Abstract

Objectives

This cross-sectional survey investigated whether there were ethnic differences in depressive symptoms among British South Asian (BSA) patients with cancer compared with British White (BW) patients during 9 months following presentation at a UK Cancer Centre. We examined associations between depressed mood, coping strategies and the burden of symptoms.

Design

Questionnaires were administered to 94 BSA and 185 BW recently diagnosed patients with cancer at baseline and at 3 and 9 months. In total, 53.8% of the BSA samples were born in the Indian subcontinent, 33% in Africa and 12.9% in the UK. Three screening tools for depression were used to counter concerns about ethnic bias and validity in linguistic translation. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (both validated in Gujarati), Emotion Thermometers (including the Distress Thermometer (DT), Mini-MAC and the newly developed Cancer Insight and Denial questionnaire (CIDQ) were completed.

Setting

Leicestershire Cancer Centre, UK.

Participants

94 BSA and 185 BW recently diagnosed patients with cancer.

Results

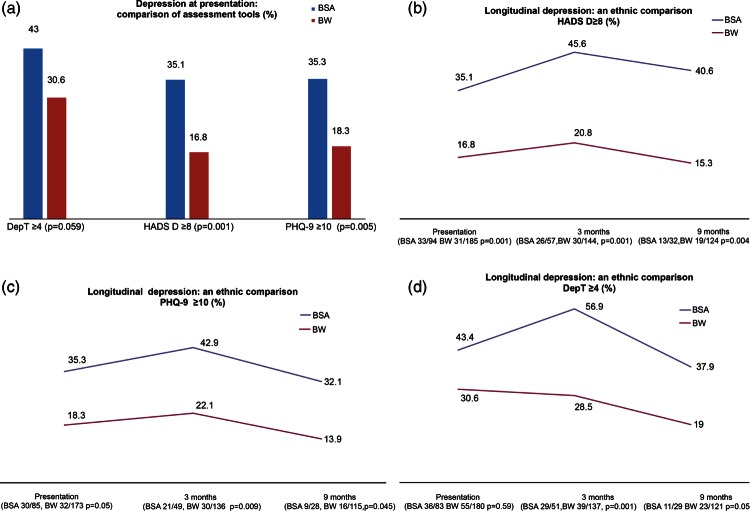

BSA self-reported significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms compared with BW patients longitudinally (HADS-D ≥8: baseline: BSA 35.1% vs BW 16.8%, p=0.001; 3 months BSA 45.6% vs BW 20.8%, p=0.001; 9 months BSA 40.6% vs BW 15.3%, p=0.004). BSA patients used potentially maladaptive coping strategies more frequently than BW patients at baseline (hopelessness/helplessness p=0.005, fatalism p=0.0005, avoidance p=0.005; the CIDQ denial statement ‘I do not really believe I have cancer’ p=0.0005). BSA patients experienced more physical symptoms (DT checklist), which correlated with ethnic differences in depressive symptoms especially at 3 months.

Conclusions

Health professionals need to be aware of a greater probability of depressive symptomatology (including somatic symptoms) and how this may present clinically in the first 9 months after diagnosis if this ethnic disparity in mental well-being is to be addressed.

Keywords: Mental Health, Ethnicity, Depression

Article summary.

Article focus

We investigated whether there were differences in depressive symptoms among British South Asian (BSA) patients with cancer compared with British White (BW) patients over a 9-month period.

To limit cultural bias,we used multiple questionnaires including the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and a version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 developed for India.

We considered how coping strategies were used and whether physical symptoms affected mood.

Key messages

BSA patients had twice the self-reported rate of depressive symptoms as BW patients and five times the incidence of severe depression.

Differences persist for 9 months after baseline assessment.

BSA patients used potentially maladaptive coping strategies far more than BW patients did at baseline assessment.

BSA patients appear to experience a heavier physical symptom burden than BW patients.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first comparison of how BSA and BW patients cope with cancer.

We have used multiple assessment tools.

We have demonstrated highly statistically significant differences in the rate of depressive symptoms between the two groups and marked differences in coping style.

BSA clinical staff were involved in the study. In spite of this, we had difficulty recruiting and retaining BSA patients, especially by 9 months.

Any variations in mood, which may have occurred between the three data collection points, are not represented.

It is most likely that the rates of depressive symptoms are under-reported since anecdotally those who were most distressed often did not feel able to participate in this study.

Self-reported questionnaires indicate the presence of depressive symptoms, but given the absence of psychiatric interviews, this is not diagnostic of a depressive disorder.

Introduction

Depression is one of the strongest determinants of health-related quality of life and it can influence medical care and participation in treatment.1 2 It may also be linked with other serious outcomes including mortality.3 The point prevalence of major depression at any time in the first 2 years following a cancer diagnosis is 14.9% by DSMIV criteria.4 This is 2–4 times that observed in the general population using equivalent criteria.5 An under-researched area is the incidence of depression in ethnic minority patients. Some research suggests that UK ethnic minorities may be more vulnerable to mental illness within the general population than the majority host population,6 leaving the largely unproven impression that they also suffer more distress when diagnosed with cancer. However, ethnic minorities may be less likely to receive high quality care.7 8 Inequalities in access to care, receipt of treatment and mortality are particularly striking among ethnic minorities, the elderly and those with mental ill health in both the UK9–11 and the USA,12–14 where it is a governmental aspiration to remove such disparities.

People originating from the Indian subcontinent account for the largest ethnic minority group in England and Wales (total population 56.1 million). Specifically those classified as Indian are in the majority accounting for 1 412 958, followed by Pakistanis 1 124 511 and Bangladeshis 447 201.15 Most of the Indians born in Africa either sought sanctuary from or were expelled by leaders such as Idi Amin in East African states.

