Abstract

Objective

To assess changes in the inequalities associated with maternal healthcare use according to economic status in the Philippines.

Design

An analysis of four population-based data sets that were conducted between 1993 and 2008.

Setting

Philippines.

Participants

Women aged 15–49 years who had a live-birth within 1 year in 1993 (n=1707), 1998 (n=1513), 2003 (n=1325) and 2008 (n=1209).

Outcomes

At least four visits of antenatal care, skilled birth attendance and delivery in a medical facility.

Results

The adjusted OR for antenatal-care use when comparing the highest wealth-index quintile with the lowest quintile declined from 1993 to 2008: 3.43 (95% CI 2.22 to 5.28) to 2.87 (95% CI 1.31 to 6.29). On the other hand, the adjusted OR for the other two outcome indicators by the wealth index widened from 1993 to 2008: 9.92 (95% CI 5.98 to 16.43) to 15.53 (95% CI 6.90 to 34.94) for skilled birth attendance and 7.74 (95% CI 4.22 to 14.21) to 16.00 (95% CI 7.99 to 32.02) for delivery in a medical facility. The concentration indices for maternal health utilisation in 1993 and 2008 were 0.19 and 0.09 for antenatal care; 0.26 and 0.24 for skilled birth attendance and 0.41 and 0.35 for delivery in a medical facility.

Conclusions

Over a 16-year period, gradients in antenatal-care use decreased and the high level of inequalities in skilled birth attendance and delivery in a medical facility persisted. The results showed a disproportionate use of institutional care at birth among disadvantaged Filipino women.

Keywords: Public health, Reproductive medicine, Social medicine, Statistics & research methods

Article summary.

Article focus

Assessing the changes in the inequalities associated with maternal healthcare use according to economic status in the Philippines.

Key messages

The study showed a reduction in the inequality of antenatal-care use through time, suggesting a substantial coverage of women in the lowest quintile.

However, inequality was shown to persist in skilled birth attendance and delivery in medical facilities, indicating minimal professional delivery care among disadvantaged women despite health system-wide efforts and improvements in the sociodemographic profile of the population.

The results call for equity-oriented research and policies to close the wide gap in skilled care at birth in the Philippines and to determine the success factors in the reduction of inequality in antenatal-care use.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study of long-term trends in inequalities in the utilisation of critical maternal health interventions using four comparable, nationally representative Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data sets commonly used as data sources in the literature.

Comparability of the different survey years was achieved by selecting only the women who had live-births within 1 year.

The DHS wealth index was used to represent changes in socioeconomic inequalities through time.

Introduction

Globally, there is increasing concern regarding inequities in maternal health, especially in developing countries.1 The slow pace of reduction in maternal death rates despite cost-effective solutions has urged the international community to look beyond accomplishing national targets and to begin addressing wide disparities in women's health.2

The key to realising equity in maternal health is the achievement of equity in key maternal health coverage, such as antenatal care (ANC) and skilled birth attendance (SBA). A previous study indicated the greatest inequity in SBA coverage followed by ANC of more than four visits.3 Wide inequalities in these interventions have hindered the reduction by 0.75 of maternal mortality ratio from 1990 to 2015.4–6

The Philippines has made efforts to improve women's health as mandated in its constitution and as a signatory to several women's international conventions including the Millennium Development Goals (MDG). National laws passed include the Magna Carta of Women (RA 9710), Maternity Benefits in Favor of Women Workers in the Private Sector (RA 7322) and Maternal Package for Normal Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery of the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth). Starting 1995, the Philippine government has also implemented a number of maternal health programmes, including two Women's Health and Safe Motherhood Projects.7 Health system reforms to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality were also spearheaded through the Department of Health Administrative Order No. 2008–0029 resulting in the Integrated Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health and Nutrition Strategy (MNCHN). Specific reproductive health indicators of MNCHN to be met in 2010 include (1) an increase in modern contraceptive prevalence rate to 60%, (2) an increase in the proportion of pregnant women having at least four ANC visits to 80% and (3) an increase in SBA and facility-based births to 80%.

There is, however, uncertainty regarding whether and how these maternal health policies and programmes have substantially reduced gaps in the use of key maternal interventions among women from varying socioeconomic backgrounds through time. The Philippines is currently off track and slow in achieving MDG-5. In 2010, the estimated maternal mortality ratio was 99/100 000 live-births, compared with the goal of 52/100 000 live-births in 2015.8 This slow achievement of national targets indicates wide economic and regional inequalities in maternal and child health services.9 The objective of this study was to assess the changes in inequalities in ANC, SBA and delivery in a medical facility (MEDFAC) in the Philippines between 1993 and 2008 according to woman's residence, woman's education, partner's education, wealth index, woman's age and birth order.

