Abstract

The study of the morphological defects unique to interspecific hybrids can reveal which developmental pathways have diverged between species. Drosophila melanogaster and D. santomea diverged more than 10 million years ago, and when crossed produce sterile adult females. Adult hybrid males are absent from all interspecific crosses. We aimed to determine the fate of these hybrid males. To do so, we tracked the development of hybrid females and males using classic genetic markers and techniques. We found that hybrid males die predominantly as embryos with severe segment-specification defects while a large proportion of hybrid females embryos hatch and survive to adulthood. In particular, we show that most male embryos show a characteristic abdominal ablation phenotype, not observed in either parental species. This suggests that sex-specific embryonic developmental defects eliminate hybrid males in this interspecific cross. The study of the developmental abnormalities that occur in hybrids can lead to the understanding of cryptic molecular divergence between species sharing a conserved body plan.

Keywords: Drosophila, embryonic lethality, Haldane's rule, postzygotic isolation

Introduction

The range of developmental and morphological defects seen in interspecific hybrids spans from complete hybrid lethality to a mild perturbation of adult morphology (reviewed in Coyne and Orr 2004). If any one of these defects has a fitness effect and/or precludes the possibility of gene flow between the parental species, then they will also contribute to reproductive isolation. Detailed study of the developmental defects unique to interspecific hybrids can reveal which traits can serve to keep species apart though postzygotic isolation. While the developmental defects of interspecific hybrids are widespread taxonomically (Coyne and Orr 2004), the specific genetic mechanisms involved are understood in only a few notable examples (reviewed in Nosil and Schluter 2011; Maheshwari and Barbash 2011). Nonetheless, postzygotic isolation follows several patterns that can be generalized to a wide variety of taxonomic groups.

A common pattern of postzygotic isolation is Haldane's rule (Haldane 1922; Orr 1997): in hybridizing species with sex chromosomes, if one sex suffers hybrid breakdown it is usually the heterogametic sex. In Drosophila and mammals, it is predominantly the male XY hybrids that suffer the most pronounced inviability or sterility, while in Lepidopterans and birds, the ZW female hybrids are more likely to be unfit (Orr 1997; Presgraves and Orr 1998; Price 2008). One simple explanation of this pattern is that the majority of genes involved in hybrid inviability are recessive. The hemizygosity of the sex chromosomes in the heterogametic sex, then, allows for full expression of the alleles regardless of their dominance, and their deleterious fitness effects will be more pronounced than in the homogametic individuals (Original formulation in Muller 1940; corrected in Orr 1993a, b; Orr and Turelli 1996).

Instances of Haldane's rule are widespread, however, detailed characterization of the deleterious phenotypes is rare and the genetic basis of heterogametic hybrid inviability has been defined only in select cases. This is due in part to the difficulties of studying the causative genetic differences in interspecific hybrids, especially those resulting in inviability. Nonetheless, a series of efforts have been successful in identifying the genomic regions underlying male lethality and sterility in interspecific Drosophila hybrids and many of the specific genes involved (Sawamura et al. 1993a, b; Hutter and Ashburner 1987; Sawamura and Yamamoto 1997; Presgraves et al. 2003; Phadnis and Orr 2009; Tang and Presgraves 2009 among others).

The most success in identifying the developmental defects underlying hybrid inviability has been with Drosophila. One well-studied example is the hybrids from the cross of D. melanogaster females and males from the D. simulans species group (D. simulans, D. sechellia, and D. mauritiana, henceforth referred as the sim species group). Even though these two groups of species (D. melanogaster and the sim species group) diverged approximately 3–5 million years ago (Tamura et al. 2004), the cross produces sterile hybrid adult females. The hybrid male larvae grow slowly (Sanchez and Dübendorfer 1983; Bolkan et al. 2007), cannot molt into pupae and eventually die due to profound mitotic defects (Orr et al. 1997; Barbash et al. 2000; Barbash et al. 2003; Bolkan et al. 2007). Although the causative molecular defects in cell division, the arrest in the G phase of mitosis, and consequent larval lethality are seen in all the three kinds of hybrids between D. melanogaster females and the males from the sim group of species, the precise developmental consequences of these mitotic defects differ between hybrids. In the D. melanogaster/D. simulans cross, male larvae usually lack imaginal discs (Seiler and Nothiger 1974; Sanchez and Dübendorfer 1983; Orr et al. 1997). On the other hand, the D. melanogaster/D. mauritiana cross produces hybrid male larvae that possess imaginal discs, however, a substantial fraction of discs are underdeveloped and threadlike (Sanchez and Dübendorfer 1983; Orr et al. 1997).

