Abstract

Objective

To determine whether vitamin C administration influences exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB).

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

MEDLINE and Scopus were searched for placebo-controlled trials on vitamin C and EIB. The primary measures of vitamin C effect used in this study were: (1) the arithmetic difference and (2) the relative effect in the postexercise forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) decline between the vitamin C and placebo periods. The relative effect of vitamin C administration on FEV1 was analysed by using linear modelling for two studies that reported full or partial individual-level data. The arithmetic differences and the relative effects were pooled by the inverse variance method. A secondary measure of the vitamin C effect was the difference in the proportion of participants suffering from EIB on the vitamin C and placebo days.

Results

3 placebo-controlled trials that studied the effect of vitamin C on EIB were identified. In all, they had 40 participants. The pooled effect estimate indicated a reduction of 8.4 percentage points (95% CI 4.6 to 12) in the postexercise FEV1 decline when vitamin C was administered before exercise. The pooled relative effect estimate indicated a 48% reduction (95% CI 33% to 64%) in the postexercise FEV1 decline when vitamin C was administered before exercise. One study needed imputations to include it in the meta-analyses, but it also reported that vitamin C decreased the proportion of participants who suffered from EIB by 50 percentage points (95% CI 23 to 68); this comparison did not need data imputations.

Conclusions

Given the safety and low cost of vitamin C, and the positive findings for vitamin C administration in the three EIB studies, it seems reasonable for physically active people to test vitamin C when they have respiratory symptoms such as cough associated with exercise. Further research on the effects of vitamin C on EIB is warranted.

Keywords: Nutrition & Dietetics, Sports Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

Exercise causes airway narrowing in about 10% of the general population and in up to 50% of competitive athletes.

Laboratory studies have indicated that vitamin C may have an alleviating influence on bronchoconstriction.

The aim of this research was to examine whether vitamin C administration influences forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) decline caused by exercise.

Key messages

Vitamin C may alleviate respiratory symptoms caused by exercise.

In future studies, linear modelling should be used to examine the effect of vitamin C on the postexercise FEV1 decline instead of calculating the mean effect of vitamin C on the postexercise FEV1 decline.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The included studies were methodologically satisfactory and their results were consistent and close.

The included studies were small with 40 participants in all.

Introduction

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) is a transient narrowing of the airways that occurs during or after exercise. Usually, a 10% or greater exercise-induced decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) is classified as EIB.1 The prevalence of EIB varies from about 10% in the general population to about 50% in some fields of competitive athletics.1 The pathophysiology of EIB is not well understood. However, respiratory water loss leads to the release of inflammatory mediators, such as histamine, leukotrienes (LTs) and prostaglandins (PGs), all of which can cause bronchoconstriction.1 2 Increased levels of exhaled nitric oxide have also been associated with EIB.3

There is evidence that vitamin C plays a role in lung function. The production of various prostanoids in lung tissues is influenced by vitamin C, and vitamin C deficiency increases the level of bronchoconstrictor PGF2α.4–6 An increase in airway hyper-responsiveness to histamine, which was further enhanced by indomethacin administration, was observed in guinea pigs on a diet deficient in vitamin C.6 In isolated guinea pig trachea smooth muscle, vitamin C decreased the contractions caused by PGF2α, histamine and carbamylcholine.4 7 8 Indomethacin antagonised the effect of vitamin C on chemically induced bronchoconstriction in humans9 10 and the effect of vitamin C on the contractions of guinea pig tracheal muscle.8 Thus, the effects of vitamin C might be partly mediated by alterations in PG metabolism. In humans, a 2-week vitamin C (1.5 g/day) administration regime reduced the postexercise increase in the urinary markers for the bronchoconstrictors LTC4–LTE4 and PGD2, in addition to reducing the increase in exhaled nitric oxide.11

Heavy physical exertion generates oxidative stress, and therefore, as an antioxidant, the effects of vitamin C might be more manifest in people doing exercise.12 13 The importance of vitamin C on the respiratory system is also indicated by the decrease in the incidence of the common cold in people under heavy acute physical stress14 15 and by its effects on the severity of the upper and lower respiratory tract infections.15–17

Previously, a systematic review examined the effect of vitamin C on EIB.18 However, there were substantial errors in the extraction of data and data analysis in that review.19 The purpose of this systematic review is to examine whether vitamin C administration influences the postexercise FEV1 decline.

