Abstract

Objectives

To assess residual long-term microcirculation abnormalities by capillaroscopy, 15 years after retiring from occupational exposure to vinyl chloride monomer (VCM).

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Allier, one of the major areas of polyvinyl chloride production in France.

Participants

We screened 761 (97% men) retired workers exposed to chemical toxics. Exposure to chemicals other than VCM excluded potential participants.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

These participants underwent a medical examination including a capillaroscopy, symptoms of Raynaud and comorbidities, as well as a survey to determine exposure time, direct or indirect contact, type of occupation, smoking status and time after exposure. A double blind analysis of capillaroscopic images was carried out. A control group was matched in age, sex, type of occupation.

Results

179/761 retired workers were only exposed to VCM at their work, with 21 meeting the inclusion criteria and included. Exposure time was 29.8±1.9 years and time after exposure was 15.9±2.4 years. Retired workers previously exposed to VCM had significantly higher capillaroscopic modifications than the 35 controls: enlarged capillaries (19% vs 0%, p<0.001), dystrophy (28.6% vs 0%, p=0.0012) and augmented length (33% vs 0%, p<0.001). Time exposure was linked (p<0.001) with enlarged capillaries (R2=0.63), dystrophy (R2=0.51) and capillary length (R2=0.36). They also had higher symptoms of Raynaud (19% vs 0%, p=0.007) without correlation with capillaroscopic modifications.

Conclusions

Although VCM exposure was already known to affect microcirculation, our study demonstrates residual long-term abnormalities following an average of 15 years’ retirement, with a time-related exposure response. Symptoms of Raynaud, although statistically associated with exposure, were not related to capillaroscopic modifications; its origin remains to be determined.

Keywords: Occupational & Industrial Medicine, Chemical Pathology, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

Vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) exposure induces microcirculation abnormalities, which can be diagnosed by capillaroscopy.

Residual long-term abnormalities following retirement required investigation.

Key messages

Our results demonstrated residual long-term abnormalities following an average of 15 years’ retirement, with a time-related exposure response.

Symptoms of Raynaud, although statistically associated with exposure, were not related to capillaroscopic modifications; its origin remains to be determined.

Strengths and limitations of this study

-

▪

The strong points are that this study had a rigorous selection criteria of exclusively VCM exposed participants, avoided confounding factors and focused on retired workers of at least 15 years after the end of occupational VCM exposure.

-

▪

The main limitation is that the pathophysiology of Raynaud after VCM exposure remains unclear.

Introduction

Vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) is primarily used in the manufacture of plastics and also serves as a raw material in organic synthesis. VCM is an aliphatic hydrocarbon also known as chloroethene. Its polymerisation leads to a synthetic resin called polyvinyl chloride, commonly abbreviated as PVC. PVC is the third most widely produced plastic, after polyethylene and polypropylene.1 PVC can be made softer and more flexible by the addition of phthalates, and may also replace rubber. Thus, PVC is widely used as follows: pipes and water distribution, a substitute for painted wood (eg, window frames, sills, flooring), electrical cable insulation, inflatable products, waterproof clothing (eg, coats, skiing equipment, shoes), healthcare products (eg, containers, tubing, catheters), food packaging, dental appliances and vinyl records.1

Harmless in its polymeric form, workers handling the finished PVC product are perfectly safe. In contrast, the at-risk phase lies in the manual descaling of autoclaves used for the polymerisation where workers can come into contact with it during its monomer state.2 Chronic intoxication by the gaseous monomer VCM is linked to several symptoms such as:3 asthenia and dizziness,3 Raynaud's syndrome,4 5 digestive ulcera with nausea and anorexia,3 systemic symptoms of arthralgia and myalgia,3 trophic cutaneous symptoms and sclerosis. It has also been suspected in the onset of acroosteolysis4 6 7 and hepatocellular carcinoma.8 9 More generally, VCM exposure involves chromosomal aberrations and increased carcinogenic risk.10 Even if VCM-related diseases may have a genetic base, they are also linked to prolonged occupational VCM exposure.5 11

Scleroderma-like microvascular abnormalities have also been described on exposed workers.12–14 The most common and non-invasive means of investigating these abnormalities is capillaroscopy. The widespread identification of individuals most at risk could enable early detection and management strategy.15 The residual effects of VCM on microcirculation have been shown only once on 15 workers who had ceased their VCM exposure 6 months prior to testing.13 However, the residual and long-term abnormalities following retirement are unknown. Our hypothesis was that higher capillaroscopic abnormalities would be found in the VCM exposed group than in the control group.

