of cancer is increased between two- and threefold compared with the general population of the same age and sex. Recipients of solid organ transplants typically experience cancer rates similar to nontransplanted people 20–30 years older, and risk is inversely related to age, with younger recipients experiencing a far greater relative increase in risk compared with older recipients (risk increased by 15–30 times for children, but twofold for those transplanted >65 years) (Webster et al. 2007). Posttransplant cancer risk is increased ∼40% for those with a prior cancer, and similarly by white race. Overall, diabetics may experience fewer cancers, but this may be owing to the competing risk of an increased burden of cardiovascular disease (i.e., diabetics may succumb to heart disease before they develop cancer).

However, risk does vary by cancer site, and in applying evidence in clinical practice it is wise to be aware that when thinking about absolute risk, even a small relative risk increase for a common cancer may be more important to consider for some patients than a large relative risk of an uncommon cancer (Table 1). Reasons for the increased risk of most cancers after transplantation are likely owing to the interplay of several factors: the organ transplanted, prior and new exposure to viral infections, total load and duration of immunosuppression, perhaps the specific components of the immunosuppressive regimen, and the recipients accumulated baseline exposures known to increase cancer risk in the general population.

Variation in Cancer Risk According to Transplanted Organ

Table 5 summarizes the published standardized incidence ratios (SIR) for several different cancer sites, stratified by transplanted organ, taken from national population-based studies (Kyllönen et al. 2000; Adami et al. 2003; Vajdic et al. 2006; Villeneuve et al. 2007; Collett et al. 2010; Jiang et al. 2010; Engels et al. 2011; Na et al. 2013). SIR can be interpreted as relative risk, as they estimate risk for organ recipients relative to the cancer incidence experienced by the general population, after allowing for differences in age, sex, and year of diagnosis. For each cancer site, the magnitude of increased risk is largely similar across different countries, and where differences exist, this is largely attributable to era of study and methodology of calculation. However, although the overall risk for all-site cancer is of similar magnitude across organ recipients, the incidence of specific cancers does vary by transplanted organ. In general, kidney cancer risk is greatest for kidney recipients (increased approximately eightfold), and similarly, risk of lung cancer is highest for lung recipients (approximately fivefold risk), and liver cancer for liver recipients (although here, given that liver cancer is an indication for liver transplantation, interpretation is not straightforward). Risk of non-Hodgkins lymphoma, or posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD), is elevated by >5 times for all organ recipients, but the magnitude of risk is by far the greatest for lung and heart recipients compared with those who receive other solid organs (Table 5) (Opelz and Döhler 2004).

Table 5.

Risk of cancer by organ for some cancer sites, expressed as standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) relative to the general population of each country

| Site and comparator national population | SIRs with 95% confidence intervals for different organ transplant recipients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | Liver | Heart | Lung | |

| All site | ||||

| Australia | 3.3 (3.1–3.7) | 2.3 (1.9–2.7) | 2.7 (2.4–3.0) | 4.3 (3.5–5.2) |

| Canada | 2.5 (2.3–2.7) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | ||

| Finland | 3.3 (2.9–3.8) | |||

| Sweden | 3.9 (3.6–4.2) | 4.9 (3.7–6.4) | ||

| United Kingdom | 2.4 (2.3–2.5) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | 2.5 (2.2–2.7) | 3.6 (3.0–4.4) |

| United States | 2.10 (2.06–2.14) | |||

| Nonmelanoma skin cancer | ||||

| Finland | 39.2 (29.3–51.4) | |||

| Sweden | 57.7 (51.0–65.1) | 34.0 (17.0–60.6) | ||

| United Kingdom | 16.6 (15.9–17.3) | 6.6 (5.8, 7.5) | 18.5 (16.9, 20.3) | 16.1 (13.1, 19.6) |

| Lip | ||||

| Australia | 47.1 (41.8–52.9) | 14.0 (7.0–25.1) | 27.5 (19.0–38.4) | 41.9 (22.3–71.6) |

| Canada | 31.3 (23.5–40.8) | |||

| Finland | 22.9 (12.6–38.6) | |||

| Sweden | 54.8 (39.0–74.9) | 24.8 (0.6–138.6) | ||

| United Kingdom | 65.6 (49.9–84.6) | 20.0 (5.4–51.2) | 60.0 (31.0–104.8) | |

| United States | ||||

| Non-Hodgkins lymphoma | ||||

| Australia | 9.9 (8.4–11.5) | 5.6 (3.6–8.3) | 7.0 (5.0–9.5) | 16.8 (11.1–24.4) |