Methods

Types of studies

Controlled trials, both randomised and non-randomised, were included in this systematic review. Only placebo-controlled blinded trials were included as the severity of EIB might be affected by the patients’ awareness of the treatment. Studies that used children and adults of either gender and any age were considered eligible.

Types of interventions

The intervention considered was oral or intravenous administration of vitamin C (ascorbic acid or its salts) of at least 0.2 g daily for a single day or for a more extended period. The dose limit was set as a pragmatic choice. When a trial with a low dose gives a negative result, the negative findings can be attributed to that low dosage. Thus, trials with large doses are more critical for testing whether vitamin C is effective in influencing EIB.

The outcomes and the measure of the vitamin C effect

The primary outcome in this meta-analysis is the relative FEV1 decline caused by exercise (as a percentage). The measures selected for the vitamin C effect were: (1) the arithmetic difference in the postexercise decline of FEV1 between the placebo and vitamin C periods; this is called the percentage point difference and (2) the relative effect in the decline of postexercise FEV1 between the vitamin C and placebo periods. A secondary outcome in this meta-analysis was the proportion of participants who suffered from EIB after the exercise test, and the measure of vitamin C effect was taken as the difference in the occurrence in EIB between the vitamin C and placebo days.

Literature searches

MEDLINE (OVID) was searched using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms ‘ascorbic acid’ and ‘exercise-induced asthma’. A similar search was carried out in Scopus. No language restrictions were used. The databases were searched from their inception to February 2013. The reference lists of identified studies and review articles were screened for additional references. See online supplementary file 1 for the flow diagram of the literature search.

Selection of studies and data extraction

Five controlled trials that report on vitamin C and EIB were identified. Three of them satisfied the selection criteria (table 1). One of the studies that was not included was not placebo controlled22 and the other studied the combination of vitamins C and E.23 The data of the three included trials were extracted and analysed. The original study authors were contacted when appropriate in order to obtain further data.

Table 1.

Trials on vitamin C supplementation and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction

| Study | Descriptions | |

|---|---|---|

| Schachter and Schlesinger20 | Methods | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial |

| Participants | 12 asthmatic participants, selected from among workers of Yale University in the USA: “all 12 participants gave a characteristic description of EIB.” All included participants had at least 20% reduction in maximal expiratory flow 40% after exercise 5 Males, 7 females; mean age of 26 years (SD 5 years) |

|

| Type of exercise | Exercise by using a cycloergometer was begun at a constant speed of 20 km/h against a zero workload. At the end of each 1 min interval, the workload was increased by 150 kpm/min, keeping the pedalling speed constant throughout the experiment. Exercise against progressively larger workloads was continued until either the heart rate reached 170 bpm or the participants fatigued | |

| Intervention | On 2 subsequent days, the participants ingested 0.5 g of vitamin C or sucrose placebo in identical capsules 1.5 h before the exercise. Washout overnight | |

| Outcome | Change in FEV1 was calculated as: (preexercise vs 5 min postexercise) | |

| Notes | See online supplementary file 2 for the calculation of the vitamin C effect from the individual-level data | |

| Cohen et al 21 | Methods | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial |

| Participants | 20 asthmatic participants in Israel. All of them had demonstrated EIB by having a ‘decline of at least 15%’ in FEV1 after a standard exercise test 13 Males, 7 females; mean age of 14 years (range 7–28 years) |

|

| Type of exercise | A 7 min exercise session using a motorised treadmill. Each participant exercised to submaximal effort at a speed and slope to provide 80% of the motional oxygen consumption as adjudged by a pulse oximeter | |

| Intervention | 2 g of vitamin C or placebo 1 h before the exercise. Washout 1 week | |

| Outcomes | Change in FEV1 was calculated as: (preexercise vs 8 min postexercise). Secondary outcome: proportion of participants who suffered from EIB after the exercise session (decline in FEV1 at least 15%) | |

| Notes | Individual-level data on the FEV1 levels was reported only for 11 of the 20 participants (Cohen et al, table 2). Dr Cohen was contacted, but he no longer had the data. Therefore, a conservative ‘no vitamin C effect’ was imputed for the 9 participants for whom experimental data were not available; see online supplementary file 2 | |

| Tecklenburg et al11 | Methods | Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial |

| Participants | 8 participants from a population of university students and the local community, Indiana, USA, with physician-diagnosed mild-to-moderate asthma. All participants had documented EIB as indicated by a ‘drop greater than 10%’ in postexercise FEV1. They also had a history of chest tightness, shortness of breath and intermittent wheezing following exercise. 2 Males, 6 females; mean age of 24.5 years (SD 5 years) |