Therefore, the aim of our cross-sectional study was to investigate residual and long-term capillaroscopic abnormalities following retirement, after 15 years without VCM exposure.

Methods

Participants

We enrolled male retired workers exposed to VCM in PVC production. They provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the human ethics committees from the Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital, France. To be eligible, participants had to be: male (due to the male dominance in this workforce), retired, aged over 60 years, with at least a 5-year occupational exposure to VCM, a time after VCM exposure of at least 5 years, and no exposure to chemicals other than VCM. Moreover, participants with diabetes mellitus were also excluded as it might interfere with microcirculation,16–21 as well as individuals declaring the use or previous use of treatments that might alter microcirculation.

Participants responded to a survey to determine exposure time, direct or indirect contact, type of occupation, time after exposure and smoking history. They underwent a medical examination including a capillaroscopy, symptoms of Raynaud and comorbidities such as pathologies that may interfere with microcirculation (arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia) or pathologies potentially linked with VCM exposure (cardiovascular or respiratory diseases).22

A control group was matched in age, sex, type of occupation. They were recruited via advertisements. Selection criteria for this group also included no occupational or leisure chemical exposure, and no diabetes mellitus.16–21

Capillaroscopy

A nailfold capillaroscopy was performed on all fingers of each patient, excluding the thumbs.23 The nailfold capillaroscopies of the fingers were captured in images and electronically stored. The same investigator conducted all the capillaroscopies. A double blind analysis of capillaroscopic images was completed on de-identified data.

The outcomes were the five following classical criteria used in capillaroscopy: density, length, diameter, dystrophy and haemorrhage. Criteria for abnormalities were defined as follows: decreased capillary density <10/mm (avascular zone <7/mm),24 augmented capillary length >300 μm,24 25 increased capillary diameter >25 µm25 (megacapillary >50 µm)26 27 and dystrophy was associated with capillary branching >15%.28 Haemorrhage is defined as the microvascular extravasation of the red blood cells linked to the damage of the vessel wall.27

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean percentage change and SD.

The main judgement criterion for abnormal microcirculation was the presence of at least one abnormality in capillaroscopy. Under the assumption of similar proportions of abnormalities as that reported during a VCM exposure,12–14 our sample calculation indicated that we would need 27 participants in each of the exposed and non-exposed groups to find a change in probability of 35% (ie, 40% in exposed vs 5% in non-exposed) for a power of 80% and a two-sided α of 5%. When we considered an exposed to non-exposed sample ratio of 1 : 2, 19 and 38 participants, respectively, were needed in the exposed and non-exposed groups. Under the assumption of 0% prevalence in the non-exposed group, sample sizes of 13 exposed and 26 non-exposed were required.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, V.19. Correlations were used for interobserver reliability. The Gaussian distribution for each parameter was assessed by a Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons between groups (exposed vs control) were made through the usual tests: χ² test for categorical variables (or Fisher's exact test where appropriate) and Student t test for quantitative variables (or Kruskal-Wallis if assumptions of normal distribution were violated). Significance was accepted for a p<5%. The links between continuous variables were analysed using linear regression. The links between binary and continuous variables were analysed with logistic regression (Nagelkerke R Square). Multivariate models were used to predict the relationship between the capillary parameters and other parameters such as exposure time and time after exposure.