| Canada | 8.8 (7.4–10.5) | 22.7 (17.3–29.3) | ||

| Sweden | 3.8 (2.5–5.6) | 37.3 (22.1–59.1) | ||

| United Kingdom | 28.3 (11.2–13.8) | 13.3 (10.6, 16.6) | 19.8 (16.1, 24.1) | 30.0 (20.6, 42.1) |

| United States | 7.54 (7.2–7.9) | |||

| Colorectal | ||||

| Australia | 2.4 (1.9–2.9) | 2.4 (1.5–3.7) | 1.0 (0.5–1.6) | 2.6 (1.1–5.1) |

| Canada | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 0.6 (0.2–1.5) | ||

| Finland | 3.9 (2.1–6.7) | |||

| Sweden—colon only | 2.4 (1.5–3.5) | |||

| United Kingdom | 1.8 (1.2–2.1) | 2.3 (1.7–3.0) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.1 (0.3–2.9) |

| United States | 1.24 (1.2–1.3) | |||

| Lung | ||||

| Australia | 2.5 (2.0–3.0) | 0.5 (0.1–1.4) | 2.2 (1.4–3.2) | 3.8 (1.7–3.5) |

| Canada | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) | 2.0 (1.2–3.0) | ||

| Sweden | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | |||

| United Kingdom | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 2.1 (1.6–2.8) | 5.9 (3.7–8.8) |

| United States | 2.0 (1.9–2.1) | |||

| Breast (female) | ||||

| Australia | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 1.3 (0.6–2.2) | 0.5 (0.1–1.9) | 0.8 (0.2–2.2) |

| Canada | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.1 (0.2–3.2) | ||

| Sweden | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | |||

| United Kingdom | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.8 (0.3–1.7) | 0.3 (0.0–1.2) |

| United States | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | |||

| Prostate | ||||

| Australia | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 0.7 (0.2–2.1) |

| Canada | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.3 (0.7–2.2) | ||

| Sweden | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | |||

| United Kingdom | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | |||

| United States | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | |||

Australia (Vajdic et al. 2006; Na et al. 2013); Canada (Villeneuve et al. 2007; Jiang et al. 2010); Finland (Kyllönen et al. 2000); Sweden (Adami et al. 2003); United Kingdom (Collett et al. 2010); United States (Engels et al. 2011).

Variation in Risk by Cancer Site

The magnitude of cancer risk varies by cancer site. Registry data from around the world has established that the pattern of increase in risk for cancer at different sites is seen consistently (Kyllönen et al. 2000; Adami et al. 2003; Vajdic et al. 2006; Villeneuve et al. 2007; Collett et al. 2010; Jiang et al. 2010; Engels et al. 2011; Na et al. 2013). Cancers that are very greatly increased in the transplanted populations are nonmelanoma skin cancer and lip cancer (>10-fold increased risk), Kaposi sarcoma (>50-fold increased risk), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (greater than eightfold increase), and cancers of the anogenital tract (greater than fourfold increase for vaginal, cervical, vulval, anal, and penile cancers). Other cancers have only a moderately increased relative risk in transplant recipients, but because they occur moderately frequently in the general population, the result of a small relative increase is clinically important. Examples are colorectal cancer (∼40% increase), melanoma (approximately double risk), and lung cancer (>50% increase). Cancer at more than 20 other sites also show significant increased risk, including head and neck, thyroid, esophagus, stomach, leukemias, and plasma cell tumors. Notable cancers that do not show an increase in risk for organ transplant recipients are breast cancer and prostate cancer.

Skin cancers, specifically basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers, are common after transplantation, and incidence increases with time. Australian estimates in kidney recipients found 50% experienced at least one skin cancer by 10 years and 80% by 20 years after transplantation (Ramsay et al 2002). Accurate estimates of risk relative to the general population are challenging to generate, and most national cancer registries do not record skin cancers, thus understanding incidence in the general population is not straightforward. However, best estimates are that organ recipients risk of basal cell cancer is 10-fold, and squamous cell up to 100-fold; squamous cell cancers exceed basal cell cancers by 4:1, a reversal of the situation in the general population. This excess risk is modified by skin pigmentation, such that black recipients have much reduced risk compared with white recipients.