The city of Leicester has one of the highest concentrations of this population (total population 329 836: Indian 93 000, Pakistani 8000, Bangladeshi 3600), which contrasts with the surrounding county (total population 650 489: Indian 54 000, Pakistani 2100, Bangladeshi 2300).15 We define ‘British South Asian (BSA)’ as a person whose ancestry originates in the Indian subcontinent, and who identifies with, or is identified with, their host country.16 A previous pilot study showed a significantly higher incidence in symptoms of depression among BSA patients in Leicester and the local county compared with British White (BW) patients via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) ≥10 (BSA 20.7%; BW 10.4% p=0.001).17 Depressive symptoms were associated with potentially maladaptive coping strategies among both ethnic groups but were employed statistically significantly more frequently by BSA patients. For example, fatalism p=0.0001; denial p=0.019; hopelessness and helplessness, p=0.007.

The findings of our pilot study17 were consistent with the few publications reporting the incidence of depression or distress in ethnic minority patients with cancer. The largest is a meta-analysis of 21 papers which found that US Hispanic patients were significantly more distressed (p=0.0001) and depressed (p=0.04) than the majority population.18

Similar findings were reported from Canada with more distress among ethnic minorities (E and SE Asia, South Asian, First Nation) compared with the majority population (European, Canadian, British p=0.0001). Greater distress was also found among those with lower income (p=0.001).19

Our study addressed how the UK's largest ethnic minority population (BSA) coped with cancer, compared with the host population, by analysing data from a sample of those attending the Leicestershire Cancer Centre.

Feeling distressed or low in mood is an initial emotional response to a diagnosis of cancer, and is part of normal adjustment, if of short duration. If, however, distress persists, it can have a harmful effect on the mental well-being of the individual leading to a risk of depressive symptoms17 20 and a reduction in their quality of life.21–23

This study was designed in reference to the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, which requires an assessment of personality traits within the context of the individual's environment.24 For patients with cancer, this environment includes beliefs about cancer, level of social support, proficiency in host languages, level of literacy, degree of disability, comorbidities, spiritual beliefs, cultural background and economic circumstances.25

The symptom burden on patients with cancer can have a close inter-relationship with psychological well-being. Fatigue and ‘disabilities’ independently predicted depression among patients with lung cancer starting treatment26 and have been observed in prechemotherapy patients with curative cancer.27 A high-symptom burden can persist over time. One in four patients (n=4903) had a high symptom burden 1 year postdiagnosis with depression, fatigue and pain having the greatest impact on their quality of life.28 Similarly, a high-symptom burden at 12 months was reported among patients referred for control of pain and depression (n=405).29 Among Chinese patients with breast cancer (n=285), less distress from physical symptoms immediately after surgery predicted psychological resilience. The study suggested that ineffective symptom control during treatment increased a woman's risk of persistent psychological distress longitudinally. The value of preoperative interventions was highlighted.30

Of particular concern are reports of a higher symptom burden among ethnic minorities, for example, among Hispanic women postchemotherapy for breast cancer.31 A greater ‘unmet need’ for symptom control was implicated among Black and Spanish speaking Hispanic women with breast cancer than White women.32

We report the longitudinal incidence of depressive symptoms among a sample of BSA and BW patients. Selected demographics, coping styles and the burden of patient problems were examined to determine if they were associated with depressive symptoms.

Hypotheses

On the basis of our literature review and pilot studies, we hypothesised that more BSA patients with cancer would self-report depressive symptoms than BW patients over time. We further hypothesised that a greater use of potentially maladaptive coping strategies and a heavier symptom burden would reflect higher rates of depressive symptoms.

Methods

Study procedures

In total, 279 patients who were aware that they had cancer were recruited at the Leicestershire Cancer Centre between September 2007 and January 2010 at their first or second appointment. Patients were recruited by either an English-speaking clinical nurse specialist or one of two radiographers, who between them spoke English, Gujarati and Hindi and Urdu. None were involved in the clinical care of the patients and all received training in ‘Good Clinical Practice’ and in the principles of informed consent. The Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland Ethics Committee approved the study.

Eligible patients were aged 18–85 with a confirmed diagnosis of cancer with evidence of being informed of the diagnosis. Eligible patients were identified by the nurse specialist via the cancer registry with ethnicity confirmed by their surname and by hospital records.

Prior to their attendance, a ‘convenient’ sample of eligible patients were sent an introductory letter outlining the study and inviting them to participate. All correspondence and questionnaires were available in English, Gujarati and Hindi. Consent was sought requesting patients to complete three sets of questionnaires in writing, the first immediately, and then at 3-month and 9-month intervals (table 1).

Table 1.

Recruitment and retention

| BSA | BW | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient participation | |||

| Total consented | 179 | 329 | 508 |

| Consented/completed Q1 | 94 | 185 | 279 |

| Completed Q2 | 56 | 144 | 200 |

| Completed Q3 | 32 | 117 | 149 |

| Retained in study from consent until completion of study (%) | 34 | 63 | 53.4 |

| Reasons for withdrawal from study | |||

| Consented but did not complete a questionnaires | 85 | 51 | 136 |

| Died | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Returned to country of origin | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Family member reversed consent of patient | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Patient verbally withdrew | 12 (14.1%) | 12 (23.5%) | 24 |

| Avoidant behaviour | 55 (64%) | 0 (0%) | 55 |

| Lost to follow-up (excluding travel abroad) | 0 | 29 | 29 |

| Not interested in research subject | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Already involved in another study | 0 | 5 | 5 |

BSA, British South Asian; BW, British White.

Questionnaires

Patients completed the HADS-D33 and The Emotion Thermometers (ETs),34 which include the Depression and Distress Thermometers (DTs)35 and Depression Thermometer (Dep T). The DT problem checklist identified the patient's symptom burden. All are validated but were not initially available in Gujarati or Hindi. A commercial company undertook an iterative back-translation process.36 A version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which was already validated into Gujarati and Hindi, having been adapted for use in India, was the third questionnaire used.37 Several tools were used to address the concern that some were ethnically biased.

An adaptive coping strategy (fighting spirit) and potentially maladaptive strategies (hopelessness/helplessness, fatalism, anxiety preoccupation and cognitive avoidance) were assessed via the Mini-MAC scale.38 The locally developed Cancer Insight and Denial questionnaire (CIDQ) included question 38 from the original MAC questionnaire to assess the use of denial. The vast majority of participants chose to complete the first questionnaires at home, returning them by post. Subsequent questionnaires were posted to participants.