|

| Type of exercise | Participants ran on a motorised treadmill, elevated by 1% per min until 85% of the age-predicted maximum heart rate and ventilation exceeding 40–60% of the predicted maximum voluntary ventilation. Participants maintained this exercise intensity for 6 min. Following the 6 min steady state exercise, the grade of the treadmill continued to increase at 1% per min until volitional exhaustion | |

| Intervention | 1.5 g vitamin C or sucrose placebo was administered as capsules matched for colour and size daily for 2 weeks. Washout 1 week. Participants were advised to avoid high vitamin C foods during the study |

|

| Outcome | Change in FEV1 was calculated as: (preexercise vs the lowest value within 30 min postexercise) | |

| Notes | Dr Tecklenburg kindly made the mean and SD for the paired FEV1 decline available. For the decline in FEV1 level, the mean difference was +6.5 percentage points (paired SD 7.4) in favour or vitamin C |

EIB, exercise-induced bronchoconstriction; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

Schachter and Schlesinger20 reported the individual-level FEV1 measurements for a 12-participant crossover study. The decline in FEV1 caused by exercise was calculated in this present study (see online supplementary file 2).

Tecklenburg et al11 reported the mean decline in postexercise FEV1 for the vitamin C and placebo phases of an eight-participant crossover study. However, these authors did not report the paired SD value for the mean difference between the two phases. Dr Tecklenburg was subsequently contacted, and she kindly sent the paired SD value for the mean difference in decline of the postexercise FEV1 (see online supplementary file 2).

Cohen et al21 reported FEV1 values before and after exercise in only 11 of the 20 participants of a crossover study. These 11 had been selected because of the disappearance of EIB during the study. Thus, the difference in the postexercise FEV1 decline between the vitamin C and placebo days can be calculated for these 11 participants (the mean vitamin C effect was a reduction of 20.4 percentage points in the postexercise decline in FEV1). Dr Cohen was contacted, but he no longer retained those data. Therefore, to include the Cohen et al trial in this meta-analysis, the FEV1 values for the remaining nine participants had to be imputed. A conservative ‘no vitamin C effect’ estimate was imputed for all the nine participants with missing data (see online supplementary file 2). As a sensitivity analysis, the Cohen et al study was excluded from the meta-analysis in figure 1 to examine whether its exclusion influenced the conclusions.

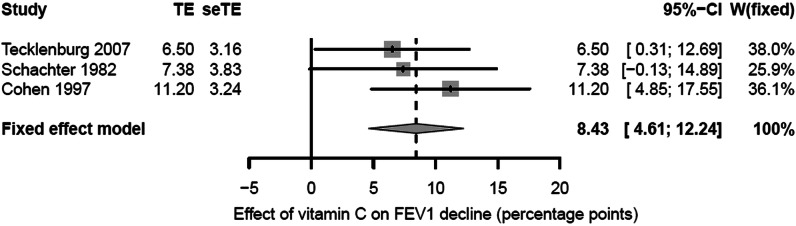

Figure 1.

Percentage point effect of vitamin C on the decline in FEV1 caused by exercise. The horizontal lines indicate the 95% CI for the three trials and the squares in the middle of the lines indicate the mean effect of the study. The diamond shape at the bottom indicates the 95% CI for the pooled effect. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; seTE, SE of TE; TE, treatment effect; W, weight of the study.

Cohen et al also reported the number of participants who suffered from EIB after the exercise test. This outcome did not require imputations and it was used as a secondary outcome for comparing the vitamin C and placebo days in the Cohen study.

Statistical analysis

The statistical heterogeneity of the three studies was assessed by using the χ2 test and the I2 index.24 The latter examines the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity between studies rather than by randomness. A value of I2 greater than about 70% indicates a high level of heterogeneity. Since the three identified trials showed no statistical heterogeneity, their results were pooled using the inverse variance method assuming a fixed effect by running the program ‘metagen’ of the R package (see online supplementary file 2 for details of the calculations).25 The program ‘forest.meta’ of the R package was used to construct the forest plots.