With the exception of these examples in the simulans group, very little is known about the developmental processes disrupted in hybrid males of other interspecific crosses between Drosophila. For example, it is known that more divergent species (D. simulans × D. teissieri, D. melanogaster × D. santomea) can produce hybrid progeny but in all cases, the progeny is exclusively sterile females (Orr 1993a, b; Matute et al. 2010). It has yet to be determined whether male lethality in crosses between these more divergent species arises from developmental defects similar to those in the D. melanogaster/sim group of interspecific hybrids. Here, we examine the developmental stage of male hybrid lethality in crosses of D. melanogaster and D. santomea (Fig. 1). These two species diverged more than 10 million years ago (Tamura et al. 2004) but recent work has reported that crosses between D. melanogaster females and D. santomea males produce sterile females (Matute et al. 2010). While the genetic architecture of female inviability in these hybrids has been assessed, male hybrid lethality has not been examined in detail. To date, the D. yakuba lineage (D. yakuba, D. teissieri, and D. santomea) and the melanogaster lineage (D. melanogaster and the sim group of species) remain the most divergent clades in Drosophila shown to hybridize (Orr 1993a, b; Matute et al. 2010). The study of developmental defects in hybrids between these divergent clades may help uncover the cryptic molecular variation and the evolution of developmental differences between species with conserved patterning systems and body plans. In this initial approach, we used classic developmental genetics techniques to distinguish and track the development of D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrid females and males. We found that hybrid males die predominantly during embryogenesis manifesting severe segment-specification defects, while hybrid females usually hatch and survive to adulthood.

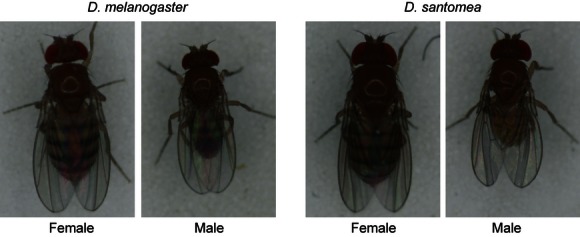

Figure 1.

Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila santomea. D. melanogaster is a cosmopolitan species found in every continent (but Antarctica). D. santomea, on the other hand, is an endemic species whose geographic range is restricted to the rainforests in the mountains of São Tomé.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks

All transgenic D. melanogaster lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center at Indiana University (http://flystocks.bio.indiana.edu/) and are listed in Table S1. D. santomea SYN2005 is an outbred line constructed by combining isofemale stocks and kept in large numbers since its initiation (Matute et al. 2009; Matute and Coyne 2010). All the other stocks of D. santomea were collected in 2009 by DRM and were established as isofemale lines (i.e., progeny from a single inseminated female has been perpetuated in laboratory conditions).

Crosses

All flies were raised on standard cornmeal/molasses medium in pint size bottles or 8-dram plastic vials. Virgins females were collected by lightly gassing recently emerged flies (less than 8 h after eclosion) with CO2 and separating females from males. For embryonic lethality counts and cuticular phenotypes, interspecific crosses were started in vials with at least twenty >3-day-old females and at least 40 D. santomea males. (Intraspecific crosses were housed in plastic cups directly after virgin females and males were mixed.) The crosses were incubated in a light-cycling incubator at a constant temperature (25°C) and relative humidity (60%) simulating days of 14 h of light and 10 h of darkness. In all F1 hybrids, the identity of the mother is shown first (e.g., mel/san is the progeny of D. melanogaster females and D. santomea males).

Insemination rate

To directly measure the fertilization rates in hybrid crosses, we combined at least 100 D. melanogaster females and 200 D. santomea males and housed them in the same vials for 4 days. After that time, females were dissected and the spermatheca and oviducts were mounted in Ringer's Solution at 4°C to check for the presence of sperm. If we observed any sperm, even weak or scarce, in the dissected female tract, we categorized that female as mated. The frequency of insemination was established for 32 isofemale lines. Three replicates of independent crosses were measured per isofemale line.

Embryo collection

After 2–3 days of crossing, both male and female flies were transferred to a collection cup with a standard yeasted apple juice plate to allow oviposition. In all crosses, embryonic lethality was quantified by counting the number of hatched and unhatched fertilized eggs of an overnight deposition after 24 h of aging at 25°C. Briefly, viability was scored as the number of empty egg cases, while lethality was scored as unhatched eggs with discernible larval structures. We follow the same procedure to quantify lethality rates for intraspecific crosses. We quantified lethality for at least three replicates per cross.

For visualization of cuticles of unhatched embryos, we first dechorinated and devitellenized unhatched embryos manually. These embryos were transferred to an emulsion of Acetic acid:Glycerol (3:1) to digest all soft tissues. Digested cuticles were then mounted in Hoyer's Media:85% Lactic Acid (1:1). All slides were then moved overnight to a baking oven (75°C) to speed clearing. Embryos were then imaged and scored for cuticular defects.

For the distinction between male and female larval cuticles, we crossed y,w; P{Sxl-Pe-EGFP.G} (Thompson et al. 2004) D. melanogaster females to D. santomea males. The y,w; Sxl:GFP females were generated from stocks from Bloomington stock center (Stock number: 24105; w*; P{Sxl-Pe-EGFP.G}G78b).

