Abstract

Objective

Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP) represents a major pathogen in pneumonia. The impact of azithromycin on mortality in SP pneumonia remains unclear. Recent safety concerns regarding azithromycin have raised alarm about this agent's role with pneumonia. We sought to clarify the relationship between survival and azithromycin use in SP pneumonia.

Design

Retrospective cohort.

Setting

Urban academic hospital.

Participants

Adults with a diagnosis of SP pneumonia (January–December 2010). The diagnosis of pneumonia required a compatible clinical syndrome and radiographic evidence of an infiltrate.

Intervention

None.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Hospital mortality served as the primary endpoint, and we compared patients given azithromycin with those not treated with this. Covariates of interest included demographics, severity of illness, comorbidities and infection-related characteristics (eg, appropriateness of initial treatment, bacteraemia). We employed logistic regression to assess the independent impact of azithromycin on hospital mortality.

Results

The cohort included 187 patients (mean age: 67.0±8.2 years, 50.3% men, 5.9% admitted to the intensive care unit). The most frequently utilised non-macrolide antibiotics included: ceftriaxone (n=111), cefepime (n=31) and moxifloxacin (n=22). Approximately two-thirds of the cohort received azithromycin. Crude mortality was lower in persons given azithromycin (5.6% vs 23.6%, p<0.01). The final survival model included four variables: age, need for mechanical ventilation, initial appropriate therapy and azithromycin use. The adjusted OR for mortality associated with azithromycin equalled 0.26 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.80, p=0.018).

Conclusions

SP pneumonia generally remains associated with substantial mortality while azithromycin treatment is associated with significantly higher survival rates. The impact of azithromycin is independent of multiple potential confounders.

Article summary.

Article focus

To determine the impact of azithromycin cotherapy on outcomes in Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia.

Key messages

Azithromycin cotherapy in pneumonia due to S pneumoniae is associated with improved short-term survival.

This finding is independent of multiple potential confounders including timeliness of antibiotic treatment.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Large sample of pure S pneunmoniae pneumonia.

Data are derived from a single centre and the study's retrospective design.

Introduction

Pneumonia remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Annually, more than 1.3 million patients in the USA present to the hospital with pneumonia and require admission.1 Direct costs related to pneumonia exceed several billion each year in the USA.1 Owing to this burden, multiple efforts have focused on improving the care of patients with pneumonia and attempted to address the means of enhancing the outcomes of this disease and hospitalists often care for and design hospital pathways for those admitted with pneumonia.

Concurrent with these quality efforts, the microbiology of pneumonia presenting to the hospital has evolved. Over the last decade, pathogens traditionally thought to be confined to the hospital, such as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are now implicated in non-nosocomial pneumonia.2 3 This epidemiological trend has led to the creation of the concept of healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP).2 3 At the same time, the rates of pneumonia in adults due to Streptococcus pneumoniae have diminished, in part due to the effects of herd immunity arising from the use of the newer vaccines in children.4 Nonetheless, S pneumoniae remains a leading pathogen in non-nosocomial pneumonia, whether it be CAP or HCAP and whether it results in mild disease or more severe illness necessitating admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).5 6 Furthermore, current treatment guidelines for HCAP do not suggest consideration of adjunctive macrolide antibiotics, despite the fact that S pneumoniae can still be seen in this syndrome.3 5 7 While some surveillance studies indicate that S pneumoniae remains the most prevalent pathogen in patients admitted with pneumonia via the emergency department (ED), other studies suggest that S pneumoniae often represents either the second or third most frequent pathogen in this setting.5 6 8 Thus, despite its potentially being less prevalent than in previous years, S pneumoniae continues to lead to a disproportionate burden on the healthcare system.

Macrolide antibiotics, particularly azithromycin, are unique as anti-infective agents in that they appear to have potent anti-inflammatory properties.9 Earlier analyses suggest that azithromycin exposure may confer a mortality advantage in CAP, irrespective of the causative pathogen.10 11 This observation has resulted in treatment guidelines recommending the utilisation of macrolides in CAP and their continuation even if the patient is concurrently being treated with another in vitro active antimicrobial as one potential approach.12 Many of the reports supporting a survival benefit related to macrolide use in CAP, however, have been limited either because they were conducted in an era before HCAP became a concern or because they often did not account for issues related to rates of initially appropriate antimicrobial administration. These reports have also explored CAP as a syndrome, regardless of the pathogen, and not specifically addressed S pneumoniae. Recent descriptions of potential cardiovascular toxicities arising with azithromycin reinforce the need for elucidation if this agent alters mortality.13 A potential survival benefit related to azithromycin in S pneumoniae pneumonia would indicate that the risk/benefit calculus favours utilisation of this agent notwithstanding concerns about rhythm disturbances.

