Abstract

Objective

To examine the effect of an outdoor smokefree law in parks and on beaches on observed smoking in selected venues.

Methods

The study involved repeated observations in selected parks and beaches in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. The main outcome measure was changes in observed smoking rates in selected venues from prelaw to 12 months postlaw.

Results

No venue was 100% smokefree at the 12-month postlaw observation time point. There was a significant decrease in observed smoking rates in all venues from prelaw to 12-month postlaw (prelaw mean smoking rate=20.5 vs 12-month mean smoking rate=4.7, p=0.04). In stratified analysis by venue, the differences between the prelaw and 12-month smoking rates decreased significantly in parks (prelaw mean smoking rate=37.1 vs 12-month mean smoking rate=6.5, p=0.01) but not in beaches (prelaw mean smoking rate=2.9 vs 12-month mean smoking rate=1.0, p=0.1).

Conclusions

Smokefree policies in outdoor recreational venues have the potential to decrease smoking in these venues. The effectiveness of such policies may differ by the type and usage of the venue; for instance, compliance may be better in venues that are used more often and have enforcement. Future studies may further explore factors that limit and foster the enforcement of such policies in parks and beaches.

Keywords: Public Health, Epidemiology

Article summary.

Article focus

This is one of the few published studies specifically examining compliance with smokefree bylaws in parks and on beaches.

Although jurisdictions throughout the world are beginning to introduce and implement smokefree regulations in outdoor public spaces, little is known about the longitudinal effects of such policies on patterns of smoking behaviour.

Key messages

This study suggests that these bylaws may be associated with reductions in the observed smoking rate in each venue, but they do not fully eliminate the behaviour.

Understanding the changing pattern of smoking behaviour after the introduction of a smokefree bylaw can enhance the development of future policies aimed at limiting tobacco exposure in outdoor public settings.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The bylaw content may differ between jurisdictions, and therefore these findings may not be easily generalisable to other jurisdictions.

However, the methods employed in this study may be a useful preliminary evaluation tool for other jurisdictions considering that they will be implementing similar bylaws.

Introduction

Several public health policy initiatives have been developed which aim to address the adverse health effects associated with tobacco use and tobacco smoke exposure. In particular, smokefree laws and similar legislation aim to reduce and limit second-hand tobacco smoke (SHS) exposure in public venues. Proper enforcement and compliance smokefree initiatives in indoor settings have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing indoor air pollution with positive outcomes on health such as enhancing respiratory health of workers in the hospitality industry1–3 and reducing cardiovascular4–7 and asthma-related hospital admissions7 8 in several communities.

With the success of smokefree initiatives in indoor settings, there is increasing support for such policies to expand in scope to include outdoor public venues. Commonly cited reasons to endorse smokefree legislation in outdoor venues include: litter control, positive role modelling for youth, decreasing opportunities to smoke and reducing SHS exposure.9 Although studies have demonstrated that average outdoor levels of SHS exposure are often lower than indoor levels,10 the US Surgeon General's report on involuntary smoking concluded that there is no known ‘safe level’ of SHS exposure.11 Evidence suggests that even brief exposure (eg, 30 min) to SHS has adverse cardiovascular health consequences,12 which may confer a more salient health risk for those who are vulnerable (ie, individuals with existing cardiovascular or respiratory conditions).

As popular recreational spaces, public parks and beaches may be important venues to target in order to limit exposure to SHS in the outdoor settings. Depending on the size and use of such venues, a single smoker can expose many people in a very short time period, with greater exposure among individuals proximal to the smoking source.10 Smokefree policies in parks, beaches and other outdoor recreational venues have already been introduced in jurisdictions throughout the world, including Canada, Australia, the USA, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Thailand, India and Singapore.13–15 With the growing public and official support for smokefree laws which encompass outdoor spaces,9 it is important to examine the effectiveness of such laws, particularly in relation to levels of public compliance.

In April 2010, the City of Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation and City Council unanimously passed resolutions to prohibit the smoking of any substance—including tobacco in any form, water pipes and marijuana—in the city's parks and beaches as the most recent component of a comprehensive tobacco control initiative within the city. This resolution resulted in the enactment of a municipal smokefree bylaw in all parks and beaches within the city, starting on 1 September 2010. The Smoking on the Margins project (SOTM) involves a detailed analysis of the new smokefree legislation in order to examine the health and health equity effects, including the potential for differential effects of the bylaw on diverse subpopulations in terms of adoption, implementation and compliance. To address compliance, SOTM includes an examination of the effects of the smokefree bylaw on observed smoking prevalence in parks and on beaches, specifically to compare differences in smoking rates before the law was introduced and at 1 year postimplementation.