Data and methods

Data source

This study was performed using data from the Philippine Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) conducted for the periods of 1993, 1998, 2003 and 2008. All were nationally representative household surveys overseen by the National Statistics Office and National Steering Committee with financial and technical support from the USA Agency for International Development.10 PDHS gathers detailed information on population, health and nutrition to assist in the country's monitoring and impact evaluation. It ensures comparability across countries and time by developing standard model questionnaires, extensive survey procedures, interviewer training and data-processing guidelines.11 12

The 1993 and 1998 PDHS employed a two-stage sample design, representing 14 and 16 regions, respectively. A sample of 13 700 households (response rate: 99.2%) was randomly selected from 750 primary sampling units (PSUs) for 1993 and a sample of 13 708 households (response rate: 98.7%) was randomly selected from 755 PSUs for 1998. The 2003 and 2008 PDHS followed a stratified three-stage cluster sample design representing 17 regions. A sample of 13 914 households (response rate: 99.1%) was randomly selected from 819 PSUs for 2003 and a sample of 13 764 households (response rate: 99.3%) was randomly selected from 794 PSUs for 2008. Detailed descriptions of the study design and methods of data collection are accessible online in household survey reports.13–16

Subjects

The numbers of women interviewed were as follows: 1993, n=15 029; 1998, n=13 983; 2003, n=13 633 and 2008, n=13 594. The average response rate was 98%. The participants we included in the analysis were women aged 15–49 years who had a live-birth within 1 year, resulting in final sample sizes of 1707 in 1993, 1513 in 1998, 1325 in 2003 and 1209 in 2008.

Study variables

Three dependent variables were measured in the present study: (1) at least four antenatal consultations; (2) assistance by professional health personnel during delivery—either a doctor, nurse or midwife, excluding traditional birth attendants (hilot), relatives or friends, and (3) whether the birth occurred at home or in MEDFAC (public or private).

The Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) wealth index is defined as a composite measure of a household's relative economic status by using the data in the DHS. It is calculated by using data on a household's ownership of selected assets such as a television or car, persons per sleeping room, ownership of agricultural land, domestic servant and other country-specific items.17 The asset quintile was derived from this DHS wealth index score of women who had a live-birth within 1 year categorised into lowest, second, middle, fourth and highest in the respective survey years.

Other independent variables were type of residence (urban or rural), woman's age (<20, 20–29, 30–39, ≥40), birth order (1, 2, 3, ≥4) and educational level of the woman and her partner (none, primary, secondary, higher).

Ethical review

As protocols for all demographic health household surveys, the four PDHS were submitted for ethical reviews to the ICF Institutional Review Board (Calverton, Maryland, USA) and an institutional review board or ethics review panel in the Philippines for approving research studies on human subjects.18

Statistical analysis

Changes in the sociodemographic profile and use of ANC, SBA and MEDFAC of the population were analysed from household survey data in 1993, 1998, 2003 and 2008. Tests for trends were performed using the Mantel-Haenszel linear-by-linear association χ2 test. Crude and adjusted ORs between each dependent variable and all of the independent variables were assessed by multivariate logistic regression analysis. Complex household survey design was taken into account in all analyses using a sampling weight. All the missing data were excluded in the analysis. All analyses were performed using StataMP V.11 Statistical Software (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA).

Inequalities of each outcome variable according to the wealth index were estimated using the concentration index. It is defined as twice the area between the concentration curve and the line of equality (the 45° line) and was used to determine the magnitude of inequality. A concentration index of 0 indicates perfect equality. A measure of 1 (or −1) indicates perfect inequality.19 20

Results

There were changes in the sociodemographic profile of the population from 1993 to 2008 (table 1). The percentage of women with secondary and higher education increased during this period from 58.7% in 1993 to 74.6% in 2008. A corresponding increase was also observed in the percentage of partners who finished secondary and higher education from 57.4% in 1993 to 70.7% in 2008. The percentage of women with four or more children declined from 39.9% in 1993 to 31.7% in 2008.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and childbirth history of women aged 15–49 years, per survey year, Philippines, 1993–2008

| 1993 | 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | n=1707 (%) | n=1513 (%) | n=1325 (%) | n=1209 (%) |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 48.8 | 46.3 | 50.0 | 46.9 |

| Rural | 51.2 | 53.7 | 50.0 | 53.1 |

| Woman's education | ||||

| None | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

| Primary | 39.0 | 29.9 | 27.8 | 24.2 |

| Secondary | 37.4 | 39.7 | 42.5 | 50.3 |

| Higher | 21.3 | 28.6 | 27.8 | 24.3 |

| Partner's education | ||||

| None | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| Primary | 40.8 | 33.4 | 31.8 | 27.5 |

| Secondary | 37.3 | 36.7 | 40.1 | 45.0 |

| Higher | 20.1 | 28.3 | 26.1 | 25.7 |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Lowest | 20.2 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Second | 19.8 | 20.0 | 20.1 | 20.0 |

| Middle | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.1 |

| Fourth | 20.0 | 20.1 | 19.9 | 20.1 |

| Highest | 20.0 | 19.9 | 20.0 | 19.8 |

| Woman's age | ||||

| <20 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 8.2 |

| 20–29 | 53.7 | 53.7 | 53.3 | 53.5 |

| 30–39 | 35.6 | 35.1 | 34.4 | 32.5 |

| ≥40 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.8 |

| Birth order | ||||

| 1 | 22.6 | 24.5 | 27.7 | 28.5 |

| 2 | 20.7 | 21.1 | 23.6 | 24.6 |

| 3 | 16.8 | 19.6 | 15.5 | 15.2 |

| ≥4 | 39.9 | 34.8 | 33.2 | 31.7 |

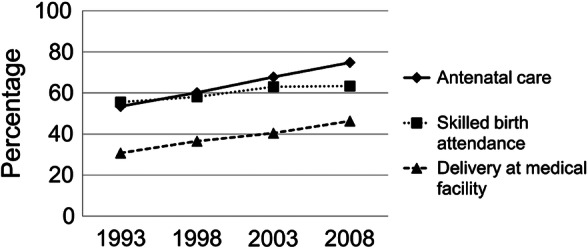

Figure 1 shows that the utilisation of ANC and MEDFAC increased from 53.4% in 1993 to 74.8% in 2008 and from 30.7% in 1993 to 46.3% in 2008, respectively. However, there is a limited change in utilisation of SBA from 55.5% in 1993 to 63.3% in 2008.