Personal statements illustrating how patients coped were generated by two qualitative questions, ‘How would you describe your current illness?’ and ‘What does having cancer mean to you?’

Statistical analysis

Depressive symptoms were assessed by HADS-D, ET Thermometers and PHQ-9.

The revised classification of the original HADS-D identified the severity of depressive symptoms (normal 0–7, mild 8–10, moderate 11–14 and severe 15–21.39 A threshold of ≥11 identified patients with moderate symptoms. However, following the recommendation to have a lower threshold for patients with cancer than in general practice, ≥8 was selected for HADS-D.40 This is supported by a review of 747 papers using HADS-D, where the best balance between sensitivity and specificity was achieved most often when using the cut-off ≥8 (Cronbach's α coefficient 0.80).41 Threshold scores of ≥10, ≥15, ≥20 for PHQ-9 were in accordance with the original recommended scores.42 The current recommended threshold for the DT is ≥4 and this was retained in the ET43 and for this analysis. A prior power calculation determined that a sample size of 86 participants was required for each ethnic group.

Graphs denote 95% CIs. Summary scores for selected coping strategies were from the Mini-MAC and the denial indicators in the CIDQ. Reference was made to individual indicators. Longitudinal data at baseline and at 3 and 9 months are reported.

Computation of frequencies, percentages and arithmetic median was conducted to identify patterns in the data. Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables detected differences between the ethnic groups and the direction of these relationships. Spearman's Rank Order Tests (rho) explored correlations between depressive symptoms (HADS-D as a continuous variable) and deprivation.44 We report analysis by age, gender, deprivation, tumour site, place of birth and ethnicity.

χ² describes the relationship between categorical variables. The extent to which patients used each coping strategy and how their use changed longitudinally are described. Associations between each strategy and depressive symptoms are reported. Qualitative data were recorded verbatim and when they were in Gujarati, they were translated to English. Analysis was performed via SPSS V.18.

Results

Ninety-four BSA patients were recruited. The BSA sample largely represents patients with cancer within the Leicester Indian population and although of interest to other BSA populations with cancer, these findings may not be representative. In total, 53.8% were born in the Indian subcontinent, 33% in Africa of Indian descent and 12.9% in the UK. Hindus accounted for 53.2%, Muslims for 25.5% and Sikh for17%. All 185 BW patients were recruited. Several cancer sites are represented. The largest was 114 patients with breast cancer. The educational attainment, religion and place of birth were self-reported by participants. The demographic characteristics of this sample showed significant differences between ethnic groups in terms of their socioeconomic status and educational attainment. These details and the patients’ sex, age, cancer site and treatment intent are listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics

| Total (%) | British South Asian (BSA) | British White (BW) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 279 | 94 | 185 | |

| Male | 88 (31.5) | 25 (26.6%) | 64 (34.6%) | χ2 p=0.223 |

| Female | 190 (68) | 69 (73.4%) | 121 (65.4%) | |

| Age | WRST Z=−14.480 p=0.0005 |

|||

| Median (IQR) | 57.1 (19) | 61 (14) | ||

| IMDS (1–20)* | 6.5 (IQR 4.10) | 16 (11.18) | WRST Z=−14.435 p=0.0005 |

|

| Median (IQR) | ||||

| Educational attainment | ||||

| No formal education | 30 (10.7) | 27 (29.7%) | 3 (1.7%) | χ2 p=0.0005 |

| Junior school (up to 11) | 8 (2.8) | 4 (4.4%) | 4 (2.2%) | |

| Senior school (15–16) | 97 (34.7) | 16 (17.8%) | 81 (44.8%) | |

| Sixth form (17–18) | 22 (7.8) | 11 (12.1%) | 11 (6.1%) | |

| University or college | 115 (41.2) | 33 (36.3%) | 82 (45.3%) | |

| 272 pts† | ||||

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 148 (53) | Nil | 148 (80%) | |

| Muslim | 24 (9) | 24 (25.5%) | Nil | |

| Hindu | 50 (18) | 50 (53.2%) | Nil | |

| Sikh | 16 (6) | 16 (17%) | Nil | |

| Other | 4 (1) | 1 (1.06%) | 3 (1.6%) | |

| None | 37 (13) | Nil | 34 (18.4%) | |

| Questionnaire language | ||||

| English | 267 (96) | |||

| Gujarati | 11 (4) | |||

| Urdu (verbal translation) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| Place of birth | ||||

| UK | 195 (70) | 13 (14%) | 182 (98.4%) | |

| British forces overseas | 2 (0.7) | Nil | 2 (1.08%) | |

| The USA | 1 (0.3) | Nil | 1 (0.52%) | |

| Africa | 31 (11.1) | 31 (33%) | Nil | |

| Indian subcontinent | 50 (17.9) | 50 (53%) | Nil | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Breast | 114 (41) | 34 (36.2%) | 80 (43.2%) | |

| Colorectal | 45 (16) | 15 (16%) | 30 (16.2%) | |

| Gynaecological | 33 (12) | 19 (20.2%) | 15 (8.1%) | |

| Prostate | 23 (8) | 3 (3.2%) | 20 (10.8%) | |

| Lung | 19 (7) | 6 (6.4%) | 13 (7.0%) | |

| Other | 43 (15) | 17 (18%) | 26 (14.6%) | |

| Type of treatment | χ2 p=0.966 |

|||

| Radical (curative intent) | 188 (67.4) | 64 (68.1%) | 124 (67.4%) | |

| Palliative | 91 (32.6) | 30 (31.9%) | 61 (33%) | |

| Time from diagnosis to first interview (weeks) | WRST Z=−14.506 p=0.0005 |

|||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (3) | 8 (3) | 6 (3) |

*Index Multiple Deprivation Scale (Office National Statistics, 2007).

†Number of patients who provided their educational attainment.