The purpose of this paper is to present data on observed smoking practices in selected parks and beaches in Vancouver before and after the implementation of the outdoor smokefree bylaw. A key element of the study design was based on our understanding that parks and beaches in different socioeconomic neighbourhoods of the city are used at different rates and by different people. The beaches are almost exclusively on the west side of the city, located in affluent areas and frequented by tourists. In contrast, the parks in Vancouver are widely distributed across the city in differing socioeconomic neighbourhoods.

Methods

Observation venues

For data collection, we selected three frequently used beaches (English Bay, Kitsilano Beach and Second Beach in Stanley Park) and parks (Oppenheimer Park, Victoria Park and Victory Square) in Vancouver. We collected observation data 2 weeks prior to the bylaw coming into effect (14–15 August 2010) on the date of implementation (1 September 2010), and at 1 week (7–8 September, 2010), 1 month (1–2 October 2010), 8 months (20–21 May 2011), 9 months (2 July 2011), 10 months (30 July 2011) and 12 months (3 September 2011) after the implementation of the bylaw in all the six venues.

Observation protocol

For each venue, research team members monitored the frequency and location of smoking during a 30 min time period, based on adaptations to a protocol developed by Kaufman et al.16 Maps comprising aerial orthophotographic images of each venue were printed before each observation time period and team members were trained on conducting observations at the specified venues prior to the actual study observation time. We limited observation periods to afternoons and evenings on weekends (Friday–Sunday) when greater use of these outdoor venues was anticipated. The same observation time frame was adopted at each subsequent observation period. Information on the maximum number of persons and total number of persons smoking (ie, smoking cigarettes, pipes and marijuana) in the venue were recorded, as well as the duration of time spent in each venue and average daily temperature. If a group were sharing cigarettes (or pipes or marijuana joints), each person who was observed smoking during the specified time frame was counted as a smoker. Moreover, the number of people in each venue was obtained by two observers using clickers to determine the total number of persons in a venue during the observation time period. One observer counted the total number of people in the venue as they entered the venue, whereas the second observer counted the number of persons smoking. The protocol for this study was approved by the University of British Columbia Children's and Women's Research Ethics Board.

Data analysis

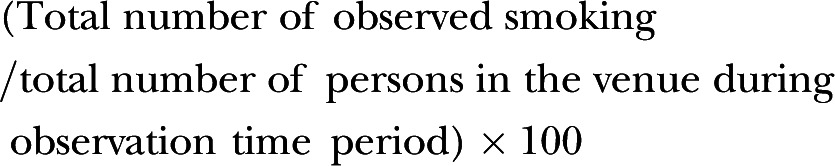

Using the smoker's location, data were collected by direct observation; we created maps in ArcGIS V.10 using a ‘heads up’ digitisation technique, spatially locating the observed smoker's locations using an aerial orthophotograph base layer of all the observation sites in Vancouver. We calculated the proportions and rates of observed smoking in each venue at each observation time point by the following formulae:

|

We used medians with IQRs or means with SDs as appropriate to describe the frequency of persons and smoking in the venues as well as the time spent in each venue and temperature during the observation time points. We also determined differences in the main outcome variables between parks and beaches using the Mann-Whitney U test. Friedman tests were used to determine whether there was a difference over time in the smoking rate with the post hoc pairwise comparison between the prelaw smoking rates and the 12-month postlaw rate based on the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. For post hoc analyses, we applied the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons to a level of 0.008 (ie, α=0.05/6 multiple comparisons). We used mixed modelling for repeated measures to assess the overall changes in smoking rate between the prelaw and postlaw periods with time spent in the venue and type of site (beach or park) included as variables in the model. This mixed model strategy is appropriate to use in this case since there are observations from the same sites over time. Finally, we considered this mixed model for beaches and parks separately to assess the differential impact of the law in each type of venue. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute Inc (2002–2010), SAS V.9.3 for Windows, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Characteristics of observation venues

There was a median of 157.5 persons (IQR=64.0 to 700.0) in all venues during the observation time points with a median of 14 persons smoking (IQR=7.0 to 18.0) and a median smoking rate of 5.1 smokers/100 persons (IQR=1.8 to 16.7). The observed smoking proportions and frequencies in the six selected venues at each observation time period are given in table 1. The mean temperature during the periods of observation was 17.1°C (SD=3.1, range 12.5–22.7°C). The mean length of time spent in each observation time period was 30 min (SD=5.3 min). Although there were significantly more people on the beaches than in the parks (median=467 vs median=85, Mann-Whitney U=337.5; p=0.004), there was a lower frequency of observed smoking in the beaches (median=9 vs median=16, Mann-Whitney U=547.5; p=0.02). The overall smoking rate was significantly lower in the beaches than in the parks (median=1.8 vs median=16.7, Mann-Whitney U=645.0; p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Observed frequency and rates of smoking at selected Vancouver parks and beaches before and after a smokefree law

| Prelaw smoking rate* (number of persons smoking/population in venue) August 2010 |