We hypothesised that cotreatment with azithromycin would improve mortality in pneumonia due to S pneumoniae and that this effect would be independent of confounding arising from failure to administer appropriate initial antibiotic therapy. To explore our hypothesis, we conducted a retrospective analysis of all patients with either CAP or HCAP admitted with evidence of infection related to S pneumoniae.

Methods

Study overview and patients

We retrospectively identified all adult (age >18 years) patients admitted with a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2010. All patients were required to have initially presented to ED. We defined pneumonia based on both signs and symptoms of infection (ie, elevated white blood cell count or >10% band forms, fever or hypothermia). We further required compatible chest imaging documenting an infiltrate(s). One investigator (MHK), blinded to the clinical and microbiological information, adjudicated the chest imaging. Identification of S pneumoniae was based on the results of cultures from blood, pleural fluid, sputum or the lower airways. A positive urinary antigen for S pneumoniae was also used to document infection with this pathogen. The patients described in this report have been previously included in an earlier analysis validating the concept of HCAP.3 The Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee approved the study (# 201205194). As this was a retrospective analysis, there was no requirement for informed consent.

Endpoints and covariates

Hospital mortality represented the primary endpoint. We compared persons with pneumococcal pneumonia initially treated with azithromycin with those not given this agent. During the observation period, this was the only macrolide available for treatment of pneumonia at the study hospital. There were no patients given clarithromycin. Covariates of interest included patient demographics, severity of illness and infection-related variables. Demographic factors included age, gender and race. With respect to comorbidities, we recorded if the patient was residing in a nursing home or long-term care facility, was recently hospitalised in the last 90 days, had received antimicrobials in the last 30 days, suffered from end-stage renal disease requiring haemodialysis, or was immunosuppressed. We defined immunosuppression based on the presence of either AIDS, active malignancy undergoing chemotherapy or treatment with immunosuppressants (ie, 10 mg prednisone or equivalent daily for at least 30 days or alternate agents such as methotrexate). To assess disease severity, we calculated the CURB-65 score along with recording if there was a need for either ICU care or mechanical ventilation (MV).14 With respect to infection-related variables, we determined if bacteraemia complicated the pneumonia and the initial antibiotic regimen. We classified the initial antibiotic regimen as appropriate if a non-macrolide antibiotic that was in vitro active against the S pneumoniae isolate was administered within 4 h of presentation.15 At the host institution, antibiotic administration is protocolised such that all patients received a non-macrolide anti-infective with activity against pneumoccocus. Therefore, appropriateness of antibiotics was a reflection of the timeliness of administration. Additionally, by convention, patients given a combination treatment including azithromycin received these drugs concurrently.

Statistics

We completed univariate analyses with either the Fisher's exact test or Student t test as appropriate. Continuous, non-parametrically distributed data were compared via the Mann-Whitney U test. All analyses were two-tailed, and a p value of <0.05 was assumed to represent statistical significance. To determine independent factors associated with mortality, we employed logistic regression. Variables significant at the p<0.10 level in univariate analyses were entered into the model. We utilised an enter approach for the regression. Colinearity was explored with correlation matrices. Adjusted ORs (AORs) and 95% CIs are reported where appropriate. The model's goodness-of-fit was assessed via calculation of the R2 value and the Hosmer-Lemeshow C-statistic. All analyses were performed with SPSS V.19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

During the study period, 977 persons were admitted via ED with evidence of bacterial pneumonia. Of these patients, 187 were infected with S pneumoniae. The mean age of these patients was 57.0±8.2 years and approximately half were men. The crude hospital mortality in S pneumoniae pneumonia equalled 11.2% while the mean hospital length of stay measured 8.2±5.0 days. The most commonly utilised non-azithromycin antibiotics were ceftriaxone (n=111), cefepime (n=31) and moxifloxacin (n=22).