WRST, Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Demographics and depressive symptoms

Age was not associated with depression among BSA patients (r: HADS-D, p=0.62). Older BW patients were less likely to be depressed (r: HADS-D, p=0.03). There was no statistical differences based on gender, with women having a higher mean depression score than men at baseline (HADS-D; women 4 (range 0–18) IQR 1.7; men 3 (range 0–20) IQR 1.6) p=0.46.

Of these, 67.4% patients received radical treatment with the aim of cure or long-term control of disease and 32.6% received palliative treatment given with no expectation of cure. Unexpectedly, there was no evidence that receiving palliative as opposed to radical (curative intent) treatment influenced a difference in depressive symptoms (HADS-D ≥8 baseline p=0.088, 3 months p=0.588 9 months p=1.0). Those with lung cancer, who generally have a poor prognosis, had the highest median depression score via HADS-D of 5 (IQR 3.7, scale 0–21). The lowest score was attributed to people with prostate cancer (Md 1 (IQR 0.5); (see online supplementary table S1).

Data on educational attainment were recoded into two groups with those patients reaching an educational level of 15/16 being removed. This represented groups at either end of educational attainment. Those educated at the highest level had notably less depressive symptoms than those with either no formal education or only up to the age of 11 (HADS-D ≥8, Lowest Ed. 14/30 (46.7%); Highest Ed. 18/97 (18.6%) p=0.004. However, these results should be treated with caution, given that the educational systems of India and the UK are different. For example, some patients listing no formal education spoke up to five languages fluently. Individual results in patients who reported little formal education were consistent across assessment tools, suggesting adequate comprehension.

There was no significant difference in depressive symptoms between those BSA patients originating from Africa compared with those from the Indian subcontinent at baseline (MW: Africa 31/80 Md 4 (2.9) Indian subcontinent Md 5.5 (2.11) Z=−1.184 p=0.23). Neither was there a significant difference in the experience of symptoms frequently associated with depression such as pain (p=0.23), sleep disturbances (p=0.91) and fatigue (p=0.52).

Since socioeconomic deprivation is closely associated with being a member of an ethnic minority, we considered the extent to which deprivation influenced the strength of the relationship between ethnicity and depressive symptoms. Although there was a strong association between ethnicity and deprivation (MW r=0.503, p=0.0005), deprivation had minimal influence on the strength of the relationship between ethnicity and depression when comparing Pearson product-moment correlations with partial correlation calculations (table 3).

Table 3.

Influence of deprivation

| Ethnicity and depressive symptoms corrected for deprivation | N | Pearson product-moment correlation | p Value | N | Correlation corrected for deprivation | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS-D | 277 | −0.274 | 0.0005 | 276 | −0.235 | 0.0005 |

| PHQ-9 | 256 | −0.257 | 0.0005 | 255 | −0.208 | 0.001 |

| Dep T | 262 | −0.131 | 0.033 | 261 | −0.118 | 0.057 |

Dep T, Depression Thermometer; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Depressive symptoms at baseline

All three assessment tools showed approximately double the incidence of depression in BSA patients compared with BW patients (figure 1A–D and see online supplementary table S2). Severe depression was also more common in the BSA groups as demonstrated using a higher HADS-D score ≥11 (BSA 23/94 (24.5%) BW 11/185 (5.9%) p=0.001). A similar trend was seen using a higher PHQ-9 threshold ≥15 (BSA 13/85 (15%) BW 10/173 (5%) p=0.04).

Figure 1.

Longitudinal depressive symptoms by HADS, PHQ-9 and Dep T. Dep T, Depression Thermometer; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Longitudinal trends in depressive symptoms

All tools indicated how BSA patients were more vulnerable to depressive symptoms in contrast to BW patients. HADS-D ≥8 suggested significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms among BSA patients longitudinally than BW patients (figure 1B). All three assessment tools indicated a slight decrease in depressive symptoms among BSA patients at 3 months. Depression rates had not fallen lower than those at baseline by 9 months, although the ethnic difference remained (figure 1C,D).

Coping strategies

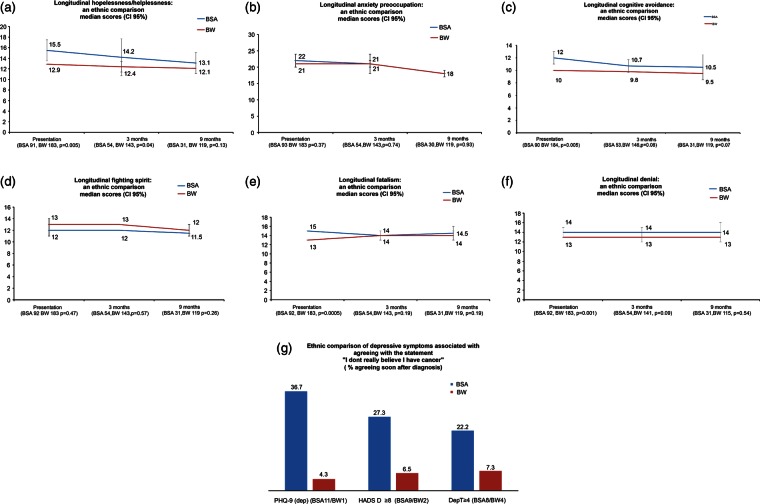

BSA patients used coping strategies differently from BW patients particularly at baseline when greater use of potentially maladaptive strategies was associated with higher rates of depressive symptoms (see online supplementary tables S3–S5).

Hopelessness/helplessness (Mini-MAC)

its an awful thing to happen…feeling hopeless

BSA patient No.16 at baseline

Although initially the majority of patients did not express helplessness or hopelessness, BSA patients were far more likely to do so (p=0.0005). For example, more BSA patients than BW patients agreed with the statement ‘I feel completely at a loss about what to do’ (BSA 31 (33%); BW 23 (12.4%) p=0.0005). Across the study period, BSA patients had higher helplessness/hopelessness scores than BW patients, although use decreased over time for both groups (figure 2A). Helplessness/hopelessness is sometimes considered to be a substitute for depression, so it was not surprising that over time more patients (BSA and BW combined) felt helplessness/hopelessness and also acknowledged depressive symptoms (MW: PHQ-9 ≥11/HADS-D ≥8 p=0.0005).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal coping strategies.