1-week postlaw smoking rate* (number of persons smoking/population in venue) September 2010 |

1-month postlaw smoking rate* (number of persons smoking/population in venue) October 2010 |

8-month postlaw smoking rate* (number of persons smoking/population in venue) May 2011 |

9-month postlaw smoking rate* (number of persons smoking/population in venue) 2 July 2011 |

10-month postlaw smoking rate* (number of persons smoking/population in venue) 31 July 2011 |

12-month postlaw smoking rate* (number of persons smoking/population in venue) September 2011 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parks | |||||||

| Victory Square | 64.0 (16/25) | 28.3 (17/60) | 36.4 (16/44) | 4.7 (4/85) | 25.7 (19/74) | 25.9 (22/85) | 9.9 (18/182) |

| Victoria Park | 19.6 (10/51) | 15.8 (18/114) | 14.0 (16/114) | 23.8 (10/42) | 15.4 (22/143) | 3.9 (32/812) | 7.4 (13/176) |

| Oppenheimer Park | 31.3 (15/48) | 28.1 (18/64) | 16.7 (9/54) | 16.8 (17/101) | 12.2 (12/98) | 0.5 (7/1523) | 8.3 (24/289) |

| Parks subtotal | 33.1 (41/124) | 22.3 (53/238) | 19.3 (41/212) | 13.6 (31/228) | 16.8 (53/315) | 2.5 (61/2420) | 8.5 (55/647) |

| Beaches | |||||||

| English Bay | 2.1 (15/700) | 5.6 (11/197) | 3.2 (15/467) | 1.8 (24/1350) | 1.4 (19/1391) | 0.6 (31/4787) | 1.8 (25/1426) |

| Kitsilano Beach | 1.8 (9/493) | 2.9 (4/140) | 4.1 (7/172) | 2.3 (18/800) | 1.2 (11/926) | 0.5 (6/1192) | 0.5 (4/825) |

| Second Beach | 4.7 (9 /193) | 6.3 (3/48) | 6.3 (4/64) | 0.0 (0/42) | 0.0 (0/35) | 0.7 (2/274) | 0.8 (3/384) |

| Beaches subtotal | 2.3 (33/1386) | 4.7 (18/385) | 3.7 (26/703) | 1.9 (42/2192) | 1.3 (30/2352) | 0.6 (39/6253) | 1.2 (32/2635) |

| Total (parks and beaches combined) | 4.9 (74/1510) | 11.4 (71/623) | 7.3 (65/827) | 3.0 (73/2420) | 3.1 (83/2667) | 1.2 (100/8673) | 2.6 (87/3382) |

*The smoking rate at each observation time point=number of persons smoking in venue/number of persons in venue × 100.

Subtotals are shown in italics; totals are shown in bold.

Changes in smoking rates at postlaw time periods

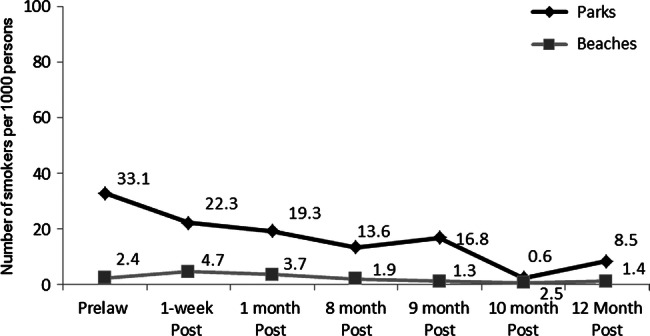

Figure 1 illustrates the changes in smoking rates in parks and beaches (separately) at each observation time point. There were significant changes in the overall smoking rates in all venues combined (χ2 (df=6)=21.7, p=0.001). Post hoc analysis with the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests was conducted to examine differences between the prelaw and postlaw time points. Median (IQR) smoking rates for the prelaw and 12-month postlaw periods were 12.1 (2.1 to 31.3) and 4.6 (0.8 to 8.3), respectively. There was no significant difference in the smoking rate in all venues at the 12-month time point as compared with the prelaw time point (Z=1.36, p=0.2).

