Summary

We encountered 8 cases of high-flow and direct carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) since 1994. Four patients were treated with transarterial fistula occlusions using detachable balloons before 1997. Complete obliteration of CCFs with preservation of internal carotid artery (ICA) were achieved in all 4 cases using each one balloon. Three cases were approached to the fistulas via the percutaneous transfemoral approach, but one aged patient needed a direct carotid puncture because of her tortuous vessels.

Meanwhile, transvenous embolizations with detachable coils (DCs); Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC), interlocking detachable coil (IDC) and fibered platinum coil were attempted in four cases after 1997; in 2 cases after failure of transarterial approach and in 2 as initial form of treatment.

All 4 cases were successfully approached to the cavernous sinuses (CS) through the inferior petorosal sinus (IPS). At first we intended to block dangerous outflow points for the superior ophthalmic vein (SOV), cortical venous reflux (CVR) and contra-lateral CS.And then obliteration of the fistulas were performed with tight packing of GDCs covering the outside of the ICA. At this time, the arteriovenous shunts were disappeared abruptly, so we finished all procedure without occlusion of IPS. We compared the two methods and concluded that the transvenous embolizaton with DCs is an useful alternative of transarterial detachable balloon therapy of high flow CCF, especially when transarterial approach is difficult or proper balloons are not available.

Key words: direct CCF, detachable coil, transvenous embolization, detachable balloon, transarterial embolization

Introduction

The treatment of the direct carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) by using detachable balloon (DB) is generally accepted as the first choice method. However, technical difficulties are not uncommon in this method. And both balloon technique and transarterial embolization (TAE) are not without risk. On the other hand, the development of various types of detachable coil (DC), especially Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC) and Interlocking detachable coil (IDC) have became able to treat direct CCFs by transvenous embolization (TVE). We compared the both methods in the points of effect of fistula occlusion, patency of internal carotid artery (ICA), safety, operation time and cost benefit.

Subject and Methods

A total of 8 direct and high-flow CCFs were treated in our hospital since 1994 (table 1). Four cases; 3 traumatic and 1 idiopathic, were treated by transarterial fistula occlusion with DB. We used Goldvalve Balloon (GVB, Nycomed Co.) which is latex balloon with a self seal valve. Three cases were approached through 9 French (Fr.) guiding catheters via femoral artery. In one old patient (case 2), who had atherosclerotic tortuous vessels, a direct common carotid puncture with 7 Fr. sheath was necessary after an attempt of transfemoral artery approach. Three to 5 balloons of proper size were carefully tested about valve leak by inflating with contrast material. The balloons were introduced into the cavernous sinus (CS) by flow directed with or without proximal flow control. After several test occlusions to estimate an adequate inflation volume, the balloon inflated again with Iopamidole (370 I) and detached by traction method.

Table 1.

Summary of 8 cases with high-flow CCF

| Case No. | Age | Sex | Cause | Approach | Material | Result | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detachable coil therapy | (No. of balloon) | ||||||

| 1 | 51 | M | traumatic | FA | GVB (17→19) | cure | traction force |

| 2 | 74 | F | traumatic | CA | GVB (19) | cure | direct puncture |

| 3 | 41 | F | traumatic | FA | GVB (19x2→1) | cure | residual pouch |

| 4 | 23 | M | idiopathic | FA | GVB (9) | cure | none |

| Detachable coil therapy | (total coils) | ||||||

| 5 | 67 | F | traumatic | IPS | G & I (25) | cure | IPS introduction |

| 6 | 47 | F | traumatic | IPS | G & I (27) | cure | coil migration |

| 7 | 76 | F | idiopathic | IPS | G & I (9) | cure | emergency therapy |

| 8 | 17 | F | traumatic | IPS | G & I | cure | second stage ope. |

| FPC(46) | ICA stenosis | ||||||

|

CCF = carotid cavernous fistula; FA = femoral artery; CA = carotid artery; GVB = Goldvalve Balloon; IPS = inferior petorosal si- nus; G = GDC; I = IDC; FPC = fibered platinum coil. | |||||||