Results

Participants

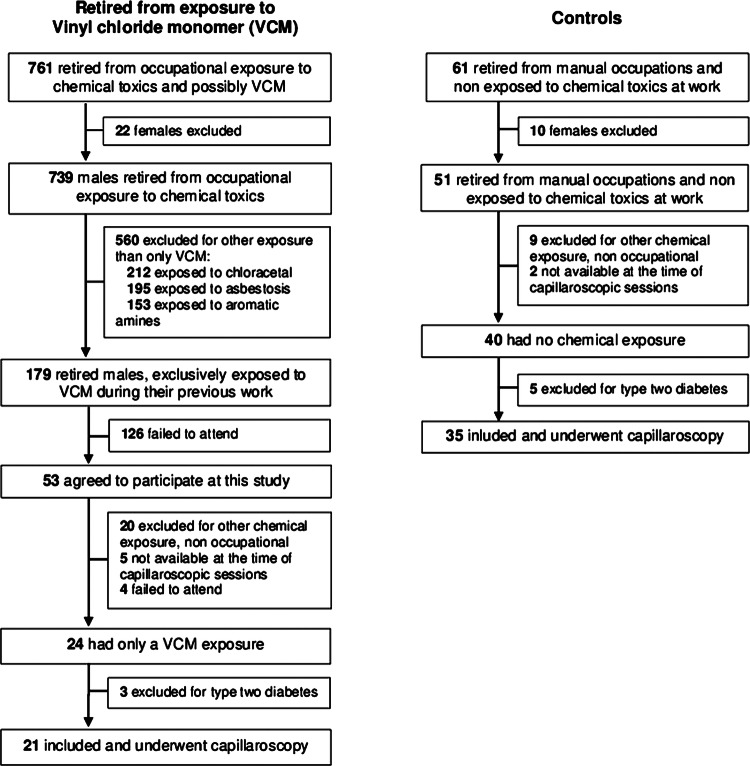

We screened 761 (97% men) retired workers exposed to chemical toxics from two leading enterprises involved in PVC production (n=435 and n=91), as well as participants from many subcontracting companies (n=235), also known to have been exposed to VCM. The strict selection criteria of exposure only to VCM reduced the sample size to 21 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart.

Thirty-five age-matched controls were also recruited without occupational or leisure time exposure to chemical toxics.

Main capillaroscopic outcomes

There were no missing data. Inter-rater reliability was confirmed with correlations exceeding 0.70 for each parameter. The mean of the values of the two investigators is presented in table 1. Concerning the qualitative data, when a disagreement occurred, the two observers again analysed the data together and requested the opinion of a third expert. The disagreement occurred only for two decreased capillary density <10/mm, and one capillary branching >15%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants, exposure to VCM and capillaroscopic outcomes

| Retired from exposure to VCM (n=21) | Controls (n=40) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74.4±2.9 | 76.3±3.2 | NS |

| Type of occupation: blue collar workers, ‘manual’ | 100% | 100% | NS |

| Exposure to VCM | |||

| Direct contact with VCM | 100% | 0 | <0.001 |

| Exposure time (years) | 29.8±1.9 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Time after exposure (years ) | 15.9±2.4 | – | – |

| Main capillaroscopic outcomes | |||

| Density | |||

| Mean density (mm) | 8.6±0.4 | 8.8±0.3 | NS |

| Decreased capillary density <10/mm (n (%)) | 9 (43) | 16 (46) | NS |

| Avascular zone <7/mm (n (%)) | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Length | |||

| Mean length (μm) | 291±14 | 254±9 | 0.020 |

| Augmented capillary length >300 μm (n (%)) | 7 (33) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Diameter | |||

| Mean diameter of capillaries (μm) | 28.9±0.9 | 25.7±0.6 | 0.006 |

| Enlarged capillaries >25 μm (n (%)) | 4 (19) | 0 | 0.007 |

| Megacapillary >50 μm (n (%)) | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Dystrophy | |||

| Capillary branching >15% (n (%)) | 6 (29) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Haemorrhage (n (%)) | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Symptoms of Raynaud | |||

| n (%) with Raynaud | 4 (19) | 0 | 0.007 |

| Participants with medications which could induce Raynaud (n (%)) | 2 (9) | 4 (11) | NS |

| Other causes of Raynaud | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Respiratory diseases | 2 (9) | 6 (17) | NS |

| Cardiovascular diseases (except high blood pressure) | 4 (19) | 5 (14) | NS |

| Myocardial infraction | 3 (14) | 3(9) | NS |

| Routine medications, n (%) of patients treated for | |||

| Blood pressure | 7 (33) | 13 (37) | NS |

| Lipid lowering | 4 (19) | 6 (17) | NS |

| Smoking (n (%)) | 9 (43) | 18 (51) | NS |

VCM, vinyl chloride monomer.