Table 1 reveals the differences in baseline characteristics between patients dying while hospitalised and those surviving to discharge. Those who died were older but there were no other differences in demographics. Patients dying were more severely ill based on all measures used to assess this. Specifically, survivors had lower CURB-65 scores as compared with decedents (median CURB-65 class 4 vs 2, p=0.025). More than a quarter of those dying received MV while fewer than 5% of those discharged alive required MV (p=0.001). The distribution of criteria defining HCAP did not differ between groups. Approximately 11% of all patients resided in nursing homes prior to admission and the rate of admission from nursing homes did not correlate with hospital mortality. Immunosuppression was prevalent in the study population, but this also did not differ between those dying and those surviving.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Hospital death (n=21) | Hospital survival (n=166) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean±SD (years) | 66.8±18.23 | 55.7±15.0 | 0.002 |

| Male (n, %) | 10, 47.6 | 84, 50.6 | 0.821 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian (n, %) | 10, 47.6 | 87, 52.4 | 0.767 |

| African-American (n, %) | 11, 52.4 | 77, 46.5 | |

| Other (n, %) | 0, 0 | 2, 1.2 | |

| Severity of illness | |||

| CURB 65 score, median | 4 | 2 | 0.025 |

| CURB score distribution (n, %) | – | ||

| 0 | 0, 0 | 28, 16.9 | |

| 1 | 2, 9.5 | 51, 30.7 | |

| 2 | 0, 0 | 28, 16.9 | |

| 3 | 6, 28.6 | 29, 17.5 | |

| 4 | 10, 47.6 | 25, 15.1 | |

| 5 | 3, 14.3 | 5, 3 | |

| ICU admission (n, %) | 5, 22.9 | 6, 3.6 | 0.001 |

| MV (n, %) | 6, 27.8 | 8, 4.8 | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| LTC admission (n, %) | 2, 11.1 | 19, 11.4 | 0.999 |

| HD (n, %) | 0 | 4, 2.4 | 0.999 |

| Immunosuppression (n, %) | 7, 33.3 | 38, 22.9 | 0.289 |

| Prior antibiotics (n, %) | 7, 33.3 | 40, 24.1 | 0.423 |

| Recent hospitalisation (n, %) | 3, 14.1 | 15, 9.0 | 0.353 |

| Infection-related characteristics | |||

| Bacteraemia (n, %) | 3, 14.1 | 13, 7.8 | 0.256 |

| Delay in appropriate antibiotics (%)* | 8, 38.1 | 15, 9.0 | 0.001 |

| Antibiotic therapy | 0.099 | ||

| Ceftriaxone (n, %) | 7, 33.3 | 104, 62.7 | |

| Cefepime (n, %) | 8, 38.1 | 23, 13.9 | |

| Moxifloxacin (n, %) | 1, 4.8 | 21, 12.7 | |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam (n, %) | 2, 9.5 | 8, 4.8 | |

| Other (n, %) | 3, 14.3 | 10, 6.0 | |

| Any β-lactam/cephalosporin | 17, 81.0 | 135, 81.8 | 0.999 |

| Azithromycin | 5, 23.8 | 9, 5.4 | |

HD, haemodialysis; ICU, intensive care unit; LTC, long-term care; MV, mechanical ventilation.

With respect to infection-related characteristics, the frequency of bacteraemia was similar between the two groups. Compared with those who survived, however, those who died were more likely to have been given delayed antibiotic therapy (38.1% vs 9.0%, p=0.001). In all instances, inappropriate therapy occurred not because of the use of an in vitro inactive agent but because of a delay in the initiation of antibiotics. All isolates were susceptible to the agents actually administered.

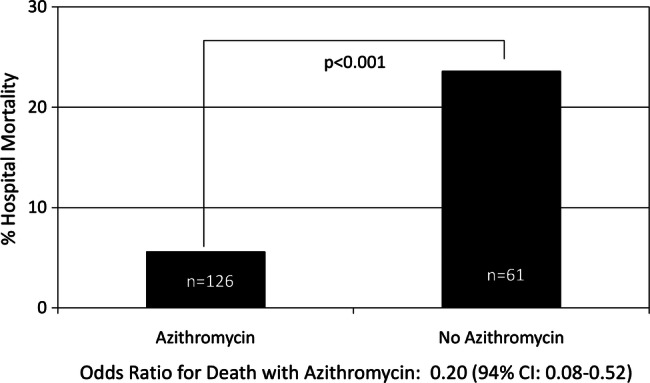

Hospital death rates were significantly lower in persons treated with azithromycin. Of patients given the macrolide, only 5.4% expired in the hospital as opposed to 23.8% of persons not treated with such an agent (figure 1). The OR for death with a macrolide was 0.20 (94% CI 0.08 to 0.52).

Figure 1.

Hospital mortality and azithromycin treatment. OR for death with azithromycin: 0.20 (94% CI 0.08 to 0.52).