Anxiety preoccupation

Cancer has totally changed my life. I am worried, anxious about my treatment and what lies ahead as this is the second occasion I am going through this. BSA No.103.

There was a negligible ethnic difference in the use of anxiety preoccupation. Over time this strategy was used less (figure 2B). It was strongly associated with depression (HADS-D and PHQ-9, p=0.0005). These patients were more likely to report depressive symptoms longitudinally (PHQ-9: baseline p=0.0005, 3 months p=0.0005, 9 months p=0.0005).

Cognitive avoidance

Cancer is “…something that I put to the back of my mind and don't let it interfere with my day to day life” BW No.118.

Initially, BSA patients used cognitive avoidance to cope more than BW patients (MW: p=0.0005; figure 2C). For example, ‘I deliberately push all thoughts of cancer out of my mind’ (BSA 61/93 (65.6%); BW 63/185 (34.4%), p=0.0005). Over time, this ethnic difference continued but was only statistically significant at baseline, as illustrated by a comparison of median scores (figure 2C). At baseline, as one sample, those who used cognitive avoidance were more likely to have symptoms of depression (MW: PHQ-9 p=0.007; HADS-D ≥8 p=0.001; Dep.T ≥4 p=0.002). Over time, avoidant patients did not continue to be depressed (HADS-D; 3 months, p=0.2; 9 months, 0.14).

Fighting spirit

(I see cancer) as a challenge…a temporary state….a hurdle to get over

BW patient No.172.

It means I have a fight on my hands but I'm determined to get better

BW No.354.

A large number of patients in both ethnic groups approached their illness with an ‘adaptive’ coping strategy of ‘fighting spirit’ (figure 2D). For example, ‘I am determined to beat this disease’ (BSA 85/93 (91.4%); BW 170/185 (91.9%) p=1.0). There was little ethnic difference in the extent to which patients used this coping strategy (MW baseline p=0.47, 3 months p=0.57, 9 months p=0.2).

Fatalism

It's horrible. Why me? My mum died from cancer. My sisters have cancer. Why is this happening? I wish I'd never woken up after my operation

BSA No.125

More BSA patients were fatalistic when diagnosed with cancer than BW patients at baseline assessment (MW: p=0.0005). However, this was largely based on one of five Mini MAC indicators, ‘I've put myself in the hands of God’ (BSA 71/94 (75.5%); BW 60/185 (32.4%) p=0.0005). There was a gradual decrease in fatalism in both ethnic groups by 9 months, although it persisted among BSA patients (figure 2E). Those who were fatalistic were more likely to experience depressive symptoms (MW: HADS-D ≥8 p=0.024; PHQ-9, p=0.003) but not by the Dep T ≥4 (p=0.101).

Insight and denial (CIDQ)

I'm not ill

Written at the top of an uncompleted questionnaire by a patient having chemotherapy for breast cancer following surgery. BW No.127 at baseline.

…part of me still feels there is nothing wrong with me and this is happening to someone else. This is presumably my way of handling it all. BW No.311 at 9 months

Of those who used denial, potentially a maladaptive coping strategy,45 BSA patients were over-represented, most notably at baseline assessments (p=0.001). The ethnic gap remained longitudinally (figure 2F). Of the three tools assessing depression, only PHQ-9 indicated an association between denial and depression, albeit weakly (MW: p=0.039).

To facilitate comparisons with Roy's 2005 study,17 analysis of the single indicator ‘I don't really believe I have cancer’ originating from the MAC questionnaire was repeated. At baseline, 229/278 patients (82%) accepted the reality of their diagnosis by disagreeing with the statement. Of the 27 patients who did not believe that they had cancer, more were BSA (BSA 19/93 (20.2%); BW 8/185 (4.3%), p=0.0001). Of interest, 23 patients agreed with this statement ‘sometimes’ (BSA 12 (52.2%); BW 11 (47.8%)). There was a strong trend towards BSA patients, who denied their diagnosis, to be more depressed at baseline, but the sample numbers were too low to warrant analysis at 9 months (figure 2G).

We considered whether causes of distress listed in the distress thermometer checklist explained ethnic differences in depressive symptoms. Cancer treatments offered to both groups were similar, so they did not influence findings. Critically BSA patients experienced more distress from physical symptoms of illness and treatment than BW patients. There were 17 physical symptoms listed in the DT checklist. In 13 categories, BSA had statistically significantly increased symptoms compared with BW patients. For example, pain (BSA 51/83 (58%), BW 59/180 (32.8%) p=0.0001), mouth sores (BSA 21/88 (24.1%), BW 12/179 (6.7%) p=0.0001) and fevers (BSA 18/87 (20.7%), BW 5/177 (2.8%) p=0.0001). At 3 months, significantly higher percentages of BSA patients reported problems with pain, mouth sores, nausea, skin, washing and dressing and getting around as causes for distress, which were not reflected in BW patients. By 9 months, the differences had narrowed with the exception of pain (BSA 19/31 (61.3%) vs BW 41/121 (33.9%) p=0.009; table 4).

Table 4.