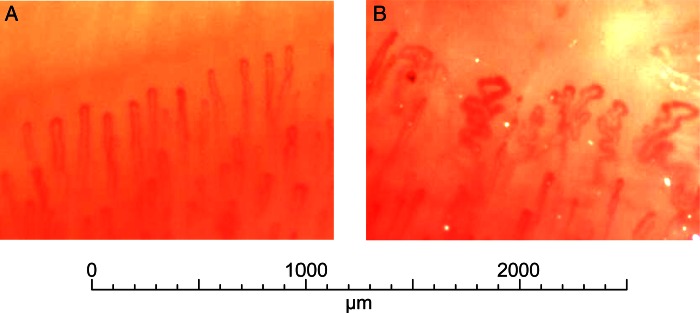

Compared with controls, retired workers previously exposed to VCM had higher capillaroscopic abnormalities: enlarged capillaries (0% vs 19%, p<0.001), dystrophy (0% vs 28.6%, p=0.0012; figure 2) and augmented length (0% vs 33%, p<0.001). The mean length was 15% higher in the exposed group than in controls (p=0.020), as well as having a 12% greater diameter of the capillaries (p=0.006; table 1).

Figure 2.

Normal capillaroscopy on a control participant (A) and capillaroscopy with dystrophia >15% on a retired worker exposed to vinyl chloride monomer for 37 years, with no treatment and no comorbidity, non-smoking (B).

Exposure

Exposure time was 29.8±1.9 years and time after exposure was 15.9±2.4 years. Time of exposure to VCM was strongly linked with enlarged capillaries (Nagelkerke R Square approximation of 63%, p<0.001), with dystrophy (Nagelkerke R Square approximation of 51%, p<0.001), and modestly linked with capillary length expressed as binary data (Nagelkerke R Square approximation of 36%, p<0.001) or as quantitative data (R2=8%; p=0.031; table 1). Age was not associated with capillaroscopic abnormalities. No multivariate models improved the results from simple regressions.

Symptoms of Raynaud

The VCM exposed group also had more symptoms of Raynaud (19% vs 0%, p=0.007) independent of the capillaroscopic modifications (table 1).

Comorbidities and smoking

Neither the respiratory nor the cardiovascular diseases were associated with VCM exposure. However, we combined both groups to explore the potential associations between the capillaroscopic parameters and high blood pressure, dyslipidaemia and smoking. Capillary length in the participants medicated for arterial hypertension (n=20/61) did not differ from that in participants without hypertension. Participants treated with lipid lowering drugs with dyslipidaemia (n=10/61) showed a trend for a higher capillary length than participants without dyslipidaemia (p=0.079). Finally, there were no capillaroscopic differences between smokers and non-smokers. However, smokers who had been exposed to VCM tended to have a higher capillary length than non-smokers (p=0.073).

Discussion

Principal findings of the study

Changes in microcirculation persist for at least 15 years following occupational VCM exposure, with a time-related exposure response. Symptoms of Raynaud, although statistically associated with exposure, were not related to pathological capillaroscopic changes.

What the study adds

The microcirculation changes following VCM exposure have been previously shown on 15 workers who ceased their occupational exposure 6 months prior to testing.13 Our study supports these results over a longer period following VCM exposure—15 years.

The dose responsiveness of VCM exposure and compromised capillarisation is generally,13 but not always,12 reported. Although daily VCM doses may have been more informative, the current study was restricted to years of exposure. Thus, we are limited to describing associations with an exposure time—response rather than a dose-response. The number of years of exposure is an easy question for physicians to ask of workers during risk assessment protocols.

The absence of changes in microcirculation on less exposed workers29 resulted in a suggestion that a threshold of exposure exists. This finding is supported by previous studies showing that long-term exposure (>8 years) induced greater chromosomal aberrations.10 30 Further, not all workers exposed to VCM develop microvascular abnormalities, suggestive of an underlying genetic susceptibility (polymorphism of glutathione S-transferase).5 11 A finding that female VCM-exposed workers were more susceptible than males to the risk of increased chromosome damage also reinforced the genetic susceptibility theory.30

Comparison with other studies

After 50 years of age, minor dystrophies could alter the readability and interpretation of capillaroscopic analyses.31 Nevertheless, we controlled this parameter by matching the exposed group and the controls on age and we conducted a double-blind analysis by two experienced readers. Moreover, capillaroscopic abnormalities among workers exposed to VCM in the present study were not influenced by age.13

VCM has been suspected to cause respiratory and circulatory diseases.32 However, the similar frequencies of these diseases in both groups do not support this hypothesis.