The Role of Viral Infection in Carcinogenesis after Transplantation

It is widely recognized that virus infection is implicated in a number of cancer sites in the general population, and also through study in patients with acquired immune dysfunction such as those with HIV and AIDS. Transplant patients are vulnerable to viral infection or reactivation of latent infection. Viruses implicated in carcinogenesis include Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8), human papillomavirus (HPV), the Merkel cell polyomavirus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. The rapidity with which some malignancies develop after transplantation also is consistent with the concept that viral oncogenesis is involved because initiation of immunosuppression may promote unchecked viral replication. There is also evidence in kidney recipients that after transplant failure and reduction or cessation of immunosuppression, the risk of virus-related cancers decreases back to levels seen in pretransplant dialysis patients (Van Leeuwen et al. 2010).

EBV is implicated in the development of Hodgkins disease, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and other manifestations of PTLD, as well as nasopharyngeal cancers and leiomyosarcomas. EBV is common in the general population, and in most parts of the world 90% of adults will show serological evidence of exposure. The classification of PTLD has changed over time as understanding has evolved. Current classification is the 2008 WHO system (Swerdlow et al. 2008). Lymphoma is among the most frequent cancers experienced by transplant recipients, and for the majority (but not all), EBV can be shown in the tumor tissue. Approximately 80% of all PTLD arises from B-cell proliferation induced by EBV. The remaining 20% of PTLD arises predominantly from T cells, about one-third of which have implicated EBV in causation. The majority of PTLD arise within two years of transplantation, with a further later peak of incidence beyond five years. Principal risk factors for PTLD include negative EBV serostatus at the time of transplantation (which means children are particularly vulnerable), and the degree of immunosuppression, particularly anti-T-cell agents, which impair EBV-specific T-cell-mediated immune surveillance. PTLD may arise in donor tissue, and it is not uncommon for PTLD to arise in proximity to the transplanted organ. Recipients of kidney transplants are more likely to get renal lymphoma than recipients of heart transplants; similarly heart transplant recipients more commonly get cardiac or thoracic PTLD than kidney recipients (Opelz and Döhler 2004).

HHV8 is associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma, as well as primary effusion lymphoma, and has been implicated in multiple myeloma. HHV8 infection prevalence shows geographical variation, being more common in Mediterranean and African regions where 30%–50% of the general population shows serological evidence of infection, whereas prevalence is 20% in Southeast Asia and Northern Europe. In the immunocompetent, Kaposi’s sarcoma is an indolent cutaneous disease that rarely disseminates; however, under immunosuppression disease is more aggressive, more frequently multicentric, and visceral involvement is more common. Visceral involvement is more likely in heart and lung recipients (up to 50% of cases) compared with kidney recipients. HHV8 is present in tumor tissue and there is usually serological evidence of infection. The main risk factor for posttransplant Kaposi’s sarcoma is origin from an area of high seroprevalence, but there is also a male:female ratio of 3:1. Tumor cells may also be donor derived, and HHV8 infection may be transmitted from donor to recipient. Initial treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma is reduction of immunosuppression, which usually prompts regression.

HPV is associated with anogenital cancers including cervical, vaginal, vulval, penile, and anal cancers, head and neck cancer, and is implicated in squamous cell skin cancers. Cancer risk at all of these sites is increased in organ transplant recipients. HPV has multiple genotypes, and different subsets are associated with different cancers. The role of HPV is supported by HPV DNA being found in cancers and precancers at these sites. Anogenital cancers often occur together (for example, cervical and vulval, or penile and anal), and may manifest as extensive or multiple lesions. Transmission of HPV is by close personal contact, including sexual contact for anogenital infection, and is commonly asymptomatic.

Merkel cell carcinoma is increased in transplant recipients and people with HIV but is very rare in the general population. It is an aggressive, predominantly intradermal, neuroendocrine malignancy, known for local recurrence and lymph node metastases. Merkel cell polyomavirus can be detected in >80% of tumors.

Chronic hepatitis B infection is associated with development of hepatocellular carcinoma, risk is exacerbated by coinfection with hepatitis C, and increased further posttransplantation as immunosuppression promotes viral replication.