Ethnic differences in reporting of physical symptoms

| Problem | n | No | Per cent | Yes | Per cent | χ² | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Baseline | BSA | 88 | 37 | 42 | 51 | 58 | |

| BW | 180 | 121 | 67 | 59 | 32.8 | 0.0001 | ||

| 3 months | BSA | 53 | 14 | 26.4 | 39 | 73.6 | ||

| BW | 141 | 92 | 65.2 | 49 | 34.8 | 0.0001 | ||

| 9 months | BSA | 31 | 12 | 38.7 | 19 | 61.3 | ||

| BW | 121 | 80 | 66.1 | 41 | 33.9 | 0.009 | ||

| Nausea | Baseline | BSA | 83 | 56 | 68 | 27 | 32.5 | |

| BW | 178 | 141 | 79 | 37 | 20.8 | 0.058 | ||

| 3 months | BSA | 54 | 29 | 53.7 | 25 | 46.3 | ||

| BW | 140 | 91 | 65 | 49 | 35 | 0.198 | ||

| 9 months | BSA | 29 | 22 | 75.9 | 7 | 24.1 | ||

| BW | 121 | 104 | 86 | 17 | 14 | 0.574 | ||

| Getting around | Baseline | BSA | 85 | 59 | 69 | 26 | 30.6 | |

| BW | 177 | 155 | 88 | 22 | 12.4 | 0.001 | ||

| 3 months | BSA | 55 | 33 | 60 | 22 | 40 | ||

| BW | 140 | 112 | 80 | 28 | 20 | 0.007 | ||

| 9 months | BSA | 31 | 23 | 74.2 | 8 | 25.8 | ||

| BW | 120 | 95 | 79.2 | 25 | 20.8 | 0.724 | ||

| Bathing and dressing | Baseline | BSA | 86 | 62 | 72 | 24 | 27.9 | |

| BW | 178 | 167 | 94 | 11 | 6.2 | 0.0001 | ||

| 3 months | BSA | 55 | 42 | 76.4 | 13 | 23.6 | ||

| BW | 140 | 129 | 92.1 | 11 | 7.9 | 0.006 | ||

| 9 months | BSA | 31 | 25 | 80.6 | 6 | 19.4 | ||

| BW | 120 | 104 | 86.7 | 16 | 13.3 | 0.574 | ||

| Mouth sores | Baseline | BSA | 87 | 66 | 76 | 21 | 24.1 | |

| BW | 179 | 167 | 93 | 12 | 6.7 | 0.0001 | ||

| 3 months | BSA | 55 | 37 | 67.3 | 18 | 32.7 | ||

| BW | 140 | 114 | 81.4 | 26 | 18.6 | 0.053 | ||

| 9 months | BSA | 31 | 25 | 80.6 | 6 | 19.4 | ||

| BW | 121 | 109 | 90.1 | 12 | 9.9 | 0.255 | ||

| Fevers | Baseline | BSA | 87 | 69 | 79 | 18 | 20.7 | |

| BW | 177 | 172 | 97 | 5 | 2.8 | 0.0001 | ||

| 3 months | BSA | 54 | 42 | 77.8 | 12 | 22.2 | ||

| BW | 139 | 127 | 91.4 | 12 | 8.6 | 0.020 | ||

| 9 months | BSA | 31 | 26 | 83.9 | 5 | 16.1 | ||

| BW | 119 | 108 | 90.8 | 11 | 9.2 | 0.436 | ||

| Skin | Baseline | BSA | 84 | 42 | 50 | 42 | 50 | |

| BW | 179 | 156 | 87 | 23 | 12.8 | 0.0001 | ||

| 3 months | BSA | 56 | 26 | 46.4 | 30 | 53.6 | ||

| BW | 142 | 96 | 67.8 | 46 | 32.4 | 0.009 | ||

| 9 months | BSA | 31 | 16 | 51.6 | 15 | 48.4 | ||

| BW | 121 | 86 | 71.1 | 35 | 28.9 | 0.065 |

BSA, British South Asian; BW, British White.

Discussion

With the exception of our pilot study,17 we are not aware of another comparison of how BSA and BW patients cope with cancer. It should be of major concern to healthcare policymakers in the UK that this study provides evidence that there is a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms among BSA patients soon after the cancer diagnosis than BW patients. The percentages vary depending on the assessment tool used but all showed the same trend. The BSA rates for depression were twice that for BW patients using two tools. Of these, 35.1% of BSA compared with 16.8% of BW patients (p=0.001) had depressive symptoms measured on HADS-D (≥8). This was confirmed on a version of PHQ-9 ≥10 developed for India (35.3% BSA vs 18.3% BW p=0.05). This is a critical finding since this is almost six times higher than reported within the UK general population using the same assessment tool (6%).46 Depression rates for BW patients (HADS-D ≥8, 16.8%; PHQ-9 18.3%) were similar to those reported in a recent meta-analysis of patients with cancer (16.3%), being approximately 2.5 times higher than in the general population.4 What is disturbing is the incidence of more severe depression in BSA patients, which is reflected in their HAD-D score ≥11 (BSA 24.5% vs BW 5.9% p=0.0001). These findings supported trends in other studies, notably our pilot study. Using the threshold HADS-D ≥10, Roy17 reported that BSA 20.7% vs BW 10.4% (p=0.001) had moderate depressive symptoms. These concur with other reports, which suggest that ethnic minority patients with cancer experience more psychological distress than patients from host populations.16 17 47 48 However, the BSA population is heterogeneous. It would be grossly simplistic to assume that all BSA patients respond psychologically in the same way, given the breadth and diversity of their religious and cultural influences. However, Indian Hindus comprised the majority of our BSA sample and our findings may be of particular relevance to this subgroup.

What is very interesting is that HADS-D, PHQ-9 and Dep.T showed higher levels of depressive symptoms in both ethnic groups at 3 months after baseline, this being steeper among BSA patients. Although the symptoms decreased, BSA consistently reported higher rates of depression than BW patients longitudinally. These findings confirmed our first hypothesis.

A counter-intuitive finding in this study is the similarity of depressive symptoms in patients being treated with curative intent (radical) and palliative patients. Although there were fewer questionnaires returned at 3 and 9 months, the ratio of radical and palliative patients remained the same (HADS-D ≥8 baseline p=0.08, 3 months p=0.58, 9 months p=1.0). In fact, this finding is consistent with a recent meta-analysis.4

At baseline, the rates of fatalism/helplessness/hopelessness and domains of denial were far higher among BSA patients and there was a strong correlation between these potentially maladaptive coping strategies and the incidence of depression in both ethnic groups. Helplessness/hopelessness is strongly associated with depression,20 49 50–54 as we found in this study. A similar pattern was seen in the use of cognitive avoidance. Fatalism too was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, as demonstrated on both the PHQ-9 and HADS-D, which supports research from India55 56 and the UK57 58 into the use of potentially maladaptive behaviours.