Crosses involving y,w; Sxl:GFP females were allowed to proceed for 3–4 days in a cornmeal 8-dram vial as described above and then transferred to an apple juice plate. After an overnight deposition, embryos were sorted by GFP expression under a dissecting fluorescent microscope after 6 h of incubation at 25°C. The SXL::GFP distinction was additionally checked by observing the color of the mouth parts of hatched larvae or cuticles of dead embryos, as the lack of pigment in the larval mouthparts indicated the presence of a single yellow marked X-chromosome from D. melanogaster. The yellow allele from D. santomea rescues the D. melanogaster yellow allele's mouthpart phenotype, therefore all the dead embryos or larvae with wild-type mouthparts were considered females.

We also used the lack of pigmentation of yellow mouthparts to sex-type the cuticles of those embryos which failed to hatch. We then classified the severity of Anterior–Posterior patterning defects present in each sex with the following metric: The absence of denticulate bands beyond abdominal five, was scored as an “ablation” phenotype or A5-. If cuticle was present, but without discernible denticle bands, embryos were classified as intermediate. Finally, if some amount of denticulate matter, however, slight, was discernible posterior to abdominal segment 5, then the cuticle was scored as A5+.

Larval and pupal lethality

We collected 50 L1 larvae within 12 h after egg hatching and transferred them to an 8-dram cornmeal plastic vial. Vials were checked daily and once L2 larvae were observed, we damped the food with a 0.5% propionic acid solution and added a pupation substrate to the vial (Mierly Clark, Kimwipes Delicate Task, Roswell, GA). After a few days (seven on average), the number of pupal cases on the paper was counted. (If larvae pupated on the food media, the vial was not taken into account.) The ratio of pupae to L1 larvae was used as a proxy of larval viability. For each vial, we also quantified how many adults hatched and calculated a pupal viability index (i.e., ratio of adult/pupal cases).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were done with R (R Development Core Team 2005). In three cases (B1300.17, C1350.14, and C1350.15), we were able to collect two replicates for the estimates of hybrid viability. As all the other lines were represented by three replicates, we estimated missing values by calculating the average of the available replicates. Fertilization rate, pure species estimates of lethality, larval and pupal survival rates of hybrid individuals significantly deviated from normality (even after data transformation) and were analyzed using a Kruskal–Wallis test. Lethality rates in hybrid crosses were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA (residuals of the linear model followed a normal distribution; Shapiro–Wilk normality test: W = 0.982, P = 0.319).

Results

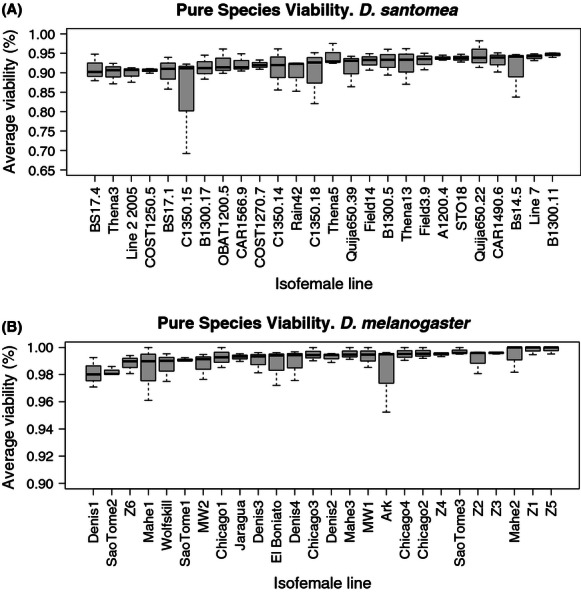

To study the nature of postzygotic isolation in mel/san hybrids, we first analyzed the rates of embryonic lethality in pure species isofemale lines of D. santomea and D. melanogaster. When measured at 24°C, the lethality rates are lower than 15% in all D. santomea isofemale lines and lower than 5% in all the measured D. melanogaster isofemale lines (Fig. 2). We detected no significant heterogeneity within the species (D. santomea: Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 20.619, df = 25, P = 0.714; D. melanogaster: Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 27.242, df = 24, P = 0.293), but there were significant differences between species (Mean viability of D. melanogaster embryos: 99.12%; Mean viability of D. santomea embryos: 91.81%; Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction data: W = 6058, P < 2.2 × 10−16). Additionally, the majority of the individuals from the two parental species show no major developmental defects and both sexes are present at roughly the same frequencies (Fig. 2, Table S2) indicating that no sex-specific lethality was detectable in the parental species. When D. melanogaster females are crossed to D. santomea males, however, only hybrid females are observed as adults, indicating complete sex-specific lethality in these hybrid crosses. We then sought to determine the efficacy of mating and the developmental defects that lead to hybrid male inviability in this highly divergent cross of Drosophila species.

Figure 2.

Pure species Viability. Viability rates in pure species in Drosophila santomea isofemale lines (A) and D. melanogaster (B). For each species, we analyzed 26 isofemale lines (three replicates per line) and found no heterogeneity in viability levels. Isofemale lines were ordinated by their median viability (thick line in the each box). The bottom edge of the box is the 25th percentile of the data and the top edge of the box is the 75th percentile of the data.