Diabetes mellitus,16–21 high blood pressure,18 33–35 dyslipidaemia34 or some comorbidities/medications22 could interfere with microcirculation. Diabetes mellitus was an exclusion criterion and thus could not interfere with our results. Perhaps due to the low numbers of participants, our results failed to support previous findings of compromised microcirculation in participants treated for arterial hypertension.18 33–35 The trend for increased capillary length observed in our participants treated with lipid-lowering drugs could be a response to increased peripheral vascular resistance, in order to maintain their function of metabolic exchange.35 Similarly, smoking could induce a decrease in tissue perfusion,36 and dystrophia.37 We did not observe differences between smokers and non-smokers, with the exception of a trend for abnormal microcirculation among smokers exposed to VCM. The potential of a synergistic effect of tobacco and VCM-exposure warrants further investigations. It should be noted that VCM exposure in the current study was more strongly associated with compromised microcirculation than high blood pressure, dyslipidaemia and smoking.

Previous research into the links between systemic sclerosis and VCM exposure is limited by a single case design38 and a somewhat dated analyses of a population exposed to solvents.39 The broader use of a term such as solvents is less specific than the VCM exposure carefully isolated for investigation in the present study.

A higher prevalence of symptoms of Raynaud has been established in workers with VCM exposure,32 up to one-third of the exposed workers.13 The comparison between studies with different selection criteria and different sample sizes is difficult. There is also the possibility of selection bias in non-randomised recruitment. Within these limitations, our results support previous data, and extend knowledge by demonstrating that the prevalence of symptoms of Raynaud remained higher at least 15 years following VCM exposure. Furthermore, in the current study, all the participants who suffered from symptoms of Raynaud had never taken medications or suffered from other diseases conducive to Raynaud.

Unanswered questions

Although symptoms of Raynaud are statistically associated with VCM exposure, we could not report a link with capillaroscopic modifications. The pathophysiology of Raynaud’s phenomenon remains unknown. There seems to be primary or secondary vascular failure influenced by a hereditary factor.40 Decreased perfusion pressure could be secondary to systemic hypotension or be caused by proximal arterial occlusion, influenced by many factors; both vascular and intra vascular, neural, environmental or hereditary.41 Angiography of the hands of patients exposed to VCM showed occlusions, stenosis and narrowing of the distal arteries with the development of collateral circulation.42 Lack of statistical power in our study could contribute to the lack of relationship between the capillaroscopic changes and symptoms of Raynaud.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study presents some major strengths: a rigorous selection criteria of exclusively VCM-exposed participants avoided confounding factors, well-matched controls, a double blind analyses, sufficient number of participants to detect the capillaroscopic differences between groups, the focus on retired workers at least 15 years after the end of occupational VCM exposure. The attendance rate of 30% (53 of 179 individuals exclusively exposed to VCM at work agreed to participate in our study) seems very high compared with other studies,43–47 taking into account their age (75 years), distance from the location of the medical examination (averaging approximately 80 km), and that no financial compensation was offered.

There are limitations to this study. The cross-sectional design has limitations; however, proof of concept was important and achieved (with a possibility of longitudinal follow-up). Differences in some but not all capillary outcomes may be explained by a lack of statistical power. The results are insufficient to propose guidelines for all workers exposed to VCM. More accurate quantifiable measures of VCM exposure are not available; however, for the purpose of this study, we used industry established lists of exposure legally required in France. The pathophysiology of Raynaud after VCM exposure remains unclear. A further limitation may lie in the fact that most of the retired workers exposed to VCM were from the same enterprise; thus, potentially more at-risk manufacturing processes remained undetected. Gender specificity may warrant future studies.

Conclusion

Although VCM exposure was already known to affect microcirculation, our study demonstrated the potential for residual long-term abnormalities following an average of 15 years’ retirement, with a time exposure response. Symptoms of Raynaud, although statistically associated with exposure, were not associated with capillaroscopic modifications; its origin remains to be determined. Future research could focus on other chemical products that have a similar structure than VCM and more extensive research on the type of occupations at risk of VCM exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr George Mnatzaganian for help with statistics (Faculty of Health Sciences, Australian Catholic University, Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia, email: George.Mnatzaganian@acu.edu.au). They also want to acknowledge the ‘Association of the sick from chemicals’ (Association des Malades de la Chimie), 15 Av Albert Poncet 03410 Domerat, France, which helped us recruit the retired workers from VCM exposure.