In the logistic regression, four variables remained independently associated with mortality (table 2). Mortality increased with increasing age (AOR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.09, p=0.018) and with the need for MV (AOR 8.82, 95% CI 2.74 to 28.46, <0.001). Timely antibiotic therapy resulted in lower in-hospital death rates (AOR, 0.13, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.46, p=0.002). Finally, treatment with azithromycin correlated with enhanced survival. Azithromycin exposure was independently associated with reduced risk for death by nearly 75% (AOR 0.26, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.90, p=0.018). Neither being classified as HCAP nor any of the individual criteria defining HCAP stayed in the final model. The model had an excellent fit with an R2 value of 0.42 and a C-statistic of 0.991. In a sensitivity analysis (table 2) where the CURB 65 score was employed as a marker for severity of illness rather than either need for MV or ICU admission, treatment with azithromycin remained associated with a lower probability for mortality (AOR 0.34, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.88).

Table 2.

Factors associated with mortality

| Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR (AOR) | 95% CI for AOR | p Value for AOR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables associated with hospital mortality | ||||

| Age, per year | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.01 to 1.09 | 0.018 |

| Need for MV | 8.14 | 8.82 | 2.74 to 28.46 | 0.001 |

| Appropriate therapy | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.03 to 0.47 | 0.002 |

| Use of Azithromycin | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.08 to 0.80 | 0.018 |

| Sensitivity analysis for mortality | ||||

| Age, per year | 1.05 | 1.02 | 0.98 to 1.05 | 0.368 |

| CURB-65 score, per point increase | 2.43 | 2.07 | 1.32 to 3.25 | 0.001 |

| Appropriate therapy | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.03 to 0.42 | 0.001 |

| Use of azithromycin | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.11 to 0.88 | 0.041 |

MV, mechanical ventilation.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of a cohort of patients with microbiologically confirmed pneumococcal pneumonia indicates that the coadministration of azithromycin is associated with significant reductions in short-term mortality. This effect is independent of multiple potential confounders such as severity of illness and the timeliness and activity of initial antimicrobial therapy. The positive impact of azithromycin was also independent of whether bacteraemia was present.

Prior efforts evaluating the significance of macrolide therapy on outcomes in CAP have reached conflicting conclusions. Some large case series indicate a survival benefit in persons given macrolides while others have failed to detect such an impact. For example, Martin-Loeches et al10 observed that macrolide use reduced the risk for mortality in intubated patients with CAP. In a large observational German study, Tessmer et al11also noted that macrolide exposure improved the cure rates and short-term mortality. In pneumococcal bacteraemia complicating pneumonia, Metersky et al15 conclude that macrolide use improved the 30-day re-admission and death rates. On the other hand, Asadi et al16 reported that death rates were similar among 3000 patients treated with either monotherapy with a fluoroquinolone as opposed to a β-lactam/macrolide combination. Wilson et al17 additionally determined that inclusion of a macrolide in the antibiotic regimen failed to enhance survival in elderly patients with CAP. Meta-analyses are similarly conflicting in their assessments. One recent meta-analysis including 16 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating fluoroquinolones against β-lactam/macrolide combinations calculated that there was no difference in mortality between these regimens.18 However, another group of investigators included both observational reports and RCTs and determined that macrolide administration offered a small but statistically significant mortality benefit.19

Our findings add to this debate and are novel in several respects. First, one potential limitation of the aforementioned studies is that they tend to pool all patients with CAP, irrespective of the culture findings. In contrast, we restricted our evaluation to patients with confirmed S pneumoniae infection to determine whether they had CAP or risk factors for HCAP. Including patients with either syndrome serves to underscore the need to focus on the pathogen rather than the infectious syndrome. Treatment guidelines currently stratify persons into two cohorts based on their risk factors for infection with resistant pathogens.7 12 This scheme ignores the point that pneumococcal infection occurs in both CAP and HCAP. Our results suggest that revision of the guidelines may be appropriate as we noted a mortality benefit with azithromycin even after controlling for factors and comorbidities which define HCAP.