First, we measured the insemination rates when D. melanogaster females from the ArkLa outbred line (Matute et al. 2010) were mated to males of different D. santomea isofemale lines (n = 32 lines, three replicates per line). The proportion of D. melanogaster females that accepted D. santomea males was assessed by the presence or absence of sperm in their reproductive tract after 4 days of being housed together. We detected marginal hetero-geneity in the proportion of inseminated females (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 44.047, df = 31, P = 0.061) suggesting that the level of behavioral isolation of D. melanogaster ArkLa females toward males of all lines of D. santomea is high with little variation (average proportion of inseminated females per cross: 2.55%, SEM = 2.86 × 10−3).

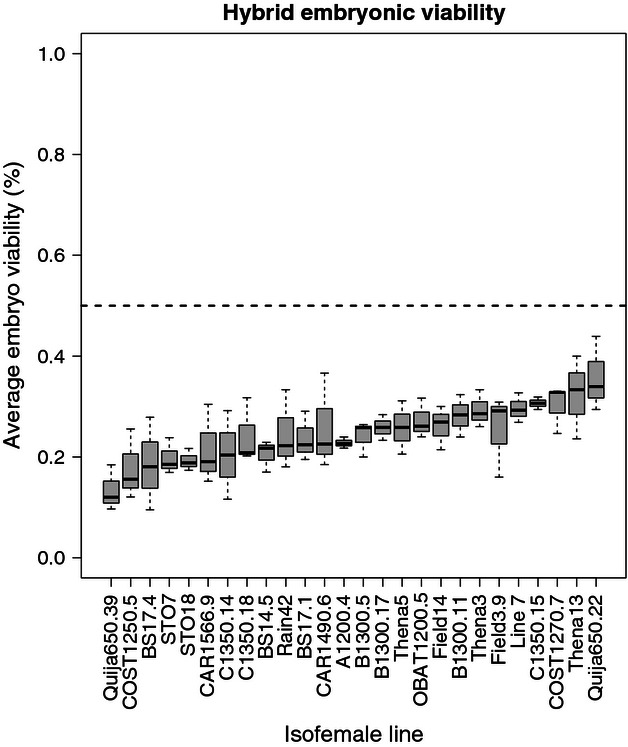

We then measured the rate of embryonic lethality in F1 hybrids between D. melanogaster and D. santomea by crossing D. melanogaster ArkLa females to males of 26 lines of D. santomea. On average, 75% of the hybrid embryos from these crosses were inviable (25% were viable, Fig. 3), although there was significant heterogeneity in viability caused by the effect of the parental line (one-way ANOVA: F25,52 = 2.266, P = 6.48 × 10−3). Despite this heterogeneity, the embryonic lethality of hybrid crosses between D. melanogaster and D. santomea lines was significantly higher than that observed in either of the two pure species (Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction; W > 6084, P < 2 × 10−16).

Figure 3.

Hybrid embryonic lethality in different mel/san crosses. We measured hybrid embryonic viability for different Drosophila santomea lines when crossed to D. melanogaster ArkLa females. Isofemale lines were ordinated by their median viability. The dotted line shows the expectation of full male embryonic lethality and no female embryonic lethality. The bottom edge of the box is the 25th percentile of the data and the top edge of the box is the 75th percentile of the data.

As over 50% of the hybrid embryos did not hatch into L1 larvae in all crosses, we hypothesized that the majority of those embryos that failed to hatch were the hybrid male progeny. To determine whether there was any sex-biased lethality during hybrid embryogenesis, we repeated the crosses with 11 D. santomea lines (10 isofemale lines and D. santomea SYN2005). Using two different sex-specific markers, a SXL:GFP reporter (Thompson et al. 2004) which is detectable only in females after 4–6 h of embryogenesis and yellow which manifests as a recessive marker in the larval mouth hooks, we assessed the sex-specific embryonic lethality rates in the F1 hybrids. We found that the vast majority of SXL::GFP- (hybrid males) embryos failed to hatch, regardless of the D. santomea line (Table 1). Even though a few hybrid male embryos hatched into a L1 larvae, however, L2 male larvae were never observed. These data strongly indicate that the F1 male hybrid embryos of D. melanogaster and D. santomea are rendered inviable during the course of embryogenesis.

Table 1.