THE ROLE OF COMPONENTS OF THE IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE REGIMEN

Overall cancer risk is moderated by duration and intensity of immunosuppression, rather than individual components of the drug regimen. This view is given weight by equivocal and contradictory findings in a range of studies of risk factors for cancer after transplantation, which have failed to consistently show association of overall increased cancer risk with any specific drug. Indirect evidence for this view is that some studies have shown that episodes of acute rejection within the first year posttransplant confer increased risk of subsequent malignancy. Those recipients experiencing acute rejection are treated by pulses of increased immunosuppression, thus increasing their immunosuppressive burden overall. It is possible that small differences of effect do exist among drugs, but that these are outweighed by the far greater effects of other known risk factors for cancer, such as age, sex, history of smoking, underlying disease leading to transplantation, and history of prior cancers (Webster et al. 2007; Gallagher et al. 2010). Given the large effect of these known risk factors and the need to balance long-term cancer risk against recipient and graft survival, any small differences among drugs are likely to be clinically unimportant.

In vitro studies suggest calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine and tacrolimus promote carcinogenesis, potentially through production of cytokines that regulate tumor growth (such as transforming growth factor-β), metastasis, and angiogenesis. However, differences among recipients taking cyclosporine versus those that are not has not resulted in differences in cancer in long-term trials (Gallagher et al. 2010).

Azathioprine acts on DNA and RNA mechanisms, inhibiting repair of splicing and ultimately disrupting lymphocyte proliferation. When used as a single agent to treat autoimmune diseases, azathioprine is associated with an increased risk of lymphomas and an increased risk of a wide range of solid neoplasms, including squamous cell carcinomas, urinary bladder tumors, breast carcinomas, and brain tumors. However, in organ transplant recipients, comparing immunosuppression regimens with and without Azathipoprine has not resulted in differences in cancer incidence (Gallagher et al. 2010). Mycophenolate was originally developed as an anticancer drug, and acts through blockage of the purine biosynthesis, inhibiting inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase. In transplant registry studies mycophenolate-containing regimens have not shown differences in cancer rates compared with mycophenolate-free regimens, but do suggest lower rates of acute rejection.

Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (MTORi) sirolimus and everolimus act by blocking T and B lymphocytes proliferation by preventing activation of the mTOR, which then halts the progression from the G1 to the S phase of the cell cycle. In addition, mTORIs also inhibit the translation of transcription factors resulting in reduced angiogenesis, preventing the multiprotein complexes (mTORC1 and mTORC2) pathway activation, thereby halting cell proliferation, particularly in the setting of cancer development (Guba et al. 2004). MTORi have antineoplastic properties, and show promise in reducing cancer recurrence while permitting ongoing immunosuppression (Law 2005). However, it is still not clear whether MTORi-containing regimens have any benefit in reducing de novo cancer risk.

For some specific cancers, lymphocyte-depleting antibodies such as antithymocyte globulin preparations may be implicated in causality. These agents appear to consistently increase risk of early EBV-driven PTLD (Opelz and Döhler 2004).

SURVIVAL AND OUTCOMES IN TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS WITH CANCER

Not only does the risk of developing de novo cancer increase after kidney transplantation, the prognoses of recipients diagnosed with cancer is much worse than patients with transplants or cancer alone. Data from the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry have shown that transplanted women with breast cancer have an excess mortality of at least 40% compared with women with breast cancers in the general population. For men with colorectal cancers and kidney transplant, the overall 5-year survival is 27% compared with 75% for those in the general population with cancer but without transplants (Webster and Wong 2008).

In a Dutch kidney transplant population, the median patient survival after the diagnoses of cancer was only 2.7 years, compared with an average survival of recipients without cancer of 8.3 years (p < 0.0001) (van de Wetering et al. 2010). Cancers developed in transplant recipients were often more aggressive and developed at a much later stage than patients without transplants. Recent data from the Israel Penn Registry showed that the stage-specific survival for certain cancer types such as colon, lung, breast, prostate, and bladder cancers was significantly lower in patients with transplants compared with those in the general population (Miao et al. 2009).

On the contrary, using the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) cohort, a higher standardized cancer mortality ratio was observed only in younger recipients without a competing cardiovascular risk factor such as diabetes. Among older transplant recipients with diabetes, heart disease, and prior stroke, the overall standard mortality ratios for cancer are much lower than that in the age and gender matched general population. The interpretation is that the potential competing risk of death from cardiovascular disease dampens the effect of immunosuppression on cancer risk in older transplant recipients (Kiberd et al. 2009).