Figure 1.

Total percentage of antenatal-care use, skilled birth attendance and delivery in a medical facility, 1993–2008.

As shown in table 2, from 1993 to 2008, the rates of utilisation of ANC, SBA and MEDFAC were higher for women who were educated, better off, resided in an urban area and those with educated partners than among their poorer and less educated counterparts. There was a decline in the OR of women in the highest wealth quintile compared with the lowest in ANC from 1993 to 2008. The adjusted OR for antenatal-care use when comparing the highest wealth-index quintile with the lowest quintile declined from 1993 to 2008: 3.43 (95% CI 2.22 to 5.28) to 2.87 (95% CI 1.31 to 6.29). On the other hand, the adjusted OR for the other two outcome indicators by the wealth index widened from 1993 to 2008: 9.92 (95% CI 5.98 to 16.43) to 15.53 (95% CI 6.90 to 34.94) for SBA and 7.74 (95% CI 4.22 to 14.21) to 16.00 (95% CI 7.99 to 32.02) for delivery in MEDFAC.

Table 2.

Adjusted ORs of the association between wealth index and sociodemographic characteristics and antenatal care, skilled birth attendance or delivery in medical facility of women age 15–49 years, Philippines, 1993 (n=1707), 1998 (n=1513), 2003 (n=1325), 2008 (n=1209)

| Indicator | Antenatal care |

Skilled birth attendance |

Delivery at medical facility |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 |

1998 |

2003 |

2008 |

1993 |

1998 |

2003 |

2008 |

1993 |

1998 |

2003 |

2008 |

|||||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Residence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Urban | 1.29* | 1.02 to 1.62 | 1.44** | 1.08 to 1.93 | 1.70*** | 1.26 to 2.28 | 0.99 | 0.71 to 1.38 | 2.59*** | 2.03 to 3.31 | 3.08*** | 2.27 to 4.18 | 3.21*** | 2.37 to 4.34 | 2.11*** | 1.52 to 2.93 | 3.12*** | 2.35 to 4.12 | 2.43*** | 1.77 to 3.35 | 1.90*** | 1.41 to 2.56 | 1.47** | 1.07 to 2.02 |

| Rural (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Woman's education | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| None | 0.58 | 0.27 to 1.26 | 0.55 | 0.21 to 1.45 | 0.25** | 0.09 to 0.71 | 0.08*** | 0.02 to 0.36 | 0.17** | 0.05 to 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.21 to 2.39 | 0.22** | 0.08 to 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.14 to 3.21 | 0.17 | 0.02 to 1.94 | 0.48 | 0.11 to 2.00 | 0.09* | 0.01 to 1.01 | 0.82 | 0.09 to 7.51 |

| Primary | 0.54** | 0.37 to 0.79 | 0.46*** | 0.29 to 0.74 | 0.53** | 0.34 to 0.85 | 0.38*** | 0.21 to 0.68 | 0.43*** | 0.27 to 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.39 to 1.12 | 0.48** | 0.30 to 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.40 to 1.19 | 0.58** | 0.38 to 0.88 | 0.52** | 0.31 to 0.86 | 0.44*** | 0.28 to 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.35 to 1.03 |

| Secondary | 0.67* | 0.47 to 0.95 | 0.65* | 0.44 to 0.97 | 0.69 | 0.46 to 1.03 | 0.59** | 0.36 to 0.96 | 0.58** | 0.38 to 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.56 to 1.34 | 0.57 | 0.37 to 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.56,1.41 | 0.59** | 0.41 to 0.84 | 0.54*** | 0.37 to 0.78 | 0.49*** | 0.34 to 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.53 to 1.13 |

| Higher (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Partner's education | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| None | 0.39* | 0.16 to 0.94 | 0.30* | 0.10 to 0.85 | 0.41 | 0.16 to 1.05 | 0.55 | 0.19 to 1.58 | 0.09* | 0.01 to 0.71 | 0.02*** | 0.00 to 0.20 | 0.22** | 0.08 to 0.61 | 0.06** | 0.01 to 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.03 to 2.54 | (omitted)† | 0.11 | 0.01 to 1.11 | (omitted)† | ||

| Primary | 0.53*** | 0.36 to 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.43 to 1.03 | 0.54** | 0.34,0.86 | 0.65 | 0.37 to 1.13 | 0.65 | 0.42 to 1.02 | 0.47** | 0.29 to 0.78 | 0.53** | 0.33 to 0.86 | 0.41*** | 0.23 to 0.71 | 0.36*** | 0.23 to 0.55 | 0.30*** | 0.19 to 0.42 | 0.55* | 0.34 to 0.87 | 0.50** | 0.30 to 0.83 |