The relative frequency of dead/live embryos in each sex in Drosophila melanogaster/D. santomea hybrids measured using sxl::GFP and yellow as sex-specific markers. All lines showed a uniform male embryonic lethality (close to 100%) but there was significant variation in the degree of female inviability

| GFP (+) | GFP (−) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line | Dead | Alive | Dead | Alive | Surviving females (%) | Surviving males (%) |

| STO7 | 46 | 73 | 114 | 1 | 61.344 | 0.870 |

| Quija650.39 | 51 | 96 | 154 | 0 | 65.306 | 0 |

| COST1250.5 | 36 | 104 | 134 | 0 | 74.286 | 0 |

| A1200.4 | 44 | 140 | 174 | 1 | 76.087 | 0.571 |

| Field14 | 20 | 73 | 83 | 0 | 78.495 | 0 |

| Bs14.5 | 30 | 103 | 124 | 1 | 77.444 | 0.8 |

| SYN2005 | 26 | 90 | 100 | 3 | 77.586 | 2.913 |

| Thena13 | 19 | 74 | 94 | 0 | 79.570 | 0 |

| Thena3 | 18 | 92 | 102 | 1 | 83.636 | 0.971 |

| COST1270.7 | 12 | 67 | 75 | 1 | 84.810 | 1.316 |

| Quija650.22 | 5 | 58 | 59 | 2 | 92.0635 | 3.279 |

In contrast to the nearly complete male embryonic lethality, in all crosses a significant proportion (>50%) of the hybrid females survived embryogenesis (Table 1). The sex-specific viability counts indicate that there was significant variation in the frequency of viable females (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 26.028, df = 10, P = 3.70 × 10−3) but not of male lethality rates (male larvae were observed only in nine out of the 33 replicates). The significant differences in female lethality suggest that there are genetic variants in the paternal genome with differential effects on the embryonic viability of hybrid females.

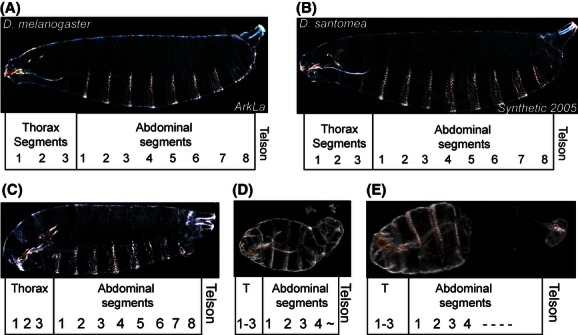

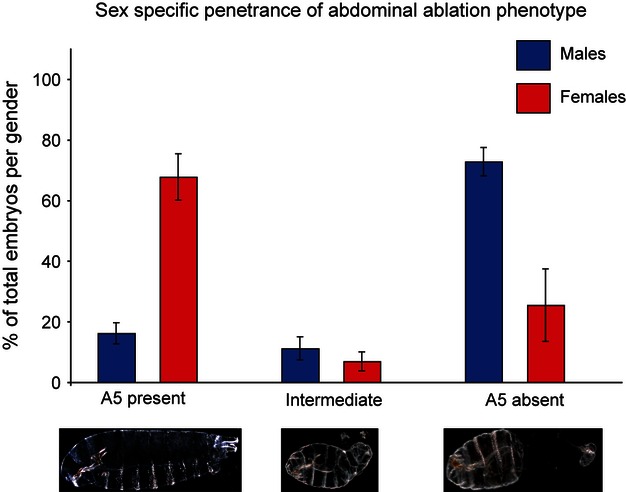

To determine whether male hybrid embryos fail to hatch due to a gross sex-specific patterning defect during embryogenesis, we then examined the cuticles of inviable embryos. The male embryos that failed to hatch had a higher prevalence of an abdominal ablation phenotype of the larval cuticle (Figs. 4–5), while the majority of the inviable embryos of both sexes have head involution defects (Fig. S1). Abdominal defects were more frequent in hybrid males than in hybrid females (Two-sided Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data, in all three assayed lines P < 0.010, Fig. 5). We conclude, therefore that, at high frequency, male hybrids carrying the D. melanogaster X-chromosome are unable to pattern the posterior abdominal segments (A5-A7). As no known mutant within D. melanogaster recapitulates the developmental defect we observed in these hybrid males, we believe this is a functional antimorphism unique to the hybrid embryo context. This developmental defect is rescued in some hybrid females, possibly due to the presence of the D. santomea X-chromosome, as ∼70% of dead D. melanogaster/D. santomea SYN2005 female hybrids embryos show intact posterior segments.

Figure 4.

Typical cuticles manifesting a “complete” “intermediate” or “ablation” phenotype. Darkfield micrographs of wild-type pure species larval cuticles of Drosophila melanogaster (A) and D. santomea (B) with the major thoracic and abdominal segments mapped below. (C–D) Hybrid larval cuticles typifying the three major categories of defects in those embryos that failed to hatch.

Figure 5.

The ablation phenotype is disproportionally seen in hybrid mel/san males. Three kinds of developmental defects observed in mel/san hybrids ordinated by increasing severity from right to left. Approximately 67% of hybrid male cuticles manifest abdominal ablations in segments A5 to A7 while >30% females show the same developmental defect. Red bars: females; Blue bars: males. Error bars show the SEM across isofemale lines (see text for details).

