Abstract

Diabetes and insulin resistance can greatly increase microvascular complications of diabetes including diabetic nephropathy (DN). Hyperglycemic control in diabetes is key to preventing the development and progression of DN. However, it is clinically very difficult to achieve normal glucose control in individual diabetic patients. Many factors are known to contribute to the development of DN. These include diet, age, lifestyle, or obesity. Further, inflammatory- or oxidative-stress-induced basis for DN has been gaining interest. Although anti-inflammatory or antioxidant drugs can show benefits in rodent models of DN, negative evidence from large clinical studies indicates that more effective anti-inflammatory and antioxidant drugs need to be studied to clear this question. In addition, our recent report showed that potential endogenous protective factors could decrease inflammation and oxidative stress, showing great promise for the treatment of DN.

1. Introduction

Diabetes nephropathy (DN) is the major determinant of morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes. Chronic hyperglycemia is a major initiator of DN. Several studies indicate a causal link between the degree of glycemic control in patients with diabetes and the development and progression of complications. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) demonstrated that intensive glycemic control in patients with both type 1 and 2 diabetes successfully delayed the onset and retarded macrovascular and microvascular complications including DN [1, 2]. In addition, the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) indicated that intensive glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes decreased the risk of DN and diabetic retinopathy [3, 4]. Thus, strict glycemic control could prevent the initiation and development of DN. Despite such lines of evidences conventional therapies used for glycemic control in patients with diabetes do not always prevent the ultimate progression of DN. Therefore, the use of therapies that specifically target DN could be useful and really needed in addition to a strict glycemic control. It is reported that the induction of inflammation and oxidative stress by the metabolism of hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia may play a significant role in developing vascular complications including DN in patients or animals [5–9]. The increases of inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS) have also been shown in DN. Our recent studies clearly showed that insulin or glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) prevented the development of DN, neutralizing inflammation and oxidative stress [10]. This paper will outline these theories and the potential therapeutic interventions that could prevent DN in the presence of hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia.

2. Induction of Inflammation by Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is characterized by a progressive cell-mediated destruction of pancreatic islet cells, leading to loss of insulin production. The development of DN is associated with significant inflammatory cells infiltration with increasing in plasma levels of CRP and inflammatory cytokines such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and interleukin (IL)-1β [11]. These data strongly support that immune cells participate in the development of DN.

Increases in inflammation are detected in healthy individuals who later go on to develop type 2 diabetes; several reports indicate that, in type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, CD8+ T cells are activated in obese adipose tissue [12]. Further, it is reported that healthy, middle-aged women who showed high levels of inflammatory markers IL-6 and CRP had increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes over a 4-year period [13].

3. Induction of Oxidants by Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes

There are several studies showing that oxidant production is increased in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Oxidative stress results when the rate of oxidant production exceeds the rate of oxidant scavengers and also by alteration of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)/NADP ratios results [14]. The abnormal metabolism of glucose or free fatty acid (FFA) via mitochondria pathways and the activation of NADPH oxidases via protein kinase C (PKC) have been recognized as contribution of oxidant production [15]. There is substantial evidence supporting that ROS is increased in kidney and retina either exposed to hyperglycemia or in diabetic animals [16–18]. Further, plasma levels of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, isoprostanes, and lipid peroxides are elevated both in diabetic animals and patients [19–21]. Thus, increased ROS production in diabetes can originate from the abnormal metabolism of glucose and FFA through multiple pathways. This supports an explanation for the findings of increased oxidative stress in insulin-resistant nondiabetic patients.

4. Association between Inflammatory Processes and Diabetic Nephropathy

Although metabolic and hemodynamic factors are the main causes of DN, recent studies have suggested that DN is an inflammatory process, and immune cells could be involved in the development of DN [22, 23]. Hyperglycemia may induce macrophage production of IL-12, which can stimulate CD4 cell production of IFN-γ. FFA, hyperglycemia, and obesity may activate nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) through PKC and ROS to rapidly stimulate the expression of cytokines [24, 25]. Following activation, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus, stimulating rapidly the subsequent transcription of genes such as endothelin-1 (ET-1), VCAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), IL-6, and TNF-α that promote the development of DN. It is well known that elevated levels of advanced glycation end products (AGE) can be found in kidney. AGE interacts with receptor for AGE (RAGE), and AGE/RAGE interactions have been reported in the development of DN [26]. Exposure of activated lymphocytes to AGE enhances the expression of IFN-γ which may accelerate immune responses that contribute to developing DN [27, 28]. Additionally, in a clinical study of type 2 diabetes patients, positive correlations were recognized between plasma IFN-γ, proteinuria, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [29]. Further, plasma IL-2R levels found in type 2 DM patients with overt DN were higher than in those without overt nephropathy, and apparent positive correlation was recognized between plasma IL-2R and proteinuria [29].

5. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Nephropathy

Numerous studies clearly indicate that both diabetic state and insulin resistance play a central role in producing oxidative stress; free glucose activates aldose reductase activity and the polyol pathway, which decreases NADPH/NADP+ ratios [30]. Elevated intracellular glucose activates PKC through de novo synthesis of diacylglycerol (DAG) [31]. Activation of PKC in the glomeruli has been associated with processes increasing mesangial expansion, thickening basement membrane, endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle cell contraction, and activation of cytokines and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [32]. PKC induces oxidative stress by activating mitochondrial NADPH oxidase [14]. Vascular NADPH oxidase consists of multiple subunits including phox47, phox67, and Nox isoforms [14]. ROS generated from Nox isoforms might induce endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and apoptosis [33]. Excess FFA, mainly derived from insulin-resistant state, also can increase oxidant production by β oxidative phosphorylation via mitochondrial metabolism [34, 35]. Studies using rodents indicate that increases in oxidative stress could be responsible for developing DN; inhibition of the polyol pathway with aldose reductase inhibitors could reduce the effects of hyperglycemia on DN [36]. Further, administration of vitamin C or E has been shown to be effective in ameliorating rodent model of DN [37, 38]. Another study has also shown that high doses of vitamin E normalized parameters of oxidative stress and inhibited vascular abnormalities caused by DAG-PKC activation in the kidney [39].

6. Antioxidants as Therapeutics for Diabetic Nephropathy

6.1. Vitamin C and E

Administration of vitamin C, alone or in combination with vitamin E, has suggested decreases in microalbuminuria. Patients with type 1 diabetes for less than 10-year duration who received high doses (1,800 IU/day) of vitamin E showed restoration of renal function [37]. However, these studies were of very short duration and small sample size. In contrast, in the 4-year-long Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study of more than 3,600 diabetic patients, some of whom already displayed microalbuminuria, vitamin E supplementation (400 IU/day) did not lower the risk for cardiovascular outcome significantly [40]. Thus, based on these lines of evidence, effectiveness using vitamin C or E toward DN remains to be unknown.

6.2. Nrf2

The transcription factor NFE2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a master regulator of cellular detoxification responses and redox status. Upregulation of Nrf2 and its downstream antioxidant genes in response to hyperglycemia was found both in the kidney and renal cells [41–43]. In clinical trials reported recently, bardoxolone methyl, which interacts with cysteine residues on Keap1, allowing Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus leading to anti-inflammatory effects, appears to have beneficial effects in DN compared with placebo after 52 weeks of treatments [44, 45]. However, this phase 3 trial was halted in October 2012 because of a higher mortality in treated group.

7. Anti-Inflammatory Drugs as Therapeutics for Diabetic Nephropathy

Inflammation plays a significant role in developing DN in several models of DN; DN reflects the results of inflammatory, metabolic, and hemodynamic factors. Inflammation could cause glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, and fibrosis. Therefore, administration of anti-inflammatory strategies could be a potential treatment of DN.

7.1. MCP-1 and CCL2 Inhibitor

Monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) is significantly increased in DN, and macrophage infiltration into glomeruli is associated with glomerular injury. Further, urinary excretion of MCP-1 is correlated with diabetic glomerular injury [5]. MCP-1 null mice are protected against DN [46] and blockade of the MCP-1 receptor, C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR-2) using propagermanium-ameliorated diabetic glomerulosclerosis [47]. However, clinical inhibitors of chemokine C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2) inhibitor may show partial effects to DN [48], because even complete deletion of CCL2 only reduced albuminuria in rodent DN model [49].

7.2. Pentoxifylline

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is mainly produced by monocytes and macrophages. However, TNF-α expression is increased in the kidney in DN. It has been reported that patients with type 2 diabetes have 3-4 times greater serum levels of TNF-α, compares to healthy control [50]. Further, the level of TNF-α was higher in DN with microalbuminuria compared within those with no albuminuria [51]. Pentoxifylline inhibits the expression of mRNA levels of TNF-α [52]. Combination with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), AT1 receptor blockers (ARB), and pentoxifylline could decrease albuminuria in DN [53, 54].