| Secondary | 0.74 | 0.52 to 1.05 | 0.75 | 0.52 to 1.09 | 0.68 | 0.45 to 1.02 | 0.75 | 0.45 to 1.24 | 0.74 | 0.50 to 1.11 | 0.78 | 0.51 to 1.19 | 0.66 | 0.43 to 1.04 | 0.66 | 0.40 to 1.07 | 0.58** | 0.41 to 0.83 | 0.46*** | 0.32 to 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.50 to 1.04 | 0.85 | 0.57 to 1.27 |

| Higher (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Woman's age | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <20 | 0.91 | 1.02 to 1.62 | 0.45** | 0.27 to 0.74 | 1.12 | 0.66 to 1.90 | 0.91 | 0.52 to 1.58 | 0.93 | 0.54 to 1.61 | 0.70 | 0.39 to 1.26 | 0.89 | 0.52 to 1.53 | 0.92 | 0.51 to 1.66 | 0.88 | 0.46 to 1.71 | 0.73 | 0.34 to 1.57 | 0.70 | 0.41 to 1.20 | 0.74 | 0.42 to 1.31 |

| 20–29 (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 30–39 | 1.29 | 0.98 to 1.69 | 1.86*** | 1.34 to 2.58 | 1.20 | 0.86 to 1.66 | 1.42 | 0.98 to 2.04 | 1.17 | 0.86 to 1.60 | 1.59** | 1.10 to 2.29 | 1.31 | 0.92 to 1.89 | 1.54** | 1.03 to 2.30 | 1.36 | 0.98 to 1.91 | 1.26 | 0.85 to 1.85 | 1.46** | 1.03 to 2.07 | 1.59** | 1.05 to 2.40 |

| ≥40 | 1.41 | 0.84 to 2.39 | 1.66 | 0.94 to 2.91 | 0.87 | 0.46 to 1.62 | 0.92 | 0.49 to 1.70 | 1.96* | 1.07 to 3.57 | 1.56 | 0.81 to 2.99 | 0.87 | 0.42 to 1.83 | 3.12** | 1.48 to 6.58 | 1.96 | 0.97 to 3.97 | 2.02 | 0.98 to 4.15 | 1.04 | 0.47 to 2.32 | 3.44*** | 1.69 to 6.98 |

| Birth order | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 0.76 | 0.55 to 1.06 | 0.88 | 0.60 to 1.30 | 0.84 | 0.57 to 1.25 | 0.79 | 0.50 to 1.27 | 0.76 | 0.53 to 1.11 | 0.61** | 0.40 to 0.93 | 0.76 | 0.49 to 1.17 | 0.87 | 0.57 to 1.33 | 0.53*** | 0.35 to 0.78 | 0.52** | 0.33 to 0.80 | 0.50*** | 0.34 to 0.74 | 0.56** | 0.37 to 0.84 |

| 3 | 0.64* | 0.45 to 0.93 | 0.64* | 0.42 to 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.59 to 1.45 | 0.55** | 0.33 to 0.92 | 0.50*** | 0.33 to 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.47 to 1.18 | 0.69 | 0.42 to 1.13 | 0.61 | 0.36 to 1.02 | 0.36*** | 0.23 to 0.55 | 0.72 | 0.44 to 1.16 | 0.45*** | 0.29 to 0.70 | 0.37*** | 0.23 to 0.61 |

| ≥4 | 0.41*** | 0.30 to 0.58 | 0.36*** | 0.24 to 0.54 | 0.56** | 0.36 to 0.87 | 0.53** | 0.32 to 0.88 | 0.47*** | 0.32 to 0.69 | 0.31*** | 0.20 to 0.49 | 0.51** | 0.31 to 0.82 | 0.47** | 0.28 to 0.80 | 0.32*** | 0.21 to 0.49 | 0.41*** | 0.25 to 0.67 | 0.28*** | 0.18 to 0.45 | 0.23*** | 0.13 to 0.38 |

| Wealth index | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lowest (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Second | 1.09 | 0.79 to 1.50 | 1.21 | 0.86 to 1.70 | 0.85 | 0.59 to 1.24 | 1.48 | 0.99 to 2.20 | 2.00*** | 1.38 to 2.89 | 1.99*** | 1.34 to 2.96 | 2.06*** | 1.36 to 3.13 | 1.74** | 1.14 to 2.64 | 2.11** | 1.16 to 3.83 | 1.88* | 1.07 to 3.29 | 2.15** | 1.25 to 3.71 | 1.79** | 1.05 to 3.05 |

| Middle | 1.26 | 0.89 to 1.78 | 1.85** | 1.26 to 2.72 | 0.77 | 0.51 to 1.16 | 1.25 | 0.80 to 1.96 | 3.30*** | 2.26 to 4.83 | 4.05*** | 2.63 to 6.24 | 2.95*** | 1.88 to 4.64 | 3.43*** | 2.18 to 5.34 | 2.83*** | 1.58 to 5.07 | 2.31** | 1.29 to 4.14 | 3.01*** | 1.73 to 5.22 | 3.46*** | 2.02 to 5.91 |