After 1997, 4 cases (3 traumatic and 1 idiopathic) were treated by TVE using GDCs, IDCs and fibered platinum coils (FPC). Two cases (case 5 & 7) were treated by this method after failure of transarterial approach due to tortuous arteries. In all 4 cases microcatheters were introduced into the CS through inferior petorosal sinus (IPS), which were navigated by 5 Fr. guiding catheters via percutaneous femoral vein. In the initial stage we intended to block the outflow points; superior ophthalmic vein (SOV), cortical venos reflux (CVR) and contra-lateral CS to avoid dangerous conversion of the draining pattern. After disappearance or remarkable decrease of the flow, complete obliteration of the fistulas were performed by tight packing covering outside of the ICA at the fistula site with a few coils larger than the fistula size.

Results and Representative Case Reports

Detachable balloon cases (table 1; upper)

Complete obliteration of the fistulas with preservation of ICA were achieved in all 4 DB cases using each one balloon without any complication. Their clinical symptoms were rapidly decreased and no recurrence of symptoms have occurred until the present time. Although the good results of this method are predictable, we experienced some difficulties in those cases.

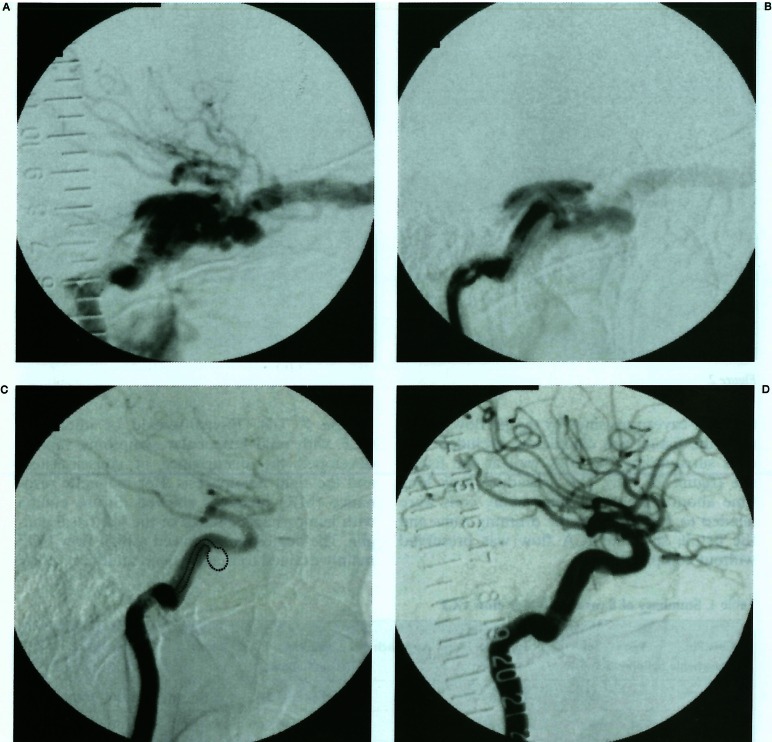

Case 1 (figure 1). In this 51-year-old male with a traumatic CCF (figure 1A), we had to exchange a selected first balloon to another size because of the risk of protrusion of it by strong traction force to detach. Although the balloon was devised to pass through the fistula by proximal flow control (figure 1B), the tip of the microcatheter was forced to bend (figure 1C). It was predicted that the traction force was too strong to detach it without moving into the ICA. The second balloon was slightly slender shaped which fitted to the space of fistula. The tail of the balloon was slightly protruded into the ICA, but there was no thromboembolic complication (figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Case 1. Right internal angiogram (A) shows high-flow CCF drain to SOV. The fistula site is not identified because of enlarged cavernous sinus. Angiogram with proximal flow control shows the fistula site and shape (B). Angiogram under test inflation of a detachable balloon. Note that the bent of microcatheter. The dots line indicates the shape of catheter and balloon (C). Angiogram of post embolization show obliteration of CCF. Note that the tail of detached balloon slighty protrudes within ICA (D).