7.3. Adipokines

Adiponectin derived from adipose tissue has anti-inflammatory properties. Adiponectin suppresses inflammatory markers including TNF-α, receptor activation for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF) or fibroblast growth factor (FGF) [55]. Diabetic rat overexpression of adiponectin might preserve nephrin, decrease expression levels of TGF-β, and reduce albuminuria [56]. However, it is still unclear whether adiponectin will provide significant effects toward human DN.

7.4. Inhibition of NF-κB

Recent studies suggest the critical role of NF-κB in the development of insulin resistance, including an animal model [57] and a human study [58]. Salsalate treatment improved insulin-sensitivity-increased adiponectin, resulting in reduction of inflammatory markers [58]. For DN, several lines of evidence support the pivotal role of NF-κB in the development of DN including mesangial cells [59], glomerular endothelial cells [10], and podocytes [60]. Inhibition of NF-κB in kidney using peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) [61], ARB [62], or pentosan polysulfate (PPS) [63] may ameliorate DN in animal model. However, clear demonstration of the efficacy of inhibition of NF-κB in delaying progression of DN has not been reported.

7.5. HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors

3-Hydroxy-3-methyllutaryl CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors, or statins, are potent inhibitors of cholesterol biosynthesis that are useful for treatment of patients with dislipidemia. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors might prove to be key inhibitors of low-grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction by reducing inflammatory cell signaling [64]. In clinical studies, the beneficial effect of statins on renal function in DN is still controversial; in a subanalysis of the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study, treatment with 10 mg and 80 mg atorvastatin was found to increase eGFR [65], while in the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease Intervention Trial (PREVEND-IT), treatment with 40 mg pravastatin did not result in increases in eGFR [66].

7.6. Rapamycin

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a serine/threonine kinase that mediates cell proliferation, survival, size, and mass [67]. Rapamycin reduces mTOR activity that is increased by hyperglycemia and mediates the renal changes in DN, including mesangial expansion or glomerular basement thickness [68]. Rapamycin significantly reduces the influx of inflammatory cells including monocytes and macrophages associated with progression of DN [69, 70]. Rapamycin also reduces the release of proinflammatory cytokines or chemokines including MCP-1, regulated and normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), IL-8, and fractalkine [69, 70]. Thus, administration of rapamycin as an anti-inflammatory drug could be a new therapeutic regimen for DN.

7.7. Aspirin and COX-2 Inhibitors

Aspirin and cyclooxygense-2 (COX-2) inhibitors are major anti-inflammatory agents. Recent study has suggested that administration of aspirin could decrease albuminuria in patients with DN [71]. Further, combination with aspirin and AT1 receptor blockers (ARB) resulted in a further decrease in the progression of DN and inflammatory markers compared to aspirin treatment alone [72]. It is reported that COX-2 inhibitors could increase renal hemodynamics and decrease profibrotic cytokines [73]. Despite this report, treatment with 200 mg/day COX-2 inhibitor for six weeks could not decrease DN [74]. Thus, administration of COX-2 inhibitors for treatment of DN remains controversial.

7.8. Inhibition of PKC Activation

As described previously, the activation of PKC is induced by hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. It has been reported that PKC activation altered cell signaling molecules including inflammatory cytokines such as NF-κB, IL-6, TNF-α, and plasminogen activator-1 (PAI-1) in many vascular cells including endothelial cells and mesangial cells [10, 75, 76]. Ruboxistaurin (RBX), a PKCβ isoform selective inhibitor, has been shown to prevent DN in rodent DN models through inhibition of mediators of extracellular matrix accumulation, TGF-β and amelioration of insulin signaling [77, 78]. Further, diabetic PKCβ null mice showed decreases of albuminuria and mesangial expansion [79]. In a phase II clinical trial it was shown that RBX treatment with diabetes significantly decreased albuminuria and maintained a stable estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [80]. Recently, we showed that hyperglycemia can activate PKCβ isoforms, which enhance angiotensin II (Ang II) toxic effect in glomerular endothelial cells and decrease glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor, leading to resistance of GLP-1's treatment on DN [10].

Further, our recent findings suggest that hyperglycemia activates PKCδ and p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAPK) to increase Src homology-2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) and causes VEGF resistance and independent NF-κB activation to induce podocyte apoptosis in DN [60].

7.9. Insulin and NO

It is reported that exogenous insulin could inhibit the activation of TNF-α in animal models [81]. Also, other reports suggested that insulin could inhibit MCP-1 expression and activation of NF-κB in endothelial cells [82]. Furthermore, recent studies in patients with type 2 diabetes showed that insulin treatment decreased expressions of inflammatory cytokines, such as MCP-1, ICAM-1, soluble VCAM-1 (sVCAM-1), TNF-α, and IL-6 [83, 84].