Figure 1.

Changes in the rate of observed smokers in selected Vancouver parks (n=3) and beaches (n=3) from prelaw to 12-month postlaw.

Differential changes in smoking rates between the prelaw and 12-month postlaw periods by venue

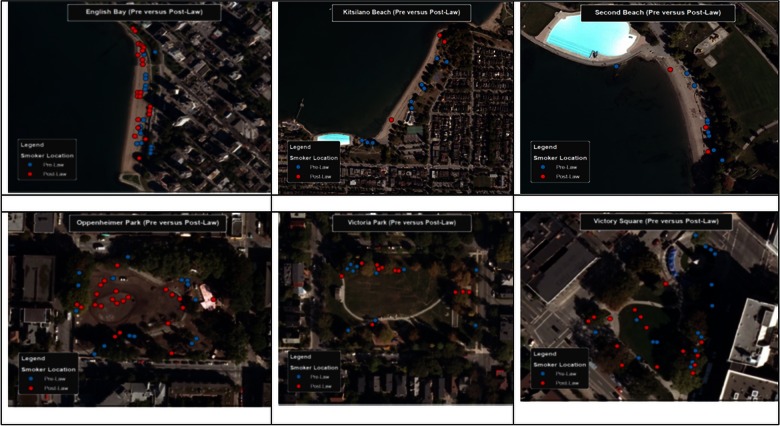

Figure 2 illustrates the changes in the locations and number of persons smoking at the observation timepoints in the six venues. Although there was an increase in the total absolute number of persons observed smoking in all venues from the prelaw (n=74) to the 12-month postlaw (n=87) time periods, there was also an increase in the total number of persons visiting the venues (prelaw n=1510 vs the 12-month postlaw n=3382). Employing a mixed model procedure including the time spent in the venue and the type of venue (parks vs beaches) as covariates, there was a significant reduction in smoking rates in all venues from prelaw to 12-month postlaw (prelaw mean rate=20.5 vs 12-month mean rate=4.7, F=2.6 (df=6,29); p=0.04). When the analyses were stratified by venue, we found that the changes in smoking rates (ie, adjusted for time spent in venues) was significant among beaches (F=6.2 (df=6,11), p=0.01) but not among parks (F=2.5 (df=6,11), p=0.1); however, the reduction between the prelaw and 12-month smoking rates was significant in parks (prelaw mean rate=37.1 vs 12-month mean rate=6.5, t=3.1 (df=11); p=0.01) but not in beaches (prelaw mean rate=2.9 vs 12-month mean rate=1, t=1.8 (df=11); p=0.1).

Figure 2.

Changes in the locations of observed smokers in selected Vancouver parks (n=3) and beaches (n=3) at prelaw and 12-month postlaw.

Discussion

Our current study is among the few existing published examinations of compliance with smokefree bylaws in outdoor public venues, specifically in parks and beaches. In a recent observational study of smoking behaviours in outdoor spaces in Toronto, Canada, Kaufman et al16 found poor compliance with regulations prohibiting smoking proximal to building entrances. Similar to the study by Kaufman et al, our current study findings suggest that although the introduction of smokefree regulations is associated with the reduction in the number of smokers in such venues, they may not completely extinguish the behaviour. As noted, we found that the total observed smoking rates in all venues (3 parks and 3 beaches) was lower at 12 months after the bylaw was introduced than at the pre-bylaw time point. However, no venue had 100% compliance with the smokefree bylaw at the 12-month observation time point.

When analyses were stratified by type of venue (park or beach), we found a significantly greater reduction in smoking in parks relative to beaches at the 12-month postlaw period. Prior to the law, the rates of observed smoking behaviour in the parks were higher than that observed in the beaches, even though there were a greater number of persons in the beaches during the observation periods relative to the parks. A possible explanation for the differential effects of the smokefree law in parks and beaches may be related to the ways in which parks and beaches are used. In Vancouver, the use of parks and beaches as recreational venues differs both due to the physical and built environment of each venue and the cultural norms within the city. For example, Kitsilano Beach has several volleyball nets and walking/jogging trails and individuals who visit these beaches may be likely to engage in such activities. The parks in our study did not have many options for sporting activities (with the exception of Victoria Park, which had a children's playground and bocce ball pit), and therefore the individuals visiting the parks may have been likely to engage in more leisure activities (such as picnicking, hanging out, etc). However, further speculations on the observed differential effects of the law in parks relative to the beaches are unsupported by the scope of our current study. Future studies will be required to determine factors which may influence the impact (ie, adherence and compliance) of outdoor smokefree laws in parks and beaches.