Case 2. This 74-year-old female was attempted a transarterial approach via percutaneous femoral artery. But a 9 Fr. guiding catheter was too large and stiff for her atherosclerotic arteries. We reluctantly punctured her common carotid artery with a 7 Fr. sheath and performed the balloon therapy. The balloon technique itself was very easy and the hemostasis of the direct puncture was done without hematoma formation after reversal of systemic heparinization with protamine sulfate. But the risk of cervical hematoma after this approach is one of considerable complications.

Case 3. This 41-year-old female had markedly enlarged cavernous sinus due to previous incomplete treatment. She had sufferd from insomnia for long time because of severe pulsative by the drainage to IPS. We attempted to fill the enlarged CS with two balloons. The first balloon had moved toward the IPS by inflation and completely blocked the shunt flow. So the second balloon was not possible to deposit within the residual space. We detached the first balloon only. Although obliteration of CCF and clinical cure were achieved, follow up angiograms have showed a residual pouch of the CS.

Detachable coil group (table 1; lower)

Complete obliteration of CCFs with preservation of ICA were also performed in all 4 DC cases. There were no remarkable complication. In general, we needed long operation time and many coils for extensive embolizations.

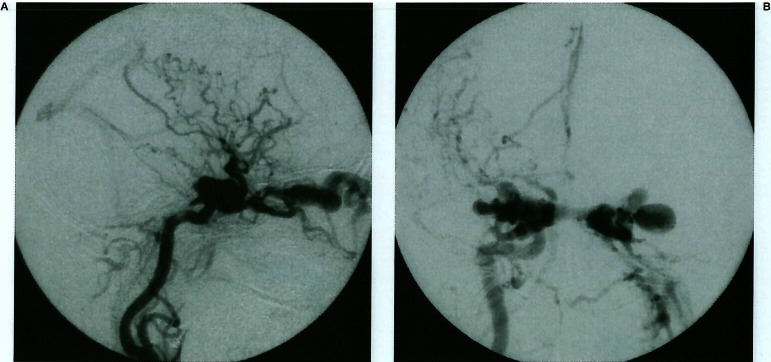

Case 5. (figure 2). This 67-year-old female of traumatic CCF developed bilateral ocular symptoms and headache. The right carotid an-giograms show ipsilateral cortical venous reflux (CVR) and severe bilateral SOV enlargement (figure 2A, 2B). Even a 5 Fr. diagnostic catheter had not been able to introduce to the ICA due to her atherosclerotic vessels, so we abandaned TAE. The microcatheter were introduced into the right SOV and occluded with small size GDCs at first. The selective venogram after SOV occlusion showed only CVR (figure 2C). After tight packing at this site had been added, the carotid angiogram did not show no longer CVR (figure 2D). And then the microcatheter was turned around the ICA toward the orifice of the inter-cavernous sinus. This sinus was enlarged and the flow toward contra-lateral CS was very high. This portion was embolized with relatively large GDCs and IDCs. A part of a GDC was migrated through the inter-cavernous sinus by the jet flow, but finally the fistula was completely occluded with coils surrounding the ICA wall at the fistula site (figure 2E, 2F). The procedure took long time about 6 hours, because many coils were needed to occlude both the draining routs and the fistula site. The ICA flow was preserved without complication.

Figure 2.

Case 5. Right common carotid angiograms show ipsi-lateral extensive cortical reflux (A) and severe bilateral SOV enlargement (B). A selective venography after the right SOV occlusion with GDCs shows only cortical drainage (C). An angiogram after additional embolizations at the point does not show any cortical venous reflux yet (D). Right common carotid angiograms of post embolization show completely obliteration of CCF (E). Note that, a part of GDC migrated to the left cavernous sinus through the intercavenous sinus (F).

Case 7. This 76-year-female of idiopathic CCF, with mild left ocular symptoms, rapidly developed the disturbance of consciousness and the right hemiparesis. Her magnetic resonance (MR) imagings showed diffuse edema with hemorrhagic change of the left basal ganglia. The angiograms showed a high flow CCF mainly drained to the left deep middle cerebral veins. It needed an emergency treatment, but the proper DBs could not be supplied. We decided to attempt TVE. A microcatheter was introduced into the orifice of the middle deep cerebral vein via IPS. We occluded at this point with small GDCs and covered the fistula site with larger GDCs. We used total 9 GDCs and the operation time was about 5 hours. Relatively abrupt closure of the fistula was obtained by deposit of a final GDC. Her symptoms resolved gradually and she discharged by walk.