Insulin can increase endothelial nitric oxide (NO) production by rapid posttranslational mechanisms, which are mediated by the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, resulting in vasodilatation, antithrombotic effect, and anti-inflammation [78, 85, 86]. Insulin stimulates not only NO production but also the expression of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells [87]. Supporting this, a recent study indicates that vascular endothelial cell specific insulin receptor knockout mice decreased eNOS expression in aorta [88]. Thus, impairment of insulin action in vascular tissue could contribute to DN. However, the efficacy of exogenous NO donor remains unclear.

7.10. PPAR-γ Agonist

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) have been shown to have pivotal role in regulating insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism, adipogenesis, and cell growth [89–92]. Recent studies indicated that PPAR-γ agonist decreased expressions of inflammatory markers such as PAI-1, ICAM-1, and NF-κB in the kidney in DN and ameliorated renal function [93].

7.11. GLP-1 and DPP-IV Inhibitors

The incretin hormone, GLP-1, is released from gut in response to meal which can augment glucose-dependent insulin release [94]. Analysis of GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) revealed its expression in endothelial cells and kidney [10, 95, 96]. In endothelial cells, GLP-1 might inhibit the expression of TNF-α and VCAM-1 [10]. Our recent study indicates that GLP-1 is partly mediating its protective actions via its own receptor by the activation of protein kinase A (PKA) [10]. GLP-1 can induce protective actions on the glomerular endothelial cells by diminishing the signaling pathway of Ang II at phospho-c-Raf(Ser338)/phospho-Erk1/2 via phospho-c-Raf(Ser259) activated by cAMP/PKA pathway. Further, administration of GLP-1 in DN decreased inflammatory markers including PAI-1, CD68, IL-6, TNF-α, NF-κB, and CXCL2 in the kidney [10]. Thus, our recent studies indicated the mechanisms by which GLP-1 could induce protective actions on the glomerular endothelial cells by inhibiting the signaling pathway of Ang II and its proinflammatory effect, and indicated a dual signaling mechanism by which PKCβ activation could increase Ang II action and inhibit GLP-1's protective effects by reducing the expression of GLP-1 receptors in the glomerular endothelial cells.

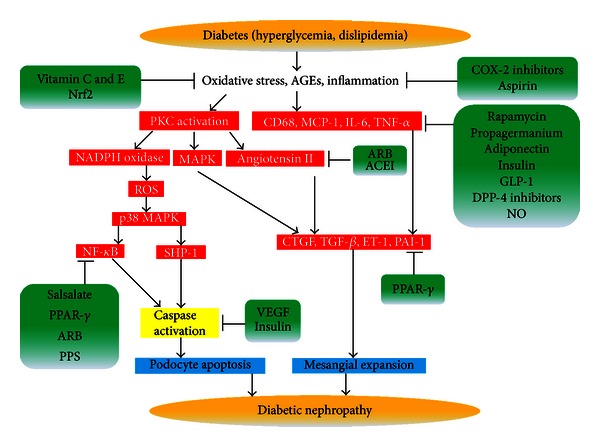

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors provide vascular protection by increasing GLP-1's bioavailability and its action. It has been reported that DPP-4 inhibitors reduced MCP-1. Further, DPP-4 inhibitors have vasotropic actions and the possibility of an actual reduction in DN [97]. Also, recent large phase III data shows that linagliptin, DPP-4 inhibitor, significantly reduces albuminuria by 30% in DN [98]. However, the role of DPP-4 inhibitors in the regulation of inflammatory cytokines and vasotropic actions remains largely unexplored (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram on the progression of diabetic nephropathy and its inhibition. AGEs: advanced glycation end products; PKC: protein kinase C; COX-2: cyclooxygense-2; Nrf2: NFE2-related factor 2; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; MCP-1: monocyte-chemoattractant protein-1; IL-6: interleukin-6; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; GLP-1: glucagon like peptide-1; DPP-4: dipeptidyl peptidase-4; NO: nitric oxide; ARB: AT1 receptor blockers; ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; SHP-1: Src homology-2 domain-containing phosphatase-1; PPAR-γ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; PPS: pentosan polysulfate.

8. Summary

Although good glycemic control may be the best prevention of DN, it develops in spite of treatment of diabetes. Inhibitors of oxidative stress and inflammation should provide useful targets for therapy; however, many clinical trials using agents directly against these targets remain controversial. Novel therapeutic agents for patients with DN beyond glucose lowering should be highly attractive. Thus, we proposed the possible new treatments that could combine PKCβ inhibitors with higher doses of GLP-1 agonists. GLP-1 is one potential pharmaceutical that could decrease the toxic effects, oxidative stress and inflammation of Ang II to lower the risk of DN.