| Fourth | 1.68** | 1.16 to 2.43 | 2.25*** | 1.45 to 3.52 | 1.12 | 0.70 to 1.81 | 2.06** | 1.19 to 3.57 | 4.71*** | 3.11 to 7.13 | 7.17*** | 4.33 to 11.86 | 4.87*** | 2.90 to 8.19 | 7.20*** | 4.22,12.30 | 4.50*** | 2.50 to 8.13 | 4.29*** | 2.38 to 7.74 | 4.07*** | 2.32 to 7.13 | 6.09*** | 3.41 to 10.89 |

| Highest | 3.43*** | 2.22 to 5.28 | 3.54*** | 1.98 to 6.33 | 2.44** | 1.31 to 4.54 | 2.87** | 1.31 to 6.29 | 9.92*** | 5.98 to 16.43 | 12.29*** | 6.22 to 24.27 | 6.98*** | 3.62 to 13.46 | 15.53*** | 6.90 to 34.94 | 7.74*** | 4.22 to 14.21 | 7.55*** | 3.95 to 14.44 | 6.98*** | 3.76 to 12.94 | 16.00*** | 7.99 to 32.02 |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

†All participants in this category did not deliver in a medical facility and were removed from the analysis.

Adjusted for residence, woman's education, partner's education, woman's age and birth order.

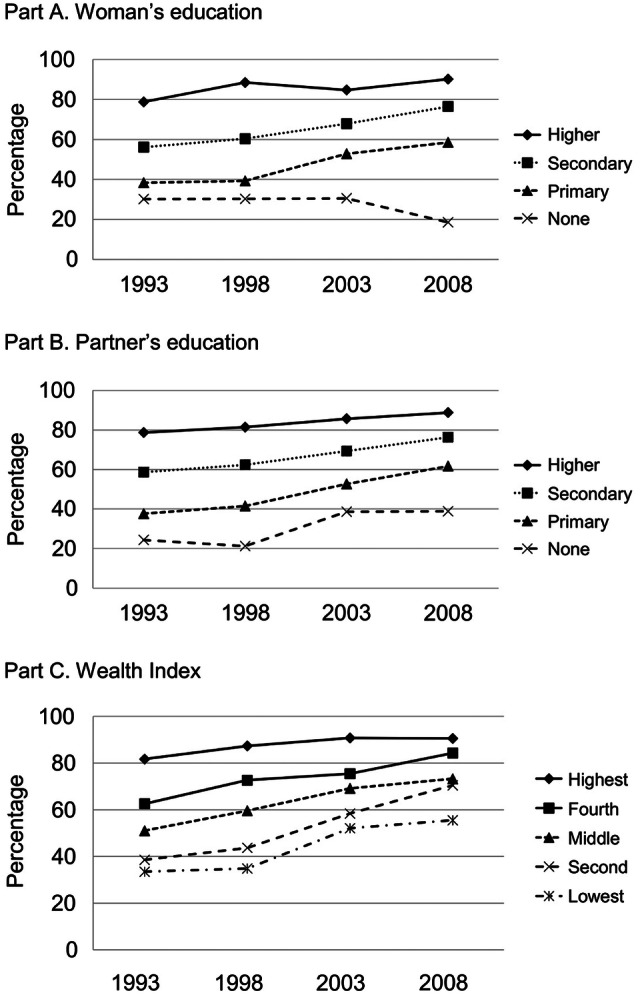

Figure 2 shows that there was a marked reduction in inequality of ANC from 1993 to 2008. Although gradients of its use among women with no education and women with higher education widened from 1993 to 2008, the gradients of ANC use among women with primary education and women with higher education as their highest educational attainment decreased from a difference of 40.4% point in 1993 to 31.6% point in 2008. A marked reduction was seen among women in the highest quintile compared with those in the lowest quintile, with a difference of 48.2% point in 1993 decreasing to 35.0% point in 2008. A reduction in the concentration index for ANC was observed from 1993 to 2008.

Figure 2.

Trends in the percentage of antenatal-care use by (A) woman's education, (B) partner's education, (C) wealth index, 1993–2008. Note: Concentration index based on wealth index in 1993 (0.19, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.21); 1998 (0.18, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.21); 2003 (0.12, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.14); and 2008 (0.09, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.11).