Case 8. This 17-years-old female involved in a motorcycle accident developed left pulsating exophthalmos and blindness. The cerebral angiogram showed a high-flow left CCF with significant intracranial steal. We had initially considered the sacrifice of ICA because of large fistula suspected and collateral flow from contra lateral ICA was sufficient. But she sufferd from the orthostatic hypotensions. We attempted TVE to preserve the normal ICA flow. We needed the second staged therapy with 47 coils because of extensive embolization for the enlarged CS. Finally obliteration of CCF and the ICA preservation with slightly stenosis were performed.

Discussion

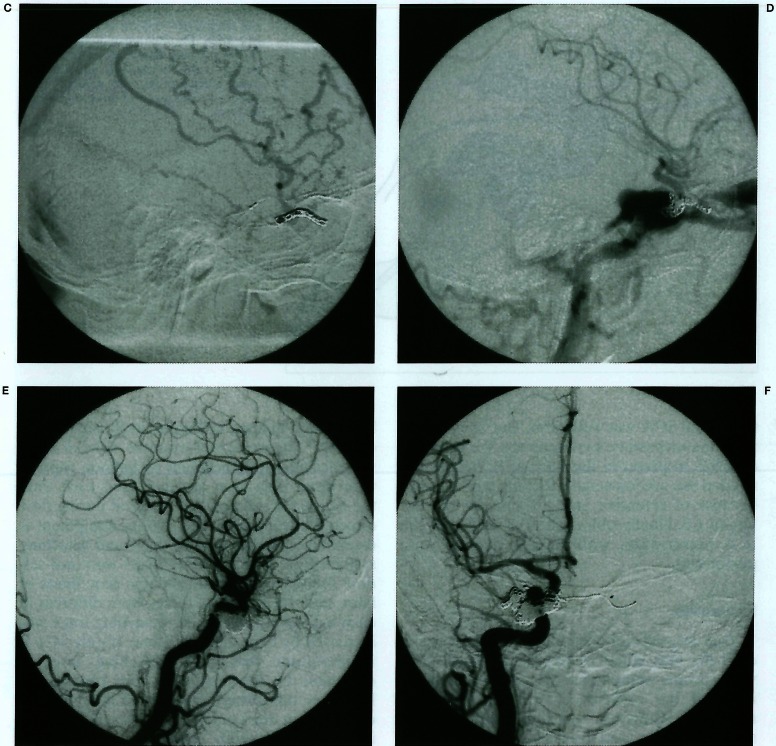

Transarterial embolization with DB is considered the best initial treatment for direct CCF when proper equipments are available and the operator has experience with the technique (figure 3). However, technical difficulties are not uncommon, and transarterial balloon embolization fails in 5% to 10% of cases1,2. One of the reasons is that a 8 to 10 Fr. catheter is necessary for introduction of a proper DB. Occasionally, in aged patients with tortuous vessels, a direct catorid puncture may be necessary 3. We also reluctantly used the direct carotid puncture in case 2. The hemostasis of it was fortunately finished without hematoma formation after reversal of systemic heparinization with protamine sulfate. But potentially fatal complications of cervical hematoma occurred in old reports 3,4. If alternative methods are available, the direct carotid puncture should be avoided. Almost potential complications are depend upon intraarterial maneuvers creating a risk of thromboembolism, and balloon technique itself is not without risk1,2 (figure 3). For example, risks of inadvertent balloon detachment or balloon rupture with distal migration are increased each time the balloon is inflated and deflated during flow directed introduction. The proper equipment is essential, especially reliable valve and detaching system. Note that the valve leaks were not seldom found even within available time limits of latex, and the detaching forces were different in each balloon. In case 1, the detaching force was increased by bent of the catheter (figure 1C). It is important that each detaching force is changable by the conditions. The proper balloons are not always available in short supply, especially in emergency cases. The excellent silicone balloons with calibrated valve system have not been supplied yet in Japan.