Reasons for the poorer cancer outcomes in kidney transplant recipients are unclear. Previous studies have shown that patients with chronic kidney disease are less likely to receive cancer screening because of the perceived reduced survival benefits compared with people without kidney disease, leading to the development of aggressive, more advanced stage disease at the time of cancer diagnoses. Transplant clinicians may also be reluctant to instigate intensive chemotherapeutic treatment and surgical intervention because of coexisting comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease. The fear of rejection and potential graft loss may also prevent the introduction of immunotherapy and withdrawal/reduction in immunosuppression.

INTERVENTIONS TO IMPROVE CANCER OUTCOMES AND SURVIVAL

In view of the higher cancer incidence and poorer prognoses, prevention and screening may play an important role in reducing the burden of cancer in kidney transplant recipients. Routine cancer screening is recommended for all transplant individuals. Recommendations for cancer screening in transplant recipients are mostly extrapolated from the general populations and are consistent with screening guidelines in the general population, with the exception of cervical, skin, colorectal, and renal cancers.

Screening for Cervical Cancer

The overall incidence of cervical cancers in women who received a kidney transplant is at least two to three times greater than the age and gender matched population. Despite the lack of evidence from screening trials in transplant recipients, current recommendations suggested more frequent cytologic screening (annual instead of biannual) because of the belief that precancerous lesions may progress more rapidly under the influence of immunosuppression. Apart from clinical effectiveness, recent modeled analyses reported that routine annual screening is cost-effective in women with kidney transplants, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) in the order of $12,000 per life year saved and total gains of 0.05 life years per women screened. On the contrary, implementing HPV vaccination in HPV naïve women under the existing screening program is expensive, and may add only modest benefits. A program of HPV vaccination and screening would have to vaccinate a total of 1000 HPV naïve women before transplantation, to save one extra death from cervical cancers over a screening period of 50 years (Wong et al. 2009b). Although the bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines appear promising in reducing the incidence of HPV-16 and -18 cervical dysplasia among the general population, there is a lack of trial data showing the immunogenicity and effectiveness of HPV vaccination in immunosuppressed individuals.

Screening for Breast Cancer

Biennial mammographic screening for breast cancer is standard practice in the general population. The American Transplant Society (AST) and the European Best Practice Guidelines (EBPG) recommend breast cancer screening in all female transplant recipients between 50 and 69 years of age (Kasiske et al. 2000, 2001; European Best Practice Guidelines for Renal Transplantation 2002). For women between 40 and 49 years of age, transplanted women could still undergo screening annually or biennially. However, evidence for or against screening in this group of transplanted women remains unclear. Transplanted women undergoing screening mammography should also be aware of the potential false-positive findings, particularly in women who developed large, dense, and multiple benign breast adenomas from long-term cyclosporine use. False-positive findings will lead to unnecessary and exhaustive diagnostic procedures such as fine-needle and core biopsies of the breasts.

Screening for Bowel Cancer

There is now consistent evidence showing an increased risk of colorectal cancer by at least two- to threefold among those with renal allografts. However, recommendations for screening bowel cancer are far from being standardized across the various different transplant practice guidelines groups. The AST recommends annual fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years in the United States (Kasiske et al. 2000, 2001). In Australia, biennial screening using the immunochemical FOBT is the recommended screening tool by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). In Europe, the EBPG suggested annual screening for all transplant recipients using iFOBTs. All positive screening tests need to be followed by diagnostic colonoscopies (European Best Practice Guidelines for Renal Transplantation 2002).

Although there is to date, no trial-based evidence for cancer screening in this at-risk population, early cancer detection is effective. Previously modeled analyses have shown that colorectal cancer screening is probably effective in transplanted patients, but uncertainties exist; in particular, the costs, the test specificity, and the patient preferences for screening in patients with comorbidities (Wong et al 2008). A recent diagnostic test accuracy study conducted in a South Australian cohort of transplanted recipients suggested that the test sensitivity of immunochemical FOBT may be low at 36% compared with the expected test performance characteristics in the nontransplanted populations (Collins et al. 2012).