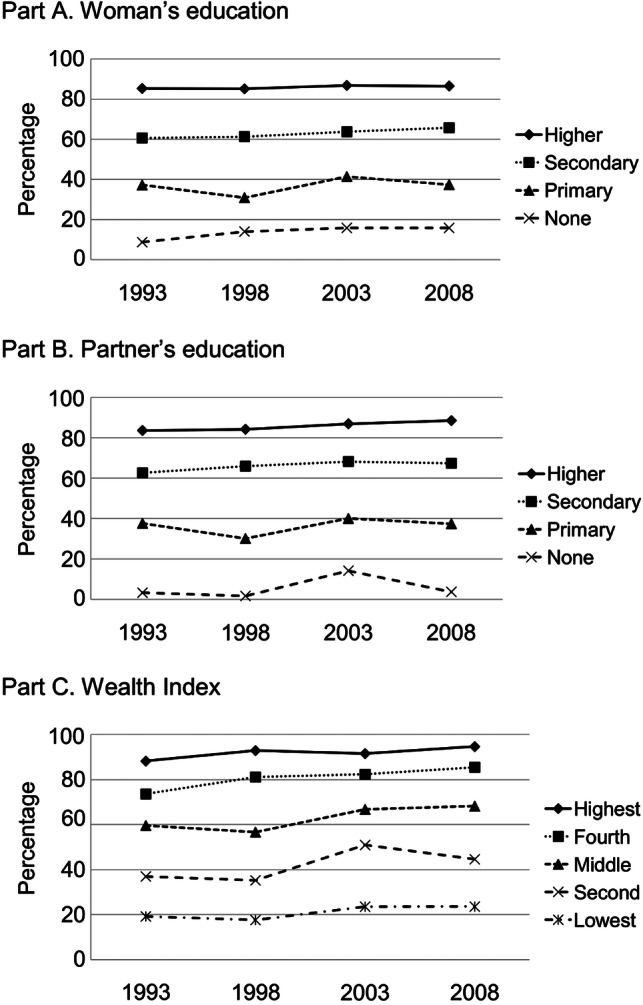

Figure 3 shows the limited changes in the inequality of SBA from 1993 to 2008. A reduction was observed in the gradient of SBA in comparison between women with no education and those with higher education with a difference of 76.6% point in 1993 decreasing to 70.7% point in 2008. In contrast, women in the highest quintile compared with those in the lowest quintile increased from a difference of 69.1% point in 1993 increasing to 71.1% point in 2008. A reduction in the concentration index for SBA was observed from 1993 to 2008; however, the concentration index obtained was larger than that for ANC.

Figure 3.

Trends in the percentage of skilled birth attendance by (A) woman's education, (B) partner's education, (C) wealth index, 1993–2008. Note: Concentration index based on wealth index in 1993 (0.26, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.29); 1998 (0.29, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.31); 2003 (0.22, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.24); and 2008 (0.24, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.27).

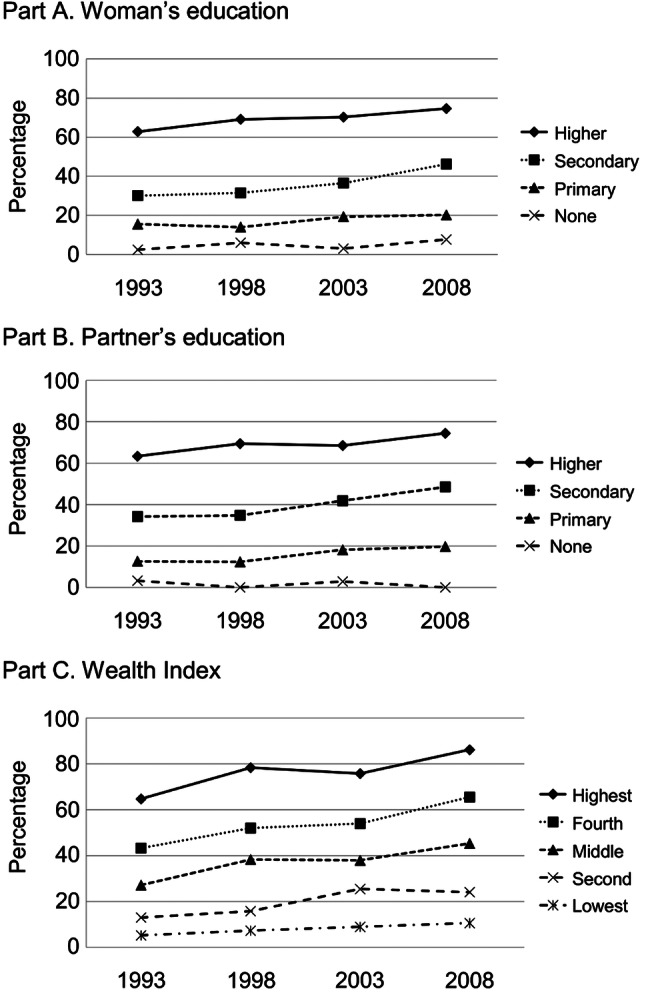

Figure 4 shows the changes in inequality of MEDFAC from 1993 to 2008. As shown in the figure, the gradient of MEDFAC between women with no education and those with higher education widened from a difference of 60.4% in 1993 to 67% in 2008. The difference between MEDFAC % in the highest quintile and that in the poorest quintile increased from 59.5% point in 1993 to 75.6% point in 2008. A reduction in the concentration index for MEDFAC was observed from 1993 to 2008; however, the concentration index obtained was also large in comparison with ANC.

Figure 4.

Trends in the percentage of delivery at medical facility by (A) woman's education, (B) partner's education, (C) wealth index, 1993–2008. Note: Concentration index based on wealth index in 1993 (0.41, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.45); 1998 (0.41, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.44); 2003 (0.34, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.37); and 2008 (0.35, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.38).

Discussion

This is the first study to describe the time trends in the inequalities of maternal healthcare utilisation in the Philippines. The analysis of four nationally representative PDHS survey data sets ranged over a period of 16 years from 1993 to 2008 and showed a substantial increase in antenatal coverage and limited improvement in professional delivery care. Furthermore, our findings demonstrated a reduction in the inequality of ANC use through time, suggesting the coverage of women in the lowest quintile or possibly a decreased coverage for the wealthier quintile. The study also provided evidence of persistence of inequality in SBA and MEDFAC indicating minimal professional delivery care among women with the lowest socioeconomic conditions.