A few important limitations need to be considered in interpreting the findings of our study. First, the observational data collection is based on the assumption that there are minimal changes in the patterns of use in each venue at each observation time point. To address this, we accounted for the potential confounding variables in our analyses, including changes in the mean daily temperature during observation times and time spent in each observation site. However, it is important to note that some of the observation dates were on Canadian statutory holidays (eg, Victoria Day—2 May and Labour Day—2 September), which may have resulted in an increase in the number of individuals (and smoking) observed in the parks and on beaches relative to other observation time points. Second, because the selected venues varied in their sizes (ie, in most cases, beaches are larger than parks), it is possible that these differences could have affected the absolute counts of observed smoking between parks and beaches. However, the potential effect of venue size on observed smoking was minimised by using smoking rates and repeated observations in the same venues over time. Third, we did not use any other objective method to determine reductions in smoking in the venues, such as cigarette litter. The validity of observed smoking can be strengthened by using such objective markers of smoking. For example, the recent evaluation of the effects of a smokefree policy in the parks of New York also employed cigarette butt counts in addition to observed smoking to determine changes in smoking behaviour in outdoor parks following a smokefree law.17 Fourth, given the uniqueness of the different statutes or bylaws prohibiting outdoor smoking and the culture and social norms of different jurisdictions, these findings may not be easily generalisable to other localities. Nonetheless, the methods employed in our study to examine the effects of the smokefree law may be a useful and feasible means to understand the effects of outdoor smokefree laws in other jurisdictions.

Examining compliance with outdoor smokefree laws is critical to understanding the effectiveness of these laws as a mechanism for tobacco control. On the basis of our findings, we would suggest that outdoor smokefree bylaws may have differential impacts in different types of venues. It may be the case that different settings may require tailored strategies of enforcement to ensure compliance. Future studies with longitudinal observations of the effect of smokefree laws in different recreational outdoor settings may be beneficial in developing sound and enforceable health policies that can protect the public from the harms associated with tobacco use and exposure.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CO drafted the initial manuscript and assisted with the data analysis. AJ and SA edited the drafts of the manuscript and assisted with data analysis. AP and WR edited the drafts of the manuscript and assisted with data collection. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), grant number GIR-112694.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Observational maps and statistical code are available from the lead author.

References

- 1.Eagan TML, Hetland J, Aaro LE. Decline in respiratory symptoms in service workers five months after a public smoking ban. Tob Control 2006;15:242–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn EJ, Rayens MK, York N, et al. Effects of a smoke-free law on hair nicotine and respiratory symptoms of restaurant and bar workers. J Occup Environ Med 2006;48:906–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayres JG, Semple S, MacCalman L, et al. Bar workers health and environmental tobacco smoke exposure (BHETSE): symptomatic improvement in bar staff following smoke-free legislation in Scotland. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:339–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sargent RP, Shepard RM, Glantz SA. Reduced incidence of admissions for myocardial infarction associated with public smoking ban: before and after study. BMJ 2004;328:977–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khuder SA, Milz S, Jordan T, et al. The impact of a smoking ban on hospital admissions for coronary heart disease. Prev Med 2007;45:3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pell JP, Haw S, Cobbe S, et al. Smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2008;359:482–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naiman A, Glazier RH, Moineddin R. Association of anti-smoking legislation with rates of hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. CMAJ 2010;182:761–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackay D, Haw S, Ayres JG, et al. Smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for childhood Asthma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1139–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson G, Wilson N, Edwards R. At the frontier of tobacco control: a brief review of public attitudes toward smoke-free outdoor places. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:584–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klepeis NE, Ott WR, Switzer P. Real-time measurement of outdoor tobacco smoke particles. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 2007;57:522–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heiss C, Amabile N, Lee AC, et al. Brief secondhand smoke exposure depresses endothelial progenitor cells activity and endothelial function: sustained vascular injury and blunted nitric oxide production. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:1760–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation Municipalities with smokefree beach laws. Berkeley: American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global Smokefree Partnership The trend toward smokefree outdoor areas. FCTC Article 8-plus Series 2009

- 15.Non-Smokers’ Rights Association Smoke-Free Bylaw Provisions in Canada. Exceeding Provincial/Territorial Legislation, 2010

- 16.Kaufman P, Griffin K, Cohen J, et al. Smoking in urban outdoor public places: behaviour, experiences, and implications for public health. Health Place 2010;16:961–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johns M, Coady M, Chan C, et al. Evaluating New York City's smoke-free parks and beaches law: a critical multiplist approach to assessing behavioral impact. Am J Community Psychol 2013;51:254–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.