Screening for Skin Cancers

Skin cancer is the most common form of cancer in transplanted patients. Skin cancer prevention with sun-protective behaviors such as using sunscreen (SPF 15+), sun hats, avoidance of exposure to ultraviolet radiation during sun-peak hours, and covering up with pants and long-sleeve tops are effective measures to reduce the incidence of skin cancers and should be encouraged. Transplant follow-up combined with regular skin surveillance by experienced dermatologists should be advocated for all transplant units. Prophylactic treatment with retinoid acitretin or low-dose capecitabine in the secondary prevention of skin cancers appears to be efficacious in reducing the incidence rates of squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients with manageable toxicity profile, but the use of these agents remains heterogenous.

Screening for Renal Cancers

Screening for urinary tract cancers using ultrasonography may be useful for high-risk patients such as those with a history of analgesic use or acquired cystic disease of the kidneys, but may not be cost-effective for all recipients of kidney transplants. A major concern associated with ultrasonographic screening is the test performance characteristics of the screening tool. The accuracy of ultrasonography is an important determinant of screening efficiency, but is uncertain in recipients of kidney transplants. Ultrasonography is not only operator dependent but performance varies with the size and morphology of the patient, the kidneys, and the tumor. The difficulties associated with ultrasonographic screening in people with ESKD include the effect of multicystic diseases and small scarred native kidneys on the overall test accuracy and poor reliability in differentiating small hyperechoic renal cancers from lesions such as adenomas and angiomyolipomas (Bunnapradist and Vincenti 2009; Wong et al. 2011).

MANAGEMENT OF CANCER IN KIDNEY TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

Surgical resection and radiotherapy remain the preferred treatment for most early-stage and locally invasive tumors among transplanted patients. Although there is a lack of trial-based evidence, judicious reduction in immunosuppression with regular monitoring of disease progression and graft function may be warranted, particularly among those with high-grade and advanced disease.

Over the past decades, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORI) have been proposed to have a dual role in transplantation: immunosuppression and antioncogenic activities for transplanted patients. From the clinical perspective, retrospective analyses have shown reduced incidence of de novo cancer among those who received mTORIs as immunosuppression compared with recipients on calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs). Post hoc analyses of immunosuppression trials such as the CONVERT have shown a reduction in the incidence of skin cancer in the sirolimus cohort compared with those remaining on CNIs (Bunnapradist and Vincenti 2009; Alberú et al. 2011).

More recently, two randomized controlled trials have been conducted in kidney transplant recipients designed specifically to evaluate the effectiveness of mTORI as immunosuppressive agents in the context of malignancy. In the Australian study, a total of 96 kidney transplant recipients were randomized to receive maintenance CNIs or conversion to mTORIs. With a median follow-up period of 3.6 years, the overall incidence of new squamous cell skin cancer (SCC) among patients with a prior history of skin cancer was significantly lower than those on CNIs (0.88 versus 1.71 per-patient year, p = 0.038) (Campbell et al. 2012). A similar study, conducted in Lyons, France, randomized 120 high-risk transplanted patients with a prior history of SCCs reported a lower proportion of transplant recipients developed new SCCs in the mTORI group compared with those in the CNIs group. (47.6% vs. 70.5%, p = 0.048). However, poor tolerability of mTORI remains a major concern (Euvrard et al. 2012). More than 35% of transplant recipients discontinued mTORI treatment owing to significant side effects such as ankle swelling, acne, pneumonitis, and proteinuria, and infective complications have prevented the longer-term use of mTORI in these high-risk groups.

Therapeutic measures (both preventive and therapeutic) for melanomas are less well studied. Other novel treatment strategies for metastatic melanoma such as the antiangiogenic and immunomodulatory drugs, the proteasome inhibitors, and the specific targeted molecular therapies have been implicated in the general population (Simeone and Ascerto 2012). However, the efficacy and safety of using these newer agents are unclear and unproven in the transplant population.

mTORI have also been shown to be effective in achieving successful clinical and histological remission of Kaposi sarcoma. Previous studies have shown that phase II and III trials have shown antitumor activity and survival advantage in patients with metastatic renal cancers treated with mTORI (Rao et al. 2004; Baldo et al. 2008; Amato et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2011). In the transplant population, the clinical effectiveness of mTORI for the prevention and treatment of renal cell carcinomas remained unclear.