To examine the relative effect of vitamin C on the postexercise FEV1 decline, the vitamin C effect was modelled using the placebo-day postexercise FEV1 decline as the explanatory variable, by using the linear model “lm” program of the R package.25 To test whether the addition of the placebo-day postexercise FEV1 decline values significantly improves the linear model fit, the model containing the placebo-day FEV1 decline values was compared with the model without them. The improvement of the model fit was calculated from the change in −2×log (likelihood), which follows the χ2 (1 df) distribution.

To study the effect of vitamin C on the proportion of participants who suffered from EIB in the Cohen et al study, the mid p value was calculated26 and the 95% CI was calculated by using the Agresti-Caffo method.27

The two-tailed p values are presented in this text.

Results

Three randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover trials that had examined the effect of vitamin C supplementation on the decline in FEV1 caused by exercise were retrieved. Double-blind means that all studies used allocation concealment, although the term was not used. The experimental conditions were similar (table 1). The three trials had a total of 40 participants. There was no statistical heterogeneity found between the three studies for the percentage points scale: I2=0%; χ2 (2 df)=1.1; p=0.5. Therefore, the pooled percentage point estimate of the vitamin C effect was calculated (figure 1). Compared with the placebo phases, the mean reduction in the postexercise FEV1 decline was 8.4 percentage points during the vitamin C phases (95% CI 4.6 to 12.2; p<0.001).

In the Schachter and Schlesinger20 study, the postexercise FEV1 decline was 17.6% for placebo, but only 10.2% for vitamin C (0.5 g single dose), with a 7.4 percentage point (95% CI −0.1 to 14.9; p=0.054) improvement for the vitamin C treatment. In the Tecklenburg et al11 study, the postexercise FEV1 decline was 12.9% when on placebo, but only 6.4% when on vitamin C (1.5 g/day for 2 weeks), indicating an improvement of 6.5 percentage points (95% CI 0.3 to 12.7; p=0.042) for vitamin C. With the conservative imputation of the ‘no vitamin C effect’ for nine participants in the Cohen et al21 study, there was a reduction in the postexercise FEV1 decline by 11.2 percentage points (95% CI 4.8 to 17.6; p=0.002) on the vitamin C day (2 g single dose).

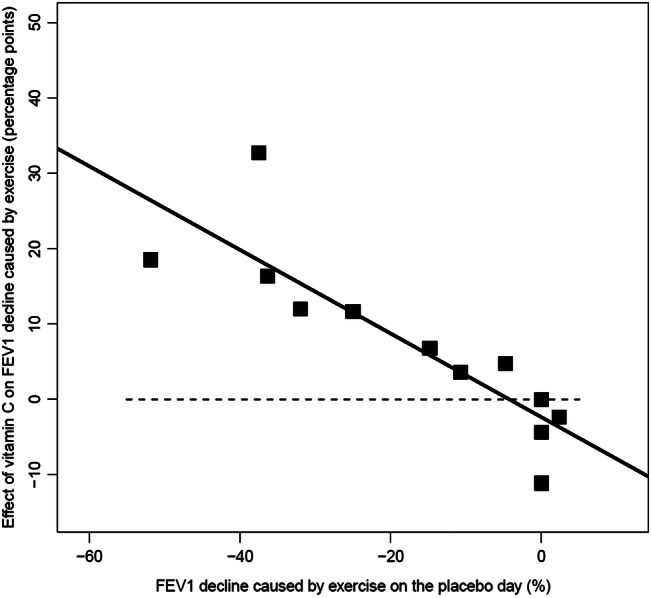

EIB is not a dichotomous condition; instead, there is a continuous variation in the possible level of FEV1 decline caused by exercise. A single constant percentage point estimate of the vitamin C effect for all people who suffer from EIB may thus be simplistic. Instead, it is possible that a relative scale would better capture the effect of vitamin C. Schachter and Schlesinger20 published individual-level data for all their 12 participants, and thus their data were analysed using linear modelling to examine whether the vitamin C effect might depend on the placebo-day postexercise FEV1 decline, that is, on the baseline severity of EIB (figure 2). Adding the placebo-day postexercise FEV1 decline values to the null linear model, which is equivalent to the t test, improved the model fit by χ2 (1 df)=16.5, corresponding to p<0.001. This indicates that the linear model that includes the placebo-day postexercise FEV1 decline explains the effect of vitamin C much better than the constant 7.4 percentage point effect for all their participants suffering from EIB. The slope of the linear model indicates a 55% reduction in the decline of the postexercise FEV1 (95% CI 32% to 78%; p<0.001) for vitamin C administration compared with placebo. Thus, in the percentage points scale, though there was a trend towards a mean vitamin C effect, the difference between vitamin C and placebo in the Schachter and Schlesinger trial was not significant (p=0.054), whereas in the linear model the slope indicates a highly significant difference between vitamin C and placebo (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