Furthermore, some of the patients in earlier reports either failed to have evidence of bacterial infection or were infected with a pathogen other than S pneumoniae. In some instances, only administrative coding data rather than actual culture results facilitated patient identification. This distinction is important in that the immunomodulatory effects of azithromycin have been most clearly elucidated as it relates to infection with S pneumoniae. Although broadly anti-inflammatory in a number of ways, the strongest biological evidence of a potential means for an impact in pulmonary infection relates to investigations in S pneumoniae. More importantly, these effects of macrolides alter both cellular and humoral immunity. In vitro, azithromycin, for instance, prevents apoptosis of human polymorphonuclear lymphocytes and may reduce interleukin (IL)-8 production.20 21 Furthermore, exposure to azithromycin reduces pneumolysin from both macrolide-susceptible and macrolide-resistant strains of S pneumoniae.22 Azithromycin may also reduce the production of tumour necrosis α and IL-1 α in human monocytes and downregulate natural killer cell production with an ensuing alteration in various cytokines.23 Therefore, by focusing on a specific organism where the nexus with the theoretical mechanisms of immune modulation is better established, our observations help to clarify the discordant findings of others. Our results, in turn, suggest that the benefit of macrolide cotreatment may be restricted to persons with pneumococcal infection.

We also specifically controlled for the timeliness of initial therapy. Initially appropriate and timely antibiotic treatment is a key determinant of survival in a number of severe infections ranging from bacteraemia to septic shock.24 25 Many prior studies of macrolides and S pneumoniae pneumonia simply did not address the timing of initial antimicrobial therapy. In most RCTs, adjudicating the coverage and timeliness of initial therapy is clouded by the time window allowed to enrol patients in the specific clinical trial. Some observational reports have failed to explore the importance of this issue in their analytic approaches. Others have simply determined whether an antibiotic regimen that was concordant with formal treatment guidelines was given. This constitutes only a surrogate means for evaluating the true appropriateness of antimicrobial treatment as it does not examine the specific in vitro susceptibilities or the timing of the antibiotic administration. We, however, specifically sought to rectify and address this limitation by applying specific and clear criteria.

Our overall patient outcomes suggest that our data are broadly generalisable. The crude hospital death rate was approximately 10%, as was the prevalence of bacteraemia, reflecting what has been noted in multiple epidemiological analyses.1 Likewise, the average length of stay (LOS) in our cohort parallels the general LOS for this syndrome described in large analyses of US hospital discharge data. The goodness of fit of our final mortality prediction model was also excellent, indicating that there is at most moderate, unmeasured residual confounding. Many earlier analyses of case series data have not described either if or how well their modelling of outcomes fits their observations.

Ray et al13 have sparked concern regarding macrolides and reported potential cardiovascular toxicity associated with azithromycin. In a review of Medicaid claims data from Tennessee, these authors state that deaths due to cardiovascular causes were higher in patients given azithromycin as compared with either no antibiotic or amoxicillin. This study has led to calls to re-evaluate our utilisation of azithromycin.26 The potential for a mortality benefit accruing with the use of this drug in pneumococcal pneumonia should give pause to efforts to reflexively and broadly restrict access to azithromycin. The burden and prevalence of pneumococcal pneumonia suggest that it would be inappropriate for policymakers to mix all types of S pneumoniae infection into one group as they make decisions regarding the availability of this agent. Our results suggest that a measured risk-benefit analysis is still required at the individual patient level.

The present study has several significant limitations. First, its retrospective nature exposes it to several forms of bias. However, unlike clinical cure, there is little potential for bias in determining the patient's vital status. Confounding by indication is a similar concern. However, if such confounding were present, we would expect this to bias our data towards the absence of an impact of azithromycin on mortality, while we observed precisely the opposite effect. Second, the data represent the experience from a single centre and thus may not be indicative of the experience of others. Likewise we only studied inpatients, and therefore our results do not apply to patients not requiring admission. Third, given the constraints of modern microbiology and culture techniques, there are certainly cases of pneumococcal pneumonia that we missed. Fourth, only 5% of the population required ICU admission. As such, our results mostly reflect the experience of less severely ill patients and the significance of azithromycin in critically ill persons may be different. These, though, are the patients most often cared for by hospitalists. Fifth, we lacked information on certain covariates that might have affected mortality, specifically underlying pulmonary and liver disease. Finally, the sample size precluded us from examining several important variables such as the exact timing of anti-infective administration (eg, by hour delay from presentation). It also likely explains why some variables were not significant in our final model. That the CURB-65 score failed to represent a correlate of mortality in our initial model probably arose because other factors associated with survival (eg, need for MV) proved to be more strongly linked with mortality. Likewise, the vast majority of persons given azithromycin were also given a β-lactam. As a result, few patients received either azithromycin alone or with moxifloxacin. Hence, we cannot exclude the possibility that the benefit with the macrolide is either a surrogate for exposure to a β-lactam agent or a function of the combined use of azithromycin with this class of antibiotics.