Footnotes

Editors: Laurence A. Turka and Kathryn J. Wood

Additional Perspectives on Transplantation available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Adami J, Gabel H, Lindelof B, Ekstrom K, Rydh B, Glimelius B, Ekbom A, Adami HO, Granath F 2003. Cancer risk following organ transplantation: A nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Br J Cancer 89: 1221–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberú J, Pascoe MD, Campistol JM, Schena FP, Rial Mdel C, Polinsky M, Neylan JF, Korth-Bradley J, Godberg-Alberts R, Maller ES, et al. 2011. Lower malignancy rates in renal allograft recipients converted to sirolimus-based, calcineurin inhibitor-free immunotherapy: 24-Month results from the CONVERT trial. Transplantation 92: 303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato RJ, Jac J, Giessinger S, Saxena S, Willis JP 2009. A phase 2 study with a daily regimen of the oral mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell cancer. Cancer 115: 2438–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo P, Cecco S, Giacomin E, Lazzarini R, Ros B, Marastoni S 2008. mTOR pathway and mTOR inhibitors as agents for cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 8: 647–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batabyal P, Chapman JR, Wong G, Craig JC, Tong A 2012. Clinical practice guidelines on wait-listing for kidney transplantation: Consistent and equitable? Transplantation 94: 703–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnapradist S, Danovitch GM 2007. Evaluation of adult kidney transplant candidates. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 890–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnapradist S, Vincenti F 2009. Transplantation: To convert or not to convert: Lessons from the CONVERT trial. Nat Rev Nephrol 5: 371–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Walker R, Tai SS, Jiang Q, Russ GR 2012. Randomized controlled trial of sirolimus for renal transplant recipients at high risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer. Am J Transplant 12: 1146–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARI Guidelines 2011. Recipient assessment for transplantation. Available from http://www.cari.org.au/trans_recipient_suitability_underdev.php (last accessed February 15, 2012)

- Collett D, Mumford L, Banner NR, Neuberger J, Watson C 2010. Comparison of the incidence of malignancy in recipients of different types of organ: A UK registry audit. Am J Transplant 10: 1889–1896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MG, Teo E, Cole SR, Chan CY, McDonald SP, Russ GR, Young GP, Bampton PA, Coates PT 2012. Screening for colorectal cancer and advanced colorectal neoplasia in kidney transplant recipients: Cross sectional prevalence and diagnostic accuracy study of faecal immunochemical testing for haemoglobin and colonoscopy. BMJ 345: e4657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Fraumeni JF Jr, Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Wolfe RA, Goodrich NP, Bayakly AR, Clarke CA, et al. 2011. Spectrum of cancer risk among U.S. solid organ transplant recipients: The Transplant Cancer Match Study. JAMA 306: 1891–1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Best Practice Guidelines (EBPG) 2000. Section I: Evaluation, selection and preparation of the potential renal transplant candidate. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15: 3–38 [Google Scholar]

- PG Expert Group on Renal Transplantation 2002. European best practice guidelines for renal transplantation. Section IV: Long-term management of the transplant recipient. IV.6.3. Cancer risk after renal transplantation. Solid organ cancers: Prevention and treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 32, 34–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euvrard S, Morelon E, Rostaing L, Goffin E, Brocard A, Tromme I, Broeders N, del Marmol V, Chatelet V, Dompmarin A, et al. 2012. Sirolimus and secondary skin-cancer prevention in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med 367: 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MP, Kelly PJ, Jardine M, Perkovic V, Cass A, Craig JC, Eris J, Webster AC 2010. Long-term cancer risk of immunosuppressive regimens after kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 852–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba M, Graeb C, Jauch KW, Geissler EK 2004. Pro- and anti-cancer effects of immunosuppressive agents used in organ transplantation. Transplantation 77: 1777–1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Villeneuve PJ, Wielgosz A, Schaubel DE, Fenton SSA, Mao Y 2010. The incidence of cancer in a population-based cohort of Canadian heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 10: 637–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasiske BL, Vazquez MA, Harmon WE, Brown RS, Danovitch GM, Gaston RS, Roth D, Scandling JD, Singer GG 2000. Recommendations for the outpatient surveillance of renal transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: S1–S86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasiske BL, Cangro CB, Hariharan S, Hricik DE, Kerman RH, Roth D, Vazquez MA, Weir MR, American Society of Transplantation 2001. The evaluation of renal transplantation candidates: Clinical practice guidelines. Am J Transplant 1: 3–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman HM, McBride MA, Cherikh WS, Spain PC, Marks WH, Roza AM 2002. Transplant tumor registry: Donor related malignancies. Transplantation 74: 358–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiberd BA, Rose C, Gill JS 2009. Cancer mortality in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 9: 1868–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll G, Cockfield S, Blydt-Hansen T, Baran D, Kiberd B, Landsberg D, Rush D, Cole E, Kidney Transplant Working Group of the Canadian Society of Transplantation 2005. Canadian Society of Transplantation: Consensus guidelines on eligibility for kidney transplantation. Can Med Assoc J 173: S1–S25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyllönen L, Salmela K, Pukkala E 2000. Cancer incidence in a kidney-transplanted population. Transpl Int 13: S394–S398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law BK 2005. Rapamycin: An anti-cancer immunosuppressant? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 56: 47–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y, Everly JJ, Gross TG, Tevar AD, First MR, Alloway RR, Woodle ES 2009. De novo cancers arising in organ transplant recipients are associated with adverse outcomes compared with the general population. Transplantation 87: 1347–1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MMOH 2009. Renal replacement therapy—Clinical Practice Guidelines, 3rd ed Malaysian Ministry of Health, Kuala Lumpur [Google Scholar]