Conflict of Interests

No potential conflict of interests relevant to this paper was reported.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by Grants to Akira Mima from Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (24890148) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research, Takeda Science Foundation, Japanese Association of Dialysis Physicians (JADP Grant 2012-03), and the Kidney Foundation, Japan (JKF13-1).

References

- 1.Nathan DM. Isolated pancreas transplantation for type 1 diabetes: a doctor's dilemma. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(21):2861–2863. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.21.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund J-YC, et al. Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes I, Complications Study Research G: intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(25):2643–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shamoon H, Duffy H, Fleischer N, et al. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(14):977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner R. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) The Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banba N, Nakamura T, Matsumura M, Kuroda H, Hattori Y, Kasai K. Possible relationship of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 with diabetic nephropathy. Kidney International. 2000;58(2):684–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sassy-Prigent C, Heudes D, Mandet C, et al. Early glomerular macrophage recruitment in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2000;49(3):466–475. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada S, Shikata K, Matsuda M, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1-deficient mice are resistant against renal injury after induction of diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52(10):2586–2593. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow F, Ozols E, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Atkins RC, Tesch GH. Macrophages in mouse type 2 diabetic nephropathy: correlation with diabetic state and progressive renal injury. Kidney International. 2004;65(1):116–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gæde P, Poulsen HE, Parving H-H, Pedersen O. Double-blind, randomised study of the effect of combined treatment with vitamin C and E on albuminuria in Type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetic Medicine. 2001;18(9):756–760. doi: 10.1046/j.0742-3071.2001.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mima A, Hiraoka-Yamomoto J, Li Q, et al. Protective effects of GLP-1 on glomerular endothelium and its inhibition by PKCbeta activation in diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:2967–2979. doi: 10.2337/db11-1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devaraj S, Cheung AT, Jialal I, et al. Evidence of increased inflammation and microcirculatory abnormalities in patients with type 1 diabetes and their role in microvascular complications. Diabetes. 2007;56(11):2790–2796. doi: 10.2337/db07-0784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, et al. CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nature Medicine. 2009;15(8):914–920. doi: 10.1038/nm.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickup JC, Mattock MB, Chusney GD, Burt D. NIDDM as a disease of the innate immune system: association of acute-phase reactants and interleukin-6 with metabolic syndrome X. Diabetologia. 1997;40(11):1286–1292. doi: 10.1007/s001250050822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedard K, Krause K-H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87(1):245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King GL, Loeken MR. Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress in diabetic complications. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2004;122(4):333–338. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitada M, Koya D, Sugimoto T, et al. Translocation of glomerular p47phox and p67phox by protein kinase C-β activation is required for oxidative stress in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2003;52(10):2603–2614. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newsholme P, Haber EP, Hirabara SM, et al. Diabetes associated cell stress and dysfunction: role of mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial ROS production and activity. Journal of Physiology. 2007;583(1):9–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.135871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zang Z, Apse K, Pang J, Stanton RC. High glucose inhibits glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase via cAMP in aortic endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(51):40042–40047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mezzetti A, Cipollone F, Cuccurullo F. Oxidative stress and cardiovascular complications in diabetes: isoprostanes as new markers on an old paradigm. Cardiovascular Research. 2000;47(3):475–488. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakimoto M, Inoguchi T, Sonta T, et al. Accumulation of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine and mitochondrial DNA deletion in kidney of diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2002;51(5):1588–1595. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leinonen J, Lehtimäki T, Toyokuni S, et al. New biomarker evidence of oxidative DNA damage in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The FEBS Letters. 1997;417(1):150–152. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivero A, Mora C, Muros M, García J, Herrera H, Navarro-González JF. Pathogenic perspectives for the role of inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Clinical Science. 2009;116(6):479–492. doi: 10.1042/CS20080394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navarro-González JF, Mora-Fernández C, De Fuentes MM, García-Pérez J. Inflammatory molecules and pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2011;7(6):327–340. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha H, Mi RY, Yoon JC, Kitamura M, Hi BL. Role of high glucose-induced nuclear factor-κB activation in monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression by mesangial cells. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2002;13(4):894–902. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V134894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J-S, Lee H-S, Jin J-S, et al. Attenuation of mouse mesangial cell contractility by high glucose and mannitol: involvement of protein kinase C and focal adhesion kinase. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2004;11(2):142–151. doi: 10.1007/BF02256557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myint K-M, Yamamoto Y, Doi T, et al. RAGE control of diabetic nephropathy in a mouse model: effects of RAGE gene disruption and administration of low-molecular weight heparin. Diabetes. 2006;55(9):2510–2522. doi: 10.2337/db06-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galkina E, Ley K. Leukocyte recruitment and vascular injury in diabetic nephropathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17(2):368–377. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imani F, Horii Y, Suthanthiran M, et al. Advanced glycosylation endproduct-specific receptors on human and rat T-lymphocytes mediate synthesis of interferon γ: role in tissue remodeling. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1993;178(6):2165–2172. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu C-C, Chen J-S, Lu K-C, et al. Aberrant cytokines/chemokines production correlate with proteinuria in patients with overt diabetic nephropathy. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2010;411(9-10):700–704. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tesfamariam B. Free radicals in diabetic endothelial cell dysfunction. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1994;16(3):383–391. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishii H, Jirousek MR, Koya D, et al. Amelioration of vascular dysfunctions in diabetic rats by an oral PKC β inhibitor. Science. 1996;272(5262):728–731. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koya D, King GL. Protein kinase C activation and the development of diabetic complications. Diabetes. 1998;47(6):859–866. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cave AC, Brewer AC, Narayanapanicker A, et al. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular health and disease. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2006;8(5-6):691–728. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giugliano D, Ceriello A, Paolisso G. Oxidative stress and diabetic vascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(3):257–267. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duckworth WC. Hyperglycemia and cardiovascular disease. Current Atherosclerosis Reports. 2001;3(5):383–391. doi: 10.1007/s11883-001-0076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunlop M. Aldose reductase and the role of the polyol pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney International, Supplement. 2000;58(77):S3–S12. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bursell S-E, Clermont AC, Aiello LP, et al. High-dose vitamin E supplementation normalizes retinal blood flow and creatinine clearance in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(8):1245–1251. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.8.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bursell S-E, King GL. Can protein kinase C inhibition and vitamin E prevent the development of diabetic vascular complications? Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 1999;45(2-3):169–182. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koya D, Lee I-K, Ishii H, Kanoh H, King GL. Prevention of glomerular dysfunction in diabetic rats by treatment with d-alpha-tocopherol. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1997;8(3):426–435. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V83426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yusuf S, Dagenais G, Pogue J, Bosch J, Sleight P. Vitamin E supplementation and cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(3):154–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng H, Whitman SA, Wu W, et al. Therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activators in streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2011;60(11):3055–3066. doi: 10.2337/db11-0807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Zhang L, Wang F, et al. Attenuation of glomerular injury in diabetic mice with tert-butylhydroquinone through nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2-dependent antioxidant gene activation. American Journal of Nephrology. 2011;33(4):289–297. doi: 10.1159/000324694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palsamy P, Subramanian S. Resveratrol protects diabetic kidney by attenuating hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and renal inflammatory cytokines via Nrf2-Keap1 signaling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2011;1812(7):719–731. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pergola PE, Raskin P, Toto RD, et al. Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(4):327–336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pergola PE, Krauth M, Huff JW, et al. Effect of bardoxolone methyl on kidney function in patients with T2D and stage 3b-4 CKD. American Journal of Nephrology. 2011;33(5):469–476. doi: 10.1159/000327599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarabra E, Giunti S, Barutta F, et al. Effect of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CC chemokine receptor 2 system on nephrin expression in streptozotocin-treated mice and human cultured podocytes. Diabetes. 2009;58(9):2109–2118. doi: 10.2337/db08-0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanamori H, Matsubara T, Mima A, et al. Inhibition of MCP-1/CCR2 pathway ameliorates the development of diabetic nephropathy. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;360(4):772–777. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chow FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Ozols E, Atkins RC, Rollin BJ, Tesch GH. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 promotes the development of diabetic renal injury in streptozotocin-treated mice. Kidney International. 2006;69(1):73–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chow FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Ma FY, Ozols E, Rollins BJ, Tesch GH. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-induced tissue inflammation is critical for the development of renal injury but not type 2 diabetes in obese db/db mice. Diabetologia. 2007;50(2):471–480. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0497-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Navarro JF, Mora C, Macía M, García J. Inflammatory parameters are independently associated with urinary albumin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2003;42(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moriwaki Y, Yamamoto T, Shibutani Y, et al. Elevated levels of interleukin-18 and tumor necrosis factor-α in serum of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: relationship with diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. 2003;52(5):605–608. doi: 10.1053/meta.2003.50096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han J, Thompson P, Beutler B. Dexamethasone and pentoxifylline inhibit endotoxin-induced cachectin/tumor necrosis factor synthesis at separate points in the signaling pathway. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1990;172(1):391–394. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harmankaya O, Seber S, Yilmaz M. Combination of pentoxifylline with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors produces an additional reduction in microalbuminuria in hypertensive type 2 diabetic patients. Renal Failure. 2003;25(3):465–470. doi: 10.1081/jdi-120021159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Navarro JF, Mora C, Muros M, García J. Additive antiproteinuric effect of pentoxifylline in patients with type 2 diabetes under angiotensin II receptor blockade: a short-term, randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2005;16(7):2119–2126. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Lam KSL, Xu JY, et al. Adiponectin inhibits cell proliferation by interacting with several growth factors in an oligomerization-dependent manner. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(18):18341–18347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakamaki S, Satoh H, Kudoh A, Hayashi Y, Hirai H, Watanabe T. Adiponectin reduces proteinuria in streptozotocin-induced diabetic wistar rats. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2011;236(5):614–620. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2011.010218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yuan M, Konstantopoulos N, Lee J, et al. Reversal of obesity- and diet-induced insulin resistance with salicylates or targeted disruption of Ikkβ . Science. 2001;293(5535):1673–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.1061620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fleischman A, Shoelson SE, Bernier R, Goldfine AB. Salsalate improves glycemia and inflammatory parameters in obese young adults. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):289–294. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Menini S, Amadio L, Oddi G, et al. Deletion of p66Shc longevity gene protects against experimental diabetic glomerulopathy by preventing diabetes-induced oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2006;55(6):1642–1650. doi: 10.2337/db05-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mima A, Kitada M, Geraldes P, et al. Glomerular VEGF resistance induced by PKCdelta/SHP-1 activation and contribution to diabetic nephropathy. The FASEB Journal. 2012;26:2963–2974. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-202994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Makino H, Miyamoto Y, Sawai K, et al. Altered gene expression related to glomerulogenesis and podocyte structure in early diabetic nephropathy of db/db mice and its restoration by pioglitazone. Diabetes. 2006;55(10):2747–2756. doi: 10.2337/db05-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamal F, Yanakieva-Georgieva N, Piao H, Morioka T, Oite T. Local delivery of angiotensin II receptor blockers into the kidney passively attenuates inflammatory reactions during the early phases of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy through inhibition of calpain activity. Nephron. 2010;115(3):e69–e79. doi: 10.1159/000313832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu J, Guan T-J, Zheng S, et al. Inhibition of inflammation by pentosan polysulfate impedes the development and progression of severe diabetic nephropathy in aging C57B6 mice. Laboratory Investigation. 2011;91(10):1459–1471. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340(2):115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shepherd J, Kastelein JJP, Bittner V, et al. Investigators TNT: intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease: the TNT (Treating to New Targets) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51(15):1448–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brouwers FP, Asselbergs FW, Hillege HL, et al. Long-term effects of fosinopril and pravastatin on cardiovascular events in subjects with microalbuminuria: ten years of follow-up of Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-stage Disease Intervention Trial (PREVEND IT) American Heart Journal. 2011;161(6):1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lieberthal W, Levine JS. The role of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in renal disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009;20(12):2493–2502. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagai K, Matsubara T, Mima A, et al. Gas6 induces Akt/mTOR-mediated mesangial hypertrophy in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney International. 2005;68(2):552–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sakaguchi M, Isono M, Isshiki K, Sugimoto T, Koya D, Kashiwagi A. Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin attenuates renal hypertrophy in the early diabetic mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;340(1):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang Y, Wang J, Qin L, et al. Rapamycin prevents early steps of the development of diabetic nephropathy in rats. American Journal of Nephrology. 2007;27(5):495–502. doi: 10.1159/000106782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hopper AH, Tindall H, Davies JA. Administration of aspirin-dipyridamole reduces proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 1989;4(2):140–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mulay SR, Gaikwad AB, Tikoo K. Combination of aspirin with telmisartan suppresses the augmented TGFβ/smad signaling during the development of streptozotocin-induced type I diabetic nephropathy. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2010;185(2):137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cheng H-F, Wang CJ, Moeckel GW, Zhang M-Z, McKanna JA, Harris RC. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor blocks expression of mediators of renal injury in a model of diabetes and hypertension. Kidney International. 2002;62(3):929–939. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sinsakul M, Sika M, Rodby R, et al. A randomized trial of a 6-week course of celecoxib on proteinuria in diabetic kidney disease. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2007;50(6):946–951. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pieper GM, Riaz-ul-Haq R-U. Activation of nuclear factor-κb in cultured endothelial cells by increased glucose concentration: prevention by calphostin C. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1997;30(4):528–532. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199710000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yerneni KKV, Bai W, Khan BV, Medford RM, Natarajan R. Hyperglycemia-induced activation of nuclear transcription factor κB in vascular smooth muscle cells. Diabetes. 1999;48(4):855–864. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koya D, Haneda M, Nakagawa H, et al. Amelioration of accelerated diabetic mesangial expansion by treatment with a PKC β inhibitor in diabetic db/db mice, a rodent model for type 2 diabetes. The FASEB Journal. 2000;14(3):439–447. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mima A, Ohshiro Y, Kitada M, et al. Glomerular-specific protein kinase C-Β-induced insulin receptor substrate-1 dysfunction and insulin resistance in rat models of diabetes and obesity. Kidney International. 2011;79(8):883–896. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ohshiro Y, Ma RC, Yasuda Y, et al. Reduction of diabetes-induced oxidative stress, fibrotic cytokine expression, and renal dysfunction in protein kinase Cβ-null mice. Diabetes. 2006;55(11):3112–3120. doi: 10.2337/db06-0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gilbert RE, Kim SA, Tuttle KR, et al. Effect of ruboxistaurin on urinary transforming growth factor-β in patients with diabetic nephropathy and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(4):995–996. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Satomi N, Sakurai A, Haranaka K. Relationship of hypoglycemia to tumor necrosis factor production and antitumor activity: role of glucose, insulin, and macrophages. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1985;74(6):1255–1260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aljada A, Ghanim H, Saadeh R, Dandona P. Insulin inhibits NFκB and MCP-1 expression in human aortic endothelial cells. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(1):450–453. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Antoniades C, Tousoulis D, Marinou K, et al. Effects of insulin dependence on inflammatory process, thrombotic mechanisms and endothelial function, in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary atherosclerosis. Clinical Cardiology. 2007;30(6):295–300. doi: 10.1002/clc.20101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ye SD, Zheng M, Zhao LL, et al. Intensive insulin therapy decreases urinary MCP-1 and ICAM-1 excretions in incipient diabetic nephropathy. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;39(11):980–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Montagnani M, Chen H, Barr VA, Quon MJ. Insulin-stimulated activation of eNOS is independent of Ca2+ but requires phosphorylation by Akt at Ser(1179) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(32):30392–30398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kuboki K, Jiang ZY, Takahara N, et al. Regulation of endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase gene expression in endothelial cells and in vivo—a specific vascular action of insulin. Circulation. 2000;101(6):676–681. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vicent D, Ilany J, Kondo T, et al. The role of endothelial insulin signaling in the regulation of vascular tone and insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111(9):1373–1380. doi: 10.1172/JCI15211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rask-Madsen C, Li Q, Freund B, et al. Loss of insulin signaling in vascular endothelial cells accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e null mice. Cell Metabolism. 2010;11(5):379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Guan Y, Breyer MD. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): novel therapeutic targets in renal disease. Kidney International. 2001;60(1):14–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: nuclear control of metabolism. Endocrine Reviews. 1999;20(5):649–688. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.5.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Willson TM, Lambert MH, Kliewer SA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and metabolic disease. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2001;70:341–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kota BP, Huang TH-W, Roufogalis BD. An overview on biological mechanisms of PPARs. Pharmacological Research. 2005;51(2):85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ko GJ, Kang YS, Han SY, et al. Pioglitazone attenuates diabetic nephropathy through an anti-inflammatory mechanism in type 2 diabetic rats. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2008;23(9):2750–2760. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metabolism. 2006;3(3):153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Park CW, Kim HW, Ko SH, et al. Long-term treatment of glucagon-like peptide-1 analog exendin-4 ameliorates diabetic nephropathy through improving metabolic anomalies in db/db mice. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2007;18(4):1227–1238. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Erdogdu O, Nathanson D, Sjöholm A, Nyström T, Zhang Q. Exendin-4 stimulates proliferation of human coronary artery endothelial cells through eNOS-, PKA- and PI3K/Akt-dependent pathways and requires GLP-1 receptor. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2010;325(1-2):26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu WJ, Xie SH, Liu YN, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor attenuates kidney injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2012;340(2):248–255. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.186866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Groop P, Cooper M, Perkovic V, et al. Effects of the DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin on albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. Proceedings of the 48th European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Annual Meeting; 2012; Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]