Footnotes

Contributors: VL has participated as an MD student and principal investigator. FD and AC obtained research funding and generated the intellectual development of the study. FD knew the potential exposed workers to VCM. VL, FD, AC and SH contributed to the conception of the protocol. VL, FD and SH conducted the data analysis. VL, FD, MT contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. VL recruited all participants and performed all the capillaroscopies. VL and MT completed the double blind analyses of capillaroscopy. FD, AC, VL, GN and MT revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The Occupational Medicine department of CHU G. Montpied, Clermont-Ferrand, France funded this study. No other funding source had a role in the design, conduct or reporting of the study.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the human ethics committees of the Clermont-Ferrand University Hospital, France.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Allsopp M, Giovanni G. Poly(vinyl chloride) ullmann's encyclopedia of industrial chemistry. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontana L, Baietto M, Becker F, et al. Clinical and capillaroscopic study of Raynaud's phenomenon in retired patients previously exposed to vinyl chloride monomer. J Mal Vasc 1995;20:268–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veltman G, Lange CE, Juhe S, et al. Clinical manifestations and course of vinyl chloride disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1975;246:6–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris DK, Adams WG. Acro-osteolysis occurring in men engaged in the polymerization of vinyl chloride. BMJ 1967;3:712–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontana L, Marion MJ, Ughetto S, et al. Glutathione S-transferase M1 and GST T1 genetic polymorphisms and Raynaud's phenomenon in French vinyl chloride monomer-exposed workers. J Hum Genet 2006;51:879–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preston BJ, Jones KL, Grainger RG. Clinical aspects of vinyl chloride disease: acro-osteolysis. Proc R Soc Med 1976;69:284–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RH, McCormick WE, Tatum CF, et al. Occupational acroosteolysis. Report of 31 cases. JAMA 1967;201:577–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dragani TA, Zocchetti C. Occupational exposure to vinyl chloride and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Causes Control 2008;19:1193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mundt KA, Dell LD, Austin RP, et al. Historical cohort study of 10 109 men in the North American vinyl chloride industry, 1942–72: update of cancer mortality to 31 December 1995. Occup Environ Med 2000;57:774–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar AK, Balachandar V, Arun M, et al. A comprehensive analysis of plausible genotoxic covariates among workers of a polyvinyl chloride plant exposed to vinyl chloride monomer. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2013;64:652–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji F, Zhu S, Sun P, et al. Relationship between genetic polymorphisms of phase I and phase II metabolizing enzymes and DNA damage of workers exposed to vinyl chloride monomer. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2009;38:7–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langauer-Lewowicka H. Nailfolds capillary abnormalities in polyvinyl chloride production workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1983;51:337–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maricq HR, Darke CS, Archibald RM, et al. In vivo observations of skin capillaries in workers exposed to vinyl chloride. An English-American comparison. Br J Ind Med 1978;35:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maricq HR, Johnson MN, Whetstone CL, et al. Capillary abnormalities in polyvinyl chloride production workers. Examination by in vivo microscopy. JAMA 1976;236:1368–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kowal-Bielecka O, Bielecki M, Kowal K. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of systemic sclerosis. Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej 2013;123:51–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pazos-Moura CC, Moura EG, Bouskela E, et al. Nailfold capillaroscopy in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: blood flow velocity during rest and post-occlusive reactive hyperaemia. Clin Physiol 1990;10:451–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iabichella ML, Mariotti R, Nuti M, et al. Site specificity of biomicroscopic pattern in diabetic patients. Minerva Cardioangiol 1999;47:619–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambova SN, Muller-Ladner U. The specificity of capillaroscopic pattern in connective autoimmune diseases. A comparison with microvascular changes in diseases of social importance: arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Mod Rheumatol 2009;19:600–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vayssairat M, Le Devehat C. [Critical analysis of vascular explorations in diabetic complications]. J Mal Vasc 2001;26:122–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer MF, Pfohl M, Schatz H. [Assessment of diabetic alterations of microcirculation by means of capillaroscopy and laser-Doppler anemometry]. Med Klin (Munich) 2001;96:71–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang CH, Tsai RK, Wu WC, et al. Use of dynamic capillaroscopy for studying cutaneous microcirculation in patients with diabetes mellitus. Microvasc Res 1997;53:121–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallucci F, Russo R, Buono R, et al. Indications and results of videocapillaroscopy in clinical practice. Adv Med Sci 2008;53:149–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hern S, Mortimer PS. Visualization of dermal blood vessels—capillaroscopy. Clin Exp Dermatol 1999;24:473–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingegnoli F, Gualtierotti R, Lubatti C, et al. Feasibility of different capillaroscopic measures for identifying nailfold microvascular alterations. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2009;38:289–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kabasakal Y, Elvins DM, Ring EF, et al. Quantitative nailfold capillaroscopy findings in a population with connective tissue disease and in normal healthy controls. Ann Rheum Dis 1996;55:507–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhakuni DS, Vasdev V, Garg MK, et al. Nailfold capillaroscopy by digital microscope in an Indian population with systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis 2012;15:95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cutolo M, Pizzorni C, Secchi ME, et al. Capillaroscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2008;22:1093–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jouanny P, Schmidt C, Feldmann L, et al. Focus on a quick reading of nailfold capillaroscopy. J Mal Vasc 1994;19:206–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Przybylowski J, Podolecki A, Laks L, et al. [Health status of workers in polyvinyl chloride processing plants. I. Evaluation of occupational exposure. Subjective and capillaroscopy studies. Conduction velocity in the motor nerves]. Med Pr 1983;34:385–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiao J, Feng NN, Li Y, et al. Estimation of a safe level for occupational exposure to vinyl chloride using a benchmark dose method in central China. J Occup Health 2012;54:263–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpentier PH. New techniques for clinical assessment of the peripheral microcirculation. Drugs 1999;59:17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laplanche A, Clavel F, Contassot JC, et al. Exposure to vinyl chloride monomer: report on a cohort study. Br J Ind Med 1987;44:711–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prasad A, Dunnill GS, Mortimer PS, et al. Capillary rarefaction in the forearm skin in essential hypertension. J Hypertens 1995;13:265–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonacci E, Santacroce N, D'Amico N, et al. Nail-fold capillaroscopy in the study of microcirculation in elderly hypertensive patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1996;22(Suppl 1):79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antonios TF, Singer DR, Markandu ND, et al. Structural skin capillary rarefaction in essential hypertension. Hypertension 1999;33:998–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehr HA. Microcirculatory dysfunction induced by cigarette smoking. Microcirculation 2000;7:367–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lova RM, Miniati B, Macchi C, et al. Morphologic changes in the microcirculation induced by chronic smoking habit: a videocapillaroscopic study on the human labial mucosa. Am Heart J 2002;143:658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Betta A, Tommasini M, Bovenzi M, et al. [Scleroderma and occupational factors: a case-control study and analysis of literature]. Med Lav 1994;85:496–506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ostlere LS, Harris D, Buckley C, et al. Atypical systemic sclerosis following exposure to vinyl chloride monomer. A case report and review of the cutaneous aspects of vinyl chloride disease. Clin Exp Dermatol 1992;17:208–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Block JA, Sequeira W. Raynaud's phenomenon. Lancet 2001;357:2042–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herrick AL. The pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of Raynaud phenomenon. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8:469–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koischwitz D, Marsteller HJ, Lackner K, et al. [Changes in the arteries in the hand and fingers due to vinyl chloride exposure (author's transl)]. Rofo 1980;132:62–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dutheil F, Kelly C, Biat I, et al. [Relation between the level of knowledge and the rate of vaccination against the flu virus among the staff of the Clermont-Ferrand University hospital]. Med Mal Infect 2008;38:586–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiew M, Weber MF, Egger S, et al. A cross-sectional exploration of smoking status and social interaction in a large population-based Australian cohort. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penfornis A, San-Galli F, Cimino L, et al. Current insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: results of the ADHOC survey in France. Diabetes Metab 2011;37:440–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heinavaara S, Tokola K, Kurttio P, et al. Validation of exposure assessment and assessment of recruitment methods for a prospective cohort study of mobile phone users (COSMOS) in Finland: a pilot study. Environ Health 2011;10:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eriksen L, Gronbaek M, Helge JW, et al. The Danish Health Examination Survey 2007–2008 (DANHES 2007-2008). Scand J Public Health 2011;39:203–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.