In our previous study,17 denial was significantly related to depression in both BW and BSA patients. BSA patients were far more likely to agree with the statement in the MAC questionnaire (Question 38) ‘I don't really believe I have cancer’. In this study, a minority of patients denied their diagnosis, but again it was more common among BSA patients using the same indicator until 9 months (MW baseline p=0.0005, 3 months p=0.001, 9 months p=0.2). Initially, this was strongly associated with depression; however, the sample numbers were too small to consider longitudinal associations.

What is puzzling is that although BSA patients remained more depressed than BW patients longitudinally, by 3 and 9 months the use of coping strategies did not explain this. At 3 months, the only difference was in the helplessness/hopelessness scores (p=0.043) and by 9 months, the ethnic differences in the use of coping strategies were insignificant. Interestingly, by 9 months, the trend towards higher depression among BSA patients remained. Even taking into account a lag time for the alleviation of depressive symptoms after less use of maladaptive coping, there remains an incomplete explanation as to why more BSA patients in particular remain so distressed. Our hypothesis that a greater use of maladaptive coping strategies would reflect higher rates of depressive symptoms was therefore only partially confirmed. A retrospective audit into referral to psycho-oncology or prescribing patterns of psychotrophic medication in the two groups did not suggest a difference that could account for this.

We considered whether the burden of physical symptoms explained this ethnic gap. BSA patients were more likely to report physical symptoms at baseline and at 3 months. This was particularly true for pain, nausea, skin concerns, mouth sores, tingling and feeling swollen. These symptoms peaked at 3 months, but there was no statistically significant difference in symptomatology between the two groups by 9 months with the exception of pain. However, the ethnic differences in depressive symptoms persisted up to 9 months. Possible explanations include the somatisation of physical symptoms being undetected, inadequate symptom management, non-compliance due to a lack of literacy and language skills or patient's preference for traditional medicines for symptom control purposes. Our findings reflect the greater symptom burden found in other ethnic minority patients with cancer, such as among the Chinese and Hispanic populations.31 32 This study supports the original hypothesis that more BSA patients with cancer would self-report depressive symptoms than BW patients over time. Our hypothesis that a greater use of potentially maladaptive coping strategies would reflect higher rates of depression among BSA patients was supported but only until the 3 month point. A heavier symptom burden among BSA patients does appear to contribute to depression rates among this ethnic minority compared with the host population.

Limitations

Limitations to the study are acknowledged. The BSA sample largely represents patients with cancer within the Leicester Indian population and, although of interest to other BSA cancer populations, these findings may not represent them. In addition, there was a large sample of patients with breast cancer, which risks under-representation of those patients with other body site cancers.

Difficulties in recruiting and retaining BSA participants by 9 months reduced the sample size.59 Self-reported questionnaires indicate the presence of depressive symptoms, but given the absence of psychiatric interviews, this is not diagnostic of a depressive disorder.

Modulations in patient mood between the three data collection points are not represented. It is also likely that depressive symptoms are under-reported since anecdotally those who were most distressed often did not feel able to participate in the study.

Recommendations

The decreased use of maladaptive coping strategies among BSA patients in the first few months after diagnosis requires investigation, the aim being to reduce the associated distress earlier along the cancer trajectory. Evidence of greater distress among BSA patients caused by a heavier symptom burden than among BW patients also needs further study since several potential causes are reversible by proactive patient assessments during cancer treatment and follow-up.

Conclusion

Health professionals need to be aware of a greater probability of depressive symptomatology and how this may present clinically, including somatic symptoms, in the first 9 months after diagnosis if this ethnic disparity in mental well-being is to be addressed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Professor Aziz Sheikh (Edinburgh), Dr Amandeep Dhadda, Dr Raj Roy (Hull), Dr Muthu Kumar (Derby) and Dr Anu Gore (Leicester) helped in the design of the trust questionnaire. Mrs Ghislaine Boyd (radiotherapy manager) was unfailingly helpful. Mr Rob Day of Pfizer (UK) supplied the Indian version of PHQ-9, which had been developed for India by Pfizer India.

Footnotes

Contributors: KL participated in patient recruitment, data collection, data analysis and manuscript production. KL and SK participated in translation of study documentation, patient recruitment, data collection and manuscript production. AJM participated in study design, data analysis and manuscript production. NR participated in study design, patient recruitment and manuscript production. RPS participated in study design, acquiring funding, patient recruitment, data analysis and manuscript production. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The financial support was provided by Hope Against Cancer.

Competing interests: AJM designed the Cancer Insight Denial questionnaire. KL was funded by the Hope Against Cancer charity, and KI and SK by the University Hospital of Leicester NHS Trust Charitable Funds.

Ethics approval: This study was given ethical approval by the Leicester, Northamptonshire & Rutland Research Ethics Committee 2—REC reference 06/Q2502/78.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All available data have been included in the manuscript and online supplementary tables.

References

- 1.Kennard BD, Stewart SM, Olvera R, et al. Nonadherence in adolescent oncology patients: preliminary data on psychological risk factors and relationships to outcome. J Clin Psychol Med S 2004;11:31–9 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steginga SK, Campbell A, Ferguson M, et al. Socio-demographic, psychosocial and attitudinal predictors of help seeking after cancer. Psychooncology 2008;17:997–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer 2008;115:5349–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:160–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinz A, Krauss O, Hauss JP, et al. Anxiety and depression in cancer patients compared with the general population. Eur J Cancer Care 2010;19:522–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weich S, Nazroo J, Sproston K, et al. Common mental disorders and ethnicity in England: the EMPIRIC study. Psychol Med 2004;34:1543–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:334–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 2004;54:78–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.All party parliamentary group on cancer Report of the all party parliamentary group of cancer's enquiry into inequalities in cancer. 2009. http://www.appq-cancer.uk