We followed the development of the female hybrids that survive embryogenesis during their larval and pupal development to establish whether there was any hybrid inviability during these later developmental stages. Table 2 shows the overall high survival rate of hybrid females during larval and pupal stages. These results suggest that the majority of mechanisms that cause hybrid incompatibility in both males and females are active primarily during embryogenesis. After the embryonic stage, hybrid females have comparable survival rates to the parental species, with little heterogeneity between lines; Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test, Larval viability: Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 19.577, df = 25, P = 0.769; Pupal viability: Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 34.632, df = 25, P = 0.095). Thus, genetic variation in the D. santomea population gives rise to differential penetrance of embryonic patterning defects, but has little effect on development during later stages.

Table 2.

Lethality rates as larvae and pupae in Drosophila melanogaster/D. santomea hybrid females

| Line | Larvae average survival rate (%) | Pupae average survival rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A1200.4 | 81.610 | 85.556 |

| B1300.11 | 87.418 | 87.209 |

| B1300.17 | 84.655 | 82.857 |

| B1300.5 | 89.404 | 89.150 |

| Bs14.5 | 93.801 | 82.621 |

| BS17.1 | 86.745 | 93.111 |

| BS17.4 | 93.927 | 82.190 |

| C1350.14 | 87.500 | 85.714 |

| C1350.15 | 77.531 | 93.167 |

| C1350.18 | 80.404 | 90.996 |

| CAR1490.6 | 77.831 | 87.443 |

| CAR1566.9 | 88.213 | 86.825 |

| COST1250.5 | 73.948 | 69.798 |

| COST1270.7 | 86.705 | 85.357 |

| Field14 | 79.048 | 82.183 |

| Field3.9 | 94.435 | 85.197 |

| STO7 | 74.242 | 66.468 |

| Line 7 | 89.167 | 93.386 |

| OBAT1200.5 | 87.880 | 91.414 |

| Quija650.22 | 90.741 | 95.556 |

| Quija650.39 | 85.450 | 87.118 |

| Rain42 | 91.538 | 88.384 |

| STO18 | 81.197 | 72.639 |

| Thena13 | 92.726 | 85.051 |

| Thena3 | 84.658 | 94.192 |

| Thena5 | 93.430 | 85.859 |

Discussion

Previous reports have conclusively demonstrated that in D. melanogaster/sim-group hybrids, a mitotic effect leads to male lethality during larvae or prepupae stages (Orr et al. 1997; Bolkan et al. 2007). In this report, we demonstrate that there are distinct causes for hybrid male lethality in other Drosophila hybrids. Our data show that in D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrid males, the defects leading to hybrid inviability arise much earlier in development than in D. melanogaster/sim-group hybrid males and cause hybrid lethality in embryonic stages. The phenotype observed in the hybrid males is not observed in cuticles of either of the two parental species, which suggests the existence of negative epistasis in hybrids, as alleles that normally function in pure species cause severe developmental defects, leading to hybrid male lethality.

D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrid males carry a full set of autosomes of each species, the cytoplasmic elements, mitochondrial genome and maternally deposited genes and the X-chromosome from D. melanogaster. The hybrid females carry the same genetic elements but also carry the X-chromosome from D. santomea. Thus, several nonexclusive genetic mechanisms could lead to the inviability of hybrid male embryos in D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrids. First, it is possible that a recessive antimorphic allele on the D. melanogaster X-chromosome interacts with alleles on the D. santomea autosomes to cause hybrid male lethality. These effects would not be observed in the hybrid females because the X-chromosome from D. santomea masks any recessive effects. Second, it is also possible that a semidominant allele on the D. melanogaster X-chromosome causes hybrid inviability in both hybrid males and females, but the presence of a homologous D. santomea allele ameliorates the developmental issues in hybrid females, allowing for a partial rescue of viability. Third, it is possible that hybrid inviability is caused by negative epistasis between the Y-chromosome from D. santomea and either cytoplasmic elements of D. melanogaster, autosomes from D. melanogaster or both. Finally, there could be a failure in dosage compensation in hybrid males that leads to hybrid inviability. This possibility, however, seems unlikely as, at low but appreciable frequency, female hybrid embryos also manifest patterning defects or ablations specific to abdominal segments 5–7. Furthermore, forward genetic screens failed to identify any role for dosage compensation defects in male inviability of D.melanogaster/D.simulans hybrids (Barbash 2010; this of course, does not directly apply to hybrids between D. melanogaster and D. santomea). This, combined with the variable female viability seen across isofemale lines, suggests that a polygenic epistatic mechanism, and not a failure in dosage compensation, leads to the developmental defects (and subsequent lethality) in mel/san hybrids. Further research will formally test these hypotheses.