- Na R, Grulich AE, Meagher NS, McCaughan GW, Keogh AM, Vajdic CM 2013. Comparison of de novo cancer incidence in Australian liver, heart and lung transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 13: 174–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalesnik MA, Woodle ES, Dimaio JM, Vasudev B, Teperman LW, Covington S, Taranto S, Gockerman JP, Shapiro R, Sharma V, et al. 2011. Donor-transmitted malignancies in organ transplantation: Assessment of clinical risk. Am J Transplant 11: 1140–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opelz G, Döhler B 2004. Lymphomas after solid organ transplantation: A collaborative transplant study report. Am J Transplant 4: 222–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn I 1993. The effect of immunosuppression on pre-existing cancers. Transplantation 55: 742–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay HM, Fryer AA, Hawley CM, Smith AG, Harden PN 2002. Non-melanoma skin cancer risk in the Queensland renal transplant population. Br J Dermatol 147: 950–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RD, Buckner JC, Sarkaria JN 2004. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 4: 621–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeone E, Ascierto PA 2012. Immunomodulating antibodies in the treatment of metastatic melanoma: The experience with anti-CTLA-4, anti-CD137, and anti-PD1. J Immunotoxicol 9: 241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, Vardiman JW 2008. WHO Classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th ed International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France [Google Scholar]

- Vajdic CM, McDonald SP, McCredie MR, van Leeuwen MT, Stewart JH, Law M, Chapman JR, Webster AC, Kaldor JM, Grulich AE 2006. Cancer incidence before and after kidney transplantation. JAMA 296: 2823–2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering J, Roodnat JI, Hemke AC, Hoitsma AJ, Weimar W 2010. Patient survival after the diagnosis of cancer in renal transplant recipients: A nested case-control study. Transplantation 90: 1542–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen MT, Webster AC, McCredie MRE, Stewart JH, McDonald SP, Amin J, Kaldor JM, Chapman JR, Vajdic CM, Grulich AE 2010. Effect of reduced immunosuppression after kidney transplant failure on risk of cancer: Population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ 340: c570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve PJ, Schaubel DE, Fenton SS, Shepherd FA, Jiang Y, Mao Y 2007. Cancer incidence among Canadian kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 7: 941–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang XY, Subjeck JR, Shrikant PA, Kim HL 2011. Temsirolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, enhances anti-tumour effects of heat shock protein cancer vaccines. Br J Cancer 104: 643–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster AC, Wong G 2008. Cancer: ANZDATA registry 2008 report. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, South Australia [Google Scholar]

- Webster AC, Craig JC, Simpson JM, Jones MP, Chapman JR 2007. Identifying high risk groups and quantifying absolute risk of cancer after kidney transplantation: A cohort study of 15,183 recipients. Am J Transplant 7: 2140–2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Howard K, Craig JC, Chapman JR 2008. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 85: 532–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Hayen A, Chapman JR, Webster AC, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Craig JC 2009a. Association of CKD and cancer risk in older people. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1341–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Howard K, Webster A, Chapman JR, Craig JC 2009b. The health and economic impact of cervical cancer screening and human papillomavirus vaccination in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 87: 1078–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Howard K, Webster AC, Chapman JR, Craig JC 2011. Screening for renal cancer in recipients of kidney transplants. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1729–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]