The effect of vitamin C on postexercise forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) decline as a function of the placebo-day postexercise FEV1 decline for the Schachter and Schlesinger study.20 The squares show the 12 participants of the study. The vertical axis shows the difference in postexercise FEV1 decline between the vitamin C and the placebo days. The horizontal axis shows the postexercise FEV1 decline on the placebo day. The black line indicates the fitted linear regression line. The horizontal dash (-) line indicates the level of identity between vitamin C and placebo. See online supplementary file 2 for the calculations.

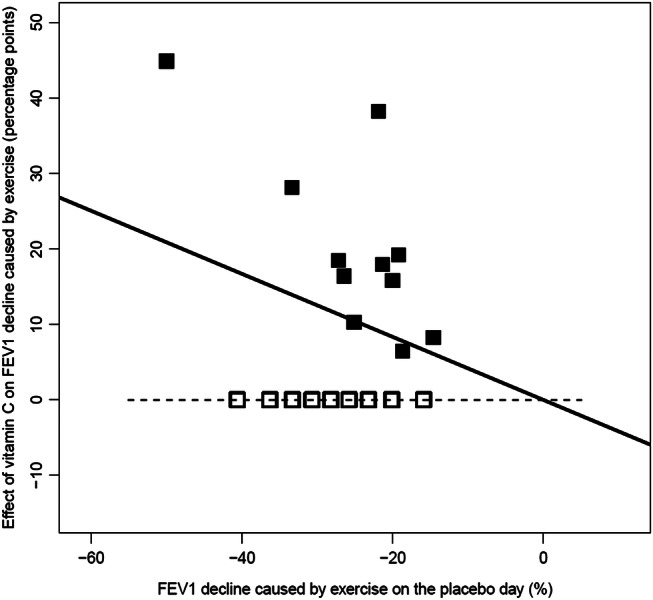

Cohen et al21 published individual-level data for only 11 of their 20 participants (filled squares in figure 3). A conservative ‘no vitamin C effect’ was imputed for the remaining nine participants (open squares in figure 3). Only those participants who had a decline in postexercise FEV1 of at least 15% were included in the Cohen et al study, and therefore the horizontal variation in the Cohen et al data was narrow. Fitting the linear regression line through the origin indicates a 42% reduction in the postexercise FEV1 decline (95% CI 19% to 64%) with vitamin C administration.

Figure 3.

The effect of vitamin C on postexercise forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) decline as a function of the placebo-day postexercise FEV1 decline for the Cohen et al21 study. The filled squares show the 11 participants for whom data were reported and the empty squares show the nine participants for whom the conservative ‘no vitamin C effect’ data were imputed. The vertical axis shows the difference in the postexercise FEV1 decline between the vitamin C and the placebo days. The horizontal axis shows the postexercise FEV1 decline on the placebo day. The black line indicates the fitted linear regression line. The horizontal dash (-) line indicates the level of identity between vitamin C and placebo. The linear regression line was fitted through the origin, since the variation in the placebo-day FEV1 decline values is narrow. See online supplementary file 2 for the calculations.

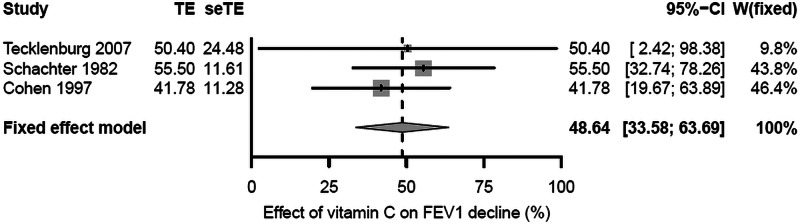

Tecklenburg et al11 did not report individual-level data for their eight participants and the data were not available. The mean values indicate a 50.4% (95% CI 2.4% to 98%) reduction in the postexercise FEV1 decline for the vitamin C period.