This report, however, is not the first instance in which hybrid embryonic lethality has been observed in Drosophila. Presgraves (2003) was able to identify 40 chromosomal regions that lead to hybrid males embryonic lethality. In that case, the nature of the epistatic interactions was between a recessive D. simulans autosomal allele and a recessive D. melanogaster allele in the X-chromosome. In the D. melanogaster/D. santomea hybrids, however, the epistatic interaction must be between an allele in the D. melanogaster X-chromosome and a dominant or semidominant factor (s) on the autosomes of D. santomea. In a second case, the females from the cross D. simulans × D. melanogaster die as embryos. The identity of the causal allele for this lethality has been precisely established: Zhr, a minisatellite in the X-chromosome from D. melanogaster that causes a viability defect by directly inhibiting chromatid separation in hybrids (Ferree and Barbash 2009). A third case of embryonic lethality is observed in the interspecific hybrids between D. montana females to D. texana males. In this cross, only male offspring are produced. The genetic mechanism causing hybrid inviability has been ascribed to an incompatibility between the D. montana ooplasm and the D. texana X-chromosome which causes the lethality of female hybrid embryos before hatching (Kinsey 1967). These last two cases constitute some of the few exceptions to Haldane's rule in Drosophila.

Our results also suggest that hatched female embryos are likely to remain viable through subsequent development, as the rate of larval and pupal lethality is low. This, however, does not mean that these female hybrids are fit. In addition to being sterile, with only empty, rudimentary ovaries these females show extensive abdomen sclerotinization. These phenotypes are also observed in D. melanogaster/sim-group hybrids (Sturtevant 1920). It remains to be determined if the genetic and/or developmental causes for sclerotinization and female sterility are the same in D. melanogaster/D. santomea and D. melanogaster/sim-group hybrid females.

This report also demonstrates that there are differences in female viability contingent on the zygotic genome contributed by the D. santomea isofemale line. These findings are in keeping with the variability of penetrance and dominance of alleles involved in hybrid inviability of D. melanogaster/D. simulans interspecific crosses reported by Gérard and Presgraves (2012), demonstrating the critical effects of genetic background of the maternal line on hybrid phenotypes. Their observations show that hybrid inviability has altered penetrance in different backgrounds, suggestive of multiallelic interactions with alleles not fixed in D. simulans. Our phenotypic analyses of cuticles reveal that some females do die as embryos, indistinguishable from hybrid males, suggesting that the genetic mechanisms that cause male hybrid embryonic lethality are not exclusively sex-specific, whereas its penetrance is. Modifiers of these genetic mechanisms, however, seem to be segregating in the population, as different isofemale lines show varying amounts of female embryonic lethality. The variability seen in our study, together with the work of Gerard and Presgraves serves as a reminder on the importance of taking into account the highly polygenic nature of the epistatic interactions leading to hybrid inviability.

The fact that we are able to produce hybrids with all assayed D. santomea lines demonstrates that the ability of D. santomea to cross with D. melanogaster is not dependent on a particular mutation in a single line and suggests that any D. melanogaster female × D. santomea male cross will produce progeny. We have not, however, succeeded in obtaining progeny from the reciprocal cross (D. santomea females × D. melanogaster males): we have never observed progeny in more than 10,000 crosses of D. santomea females with different lines of D. melanogaster males. Dissection of D. santomea female reproductive tracks in these crosses (n > 50,000 attempted females) revealed no sperm in any female, indicating that sexual isolation is complete between these two species in the set of environmental conditions we are applying. Although we will continue attempting these hybridizations, other approaches might be required to produce D. santomea/D. melanogaster hybrids with D. santomea maternal factors. Sanchez and Santamaria (1997), for example, performed transfers of D. yakuba (and D. teissieri) pole cells into D. melanogaster oskar null mutants and were able to produce hybrid progeny (males and females that carry the cytoplasmic elements of D. yakuba). This approach, however, does not guarantee that we will obtain san/mel hybrids as the genetic architecture of hybrid inviability of yak/mel hybrids may differ from that of san/mel hybrids.

This study demonstrates how the examination of the genetic basis of hybrid inviability between D. melanogaster and D. santomea, two relatively diverged species, can shed light on the genetic architecture of cryptic divergence in genes directly involved in the fundamental aspects of body plan formation in Drosophila.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. F. Przeworski, J. Reinitz, M. Kreitman, J. A. Coyne, and K. L. M. Gordon for scientific discussions and comments at every developmental stage of the manuscript. We also thank the Przeworski and Reintiz lab groups for their helpful comments and R. Fehon for equipment use. Peter Andolfatto and Ana Llopart donated stocks and we are grateful to them. D. R. M. would like to thank the Bioko Biodiversity Protection Program, and the Ministry of Environment, Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe for permission to collect and export specimens for study. J. G. S. and D. R. M. are funded by Chicago Fellowships.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Consistent head involution defects seen in hybrid embryos from different isofemale lines.

Table S1. Stocks used in this study.

Table S2. Sex ratio in D. santomea.