- 10.Department of Health Cancer reform strategy. UK: The Stationery Office, 2007. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_081007.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health Improving outcomes a strategy for cancer. London: Department of Health, 2011. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_123394.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goss E, Lopez AM, Brown CL, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: disparities in cancer care. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2881–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services President's cancer panel: American's demographic and cultural transformations: implications for cancer. Washington, DC, 2011:1–100 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services HHS Action plan to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, 2011. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/npa/files/Plans/HHS/HHS_Plan_complete.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office for National Statistics Census ethnic groups: local authorities in England and Wales Table KS201EW, 2011. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/search/index.html?newquery=KS201EW

- 16.Bhopal R. Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: for reflection and debate. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:441–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy R, Symonds RP, Kumar DM, et al. The use of denial in an ethnically diverse British cancer population: a cross-sectional study. Br J Cancer 2005;92:1393–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luckett T, Butow PN, King MT, et al. A review and recommendations for optimal outcome measures of anxiety, depression and general distress in studies evaluating psychosocial interventions for English-speaking adults with heterogeneous cancer diagnoses. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:1241–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson LE, Groff SL, Maciejewski O, et al. Screening for distress in lung and breast cancer outpatients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4884–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akechi T, Okuyama T, Sugawara Y, et al. Major depression, adjustment disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder in terminally ill cancer patients: associated and predictive factors. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1957–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, et al. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:3137–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke JA, Inu TS, Silliman RA, et al. Patients’ perceptions of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3777–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoyer M, Johansson B, Nordin K, et al. Health-related quality of life among women with breast cancer-a population-based study. Acta Oncologica 2011;50:1015–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazarus RS, Folkman S, Adams S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moos RH, Holahan CJ. Dispositional and contextual perspectives on coping: toward an integrative framework. J Clin Psychol 2003;59:1387–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopwood P, Stephens RJ. Depression in patients with lung cancer: prevalence and risk factors derived from quality-of-life data. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:893–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breen SJ, Baravelli CM, Schofield PE, et al. Is symptom burden a predictor of anxiety and depression in patients with cancer about to commence chemotherapy? MJA 2009;190:s99–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, et al. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis. Cancer 2011;117:2779–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Johns SA, Theobold D, et al. Somatic symptoms in cancer patients trajectory over 12 months and impact on functional status and disability. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:765–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam WWT, Bonanno GA, Mancini AD, et al. Trajectories of psychological distress among Chinese women diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho Oncol 2010;19:1044–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu OS, Crew KD, Jacobson JS, et al. Ethnicity and persistent symptom burst in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2009;3:241–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon J, Malin JL, Tisnado DM, et al. Symptom management after breast cancer treatment: is it influenced by patient characteristics? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;108:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell AJ, Baker-Glenn EA, Park B, et al. Can the distress thermometer be improved by additional mood domains? Part II. What is the optimal combination of Emotion Thermometers? Psycho-oncology 2010;19:134–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer 1998;82:1904–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol 1970;1:185–216 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kochhar PH, Rajadhyaksha SS, Suvarna VR. Translation and validation of brief patient health questionnaire against DSM IV as a tool to diagnose major depressive disorder in Indian patients. J Postgrad Med 2007;53:102–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watson M, Law M, Dossantos M, et al. The Mini-Mac; further development of the mental adjustment to cancer scale. J Psychosoc Oncol 1994;12:33–46 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morse R, Kendell K, Barton S. Screening for depression in people with cancer: the accuracy of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Clin Eff Nurs 2005;9:188–96 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosomatic Res 2002;52:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9 validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:605–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2011, December 10th 2010-last update, NCCN guidelines: distress management [Homepage of National Comprehensive Cancer Network], [Online]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp(accessed 25 Sep 2011)

- 44. Office for National Statistics 2011, Neighbourhood Statistics ‘Summary Statistics’, citing indices of deprivation, 2007, UK Department for Communities and Local Government [Homepage of Office for National Statistics], [Online]. http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/ [2007–2011]

- 45.Lazarus RS. Coping theory and research: past, present and future. Psychosom Med 1993;55:234–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2011, February 2010-last update, Clinical knowledge summaries (CKS) clinical topics. Depression. http://www.cks.nhs.uk/depression/management/scenario_bereavement/view_full_scenario#-402794 (accessed 26 Jun 2012)

- 47.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, et al. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual Life Res 2007;16:413–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ell K, Sanchez K, Vourlekis B, et al. Depression, correlates of depression and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3052–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Hopper JL. Age-specific norms and determinants of anxiety and depression in 731 women with breast cancer recruited through a population-based cancer registry. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:755–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schou I, Ekeberg O, Ruland CM, et al. Pessimism as a predictor of emotional morbidity one year following breast cancer surgery. Psycho-oncology 2004;13:309–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brothers BM, Andersen BL. Hopelessness as a predictor of depressive symptoms for breast cancer patients coping with recurrence. Psycho-oncology 2009;18:267–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lo C, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal and lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grassi L, Travado L, Gil F, et al. Hopelessness and related variables among cancer patients in the Southern European Psycho-Oncology Study (SEPOS). Psychosomatics 2010;51:201–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johansson M, Ryden A, Finizia C. Mental adjustment to cancer and its relation to anxiety, depression, HRQL and survival in patients with laryngeal cancer—a longitudinal study. BMC Cancer 2011;11:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS, Channabasavanna SM, et al. Levels of anxiety and depression in patients receiving radiotherapy in India. Psycho-oncology 1996;5:343–6 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kishore J, Ahmad I, Kaur R, et al. Beliefs and perceptions about cancers among patients attending radiotherapy OPD in Delhi, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2008;9:155–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szczepura A, Price C, Gumber A. Breast and bowel cancer screening uptake patterns over 15 years for UK South Asian ethnic minority populations corrected for differences in socio-demographic characteristics. BMC Public Health 2008;8:346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miles A, Rainbow S, von Wagner C. Cancer fatalism and poor self-rated health mediate the association between socioeconomic status and uptake of colorectal cancer screening in England. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011;20:2132–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Symonds RP, Lord K, Mitchel AJ, et al. Recruitment of ethnic minorities into clinical trials: experience from the front lines. Br J Cancer 2012;107:1017–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.