There was no statistical heterogeneity found between the three studies on the relative effect scale: I2=0%; χ2 (2 df)=0.7; p=0.7. Therefore, the pooled estimate of the relative vitamin C effect was calculated for the three trials (figure 4). Compared with the placebo phases, vitamin C administration reduced the postexercise FEV1 decline by 48% (95% CI 33% to 64%; p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Relative effect of vitamin C on the decline in FEV1 caused by exercise. The horizontal lines indicate the 95% CI for the three trials and the squares in the middle of the lines indicate the mean effect of the study. The diamond shape at the bottom indicates the 95% CI for the pooled effect. The estimates for the Schachter 1982 and Cohen 1997 studies are based on the slopes of the linear models in figures 3 and 4. The estimates for the Tecklenburg 2007 study are the study mean estimates. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; seTE, SE of TE; TE, treatment effect; W, weight of the study.

As a sensitivity test, the Cohen et al study was excluded from the meta-analysis in figure 1. On the basis of the two remaining trials, the estimate of the vitamin C effect on the postexercise FEV1 decline became 6.8 percentage points (95% CI 2.0 to 11.6; p=0.005). Thus, the Cohen et al study imputations are not crucial for the conclusion that vitamin C influences the postexercise FEV1 decline.

Finally, although Cohen et al did not report individual-level data for the postexercise FEV1 decline values for nine of their participants, they reported the presence or absence of EIB (at least a 15% decline in postexercise FEV1) on the vitamin C and placebo days and this dichotomised FEV1 outcome does not suffer from missing data. On the placebo day, 100% (20/20) of participants suffered from EIB, whereas on the vitamin C day, only 50% (10/20) suffered from EIB. This outcome gives a 50 percentage point decrease (95% CI 23 to 68; p<0.001) in the occurrence of EIB following vitamin C administration.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis of three randomised placebo-controlled double-blind trials, vitamin C was found to reduce the postexercise decline in FEV1 by a mean of 8.4 percentage points (figure 1). Nevertheless, there is a great variation in the level of FEV1 decline caused by exercise. Therefore, it may not be reasonable to assume that a single and constant percentage point estimate of the vitamin C effect is valid for all persons suffering from EIB. Linear modelling of the Schachter and Schlesinger20 data indicated that it is much better to study the response to vitamin C administration as a relative effect (figure 2). However, full individual-level data were not available for the other two trials. Nonetheless, all three studies are consistent with vitamin C administration halving the postexercise decline in FEV1 (figure 4).

The Cohen et al21 study required imputations for nine participants; however, excluding the Cohen et al study from the percentage point meta-analysis did not influence conclusions. Furthermore, Cohen et al reported that the number of participants who suffered from EIB dropped from 100% on the placebo day to 50% on the vitamin C day and this outcome did not require imputations; yet the highly significant benefit of vitamin C was also seen in this outcome.

The three studies included in this systematic review indicate that 0.5–2 g of vitamin C administration before exercise may have a beneficial effect on many people suffering from EIB. All the three trials were double-blind placebo-controlled randomised trials. The total number of participants in the three trials is only 40. However, the three trials were carried out in three different decades and on two different continents. The criteria for EIB differed and the mean age of the participants was 14 years in the Cohen et al study but 25 and 26 years in the two other studies. Still, all the studies found a 50% reduction in the postexercise FEV1 decline. It is not evident how far this 50% estimate can be generalised, but the close estimate in such different studies suggests that the estimate may also be valid for several other people who suffer from EIB.

The search, screening and selection for trials and data extraction were carried out by one person, which may be considered a limitation of this study. In addition, only two databases were searched; however, in an independent literature search, the Cochrane review on vitamin C and asthma did not identify more trials on vitamin C and EIB.18 Data analysis was also performed by one person, but the supplementary files show the extracted data and data analyses, which makes the study transparent. No risk of bias or quality assessment was performed as part of this study.

In evidence-based medicine, the primary question is whether an intervention has effects on clinically relevant outcomes, as well as on symptoms such as coughs. With such a perspective, the aetiology of respiratory symptoms is not of prime importance. Given the low cost and safety of vitamin C,15 28 and the consistency of positive findings in the three studies on EIB, it seems reasonable for physically fit and active people to test vitamin C on an individual basis if they have respiratory symptoms such as cough associated with exercise.

The promising results of EIB and common cold studies indicate that further research on vitamin C and the respiratory symptoms of physically active people are warranted. In future trials, statistical modelling should be used to examine the effect of vitamin C on FEV1 levels, instead of simply calculating the percentage point estimates. Although the primary question in the evidence-based medicine framework is to assess the effectiveness of vitamin C on clinically relevant outcomes, the aetiology of the respiratory symptoms should also be investigated in future investigations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr Tecklenburg who kindly supplied supplementary data for this analysis and Elizabeth Stovold for her contributions to an early version of this manuscript, by helping in the literature searches, considering studies for inclusion and extracting data for the meta-analysis.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All collected and imputed data are presented in online supplementary files 2 and 3 and are freely available.