References

- Barbash DA. Genetic testing of the hypothesis that hybrid male lethality results from a failure in dosage compensation. Genetics. 2010;184:313–316. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.108100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbash DA, Roote J, Ashburner M. The Drosophila melanogaster hybrid male rescue gene causes inviability in male and female species hybrids. Genetics. 2000;154:1747–1771. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.4.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbash DA, Siino DF, Tarone AM, Roote J. A rapidly evolving MYB-related protein causes species isolation in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:5302–5307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836927100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolkan BJ, Booker R, Goldberg ML, Barbash DA. Developmental and cell cycle progression defects in Drosophila hybrid males. Genetics. 2007;177:2233–2241. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.079939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree PM, Barbash DA. Species-specific heterochromatin prevents mitotic chromosome segregation to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard PR, Presgraves DC. Abundant genetic variability in Drosophila simulans for hybrid female lethality in interspecific crosses to D. melanogaster. Genet. Res. (Camb.) 2012;94:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0016672312000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane JBS. Sex-ratio and unisexual sterility in hybrid animals. J. Genet. 1922;12:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter P, Ashburner M. Genetic rescue of inviable hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and its sibling species. Nature. 1987;327:331–333. doi: 10.1038/327331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey J. Studies on an embryonic lethal hybrid in Drosophila. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1967;17:405–423. [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari S, Barbash DA. The genetics of hybrid incompatibilities. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011;45:331–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute DR, Coyne JA. Intrinsic reproductive isolation between two sister species of Drosophila. Evolution. 2010;64:903–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute DR, Novak CJ, Coyne JA. Thermal adaptation and extrinsic reproductive isolation in two species of Drosophila. Evolution. 2009;63:583–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute DR, Butler IA, Turissini DA, Coyne JA. A test of the snowball theory for the rate of evolution of hybrid incompatibilities. Science. 2010;329:1518–1521. doi: 10.1126/science.1193440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller HJ. Bearing of the Drosophila work on systematics. In: Hux1ey J, editor. The new systematics. Oxford, U.K: Clarendon Press; 1940. pp. 185–268. [Google Scholar]

- Nosil P, Schluter D. The genes underlying the process of speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011;26:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr HA. A mathematical model of Haldane's rule. Evolution. 1993a;47:1606–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1993.tb02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr HA. Haldane's rule has multiple genetic causes. Nature. 1993b;361:532–533. doi: 10.1038/361532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr HA. Haldane's rule. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1997;28:195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Orr HA, Turelli M. Dominance and Haldane's rule. Genetics. 1996;143:613–616. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.1.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr HA, Madden LD, Coyne JA, Goodwin R, Hawley RS. The developmental genetics of hybrid inviability: a mitotic defect in Drosophila hybrids. Genetics. 1997;145:1031–1040. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadnis N, Orr HA. A single gene causes both male sterility and segregation distortion in Drosophila hybrids. Science. 2009;323:376–378. doi: 10.1126/science.1163934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves DC. A fine-scale genetic analysis of hybrid incompatibilities in Drosophila. Genetics. 2003;163:955–972. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.3.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves DC, Orr HA. Haldane's rule is obeyed in taxa lacking a hemizygous X. Science. 1998;282:952–954. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves DC, Balagopalan L, Abmayr SM, Orr HA. Adaptive evolution drives divergence of a hybrid inviability gene in Drosophila. Nature. 2003;423:715–719. doi: 10.1038/nature01679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TD. Speciation in birds. Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts and Company; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing, reference index version 2.2.1. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2005. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. Available at http://www.R-project.org. (accessed June 6, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez L, Dübendorfer A. Development of imaginal discs from lethal hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila mauritiana. Rouxs Arch. Dev. Biol. 1983;192:48–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00848770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez L, Santamaria P. Reproductive isolation and morphogenetic evolution in Drosophila analyzed by breakage of ethological barriers. Genetics. 1997;147:231–242. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura K, Yamamoto M-T. Characterization of a reproductive isolation gene, zygotic hybrid rescue, of Drosophila melanogaster by using minichromosomes. Heredity. 1997;79:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura K, Taira T, Watanabe TK. Hybrid lethal systems in the Drosophila melanogaster species complex. I. The maternal hybrid rescue (mhr) gene of Drosophila simulans. Genetics. 1993a;133:299–305. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura K, Yamamoto M-T, Watanabe TK. Hybrid lethal systems in the Drosophila melanogaster species complex. II. The Zygotic hybrid rescue (Zhr) gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1993b;133:307–313. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler T, Nothiger R. Somatic cell genetics applied to species hybrids of Drosophila. Experientia. 1974;30:709. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant AH. Genetic studies on Drosophila simulans. I. Introduction. Hybrids with Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1920;5:488–500. doi: 10.1093/genetics/5.5.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, Subramanian S, Kumar S. Temporal patterns of fruit fly (Drosophila) evolution revealed by mutation clocks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:36–44. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S, Presgraves DC. Evolution of the Drosophila nuclear pore complex results in multiple hybrid incompatibilities. Science. 2009;323:779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.1169123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JGP, Schedl P, Pulak R. 2004. Sex-specific GFP-expression in Drosophila embryos and sorting by Copas flow cytometry technique. Presented at the 45th Annual Drosophila Research Conference, Washington, DC, 24–28 March 2004.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.