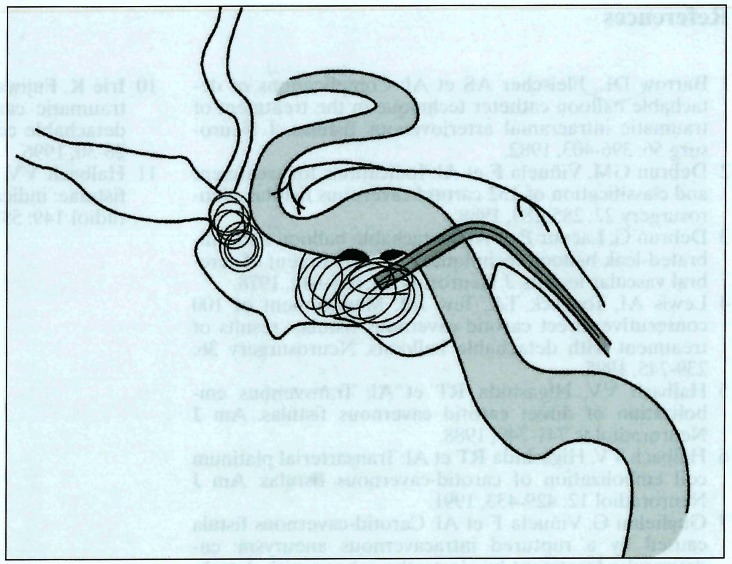

Figure 3.

Illustrated image of transarterial detachable balloon occlusion of direct CCF. The balloon is lodged at the fistula site and fistula occlusion is completed at the moment of inflation. Almost complications are depend upon balloon techniques and intraarterial maneuvers.

Meanwhile, in the 1980s a transvenous approach was developed to treat patients in whom transarterial attempts had failed. Debrun et Al3 were successful in occluding the fistula in only 1 of 12 cases approached transvenously with DB. Halbach et Al4 treated 14 of 165 direct CCF using transvenous occlusion techniques, including the use of coil emboli delivered through microcatheters. They accomplished obliteration of fistulas in 11 of 14 cases. In the 1990s, various equipments of endovascular therapy; microcatheter and steerable microguidewire, retrievable coils such as IDC and GDC, have significantly developed. Halbach et Al5 reported transarterial platinum coil embolization of CCFs in 1991. Guglielmi et Al6 reported the first case of trans venous GDC emobolization of CCF by a ruptured intracavernous aneurysm in 1992. And then they reported transarterial treatment with GDC for high-flow arteriovenous fistulas including one CCF case in 19957. Siniluoto8 reported 4 cases of TAE of CCFs, small to middle sized fistulas, with GDCs. They had no experience in treating large, high-flow fistulas with GDCs. Irie 9 reported a recurrent CCF after DB therapy were treated by IDCs via SOV.