References

- 1.Weiler JM, Anderson SD, Randolph C. Pathogenesis, prevalence, diagnosis, and management of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;105(6 Suppl):S1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson SD, Kippelen P. Airway injury as a mechanism for exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in elite athletes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:225–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchvald F, Hermansen MN, Nielsen KG, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide predicts exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in asthmatic school children. Chest 2005;128:1964–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puglisi L, Berti F, Bosisio E, et al. Ascorbic acid and PGF2α antagonism on tracheal smooth muscle. Adv Prostaglandin Thromboxane Res 1976;1:503–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothberg KG, Hitchcock M. Effects of ascorbic acid deficiency on the in vitro biosynthesis of cyclooxygenase metabolites in guinea pig lungs. Prostaglandins Leukot Med 1983;12:137–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohsenin V, Tremml PG, Rothberg KG, et al. Airway responsiveness and prostaglandin generation in scorbutic guinea pigs. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 1988;33:149–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuskin E, Lewis AJ, Bouhuys A. Inhibition of histamine-induced airway constriction by ascorbic acid. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1973;51:218–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sipahi E, Ercan ZS. The mechanism of the relaxing effect of ascorbic acid in guinea pig isolated tracheal muscle. Gen Pharmacol 1997;28:757–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogilvy CS, DuBois AB, Douglas JS. Effects of ascorbic acid and indomethacin on the airways of healthy male subjects with and without induced bronchoconstriction. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1981;67:363–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohsenin V, Dubois AB, Douglas JS. Effect of ascorbic acid on response to methacholine challenge in asthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis 1983;127:143–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tecklenburg SL, Mickleborough TD, Fly AD, et al. Ascorbic acid supplementation attenuates exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in patients with asthma. Respir Med 2007;101:1770–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powers SK, Jackson MJ. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: cellular mechanisms and impact on muscle force production. Physiol Rev 2008;88:1243–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashton T, Young IS, Peters JR, et al. Electron spin resonance spectroscopy, exercise, and oxidative stress: an ascorbic acid intervention study. J Appl Physiol 1999;87:2032–6 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10601146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemilä H. Vitamin C and common cold incidence: a review of studies with subjects under heavy physical stress. Int J Sports Med 1996;17:379–83 http://hdl.handle.net/10250/7983 (accessed 7 May 2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemilä H, Chalker E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(1):CD000980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemilä H. Vitamin C supplementation and common cold symptoms: problems with inaccurate reviews. Nutrition 1996;12:804–9 http://hdl.handle.net/10250/7979 (accessed 7 May 2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemilä H, Louhiala P. Vitamin C may affect lung infections. J R Soc Med 2007;100:495–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur B, Rowe BH, Stovold E. Vitamin C supplementation for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD000993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemilä H. Feedback. In: Kaur B, Rowe BH, Stovold E. Vitamin C supplementation for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD000993 http://hdl.handle.net/10138/38500 (accessed 7 May 2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schachter EN, Schlesinger A. The attenuation of exercise-induced bronchospasm by ascorbic acid. Ann Allergy 1982;49:146–51 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7114587 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen HA, Neuman I, Nahum H. Blocking effect of vitamin C in exercise-induced asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997;151:367–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miric M, Haxhiu MA. Effect of vitamin C on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction [Serbo-Croatian]. Plucne Bolesti 1991;43:94–7 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1766998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy JD, Ferguson CS, Brown KR, et al. The effect of dietary antioxidants on lung function in exercise induced asthma [abstract]. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34(5 Suppl):S155 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analysis. BMJ 2003;327:557–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The R Project for Statistical Computing http://www.r-project.org/ (accessed 7 May 2013)

- 26.Lydersen S, Fagerland MW, Laake P. Recommended tests for association in 2 × 2 tables. Stat Med 2009;28:1159–75 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19170020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fagerland MW, Lydersen S, Laake P. Recommended confidence intervals for two independent binomial proportions. Stat Methods Med Res 2011. Published Online First 2011.10.1177/0962280211415469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hathcock JN, Azzi A, Blumberg J, et al. Vitamins E and C are safe across a broad range of intakes. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:736–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.