In conclusion, the coadministration of azithromycin appears to reduce mortality in persons admitted to the hospital with pneumoniae due to S pneumoniae. This effect persists after adjusting for other important variables known to correlate with survival in this syndrome. Given the safety issues that have arisen with azithromycin along with the possible positive impact of this drug on hospital mortality, a randomised trial exploring the role for adjunctive azithromycin relative to placebo in CAP appears to be not only warranted but urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AFS, MDZ, JH, JK, STM and MHK were involved in the study concept and design. JH, JK and STM participated in the acquisition of data. AFS, MDZ, STM and MHK participated in the analysis and interpretation of data. AFS, MDZ, MHK participated in the drafting of the manuscript. AFS, MDZ, JH, JK, STM and MHK participated in a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. AFS and MDZ participated in statistical expertise. MHK obtained funding. AFS and MHK participated in study supervision.

Funding: This project was supported by the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation.

Competing interests: AFS has served as a consultant to, speaker for, or received grant support from Astellas, Bayer, Cubist, Forrest, Pfizer, Theravance and Trius. MDZ has served as a consultant to or received grant support from Astellas, Forrest, J and J and Pfizer. MHK has served as a consultant to, speaker for, or received grant support from Cubist, Hospria, Merck and Sage. STM has received grant support from Cubist, Optimer, Merck and Pfizer. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts.

Ethics approval: Barnes Jewish IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Niederman M. In the clinic. Community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:ITC4-2–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF. Healthcare-associated pneumonia: the state of evidence to date. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2011;17:142–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Reichley R, et al. Validation of a clinical score for assessing the risk of resistant pathogens in patients with pneumonia presenting to the emergency department. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:193–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lexau CA, Lynfield R, Danila R, et al. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among older adults in the era of pediatric pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA 2005;294:2043–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia: results from a large US database of culture-positive pneumonia. Chest 2005;128:3854–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreiber MP, Chan CM, Shorr AF. Resistant pathogens in nonnosocomial pneumonia and respiratory failure: is it time to refine the definition of health-care-associated pneumonia? Chest 2010;137:1283–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;17:388–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansson N, Kalin M, Tiveljung-Lindell A, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia: increased microbiological yield with new diagnostic methods. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:202–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovaleva A, Remmelts HH, Rijkers GT, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of macrolides during community-acquired pneumonia: a literature review. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67:530–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin-Loeches I, Lisboa T, Rodriguez A, et al. Combination antibiotic therapy with macrolides improves survival in intubated patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:612–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tessmer A, Welte T, Martus P, et al. Impact of intravenous {beta}-lactam/macrolide versus {beta}-lactam monotherapy on mortality in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;63:1025–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, et al. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1881–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 2003;58:377–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metersky ML, Ma A, Houck PM, et al. Antibiotics for bacteremic pneumonia: improved outcomes with macrolides but not fluoroquinolones. Chest 2007;131:466–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asadi L, Eurich DT, Gamble JM, et al. Impact of guideline-concordant antibiotics and macrolide/β-lactam combinations in 3203 patients hospitalized with pneumonia: prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012.10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03783.x [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22404691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson BZ, Anzueto A, Restrepo MI, et al. Comparison of two guideline-concordant antimicrobial combinations in elderly patients hospitalized with severe community acquired pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2012. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22622401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skalsky K, Yahav D, Lador A, et al. Macrolides vs. quinolones for community-acquired pneumonia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012.10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03838.x [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22489673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asadi L, Sligl WI, Eurich DT, et al. Macrolide-based regimens and mortality in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2012. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 22511553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch CC, Esteban DJ, Chin AC, et al. Apoptosis, oxidative metabolism and interleukin-8 production in human neutrophils exposed to azithromycin: effects of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2000;46:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verleden GM, Vanaudenaerde BM, Dupont LJ, et al. Azithromycin reduces airway neutrophilia and interleukin-8 in patients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:566–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson R, Steel HC, Cockeran R, et al. Comparison of the effects of macrolides, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, doxycycline, tobramycin and fluoroquinolones, on the production of pneumolysin by Streptococcus pneumoniae in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60:1155–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin SJ, Yan DC, Lee WI, et al. Effect of azithromycin on natural killer cell function. Int Immunopharmacol 2012;13:8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y, et al. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest 2009;136:1237–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micek ST, Lloyd AE, Ritchie DJ, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection: importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005;49:1306–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FDA Statement regarding azithromycin (Zithromax) and the risk of cardiovascular death. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/Drugsafety/ucm304372.htm (accessed 12 Jul 2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.