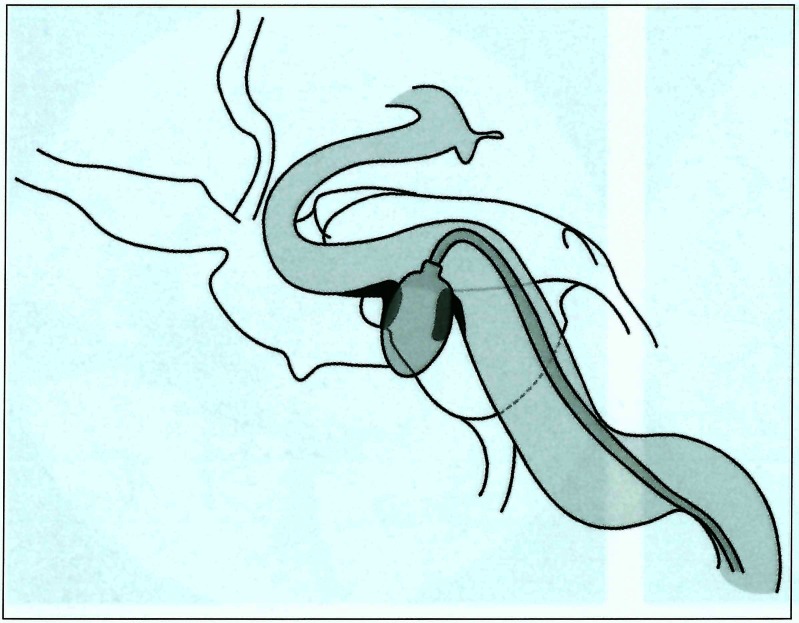

Three of our cases were high-flow CCFs with dangerous CVR, especially case 7 needed urgent treatment because of hemorrhagic venous reflux 10. The pitfall of the transvenous approach is the conversion of drainage route before complete occlusion of the fistula. Occlusion of the venous outflow may redirect the flow in the remaining pathways, it is dangerous aggravating ocular symptoms (SOV) and intracerebral hemorrhage (CVR). We intended to block the outflow points at first; SOV, CVR and contra-lateral CS to avoid dangerous conversion of the draining pattern. After obliteration or remarkable decrease of shunt flow, the occlusion of the fistulas were performed by tight packing with larger coils than the fistula. The closure of fistulas are abruptly occurred by deposited of an additional large and long type coil at the fistula site. It is supposed that the gate like wall of the fistula is closed from outside by proper coils (figure 4). The preserved ICA walls are smooth in our cases expect case 8. Choosing the proper coil size is essential. GDCs are very pliable and adapt to the shape of the cavernous sinus without producing a significant mass effect. But TVE need long operation time and many coils for safety procedure. If the fistula is relatively small, the occlusion of it is accomplished with less numbers of coils. We have no experience of transarterial coil embolization of CCF. CCFs due to aneurysmal rapture of cavernous portion or small fistula of traumatic CCFs may be good indications of transarterial approach. TVE have significant benefit of the lowest possibility of thromboembolic complications due to intraarterial maneuvers. Although the cases of extensively enlarged CS suspected tear of ICA wall like case 3 and 8 are difficult cases by both DB and DC, TVE with careful positioning of DCs is useful method before sacrifice of ICA.

Figure 4.

Illustrated image of transvenous detachable coil embolization of direct CCF. This procedures are performed within CS only. The risk of thromboemobolic complications is very low. The dangerous drainages of SOV and CVR should be blocked at the initial stage for safety. The fistula site is covered from the outside like a gate closed by large and long coils. This fashion of occlusion is feasible to preserve the patency of ICA.

Conclusions

In this series, all the patients of coil embolizations via the transvenous route were treated with excellent results. TVE with DCs is an alternative method for direct, high-flow CCF, especially when transarterial approach has failed. The long operation time and the cost of many coils are problems.

References

- 1.Barrow DL, Fleischer AS, et al. Complications of detachable~ŧrálloon catheter technique in the treatment of traumatic intracranial arteriovenous fistulas. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:396–403. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.56.3.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debrun GM, Viñuela F, et al. Indications for treatment and classification of 132 carotid cavernous fistulas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:285–289. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debrun G, Lacour P, et al. Detachable balloon and calibrated-leak balloon techniques in the treatment of cerebral vascular lesions. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:635–649. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.49.5.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis Al, Tomsick TA, Tew JM. Management of 100 consecutive direct carotid-cavernous fistulas: results of treatment with detachable balloons. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:239–245. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199502000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, et al. Transvenous embolization of direct carotid cavernous fistulas. Am J Neuroradiol. 1988;9:741–749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, et al. Transarterial platinum coil embolization of carotid-cavernous fistulas. Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:429–433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guglielmi G, Viñuela F, et al. Carotid-cavernous fistula caused by a ruptured intracavernous aneurysm: endovascular treatment by electrothrombosis with detachable coils. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:591–597. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199209000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guglielmi G, Viñuela F, et al. High-flow small-hole arteriovenous fistulas: treatment with electrodetachable coils. Am J Radiol. 1995;16:325–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siniluoto T, Seppanen S, et al. Transarterial embolization of a direct carotid cavernous fistula with Guglielmi detachable coils. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:519–523. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irie K, Fujiwara H, et al. Transvenous embolization of traumatic carotid cavernous fistula with mechanical detachable coils. Minimum Invasive Neurosurgery. 1996;39:28–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halbach W, Hieshima GB, et al. Carotid cavernous fistulae: indications for urgent treatment. Am J Neuroradiol. 1987;149:587–593. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]