Our findings are in line with evidence on 25 low-income countries’ referred inequalities on institutional delivery rates as well as a weak health system and lack of skilled birth workers as the main barriers of use.21 Marked underutilisation of SBA has been noted among poor women in many studies.22 23 However, one study conducted in India reported low utilisation of both ANC and SBA among poor women through time despite governmental interventions.24

The increase in proportion of antenatal coverage from 1993 to 2008 was greater than that of births attended by skilled health personnel or that of delivery at MEDFAC. Over the last several decades, the Philippine government has launched maternal health projects and programmes to improve women's health. These were implemented alongside extensive health system reforms across the country on health financing, health regulation, health service delivery and good governance in health following the decentralisation of healthcare services.25 A study indicated that implementation areas that have intensively adopted the health system-wide reforms have improved the overall maternal health outcomes compared with those that have not adopted them. However, the poorly developed health information systems and lack of referral emergency-care facilities in remote coastal and isolated mountain communities were the challenges that remained to be addressed.26

The results of the present study indicated reductions in the inequality of ANC use. This translates to substantial ANC use among women at the lowest living standard quintile. This can be explained by improvements in both the healthcare system and in the sociodemographic profile of the population. The PhilHealth has been reported to increase the uptake and standards of ANC.27 Improvements in the quality of services in healthcare institutions through accreditation and the coverage of financial costs by insurance contributed to the increased use of ANC by Filipino women regardless of the sociodemographic status.27 28 There was also an increase in the total number of midwives and rural (barangay) health units over the years, which addressed the problems of distance and lack of availability of health workers and ANC facilities.29 Moreover, positive changes in the sociodemographic and demographic profiles, such as increases in the educational status of women and their partners, better economic status of women and decreased fertility, may also explain the observed reductions in the inequality of ANC use.30

Inequalities in SBA and MEDFAC persist in the Philippines despite the health system-wide efforts and improvements in the sociodemographic profile of the population. After 16 years, the majority of Filipino women from the lowest living standard quintile continue to deliver at home without professional assistance. In the Philippines, finance, transportation, absence of companion to accompany to the health facility and treatment of health professionals to disadvantaged women are major barriers that must be addressed to increase the rate of hospital delivery.31 The majority of unskilled home deliveries among Filipino women occur near hospitals, and financial burden associated with hospital delivery is the main concern regardless of socioeconomic status. In 2009, for families from the lowest 30% income group, delivery at a hospital would consume a minimum of 6.6–24.3% of the family's total annual income.32 33 This indicates that catastrophic financial costs are responsible for the decision by poorer Filipino women to deliver at home, even if they are close to health facilities, in addition to low-educational status and rural residence. PhilHealth coverage is low with only 42% of families with at least one family member being enrolled in 2004.34 Furthermore, the out-of-pocket expenditure as a percentage of private expenditure on health has increased from 77.2% in 2000 to 83.6% in 2010.35

This study has a number of strengths. It used four nationally representative samples obtained by the DHS and commonly used as data sources in the literature worldwide. A national sample of women aged 15–49 years were collected to obtain a sufficient sample size for each survey year. Selection of the women who had live-births only within 1 year as the participants of the individual surveys sharpened the comparison of the data of four different years. This reduced the magnitude of recall bias by the respondents. All four PDHS followed strict data quality checks through pretesting, translation of questionnaires into the local dialect, interviewer training and duplicate data entry. It also employed a standardised questionnaire format which was carefully developed to ascertain accurate responses and information from the participants. The analysis used the DHS-wealth index, a systematically developed composite index, to measure the economic status of the participants among the DHS samples. The study used relevant measurements of inequity, the concentration index, which measures the long-term trends in inequalities in the utilisation of critical maternal healthcare interventions in the Philippines, which is important for future health policy.

Caution should be exercised in interpreting trends of maternal healthcare use by the DHS-wealth index since it is an index to show the relative position measured by a composite economic-status indicator among the participants of the particular year and country. Therefore, the scores of wealth index in different years are not comparable.

Our study implies the need for research solutions to reduce inequality in SBA and delivery at MEDFAC, and to determine the factors responsible for the persistence of inequality in SBA and delivery at MEDFAC despite government and non-governmental efforts. Recognising reproductive health as a basic right of women regardless of sociodemographic status is important in formulating national policy and programmes to address inequality in maternal health service utilisation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to MEASURE DHS for allowing us to analyse the 1993, 1998, 2003 and 2008 PDHS data sets. We also acknowledge with the deepest thankfulness the organisations and individuals in the Philippines who contributed to the 1993, 1998, 2003 and 2008 PDHS.

Footnotes

Contributors: FM and KN conceptualised and designed the study. FM obtained the data and FM and MK analysed the data. FM, KN, MK and SK structured and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Commission on information and accountability for Women's and Children's Health Keeping promises, measuring results. World Health Organization, 2011. http://www.everywomaneverychild.org/images/content/files/accountability_commission/final_report/Final_EN_Web.pdf (accessed Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomsen S, Hoa DT, Målqvist M, et al. Promoting equity to achieve maternal and child health. Reprod Health Matters 2011;19:176–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barros AJ, Ronsmans C, Axelson H, et al. Equity in maternal, newborn and child health interventions in countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet 2012;379:1225–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zere E, Kirigia JM, Duale S, et al. Inequities in maternal and child health outcomes and interventions in Ghana. BMC Public Health 2012;12:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wirth M, Sacks E, Delamonica E, et al. “Delivering on the mdgs?”: equity and maternal health in Ghana, Ethiopia and Kenya. East Afr J Public Health 2008;5:133–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silal SP, Penn Kenana L, Harris B, et al. Exploring inequalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asian Development Bank Operations Evaluation Department Project performance evaluation report in the Philippines. Asian Development Bank, 2007. http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/27010-PHI-PPER.pdf (accessed Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank Trends in maternal mortality 1990–2010: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2012/Trends_in_maternal_mortality_A4-1.pdf (accessed Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavado RF, Lagrada LP. Are Maternal and Child Care Programs Reaching the Poorest Regions in the Philippines? Philippine Institute for Developmental Studies. 2008. Nov; Discussion Paper Series No. 2008-30

- 10.Demographic and Health Surveys Calverton: Macro International. http://www.measuredhs.com/ (accessed Jul 2011).

- 11.Rutstein SO, Rojas G. Guide to DHS statistics. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro International, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croft T. DHS Data editing and imputation. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro International, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Statistics Office (NSO) [Philippines] and Macro International Inc. (MI). National Demographic Survey 1993. Calverton, MD: NSO and MI, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Statistics Office (NSO), Department of Health (DOH) [Philippines] and Macro International Inc. (MI). National Demographic Survey 1998. Manila: NSO and MI, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Statistics Office (NSO) [Philippines], and ORC Macro National Demographic Survey 2003. Calverton, Maryland: NSO and ORC Macro, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Statistics Office (NSO) [Philippines], and ICF Macro National Demographic Survey 2008. Calverton, MD: National Statistics Office and ICF Macro, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutstein SO, Kiersten J. The DHS wealth index. DHS comparative reports No. 6. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro International, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18. ICF International. Survey Organization Manual for Demographic and Health Surveys. MEASURE DHS. Calverton. Maryland: ICF International 2012. http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/DHSM10/DHS6_Survey_Org_Manual_28Feb2012.pdf (accessed July 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Donnell O, Van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, et al. Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2008. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPAH/Resources/Publications/459843-1195594469249/HealthEquityFINAL.pdf (accessed Jul 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagstaff A. The concentration index of a binary outcome revisited. J Health Econ 2011;20:1155–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Sirilak S. Trends and inequities in where women delivered their babies in 25 low-income countries: evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys. Reprod Health Matters 2011;19:75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zere E, Oluwole D, Kirigia JM, et al. Inequalities in skilled attendance at birth in Namibia: a decomposition analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011;11:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collin SM, Anwar I, Ronsmans C. A decade of inequality in maternity care: antenatal care, professional attendance at delivery, and caesarean section in Bangladesh (1991–2004). Int J Equity Health 2007;6:9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pathak PK, Singh A, Subramanian SV. Economic Inequalities in maternal health care: prenatal care and skilled birth attendance in India, 1992–2006. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e13593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakshminarayanan R. Decentralisation and its implications for reproductive health: the Philippines experience. Reprod Health Matters 2003;11:96–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huntington D, Banzon E, Recidoro ZD. A systems approach to improving maternal health in the Philippines. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:104–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozhimannil KB, Valera MR, Adams A, et al. The population-level impacts of a national health insurance program and franchise midwife clinics on achievement of prenatal and delivery care standards in the Philippines. Health Policy 2009;92:55–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quimbo SA, Peabody JW, Shimkhada R, et al. Should we have confidence if a physician is accredited? A study of the relative impacts of accreditation and insurance payments on quality of care in the Philippines. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:505–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Department of Health Vital, health and nutrition. Manila: National Statistical Coordination Board, 2012. http://www.nscb.gov.ph/secstat/d_vital.asp (accessed Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simkhada B, Teijlingen ER, Porter M, et al. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal in developing countries: a systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 2008;61:244–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sobel HL, Oliveros YE, Nyunt US. Secondary analysis of a national health surveu on factoes influencing women in the Philippines to deliver at home and unattended by a healthcare professional. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2010;111:157–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Statistics Office 2004 Annual Poverty Indicators Survey (APIS) (Preliminary Results). Manila: National Statistics Office, 2005. http://www.census.gov.ph/content/2004-annual-poverty-indicators-survey-apis-preliminary-results (accessed Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ericta CN. Families in the bottom 30 percent income group earned 62 thousand pesos in 2009. Manila: National Statistics Office, 2011. http://www.census.gov.ph/data/pressrelease/2011/ie09frtx.html (accessed Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsolmongerel T. Costing study for selected hospitals in the Philippines 2009. http://www.doh.gov.ph/sites/default/files/Costing%20Study%20for%20Selected%20Hospitals%20in%20the%20Philippines.pdf (accessed Mar 2012).

- 35.Global Health expenditure Database Philippines national expenditure on health (Philippine Peso) 1995–2010. World Health Organization, 2012. http://apps.who.int/nha/database/StandardReport.aspx?ID=REP_WEB_MINI_TEMPLATE_WEB_VERSION&COUNTRYKEY=84655 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.